#roman concrete

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

*In ancient Rome*

Graham: "Alright, the Doc should've met us back here 20 minutes ago, I know she's not the best with time, but I'm getting worried."

Yaz: "Me too. Maybe we should look around for her? She could be in trouble."

Ryan: "She is prone to that. Let's go."

*After 10 minutes of searching, they spot her in an alley. She is laying face down on the ground. They run towards her.*

Yaz: "Doctor!"

*The fam is relieved to receive a waving thumbs up from the horizontal alien, but she does not get up. As they approach her, they can hear unintelligible mumbles. Yaz moves the Doctors hair aside and Ryan laughs as it is revealed that her tongue is stuck to the ground*

Doctor: *Attempted sigh*

———

*Back in the TARDIS, in the med bay*

The Doctor, speaking around a bag of ice: "I'm sorry, you guys, their concrete is just so intriguing..."

#13th doctor#thirteenth doctor#yasmin khan#ryan sinclair#graham o'brien#dw dialogue:)#dw thoughts:)#doctor who#dw#nuwho#the doctor#chibnall era#ancient rome#roman concrete#ancient roman concrete

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pantheon 2024

#pantheon#rome#ancient rome#italy#italytravel#pantheon di roma#roma#architecture#old architecture#architecture archive#seven wonders#ancient history#ancient civilizations#roman empire#ancient architecture#roman concrete#concrete#church#church italy#night#sightseeing#nightlife#architecture photography#travel

12 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

We solved Roman concrete #shorts #science #SciShow

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Roman Concrete: Mystery of Why Roman Buildings Have Survived so long has been Unraveled

The majestic structures of ancient Rome have survived for millennia — a testament to the ingenuity of Roman engineers, who perfected the use of concrete.

But how did their construction materials help keep colossal buildings like the Pantheon (which has the world's largest unreinforced dome) and the Colosseum standing for more than 2,000 years?

Roman concrete, in many cases, has proven to be longer-lasting than its modern equivalent, which can deteriorate within decades. Now, scientists behind a new study say they have uncovered the mystery ingredient that allowed the Romans to make their construction material so durable and build elaborate structures in challenging places such as docks, sewers and earthquake zones.

The study team, including researchers from the United States, Italy and Switzerland, analyzed 2,000-year-old concrete samples that were taken from a city wall at the archaeological site of Privernum, in central Italy, and are similar in composition to other concrete found throughout the Roman Empire.

They found that white chunks in the concrete, referred to as lime clasts, gave the concrete the ability to heal cracks that formed over time. The white chunks previously had been overlooked as evidence of sloppy mixing or poor-quality raw material.

"For me, it was really difficult to believe that ancient Roman (engineers) would not do a good job because they really made careful effort when choosing and processing materials," said study author Admir Masic, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

"Scholars wrote down precise recipes and imposed them on construction sites (across the Roman Empire)," Masic added.

The new finding could help make manufacturing today's concrete more sustainable, potentially shaking up society as the Romans once did. "Concrete allowed the Romans to have an architectural revolution," Masic said. "Romans were able to create and turn the cities into something that is extraordinary and beautiful to live in. And that revolution basically changed completely the way humans live." Lime clasts and concrete's durability

Concrete is essentially artificial stone or rock, formed by mixing cement, a binding agent typically made from limestone, water, fine aggregate (sand or finely crushed rock ) and coarse aggregate (gravel or crushed rock).

Roman texts had suggested the use of slaked lime (when lime is first combined with water before being mixed) in the binding agent, and that's why scholars had assumed that this was how Roman concrete was made, Masic said.

With further study, the researchers concluded that lime clasts arose because of the use of quicklime (calcium oxide) — the most reactive, and dangerous, dry form of limestone — when mixing the concrete, rather than or in addition to slaked lime.

Additional analysis of the concrete showed that the lime clasts formed at extreme temperatures expected from the use of quicklime, and "hot mixing" was key to the concrete's durable nature.

The benefits of hot mixing are twofold," Masic said in a news release. "First, when the overall concrete is heated to high temperatures, it allows chemistries that are not possible if you only used slaked lime, producing high-temperature-associated compounds that would not otherwise form. Second, this increased temperature significantly reduces curing and setting times since all the reactions are accelerated, allowing for much faster construction."

To investigate whether the lime clasts were responsible for Roman concrete's apparent ability to repair itself, the team conducted an experiment.

They made two samples of concrete, one following Roman formulations and the other made to modern standards, and deliberately cracked them. After two weeks, water could not flow through the concrete made with a Roman recipe, whereas it passed right through the chunk of concrete made without quicklime.

Their findings suggest that the lime clasts can dissolve into cracks and recrystallize after exposure to water, healing cracks created by weathering before they spread. The researchers said this self-healing potential could pave the way to producing more long-lasting, and thus more sustainable, modern concrete. Such a move would reduce concrete's carbon footprint, which accounts for up to 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions, according to the study.

For many years, researchers had thought that volcanic ash from the area of Pozzuoli, on the Bay of Naples, was what made Roman concrete so strong. This kind of ash was transported across the vast Roman empire to be used in construction, and was described as a key ingredient for concrete in accounts by architects and historians at the time.

Masic said that both components are important, but lime was overlooked in the past.

The research was published in the journal Science Advances.

By Katie Hunt.

#Mystery of Why Roman Buildings Have Survived so long has been Unraveled#roman concrete#the pantheon#the colosseum#roman engineers#architecture#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient rome#roman history#roman empire#roman buildings#long reads

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

No, I don't want to read Icebreaker. You know what I want to do? Watch a YouTube video about how Roman concrete is so much more durable than modern day concrete. So much so that scientists, archeologists, and historians gathered around to figure it out. Scratching their heads like damn what was the recipe, what kind of ingredients did they mix in their concrete.

#Roman concrete#booktok is no safe place for me#Roman#roman architecture#they mixed volcanic ash and lime#i love rocks

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Weird thought process, but I was thinking about the TMA solution of just burying entities in concrete, which made me think of what archeologists would think if they excavated them (or what would happen to the archeologists, lol).

But now I'm thinking how easy is it to actually detect bodies in concrete? Like, burying ppl in concrete to cover murder is a common plot device and I'm sure it's happened a decent number of times. Will archeologists eventually find them? And what about older concrete? How long have humans been burying others in it, or have ppl just accidentally fallen in and died?

Could there be ppl in really really old concrete? Like, was roman concrete used for foundations at all? And are there still any around?

#lmfao#archeology#roman concrete#tma#the magnus archives#random thoughts#who would I even ask this to?

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lostech

For a clear example of how mere knowledge that something was once possible, surviving examples of a thing, or even partial records of production are of very limited benefit in rediscovering how to manufacture a lost technology, look no further than Roman concrete.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

told my bf that the secret ingredient in roman concrete was vanilla extract and he believed me so who's really winning here

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

How old technology can help us in our current times.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Few elements of its legacy impress us as much as its buildings and infrastructure and what’s left of its built environment. Still, the fact that anything remains at all of the structures built by the Romans tells us that they were doing construction right.

Just how the Romans made that astonishingly durable concrete building material has been a subject of research even in recent years.

Such is the task of Shawn Kelly, host of the Youtube channel Corporal’s Corner, in the video above. Using materials like volcanic ash, pumice and limestone, he makes a brick that looks more than solid enough to go up against any modern concrete.

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

Hot-mixing with quicklime instead of slaked, very clever...

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

ancient Romans watching vanilla that was imported at great expense being mixed with rocks & sea water:

26K notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Roman Concrete: Lasted Thousands of Years

Ancient Roman structures, from aqueducts to the Pantheon, have stood for centuries, defying time and weather. Central to their endurance is pozzolanic concrete, a blend of volcanic ash and lime that gives Roman concrete remarkable durability. New research was led by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). It has revealed that the Romans had more to their methods than we realized. Modern…

0 notes

Text

Why Roman Concrete: Lasted Thousands of Years

Ancient Roman structures, from aqueducts to the Pantheon, have stood for centuries, defying time and weather. Central to their endurance is pozzolanic concrete, a blend of volcanic ash and lime that gives Roman concrete remarkable durability. New research was led by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). It has revealed that the Romans had more to their methods than we realized. Modern…

0 notes

Text

I mean, you’re wrong about the cement, the steel, and misleading about the violins and the space program:

The Roman secret to cement that doesn’t go bad near the sea is “use seawater, idiot” (all the Roman recipes just say “water”)

We don’t know how ancient civilisations made Damascus steel, the same way we don’t know how the Byzantines made Greek fire. We do know how to make things as good or better that look the same, we just don’t know the exact method they used.

As far as violin makers go that’s a bespoke art requiring extraordinary craftsfolk - it’s not like we don’t know how to make them, we just don’t necessarily have the Freddie Mercury of violin-making alive and working at every given moment

You also don’t know what “missing the technology” means in the context of the late 1900s space programs: it means we don’t use the manufacturing methods, make old and outdated parts, or otherwise have the ability to assemble them exactly as they were. Technology is about what your society can make, not what it knows how to do - we absolutely could manufacture those things that way but why the fuck would we when we have better stuff now?

You’re absolutely right that everything isn’t constantly improving - take a look at the current social media apocalypse, the housing bubble, and the lack of unbroken melee martial arts lineages to name a few things. But remember that what is lost can be recovered, what is gone can be rebuilt, and it is the great folly of assuming the present is always better than the past that stifles innovation (Victorian treatment of historical artefacts comes to mind, as well as their mystification of the sharpness of eastern swords (since most of the western traditions were greatly reduced and not all soldiers cared for their swords as well in the age of guns compared to nations at the height of that particular technology))

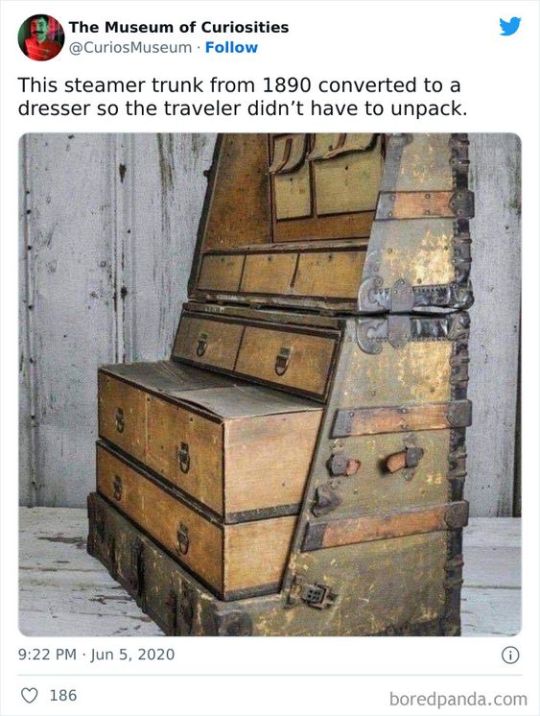

So yeah. Your suitcase is lighter than that monstrosity (affectionate) which is more structured.. but wouldn’t it be cool if someone applied drawers and partitions to a modern suitcase?

#history#repeating history#Roman concrete#damascus steel#Stradivarius violins#apollo space program#learning from the past#for a kinder world!

59K notes

·

View notes