#saulteaux first nation

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Corrine Moosomin, 25

Last seen in Saulteaux First Nation, Saskatchewan in 1986.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grass Quilt, Wally Dion

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

diaspora is survival : let the dystopian morning light pour in

this is an edited version of an autobiographical essay i submitted for my pan-african geography class where the prompt was

"Using the excerpt from Stokely Carmichael’s Ready for the Revolution as a model, write a short autobiographical essay describing your own experience of “diaspora as survival.” How, in other words, did you end up here in Vancouver and at UBC? While you should describe as much as possible the migrations of your own family, you should also try to include references to those important historical markers of labor, history, race, colonialism, migration, and gender that are referenced by Carmichael." the purpose of me publishing this essay on tumblr is so i can cite it for another class, michael if ur reading this i hope u enjoy it !! i omitted some details i wasn't comfortable posting on the internet (aka not doxxing myself). also if the capitalization seems funky, it's intentional !!

I am what time, circumstance, history, have made of me, certainly, but I am, also, much more than that. So are we all.

[Notes of a Native Son – James Baldwin]

I’ve always been a bit of historian, how could I not when my own history, my own stories, have been hidden from me. To be Indigenous in a country that treats my people as a history, as no longer present, means being a historian of my own culture is a form of resistance. It doesn’t fit with the settler colonial canadian logic for my people to have a history or culture. Everyday I resist this occupation by remembering, by recreating, and continuing anishinaabek ways of living. And if Audre Lorde says, “the personal is political”, then much of what I write (both for academic purposes but also creative projects) will involve the politics of being a disabled Afro-Indigenous queer/two-spirit person living in an occupied state. Simply put, I write as a Nakawe, a citizen of Tootinaowaziibeeng, in Musqueam territory. I write from the belly of the beast and it can hard to avoid the drops of acid on these pages.

How do you know your history? I’m not saying “ask your mom to cite her sources” but how do you know if what you’ve been told about yourself, your family, community, etc is true? I don’t believe one’s truth and what is fact are the same, at least I haven’t lived a life like that. Thus I’ll start where life starts, with the one who brought me into this world. I was born in oskana kâ-asastêki to my two adoptive parents and my biological mother tracy-lynn. I was adopted at birth, many who aren't familiar with the foster care system (the modern way canada monitors Indigenous children’s whereabouts, since the final residential school closed in 1996) would think that being adopted at birth was a good thing, I don't know if it was. You're likely wondering where my biological dad is… well that makes two of us. During conversations with her social worker she admitted to not knowing the father and regularly having casual sex with men of different ethnic origins, naming white, Indigenous, Black, and Filipino. Thus my adoptive parents (Tracey and Arlon), assumed I was Filipino based on my looks. Although strangers did occasionally throw Black microaggressions towards me, older white women wanted to touch my black curls and I was a girl who wanted to be ‘polite’.

For the first 18 years of my life, it was my truth that I was Filipino. The guilt of my lack of connection from my Filipino friends eventually brought me to study the language as a teenager. Wanting to know what region of the Philippines my father was from lead me to doing a DNA test around age 18. Discovering the truth, for a short period of time, resulted in a what felt like a cultural crisis. I finally felt comfortable in one of my ethnic backgrounds (comfortable enough to get a tattoo of the Philippines flag within a knife, image above) so realizing the rarity of situations like this and not being able to find help online terrified me. After learning basic Tagalog, growing up with Filipino friends, and even embarking on a double major of History and Asian Studies, I had found myself in a very strange circumstance. You can find thousands of articles giving advice on how to come out as gay or transgender (as I had done so at 11 and 12 myself), but nobody really comes out as African. Honestly, I was scared that people would think of me as a liar or fraud. Like the pretendian equivalent of being Black. If the truth came to light, people would think I was intentionally lying about my race. At the same time, I was scared that if I said I was Black, but provided no proof, I was just some annoying leftist trying to claim a marginalized identity. It felt like being called to fight in a war where I'd lose on either front.

As strange as it sounds, I can’t imagine my life without my queerness. Growing up with two older siblings that came out as queer before me allowed 11 year old me to develop language to understand myself and others. If I weren’t queer, I don’t know if I would’ve been introduced to philosophies of identity and history. Gaining a sense of self, a sense of pride in who I am and the communities I’m a part of, was integral to me discovering feminism at a young age (roughly age 13), leading me to learn from Black and Indigenous feminists/communists, many of whom I cite today in teacher education. The most important life lesson being queer has given me is that I don’t need to “know” myself, know what exact labels and identities suit me at any given moment, I just need to live. For example, I don’t inject testosterone because I feel at my core I’m a man (I don’t) or because I feel a need to prove my masculinity in a biological way (I don’t), I do it because I like the way it makes my body look. In a very Gen Z way, I decided to fuck around and find out. Thus when I had my cultural identity crisis, I realized I could just identify as mixed Black/Ethiopian/African. In the same way there’s no “true trans” person, there’s was no way for me to “truly” be African. I just am.

As mentioned, I learnt about social justice issues and movements relatively early which was integral to my own identity development. Through learning from revolutionaries like Kwame Ture who stated “We're Africans in America, struggling against American capitalism. We're not Americans” and “a fight for power is a fight for land. [...] Our land is Africa. America's not our land, it belongs to the American Indians and we have a right to stand and take a moral struggle with them.” I felt empowered to describe myself as Afro-Indigenous, to bring my two sides together as one whole. Diaspora is survival can mean a lot of things at different times & places but here, it meant a member of the diaspora empowered another diaspora to take up the family name of African, within my mixed background. The name survived its travels. This is my favourite term for a few important reasons. Firstly, I’m acknowledging the lands I’m from. Both the ties I have to Africa as a diaspora and Indigenous reflecting my Turtle Island upbringing. Secondly, I’m not identifying with a colonial state as terms like Indigenous Canadian or Black Canadian would suggest. Lastly, I’m not playing into the settler idea of blood quantum. A soul cannot be divided into percentages.

It feels wrong, embarrassing even, to say I envy the classmates of mine who have the privilege of being one call or text away from a family member that can answer simple questions. I only know what someone, I assume a social worker, felt was worthy of documenting. I didn’t learn that my maternal grandmother’s brother roger was forced into multiple residential schools from tracy-lynn or her mother rita, I learnt from a fucking hydro company. How colonial dystopian is that? Hydro Manitoba did a study of the land they intended to put pipelines through, consulting the nation which neighbours my own. My nation is Tootinaowaziibeeng First Nation, physically within Treaty 2 territory but a signatory of Treaty 4. I’ve lived most of my life on Treaty 4 land, i.e. the land stolen from the Métis (michif), Cree (néhiyaw), and Ojibway (anishinaabe). My adoptive dad Arlon is a descendant of the first British & French settlers in the region and he didn’t know which Indigenous peoples lived on the land that makes up our family farm-turned-acreage until I told him. To him, the land was always in the family and was empty before, owned by the canadian government that gave it to his family. As a socially anxious young adult he was set up on a dinner date with my adoptive mom, Tracey. She was also from a white farming family, her childhood home being just 2 km down the road from where mine still sits today. Growing up she embraced the cuisine of her German ancestry, that was all her mother taught her. If I remember correctly, she’s mostly German, but had Jewish family survive the Holocaust, becoming refugees to Canada after leaving the Netherlands. I’m unsure if they were Dutch Jewish, I never asked. Despite having 3 known sides of family, I’ve always been distanced from them in some way. When I was young my mom told me the reason we didn’t spend time with distant family was because they were “mean” to her. As a teenager I learnt “mean” actually meant racist, they were upset with her for adopting an “Indian” baby.

Like Toni Morrison, much of my own literary (and musical) background comes from autobiographies. Now that I think about it, I’m surrounded by autobiographical creations. I can prove this on the spot by looking down at my phone next to me, Spotify open, playing Boujee Natives by Snotty Nose Rez Kids, a hiphop duo from Haisla First Nation. That song is on my ndn rap playlist, below it is my hiphop for sexy ppl only playlist which contains only Black/African rappers. I hit shuffle on the playlist and Malcolm Garvey Huey by Dead Prez comes on, ironic as I get to read works by/about these exact historical figures for this geography class. If I look into my backpack next to me I’ll find Dancing On Our Turtle’s Back by Leanne Betasamosake Simpson (Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg) and Creeland by Dallas Hunt (Swan River First Nation), both autobiographical works to an extent. That’s just my immediate surroundings here at a cafe near my house, I typically exist near a shelf of autobiographies at my two library jobs, as well as at home in East Van.

Where would I go? If I wrote an autobiography what section would they put me in? Would it still be autobiography if so much of my family knowledge comes from government documents like an adoption act or residential school records? Would my Indigeneity render it a historical work? If I have to rely on historical evidence to make a guess, does that make my life a fiction? Assuming an Indigenous category exists, who makes the decision on whether I’m too Black to belong? Perhaps I’ll write a biomythography like Audre Lorde. The sisters have it figured out this time, I know where’d I go.

If past you were to meet future me, Would you be holding me here and now?

[Historians – Lucy Dacus]

References :

Afromarxist, “What's in a Name? ft. Kwame Ture (1989)” YouTube, video publication date 27 October 2019, https://youtu.be/OGcl359SMxE?si=T_bs5PKLBZuUYwZ0

Baldwin, James. Notes of a Native Son. Boston: Beacon Press, 1955.

Chakasim, Neegahnii Madeline. “Pretendians and their Impacts on Indigenous Communities.” The Indigenous Foundation, May 10 2022. https://www.theindigenousfoundation.org/articles/pretendians-and-their-impacts-on-indigenous-communities

HTFC Planning & Design & Manitoba Hydro. “See what the land gave us” Waywayseecappo First Nation Traditional Knowledge Study For the Birtle Transmission Line. December 2017. https://www.hydro.mb.ca/docs/projects/birtle/appendix_c_waywayseecappo_tk_study_final_report.pdf

Lucy Dacus. Historians. Jacob Blizard and Collin Pastore. March 2, 2018. Matador Records, digital streaming.

Books / music mentioned

dead prez. Malcolm Garvey Huey. June 22 2010. Boss Up Inc., digital streaming.

Hunt, Dallas. Creeland. Gibsons: Nightwood Editions, 2021.

*Maynard, Robyn. Policing Black Lives: State Violence in Canada from Slavery to the Present. Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing, 2017.

Lorde, Audre. Zami: A New Spelling of My Name. New York: Crossing Press, 1982.

Phoebe Bridgers. ICU. Phoebe Bridgers, Marshall Vore, & Nicholas White. June 18, 2020. Dead Oceans, digital streaming.

Snotty Nose Rez Kids. Boujee Natives. May 10 2019. Independent, digital streaming.

Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake. Dancing on Our Turtle’s Back: Stories of Nishnaabeg Re-Creation, Resurgence, and a New Emergence. Winnipeg: Arbeiter Ring Publishing, 2011.

*Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake. As We Have Always Done. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

sources with * were in the original essay but omitted from this version

#original writing#academic essay#uhh#personal essay#autobiography#history#pan africanism#indigenous#indigenous writer#black academia#first nations#native american#creative writing#actuallyindigenous#ojibwe#ojibway#ojibwa#i love how many spellings exist lmao it's hell#saulteaux#nakawe#anishinaabe#treaty 4#prose#indigiqueer#queer#queer writers#uhhh#im running out of ideas#trans writers#riley writes

0 notes

Text

@deezdonuts Indigenous genocide denial allows for the continuation of colonial settler ideology. The manifestation of ethnocentric rapaciousness is the very essence of colonialism. The desire to continue carrying out virulent racist assaults upon us that maintain the subjugation and exploitation of indigenous peoples and lands makes you responsible for genocidal activity. Your poor attempt to scapegoat is aggressive at worst and troublesome at best.

When I say "WE'RE STILL HERE!" it stirs fears, because our stories outline attrition processes and lay the groundwork for defining indigenous genocide. It exposes continental ethnic cleansing, mass murder, torture, and religious persecution, past and present. Yes, present. Your bad behavior here and now is the continuation of genocide.

#native american#knowledge is power#indigenous#genocide#first nations#orange shirt day#reservation#residential schools#60s scoop#american indian#native american holocaust#holocaust#colonial history#settler colonialism#seventh generation#salish#pend d'oreille#kalispel#ojibwe#chippewa#saulteaux#cree#metis#nez perce#neemeepoo#landback#little ice age#n8v#ndn#native

275 notes

·

View notes

Text

hi this is your obligatory reminder from a Mi'kmaq-Saulteaux pal that:

1.) the ribbon skirt is a traditional ceremonial garment worn by many First Nations women to celebrate their connection to Mother Earth and reclaim their Indigenous identity from and in spite of colonization;

2.) the RCMP was literally founded as a colonial police force meant to drive Indigenous / First Nations peoples out of their territory to make way for settlers (see: the "starlight tours")

3.) racism towards indigenous people in Canada is still alive and well (the last residential school didn't close until 1996) and so the RCMP adopting ribbon skirts is not only incredibly tone deaf towards their own history and the role they played in wiping out Indigenous culture, but insulting to the practice of ribbon skirts and what they mean to many Indigenous people across the country

4.) when a government entity limits who can comment on their posts, that should tell you exactly where their priorities and intentions lie.

#P.S. canada is just as bad as the US when it comes to institutionalized racism#we even have the red vs. blue two party system and all the problems that come with it#canada has just done a better job at depicting itself as some kind of wonderland#even our “free healthcare” is a joke#many of us do not have family doctors and have no way of seeking treatment or basic aid#how about we stop running oil pipes thru indigenous land before adopting the ribbon skirt into the RCMP uniform as a form of “reparation"

287 notes

·

View notes

Text

my 2s repost the links should lead to archive links <3

Hi I want to apologize for taking so long to respond, I wanted to get my thoughts together, to answer this properly. This’ll be long.

First, it is important that I define to you what exactly I know and see two-spirit as/to be. I’ll start with the definition from wikipedia: “Two-spirit (also two spirit, 2S or, occasionally, twospirited) is a modern, pan-Indian, umbrella term used by some Indigenous North Americans to describe Native people in their communities who fulfill a traditional third-gender (or other gender-variant) ceremonial and social role in their cultures.”

What I know the usage of the term two-spirit to be, yes, it is quite an umbrella term. I find it used all over Canada and America by Indigenous youth who identify as trans, AND by those who are LGB. As it is in usage now, it seems to just be the catch-all for any GNC or LGB indigenous kid. A label. And although I do think it’s wonderful for any LGB or T-identified or gender non-conforming Indigenous child to find a label that makes themselves comfortable and makes it easier to find others who have the same life experiences, I also think it’s wrong.

The intention of Two-spirit is meant, as we see in the wiki definition, as a catch-all describer of “traditional third-gender, ceremonial and social role in their cultures” for anybody who is North American indigenous. Anon I’m sure you know already but for those that don’t, our roles, typically, are heavily appointed by Elders. You don’t just identify yourself into performing traditions, you are appointed it by elders, or else you ask for their, for lack of better word, blessing. But… you’d be hard pressed to find much of our culture that does this for a “third gender” or “two spirit”.

I can’t speak for every indigenous culture as I was raised mainly into the Cree part of my family and not the Saulteaux/Oji-Cree, but in Cree culture the word of our Elders is sacred. Oral history is how we learn of our culture, in part because we were hit hard in the Canadian genocide of First Nations. I can very safely say, out of all the things I learned from my elders, the only thing I ever had to “teach” them was what Two-spirit meant and what a third-gender is. Because they didn’t know. They could tell me what life was like before they were taken away from the reservation, they could tell me tales of creatures, of Wendigo and Little People, they could tell me and teach me what is sacred to us, what our roles as male and female are, but they couldn’t tell me what Two-spirit is. I had to learn that from the white man. Why is that? Well… possibly because it’s not a thing. It’s not sacred. It isn’t part of the history.

And even if it is in any subset of our cultures, all these kids and indigenous youth who use 2S to identify themselves? They were not appointed the term by elders, they label it themselves.

I think it is important to note here that “Two-spirit” itself was a term first (as we know so far according to Wikipedia, so take that as you will) founded and pushed out of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, which is Treaty 1 territory, home to Anishinaabe. I am not a part of this territory (although I have Elder family members who are from Sandy Bay, who I can confirm also do not know of two-spirit) but one quick search of “anishinaabe third gender” will even only bring up modern day Two-spirit ideas, and the coining of the term in 1990. Same with any search for “(nation) third gender.” I have had a very lovely Anishinaabe anon in the past, and she has also vented her frustration at the use of the term, especially as an umbrella term for any Indigenous kid who is LGB or T, so I do take some assumption there from her that it is also not much of a thing in Ojibwe culture or any of the other Anishinaabe cultures.

What’s most important, and why I oppose it so much (other than the fact that it’s just, as I see, straight up a white man-made concept) is that the term “two-spirit” was created to replace other, more offensive words.

It’s main replacement is for “berdache”, a white (French) word, used against male Indigenous men, particularly homosexual Indigenous men. It is a slur. “Male berdaches did women’s work, cross-dressed or combined male and female clothing, and formed relationships with non-berdache men.”

It is, also, meant sometimes to replace the word, Winkte, or winyanktehca. Lakota meaning ‘wants to be like a woman’. Particularly used against, again, homosexual Lakota men.

It is, also, sometimes used as a replacement for Nádleehi, which was/is used in Diné culture as a word for effeminate males. Particularly used against, you guessed it, homosexual Diné men.

Now, to me, I think it is pretty plain to see that this is a term meant to replace some of our more homophobic terms used in Indigenous communities. But replacing homophobic terms with new ones doesn’t make it any less homophobic. These terms were meant to other homosexual indigenous men, and they were also used by white people. For us to, in this day and age when our culture is shifting to a less homophobic one, use the term two-spirit to continue to other LGB indigenous people? That’s not right to me. There was no reclamation of any of these terms, there was just a white replacement word that doesn’t sound as bad. But it still means the same thing. It’s still as white as a Frenchman calling a gay Indigenous man berdache.

I could keep going on and on, especially about how it is used in current day culture by indigenous youth as a special label, and how none of the people using it seem to actually have talked to their elders about it, but really my biggest problem with it is just how extremely homophobic it is. And how white people use it as “proof” that transgenderism has “always existed” when those same white people don’t even bother to fucking listen when some of us scream at them how wrong they are. And then I could keep going on screaming about how it’s been shoehorned as an acronym onto Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women which is so fucking disrespectful.

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

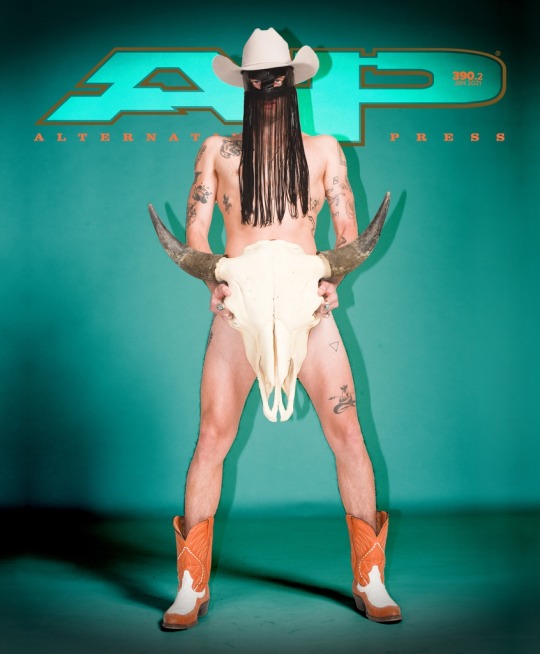

orville peck: appropriation and intellectual property

Orville Peck is a white South African man who has built his entire career off of colonial North American western aesthetics that are directly influenced by Métis and First Nations cultures and aesthetics. This aesthetic is incredibly loaded and has a history that he seemingly has no understanding of other than the fact that often cowboys were queer. In fact, Peck has gone so far as to rip off Métis and Saulteaux artist Dayna Danger.

Fig. 1: Danger, Dayna. Big’Uns: Adrienne, 2017. Courtesy of the artist’s website.

Fig. 2: Orville Peck for Alternative Press Magazine, January 2021

The first image is from a series of similar photographs created by Dayna Danger, well known contemporary artist from Winnipeg, Manitoba. The second image is Orville Peck's cover for Alternative Press magazine's January 2021 issue. In addition to the responsibility of the photographers and stylists to be researching artwork and influences and giving proper credit, it is also up to all parties to understand the colonial implications of the material culture represented in Peck's magazine cover.

Given that Peck is a white South African man I highly doubt he has an actual understanding of how North America was colonized, how animals like bison were hunted into near extinction by white settlers seeking to starve the First Nations and Métis people into extinction as a tool in their ongoing genocide. Many populations of native fauna are still recovering from this practice. In addition to slaughtering millions of animals, white settlers posed proudly with their trophies, mountains of skulls representing the loss of our animals and their triumph over nature and our people.

Fig. 3: Men standing with pile of buffalo skulls, Michigan Carbon Works, Rougeville MI, 1892. Photo from Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Rather than providing an artistic compliment on the history of North American colonialism and cowboy culture, Orville Peck culture hopped from one settler-colonial state to another, to profit from and flatten the aesthetic into something simply rooted in queer culture rather than Black, Mexican, Métis, and First Nations communities and histories.

Works Cited:

Alternative Press. Orville Peck cover, January 2021.

Danger, Dayna. Big'Uns: Adrienne, 2017. https://www.daynadanger.com/photography

Tascheru Mamers, Danielle. Men standing with pile of buffalo skulls, Michigan Carbon Works, Rougeville MI, 1892. Photo from Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library. December 2020.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from this story from Investigate Midwest:

POSTVILLE, Iowa — In March, officials in Postville shut down its water treatment facility for two days as city employees worked to prevent polluted water from a meatpacking plant from entering the water supply.

Agri Star Meat and Poultry had discharged more than 250,000 gallons of untreated food processing waste — blood, chemicals and other solid materials — into the city’s wastewater system. Chris Hackman, the city’s wastewater operator for the past 25 years, said it was one of the worst incidents he could remember.

“We’ve never seen anything like that,” he said.

In majority-white Iowa, most Postville residents are people of color, with more than 40% identifying as Hispanic. Many work at Agri Star Meat and Poultry, the town’s largest employer.

Across the Midwest, meatpacking plants often pollute non-white communities and low-income neighborhoods, according to an Investigate Midwest analysis of two decades of U.S. Environmental Protection Agency enforcement data.

Those bearing the brunt of the pollution are often the same people who work in the facilities responsible for the environmental damage. Meatpacking plants across the region have been cited for various types of pollution in the past 20 years, but water pollution has been the least enforced, a situation the federal government is now trying to address. Sikowis Nobiss, Plains Cree/Saulteaux of the George Gordon First Nation and executive director of the Iowa and Nebraska based environmental justice organization, Great Plains Action, said meatpacking plants most often pollute in rural and low income urban areas where the cost of living is also more affordable for immigrants.

“Do you really think rich people are going to move there?” she asked.

In the past two decades, Postville has recorded the highest number of EPA enforcement cases in Iowa, involving water pollution, air pollution and other negligence charges. Of those five cases, four are linked to Agri Star, according to Investigate Midwest’s analysis.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

First Nations across Saskatchewan are settling claims against the federal government for hundreds of millions of dollars. The settlements, known as "specific claims," are designed to correct historic injustices. The largest single claim was announced earlier this week. Muscowpetung Saulteaux Nation will receive the maximum allowable settlement — $150 million — for a century old, illegal land surrender. Muscowpetung is located approximately 80 kilometres northeast of Regina. In 1909, the federal government illegally seized half of Muscowpetung's reserve land — a total of more than 7,400 hectares. Chief Melissa Tavita said Muscowpetung leaders made the initial claim to the federal government in the 1990s. She said it should not have taken this long, but she's glad it's finally over.

Continue Reading.

Tagging: @politicsofcanada

79 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jaye Simpson

Gender: Transgender Non binary (they/them)

Sexuality: Queer

DOB: N/A

Ethnicity: First Nation (Oji, Cree, Saulteaux)

Nationality: Canadian

Occupation: Writer

#Jaye Simpson#lgbt#lgbtq#enby#bipoc#transgender#non binary#queer#first nation#native#biracial#poc#canadian#writer#plus size

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yorei's OC Meme

The First Character I ever created was Russell. He is my precious son, from the moment of his creation, I have always loved him. He is literally someone I wish I could've had in my life as a friend or family member. In this drawing he is stimming, he's not in a good mindset right now and he stims whenever he is worried about something.My Newest Character is Jacey "Brickwall" Weekuskis. I created her completely by accident as part of OC-Training, she gets into an argument with Hale about her not considering him true First Nations. She's an activist from Calgary, Alberta, Canada, and she is of Néhinaw (Cree), Saulteaux, Assiniboine, and Niitsitapi-Siksikaitsitapi (Blackfoot) descent.My Current Favorite Character is your wacky, sensual man Hale. He is like an inspiration to me sometimes, I wish I could have his mindset in the real world and I wish I could be like him without people thinking I'm weird in real life. My Most Underappreciated Character I think would have to be Itzapa, the Interrogator of The Jade owls. A lot of people overlook her because of her intimidating appearance. Yes, she is scary sometimes, but she is actually pretty nice deep down, she has a good connection to Russell and Kasai and does what she can to keep them, and by extent all of her teammates safe. She went through a lot as a Battle Slave, but now that she is free she is taking advantage of it in every way she can by seeing the world and meeting new people.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Milan Fashion Week First Indigenous Designers

This Fashion Week in Milan hosted the first Indigenous Showcase. This is the first time Indigenous creators have been invited to Milan Fashion Week. The exhibit was at the White Market and was accompanied by a panel about the Indigenous way.

Robyn McLeod, co-owner of fromthelandcreations, with her sister, Shawna. They’re Dene and Metis ancestry and are from Deh Gah Gotie First Nation. Robyn has her brand characterized by Dene Futurism.

Dene Futurism / fromthelandcreations beadwork / Display in the WHITE Market

Justin Louis creative director of Indigenous streetwear brand SECTION 35. He is Samson Cree and was raised on Treaty 6 Land. He is wearing one of the more popular designs of the brand that was on display at Milan. The name section 35 refers to the redraft of the Constitution Act in 1982 to reaffirm Indigenous rights in Canadian law. Early drafts did not include any mention of Indigenous people’s rights or respecting Indigenous relationships.

Jacket by Section 35, earrings by She Was A Free Spirit, moccasins by arcticoceanmocs /Milan Set Up

Evan Ducharme is a Metis creator raised on Treaty 1 land. He has ancestors from Cree, Ojibwe and Saulteaux. His work explores Metis history, pop culture, gender and queerness. Ducharme mixes contemporary and ancestral Metis culture and knowledge in his world to create modern statements and expressions of indigeneity.

On display in Milan

Niio Perkins is from Akwesasne, New York, Mohawk territory, where she learned how to sew from her seamstress mother in a fashion house. Her mother Elizabeth became popular for her vibrant designs showing Mohawk pride. She uses Haudenosaunee traditional beading method and glass beads to make her intricate pieces shine. For Milan, she released her “Icon” jewellery collection, consisting of some of her most popular pieces throughout the decades. The collection has eight iconic designs and twenty-five pieces.

Traditional Haudenosaunee Woman’s Outfit / From the Icon Collection

Erica Donovan, an Inuvialuk artist from Tuktoyaktuk, North West Territories is the owner and founder of the brand She Was A Free Spirit. She takes inspiration from her culture, her and her ancestors home, and her love for colour. She describes her work as “a vibrant geometric take of my Inuvialuit culture”

Arctic Sky Earrings / Donovan wearing her own earring

Lesley Hampton, an Anishinaabe and Mohawk designer, is a popular artist who made a size-inclusive brand that was worn at the Emmy Award Show and by celebrities like Lizzo. In 2021, she was named the Number One Canadian brand to look out for by Vogue.

Notable Works in Her Exhibit

Photo Credits and Where to Find Them:

Robyn McLeod: (Website) (Insta) (Facebook)

Of Artist

First Photo

Second Photo

Third Photo

Justin Louis / Section 35: (Website) (Insta) (Insta) (Facebook) (Twitter)

Of Artist

First and Second Photo

Evan Ducharme: (Facebook) (Website) (Insta) (Twitter)

Of Artist

First and Second Photo

Niio Perkins: (Website) (Facebook) (Insta)

Of Artist

First and Second Photo

Erica Donovan / She Was A Free Spirit: (Facebook) (Insta) (Website)

Of Artist

First Photo

Second Photo

Lesley Hampton: (Insta) (Website) (Twitter)

Of Artist

First and Second Photo

Third Photo

#milan#milan fashion week#milan fashion show#milan 2023#milan fashion week 2023#milan fashion 2023#milan fashion show 2023#indigenous#native american#aboriginal#metis#fashion#high fashion#mine

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Red is Beautiful

Contemporary Art by Robert Houle (Saulteaux Anishinaabe, Sandy Bay First Nation, b. 1947)

#dc#national museum of the american indian#national mall#museum#national museum of the american#washington#august#around dc#my work#photography

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Happened on September 22 in Canadian History?

Canada’s rich history is marked by numerous pivotal events that have shaped its political, cultural, and social landscape. Some of these moments took place on September 22, a date that has witnessed significant treaties between the government and Indigenous peoples, influential visits from international figures, and the birth and death of key Canadian political leaders. These events reflect the diversity and complexity of Canadian history, from the country’s colonial past to its modern era. This article will explore what happened on September 22 in Canadian history, covering a range of milestones, each of which has contributed to shaping Canada as we know it today.

What Happened on September 22 in Canadian History?

Treaty 4 Signed at Fort Qu’Appelle (1875)

On September 22, 1875, the signing of Treaty 4 at Fort Qu’Appelle, Saskatchewan, was a landmark event in Canadian history. This treaty was part of a series of numbered treaties that the Canadian government signed with various Indigenous nations throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Treaty 4 specifically involved the Cree, Saulteaux (Chippewa), and other First Nations who inhabited the areas that would later become southern Saskatchewan, parts of Manitoba, and parts of Alberta. The signing of the treaty was meant to facilitate European settlement in the region while providing Indigenous groups with certain rights and compensations in return for ceding large tracts of their land to the Canadian government.

The context of Treaty 4 is crucial to understanding its impact. At the time, Indigenous peoples were facing increasing pressure from European settlers, who sought land for agriculture and development. The Canadian government was keen to expand westward and secure the newly acquired lands of the Northwest Territories, which included present-day Saskatchewan. For Indigenous peoples, the treaty was seen as a way to ensure their survival amid the depletion of natural resources like the buffalo, which had traditionally sustained their economies and way of life.

However, the implementation of Treaty 4, like many other numbered treaties, was fraught with difficulties. Indigenous leaders often entered into the treaties with a different understanding of the agreements compared to the Canadian government, leading to long-term disputes over land rights, education, and healthcare provisions. While Treaty 4 guaranteed certain rights to Indigenous groups, such as the establishment of reserves and financial compensation, many of these promises were either delayed or inadequately fulfilled by the government. The legacy of Treaty 4 continues to be a topic of discussion and debate, particularly in the context of ongoing reconciliation efforts between Canada and Indigenous peoples.

Pope John Paul II Visits Fort Simpson (1987)

On September 22, 1987, Pope John Paul II made a historic visit to Fort Simpson, Northwest Territories, a remote community in Canada’s north. The visit was initially scheduled for 1984 as part of the Pope’s broader tour of Canada, but poor weather had forced him to cancel his plans to visit the region. However, the Pope made a promise to the Indigenous peoples of Fort Simpson that he would return, and in 1987, he fulfilled that promise. His visit to Fort Simpson held significant meaning for both the Catholic Church and Indigenous communities, as it marked a moment of spiritual dialogue and healing.

The Pope’s visit was part of his broader mission to engage with Indigenous populations around the world, and his message in Fort Simpson was one of reconciliation and respect for Indigenous cultures. At the time, Indigenous issues were becoming increasingly prominent in Canadian politics, with growing calls for the recognition of Indigenous rights and land claims. The Pope’s presence in Fort Simpson provided a platform for these issues to be addressed on an international stage, and his words resonated with many in attendance.

During the visit, Pope John Paul II celebrated mass and delivered a homily that emphasized the dignity of Indigenous peoples and the importance of their cultural and spiritual traditions. He acknowledged the historical injustices that had been inflicted upon Indigenous populations, particularly in the context of colonization and residential schools, many of which were run by the Catholic Church. The Pope’s visit to Fort Simpson, though brief, was seen as a step toward healing and reconciliation between the Church and Indigenous peoples in Canada. It also underscored the global attention being paid to the struggles of Indigenous communities in the late 20th century, an issue that continues to shape Canadian politics and society today.

Birth of John Diefenbaker (1895)

On September 22, 1895, John George Diefenbaker, Canada’s 13th prime minister, was born in Neustadt, Ontario. Diefenbaker would go on to have a profound impact on Canadian politics, serving as prime minister from 1957 to 1963. He was the first prime minister of Canada of neither French nor English descent, a distinction that set him apart in a country long dominated by leaders from these two cultural groups. Diefenbaker’s legacy is complex, but he is perhaps best remembered for his passionate defense of civil rights and his efforts to unite Canadians across cultural and regional divides.

Diefenbaker was a staunch advocate for the rights of the “average Canadian.” His government passed the Canadian Bill of Rights in 1960, a precursor to the later Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The Bill of Rights was the first federal law to protect Canadians’ fundamental freedoms, such as freedom of speech, religion, and assembly. Although the Bill of Rights was not as comprehensive as the later Charter, it represented an important step toward recognizing and protecting civil liberties in Canada.

Diefenbaker was also known for his support of Indigenous rights. His government extended the federal vote to Indigenous Canadians in 1960, allowing them to participate in federal elections without being required to give up their treaty status. This move was a significant step toward the recognition of Indigenous peoples as full citizens of Canada. However, Diefenbaker’s tenure as prime minister was not without its controversies. His handling of economic issues and his decision to cancel the Avro Arrow, a Canadian-developed supersonic jet, remain points of debate. Nonetheless, Diefenbaker’s contributions to civil rights and his vision of a united Canada continue to influence the country’s political landscape.

Death of John Turner (2020)

On September 22, 2020, Canada mourned the passing of John Turner, the 17th prime minister of Canada. Turner, a Liberal politician, served as prime minister for only 79 days in 1984, one of the shortest terms in Canadian history. Despite his brief tenure, Turner had a long and distinguished political career, holding various key cabinet positions throughout the 1960s and 1970s, including Minister of Justice and Minister of Finance.

Turner was widely respected for his intelligence, integrity, and dedication to public service. As Minister of Justice, he introduced landmark legislation, including reforms to the Criminal Code and the Official Languages Act, which strengthened bilingualism in Canada. Turner’s time as Minister of Finance saw him navigate the challenges of a fluctuating economy, and he was known for his pragmatic approach to fiscal policy.

Though his brief time as prime minister was marked by political challenges, including tensions within the Liberal Party and a difficult national election, Turner remained a respected figure in Canadian politics. His legacy as a champion of justice and bilingualism, as well as his long career in public service, continues to be recognized by Canadians.

Conclusion

Throughout Canadian history, September 22 has been a day of significant events, from the signing of critical treaties with Indigenous nations to the births and deaths of prominent political leaders. The events of this date highlight the complexity of Canada’s history, reflecting its colonial past, its evolving relationship with Indigenous peoples, and the contributions of its political figures. As Canadians continue to reflect on their history, these events serve as reminders of the ongoing processes of negotiation, reconciliation, and leadership that have shaped the nation’s identity over time.

0 notes

Note

OOOH HI I'm also First Nations, I'm specifically Plains Cree

In our language, Nêhiyawêwin, we refer to ourselves as "Nêhiyaw"

I was taught that it means something along the lines of four bodied person or people of the four directions, because 4 is a really important number in our culture.

Also, there is no actual number 9 in our language.

We have 10, which is "mitâtaht" and nine is "kêkâ-mitâtaht," which means almost 10

I do not know why

Tansi!! Love seeing another First Nations pal in my inbox 👏❤️

I actually have to brush up on a lot of my Cree as well because fun fact - my grandmother hails from the plains, specifically (from what she's been able to retrace) the Saulteaux tribe which is (from what I've learned of it) a sort of branching tribe of the Ojibwe, so when we got our status returned to us back in the late 2000's / early 2010's, we were registered as Cree because the Canadian government do be like that LMAO But all of her children and their children - including me - were born in the Maritimes so some of us identify as Mi'kmaq simply due to all of us being born in Atlantic Canada (and a lot of this was before we had even figured out the Saulteaux part of our heritage). Tracing back our heritage has been admittedly very difficult because our grandmother was unfortunately a victim of residential schooling and was taken away from much of her family in the plains as a child, and then she subsequently lost her Indigenous status completely when she married a French man back when such laws were in place. It's sort of a bittersweet experience because on the one hand it's been amazing to get back in touch with our culture but on the other it's because of colonization that we've had to go to all this effort in the first place just to figure out where we come from and who we are u.u Needless to say, I still feel very spiritually connected to the land I was born in, but I also want to be open to recognizing my grandmother's heritage and keeping it alive as best I can <3

That's so funny that there's no specific number for 9, I wonder why that is 🤔 it's like our ancestors got tired of coming up with unique names and went "fuck it, it's almost ten" LOL now I'm almost curious to know if the Mi'kmaq language did the same thing, I'll have to look into that 💀😆

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

I created this in 2o2o. 🖌️

There are no mistakes in art. Even tho I felt like I messed up on this painting, I decided to keep going and let my brush strokes guide me.

It gives chaos and that is exactly what 2o2o was. It gives “what is it?” and “what’s going on?” And those were the feelings I had that manifested on to this canvas.

When I look closely, it resembles a witch mixed with a bird. And that is when it dawned on me. Did I accidentally paint a #windigo ? 🦅

A wendigo is a supernatural being belonging to the spiritual traditions of Algonquian-speaking First Nations in North America. Windigos are described as powerful monsters that have a desire to kill and eat their victims. In most legends, humans transform into windigos because of their greed or weakness.

The wendigo is part of the traditional belief system of a number of Algonquin-speaking peoples, including the Ojibwe, the Saulteaux, the Cree, the Naskapi, and the Innu.

I am #NativeAmerican so I know the #folklore of this creature. The first time I ever read about this being was in one of my fave childhood books by #AlvinShwartz 🪶

‘The Wendigo’ is a story from Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark. It tells the story of a monster that originates from #NativeAmerican legend. It's also a retelling of the Algerton Blackwood 1910 novella The Wendigo.I love this painting. ✨ I name it ~ #TheWendigo

1 note

·

View note