#ruth 1853

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

I have been following your reading of Ruth with interest; when I read it myself the main impression was that of relentless misery. Certainly, characters were kind and nature was beautiful, but Ruth's life overall was too sad for me, even if it shone forth with her sweetness, innocence, generosity, and mercifulness.

With time I have come to a more... analytical approach if you will. I feel like The Problem With RuthTM is that Gaskell is serving on her plate more than she can chew. A good part of the story feels like an homage to The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, with the pointing out of double standards, the protection of children, forgiveness of those who made your life miserable, etc; but it is also trying to include commentary on single motherhood, religious hypocrisy, social cruelty... and that kind of corners her into writing Ruth, the fallen woman, as too angelic, too perfect, too innocent, all the time, and that gets a bit grating after a while. Even Fanny Price has her moments of jealousy or anger in her inner thoughts! It also corners her into... having to kill her off in the end? Even if it isn't a horrible death in disgrace, and she is an exalted character at the end of the story for her virtues, it still sort of carries the idea that she cannot "come back" from the mistake of her youth.

Ruth does become too good, and I wished that Gaskell had been able to show her as a more complicated character--would she have been worthy of redemption if she hadn't been perfectly good after she repented of her major sin?--but I was able to forgive it somewhat because Ruth is set up as innocent and trusting from the beginning, and Gaskell points out that her present-focused personality is both the source of her sin (not thinking about the consequences) and her later saintliness (letting go of the past and not thinking of herself). I didn't think it made her an annoying character, because that portion of the story was less about her and more about how other people react to her--here's a community that loves her because she seems perfect, so how does that change when they find out her deep, dark secret?

I don't think Gaskell was trying to do too much. I think the story's incredibly focused because everything centers around one theme: sin. How do we fall into it? How do we rationalize it? How do we hide it? How do we redeem ourselves from it? How do we judge others for it? Almost every character has to grapple directly with some major sin they commit and the fallout from it.

It's why I don't agree that this is at all a Tenant redux. Bronte was writing directly about gender and marriage and critiquing the societal structures surrounding both. Gaskell centers the story on Ruth's fall not to comment on gender or sex, but to explore sin, and this happens to be one of the most severely-judged sins in her society. Even if the surface situation seems similar--a woman pretending to be a widow to hide a shameful past--their realities and personalities are exact opposites, and the stories are exploring very different things.

As for the ending, I also heartily wish that Gaskell had come up with a happier ending for Ruth. I was so disappointed when I realized Gaskell was going with the expected cliche. However, I don't think Gaskell was trying to say there was no redemption for Ruth. She had been thoroughly redeemed in the eyes of the town. The death read to me as, "Well, the story has to end somewhere, and this provides the easiest ending point."

Actually, aside from my disappointment at the chosen path, I think this is one of Gaskell's best endings, because it's thematically and structurally coherent. Ruth going to care for Mr. Bellingham at the risk of her own life is a mirror to Mr. Bellingham abandoning her after his first illness. The first time, she was shut out from caring for him; the second time, she comes when no one else will dare. After his first illness, he proves that he doesn't love her by abandoning her for his own convenience; during the second, she proves what love truly is by coming at risk to her own life. (Also, the fact that the one servant who stayed with him was the boy he'd rescued from the river at their second meeting--my heart!). Ruth has retained her innocence and grown into someone courageous, while Bellingham with his worldly prosperity has magnified his faults and fallen deeper into sin. Ruth has become someone so selfless that she gives her own life, while Bellingham is so selfish that he expects to be commended for merely giving money to a child he's abandoned for twelve years. (Gentle Mr. Benson throwing him out of the house was almost enough to make me forgive the rest of the ending).

The callbacks and mirrors made for a much tighter ending than Gaskell usually manages--even if I was disappointed in the choice, it didn't come out of nowhere, the way, for instance, that some parts of Mary Barton do. It made it satisfying to me as an overall story, so I can forgive a lot of smaller flaws along the way.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the interesting excursus I must force myself not to explore right now XD is about Elaine Showalter's A Literature of their Own (1977), one of the most important/foundational works of feminist literary criticism in the English speaking world of its time. It is, in general broad strokes, a book that seeks to identify and characterize a tradition or traditions of the women's novel in Britain, as separate from that of men.

It's an interesting text in terms of the ways in which it identifies the strategies used in general Victorian culture to put down women's writers, the weaponization of Austen to put women writers "in their place" (cfr. that exchange of letters between Charlotte Brontë and G.H. Lewes that is used to this day to dunk on CB for disliking Austen's novels), the ways in which women themselves reinforced this (cfr. George Eliot's extreme reluctance to acknowledge genius in women that weren't herself) etc.* And in this way it accidentally illuminates A) how much of persistent criticism of Gaskell is just a continuation and rewarming of those same prejudices B) how much the establishment of the narrative of the great female novelist as a sort of Romantic genius/tortured artist -comically owing in no small degree to Gaskell's biography of Charlotte Brontë- made of Gaskell a safe scapegoat, and significantly drove readings of her as inferior and a failed artist.

Showalter uses as an example of certain insidious practices of certain male critics, a passage from J.M. Ludlow's review of Gaskell's Ruth (1853):

"Now, if we consider the novel to be the picture of human life in a pathetic, or as some might prefer the expression, in a sympathetic form, that is to say, addressed to human feeling, rather than to human taste, judgement, or reason, there seem nothing paradoxical in the view, that women are called to the mastery of this peculiar field of literature. We know, all of us, that if man is the head of humanity, woman is its heart; and as soon as education has rendered her ordinarily capable of expressing feeling in written words, why should we be surprised to find that her words come more home to us than those of me, where feeling is chiefly concerned?"

If you have seen me rant and complain these past few months about 20th century critics of Gaskell, you cannot fail to recognize here the same touchstones of discourse. The target has just been displaced from "all women are unintelligent and sentimental" to "all married women with children are unintelligent and sentimental".

Things get more interesting when Deirdre D'Albertis in Dissembling Fictions, one of the more cited books on Gaskell, takes Showalter to task (with Gilbert and Gubar, the authors of The Madwoman in the Attic) for more or less acritically subscribing to Virginia Woolf's conception of a woman's tradition of writing as both being evolutionary (meaning later works are better than earlier works) and pyramidal (in order for there to exist geniuses like Austen and Eliot, there must be lesser authors that provide the bases for those pinnacles of achievement). And, you know, passages like this from Showalter herself, at the very opening of the acknowledgements section of her book:

"In the Atlas of the English novel, women's territory is usually depicted as desert bounded by mountains on four sides: the Austen peaks, the Brontë cliffs, the Eliot range, and the Woolf hills. This book is an attempt to fill in the terrain between these literary landmarks and to construct a more reliable map from which to explore the achievements of English women novelists."

seem to entirely justify it.

This is, however, not yet the twist. D'Albertis' argument about how the tradition of feminist literary criticism has been extremely uncomfortable with Gaskell because of the ways in which she doesn't fit the molds of the Woman WriterTM is functionally placed in support of the main thesis of her work, which isn't that Gaskell is actually good. No. The thesis is that instead of being bad on accident, she's bad on purpose and a consummate liar. No, I'm not joking. The argument is that Gaskell's fiction is literary broken and the endings such failures because she's questioning genre and the uses of genre from masculine authors, but that she covers this protest with lies to protect her respectability.

While I cannot prove that this assertion of the self evident character of Gaskell's fiction as failure specially in closing is due to D'Albertis belonging to the Marxist critical tradition through Williams and Kettle -because both are referenced, but not extensively-, there's something very ironic to me in these layers of discourse in which the basic, unproven assumption (that Gaskell's fiction is actually not good) remains unquestioned, even when everything else is.

God forbid Elizabeth Gaskell writes anything.

*reasons why I cannot forgive Chesterton's The Victorian Age in Literature (1913). Chesterton is the kind of author that is prevented from becoming insufferably pedantic only because he's clever, well read and witty (much like Oscar Wilde), but when it comes to women writers this book is so insanely superficial and flippant he comes across as an unmitigated ass. The author of The Man Who Was Thursday (an excellent novel, btw) comparing Victorian women writers with headless chickens because of their unaustenian flights of fancy IS RICH.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

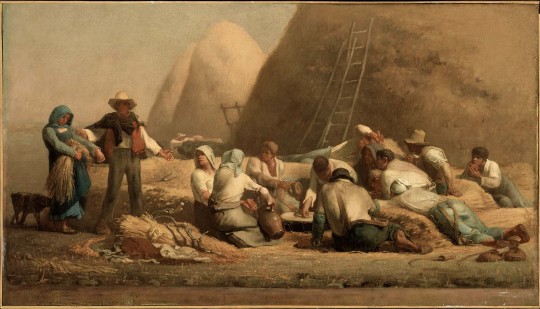

HARVESTERS RESTING (Ruth and Boaz), 1850 by JEAN-FRANÇOIS MILLET

Dirty and exhausted, harvesters and their tools are strewn around them as they rest before piles of golden grain. To the left of the group, a man introduces a woman.

Originally, MILLET'S inspiration for the piece came from the Bible's story of the Widow, RUTH, who encounters the landowner, BOAZ, a family friend and the man who would later become her husband, while out working in the fields. At his 1853 Salon, MILLET displayed the piece under the title "HARVESTERS RESTING."

The focus on the harvesters, and the grain piles behind them, allows for BOAZ and RUTH to be seen as secondary figures to the focal point. What we’ve seen here is not a romantic Old Testament narrative of faith connecting two people, but rather a modern group of hot, dusty field laborers resting after a day of work.

RUTH'S face is downcast shyly, and BOAZ, acting as intermediary, visually joining her figure with the group field workers. Thus, MILLET brings into focus the common laborer's centrality in history and scripture.

#harvesters resting#ruth and boaz#jean francois millet#realism#realism painting#realist painter#realist painting#realist#realism artwork

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading Ruth (1853) by Elizabeth Gaskell.

Excerpts:

At any rate, it is unwise to expect gratitude. What do you expect not indifference or gratitude? It is better not to expect or calculate consequences. The longer I live, the more fully I see that. Let us try simply to do right actions, without thinking of the feelings they are to call out in others. We know that no holy or self denying effort can fall to the ground in vein and useless; but the sweep of eternity is large, and God alone knows when the effect is to be produced. We are trying to do right now, and to feel right; don’t let us perplex ourselves with endeavoring to map out how she should feel, or how she should show her feelings.

Those summer mornings were happy, for she was learning neither to look backwards nor forwards, but to live faithfully and earnestly in the present. p145

To be continued.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Birthdays 4.27

Beer Birthdays

Adam Gettelman (1847)

John Maier (1955)

Gwen Conley (1966)

Latiesha Cook (2004)

Five Favorite Birthdays

Rogers Hornsby; St. Louis Cardinals 2B (1896)

Walter Lantz; animator, Woody Woodpecker creator (1900)

George Petty; artist, illustrator (1894)

Kate Pierson; rock keyboardist, singer (1948)

Sergei Prokofiev; Russian composer (1891)

Famous Birthdays

Frank Abagnale Jr.; security consultant & criminal (1948)

Philip Abelson; physicist (1913)

Irving Adler; mathematician 1913)

Anouk Aimee; actor (1932)

Earl Anthony; bowler (1938)

Ludwig Bemelmans; Italian-American author & illustrator (1898)

Judy Carne; comedian (1939)

Wallace Carothers; chemist & inventor of nylon (1896)

Jenna Coleman; English actress (1986)

Cecil Day-Lewis; Anglo-Irish poet & author (1904)

Sandy Dennis; actor (1937)

Sheena Easton; pop singer (1959)

Charles Emanuel I; king of Sardinia (1701)

Ace Frehley; rock musician (1951)

Edward Gibbon; historian, writer (1737)

Ruth Glick; author (1942)

Ulysses S. Grant; 18th U.S. President (1822)

Pete Ham; rock musician (1947)

Sally Hawkins; English actress (1976)

Casey Kasem; DJ (1932)

Jim Keltner; rock drummer (1942)

Theodor Kittelsen; Norwegian painter & illustrator (1857)

Jack Klugman; actor (1922)

Jules Lemaître; French playwright (1853)

Lizzo; singer and rapper (1988)

Samuel F.B. Morse; code inventor (1791)

Ann Peebles; soul singer-songwriter (1947)

Dave Peel; rock musician (1947)

Alan Reynolds; English painter (1926)

Enos Slaughter; St. Louis Cardinals RF (1916)

Herbert Spencer; English philosopher (1820)

James Samuel Stone; British historian (1852)

Yoshihiro Togashi; Japanese illustrator (1966)

Friedrich von Flotow; German composer (1812)

August Wilson; playwright (1945)

Mary Wollstonecraft; writer, feminist (1759)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Mary Ruth Manning (1853-1930) pintora irlandesa.

Nació en Dublín, en el seno de una familia adinerada. Su padre, Robert, era ingeniero y se casó con su prima segunda Susanna Gibson, con quien tuvo siete hijos.

Aparte de un período en el que vivió en Hampstead, Londres, entre 1889 y 1892, vivió en la casa familiar de Ely Place desde 1880.

Una de sus hermanas, Georgina Manning (alias Geraldine), fue una sufragista que destrozó un busto de John Redmond en una exposición de la Royal Hibernian Academy en 1913.

Ni Mary ni sus hermanas se casaron y vivieron en Ely Place hasta después de la muerte de su padre, y luego en Winton Road, Lesson Park.

Estudió en París en la década de 1870 con Louise Catherine Breslau y Sarah Purser.

Trabajó principalmente en óleo y acuarela.

De 1880 a 1892, su trabajo fue exhibido por la Royal Birmingham Society of Artists, la Walker Art Gallery, la Royal Hibernian Academy y en Bruselas.

Es conocida por su influencia en varias artistas irlandesas de la época. Ella y sus hermanas impartían lecciones de arte en un estudio para mujeres jóvenes que podían ingresar a la RHA, a muchas de las cuales animó a estudiar en París. Entre los artistas a los que enseñó e influyó se encuentran Mary Swanzy y Mainie Jellett.

Su enseñanza ocupó la mayor parte de su tiempo, lo que la llevó a exponer su propio trabajo con poca frecuencia.

Se convirtió en miembro del Dublin Sketching Club en 1885.

Murió en la casa familiar.

0 notes

Text

I’m making a chronological list of things I have seen/want to see! Any suggestions and add ons are awesome! I hope to have a comprehensive list spanning as much history as possible. I prefer series and miniseries to movies but I’ll take it all!!!! (Eventually i will add links to pages for info on the ones I’ve chosen and also add regional contexts. All dates are starting dates and there is much overlap!)

Also don’t judge me, I can’t do subtitles 😂 i spend all of my time obsessing over the words that i miss the action

I’ll mark what I’ve seen with an x

• Slave of Dreams (biblical Joseph)(1901 BC)

• The Red Tent (1700 BC)

• Tut (1332 BC)

• The Prince of Egypt (biblical Moses) (1290 BC) x

• The Story of Ruth (1220 BC) (biblical Ruth) x

• Helen of Troy (1200 BC) (Greek legend) x

• Iphigenia (1200 BC) (Greek legend) x

• The Trojan Women (1150 BC) (Greek legend)

• The Odyssey (1150 BC) (Greek legend) x

• King David (1140 BC) (biblical David)

• One Night With the King (biblical Esther) (518 BC) x

• The 300 Spartans (480 BC) x

• The Cleopatras (305 BC)

• Alexander (283 BC)

• Ancient Rome: The Rise and Fall of an Empire (146 BC)

• Julius Caesar (100 BC) x

• Spartacus (73 BC) x

• Rome (52 BC)

• Imperium: Augustus (49 BC)

• Cleopatra (48 BC) x

• Empire (44 BC)

• I, Claudius (24 BC) x

• (Life of Biblical Jesus) (1 AD) x

• Nero (41)

• Britannia (43)

• Boudica (60)

• Decline of an Empire (307)

• Agora (360)

• (Arthurian Legend) (5th-6th centuries) x

• Attila (406)

• Dark Kingdom: The Dragon King: Ring of the Nibelungs (Volsunga Saga) (450) x

• Tristan & Isolde (Post Arthurian Legend) (6th Century)

• Prince of Jutland (6th Century)

• Redbad (680)

• Vikings (793)

• The Gaelic King (800)

• The Last Kingdom (866)

• A Viking Saga (870)

• The 13th Warrior (922) x

• Valhalla Rising (1000)

• Vikings: Valhalla (1002)

• The Vinland Saga (1013)

• El Cid (1043)

• 1066 The Battle for Middle Earth (1066)

• The Pillars of the Earth (1123)

• Barbarossa (1176)

• Kingdom of Heaven (1183) x

• The Lion in Winter (1183)

• Ivanhoe (1192) x

• The Pagan King (13th century)

• Knightfall (1291)

• Braveheart (1296) x

• Outlaw King (1304)

• Robert the Bruce (1306)

• The Name of the Rose (1327)

• World Without End (1327)

• Black Death (1348)

• The Reckoning (1380)

• The King (1403)

• Medici (1409)

• The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc (1429)

• The Hollow Crown (1455)

• The White Queen (1464) x

• Maximilian (1477)

• The White Princess (1485)

• The Borgias (1490)

• The Spanish Princess (1501)

• Luther (1505)

• The Tudors (1516) x

• The Other Boleyn Girl (1521)

• The Headsman (1525)

• A Man For All Seasons (1529)

• Wolf Hall (1529)

• The Serpent Queen (1533)

• Lady Jane (1553)

• Reign (1557) x

• Mary, Queen of Scots (1561)

• Dangerous Beauty (1562)

• Elizabeth I (1579)

• The Merchant of Venice (1596)

• Shogun (1600)

• Gunpowder (1605)

• Mary & George (1612)

• Jamestown (1619)

• Silence (1630)

• The Devil's Whore (1638)

• To Kill a King (1648)

• Charles II: The Power and The Passion (1649)

• Versailles (1667)

• A Little Chaos (1682)

• The Crucible (1692) x

• Rob Roy (1713) x

• Black Sails (1715)

• The Great (1745)

• The History of Tom Jones: a Foundling (1749)

• Casanova (1753)

• Roots (1760’s)

• Belle (1761)

• Harlots (1763)

• Sons of Liberty (1765)

• John Adams (1770)

• The Duchess (1774)

• Marie Antoinette (1774) x

• Hamilton (1775) x

• Franklin (1776)

• Poldark (1783)

• A Respectable Trade (1787)

• Banished (1787)

• Northanger Abbey (1798)

• Sense and Sensibility (early 19th century)

• Pride and Prejudice (early 19th century) x

• Mansfield Park (early 19th century)

• Emma (early 19th century)

• Persuasion (early 19th century)

• Bridgerton (1813) x

• Belgravia (1815)

• Sanditon (1817)

• Gentleman Jack (1832)

• Harriet (1849)

• North and South (1851)

• The Empress (1853)

• The Luminaries (1860)

• Far from the Madding Crowd (1870)

• Deadwood (1870’s)

• The Buccaneers (1870’s)

• Victoria (1876)

• The Gilded Age (1882) x

• Miss Scarlet and the Duke (1882)

• The Knick (1900)

• Forsyte Saga (1906)

• Downton Abbey (1912) x

• Boardwalk Empire (1920)

• Black Narcissus (1939)

• Blitz (1940)

• The Crown (1947)

• A Suitable Boy (1951)

• Call the Midwife (1957)

• Mad Men (1960’s)

• Rustin (1963)

• Small Things Like These (1985)

#historical#historical fiction#historical dramas#historical timeline#a history in movies#a history in film#a history in tv#historical list#world history#historical queue

1 note

·

View note

Text

Родословная Стивена Кинга. ✅ Стивен Эдвин Кинг (англ. Stephen Edwin King; род. 21 сентября 1947, Портленд, Мэн, США) — американский писатель, работающий в разнообразных жанрах, включая ужасы, триллер, фантастику, фэнтези, мистику, драму, детектив, получил прозвище «Король ужасов». Продано более 350 миллионов экземпляров его книг, по которым было снято множество художественных фильмов и сериалов, телевизионных постановок, а также нарисованы различные комиксы. Кинг опубликовал 60 романов, в том числе семь под псевдонимом Ричард Бахман, и 5 научно-популярных книг. Он написал около 200 рассказов, большинство из которых были собраны в девять авторских сборников. Действие многих произведений Кинга происходит в его родном штате Мэн. Мать писателя, Нелли Рут Пиллсбери (англ. Nellie Ruth Pillsbury), была четвёртым ребёнком из восьми в семье Гая Герберта и Нелли Уэстон Фогг Пиллсбери. Она родилась 3 февраля 1913 года в городе Скарборо. Её личная жизнь долгое время не складывалась. Она дважды выходила замуж. 23 июля 1939 года сочеталась браком с капитаном торгового флота Дональдом Эдвардом Кингом. Отец писателя родился 11 мая 1914 года в семье Уильяма и Хелен Бауден Кинг в Перу (Индиана). Врачи поставили Рут диагноз бесплодие, и в 1945 году пара усыновила новорождённого Дэвида Виктора. Через два года, 21 сентября 1947 года в Портленде, несмотря на предполагаемую болезнь, в семье родился мальчик Стивен. Отец: Дональд Эдвин Поллок, псевдоним Кинг Мать: Нелли Рут Пиллсбери 📃 Поколенная роспись рода Кинг: 👫 1-е поколение 1. Стивен Кинг (1947–) 👫 2-е поколение 2. Дональд Эдвин Поллок, псевдоним Кинг (1914–1980) 3. Нелли Рут Пиллсбери (1913–1973) 👫 3-е поколение 4. Уильям Эдвин Поллок (1888–1918) 5. Хелен Алетия Боуден (1897–1968) 6. Гай Герберт Пиллсбери (1876–1965) 7. Нелли Вестерн Фогг (ок. 1877–1963) 👫 4-е поколение 8. Дэвид Риттенхаус Поллок (1857–1938) 9. Элизабет Дэвис (1860–1937) 10. Уильям Ф. Боуден (1860–1941) 11. Гарриет Р. «Хэтти» Клир (1870–1947) 12. Говард Ливитт Пиллсбери (1849–1926) 13. Сесилия Медиа Фосс (1853–1924) 14. Артур Дж. Фогг (1842–1908) 15. Сьюзен Энн Картер (1846–1907) 👫 5-е поколение 16. Джон Поллок (1828–1907) 17. Розанна Мария Риттенхаус (ок. 1828–1890) 18. Натан Дэвис (1822–1904). 19. Марта Мастон (1825–1910) 20. Уильям Т. Боуден (1828–1904) 21. Полли Энн Мэнесс (1833–1907) 22. Сэмюэл С. Клир (1847–1914) 23. Ловина Николс (1842–1917) 24. Чарльз Карл Пиллсбери (1810–1893) 25. Юнис М. Уотерхаус (1810–1871) 26. Джозеф Фосс (ок. 1802–1872) 27. Сьюзен Г. Робинсон (ок. 1816–1875) 28. Аса Рэнд Фогг (1812–1894) 29. Элизабет Х. Бабб (–ок. 1850) 30. Дэниел Картер (ок. 1811–) 31. Мэри Энн Месерв (около 1815–) 👫 6-е поколение 32. Джеймс Поллок (ок. 1781–стр. 1860) 33. Мэри ��тэнли (ок. 1785–1860) 34. Тиглман Риттенхаус (ок. 1800–1866) 35. Пермелия Тулли (ок. 1800–1834) 40. Энох Боуден (ок. 1801–1886) 41. Делайла Хьюз (ок. 1802–) 42. Элси Манесс (c1806–p1880) 43. Элизабет —-— (ок. 1809–ок. 1880) 48. Джонатан Пиллсбери (1762–1833) 49. Шуа Милликен (ок. 1776–1864) 50. Ричард Уотерхаус (1782–1868) 51. Элизабет «Бетси» Смит (1782–1871) 56. Джордж Фогг (1784–1863) 57. Джоанна Фогг (ок. 1780–1861) 62. Эндрю Месерв 63. Юнис Бернелл 👫 7-е поколение 96. Дэвид Пиллсбери (1737–) 97. Анна —--- 98. Джеремайя Милликен 99. Сара Лорд 100. Натаниэль Уотерхаус (1756–1845) 101. Элизабет Кейн (1758–1840) 112. Джеремайя Фогг (1744–1815) 113. Мэри Уоррен (ок. 1742–1800) 124. Джордж Мезерв (1740–) 125. Сюзанна Стэйплс 126. Джон Бернелл 127. Лидия Уитни 👫 8-е поколение 192. Джозайя Пиллсбери (1686–стр. 1761) 193. Сара Келли 198. Авраам Лорд 199. Фиби Херд 200. Джозеф Уотерхаус (1711–1796) 201. Мэри Либби (–1756) 224. Сэмюэл Фогг 225. Рэйчел Маринер (1724–) 248. Джон Месерв (1708–1762) 249. Джемайма Хаббард (1712–1768) 254. Абель Уитни 255. Мэри —--- 👫 9-е поколение 384. Джоб Пиллсбери (1643–1716) 385. Кэтрин Гаветт (–1718) 398. Джеймс Херд (1696–) 399. Мэри Робертс (1701–) 400. Тимоти Уотерхаус (ок. 1675–) 401. Рут Мозес (–1769) 450. Джон Маринер 451. Сара Сойер (1683–1724) 496. Клемент Мезерв (ок. 1679–1746). 497. Элизабет Джонс 👫 10-е поколение 768. Уильям Пиллсбери (ок. 1606–1686) 769. Дороти Кросби (–стр. 1686) 796. Джон Херд (ок. 1667–) 797. Фиби Литтлфилд (ок. 1669–1697) 798. Хэтевил Робертс (–c1734/1735). 799. Лидия Робертс (–стр. 1719) 800. Ричард Уотерхаус (–ок. 1718) 801. Сара Ферналд (ок. 1640–ок. 1701) 802. Аарон Моисей (ок. 1651–1713) 803. Рут Шерберн (1660–) 902. Джеймс Сойер (–1703) 903. Сара Брей (–стр. 1726) 992. Клемент Мессерви (–a1720) 993. Элизабет —-— (–a1720) 👫 11-е поколение 1592. Джеймс Херд (ок. 1632–ок. 1675) 1593. Шуа Конли (ок. 1640–) 1596. Джон Робертс (ок. 1629–1694/95) 1597. Эбигейл Наттер (–стр. 1674) 1602. Ренальд Фернальд (–c1656) 1603. Джоанна —-— (–c1660) 1604. Джон Мозес (ок. 1616–стр. 1693) 1605. Алиса —-— (–a1665) 1606. Генри Шерберн (1611–a1680) 1607. Ребекка Гиббонс (ок. 1617–1667) 1806. Томас Брей 👫 12-е поколение 3186. (вероятно) Авраам Конли 3192. Томас Робертс (–ок. 1674) 3193. Ребекка —-— (–a1673) 3194. Хатевил Наттер (ок. 1600–ок. 1675) 3195. Энн —-— (–стр. 1674) 3212. Джозеф Шерберн (–ок. 1621) 3214. Эмброуз Гиббонс (ок. 1592–ок. 1657) 3215. Элизабет —-— (–1655) 👫 13-е поколение 6388. Эдмунд Наттер (–a1633/34) 6389. Элизабет —-— (–1638) 6424. Генри Шерберн (–ок. 1598) Знаменитые родственники Стивена Кинга: 👤 Уильям Пиллсбери (1606 - 1686) Великое пересе��ение иммигрантов 1640 7-й прадедушка 👤 Джон Лэнгдон Подписавший Конституцию США Троюродный брат, 6 раз удаленный через Генри Шерберна 👤 Джон Гринлиф Уиттиер Американский поэт «у камина» 4-й кузен, 5 раз удаленный через Джона Робертса 👤 Джон Сарджент Пиллсбери Соучредитель CA Pillsbury Co. Пятиродный брат, 3 раза удаленный через Уильяма Пиллсбери 👤 Генри Уэллс Соучредитель American Express и Wells Fargo and Co. Пятиродный брат, 5 раз удаленный через Томаса Робертса 👤 Чарльз А. Пиллсбери Соучредитель CA Pillsbury Co. 6-й кузен, 2 раза удаленный через Уильяма Пиллсбери 👤 Роберт Фрост Поэт и драматург Семиродный брат, дважды удаленный через доктора Ренальда Фернальда 👤 Милтон Брэдли Основатель компании Milton Bradley Семиродный брат, 3 раза удаленный через Томаса Робертса 👤 Чаннинг Кокс 49-й губернатор Массачусетса Семиродный кузен 3 раза удален через Хатевила Наттера 👤 Брук Адамс Актриса кино и телевидения 8-й кузен 1 раз удален через Джона Херда 👤 Чарли Дэй Актёр кино и телевидения 8-й кузен 1 раз удален через Джона Херда 👤 Сэр Уинстон Черчилль Премьер-министр Соединенного Королевства 8-й кузен, 2 раза удаленный через Томаса Робертса 👤 Меган Маркл Герцогиня Сассекская, актриса телевидения 8-й кузен, 2 раза удаленный через Уильяма Пиллсбери 👤 Луи Л'Амур Западный автор 9-й кузен через Генри Шерберна 👤 Джон Риттер Актёр кино и телевидения 9-й кузен 1 раз удален через Генри Шерберна 👤 Адриенна Марден Киноактриса 9-й кузен 1 раз удален через Томаса Робертса 👤 Джордж Герберт 8-й граф Карнарвон , владелец замка Хайклер (он же Аббатство Даунтон) 9-й кузен, 2 раза удаленный через Джона Робертса 👤 Натаниэль Филбрик Автор книги «В сердце моря» 10-й кузен 1 раз удален через Томаса Робертса 👤 Хилари Суонк Киноактриса 10-й кузен 1 раз удален через Томаса Робертса 👤 Келси Грэммер Актёр кино и телевидения 10-й кузен 1 раз удален через Томаса Робертса ПРОШЛОЕ - РЯДОМ! 🌳📚🔎 🌳📚🔎 🌳📚🔎 🌳📚🔎 🌳📚🔎 🌳📚🔎 🌳📚🔎 🌳📚🔎 ✅Услуги составления родословной, генеалогического древа. 📖 ЗАКАЗ РОДОСЛОВНОЙ на нашем сайте: www.genealogyrus.ru/zakazat-issledovanie-rodoslovnoj 📖 ЗАКАЗ РОДОСЛОВНОЙ в нашей группе ВК: https://vk.com/app5619682_-66437473 ✉Или напишите нам: [email protected]

https://genealogyrus.ru/blog/tpost/3d0m1suls1-rodoslovnaya-stivena-kinga

0 notes

Text

Mrs Anna Maeve Sullivan Waters (1833-1853) - Find a Grave https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/184441087/anna-maeve-waters

0 notes

Text

While, as I said in the first post, most of the plural wives had significantly fewer children, I think it's interesting to compare Emmeline Free to Lucy and Emily, as she was the only one who actually had more children. Her pregnancies also overlap sometimes with Lucy's and Emily's, though not as much.

Emmeline married Brigham in April 1845, two days after her nineteenth birthday. He was forty-three. They had ten children:

Ella (born August 1847)

Marinda (July 1849)

Hyrum (January 1851)

Emmeline (February 1853)

Louisa (October 1855)

Lorenzo (September 1856)

Alonzo (December 1858)

Ruth (March 1861)

Daniel (February 1863)

Adella (October 1864)

Emmeline had three pregnancies that overlapped with both Lucy and Emily (Fanny + Emily + Marinda, Hyrum + Caroline + Ernest, Arta + Don Carlos + Louisa), though interestingly in two of those cases Lucy and Emily's children were within a couple months of each other and Emmeline's child was either a fair bit older or a fair bit younger (as much as you can get within a nine-month period). She also had three different pregnancies that overlapped with one of Lucy's but not one of Emily's (Emmeline + Shamira, Feramorz + Alonzo, Clarissa + Ruth).

In general, Emmeline's pregnancy spacing is probably the most even and consistent of any of the three women. The smallest gap between any of her children is eleven months (yikes), and the largest is 2 years + 8 months, but almost all her children are slightly less than 2 years apart. (These are the gaps before and after her daughter Louisa, who most records say was born in October 1855 but I've seen a couple that say October 1854, which would bring the spacing to a more even 18 months-2 years for every pregnancy, so that might be more statistically likely, though I don't want to discount that Louisa may have been an outlier.)

She also, interestingly, had her last child at 38, just like Emily and Lucy.

extremely nerdy statistics-based Mormonposting incoming:

So, I was examining some data about Brigham Young's wives and children, as you do, and I came to a very interesting realization about two of his wives, Lucy Decker and Emily Partridge, having quite strikingly parallel childbearing history. I'm going to just list their kids in bulletpoint and then analyze the two sets of data together because I think that will make the most visual sense.

Both women had seven children with Brigham Young. (Lucy also had two children with her first husband, but I'm only discussing kids fathered by Young in this analysis).

Lucy married Brigham Young as his first plural wife in June 1842, when she was twenty years old and he was forty-one. Their children were:

Heber (born in June 1845)

Fanny (January 1849)

Ernest (April 1851)

Shamira (March 1853)

Arta (April 1855)

Feramorz (September 1858)

Clarissa (July 1860)

Emily married BY in September 1844. She was either his fifth, sixth, or seventh plural wife (he married three different women in that month and we don't know the exact date of Emily's marriage). She was also twenty and he was forty-three. Their children were:

Edward (born October 1845)

Emily (March 1849)

Caroline (February 1851)

Don Carlos (May 1855)

Miriam (October 1857)

Josephine (February 1860)

Lura (April 1862)

As you can see, five pairs of these two women's children were born very close to each other (Heber + Edward four months apart, Fanny + Emily about six weeks apart, Caroline + Ernest also about six weeks apart, Arta + Don Carlos three weeks apart, and Josephine + Clarissa five months apart). Three of these pairs are extremely close in age, and in all five cases Lucy and Emily's pregnancies would have overlapped. I thought this was very interesting and also seems pretty statistically unlikely, but they seem to have been on what I will call a synced-up childbirth schedule for lack of a better term.

In general, both women are having children approximately every two years, give or take a few months, but there are a couple notable exceptions, including the one instance in which their childbirth schedules get really off track.

Lucy's Heber and Emily's Edward were the first two Young children born to plural wives, and the only ones born before the majority of the church left Nauvoo in early spring 1846. For the next two and a half years, Emily, Lucy, and their husband were mostly either on the road or living out of tents, wagons, and makeshift shacks. For most of 1847, Brigham was actually absent because he was part of the "vanguard pioneer company" that first reached the Salt Lake Valley and most of his wives were still back in Nebraska. I'm guessing this is why there is a larger than average gap (about three and a half years) between both boys and their younger sisters. Once they reach Utah, another sibling joins each woman's family in short order.

This is where the timelines diverge the most significantly. Lucy continues to give birth about every two years until her late thirties. Emily's third and fourth children, on the other hand, are more than four years apart. In November 1852, Emily's three children became seriously ill and seven-year-old Eddie sadly died. Afterwards, Emily, who seems to have felt that she was parenting and then grieving alone without any emotional support from her husband, wrote to Brigham asking for a divorce. It's unclear how he responded, but they stayed married. I'm guessing it took time to reconcile, and this is why Emily's childbirth pattern "skips" a period where Lucy continued to have pretty evenly spaced children, before getting back on the same general track when they both have sons less than a month apart in 1855.

Emily has her remaining children about one every 2.5 years and, like Lucy, has her last child at age 38. Having tracked this, I think it's very interesting, because you can see both how their childbearing trajectory conformed both to their own general pattern and to the patterns of the other, and also some pretty glaring anomalies that are probably connected to different dynamics in Emily and Lucy's respective marriages. Also, in terms of the social dynamics of polygamous marriage--it must have be weird to get pregnant and this other woman is immediately like "oh me too" and this happens five times. (Many of the other plural wives had a lot fewer children than either Emily or Lucy, and more seemingly "random" child spacing, so you don't really get any other instances where the same two women are repeatedly giving birth around the same time to this extent).

#me looking at this like. oh my god get a job stay away from her#i didnt want to put that in the body of the post but. jesus christ man. she did not have a moment's peace#Mormonposting tag

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mother's Day Lookbook (Part 1)

One of the requests on my followers survey was more lookbooks for different characters/age groups from the American Girl stories. Most of these women are the biological mother of a main character. Dolores is Josefina's aunt who eventually becomes her step-mother, while Océane is Marie-Grace's opera coach and eventual aunt.

Eetsa (1764), Martha Merriman (1774)

Mama Abbott (1812 - no first name), Dolores Romero (1824)

Aurélia Rey (1853), Océane Rousseau (1853)

Greta Larson (1854), Ruth Walker (1864)

CC thanks to @blogsimplesimmer, @buzzardly28, @coloresurbanos, @javitrulovesims, @linzlu, @mlyssimblr, @pandorasimbox, @peebsplays, @plumbobteasociety, @sheabuttyr, & Sifix (TSR)

WCIF always welcome! Part 2 of the lookbook here.

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Duchesses in Black: did Elisabeth really met her future husband wearing a black dress?

Duchess Ludovika had other matters on her mind when she and her daughters arrived in Bad Ischl on August 16, 1853. A migraine had forced her to interrupt the journey, so that her party arrived in Bad Ischl with some delay, upsetting all of Sophie’s carefully laid plans for the first day. Furthermore, while her daughters were with her on her arrival, Ludovika was accompanied by neither baggage nor ladies-in-waiting. All three women wore mourning for the death of an aunt.

Hamann, Brigitte (1986). The Reluctant Empress (translation by Ruth Hein)

The meeting at Ischl of the future Empress Elisabeth "Sisi" of Austria, then only a Duchess in Bavaria, with her cousin Franz Josef I of Austria, it's probably the most known moment of her life, thanks to the plenty of portrayals that it had in media. In August 16 of 1853 the Duchess Ludovika in Bavaria arrived in Ischl with her two eldest daughters, Helene "Néné" and Elisabeth "Sisi", to celebrate the birthday of the Emperor of Austria, who was also the son of Ludovika's elder sister the Archduchess Sophie. And in this birthday party, Franz Josef fell in love with Sisi. And with that, the teenaged girl was pulled out of obscurity into the spotlight.

There is one crucial detail that the portrayals of Elisabeth and Franz Josef's meeting omit: that Ludovika and her daughters arrived to the celebration wearing black because they were mourning an aunt. The only exception to this is the new series Sisi (2021-) that does shows Elisabeth meeting her future husband in a very modern looking black dress, although here she just does it because she's being Dramatic™ and not because her family is in mourning.

Last night I remembered this incident, the Duchesses arriving in black to the Emperor's birthday, when suddenly I realized something: who was the aunt that died? Ludovika had six sisters who survived infancy. Out of all of them, the first one to die was Auguste, Duchess of Leuchtenberg, who passed away in 1851. So she wasn't the aunt that Hamann refers to. The rest of Ludovika's sisters died in the 1870s. And neither could be one of Ludovika's sisters-in-law, for they died in 1838, 1854 and 1866 respectively. And Duke Max, Sisi and Nené's father, was an only child. Meaning: no aunt of Elisabeth and Helene died in 1853. So for who was the mourning?

I kept searching but still I couldn't find an aunt, uncle or cousin of any degree that died in 1853. The quote from Hamann's biography that opens this post doesn't cite a source, and given that apparently no relative, not even a distant one, of them died in that year, I started doubting if the story of them wearing black was even true to begin with. So I went back to The Reluctant Empress, and some pages after the quote from above I came across this:

Care went to providing the designated bride at least with an exquisite coiffure, even though she would have to appear before the Emperor in her dusty black traveling dress. Sisi looked after her own hair—simple long braids. She never noticed that Archduchess Sophie had a watchful eye, not only for Helene, but for Elisabeth as well. At any rate, Sophie later described this hairdressing scene at great length to her sister Marie of Saxony, stressing the “charm and grace” of the younger girl’s movements, “all the more so as she was so completely unaware of having produced such a pleasing effect. In spite of the mourning . . . Sissy [sic] was adorable in her very plain, high-necked black dress.” [13] Next to her completely artless, childlike sister, Helene seemed all at once very austere. The black dress was not flattering to her—and perhaps really did determine the course of her life, as some people later claimed.

We have a source here! A direct quote from Sophie! Hamann tells us that: "Sophie's detailed letter was published in the Reichspost, April 22, 1934. The quotations that follow are from the same source". Interestingly, there's no mention of the black dresses in Corti's Elisabeth, published in 1936, although maybe he just didn't knew about the letter. Earlier biographies don't mention it either (more understandable in those cases, given that the letter hadn't been published yet).

But I still couldn't answer the question that prompted this improvised investigation: who was the mourning for if no relative of them had died that year?

The Lonely Empress by Joan Haslip it's the major English biography on Empress Elisabeth. Sadly I don't own a copy, and the Archive.org doesn't have it either, so I haven't read it yet. But you can read some fragments of it on Google Books, and luckily for me, I was able to find a mention of the mourning dresses:

Meanwhile the Archduchess was awaiting her sister and nieces in the hotel where she had taken rooms for them. Not only were they over an hour late in arriving, but to her annoyance they all appeared dressed in black, in mourning for one of the Queen of Bavaria's aunts. Sophia was particularly irritated because her son was due at the villa in half an hour; there was no time for them to change, and with her pale face and dark hair Nene looked her very worst in black.

Haslip, Joan (1965). The Lonely Empress.

The quote goes on but Google didn't let me read more. But even so, I had a new clue!! My first thought was that Hamann misquoted Haslip and that's how we ended with the aunt thing, or maybe not even that, because I guess you can make the case that "an aunt" could mean someone elses's aunt and not the girls'. But Haslip isn't in the bibliography of The Reluctant Empress, so where did she got it from remains a mystery.

In 1853 the Queen of Bavaria was Marie of Prussia, the wife of King Maximilian II of Bavaria, who was Ludovika's nephew and therefore Elisabeth and Helene's cousin. So now I was once again going down the rabbit hole, checking every relative of Queen Marie and, once again, none that I could find had died in 1853. I was about about to fall in despair (?) when I realized that there was other Queen of Bavaria at that time: Therese of Saxe-Hildburghausen, the wife of King Ludwig I who amidst scandal abdicated the Bavarian throne in favor of his son Maximilian in 1848. I was reading a list of Therese's siblings when FINALLY:

Georg, Duke of Saxe-Altenburg (Hildburghausen, 24 July 1796 - Hummelshain, 3 August 1853)

I DID IT!! I found the relative!!! It was not Queen Therese's aunt who died, but her brother, and therefore King Maximilian's uncle. How did that turn into "the Queen of Bavaria's aunt" and then just "an aunt" I still don't know, but it was likely a case of misquotation that kept being repeated because no one double checked how many aunts of Elisabeth died in 1853 (zero).

To answer the question of the title, did Elisabeth really wear black when she met her future husband? The answer is yes. Was she in mourning for the passing of an aunt? The answer is no: they were mourning the death of an uncle of the King of Bavaria, which honestly explains why everyone was annoyed and not sad about this.

#tl;dr: yes but the dying aunt part it's fake news. read the whole thing to find out who actually died!#also I noticed that Helene looking bad in black isn't in quotation in neither Haslip's nor Hamann's book#which makes me wonder if it's something that Sophie actually wrote in the letter or if it's the authors taking artistic liberties#historian: brigitte hamann#historian: joan haslip#the lonely empress#the reluctant empress#empress elisabeth of austria#ludovika of bavaria duchess in bavaria#helene in bavaria hereditary princess of thurn und taxis#franz josef i of austria#historicwomendaily

92 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On April 28th 1789 The mutiny on the Bounty took place in the South Seas.

One of the mutineers was a Scotsman named William McCoy, although not one of the main mutineers led by Fletcher Christian he certainly had reason to be involved in the mutiny against the brutality of Captain Bligh as on one occasion he pointed a pistol at the head of McCoy and threatened to shoot him for not paying attention.

Here is a description of McCoy from Bligh himself…

[WILLIAM MICKOY] seaman, aged 25 years, 5 feet 6 inches high, fair complexion, light brown hair, strong made; a scar where he has been stabbed in the belly, and a small scar under his chin; is tatowed in different parts of his body.

Following the mutiny Fletcher Christian headed for Tahiti where they stayed for a few days before being compelled to set sail. McCoy, Christian and seven other mutineers took eleven Tahitian women and six men with them. After months at sea, the mutineers discovered the uninhabited island, Pitcairn and settled there in 1790.

McCoy had one consort, Teio, and fathered two children, Daniel and Catherine. After three years, a conflict broke out between the Tahitian men and the mutineers, resulting in the deaths of all the Tahitian men and five of the Englishmen. McCoy was one of the survivors.

And of course it was the Scot, McCoy who is said to be the the one who discovered how to distill alcohol from one of the island fruits on Pitcairn. Before becoming a sailor he was said to have worked in a Glasgow brewery.

He is said to have became an alcoholic along with a Matthew Quintal and finally ended his life by either falling or jumping off a cliff in a drunken frenzy, however, a Tahitian woman on Pitcairn claimed that when McCoy’s body washed ashore, he was discovered with his hands and feet bound with rope, suggesting that his “suicide” was really the work of other mutineers.

Most of the mutineers fathered several children, McCoy included, their descendants and their Tahitan consorts include the modern day Pitcairn Islanders as well as most of the population of Norfolk Island. Their descendants also live in New Zealand, Australia, and the United States. Because of the scarcity of people on the island, many of the mutineers’ children and grandchildren intermarried, with some marrying cousins and second cousins. Occasionally a new person would arrive on the island bringing with them a new surname.

Here are some of the decedents through the years….

Daniel McCoy son of William McCoy by Sarah Quintal daughter of Matthew Quintal

William McCoy (1812 – 17 February 1849) unmarried

Daniel McCoy (1814 – 27 June 1831) married Peggy Christian granddaughter of Fletcher Christian

Hugh McCoy (1816 – 27 June 1831) unmarried

Matthew McCoy (1819 – 31 January 1853) married Margaret Christian granddaughter ofFletcher Christiann

Jane McCoy (1822 – 4 June 1831) unmarried

Sarah McCoy (23 July 1824 – 9 May 1833) unmarried

Samuel McCoy (23 October 1826 – 7 September 1876) married 1) Ruth Quintal granddaughter of Matthew Quintal 2) Polly Christian great-granddaughter of Fletcher Christian

Albina McCoy (28 November 1828 – 12 June 1908) married Moses Young grandson of Ned Young

Daniel McCoy (28 December 1832 – 7 April 1855) married Lydia Young granddaughter of Ned Young.

The telephone books of the islands are littered with these names and many can trace their ancestry back to the mutineers.

If you want to know more history on the subject you can read a lot more here

https://library.puc.edu/pitcairn/bounty/crew3.shtml

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

just a list of books i read for the many phd applications i wrote! i just want to keep a record of it somewhere bc i had different frames & ideas for it, so this is so i wont forget what i read when it was going thru different iterations. those i asterisked werent read all the way through:

non fiction

*the passion projects, melanie micir (2019)

the fury archives, jill richards (2020)

wayward lives,beautiful experiments, saidiya hartman (2019)

the five, hallie rubenhold (2019)

*the new woman, sally ledger (1997)

*concieved in modernism, aimee armande wilson (2015) (i read some of the phd version of this because i couldnt access the book)

rebel crossings, sheila rowbotham (2016)

*the outside thing, hannah roche (2019)

wisps of violence, eileen sypher (1993)

dreamers of a new day, sheila rowbotham (2010)

i also read some of the phd thesis of sarah emily blewitt, hidden mothers and poetic pregnancy in women’s writing (1818-present day) (2015)

& a little of helen charman's phd thesis, george eliot's generative economies: transactional maternal sacrifice in social realist fiction, 1853-1894 (2019) (definitely going to go back to this when i've read all of eliot's work that's mentioned in it!)

as well as the article "in the centre of a circle”: olive moore’s spleen and gestational immigration by erin m. kingsley (2018)

& the article ' what does a socialist woman do?' birth control and the body politic in naomi mitchison’s we have been warned by mara dougall (2021)

fiction

attainment, edith ellis (1909)

lolly willowes, sylvia townsend warner (1926)

mr fortunes maggot, sylvia townsend warner (1927)

the true heart, sylvia townsend warner (1929)

*summer will show, (1936)

the quarry wood, nan shepherd (1928)

the tree of heaven, may sinclair (1917)

passing, nella larsen (1929)

cane, jean toomer (1923)

quicksand, nella larsen (1928)

the return of the soldier, rebecca west (1918)

jacob's room, virginia woolf (1922)

madame bovary, gustave flaubert translated by eleanor marx (1857/1885-6)

all passion spent, vita sackville-west (1931)

reuben sachs, amy levy (1888)

ruth, elizabeth gaskell (1853)

middlemarch, george eliot (1871)

money, victoria benedictsson, translated by sarah death (1885/2011)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birthdays 11.26

Beer Birthdays

Georg Schneider (1817)

Simon E. Bernheimer (1849)

Five Favorite Birthdays

Johannes Bach; German organist and composer (1604)

Dave Hughes; Australian comedian (1970)

Eugene Ionesco; Romanian-French writer (1912)

Rich Little; comedian (1938)

Charles M. Schulz; cartoonist (1922)

Famous Birthdays

Bob Babbitt; bass player (1937)

Garcelle Beauvais; model, actor (1966)

Natasha Bedingfield; English singer-songwriter (1981)

Elizabeth Blackburn; Australian-American biologist (1948)

Margaret Boden; English computer scientist (1936)

Willis Carrier; air-conditioning inventor (1876)

Roz Chast,; cartoonist (1954)

William Cowper; English poet (1731)

Cyril Cusack; South African-born Irish actor (1910)

Frances Dee; actress and singer (1909)

DJ Khaled; rapper (1975)

Adolfo Pérez Esquivel; Argentinian painter (1931)

Lefty Gomez; New York Yankees P (1908)

Robert Goulet; American-Canadian singer (1933)

Davey Graham; English guitarist and songwriter (1945)

Sarah Moore Grimké; author (1792)

Blake Harnage; singer-songwriter and guitarist (1988)

John Harvard; college founder (1607)

Line Horntveth; Norwegian tuba player, composer (1974)

Raymond Louis Kennedy; singer-songwriter, saxophonist (1946)

Yumi Kobayashi; Japanese model, actress (1988)

Martin Lee; English singer-songwriter and guitarist (1949)

Bat Masterson; police officer and journalist (1853)

Anna Maurizio; Swiss biologist (1900)

Maurice McDonald; businessman, co-founder of McDonald's (1902)

John McVie; English-American bass player (1945)

Marian Mercer; actress and singer (1935)

Jim Mullen; Scottish guitarist (1945)

Marianne Muellerleile; actress (1948)

Michael Omartian; singer-songwriter, keyboard player (1945)

Ruth Patrick; botanist (1907)

Vicki Pettersson; author (1971)

Velupillai Prabhakaran; Sri Lankan rebel leader (1954)

Marilynne Robinson; writer (1943)

George Segal; artist, sculptor (1924)

Eric Sevareid; television journalist (1912)

Ilona "Cicciolona" Staller; Hungarian-Italian porn actor, politician (1951)

Jan Stenerud; Kansas City Chiefs K (1942)

Betta St. John; actress, singer and dancer (1929)

Julien Temple; English film director (1952)

Lysa Thatcher; adult film actress (1959)

Art Themen; English saxophonist and surgeon (1939)

Tina Turner; American-Swiss rock singer (1938)

Tony Verna; director and inventor of instant replay (1933)

Mary Edwards Walker; surgeon and activist (1832)

Ellen G. White; co-founder of 7th-day Adventist Church (1827)

Norbert Wiener; mathematician (1894)

Earl Wild; pianist and composer (1915)

Bill Wilson; AA founder (1895)

Karl Ziegler; German chemist (1898)

1 note

·

View note