#saterland frisian

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

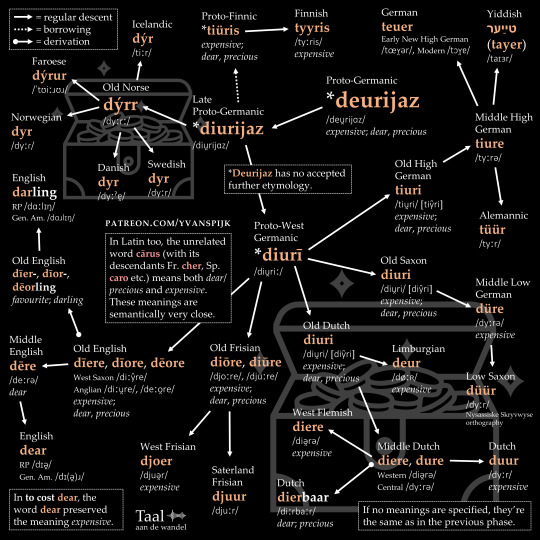

Dear means 'valued; precious; beloved'. However, in certain expressions it also means 'expensive', such as in to cost dear. This meaning, inherited from Proto-Germanic, became dominant in cognates of dear, such as Dutch duur, German teuer, and Swedish dyr. The infographic tells you the whole story.

#historical linguistics#linguistics#language#etymology#english#dutch#german#low saxon#frisian#old frisian#old saxon#old high german#old english#old dutch#middle high german#middle dutch#middle english#middle low german#lingblr#proto-germanic#proto-west germanic#yiddish#west flemish#limburgian#saterland frisian#faroese#icelandic#norwegian#swedish#danish

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deutschribing Germany

Languages

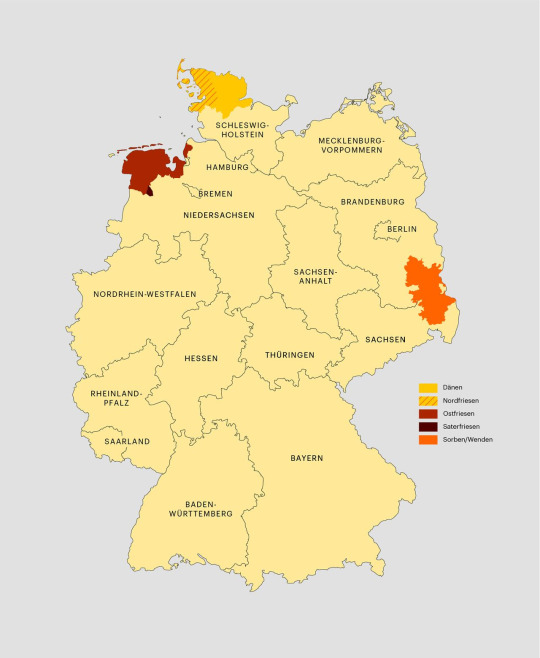

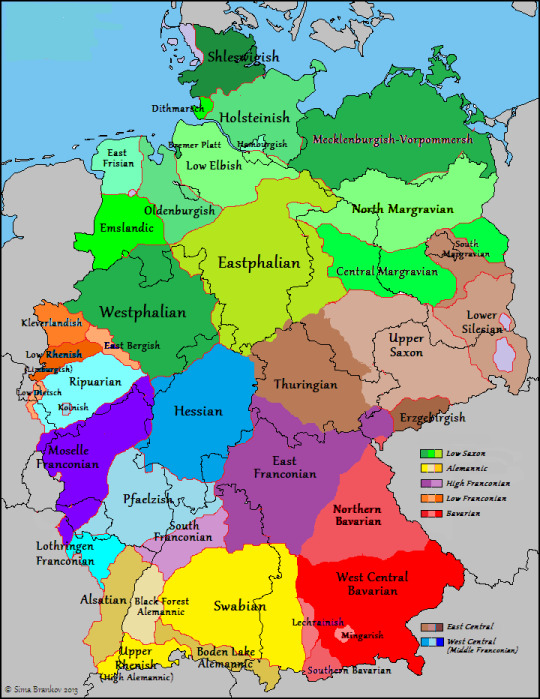

Most languages native to Germany belong to the Germanic family, but some of them are Slavic languages. German is the official language, with over 95% of the country speaking Standard German or one of its dialects as their first language.

There are six recognized minority languages: Danish, Lower Sorbian, North Frisian, Romani, Saterland Frisian, and Upper Sorbian. The main immigrant languages spoken are Arabic, Dutch, Greek, Italian, Kurdish, Polish, Russian, Serbo-Croatian, Tamil, Turkish, and Ukrainian.

German (Deutsch)

German belongs to the West Germanic group of languages and is the native language of 95 million people. It is the official language in Austria, Belgium, Germany, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, and Switzerland, as well as South Tyrol in Italy, and is a recognized minority language in ten countries from four different continents.

German Standard German is the standardized variety of German spoken in Germany. Its pronunciation is similar to the German spoken in Hanover. Its alphabet has 30 letters: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z ä ö ü ß. Most German vocabulary is of Germanic origin, but around one fifth was taken from French or Latin. German dialects and varieties are explained in detail in this post.

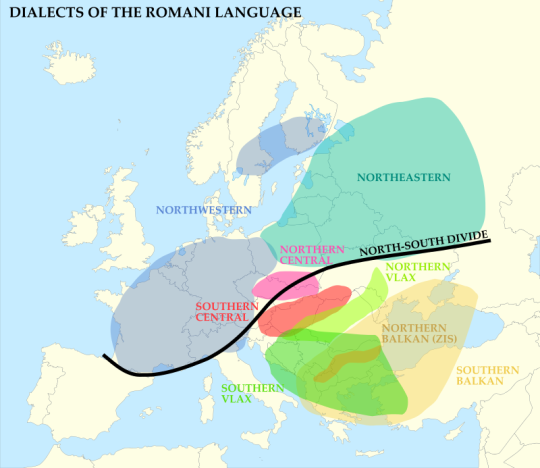

Romani (rromani ćhib)

Sinte Romani (sintitikes) is the variety of Romani spoken in Germany and neighboring countries. It belongs to the Northwestern Romani dialect group, which in turn is part of the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European family. It is spoken by around 195,000 people and is not mutually intelligible with other Romani varieties.

There is no standard pronunciation or grammar. The alphabet has 31 letters: a b c č čh d dž e f g h i j k kh l m n o p ph r s š t th u v x z ž.

Danish (dansk)

Danish is a North Germanic language with 6 million native speakers. It is the official language of Denmark and the Faroe Islands and a recognized minority language in Schleswig-Holstein and Greenland.

The Danish alphabet has 29 letters, including the 26 found in the English one and æ, ø, and å.

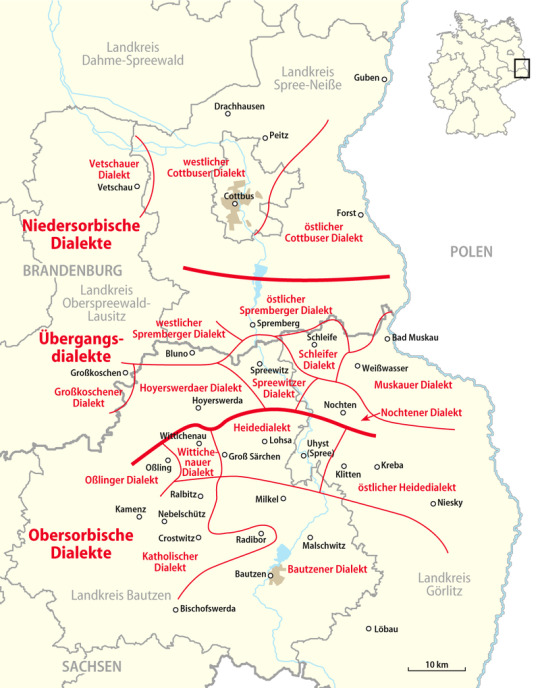

Upper Sorbian (hornjoserbšćina)

Upper Sorbian (Obersorbische Dialekte in the map) belongs to the West Slavic branch and is recognized as a minority language in Saxony, where its 13,000 native speakers live.

Its alphabet has 34 letters: a b c č ć d dź e ě f g h ch i j k ł l m n ń o ó p r ř s š t u w y z ž.

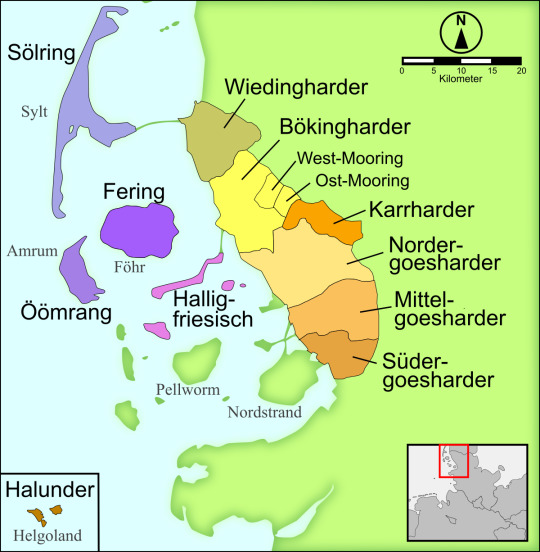

North Frisian (Nordfriisk)

North Frisian is part of the West Germanic branch and is spoken natively by 10,000 people in Schleswig-Holstein. It comprises 10 dialects, which are divided into two groups: insular and mainland.

Its phonology and orthography vary depending on the dialect, but there are 32 basic letters: a ä å b ch d dj đ/ð e f g h i j k l lj m n ng nj o ö p r s sch t tj u ü w.

Lower Sorbian (dolnoserbšćina)

Lower Sorbian (Niedersorbische Dialekte in the map of Sorbian dialects) is a West Slavic language spoken natively by 6,900 people in Brandenburg.

It uses the same letters as Upper Sorbian but adds ś and ź and uses ŕ instead of ř, bringing the total number of letters to 36.

Saterland Frisian (Seeltersk)

Saterland Frisian belongs to the West Germanic branch and is recognized as a minority language in Lower Saxony. It is spoken by 2,200 people and has three fully mutually intelligible dialects.

Its orthography has not been standardized yet, but there are 31 common letters: a ä b ch d e f g h i ie j k/kk ks kw l m n ng o oa ö p r s sch t u ü v w.

Here is Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in the native languages of Germany:

German: Alle Menschen sind frei und gleich an Würde und Rechten geboren. Sie sind mit Vernunft und Gewissen begabt und sollen einander im Geist der Brüderlichkeit begegnen.

Romani: Sa e manušikane strukture bijandžona tromane thaj jekhutne ko digniteti thaj capipa. Von si baxtarde em barvale gndaja thaj godžaja thaj trubun jekh avereja te kherjakeren ko vodži pralipaja.

Danish: Alle mennesker er født frie og lige i værdighed og rettigheder. De er udstyret med fornuft og samvittighed, og de bør handle mod hverandre i en broderskabets ånd.

Upper Sorbian: Wšitcy čłowjekojo su wot naroda swobodni a su jenacy po dostojnosći a prawach. Woni su z rozumom a swědomjom wobdarjeni a maja mjezsobu w duchu bratrowstwa wobchadźeć.

North Frisian: Ali Mensken sen frii, likwērtig en me disalev Rochten bēren. Ja haa Forstant en Giweeten mefingen en skul arküđer üs Bröđern öntöögentreer. (Sylt/Sölring dialect)

Lower Sorbian: Wšykne luźe su lichotne roźone a jadnake po dostojnosći a pšawach. Woni maju rozym a wědobnosć a maju ze sobu w duchu bratšojstwa wobchadaś.

Saterland Frisian: Aal do Moanskene sunt fräi un gliek in Wöide un Gjuchte gebooren. Joo hääbe Fernunft un Gewieten meekriegen un schällen sik eenuur as Bruure ferhoolde. (Ramsloh dialect)

Translation: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fun fact: "Touden" is a "thorn" in Saterland Frisian

#they don't have a canon ethnicity aside from being “northern”#but it's cool to know#dungeon meshi#laios touden#falin touden#dungeon meshi meta#maybe it's a common knowledge but i just found out#maybe that's why they were also thordens?

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

X-Men and Cultural Appropriation

I pretty much pointed out how the X-Men writers have indulged in cultural appropriation to varying degrees, in the sense that the mutants are stand-ins for ethnic minorities but most of them don’t speak minority languages. Mind you, minority languages are minority because they’re not commonly spoken due to being stigmatised and discouraged. People would get whacked if they spoke in such a language, whilst this never really happened in the X-Men stories as far as I remember. It doesn’t help when at least most X-Men writers either don’t speak any minority language or bother learning it, which would explain the ironically appropriative air X-Men stories give off.

Like they co-opt minority experiences but almost none of the writers are either into minority cultures nor are they minorities themselves, this is likely why both Sean and Theresa Cassidy fit Irish stereotypes but neither of them speak Irish. It wouldn’t hurt if Rahne Sinclair actually spoke Scots instead of weird butchered English she sometimes she’s slotted into, I don’t think there are any mutants who speak Venetian, Lombard/Milanese, Low German and Saterland Frisian either. Again this involves a greater admiration for something this marginalised as a minority language of any given country than is commonly shown and done in X-Men comics, honestly I got into Irish because of loving Irish foik music.

So there is a difference between cultural appreciation and cultural appropriation, the former involves actually loving and respecting the culture in question and the other makes a mockery out of it when borrowed though sometimes they are blurred together. (Trust me, it’s like that with me when it comes to China until recently.) The X-Men stories and their respective writers frequently fall into the latter, especially when it comes to non-American and/or nonwhite mutants. This is likely why as I said before, both Cassidys are Irish stereotypes who neither speak Irish to any degree.

It’s kind of tragic when you realise how there is a difference between reiterating ethnic stereotypes and having any real appreciation for/interest in certain cultures, this may not always be the case but it seems in my case my interest in Ireland stemmed from learning Irish from Irish folk music. I don’t think X-Men stories ever lead me to loving foreign cultures the way I did with Irish folk music, so it becomes really evident that X-Men writers have co-opted the experiences of minorities for their characters and stories but show no real interest in those people themselves.

It’s not just that Siryn and her father are Irish stereotypes (or at least started out as such), but how the other mutants don’t speak any minority language which would’ve furthered the minority comparison more. There aren’t any mutants who speak Lombard, Venetian, Breton, Welsh, Frisian, Low German, Sicilian, Sardinian, Scots, Scottish Gaelic, Kurdish and Nahuatl, maybe until recently, despite X-Men writers’ tendency to harp on mutants as the ultimate minority, the minority of all minorities within Marvel stories. You might say that they’re obscure and irrelevant, but they are important markers of social identity to some people.

If I were to compare X-Men to any one of the Milestone stories (Icon and Blood Syndicate), the latter two are written by members of actual minorities so there’s going to be an authenticity that most X-Men stories lack. If X-Men writers and stories alike reveal an insincerity in showing the (ethnic) minority perspective, this could partly explain why not a lot of mutants speak minority languages. This may not always be the case, but it is telling how this aspect of social identity gets missed out. If X-Men stories are inadequate and untrustworthy when it comes to the minority language, perhaps something else does.

One that even outdoes X-Men when it comes to portraying ethnic/linguistic minorities at all, especially when written by actual minorities and/or those who speak minority languages.

#irish language#ireland#x-men#marvel#marvel comics#minority language#minority languages#cultural appropriation#siryn#theresa cassidy#sean cassidy#milestone comics#scots#scots language#rahne sinclair

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

luck

From Middle English luk, lukke, related to Old Frisian luk (“luck”), West Frisian gelok (“luck”), Saterland Frisian Gluk (“luck”), Dutch geluk (“luck, happiness”), Low German luk (“luck”), German Glück (“luck, good fortune, happiness”), Danish lykke (“luck”), Swedish lycka (“luck”), Icelandic lukka (“luck”). According to the OED, it may be related to lock.

Loaned into English in the 15th century (probably as a gambling term) from Middle Dutch luc, a shortened form of gheluc (“good fortune”), whence Modern Dutch geluk. Middle Dutch luc, gheluc is paralleled by Middle High German lücke, gelücke (modern German Glück). The word occurs only from the 12th century, apparently first in Rhine Frankish. Perhaps from a Frankish *galukki. The word enters standard Middle High German during the 13th century, and spreads to English and Scandinavian in the Late Middle Ages. Its origin seems to have been regional or dialectal, and there were competing German words such as gevelle or schick, or the Latinate fortūne from Latin fortūna. Its etymology is unknown, although there are numerous proposals as to its derivations from a number of roots.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

wilderness

From Middle English wildernes, wildernesse (“uninhabited, uncultivated, or wild territory; desolate land; desert; (figuratively) depopulated or devastated place; state of devastation or ruin; human experience and life”) [and other forms],[1] and then either:

from Middle English wilderne (“deserted or uninhabited place, wilderness; land not yet settled”) [and other forms] (from Old English wilddeōren (“savage, wild”); see below)[2] + -nes, -nesse (suffix forming abstract nouns denoting qualities or states);[3] or

from Old English *wildēornes, *wilddēornes, probably from wilddēor (“wild animal”) [and other forms] or more likely from wilddēoren (“savage, wild”) (from wilddēor + -en (suffix forming adjectives with the sense ‘consisting of; material made of’)) + -nes (suffix forming abstract nouns denoting qualities or states).[4]

Wilddēor is derived from wilde (“savage, wild”) (ultimately either from Proto-Indo-European *wel-, *welw- (“hair, wool; ear of corn, grass; forest”), or *gʷʰel- (“wild”)) + dēor (“beast, wild animal”) (ultimately from Proto-Indo-European *dʰwes- (“to breathe; breath; soul, spirit; creature”)).

The English word is cognate with Danish vildnis (“wilderness”),

German Wildernis, Wildnis (“wilderness”),

MiddleDutch wildernisse (“wilderness”)

(modern Dutch wildernis (“wilderness”)),

Middle Low German wildernisse (“wilderness”)

(German Low German Wildernis (“wilderness”)),

Saterland Frisian Wüüldernis (“wilderness”),

West Frisian wyldernis (“wilderness”).

Sense 3.3 (“situation of disfavour or lack of recognition”) is a reference to Numbers 14:32–33 in the Bible (King James Version; spelling modernized): “But as for you, your carcasses, they shall fall in this wilderness. And your children shall wander in the wilderness forty years, and bear your whoredoms, until your carcasses be wasted in the wilderness.”

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

From Middle English newes, newys (“new things”), equivalent to new (noun) + -s. Compare Saterland Frisian Näis (“news”), East Frisian näjs ("news"), West Frisian nijs (“news”), Dutch nieuws (“news”), German Low German Neeis (“new things; news”), though unlike the English word, these originated as genitives, not plurals. Sometimes erroneously claimed to be an acronym of "North, East, West, South" or "Noteworthy Events, Weather, Sports".

"i was today years old when I learned [the most blatantly untrue folk etymology you've ever heard]!!"

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

Weird finding of the day:

I always assumed poll and politics were very closely related words. Like one coming from the other close. I mean, just look at ‘em.

But, apparently not. They come from different sides of the English family tree.

Poll is of Germanic origin while Politics is Latinate, stolen from Greek.

So:

From Online Etymology Dictionary

Poll

As a noun

c. 1300 (late 12c. as a surname), polle, "hair of the head; piece of fur from the head of an animal," also (early 14c.) "head of a person or animal," from or related to Middle Low German or Middle Dutch pol "head, top." The sense was extended by mid-14c. to "person, individual" (by polls "one by one," of sheep, etc., is recorded from mid-14c.)

Meaning "collection or counting of votes" is recorded by 1620s, from the notion of "counting heads;" the sense of "the voting at an election" is by 1832. The meaning "survey of public opinion" is recorded by 1902. A poll tax, literally "head tax," is from 1690s. Literal use in English tends toward the part of the head where the hair grows.

As a verb

1620s, "to take the votes of," from poll (n.) [the above] in the extended sense of "individual, person," on the notion of "enumerate one by one." Sense of "receive (a certain number of votes) at the polls" is by 1846. Related: Polled; polling. Polling place is attested by 1832.

From Wiktionary

From Middle English pol, polle ("scalp, pate"), probably from or else cognate with Middle Dutch pol, pōle, polle (“top, summit; head”),[1] from Proto-West Germanic *poll, from Proto-Germanic *pullaz (“round object, head, top”), from Proto-Indo-European *bolno-, *bōwl- (“orb, round object, bubble”), from Proto-Indo-European *bew- (“to blow, swell”).

Akin to Scots pow (“head, crown, scalp, skull”), Saterland Frisian pol (“round, full, brimming”), Low German polle (“head, tree-top, bulb”), Danish puld (“crown of a hat”), Swedish dialectal pull (“head”). Meaning "collection of votes" is first recorded 1625, from notion of "counting heads".

While on the Politics side:

1520s, "science and art of government," from politic (n.) "the political state of a country or government (early 15c.), from Old French politique and Medieval Latin politica; see politic (adj.). The plural form probably was modeled on Aristotle's ta politika "affairs of state" (plural), the name of his book on governing and governments, which was in English mid-15c. as (The Book of) Polettiques or Polytykys. Also see -ics.

Politic adj.

early 15c., politike, "pertaining to public affairs, concerning the governance of a country or people," from Old French politique "political" (14c.) and directly from Latin politicus "of citizens or the state, civil, civic," from Greek politikos "of citizens, pertaining to the state and its administration; pertaining to public life," from polites "citizen," from polis "city" (see polis).It has been replaced in most of the earliest senses by political. From mid-15c. as "prudent, judicious," originally of rulers: "characterized by policy." Body politic "a political entity, a country" (with French word order) is from late 15c.

And from wiktionary

From the adjective politic, by analogy with Aristotle’s τα πολιτικά (ta politiká, “affairs of state”).

Politic

From Middle French politique, from Latin politicus, from Ancient Greek πολιτικός (politikós), from πολίτης (polítēs, “citizen”). Cognate with German politisch (“political”). Doublet of politico.

So… yeah. Not what I expected. Interesting, random discovery for today. Apropos of nothing at all.

1 note

·

View note

Text

According to wiktionary there’s seven etymologically distinct words that ended up as English “mole”, seems like unusually many.

The animal sense comes from

Middle English molle (“mole”), molde, mole, ultimately from Proto-Germanic *mulaz, *mulhaz (“mole, salamander”), from Proto-Indo-European *molg-, *molk- (“slug, salamander”)

Cognate with North Frisian mull (“mole”), Saterland Frisian molle (“mole”), Dutch mol (“mole”), Low German Mol, Mul (“mole”), German Molch (“salamander, newt”), Old Russian смолжь (smolžʹ, “snail”), Czech mlž (“clam”).

What a strange semantic shift. Slug, snail, clam, salamander... mole?

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

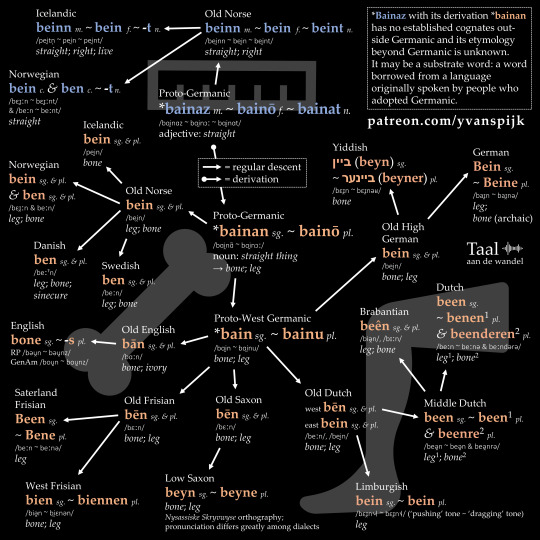

Bone & Bein

The word bone has the same origin as German Bein, Dutch been, and Swedish ben, which mean both 'bone' and 'leg'. These nouns are thought to stem from an adjective meaning 'straight'. It lives on in Icelandic beinn and Norwegian be(i)n 'straight; right'.

#historical linguistics#linguistics#language#etymology#english#dutch#german#old english#old dutch#old high german#old saxon#low saxon#old frisian#west frisian#old norse#norwegian#danish#swedish#lingblr#catalan#limburgish#brabantian#yiddish#saterland frisian

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

[PT: Abigender, Iemegender, Genderseillan, and Lapagender

Abigender: a gender that is like a group of bee genders that come together to build a “hive” where new genders are produced and created.

Etymology: Campidanese Sardinian, “abi” meaning “bee”

Iemegender: a gender that is like a group of bee genders that come together to "sting” genders they find unusable and to replace them.

Etymology: Saterland Frisian, “Ieme” meaning “bee”

Genderseillean: a gender that is like a bee flying around a sunflower field.

Etymology: Scottish Gaelic, “seillean” meaning “bee”

Lapagender: a gender that is like a bee flying around a tulip field.

Etymology: Sicilian, “lapa” meaning “bee” /end PT]

@radiomogai

Abigender, Iemegender, Genderseillan, and Lapagender

Abigender: a gender that is like a group of bee genders that come together to build a “hive” where new genders are produced and created. Etymology: Campidanese Sardinian, “abi” meaning “bee”

Iemegender: a gender that is like a group of bee genders that come together to “sting” genders they find unusable and to replace them. Etymology: Saterland Frisian, “Ieme” meaning “bee”

Genderseillean: a gender that is like a bee flying around a sunflower field. Etymology: Scottish Gaelic, “seillean” meaning “bee”

Lapagender: a gender that is like a bee flying around a tulip field. Etymology: Sicilian, “lapa” meaning “bee”

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Languages of the world

Saterland Frisian (Seeltersk)

Basic facts

Number of native speakers: 2,000

Recognized minority language: Germany

Script: Latin, 41 letters

Grammatical cases: 0

Linguistic typology: fusional, SVO/SOV, V2

Language family: Indo-European, Germanic, West Germanic, North Sea Germanic, Anglo-Frisian, Frisian, East Frisian

Number of dialects: 3

History

19th century - beginning of the decline of Saterland Frisian

1950s - development of the orthography

Writing system and pronunciation

These are the letters that make up the alphabet: a aa ä äa b ch d e ee f g h i ie íe j k ks kw l m n ng o oa oo ö öä öö p r s sch t u uu ü üü v w.

There is a one-on-one correspondence between sounds and letters.

Grammar

Nouns have three genders (masculine, feminine, and neuter), two numbers (singular and plural), and no cases. Only pronouns have cases.

Numbers one through three vary based on the gender of the noun they accompany.

Verbs are conjugated for tense, mood (indicative and imperative), person, and number.

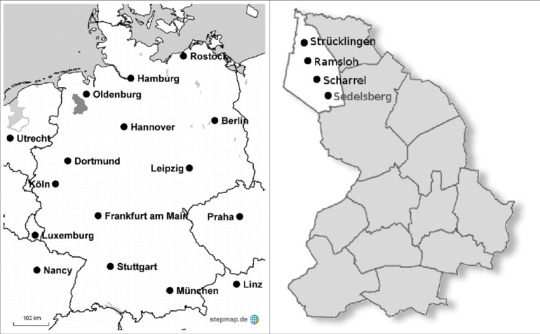

Dialects

There are three dialects: Ramsloh, Scharrel, and Strücklingen. They are all fully mutually intelligible.

Ramsloh enjoys a status as the standard language.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Etymology, English, One

Etymology From Middle English one, on, oan, an, from Old English ān (“one”), from Proto-West Germanic *ain, from Proto-Germanic *ainaz (“one”), from Proto-Indo-European *óynos (“single, one”). Cognate with Scots ae, ane, wan, yin (“one”); North Frisian ån (“one”); Saterland Frisian aan (“one”); West Frisian ien (“one”); Dutch een, één (“one”); German Low…

View On WordPress

#all for one#all in one#are you the one#capital one#credit one#google one#how much is one bitcoin#last one laughing#moto one fusion#nike waffle one#no one#one america news#one bank#one day#one direction#one drive#one line#one login#one love#one movie#one night#one night in miami#one on one#one piece#one piece 1001#one piece 1012#one piece 1021#one piece 993#one piece chapter 1000#one piece drip

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Official Languages in Germany

German – deutsch – is the only language that is recognized nationwide as the official language. However, there are some regional and minority languages that are recognized at the regional or municipal level.

Niederdeutsch (Low German) is spoken by about 2 to 5 million people in Germany, the Netherlands and in the German diaspora. It is recognized as an official language in the states of Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein, Mecklenburg-West Pomerania, and in parts of Lower Saxony. In the latter state it is part of the German language lessons in school, while in the former states it is a choice among the elective subjects.

Danish is the officially recognized language of the autochtonous Danish minority living in Southern Schleswig, spoken by about 20,000 people. There are special Danish schools were lessons are held in Danish. If a German child wants to attend a Danish school in Schleswig-Holstein, the parents have to learn Danish as the parent-teacher conferences are held exclusively in Danish.

North Frisian belongs to the Anglo-Frisian group of germanic languages and is a recognized minority language in the district of North Frisia in Schleswig Holstein and on the island of Heligoland. It is spoken by less than 10,000 speakers and is listed as an endangered language.

Saterland Frisian is spoken by no more than 1500 to 2000 speakers in a small region of Lower Saxony. It is the last surviving dialect of the East Frisian language and officially recognized as a minority language in the municipality of Saterland. About 300 children learn the language in kindergarten and primary school.

Upper Sorbian is a West Slavonic language spoken by 20,000 to 25,000 people in the region of Upper Lusatia in the tri-border area of Saxony, Brandenburg and Poland. It is taught in schools in the region, there are regional newspapers and radio programs. Street signs are bilingual. The former minister president of Saxony, Stanislaw Tillich, speaks Upper Sorbian as one of his native languages.

Lower Sorbian is the other branch of the West Slavonic language in Germany. It is spoken in Lower Lusatia by 7000 speakers and is critically endangered. The state of Brandenburg actively promotes a revival of the language by offering lessons in school ans kindergarten, radio and TV broadcasts. Street signs are bilingual in places where there is a significant autochthonous minority of speakers of Lower Sorbian.

Romani is an officially recognized minority language in Germany. The most frequently spoken variant in Germany is Sinti-Romanes.

103 notes

·

View notes