#shawbridge reform school

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

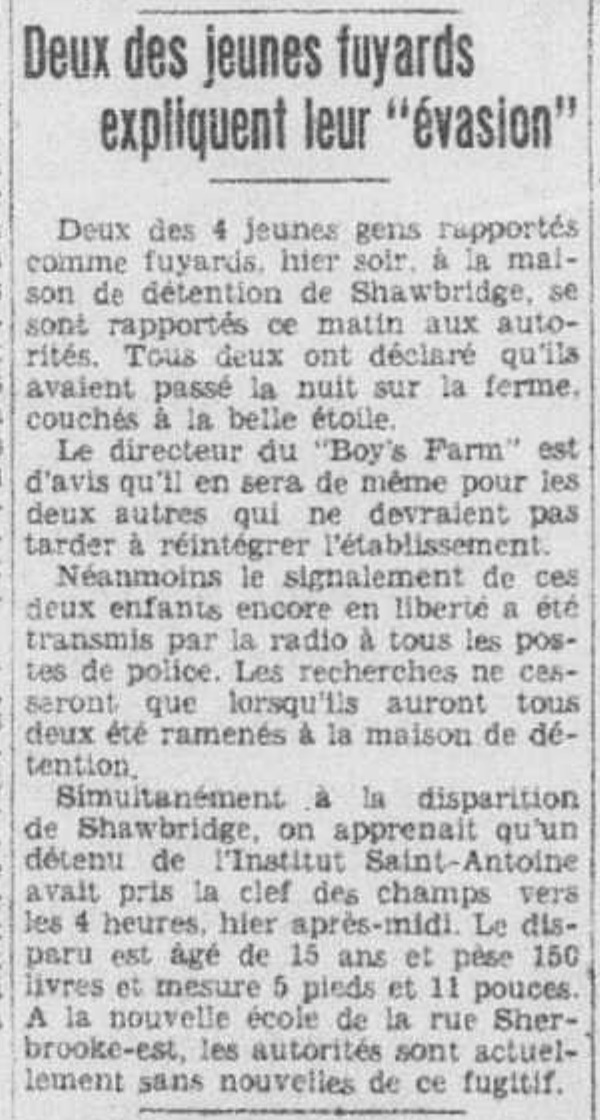

"Deux des jeunes fuyards expliquent leur "évasion"," La Presse. July 11, 1933. Page 3. ---- Deux des 4 jeunes gens rapportés comme fuyards, hier soir, à la maison de détention de Shawbridge, se sont rapportés ce matin aux autorités. Tous deux ont déclaré qu'ils avaient passé la nuit sur la ferme, couchés à la belle étoile.

Le directeur du "Boy's Farm" est d'avis qu'il en sera de même pour les deux autres qui ne devraient pas tarder à réintégrer l'établissement.

Néanmoins le signalement de ces deux enfants encore en liberté a été transmis par la radio à tous les postes de police. Les recherches ne cesseront que lorsqu'ils auront tous deux été ramenés à la maison de détention.

Simultanément à la disparition de Shawbridge, on apprenait qu'un détenu de l'Institut Saint-Antoine avait pris la clef des champs vers les 4 heures, hier après-midi. Le disparu est âgé de 15 ans et pèse 150 livres et mesure 5 pieds et 11 pouces. A la nouvelle école de la rue Sherbrooke-est, les autorités sont actuellement sans nouvelles de ce fugitif.

#montreal#prison break#escaped prisoners#escape from prison#shawbridge reform school#l’école de réforme de shawbridge#reform school#institut saint-antoine#youth delinquency#youth in the toils#juvenile justice system#juvenile detention#juvenile delinquency#great depression in canada#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada#wanderlust

0 notes

Text

"LORD BESSBOROUGH A SHAWBRIDGE," La Presse. June 19, 1933. Page 11. --- En haut, on voit Son Excellence lord Bessborough, gouverneur général du Canada, descendant du train, samedi après-midi en compagnie de M. E-W. Beatty, à Shawbridge, pour y présider la séance de fin d'année et de distribution de prix aux élèves de la Boy's Farm Training School [école de réforme de Shawbridge]. Son Excellence serra la main du principal de l'institution. En bas, un groupe de jeunes garçons acclamant avec enthousiasme les distingues visiteurs. (Photo C.P.R.)

#shawbridge reform school#l’école de réforme de shawbridge#reform school#montreal#anglo canadians#youth delinquency#youth in the toils#juvenile justice system#juvenile detention#juvenile delinquency#lord bessborough#governor general of canada#reform institutions#quebec prisons#great depression in canada#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada

0 notes

Text

"Boys' Farm Overcrowded," Montreal Star. April 7, 1943. Page 19. ----- Shawbridge Admissions Increased 100 Per Cent ---- The Shawbridge Boys' Farm is hopelessly overcrowded and with 100 new commitments this year and only 11 boys to be paroled the situation has now reached a crisis, declared Vernon McAdam, secretary treasurer of the Farm at a meeting today of the Westmount Rotary Club.

Juvenile crime is a "smallpox of behavior" and until a method is evolved to cure it, isolation must be the most important factor in its treatment, he added.

Outlining the work of the Boys' Farm, Mr. McAdam compared it to a hospital where the juvenile delinquent would be cured and, after a convalescent period, sent back into the business world, rehabilitated and ready to take his place as a useful citizen. He explained that boys were sent to the farm only after all community resources had failed to cure them.

Juvenile delinquency had increased commitments to the farm 100 per cent since the start of the war, the speaker pointed out and as a consequence the Shawbridge institution was now overcrowded Its problem has been accentuated since the Federal law of last November raising the age classification of juveniles from 16 to 18, he said.

#shawbridge reform school#l’école de réforme de shawbridge#reform school#montreal#anglo canadians#youth delinquency#youth in the toils#juvenile justice system#juvenile detention#juvenile delinquency#crime wave#reform institutions#prison overcrowding#canada during world war 2#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada

0 notes

Photo

“SHAWBRIDGE FARM SHOWS GOOD YEAR,” Border Cities Star. April 29, 1930. Page 5. --- Efficiency and Progress Mark Reports at Annual Meeting --- OFFICERS ARE NAMED --- E. W. Beatty is Re-elected President and Directors Are Also Chosen --- Announcement of a proposal to consider the question of erecting a school building with the provision of two or three workshops to train boys in the school, and the re-election of E. W. Beatty as president of the organization, featured the annual meeting of the Shawbridge Boys' Farm and Training School, held at the C. P. R. offices at Windsor Station, yesterday afternoon.

Mr. Beatty, after the reports of the administration committee, of which John McMillan is chairman, and of the secretary-treasurer and superintendent had been presented, declared that they were all highly satisfactory. The per capita cost had been reduced considerably and they could perhaps look forward to a further reduction. The farm was in an excellent condition and they were grateful to the public for the support that was accorded it. He particularly mentioned the Kiwanis and Rotary Clubs of Montreal for their continued assistance. Through the efforts of Mr. Newman and Mr. Dawson in collecting funds they were indebted to the public for their consistent support also, and he doubted if any institution such as theirs received better and more real and continuous support from citizens and organizations in Montreal than they did.

SEVERE LOSS Mr. Beatty said the members of the board had suffered a severe loss through the untimely death of Murray Williams. He was an earnest and devoted friend of the farm, enthusiastic in regard to the boys, and of great assistance to all.

The report of the administration committee was presented by Ernest Cousins, on behalf of the chairman, who was unable to be present. The report of the committee outlined the general improvements that had been made, and emphasized the spirit displayed by the boys, all of whom showed pride in their respective departments, and demonstrated the value of the character training that they were receiving. Major Willcock, with Mrs. Willcock and the staff had carried on fine constructive work among the boys and the committee had every reason to be gratified at the success of his efforts at Shawbridge.

Owen Dawson, presenting the secretary-treasurer's report. pointed out that subscriptions collected during the year amounted to $47,260, and expressed his gratitude to the public. The financial statement showed a substantial reduction of the bank overdraft, as well as a betterment in the operating costs of the institution, largely due to the careful administration of Major Willcock. He also showed that the Boys' Farm had reason to be proud of the record of the pupils and statistics showed that a very small percentage of graduates had been a charge on the community.

ACTIVITIES OUTLINED. Major Ralph Willeoek, in his report as superintendent, outlined the various activities of the school, where there are 133 boys in attendance. There had been nine graduates from the school directed by Miss E. Patterson, the principal, and these had received special commercial Instruction in their last term. Major Wilcock said the practice of giving privileges to deserving boys for good behaviour and granting allowances for faithful work had made a definite contribution to their good conduct and a spirit of contentment existed in the cottages and throughout the various departments. The facilities for the play life of the boys provided by the friends of the farm had been of great assistance, particular mention being made of the Rotary, Kiwanis and Hyland sports days and the Beatty gymnasium.

A definite step forward had been made in vocational training and many useful articles had been made in the carpentry shop started by Owen Dawson, and which would be extended through the efforts of John Molson.

The directors were re-elected on the motion of Norman Holland, seconded by A. D. MacTier, with the addition of Ross H. McMaster, who replaced the late Murray Williams, and John H. Molson, who succeeded his father, the late Fred Molson.

#shawbridge reform school#l’école de réforme de shawbridge#reform school#montreal#juvenile delinquency#youth detention#juvenile justice system#youth in the toils#reform institutions#protestant english quebec#anglo canadians#great depression in canada#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada

0 notes

Photo

“JEÛNE HOMME CONDAMNE A L’ECOLE D’INDUSTRIE,” La Presse. August 2, 1917. Page 02. --- Un jeune homme de 17 ans, Robert Stevens, arrêté par le chef McCarthy et le détective Adélard Importe, de la police du Grand-Tronc, pour vol au détriment de la compagnie, a été condamné par le juge Leet, siégeant en cour de police, à trois années à l’école d'industrie de Shawbridge. Stevens, si l’on en croit le détective Laporte, n'en est pas à ses premières armes dans le sentier du vice. Il aurait déjà été arrêté quatre fois par le policier.

#montreal#vice squad#stealing from the boss#reform school#juvenile delinquency#shawbridge reform school#l’école de réforme de shawbridge#protestant english quebec#juvenile court#reform institutions#young offenders#railway workers#grand trunk railway#sentenced to prison#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada#juvenile detention

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“FACES CHARGE OF MURDERING MAN AT WEEDEN,” Sherbrooke Daily Record. November 5, 1918. Page 07. --- Francis Mace Was Remanded to Jail Until Thursday Afternoon When He Will Come Up for Preliminary Hearing. --- Charged with murdering Paul Morin during the course of an argument at his home in Weeden, Francis Mace faced Judge Mulvena in the District Magistrate’s Court and was remanded for preliminary hearing on Thursday afternoon at one o’clock, while all witnesses to the murder were summoned to be present on that occasion. According to the information received Morin had been boarding with the accused and his family at Weeden for some time. In the afternoon Mace brought home quite a quantity of liquor and the men indulged in a drinking bout. It is claimed that, Mace then turned to one of his little children and kept giving the child so much liquor that it lost consciousness, and when it recovered the father attempted to give the child more liquor.

However the man’s wife objected to this and Morin is said to have taken her part. The result was that the two men came to blows and rolled to the floor. Agreed at the action on the part of Morin, whom it is stated he had not a great deal of love for, it is alleged that Mace retired to the kitchen and returned armed with an axe, with which he struck Morin on the head, inflicting a four-inch cut which crushed the man’s skull and killed him almost instantly, notwithstanding the efforts of his wife and daughter to stop him. Mace was charged with murder by the coroner’s jury, and later brought to Sherbrooke.

Sentenced to Five Years. Orin Gustus Provencher, of Smith’s Falls, a lad of thirteen years of age, was found guilty of the charge of arson laid against him by Charles Hughes, and sentenced to serve five years in the Shawbridge Boys’ Home. The evidence submitted brought out the facts that the boy had set fire to some pulp wood, which had it not been extinguished in time, would have caused Mr. Hughes a loss of $5,-000. The young lad was born at Stanstead and his father some time ago enlisted in the United States Army, while his mother secured a divorce and re-married a man by the name of Charles Dexaines, of Ayer’s Cliff. The boy for some time lived with his grandmother, but lately has been wandering about the country, and committed thefts from time to time of butter, eggs, etc., from the farmers who had employed him. Another Autoist Fined. G. A. Mclver, of Gould, was charged by Bissonnet and Oughtred, Provincial Revenue Collectors, with driving a motor vehicle while under the influence of liquor. He paid the fine of $100 and costs.

#sherbrooke#murder trial#murder#axe murderer#drunken assault#murderous rage#remand prisoner#sherbrooke jail#prison winter#smith's falls#shawbridge reform school#l’école de réforme de shawbridge#reform school#juvenile delinquency#youth in the toils#arson#histoire du québec#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada

0 notes

Photo

THE ISSUE OF OLDER BOYS In 1927, The Boys' Farm considered another strategy for increasing its population:

The Secretary [Owen Dawson] stated that The Boys' Farm might enlarge its sphere of usefulness if the juvenile age were increased from 16 to 18 years, as provided for in an amendment to the Juvenile Delinquents Act. The President [Beatty] felt that the matter might be taken up with the Federal Government some time in the near future (March 31, 1927).

Reform schools in other provinces had already opposed the policy of extending the jurisdiction of the juvenile court to include boys up to the age of 18 (rather than 16) and continued to oppose the policy in 1929 when the federal government revised the Juvenile Delinquents Act. The issue pitted the interests of existing reform schools against the zeal of juvenile justice reformers who wished to extend childhood status to older juveniles. In order to understand why reform schools elsewhere in Canada resisted the age extension policy and why The Boys' Farm temporarily considered its advantages, it is necessary to look at the effects of juvenile court practices on the populations of reform schools.

The Montreal juvenile court's extensive use of probation radically reduced the number of children committed to reform schools during the early 1920s. However, many children originally placed on probation got into trouble again and were older when judges subsequently decided to send them to reform schools. The court's practice of probation, in other words, eventually produced an upturn in the number of children committed to reform schools. And because these children were older (often having failed more than once on probation), the court's practice of committing children only after they had spent time on probation resulted in older populations at reform schools.

While the juvenile court's jurisdiction was limited to children under 16, the practice of probation in combination with the court's right to supervise the children who appeared before it up to the age of 21 made it possible for the court to commit children who were 16 years and older to reform schools:

The authority of the juvenile court to impose sanctions does not end with the original disposition of the child. Provision is made in the Act to bring the child back before the court at any time before he has reached the age of twenty-one years. This is extraordinary since the maximum age for original jurisdiction is sixteen or eighteen years of age .... This provision is often invoked when a child has been placed on probation and has subsequently breached one of the conditions of supervision (Wilson, 1982:194).

The aging of reform school populations was evident at The Boys' Farm during the mid-1930s. At that time, the jurisdiction of the Montreal juvenile court was still limited to boys under the age of 16; yet Boys' Farm records for boys discharged during the late 1930s show that 23 out of 143 boys were 17 and older on their sentencing date. Thirty-three more were aged 16, though they may have committed their offense prior to their 16th birthday. The aging of reform school populations occurred earlier in provinces such as Ontario where well-developed probation services were in place before the juvenile court was created. When the federal Minister of Justice, Ernest Lapointe, (at the urging of the Canadian Council of Child Welfare and other juvenile justice reformers) introduced an amendment to the federal Juvenile Delinquents Act in 1921 which would raise the age of juveniles from 16 to 18, Ontario's reform schools were in a different position to appreciate its consequences than were Quebec's reform schools. The Boys' Farm could appreciate the potential advantages of an age extension as a way of reversing the decline in its population (as the board's discussion of the amendment in 1927). Ontario's reform schools, on the other hand, saw the age extension as a policy that would simply exaggerate the process already at work: namely, the commitment to their institutions of an increasingly older group of repeat offenders. Their position was that the age extension should wait until new and more prison-like reform schools were created specifically for this older group. (The borstal schools in England were favored as a model.) Their resistance to the amendment successfully blocked the proposed mandatory extension of age. Instead, the amendment granted discretionary authority to provinces to extend the age from 16 to 18..

The age extension continued to pit the interests of reform schools against those of juvenile justice reformers. In 1938, The Royal Commission to Investigate the Penal System of Canada completed two years of hearings and investigations into the Canadian penitentiary system, including the system for dealing with juvenile offenders. The Archambault Report (named after the chairman of the commission) said:

Many conflicting representations were made to the Commission as to whether the age limit of those to come under the jurisdiction of the juvenile courts should be raised throughout Canada to include young persons below the age of eighteen years. Your Commissioners are definitely of the opinion that the jurisdiction of the juvenile courts should be limited to children below the age of sixteen years .... The problem of detention homes and training schools would be clearly aggravated, and, in our opinion, has been aggravated (in British Columbia and Manitoba) where the age limit has been increased.

By this time, The Boys' Farm was enjoying a population boom. Its superintendent, Major Willcock, told the administration committee:

A great many more boys were appearing repeatedly in the Juvenile Court before being sent to The Farm, resulting in boys coming to the School at the ages of 15 or 16 and generally for longer terms. It was suggested that more boys might be sent by the Juvenile Court and for shorter terms. Mr. Dawson undertook to take the matter up with the Juvenile Court authorities (Administration Committee minutes, November 24, 1938).

At this point, The Boys' Farm administrators were beginning to perceive older boys sent for longer terms as "hard core" and more troublesome residents. They began to favor shorter terms, therefore, in the hope that the court would send younger and less troublesome boys. When Quebec extended the juvenile age from 16 to 18 in 1942, The Boys' Farm was already crowded. The influx of older boys over the next several years, amplified by the court's practice of turning to reform school commitments during wartime, added to the internal problems of control that already existed as a result of overcrowding and an older population. The number of runaways rose (and, incidentally, divided the board on the issue of whether to pursue runaway boys who wished to enlist in the army); the use of corporal punishment continued to rise; and concern mounted over the exposure of younger boys to the influence of older boys more experienced with crime. When the Second World War ended and reform school commitments fell to pre-war levels, The Boys' Farm administrators saw a second, and more fundamental, consequence of the age extension. Because the court sent older boys to The Boys' Farm (and to the other reform schools for French-speaking children), it was increasingly reluctant to commit younger boys there, where they would be exposed to the influence of older boys. By 1948, the population at The Boys' Farm had dwindled to about 100 boys, and it was fast becoming the last resort for the hard-core, older offender that it had originally set out not to be. Moreover, The Boys' Farm had long since come to appreciate what Ontario's reform schools appreciated in 1921: namely, that as an increasingly older group of juveniles were defined as children rather than as adults, and sent to reform schools rather than to adult jails and penitentiaries, existing reform schools would have to become juvenile prisons unless or until newer juvenile prisons for this older group were created. Even then, reform schools, if they were to survive, would have to lay new claim to the younger, "normal delinquent" boys they had lost and would continue to lose as the result of probation, foster homes, short-term sentences, and other decarcerating measures.

- Prue Rains, McGill University, “Juvenile Justice and the Boys’ Farm: Surviving A Court-Created Population Crisis, 1909-1948.” Social Problems, Vol. 31, No. 5, June 1984. pp. 509-12 Photographs are both Conrad Poirier, “Boy’s Farm and Training School, Shawbridge.” 1947-11, P48.S1.P15234 & P48.S1.P15221, BAnQ.

#shawbridge reform school#l’école de Réforme de Shawbridge#reform school#juvenile delinquency#protestant english quebec#youth delinquency#youth in the toils#juvenile justice system#probation#parole violations#history of quebec#juvenile court#indeterminate sentence#repeat offenders#long sentences#young offenders#what is the child#redefining youth upwards#institutional crisis#reform institutions#crime and punishment#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada#montreal

1 note

·

View note

Photo

THE INDEFINITE SENTENCE The federal Juvenile Delinquents Act (1908) did not mention the indefinite sentence directly; nor did the detailed commentaries on the federal legislation by its authors and promoters. And since the Quebec legislation (1910) simply proclaimed the federal act as relevant to Quebec and authorized the creation of a juvenile court in Montreal, it also did not mention the indefinite sentence directly. But definite sentences were not mentioned either. Juvenile justice reformers, and the text of the legislation itself, so clearly favored methods for dealing with children other than incarceration that the commitment of children to reform schools was itself scarcely mentioned. The indefinite sentence was, nevertheless, a core tenet in the movement to reform children rather than to punish them. It was implicit in the discretionary powers and wardship hold over children given to the juvenile court by the act, and in the law's provision that the court should not authorize a child's release without a recommendation from the reform school. This provision was intended to permit reform schools to release children when successfully reformed rather than at some arbitrary date; fully implemented, this provision would have transferred control over the length of children's sentences from the juvenile court to the reform school. Judges at the Montreal juvenile court were reluctant to sentence children to indefinite terms. In 1922, Superintendent Barss of The Boys' Farm observed at a board meeting that the indefinite sentence was not being used by judges at the Montreal juvenile court; and in 1924, the secretary-treasurer, Owen Dawson, reported that the newly appointed judge of the Montreal court was "not a believer in the Indefinite Sentence as provided by the Juvenile Delinquents Act" (January 31, 1924). Judges at the Montreal court were not only trained as lawyers but still worked in courts other than the juvenile court; they continued to adhere to an older model of justice, and were reluctant to turn their control of sentence length over to reform schools. The Boys' Farm began to lobby for the indefinite sentence in 1922. In March, E. W. Beatty, president of The Boys' Farm, reported to the board that:

He had gone into the question of the indefinite sentence with [premier] Taschereau, the Provincial Secretary, and Sir Lomer Gouin [former premier], all of whom were in favor of the plan (March 8, 1922).'

It may seem odd that the board of directors first approached executive rather than legal or judicial authorities about implementing indefinite sentences. Eventually the board did seek a legal interpretation of the Juvenile Delinquents Act (1908). Because the act was federal legislation enacted provincially by executive proclamation, however, there was some ambiguity about which authority was responsible for interpretation of the act. The board's initial approach also reflected its own contacts and prior experience with provincial authorities about institutional matters. These were customarily handled by the provincial secretary. The Boy's Farm favored indefinite sentences for two reasons: to increase its control over troublesome inmates; and to counter the effects of short sentences on its population [and thus its revenue].

INTERNAL CONTROL In part, The Boys' Farm's preference for the indefinite sentence was an extension of its earlier efforts to gain control over the decision to release or parole. In the early 1900s, all reform schools in Quebec objected to government pardons as a form of early release, arguing that early release (parole) should depend on good conduct alone. Definite sentences limited the effectiveness of parole as a device for maintaining internal control; in fact, the most troublesome boys, by definition, were the most likely to be still at The Boys' Farm when their sentences expired. In the early 1920s, The Boys' Farm made persistent and largely unsuccessful attempts to persuade the provincial secretary to extend the sentences of boys "unfit for discharge." For example:

The Superintendent submitted a list of 14 boys whose time expires before the close of this year and who were entirely unfit for discharge. He recommended that the provincial Secretary be requested to extend their terms. The President [Beatty] reported that he had an appointment with the Hon. Mr. David [the provincial secretary] for the following morning, when he would request him to grant a temporary extension of the terms of the boys referred to until their cases could be more carefully studied (June 21, 1922).

Four months later, Beatty reported:

The request for the extension of the terms of the 14 boys at The Farm had been refused by the Provincial Secretary. The question had [subsequently] been a matter of serious discussion between himself [Beatty] and [Taschereau] and the Hon. Walter Mitchell [provincial treasurer]. The [premier] requested that in future all such matters be taken up direct with him (October 26, 1922).

Because The Boys' Farm only occasionally succeeded in having the sentences of individual boys extended, it turned to the indefinite sentence as a method for gaining control over the release, and therefore conduct, of its more troublesome boys. INCREASED POPULATION The population at The Boys' Farm could be increased either by more court commitments or by longer sentences. Attempts by The Boys' Farm to lengthen the sentences of boys it regarded unfit for discharge addressed the issue of population as well as the issue of internal control. But The Boys' Farm was concerned with the length of sentences for another reason, too. The Montreal juvenile court was increasingly implementing the principles of the juvenile justice movement. Not only was it placing more boys on probation rather than committing them to reform schools, but it was also reducing sentences for those it did commit from the previous three-to-five years down to two years or less. Shorter sentences added to the population troubles created by the greater use of probation. While the board of directors could not reasonably hope to increase the number of boys committed to The Boys' Farm by opposing the use of probation, it could at least hope to increase the population by invoking the Juvenile Delinquents Act of 1908 to gain control over the lengths of their sentences. Faced with continuing resistance on the part of judges to the use of the indefinite sentence, The Boys' Farm planned a legal challenge to the definite sentence in 1924. Walter Mitchell, provincial treasurer under both Gouin and Taschereau and, by this time, a member of the board of directors at The Boys' Farm, offered to seek the legal opinion of his former law partner, N. K. Laflamme, and to take the matter up with Quebec's attorney general. In February, 1924, Laflamme reported to the board that he:

. . . believed that the Judge of the Juvenile Court had the option of giving an indefinite sentence under the Juvenile Delinquents Act, or a definite sentence of not less than two or more than five years under the old Prisons and Reformatories Act. Mr. Laflamme stated that, in his opinion, any definite term of less than two years was illegal (February 28, 1924).

The board agreed to take the matter up with the attorney general after the legislative session ended in Quebec, and once a "parole board" had been created within The Boys' Farm "to deal with the discharge of committed cases" (March 27, 1924). The Boys' Farm eventually established procedures for allocating parole and a committee that reviewed boys for parole, but not until the 1940s when it had acquired control over the release date of boys (even then, the control was within the limit set by the definite sentence). The plan to establish a "parole board" in 1924, therefore, was something of a rhetorical device designed to express a form of control over sentences that The Boys' Farm hoped for but did not have.

Four months later the board planned to convey the legal opinion it had solicited to the Montreal court:

The question of short-term sentences was discussed and it was agreed to admit boys from the Juvenile Court for short terms in the meantime. The Secretary was asked to convey the opinion of Mr. N. K. Laflamme in this connection to the Juvenile Court authorities and if no satisfactory conclusion was reached to take the matter up with the Hon. Walter Mitchell (June 26, 1924).

In May, 1925, the board took action to resist admission of boys for terms shorter than one year: The question of admitting short-term cases from the Juvenile Court was discussed, and it was decided to request the Judge of the Court not to send boys for a shorter period than one year (May 28, 1925). These shorter sentences also decreased the populations of reform schools because they were served in detention homes rather than reform schools. Schlossman observes: "While the juvenile court sent relatively few children to reformatories, it held large numbers on short-term sentences in the detention center before, during, and sometimes after trial." In the absence of adequate detention facilities, the Montreal court held both French-speaking and English-speaking children at the Montreal Reformatory (the French reform school for boys). The large number of children held there "provisionally for inquiry" suggests that during the 1920s the Montreal court used short-term detention in much the same way-that is, as an alternative to outright commitment to reform schools.

In May, 1925, the board took action to resist admission of boys for terms shorter than one year:

The question of admitting short-term cases from the Juvenile Court was discussed, and it was decided to request the Judge of the Court not to send boys for a shorter period than one year (May 28, 1925).

The Boys' Farm was not successful in convincing the court to use the indefinite sentence, but it did persuade the court to extend definite sentences. Records for boys discharged from May, 1939, to May, 1941, (and who were therefore sentenced in the mid-1930s) show that boys were sentenced for definite rather than indefinite terms. None of the 143 sentences, however, were for less than two years and most were for three, four, and five years (the mean sentence was 3.67 years). The Boys' Farm appears, therefore, to have been successful in temporarily allaying the threat of short sentences." And it was successful in acquiring recognition of its right to be consulted by the court regarding the actual release date of sentenced boys:

Colonel Magee [a board member] reported that he had had a very satisfactory interview with Judge Lacroix [of the Juvenile Court] in reference to the releasing of the Wilson boys [two brothers]. The Judge has promised that he would not release any more boys without first asking for a report from the Farm management (October 30, 1924).

By 1930, the population crisis was over at The Boys' Farm and the province's other reform schools (the largest of these were the two French reform schools in Montreal, also supplied by the Montreal juvenile court). From 1930 to 1945, the population of the province's reform schools reached record levels; at The Boys' Farm it reached more than 200. While longer sentences contributed to the rise, increased court commitments were the major factor. In 1927, the number of court commitments to The Boys' Farm had risen to pre-1920 levels and continued to climb. The population crisis had passed, but not primarily as the result of lengthened sentences.

- Prue Rains, McGill University, “Juvenile Justice and the Boys’ Farm: Surviving A Court-Created Population Crisis, 1909-1948.” Social Problems, Vol. 31, No. 5, June 1984. pp. 505-09

Photographs are both Conrad Poirier, “Boy's Farm and Training School, Shawbridge.” 1947-11, P48.S1.P15232 & P48.S1.P15235, BAnQ.

#shawbridge reform school#l’école de Réforme de Shawbridge#reform school#juvenile delinquency#protestant english quebec#youth delinquency#youth in the toils#juvenile justice system#probation#parole#history of quebec#juvenile court#indeterminate sentence#long sentences#young offender#population control#population crisis#institutional crisis#reform institutions#build it and they don't come#the institution working for itself#crime and punishment#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada#montreal

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“The Boys' Farm and Training School was founded in 1908 in Shawbridge, some forty miles northwest of Montreal, by a group of philanthropic Protestant Montreal businessmen. Built on the "cottage model" and in the countryside, it was intended to reform Protestant delinquent boys in a non-prison setting through outdoor work and living. There were no locked doors and no fences, and the boys spent their days doing farm work (5 hours a day) and going to school (3 hours a day). It was the province's only reform school for non-Catholic, non-French-speaking delinquent boys. It received all of the province's court -committed, non-French-speaking delinquent boys (including children of immigrants who ... came to populate reform schools during times of high immigration). The Boys' Farm benefited from the charitable involvements and sense of mission of Montreal's wealthy and influential Protestant male business elite. The Province of Quebec established its first juvenile court in Montreal in 1912. The Juvenile Delinquents Act, which authorized provinces and cities to establish juvenile courts, was passed by the federal government in 1908. The Province of Quebec's Act Respecting Juvenile Delinquents was passed in 1910. The Montreal juvenile court was the province's only juvenile court until the early 1940s. It was, therefore, the sole supplier of boys to The Boys' Farm. It sent French-speaking delinquent children, to two reform schools in Montreal run by Catholic orders, and English speaking delinquent girls to The Girls' Cottage School. In theory, the court was committed to placing children on probation rather than in reform schools. In practice, however, it did both, and benefited existing reform schools by expanding their populations, facilities, and budgets. ...over the first eight years of the court's operation, the number of children in reform schools rose steadily from 367 in 1911 to 678 in 1919. The court's initial failure to substitute probation for incarceration seems to have been a result of the First World War. The reform school population rose dramatically during the latter years of the war when the court provided a new resource for controlling the wayward children of absent fathers and working mothers. The effects of the court's operation on The Boys' Farm were especially pronounced; from 1911 through 1919, the population more than tripled, from 42 to 133. And because The Boys' Farm received a per diem subsidy from the provincial government for each court-committed boy, its expanding population brought in increased revenue from the province. The court did not have a negative effect on reform school populations until the early 1920s. In the court's early years, which coincided with the First World War, the court both put children on probation and placed children in institutions. By the early 1920s, however, probation had clearly become the court's preferred response. Court statistics for 1921 show that while the number of children appearing before the court had increased since 1915, the number of children sent to reform schools declined from 159 in 1915 to 92 in 1921. In 1924, Judge J. 0. Lacroix of the Montreal juvenile court said:

My first duty is to try to reform the boys and girls through themselves, and I have hundreds under the supervision of my officers, and many come regularly and report to me. I give them a little talk privately, and in that way help them along the right road. If after a trial of this system I find it is impossible to cure them I will send them away (Montreal Star, 1924).

The impact of probation on reform school populations and budgets was serious. During 1921, the number of boys committed by the Montreal juvenile court to The Boys' Farm dropped by half - from 30 to 15 - and did not reach the former level again until 1927. From 1921 through 1927, The Boys' Farm faced a population crisis which it, like other reform schools, attributed to the use of probation; in 1923, a member of the board of directors of The Boys' Farm observed, following a visit to two training schools in New York State:

The superintendents of both schools report that the number of boys sent them has declined and this is due to the influence brought to bear on the judges by social workers and others to give the boys more chances on probation (Montreal Star, 1923).

Faced with a dwindling population and revenue, The Boys' Farm's board of directors brought its considerable influence to bear on the provincial government. Their activities shed light on the role of business and ruling-class interests in the shaping of criminal justice policy, and of juvenile justice policy in particular. The board of directors was composed of members of the Montreal business elite. ...while they worked hard to influence juvenile justice policy, particularly on behalf of the indefinite sentence-these efforts more clearly expressed their commitment to making a pet charity work than an ulterior interest in turning delinquent boys into docile and disciplined industrial workers. That is, board members volunteered their services as a matter of conscience, and out of a general - and increasingly inaccurate - view of The Boys' Farm as an alternative to prison for young, wayward, and still reformable boys. Specifically, what they had to offer as board members was their social contacts and know-how in making enterprises work. In this sense, they employed their values and skills to ensure the financial viability and continued existence of The Boys' Farm, rather than to affect the boys themselves.” - Prue Rains, McGill University, “Juvenile Justice and the Boys’ Farm: Surviving A Court-Created Population Crisis, 1909-1948.” Social Problems, Vol. 31, No. 5, June 1984. pp. 502-04

Photographs are both Conrad Poirier, “Boy's Farm and Training School, Shawbridge.” 1947-11, P48.S1.P15229 & P48.S1.P15230, BAnQ.

#shawbridge reform school#l’école de Réforme de Shawbridge#reform school#juvenile delinquency#protestant english quebec#youth delinquency#youth in the toils#juvenile justice system#probation#parole#history of quebec#juvenile court#young offenders#population crisis#reform institutions#institutional crisis#build it and they don't come#crime and punishment#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada#montreal

0 notes

Photo

“LES ISIDORE SONT ARRETES,” La Patrie. November 13, 1917. Page 03. --- Condamnés à un mois de prison pour vagabondage à Welland Ont. Ils sont reconnus comme les évadés du bureau de la Sûreté de Montréal. --- Rapport aux commissaires --- Un télégramme du chef de police de Welland, Ontario, a été reçu ce matin au bureau de la Sûreté annoncent l’arrestation dans cette ville des frères Isidore qui s’étaient évadés de leur cellule au bureau de la Sûreté à Montréal. Les frères Isidore ont été arrêtés sous l’accusation de vagabondage et condamnés à un mois d’emprisonnement. On les reconnut par leur protographie qui avait été envoyée aux autoritées policières de toutes les villes du Canada. Samuel et Lionel Isidore qui sont incriminés dans les attentats meurtriers et les vols commis au préjudice du bijoutier McKinley, s’étaient évadés en compagnie d’un jeune homme qui était accusé d’un cambriolage et qui occupait la même cellule qu’eux à la Sûreté.

Jeffrey ou Geoffroy ainsi qu’il nommerait en réalité, a été repris depuis à Saint-Hyacinthe. Ce matin, il a été condamné à subir son procès. Lors de leur arrestation les Isidore avaient consenti à faire des aveux complets, incriminant une jeune femme du nom de Della Rivers dit Rivest et les nommés Moe Richstonne, Isidore Cohen et Joseph Tétrault qui furent subséquemment arrêtées. Ce matin ces prétendus complices ont été condamnés à subir leur procès. Quant aux frères Isidore ils seront ramenés à Montréal pour y subir leur procès. Le chef Campeau a fait rapport de leur arrestation au bureau des Commissaires. On sait que le commissaire Ross avait tenu à faire personnellement une enquête sur l’évasion des Isidore. Ces derniers étaient parvenus à s’échapper en sciant un barreau en fer. En dépit de leur jeune âge - ils ont à peine une vingtaine d’années - les frères Isidore sont de redoubtables bandits au dossier des plus lourdement chargés. Nous avons déjà donné à plusieurs reprises le détail des audacieux vols accompagnés de tentatives de meurtre dont le bijoutier McKinley a été la victime.

#évasion#cambrioleur#histoire de Montréal#service de police de la ville de montréal#bandits#robber#jail break#la sûreté#les frères Isidore#samuel isidore#lionel isidore#joseph jeffrey#armed robbery#break and enter#forçats#juvenile delinquency#youth delinquency#youth in the toils#world war 1 canada#shawbridge reform school#l’école de Réforme de Shawbridge#crime and punishment#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada

0 notes

Photo

“L’un Des Evades Comparait Ce Matin,” La Patrie. November 2, 1917. Page 03. “Joseph Jeffrey qui s’est évadé du bureau de la Sûreté avec les frères Isidore, a été arrêté à Saint-Hyacinthe et ramené à Montréal par le détective Crowthers.

Il a comparu ce matin devant le magistrat de police. Il est accusé d’avoir commis un vol de $800 de marchandises chez un marchand du boulevard Saint-Laurent, et de s’être évadé de sa prison. L’enquête a été renvoyée au 7.

Les frères Isidore n’ont pas encore été repris. Jeffrey a fait certaines déclarations à la police sur les agissements de ses compagnons après leur évasion mais on accorde peu de créance à ses dires.

L’inspecteur Connors et le dêtective Nazaire Forget sont revenus hier après-midi d’une tournée d’investigations qu’ils ont faite à différents endroits passé Saint-Lambert sur la route de Saint-Hyacinthe, mais nulle part des frères Isidore n’ont été aperçus. A Saint-Hyacinthe, Jeffrey a été appréhendé par le chef Foisy, son assistant Bourgeois et les constables Sénécal et Beauregard. Il était chez un parent domieillié rue du Grand Tronc.”

#évasion#cambrioleur#histoire de Montréal#service de police de la ville de montréal#bandits#robbe#jail break#la sûreté#les frères Isidore#samuel isidore#lionel isidore#joseph jeffrey#armed robbery#break and enter#forçats#juvenile delinquency#youth delinquency#youth in the toils#world war 1 canada#shawbridge reform school#l’école de Réforme de Shawbridge#crime and punishment#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada

0 notes

Photo

“L’EVASION DES FRERES ISIDORE,” La Patrie. October 31, 1917. Page 03. --- Ce matin, le commissaire Ross et le chef Campeau font une enquête personnelle et un examen des quartiers du bureau de la Sûreté. --- La nuit de l’évasion --- A la demande du commissaire Ross les secrétaires du service de la Sûreté ont préparé joer après-midi un rapport sur l’évasion des frères Isidore et d’un co-détenu du nom de James Jeffrey. Ce matin, accompagné du chef Campeau, le contrôleur est allé fair un examen des ileux. On lui a montré le barreau qui avait été scié, la cellule que les bandits occupaient. Le commissaire fait personnellement son enquête.

On sait maintenant que la sensationnelle évasion a eu lieu vers minuit. Entre minuit et une heure, une femme téléphons au bureau de la Sûreté et demanda à parler au détective Thibault. Cette femme était la tenancière d’un garni de la rue Sainte-Elisabeth qui tenait à savoir si Jeffrey et ses compagnons avaient été remis en liberté ou s’ils s’étaient échappés.

Jeffrey et un autre individu du nom de Roméo Lafleur avaient été arrêté vendredi derier par les détectives Walsh et Thibault sous l’accusation d’avoir commis un vol avec effection au préjudice d’un négociant du boulevard Saint-Laurent du nom de Samuel Rosenbaum. Les deux inculpés appréhendés au No. 41a de la rue Saint-Elizabeth. Après s’étre évadés du quartier général de la Sûreté Jeffrey et ses compagnons se rendirent rue Ste-Elizabeth où Jeffrey avait demeuré. Partant de là les fugitifs s’engagèrent ensuite dans la rue Lagauchetière et prirent ensuite par la rue Saint-Denis jusqu’à la rue Ontario. On a pu les retracer jusque-là.

Le détective Lamont qui était en ccharge de la surveillance des détenus ce soir-là, fut occupé vers minuit à aller écrouer des prisonniers aux ceullules du poste central au sous-sol de l’annexe de l’hôtel de ville. C’est probablement durant son adsence que les détenus s’enfuirent. L’officier a déclaré qu’il s’était endormi vers une heure. Il se leva le matin à six heures pour aller à la messe. It était censé attendre d’étre relevé de ses fonctions vers huit heures. Il est probaable que les investigations du commissaire Ross conclueront à la condamnation d’un systême qui oblige un détective d’être à sa besogne pendant trente-six heures. Un autre point importante de l’affaire est que advenant le fait que les frères Isidore ne seraient pas retrouvés d’içi quelques jours leurs coaccusés qui sont au nombre de quatre seront forcément acquittés. Les frères Isidore avaient fait des aveux complets qui permireng d’opérer l’arrestation de ces prévenus. Les témoignages des délateurs constituaient la preuve principale de la poursuite. Les frères Isidore disparas l’édifice de la preuve s’écroule. En ontre une fois étargis les accusés ne peuvent plus être incriminés sur les mêmes faits.

#évasion#cambrioleur#histoire de Montréal#service de police de la ville de montréal#bandits#robbers#jail break#la sûreté#les frères Isidore#samuel isidore#lionel isidore#armed robbery#break and enter#forçats#juvenile delinquency#youth delinquency#youth in the toils#world war 1 canada#shawbridge reform school#l'école de Réforme de Shawbridge#crime and punishment#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada

0 notes

Photo

“Les Agresseurs Du Bijou-Tier McKinley S’Evadent,” La Patrie. October 29, 1917. Page 03. --- La nuit dernière avec un co-detenu les frères Isidore, forçats libérés et bandits des plus redoutables, acient un barreau en fer au bureau de la Sûreté et gagnent le sol à l’aide de leurs draps de lit. --- Les frèrs Isidore possèdent un dossier extraordinatrement chargé. A l’âge de huit ans l’un d’eux cambriolait des établissements de commerce. --- A qui la responsabilité? --- Les frères Isidore, les agresseurs du bijoutier McKinley, deux des plus redoutables bandits que la police connaisse, se sont évadés la nuit dernière d’une cellule du bureau de la Sûreté à l’annex de l’Hôtel-de-Ville où ils étaiet détenus avec un autre prévenu du nom de James Jeffrey qui les a suivis dans leur fuite.

Pour s’échapper les malfaiteurs ont scié un barreau en fer d’un chassis ouvrant à la hauteur du second étage sur la rue Saint-Louis. Avec leurs draps et couvertes de lit attachés à un autre barreau ils purent ensuite assez facilement se glisser jusqu’au sol. Les deux Isidore, Samuel et Lionel, ont été arrêtés il y a une quinzaine de jours parl les détectives Morrel, Mercier, Weston et French sous l’accusation d’avoir pris part aux deux tentatives de meutre accompagnées de vol dont le bijoutier Samuel McKinley de la rue Sainte-Catherine fut en l’espace d’un mois la victime. A la suite de leurs aveux les détectives mirent en arrestation les nommés Joseph Tétrauit, Moe Richestone, Max Cohen et la femme Zella Rivest.

L’enquête pré;o,omaore dans cette affaire devait s’ouvrir ce matin devant le juge Saint-Cyr. A 11.30 hrs Mtre Lyon Jacobs qui occupe pour la poursuite demanda un ajournement. Les principaux inculpés s’étaient évadés des quartiers de la police.

Plusieurs avocats représentent la défense dans ces causes. Mtre S. W. Jacobs, C.R., défend le prévenu Moe Richstone, le seul qui ait réussi à recouvrer sa liberté sous cautionnement. Les autre avocats de la défense sont James Crankshaw, Jr., Mtres F.-N. Biron et Jules Delorimier. A la suite des circonstances le Juge St-Cyr a ajourné l’instruction à lundi prochain. En attendant la femme Rivest et Joseph étrault demeureront à Bordeaux. L’avocat de la poursuite a appuyé sur ce point. Les cellules du bareau de la Sûreté ne sont plus sûres. Nous disions plus haut que les frères Isidore étaient de redoutables criminels. Voici leur dossier. ‘Sammy’ Isidore a été arrêté en 1907 pour vol avec effraction; sentence fut suspendue en ce case. En 1909, il comparaissait à nouveau devant le tribunal pour vol: sentence suspendue. La même année, nouvelle arrestation pour cambriolage; sentence suspendue. En 1910, nouvelle arrestation pour cambriolage: sentence suspendue. La mème année, arrêté pour cambriolage: condamnation à trois ans de réclusion. En 1911, Sammy Isidore avait trouvé moyen de recouvrer sa liberté puisqui’il était mis une fois de plus en arrestation pour cambriolage et condamné à cinq ans de réclusion.

Il avait alors 16 ans et fut interné à l’école de Réforme de Shawbridge. Il s’y retrouva avec son frère Lionel qui purgeait une condamnation pour vol et tous deux combinèrent une évasion qui réussi. Mais la même année Sammy Isidore était réarrêté et condamné à deux ans d’emprisonnement. Enfin en 1916 il comunettait un vol avec violence sur la personne d’une jeune homme du nom de Leslie Fox qui en plein jour dans une bâtisse de l’Université McGill était volé d’une somme de $150. Pous ce méfait Isiddore fut condamné à trois ans de bagne. Il ne devait pas y séjourner longtemps. Le 1er octobre il bénéficiait d’un ‘ticket of leave’ d’une mise en liberté conditionnelle.

Lionel Isidore, le frèrer de ‘Sammy’, a commis son premier vol à l’âge de huit ans, en 1907. En 1909, il était arrêté pour la seconde fois pour cambriolage. Il bénéfis d’un verdict de sentence suspendue.

Il fut ensuite arrêté en 1913 pour cambriolage: sentene suspendue. En 1914, il est envoyé à Shawbridge pour une période de deux ans pour vol. Il s’évada avec son frère. Le troisième évadé James Jeffrey a été arrêté vendredi dernier par les détectives Thibault et Walsh sous l’accusation de s’être introduit avec un compagnon du nom de Roméo Lafleur dans l’établissement de Salmon Berinbaum au No 723 de la rue Saint-Laurent et d’y avoir dérobé $800 de marchandises. Ce n’est pas la première évasion qui a lieu au bureau de la Sûreté. En descellant un barreau un noir s’est déjà échappé de sa cellule. Les barreaux en question sont d’un pouce d’épaisseur et en fer malléable faciles à scier. C’est le travail de cinq minutes avec un bon outil.

La nuit il ya quatre agents de garde au bureau de la Sûreté. Trois se couchent dans l’attente des appels qui peuvent les envoyer sur le théâtre d’un vol ou d’un crime.

Le quatrième est censé monter la garde toute la nuit et surveiller les détenus. La nuit dernière c’est le détective Lamont qui remplisssait ces fonctionss.

Tour à tour les détectives font cette nuit de surveillance entre leur besogne régulière du jour et celle du lendemain. La tâche est surhumaine. L’officier succombe au sommeil/ C’est ce qui est arrivé la nuit dernière et les malfaiteurs en ont profité. C’est le système qui est à blâmer.

Comment les évadés se sont-ils procuré la scie qui leur a permis the s’enfuir? Les détenus ne sont pas censés à mois de circomstances spéciales, recevoir de visites.

#évasion#cambrioleur#service de police de la ville de montréal#bandits#jail break#la Sûreté#les frères Isidore#samuel isidore#lionel isidore#armed robbery#break and enter#juvenile delinquency#youth delinquency#youth in the toils#world war 1 canada#shawbridge reform school#l’école de Réforme de Shawbridge#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada#montreal

0 notes

Photo

“City and District,” Montreal Gazette. June 30, 1911. Page 03. --- Newsies Celebrate President Pete Murphy’s Birthday With Drive Through City. --- BOYS GO TO REFORMATORY. --- Young Incendiaries Sharply Dealt With by Judge Lanctot - Stiff Fine for Gamblers. --- Yesterday was the fifty-seventh birthday of Pete Murphy, Montreal’s veteran newsboy, who has been selling papers in this city for over half a century, having commenced to sell copies of The Gazette in St. James street when he was six years of age. The Montreal Newsboys Protective Association, of which ‘Pete’ is president, celebrated the veteran’s birthday in a becoming manner. They enjoyed a drive around the city last night in two big busses, each drawn by four horses, with the president perched high on the front seat of the leading ‘bus, wearing his silk hat and the cane Sir Wilfred Laurier brought him from Ireland. The sides of the ‘busses were bulging out like watermelons with their loads of boisterous youngsters, each of whom carried a horn and tooted from the time the drive started early in the evening until the end came shortly before midnight. The newspaper offices were visited, and each was cheered in turn, but when The Gazette Office was reached at 11 o’clock, President Murphy made a speech, in the course of which he told the youngsters of having sold The Gazette in St. James street, 51 years ago, when the largest building on the thoroughfare was the Ottawa Hotel, which still stands on the south side of the street just east of McGill. At The Gazette building the veteran presented a bouquet to the editor. --- BOY INCENDIARIES DISCOURAGED. The existence of a gang of juvenile incendiaries in the neighborhood of Point St. Charles around the Grand Trunk yards was the subject of severe comment by Judge Lanctot yesterday when hearing proceedings against three youths named John Collins, James Mailloy and Raymond Banford, charged with having set fire to piles of lumber, the property of Shearer, Brown & Wills, on the 22nd and 25th of May. Two other youth youths, Thos. Mitchell and John Currie, who are in the reformatory awaiting sentence on a similar charge, were brought out to give evidence against their supposed allies. Their testimony did not incriminate the trio, but rather showed that although Collins, Malloy and Banford had been present when the firing arrangements were made, they withdrew from the actual participation. The chief testimony against the lads was that of William Betts, of the Betts Detective Agency, who alleged certain admissions by the boys, but Mr. R. O. McMurtry, for the defence, argued that the boys had not been duly warned before making any statement.

Bail was refused when asked for in Banford’s case, the Judge ordering that the boys be sent to the reformatory until Tuesday next, on which date the two lads, Mitcchell and Currie, will come up for sentence. It was, said Judge Lanctot, a serious case, and the boys knew perfectly well what they were doing. --- MUST WEAR COURT DRESS. Respect to the court must be not only in attitude but in garb; so ruled Mr. Recorder Weir yesterday when two men, J. Bunnin and K. Lucas, were charged with violating traffic laws. The men appeared clad in blue overalls and with their hatbands well garnished with cigarette specimens of art. Ascertaining that these men had been out on bail, and that, therefore, they had chosen to appear in this way, the Recorder remanded the case for a day and informed them that they must reappear decently dressed. A friendly constable came to their aid, however, and in a few minutes they stepped into the court in normal coats and paid their small fine on the spot. --- TOO MANY BOY CARTERS. While hackmen must be over 18 years of age, a carter, said Mr. Recorder Weir yesterday, is not affected by this by-law. The result is that boys between ten and fifteen years drive vehicles through the city, and recently, added the Recorder, there had been brought before him quite a number of youths charged with infractions of traffic by-laws. Such boys not only were dangerous to citizens through their inexperience, but were in a school which was improper for a boy, as many carters were not fit associates for youth lads. --- THESE GAMBLERS LOST. Forty dollars and costs was the sentence of Judge Choquet upon the two men, Omer Dufresne and Damase Daigneault, who pleaded guilty in the Court of Sessions yesterday to a charge of keeping a common gambling house on East Notre Dame street, opposite Dominion Park. At first the men had pleaded not guilty in the lower court, but when they appeared before Judge Lanctot yesterday they changed their minds and revised their plea. Thereupon they were sent up to the Court of Sessions for sentence with the result mentioned. --- READY FOR NEXT TERM. Eli Aubin, alias Eli Robillard, who was arrested in Ottawa last Saturday on charge of carrying a concealed weapons, is wanted here to answer to charges of burglary and forgery. Aubin is only 21 years of age, but Detective-Sergeant Charpentier, who went up to Ottawa to bring him back here, said yesterday he was one of the most daring young fellows the police have had to deal with. Four years ago he was sentenced to five years in the penitentiary for burglary, but after having served a couple of years was allowed out on ticket-of-leave.

#montreal#newsies#arson#youth in history#history of canadian youth#news boys#youth in the toils#incendiarism#boy criminals#reformatory#shawbridge reform school#l’école de Réforme de Shawbridge#court attire#police court#carters#sentenced to prison#parole#parole violator#newsboys#Montreal Newsboys Protective Association#crime and punishment#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada

4 notes

·

View notes