#sexy northern irish protestants

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Gerry is literally such an interesting character though. I feel like because I joke about him all the time I don’t talk about how compelling I find him and also none of the rest of the fandom really delve into him either which is a shame because they made him such an interesting exploration of privilege, repression, immigrant identity, the Australian dream etc etc etc.

Like he’s kind of selfish, he buries his head in the sand and makes himself wilfully ignorant to bad things happening around him (from the bicentennial protests he’d definitely be extremely aware of to Dale’s mental breakdown in 2x05 to minimising the consequences of his own arrest), he’s so outwardly cool and collected that even the audience doesn’t realise how much he lives in denial.

And part of his continued denial is because he’s the rare immigrant who did actually achieve the Australian dream; he has fame and money, a loving family, a loyal fan base, a big house in Eaglemont. The cracks are beginning to show, the tabloids know about his sexuality and he knows he’s doomed if people find out. But Australia gave him everything he was promised, and compared to what Ireland looked like in the 80s, his new home gives him so much more freedom that he never had in a country that was still under the thrall of Catholic conservatism. And of course he’s not thinking about the fact he’s gotten everything he has because he’s white, and the right kind of white, and in fact, the right kind of Irish (ie not Northern. A Northern Irishman isn’t going to have the worst time in 80s Australia, but his identity is going to be far more politicised than someone from the Republic).

We talk about Dale and repression a lot. Because it’s really obvious. He’s repressing what are ultimately positive feelings - pleasure, passion, sexual desire. And we want him to experience queer joy the same way Gerry does. But Gerry is repressed as well. He’s repressing all of the negatives. He finds pain, controversy, anguish, etc, shameful and dirty the same way Dale does with desire. He doesn’t want to admit that the Australian dream is a lie, that he is extremely lucky and that all that he has could crumble at any moment.

There is so much that compels me about Gerry and makes him my favourite beyond “haha Funny Irished Man played by sexy actor” and I never talk about it because I don’t know how and no one else seems to fixate on him like I do. But like. Talk to me about Gerry please please PLEASE.

#flood warning#the newsreader#I’m actually putting this in the main tag because I put a lot of thought into wording this post#but gerry carroll I want to study you like a bug

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scannán Dé Máirt 25: Northern Ireland!

Hello my friends... I hope you had a suitably terrifying Halloween. This week, Toku Tuesday comes to you from the house of the delightful and sexy @baeddelfrom a paramilitary controlled estate outside Belfast... which means our theme is gonna be Northern Irish films! (Animation Night too... but more on that in a bit.)

Northern Ireland!

I won’t try to give you a detailed history of Northern Ireland in the next twenty minutes, covering the ~four hundred year gap after we talked about Cromwell on Animation Night 49. But to give a very brief story, Northern Ireland currently sits in an uneasy balance of power between the forces of the state and two paramilitary blocs ‘representing’ (holding coercive force over) the Protestant/Loyalist and Catholic/Nationalist populations, which in this context function as ethnicities as much or more than religions.

Where I’m writing this, for example, the wielders of ‘legitimate’ force are not the police but a Loyalist paramilitary whose murals are visible on houses as you enter the estate. The paramilitaries function in many ways like gangs (controlling the drug trade, extracting protection money) but also routinely make shows of force (yesterday I heard about armed UDF men a few estates over emptying a bus of people and torching it for unknown reasons, which was discussed rather like you would the weather) and will carry out spectacular punishments. To quote Jackie:

the loyalist paramilitaries went through a profound involution, becoming ethnoreligious dictatorships with exclusive police authority over the communities they claim to represent, battling among each other for control over housing estates. they possessed exclusive control over the black market, forced all businesses to pay them protection, and controlled most commercial services (taxi cabs, window cleaners, and so on). they exiled troublemakers, wounded lawbreakers, and murdered their opponents. your neighbours are taken away in the middle of the night and no one asks what happened. you wake up to breaking glass and gunshots, but no screams. then the paramilitaries appropriate the house of their victim and lease it out themselves. the IMC make an uncharacteristically wry remark that this is just “one amongst many ways in which paramilitaries continued to do what they had always done, namely doing violence to their own communities.” (IMC, pg. 14)

To try and paraphrase some of our conversations, this situation can be situated in the context of the lasting echo of the European Wars of Religion, the particular patterns of settlement in Northern Ireland (English Protestant landowners enjoying the policy of Protestant Ascendancy, a larger mostly Presbyterian settler population from many parts of Europe who became the current ‘Protestant’ side, and the native population who had largely been converted to Catholicism long before the English colonialism) in the long term; then, skimming over a lot, in the 20th century, it becomes a story of callous, half-hearted colonial withdrawal.

Following the First World War, in which Irish people were conscripted to fight for Britain, the ‘Irish Question’ as the British saw it (with different factions pushing for ‘Home Rule’ which devolved certain parts of power to two parts of Ireland, and for appeasement while keeping power in Britain) was largely settled by a series of wars which established the Irish Free State as an independent ‘Dominion’ of the British Empire. But meanwhile, Northern Ireland remained under control of Britain, which of course became increasingly contentious in the 60s. So why didn’t Britain give up NI as well?

In Britain’s Long War, a historical survey of British strategy in Northern Ireland, Peter R. Neumann rejects arguments that the British governments felt obliged to rule Northern Ireland for strategic reasons, or because they feared it would become a Cuba-like source of revolution, or that they saw it as some kind of integral part of British culture, with the government tending instead to view both the Protestants and Catholics alike with disdain. Instead, he writes, the combination of fear of genocide breaking out and its immediate proximity led the British gov to stay in essentially on the basis of trying to cause as little trouble as possible for themselves, knowing that events in NI would be heavily watched and televised:

[In the 1960s as the Troubles broke out] The principal aim of the British government was, as Home Secretary James Callaghan put it, not ‘to get sucked into the Irish bog’.[60]

Yet, all the governments during the 1969–98 period eventually arrived at the same conclusion: that using the constitutional instrument in order to pursue a policy of Irish unity would lead to sectarian strife and civil war, and that the consequences of ‘walking out’ were ‘to leave the Irish to murder one another’.[22] It is not entirely clear what mechanics were anticipated in that case, but London appeared to assume that the withdrawal of British troops would be followed by a Protestant genocide of the Catholic minority, thus provoking a military intervention of the Republic of Ireland.

This, however, was not a sufficient explanation in itself. After all, British withdrawal from India, Palestine and Cyprus had equally led to civil strife, and London had stuck to its original decision nonetheless. The difference between the former colonies and Northern Ireland was its closeness to Great Britain, and Westminster’s constant awareness of the province’s proximity resulted in a strengthened sense of responsibility.

This leads, in Neumann’s thinking, to a rather paradoxical policy where the British government simultaneously couldn’t stand to leave Northern Ireland, and continuing to do violence there, but also wishing to have as little as possible to do with the place:

If closeness produced responsibility, it also served to guide London’s efforts to keep the province at arm’s length. A ‘responsible’ government would prevent the conflict from disrupting Westminster politics and from becoming a contentious issue in parliament; it would protect its (mainland) citizens from any conflict-related instability or violence; and it would attempt to limit the extent to which Northern Ireland made the government vulnerable in its dealings with other countries. In essence, a responsible government would try to contain the negative effects of the conflict to Northern Ireland. As a result, the proximity of the province and the sense of responsibility it had induced resulted in two – seemingly contradictory – lines of thinking: there was an incentive to distance Northern Ireland from Great Britain, yet at the same time there was a disincentive to bring this process to its apparently logical conclusion, that is, to withdraw from the province.

Which means the loyalist side are simultaneously committed by long tradition to their colonial patrons, and celebrate when the cops fight the IRA, they also must know that they’re being held at arms length, sometimes supported by and sometimes clashing with the police. The British government meanwhile answered to a population who paradoxically vacillated between wishing to leave Northern Ireland to its fate, and wishing to see reprisals when the IRA bombed somewhere in England.

So the British governments’ policies were very paradoxical and deluded: they wanted to stay in, but also do as little as possible; they wanted to minimise use of force, but also demonstrate ‘enough’ to supposedly reduce overall violence and appease those calling for them to be tough on the IRA; they wanted to maintain the narrative that they were upholding democracy against terrorism, by resorting to such means as detention without trial; and they also wanted to get their soldiers out and cede control to the Irish police, ignoring that they were recruiting essentially another Protestant coercive force to play their own supposedly mediating role; they wanted to bring ‘moderates’ of both sides together to negotiate peace in which they imagined they could play a neutral role.

The result has been a kind of perpetual frozen-in-amber conflict which has, after the official ceasefire in the 90s, “retreated into the politics of threat and coercion” (Neumann, Jackie likes this quote :p), in which the paramilitaries largely enact violence on their own territory and turn towards reactionary populism shit about ‘protection of identity’ (as a large billboard featuring two guys with AKs put it), even appropriating outright Nazi iconography in the case of one Loyalist paramilitary (not the one here), and occasionally stage highly theatrical skirmishes with the police; people continue to be killed, but the situation moves no closer to any particular side’s overall desired outcome.

Anyway, movies!

...but anyway we’re not here to talk about Northern Ireland in general right now (I just like to write shit), we’re here to talk about movies.

From a quick survey of the wiki, the vast majority of Northern Irish films concern the Troubles, typically either historical films about real events, or dramas about members of one or other paramilitaries hurting people or trying to get out or etc. (This category includes good old ‘wildly transmisogynist’ The Crying Game (1992)). Starting in the 2000s, with the Good Friday Agreement in place, things seemed to open up a bit more; you started getting films about dog racing (e.g. Man About Dog (2004) and The Mighty Celt (2005)), crime dramas, and even a couple of science fiction films.

Which, since this is ostensibly Toku Tuesday, is going to be our main subject tonight!

youtube

Our first movie is low budget sci-fi horror film Ghost Machine (2009), in which a couple of soldiers attempt to have some fun with a stolen VR training program in an abandoned prison, only to discover it’s haunted. This movie seems to have been seen by almost nobody; it has broadly middling-negative reviews on IMDb, but since most of the reviewers are, beyond dismissing it as boring, quibbling the film’s supposedly overly leftist political bent, the amount of gore/torture, or unoriginality - which mostly strike me as probably good things or irrelevant - I have relatively little idea whether this will be good or not by my tastes! Definitely worth taking a shot on.

The director, Chris Hartwill, has relatively few credits to his name: a couple of TV shows and a TV spot about driving without a seatbelt. I did find a brief interview segment with the screenwriter Sven Hughes, but it says very little substantial. So this is honestly a total roll of the dice.

youtube

Our second movie is a monster B-movie horror-comedy with a goofy premise: alien tentacle monsters are attacking an island off the coast of Ireland, but they can be defeated by high blood alcohol; thus it is incumbent on the protagonists to spend most of the movie drunk. This one generally seemed to be received fairly well by critics at the time, so we shall have to see whether the comedy strikes the right chord with us!

youtube

That’s all I have on sci-fi; my representative for “Films About The Troubles” while steering away from dramatisations of real events is going to be kinda arbitrarily the spy thriller Shadow Dancer (2012), which sees a woman recruited by an MI5 agent to become a mole in the IRA, only for both parties to realise too late that she’s been recruited as a patsy to protect her mother, who is also a mole for MI5.

Most of these not-directly-historical films, including this one, take one of two approaches: either they seem to take the IRA primarily in a narrative of ‘scary terrorists’, and sympathise with agents of the British state, or they are about someone ‘caught between both sides of the troubles’. This is perhaps because the vast majority of these movies seem to be BBC funded and thus inclined towards London’s view; perhaps more generally filmmakers don’t want to be seen to be taking sides or inflaming matters.

So in this case, I suspect it’s quite dramatised and probably won’t tell much about what it’s actually like to be a paramilitary member, but it seems to have been very well received at the film festivals when it landed, so I think it is probably worth a shot.

I’ve taken way longer on my writeup than I planned, but luckily for us my sleep schedule is completely gone; we’ll begin Toku Tuesday Scannán Dé Máirt in as long as it takes for me to eat some soup, so probably about twenty minutes, at https://www.twitch.tv/canmom !

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

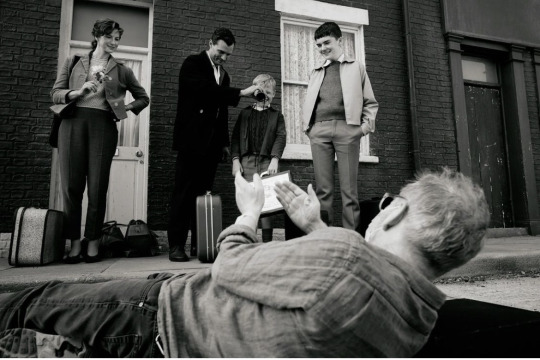

Kenneth Branagh on the set of Belfast. Photo: Rob Youngson/B) 2021 Focus Features, LLC.

With the idea of the future losing much of its luster, many of us spent the COVID era thinking about the past. But few took it as far as Kenneth Branagh, who used his sudden downtime to write and direct a black-and-white autobiographical drama. Branagh’s Belfast follows a cherubic 9-year-old named Buddy (Jude Hill) whose childhood is upended by the coming of the Troubles. Despite the creeping sectarian violence, the film is grounded in Branagh’s youthful memories of the city: neighborhood banter, schoolyard crushes, enough Van Morrison songs to soundtrack an anti-lockdown protest. “There is something genuinely bold in giving a movie about Belfast in 1969 the warm glow of the everyday,” wrote our critic Bilge Ebiri. “It reminds us that life goes on.”

Belfast premiered to an enthusiastic reception at the Telluride Film Festival and shortly thereafter won the People’s Choice Award at TIFF, catapulting the film into the Oscar conversation. That was exciting news not just for Branagh but also for my father’s family, a collection of siblings around the director’s age who grew up in Derry and were thrilled that Northern Ireland was getting the Hollywood spotlight. As Branagh made the awards-season rounds, I spoke to him on Zoom about fry-ups, his artistic evolution, and — as my aunts and uncles begged me to — how he lost his Belfast accent.

It might be different in the U.K., but in terms of projects that make it to the States, Belfast is the rare movie about the Northern Irish Protestant community. I have my own theories about why that is, but I’m curious about why you think that is.

What are your theories just by the by?

There’s two parts. The first is that, in terms of things made for the U.S., most Irish Americans are Catholic, and so stories from the Catholic perspective are naturally more appealing to the American audience. And the second — without getting into specific choices made by specific Irish Republicans — is that in general, the Catholic community was more of an underdog than the Protestant community. And thus in those stories, the narrative is a little easier to understand. The moral stakes are more legible.

A perfectly rational theory on both counts. I also think that there is an element of the Northern personality that is expressed, semi-comically in our film, through the preacher, who sets up this rather austere, severe view of life. Protestant ministers really were so fire and brimstone–y that there’s almost an innate suspicion in some Protestant minds of telling stories — that it’s rather indulgent, a bit of frippery. Whereas our job is to joylessly move through life getting ready to hopefully make our way out of purgatory.

Was your preacher in real life that kind of fire-and-brimstone Paisleyite guy?

One-hundred percent. My parents got out of churchgoing as soon as they possibly could, but they were stuck into the ritual of it, so we were sent basically to put money onto the plate. It was very theatrical, very stern. It was always presented in this visceral way, always around the word sulfur. You were going to burn — simple as that.

This is probably not the first time you’ve heard this, but the parents in this film are among the most attractive parents ever put onscreen. When you were a child, did you idealize your parents, turn them into these glamorous, larger-than-life figures?

What they had was this incredible fizz, this passion between them. Since the film was made, I’ve come across a few photos of them in the late ’60s. My mother had a big pair of Gina Lollobrigida glasses — very sort of sexy trexy and glamorous. They didn’t have the money, but she definitely had an innate sense of style. And he was very proud of her sassiness. She was one of 11. Her mother died giving birth to her. To survive in that family, you had to shove, fight, and scream, so she was a firebrand. And, of course, those qualities in people often are very attractive. And Jamie’s dry sense of humor was bang in the center of my own father’s. But ultimately, even I didn’t know quite how photographically zingy the pair of them would be. My wife saw the film and said, “Jesus. Please photograph me like that.”

There are some scenes in the film where you shoot Jamie Dornan like he’s a Socialist Realist hero, this titanic figure who’s twenty feet tall.

In those scenes, I felt like I was writing a western. A picture that I love is Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven. You’ll recall from the poster, it’s shot from behind him, low, and his hands are on a gun. It was the idea of the kid seeing his dad as a mountain. That’s what he needed to see. He also needed to see a big Belfast sky as well. And then you’ve got Billy Clanton [the film’s Protestant militant] who is a kind of tinpot Hitler sneaking into a power vacuum, becoming Jack Palance from Shane: the raven-haired, implacable villain. Somehow we started to put those images together.

I read your book Beginning and was struck by how many scenes in the film come straight from those memories. But one thing that was different was the portrayal of school. You write about a very Dickensian, very cruel experience, which lines up with things my dad has told me. But the school in this movie is a much more positive environment.

What I wanted to retain about the experience of the school was the obsession with the girl, trying to get further up the class. At one stage, it was in the script. For instance, I got the cane from a headmaster for walking across some flower beds one time. But it just felt like too much. It became a different, almost documentary look. What was key to Buddy is that we all put up with this. It wasn’t like I was coming home going, “I can’t believe I got the cane.” My parents would’ve said, “Are you broken? No? All right, then get on with it.”

Did you ever catch up with the girl in real life?

I never did. I always felt that I just wasn’t good enough for her. And I was absolutely convinced that she basically liked people who could do maths better, and I never could.

Do you think if she saw this movie, she’d recognize herself?

I sometimes wonder. I would like to think. Obviously, the names have been changed to protect the innocent. God willing, they’re all still alive and healthy. But I don’t know. There may be some of this she may not even have understood was coming in such a heartfelt way from me. So she may not remember me.

Judi Dench, Jude Hill, and Ciarán Hinds in Belfast. Photo: Rob Youngson/Focus Features

I asked my aunts and uncles what kind of questions I should ask you, and completely independently, they all wanted to know how and when you lost your Belfast accent.

It was in the two or three years after I came across. We left when I was 9, May of 1970. And by the time I left secondary school in the summer of ’72, it was probably gone. I think it was to do with wanting to disappear. I wanted to just fit in.

It’s funny: When we came across, there was no desire on my parents’ part to keep up with the Joneses. They had no interest in additional social status or anything. They came over, and they did the things that they did back home. My dad played the horses. My mother played bingo. But we were thrown into a very different social class. From working class, we went to lower middle class. And it was a world that didn’t really understand our world.

As we all became a bit more insular, [my accent] kind of rubbed off. There were a couple of years of not even knowing it was happening, then feeling a bit bad about it. So for a while, I was English in school and Irish at home. And then it started happening at home. My parents didn’t comment about it. I think they felt it was natural enough.

When you went back for the Billy plays [a trio of BBC dramas from the early ’80s about a working-class Belfast family that served as Branagh’s first big break], did you find yourself putting it back on again?

No, I didn’t, but it’s interesting. I went back with a friend of mine, the guy who plays the best friend — an excellent actor who’s a policeman now, called Colum Convey. When we got on the plane on the way to Belfast on the Sunday night before the first day of rehearsals, Colum said to me [in a Cockney accent], “Now, listen, Ken. From tomorrow, I’m going to be completely Belfast. All right?” And that’s what he did. The next day, it was like meeting a completely different guy. Whereas I didn’t feel comfortable with that. I had the mickey taken out of me left, right, and center, but I would do the part and then I would step back into the way I sounded. I’ve never been good at doing that totally immersive thing.

I first became aware of you in the ’90s. In the version of you that made its way over to American audiences, you were presented as sort of England incarnate. It wasn’t until later that I learned of your Northern Irish heritage. Were you cognizant of that disparity? And did that ever give you any sort of identity crisis?

I don’t know about an identity crisis, but I was aware of that disparity. This film, in a way, goes back to understanding what infused my storytelling DNA. It’s very much forged by my background. You can tell from this film: How far away could [working-class Belfast] be from doing Shakespeare in English accents? But my drive to do it was partly to say to my parents, “Look, we can enjoy this as well.” You don’t have to have been to Oxford, Cambridge, Yale, Harvard, Princeton. If it speaks to you, it speaks to you.

And yet I think there was an assumption that I was part of what you might call the English elite or that I would have come from one of those places. I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with that; I’m just saying there were perhaps some assumptions made. I don’t know about identity crises, but all I knew was, God, I couldn’t be what people thought of me: a spoiled posh boy or something. It’s not important enough to try to correct people: “You realize I’ve got proper working-class Belfast credentials here, mate.” But this [film] was a chance to allow the truth that the mix of whatever spawned me as an artist was happening back then.

In the book, you mention that the phenomenon you call “Branagh-bashing” began fairly early on. What do you think it was that made you such an easy target?

I think it was as simple as overexposure in the media. I was absolutely unaware, though people might say, “How could you not be?” We ran a theater company that became a film company, and in doing what I felt was my duty to everybody else involved, I basically spoke to whoever I was pointed at to bang the drum for it. There comes a point where you go, Enough already. I was 27 when I directed Henry V. I was 29 when I got double-nominated as an actor and director in the Academy. For some people, that is incredibly annoying, and they think, Fuck him. As if I was wandering around talking about the cleverness of me when I can assure you I wasn’t. Although, no doubt, I’m sure I was capable of being cocky and arrogant and stupid.

In those early days you were putting yourself on a very ragged schedule: During breaks for one project, you’re writing something, directing something else, rehearsing yet another thing. How long were you able to keep up that pace?

I always had some sense of seizing the day, that you might not have the opportunity again. I had an enormous amount of joy in the work, and I think that always drove me. That kind of crazy schedulizing went through about 2000, when we made Love’s Labour’s Lost. I remember waking up at the Essex House hotel, Central Park South in New York, on the morning when the New York Times review, not good, came out for that film. And it was not alone. I remember thinking, Oh, fuck. That sort of took the wind out of my sails. It wasn’t that I couldn’t do it, but I’d just been in the boxing ring for quite a long time, and I’d taken quite a few punches. I didn’t feel burnt-out, but I did feel bashed-up. Didn’t consider it catastrophic, but I knew I had to ease up a bit.

Do you still pay attention to reviews, or have you learned to cut yourself off?

I have learned that, but you can’t help but pick up on it. You’ll get that response: “Oh God, I’m so cross with that writer X. Don’t you listen to a word of it.” I don’t know what you’re talking about, but now I know somebody said something appalling. You can’t be too insulated — otherwise, you won’t get feedback. But plugging into the sort of vast plethora of how the thing is spoken about, I resist to the maximum. And to be honest, I do respect the contrary opinion. I’m at a point in my life where I understand you can’t please all the people all the time, and sometimes the ones you don’t please are much more interesting.

Do you have a personal contrary opinion?

I believe that Tottenham Hotspur will win the Premiership this year. I would suggest that is contrary to most people’s opinions.

My uncle Thomas is also a Spurs fan. Why are there so many of you in Belfast?

Danny Blanchflower. He was a Northern Irishman who won the Footballer of the Year title in ’57 and ’61. In ’61, he captained the Tottenham Hotspur double-winning side. They’ve never done it since. He also captained the Northern Irish team to the last eight of the 1958 World Cup. He was the one guy in the history of the program This Is Your Life — where a celebrity is ambushed and all the people in their life come into the studio — who just refused to do it. That was how singular he was, Danny Blanchflower. There’s something about that character that is very Northern Irish. Some would call it belligerence; some would call it strong-minded and sort of inspiring. He had a strong position and held it even though it might be exceptional.

In early reviews, you were spoken of as an actor who also directed. At what point did you feel as if your filmmaking talent reached the level of your acting talent?

I didn’t think about my acting talent in any sort of particular high pitch or anything — simply that that’s what I did. I think it’s probably taken till now, to be honest, to begin to understand. This film is partly involved with that. I was surrounded by people who told stories all the time, told jokes, made stuff up. The telling of tales was something inbuilt. Sometimes you performed it, and sometimes you watched other people do it. But the idea that I’d ever do any of this [professionally] was so … I think of that little kid on the pavement reading a Thor comic. If you’d said, “Oh, by the way, 9-year-old, when you’re 50, you’ll be directing Thor, the fourth film in what will become the cinema-dominating universe of the 21st century,” I would’ve thought you’d come from Venus.

You lacked the context to know how a person would even get from there to here.

How do you make films? How do you tell stories? What is directing? What is acting? Work was, You’d be a plumber or a chippy; you worked in a shop; if you’re lucky, insurance company or whatever. Or you went in the army or British Rail. The other stuff wasn’t on our radar.

There’s been some discussion among critics about the wake scene at the end of the film with “Everlasting Love.” The first time I saw it, I just took it completely straight. But I’ve heard other people call it a dream sequence. Is it meant to be ambiguous, or is one of us completely wrong?

I don’t mind if it seems ambiguous. But the truth I was trying to get from it was that the moment after the burial had to be an expression of the opposite of what people had just felt: the dark, joyless, awful grief of losing someone so loved. These were wild nights in the sense of they were frenzied, they were passionate, and they were a release. People would try to make that moment bigger than their lives — a proper piece of closure that is a supernova for the end of this person’s life.

Whose idea was it for Jamie to sing? I’ve noticed he enjoys a musical number in many of his films.

He’s essentially singing alongside the recorded track there and then, but we recorded him afterward, and he has got a terrific voice. As you may know, he sang it live at the L.A. premiere. Ballsy thing to do, but he did a grand job.

Jamie is somebody who really goes for it, and he was ready to dance and sing. Also, it’s a great lyric for that moment in their relationship. What the film talks about is what Noël Coward famously wrote, rather patronizingly: “Extraordinary how potent cheap music is.” I would say that it’s a profound lyric even though it’s in a pop song. But that’s what we were: consumers of what others might call low culture.

You’ve written very movingly about the smells of Belfast. Is there a particular smell that brings you back to your youth?

Well, the sea you smell, or the loch, as it is. My mother used to eat cockles, and we would go to Donaghadee Beach to eat whelk. We’d get them off the rocks; you probably couldn’t do it now. But you get whelks, and you bring them back, and you boil them. Sometimes put vinegar on, sometimes put butter on. My mother used to have this deeply fishy smell.

The movie used to have a whole theme of dodgy food that was left out. The smell of tripe — Jesus Christ. Poached tripe in milk, you’d be tasting it for a month. And the other thing — not so bad but rough to look at — were pig’s trotters. Cooked for hours and hours. You’d try and find a piece of meat in there. It’s an incredible mystery to get a bit of protein out of a pig’s trotter. Fish and ham is what I smell.

There was a lot of family curiosity about food, particularly the ingredients that make a fry-up. They wanted to know if you preferred potato farls or soda bread.

Both. I had an uncle who used to make it this way: He would melt half a pound of white cap lard. Then he used to put the soda bread in, and he’d sort of boil it. And he would press down on the soda bread until it soaked it up. Then he put the potato farls in there, they’d swim around. All the pieces would soak up the fat. He’d take all the bread out, put aside. Then he would melt another half-pound of lard, into which he’d put sausages, black pudding, tomatoes, bacon, mushrooms. It was a beautiful thing to eat, but you really didn’t need to have another one for a decade.

Remember… I think of that little kid on the pavement reading a Thor comic. If you’d said, “Oh, by the way, 9-year-old, when you’re 50, you’ll be directing Thor, the fourth film in what will become the cinema-dominating universe of the 21st century,” I would’ve thought you’d come from Venus. — Sir Kenneth Branagh

#Tait rhymes with hat#Good times#BelfastMovie#Interview#Vulture#7 January 2022#Belfast#Worldwide 2022

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Belfast: Kenneth Branagh Remembers a Childhood That’s a Million Miles from Shakespeare

https://ift.tt/3cc9Qu2

When one thinks of films by Irish director, actor, and writer Kenneth Branagh, the first word that comes to mind is “elaborate.” His directing resume alone consists of five Shakespeare adaptations (including a full-length, four-hour Hamlet in which he also stars), one cosmic superhero movie at Marvel, a live-action version of a classic Disney fairy tale, and a star-studded adaptation of arguably the most famous mystery novel of the 20th century. Clearly, this is a storyteller who likes to go big.

Which is what makes his new film, Belfast, so surprising in so many ways. It’s the opposite of what we’ve come to expect from a Branagh joint. Yes, it’s a period piece, but it’s in black and white. Gone are the elaborate sets, like the throne room of Asgard from Thor or the castle in Cinderella, or the Gothic laboratory from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. The eye-popping costumes from any of those three films or the director’s entire Shakespeare oeuvre are nowhere to be found. Also missing: Branagh’s penchant for swooping camerawork and Dutch angles, as well as sometimes overwrought performances.

Having said all that, we like lots of Branagh films around here, and that includes the many he’s acted in as well as directed. But there’s no question that Belfast, a semi-autobiographical work based on Branagh’s childhood in the title city during the Troubles, is easily his most personal, emotional, and perhaps finest work as a filmmaker. It finds nostalgic joy in the center of a period remembered grimly by many in his hometown as Protestants and Catholics were pitted against each other over the autonomy of Northern Ireland for 30 years.

Belfast is loosely plotted and episodic, following nine-year-old Buddy (an excellent debut by Jude Hill) as he goes about his daily life in a small community tucked inside his beloved city. Buddy’s Ma (Caitriona Balfe) tends to him and his older brother Will (Lewis McAskie), while Pa (Jamie Dornan) spends a lot of time away, working in England. But his grandparents (Ciarán Hinds and Judi Dench) are around, and the rest of the neighborhood–an extended community/family in the best sense–looks after him and each other.

That is until the simmering tensions between Irish unionists (mostly Protestants who wanted Northern Ireland to remain a separate state that’s part of the UK) and nationalists (largely Catholics who want the North to become part of a united, independent Ireland) breaks out into all but open war in the streets, with riots, bombings, beatings, and the constant threat of more violence splitting Buddy’s neighborhood into two factions. In the aftermath, neighbors, friends, and even family members begin turning against each other.

The quasi-documentary style in which Branagh shoots all this makes it heartbreaking to watch. Just like so many of his films, Belfast is a period piece, but the cinematography and production design are more low-key and realistic than in his other, more florid films. The block on which Buddy lives feels real, from the narrow row houses to the side alleys to the wide storefront windows. Everyone knows each other, and there’s a sense of a real community, even as it’s torn apart by violence within and without that many of them don’t want to be involved in.

Read more

Movies

Kenneth Branagh is Still Proud of Directing Thor

By Don Kaye

Movies

Kenneth Branagh Describes His Death on the Nile as Dark and Sexy

By Kirsten Howard

There are moments of extreme happiness–as when Buddy watches his Pa sing with the house band to his Ma at a wedding late in the movie, their own marital troubles swept away by their continued love for each other–and extreme terror, as when Buddy is swept up by a mob and forced to participate in the looting of a supermarket. Over it all hangs the knowledge that somehow Buddy’s little Belfast neighborhood is changing forever, as residents are killed and families decide to leave, with his own Ma and Pa agonizing over whether to stay and risk their lives or leave for England and try to begin an entirely new life in a country that doesn’t exactly welcome them either.

This writer did not grow up in or near anything like the Troubles, nor did my family (a divorced single mother with two young children) have to uproot itself to another country. But when you’re seven years old, even moving from Brooklyn to Staten Island can feel immense. Being alone there for long stretches of time while your mother works part-time to scrape together whatever money she can, and not knowing if we’ll make the rent, can feel terrifying even without your old block going up in flames.

Branagh makes all of that relatable in Belfast, even for the many of us watching who did not experience the Troubles firsthand, and his cast also makes the relationships between Buddy and his family members equally full. Ma and Pa can somehow seem distant, with Pa gone for long periods of time and Ma often mentally not present as she tries to balance the budget and make up for the shortfalls that Pa has incurred with his occasional gambling. That makes, in many ways, the relationship between Buddy and his grandfather, “Pop,” perhaps the most key in the film.

Hinds and Dench are absolutely perfect in their roles, and one senses the entire history behind Granny and Pop even without it being explained or defined. He’s a bit of a rascal, perhaps even a ne’er-do-well, while she’s the practical, hard-headed one who keeps his feet on the ground. Yet their warmth and love for each other and their family shines through at every moment. Without his Pa around, Buddy naturally looks up to Pop as a father figure; I did the same with my maternal grandfather, who was something of a superhero to me. The vacuum caused by their inevitable absence–due to the necessity of younger families moving or the relentless onslaught of old age–is keen.

But Granny and Pop–and all “those who stayed,” to whom the film is partially dedicated–represent a Northern Ireland that perhaps lives now only in Branagh’s memory. He brackets his film with color images of Belfast today, a large, bustling metropolis quite different from the tiny, gray, cloistered little town in which the filmmaker grew up. Belfast is, as we suggest above, about a million miles away from the often entertainingly melodramatic and even operatic esthetic of so much of Branagh’s past work; but in terms of shared human experience and emotion, it’s right there next to every one of us, as close as the touch of a grandparent’s warm hand. It’s also, ultimately, just as impermanent.

Belfast is now playing in theaters in the U.S. It opens in the UK on Jan. 21, 2022.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

The post Belfast: Kenneth Branagh Remembers a Childhood That’s a Million Miles from Shakespeare appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/3FioFYF

0 notes

Photo

Gary Lightbody is the lead singer of Snow Patrol, and comes from the glamorous seaside resort of Bangor. His band have sold millions of records by peddling a sort of moody breathey soft rock thing. I know people roll their eyes up at Snow Patrol and say "oh Snow Patrol" but I like what they do and the lyrics about lying down and cars remind me of my own childhood in Northern Ireland. I won't say it's an exact representation, but they capture a certain something.

He has managed to get himself a nice jacket and a good haircut making him look like a tousled Mark Ronson.

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The inspiration for this site, Henry Joy McCracken not only had an excellent name, but ran a cotton factory before joining the United Irishmen insurrection, leading a failed rebellion and being executed by the English in Belfast in 1798. We like his soft gingery hair, sculptured cheekbones and little dimpled chin.

#sexy northern irish protestants#henry joy mcCracken#irish protestants#sexy protestants#northern ireland

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A LOL-alist mural

#sexy northern#sexy northern irish protestants#loyalist mural#protestant mural#northern ireland#northern ireland satire

0 notes