#ronnie barron

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

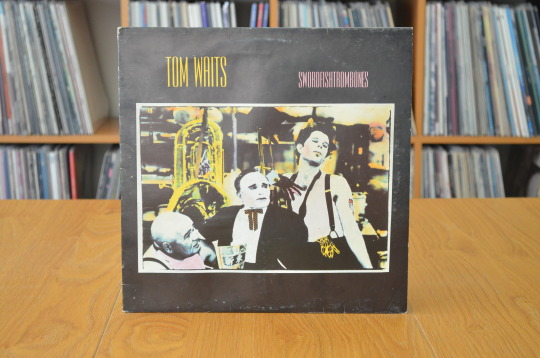

Tom Waits: Swordfishtrombones

Island ORL 19762, 19??

Originally released: September 1, 1983

#meine photos#vinylcollection#1983 music#tom waits#vinyloftheday#vinylcommunity#victor feldman#larry taylor#randy aldcroft#stephen taylor arvizu hodges#fred tackett#francis thumm#greg cohen#joe romano#anthony clark stewart#clark spangler#bill reichenbach jr#dick hyde#ronnie barron#eric bikales#carlos guitarlos#richard gibbs

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Gene Clark - Some Misunderstanding

#youtube#gene clark#some misunderstanding#no other#jerry mcgee#jesse ed davis#danny kortchmar#leland sklar#michael utley#russ kinkel#ronnie barron#folk rock#country rock#soul#r&b#music#music is love#music is life#music is religion#raining music#70s#70s music

0 notes

Text

Album 43

Album: GRIS-gris by Dr. John

Have I listened before? no

Familiarity with the artist: never heard of them

Background Knowledge:

the debut album by American musician Dr. John (a.k.a. Mac Rebennack), released Jan 22nd, 1968

the album introduced Rebennack's Dr. John character, inspired by a reputed 19th century voodoo doctor

the style of Gris-Gris is a hybrid of traditional New Orleans R&B elements and psychedelia

the album failed to chart in the United Kingdom and the United States. it was re-issued on compact disc decades later and received much greater praise from modern critics, including being listed at number 143 on the 2003 and 2012 editions and at number 356 on the 2020 edition of Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time

Interesting Info:

before recording the album, Rebennack was an experienced New Orleans R&B and rock musician playing as a session musician, songwriter, and producer in New Orleans. due to drug problems and the law, Rebennack moved to Los Angeles in 1965, joining a group of New Orleans session musicians

Rebennack desired to make an album that combined the various strains of New Orleans music behind a front man called Dr. John, after a black man named Dr. John Montaine, who claimed to be an African potentate. Rebennack chose this name after hearing about Montaine from his sister, and feeling a "spiritual kinship" with him. Rebennack originally wanted New Orleans singer Ronnie Barron to front the band as the Dr. John character, but Don Costa, who managed Barron at the time, advised him against it, claiming it to be a bad career move. Rebennack took on the Dr. John stage name himself

Gris-Gris was recorded at Gold Star Studios in Los Angeles, California. with an album due and no singer prepared, Dr. John managed to book studio time originally reserved for Sonny & Cher.

Listened on: Apple Music

Final Review: kinda sounds like Tom Jones does experimental bossa nova? idk i guess it was fine for what it is and there were some nice grooves but it was a bit repetitive and nothing really stood out to me

#background knowledge and interesting info taken from wikipedia. as always#1001 albums you must hear before you die#1001albumslist#dr. john

2 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Dr. John (Ronnie Barron) - Did She Mention My Name? (1964)

A friend played this wonderful NOLA soul tune for me recently, and I found it hard to believe it was Dr. John. That’s because it wasn’t Mac Rebennack singing, it was Ronnie Barron. Mac Rebennack had come up the the persona of Dr. John, the night tripper, and he wanted Ronnie Barron to play the role. Ronnie wasn’t having it, and the rest is history. Mac did write the song, and there’s a record which credits Ronnie Barron though it’s a bit faster.

51 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

08-Doing Business With The Devil /Ronnie Barron

0 notes

Audio

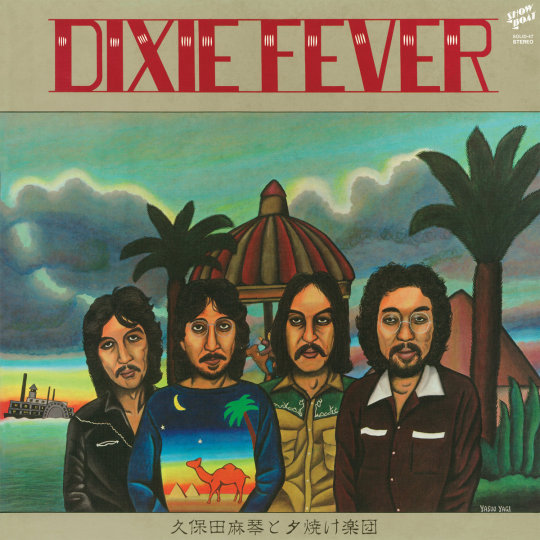

Makoto Kubota & The Sunset Gang - Dixie Fever (1976)

https://www.wewantsounds.com

#makoto kubota#the sunset gang#dixie fever#1976#1970s#haruomi hosono#japan#rock#pop#folk#Takashi Onzo#tatsuo hayashi#kenny inoue#yosuke fujita#ronnie barron#Dennis Graue#roger bailey#bob cabral#travis fullerton

0 notes

Text

youtube

The guy from Above The Law & Code Of Silence

0 notes

Text

RIP Malcolm 'Dr. John' Rebennack (20.11.1941 - 6.6.2019)

"See, I don't know nothing about singing. I never wanted to be a frontman. Frontmen had big egos and was always crazy and aggravating. I just never thought that was a good idea."

#Malcolm John Rebennack#Dr. John#Mac Rebennack#The night tripper#Music#Rip#Death ment#Gris gris#A true one off#The whole dr. John act was pure accident#Rebennack developed the original idea and the persona for his friend ronnie barron#With mac taking a behind the scenes production role. But barron dropped out and suddenly mac was dr. John#Serendipity i guess

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Llevo horas encerrado en esta sala para interrogatorios, la potente luz blanca de la bombilla sobre mi cabeza me causa migraña y mis manos esposadas a una fría mesa de metal, hace tiempo que se han entumecido.

Por si fuera poco, me gruñen las tripas, me siento sucio y no he vuelto a ver a mis hijos desde que esos hombres me separaron de ellos, Dios quiera y se encuentren bien.

Sé que debí sacarlos cuando pude, pero ¿Qué más podía hacer?, en aquel momento estábamos entre la espada y la pared, creí que hacia lo correcto al confiar en él, después todo era nuestro amigo, nuestro líder, nuestro pastor. Texto completo.

0 notes

Audio

Dr. John, The Night Tripper - I Walk On Guilded Splinters Dr. John Creaux (Mac Rebennack) from: “Gris-Gris” (LP)

Fusion | New Orleans R 'n' B | Psychedelia | Voodoo

JukehostUK (left click = play) (320kbps)

Album Personnel: Dr. John Creaux: Lead Vocals / Keyboards / Guitar / Percussion Harold Battiste: Bass / Clarinet / Percussion Richard 'Didimus' Washington: Guitar / Mandolin / Percussion Plas Johnson: Saxophone Lonnie Boulden: Flute Steve Mann: Guitar / Banjo Ernest McLean: Guitar / Mandolin Bob West: Bass Mo Pedido: Congas John Boudreaux: Drums

Backing Vocals: Jessie Hill Ronnie Barron Shirley Goodman Tami Lynn

Produced by Harold Battiste

Recorded: @ The Gold Star Studios in Los Angeles, California USA during 1967

Album Released: on January 22, 1968

#Mac Rebennack#Dr. John#Gris-Gris#I Walk On Guilded Splinters#Walk On Guilded Splinters#1960's#Voodoo#Dr. John Creaux#New Orleans R&B#Fusion#Psychedelia#Harold Battiste#Plas Johnson#Gold Star Studios#Dr. John The Night Tripper

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Fourth Rate

The fourth rate is a two decker line ship with 46-60 guns. If you look at it closely, they only really appear from the middle of the 17th century onwards, but they also existed from 1626 onwards. However, the ships there were not rated according to their guns but according to their crew size and it is therefore difficult to regard a fourth rate as such. But already at the beginning of the 18th century the admiralty noticed that the fourth rate could not keep up with the other ships of the line.

Model of a fourth rate, with 60 guns, made by unknown c. 1660 (x)

And so the 60-gun class almost disappeared completely by the end of the 18th century. The 50 gun class also had its difficulties, but remained on the Admiralty's books until the end of the 18th century with 16 examples. And six new ones were even taken into service.

Early in 1807, an incident occurred in Chesapeake Bay when several British sailors, some of American descent, abandoned their ships besieging French vessels and joined the crew of the USS Chesapeake. The commander of HMS Leopard, a fourth rate, Captain Salusbury Pryce Humphreys, then demanded permission from the American frigate under the command of Commodore James Barron to search that ship in order to arrest and punish the deserters. When Barron refused, Humphreys opened fire. Taking the Americans completely by surprise, Barron surrendered and a British boarding party began searching the frigate, apprehending four deserters - three of whom were Americans, the fourth, Jenkin Ratford, was British. The prisoners were taken to Halifax, where Ratford was tried and hanged. The Americans were originally sentenced to 500 lashes, but the execution was suspended and they were offered to be returned to the United States. The incident had some political consequences and almost resulted in a war between the United States and Britain. Painted by Ronny Moorgat (x)

The Antelope, Diomede and Grampus 1798-1802 and finally three more for the War of 1812, from 1813-15, the Salisbury, Romney and the Isis. The Navy also had East India ships rebuilt in 1795, but more out of necessity because of a lack of ships than because they liked them so much.

The Earl of Abergavenny was actually an East Indiamen which became a fourth rate with 56 guns between 1803-1804 and served as a privateer to the Admiralty. Before she was returned to the East India Company.Painted by Thomas Luny 1801 (x)

As they were now rather unsuitable as ships of the line, even if they carried two decks. They were used as patrol ships or flagships for frigate squadrons. But one or the other also cut a good figure as a privateer. And they could also be used in the rather low water conditions of the Baltic Sea. Their armament was usually around 22, 24pdr on the main gun deck and 24, 12pdr on the upper gun deck. Unfortunately, her sailing characteristics were rather poor and therefore she was a rather unpopular command.

All in all they were a rather poor warship and were therefore used from the 1810s onwards in the East Indies where they were quite successful. But even here their numbers declined steadily and by the 1820s they had disappeared completely.

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black Lives Matter: A Reading List

On this blog, we believe Black Lives Matter. I’ve been quiet here because I’ve just been absorbing and listening and loud on other platforms. But I wanted to take the time and share some books by Black authors that may not be on your radar, books besides The Hate U Give and Dear Martin and Children of Blood and Bone (though I hope you’re reading those too, you’ve probably heard of them at this point). It also won’t just be books about Black pain because Black people have a huge range of experiences and they all deserve to be heard.

All the links in this post will go to Mahogany Books, a Black owned bookstore in Washington, D.C. that does ship. If I can’t find it on their website, the link will go to Semicolon Bookstore, another Black owned indie bookstore, this one located in Chicago’s, Bookshop page. Please note that many books are currently backordered because there’s a huge rush on books by Black authors (especially anti-racist books) right now and there was already a paper shortage and delays in printing because of COVID-19. If that’s the case, check your local library’s digital resources or check other bookstores since they all have varying stock.

Non-Fiction

We Are Not Yet Equal by Carol Anderson and Tonya Bolden Say Her Name by Zetta Elliott This Book is Anti-Racist by Tiffany Jewell and Aurelia Durand All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson Stamped by Ibram X. Kendi and Jason Reynolds Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson

Contemporary and Historical

Clap When You Land by Elizabeth Acevedo The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo With the Fire on High by Elizabeth Acevedo Solo by Kwame Alexander and Mary Rand Hess The Wicker King by K. Ancrum Inventing Victoria by Tonya Bolden Saving Savannah by Tonya Bolden Felix Ever After by Kacen Callender This is Kind of an Epic Love Story by Kacen Callender Finding Yvonne by Brandy Colbert Little and Lion by Brandy Colbert Pointe by Brandy Colbert The Revolution of Birdie Randolph by Brandy Colbert The Voting Booth by Brandy Colbert Tyler Johnson Was Here by Jay Coles Tiffany Sly Lives Here Now by Dana L. Davis The Voice in My Head by Dana L. Davis When the Stars Lead to You by Ronni Davis I Wanna Be Where You Are by Kristina Forest Now That I’ve Found You by Kristina Forest Full Disclosure by Camryn Garrett Endangered by Lamar Giles Fake ID by Lamar Giles Not So Pure and Simple by Lamar Giles Overturned by Lamar Giles Spin by Lamar Giles A Love Hate Thing by Whitney D. Grandison Allegedly by Tiffany D. Jackson Grown by Tiffany D. Jackson Let Me Hear a Rhyme by Tiffany D. Jackson Monday’s Not Coming by Tiffany D. Jackson This is My America by Kim Johnson You Should See Me in a Crown by Leah Johnson I’m Not Dying with You Tonight by Kim Jones and Gilly Segal If It Makes You Happy by Claire Kann Let’s Talk About Love by Claire Kann 37 Things I Love (In No Particular Order) by Kekla Magoon How It Went Down by Kekla Magoon Light It Up by Kekla Magoon By Any Means Necessary by Candice Montgomery Home and Away by Candice Montgomery Slay by Brittney Morris Dear Haiti, Love Alaine by Maika Moulite and Maritza Moulite Who Put This Song On? by Morgan Parker The Field Guide to the North American Teenager by Ben Philippe Girls Like Us by Randi Pink Sorry Not Sorry by Jaime Reed All-American Boys by Jason Reynolds The Boy in the Black Suit by Jason Reynolds For Every One by Jason Reynolds Long Way Down by Jason Reynolds Look Both Ways by Jason Reynolds When I Was the Greatest by Jason Reynolds Opposite of Always by Justin A. Reynolds Truly Madly Royally by Debbie Rigaud The Blossom and the Firefly by Sherri L. Smith Flygirl by Sherri L. Smith Jackpot by Nic Stone Odd One Out by Nic Stone All the Things We Never Knew by Liara Tamani Calling My Name by Liara Tamani On the Come Up by Angie Thomas Piecing Me Together by Renee Watson This Side of Home by Renee Watson Watch Us Rise by Renee Watson and Ellen Hagan The Beauty That Remains by Ashley Woodfolk When You Were Everything by Ashley Woodfolk If You Come Softly by Jacqueline Woodson The Sun is Also a Star by Nicola Yoon American Street by Ibi Zoboi Black Enough edited by Ibi Zoboi Pride by Ibi Zoboii

Sci-Fi and Fantasy Daughters of Nri by Reni K. Amayo The Weight of the Stars by K. Ancrum Kingdom of Souls by Rena Barron Cinderella is Dead by Kalynn Bayron Black Girl Unlimited by Echo Brown A Song of Wraiths and Ruin by Roseanne A. Brown A Phoenix First Must Burn edited by Patrice Caldwell The Belles by Dhonielle Clayton Mirage by Somaiya Daud The Good Luck Girls by Charlotte Nicole Davis The Sound of Stars by Alechia Dow Pet by Akwaeke Emezi Raybearer by Jordan Ifueko Dread Nation by Justina Ireland Love is the Drug by Alaya Dawn Johnson The Summer Prince by Alaya Dawn Johnson A River of Royal Blood by Amanda Joy A Blade So Black by L.L. McKinney Agnes at the End of the World by Kelly McWilliams The Black Veins by Ashia Monet A Song Below Water by Bethany C. Morrow Akata Witch by Nendi Okorafor Shadowshaper by Danielle Jose Older Beasts Made of Night by Tochi Onyebuchi War Girls by Tochi Onyebuchi Dorothy Must Die by Danielle Paige Orleans by Sherri L. Smith Given by Nandi Taylor

This isn’t a complete list and I probably missed a bunch - especially since this list is very focused on mainstream publishing. I also added a few books that aren’t out yet, but are coming out this summer. But this is a starting place for whatever kind of YA book you want to read.

249 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The venture would have gone nowhere without the help of Harold Battiste. The arranger knew the heads of Atlantic Records through their subsidiary ATCO that released all of Sonny and Cher’s albums. Ahmet Ertegun and Jerry Wexler gave Battiste some level of freedom to come up with projects of his own. Battiste seized an opportunity of free studio time when Sonny and Cher were busy filming the musical thriller comedy Good Times, a waste of celluloid that better remains in the vaults. It was William Friedkin’s debut as a director, and he later commented: “I’ve made better films than Good Times but I’ve never had so much fun.” But as footballer Johan Cruyf said, every disadvantage has its advantage. During that free studio time Battiste got Mac and his crew into Gold Star Studios to record their brew of music voodoo. Mac wasn’t planning to sing on the record but his first choice, his childhood friend Ronnie Barron, was not available. Realizing that he can do a singing job no worse than Sonny Bono or Bob Dylan, he decided to debut on vocals on this album.

Hayim Kobi at The Music Aficionado. Gris-Gris, by Dr. John

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lee Konitz, jazz alto saxophonist who was a founding influence on the ‘cool school’ of the 1950s died aged 92

The music critic Gary Giddins once likened the alto saxophone playing of Lee Konitz, who has died aged 92 from complications of Covid-19, to the sound of someone “thinking out loud”. In the hothouse of an impulsive, spontaneous music, Konitz sounded like a jazz player from a different habitat entirely – a man immersed in contemplation more than impassioned tumult, a patient explorer of fine-tuned nuances.

Konitz played with a delicate intelligence and meticulous attention to detail, his phrasing impassively steady in its dynamics but bewitching in line. Yet he relished the risks of improvising. He loved long, curling melodies that kept their ultimate destinations hidden, he had a pure tone that eschewed dramatic embellishments, and he seemed to have all the time in the world. “Lee really likes playing with no music there at all,” the trumpeter Kenny Wheeler once told me. “He’ll say ‘You start this tune’ and you’ll say ‘What tune?’ and he’ll say ‘I don’t care, just start.’”

Born in Chicago, the youngest of three sons of immigrant parents – an Austrian father, who ran a laundry business, and a Russian mother, who encouraged his musical interests – Konitz became a founding influence on the 1950s “cool school”, which was, in part, an attempt to get out of the way of the almost unavoidable dominance of Charlie Parker on post-1940s jazz. For all his technical brilliance, Parker was a raw, earthy and impassioned player, and rarely far from the blues. As a child, Konitz studied the clarinet with a member of Chicago Symphony Orchestra and he had a classical player’s silvery purity of tone; he avoided both heart-on-sleeve vibrato and the staccato accents characterising bebop.

However, Konitz and Parker had a mutual admiration for the saxophone sound of Lester Young – much accelerated but still audible in Parker’s phrasing, tonally recognisable in Konitz’s poignant, stately and rather melancholy sound. Konitz switched from clarinet to saxophone in 1942, initially adopting the tenor instrument. He began playing professionally, and encountered Lennie Tristano, the blind, autocratic, musically visionary Chicago pianist who was probably the biggest single influence on the cool movement. Tristano valued an almost mathematically pristine melodic inventiveness over emotional colouration in music, and was obsessive in its pursuit. “He felt and communicated that music was a serious matter,” Konitz said. “It wasn’t a game, or a means of making a living, it was a life force.”

Tristano came close to anticipating free improvisation more than a decade before the notion took wider hold, and his impatience with the dictatorship of popular songs and their inexorable chord patterns – then the underpinnings of virtually all jazz – affected all his disciples. Konitz declared much later that a self-contained, standalone improvised solo with its own inner logic, rather than a string of variations on chords, was always his objective. His pursuit of this dream put pressures on his career that many musicians with less exacting standards were able to avoid.

Konitz switched from tenor to alto saxophone in the 1940s. He worked with the clarinettist Jerry Wald, and by 20 he was in Claude Thornhill’s dance band. This subtle outfit was widely admired for its slow-moving, atmospheric “clouds of sound” arrangements, and its use of what jazz hardliners sometimes dismissed as “front-parlour instruments” – bassoons, French horns, bass clarinets and flutes.

Regular Thornhill arrangers included the saxophonist Gerry Mulligan and the classically influenced pianist Gil Evans. Miles Davis was also drawn into an experimental composing circle that regularly met in Evans’s New York apartment. The result was a series of Thornhill-like pieces arranged for a nine-piece band showcasing Davis’s fragile-sounding trumpet. The 1949 and 1950 sessions became immortalised as the Birth of the Cool recordings, though they then made little impact. Davis was the figurehead, but the playing was ensemble-based and Konitz’s plaintive, breathy alto saxophone already stood out, particularly on such drifting tone-poems as Moon Dreams.

Konitz maintained the relationship with Tristano until 1951, before going his own way with the trombonist Tyree Glenn, and then with the popular, advanced-swing Stan Kenton orchestra. Konitz’s delicacy inevitably toughened in the tumult of the Kenton sound, and the orchestra’s power jolted him out of Tristano’s favourite long, pale, minimally inflected lines into more fragmented, bop-like figures. But the saxophonist really preferred small-group improvisation. He began to lead his own bands, frequently with the pianist Ronnie Ball and the bassist Peter Ind, and sometimes with the guitarist Billy Bauer and the brilliant West Coast tenor saxophonist Warne Marsh.

In 1961 Konitz recorded the album Motion with John Coltrane’s drummer Elvin Jones and the bassist Sonny Dallas. Jones’s intensity and Konitz’s whimsical delicacy unexpectedly turned out to be a perfect match. Konitz also struck up the first of what were to be many significant European connections, touring the continent with the Austrian saxophonist Hans Koller and the Swedish saxophone player Lars Gullin. He drifted between playing and teaching when his studious avoidance of the musically obvious reduced his bookings, but he resumed working with Tristano and Marsh for some live dates in 1964, and played with the equally dedicated and serious Jim Hall, the thinking fan’s guitarist.

Konitz loved the duo format’s opportunities for intimate improvised conversation. Indifferent to commercial niceties, he delivered five versions of Alone Together on the 1967 album The Lee Konitz Duets, first exploring it unaccompanied and then with a variety of other halves including the vibraphonist Karl Berger. The saxophonist Joe Henderson and the trombonist Marshall Brown also found much common ground with Konitz in this setting. Konitz developed the idea on 1970s recordings with the pianist-bassist Red Mitchell and the pianist Hal Galper – fascinating exercises in linear melodic suppleness with the gently unobtrusive Galper; more harmonically taxing and wider-ranging sax adventures against Mitchell’s unbending chord frameworks.

Despite his interest in new departures, Konitz never entirely embraced the experimental avant garde, or rejected the lyrical possibilities of conventional tonality. But he became interested in the music of the pianist Paul Bley and his wife, the composer Carla Bley, and in 1987 participated in surprising experiments in totally free and non jazz-based improvisation with the British guitarist Derek Bailey and others.

Konitz also taught extensively – face to face, and via posted tapes to students around the world. Teaching was his refuge, and he often apparently preferred it to performance. In 1974 Konitz, working with Mitchell and the alto saxophonist Jackie McLean in Denmark, recorded a brilliant standards album, Jazz à Juan, with the pianist Martial Solal, the bassist Niels-Henning Orsted Pedersen and the drummer Daniel Humair. That year, too, Konitz released the captivating, unaccompanied Lone-Lee with its spare and logical improvising, and a fitfully free-funky exploration with Davis’s bass-drums team of Dave Holland and Jack DeJohnette.

In the 1980s, Konitz worked extensively with Solal and the pianist Michel Petrucciani, and made a fascinating album with a Swedish octet led by the pianist Lars Sjösten – in memory of the compositions of Gullin, some of which had originally been dedicated to Konitz from their collaborations in the 1950s. With the pianist Harold Danko, Konitz produced music of remarkable freshness, including the open, unpremeditated Wild As Springtime recorded in Glasgow in 1984. Sometimes performing as a duo, sometimes within quartets and quintets, the Konitz/Danko pairing was to become one of the most productive of Konitz’s musical relationships.

Still tirelessly revealing how much spontaneous material could be spun from the same tunes – Alone Together and George Russell’s Ezz-thetic were among his favourites – by the end of the 1980s Konitz was also broadening his options through the use of the soprano saxophone. His importance to European fans was confirmed in 1992 when he received the Danish Jazzpar prize. He spent the 1990s moving between conventional jazz, open-improvisation and cross-genre explorations, sometimes with chamber groups, string ensembles and full classical orchestras.

On a fine session in 1992 with players including the pianist Kenny Barron, Konitz confirmed how gracefully shapely yet completely free from romantic excess he could be on standards material. He worked with such comparably improv-devoted perfectionists as Paul Motian, Steve Swallow, John Abercrombie, Marc Johnson and Joey Baron late in that decade. In 2000 he showed how open to wider persuasions he remained when he joined the Axis String Quartet on a repertoire devoted to 20th-century French composers including Erik Satie, Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel.

In 2002 Konitz headlined the London jazz festival, opening the show by inviting the audience to collectively hum a single note while he blew five absorbing minutes of typically airy, variously reluctant and impetuous alto sax variations over it. The early 21st century also heralded a prolific sequence of recordings – including Live at Birdland with the pianist Brad Mehldau and some structurally intricate genre-bending with the saxophonist Ohad Talmor’s unorthodox lineups.

Pianist Richie Beirach’s duet with Konitz - untypically playing the soprano instrument - on the impromptu Universal Lament was a casually exquisite highlight of Knowing Lee (2011), an album that also compellingly contrasted Konitz’s gauzy sax sound with Dave Liebman’s grittier one.

Konitz was co-founder of the leaderless quartet Enfants Terribles (with Baron, the guitarist Bill Frisell and the bassist Gary Peacock) and recorded the standards-morphing album Live at the Blue Note (2012), which included a mischievous fusion of Cole Porter’s What Is This Thing Called Love? and Subconscious-Lee, the famous Konitz original he had composed for the same chord sequence. First Meeting: Live in London Vol 1 (2013) captured Konitz’s improv set in 2010 with the pianist Dan Tepfer, bassist Michael Janisch and drummer Jeff Williams, and at 2015’s Cheltenham Jazz Festival, the old master both played and softly sang in company with an empathic younger pioneer, the trumpeter Dave Douglas. Late that year, the 88-year-old scattered some characteristically pungent sax propositions and a few quirky scat vocals into the path of Barron’s trio on Frescalalto (2017).

Cologne’s accomplished WDR Big Band also invited Konitz (a resident in the German city for some years) to record new arrangements of his and Tristano’s music, and in 2018 his performance with the Brandenburg State Orchestra of Prisma, Gunter Buhles’s concerto for alto saxophone and full orchestra, was released. In senior years as in youth, Konitz kept on confirming Wheeler’s view that he was never happier than when he didn’t know what was coming next.

Konitz was married twice; he is survived by two sons, Josh and Paul, and three daughters, Rebecca, Stephanie and Karen, three grandchildren and a great-grandchild.

• Lee Konitz, musician, born 13 October 1927; died 15 April 2020

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Valiant Central Podcast Ep 116: Valiant Shenanigans and Exclusives - All-Comic.com

On the latest episode of the Valiant Central Podcast, Paul and Martin are joined by Ronnie Barron from Rebirthically, Aftershock Central and other podcasts as well as mega collector Justin Ehart of the Collecting Valiant podcast to talk about the latest happenings in the Valiant comics universe!...

View Post: http://all-comic.com/2017/valiant-central-podcast-ep-116-valiant-shenanigans-exclusives/

#All-Comic.com#C2E2#collecting#Comics#justin ehart#Martin Ferretti#Paul Tesseneer#ronnie barron#sccc#Valiant#Valiant Central#Valiant Central Podcast#Valiant Comics#Valiant Database#X-O Manowar#X-O Manowar 1

0 notes

Text

Sneak Peak: 6 Mädels, 11 Tage, 1 Campervan, 1 Auto & Tasmanien

Da ich diese Woche leider sehr im Stress bin was Uni angeht (es hat heute die letzte Woche meines Auslandssemesters begonnen), dachte ich gebe ich euch einen kleinen ersten Eindruck in meine Semesterferien. Semesterferien sind hier nach der 10. Vorlesungswoche und gehe nur eine Woche. Da man aber meistens nur 1-2 Tage Uni hat, sind wir Freitags um 4 Uhr morgens zum Flughafen gestartet und 11 Tage später am Montag spät nachts wieder in Brisbane gelandet. Gemietet hatten wir einen Campervan indem 4 Leute schlafen konnten und ein Auto für das wir alle Utensilien gekauft haben, damit Myrthe und ich darin schlafen konnten. (Wir haben uns für ein Auto entschieden, weil es das für alle beteiligten günstiger gemacht hat als 2 Camper zu mieten... auch wenn Myrthe und ich am Ende das gleiche bezahlt haben wie die andere.)

Mit in Tasmanien waren Deborah (Deutschland), Katla (Island), Myrthe (Niederlande), Nolia (Frankreich), Suyi (China/Tschechien) und Ich. Ein bunter Mix, der wirklich sehr schön war aber auch ab und zum Haare raufen. Aber dazu in einem anderen Post mehr.

Allgemein hat mir Tasmanien unglaublich gut gefallen. Mit der Natur und der Größe hat es mich sehr an Neuseeland erinnert. Wer also mal ans andere Ende der Welt reisen möchte, aber nicht genug Zeit hat um Australien oder Neuseeland ausgiebig zu bereisen, dem lege ich Tasmanien wärmstens ans Herz!

Unter jedem Foto ein kleine Beschreibung und ausführlicher berichte ich sobald ich meine beiden Hausarbeiten abgegeben habe.

Ganz Liebe Grüße von mir aus der Bib.

Unsere erste Nacht in Kettering (Gordon Foreshore Reserve), direkt am Meer und auf der anderen Seite sieht man Bruny Island wo wir am nächsten Tag hin sind. Unsere Campingplätze haben wir alle mit der CamperMate App gefunden, wo es einem farblich anzeigt wie teuer der Campingplatz ist. Grün ist for free, blau ist günstig und lila ist teuer. Wir haben immer versucht kostenlose Campingplätze zu nutzen, außer wenn die Mädels duschen wollten (Myrthe und ich waren da etwas unproblematischer mit Katzenwäsche und Mütze)

Nach Bruny Island ging es in Richtung Port Arthur, leider gab es da nicht so viel zu sehen wie wir gehofft haben. Diese Steinwand wir liebevoll Devils Kitchen genannt und war neben “The Tasmanian Arch” und der “Blow Hole” (das ist wirklich der Name!) die Hauptsehenswürdigkeiten für uns dort. Oh und auch unsere einzigen Stopps :D

Mit das beste am Trip waren die Fahrten. Die Aussicht und ihre Abwechslung, einzigartig! Im Auto hatten wir auch ein Bluetooth Radio und konnten somit Spotify nutzen worüber die anderen Mädels richtig neidisch waren. Wir hatten also Car Karaoke und ab und an kam von Myrthe oder mir ein “Oooooh” oder “Wooow”, die andere hat dann gefragt “What is it? What happened?”, haha, weil zumindest ich meistens dachte irgendwas sei passiert, aber es war nur die Aussicht. Im Vergleich zum Campervan waren wir meistens 1-2 Stunden vor den anderen am Ziel und konnten dadurch einen Powernap machen oder die Feuerstelle aufbauen. Einmal kamen die Mädels über 2h nach uns an, wir hatten keinen Handyempfang, es war schon stock dunkel und wir haben uns gefragt wann wir anfangen sollen uns Sorgen zu machen. Als sie dann ankamen waren sie kurz davor wieder zu gehen weil die einzige Toilette auf dem kostenlosen Campingplatz geschlossen war, haha. Aber wir sind geblieben und haben Stockbrot gemacht.

Den Abend in Port Arthur haben wir auf dem Fortescue Bay Campground im Tasman National Park verbracht. Die Fahrt auf einer aufregende Schotter-/Schlammstraße dorthin hat uns etwa eine Stunde gekostet. (Das Navi der Mädels war der Meinung man schafft es in 20 Minuten, vielleicht war das der Grund, dass sie immer so spät da waren).

In Fortescue Bay war Feuerverbot, obwohl wir an dem Tag Feuerholz gekauft haben waren wir nicht traurig darüber. Als Ausgleich haben wir uns mit Wein und Cider und unseren Campingstühlen auf den Steg gesetzt und den Sonnenuntergang genossen. Dabei haben wir über alles mögliche geredet und Figuren in den Wolken gesucht, bis es irgendwann zu kalt wurde.

Jetzt fehlen ein paar Bilder um einen Einblick in die anderen Tage zu geben, aber die kommen dann in den folgenden Beiträgen. Dieses Bild ist auf unsere Wanderung im Cradle Mountain entstanden. Ein Must-Do wenn man in Tasmanien ist, zumindest haben das alle gesagt die schon da waren. Und ich kann das nur bestätigen. Wir sind vom Visitor Centre mit dem Shuttle zum Ronny Creek gefahren, um von dort einen Teil des “Overland Pass” zu den Crater Falls zu laufen.

Von den Crater Falls ging es weiter zum Crater Lake mit diesem idyllischen Bootshaus. Ein bisschen steiler den Berg hoch ging es dann zum Marions Lookout, von welchem man eine beeindruckende Aussicht hatte. Wir sind dann noch die 2,5 h Tour um den Dove Lake gelaufen. An diesem Tag haben wir nicht nur die beeindruckende Natur Tasmaniens gesehen, sondern auch ein paar Tiere (stay tuned um zu erfahren welche!)

Und eine weitere Blow Hole, dieses mal die Iron Blow Hole. In dieser Gegend wurde sehr viel Bergbau betrieben, was man deutlich sehen kann, selbst auf diesem Bild. Die Iron Blow Hole war ein sehr spontaner Stopp und dafür sehr - ich würde gerne beeindruckend sagen, hab das Wort aber in den letzten 2 Absätzen schon zu oft verwendet - eindrucksvoll. :D

Gegen Ende der Reise wurden die Mädels ein bisschen unmotivierter was Wanderungen angeht - oder waren sie überhaupt irgendwann motiviert?! Vielleicht lag es aber auch daran, dass wir am Abend nach Cradle Mountain ein bisschen höher gelegen (”in den Bergen”) auf dem Parkplatz eines Hotels übernachtet haben. Das war natürlich nicht der ausschlaggebende Faktor, sondern vielmehr, dass es in dieser Nacht -1°C hatte!!!! Myrthe und ich sind im Auto halb erfroren. Wir haben sogar überlegt in Löffelchen Position zu schlafen (ich war mir aber nicht sicher ob sie das als Scherz meinte). Die ganze Nacht haben wir versucht uns nicht zu bewegen um das kleine bisschen Wärme nicht zu verlieren. Schlafanzug + 2 dicke Pullover + Socken + Mütze + 2 Decken + nachts um 4 das Auto anmachen um die Heizung zu nutzen, es hat alles nichts geholfen. Ich hab von 4 Uhr morgens ab die “Daumen gedreht” und war froh als es endlich 6.30 Uhr war und ich aufstehen konnte. Vermutlich war das eher der Grund für die Unmotiviertheit. Bei Myrthe hat es eher das Gegenteil bewirkt. Sie war höchst motiviert eine große Wanderung an dem Tag zu machen. Als Suyi dann auch gemeint hat, dass sie gerne wandern möchte war ich ebenfalls überzeugt und wir sind am Lake St. Clair zur Spitze des Mount Rufus gewandert. Diese Wanderung benötigt aber definitiv einen extra Eintrag.

Unseren letzten ganzen Tag haben wir im Mount Field National Park verbracht. Eine gemütliche Wanderung zu den Russell Falls, den Horseshoe Falls (der Name macht total Sinn wenn man sie sieht! - man kann es ein wenig auf dem Foto erkennen) und den Lady Barron Falls. Auf dem Wanderweg, welcher Tall Tree Walk heißt, waren Infotafeln mit Fakten über die Baumriesen. Die swamp gums sind weltweit die größten blühenden Pflanzen - sehr interessant!

1 note

·

View note