#romanovs in exile

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

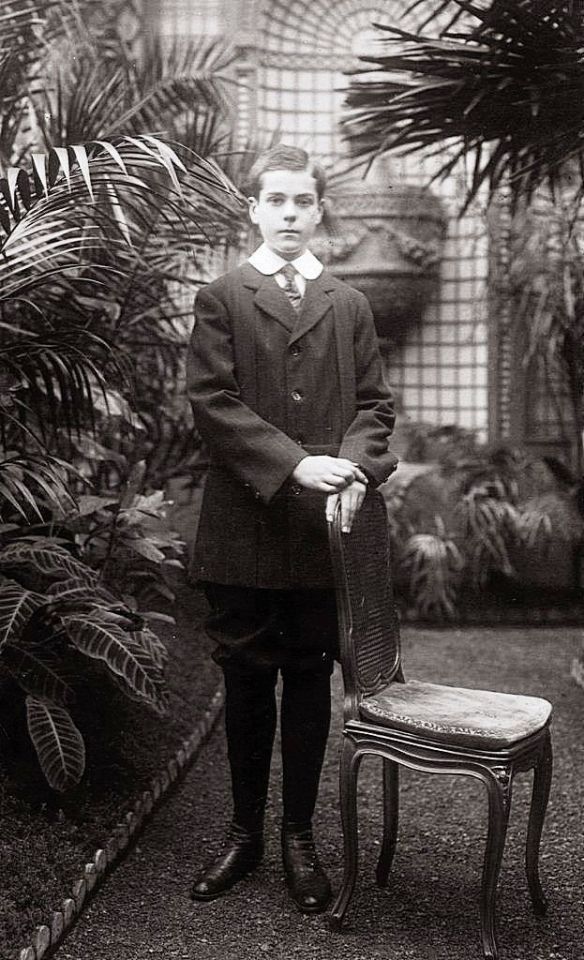

Vladimir Paley and his relationship with his sisters

The person who had the most lasting impact on Natalie's childhood was her brother Vladimir, who had all the talents. So much so that throughout her life, she searched for imitations of Bodia - who over time became to her the very essence of masculine perfection in most of her friends.

“He read to us plays by Edmond Rostand, The Blue Bird by Maeterlinck, extracts from Rabindranath Tagore and naturally his own works,” remembers Princess Irène Paley . “He wrote small plays for us, drawing the costumes, brushing the sets, adjusting the lighting. He played works of his own composition for hours on the piano." As Jacques Ferrand recalls, in the portrait that he paints of himself, one might have believed at first glance that he was an affected and spoiled child whereas in reality he had great maturity, very unusual for his age.

His parents, and particularly his mother, to whom he was very close, always encouraged his rare gifts. "From childhood, he wrote verses of which he had nothing to be ashamed of - some of his works can be compared to those of Pushkin", Prince Félix Youssoupoff assured, translating the general opinion with these words, "painted and played the piano like a virtuoso." An ideal big brother. If we add to so many intellectual qualities his Narcissus looks, then we have a precise idea of his personality. (...)

Vladimir was a source of joy for everyone. Grand Duke Paul himself, so often lost in thought, laughed a lot in her presence. He liked to leaf through the album of caricatures made by Bodia, who always caught everyone's faults, starting with his own.

Concerning Irene and Natalie, we owe him the most revealing text, the most psychologically accurate, as to the links which united them: "This year, Iricha is doing her devotions for the first time. She came with us to church without Natacha who didn't know what to do at home. We took her for a walk but she still seemed bored." Since it was always Iricha who was 'the leader', Natacha had difficulty being without her older sister, and what's more, they were not used to living apart. When one of them was ill, the other wandered sadly, like a shadow around the house, but when they played together in the garden, they invariably fought but resumed their games after five minutes, as if nothing had happened. As the popular saying goes: “Together we feel cramped and apart we feel bored.”

Until 1913, when Natalie was eight years old, Bodia shared his parents' exile then, with the authorization of Tsar Nicholas II, he returned to Russia in order to complete his education in the Corps des Pages; he was left with little choice... a career as an officer in the family tradition. From then on, his two sisters impatiently awaited his return to Boulogne, dressed in his dark blue uniform with golden frogs and peaked helmet with a white mane.

The direction given to Vladimir's studies is surprising, because nothing about his nature predisposed him to such a change of heart [from his artistic inspirations]. This choice had the stamp of Grand Duke Paul, who, unlike his wife, "didn't understand the qualities which gave his son all his value"; moreover, his somewhat bohemian tendencies surprised him and, perhaps, also worried him slightly. Time proved him right. Bodia, separated from his family, far from the adoration his mother and sisters bestowed on him, took full advantage of the contact with other boys his age and the merciless discipline of the Corps des Pages. He became more natural, more spontaneous, while never neglecting his different passions. His departure was the first heartbreak of Natalie's childhood.

Princess en Exile - Jean-Noel Liaut

#romanov#paul alexandrovich#imperial russia#imperial family#royalty#olga paley#natalie paley#irina paley#vladimir paley#royalty in exile#paris#belle époque

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! So I was just rewatching the movie Romanovs an Imperial Family and I noticed that at Tobolsk they (the guards) took pictures of the family (front and side profiles) and I was also just watching Nicholas and Alexandra (1971) and I noticed that they also took pictures at Tobolsk. Did this happen in real life or is it just a myth? (If it’s a myth you can put it on the list for your series :)

Thank you!

Hi! Thank you so much for your question lovely! It made me dig a lot deeper into whether this was actually true and I am pleased to say that it isn't a myth, but something that actually happened. Here are some details!

Pierre Gilliard's diary mentions the family having to have identification photos taken. On 17 September 1917 he wrote that "ID cards with numbers, equipped with photographs" were taken of the family. According to Paul Gilbert, who runs the Nicholas II website and has a great article about this, Alix also wrote about this in her diary.

Pierre Gilliard also wrote about this in his memoir Thirteen Years at the Russian Court, Page 286:

In September Commissary Pankratof arrived at Tobolsk, having been sent by Kerensky. He was accompanied by his deputy, Nikolsky—like himself, an old political exile. Pankratof was quite a well-informed man, of gentle character, the typical enlightened fanatic. He made a good impression on the Czar and subsequently became attached to the children. But Nikolsky was a low type, whose conduct was most brutal. Narrow and stubborn, he applied his whole mind to the daily invention of fresh annoyances. Immediately after his arrival he demanded of Colonel Kobylinsky that we should be forced to have our photographs taken. When the latter objected that this was superfluous, since all the soldiers knew us—they were the same as had guarded us at Tsarskoie-Selo—he replied: " It was forced on us in the old days, now it's their turn." It had to be done, and henceforward we had to carry our identity cards with a photograph and identity number."

It's worth mentioning that all the staff that worked at the palace before the Revolution did indeed have to carry ID passes with photographs.

We have a brilliant example of what one of these passes in Tobolsk might have looked like in the form of passes for Botkin and Demidova, which are now Museum of the Family of Emperor Nicholas II in Tobolsk. I sadly couldn't find Demidova's, so have just attached Botkin's.

Captioned: 'Identity card (pass) E. S. Botkin for the right to enter the house number 1 (“Freedom House”) dated November 6, 1917.'

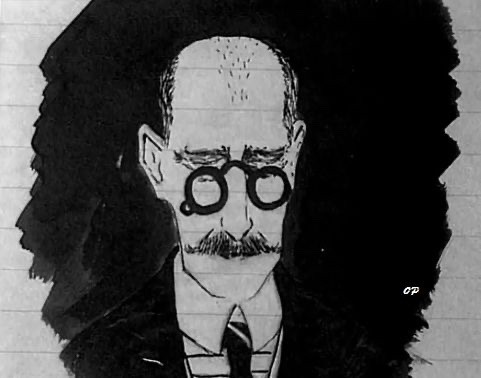

Which brings me on to a lady named Maria Mikhailovna Ussakovskaya. For clarification, I don't know if she was the person who took the photos for definite, but she was a prominent photographer in the area and could have been hired to take the photos. She did 100% have some connection to the Romanov family, as I'll explain later.

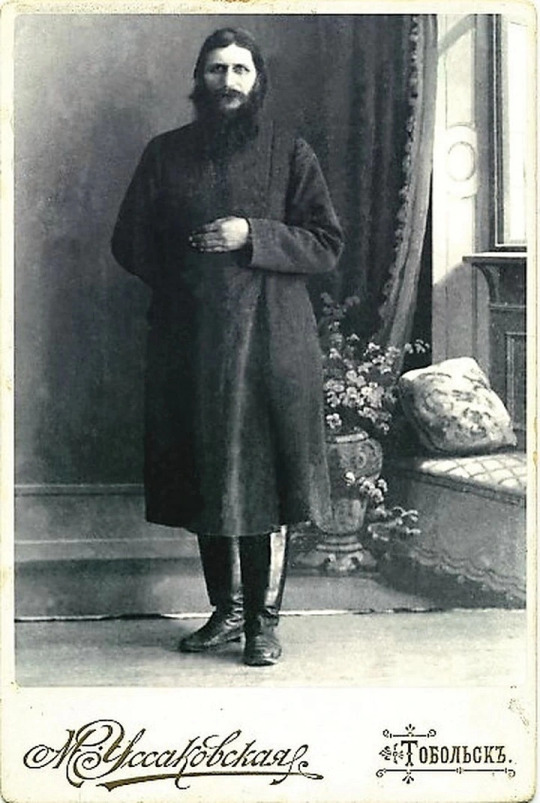

Maria was a photographer in Tobolsk, in fact she was the first woman photographer from the region that operated professionally, and she had her own salon. She even photographed Rasputin - you can see her surname embossed on the cabinet card here, reading Уссаковская

She photographed the family's entourage, too, as the staff were able to move freely about Tobolsk. Shown here are (left-right): Catherine 'Trina' Schneider, Count Ilya Tatishchev, Pierre Gilliard, Countess Anastasia 'Nastenka' Hendrikova, and Prince Vasily Dolgorukov. Note Maria's surname embossed again onto the card, showing it was taken and produced at her salon.

Invoices for the family show that the Romanovs had several payments sent to Ussakovskaya for postcards and "correcting negatives", so we know that there definitely was a relationship between the two parties. She took photos of the exterior of the house in Tobolsk, and postcards were sent by the Grand Duchesses showing the house, so they might have used her photos.

Letter sent from Maria to Nikolai Demenkov, her 'crush'

Which then begs the question of what happened to these ID photos...

Apparently, Maria Ussakovskaya's daughter Nina owned some photographic plates of the Romanov family. It's not explained whether these were casual photos taken of the family, or ID photos, but according to Paul Gilbert "in 1938... fearing arrest, [Nina] destroyed all the photographic plates".

Owning any Romanov or Tsarist related items, including photographs and postcards, was an arrestable offence. The rise of the gulags in the 1930s with the Stalinist regime probably prompted Nina to destroy what she owned.

Personally, I don't have much hope that any of the photos of the family will ever turn up. But there is always a small chance, I suppose :)

To conclude: yes, this happened, photos were definitely taken of the family for identification passes. Pierre Gilliard is a trustworthy source and the fact that it was written in his diary and also Alix's diary is pretty much concrete evidence. The existence of Maria Ussakovskaya and her association with the family also points towards this, alongside the bills and invoices sent to the family at Freedom House.

Maria with her husband, Ivan.

SOURCES:

The woman who photographed the Imperial Family in Tobolsk by Paul Gilbert

Thirteen Years at the Russian Court by Pierre Gilliard

#q#ask#answered#OTMA#Romanovs#Romanov family#Tobolsk#Freedom House#Exile#Captivity#Eugene Botkin#Evgeny Botkin#Anna Demidova#Pierre Gilliard#Alexandra Feodorovna#Maria Nikolaevna#sources#Thirteen Years at the Russian Court#my own

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

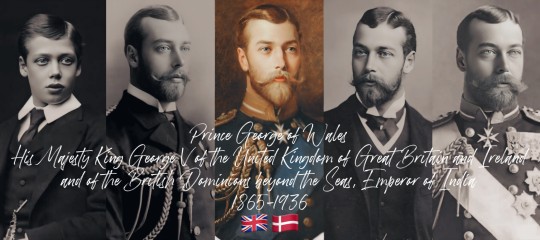

"The Monarchs of Queen Victoria’s Legacy"

Wilhelm II was the first of Queen Victoria's grandchildren to ascend to a throne, becoming German Emperor in 1888. His reign initiated the lineage of monarchs descended from Victoria. The last to be crowned was Marie of Romania in 1914, marking the end of an era for Victoria's royal progeny.

Queen Maud of Norway holds the distinction of having the longest tenure as Queen Consort among Queen Victoria's grandchildren, with a reign that spanned 33 years. Her time on the throne was characterized by a harmonious blend of British heritage and Norwegian culture, leaving a legacy of benevolence and cultural patronage. Conversely, Queen Sophia's role as Queen Consort of the Hellenes was the briefest, lasting just about 4 years due to the political upheavals of World War I and Greece's National Schism, which led to her husband's abdication. Despite the short span, her resilience and dedication to her royal duties remained unwavering.

The execution of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna was a deeply tragic event, reflecting the brutal reality of the Russian Revolution. On the night of 16-17 July 1918, she and her family were executed by Bolshevik revolutionaries in Yekaterinburg. Alexandra witnessed the murder of her husband, Tsar Nicholas II, before she herself was killed with a gunshot to the head. The violence of that night brought an abrupt and grim end to the Romanov dynasty, extinguishing the lives of the last imperial family of Russia in a stark and merciless manner. Her death marked the first among Queen Victoria’s crowned grandchildren. In contrast, Queen Victoria Eugenie of Spain lived through the upheavals of the 20th century, witnessing the restoration of the Spanish monarchy. She passed away in 1969, the last of Victoria’s crowned grandchildren, her life reflecting the dramatic changes of her time.

George V’s United Kingdom, a realm where tradition blends with modernity, continues to stand firm. The monarchy, a symbol of continuity, has weathered the storms of change, its crown passed down through generations, still reigning with a sense of duty and connection to the people.

Maud of Norway’s legacy endures in the serene beauty of Norway, where the monarchy remains a cherished institution. Her reign, characterized by a quiet strength and a nurturing presence, is remembered fondly, and the royal house she helped establish continues to flourish.

Margaret of Connaught’s Swedish monarchy, into which she married, stands resilient. Though she never became queen, her descendants uphold the traditions and values she embodied, maintaining the monarchy as a pillar of Swedish national identity.

Victoria Eugenie of Spain saw the Spanish monarchy navigate the tumultuous waters of the 20th century, enduring a republic and a dictatorship before being restored. Today, it stands as a testament to resilience, with her bloodline still on the throne, embodying the spirit of reconciliation and progress.

In stark contrast, the fates of other monarchies were marked by tragedy:

Wilhelm II witnessed the fall of his German Empire in the aftermath of World War I. His abdication marked the end of an era, and he spent his remaining years in exile, a once-mighty emperor without a throne, reflecting on the lost glory of his realm.

Sophia of Hellenes experienced the disintegration of the Kingdom of Greece amidst political upheaval. The monarchy, once a symbol of national unity, was abolished, leaving her and her family to face the harsh reality of a world that had moved beyond the age of empires.

Alexandra Feodorovna’s Russian Empire crumbled during the Bolshevik Revolution. The tragic end of the Romanov dynasty saw her and her family executed, their fates sealed by the tides of revolution that swept away centuries of monarchical rule.

Marie of Romania’s kingdom, once a beacon of hope in the aftermath of World War I, eventually succumbed to the forces of history. The monarchy was abolished after World War II, and the royal family faced the stark reality of a republic.

#wilhelm ii#Marie of Edinburgh#Marie of romania#George v#alix of hesse#alexandra feodorovna#Margaret of connaught#Margaret of Sweden#Victoria eugenie of Spain#Sophia of Prussia#Sophia of Hellenes#Sophia of greece#queen maud#princess maud of wales#Victoria eugenie of battenberg

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sunderland's Royal Jewel Vault (19/∞) ♛

↬ The Glencairn City of Warwick Fringe Tiara

Like their mainline cousins, the Glencairn branch of House Warwick has gathered quite the jewellery collection over the past seventy years. The City of Warwick Fringe Tiara is one of the oldest in their extensive collection. When Lady Esther Jungman (1926 - 1988) married the youngest son of King George II in 1954, the royal family did not skirt the costs, as it was the first royal wedding since the end of World War Two. Plus, Esther was no stranger to the royal lifestyle, she was a great-granddaughter of King George and Queen Alexandra. Esther's maternal grandmother was the ill-fated Grand Duchess Anastasia Georgiyevna (1873 – 1919), who was renowned for her irreplaceable jewel collection. This made Esther a great-niece of Tsar Nicholas II—and a second cousin of her husband-to-be. The twenty-eight-year-old bride was described as extremely beautiful, with quantities of dark hair, wide-set blue eyes, and a slightly retroussé nose. Wedding gifts were shipped in from across the world, each befitting for a quasi-Romanov princess. The most notable gift was from the City of Warwick itself: the tiara Esther used to secure her wedding veil. The tiara was modelled after a similar piece, the only tiara Esther's mother, Grand Duchess Natalia Georgiyevna (1902 - 1977), retained after the Russian Revolution forced her into exile. Like her mother's the fringe tiara featured rounded spikes set with diamonds. Esther was emotionally moved by the gift, thanking the city's mayor several times. Following the wedding, the new Duchess of Glencairn reached for the tiara frequently, sporting it at state visits, galas, and at the inauguration of her brother-in-law, King James II (1915 - 1970). Esther adjusted to royal life well, even after her husband was killed in a 1962 plane crash, she continued a wide variety of work. Thirty years after Esther's wedding, the tiara graced the head of another royal bride. Esther's middle daughter, Princess Frances, wore the tiara to marry Lee Wayne Grierson (1948 - 2024) in 1983. The televised wedding was attended by several prominent guests, including King Louis V, who walked the bride down the aisle. Unfortunately, Esther died before the 1998 wedding of her youngest daughter, Princess Valerie, who ended up inheriting the tiara. This wedding was more lowkey—greatly overshadowed by the wedding of her cousin James, Prince of Danforth to Lady Tatiana Farnsworth—but all the same, Valerie honoured her late mother by wearing the tiara to her wedding reception in New York City. The tiara stayed with Valerie and she wore it as much as circumstances would allow, including for several portraits taken in the '00s. To this day, the tiara continues to be one of the most recognizable tiaras from the Glencairn collection, reminiscent of an empire lost to history.

HRH Esther, Duchess of Glencairn wears the tiara in a 1957 portrait

HRH Princess Valerie of Glencairn wears the tiara in a personal photograph from 2005

#warwick.jewels#ch: valerie#ch: esther#ts4#ts4 story#ts4 royal#ts4 storytelling#ts4 edit#ts4 royal legacy#ts4 legacy#ts4 royalty#ts4 monarchy#ts4 screenshots#warwick.extras

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Are we going to talk about the fact that the Romanov murders/assassinations changed the course of history so drastically that modern history would not be what it is without July 16, 1918??? Like the historical domino effect is so crazy. If they were never murdered Russia most likely would not have fallen to communism and the royals would have likely been reinstated, possibly with a more constitutional monarchy, as they had kinda tried before. I mean the White army was SO close to Yekaterinburg, I really do think if Yakov Yurovsky hadn’t assassinated them that night the White army probably would have saved the family and won the civil war. If Russia hadn’t fallen to communism then most likely WW2 would have never occurred and communism probably wouldn’t have spread to Europe and across the world. This means that the Cold War basically wouldn’t have happened. No arms race and no nuclear weapons. Our world would be SO different. Heck, I’ll go as far as to say JFK probably wouldn’t have even been assassinated if the Romanovs weren’t assassinated first. If there was no Cold War, his administration most likely would have been focused mainly on civils right and it wouldn’t have given Lee Harvey Oswald any type of weird communist motive to kill him, because communism wouldn’t have been as widespread. It’s just crazy when you look at all of the things in history that can be directly traced to their assassination. Who would have known the murders of two monarchs and their four young children would have such an impact. To think so much grief could have been spared if the Romanovs were just sent into exile instead of being murdered. None of them deserved their horrible fate.

#history nerd#history#roman empire#romanovs#jfk#60s#ww1#ww2#rant post#just thinking#imperial russia#I get so sad everytime I think of The Romanov sisters#being the same age as Anastasia was when she died has made me contemplate everything#vintage#jackie kennedy#kennedy

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

I was trying to think about sorts of job an ex-nobleman might have.

The noble class of his country was abolished, but he still married into wealthy family (which hadn’t been noble) known for business - and I kind of figure that noblemen who weren’t in line to inherit estate/title/government positions would need jobs anyway.

A lot of former nobles tend to go into business such as fashion (the fashion house Irfe), hotels, finances etc, generally things they have an idea about. Of course, there are other jobs nobles in exile took such as taxi drivers. Helen Rapport's book After the Romanovs might be of interest to you.

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I'm creating a Romanov roleplay so could you give me a list of members and friends of the Romanov family, and others (Standart officers, Bolsheviks, etc.) for people to roleplay? That would be very helpful since I know I'm going to accidentally miss some characters (^^”).

Hi! These are some people who were involved with the Romanovs:

Friends:

Anna Vyrubova—quite possibly Alexandra's dearest friend. Typically viewed as a bit of a simpleton or a cunning spy--the reality is probably that she was neither. Also very attached to Rasputin.

Lili Dehn—another of Alexandra's friends, a lady-in-waiting. Also close with Nicholas and the children; was with Alexandra when Nicholas abdicated.

Elizabeth Naryshkina—the elderly mistress of the robes.

Sophie Buxhoevedon—lady-in-waiting, affectionately known as "Isa" (also spelled "Iza").

Catherine "Trina" Schneider—also attempted (unsuccessfully) to teach the Romanov sisters German. Taught Russian to Alexandra. Lutheran.

Grigori Rasputin—infamous. Especially intimate with Alexandra, also a sort of mentor for the daughters. Killed in 1916.

Kolya Demenkov—Alexei’s friend.

Gleb Botkin & Tatiana Botkina—the children of Evgeny Botkin.

Sofia Orbeliani—Alexandra’s friend and an invalid. Died in 1915.

Countess Anastasia “Nastenka” Hendrikova—family friend.

Family:

Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna—OTMA's grandmother. But a bit frosty in her relations with Alexandra.

Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna—Nicholas II's sister. Often the grand duchesses spent Saturdays with her.

Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna—Nicholas’s sister. Her family was known as the Ai Todories due to their estate. Her daughter Irina especially was close to the daughters. (Irina’s husband, Felix Yussupov, was one of Rasputin’s assassins.)

Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich—one of Nicholas’s favorite cousins, and once considered a possible groom for Olga. Under the care of Elizabeth Feodorovna. One of Rasputin’s assassins.

Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna—Alexandra’s sister. Became a nun after her husband Sergei’s assassination in 1905; sent coffee and chocolate to the family during imprisonment. Murdered by the Bolsheviks.

Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich—Nicholas’s brother. Married morganatically and exiled. Saw Nicholas before Nicholas’s departure to Tobolsk. Also murdered by the Bolsheviks.

Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich—commander in chief of the Russian army during WWI until Nicholas II took over. Not liked by Alexandra due to his dislike of Rasputin.

Tutors/Staff:

Pyotr Vasilievich Pyotrov—the Russian tutor, known as "PVP."

Pierre Gilliard—the French tutor, especially close to Alexei. Often called "Zhilik" or "Monsieur."

Sydney Gibbes—the English tutor, often known as "Sig."

Sofia Tyutcheva—Known as "Savanna," OTMA's unofficial governess when they were young. Outspokenly against Rasputin, and not popular with the Romanovs' other friends.

Margaretta Eagar—OTMA's Irish governess, dismissed in 1904.

Anna Demidova—lady-in-waiting who accompanied the family and was eventually killed with them. Known as “Nyuta.”

Aloise (Alexei) Trupp—footman who was killed with the family; unique in that he was Latvian, and Catholic.

Ivan Kharitonov—cook killed with the family.

Leonid Sednev—companion of Alexei during captivity, eventually sent away by Yakov Yurovsky.

Eugene Botkin—doctor (primarily Alexandra’s). Killed with family.

Nagorny and Demenkov—Alexei’s “sailor nannies.” Only Nagorny continued on with the family to Tobolsk.

Standart Officers of Note:

Pavel Voronov—Olga's love interest in 1913. She wrote of him as "S." in her diaries.

Alexander Konstantinovich Shvedov—Also Olga's love interest in 1913, took place before Voronov. Referred to as "AKSH" in diaries.

Viktor Zborovsky—Anastasia's crush. She also exchanged letters with his sister Ekaterina "Katya" in captivity. Nicholas's favorite tennis partner.

Patients during WWI/Nurses, Doctors:

Dmitri Shakh-Bagov—Olga's love interest. Known as "Mitya."

Dmitri Malama—Tatiana's love interest. Gave her a dog known as Ortipo, named after his cavalry horse.

Valentina Cheborateva—OT’s friend and fellow nurse.

Margarita Khitrovo—fellow nurse and friend. Known as “Ritka” or “Rita.”

Dr. Vera Gedroits—female doctor. Known as “Princess Gedroits.” After the tsar’s abdication, her behavior turned increasingly unconventional.

Vladimir Kiknadze—Tatiana’s love interest after Malama. Considered a dangerous flirt by the other nurses and doctors.

Politicians:

Sergei Witte—Served as prime minister 1905-1906.

Pyotr Stolypin—Served as prime minister 1906-1911. Sofia Tyutcheva, Nicholas II, and OT were there at his assassination.

Mikhail Rodzianko—state chairman of the Duma, 1911-1917.

Bolsheviks/Captors, etc.:

Alexander Kerensky—member of the Provisional Government. Oversaw the Romanovs’ house arrest.

Eugene Kobylinsky—commandant during house arrest; nevertheless on good terms with the family.

Vasily Yakovlev—commissar, searched the house at Tobolsk; helped transfer the family to the Ipatiev House at Ekaterinberg.

Alexander Avdeev—commandant at the Ipatiev House.

Yakov Yurovsky—commandant at the Ipatiev House after Avdeev. Orchestrated the murders.

Pyotr Ermakov—one of the executioners, his accounts of the Romanovs and their murder are highly exaggerated and untruthful. Was drunk on the night of the murders.

Ivan Skorokhodov–despite the rumors there is no reliable evidence to support the idea of a liaison with Maria. However, he was really a guard at the Ipatiev House.

#imperial russia#history#anna vyrubova#lili dehn#sophie buxhoevedon#rasputin#maria nikolaevna#romanovs

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In 1913, the Romanovs celebrated the tercentenary of the dynasty's rise to power. As expected, the planned festivities were glorious. The previous years had been one of prosperity, the industrialization continued to evolve and this economic flourishing made it possible to celebrate the family's success grandly. Politicians and aristocracy hoped that the memory of great figures of the past could strengthen the unity of the nation around the Tsar. The Imperial family left Tsarskoye Selo for the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg for celebrations that began on March 6 with a te-déum in Kazan Cathedral. The following days were full of ceremonies and festivities for the Tsars, whether receiving delegations from all parts of Russia in typical costumes, or going to balls. Alexandra attended in a court dress and wearing the Kokoshnik, the traditional head arrangement of Russian women. The daughters wore white dresses with the ribbon of the Order of St. Catherine, and all the Grand Dukes were present. Olga and Tatiana, "the big pair", already attended parties as adults and could wear beautiful long dresses. Even the Faberge egg that Nicholas gave to Alexandra that year honored the dynasty. Decorated with images of all the Romanov Tsars, it had inside as a surprise two maps of Russia, one from 1613 and the other from 1913. In May, the family boarded a ship to Kostroma in order to repeat the steps of Michael, the first Tsar of the family, from the Ipatiev monastery, where he lived, to the throne. Everywhere, peasants greeted the procession effusively, even entering the water of the Volga River to get a closer look at them or throwing themselves to the ground to kiss Nicholas's shadow. The best part of the celebration took place in Moscow, when Nicholas crossed Red Square alone and entered the Kremlin with the sound of the prayers of the priests lined up along his way. According to protocol, both the Empress and the heir were to walk behind the Tsar, but Alexei, again ill, had to be carried by one of his sailors. The success of the celebrations strengthened the belief, especially for Nicholas and Alexandra, that the autocracy remained strong and had support from the people. On the other hand, the Duma Liberals still insisted on reforms, not finding ears in the Tsar and his ministers. And behind all this, opponents of the regime continued to act, even in exile."

The Last Tsars | Paulo Rezzutti

(loose translation)

#facts#tsar nicholas ii#tsarina alexandra#grand duchess olga#grand duchess maria#alexei nikolaevich#tatiana nikolaevna#grand duchess anastasia#otma#otmaa#naotmaa#tercentenary#my own#tsar#tsarina#romanovs#grand duchess#tsarevich#the romanovs#alix of hesse#nicholas romanov#russian history#xx century#grand duchess tatiana#tsarevich alexei

49 notes

·

View notes

Note

What was Tsar Nicholas's relationship with other Grand Dukes? Which one did he not like and which ones did he greatly respect and admire?

Assuming you mean Nicholas II:

Among his uncles, Nicholas was not very fond of Vladimir Alexandrovich, because the latter had a very forceful personality and intimidated Nicholas. They also had a great conflict over Kyril´s marriage, which resulted in Vladimir shouting at Nicholas and even tearing off his epaulettes and throwing them into the Tsar´s face.

With Grand Dukes Sergei and Pavel Nicky had a good relationship, especially because he was very fond of their wives, but Sergei was later murdered and Pavel, after the death of his first wife, married a commoner without Nicholas´ permission, thus earning exile and the relationship was pretty much completely severed, up until the revolution.

His favourite uncle was Grand Duke Alexei. We know him as a person who loved life and was pretty much useless when it came to doing any meaningful work, either in politics or Navy, in which he had the post, but he was funny, always kind to Nicholas and pretty much an antithesis to Vladimir. Tsarevich Alexei was named after him.

When it came to cousins and other Grand Dukes, with most of them nicholas had good and even close relationships when he was younger, but as the time went by and the Imperial family closed off themselves (because of Alexei´s hemophilia and other issues) from the rest of the Romanovs, most of those relationships deteriorated. Mikhail Alexandrovich and Kdyril Vladimirovich married without permission and pretty much against the family law. Boris and Andrei Vladimirovichi were good for nothings with loose morals. Sandro had distinctly different political (and other) views (and frankly suffered from a big head, especially in later years).

The favourite relatives, besides Grand Duke Alexei, who died in 1905, were Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, whom both Nicholas and Alexandra, for the longest time, treated with great love and warmth , until the moment he involved himself with Rasputin´s murder, after which he pretty much ceased to exist to Alexandra and Nicholas had him banished (which ironically saved his life). The other great favourite was grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich (KR). His whole family remained close to the Tsar, his daughters being friends with OTMA, his sons serving during the war at the front and in the headquarters.

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

Wait what time the lore behind the coat in act 1? I've never heard of this.

i can't remember where i read this, but the idea behind the big brown coat anya wears for the entirety of act i is she basically steals it. off of a clothesline? a sleeping man in the street? a dead man in the street?? idk. it's a men's coat, it's too big and bulky on her, so she fashions it with a belt.

and aside from the coat, her blouse and skirt were designed to resemble the outfits the romanov girls were wearing in their exile and therefore their execution. so anya is basically wearing the outfit she 'died' in!

#asks#Anonymous#anastasia broadway#linda cho u slick bastard#and ppl wonder why we're still mad about the 2017 tonys

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The family lived happily in Paris a city Volodia loved - but they traveled often, mainly within France and to watering places in Germany." Several memories of these trips would later appear in Vladimir's writings, along with others belonging to places he longed for, such as Italy, Greece and Egypt.

Russia was still forbidden, even if Paul was allowed to attend the funeral of his brother Serge who was killed by a terrorist bomb in Moscow on February 4/17, 1905. His efforts to get similar permission for Olga Valerianovna to attend the promotion of her son Alexander Erikovich as an army officer in April that year were fruitless. A disappointed Paul wrote to Nicholas II:

"I beg you to change your decision. After all, no one except her children will see her, and she, poor thing, was so overjoyed at the thought of seeing them... I beg you, by all that is dear to you, not to deny me this request..."

The emperor didn't change his mind, and Paul had to travel alone. His stay in Saint Petersburg was quite short, and he didn't try to hide the fact that he felt deeply offended by his nephew's decisions.

"A Poet Among the Romanovs" - Jorge A. Sàenz

#romanov#paul alexandrovich#imperial russia#imperial family#royalty#exile#vladimir paley#irina paley#natalia paley#olga paley#nicholas ii

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

I swear I'm not like a monarchist or whatever. I don't really care about the Romanov family but I just listened to a History Tea Time about the four girls and it got me curious, so:

I personally think that WW1 so thoroughly killed the time of monarchs and heirs and "You can't leave the kids alive because they may grow up and amass an army to take back the throne" that history would not have been altered in a meaningful way if the family had been allowed to live in exile. Like I don't think they would have done anything, and I don't think if they had tried to stir the pot that enough of Europe would have been willing to die for it for it to have made any difference. I understand why a new political regime would have been cautious about it but I think it would have been better for them politically to just exile them without the whole martyrdom aspect, as well as more humane than killing kids that literally had nothing to do with creating the sins of the Russian monarchy

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

FOUR DAUGHTERS OF THE LAST TSAR OF RUSSIA...🤍🥀

Four daughters of tsar Nicholas II and the last imperial children of Russia!

in order: Olga, Tatiana, Maria and Anastasia✨️ They were known for their special personalities and their Golden hearts, as well as their tragic deaths...💔🥀

I have written their personality characteristics under their photos🫶🥰

Romanov sisters adored their only little brother, Tsesarevich Alexei, who was always sick due to his congenital disease of hemophilia...🥺🌟

In 1917, the Bolsheviks came to power and Romanovs were exiled to Siberia after 300 years of rule. The revolution that began with the massacre of Bloody Sunday by Tsar Nicholas II on January 22, 1905, ended in 1917 when the Bolsheviks came to power! and tsar Nicholas with his wife, Five children and 4 of his crew were shot in July 17, 1918... 💔 Their bodies were then taken to a remote forest where they were mutilated, dismembered and buried with grenades, fire and acid to avoid identification.

Age of family members at the time of execution: Nicholas II was 50 years old, Alexandra Feodorovna was 46 years old, Olga was 22 years old, Tatiana was 21 years old, Maria was 19 years old, Anastasia was 17 years old, Alexei was 13 years old.

Their burial place was discovered by amateur detectives in 1979, and in 1998, 80 years after the execution, the remains of the Romanov family were buried in a state funeral in the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg!

In 2007, a smaller grave containing the remains of the two missing Romanov children from the larger grave was discovered by amateur archaeologists. DNA analysis confirmed they were the remains of Alexei and one of his sisters.

During the 84 days following the murders in Yekaterinburg, 27 other friends and relatives of the emperor (14 Romanovs and 13 members of the imperial family) were killed by the Bolsheviks... 😥💔

On August 15, 2000, the Russian Orthodox Church announced that it had canonized the members of Romanov family for their "modesty, patience, and humility."

#olga nikolaevna#tatiana nikolaevna#maria nikolaevna#anastasia nikolaevna#Russian Imperial Family#russian royal family

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sunderland's Royal Jewel Vault (4/∞) ♛

↬ Georgiyevna Tiara

The Georgiyevna Tiara, also known as Grand Duchess Anastasia's Kokoshnik Tiara, was bought by Queen Matilda Mary in 1922 for the price of $47,807. The tiara was sold to the new queen by Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia, daughter of the tiara's original owner, Grand Duchess Anastasia Georgiyevna. Grand Duchess Anastasia, born Princess Adelaide of Sunderland, was a sister of Matilda Mary's husband, King Nicholas. The grand duchess was a huge admirer of jewellery and her collection became world-renowned for its size and value. Among her collection was a Bolin diamond tiara adorned with 23 cabochon aquamarines. Anya, as the grand duchess was called, received the tiara among several other gifts ahead of her 1894 wedding to Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich of Russia, a younger brother of Tsar Nicholas II. Like several of her Romanov relatives, Anya was imprisoned and eventually murdered following the Russian Revolution of 1917. Her jewels remained hidden in Petrograd until they were smuggled out of Russia, along with her surviving daughters, by Sunderlandian operatives. Over the next few years, Anya's daughters sold pieces of their mother's jewelry collection to support their lives in exile, with their aunt Matilda Mary making several large purchases to ensure certain jewels stayed within the family. Anya's ailing mother, Dowager Queen Alexandra, was heartbroken by the fate of her Russian family and forbade any of Anya's jewels to be worn in her presence. Following Alexandra's death in 1926, Matilda Mary began wearing the tiara for formal events and photographs. She had the tiara altered to accommodate drop pearls, which could easily be swapped with the original aquamarines. The tiara was passed down and eventually inherited by Queen Irene following the death of Queen Anne in 1973. Irene has worn the tiara consistently and it is rumoured to be her favourite tiara.

#warwick.jewels#ts4#ts4 story#ts4 storytelling#ts4 edit#ts4 royal legacy#ts4 legacy#ts4 royalty#ts4 monarchy#ts4 screenshots#✨#warwick.extras

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

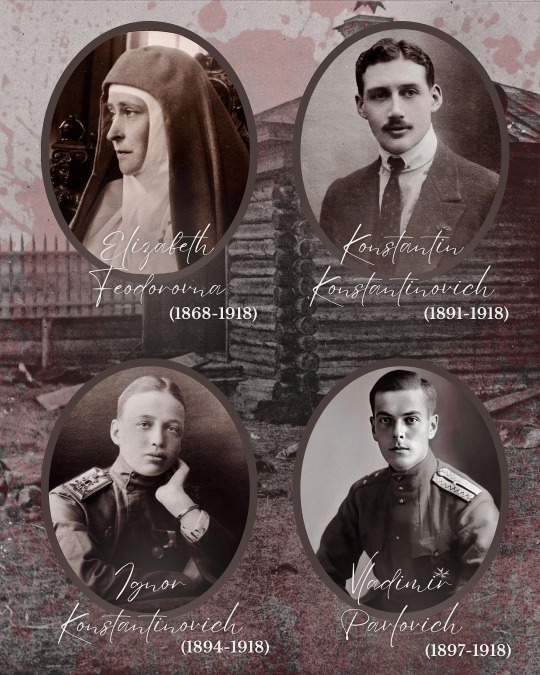

“Alapaevsk Martyrs” 18 July 1918

105 years ago, only one day after the brutal execution of the last Tsar and his family in Yekaterinburg, six more members of the extended Romanov family and two of their confidants met their tragic end in Alapayevsk.

In 1918, Lenin ordered the Cheka to arrest Elizabeth Feodorovna, the Empress’ sister. She was then exiled to different cities across Siberia, including Perm and Yekaterinburg, where she was joined by seven other people. On 20 May 1918, they were all transported to Alapayevsk, where they were imprisoned inside of a school.

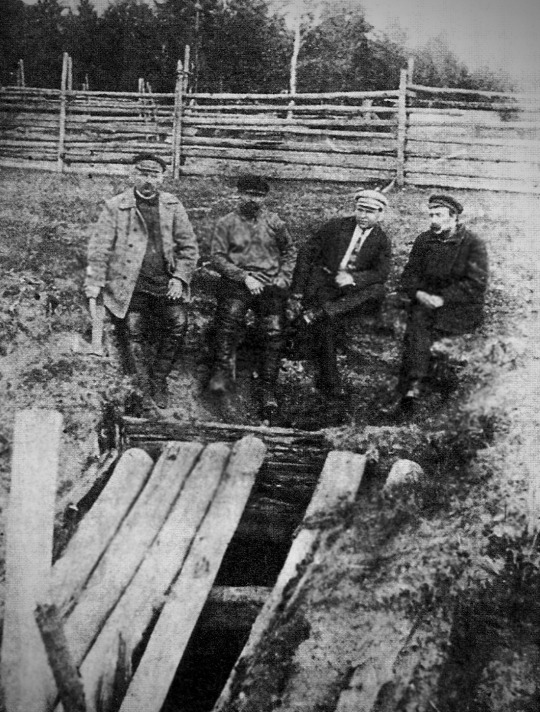

In the early hours of 18 July, the prisoners were awakened and driven in carts on a road leading to a close by village where there was an abandoned iron mine with a pit 20 metres deep. Here they halted. The prisoners were aggressively beaten up by the Cheka before being thrown into this pit. Hand grenades were then hurled down the shaft.

According to the personal account of one of the executioners, Elizabeth and the others survived the initial fall into the mine, prompting one of the executioners to toss in a grenade after them. Following the explosion, he claimed to have heard Elizabeth and the others singing an orthodox hymn from the bottom of the shaft. Unnerved, he threw down a second grenade, but the singing continued. Finally a large quantity of brushwood was shoved into the opening and set alight, upon which he posted a guard over the site and departed. The Bolsheviks tried to hide their tracks and blamed the crimes on an “unidentified gang”.

Cataverna (morgue) in St. Catherine's Church. Alapaevsk. 1918 ( The bodies of the Alapaevsk martyrs)

On 8 October 1918, White Army soldiers discovered the remains of Elisabeth and her companions, still within the shaft where they had been murdered. Despite having lain there for almost three months, the bodies were in relatively good condition. Most were thought to have died slowly from injuries or starvation, rather than the subsequent fire. Elisabeth had died of wounds sustained in her fall into the mine, but before her death had still found strength to bandage the head of the dying Prince John with her wimple.

The victims were first buried in the cemetery of the Russian Orthodox Mission in Beijing. In 1921, the bodies of Elizabeth and Varvara were moved to Jerusalem.

Source: marianikolaevnas

#elizabeth feodorovna#sergei mikhailovich#John Konstantinovich#Konstantin Konstantinovich#Igor konstantinovich#Vladimir Paley#Barbara yakovleva#Fyodor Remez#18 July 1918#1918#romanovs#Alapaevsk martyrs

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1961, Prince Alexander Nikitch, born in 1929, was the first Romanov to return to his family's former Empire after the Russian revolution and the exodus of what was left of the imperial family. He got a visa to join a group of tourists in the Soviet Union.

Alexander, a great nephew of Nicholas II, was the grandson of Grand Duchess Ksenia Alexandrovna and Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich (Sandro), respectively sister and cousin/brother-in-law of the last Tsar. He was the son of Prince Nikita Alexandrovich and Countess Maria Vorontsova-Dashkova, who belonged to one of the most illustrious and benefited families of the aristocracy. Alexander was nephew of Princess Irina Alexandrovna Yussupova, wife of the heir to imperial Russia's greatest fortune (Alexander visited his uncles' former residences).

Alexander must have aroused the curiosity of the Romanovs who witnessed the revolution and were going on with their lives in exile, including all their uncles, brothers of his father, Nikita.

posted to FB by Код 4 5 0

3 notes

·

View notes