#sōtō

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

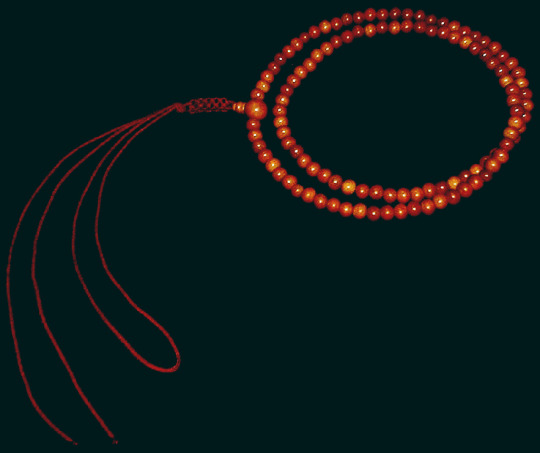

JAPANESE BUDDHIST PRAYER BEADS

General

"The Buddhist rosary was introduced to Japan in the early stages of Japanese Buddhism... Although rosaries were probably considered valuable objects since the introduction of Buddhism in Japan, it seems they were not widely used in religious practices for another several centuries. Only by the Kamakura period (1185–1333) do prayer beads seem to have become common ritual implements."

"The form of the first prayer beads in Japan already varied, but over the centuries, the rosary was further modified to fit the usage and doctrine of different schools. As a result, various distinct forms developed, which can be easily distinguished from each other today. The rosaries differ, for example, in the number of larger beads, tassels, or beads on the strings attached to the larger beads... Also, the manner of how to hold a rosary differs depending on the school."

The most common term for the rosary is juzu 数珠 (Ch. shuzhu), literally ��counting beads” or “telling beads,” which hints at the ritual usage of the beads for counting recitations. The other common term, nenju 念珠 (Ch. nianzhu), can be understood either as “recitation beads,” describing the beads as an aid in chanting practices, or as “mindfulness beads,” suggesting that “chanting is an aid to meditation and even a form of it.”

(from Prayer beads in Japanese Sōtō Zen, link under Sōtō)

Juzu beads in two different styles. Image from Wikimedia Commons by Suguri_F.

The number of beads

"The earliest text on prayer beads, the Mu huanzi jing, states that the rosary should have 108 beads, which is the most common number of beads in a Buddhist rosary. Other sutras further mention rosaries with 1,080, fifty-four, forty-two, twenty-seven, twenty-one, and fourteen beads. Lower numbers than 108 are encouraged, if one has difficulties obtaining 108 beads. Rosaries with thirty-six or eighteen beads are also used in Japan."

(from Prayer beads in Japanese Sōtō Zen, link under Sōtō)

108: The number 108 has many symbolic associations. Most commonly the 108 beads are associated with the 108 defilements. The number 108 further represents the 108 deities of the diamond realm (kongōkai) in esoteric Buddhism, or the 108 kinds of samādhi.

54: The number fifty-four stands for the fifty four stages of practice consisting of the ten stages of faith, ten abodes, ten practices, ten transferences of merit, ten grounds, and the four wholesome roots.

42: The number forty-two expresses the ten abodes, ten practices, ten transferences of merit, ten grounds, plus the two stages of “equal” and marvelous enlightenment (tōgaku and myōgaku).

27: Twenty-seven symbolizes the stages toward arhatship.

21: The number twenty-one further represents the ten grounds of inherent qualities, plus the ten grounds of the qualities produced by practice, plus buddhahood.

The names of the beads

"A rosary has at least one large bead, which is called the mother bead (boju) or parent bead (oya dama) alerting the user that they have finished one round of the rosary. When finishing one round, the user should not cross over the mother bead, as this would be a major offense; instead, they should reverse the direction."

"Sometimes a rosary has two larger beads; in this case, the second larger bead is either called middle bead (nakadama), as it marks the middle of the rosary, or also mother bead. The other beads on the main string are called retainer beads (ju dama) or children beads (ko dama). There are four beads among the retainer beads that are usually of smaller size and/or different color. They are placed after the seventh and the twenty-first beads on both sides of the (main) mother bead and therefore mark the seventh or twenty-first recitation. These four beads are called shiten 四点 beads (lit. four point beads). They are often interpreted as the four heavenly kings (Shitennō), Jikokuten (Skt. Dhṛtarāṣṭra), Tamonten (also called Bishamonten, Skt. Vaiśravaṇa), Zōjōten (Skt. Virūḍhaka), and Kōmokuten (Skt. Virūpākṣa). The beads are therefore also called “four heavenly kings” (shiten 四天), a homophone of “four points.”

"The main mother bead, and sometimes also the middle bead, has tassels attached. Usually, there are two short strings with smaller beads, known as recorder beads (kishi dama) or disciple beads (deshi dama), attached to the main mother bead. These beads help to count the rounds of recitations. They are thought to symbolize the ten pāramitās or, especially if they are called disciple beads, the Buddha’s direct disciples. At the end of the strings just above the tassels are the recorder bead stoppers, which are called dewdrop beads (tsuyudama), because they are often shaped like teardrops. The string between the mother bead and the recorder beads has usually a small loop, and on one side of this loop is a small bead, which is called jōmyō 浄明 (lit. pure and bright)... The bead is also called successor bodhisattva (fusho bosatsu) because it might take the place of any recorder bead that might be broken."

(from Prayer beads in Japanese Sōtō Zen, link under Sōtō)

Prayer beads in different Japanese schools

Jōdō (Pure Land)

Nichiren

A set of garnet Nichiren Shoshu Juzu prayer beads. Image from Wikimedia Commons by BeccaTrans.

Ōbaku

Rinzai

Honren juzu beads used in the Rinzai sect of Zen Buddhism. Image from Wikimedia Commons by Peehyoro Acala.

Shingon

Sōtō

Dōgen, the founder of the Sōtō Zen school, wrote about prayer beads: “You should not hold a rosary in the hall" and later writes that a monk should not disturb others by making a sound with the rosary on the raised platform. Later still, he elaborates “In the study hall, you should not disturb the pure assembly by reading sutras with loud voices or loudly intoning poems. Do not boisterously raise your voice while chanting dharani. It is further discourteous to hold a rosary facing others.”

"Considering these three brief statements in Dōgen’s works, we can presume that the rosary played no significant role for Dōgen and his community. Yet some prayer beads left by early Sōtō monks have been regarded as temple treasures and have been venerated as a contact relic in remembrance of the master. One example is a rosary made of beautiful rock crystal that Keizan used and that is now preserved at the temple Yōkōji in Ishikawa prefecture."

The form of the Sōtō rosary changed over time. Today’s formal Sōtō rosary has 108 beads and two mother beads, one larger one, and a slightly smaller one, as well as the four point beads. It has tassels only on the main mother bead, but there are no beads on the strings attached to this bead. The contemporary formal Sōtō rosary also has a small metal ring, which symbolizes the circle of rebirth in the six realms. In the Rinzai and Ōbaku schools this ring is not part of the rosary and, therefore, a Sōtō rosary can easily be distinguished from rosaries of the other Zen schools. When Sōtō clerics added this metal ring is unclear. ...This metal ring was not part of the Sōtō rosary in the Tokugawa period and therefore must have been added later."

(from Prayer beads in Japanese Sōtō Zen, link below)

⚫️ Sōtō Zen - Wikipedia

⚫️ Prayer Beads in Japanese Sōtō Zen by Michaela Mross (link to download)

⚫️ Memorial service etiquette (sotozen.com)

Tendai

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Đôi Điều Học Được Hôm Nay - Ngô Khôn Trí

Sáng nay nhận được mail của một anh bạn, anh nói bài viết “Chai nước uống thừa” mà tôi chuyển cho anh đáng để chúng ta suy nghĩ lại và người Nhật có nhiều cái hay để mình học hỏi. Anh rất thích văn hóa Nhật nên thỉnh thoảng gởi những bài thơ Haiku của thiền sư thi sĩ nổi tiếng Matsuo Basho cho tôi, anh nói hiện nay anh đang tìm hiểu thêm về Zen, Okinawa cuisine, Buddhist temple, shiatsu,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Okay gonna rewrite my whole rant now dsnfjnfdkjs

So I want to clarify that while the mistranslations of the English Writing Team for V3 is incredibly frustrating, I can see that most of their mistakes weren't intentional, but likely due to how different of a language Japanese is from English.

Case in point: Kokichi's official title in Japanese is "総統" Which is pronounced "Sōtō" (Or like SouTou). "Sōtō" translates to Supreme Leader, which has some connections/associations to tyranny or evil. (Think super villains and stuff)

However, the way "Sōtō" is verbally spoken is very similar to 曹洞宗, or "Sōtō-Zen", which heavily relates to Japanese Buddhism.

This plays with the duality of Kokichi as a character and hints at that duality--the mask of the Mastermind, and the true self of a Pacifist. The spoken word "Sōtō" out of context can mean either the "Supreme Leader" aspect, or the "Buddhist" aspect.

This is, however, not translatable.

There is no word in English that can be used for both these words--there is no way to say "leader" that can be either malicious or kind, so when you translate "Sōtō" to "Supreme Leader", you're missing half of the context of the title. You are specifically missing the ties to buddhism context, thusly, you are only getting the ties to tyranny context, which colors the perception of the character to sway more evil that possibly intended.

This is probably going to be a big theme of this translation project, but I suspect that ambiguity plays a large role in why things are changed so drastically from the Japanese version to the English version.

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Life is also Buddha-nature, death is also Buddha-nature.” - Dōgen

[Dōgen (19 January 1200 – 22 September 1253), was a Japanese Zen Buddhist monk, writer, poet, philosopher, and founder of the Sōtō school of Zen in Japan.]

All existence is ‘ present moment’ and ‘ Buddha nature’, said Zen Master Dogen, and he had the following thoughts on the relationship between Buddha nature and death:

"It is a complete lack of understanding to think that Buddha-nature only exists while we are alive and disappears when we die.The state of being alive is Buddha-nature, and the state of being dead is also Buddha-nature."

In short, he argues that it is the work of heretic to cling to the idea that Buddha-nature is or is not Buddha-nature, depending on whether we can recognise it or not. Buddha-nature remains Buddha-nature, regardless of whether there is a cognitive subject or not, or whether the subject is human or not. According to Dogen, all beings (the entire universe) are of the Buddha nature, as in the interpretation of ‘all-encompassing Buddha nature’. If Buddha-nature is the entire universe itself, we are born, live, and die within Buddha-nature. In other words, life is also Buddha-nature, and death is also Buddha-nature. That is what Buddha nature is. Whether you are old or young, you are still alive. There is no need to think about "end of life". When you live, you should live well, and when you die, you should die well.

That is what Zen Master Dogen means by ‘the time of encounter’.

All we have is the here and now. It exists in the moment, not in the past or the future. We tend to see it as something that moves continuously, like when a movie film is spun. Instead, just look at each frame of film.

This is not only said by Zen Master Dogen, but also by the Buddha.

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sometimes I see Zen Buddhism, specifically, mentioned in the same breath as Shinto as a particularly historically influential and quintessentially Japanese religious tradition. But that perception is honestly inflated and vastly more influenced by The West™'s familiarity with Zen aesthetics than historical reality.

Zen derives from the mainland Chán tradition. And although Japanese Zen thinkers like Dōgen and Eisai were certainly innovative in their own right, Sōtō Zen and Rinzai Zen were attempts at importing the Cáodòng and Línjì traditions from China, not at innovating entirely new ones.

The most enduringly popular form of Buddhism in Japan even to this day is Pure Land, and in particular Jōdo Shinshu. And the most uniquely Japanese one is Nichiren.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

黄実千両|黄実仙蓼[Kiminosenryō] Sarcandra glabra f. flava

黄[Ki] : Yellow

実[Mi] : Fruit

(の[No]) : Of

千[Sen] : One thousand

両[Ryō] : A unit of currency used in the past

仙[Sen] : Immortal mountain wizard in Taoism; hermit

蓼[Ryō] : Knotweed(Polygonaceae)

The normal Senryō produces red fruits.

昔は盲人に特別の位を与えたものである。よく何市、何市とあるが、あれも市名といって、盲人の位の一つで、一番下である。しかし何といっても一番よいのは撿挍であって、昔は撿挍になるには千両の金を納めなければならなかった。その代り十万石の大名に相当する資格が与えられていた。その次は勾当で、これは撿挍の半分位の資格であった。

[Mukashi wa mōjin ni tokubetsu no kurai wo ataeta mono de aru. Yoku nani-ichi, nani-ichi to aru ga, are mo ichina to itte, mōjin no kurai no hitotsu de, ichiban shita de aru. Shikashi nan to ittemo ichiban yoi no wa kengyō de atte, mukashi wa kengyō ni naru niwa senryō no kane wo osame nakereba naranakatta. Sono kawari jūman-goku no daimyō ni sōtō suru shikaku ga atae rarete ita. Sono tsugi wa kōtō de, kore wa kengyō no hanbun kurai no shikaku de atta.] In the past, (statesmen) gave special statuses to blind people. It is often said "So-and-so-ichi" "So-and-so-ichi," and this is called Ichina, which is one of the statuses of blind people, the lowest. After all, the best is Kengyō, and in the old days, to become Kengyō, they had to pay one thousand ryō. Instead, they were qualified to the equivalent of a ten thousand koku feudal lord. The next position is Kōtō, which was about half as qualified as Kengyō. From Mukashi no mōjin to gaikoku no mōjin(The blind of old and the blind of foreign lands) by Miyagi Michio Source: https://www.aozora.gr.jp/cards/001288/files/47117_29089.html (ja) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zatoichi_(disambiguation) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Koku https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michio_Miyagi https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gND5pFB9nmU (About a certain Kengyō) https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20200611/p2a/00m/0na/009000c

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zen (2009)

"We must create paradise here on Earth. But if this is paradise, why must people fight and suffer from illness, unable to escape the pain of death?"

youtube

The life of Zen Master, Dōgen. He went to China to attain enlightenment and returned to Japan during Kamakura Period, and introduced Zen to Japan in the form of the Sōtō school.

His teachings of new Zen Buddhism sparks outrage among existing Buddhist sect while attracting a few who wants to be free of pain and suffering, like a prostitute and a weathered Samurai.

#zen#禅#nakamura kankuro#uchida yuki#japanese movie#j movie#japanese film#japanese drama#j drama#jdrama#asian drama#asian movie#zen buddhism#dogen#Youtube#yuki uchida#kankuro nakamura#kamakura period#japan#zazen#buddhism#film aesthetic#aesthetics

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

A pamphlet from Eiheiji Temple (永平寺) in Eiheiji Town, Fukui Prefecture, founded by the monk Eihei Dōgen (永平道元) in 1244 and one of the two principal temples of the Sōtō school of Zen Buddhism

Acquired at the temple November 3, 1996

#buddhist temple#福井県#fukui prefecture#永平寺町#eiheiji cho#永平寺#eiheiji#曹洞宗#soto zen#zen buddhism#道元#dogen#永平道元#eihei dogen#道元希玄#dogen kigen#pamphlet#ephemera#printed ephemera#paper ephemera#crazyfoxarchives

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Independent Academic Reflection - Zen Buddhism

Following the tour of the Daitokuji temple, a group of us decided to return for the one hour ¬-meditation that was hosted by a Buddhist priest/monk at at the Daisen-en temple within the greater Daitokuji. Nico, Vishnu, Eliza, Sam (boy), Xander, and I partook in the meditation that required us to sit in criss-cross apple sauce position with a perfect posture for one hour. However, we did not know this going into the Zen meditation session, so I thought it was going to consist of laying down, like how they do in Shavasana yoga. However, the lady who had given us the tour earlier in the day explained the entire process of sitting up straight, keeping our eyes open, making a cup with our hands, and how to ask to get hit with a big wooden stick. I was genuinely scared after her explanation, but it was too late to leave as we were already sitting on the mats in front of the rock garden. It only costed 1000 yen and it was a gorgeous ceremony of reflection, pain, and solitude. I started off the blog post for that day with “Today I learned that there is some beauty in suffering” and I still stand by those words. We were allowed to get slapped by a stick if we were in pain and wanted to take a couple seconds to readjust our position. I do admit I had to get slapped twice because I was in pain because I am not that flexible. My body was visibly shaking after the first ten minutes and after about twenty minutes, Nico elected to get slapped. One by one, we all took turns bowing to the intimidating monk, bending over, and getting hit twice on each side of our back. However, the slaps were helpful, and I welcomed them with grace. The experience allowed me to clear my head, empty my thoughts, and to become one with the garden that I was staring at for the entire hour. It was one of the most mentally challenging experiences of my life, because I tried to force my body to fight through the pain and uncontrollable pain in order to not get hit.

Academic Section

The article that I will be utilizing for this Academic Reflection regarding Zen Buddhism and meditation is named “Japanese Zen Buddhist Philosophy”, written by Shigenori Nagatomo. This piece in particular characterizes the historical development, key figures, practices, and philosophical concepts of Zen Buddhism. However, I will be discussing the methods of Zen, the three-step practice of Zen, and the comparison of these to my experience at the Daisen-en temple at Daitokuji in Kyoto.

There are two techniques of practicing meditation in Zen Buddhism: the kōan practice and the “just sitting” skill. These combined with the breathing exercise of sūsokukan, are practiced to sculpt the best version of the whole person and correct the settings of one’s mind. The kōan method assists the person to become a “Zen person” who is supposed to be humble and compassionate. It was formulated by the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism, and it involves contemplating paradoxical or puzzling statements or questions. The other technique, the “just sitting” practice, was developed Sōtō school in which the person just simply sits and is derived from the idea of “practice-realization”. This refers to the belief that meditation is not a means to an end, but a means to realization. The Sōtō school thought that meditation was to be viewed as a process of inner discovery and gradual enlightenment.

The three step process of Zen Buddhism includes the adjustment of the body, the adjustment of the breath, and the adjustment of the mind. The adjustment of the body is not limited to one pose during meditation, but it refers to maintaining a healthy lifestyle of proper dieting and exercise, as well as nurturing a healthy mind-body connection. The proper technique is to assume the lotus position, which involves a criss-cross apple sauce fold of the legs with your hands on your knees and palms facing the air. The adjustment of the breath refers to the practice of sūsokukan, or the observation of the breath. n this technique, the practitioner counts their in-breath and out-breath while performing abdominal breathing, which involves bringing air down to the lower abdomen. This exercise revitalizes the mind-body and expels negative energy, requiring ample ventilation. Finally, the adjustment of the mind refers to disengaging the practitioner from the worries and woes of everyday life. This is hard to accomplish because in order to stop the mind from racing, one must use their mind to make this stop. However, through prolonged practice, the practitioner reaches a state where nothing appears, an experience referred to as "no-mind" in Zen.

With regards to my experience, I believe that I experienced the “just sitting” technique of Zen meditation along with the three step process. It was my first time undergoing this experience, so it was hard to incorporate the adjustment of the body, breath, and mind at the same time, but I was able to empty my mind at times, so I will say that my experience was successful in that sense. This experience was beautiful and inner meditation should be utilized in order to clear thoughts of one’s mind and to allow for easier focus and perception.

Works Cited:

Nagatomo, Shigenori. “Japanese Zen Buddhist Philosophy.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 31 July 2019, plato.stanford.edu/entries/japanese-zen/.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Huzzah! I have received a commission!

This is Uranai Sōtō! Thank you SugarSkullDemon for the commission!

0 notes

Text

La positive attitude

youtube

Que ce soit elle ou bien toi Les uns et les autres, ou même moi Nous avons tous pleuré Au moins une fois Pour un coup dur de la vie Une jalousie, un faux pas Il arrive parfois que ton moral se casse Pour ça, moi j'ai trouvé un remède efficace La positive attitude La positive attitude La tête haute Les yeux rivés sur le temps Et j'apprends à regarder droit devant La positive attitude...

Souviens-toi de ces instants précieux Qui ont rendu ton cœur si joyeux De ces histoires d'amour tellement essentielles Elles t'ont rendu la vie bien plus belle, bien plus belle Devant la douleur, tu dois savoir faire face Moi j'ai trouvé un remède très efficace...

La positive attitude La positive attitude La tête haute Les yeux rivés sur le temps Et j'apprends à regarder droit devant La positive attitude… La positive attitude La rage au ventre Je suis prête à tout surmonter Maintenant, je n'veux plus jamais renoncer à La positive attitude... La positive attitude...

« Le zen est une branche japonaise du bouddhisme mahāyāna hérité du chan chinois. Elle met l'accent sur la méditation (dhyāna) dans la posture assise dite de zazen.

Le mot « zen » est la romanisation de la prononciation japonaise du caractère chinois chinois simplifié : 禅 ; chinois traditionnel : 禪 ; pinyin : chán ; litt. « méditation » ; il est prononcé chán en mandarin, zeu en shanghaïen et est également appelé Son en Corée et Thiền au Vietnam. Ces différents termes dérivés du chinois, remontent à une origine commune : le mot sanskrit dhyāna, en pali jhāna (« recueillement parfait »). »

« L'approche du zen consiste à vivre dans le présent, dans l'« ici et maintenant », sans espoir ni crainte.

On peut dire approximativement que le zen Sōtō insiste sur la pratique de zazen (de za assis et zen méditation) et de shikantaza (seulement s'asseoir) alors que le zen Rinzai fait une large place aux kōan, apories, paradoxes à visée pédagogique dont la compréhension intellectuelle est impossible mais relève de l'intuition.

Zazen peut permettre de parvenir à l'éveil (satori) : pour Dôgen, la pratique elle-même est réalisation ; pratique et éveil sont comme la paume et le dos de la main. Il suffit de s’asseoir immobile et silencieux pour s'harmoniser avec l'illumination du Bouddha. Néanmoins, selon le bouddhisme zen, même l'éveil ne saurait être un but en soi. Zazen doit être sans but, il aide à la connaissance de soi-même et à la découverte de sa vraie nature.

Les kōan (école Rinzai) sont des propositions le plus souvent absurdes ou paradoxales que pose le maître et que le disciple doit dissoudre (plutôt que résoudre) dans la vacuité du non-sens et, par suite, noyer son moi dans une absence de tensions et de volonté, que l'on peut comparer à la surface parfaitement lisse d'un lac reflétant le monde comme un miroir.

Comme toutes les versions sinisées du bouddhisme, le zen appartient à l'ensemble mahāyāna, qui affirme que chacun possède en soi ce qu'il faut pour atteindre l'illumination. Certaines écoles (Tiantai, Huayan) considèrent que chacun et toute chose possèdent la « Nature de Bouddha ». La position zen, plus proche du courant philosophique du yogācāra, considère selon certains que la seule réalité de l'univers est celle de la conscience ; il n'y a donc rien d'autre à découvrir que la vraie nature de sa propre conscience unifiée. »

0 notes

Text

SŌTŌ-INSPIRED JUZU IN BAYONG

This is a juzu inspired by the contemporary prayer beads used by the Sōtō-sect, one of the Japanese Zen Buddhist schools (my post about Japanese Buddhist prayer beads). It has 108 counting beads, 4 marker beads in addition to the parent beads (the middle bead, also known as second parent bead, here similar to the markers) and a sliding ring typical of the Sōtō school. I did, however, use a stone ring instead of the metal (usually silver) ring used in the Sōtō juzu. The parent and marker beads divide the counters into sets of 18. The tassel is knotted from 6 strands of 1 mm thick satin rattail cord, 4 black and 2 coppery brown.

Materials:

Main (counting) beads (judama, kodama): 108, bayong, 8 mm

Parent (mother, guru) bead (oyadama): snowflake obsidian

Middle bead (nakadama) and marker (four point) beads (shiten): onyx, 6 mm

The ring and the two decorative beads (8 mm): carnelian

1 mm satin rattail cord

Black beading string (non-elastic)

#mala#full mala#108 bead mala#juzu-style mala#8mm mala#buddhist prayer beads#sōtō#bayong#snowflake obsidian#carnelian#onyx#by woodxstone

0 notes

Note

i am super facinated by the mistranslation saga you've got going on here. are there any less headache inducing but still strange mistranslations you can share with us?

Okay while I appreciate you guys valuing my opinion on things, please keep this in mind:

I Do Not Speak Japanese. All of the translations I'm doing are through the Google Translate App (which has shown to be imperfect!) and I consider my role in the project to mainly be using this app to get the Japanese text from the game and into a document for further analysis. Any and all current English Translations are done by the app, and aside from one correction one of my friends who knows a bit more Japanese pointed out, I will not be able to always catch weird translation issues unless I stumble across it via research (Ala the `Sōtō' thing, but that's not really an error so much as that is a "there is no English Equivalent of This" thing). I AM using the same website my friend recommended, but that does NOT mean I am qualified to do a 100% accurate translation on my own.

Right now, I'm only translating the evidence, which should logically be the most stable form of translation with Google Translate because there aren't many nuances in that text--at least, there shouldn't be. So far, the translations for the evidence only have been mostly accurate to the original English Dub, with some minor hiccups here and there on Google Translate's part.

Most of the nuances that are concerning should be in the main narrative, which I am personally not comfortable enough yet to try and translate with the app as I'm still learning how to best go about it.

I WILL be posting any notable things me and my friends catch, however, please be aware that I am not fluent in Japanese so my opinion on things really should not be the end-all-be-all to the English Translation.

I AM aiming to get the most unbiased, direct translation possible to showcase what the original Japanese Authors wanted to show, and I plan to set aside any and all biases I can for that purpose, but please keep it in mind regardless.

Short answer is: No, not yet. Google Translate apparently hates Tennis Net Wires though for some reason.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (72b): Nambō Sōkei’s Collection of Wabi Tea Utensils (Part 2: Chawan).

Tainei-ji ido-te chawan [大寧寺井土手茶碗]¹.

﹆This chawan has a large crack [in the side]².

Ordinarily, with respect to the performing of the temae, ([Ri]kyū said [that]) long ago, when the Shukō-chawan was as [yet] undamaged, there was nothing special about the way things were done³.

But later, after the crack had developed, on occasions such as when the weather was very cold, beginning some time before [the gathering was scheduled to take place], [the chawan] would be soaked in water until the water had thoroughly infiltrated [into the clay]: then hot water would be added [to the water in which the chawan was soaking] little by little [to raise the temperature gradually]⁴. After that [when the water in which the chawan is soaking has become very hot], [the chawan] should be heated with very hot water; and then [after drying the chawan,] the chakin[, chasen, and chashaku] are arranged in it, and it is carried out [to the temae-za]⁵.

When things had been done in this way, because [the chawan] would now be very wet, it was not put into its bag [before it was taken out to the utensil mat]⁶.

However, once [the weather] had become warm, after moistening it, [the chawan] was wiped [with a towel] to dry it: then it could be inserted into its bag [and displayed in the tearoom in the original way] -- this was the point of Jōō’s story⁷.

〽 Yōhen-temmoku [窯變天目]⁸:

﹆bestowed [upon Nambō Sōkei] by [Lord Hideyoshi]⁹;

﹆accompanied by a guri-guri [temmoku-]dai [グリグリ臺]¹⁰.

〽 Shimasuji-kuro chawan [嶋筋黒茶碗]¹¹.

﹆This [chawan] was given [to me] by Lord [Ri]kyū¹².

It was ready just in time [to be used during] the kuchi-kiri [gathering] in the first year of Tenshō [= early November, 1573]¹³. Even though it was a new[ly made] piece, [Ri]kyū was particularly pleased by it, so [he] gave it [to me]¹⁴.

[But before he did so,] he had used it frequently when offering tea [to his guests]; and during the winter and spring [following the kuchi-kiri chakai], he used it almost every day -- and for this reason it is truly a treasure¹⁵.

[The shimasuji-kuro chawan] that was larger, [Rikyū] passed on to Furuta Oribe¹⁶.

_________________________

¹Tainei-ji ido-te chawan [大寧寺井土手茶碗].

After a careful review of all of the documents (including all of the major kaiki [會記] from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries) available in my own library, as well as on line, I have found no references to a chawan of this name anywhere -- other than in this entry in Book Seven of the Nampō Roku. Certainly it does not seem to have been known during Rikyū's lifetime, meaning that neither could it have been used by Rikyū, nor been part of Nambō Sōkei’s collection.

In order to understand the meaning of Tainei-ji ido-te chawan, the name should be divided into two parts:

- Tainei-ji [大寧寺] ascribes ownership of this chawan either to the Tainei-ji (an important Sōtō-shū [曹洞宗] Zen training-temple in Nagato [長門] province, on the north-western coast of the main island of Honshū) -- that is, it was one of the temple’s special treasures -- or that it was owned by a monk who was closely affiliated with that temple (whose name was either lost, or suppressed -- for whatever reason);

- ido-te chawan [井土手茶碗] means that this bowl was “in the style of” an ido chawan*.

With respect to the first of these matters, when considering how the chawan came to the notice of the Sen family, the main buildings in the Tainei-ji temple complex (including the hondō [本堂], the main Buddha Hall, and san-mon [山門], the ornamental front gate of the temple) were destroyed by fire in 1640, with rebuilding efforts commencing around 1677. Either of these occurrences could explain how this chawan came to be separated from the temple†.

Tanaka Senshō is the only commentator to devote any part of his remarks to this chawan, and his conclusion seems to have been that it was most likely not an ido chawan (and certainly not one that had been brought to Japan in the years prior to the invasions of Korea in the 1590s).

But if the Tainei-ji ido-te chawan was not an ido chawan, the question arises as to what it was – what kind of bowl, that was not an ido chawan, yet resembled an ido chawan closely enough that it would be considered “in the same style” -- and the most likely option would seem to be that it was one of the first generation of bowls fired at the Hagi kiln.

The potters who traveled to Japan from Korea in 1603‡, landed somewhere on the coast of Nagato province. Their original purpose in coming to Japan had been to deliver a number of chawan, including the bowls that had been thrown by Furuta Sōshitsu (Oribe) in 1592 or 1593, while he was staying in an area to the east of the walled city of Dongnae [Busan] -- and studying Korean potting techniques with the potters there**. The chawan from that time had apparently been fired and glazed after Oribe resumed his military responsibilities, and then preserved carefully by the potters††; and once the political unrest (in both Korea and in Japan) had settled down, they decided to deliver the bowls‡‡ (presumably by seeking out Furuta Oribe himself).

Whether they were ever able to contact Furuta Sōshitsu or not, the bowls certainly created quite an impression in Japan, and those Korean potters were invited***, by the daimyō of the province, to establish a kiln near the city of Hagi (which was the capital of the province at that time); and that was the origin of the Hagi kiln (which, unlike many other kilns of the time, was from the first commissioned to produce copies of the ido chawan, rather than make pottery for domestic use). The Tainei-ji is not very far from Hagi, and was also supported by the Mori family (which had been the dominant family in the province since 1551), and it is entirely plausible that the Tainei-ji ido-te chawan was one of those pieces that had been presented to the temple by the daimyō Mori Terumoto [毛利輝元; 1553 ~ 1625], which would account for its being treasured there†††.

One good candidate for a bowl of this sort is shown below.

The fact that this chawan is also cracked, damage sustained during the early Edo period (possibly during the fire at the Tainei-ji), adds support to this argument, since the kaki-ire [書入] that was appended to this line addresses the special way to use a chawan that is cracked, or has been repaired. ___________ *Tanaka, however, mentions that, according to one argument, the designation ido-te [井土手 = 井戸手], refers to those bowls that were later classified as ido-waki [井戸脇] during the Edo period -- ido-waki apparently referring to those bowls that were brought back to Japan during the invasions of Korea, in the 1590s). While the precise date when this reclassification occurred is in doubt (meaning whether or not it could be applicable to the present issue), if ido-te was intended to mean an ido chawan that had been brought back to Japan in the years after Rikyū’s death, the most likely candidate (according to Tanaka’s reasoning) would seem to be the bowl that was at that time owned by Mori Terumoto, shown below.

Today this chawan is known as the Mori-ido [毛利井戸].

That said, this chawan is not only cracked, but is missing part of the side (that part has been turned so that it faces the back). The repair was done by mixing a kind of ocher-rich clay (called to-no-ko [砥粉]) with lacquer to form a sort of putty, which is then molded into the empty space. This kind of repair work would not take kindly to being immersed in water for an extended period of time (as described in the kaki-ire) -- though it is not clear when the chawan was damaged in this way.

†In other words, either the chawan was taken away by one of the occupants of the temple during the fire (either to protect the bowl, or as illicit plunder), or it was offered as a thank-gift to the person responsible for initiating the reconstruction.

In the first case, since the temple seems to have been closed for almost four decades, while the original intention may have been to preserve the chawan, circumstances may have eventually forced the person who took it to sell it (in order to provide for their livelihood).

Temple lore suggests that the reconstruction was initiated by Masuda Mototaka [益田元尭; 1595 ~ 1658], a high-ranking hereditary retainer of the Mori [毛利] family, who assumed a hegemony over the province after the decline of the Ōuchi [大内] family. The problem with this account is that Mototaka died in 1658, while the reconstruction was not begun until 1677. Be that as it may, this does not discount the possibility that the chawan was presented to the individual responsible for the reconstruction, and from him it came to the attention of the Sen family (perhaps with Rikyū’s or Sōkei’s name included in the denrai to enhance the chawan’s antecedents).

‡Takuan Sōhō traveled to Japan together with this party of potters (according to Kanshū oshō-sama, who narrated all of these details for me). In all likelihood, Takuan was able to do this without having to pay for his passage. (Because his purpose was to transmit Korean Zen to Japan, the potters and sailors would have accepted his presence as a deed that would accumulate spiritual merit for themselves -- and it is also likely that they believed that the presence of the monk might help protect the vessel from the dangers of sailing on the open sea. The ship seems to have been quite small, and both superstitions were common during the period.)

**Oribe seems to have been a particularly inept military man, with little interest in martial matters or discipline. During the Kyūshū campaign, where he occupied a position of importance in Hideyoshi’s army, he absented himself so that he could study with the potters at Karatsu – and only managed to save his neck from Hideyoshi’s wrath when he hosted a gathering for Hideyoshi at which he used all of the pieces that he had been working on at Karatsu, which apparently amused Hideyoshi well enough that he was willing to put aside his anger. Though why Hideyoshi later trusted him to be one of his two generals in Korea is something that is difficult (for me) to understand (since, after arriving in Korea, Oribe promptly decamped to go and study pottery).

The other general, Hosokawa Tadaoki (Sansai), however, does not seem to have been completely immersed in his military duties either, since he found time to study Korean ornamental knot-tying (producing an illustrated treatise on this art upon his return to Japan).

††It is possible that the Korean potters also made additional copies some of Oribe’s bowls (since these would have been good indicators of the kind of pieces that would be appreciated by the Japanese), for inclusion in this collection -- since their goal had clearly been to turn a profit from this endeavor (the demand for pottery in Korea would have plummeted in the years after the wars, with only the most utilitarian of pieces being required by the decimated population; so once news of the establishment of a new government that was intent on repudiating Hideyoshi’s policies came to Korea, the potters may have seen their chance to better their finances -- since they appear to have formed a good impression of Furuta Sōshitsu, at least).

‡‡The bowls now know as gosho-maru [御所丸] and Furuta kōrai [古田高麗], among many others (that suddenly appeared at the beginning of the Edo period), seem to have been part of this collection.

***Some 20th century Korean scholars have argued that the potters were detained, and then enslaved. This, however, was denied (to me, personally) by the descendants of the potters themselves, who argue that it was their choice to establish the kiln at Hagi (because had they returned to Korea, their life would have been much more difficult, and certainly much poorer, than the alternative).

The earliest of the bowls were virtually identical to those that had been produced in Korea, with the major differences being their color (the early Hagi glaze ranged between white and beige, whereas those bowls fired in Korea were pinkish, ocher-yellow, or tinged with gray-blue), and the fact that these Hagi bowls were crafted specifically for use in chanoyu (which may have made them seem somehow superior to the original Korean pieces).

†††The original ido bowls were made as je-gi [제기 = 祭器], ceremonial bowls employed for the offerings during Ancestor-worship rites, for use by the lower classes (the upper classes used pieces made from Korean celadon and bronze). This purpose is why these bowls have such prominent feet (which took the place of the high-footed saucers used by the upper classes).

The “ido-style” chawan produced by the first potters have more modestly turned feet, and their shapes are also better suited to chanoyu than many of the original Korean pieces (which were not made as chawan).

²Kono chawan ōki ni hibiki ari [此茶盌大ニヒヾキアリ].

Ōki ni hibiki* [大きに罅きあり] means a large crack. __________ *This word is usually pronounced hibi [罅] today -- and I can find no classical form where it ends with -ki.

Perhaps the katakana ki [キ] was accidentally transposed (from its position following the kanji ō [大]) when the text was copied.

³Tsune no gotoku temae shitaru ni, Kyū iu, Shukō-no-chawan, mukashi mu-kizu no toki ha betsu-gi nashi [如常手前シタルニ、休云、珠光ノ茶盌、昔無疵ノ時ハ別義ナシ].

Tsune no gotoku [如常 = 常の如く] means “as usual....”

Temae shitaru ni [手前爲たるに] means “when doing (performing) the temae....”

Kyū iu [休云う] means Rikyū said*....

Shukō-no-chawan†, mukashi mu-kizu no toki ha betsu-gi nashi [珠光の茶碗、昔無疵の時は別儀なし]: Shukō-no-chawan [珠光の茶碗] means the Shukō-chawan, the famous gray-green glazed chawan originally owned by Shukō (an example of this kind of chawan is shown above‡); mu-kizu no toki [昔無疵の時] means at the time when it was not cracked**; betsu-gi†† nashi [別儀なし] means there was nothing special that needed to be done (when using this chawan to serve tea), there were no special considerations that the host had to keep in mind (when using it during a gathering).

While Shibayama Fugen’s toku-shu shahon version of this text looks a little different, these are orthographic variations that result in no differences either in the spoken words, or in the meaning. __________ *This interpolation adds nothing to the explanation. It was probably inserted in order to make the argument appear to be authentic.

In fact, elsewhere Rikyū describes how a damaged chawan was supposed to be used (by first putting half of a hishaku of room-temperature water from the mizusashi into the chawan, to which hot water was added twice -- first a quarter hishaku, and then, without discarding the first, another half hishaku -- to increase the temperature of the chawan gently).

The procedure described in this kaki-ire seems to be one that was concocted independently by the Sen family (probably based on the machi-shū traditions that extended back to Imai Sōkyū).

Soaking utensils in water (especially with respect to things like the kiji-tsurube and unglazed pottery mizusashi and koboshi) is still urged by the Sen schools and those schools that branched off from them even today. While it might seem reasonable, if the piece (especially a cracked object such as a chawan) has been completely infiltrated by water, not only will it be very slow to dry afterward (often taking 2 weeks or more before it can be placed in its box), but in extremely cold weather (and when there is no heating system -- such as when the chawan is placed on a shelf in the open-sided mizuya veranda) the presence of water could actually cause the chawan to crack further. More will be said about this later.

†Notice that the original has chawan [茶盌], written with the weird second kanji that became fashionable during the second half of the seventeenth century.

‡Around 10 nearly-identical bowls of this type were brought to Japan by the Koreans escaping the Ming invasions of Korean peninsula during the mid-fifteenth century (the bowls differed from one another only in the number of strike-marks on the outer side, from a bundle of straws that were used to beat the slab of clay onto the conical mold that shaped the interior of the bowl), of which this is one. These bowls were originally made for use by street-side noodle booths in southern China (which is why the feet match nicely the circular bottom, allowing them to be stacked up securely when not in use).

All of the bowls were probably bought as a stack by an unknown monk who visited the area, to be distributed as souvenirs when he returned to Korea.

These bowls all measured 5-sun 2-bu in diameter. While originally employed only as kae-chawan, by the sixteenth century these bowls had come to be considered the largest size chawan that could be used when serving tea. (The significance of this measurement will be discussed further in footnote 11.)

**The damage (two small cracks near the rim) was first noticed while this chawan was in Jōō’s collection. Jōō immediately had the bowl repaired (by painting over the section where the cracks were observed with lacquer colored to match the glaze, thereby obscuring them completely).

Nevertheless, the cracks were still there, so Jōō did not use this chawan any more. He eventually gave it to Rikyū (along with several other “useless” pieces -- when Jōō took possession of Rikyū’s collection of utensils, at the time when his family declared bankruptcy). Jōō’s reasoning seems to have been that these utensils would allow Rikyū to continue practicing chanoyu (as an exercise in dō-zen [動禪], motion meditation), while discouraging him from doing so in front of any significant guests (since using damaged utensils was considered ill-omened, so the sort of people who were concerned about worldly chanoyu would be offended, and thenceforth avoid entering Rikyū’s tearoom, forcing him to either perform alone, or in front of those odd people who had no concern about such things).

††The original has betsu-gi [別義], which is probably a semantic mistake. The word should be betsu-gi [別儀].

⁴Nochi ni hibiki dekiru-shite ha, kan-ki no toki nado desaruru ni, mae yori mizu ni hitashi-uruowashi, zen-zen ni yu wo sashi-zoe [後ニヒヾキ出來シテハ、寒氣ノ時ナド出サルヽニ、前ヨリ水ニヒタシウルホハシ、漸〻ニ湯ヲサシソヘ].

Nochi ni hibiki dekiru-shite [後にひびき出來して] means later, after the crack(s) developed (in the Shukō-chawan*)....

Kan-ki no toki nado desareru ni [寒氣の時など出されるに] means if (the Shukō-chawan) was going to be brought at such times as when it was extremely cold....

Mae-yori [前より] means before (the chakai during which the Shukō-chawan was going to be used to serve tea)....

Hitashi-uruowasu [浸し潤るおわす] means to be soaked, steeped, or immersed (in water) so as to make something wet.

The chawan would be submerged in something like the chakin-darai [茶巾盥] (which, in that period, was made like a large mentsū, 7-sun in diameter) for this soaking.

Zen-zen ni yu wo sashi-zoe [漸々に湯を差し添え]: zen-zen ni [漸々に] means little by little, bit by bit, step by step; yu wo sashi-zoe [湯を差し添え] means hot water is added to (the vessel of cold water in which the Shukō-chawan has been immersed).

With respect to the second part of this sentence, Shibayama’s toku-shu shahon text has: sen-jitsu yori mizu ni hitashi-uruowashi, zen-zen ni yu wo sosogi sashi-zoe [前日ヨリ水ニヒタシウルホハシ、漸〻ニ湯ヲソヽギ差添].

Sen-jitsu yori [前日より] means from the day before (the chakai).

Zen-zen ni yu wo sosogi sashi-zoe [漸々に湯を注ぎ差し添え] means little by little hot water is added by drizzling it into (the water in which the chawan is soaking).

There is not really any significant difference in the English meaning between the two versions. __________ *Throughout this explanation, the Shukō-chawan is used as the underlying example of a broken (and repaired) chawan -- even though it is unlikely that any member of the Sen family ever saw it.

Probably this was because the Shukō-chawan was the first damaged chawan that was ever allowed to be used when serving tea. (Other bowls, once damaged, were never again used for chanoyu.)

This precedent is said to have actually been established by Rikyū (when he used this chawan, which he rested on a large red-lacquered hiki-hai [引盃] in lieu of a temmoku-dai, when serving tea to Jōō on the occasion of the master’s first visit to Rikyū’s house after the two had become acquainted -- the two were introduced to each other by Kitamuki Dōchin, so that Jōō could buy Rikyū’s collection of tea utensils, and Jōō’s visit was probably to thank Rikyū for selling the things to him).

⁵Sono ato ni e yu ni te tokuto tōjite, chakin wo shikomi hakobi-dasareshi nari [其後ニヱ湯ニテトクトトウジテ、茶巾ヲ仕込ハコビ出サレシ也].

Sono ato ni [h]e* [その後にへ] means after that (in other words, after warming the water in which the Shukō-chawan is soaking by pouring hot water slowly into it)....

Yu ni te tokuto† tōshite [湯にて特と通じて] means (the chawan) should be thoroughly (warmed) with hot water for a (fairly) long period of time‡.

Chakin wo shikomi hakobi-dasareshi nari [茶巾を仕込み運び出されしなり] means the chakin (and chasen and chashaku) are arranged in (the chawan), and it is carried out (to the utensil mat).

Aside from playing with the particle [h]e -- Shibayama has e [エ] -- the sentences are identical. __________ *E (actually, we) [ヱ] is used here in place of the particle [h]e [へ], as was sometimes done during the Edo period. It was pronounced “e.”

†Today this construction tokuto is usually written tokuto [篤と], rather than tokuto [特と] as in this text. It means thoroughly, fully, and also carefully.

In other words, the chawan should finally be heated with very hot water (such as that to which it will be exposed during the temae), but this should also be done carefully (to avoid damaging the chawan further).

‡The idea is that the chawan should be really hot -- that the clay body reaches the ambient temperature of the hot water. It will thus be so hot that it will remain very warm even after it has been carried out to the utensil mat -- so there is no danger that the shock of pouring boiling water from the kama into it will cause it further damage.

⁶Kaku-no-gotoku-shite ha, shimori aru-yue, fukuro ni ha irarezu [如此シテハ、シモリアルユヘ、袋ニハ入ラレズ].

Kaku-no-gotoku-shite [此の如き爲ては] means when things have been done like that (i.e., as has just been described in footnotes 4 and 5).

Shimori aru-yue [湿り有るゆえ] means because (the chawan) is wet....

Fukuro ni ha irarezu [袋には��られず] means (the chawan) should not be inserted into its shifuku.

This last admonition is rather vague: is it referring to putting the Shukō-chawan into its shifuku so it can be displayed in the room (either before, or at the conclusion of the temae)? Or doing so, so that it can be put away after the gathering is over?

Here Shibayama’s version clarifies the matter: sore yue hibikite ato ha, fuyu no kai ni fukuro ni iraruru-koto oyoso nakari-shi nari, sono shisai ha hakobi-deru made, kaku no gotoku uruowasete kokoro-tsukaserareshi yue, fukuro ni irete shimeri aru uchi nareba yōsha to nari [夫故ヒヾキテ後ハ、冬ノ會ニ袋ニ入ラルヽコト凡ナカリシ也、其子細ハ運ビ出ル迄、如此ウルホハセテ心遣セラレシ故、袋ニ入レテシメリアル内ナレバ用捨トナリ].

Sore yue hibikite ato ha, fuyu no kai ni fukuro ni iraruru-koto oyoso nakari-shi nari [それゆえ罅きて後は、冬の会に袋に入られること凡そ無かりしなり] means “for that reason, after (the Shukō-chawan) had been cracked, during a winter gathering, inserting (the chawan) into its fukuro was, as a rule, something that was never done.”

Sono shisai ha hakobi-deru made, kaku no gotoku uruowasete kokoro-tsukaserareshi yue [その子細は運び出るまで、 かくのごとくうる負わせて心遣わせられしゆえ] means “as for the details of this (preparation of the chawan), up until the time when it is carried out, because it has been moistened so carefully....”

Fukuro ni irete shimeri aru uchi nareba yōsha to nari [袋に入れて湿りある内なれば用捨となり] means inserting (the chawan) into its bag while it is still wet is something that (the host) should decide upon (for himself).

This clarifies that this is referring to inserting the Shukō-chawan into its shifuku after it has been soaked in water and heated, prior to the commencement of the temae. While the fact that the bowl is wet should probably discourage the host form doing so, ultimately it is up to the host to make this decision -- since displaying the chawan in its shifuku was considered a gesture of respect (so the host would have to decide what was more important).

⁷Atataka-naru toki ha, tokuto-uruowase, nugui-kawakasete fukuro ni irare-shi nari to, Jōō monogatari no yoshi [アタヽカナル時ハ、トクトウルホハセ、ヌグイカハカセテ袋ニ入ラレシ也ト、紹鷗物語ノ由].

Atataka-naru toki [暖かなる時は] means during periods (of the year) when the ambient temperature is warm to hot.

Tokuto-uruowase [篤と潤わせ] means to thoroughly moisten (the Shukō-chawan).

Nugui-kawakasete fukuro ni irare-shi nari [拭い乾かせて袋に入られしなり]: nugui-kawakasete [拭い乾かせて] means wiping (the chawan) until it is completely dry; fukuro ni irare-shi [袋に入られし] means it is inserted into its shifuku.

Jōō monogatari no yoshi [紹鷗物語の由] means this is the point of Jōō’s story.

Here, once again, Shibayama’s version is significantly different, in a way that gives us greater insight into the reasoning that underpins this practice: haru natsu aki ha kan-ki no toki to chigai tokuto-uruowase, nugui-kawakasete, yu wo uchi-ireru mo kega nashi, yue ni fukuro ni irare-shi nari to Jōō monogatari no yoshi [春夏秋ハ寒氣ノ時ト違ヒトクトウルホハセ、ヌグヒカハカセテ、湯ヲ打入レルモケガナシ、故ニ袋ニ入レラレシナリト紹鷗物語ノ由].

Haru natsu aki ha kan-ki no toki to chigai [春夏秋は寒氣の時と違い] means “spring, summer and autumn are different from the cold season.”

Tokuto-uruowase, nugui-kawakasete, yu wo uchi-ireru mo kega nashi [篤と潤わせ、拭い乾かせて、湯を打ち入れる物怪が無し] means soaking it (in warm water)*, wiping it dry, and its being infiltrated by hot water, these things are not expected†.

Yue ni fukuro ni irare-shi nari [故に袋に入れられしなり] means for this reason, (during those seasons) it is inserted into its bag (and displayed in that way when the guests enter the room for the goza).

To Jōō monogatari no yoshi [と紹鷗物語の由] means this was the point of Jōō’s story‡. __________ *Though nothing is said to indicate that this soaking is any different from that performed during the cold season, the fact that the chawan can be wiped dry with a towel and immediately inserted into its shifuku means that this soaking must have been brief enough that water will not have infiltrated into the clay -- thus this “soaking” would seem to have been more of a rinsing (perhaps by a brief submersion in the chakin-darai).

Even today the Sen schools recommend soaking chawan in water before use -- especially red Raku chawan. It is possible that this practice began with Sōtan (who is known to have liked making his utensils -- especially the kiji-tsurube and take-futaoki -- wet before use). ——————————————–———-———————————————— It might be good, at this point, to say something about the chakin-darai, in order to hopefully prevent confusion.

In the modern tea world, the chakin-darai is usually made of bronze or beaten copper. But using this kind of vessel for this purpose was a relatively modern development. The original chakin-darai was made like the mentsū [面桶] (what is usually called the “magemono-kensui” today, for those unfamiliar with the word that was used in Rikyū’s period). Indeed, the word mentsū (which means face-washing bucket) originally referred specifically to the larger one (which was around 7-sun in diameter). The larger mentsū was used when washing the face, while the purpose of the smaller one (the one that is always used as a koboshi today) was to dip water out of the bath (with which to rinse the body) -- both of these things were, therefore, made as bathing utensils, and they were adopted for chanoyu by Jōō because, on account of their ubiquity (they were available even in the most remote mountain hamlets) and low price, they could be replaced each time a gathering was hosted, and so became a symbol of purity.

When Jōō first created the chakai, he took the Shino family’s kō-kai [香會] as his model (and, indeed, his first guests were largely drawn from among the group of people he had met at those incense gatherings). The logistics of the kō-kai were based on the model of the linked-verse gatherings, which usually involved 10 guests (in the renga-kai [連歌會], these guests were divided into two teams of 5 persons each). Furthermore, in the beginning, each guest was served an individual bowl of koicha, and up to two bowls of usucha. This resulted in quite a lot of waste water. The original koboshi used by Jōō was a ceramic piece from Korea called the ō-kame-no-futa [大甕ノ蓋] which, according to the Sōtan nikki [宗湛日記], was 7-sun across the mouth, 4-sun across the bottom, and 3-sun 5-bu deep. The large mentsū held nearly as much water, so Jōō substituted it for the ceramic piece; meanwhile, other people were using Korean bronze basins (again, measuring 7-sun in diameter) for the same purpose.

As Jōō grew older, he began to reduce the number of guests, first to five or six, and later to three. It was at that time that he also began to use the smaller mentsū.

With respect to the smaller bronze koboshi (which are around 5-sun in diameter), those were originally used only on the daisu. In the beginning, the daisu was used when offering tea to the Buddha, so only one bowl of tea was prepared (and the person who had made the tea drank it afterward, so it would not go to waste). Thus the sizes of the various utensils were determined based upon this convention. Later, when the offering of tea was included during more public ceremonies, the custom arose of inviting the most prominent member of the congregation to drink the tea (after it had first been offered on the altar); but still just a single bowl of tea was prepared. Consequently, since there was not much waste water (and not really all that much room available on the ji-ita of the daisu in any case), the smaller receptacle continued to be used. (When larger numbers of people came to be served, the host only prepared tea for the principal guest, while the rest were offered bowls of tea brought out from the preparation area.)

With the appearance of the small rooms, the number of guests was usually restricted to two or three people, so the smaller koboshi would suffice there as well. As a result, the large mentsū came to be used only in the mizuya, as the chakin-darai. Because a new one was used each time, it was always pure, so the chakin could be soaked in it. And because it was made of wood, the chawan could be soaked in it as well, without any fear of damage. But beginning in the nineteenth century, when chanoyu became the province of the business-magnate class (who were buying up the treasures being sold off by the now disenfranchised samurai houses), the neglected larger bronze koboshi came to be repurposed as chakin-darai. And while this would have been distressing to people like Jōō and Rikyū (because these basins had formerly been used as koboshi), apparently the fact that the antique ones were of high quality (and so very expensive as antiques) was reason enough for these wealthy businessmen to use them in their mizuya (which was also now being inspected by the guests, along with everywhere else). Unfortunately, rinsing the chawan in this kind of “chakin-darai” usually damages the basin, and because the basin is metal, there is also a risk that the chawan might be damaged if it strikes against the rim. This, in turn, has lead many chajin to stop soaking the chawan entirely (rendering today’s translation even more of a mystery than it otherwise would have been). —————————————--—–—————————————————— †In other words, the soaking in increasingly hot water, subsequent drying, and so forth, is only done when the weather is cold enough that the shock of pouring hot water into the damaged chawan will be enough to risk damaging it. During the spring, summer, and autumn, the ambient temperature is warm enough that the host does not have to worry about such things, and in consequence he simply eschews the entire preparatory process.

‡In Rikyū’s version of this idea, where the chawan is warmed slowly on the temae-za by first pouring in a half-hishaku of cold water (from the mizusashi), to which hot water is added twice, before the chawan is emptied and then finally warmed with a half-hishaku of water taken directly from the kama, this, too, is done only during the cold season (usually interpreted to mean the ro season -- though it becomes increasingly unnecessary as the spring weather warms).

During Rikyū’s period, the ro-season lasted not quite five months (from sometime between the beginning and the middle of the Tenth Lunar Month, to somewhere around the middle of the Second Month). The furo was used during the remainder of the year (or the ro was handled as if it were a furo).

⁸Yōhen-temmoku [窯變天目].

This is the kind of temmoku shown below -- though it is not clear which of the surviving yōhen-temmoku (if any of them) may have been the chawan in question.

Nowhere is Nambō Sōkei ever mentioned as having owned (or even used) such a chawan* when serving tea in his Shū-un-an -- let alone having had one bestowed upon him by Hideyoshi (see the next footnote). ___________ *The actual temmoku-chawan that was owned by Nambō Sōkei, which he used on one of the kazu-no-dai [數ノ臺], is shown below.

This temmoku is catalogued as a yu-teki temmoku [油滴天目], not a yōhen-temmoku (though in this case, the “oil-drop” spots are not as distinct as in the more commonly recognized examples of this type, hence it was deemed inferior to the others).

⁹Hairyō [拜領].

Hairyō [拜領] means received (from a superior). But not from someone like Rikyū, however: the expression means that this yōhen-temmoku would have been received from someone like Hideyoshi (and that is the person whom the various commentators assume to have been the donor).

Again, the historical evidence for such a relationship between Sōkei and Hideyoshi, where Hideyoshi would have been inclined to bestow such a precious chawan on Sōkei, has never been found*. ___________ *Though there is, of course, the entry in Book One where Sōkei mentions that he assisted Rikyū when the latter served tea to Hideyoshi at Daizenji-yama [大善寺山] by improvising the very first fusube-chanoyu [フスベ茶湯] (“smoky chanoyu”). Virtually all scholars question the authenticity of this account, however (since Sōkei’s name never appers in any of Hideyoshi’s official or personal papers).

¹⁰Guri-guri-dai tomo ni [グリ〰臺トモニ].

Guri-guri lacquer is a variety of carved lacquerware. The object (usually carved form wood) is painted in numerous, alternating coats of red and black lacquer, after which a stylized geometric design (usually resembling some variation on “Ѡ”) is carved into the lacquer with a burin*.

While examples where the outermost coat of lacquer is red are known, in the vast majority of temmoku-dai, kazari-bon, and other furnishings, the outer coat is black, as seen below.

In fact, while temmoku-dai and other objects of this sort were produced from the Ming dynasty onward, they do not seem to have been used (in Japan) until the Edo period.

In Rikyū’s day the plain black lacquered dai seen in the photos that were included under the previous footnote were always preferred†. (The addition of a metal fukurin [覆輪], such as seen in the photo of the yōhen temmoku -- whether made from a ribbon of silver or bronze -- was never seen before the Edo period. The purpose was both to make the dai match the temmoku, as well as to help protect the wooden dai from cracking or splitting from the downward pressure of blending the koicha.) __________ *Guri-guri is said to be an onomatopoeia, resembling the sound that the burin makes when carving this kind of design.

†While all of these dai are essentially identical, in so far as their size and shape and finish is concerned, they were divided into a number of categories based on incidental markings (in red lacquer) that are found on some of them.

In China, these plain black-lacquered dai were made for restaurant use (the conical temmoku bowls were used to serve heated Chinese flavored sake, which usually contained particles of the medicinal herbs that had been steeped in it to give the different brands their unique flavors). Since it was very common for the Chinese to have their gatherings catered, often from several different restaurants (each of which specialized in its own unique dishes), the red markings on the undersides of the dai (and also trays and other lacquered pieces) indicated to which restaurant each dai belonged (in order to avoid disputes between the workers who were dispatched to collect the used dishes the following morning).

These “temmoku-dai” were elevated to the status of great treasures in Japan only on account of their rarety (at most, no more than 40 such dai were ever known to have been imported into Japan, with the number that survived until Rikyū’s day having been reduced to no more than 33 pieces -- according to the Yama-no-ue Sōji ki [山上宗二記]).

¹¹Shimasuji-kuro chawan [嶋筋黒茶碗].

The shimasuji-kuro chawan is mentioned three times in Book Two* of the Nampō Roku (i.e., Rikyū’s kaiki for gatherings hosted between the beginning of the Tenth Lunar Month of Tenshō 14 [天正十四年], 1586, and the end of the Ninth Month of Tenshō 15 [天正十五年], 1587), as well as in the Imai Sōkyū chanoyu nikki [今井宗久茶湯日記] (where, however, Sōkyū refers to it as a kuro-chawan [黒茶ワン] -- which is likely the reason why the Sen family confused this bowl with one of Chōjirō’s pieces) and the Matsuya kai-ki [松屋會記] (where it is called an ima-yaki kuro-chawan [今ヤキ黒茶ワン], though this is qualified by having the ima-yaki kuro-chawan exist before Chōjirō’s black bowls were ever invented). The name does not seem to appear elsewhere.

The shimasuji-kuro chawan were made by Furuta Sōshitsu, and fired at the Seto kiln. They are considered among the first examples of black bowls fired at that kiln (which, as a group, are generally known by the name hiki-dashi-kuro [引出し黒]†, since the color and texture were the result of these bowls being plucked from the kiln prematurely, before the firing was completed, and then cooled rapidly), and so an early inspiration for the black Raku bowls‡. While it is difficult to know when Oribe was sufficiently satisfied with this kind of bowl that he presented one to Rikyū, the kaki-ire that was appended to this line suggests that this was in the autumn of 1573 (Tenshō gannen [天正元年]) -- since Rikyū chose to use it during his kuchi-kiri chakai that year (which would have been celebrated around the 5th of November, 1573, according to the proleptic Gregorian calendar -- at the beginning of the Tenth Lunar Month).

Three bowls from this early period survived, and they were known variously as shimasuji-kuro and Tenshō-kuro [天正黒] -- the latter name because they were produced in the first year of the Tenshō era.

The shimasuji-kuro name, however, is a little more difficult to explain. The majority opinion seems to be that the surface texture of these bowls resembled the folk pottery that was occasionally brought from the islands between Japan and the continent during the sixteenth century (which was known as shima-mono [嶋物], “island-ware”), while suji [筋] refers to the clearly visible horizontal lines on the sides of the bowls below the mouth (which were the result of the way the bowls were thrown on a wheel).

While asymmetrical (though not nearly as distorted as Oribe’s later bowls -- which were called kutsu-gata chawan [沓形茶碗], because they resembled the oblong mouths of lacquered wooden shoes), the diameter of these bowls is approximately 5-sun 2-bu, and they are around 2-sun 3-bu high. Some years earlier, Rikyū had sold the Shukō-chawan (whose measurements these black bowls replicated) to the military man Miyoshi Yoshikata [三好義賢; 1526 ~ 1562] (he is also known as Miyoshi Jikkyū [三好實休])**, who had been one of Jōō’s prominent disciples; and it may have been to memorialize the Shukō bowl (or in some way, replace it) that Oribe made this bowl for Rikyū. (The fact that Rikyū made frequent use of it for the next several years -- on occasions which mirror those on which he earlier had used the Shukō-chawan -- suggests that it pleased him, perhaps through the muscle-memory that this black bowl retrieved from the depths of Rikyū’s mind††.)

In the remarks that follow, there seems to be some confusion, in the mind of the author of this entry, between this bowl and the (much) later black Raku bowls‡‡.

While this line is usually read as if it were talking about one specific chawan, it appears (according to the last line of this kaki-ire -- see footnote 16) that there were at least two nearly identical bowls of this sort produced by Furuta Sōshitsu at the same time***. The only real difference between them was that one was slightly larger than the other, and it was the smaller of the two (the one that better conformed to the measurements of the Shukō-chawan) that Oribe presented to Rikyū). __________ *Tanaka Senshō, in his commentary on this line, states that the shimasuji-kuro chawan is also mentioned in the Rikyū hyakkai-ki [利休百會記], in an entry dated the sixteenth day of the Twelfth Month. However, no such entry exists in either the version of the Rikyū hyakkai-ki that was included in the Sadō ko-ten zen-shū [茶道古典全集] collection (this text is included in volume 6), nor in the somewhat abbreviated version of the Rikyū hyakkai-ki that was published, as the Hyaku suki-dōgu kyaku narabi ni kai-ki [百数寄道具客幷會記], in book 6 of the Rikyū chanoyu sho [利休茶湯書] (1680).

After this (erroneous) citation, Tanaka continues (quoting from the 1949 edition of the Sadō jiten [茶道辞典], by Sue Sōkō [末宗廣; 1889 ~ 1977 ]): “Meibutsu chawan. During the Tenshō era, Rikyū ordered it from a potter in Seto, and it became known as Tenshō-kuro or shimasuji-kuro. But when Rikyū finally lost his fondness for it, he gave it to Nambō. It is so called because of the several lines on its exterior. It is currently one of the treasures of the Asabuki family.”

The above constitutes the entirety of Tanaka’s comments on the Shimasuji-chawan.

†Hiki-dashi-kuro [引出し黒] means that these black bowls were plucked from the kiln in the middle of the firing process, which allowed them to cool rapidly. The result was not only the black color, but the interesting surface texture that sudden cooling of the molten glaze produced.

It appears that Furuta Sōshitsu was inspired to attempt this by the fact that, at different points in the firing, the kiln-master would open one of the small windows in the side of the kiln chamber and pluck out one of the pieces that were firing, to ascertain how far along the burning process had progressed (since there was nothing technologically comparable to the modern-day firing cones, which inform the potter of the temperature within the kiln). While these pieces were usually discarded, Oribe was fascinated with the way the rapid cooling effected the glaze color and texture, and subsequently experimented with various ways to cool the pieces even faster (by burying them in a box of damp sawdust, or dropping them into a bucket of water).

‡Aka-Raku [赤樂] bowls first appeared circa the beginning of 1586, with the black bowls perhaps a year later. The immediate inspiration for the red bowls had been a honey-colored Seto chawan that Kitamuki Dōchin presented to Rikyū as a parting gift (with the admonishment that Rikyū thenceforth concentrate his efforts on wabi-no-chanoyu, and give up any idea of practicing tea in the shoin-daisu setting). This is the chawan shown below.

Rikyū sold this bowl (because he needed the money), but retained its square shape and red-brown color in his memory. Four decades later, when circumstances permitted, Rikyū asked the Korean potter known as Chōjirō [長次郎] to make a copy of that bowl for him.

The kuro-chawan [黒茶碗] were inspired by Oribe's hiki-dashi-kuro bowls (of which the shimasuji-kuro were one example).

**Miyoshi Yasunaga [三好康長; his dates of birth and death are unknown] subsequently presented this chawan to Nobunaga, when he attempted to make peace between the Oda and Miyoshi clans. The Shukō-chawan became one of Nobunaga’s greatest personal treasures (and he was using it to serve tea to his page-lover Mori Ranmaru [森蘭丸; 1565 ~ 1582] when Akechi Mitsuhide attacked the Honnō-ji in Kyōto, forcing Nobunaga's seppuku).

††While the same size as the Shukō-chawan, the straighter sides of Sōshitsu’s black bowl makes it easier to use when preparing koicha. This rather square profile would later appear, of course, in the Raku chawan.

‡‡The implication being that these bowls were early examples of Raku-yaki (even though the earliest Raku-yaki chawan were not created until 1586 -- and they were red bowls).

***Even today, several authentic bowls of this type, made by Oribe himself, are known. According to Tanaka’s commentary, the one that was most likely owned by Rikyū is now in the private collection assembled by the business magnate Asabuki Eiji [朝吹英二; 1849 ~ 1918]. This bowl has never been exhibited, and there are no known photos of it. The other, which is the one shown in the photo, currently resides in the collection of the Tajimi City Mino Ware Museum [多治見市美濃焼ミュージ].

In addition to these two (known) “honka” pieces, numerous copies (of varying quality) have been produced by potters at the Seto kilns from the early Edo period down to the present day. That said, it is relatively rare for copies to be true hiki-dashi-kuro (due to the number of pieces that are lost when this technique of plucking pieces out from the kiln and subjecting them to rapid cooling is employed): most reproductions are made using black glazes that have been formulated to produce the desired color and surface texture, while yet allowed to cool naturally with the kiln.

¹²Kore ha Kyū-kō yori tamawaru [コレハ休公ヨリ玉ハル].

Kore ha Kyū-kō yori tamawaru [これは休公より給わる] means this (shimasuji-kuro chawan) was given (to Nambō Sōkei) by Lord Rikyū.

Again, notice should be taken of the way Rikyū is designated here, since this form is only found in Sen family documents.

¹³Tenshō gannen kuchi-kiri no toki dekita no nari [天正元年口切ノ時出來ノナリ].

As mentioned above, the Tenshō gannen kuchi-kiri [天正元年口切] would have been celebrated in early November of 1573.

Tenshō gannen kuchi-kiri no toki dekita [天正元年口切の時出來た] means (the shimasuji-kuro chawan) was finished around the time of the kuchi-kiri in the first year of the Tenshō era.

The language (specifically the use of the word dekita [出來た]) seems to suggest that the author of this entry believed that Rikyū had personally ordered (and possibly designed) this chawan. Since the only potter with whom Rikyū was known to have had such a relationship was Chōjirō, the implication is that this bowl was commissioned from Chōjirō (which would make it an early example of Raku-yaki). It is because of this entry (and its ramifications) that the history of the Raku family became so confused*. __________ *While Chōjirō was an ethnic Korean, he does not seem to have been a citizen of Sakai. As a master in the production of low-fired unglazed ware, he may have been recruited (from Korea) specifically to produce the decorative roof sculptures that were placed on the ends of the ridge beams in Hideyoshi’s Juraku-tei [聚樂第] palace. Rikyū, therefore, could not have met Chōjirō before 1585, at the earliest; but it was not until 1586, after inspecting Chōjirō’s work, and probably talking with him about pottery, that he ventured to ask Chōjirō to try to make a chawan (while the usual color of the clay that was used for this kind of ware was generally gray-black, the natural clay also featured red and white variants; and it was the red form that Rikyū asked Chōjirō to use, covered with a thin lead glaze to make it waterproof: the first kuro-chawan were also made from the same red clay).

It seems that it was only after Chōjirō had been working for some time that it was noticed that natural black rocks from the Kamo gawa, when used to build the kiln, would sometimes liquefy into runs of black glaze. After confirming this, the idea of attempting to replicate Furuta Sōshitsu’s hiki-dashi-kuro bowls occurred to Rikyū, and so the black chawan came into existence later.

¹⁴Atarashiki-mono nare-domo, Kyū koto-no-hoka deki-yoshi tote tamawari [アタラシキ物ナレドモ、休コトノ外出來ヨシトテ玉ハリ].

Atarashiki-mono nare-domo [新しい物なれども] means “even though this (shimasuji-kuro chawan) was a newly(-made) piece....”

Kyū koto-no-hoka deki-yoshi tote tamawari [休殊の外出來よしとて給わり] means “Rikyū, because he (judged) that (this chawan) was an especially successful (piece), gave it (to Sōkei).”

¹⁵Tabi-tabi o-cha wo mo age, sono fuyu haru, ō-kata hi-nichi kono chawan ni te taterareshi, hizō nari-shi nari [度〻御茶ヲモ上ゲ、其冬春、大方日〻コノ茶碗ニテタテラレシ、秘藏ナリシ也].

Tabi-tabi o-cha wo mo age [度々お茶をも上げ] means (using this chawan) tea was frequently offered (to his guests).

Sono fuyu haru, ō-kata hi-nichi kono chawan ni te taterareshi [その冬春、大方日々この茶碗にて立てられし] means during that winter and (the subsequent) spring, (Rikyū) used this chawan to prepare tea most days*.

Hizō nari-shi nari [秘藏なりしなり] means this (chawan) was truly a treasure†. __________ *In other words, he used the shimasuji-kuro chawan almost every time he served tea during the winter of 1573~4, and the following spring.

While the relative shallowness of this chawan might make us wonder why it was used during the cold season, we must remember that the Shukō-chawan was actually a very representative bowl from the early sixteenth century, so people of that time would not have found anything odd about this. (This is also why it was said that the kama should be heated to a strong boil when serving tea during the cold months -- because the usual shape of the chawan would allow the tea to cool a little before it actually reached the guests’ mouths.)

The large size of this chawan, and its consequent weight (and the warmth that such a bowl would preserve) were probably among its most attractive features for Rikyū. And, of course, the fact that the black color would make the koicha seem to glow was another plus.

†The point of this rather exaggerated way of stating the matter seems to be to reinforce the idea that Rikyū did not give the shimasuji-kuro chawan to Nambō Sōkei because he disliked it (which would have been the usual reason why a chajin of the Edo period would have dispossessed himself of something), but in order to share the pleasure of the experience of serving tea with it with his friend Sōkei.

¹⁶Kore-yori ōburi no ha, Furuta Oribe ni tsukawasare-shi nari [コレヨリ大フリノハ、古田織部ニ被遣シ也].

Kore-yori ōburi no ha [これより大振りのは] means “with respect to the one that was larger than this (of the several shimasuji-kuro chawan)....”

Furuta Oribe ni tsukawasare-shi nari [古田織部に遣せられしなり] means “(it) was passed over to Furuta Oribe.”