#sexypink/Jamaican painters

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Back Room Bertha 2008 10 x 10 inches Oil on linen

………………………………………

Sexypink - A gem of an article on an exceptional body of work by Jamaican Artist Roberta Stoddart.

#sexypink/Roberta Stoddart#sexypink/Jamaican painters#sexypink/Jean Rhys/Wide Sargasso Sea#Dominican Writer Jean Rhys#Tumblr/Isis Semaj Hall#Tumblr/PreeLit#tumblr/ Roberta Stoddart#Bertha Room#Wife Sargasso Sea#PREE#writing on Art in the Caribbean

0 notes

Text

Sexypink - major browny points!

Sexypink/ Jamaican Oil Painter Alicia Brown.

Alicia Brown’s candid imagery is so very watchable and provocative. - Sexypink

#sexypink/ Jamaican Artist#sexypink/ Alicia Brown#oil painter#tumblr/Alicia Brown#Jamaican#realism#painting

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sexypink - Jamaican Painter Phillip Thomas paintings are majestic in both theme and technical skill. He takes you into unexpected places and you willingly go along for the ride because he leaves enough breadcrumbs to wet the appetite.

Sexypink - Phillip Thomas - The Bullfight - writing on this body of work by the Painter himself:-

Sexypink - Phillip Thomas - Donkey she dih werl nuh level

Sexypink - Phillip Thomas - detail

#sexypink/Phillip Thomas#sexypink/Jamaican Artists#sexypink/Jamaican Painting#tumblr/ Jamaican Art#Phillip Thomas#tumblr/Jamaican Painter#collage#painting

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sexypink - Mr Nattoo takes his work into the realm of textiles and embroidery. Let us enjoy the details.

Sexypink - Richard Nattoo - The Magician and the Red Moon - textile

Sexypink - read an interview on his practice here-: https://www.exhibitioncrave.com/writings/interview-with-visual-artist-richard-nattoo

Sexypink - Jamaican Artist Richard Nattoo

#sexypink/Jamaican Artists#sexypink/ Richard Nattoo#sexypink/watercolor painting#sexypink/textile art#tumblr/Richard Nattoo#tumblr/Jamaican Painter#Richard Nattoo#Jamaican#jamaican artist#textile art

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sexypink - the most striking thing about the paintings of Jamaican Artist Richard Nattoo is his restrained color palette and themes taking place at night. There is an instant attachment to wanting to understand the meaning behind the arrested individuals in twilight. Their blue skin speak of the ambiguity and mystery bound up with night. His translucent paint echo the memory of the symbolism of the color blue. Consider Oshun and Shiva, religion, superstition all bound together in our Caribbean displaced space.

Sexypink - Jamaican Artist Richard Nattoo - The Wanderer - watercolor, pen and ink using water from the Rio Grande River, Jamaica and Adom Waterfall, Ghana canvas

55 x 40 inches

Sexypink - Moonlight Meditations of Mama Nanny - Richard Nattoo

Sexypink - I see - Richard Nattoo - (2023) watercolor, pen and ink using water from the Rio Grande River - 60 x 51 inches

Sexypink - Island - Richard Nattoo - watercolor, pen and ink using water from the Rio Grande River Jamaica and Adom Waterfall, Ghana on canvas

200 x 200 cm

Sexypink - Jamaican Artist Richard Nattoo

Sexypink - https://www.instagram.com/reel/CwXr5OpIIVF/?igsh=MXJpN2dvejBicjV6Mw==

instagram

Sexypink - to see more -: richardnattoo.com

#sexypink/Richard Nattoo#sexypink/Jamaican Painter#sexypink / Watercolor and mixed media#tumblr/ storytelling#tumblr/ Richard Nattoo#Jamaican Painter#Painter#Instagram

1 note

·

View note

Text

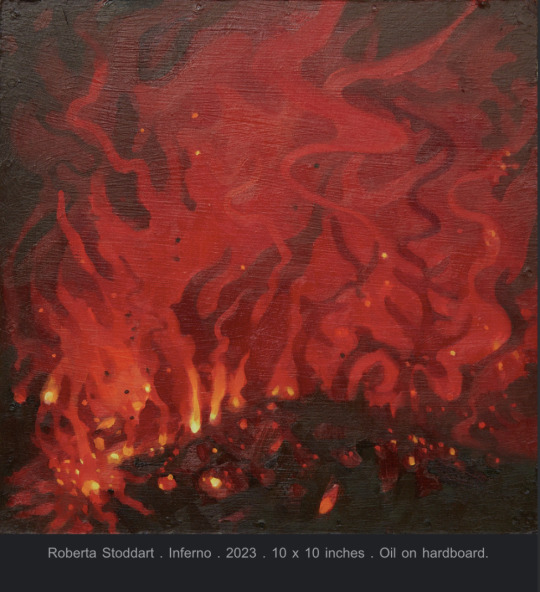

Sexypink - the indomitable Roberta Stoddart. Art is in her name.

#sexypink/ Roberta Stoddart#sexypink/ Jamaican Painter#sexypink/ Light my Fire#tumblr/Light my Fire#tumblr/ Y Gallery#painting#Y Gallery#Roberta Stoddart

1 note

·

View note

Link

#weekend#Sexypink/Judy Ann MacMillan#Sexypink/Jamaican Artist#Sexypink/Jamaican Painter#Sexypink/from Hyperallergic#Hyperallergic.com#Edward Lucie-Smith#Beattie Books#Kingston#painting#Jamaican Painter#nostalgia#National Gallery of Art

1 note

·

View note

Link

~Sexypink~ Jamaican Painter Alexander Cooper passed away on March.

#Sexypink/Joshua Alexander Cooper#Sexypink/Jamaican painter#Sexypink/Edna Manley College of the Visual and Performing Arts)#Joshua Alexander Cooper#Jamaica National Fine Arts Competition#Jamaican Art history#Jamaican Art

0 notes

Link

~Sexypink~ Jamaica losesan important collectors. Rest in Peace.

#Sexypink/Wallace Campbell#Sexypink/Bereavement#Sexypink/Jamaican Art#Jamaican#bereavement#Wallace Campbell#Painter#painting#patron#collector

0 notes

Photo

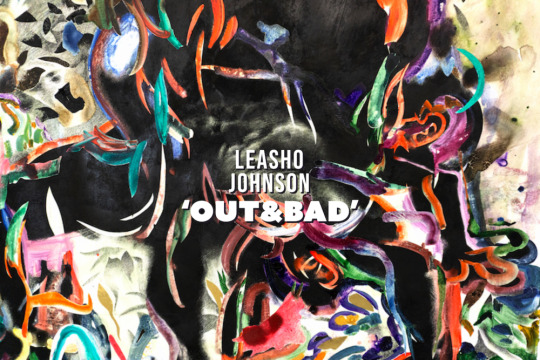

~Sexypink~ Leasho Johnson’s latest show! I can’t wait.

.................................

EXHIBITION STATEMENT

The title Out & Bad of the second solo show by Leasho Johnson at FLXST Contemporary comes from an expression popularized at the beginning of the new millennium by Dancehall DJs, as captured by the quotation above by scholar Nadia Ellis. Moreover, the Jamaican contemporary painter imbues the title of the show with significance as “queer black artist located on the outside looking in.” Leasho works on the periphery, which affords him the freedom to play with stereotypes and to create critical narratives about the borderline that separates the seen and the unseen. The artist is preoccupied with these contradictions, as they inspire, for him, the creation of spaces for worldmaking and knowledge production. While they enable Leasho to produce artwork that connects him to lived realities, they also allow the artist the opportunities to exorcise the ghosts embedded within the contradictions.

Articulating cultural codes of expression like fashion or style in Dancehall is, in my opinion, is quite easy. On the other hand, the challenge emerges when delving into Dancehall’s psychology, and its influences on the interiorities of its participants, and in Dancehall’s strong ties to the postcolonial state. I am interested in the fine lines between cultural expression, codes of conduct, and the psychology that binds them together. I am interested in what can’t be readily seen but nonetheless happens behind the eyes. Dancehall is a genre of music and culture that is in constant flux. The consistency of abject lives shows how much of it is driven by violence, sex, politics, history, and the many perceived stigmas and problems associated with black bodies. The core of my practice stems from my personal experiences with the Dancehall culture of Jamaica, a culture that I have loved and hated, embraced and feared. It continues to inform who I am. I understand my relationship to it as a queer experience that I willingly embrace through my imagination and my abstractions on canvas.

The centerpiece for the show The power & the glory (2021) takes from the artist’s interest in the intersections of fugitivity and blackness. Black gay love is greatly documented as a contemporary identity formation, yet unstudied or undocumented as lived experiences that existed on slave ships.* Leasho has been “frantically redrawing historical images and using them as street paper paste-ups, as means of historical critique and as reflections on the contemporary moment.” The artist as a historical documenter is seen in Leasho’s earlier works where he has repurposed Joseph Bartholomew Kidd’s (1808–1889) landscapes, John James Audubon’s iconic paintings of birds, Isaac Mendes Belisario’s street studies, and even the photographic portraits of Duperly and Son’s Daguerreotypes. In these works, Leasho attempt to reconnect himself and his art to historical moments by redrawing and reinterpreting these stylized “facts,” as most, if not all, do not depict black queer love—much less their humanity.

From its inception, The power & the glory continues on the trajectory of my previous work through my search for black queer love. In addition, I created another wall piece aimed to disrupt another depiction of “faux historic” imagery, that of the photograph L’Afrique Brise Ses Chaînes—Alexis & Jean Yves (1976) by Pierre & Gilles. Piere & Gilles are known for their hand-painted queer portraiture. In a poetic sense, this image fulfills one point of my search for historical documentation of same-sex love during the Trans-Atlantic slave trade era. In its fictionalization, it fulfills my hope of finding evidence but not without serious problems. The work perpetuates the power of the white gaze, objectification, colonial control, and ultimately the power over the black body. My paintings in the show reclaim the power of the black sitters by obstructing the viewers’ ability to recognize them—through their ambiguous appearances and interiorities.

The presentation of my Anansi painting series is a highly anticipated one for me. In this ongoing series, the characters have begun to collapse into vivid abstraction made by the conjunction of the hand-made medium, charcoal drawing, and subtractive stencil work. The concept of Anansi is an embodied metaphor for finding psychological space for black queer love: by embracing the mythology of the multi-legged creature’s anthropomorphism, its African origin, and also as a metaphysical marker for moments of queer intimacy. Viewed as an anthology, this exhibition features paintings Anansi #6, #7 and #8 (2020-2021) — my hope in creating this body of work is to shape a narrative around Dancehall, not just as a culture of “things that are not exactly as they seem,” but also as a site for invisible happenings.

The otherfication of the queer body in the black community, and in most cases through its invisibility, gives the artist room for re-imaginings that empowers through opacity.** Anansi, now as a frequent attendant of the Dancehall, is able to embed themselves in any role, male, female, or even as DJ by not being identifiable. Conceptually, Anansi is also not just an avatar representing survival within Dancehall culture but also represents a form of critique. Anansi describes unacquainted love between two male dancers, their anxieties, and their stolen moments in the “near-by-bushes.”

Out & Bad pulls together these concepts that I have been working on for the past two years, utilizing folklore and re-imaginings as a way of making the past and future, present to viewers. Out & Bad runs until May 23, 2021.

* Thomas A. Foster, Rethinking Rufus: Sexual Violations of Enslaved Men, (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 2019).

** Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. by Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor, Michigan, University Michigan Press, 1997).

#Sexypink/Leasho Johnson#Sexypink/latest shows/ Jamaican Artist#Sexypink/Out & Bad#Leasho Johnson#Out & Bad#FLSXT Contemporary#dancehall#sexuality#folklore#Anansi#LGBTQI#Artists of color

0 notes