#Ivan Kharitonov

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

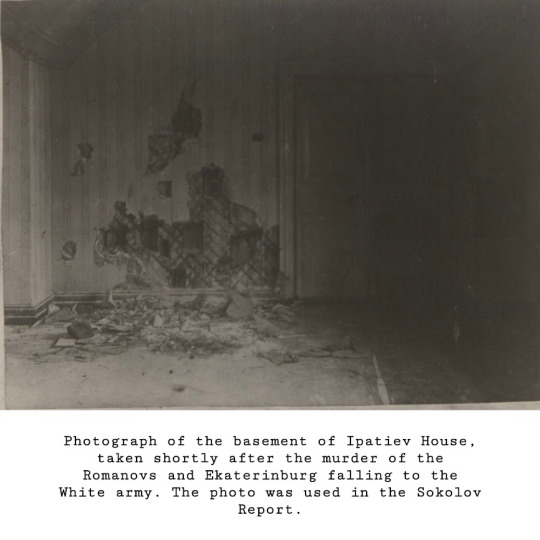

105 years ago, on the night of 16/17 July 1918, the Romanov family and their attendants were killed in Ekaterinburg.

Pierre Gilliard, the beloved tutor of the imperial children, was one of the first people to enter the Ipatiev House after the murders. As part of the Sokolov Investigation into the crime and the subsequent media frenzy, he gave these statements:

“…the stoves; they were all full of various burned articles. I recognised a considerable number of burned things such as tooth- and hair-brushes, pins and a number of small things bearing the initials: "A. F." [Alexandra Feodorovna.]”

"I then went to the lower storey, the greater part of which was a basement. I entered with intense emotion the room in which, perhaps, they had died. Its aspect was most sinister. Daylight came in through a window with iron bars across it. The walls and the floor bore marks of bullets and bayonet thrusts. It was quite obvious that a dreadful crime had been committed there, and that several people had been killed. In my despair believed that the Emperor had perished, and, that being the case, I could not believe the Empress had survived him… Yes, it was quite possible that they had both been killed. And the children? Had they also been massacred? I could not believe it. The idea was too horrible. And yet everything seemed to prove that the victims had been numerous."

Nicholas II Alexandrovich Romanov (1868-1918) Alexandra Feodorovna Romanova (1872-1918) Olga Nikolaevna Romanova (1895-1918) Tatiana Nikolaevna Romanova (1897-1918) Maria Nikolaevna Romanova (1899-1918) Anastasia Nikolaevna Romanova (1901-1918) Alexei Nikolaevich Romanov (1904-1918) Dr. Evgeny Sergeievich Botkin (1865-1918) Anna Stepanova Demidova (1878-1918) Ivan Mikhailovich Kharitonov (1872-1918) Alexei Aloise Egorovich Trupp (1856-1918) Ortipo (1914-1918) Jimmy (1915-1918)

SOURCES: The Last Days of the Romanovs, Telberg, Wilton, Sokolov. The Crime of Ekaterinburg, Illustrated London News

#olga nikolaevna#tatiana nikolaevna#maria nikolaevna#anastasia nikolaevna#alexei nikolaevich#Tsar Nicholas II#Alexandra Feodorovna#Alexei Trupp#Aloise Trupp#Anna Demidova#Dr. Botkin#Evgeny Botkin#Ivan Kharitonov#Jimmy#Ortipo#OTMA#NAOTMAA#Romanov family#Russian history#imperial russia#Ipatiev House#Ekaterinburg#Nikolai Sokolov#Sokolov Report#sources#Pierre Gilliard#my own

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

The saddest day in my life

July 17th

On this day, 105 years ago, Wednesday July 17th 1918, Tsar Nicholas II of Russia (50), his wife Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna (46) and their children, Grand Duchesses Olga (22), Tatiana (21), Maria (19), Anastasia (17), Tsarevich Alexei (13), their four loyal friends, Alexei Trupp (62), Ivan Kharitonov (46), Anna Demidova (40), Evgenie Botkin (53) and beloved pets Ortipo (4) and Jimmy (3) were brutally murdered in shooting by Bolsheviks in Ipatiev House, Ekaterinburg.

Orthodox chuch has canonised them as Saints after the fall of communism.

We can only believe that they are praying for us. 😭💔

#saddest#17th July#17th July 1918#long live the monarchy#god save the tsar#tsar nicholas ii#tsarina alexandra#olga nikolaevna#tatiana nikolaevna#maria nikolaevna#anastasia nikolaevna#alexei nikolaevich#alexei trupp#anna demidova#ivan kharitonov#evgenie botkin#ipatiev house#house of the special purpose#house of romanov#romanov#romanovs#ortipo#jimmy

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

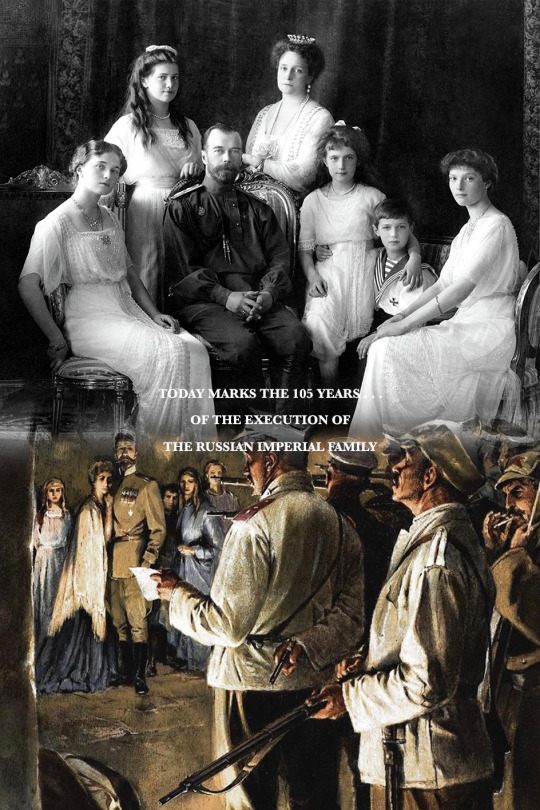

Today, July 17th 2023, marks the 105th anniversary of the execution of the last Imperial Family of Russia…

Tsar Nicholas II, Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna, Olga Nikolaevna, Tatiana Nikolaevna, Maria Nikolaevna, Anastasia Nikolaevna, Alexei Nikolaevich and the family’s 4 faithful servants, Doctor Evgeny Boykin, Anna Demidova, Ivan Kharitonov, and Alexei Trupp were brutally executed in the basement of the Ipatiev House or “The House of Special Purpose” as it was know to Yakov Yurovsky and other Bolsheviks who killed the family. This photo is what was left of their execution, taken by the White Czechs.

#tsar nicholas ii#alexandra feodorovna#olga nikolaevna#tatiana nikolaevna#maria nikolaevna#anastasia nikolaevna#otma#alexei nikolaevich#romanov#romanovs#otmaa#naotmaa#ipatiev house#yekaterinburg#Evgeny botkin#doctor botkin#Anna demidova#Ivan kharitonov#Alexei trupp#the house of special purpose#Yakov yurovsky#captivity#july 17#July 17th 1918

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the photograph: kitchen staff on the Imperial yacht Shtandart; 2nd from the right in a white jacket - Ivan Mikhailovich Kharitonov; 3rd from the right in a white jacket - Pierre Cubat (1844-1922).

Staff of the Imperial Kitchen:

In 1881, according to the Court Office list of the staff, there were 7 head waiters in the imperial kitchen, who received 715 rubles each per year, 24 cooks - 144 rubles per year, and 116 kitchen workers - 116 rubles per year. In total 147 people.

At the beginning of the reign of Nicholas II, according to the new staffing table, the number of kitchen workers was reduced to 143 people.

The job hierarchy of the kitchen was as follows:

Head waiters of the Main Kitchen - 4 people

Head waiters of the Common Kitchen - 2 people

10 cooks, they were called “kokhs” in court terminology. These chefs cooked for the entire court staff.

Baking masters - 6 people (the baking specialists).

Bratmeisters - 4 people (the specialists in preparing roasts).

In addition to them, there were other specialists:

table makers - 6 people

bakers - 4 people

baking apprentices - 2 people

junior cooks - 22 people

bread makers - 4 people

There were 35 apprentices of senior chefs and 12 apprentices of junior chefs.

Extra workers - 9 people, and the kitchen staff was constantly “reinforced” by sent workers - 12 people.

#romanovs#research#investigation#nicolas ii#seraphima bogomolova#photographs#imperial kitchen#Ivan Mikhailovich Kharitonov#cooks#imperial kitchen staff

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Execution of the Romanov Family

On this day, 105 years ago, the former Emperor of Russia, Nicholas II with his wife Alexandra Feodorovna, their five young children and four of their entourage: court physician Eugene Botkin; lady-in-waiting Anna Demidova; footman Alexei Trupp; and head cook Ivan Kharitonov, were murdered in the cellar of the Ipatiev House.

#romanovs#history#nicholas ii#alexandra feodorovna#olga nikolaevna#tatiana nikolaevna#maria nikolaevna#anastasia nikolaevna#alexei nikolaevich#myedits

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

Romanov Reads; a book review series

Episode 1: “The Kitchen Boy” by Robert Alexander

Pages: 204 -

Published: January 2003

Genre: Historical Fiction

The Kitchen Boy by Robert Alexander is a brilliant piece of fiction that revolves around the last kitchen boy to the Romanov Family, Leonid Sednev (pronounced Sednyov), and his story of living and working at the Ipatiev House aka “The House of Special Purpose”.

As a preface, this book was written in 2003 which is a key factor you need to know before reading this book. At the time this book was written only one of the two Romanov gravesites had been discovered and this is the grave containing the Imperial Couple (Nicholas and Alexandra), 3 of their daughters (Olga, Tatiana, and Anastasia), and their 4 servants (Botkin, Kharitonov, Trupp, and Demidova). This gravesite was discovered by amateur archaeologists in 1991 and was concealed until after the fall of the Soviet Union before it was shown to the public. Deep analysis and reconstruction of the full skeleton sets were done which concluded who was in these graves and who was not. Skeletal reconstruction shows that only 3 daughters were accounted for and there were no bones belonging to an almost 14 year old boy or a 4th daughter. The remains of the 4th daughter (Maria) and son (Alexei) were found 4 years after this book was published, in 2007, so this book explores what could’ve happened to the missing two bodies. This explains everything that happened in the last third of the book and is significant because it helps you understand the author’s creative purposes. Now knowing and understanding this crucial information, we can now provide a description of the accuracies and inaccuracies of this book.

This book is historical fiction. This is important because it is not the real Lyonka talking but is a reconstruction. This reconstruction is a beautifully and is surprisingly very historically accurate. All of the big details were covered and the author beautifully portrayed the real emotions of the family during their last weeks and even for their lives before that. Besides little specific things about Lyonka’s part in their story and very little factual differences like how the Ipatiev house was torn down in the 1960s vs the 1990s, this book was deeply accurate to its core when focusing on true facts alone.

Obviously the storyline of this book is far different and inaccurate to what happened in real life because of stylistic choices and when it was written. If you are looking for a direct source on what happened on July 17th 1918, this is not the book for that. If you are looking for a creative interpretation on the last weeks and last moments and legacy of the Romanov family then this is for you. Also at the end of the book there is an amazing plot twist that completely matches up with the time it was written when the two sets of remains of Maria and Alexei were not found and made me gasp with excitement. A true marvel for its time, this book is.

~~~~~~~~

This book was also filled with accurate information on Lyonka Sednyov, the last kitchen boy to the Romanov Family. Here is some more detailed information about him:

Leonid Ivanovich Sednyov (1903-1942) worked as a kitchen boy to the last imperial family of Russia and traveled with the family during their captivity from Tsarskoe Selo to the depths of Siberia. His uncle (Ivan Sednyov) worked alongside imperial cook Kharitonov and that is what helped Leonka eventually to become a close confidant of the imperial family. A similar age to the former Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich, he often acted as a playmate and close friend to him. A few hours before the imperial family would be killed, in the evening of the 16th of July Lyonka was told he had to leave the Ipatiev House and was contained at the Popov House next door and was told his uncle was going to bring him back home which was false information because Ivan Sednyov, along with faithful Dyadka (sailor nanny) to Alexei, Klimenty Nagorny, were killed shortly after the family’s arrival at Yekaterinburg which the imperial family including Lyonka did not know about. He later went to live with other relatives in Kaluga and during WWII he died by execution for an unspecified crime.

Here is the diary entry of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna on July 16th 1918, shortly after Lyonka was sent to the Popov house:

“…Suddenly they sent for Lyonka Sednev, for him to go and visit his uncle, and he quickly ran away, we are guessing whether it is true, and whether we will ever see the boy again …”

~~~~

I hope you guys choose to read this book because it is an amazing interpretation of a true story!

#book reviews#Romanov books#romanov#romanovs#Leonid sednev#Lyonka sednev#lenka sednev#the kitchen boy#Robert Alexander#russian imperial family#russian history#captivity#house arrest#1917#1918#july 17#July 17th 1918

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I'm creating a Romanov roleplay so could you give me a list of members and friends of the Romanov family, and others (Standart officers, Bolsheviks, etc.) for people to roleplay? That would be very helpful since I know I'm going to accidentally miss some characters (^^”).

Hi! These are some people who were involved with the Romanovs:

Friends:

Anna Vyrubova—quite possibly Alexandra's dearest friend. Typically viewed as a bit of a simpleton or a cunning spy--the reality is probably that she was neither. Also very attached to Rasputin.

Lili Dehn—another of Alexandra's friends, a lady-in-waiting. Also close with Nicholas and the children; was with Alexandra when Nicholas abdicated.

Elizabeth Naryshkina—the elderly mistress of the robes.

Sophie Buxhoevedon—lady-in-waiting, affectionately known as "Isa" (also spelled "Iza").

Catherine "Trina" Schneider—also attempted (unsuccessfully) to teach the Romanov sisters German. Taught Russian to Alexandra. Lutheran.

Grigori Rasputin—infamous. Especially intimate with Alexandra, also a sort of mentor for the daughters. Killed in 1916.

Kolya Demenkov—Alexei’s friend.

Gleb Botkin & Tatiana Botkina—the children of Evgeny Botkin.

Sofia Orbeliani—Alexandra’s friend and an invalid. Died in 1915.

Countess Anastasia “Nastenka” Hendrikova—family friend.

Family:

Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna—OTMA's grandmother. But a bit frosty in her relations with Alexandra.

Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna—Nicholas II's sister. Often the grand duchesses spent Saturdays with her.

Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna—Nicholas’s sister. Her family was known as the Ai Todories due to their estate. Her daughter Irina especially was close to the daughters. (Irina’s husband, Felix Yussupov, was one of Rasputin’s assassins.)

Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich—one of Nicholas’s favorite cousins, and once considered a possible groom for Olga. Under the care of Elizabeth Feodorovna. One of Rasputin’s assassins.

Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna—Alexandra’s sister. Became a nun after her husband Sergei’s assassination in 1905; sent coffee and chocolate to the family during imprisonment. Murdered by the Bolsheviks.

Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich—Nicholas’s brother. Married morganatically and exiled. Saw Nicholas before Nicholas’s departure to Tobolsk. Also murdered by the Bolsheviks.

Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich—commander in chief of the Russian army during WWI until Nicholas II took over. Not liked by Alexandra due to his dislike of Rasputin.

Tutors/Staff:

Pyotr Vasilievich Pyotrov—the Russian tutor, known as "PVP."

Pierre Gilliard—the French tutor, especially close to Alexei. Often called "Zhilik" or "Monsieur."

Sydney Gibbes—the English tutor, often known as "Sig."

Sofia Tyutcheva—Known as "Savanna," OTMA's unofficial governess when they were young. Outspokenly against Rasputin, and not popular with the Romanovs' other friends.

Margaretta Eagar—OTMA's Irish governess, dismissed in 1904.

Anna Demidova—lady-in-waiting who accompanied the family and was eventually killed with them. Known as “Nyuta.”

Aloise (Alexei) Trupp—footman who was killed with the family; unique in that he was Latvian, and Catholic.

Ivan Kharitonov—cook killed with the family.

Leonid Sednev—companion of Alexei during captivity, eventually sent away by Yakov Yurovsky.

Eugene Botkin—doctor (primarily Alexandra’s). Killed with family.

Nagorny and Demenkov—Alexei’s “sailor nannies.” Only Nagorny continued on with the family to Tobolsk.

Standart Officers of Note:

Pavel Voronov—Olga's love interest in 1913. She wrote of him as "S." in her diaries.

Alexander Konstantinovich Shvedov—Also Olga's love interest in 1913, took place before Voronov. Referred to as "AKSH" in diaries.

Viktor Zborovsky—Anastasia's crush. She also exchanged letters with his sister Ekaterina "Katya" in captivity. Nicholas's favorite tennis partner.

Patients during WWI/Nurses, Doctors:

Dmitri Shakh-Bagov—Olga's love interest. Known as "Mitya."

Dmitri Malama—Tatiana's love interest. Gave her a dog known as Ortipo, named after his cavalry horse.

Valentina Cheborateva—OT’s friend and fellow nurse.

Margarita Khitrovo—fellow nurse and friend. Known as “Ritka” or “Rita.”

Dr. Vera Gedroits—female doctor. Known as “Princess Gedroits.” After the tsar’s abdication, her behavior turned increasingly unconventional.

Vladimir Kiknadze—Tatiana’s love interest after Malama. Considered a dangerous flirt by the other nurses and doctors.

Politicians:

Sergei Witte—Served as prime minister 1905-1906.

Pyotr Stolypin—Served as prime minister 1906-1911. Sofia Tyutcheva, Nicholas II, and OT were there at his assassination.

Mikhail Rodzianko—state chairman of the Duma, 1911-1917.

Bolsheviks/Captors, etc.:

Alexander Kerensky—member of the Provisional Government. Oversaw the Romanovs’ house arrest.

Eugene Kobylinsky—commandant during house arrest; nevertheless on good terms with the family.

Vasily Yakovlev—commissar, searched the house at Tobolsk; helped transfer the family to the Ipatiev House at Ekaterinberg.

Alexander Avdeev—commandant at the Ipatiev House.

Yakov Yurovsky—commandant at the Ipatiev House after Avdeev. Orchestrated the murders.

Pyotr Ermakov—one of the executioners, his accounts of the Romanovs and their murder are highly exaggerated and untruthful. Was drunk on the night of the murders.

Ivan Skorokhodov–despite the rumors there is no reliable evidence to support the idea of a liaison with Maria. However, he was really a guard at the Ipatiev House.

#imperial russia#history#anna vyrubova#lili dehn#sophie buxhoevedon#rasputin#maria nikolaevna#romanovs

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

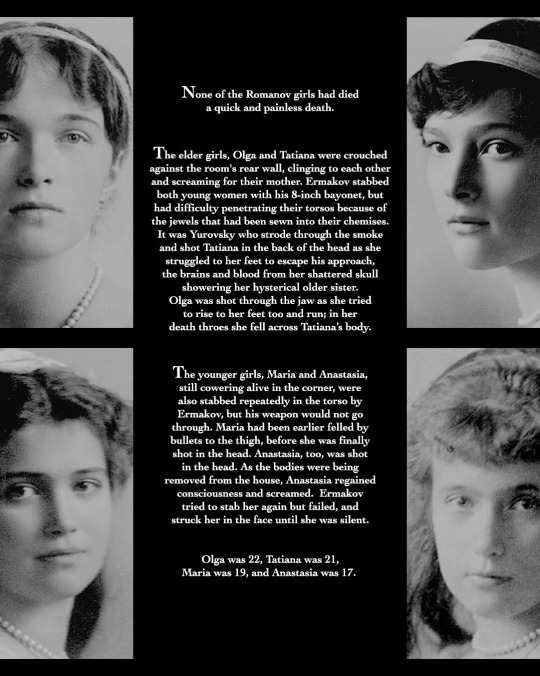

Yurovsky, in 1922, wrote “after checking again to see that all were dead, I ordered the men to start moving them.” The entire executions had taken fewer than ten minutes.

His finger caught the trigger, and, with a flash of smoke and a deafening noise, the first bullet smashed into Nicholas’s chest. “He reeled suddenly,” remembered Andrei Strekotin. In an instant his khaki tunic exploded in blood, as “all ten people firing” took direct aim at their former emperor. “I shot Nicholas,” Yurovsky later wrote, “and everyone else also shot him.” Kudrin, who opened fire the same instant as Yurovsky, squeezed off five rounds in rapid succession, each ripping into Nicholas, who, Strekotin remembered, “stood quivering as shot after shot pierced his body.” Three of these wounds, to the left side of his chest, were, in and of themselves, fatal, tearing through Nicholas’s rib cage, into the pericardial cavity, into his heart, and exiting out his back. With “wide, vacant eyes,” Alexei Kabanov recalled, “Nicholas lurched forward and toppled to the floor.”

***********

With the first shot, Trupp turned from the execution squad toward the northeastern corner of the room; two bullets, fired in rapid sucession, struck his left thigh, shattering his femur and breaking his leg. Unable to stand, Trupp crumpled to his knees; seeing him beneath the thick layer of smoke, one of the executioners in the first row took aim, firing a bullet into the right side of his head. Smashing through his skull, it killed him instantly.

***********

Kharitonov, standing against the northern wall, was hit with several bullets at once, the force so powerful, Yurovsky recalled, that he “sat down and died.”

***********

Drunk and consumed with his own lust for blood, Ermakoy turned from Nicholas to Alexandra, who, he recalled, stood “only six feet away.” He raised his Mauser as she turned her head away and began to cross herself; but before she could finish, as Andrei Strekotin recalled, he pulled the trigger. A bullet slammed into the left side of her skull, a spray of blood and brain tissue exploding from her right ear as the force drove her violently back, knocking her onto the floor.

***********

When Yurovsky entered the room, he saw Botkin, covered in blood, leaning on his right arm as he tried to raise himself from the floor. He stepped across the pile of blood spreading from the emperor’s body, held his Mauser close to Botkin’s head, and pulled the trigger. The bullet ripped through the doctor’s head, exiting out the lower right side of his skull, its force slamming his body against the floor in a shower of gore.

***********

Yurovsky fired the last bullets from his Mauser directly into the tsesarevich, who slowly slipped from his chair and crumpled to the floor. Paul Medvedev, who had staggered back into the room, saw Alexei on the floor, “moaning and alive.” Out of bullets, Yurovsky yelled to Ermakov, who turned back to the center of the room, pulling and eight-inch triangular bayonet from his belt as he stumbled over the growing pile of arms and legs. Crouched on the floor, he raised the knife; over and over, the glint of steel flashed in the dim electric light as he stabbed the supine boy, blood flying from the blade with each arc and seeping across the once-yellow floorboards. Yurovsky watched in horror as Alexei struggled against the powerful, wild Ermakov: “nothing seemed to work,” Yurovsky wrote. “Though injured, he continued to live.” None of the assassins knew that, beneath his tunic, the tsesarevich wore a shirt wrapped with jewels, which shielded his torso from both bullets and Ermakov’s bayonet. Finally, “unable to stand by,” Yurovsky pulled his second gun, a colt, from his belt, pushed Ermakov aside, and first two shots into the boy.

***********

Yurovsky, standing behind Tatiana, aimed his Colt and fired. The bullet tore into the rear of her head; it ripped through her skull instantly, blowing out the right side of her face in “a shower of blood and brains” that covered her screaming sister.

***********

In an instant, Ermakov, “wild-eyed and face splattered with blood,” moved forward. As Olga tried to rise, he violently kicked her back, sending her spinning toward the floor; at the same time he squeezed the trigger of his Nagant revolver. With a flash of smoke, the bullet caught her as she fell, just beneath her chin, breaking her jaw as it seared through her skull, lacerating her brain before smashing through the top of her forehead. In a second, she toppled across her sister, dead.

***********

Hearing their terrified screams, Ermakov turned from the lifeless body of their eldest sister, rounding on them with his blood-stained bayonet. Kabanov watched as he grabbed Marie, “stabbing her in the chest over and over again.” Yurovsky looked on in horror as Ermakov attacked her, but “the bayonet would not pierce her bodice.” She was, Yurovsky wrote, “finished off” with a shot to the head.

***********

Anastasia had backed into the corner next to the storeroom door. Ermakov turned on her, slashing frenziedly “through the air” as he approached. Drunk and crazed, he struck the pier, his bayonet slicing deeply into the plaster, before drawing back the blade and plunging it into Anastasia’s chest as she struggled to fend him off. In an increasing spiral of savagery, he swung his knife repeatedly, unable to penetrate her bodice. “Screaming and fighting,” Yurovsky wrote, she fell only after Ermakov put his gun to her head and pulled the trigger.

***********

Yurovsky and Ermakov had reached the open door to the corridor when, as Kudrin recalled, “something white moved in the corner.” It was Anna Demidova, who had fallen in a faint after being shot in the leg. ‘Thank God!“ she screamed. "God has saved me!” She tried to get to her feet, but Ermakov, bayonet held high, reached her, swinging out in delirium. “She grabbed it with her hands,” Kabanov remembered, “screaming and crying.” With her hands sliced to ribbons and unable to defend herself, finally she, too, fell still.

The Fate of the Romanovs - Greg King and Penny Wilson

#nicholas ii#alexandra feodorovna#Anastasia nikolaevna#olga nikolaevna#tatiana nikolaevna#maria nikolaevna#alexei nikolaevich#TW: gore#tw: blood#tw: death#tw: violence#alexei trupp#eugene botkin#anna demidova#ivan kharitonov#long live the queue

77 notes

·

View notes

Audio

“Vasya-Vasilyok”, a WW2 military song, performed by The Alexandrov Red Army Choir (1965) Soloists: Ivan Bukreev and Leonid Kharitonov Conductor: Boris Alexandrov

And if today it hurts don't be sad, Tomorrow will be your day! Hold your head high, Vasya-Vasilyochek! Oh, dear! Oh, Vasya-Vasilyok!

#alexandrov ensemble#red army choir#soviet union#leonid kharitonov#ivan bukreev#boris alexandrov#ww2 music#vasya-vasilyok#music#matt speaks

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

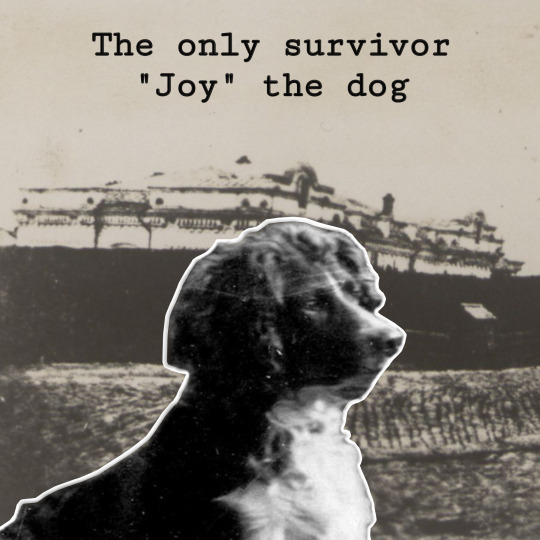

On the night of 16-17 July 1918, the Romanov family, faithful attendants, and pet dogs were murdered in a small basement in Ipatiev House, Ekaterinburg.

The Tsar, Tsarina, and their five children, Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia, and Alexei were killed alongside their attendants, chef Ivan Kharitonov, doctor Yevgeny Botkin, maid Anna Demidova, and footman Aloise ‘Alexei’ Trupp. Tatiana and Anastasia’s beloved dogs, Ortipo and Jimmy, were also killed.

Another member of the entourage who volunteered to join the Romanovs at the Ipatiev House was Alexei’s sailor nanny Klimenty Nagorny, who, after protesting against guards confiscating the thirteen-year-old boy’s chain which held religious icons, was removed from the house and executed. His arrest was observed by Alexei’s foreign tutors, who had been separated from the family. Rather than give them up, Klimenty remained quiet. Other attendants were arrested and later murdered after arriving in Yekaterinburg; Ekaterina Schneider, Anastasia Hendrikova, Ilya Tatishchev, Vasily Dolgorukov, and Ivan Sednev.

The only survivor of the murders at Ipatiev House was Alexei’s dog Joy. The dog, who was referred to in letters as being blind, was found running around the abandoned house and street days later, hungry, thirsty, and confused. Joy was rescued and taken to England.

Weeks later, the children’s languages tutors Pierre Gilliard and Sydney Gibbes entered the basement to find torn up floorboards and blood-splattered walls. The pair contributed to the Sokolov Investigation into the murders, providing and also protecting key evidence.

The Romanov family, alongside their attendants, have been canonised as Martyrs and Holy Passion Bearers in the Orthodox faith. 106 years later, we remember.

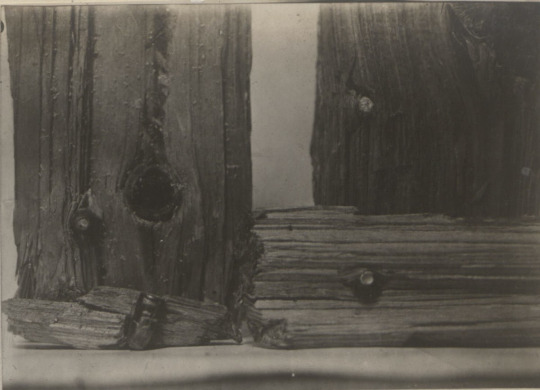

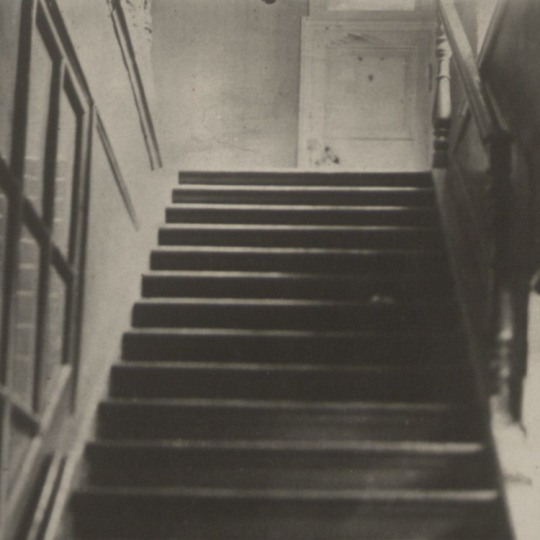

All background photographs show the interiors of the Ipatiev House taken for the Sokolov Investigation: the basement, family bedrooms, Demidova’s room, backyard door, and exterior.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

~17th July, 1918 edit~

my edit made by using capcut

#tsar nicholas ii#alexandra feodorovna#olga nikolaevna#tatiana nikolaevna#maria nikolaevna#anastasia nikolaevna#romanov edit#anna demidova#ivan kharitonov#alexei trupp#evgenie botkin#alexei nikolaevich#ipatiev house#sad edit#my edit#17th July 1918#17th of july#im crying here#😭🇷🇺💔❤️🩹

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Trans-Siberian couple! ❄️

Turnov and his dining car, who I've given the name Kharitonov (after Ivan Kharitonov, Tsar Nicholas II's head cook).

Khari is never named or appears in person in the show, but it's heavily implied that she came with Turnov in several productions. I just had fun giving her a name and face!

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the image: Ivan Mikhailovich Kharitonov (1870- not know but presumed), the Imperial maître d’hotel as of February 1917.

Who was really Ivan Mikhailovich Kharitonov?

Ivan Mikhailovich Kharitonov was born into the family of a clerk serving in the Palace Intelligent Service. Kharitonov’s father earned a noble title for his impeccable 25 years of service.

Being the son of an employee of the Palace Intelligence Service, gave him a smooth start in his career at the Imperial Court. He began his service at the age of 12 as a ‘an apprentice cook of the 2nd grade’. After having worked in the kitchen for 6 years, Kharitonov, then 18y.o., became a cook of the 2nd category.

Working in the Royal Kitchen did not allow for any deferments of the military service, and in 1891, upon reaching the age of 20, Kharitonov was called up for military service in the navy. In 1895, having completed his naval service, Kharitonov returned to work as a cook in the Imperial Kitchen. Soon, he was sent for practice to Paris, where he studied at one of the best culinary schools and acquired a specialty in soup making.

In Paris, Kharitonov met the famous French restaurateur and culinary specialist, Jean-Pierre Cubat (1844-1922). In 1890s, Jean Pierre Cubat, at the personal request of Nicholas II, returned to manage the kitchen of the Imperial Court, where he served under the Tsar’s father and grandfather. This position he held until 1914. One of his contemporaries described Cubat as follows: ‘The maître d’hotel of the highest court was the famous owner of a restaurant on Morskaya Street in St. Petersburg, Pierre Cubat.’ The restaurant existed in St. Petersburg since 1850s and was originally called Restaurant de Paris (Café de Paris).’

Kharitonov and Cubat were friends, who occasionally corresponded, congratulating each other on the holidays. In 1911, Kharitonov was promoted to senior cook. Among other ��technical personnel’, he accompanied the Emperor on his trips abroad.

In 1914, Cubat left for France. His place was taken by Charles Olivier who became the Imperial maître d’hotel, immortalising his name with the famous salad – ‘salat Olivier’. Olivier worked at the Court of Nicholas II until February 1917. After his departure, Kharitonov became the de facto Imperial maître d’hotel.

On the photographs: top left: Pierre Cubat, top right: interiors of the Pierre Cubat restaurant; in the middle and bottom left: interiors of the Pierre Cubat restaurant; bottom right: exterior of the Pierre Cubat restaurant (originally Café de Paris).

#research#romanovs#investigation#nicolas ii#seraphima bogomolova#photographs#Ivan Mikhailovich Kharitonov#maître d’hotel#Imperial Kitchen#Jean-Pierre Cubat#Saint Petersburg

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Last Tsar: How Russia Commemorates the Brutal Communist Murder of Emperor Nikolai II's Family

Over 103 years ago, Bolsheviks shattered a royal line that had lasted for over three centuries

Portrait of Nicholas II at the monastery in the tract of Ganina Yama during the festival 'Royal Days', dedicated to the memory of the Romanov family, in Yekaterinburg. © Sputnik/Pavel Lisitsyn

On the night of July 16-17, 1918, the Bolsheviks shot the family of the last Russian tsar, Nicholas II. Eleven people were killed in total: The emperor, the empress, five of their children, and four royal servants. The remains were secretly buried in an abandoned mine, the location of which was hidden until the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The family of Nicholas II was subsequently canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church, and for the last 30 years, in mid-July, Christians from all over the world participate in a church procession from the murder site in Ekaterinburg to a monastery in Ganina Yama. An RT correspondent learned the story of this extrajudicial massacre and talked to pilgrims about their attitude to the Holy Royal Passion-Bearers.

In March of 1917, before the October Revolution, Russia’s provisional government decided to arrest the royal family. At first, the Romanov's lived at Tsarskoye Selo, but in August, they were forced to go to Tobolsk. In the spring of 1918, the group was moved to Ekaterinburg, where they stayed in the house of an engineer named Nikolay Ipatiev, which had been requisitioned by the Bolsheviks, and sometimes received food from the nuns of the Novo-Tikhvin convent.

On the night of July 16-17, 1918, Nicholas II, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, Grand Duchesses Anastasia, Tatiana, Olga, and Maria, Tsarevich Alexei, imperial doctor Evgeny Botkin, imperial cook Ivan Kharitonov, the empress’ housemaid Anna Demidova, and the tsar’s valet Aloysius Troup, were all shot by Bolsheviks under the command of Yakov Yurovsky.

Shortly afterwards, the murder of the royal family was investigated by Nikolay Alekseevich Sokolov, a judicial investigator for particularly important cases with the Omsk District Court. The civil war between the Communists and their opponents was still raging in Russia in 1918. On July 25, anti-Bolshevik forces from the Siberian army occupied Ekaterinburg.

At the beginning of February 1919, Sokolov was summoned by the Supreme Governor, Admiral Alexander Kolchak, and instructed to launch an investigation. After the execution of Kolchak by the Communists in the winter of 1920, the investigator left the country and continued to take testimony from witnesses in Western Europe. In Paris, he interviewed Prince Lvov, the former chairman of the provisional government’s Council of Ministers, as well as its former minister of justice, Kerensky, and minister of foreign affairs, Milyukov.

Kerensky cited two main reasons for the arrest of the tsar and his family. The first was the “agitated mood” of workers and soldiers who wanted to deal with the sovereign. The second was “high-ranking officers” who thought the emperor and empress intended to conclude a “separate peace” with Germany.

© Mark Bratchikov-Pogrebisskiy

Sokolov’s book entitled ‘The Murder of the Royal Family’, which contains materials from the investigation, was published in Berlin in 1925. He had been one step away from solving the mystery of whereabouts of the tsar’s remains but did not have time to discover them before the Bolsheviks took the area.

The key document containing details about the regicide is a note from 1920 written by Yurovsky, who had overseen the killing. According to his memoirs, on a night in July 1918, the royal family and their servants were told: “‘Due to unrest in the city, it is necessary to transfer the Romanov family from the upper floor to the lower one’… When the team entered, the commandant told the Romanovs that, since their relatives in Europe [probably meaning German troops under the leadership of the empress’ cousin, Emperor Wilhelm II – ed. note] were continuing their offensive against Soviet Russia… the [Ural] District’s executive committee had decided to shoot them. Nikolai turned his back to the team and faced his family. Then, as if coming to his senses, he turned to the commandant and asked: ‘What? What?’ The commandant hastily repeated his words and ordered the team to prepare. The team was told in advance who was to shoot at whom and ordered to aim directly at the heart in order to avoid a large amount of blood and end the affair as quickly as possible. Nikolai said nothing more and turned back to his family. The others uttered several incoherent exclamations for several seconds. Then the shooting began and lasted two to three minutes. Nikolai was killed on the spot by the commandant himself. Then, Alexandra Feodorovna and the Romanovs’ servants died immediately... Alexey, three of his sisters, the lady-in-waiting [Anna Demidova], and Botkin were still alive. This surprised the commandant, because they were aiming directly at the heart. They had to be shot again. It was also surprising that the bullets ricocheted off something, like hail, and bounced around the room. When they tried to stab one of the girls with a bayonet, the bayonet could not pierce the bodice. Thanks to all this, the whole procedure, counting the ‘check’, took 20 minutes.”

According to the note, the bodies were supposed to be buried in an abandoned mine nearby. However, shortly after the murder, it turned out that no one knew where it was, and nothing had been prepared to carry out the burial. In addition, the Bolsheviks were prevented from ending the affair as soon they wished, as the perpetrators of the murder made sporadic attempts to steal valuables from their victims. A car left Ekaterinburg with the bodies and stopped near the village of Koptyaki, where another abandoned mine was found in a nearby forest. The bodies were stripped and lowered down. The Bolsheviks tried to avoid inconvenient witnesses. They even announced in the village of Koptyaki that Czechs, who were armed opponents of the Soviet government, were hiding in the forest and that it would be searched. No one was allowed to leave the village. “The idea arose to bury some of the corpses right there in the mine,” Yurovsky writes. “They began to dig a hole and had almost dug it out when a peasant friend of Ermakov [who aided in hiding the bodies] drove up and it turned out that he could see the pit.”

In 2000, the monastery of the Holy Royal Passion-Bearers was established in the Ganina Yama tract. Some Orthodox consider this to be the final burial place of the royal remains.

© Mark Bratchikov-Pogrebisskiy

Later, at a meeting of old Bolsheviks in 1934, Yurovsky described the vicissitudes of the burial in more detail. On the morning of July 17, water covered the bodies that had been put in the mine. They wanted to blow up the mine with bombs, but nothing came of it. They decided to “transport the corpses to another place.” Yurovsky instructed his subordinates to remove the bodies. “I had a plan, in case any problems arose, to bury them in groups, in different places along the roadway.”

Then they began to dig a new hole, but at some point, the already mentioned acquaintance of Ermakov saw it and the plan failed.

“After waiting for evening, we loaded the cart… It was already approaching midnight when I decided it was necessary to bury them somewhere nearby, since no one could see this place… I sent them to get railroad ties to cover the place where the corpses would be buried... About two months ago, I was leafing through a book by Sokolov, the investigator on extremely important cases, and I saw a picture of these railway ties. It says that they had been laid there to help trucks pass. So, after digging up the whole area, they didn’t think to look under the railway ties.”

While Sokolov was able to find traces of members of the imperial family near the Ganina Yama, he never found the bodies themselves.

“A bonfire was immediately lit, and while the grave was being prepared, we burned two corpses: those of Alexei and Demidova [in fact, Grand Duchess Maria – ed. note], who we burned instead of Alexandra Feodorovna by mistake. A pit was dug near the fire. We put the bones in and covered it. Another large fire was lit on top, and all traces were hidden by ashes. Meanwhile, a mass grave was dug for the others… Before putting the rest of the corpses into the pit, we poured sulfuric acid over them. Then we lowered them into the pit, poured more sulfuric acid on them, filled in the pit, and covered it with railroad ties. The empty truck drove over them a few times to tamp them down and that was it. At 5-6am, we gathered everyone and explained the significance of what we’d done, warning that everyone should forget about what they’d seen and never talk about it with anyone. Then we went to the city.”

In 2015, an investigator in the Prosecutor General’s Office of the Russian Federation named Vladimir Solovyov said that Pyotr Voykov had written out a purchase order for sulfuric acid. A metro station in the north of Moscow still bears the name ‘Voykovskaya’.

© Mark Bratchikov-Pogrebisskiy

The imperial family’s final burial place under a platform of railway ties was not a secret for all Soviet citizens – apparently, high-ranking party functionaries knew about it. Literary critics believe that this place was even shown to the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky in 1928. The result of the visit was his poem ‘The Emperor’.

The first to discover the royal remains in Soviet times was geologist Alexander Avdonin, a graduate of the Ural Mining Institute. In the 1960s, Avdonin met Gennady Lisin from the Ural Worker publishing house. Lisin claimed that he’d been a member of the Boy Scouts and had helped White investigators search for the burial site in his youth. It was he who showed Avdonin Ganina Yama.

© Mark Bratchikov-Pogrebisskiy

In 1976, Geli Ryabov, a screenwriter from Moscow and an honored employee of the Soviet Ministry of Internal Affairs, went to Avdonin. A few years later, Avdonin thoroughly examined the Old Koptyakov Road, along which the Bolsheviks had once transported the bodies of the Romanovs. In the town of Porosenkov Log near Ekaterinburg, he found the same railway ties. Under them, the geologist managed to find skulls and bones. Ryabov took two skulls to Moscow in the hope of conducting an examination. However, no one agreed to help him before the collapse of the USSR. Later, Avdonin and Ryabov decided to rebury the wooden box containing the remains near the place it was discovered – until better times.

In 1989, Ryabov told the Moscow News that he had found the imperial remains, and interest in the tsarist mystery grew rapidly among amateur geologists. Avdonin began to worry about the fate of the remains and wrote a letter to the chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR, Boris Yeltsin, who instructed the governor of Sverdlovsk Region, Eduard Rossel, to deal with the issue.

© Mark Bratchikov-Pogrebisskiy

In 1993, Rossel was briefly the head of the Ural Republic, a de facto entity in the Russian Federation that was not provided for by the Constitution. The governor believed that the Urals should become more independent in economic and legislative terms. In November, the initiative was finally curtailed, and Rossel was dismissed. Ural historians and journalists suspect that the governor may have been using the royal remains as a bargaining chip with the federal authorities up until that moment.

In 1998, after numerous examinations, the remains were buried in the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg in the presence of Yeltsin. At that time, the Russian Orthodox Church did not recognize the authenticity of the remains, and Patriarch Alexy II did not attend the funeral.

© Mark Bratchikov-Pogrebisskiy

Among the discovered remains, two of the dead were missing. In 2007, a search team found the remains of Grand Duchess Maria and Tsarevich Alexei 75 meters from the main burial site.

In March 2022, ex-Metropolitan Hilarion of Volokolamsk, chairman of the Moscow Patriarchate’s Department for External Church Relations, stated that “We now have clear and sufficient evidence that the ‘Ekaterinburg remains’ are the genuine remains of members of the royal family… It seems to me that the arguments supporting the authenticity of the ‘Ekaterinburg remains’ significantly outwfeigh any arguments that could refute it.” The church could have officially recognized the authenticity of the remains at the Bishops’ Council in May, but this had to be postponed.

© Mark Bratchikov-Pogrebisskiy

Sixty years after the October Revolution, Ipatiev’s house was demolished. Yeltsin was then the first secretary of the Sverdlovsk Regional Committee of the CPSU. In 2003, a Church-on-Blood was erected on this site, and in 1992, the tradition of holding a penitential procession was born. Its current route was established in 1994.

The Romanov Memorial is now located in the Porosenkov Log tract. Ilya Korovin, the director of the memorial, who is a supporter of Avdonin’s theory concerning the preserved remains, told RT that the procession route does not include this cultural heritage site.

© Mark Bratchikov-Pogrebisskiy

In 2018, Patriarch Kirill participated in the procession. After four years, believers again walk around 20 kilometers from the Church-on-Blood to the monastery of the Holy Royal Passion-Bearers in the Ganina Yama tract. This year, there were 50,000 pilgrims, according to the St. Catherine’s Foundation.

In conversations with RT during the procession, believers shared their views on whether the Church should officially recognize the royal remains. Some believe this would be the right thing to do, putting an end to the ‘biggest crime’ in Russian history. Others, on the contrary, do not believe the remains found by Avdonin are authentic, holding that they were probably destroyed in Ganina Yama.

© Mark Bratchikov-Pogrebisskiy

The procession begins at 2:30am Ural time. It is headed by church leaders, followed by a long column of Orthodox Christians, who hail not only from Russia, but also from Western Europe, Latin America, and Asia. In less than four hours, the first pilgrims appear at the final point of the route – the monastery at Ganina Yama. Orthodox Christians in comfortable sneakers carrying bottles of water cheerfully sing “Lord, Jesus Christ, have mercy on us!” The former mine is now enclosed by a gallery filled with portraits of the royal passion-bearers and their faithful servants.

RT spoke with people born in the Urals who say that they participated in the procession as children, and now help their elderly parents walk along this long route.

— By Mark Bratchikov-Pogrebisskiy, a Moscow-based Journalist | RT | August 14, 2022

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the early hours of 17th July 1918, the entire Imperial Family along with their servants, were brutally murdered in the cellar of the Ipatiev House.

Around midnight, Yakov Yurovsky ordered the family physician, Eugene Botkin, to awaken the family and ask them to put on their clothes, under the pretext that the family would be moved to a safe location due to impending chaos in Ekaterinburg. They were led in the semi-darkness steep, narrow stairs to the ground floor. Instinctively the Romanovs followed the order of precedence instilled in them, the Tsar in front but refusing assistance as he struggled with the burden of Alexei, who winced with pain from his bandaged leg; then Alexandra leaning heavily on Olga’s arm, followed by Tatiana, Maria, and Anastasia. As they made their way to the stairs, the family paused and devoutly crossed themselves at the stuffed mother bear and her cubs that stood on the landing — a sign of respect for the dead, thinking as they did that they were going to be leaving the house.

Following the family came Dr Botkin, Alexei Trupp (Tsar’s footman), Anna Demidova (Tsarina’s maid), and Ivan Kharitonov (the family’s cook). They all exited the house, re-entering by another, adjacent door leading down into the basement. Nicholas asked if Yurovsky could bring two chairs, on which Tsarevich Alexei and Alexandra sat. Yurovsky's assistant Grigory Nikulin remarked to him that the "heir wanted to die in a chair. Very well then, let him have one."

The prisoners were told to wait in the cellar room while the truck that would transport them was being brought to the House. A few minutes later, an execution squad of secret police was brought in and Yurovsky read aloud the order given to him by the Ural Executive Committee:

“Nikolai Alexandrovich, in view of the fact that your relatives are continuing their attack on Soviet Russia, the Ural Executive Committee has decided to execute you.”

Nicholas, facing his family, turned and said "What? What?" Yurovsky quickly repeated the order and the weapons were raised.

#romanovs#history#royalty#myedits#nicholas ii#alexandra feodorovna#otma#alexei nikolaevich#tsarevich alexei#olga nikolaevna#tatiana nikolaevna#maria nikolaevna#anastasia nikolaevna#imperial russia

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Not to tone police here on main but I have problems with the way some people frame the execution of Nicholas II. and his family (+ other people, we’ll get there).

Don’t get me wrong, they definitely didn’t deserve what happened to them, it’s still shocking and people responsible should be condemned. Far be it from me to say a disabled 14-year old deserved to be murdered, watching his whole family and several other people being massacred alongside him. What I object to is the whole framing of “royal martyrs”, as if their deaths were uniquely tragic. Because they weren’t - heck, Nicholas II. and his family weren’t even the only people on site shot to death! There were also the last members of their staff, Yevgeny Botkin, Anna Demidova, Alexei Trupp and Ivan Kharitonov. Their deaths were no less brutal, tragic and worth remembering just because they were not of royal blood. Just like Nicholas’ wife and children, their one crime was just... Being there, at the wrong place, in the wrong time. Romanovs get all the glory of martyrdom in popular imagination, because, well, they were famous (And a bit of royalist propaganda, sometimes. And the fact that people imagine Nicholas’ children as, well, children, which they weren’t really - Alexei was 14, and his sisters all basically adults.). They were known even before their deaths, so they were remembered afterwards. Which means they became symbols...

Of what exactly? Well, a lot of things - monarchism, Orthodox martyrdom, bolshevik terror - but I think “victims of the Russian Civil War” is what they SHOULD symbolize. Because when I say there is no worse enemy for a Russian than a Russian, this is what I am talking about. This was the most devastating conflict on Russian soil with the exception of World War II, and unlike World War II Russia doesn’t even get the satisfaction of eventual victory. Both sides committed unimaginable attrocities, and the result was one of them getting to stay in power to keep committing them. Nicholas II, his family and people employed by them were far from the only people shot without a trial. In our imagination, they could stand for all of those hundreds of thousands - because it’s easy to fall for the “million is a statistic” effect when we look at the mere numbers, but when we imagine all of those people died just like and sometimes in worse ways than victims of the Ipatiev House executions... YEAH.

#house of romanov#romanovs#random history#minette complains#then subsequently cries into a pillow#russia

3 notes

·

View notes