#samonios

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Hope everyone had great All Souls Day, Samonios, Samhain or whatever else y’all observe this time of year! Have some sp00ky season altar p0rn

#traditional witchcraft#folk magic#magic#tradcraft#folklore#witch#magick#traditional craft#witchcraft#occult#Samhain#samonios#samanios#all souls day#all saints day#catholic#Catholicism#heresy#Gaulish#Gaul

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Janvier, premières bénédictions des salades sauvages

Se soigner avec les plantes, c’est aller à leur rencontre car elles sont directement à même de nous confier des enseignements, de nous partager leurs richesses physiologiques et leur expérience immersive de vie végétale biodynamique et bio dynamisée avec les autres règnes. Elles nous permettent d��engendrer des transitions importantes dans nos corps, de nos nombreux systèmes, de notre terrain,…

#conférence#Cycle des 8 initiations#Druide#druidesse#herboristerie initiatique#Médecines sacrées#Plantes des celtes#rituel#samhain#samonios

0 notes

Text

Halloween c’est COOL et c’est BLANC.

Ce sujet nécessitait une discussion franche à propos des éternels gâcheurs de fête.

Je voulais écrire cet article hier, mais peu importe.

Avec Halloween, nous avons eu le camp des rabat-joie, tout spécialement de droite, qui a trouvé judicieux de pester. À cette occasion, les Catholiques ont particulièrement voulu se rendre plus marginaux qu’ils ne le sont déjà.

« Je préfère l’amour ! »

Ces Chrétiens « pétris d’amour », avec leur inquisition et leurs bûchers, le sont tout autant que les antifas qui vous cassent la gueule en meute au nom de la tolérance universelle.

Quand ils saccageaient notre culture, ils ne procédaient pas avec des mots doux.

On s’en doute, rembarrer les gamins du voisinage en rageant comme un vieux con va contribuer à une affluence renouvelée à l’église. Qui ne voudrait pas fréquenter des saint-sulpiciens aigris qui refusent de donner des bonbons aux gosses, je vous pose la question ?

Quoi qu’ils en pensent, avec 3% de pratiquants réels, le christianisme est résiduel en France et il ne reviendra pas. Ils peuvent bouillir dans leur coin en maudissant leurs semblables, c’est la réalité et la réalité est tout ce qui nous importe tant que nous vivons sur cette terre.

Parmi les arguments récurrents contre cette fête, le caractère « américain » d’Halloween auquel est associé sa dimension « commerciale ». Cette festivité serait le symptôme de l’acculturation des Français sous l’effet de la domination du capitalisme américain et son caractère artificiel proviendrait de cette importation « verticale » imposée par le business transatlantique que les masses de consommateurs abrutis adopteraient sans réfléchir.

Tout cela est vrai, mais ça ne change rien.

Les Chrétiens sont les derniers à pouvoir l’ouvrir sur ce sujet, eux qui ont imposé leur religion désertique aux Européens par la coercition et la terreur intellectuelle.

Si cette religion est aussi massivement abandonnée par les peuples blancs, ce n’est pas uniquement en raison du matérialisme culturel, mais aussi parce qu’elle était une prison mentale qui reposait sur la terreur infernale agitée sous le nez des masses par des curés qui n’étaient pas les derniers à sauter leurs bonnes ou à piquer dans la caisse.

Et je ne parle pas de l’accueil chaleureux que la plupart des Catholiques réservent aux nègres d’Afrique dans leurs églises et qu’ils ne trouvent pas du tout « importés », ni inorganiques en Europe.

Il est un fait incontestable que les représentations de Halloween – d’ailleurs littéralement « Fête de tous les saints » en anglais – est autrement plus authentique et légitime chez nous que cette histoire de « saints » inspirés par Yahveh.

D’ailleurs, ce sont les Chrétiens qui se sont appropriés cette fête, pas l’inverse.

Wikipédia :

La fête catholique de la Toussaint tire son origine d’une commémoration de tous les martyrs, instituée à Rome en 613 par le pape Boniface IV ; à l’origine, elle était fêtée le 13 mai, jour anniversaire de la consécration chrétienne du Panthéon. Elle remplaçait la fête des Lemuria de la Rome antique célébrée à cette date pour conjurer les spectres malfaisants. Au IXe siècle, la fête fut étendue à « tous les saints » par le pape Grégoire IV et décalée au 1er novembre. Les historiens considèrent généralement que cette date a été choisie pour christianiser la fête de Samain.

C’est par un heureux effet boomerang que cette fête anglo-celtique de Grande-Bretagne est revenue en Europe continentale receltiser les Blancs, Gaulois en tête.

Pour les Celtes dont nous descendons, Halloween n’est rien d’autre que Samonios, le premier jour du premier mois de l’année celtique. Elle ouvre la saison sombre, qui dure 6 mois, et s’étend jusqu’à Beltaine, le 1er mai.

Wikipédia :

La plupart des historiens considèrent la fête folklorique païenne traditionnelle d’Halloween comme un héritage de Samain, une fête qui était célébrée au début de l’automne par les Celtes et constituait pour eux une sorte de fête du Nouvel An. Pendant la protohistoire celtique, existait une fête religieuse – Samain en Irlande, Samonios en Gaule –, qui se déroulait sous l’autorité des druides, pendant sept jours : le jour de Samain lui-même et trois jours avant et trois jours après. « C’est une fête de fermeture de l’année écoulée et d’ouverture de l’année à venir. Dans le calendrier celtique basé sur le cycle solaire, la date de Samain correspondait à la mi-temps d’une des quatre périodes allant d’un équinoxe et à un solstice, ou d’un solstice à un équinoxe. Par différence, ce sont les extrémités de ces périodes qui sont aujourd’hui l’occasion de célébrations dans les sociétés occidentales, et non leurs mi-temps : notre nouvel an actuel est fixé dix jours après le solstice d’hiver, Pâques est fêtée au moment de l’équinoxe de printemps, au solstice d’été a lieu la fête de la musique. Seul l’équinoxe d’automne n’étant pas fêté au profit de la mi-temps de la période qui le sépare du solstice d’hiver. Le temps de Samain est celui du Sidh (l’autre monde) brièvement confondu avec celui de l’humanité ». La nuit de Samain n’appartient ni à l’année qui se termine, ni à celle qui commence. La fête est une période close en dehors du temps. C’est la période où les barrières sont baissées et où, selon les croyances de l’époque, l’irréel côtoie le réel et où les hommes peuvent communiquer avec les gens de l’autre monde (Il s’agit là de démons ou des dieux des Tuatha Dé Danann). Lors de cette nuit de fermeture, les Gaulois avaient l’habitude de pratiquer une cérémonie afin de s’assurer que la nouvelle année à venir se déroulerait sereinement. Par tradition, ils éteignaient le feu de cheminée dans leur foyer puis se rassemblaient en cercle autour du feu sacré de l’autel, où le feu était aussi étouffé pour éviter l’intrusion d’esprits maléfiques dans le village. Après la cérémonie, chaque foyer recevait des braises encore chaudes pour rallumer le feu dans sa maison pour ainsi protéger la famille des dangers de l’année à venir. Les fêtes druidiques ont disparu d’Irlande au Ve siècle, avec l’arrivée d’une nouvelle religion, le christianisme.

Samonios est un moment hors du temps où le monde se dissout et se régénère. Il est pour cette raison associé à la mort, elle même un état transitoire de l’âme entre deux états stables, mais aussi entre deux mondes.

C’est pour cette raison que nous allons fleurir les tombes de nos morts à cette occasion : c’est le moment de l’année où nous pouvons en être physiquement le plus proches. Telle était la conception de nos druides.

Cela se perpétue dans le monde nord-européen en illuminant les tombes le premier novembre. Se souvenir des morts les empêchent de disparaître dans l’indifférenciation post-mortem.

C’est également un moment de danger. Les esprits chtoniens, du monde souterrain et obscur, peuvent surgir dans notre monde. D’où ces références aux monstres et à la mort. Loin d’être leur « célébration », c’est une épreuve pour s’en emparer et mieux les dominer.

C’est donc une fête qui repose sur des mécanismes psychologiques ancestraux extrêmement puissants qui réveillent la mémoire raciale des Blancs.

Les Catholiques – rejoints par quelques marxistes toujours obsédés par le fric des autres – qui viennent geindre à propos de la dimension « commerciale » de l’affaire oublient de dire que toutes les grandes fêtes chrétiennes étaient des excuses pour commercer.

Ce que l’on appelait les « foires » médiévales. Un continent inconnu de ces gens enfermés dans leurs clapiers résidentiels.

Wikipédia :

L’originalité des foires de Champagne est sans doute de former ainsi un cycle équilibré et continu tout au long de l’année de « foires chaudes » (en été) et « froides » (en hiver) ainsi que de foires principales et secondaires qui procure aux marchands une place d’échange presque permanente permettant non seulement d’échanger des marchandises mais aussi de régler leurs affaires financières.

2 au 15 janvier : foire « des Innocents » de Lagny-sur-Marne ;

mardi avant la mi-carême au dimanche de la Passion : foire de Bar-sur-Aube ;

semaine de la Passion : foire de Sézanne ;

mai : foire chaude de « Saint-Quiriace » de Provins ;

24 juin à la mi-juillet : foire « chaude » ou de la Saint-Jean à Troyes ;

septembre / octobre : foire froide de « Saint-Ayoul » à Provins16 ;

début novembre à la semaine avant Noël : foire « froide » ou de la « Saint-Remi » à Troyes.

L’Eglise est fortement représentée dans l’organisation de ces foires dans une société où la vie séculière est rythmée par le calendrier religieux. Les grandes fêtes et les pèlerinages coïncident souvent avec des foires et une fréquentation importante.

Quand la France était chrétienne, on ne laissait pas le commerce dénaturer notre culture !

S’il y a bien quelque chose qui a contribué à la ruine de l’âme des gens en France, c’est la conjonction de la casuistique médiévale et du rationalisme de l’Encyclopédie en plus du saupoudrage marxiste au 20ème siècle.

Ça nous a donné des coupeurs de cheveux en quatre à « principes », généralement dégarnis et myopes, cette sous-humanité dépourvue de toute énergie vitale et de toute mystique – oui, la casuistique est dépourvue de mystique, peu importe ce qu’elle bavarde – dont nos profs de gauche contemporains descendent en droite ligne.

Terrifie l’église de bergogliologie

Enfin, plus concrètement, en cette époque d’individualisme terminal où les Blancs sont incapables de faire quoi que ce soit ensemble, tout ce qui peut les pousser à sortir de leurs pavillons pour échanger toutes générations confondues est bénéfique. Les personnes âgées sont ravies de voir les gamins du quartier avec leurs petits costumes venir sonner à leurs portes. Les enfants voient autre chose que leurs écrans et se rendent compte qu’il y a des personnes qui vivent près de chez eux.

Enfin, ce qui ne gâche rien, par son caractère païen, elle est délicieusement haram, foncièrement anti-abrahamique, inconsciemment raciste.

youtube

Pour toutes ces raisons, je suis un partisan résolu de la Samonios contemporaine que l’on nomme « Halloween », à défaut d’une Samonios stricto sensu, peu importe ce que racontent les casse-pieds qui voudraient nous clouer devant leur Yeshoua communiste.

Démocratie Participative

1 note

·

View note

Text

E con Samonios arriva anche la luna nuova...

Quest’anno ho voluto celebrare a modo mio il capodanno celtico secondo l’antico Calendario di Coligny, pur senza osservare i riti religiosi o folcloristici derivanti dall’antica festività del paganesimo dei Celti. É il tempo in cui il buio ha il sopravvento sulla luce, degli ultimi dolci raccolti autunnali, dei semi che dimorano nella Terra in una sorta di letargo che li vedrà germogliare in…

#1 novembre#31 ottobre#autunno#buio#Calendario di Coligny#capodanno celtico#celti#consapevolezza#futuro#Halloween#impermanenza#introspezione#letargo#luce#luna nuova#monaco buddhista#novilunio#paganesimo#passato#pensa positivo#Perseide#presente#rinascita#riti#Samhain#Samonios#serenità#terra#think positive#tradizioni

1 note

·

View note

Text

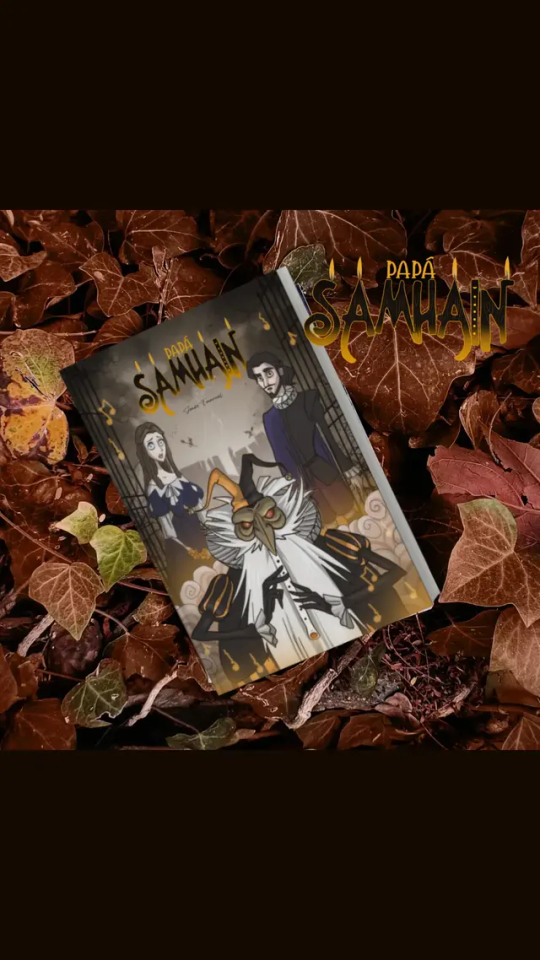

Papá Samhain 🕯️

Cuento de brujas ilustrado que narra un romance de ultratumba y los orígenes de Halloween 🎃

A la venta en Amazon y en Lulu. com

https://amzn.eu/d/1BtZFDP

Literatura de fantasía, misterio, romance y terror para niños y adultos 👻

#illustration#love#book#libros#papá samhain#samhain#samonio#halloween#terror#fantasia#leer#lectura#brujas#witches#october#conjuro#hechizo#sortilegio#brujeria#santeria#fairy tale#horror

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

October 2024 Witch Guide

New Moon: October 2nd

First Quarter: October 10th

Full moon: October 17th

Last Quarter: October 24th

Sabbats: Samhain- October 31st-November 1st

October Hunter's Moon

Also known as: Blood Moon, Drying Rice Moon, Falling leaf Moon, Freezing Moon, Harvest Moon, Migration Moon, Moon of the Changing Season, Sanguine Moon,, Shedding Moon, Ten Colds Moon, Winterfelleth & Windermanoth

Element: Air

Zodiac: Libra & Scorpio

Nature spirts: Frost Faeries & Plant Faeries

Deities: Apollo, Astarte, Belili, Cernunnos, Demeter, Hathor, Herne, Horned God, Ishtar, Lakshmi & Mercury

Animals: Elephant, jackal, ram, scorpion & stag

Birds: Crow, heron & robin

Trees: Acacia,apple, cypress & yew

Herbs: Angelica, burdock, catnip, pennyroyal, sweet Annie, thyme & uva ursi

Flowers: Apple blossom, calendula, cosmos & marigold

Scents: Apple blossom, cherry & strawberry

Stones: Amethyst, beryl, cat's eye, chrysoberyl, citrine, obsidian, opal, sapphire, tourmaline & turquoise

Colors: Black, blue, dark blue, blue-green & purple

Issues, intentions & powers: Cooperation, darkness, divination, healing & hope

Energy: Artistic works, creativity, harmony, inner cleansing, justice, karma, legal matters, mental stimulation, partnerships, reincarnation & uncovering mysteries or secrets

The Harvest Moon is the full Moon that occurs nearest to the autumnal equinox date (September 22, 2024). This means that either September or October’s full Moon may take on the name “Harvest Moon” instead of its traditional name. Similarly, the Hunter’s Moon is the first full Moon to follow the Harvest Moon, meaning it can occur in either October or November.

The Harvest Moon & the Hunter’s Moon are unique in that they are not directly related to this folklore or restricted to a single month. Instead, they are tied to an astronomical event: the autumnal equinox!

• October’s full Hunter Moon orbits closer to Earth than any of the other full Moons this year, making one of the four supermoons of 2024! As the Moon drifts over the horizon around sunset, it may appear larger & more orange—how perfect for the fall season!

It is believed that this name originates from the fact that it was a signal for hunters to prepare for the upcoming cold winter by going hunting. This is because animals were beginning to fatten up in preparation for the winter season. Moreover, since fields had recently been cleared out under the Harvest Moon, hunters could easily spot deer & other animals that had come out to search for remaining scraps. Additionally, foxes & wolves would also come out to prey on these animals.

Samhain

Known as: Ancestor's night, Feast of Apples, Feast of Sam-fuim, Feast of Souls, Feast of the Dead, Geimhreadh, Hallowmass, Martinmass, Old Hallowmass, Pagan New Year, Samana, Samhuinn, Samonios & Shadowfest

Season: Autumn

Element: Water

Symbols: Apples, bats, besom, black cats, cauldrons, ghosts, gourds, jack-o-lanterns, pumpkins, scarecrows & witches

Colors: Black, gold, orange, silver & white

Oils/Incense: Basil, cloves, copal, frankincense, gum mastic, heather, heliotrope, mint, myrrh & nutmeg

Animals: Bat, bear, boar, cat, cattle & dog

Stones: Amber, anatase, black calcite, black obsidian, black tourmaline, bras, carnelian, clear quartz, diamond, garnet, gold, granite, hematite, iron, jet, marble, onyx, pearl, pyrite, ruby, sandstone, sardonyx, smokey quartz, steel & tektite

Food: Apples, ale, beef, cider, corn, nuts, fruit, garlic, gourds, grains, hazelnuts, herbal teas, mushroom, nettle, nuts, pears, pomegranates, pork, poultry, pumpkin pie, sunflower seeds, thistle, turnips & wine (mulled)

Herbs/Plants: Acorn, allspice, angelica, besom, catnip, corn, deadly nightshades, dittany of Crete, fumitory, garlic, mandrake, mugwort, mullein, oak leaves, patchouli, reed, rosemary, rue, sage, straw, tarragon, thistle & wormwood

Flowers: Calendula, chrysanthemum & heather

Trees: Apple, beech, buckthorn, hazel, pine, locust, pomegranate, willow, witch hazel, yellow cedar & yew

Magical: Faeries

Goddesses: Al-Lat, Baba Yaga, Badb, Bast, Bebhionn, Bronach, Brunhilde, Cailleach, Carlin, Cassandra, Cerridwen, Copper Woman, Crobh Dearg, Devanyani, Dolya, Edda, Elli, Eris, Erishkigal, Fortuna, Frau Holde, Hecate, Hel, Mania, The Morrigan, Nemisis & Nicneven

Gods: Arawn, Baron Samede, Chronus,The Dagda, Dis, Hades, Nefertum, Osiris, Pluto, Woden & Xocatl

Spellwork: Divination, fire magick, night magick, shape-shifting, spirit calling & water magick

Issues, Intentions & Powers: Crossroads, darkness, death, divination, honor, introspection, otherworldly/underworld, release, visions & wisdom

Activities:

•Dedicate an altar to loved ones who have passed

• Boil a simmer pot to cleanse your space

• Have a silent dinner

• Light a candle for your loved ones & yourself

• Decorate your house and/or altar

• Release negative energy & cleanse yourself with a ritual bath

• Pull tarot cards to see what may be in store for you ahead

• Cleanse, clean & de-clutter your space

• Host or attend a bonfire

• Leave offerings for the S��dhe

• Journal & reflect on your accomplishments, challenges & everything you did this year

•Go on a nature walk

• Learn a new form of divination

• Have a bonfire with your friends and/or family

• Carve pumpkins, turnips or apples

• Express yourself creatively through art, music, ect

• Visit a cemetery & help clean off areas that need it or to visit a family member/ ancestor & leave an offering

• Hold a seance

• Bake spooky treats & bread as offerings

• Refresh your protection magicks, sigils & rituals

Samhain is about halfway between the autumnal equinox & winter solstice. It is one of the four Gaelic seasonal festivals along with Imbolc, Beltane, & Lughnasa. Historically it was widely observed throughout Ireland, Scotland, & the Isle of Man.

Samhain is believed to have Celtic pagan origins & some Neolithic passage tombs in Great Britain & Ireland are aligned with the sunrise at the time of Samhain. It is mentioned in the earliest Irish literature, from the 9th century & is associated with many important events in Irish mythology.

The early literature says great gatherings & feasts marked Samhain when the ancient burial mounds were open, which were seen as portals to the Otherworld. Some of the literature also associates Samhain with bonfires & sacrifices.

• According to Irish mythology, Samhain (like Beltane) was a time when the 'doorways' to the Otherworld opened, allowing supernatural beings and the souls of the dead to come into our world; while Beltane was a summer festival for the living, Samhain "was essentially a festival for the dead".

•The festival was not recorded in detail until the early modern era. It was when cattle were brought down from the summer pastures & livestock were slaughtered. Special bonfires were lit, which were deemed to have protective & cleansing powers.

At Samhain, the aos sí were appeased with offerings of food & drink to ensure the people & livestock survived the winter. The souls of dead kin were also thought to revisit their homes seeking hospitality & a place was set at the table for them during a meal. Divination was also a big part of the festival & often involved nuts & apples.

Mumming & guising were part of the festival from at least the early modern era, whereby people went door-to-door in costume, reciting verses in exchange for food. The costumes may have been a way of imitating & disguising oneself from the aos sí.

• In the late 19th century, John Rhys and James Frazer suggested it had been the "Celtic New Year", but that is disputed.

Some believe it is the time of The Goddess' mourning the death of The God until his rebirth at Yule. The Goddess' sadness can be seen in the shortening, darkening days & the arrival or cold weather.

Related festivals:

• Halloween( October 31st)-

In popular culture, the day has become a celebration of horror, being associated with the macabre and supernatural.

•One theory holds that many Halloween traditions were influenced by Celtic harvest festivals, particularly the Gaelic festival Samhain, which are believed to have pagan roots. Some go further & suggest that Samhain may have been Christianized as All Hallow's Day, along with its eve, by the early Church. Other academics believe Halloween began solely as a Christian holiday, being the vigil of All Hallow's Day.

Popular Halloween activities include trick-or-treating (or the related guising & ghouling), attending Halloween costume parties, carving pumpkins or turnips into jack-o'-lanterns, lighting bonfires, apple bobbing, divination games, playing pranks, visiting haunted attractions, telling scary stories, & watching horror or Halloween-themed films

• Day of the Dead(November 1st-2nd)-

el Día de Muertos or el Día de los Muertos

The multi-day holiday involves family & friends gathering to pay respects & to remember friends & family members who have died. These celebrations can take a humorous tone, as celebrants remember amusing events & anecdotes about the departed. It is widely observed in Mexico, where it largely developed, and is also observed in other places, especially by people of Mexican heritage.

•The observance falls during the Christian period of Allhallowtide.

Traditions connected with the holiday include honoring the deceased using calaveras & marigold flowers known as cempazúchitl, building home altars called ofrendas with the favorite foods & beverages of the departed & visiting graves with these items as gifts for the deceased.

The celebration is not solely focused on the dead, as it is also common to give gifts to friends such as candy sugar skulls, to share traditional pan de muerto with family & friends, & to write light-hearted & often irreverent verses in the form of mock epitaphs dedicated to living friends & acquaintances, a literary form known as calaveras literarias.

Some argue that there are Indigenous Mexican or ancient Aztec influences that account for the custom & it has become a way to remember those forebears of Mexican culture.

• All Saint's Day(November 1st)-

Also known as All Hallows' Day or the Feast of All Saints is a Christian solemnity celebrated in honour of all the saints of the Church, whether they are known or unknown.

Sources:

Farmersalmanac .com

Llewellyn's Complete Book of Correspondences by Sandra Kines

Wikipedia

A Witch's Book of Correspondences by Viktorija Briggs

Encyclopedia britannica

Llewellyn 2024 magical almanac Practical magic for everyday living

#samhain#witchblr#wiccablr#paganblr#witch community#witchcore#witchcraft#witches of tumblr#Autumn#fall#wheel of the year#hunters moon#sabbat#October#October 2024#witch guide#witch tips#grimoire#book of shadows#baby witch#beginner witch#traditional witchcraft#Greenwitchcrafts#witchy stuff#witchythings#witch friends#witch#witchessociety#full moon#spellwork

368 notes

·

View notes

Text

i've named the months for the known shores campaign, based on the celtic months and their meanings (which i elaborate on beneath the cut). sharing cuz i like 'em. 🥰

Winter: Bitters, Vespers, Rimes Spring: Squalls, Sporings, Glints Summer: Stables, Dibs, Haggles Fall: Chants, Plummets, Inks

the celtic months were kind of a mouthful as-is, but i wanted to retain some of their meanings, so here's that process! also with the runner-up names that i almost chose cuz some of them are fun.

Samonios (Oct/Nov) = "Seed-fall" = Plummets. (Runner-ups: Cascades, Ebbs.)

Dumannios (Nov/Dec) = "Darkest Depths" = Inks. (Runner-up: Slumbers. this was a hard choice and this might change actually lol)

Riuros (Dec/Jan) = "Cold-time" = Bitters. (Runner-ups: Barrens, Brisks.)

Anagantios (Jan/Feb) = "Stay-home time" = Vespers. (Runner-up: Hearths.)

Ogronios (Feb/Mar) = "Ice time" = Rimes. (Runner-up: Bites.)

Cutios (Mar/Apr) = "Windy time" = Squalls. (Runner-up: Wilds.)

Giamonios (Apr/May) = "Shoots-show" = Sporings. (Runner-up: Blooms.)

Simivisonios (May/Jun) = "Bright time" = Glints. (Runner-ups: Gleams, Blazes, Beams.)

Equos (Jun/Jul) = "Horse-time" = Stables. (Runner-ups: Herds, Colts, Roans.)

Elembiuos (Jul/Aug) = "Claim-time" = Dibs. (Runner-ups: Dues, Avowals.)

Edrinios (Aug/Sep) = "Arbitration-time" = Haggles. (Runner-ups: Huddles, Barters, Pacts.)

Cantios (Sep/Oct) = "Song-time" = Chants. (Runner-ups: Ballads, Anthems, Verses, Rhythms, Chimes. i actually like some of these more than Chants but there's an in-universe reason why i chose it!)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Celtic seasonal festivals - Part 4: Samhain

Part 1 ; Part 2 ; Part 3

[The following article contains references to human and child sacrifice; reader discretion is advised]

Hello, my dear readers! With today being the 1st of November, it's once again time for the next - and last - issue of our series about Celtic seasonal festivals. In this article, we will take a look at the origins and customs of Samhain, the most well-known and most influential of the Celtic seasonal festivals that the modern traditions of Halloween originated from.

As I mentioned in the first issue of this series, I already did an analysis on Samhain and how it morphed into Halloween previously, back when I was still active on Twitter. However, after finally making the decision to leave Twitter for good in the light of all recent developments, I thought it would be a shame if the content of these posts was lost to the public forever. Also, I was thinking about doing a revised version of my previous Samhain thread anyway, as I've been able to significantly expand my knowledge about Celtic culture and religion ever since starting this series, and I would like to put this new, broader perspective to use. There's no need to worry about anything being lost - I wrote this article based on my old scripts which I still have available, but rearranged and expanded it so it fits in with the basic structure of the other issues. So please, take your time to enjoy "From Samhain to Halloween - Enhanced Edition"! :-)

General/Etymology

Samhain, pronounced as SAH-wen (also known as Sauin in Manx Gaelic), is one of the Celtic threshold/"fire" festivals held on the night of October 31st to November 1st. It took place when the harvest was done and nature was dying, heralding the beginning of winter, the "dark season" of the year. Furthermore, while it was believed that the gateways to the Otherworld stood open during all threshold festivals, the veil separating the dwelling of supernatural beings from the world of men was supposed to be especially thin at Samhain, allowing spirits, fairies, and the ghosts of the deceased to cross over into the world of mortals.

It is said that out of the four Celtic seasonal festivals, Samhain was the most important one, with some scholars arguing that it was akin to the Celtic New Year. While this thesis can't be decisively proven, it does hold some relevance given that there are accounts of the Celts not counting their time by days, but by nights - since Samhain was considered the advent of the "dark half" of the year (=night), it might be possible that it indeed marked the beginning of the year cycle. Even the Calendar of Coligny, one of the few documents preserved from antiquity which was written by the Celts themselves, starts out with the month Samonios, which may be related to Samhain.

The lunisolar Coligny Calendar (depicted above) stands as proof of the Celts' ample knowledge of astronomy, enabling them to precisely define the dates of the festivals marking the change of seasons; despite being fragmented, it still remains the most important piece of evidence in reconstructing the Celtic year (Source)

Same as the other seasonal festivals, it's quite certain that Samhain has its origin as an agricultural festival: The date of November 1st exactly coincides with the time when herdsmen practicing transhumance (the movement of cattle herds in accordance with the year cycle) would bring their livestock down from the upland summer pastures into the valleys. This highlights the exceptional importance of livestock in Celtic agriculture, which is supported by both historical and mythological evidence (judging by the kitchen scraps from the Celtic oppidum Manching in Bavaria, 99.8% of the consumed meat stemmed from domestic animals; additionally, cows, bulls, and pigs feature prominently in many Celtic myths). Around the time of Samhain, farmers also had to decide which animals to slaughter, as not all of them could be fed through the winter. From this, the custom of holding a great feast on the butchered animals' flesh most likely developed, as a last opportunity for community before the harsh days of winter. Furthermore, the festivities probably served the purpose of people thanking the gods for bringing their cattle herds through the past year, as well as praying for their survival in the coming one.

The etymology of the term Samhain itself has been subject of much debate - some suggest that Samain/Samuin, the Old and Middle Irish term for the festival, might be composed of semo/sam ("summer") and fuin ("end"), but this never has been linguistically proven. Instead, a derivation from the Proto-Celtic samoni, meaning "assembly", seems to be a likely alternative, referring both to the gathering of people as well as their reunion with their ancestors - an assembly of the living and the dead, so to speak.

Ancient Customs and Rites

References to Samhain and its customs can be found in even the earliest Irish literature, the date being a popular setting for many legends and myths. In some tales, one can even find what might be a remnant of ancient sacrificial rites: For example, in the Lebor Gabála Érenn (known as "The Book of Invasions" in English), it's said the Nemedians had to give up two-thirds of their corn, milk, and their children to the demonic Formorians each Samhain (the latter in particular has been interpreted as an allusion to child sacrifice). In this context, the Formorians themselves - which are usually identified as the chaotic, destructive powers of nature - might act as substitutes for ancient gods. It's highly likely that the deities these sacrifices were dedicated to were chthonic in nature, as chthonic gods were not only associated with death and the underworld, but also believed to have control over growth and fertility. With the harvesting period having to an end, the Ancient Celts probably felt obligated to thank the gods of the earth for their bounty, offering them the "best fruits" of the year to invoke their blessing in the next one.

We don't know exactly which gods these sacrifices were meant for, but we do have some possible candidates: In his De bello Gallico, Julius Caesar reports that the Gauls worship a "night god" as their progenitor, comparing his role to the Roman Dis Pater, the lord of the underworld. Some scholars have chosen to interpret this god as Cernunnos, the Celtic god bearing deer antlers on his head and whose name means "the Horned One" (derived from karnon, Gaulish for "horn"/"antler"). Due to frequently being depicted as a "Lord of Animals" surrounded by stags, dogs, bulls, and a horned serpent, he is assumed to be a deity of nature and wilderness. On the other hand, his attributes also include a bag of coins (sometimes grain) and a cornucopia, as well as a torque in one hand, a very popular accessory in Celtic culture which was usually worn around the neck and symbolized power. This suggests that Cernunnos was also responsible for agriculture, being the master over every person's wealth in the form of crop yields. An association of chthonic deities with the growing of crops was very common in ancient times, so there is indeed a possibility that the "night god" mentioned by Caesar and Cernunnos are one and the same entity.

This depiction on the Gundestrup cauldron, a marvelous piece of silver workmanship presumably of Celtic and Thracian origin, shows Cernunnos surrounded by animals such as a stag, a bull, a wolf, and a dog, as well as leaves and buds; the antlered god is sitting cross-legged in the middle of the scene, holding a horned snake in his left hand and a torque in the right, in addition to the one he wears around his neck (Source)

Aside from this, there is also a Celtic god named Sucellus who appears to have possessed similar properties. A very popular deity in Gallo-Roman culture, he is usually portrayed as a bearded, middle-aged man with a wolf-skin as a cape, holding a long-handled hammer or a mallet in one hand (sometimes interpreted as a beer barrel on a pole), and an olla, a type of ancient ceramic pot used for cooking, in the other (it's interesting to note that in Ancient Rome, ollae were also used as funerary urns and for the purpose of animal sacrifices). Occasionally, he is depicted alongside the goddess Nantosuelta, who is believed to be his consort and a deity of fertility, the domestic sphere as well as the dead, her attributes including a miniature house on a pole (variously interpreted as a dovecote/temple model) and ravens. There is a Latin inscription which directly links Sucellus to Silvanus, the Roman god who acted as the lord over woods and plantations, as well as the protector of cattle herds and field boundaries. Some scholars suggested that his role as the guardian of borders might have been a little more ambiguous, identifying him as a chthonic deity who was also tasked with maintaining the border between the underworld and the world of the living. If this is true, Sucellus simply might have been a local variant of Cernunnos, or perhaps an epithet or aspect of one and the same deity. Either way, with our knowledge of ancient Celtic religion being so fragmented, it's difficult to reconstruct.

Still, it appears as though remnants of this god of death and fertility have survived in other Celtic countries: From Irish mythology, we know of Dagda, a major god said to possess power over life and death, the weather, crops, as well as the seasons. Also called "The Dagda", he is usually described as a bearded, large man wielding a magic staff (in some versions a club/mace) with two ends, one of which bestows life while the other kills everything it touches. Furthermore, he possesses a magic cauldron which never runs empty is able to sate every person, in addition to an enchanted harp which can control emotions and bring about the change of seasons. His wife is said to be Morrígan, the fierce goddess of fate, death, and war who turns into a raven on the battlefield. Several Irish tribes traced back their ancestry to Dagda, which is a characteristic that also applies to Donn, who is believed to originally have been an aspect of Dagda. Assumed to be a god of the dead, Donn's last request to his descendants was that they should come to his abode after they die, and to the Irish, "to go to the House of Donn" was synonymous with dying. Donn's dwelling was known as Tech Duinn (translating to "house of Donn"), said to be the place where the souls of the death gather and commonly identified with Bull Rock, a small island off the coast of the Beara Peninsula in the far southwest of Ireland. This would align with the traditional Irish belief that the souls of the death departed westwards over the sea with the setting sun, and the unique shape of Bull Rock resembling a dolmen or a passage tomb might have contributed to people thinking of it as a gateway to the Otherworld, the destination of the final journey of the deceased before they were reincarnated.

However, there is yet another Irish god who was specifically associated with rituals at Samhain: Crom Cruach. The etymology of the name has been debated, with Crom (Irish cromm) usually being translated as "bent/crooked", and Cruach (Irish crúach) meaning "heap", "mound", or "stack", denoting a pile of things like crops, gathered goods, booty, etc., but also the bodies of slaughtered warriors (possibly referring to a mound of sacrificial offerings). According to the Book of Leinster from the 12th century, the god's golden idol stood on the plain Magh Slécht (translated as "plain of prostrations" or "plain of the monument"), surrounded by a circle of twelve smaller bronze figures. The latter might hint at his function as solar deity, which would make him similar to Aed, the Irish god of the underworld who is also suspected to have been a sun god (although it may seem confusing why a chthonic deity should have a connection to the sun, it should be kept in mind that the sun in this context is tantamount to the wheel of the year, and thus, the natural cycle). In times past, the people of Ireland supposedly sacrificed a third of their firstborn children to Crom Cruach in exchange for a bountiful harvest in the next year, a ritual which always took place at Samhain. The Irish High King Tigernmas himself was known to kill a firstborn child in honor of Crom Cruach every Samhain eve, by smashing the child's head against the stone idol. However, one Samhain night, Tigernmas found his own demise on Magh Slécht alongside three fourths of the men of Ireland, all of them dying mysteriously while worshiping Crom Cruach. Apparently, word of these horrific rites even reached Ancient Greece, with Greek authors identifying Crom Cruach as the child-eating titan Cronus, and Ireland as the far-away island close to Britain where Zeus had banished him to. It was said by Plutarch that Cronus is the "sovereign lord of these islands (...) [who] sleeps within a deep cave resting on a rock which looks like gold." He also noted that "there are many deities about [Cronus] as satellites and attendants." Aside from the obvious resemblances to Crom Cruach's idol, a commonality between Crom and Cronus is that both of them are associated with the harvest - however, it can't be decisively said if one influenced the other, and whether Crom Cruach was a native god or Greek adaptation.

One might wonder why worshiping nature deities required such gruesome rituals, and why there seems to be such an inseparable connection between fertility and death in Celtic culture. In the end, we have to remember that the Celts lived in a time when survival was largely dependent on nature's whims, and a single period of foul weather could destroy an entire harvest. Cultivating a harsh region like Central Europe undoubtedly taught the Celts that nature is just as brutal as it is bountiful, and that reaping yields from the earth always came with a price to pay - thus, appeasing nature deities and winning their favor was most likely seen as particularly important. In addition, we shouldn't forget that the Celtic people probably viewed death quite differently than we do: It seems that to them, death was merely a transition from one existence to another, and much like nature and the year with its twelve months, life was seen as a continuous, never-ending cycle. The Celtic belief in reincarnation has been cited by ancient authors such as Caesar, but transformation and rebirth as animals or other objects is also documented in various myths from Celtic countries, such as the Irish tale Tochmarc Étaíne. And just like every new life begins in the darkness of the womb, Samhain may have been viewed as the time of winter and the advent of darkness, when the seeds from which new life would sprout were already lying in the ground.

Unfortunately, it's difficult to piece together the exact rituals and procedure of the ancient festival, due to all sources referring to it having been written long after antiquity by Christian monks. However, it's evident remnants of these ancient customs lasted until medieval times: In several texts, there are accounts of gatherings during the time of Samhain which would last multiple days, where nobles and ollams (masters of a specific trade who held influential positions, particularly bards and poets) would come together in peace. For example, in the Irish tale Serglige Con Culainn, the feast the clan of the Ulaid held at Samhain is said to have lasted a week, beginning three days before Samhain and ending three days afterwards. Another story known Echtra Cormaic mentions the so-called "Feast of Tara" hosted every seven years by the Irish High King, during which the lords of Ireland would meet, pass new laws, and make political decisions. All nobles were obliged to adhere to the laws enacted during this period - not doing so would result in banishment. In addition, these gatherings also had a more jovial side, involving feasting, drinking, and contests. The main course of these feasts was most likely the meat of the cattle butchered on Samhain, part of which the guests would sacrifice to the gods while consuming the rest themselves. Aside from conveying their gratitude, this "shared meal" was also meant to win the gods' favor, ensuring that both the people and their livestock made it through the winter.

However, it appears Samhain may not have been a time of rejoicing for every ruler: According to legend, the two Irish kings Diarmait mac Cerbaill and Muirchertach mac Ercae both die a threefold death on Samhain by wounding, burning, and drowning. Interestingly, this description almost exactly mirrors the three kinds of sacrifices the Gallic gods Esus, Taranis, and Teutates allegedly required: Humans that were to be sacrificed to Esus would be hung from a tree and flogged to death, victims dedicated to Taranis would be burned, and sacrifices to Teutates were to be drowned in a tub of water. Presuming that these accounts are a remnant of ritual killings, they most likely took place when a king was deemed unworthy due to his reign being unfruitful, which was considered a sign of offense by the gods (it's been hypothesized that the inauguration of an Irish king involved a symbolic marriage to the goddess of the land, meaning that any bad harvest or other misfortunes would be directly blamed onto him). While there is no decisive proof to confirm this thesis, some bodies found in Irish bogs seem to belong to nobles who have been ritually killed in a similar manner, a few of them even around the time of Samhain.

In general, Samhain was seen as a time when all debts would have to be settled, and everyone who owed something to another person would make sure to repay them before this date. Also, there are accounts that Samhain marked the official end of the harvesting period, and any crops that had not been gathered until then would be left in the field. In fact, it was even considered dangerous to consume anything harvested after Samhain, be it crops or wild fruits, as it was believed that a spirit known as the Púca had claimed it as its own by spitting on it (or, according to some versions, urinating on it), thus making the yields inedible for humans.

Much like on Beltane, bonfire customs were an important part of Samhain. As a sign that the light half of the year was over, all people would extinguish the hearth fires of their homes and come to gather around large common fires. These bonfires would be ignited by Celtic druids on hilltops, such as the Hill of Tlachtga, today known as the "Hill of Ward". Traditionally, only certain types of wood like oak would be used for the bonfire (according to Pliny the Elder, oaks were sacred trees among ancient Celtic druids), and it was custom to light it by the means of friction, creating sparks and thus kindling a need-fire. The dousing of household fires and subsequent ignition of common fires might represent the dying of light and its rebirth, and one can surmise that the bonfires were meant to invoke the powers of growth that would bring back life to the world in the coming spring. In addition, the fires as well as their ashes and smoke were believed to possess cleansing properties, and there were a lot of rituals meant to ensure that people purified themselves of harmful influences during this time of transition. In some places, two bonfires would be erected side by side, and in a custom very similar to Beltane, people would run between them as a purification ritual, sometimes with their cattle in tow. Meanwhile, in the Scottish region of Moray, young boys would go out to collect firewood from every house in the community, and once the bonfire was lit, they would lie down as close to it as possible to let the smoke blow over them. When the flames died down, the boys would scatter the ashes, vying among themselves for who was allowed to scatter the most. Sometimes, people would even use the ashes to blacken their faces, which was meant to grant them protection from harmful magic. It was also custom to cast the bones of slaughtered cattle into the fire, which was probably meant as a sacrifice to the gods. Once the celebrations were over, everyone would take an ember of the sacred fire home with them, and walking sunwise around houses and fields while carrying burning torches of fir or turf was a common ritual of protection. Following this, every family would solemnly rekindle their own hearth with the sacred flame - yet another ritual symbolizing the end of the old and beginning of the new.

Since Samhain was a liminal time, bonfires were lit which were believed to have cleansing and renewing properties, facilitating a smooth transition into the new half of the year; the Hill of Tlachtga in the Irish County Meath supposedly was the site of a Samhain bonfire and great gathering (Source)

Reigniting the household's fire was not the only duty for every family, however: Since the souls of the dead returned from the Otherworld on Samhain, they would visit their kin's homes, seeking warmth and hospitality. As such, people were obliged to set an additional chair at their dinner table, preparing a special dish of porridge for the deceased. Sometimes, a bowl of fresh water would also be placed near the hearth to welcome them. Additionally, the windows would be left open or the doors unbolted, so the spirits of the dead could come in and partake of the meal. Thus, the whole family, living and dead, would be reunited and dine together - a custom which feels very reminiscent of the Mexican Día de los Muertos.

Alongside the spirits of the deceased, the Aos Sí - spirits and fairies from Irish folklore - were said to emerge from the gates of the Otherworld and roam the land at Samhain night. Judging by the offerings the Ancient Celts left in natural caves and near peculiar rock formations in Central Europe, it appears these places were believed to be portals leading to the Otherworld. In addition, it seems the same was true for the entrance of graves: Legend has it that the Cave of Cruachan, an ancient Irish burial mound belonging to the archaeological complex of Rathcroghan in the County Roscommon, was a gateway to the Otherworld from which hordes of monstrous beings would emerge at Samhain. There are accounts of a flock of red birds causing every plant to wither with their breath, a herd of pigs possessing similar powers of decay, and finally, the Morrígan herself, who would appear riding a chariot draw by a one-legged chestnut horse.

Although these descriptions sound terrifying, it should be mentioned that in ancient times, there might not have been such a clear distinction between good and evil spirits. Just like nature has its live-giving and destructive sides, spirits were believed to be able to bestow both luck and misfortune, and people would take care to appease them so as not to incite their ire. As such, many measures were taken to propitiate the Aos Sí, like placing offerings of food and drink outside for them, leaving a portion of the crops in the ground for them, and pouring libations into the sea. (Considering some scholars theorize that the Aos Sí are remnants of pagan deities, these customs may have originated from ancient sacrificial rites.)

Nevertheless, people were generally advised to stay home during Samhain night, as fairies were notorious for playing tricks and restless souls might be out to take vengeance on those who wronged them. Dusk and midnight in particular were very precarious times, and people would stay away from waterways and the west side of houses since they believed fairies frequented these routes. Whoever still dared to venture out into the darkness would take special care to protect themselves from any mischievous spirits by wearing their clothes inside-out, or carrying salt or a piece of iron with them. However, if one of your relatives or friends did happen to have been taken by fairies the previous year, there was a way to free them: If you came across some fairies on Samhain night - which usually announced themselves by playing music while wandering from one fairy hill to another - you would have to throw dust from under your feet at them, and they would be compelled to release any person they had taken captive a year and a day ago. When tossing any kind of water out of the window at Samhain, it was also advised you should shout "beware!" (seachain) or "water towards you!" (chughaibh an t-uisce) - after all, you never knew when any spirits might be potentially passing by your house, and unintentionally upsetting them would mean great misfortune.

In addition, people would take precautions to keep any malevolent spirits away from their home: A dead ember from the hearth fire or a piece of iron would be placed under every child's bed, to protect them from being abducted by the fairies. Alternatively, a mixture of salt and oatmeal would be daubed onto their foreheads. In southern Ireland, a so-called "parshell", a woven cross made from sticks and straw similar to the Brigid's cross, was a popular Samhain talisman. If hung over the inside of the doorway or in the barn, it was believed to ward off bad luck, illness, and sorcery, as well as grant protection to the livestock. Its effect would last until the next Samhain, when it had to be replaced by a new one.

Still, it might have been possible that you found a procession of eerie figures knocking at your door - not any fairies or spirits, but people dressed in costumes imitating them. It's believed that the tradition of mumming and guising originates from Celtic priests/druids impersonating the souls of the dead or the Aos Sí, going from house reciting verses and songs in exchange for food offerings, fuel for the bonfires, or other supplies for a Samhain feast. Since they acted as representatives of the spirits, everyone was obliged to make a small donation - otherwise, who knew what misfortunes might befall you. While the disguise was clearly meant to show their status as deputies of the Aos Sí, it also served the function of protecting the wearer from any spirits intending to cause them harm. Disguising oneself was one of the only safe ways to go out at Samhain night, as the spirits would be unable to recognize you - maybe even mistake you for one of their own - and thus leave you alone.

At Samhain, people took great care not to offend any spirits or Aos Sí, putting out offerings to appease them; people would prepare an extra seat and meal at the dinner table for their dead relatives, leaving the door or windows open to let them in, while porridge plates dedicated to the Aos Sí would be placed into a small pit in the ground (Source)

Interestingly, this was not the only almsgiving custom on Samhain: With lots of solemnity, every family would bake an oatmeal cake, which would then be offered to a complete stranger. It's assumed that this generosity was meant to ensure the donors themselves would have plenty of food in the future, being reminiscent of some Imbolc customs where the scraps of a feast were given to the poor.

Since the borders between the magical and the mortal world were thinned, Samhain was also believed to be a particularly good time for divination. As during all seasonal festivals, the weather was of particular interest to the diviners, with the wind at midnight hinting at the weather of the coming winter. If visible, the moon was also used as an indicator: If the skies were clear and the moon wasn't obscured by any clouds, it meant good weather, while a clouded moon meant rain, the amount depending on how many clouds there were. If there were clouds drifting quickly past the moon, it meant storms were coming in the following season. Some divination customs also involved the bonfires, such as a tradition practiced in the Scottish Ochtertyre, northern Wales, and Brittany where multiple rings of stones would be laid around the fire on top a layer of ash, each of them representing a person. Afterwards, everyone would pick up a torch and run around the circles merrily, and when any stones were found to be displaced in the following morning, it was said the respective person would die the coming year. (It has been suggested that this developed from a more ancient ritual of selecting a human sacrifice which would then be burned.)

During more private gatherings, seasonal fruits like apples and hazelnuts would often be used in divination rituals. These fruits held great significance in Celtic mythology: Apples symbolized fertility, immortality, and the Otherworld, while hazelnuts were associated with divine wisdom. Apple bobbing was a very popular game, where young unmarried people would try to catch an apple floating in the water with just their teeth - the first person to succeed would be the first to marry. Alternatively, a small wooden rod would be hung from the ceiling horizontally, an apple at one end and a candle at the other. The participants would take turns trying to catch the apple hanging at head height with their teeth, all the while the rod was spun around for increased difficulty. Aside from this, people would peel apples in one long strip, toss the peel over their shoulder, and allegedly, the peel's shape formed the first letter of their future spouse. There was also the custom of roasting two hazelnuts next to a fire, with one representing the person roasting them and the other their beloved. When the nuts roasted quietly near the fire, it was the sign of a good match, but the two nuts jumping away from the heat signaled the relationship was not meant to last.

In addition, people would prepare food with hidden items inside it: In pre-modern times, this was usually done with cakes or barmbrack (a type of yeast bread with raisins), but champ (a dish made of mashed potatoes, scallions, butter, and milk), colcannon (a dish of mashed potatoes with cabbage), or various kinds of pudding (such as cranachan or sowans) were also used for this purpose. The dishes were served to the guests at random, and the item they found was supposed to give a hint at their future - for example, a ring stood for marriage and a coin for wealth. Furthermore, baking a salty oatmeal cake, eating three bites of it, and then silently going to bed without drinking anything was said to result in a dream where one's future spouse would offer you a drink to quench your thirst. Even children took part in the divination games, chasing birds like ravens and divining things based on how many there were and which direction they were flying in.

St. Martin's Day, the banishment of Crom Cruach and the history of the jack o'lantern

Although the festival of Samhain may have been widespread in Celtic Europe once, the introduction of Christianity brought an end to this tradition. Nevertheless, it seems like some distant memory of it still remained in the people's minds: In the Stuttgarter Psalter, a richly illuminated medieval manuscript from the 9th century, there is a depiction of a horned figure that looks strikingly similar to Cernunnos, sitting cross-legged with a ram-headed serpent wound around his left arm. This portrayal of Cernunnos is part of the "Descent into the Limbo" scene, thus connecting him to the underworld (in Christian theology, the Limbo is the place where the souls of those go who did not disregard their belief in God, but still were unable to attain salvation by Christ during their lifetime). This might be an echo of Cernunnos' presumed status as a chthonic deity, or the association might be due to him being a horned god - either way, both attributes most likely would've contributed to him being considered a devil figure.

Despite this, some of the old pagan traditions still survived, albeit under a Christian guise: In many regions across Europe, people celebrate the Christian holiday of St. Martin's Day on November 11th, just a few days after the date of Samhain. One of the usual customs was to slaughter an animal, most commonly a goose, rooster, or sheep, and sprinkling its blood on the house's threshold for protection. The meat was then offered to St. Martin and eaten as part of a feast. This carries obvious resemblances to the custom of slaughtering livestock at the beginning of winter that Samhain originated from, and it has been suggested that St. Martin acts as a substitute for one or multiple gods.

In the Celtic regions of the British Isles, the custom of mumming and guising on the night of October 31st also persisted. However, it was no longer Celtic druids, but youths who would dress themselves up and go around the neighborhood, carrying turnip lanterns to light their way. In Scotland, young man would don masks, veils, paint their faces or blacken them with bonfire ashes, going house-to-house and demanding hospitality under the threat of committing mischief. If any house owner was so stingy as to not donate anything, the youths would have their fun playing pranks on them, much like the mischievous fairies of yore. Meanwhile, in Ireland, farmers would knock on the doors with sticks and ask for food on behalf of St. Colm Cille. In the south of the country, the procession also featured a Láir Bhán ("white mare"), a hobby horse which was impersonated by a man covered by a white sheet and carrying a decorated horse skull. Led by the Láir Bhán, a group of youths would go from farm to farm, announcing their arrival by blowing cow horns. Every farmer was expected to donate some food - if they did, the "Muck Olla" would bestow good fortune onto them, but if they didn't, they would suffer from bad luck.

The latter seems reminiscent of the Welsh folk belief that a white horse is a harbinger of death as well as the Irish legends about the horseman Donn, who is most likely inspired by the eponymous death god. In the County Limerick, a phantom horseman named Donn Fírenne was said to have his dwelling in the sacred hill of Cnoc Fírenne, riding a white horse whenever he roamed the land. On the western coast of the County Clare, people told tales about Donn na Duimhche, also called Donn Dumhach ("Donn of the Dunes"), a horseman whom you would often encounter at night. Later on, "Donn" simply became a title for any kind of Otherworld lord from folklore.

At the same time, we see a clear desire of the Irish people to distance themselves from some of the more gruesome rituals of the pagan Celtic religion: In the 9th century-hagiography Tripartite Life of Saint Patrick, Crom Cruach, the god who allegedly demanded the sacrifice of firstborn children in exchange for fertility, appears as Cenn Cruach (cenn meaning "head" or "chief" in Irish). When St. Patrick approaches his cult image made of gold and silver surrounded by twelve bronze figurines, he raises his crozier high, burning a mark into the central figure and toppling it face down, while the twelve smaller idols sink into the ground. The "demon" inhabiting the image then comes forth, with Patrick cursing him and banishing him to Hell. According to other versions, St. Patrick destroyed Crom's idol with a sledgehammer - either way, the god's bloody cult was put to an end by the Christian saint.

According to legend, it was St. Patrick who defeated Crom Cruach, knocking down his idol on the plain of Magh Slécht (top; Source); interestingly, a broken stone engraved with La Téne motifs has been found near the historic site (bottom; Source)

Interestingly, there is a large, carved stone which was found near the town of Killycluggin in the County Cavan, Ireland. It was discovered in close proximity to a Bronze Age stone circle, suggesting it may have originally stood at the center of it. Upon excavation, the stone was broken into several pieces, but one could still make out the swirls typical of the Celtic La Tène period art covering it. What could be restored of the roughly cone-shaped stone was brought to the Cavan County Museum, though a replica can be seen near the discovery site. According to estimations, the original monument was at least 1.8 meters/6 feet high, and there were four additional, rectangular panels at the base of the stone, each measuring 90cm in width and thus giving it a total circumference of 3.6 meters/12 feet. It's possible that the stone was always in the round shape of a head (the Celts saw the head as the seat of the human soul, leading to the development of their infamous head cult), although there are several hints that it might have been an anthropomorphic statue once. It has been suggested that the engravings at the sides represent the edge of a garment, and the furrows at the top resemble the depiction of hair in other La Tène-period sculptures. Moreover, the stone as a whole leans obliquely from the vertical, and if one imagines it as the head of a bigger statue, it would mean that the figure stood slightly bent over as well - perhaps this is what earned Crom Cruach his title of "crooked one of the hill". The original image may or may not have been gilded, although it wouldn't be unusual if it was: Among Celtic artisans, gold was a very popular metal for jewelry and other precious items, and we do know of a golden cult tree found in the Oppidum of Manching in Bavaria which was probably used for sacred purposes. Adding to the evidence, Killycluggin not only lies near the historic plain Magh Slécht, but the region has also several associations with St. Patrick. There is even a poem from the Book of McGovern written in the 14th century stating that the women of Kilnavert - a town close to Killycluggin - would tremble in fear when passing by the stone of Crom, which was situated at the side of the road. The local tradition identifies the Killycluggin Stone as the Crom stone, though it is unclear whether Crom Cruach or Crom Dubh (a folkloric figure based on Crom Cruach) is meant by this. Still, considering all of this, one might wonder if there is some kernel of truth behind the bone-chilling legends.

Nevertheless, the Christianization of Ireland was a peaceful process, and the pagan traditions slowly assimilated with the new Christian faith. Still, for some reason, the Christian holiday of All Hallow's Day was moved to November 1st during the course of the 8th century, the celebrations beginning one day before with a vigil held on All Hallow's Eve. In the Catholic Church, All Hallow's Day was a day to commemorate all saints and martyrs, usually taking place some time in spring. In 4th century Edessa, it was held on May 13th, the traditional date of Lemuria, an ancient Roman festival dedicated to honoring the dead. After Pope Gregory III had dedicated an oratory to all apostles, saints, and martyrs in the St. Peter's Basilica, however, November 1st gradually became the new accepted date. Theories about the reason for this vary, but it might be possible that the people of Celtic and Germanic regions found it to be more reconcilable with their former pagan beliefs, as the beginning of winter was when they held their festival in honor of the dead.

Whether this is true remains up for debate, but either way, the old pagan customs proved hard to kill, and the Irish people even made up their own folkloric figure associated with the holiday who was anything but a saint: the infamous Jack O'Lantern. Also known as Stingy Jack, he was a good-for-nothing scallywag earning his daily money by swindling and fraud, only to spend most of it on the joys of alcohol.

The most well-known version of his story goes like this: "One evening on All Hallow's Eve, while the drunken Jack was sitting in a pub, the devil suddenly appeared next to him, beckoning him to come with him. Not wanting to go to Hell, Jack quickly devised a trick: In the face of his impending death, he begged the devil to buy him one last drink, which he agreed to. However, after the devil had transformed into a sixpence piece because he had no money on him, Jack quickly stuffed it into his bag, where he kept a small silver cross. Because the devil was unable to get out in turn, he struck a bargain with Jack to leave him alone for ten more years in exchange for his freedom.

After ten years had passed, the devil once again returned on All Hallow's Eve to claim Jack's soul, only for the latter to ask him yet another favor: He begged him to get him an apple as a last meal. The devil agreed and climbed an apple tree to pluck the desired fruit, but Jack was quick to carve a cross into the bark with his knife. Being stuck on the tree, the devil made yet another deal with Jack, this time relenting to leave his soul alone for all eternity.

As Jack died many years later, he went to the gates of Heaven, asking for entry. However, since he had been anything but a good man during his life, he was denied and sent away. But when he arrived at Hell, the devil wouldn't let him in either, as he had given his word to never take Jack's soul. Thus, he directed Jack back where he came from - but since he took pity on him for having to go alone through the dark, cold, and windy night, he gave him a burning piece of coal straight from the fires of Hell, which Jack put into a hollow turnip he had taken along as a provision. Henceforth, barred from both Heaven and Hell, his doomed soul wandered through the night of All Hallow's Eve, and shall do so until the day of the Last Judgement..."

One of the most famous Halloween legends tells of Jack O'Lantern, also known as Stingy Jack or Jack the Smith, a cunning swindler whose evil deeds earn him an existence of eternal restlessness, left with only a turnip lantern to illuminate his way through darkness (Source)

It's remarkable that Jack's Limbo-like existence, banned from Heaven and Hell alike, provides an interesting parallel with Cernunnos' depiction as the lord of the Limbo in the Stuttgart Psalter. Furthermore, this tale pretty much invented the folkloric background behind the tradition of hollowing out and carving ghastly faces into turnips, putting a candlelight into them and placing them on the windowsills as protection. It was said that the lanterns represented spirits or supernatural beings, and they were believed to ward off the devil and any other malevolent spirits.

Still, it's noticeable that the turnip lanterns not only appeared in Ireland, but also the Scottish Highlands, the Isle of Manx, and parts of northern and western England - in short, all Gaelic-speaking and former Celtic regions of the British Isles. Meanwhile, they weren't widespread in England until the 20th century, which might suggest they have a deeper-rooted, pan-Celtic origin. Although it has been noted that the Irish have been carving turnips and other root vegetables for centuries, the cultivated form of the turnip as we know it was only brought to Great Britain in the 18th century. There are, however, accounts of lanterns made out of beets, a vegetable which did exist back in antiquity (beta, the ancient Latin name for the beetroot, is believed to be of Celtic origin as well). From a historic perspective, celery roots would make for another plausible candidate: Celeriac was a plant that was known since ancient times, being mentioned as far back as the Iliad and Odyssey, and was used for a variety of medical and religious purposes. In fact, celery even had associations with chthonic deities and the cult of the dead in Greek religion, with the leaves being used to make garlands for the deceased out of them. As for the Celts, archaeobotanical research conducted near the Heuneburg in Bavaria, a Celtic settlement from the Hallstatt period, proves that celeriac was cultivated and consumed by the Celts. So, perhaps what might have been a celery root lantern in antiquity became a turnip lantern in the 19th century.

However, the jack o'lanterns, as the carved turnips were called, would still undergo one major transformation: During the 19th century, droves of people emigrated from Scotland and Ireland to America, a process which was fueled even further by the Great Famine from 1845 to 1852. Everywhere they went, the Irish and Scottish people brought their traditions with them, and thus, the festival of All Hallow's Eve spread to the American continent. When they came to America, however, the emigrants discovered that the pumpkins growing abundantly there were much easier to carve than turnips, leading to the traditional turnip lanterns being replaced by pumpkin ones. Over time, they would become one of the most recognizable symbols of All Hallow's Eve, which eventually became known as Halloween.

Modern traditions and Halloween

Although the celebration of Halloween as we know it today is largely derived from Irish and Scottish customs, there are many local variants of Samhain across the British Isles. On the Isle of Man, the festival on the night of October 31st is known as Hop-tu-Naa and believed to be one of the oldest Manx traditions, continuing until today. The name stems from one of the various silly rhymes sung by children during the festival, who dress up and go from house to house asking for sweets. To light their way, they carry carved turnip lanterns with them, with the decorative motifs varying depending on the locality. Furthermore, there are various cultural events taking place across the Isle of Man during this occasion, including competitions in artistic turnip carving, the singing of folk songs, and the so-called Hop-tu-Naa dance, a traditional procession dance for pairs. In the past, there were also various divination customs associated with Hop-tu-Naa, primarily centered around death and marriage just like the Irish ones: Before retiring for the night, people would rake the hearth's ashes smooth, and if there were footprints pointing to the inside of the house, it heralded a future birth - if, however, the footprints led out the door, it meant that someone would die. Girls and young women would come together to bake a Soddag Valloo ("Dumb Cake") in silence, preparing the ingredients including flour, eggs, eggshells, soot, and salt and baking the cake over the embers of the hearth. Dividing the pieces between them, they would eat them without a word and walk backwards to bed, expecting to see their future husband offering them a drink of water in a dream. Other means to learn the identity of your future spouse were to steal a salt herring from your neighbor, eat it including the bones and then retire to bed at midnight, or to take a mouthful of water and a pinch of salt into your hands while listening in on your neighbor's conversation - the first name mentioned would be that of your spouse. Finally, any leftovers from the evening meal - usually consisting of mrastyr, a dish made of potatoes, parsnips, and fish mashed up with butter - would be put out for the fairies, in addition to jugs of fresh water.

The characteristic turnip lanterns can also be found in the West Country of England: In a local tradition known as Punkie Night, the children of Somerset will go around with a jack o'lantern on the last Thursday of October, singing ryhmes like "Give me a candle, give me a light/If you don't, you'll get a fright" or "Give me a candle, give me a light/If you don't, a penny's all right". The lyrics originates from the tradition of children begging for candles and money, possibly to help their families through the winter. In times past, farmers would also put a "Punkie", as the lanterns are called by the locals, on their gates to ward off evil spirits.

Meanwhile, in Cornwall, Kalan Gwav ("the first day of winter"), also known as Allantide or Saint Allan's Day, is a festival held on the eve of November 1st in honor of St. Allan, who was the bishop of the Briton city Quimper in the 6th century. Although dedicated to Christian souls in an intermediate state, the most recognizable symbol of the holiday were the large, red, glossy Allan's apples which people would buy from markets to gift them to friends and relatives as tokens of good luck. Girls put the apples under their pillows in the hopes of dreaming of the person they would one day marry, and similar to the Irish variant of snap apple, there was a local game where four apples would be fixed to a cross with candles on it which was hung from the ceiling - if you failed catching the apples with your mouth, you would be hit by the hot wax. In addition, the custom of throwing two walnuts into the fire to divine the fidelity of a partner also existed in Cornwall, as well as pouring molten lead into water to see what shape it took, which was supposed to indicate the occupation of your future husband.

Turnip lanterns were not only common in Ireland, but also Scotland, Wales, the Isle of Manx, Somerset, and Cornwall; above is an example from the latter region (Source)

In Wales, the same festival is known as Calan Gaeaf, with Nos Calan Gaeaf - the night preceding November 1st - being one of the three Ysbrydnos, the "spirit nights" of the year. Around this time, people avoid going near churchyards, stiles, and crossroads, as spirits are believed to gather in these places. According to old tradition, a bonfire would be lit on the night of October 31st, while women and children would mark rocks with their names or other signs and place them in and around the fire. All of them would dance around the fire it died down, and once it did, everyone would rush to their homes, believing that two fearsome apparitions known as Yr Hwch Ddu Gwta (a tailess black sow accompanied by a headless woman) and Y Ladi Wen ("the white lady", another headless ghost) would chase them and devour the soul of the last one to remain behind. On the following morning, all stones of the villagers would be checked, and if they were burned clean, it considered a sign of good luck - if any were missing, however, that meant the person who marked it would die within a year. Apple bobbing, known as Twco Fala in Wales, was also a popular game at Calan Gaeaf, and there were various customs which allegedly allowed you to see into the future. For the boys, it was cutting ten leaves of Ivy, throwing one away and placing the rest under their pillow before going to sleep, while the girls would have to take their time to grow a rose in the form of a hoop, pass through the ring three times, and then cut the rose to place it under their pillow. If unmarried women darkened their rooms and looked into the window at Nos Calan Gaeaf, it was said they would see the face of their future groom - if not, they should peel an apple and throw the peel over their shoulder, which would form the initial letter of their husband's name. However, if the woman saw a skull in the mirror, it meant she would die during the next year.

Still, there were some Welsh traditions that slightly differed from the usual Samhain ones: The custom of the caseg fedi, also known as "harvest mare", was once very common in Wales. When the harvest was almost done, the last sheaf of corn on the field would be left standing, with the men of the reaping party trying to cut it down by throwing their hooks. The most unskilled worker would begin, and it was a great honor for whoever managed to cut the caseg fedi, which would be braided into the shape of a small horse or a woman afterwards. Female grain figures were colloquially called "Cailleach", after the old, sorcerous hag from Gaelic myth who acted as a personification of winter (alternatively, the word cailleach could also mean "witch"). Still, the ritual was not complete yet: The one who cut the caseg fedi also had the duty of bringing the sheaf into the house without it getting wet, which was made difficult by servant maids who were waiting next to the house with buckets of water to douse the reaper. If he managed to keep it dry regardless, the house's owner would give the reaper money for as much beer as he desired; if not, he would have to endure sitting at the foot of the table in shame. Once the harvest was brought in and the livestock to be slaughtered had been chosen, a large feast would be prepared, with all the women of the village lending a hand in cooking the food. As thanks for the harvest, people would eat a dish known as stwmp naw rhyw cooked over a large fire, usually containing various kinds of vegetables, milk, and butter. Although many of these customs have died out nowadays, it's evident the Welsh folk beliefs have strongly influenced some later All Hallow's Eve traditions observed in the country: People would light candles in the church, believing to be able to predict the future from the way they burned, as well as preparing the hearth at home for the arrival of their dead relatives, put some food outside, and leave the doors unlocked. The Allhallowtide tradition of "souling" - gathering soul cakes in exchange for reciting songs - was known as "collecting food for the messenger of the dead", and people would pray to God to "bless the next crop of wheat" upon receiving soul cakes.