#since when are german audiences louder than anything at all else including a falling needle? unrealistic

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

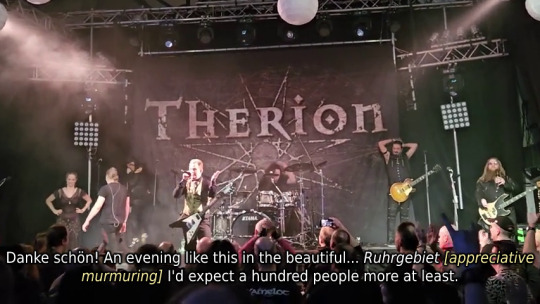

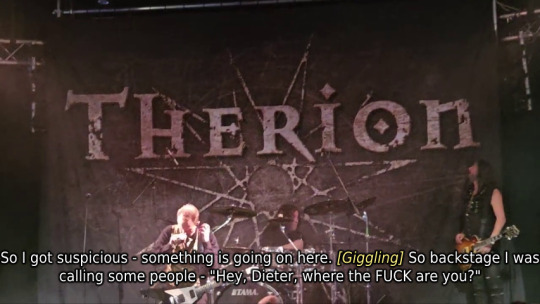

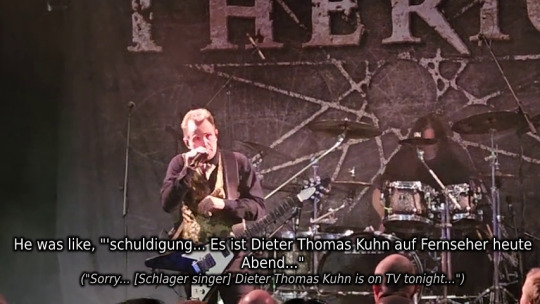

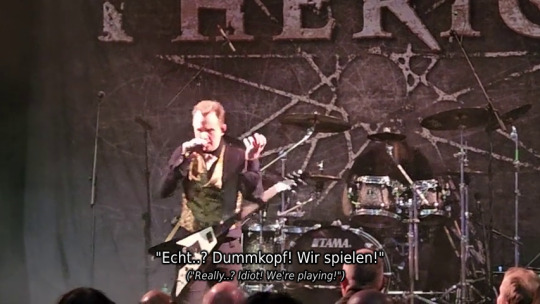

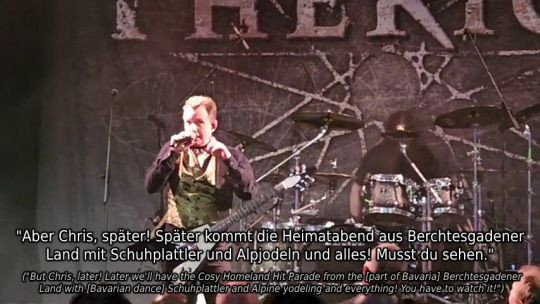

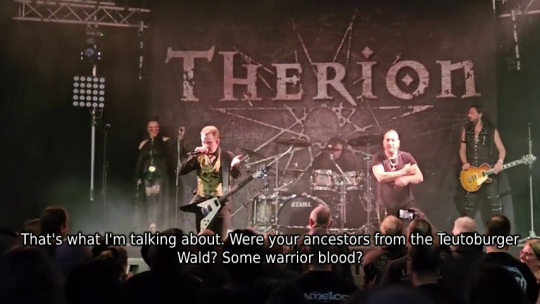

Christofer delivers some truly next-level pandering to Westphalian sensibilities. I wasn't even there, and yet I almost blushed. [x]

Calling the Ruhr area beautiful (I know Therion is all about seeing the holy and beautiful in the reviled and ugly, but come on.)

Dunking on a schlager star and Bavarian customs

Arminius reference

Talking shit about the Netherlands

Translator's note, "Heimatabend" is literally "Homeland Evening", but that sounds like some kind of military drill in English. I translated it in accordance with the folksy and corny sound it has in German. I corrected some minor pronunciation mistakes (like Teutenburger -> Teutoburger).

#therion#symphonic metal#music stuff#germany#christofer johnsson#he got a few words wrong but still very impressive for a foreigner#i wish i knew what he said in berlin and munich but alas#it has not been uploaded it seems#he didn't have any czech insider jokes in prague#only said we were louder than ostrava#the kind of thing he definitely says to all the girls#since when are german audiences louder than anything at all else including a falling needle? unrealistic#thanks for noticing the borderline klingon warrior spirit of my epic home area though! let me buy you some prune juice

1 note

·

View note

Text

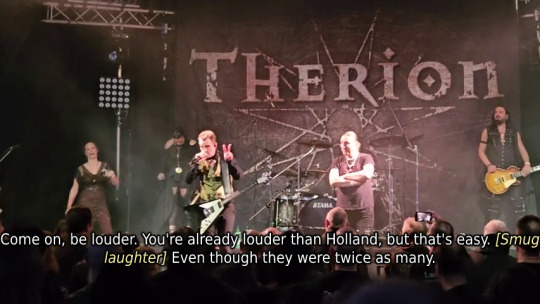

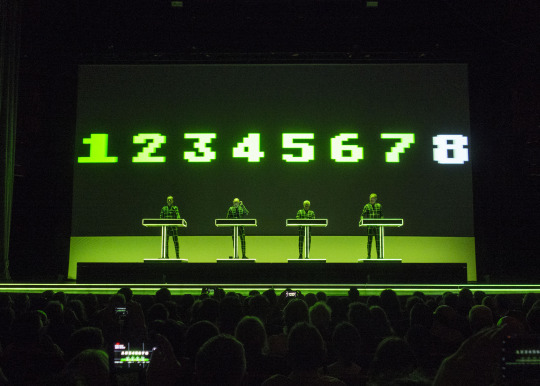

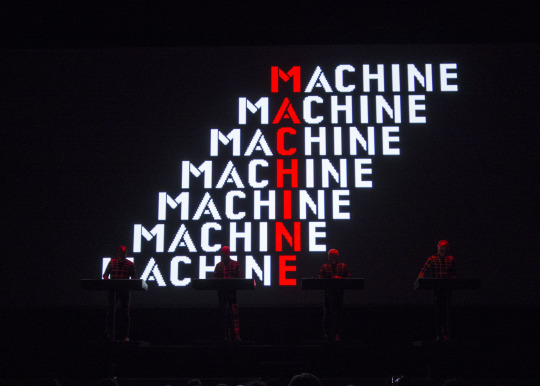

Kraftwerk 3D

Symphony Hall, Birmingham

Tuesday 13th June 2017

The seventies were grim. A decade of industrial unrest and economic meltdown where bankrupt cities decayed as litter would blow their across deserted streets and those who could fled to the suburbs leaving only the homeless, pimps and drug dealers behind. Even those havens on the edge of town offered only slight relief; Britain was a failed state where power cuts and a three day week were followed at the end of the decade by the winter of discontent. Rubbish remained uncollected and bodies were left on slabs in mortuaries unburied. Yes the seventies were grim, at least that is what we are told. This is the version written by those who were to see salvation arriving in the form of Thatcher, rescuing us from malaise into which we had sunk, a version that emphasises the bad and ignores the good. “Never forget the chaos before Thatcher” greets any challenge to the status quo that sees the stagnating wages, diminishing opportunities and falling standards of living for the many whilst a few take an ever greater share of the wealth. This, we are told, is how it has to be, the alternative is to go back to the seventies and that was, as we keep telling you, grim.

Instead of being a version of history, however, this has become the version, the one that is used as a threat to those who didn’t live through it who have little on which to build their own. Each of us, however, has our own memories that create a different story, one in which the decade was far more optimistic and exciting. My story sees me go from junior school to starting university, a decade of exploration, the excitement of discovery and the intensity of emotions experienced for the first time. My horizons broadened as the boundaries that had once marked the extent of my world were broken forever. A time of long warm summer days, where we could stay out long after the sun had set, and short sharp cold winters, the reality of course was very different but these are the memories. By the middle of the decade, I was at secondary school, old enough to be trusted on a night out with my friends, a regular one I am now ashamed to say was disco at a local Conservative club, and to go to football matches without having to be escorted by my dad. It was also where my unhealthy obsession with music started to develop. From the start of the decade, songs were making their way into my young mind, leaving an impression so strong that I still know the lyrics to “In the Year 2525” by Zager and Evans despite not having heard it for years. A few years later, I acquired my first singles, “Hot Love” by T Rex and “Double Barrel” by Dave and Ansell Collins, played to the point of destruction. More followed, some, “Starman”, “Pyjamarama” and “This Town Ain’t Big enough for the Both of Us“ still seem like cool choices, others, “Son of My Father”, “Tiger Feet”, “Blockbuster” less so. As my physical world expanded, so to did did my musical world, beyond the short burst of pop so that albums began to nestle alongside those early singles; my short attention span, however, meaning that they were rarely absorbed in a single sitting. “Led Zeppelin IV” “Dark Side of the Moon”, “The Yes Album” became my challenges, concentration was needed to unpick them, just playing “Black Dog” then moving onto something else meant that the threshold to the adult world was still out of reach.

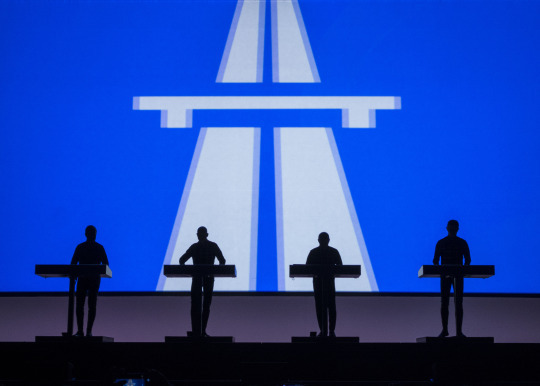

It is often forgotten that 1975 was a glorious summer, mainly because it was topped by the year that followed it, but it was during those bright sunlit days that the order started to change, that rather than holding a secret only accessible to a chosen few, these behemoths of prog would start to be seen as being a bit pretentious. For me, the catalyst for this came from a very unlikely source. Then, television was a family experience where after a meal we would all sit around to watch the evening’s entertainment unfold, something that usually involved our parents complaining about our tastes but being selfish and stroppy we usually managed to get our own way. One programme we all watched, however, was “Tomorrow’s World” which one evening included a short film about four smartly dressed Germans striking metal discs with what looked like knitting needles. Playing what we now know to be “Autobahn”, the announcer informs us that they have recently managed to dispense with all recognisable instruments and ”next year, they hope to eliminate the keyboard altogether,” The future will see them wearing jackets with electronic lapels that will be played by touch. Now the clip looks bizarre, Florian Schnieder’s last look into the camera is creepy and the electronic music sounds primitive but then it was revolutionary and that single moment inspired many to give up on trying to contort their hands into forming an Fm7 chord and pursue their rock ’n’ roll dream by programming a synthesiser. The single most important event in the evolution of dance music? - forty years on The Guardian identified it as just that.

They never did get those jackets and of the four who featured in the film, three have now departed leaving just Ralf Hütter as the sole original member. The culmination of those plans outlined the their Dusseldorf studio all those years ago, however, appears towards the end of this intensely absorbing show. With just a logo left on the screen informing us that this has been a “Kling Klang Musikfilm” the stage is left in darkness as the curtain is slowly drawn to hide the four lecterns that are lined up across the front. A deep electronic pulse soon resonates around the hall followed by a few clangs and bleeps, eventually combining to form the recognisable introduction to what will follow. Faster and faster it gets as the curtain opens to reveal the source, four red shirted robots staring vacantly out at the audience. Their upper bodies rotate while their arms make slow dramatic gestures, managing to be in sync despite the slow deliberate movements appearing to be a different dimension to the beat of the music. The instruments have gone, no keyboards, no human presence at all, just technology, a possible glimpse into a future where artificial intelligence will keep the music alive long after its creators have gone, “We are programmed just to do, Anything you want us to”.

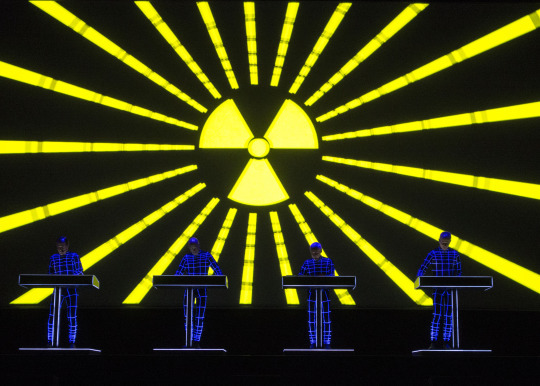

It is a tempting narrative but it is based on two myths, the first being that Kraftwerk have always been focused purely on technology and secondly that they have always been about the future. True, they often seem to encourage these easy perceptions but even during “Numbers”, built around counting up and down in a heavily synthesised voice, it becomes clear that the importance is not the technology itself but the human interaction with it. As technophiles, the future they saw was full of optimism but in some cases the music has taken on a more sinister meaning that it never had on release. “Computer World” becomes about the dehumanising effects of big data whilst “Radioactivity” has become an elegy to the victims of the nuclear disasters read out in the introduction. Reworked to a faster pace with a trance like beat, the dispassionate reading out of these disasters and Hütter singing some of the lyrics in Japanese, makes it eerily haunting. “Computer Love” sees the human interface at is most vulnerable, isolated staring at the screen, using the computer as a means of finding love, in some ways one of their most prescient songs.

Whilst Kraftwerk were, and in many ways reman, cutting edge, there was always more than a whiff of nostalgia about their future. The VW and Mercedes cars that drive along the “Autobahn” are those around when the music was created and it is doubtful that even German roads were ever that quiet, but then the song has always been about the ideal of the open road rather than the reality. “Spacelab” could be straight out of a 50s sci-fi movie, the 3d glasses worn by the audience likewise, and the effect of the satellite reaching out into the audience is startling, someone sitting a couple of rows in front of me ducks. It also finishes with the spaceship flying over Birmingham and landing outside Symphony Hall, despite their impassive manner, they always did show a wry sense of humour. The music from “Tour De France” is accompanied by images from the race over the years but with added graininess to give even the most recent images a vintage feel.

“Tour De France” also shows that despite producing little in the way of new material for over a quarter of a century, they have continually reworked their music to adapt to changing tastes, the availability of new methods of producing their sound and their own, mostly Hütter’s, relentless quest for perfection. It is “Tour De France” that has changed the most since I last saw them four years ago, becoming a montage of man and machine, trance like rhythms and swirling melodies, it was almost possible feel the sweat. The clear acoustics of Symphony Hall meant the low bass of “Man Machine” vibrated every muscle, so much louder that it had been last time. There were some shouts for the volume to go up but it seemed right to me, loud when it needed to be but also providing quiet moments, the dynamics showing the grasp they always had for the feel of the music. No where was this better illustrated than on the delicate beauty of “Neon Lights”. The pounding bass and crashing metal on metal of “Trans Europe Express” again seemed to leap out of the speakers with more force than before but “The Model” was pretty much as it has always been, perfection needs no reworking.

The last time we saw Kraftwerk was at Latitude festival four years ago, I loved them but many there, including my wife, were soon complaining that they were a bit boring. In fairness, a Suffolk field is not the best place to be drawn into a spectacle like this and seeing them amongst their most dedicated fans in a more enclosed space made it all the more special. Hütter’s never ending quest is to bring music and visuals into one completely coherent work of art, hence the shows being presented in art galleries, and this leads to his constant reworking of the music to achieve the perfect marriage. This does have the advantage of refreshing those songs recorded over forty years ago, making for an exhilarating ride that has even converted my wife into a fan. As for me, I will be doing it all again on Sunday - “Musik - Non Stop”.

9 notes

·

View notes