#Eugene Botkin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Forensic facial reconstructions of Nicholas II (Skeleton 4), Alexandra Feodorovna (Skeleton 7), Olga Nikolaevna (Skeleton 3), Tatiana Nikolaevna (based on the conclusion that she was Skeleton 5), Anastasia Nikolaevna (based on the conclusion that she was Skeleton 6), Eugene Botkin (Skeleton 2), Anna Demidova (Skeleton 1), and Aloise Trupp (Skeleton 9).

#history#imperial russia#romanovs#olga nikolaevna#tatiana nikolaevna#anastasia nikolaevna#anastasia romanov#otma#romanov sisters#nicholas ii#tsar nicholas ii#alexandra feodorovna#forensics#facial reconstruction#eugene botkin#anna demidova#aloise trupp#romanov#romanov family#russian royalty

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! So I was just rewatching the movie Romanovs an Imperial Family and I noticed that at Tobolsk they (the guards) took pictures of the family (front and side profiles) and I was also just watching Nicholas and Alexandra (1971) and I noticed that they also took pictures at Tobolsk. Did this happen in real life or is it just a myth? (If it’s a myth you can put it on the list for your series :)

Thank you!

Hi! Thank you so much for your question lovely! It made me dig a lot deeper into whether this was actually true and I am pleased to say that it isn't a myth, but something that actually happened. Here are some details!

Pierre Gilliard's diary mentions the family having to have identification photos taken. On 17 September 1917 he wrote that "ID cards with numbers, equipped with photographs" were taken of the family. According to Paul Gilbert, who runs the Nicholas II website and has a great article about this, Alix also wrote about this in her diary.

Pierre Gilliard also wrote about this in his memoir Thirteen Years at the Russian Court, Page 286:

In September Commissary Pankratof arrived at Tobolsk, having been sent by Kerensky. He was accompanied by his deputy, Nikolsky—like himself, an old political exile. Pankratof was quite a well-informed man, of gentle character, the typical enlightened fanatic. He made a good impression on the Czar and subsequently became attached to the children. But Nikolsky was a low type, whose conduct was most brutal. Narrow and stubborn, he applied his whole mind to the daily invention of fresh annoyances. Immediately after his arrival he demanded of Colonel Kobylinsky that we should be forced to have our photographs taken. When the latter objected that this was superfluous, since all the soldiers knew us—they were the same as had guarded us at Tsarskoie-Selo—he replied: " It was forced on us in the old days, now it's their turn." It had to be done, and henceforward we had to carry our identity cards with a photograph and identity number."

It's worth mentioning that all the staff that worked at the palace before the Revolution did indeed have to carry ID passes with photographs.

We have a brilliant example of what one of these passes in Tobolsk might have looked like in the form of passes for Botkin and Demidova, which are now Museum of the Family of Emperor Nicholas II in Tobolsk. I sadly couldn't find Demidova's, so have just attached Botkin's.

Captioned: 'Identity card (pass) E. S. Botkin for the right to enter the house number 1 (“Freedom House”) dated November 6, 1917.'

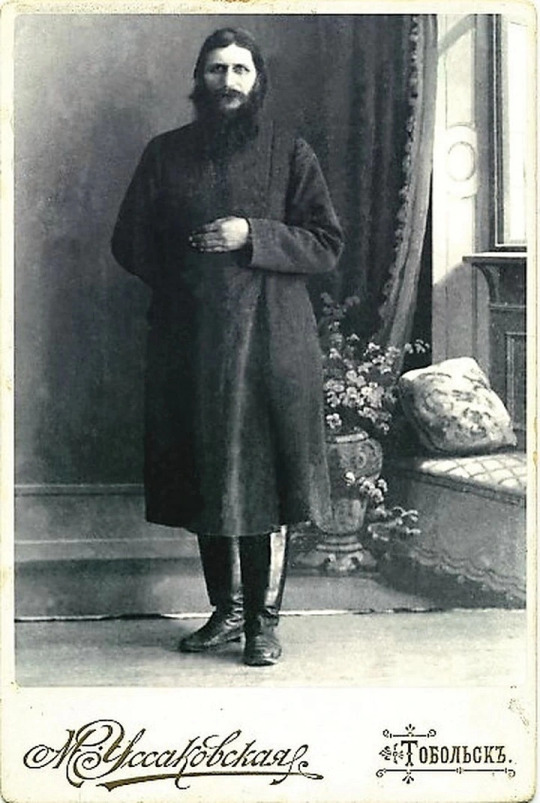

Which brings me on to a lady named Maria Mikhailovna Ussakovskaya. For clarification, I don't know if she was the person who took the photos for definite, but she was a prominent photographer in the area and could have been hired to take the photos. She did 100% have some connection to the Romanov family, as I'll explain later.

Maria was a photographer in Tobolsk, in fact she was the first woman photographer from the region that operated professionally, and she had her own salon. She even photographed Rasputin - you can see her surname embossed on the cabinet card here, reading Уссаковская

She photographed the family's entourage, too, as the staff were able to move freely about Tobolsk. Shown here are (left-right): Catherine 'Trina' Schneider, Count Ilya Tatishchev, Pierre Gilliard, Countess Anastasia 'Nastenka' Hendrikova, and Prince Vasily Dolgorukov. Note Maria's surname embossed again onto the card, showing it was taken and produced at her salon.

Invoices for the family show that the Romanovs had several payments sent to Ussakovskaya for postcards and "correcting negatives", so we know that there definitely was a relationship between the two parties. She took photos of the exterior of the house in Tobolsk, and postcards were sent by the Grand Duchesses showing the house, so they might have used her photos.

Letter sent from Maria to Nikolai Demenkov, her 'crush'

Which then begs the question of what happened to these ID photos...

Apparently, Maria Ussakovskaya's daughter Nina owned some photographic plates of the Romanov family. It's not explained whether these were casual photos taken of the family, or ID photos, but according to Paul Gilbert "in 1938... fearing arrest, [Nina] destroyed all the photographic plates".

Owning any Romanov or Tsarist related items, including photographs and postcards, was an arrestable offence. The rise of the gulags in the 1930s with the Stalinist regime probably prompted Nina to destroy what she owned.

Personally, I don't have much hope that any of the photos of the family will ever turn up. But there is always a small chance, I suppose :)

To conclude: yes, this happened, photos were definitely taken of the family for identification passes. Pierre Gilliard is a trustworthy source and the fact that it was written in his diary and also Alix's diary is pretty much concrete evidence. The existence of Maria Ussakovskaya and her association with the family also points towards this, alongside the bills and invoices sent to the family at Freedom House.

Maria with her husband, Ivan.

SOURCES:

The woman who photographed the Imperial Family in Tobolsk by Paul Gilbert

Thirteen Years at the Russian Court by Pierre Gilliard

#q#ask#answered#OTMA#Romanovs#Romanov family#Tobolsk#Freedom House#Exile#Captivity#Eugene Botkin#Evgeny Botkin#Anna Demidova#Pierre Gilliard#Alexandra Feodorovna#Maria Nikolaevna#sources#Thirteen Years at the Russian Court#my own

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

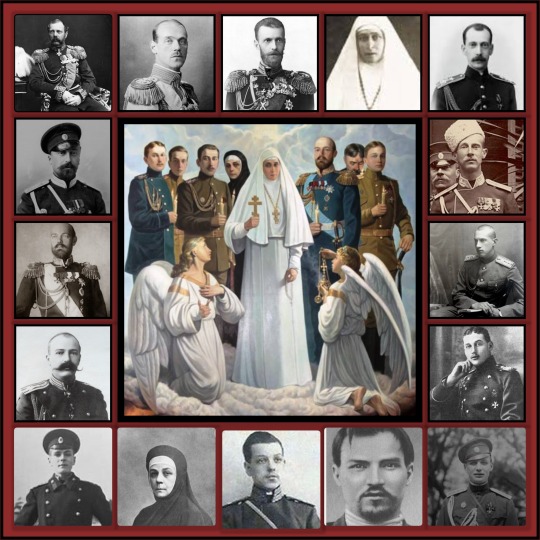

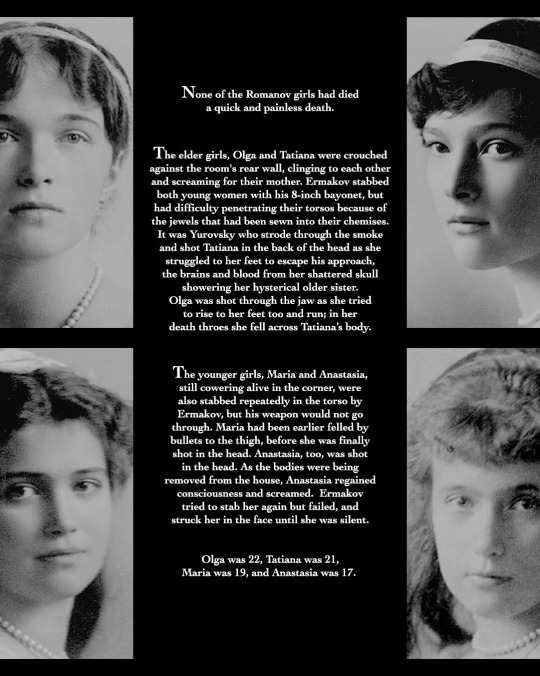

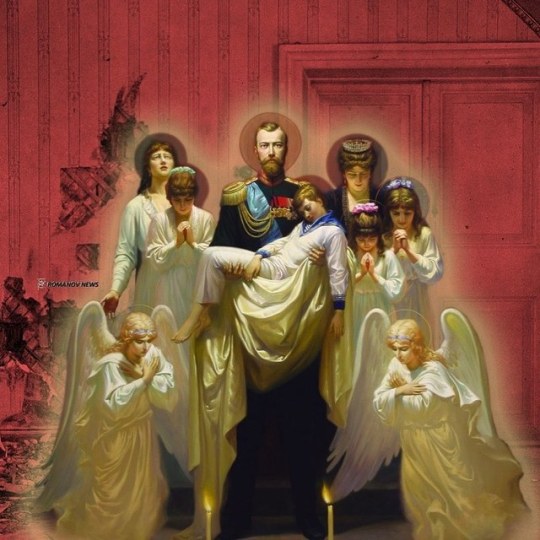

The Romanov Martyrs

I wanted to put together a little memorial that included all the members of the Romanov Family (as well as the members of their staff) that were murdered by the Bolshevik terrorists. This seems like a good week to keep them in our minds. Although we love and mourn the children especially, there were others we cannot forget.

Tsar Alexandre II was hunted down until finally blown to pieces.

Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna lost two sons and five grandchildren (no wonder she could not accept they were dead)

Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich was also hunted down and blown to pieces

Three Mikhailovichi brothers were murdered

Four Konstantinovichi were murdered, three of them brothers; I cannot imagine what their mother, Grand Duchess Elizabeth Mavrikievna, went through...and so on.

May they rest in peace.

#russian history#imperial russia#romanov family#Nicholas II#Tsar Alexander II#Empress Alexandra Feodorovna#Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna#OTMAA#Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich#Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich#Grand Duke Pavel Alexandrovich#Grand Duke Nicholas Mikhailovich#Grand Duke Georgiy Mikhailovich#Grand Duke Sergei Mikhailovich#Grand Duke Dmitry Konstantinovich#Prince Ioann Konstantinovich#Prince Igor Konstantinovich#Prince Konstantin Konstantinovich#Dr. Eugene Botkin#Anna Demidova#ivan karitonov#Akexei Trupp#Sister Varvara Yakolevna#Feodor Remez#mr. johnson

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

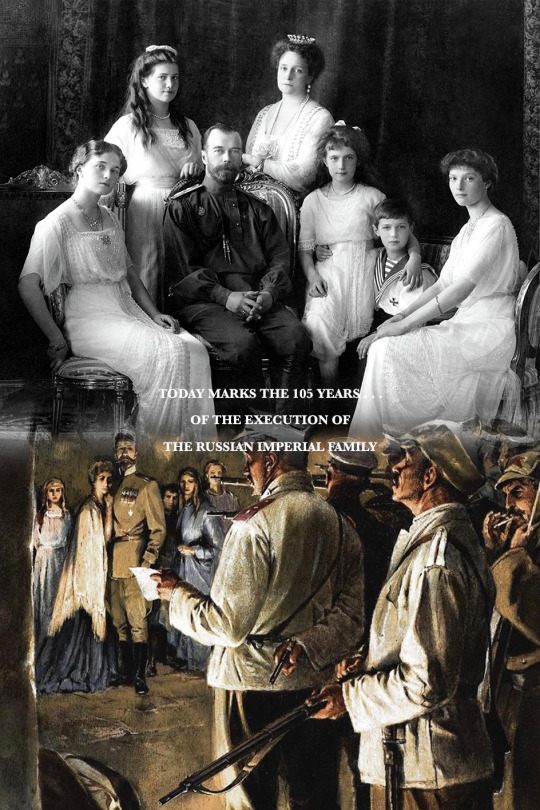

Execution of the Romanov Family

On this day, 105 years ago, the former Emperor of Russia, Nicholas II with his wife Alexandra Feodorovna, their five young children and four of their entourage: court physician Eugene Botkin; lady-in-waiting Anna Demidova; footman Alexei Trupp; and head cook Ivan Kharitonov, were murdered in the cellar of the Ipatiev House.

#romanovs#history#nicholas ii#alexandra feodorovna#olga nikolaevna#tatiana nikolaevna#maria nikolaevna#anastasia nikolaevna#alexei nikolaevich#myedits

178 notes

·

View notes

Note

Part two - Don't let the stars get in your eyes!

Featuring discussions of Romany/Travelers and their grishaverse versions, Eugenics (both characters oppose it), History and politics. Tws for period correct usage of what is now called autism. Self-internalized albleism mention also, as well as mentions of institutes. Tagging: @lordbettany, @corpsebasil

The best cutie boy!

The cold seeped into Cecily's chambers like CO2 poisoning. She sat swaddled in furs and blankets all while a fire roared in the hearth at her feet, but even that wasn't enough. She was used to the damp, yes. English homes were notoriously damp. But the chilling cold of eastern winters Ravka and Russia suffered from were an altogether different beast. Training in the Little Palace had been grueling and unrewarding. While Cecily had learned to fight in secret with communist squad-blocks in London's east End - a place where Princesses never went, Cecily did. Not because she wasn't like other princesses of her class, but because her tutors actively encouraged her to. They understood that she as a princess needed to be trained to fend off any attacker, whether they be a suitor or a minister. The price of her frail, feminine body, would always be at the hands of men for whom society refused to punish for their wandering eyes.

So, she'd done as much as Nikolai had done with Dominik - learned to fight the way peasant kids did, except her playmates were the sons and daughters of factory workers, lesser servants, immigrants from all over the Empire and the wider world. Of course, there was a lot of time that was spent breaking up fights over politics and the tenets of colonialism that seeped in through the cracks no matter class or creed.

It had been there that Cecily had gotten her nose broken for the first time. She'd been shoved down and held down, and forced her way back up. But the Little Palace's Grisha didn't fight dirty. There was an art to their movements, which Botkin trained them in. His broken Ravkan was more for show than anything, which once Cecily noted that, respected him much more. She admired the idea of subverting dominant stereotypes.

Now, as she sat there in her solar, pen between her teeth, light sparked between her clenched hands. It quickly flared out, and she dropped her head to her knees, sighing deeply. She'd been able to summon that blast-wave on the skiff through the Fold, then again the beam-burst when Vasily had tried to kiss her - the creep! She'd nearly blinded him, and cursed herself every day for not doing it fully. But Queen Tatiana's hoarse cries of Cecily being an abomination were sorely noted. She'd fled the ballroom, and come... here.

Her office. Her house of power. She'd attempted to answer some correspondence, looked over the pamphlets from the British Union of Fascists her spies in the palace had sent. Yet, nothing got done. Sighing, Cecily pressed her head back against the ottoman she was seated against, and chewed at the pen's tip.

"You'll ruin my pristine work, darling."

Cecily's head whipped toward the door and she saw Nikolai silhouetted in the entry, his gold hair the color of a summer sunset. The firelight softened his sharp lines and made the medals pinned to his uniform to be a molten gold.

"Come to take me back into that cage?" She growled, wanting to launch another beam-blast at her husband. They'd been married a week back, and now.... She felt only hatred towards him. He was loving, charming. Perfect. But she felt alienated even from him. Her powers had drawn up a glass box in which she was stuck inside, and everyone else goggled at her. COME SEE THE ENGLISH FREAK - SUMMONER OF SUNLIGHT AND SAINTS KNOWS WHAT ELSE! ALL FOR A BOB!

Shaking her head, Cecily groaned again. It was no good putting herself in the shoes of the travelers of the British Isles and Romany or those sideshow attractions that graced Brighton pier and brought gawking crowds to see the wonders of the Empire. It'd been happening for centuries, to support ideals of how one group was better than another. Simple human nature. And now nature involved summoning the bloody sun. She was a weapon of war, not political change.

"No, actually. I was worried about you." Nikolai shifted, his hand on the door-handle. Cecily dipped her head back, and sighed again. Waving her hand, she let him enter. "Does Ravka have a Romany population?"

"What?" Nikolai blinked, confusion furrowing his brows. He gripped his glass of pilfered brandy more tightly as his heeled dancing slippers clicked their way across the wooden floor. The slippers soon sank into the plush rugs scattered around her room, and Nikolai settled himself down beside her. "Well, do they?"

"There's the Suli." Nikolai took a sip of his brandy and grimaced, grumbling, "What is this дерьмо that Vasily says is Kerchian brandy?"

"Nikolai."

Sighing, Nikolai got up once more and examined her oaken and silver lacquered liquor cabinet. Upon finding the good Kerch brandy she'd kept stocked for herself when the goings got rough, Nikolai poured them both two snifters full and came back. "I've seen them, well..." Cecily gnawed her lip. "How the Ravkans see them."

"Fortune tellers." Nikolai scoffed. "There's some Suli in my crew, on the Volkvolny's sister ship, the Malenchlisa, who're part of the major operations on patrolling for slaver ships." "Don't most Suli traveling families end up in that horrific state?"

"Often." Nikolai sniffed. "Most of the time, the Tsar and court turn a blind eye. Since they're not seen as fully Ravkan-" He sighed at her dark glare. "-Don't question me on the morals of who is and isn't Ravkan - that's an anthropologist's job."

"Reeks of Eugenics," Cecily replied, flexing her hands. A ball of light pulsed between her palms, then sputtered out. "Dammit." She grumbled.

"Summoning going awry?" Nikolai noted her untouched snifter and sipped it. "Something's..." He reached to grip her hand, his fingers curling down to her wrist. Surprisingly, she didn't yank her hand back. Normally she hated being touched - but with Nikolai, she craved it. He held her in a way that made her feel safe.

"Did you know Eugenics as an idea has been around since Ancient Greece? It's only really gained ground in the latter century. Mind you, the latter half." Cecily shook her hands out and cast another ball of light. "And its regardless of political spectrum as well." She shook her head. "I-" Breaking off, she looked down at her hands. The hands that had held a brush and book steady since before she could walk. The hands that were able to piece together telephone parts. The hands that could summon light.

The hands that her doctors had said were the signs of her feminine frailness, and her...

You can't tell him. He won't understand!

But what if he does?

"What?" Nikolai murmured, tracing her thumb over her pulse point. "You're as white as a sheet."

"it's nothing." Cecily wanted to shoot to her feet, to run from the room. Whipping off her glasses, she pressed her palms to her eyes and sighed deeply. Remaining here, was good. Remaining in the present was the best possible option for her.

"Cecily." Nikolai murmured again, lifting her face by her chin to stare into her eyes. The firelight made sapphires of his baby-blue eyes, and she gasped instinctively.

"You shouldn't shut me out, love. What's yours is mine. Tell me, or don't. This is supposed to be a partnership, and yet you shut yourself away from me. I don't want to be your enemy, lapushka. Please, let me in."

"I-I'm..." Cecily's eyes pooled with tears and she buried her face in her knees. The silk of her scarlet evening gown was scratchy against her face, and she lifted her head rapidly to no longer feel the awful texture under her hands.

"I have what doctors call autism, but medical journals refer to it as Childhood Schizophrenia. The things..." She rubbed her hand over her cheeks, and sniffled. "The things they say..."

"Are awful." Nikolai interlaced his fingers with hers. He rubbed her palm with his thumb, and a ball of light bloomed there. Cecily blinked and held her breath.

"I've read those reports. Ravkan doctors have access to the works of both Hans Asperger and Grunya Sukhareva. What they suggest..." He shook his head again. "Is that why your father sent you here?"

"I asked to come here. He was suggesting..." She shook her head again. Panic bottled up in her throat and she whimpered, rocking back and forth on the balls of her feet. Nikolai moved to hold her, yet not restrain her. His hands were clasped on her shoulders, but not tightly enough to dig into her flesh.

"Take your time." He gently rubbed his thumbs over the expanse of bare skin her sleeveless gown offered, and Cecily shuddered as tears poured down her face.

"He wanted to have me put into an institute to deal with my problems. The doctors had done enough, but the fact I was still indulging in my baser behaviors made me a continuously poorer and poorer marriage option. Thank the Saints my father forgot about the Ravkan contract, because when I showed it to him, he thought it was something new. He had me leaving for Dover the next morning."

"From which you took the channel train, another four trains and finally a sand skiff to get here." Nikolai smiled that crooked smile of his, and Cecily almost wept at the love in his eyes. She wiped at her eyes with her palms and sniffled. "I see you've not run for the hills."

"Not planning on it, lovely. Unless Priyvet needs me,"

He earned a hard whack on his arm for that insolence, and Cecily burst into joyous, if somewhat gentle, giggles. She opened her hands again and light this time burst forth in a bright glow that rivaled the fireplace's heat and warmth.

"Ah, there she is." Nikolai grinned, and kissed her cheek. He nestled close to her and laid his chin on her shoulder as they watched the light in her palm grow and shrink. His hand over it changed the flame's colors to a mesmerizing teal. However, unlike Vasily, it didn't burn Nikolai's palms. He gave a yelp of childish joy when she and him ended up attempting to play catch with the highly violitle projectiles, and she wound up breaking a mirror and a few pieces of Shu han pottery.

What that night, long after its finishing, brought Cecily was indescribable. She'd almost lost her husband that night, but in being truly herself, they'd found one another. Truly found one another. The lesser matter of her Sun Summoning was relied to the Darkling the following morning, when the light in Cecily's hands finally dimmed with Nikolai's departure to the Ravkan War council.

Finis.

Oooh I’d love an arranged marriage au where the reader hasn’t been married by any other foreign princes (she’s a princess on her grand tour) and she comes to ravka jaded and bitter. (This can be set during the original trilogy in a version where the sun summoner has never come back). She meets Nikolai at a ball during siege and storm and the two of them go from enemies to lovers…. 👀. Along the way it could turn out that she’s the sun summoner but because of her severely internalized trauma, she *cant* show her powers.

Ooooooh Pookie

^^ sorry but this man is so Nikolai coded it’s insane . No offense Patrick Gibson but these blond men are starting to get to me

This one’s gonna be short but I want to get to the point, sorry. Your backstory was good just pretend mine fits. LOL

Warnings: none just fluff

Months on tour. Months. That’s how long you’ve been gallivanting around the continent in search of a future King consort. The only option, it seems, to your chagrin, is the wild, witty, and annoyingly gorgeous Prince Nikolai.

“Come running back?” He asks nonchalantly one evening after he casually burst into your chambers like he owns the place. Your eye twitches from where youre sitting at your vanity, the blond collapsing dramatically on top of your bed. “Miss me too much? I missed you, too.”

“Please keep your shoes off the bed.” You snap, applying moisturizer with violence as he toes off one shoe, then the other, and props his chin on his hands, kicking his feet in the air like a child. “Don’t you have anyone else to bother?���

“Sure, but you’re the most fun.”

“Saints, save me.”

“No Saints here, love. Just me.”

When you turn and throw a makeup brush at his head he dodges, grinning like a fiend as you roll your eyes.

You’ve known Nikolai for years. Since you were children he taunted and teased you, pulling on your pigtails and stealing the last bites of your desserts. Now though, he seems different. Sure he’s still annoying but, after forcing yourself to deal with him courting you, you noticed the changes.

Instead of pulling on your hair, he holds your hands when helping you out of carriages, off horses, and up or down any flights of stairs. He keeps a hand on the small of your back when you move through crowds, his witty remarks kept low so only you can hear them. Instead of stealing your desserts he saves you the last bite, casually sliding his plate an inch or so towards you without even glancing over.

He plays with your hair during meals or boring meetings, wrapping a strand around his finger and tugging twice, gently, as if a signal that he’s thinking of you, that he’s by your side, that he takes this tour seriously.

“Can we end the theatrics and admit you like me?” He asks from the bed, stretching out like a lazy housecat as he watches you finish up your skincare and stand. His serene smile grows as you approach, planting your hands on the bed to peer down over him.

“I do not like you.” You say sweetly, then gasp when he hooks an arm around your waist and tugs you down next to him, practically nose to nose.

“Stop lying.” He groans, amused when you wiggle and squirm (you’re barely trying to escape) before you finally let out a huff and collapse, head propped on his bicep when he tugs you closer. His blue eyes are glittering with something like adoration when he pokes your cheek, marveling at the smoothness. “You look like a snail ran all over your face.”

“How sweet of you.” You scoff, poking his cheek in return. “Your skin is dry. Who’s taking care of you?”

“Hopefully you.” At your raised brow he grins again, rolling you on top of him so he’s lying beneath you, gazing up. Shockingly enough, though his grip has loosened, you don’t move away. “Come on, Y/N. We both know you’ll be happy with me. I make you laugh.”

“You give me stomach pains.”

“That’s love.”

“It might be a tape worm.”

“Y/N.” He sighs and pulls you closer, one hand reaching up to cup your cheek. “This is no way to treat your future King.”

“Consort. King Consort.”

“So you agree.”

“Nik—”

“Hmm?” He lifts his head a fraction of an inch, touching the tip of his nose to yours. When your breath hitches, he smiles. “There she is..” he murmurs, satisfied, and pulls your mouth down to his.

You melt into the kiss.

He’s mine mine MINE

#nikolai lantsov#shadow and bone#nikolai x reader#nikolai lantsov fanfic#fluff#shadow and bone imagine#nikolai lantsov x reader#Wyn writes#fanfic#ao3 fanfic#ao3 writer#richard III#autism history#autism headcanon

85 notes

·

View notes

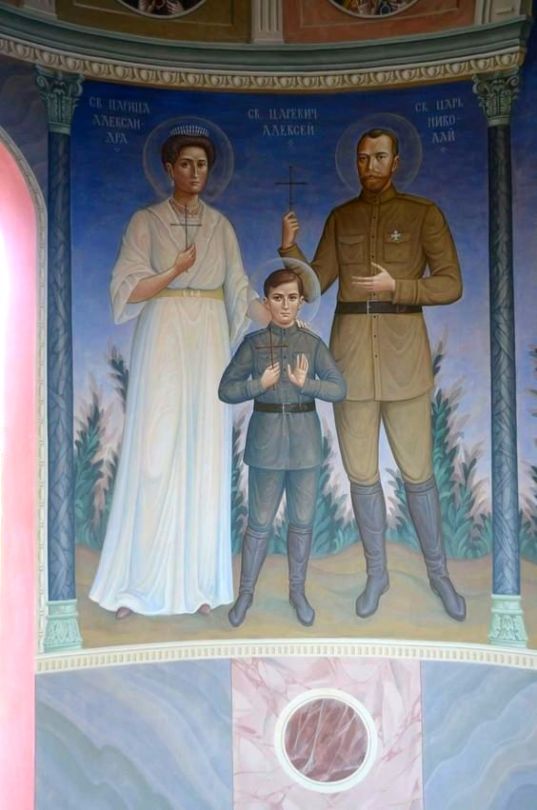

Photo

The Romanov martyrs (including doctor Botkin and nun Varvara) as depicted in one of the Orthodox churches

#Russia#Romanov#Nicholas II.#Alexandra Fyodorovna#Olga Nikolaevna#Tatiana Nikolaevna#Maria Nikolaevna#Anastasia Nikolaevna#Alexei Nikolaevich#Elizaveta Fyodorovna#Varvara Yakovleva#Eugene Botkin#icons

150 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Yurovsky, in 1922, wrote “after checking again to see that all were dead, I ordered the men to start moving them.” The entire executions had taken fewer than ten minutes.

His finger caught the trigger, and, with a flash of smoke and a deafening noise, the first bullet smashed into Nicholas’s chest. “He reeled suddenly,” remembered Andrei Strekotin. In an instant his khaki tunic exploded in blood, as “all ten people firing” took direct aim at their former emperor. “I shot Nicholas,” Yurovsky later wrote, “and everyone else also shot him.” Kudrin, who opened fire the same instant as Yurovsky, squeezed off five rounds in rapid succession, each ripping into Nicholas, who, Strekotin remembered, “stood quivering as shot after shot pierced his body.” Three of these wounds, to the left side of his chest, were, in and of themselves, fatal, tearing through Nicholas’s rib cage, into the pericardial cavity, into his heart, and exiting out his back. With “wide, vacant eyes,” Alexei Kabanov recalled, “Nicholas lurched forward and toppled to the floor.”

***********

With the first shot, Trupp turned from the execution squad toward the northeastern corner of the room; two bullets, fired in rapid sucession, struck his left thigh, shattering his femur and breaking his leg. Unable to stand, Trupp crumpled to his knees; seeing him beneath the thick layer of smoke, one of the executioners in the first row took aim, firing a bullet into the right side of his head. Smashing through his skull, it killed him instantly.

***********

Kharitonov, standing against the northern wall, was hit with several bullets at once, the force so powerful, Yurovsky recalled, that he “sat down and died.”

***********

Drunk and consumed with his own lust for blood, Ermakoy turned from Nicholas to Alexandra, who, he recalled, stood “only six feet away.” He raised his Mauser as she turned her head away and began to cross herself; but before she could finish, as Andrei Strekotin recalled, he pulled the trigger. A bullet slammed into the left side of her skull, a spray of blood and brain tissue exploding from her right ear as the force drove her violently back, knocking her onto the floor.

***********

When Yurovsky entered the room, he saw Botkin, covered in blood, leaning on his right arm as he tried to raise himself from the floor. He stepped across the pile of blood spreading from the emperor’s body, held his Mauser close to Botkin’s head, and pulled the trigger. The bullet ripped through the doctor’s head, exiting out the lower right side of his skull, its force slamming his body against the floor in a shower of gore.

***********

Yurovsky fired the last bullets from his Mauser directly into the tsesarevich, who slowly slipped from his chair and crumpled to the floor. Paul Medvedev, who had staggered back into the room, saw Alexei on the floor, “moaning and alive.” Out of bullets, Yurovsky yelled to Ermakov, who turned back to the center of the room, pulling and eight-inch triangular bayonet from his belt as he stumbled over the growing pile of arms and legs. Crouched on the floor, he raised the knife; over and over, the glint of steel flashed in the dim electric light as he stabbed the supine boy, blood flying from the blade with each arc and seeping across the once-yellow floorboards. Yurovsky watched in horror as Alexei struggled against the powerful, wild Ermakov: “nothing seemed to work,” Yurovsky wrote. “Though injured, he continued to live.” None of the assassins knew that, beneath his tunic, the tsesarevich wore a shirt wrapped with jewels, which shielded his torso from both bullets and Ermakov’s bayonet. Finally, “unable to stand by,” Yurovsky pulled his second gun, a colt, from his belt, pushed Ermakov aside, and first two shots into the boy.

***********

Yurovsky, standing behind Tatiana, aimed his Colt and fired. The bullet tore into the rear of her head; it ripped through her skull instantly, blowing out the right side of her face in “a shower of blood and brains” that covered her screaming sister.

***********

In an instant, Ermakov, “wild-eyed and face splattered with blood,” moved forward. As Olga tried to rise, he violently kicked her back, sending her spinning toward the floor; at the same time he squeezed the trigger of his Nagant revolver. With a flash of smoke, the bullet caught her as she fell, just beneath her chin, breaking her jaw as it seared through her skull, lacerating her brain before smashing through the top of her forehead. In a second, she toppled across her sister, dead.

***********

Hearing their terrified screams, Ermakov turned from the lifeless body of their eldest sister, rounding on them with his blood-stained bayonet. Kabanov watched as he grabbed Marie, “stabbing her in the chest over and over again.” Yurovsky looked on in horror as Ermakov attacked her, but “the bayonet would not pierce her bodice.” She was, Yurovsky wrote, “finished off” with a shot to the head.

***********

Anastasia had backed into the corner next to the storeroom door. Ermakov turned on her, slashing frenziedly “through the air” as he approached. Drunk and crazed, he struck the pier, his bayonet slicing deeply into the plaster, before drawing back the blade and plunging it into Anastasia’s chest as she struggled to fend him off. In an increasing spiral of savagery, he swung his knife repeatedly, unable to penetrate her bodice. “Screaming and fighting,” Yurovsky wrote, she fell only after Ermakov put his gun to her head and pulled the trigger.

***********

Yurovsky and Ermakov had reached the open door to the corridor when, as Kudrin recalled, “something white moved in the corner.” It was Anna Demidova, who had fallen in a faint after being shot in the leg. ‘Thank God!“ she screamed. "God has saved me!” She tried to get to her feet, but Ermakov, bayonet held high, reached her, swinging out in delirium. “She grabbed it with her hands,” Kabanov remembered, “screaming and crying.” With her hands sliced to ribbons and unable to defend herself, finally she, too, fell still.

The Fate of the Romanovs - Greg King and Penny Wilson

#nicholas ii#alexandra feodorovna#Anastasia nikolaevna#olga nikolaevna#tatiana nikolaevna#maria nikolaevna#alexei nikolaevich#TW: gore#tw: blood#tw: death#tw: violence#alexei trupp#eugene botkin#anna demidova#ivan kharitonov#long live the queue

77 notes

·

View notes

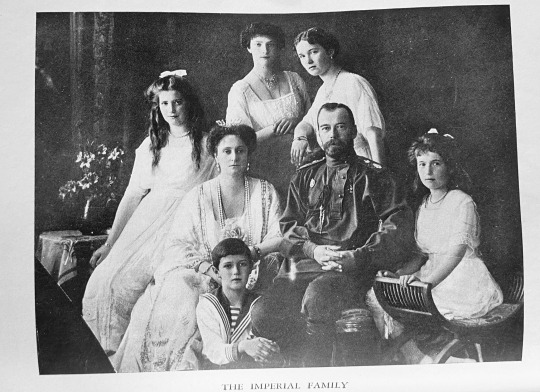

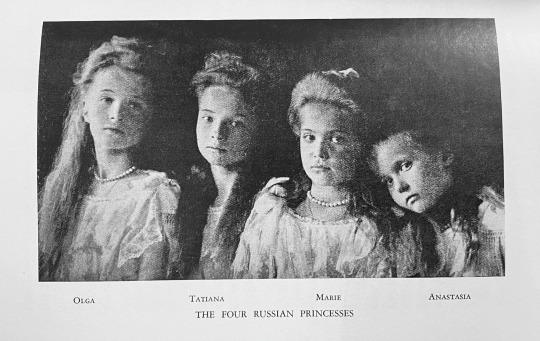

Text

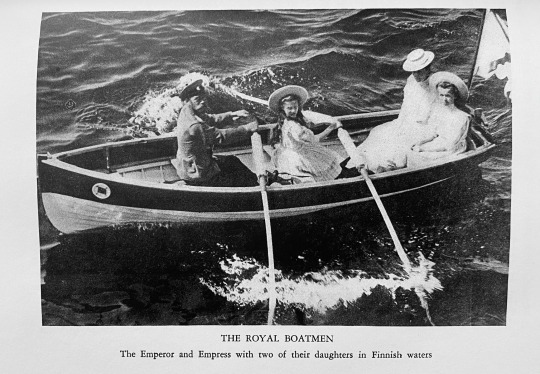

Tsar Nicholas II of Russia and his family as featured in Gleb Botkin’s The Real Romanovs (1931).

Gleb Botkin was the son of Dr. Eugene Botkin, who was the court physician for Nicholas and his family from 1908 to 1918. Dr. Botkin was close with both the Tsar and the Tsarina, and traveled with them to Yekaterinburg, where they were all executed on July 17, 1918. Gleb and his sister grew up alongside the imperial children, often playing together during the holidays. After the revolution, the two siblings fled to Siberia and Japan before settling in the United States in 1922. Gleb became acquainted with Anna Anderson, the most notorious of the Romanov impostors, in Germany in 1927. He recognized her as the Grand Duchess Anastasia, and became a fervent supporter of her claim for the rest of his life. He authored many novels and articles, including The Real Romanovs, and corresponded with the remaining Romanovs about “Anastasia.” Gleb, along with Princess Xenia Georgievna, paid for Anna to travel to France and the United States in 1928. Later that year, Nicholas II’s mother, the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, died in her native Denmark. At her funeral in Copenhagen, many of the most prominent members of the family gathered to sign the “Copenhagen Statement,” which was a joint rejection of Anna’s claim. She lived in a state of tumultuous, on-and-off luxury and squalor in Europe from the 1930s to the 1960s. In 1968, Gleb and his friend John Manahan funded her journey to the United States. The three lived near one another in Charlottesville, Virginia. Anna and John were wed later that year, with Gleb as the best man. Gleb died the following year, and Anna passed in 1984. After her death, the remains of the Imperial Family were tested with Anderson’s DNA, proving once and for all that Anna was not the Grand Duchess Anastasia.

(I took these pictures myself! I have a copy of the original print of this book from 1931. These photographs are widely available on the internet, but I don’t believe the third one is very common. The two Grand Duchesses pictured are Olga and Tatiana.)

#grand duchess olga nikolaevna#grand duchess tatiana#grand duchess maria nikolaevna#grand duchess anastasia#tsarevich alexei#empress alexandra feodorovna#tsar nicholas ii#history#russia#royalty#gleb botkin

75 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I'm creating a Romanov roleplay so could you give me a list of members and friends of the Romanov family, and others (Standart officers, Bolsheviks, etc.) for people to roleplay? That would be very helpful since I know I'm going to accidentally miss some characters (^^”).

Hi! These are some people who were involved with the Romanovs:

Friends:

Anna Vyrubova—quite possibly Alexandra's dearest friend. Typically viewed as a bit of a simpleton or a cunning spy--the reality is probably that she was neither. Also very attached to Rasputin.

Lili Dehn—another of Alexandra's friends, a lady-in-waiting. Also close with Nicholas and the children; was with Alexandra when Nicholas abdicated.

Elizabeth Naryshkina—the elderly mistress of the robes.

Sophie Buxhoevedon—lady-in-waiting, affectionately known as "Isa" (also spelled "Iza").

Catherine "Trina" Schneider—also attempted (unsuccessfully) to teach the Romanov sisters German. Taught Russian to Alexandra. Lutheran.

Grigori Rasputin—infamous. Especially intimate with Alexandra, also a sort of mentor for the daughters. Killed in 1916.

Kolya Demenkov—Alexei’s friend.

Gleb Botkin & Tatiana Botkina—the children of Evgeny Botkin.

Sofia Orbeliani—Alexandra’s friend and an invalid. Died in 1915.

Countess Anastasia “Nastenka” Hendrikova—family friend.

Family:

Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna—OTMA's grandmother. But a bit frosty in her relations with Alexandra.

Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna—Nicholas II's sister. Often the grand duchesses spent Saturdays with her.

Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna—Nicholas’s sister. Her family was known as the Ai Todories due to their estate. Her daughter Irina especially was close to the daughters. (Irina’s husband, Felix Yussupov, was one of Rasputin’s assassins.)

Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich—one of Nicholas’s favorite cousins, and once considered a possible groom for Olga. Under the care of Elizabeth Feodorovna. One of Rasputin’s assassins.

Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna—Alexandra’s sister. Became a nun after her husband Sergei’s assassination in 1905; sent coffee and chocolate to the family during imprisonment. Murdered by the Bolsheviks.

Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich—Nicholas’s brother. Married morganatically and exiled. Saw Nicholas before Nicholas’s departure to Tobolsk. Also murdered by the Bolsheviks.

Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich—commander in chief of the Russian army during WWI until Nicholas II took over. Not liked by Alexandra due to his dislike of Rasputin.

Tutors/Staff:

Pyotr Vasilievich Pyotrov—the Russian tutor, known as "PVP."

Pierre Gilliard—the French tutor, especially close to Alexei. Often called "Zhilik" or "Monsieur."

Sydney Gibbes—the English tutor, often known as "Sig."

Sofia Tyutcheva—Known as "Savanna," OTMA's unofficial governess when they were young. Outspokenly against Rasputin, and not popular with the Romanovs' other friends.

Margaretta Eagar—OTMA's Irish governess, dismissed in 1904.

Anna Demidova—lady-in-waiting who accompanied the family and was eventually killed with them. Known as “Nyuta.”

Aloise (Alexei) Trupp—footman who was killed with the family; unique in that he was Latvian, and Catholic.

Ivan Kharitonov—cook killed with the family.

Leonid Sednev—companion of Alexei during captivity, eventually sent away by Yakov Yurovsky.

Eugene Botkin—doctor (primarily Alexandra’s). Killed with family.

Nagorny and Demenkov—Alexei’s “sailor nannies.” Only Nagorny continued on with the family to Tobolsk.

Standart Officers of Note:

Pavel Voronov—Olga's love interest in 1913. She wrote of him as "S." in her diaries.

Alexander Konstantinovich Shvedov—Also Olga's love interest in 1913, took place before Voronov. Referred to as "AKSH" in diaries.

Viktor Zborovsky—Anastasia's crush. She also exchanged letters with his sister Ekaterina "Katya" in captivity. Nicholas's favorite tennis partner.

Patients during WWI/Nurses, Doctors:

Dmitri Shakh-Bagov—Olga's love interest. Known as "Mitya."

Dmitri Malama—Tatiana's love interest. Gave her a dog known as Ortipo, named after his cavalry horse.

Valentina Cheborateva—OT’s friend and fellow nurse.

Margarita Khitrovo—fellow nurse and friend. Known as “Ritka” or “Rita.”

Dr. Vera Gedroits—female doctor. Known as “Princess Gedroits.” After the tsar’s abdication, her behavior turned increasingly unconventional.

Vladimir Kiknadze—Tatiana’s love interest after Malama. Considered a dangerous flirt by the other nurses and doctors.

Politicians:

Sergei Witte—Served as prime minister 1905-1906.

Pyotr Stolypin—Served as prime minister 1906-1911. Sofia Tyutcheva, Nicholas II, and OT were there at his assassination.

Mikhail Rodzianko—state chairman of the Duma, 1911-1917.

Bolsheviks/Captors, etc.:

Alexander Kerensky—member of the Provisional Government. Oversaw the Romanovs’ house arrest.

Eugene Kobylinsky—commandant during house arrest; nevertheless on good terms with the family.

Vasily Yakovlev—commissar, searched the house at Tobolsk; helped transfer the family to the Ipatiev House at Ekaterinberg.

Alexander Avdeev—commandant at the Ipatiev House.

Yakov Yurovsky—commandant at the Ipatiev House after Avdeev. Orchestrated the murders.

Pyotr Ermakov—one of the executioners, his accounts of the Romanovs and their murder are highly exaggerated and untruthful. Was drunk on the night of the murders.

Ivan Skorokhodov–despite the rumors there is no reliable evidence to support the idea of a liaison with Maria. However, he was really a guard at the Ipatiev House.

#imperial russia#history#anna vyrubova#lili dehn#sophie buxhoevedon#rasputin#maria nikolaevna#romanovs

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is Tsarevich Alexei pulling? The weight of Russia, perhaps?

As a baby, the little Tsarevich was simply beautiful (the photos speak for themselves.) At fourteen, his mother's lady-in-waiting, Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden, described him as "...a pretty child, tall for his age, with regular features, splendid dark blue eyes with a spark of mischief in them, brown hair, and an upright figure".

He was adventurous and restless by nature. Doctor Eugene Botkin's children noticed Alexei's inability to "stay in any place or at any game for any length of time." He could be difficult to control. Olga could not manage his temper (he once slapped her.) The only person he obeyed was his father. As he grew up, he developed a more mature and thoughtful side.

If he would have been healthy and Russia in a less turbulent phase of its growth, It is not difficult to imagine him as a dynamic, strong-handed Tsar executing many projects at once. Maybe he would have been the one to finish bringing Russia into Europe and the 20th century.

#russian history#romanov dynasty#imperial russia#naotma#Tsarevich Alexei Nikolayevich#vintage photography

25 notes

·

View notes

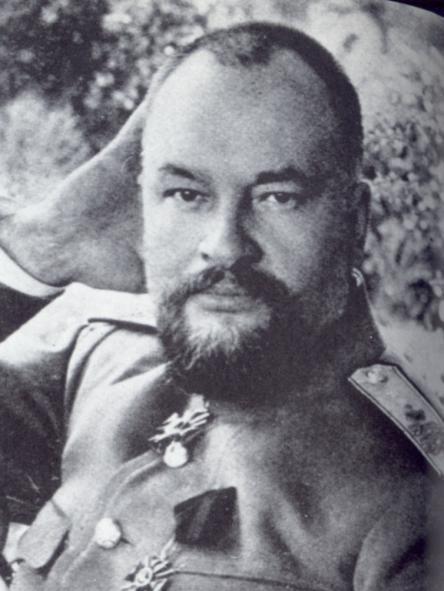

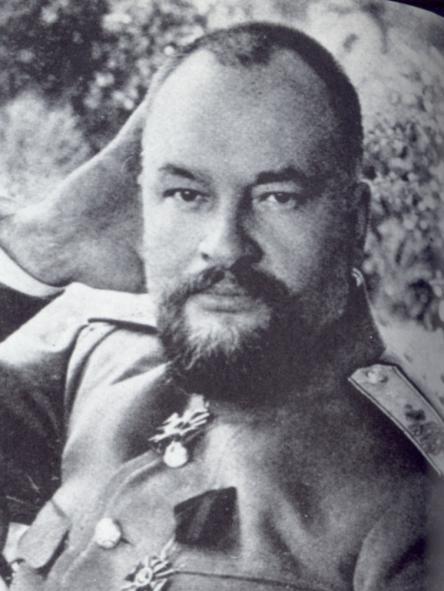

Photo

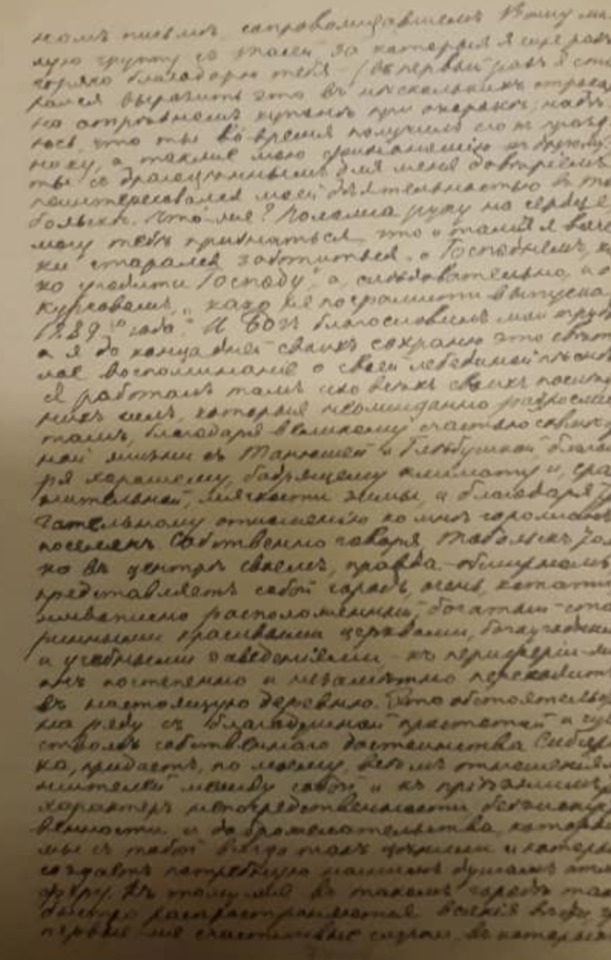

Eugene Botkin, 1916. Below is his last ever letter, written not long before he was murdered along with the Russian Imperial Family and three other servants on the 17th July 1918. Dr Botkin started this letter on 9th July 1918 but continued writing it on 17th July, when he heard the knock on his door, which was why letter ended abruptly. It was never finished or mailed. The letter was meant for his brother Alexander

“My dear, good friend Sasha, I am making the last attempt to write a real letter, - at least from here, - although this caveat is completely redundant; I do not think that it is in the cards for me to ever write from anywhere else again, - my voluntary imprisonment here is limited to my existence on this earth. In actuality, I have died – dead to my children, my friends, my work… I have died, but have not been buried yet, or rather was buried alive, - whichever you prefer: the consequences are almost identical, i.e. both one and the other have their negative and positive sides.

If I were literally dead, that is to say, anatomically dead, then according to my faith I would know what my children are doing, would be closer to them and undoubtedly more useful than now. I rest with the dead only civilly, my children may still have hope that we will see each other sometime in this life, while I, other than thinking that I can still be useful to them somehow, do not personally indulge myself with this hope, do not humour myself with illusions, but look directly into the face of unadorned reality.

Although for now, I am as healthy and fat as always, to a point where I feel disgusted every time I look in the mirror. I only console myself with the thought that if it would be easier for me to be anatomically dead, then this means that my children are better off, because when I am separated from them, it always seems to me that the worse off I am, the better off they are. And why do I feel that I would be better off dead, - I will explain this to you with small episodes, which illustrate my emotional being.

The other day, i.e. three days ago, when I was peacefully reading Saltykov-Schedrin, which I often read with pleasure, I suddenly saw the face of my son Yura in diminutive size, as if from far away, but [it was] dead, in a horizontal position, with closed eyes… The last letter from him was on 22 March o[ld] s[tyle], and since that time postal connection from the Caucasus, which even earlier faced great difficulties, probably stopped completely, as neither here nor in Tobolsk had we received anything else from Yura.

Do not think that I am hallucinating, I have had these types of visions before, but you can easily imagine, how it was for me to experience this particular thing in the current situation, which in general is quite comfortable, but to have no chance not only to go to Yura, but not even to be able to find out anything about him. Then, only yesterday, during the same reading, I suddenly heard some word, which to me sounded like ‘Papulya’, which was uttered in Tanyusha’s [his daughter Tatiana] voice, and I almost broke down in sobs.

Again, this was not a hallucination, because this word was uttered, the voice was similar, and not even for a second did I think that this was my daughter speaking, who was supposed to be in Tobolsk: her last postcard was from 23 May – 5 June, and of course these tears would have been purely egotistical, for myself, that I cannot hear and, most likely will never again hear that dear little voice and feel that affection that is so important to me, with which my little children spoiled me so. Again, the horror and sorrow which gripped me during the vision I described were purely egotistical too, since if my son had truly died, then he is happy, but if he is alive, then it is unknown what kind of trials he is going through or is fated to live through. So you see, my dear, that my spirit is cheerful, despite the torment I live through, which I bear, just described to you, and cheerful to a point where I am prepared to do this for many more years…

I am encouraged by the conviction that ‘one who bears all until the end is saved’, and the awareness that I remain loyal to the principles of the 1889 graduates. Before we graduated, while still students, but already close friends who preached and developed the same principals with which we started life, for the most part we did not view them from a religious point of view, I do not even know if too many of us were religious. But each codex of principals is a religion already, and for some it is most likely a conscious thing, while for others subconscious, - as it basically was for me, as this was the time of, not exactly uniform atheism, but of complete indifferentism, in the full sense of the word, - it came so close to Christianity that our full attitude toward it, or at least of many of us, was a completely natural transition. In general, if ‘faith is dead without work’, then ‘work’ cannot exist without faith, and if faith joins any of our work, then this is just due to special favour from God.

I turned out to be such a lucky one, through the path of heavy trials – the loss of my firstborn, the year-and-a-half-old little son Seryozha. Since that time, my codex has been widened and solidified significantly, and I took care that each task was not only about the ‘Academic’, but about the ‘Divine’. This justifies my last decision as well, when without any hesitation I left my children completely orphaned, in order to do my physician’s duty to the end, like Abraham did not hesitate to sacrifice his only son to God on His demand.

I strongly believe that the same way God saved Isaac, He will save my children too and be a father to them. But since I do not know how He will save them, and can only find out about it in the next world, my egotistic torment which I described to you, due to my human weakness, does not lose its torturous severity. But Job did bear more, and my late Misha always reminded me about him, when he was afraid that I, bereft of my dear little children, would not be able to bear it.

No, apparently I can bear it all, whatever God wills to burden me with. In your letter, for which I ardently thank you once more (the first time I tried to convey this in a few lines on a detachable coupon, hopefully you got it in time for the holiday, and also my physiognomy – for the other?), you were interested in my activities in Tobolsk, with a trust precious to me. And so? Putting hand on heart, I can confess to you that there, I tried in every way to take care of ‘the Divine, as the Lord wills’ and, consequently, ‘not to shame the graduates of year 1889′. And God blessed my efforts, and I will have until the end of my days this bright memory of my swan song.

I worked with my last strength, which suddenly grew over there thanks to the great happiness in the life [we had] together with Tanyusha and Glebushka [his son Gleb], thanks to the nice and cheerful climate and relative mildness of winter and thanks to the touching attitude towards me from the townspeople and villagers. As a matter of fact, in its center, albeit a large one, Tobolsk presents as a city that is very picturesquely located, rich with ancient churches, religious and academic institutions, [but] at the periphery it gradually and unnoticeably transitions into a real village. This circumstance, along with noble simplicity and the feeling of self-respect of Siberians, in my opinion gives the relationships among the residents and not visitors, the specific character of directness, naiveté and benevolence, which we always valued and which creates the atmosphere necessary to our souls.

In addition, various news spreads around the city very fast, the first lucky incidents for which God helped me be of use brought out such trust towards me, that the number of those wanting to get my advice grew with each day, up to my sudden and unexpected departure. Turning to me were mostly those with chronic illnesses, those who were already treated again and again, [and] sometimes, of course, those who were completely hopeless. This gave me the opportunity to make appointments for them, and my time was filled for a week or two ahead in each hour, as I was not able to visit more than six - seven, in extreme cases eight patients per day: since all these cases needed thorough review and much and much pondering.

Who was I called to besides those ill within my specialty?! To the insane, to those asking to be treated for drunkenness; [they] brought me to a prison to see a kleptomaniac, and with sincere joy I remember that the poor wretch of a lad, who was bailed out by his parents on my advice (they are peasants), behaved decently the rest of my stay… I never denied anyone, as long as the supplicants accepted that certain illnesses were completely beyond the limits of my knowledge. I only refused to go to those recently fallen ill if, of course, they needed emergency help, since, on the one hand I did not want to get in the way of regular physicians of Tobolsk, which is very lucky to have them in the capacity and most importantly, quality of relations.

They are all very knowledgeable and experienced people, excellent comrades and so responsive that the Tobolsk public is used to sending a horse or cabby to the doctor and receive him immediately. More valuable is their patience towards me, who did not have the ability to fulfill these types of requests, but on the contrary, was forced to make them wait a long time. It’s true that soon it became commonly known that I never refuse anyone and keep my word sacredly, a patient could wait for me with peace of mind.

But if their illness did not allow them to wait, then the patients went to local physicians, which always made me happy, or to Doctor Derevenko, who also possessed their vast trust, or they headed to the hospital, and this way it would happen that when I arrived at a time of prescheduled appointment, I did not find the patient there, but that was always convenient, since most of the time my schedule was so extensive that I wasn’t able to accomplish everything, at times debts formed, which I paid off when I did not find someone there.

To see [patients] at the house where I was staying was inconvenient, and anyway there was no room, nevertheless from 3 until 4 ½ - 5, I was always home for our soldiers, whom I saw in my room, the walk-through room, but since only our own [people] passed though there, it did not discomfort them. During the same hours, my town patients came to see me too, either for a refill of a prescription or to make an appointment. I was forced to make exceptions for peasants who came to see me from villages tens or even hundreds of versts away (in Siberia they don’t pay attention to distance), and who were in a hurry to get back. I had to see them in a small room before the bathroom, which was a bit out of the way, where a large chest served as an examining table.

Their trust was especially touching to me, and their confidence, which never betrayed them, that I will treat them with the same attention and affection as any other patient, not only as an equal but as a patient who has every right to my care and services, gave me joy. Those who were able to spend the night, I would visit at the inn early the next morning. They always tried to pay, but since I followed our old codex, of course I never accepted anything from them, so, while I was busy in an izba with a patient, they hurried to pay my cabby. This surprising courtesy, to which we are not used to at all in large cities, was occasionally highly pertinent, as at times I was not in a position to visit patients due to lack of funds and fast-growing cab costs.

Therefore, for our mutual benefit, I widely took advantage of another local tradition and asked those who had a horse, to send it for me. This way, the streets of Tobolsk saw me riding in wide bishop’s sleighs, as well as behind beautiful merchant trotters, but most often drowning in hay in most ordinary burlap. My friends were equally varied, which perhaps was not to everyone’s liking, but it was no concern of mine. To Tobolsk’s credit I must add that there was no direct evidence of this at all, and only one indirect, which in addition was not unquestionable.

One evening the husband of one of my female patients came to see me with a request to visit her right away, because she had strong pains (in the stomach). Luckily, I was able to fulfill his wish, albeit at a cost to another patient, for whom I did not schedule a visit, but rode with him to his house in a cab in which he came to get me. On the way he starts to grumble at the cabby, that he is not going the right way, to which the latter reasonably respon [letter ends abruptly].”

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

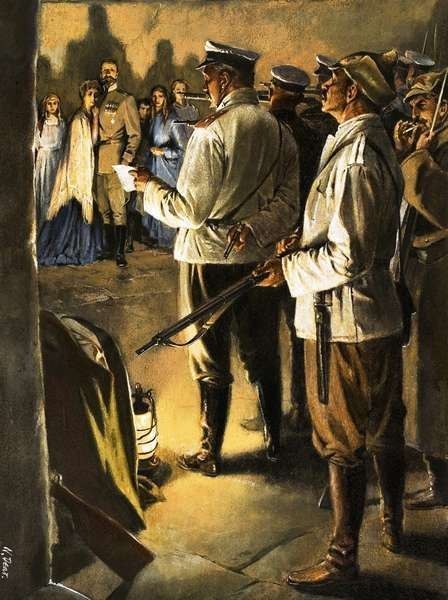

In the early hours of 17th July 1918, the entire Imperial Family along with their servants, were brutally murdered in the cellar of the Ipatiev House.

Around midnight, Yakov Yurovsky ordered the family physician, Eugene Botkin, to awaken the family and ask them to put on their clothes, under the pretext that the family would be moved to a safe location due to impending chaos in Ekaterinburg. They were led in the semi-darkness steep, narrow stairs to the ground floor. Instinctively the Romanovs followed the order of precedence instilled in them, the Tsar in front but refusing assistance as he struggled with the burden of Alexei, who winced with pain from his bandaged leg; then Alexandra leaning heavily on Olga’s arm, followed by Tatiana, Maria, and Anastasia. As they made their way to the stairs, the family paused and devoutly crossed themselves at the stuffed mother bear and her cubs that stood on the landing — a sign of respect for the dead, thinking as they did that they were going to be leaving the house.

Following the family came Dr Botkin, Alexei Trupp (Tsar’s footman), Anna Demidova (Tsarina’s maid), and Ivan Kharitonov (the family’s cook). They all exited the house, re-entering by another, adjacent door leading down into the basement. Nicholas asked if Yurovsky could bring two chairs, on which Tsarevich Alexei and Alexandra sat. Yurovsky's assistant Grigory Nikulin remarked to him that the "heir wanted to die in a chair. Very well then, let him have one."

The prisoners were told to wait in the cellar room while the truck that would transport them was being brought to the House. A few minutes later, an execution squad of secret police was brought in and Yurovsky read aloud the order given to him by the Ural Executive Committee:

“Nikolai Alexandrovich, in view of the fact that your relatives are continuing their attack on Soviet Russia, the Ural Executive Committee has decided to execute you.”

Nicholas, facing his family, turned and said "What? What?" Yurovsky quickly repeated the order and the weapons were raised.

#romanovs#history#royalty#myedits#nicholas ii#alexandra feodorovna#otma#alexei nikolaevich#tsarevich alexei#olga nikolaevna#tatiana nikolaevna#maria nikolaevna#anastasia nikolaevna#imperial russia

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

THE EXECUTION OF THE ROMANOV IMPERIAL FAMILY: Around midnight on 17 July, 1918, Yakov Yurovsky, the commandant of The House of Special (Ipatiev House) Purpose, ordered the Romanovs' physician, Dr. Eugene Botkin, to awaken the sleeping family and ask them to put on their clothes, under the pretext that the family would be moved to a safe location due to impending chaos in Yekaterinburg. The Romanovs were then ordered into a 6m × 5m (20ft × 16ft) semi-basement room. Nicholas asked if Yurovsky could bring two chairs, on which Tsarevich Alexei and Alexandra sat. Yurovsky's assistant Grigory Nikulin remarked to him that the "heir wanted to die in a chair. Very well then, let him have one." The prisoners were told to wait in the cellar room while the truck that would transport them was being brought to the House. A few minutes later, an execution squad of secret police was brought in and Yurovsky read aloud the order given to him by the Ural Executive Committee. Nicholas, facing his family, turned and said: "What, What?" Yurovsky quickly repeated the order and the weapons were raised. The Empress and the Grand Duchess Olga, according to a guard's reminiscence, had tried to bless themselves, but failed amid the shooting. Yurovsky reportedly raised his Colt gun at Nicholas's torso and fired. Nicholas fell dead, pierced with at least three bullets in his upper chest. The other executioners began to shoot chaotically until all the victims had fallen. The last to be killed were Alexei and Anna Demidova, the lady-in-waiting of Tsarina Alexandra.

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Remember these victims:

Many have heard of the Romanov execution. However, surprisingly very few known that it was not just the Romanovs were killed on the night of July 17, 1918.

These are the forgotten victims. They were royal followers and friends of the Romanov family, who willingly joined them in exile.

Ivan Kharitonov, a cook for the Romanov family.

Ivan with his wife and daughter went into exile with the Romanov family.However, his family did not go with him to Ekaterinburg.

He was canonized as a passion-bearer in the Russian Orthodox Church.

Alexei Trupp, a footman in the Romanov household

Not much is known about Trupp. Many believe he went into exile with the Romanovs willingly. For he saw the family as friends.

He was canonized a martyr in the Russian Orthodox Church, despite not practicing the faith.

Anna Demidova, a maid who served mostly for Alexandra.

It is said she was the last to die. When the soldiers pulled their guns out, she fainted. After she awoke it is said she screamed: “Thank God! God has saved me!”

At that moment the soldiers turned on her. Unlike the others Anna did not die from a bullet. Instead she was stabbed to death.

She was canonized as a martyr in the Russian Orthodox Church.

Eugene Botkin, a court physician.

Botkin was hired to help treat Alexei’s hemophilia. At the time of his death, he was divorced with four children. Two of his children died in the First World War. His wife divorced him because of his loyalty to the Romanovs.

He considered the Romanovs not just friends, but also family. When the family went into exile, he saw it as a personal duty to join them.

He was canonized as a martyr in the Russian Orthodox Church.

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Nicholas Alexandrovich,” he said to the Emperor, “your relatives are trying to save you; therefore we are compelled to shoot you!”

“What?” Nicholas asked.

“This is what!” Yurovsky said, ordering his men to open fire. As the shots rang out there were “loud cries” and screams. “Death had been instantaneous,” reported Robert Wilton, for Nicholas, Alexandra, the three oldest grand duchesses, Botkin, Kharitonov, and Trupp. Alexei, said guard Paul Medvedev, “was still alive and moaned. Yurovsky went up and fired two or three ore shots at him. The heir grew still.” Anastasia, still alive, “rolled about and screamed,” Wilton wrote, “and, when one of the murderers approached, fought desperately with him till he killed her.” She finally fell, “pierced by bayonets.” Demidova was the last to die. The soldiers grabbed rifles from the corridor, chasing her back and forth across the rear of the cellar room and repeatedly stabbing her with bayonets as she screamed in vain. All of the Romanovs, remembered Medvedev, were “on the floor, with many wounds on their bodies. The blood was running in streams.”

The Resurrection of the Romanovs - Greg King & Penny Wilson

#romanov#nicholas ii#alexandra feodorovna#anastasia nikolaevna#tatiana nikolaevna#olga nikolaevna#maria nikolaevna#alexei nikolaevich#anna demidova#alexei trupp#eugene botkin#Ivan Kharitonov#long live the queue

63 notes

·

View notes

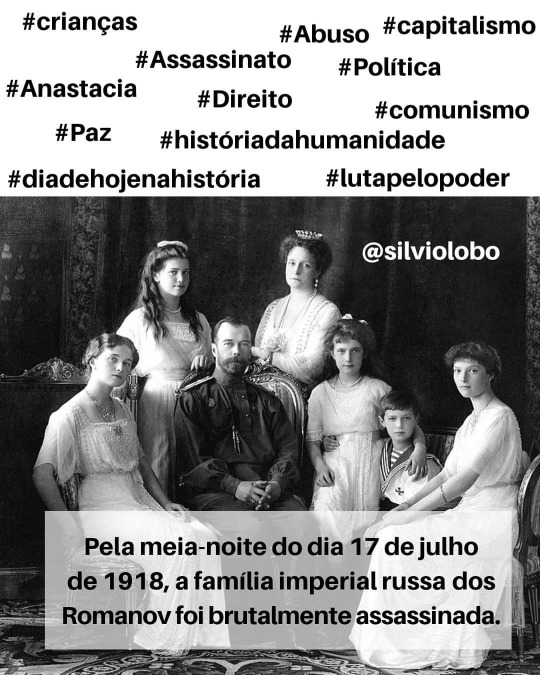

Photo

Pela meia-noite do dia 17 de julho de 1918, Yakov Yurovsky, comandante da Casa da Proposta Especial, ordenou ao médico dos Romanov, Dr. Eugene Botkin, que acordasse a família e pedisse que se vestissem, sob pretexto de que a família seria transferida para um local seguro, devido ao crescente caos em Ecaterimburgo. Os Romanov foram então levados para uma sala na cave com 6 m × 5 m (20 ft × 16 ft). Nicolau pediu a Yurovsky que trouxesse duas cadeiras, para que o czarevich Alexei e Alexandra se sentassem. Os prisioneiros foram avisados para esperar na cave, até que o camião que os transportaria chegasse. Poucos minutos depois, um esquadrão de execução da polícia secreta foi trazido e Yurovsky leu em voz alta a ordem de condenação à morte redigida pelo Comitê Executivo do Ural: “Nikolai Alexandrovich, uma vez que os seus familiares e aliados continuam o seu ataque à Rússia Soviética, o Comitê Executivo do Ural decidiu que fosse executado.” Nicolau, encarando a sua família, virou-se e disse: "O quê? O quê?" Yurovsky rapidamente repetiu a ordem e as armas foram apontadas. A imperatriz e a grã-duquesa Olga, de acordo com a lembrança de um guarda, tentaram fazer o sinal da cruz, mas foram surpreendidas pelo tiroteio. Yurovsky apontou a sua arma ao peito de Nicolau e disparou vários tiros; Nicolau caiu morto. De seguida, Yurovsky atingiu mortalmente Alexei. Os outros executores começaram a disparar repetidamente até todas as vítimas terem caído. Muitos tiros foram disparados, tendo sido abertas as portas para dispersar o fumo provocado pelos disparos. Algumas das vítimas não morreram imediatamente, levando que Pyotr Ermakov as esfaqueasse com a sua baioneta, evitando, assim, que os tiros fossem ouvidos do lado de fora. Entretanto, foram também atingidas pelas baionetas. Olga tinha um ferimento de bala na cabeça. Maria e Anastásia ter-se-iam agachado contra a parede, cobrindo as suas cabeças aterrorizadas, até serem atingidas e derubadas. Fonte: Wikipédia #romanov #diadehojenahistória #assassinato #Política #hojenahistória https://www.instagram.com/p/CCu29HfBZIH/?igshid=9kt5nsv79ssz

0 notes