#richard abneg

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Rise of the Brave

by suseagull5914 “Your results were inconclusive,” she whispered so quietly he could barely hear her. “Incon-” She slapped a hand over his mouth forcefully enough that he stopped talking immediately, speaking quickly and quietly directly in his ear. “Yes, inconclusive. I had to manipulate the test so it gave you three different scenarios, and you tested positive for Erudite, Abnegation, Amity, and Dauntless." Or: The day when Alex will be tested to find out which faction he's in is here, and the results will change his life- and his entire world- forever. Words: 5846, Chapters: 1/26, Language: English Fandoms: Red White & Royal Blue - Casey McQuiston Rating: Teen And Up Audiences Warnings: No Archive Warnings Apply Categories: F/F, M/M Characters: Alex Claremont-Diaz, June Claremont-Diaz, Nora Holleran, Henry Fox-Mountchristen-Windsor, Zahra Bankston, Queen Mary (Red White & Royal Blue), Shaan Srivastava, Jeffrey Richards, Beatrice Fox-Mountchristen-Windsor Relationships: June Claremont-Diaz/Nora Holleran, Alex Claremont-Diaz/Henry Fox-Mountchristen-Windsor Additional Tags: Angst with a Happy Ending, Alternate Universe - Divergent Fusion, Implied/Referenced Homophobia, Alex Claremont-Diaz Speaks Spanish, Getting Together via https://ift.tt/uhZGO6Y

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scorsese calibrates her place in the film with a delicate sense of form. She is not only the character on whose actions the drama pivots but also the one whose subjectivity, presented sparingly but suggested powerfully, gives the story a sense of inner life.

...In “Killers,” Mollie knows and feels far more than she says, and the depth of her insight is concentrated in Gladstone’s fixed and relentless gaze. The movie doesn’t explain what Mollie is thinking while her sisters are dying young, or while she’s getting sicker during Ernest’s treatments. It doesn’t explain what Ernest thinks when he’s first put up to nonviolent crime and then is dispatched on lethal errands. The character psychology of “Killers of the Flower Moon” is minimal—because Scorsese instead presses its action furiously, urgently, onto the screen as if it were something like a dramatized documentary in the first person, his own bearing of witness. The confrontational political view of American life that he unleashes in his previous film, “The Irishman”—a furious work made in furious times and, like this one, a film with silence at its core—here reaches even more deeply into the core of national identity, and into Scorsese’s own self-image.

The silences that Mollie brings to bear, through Gladstone’s performance, on the horrific and outrageous doings are mightily reverberant, reminiscent of the silent testimony to horror that Anna Paquin performs in “The Irishman,” playing a gangster’s daughter. But there’s a crucial difference: in “Killers,” Mollie isn’t the miscreant’s daughter but his wife. Scorsese presents the marriage story, the story of love, as an absolute—something that is set apart from cultural, historical, and political particulars and that has the supreme power of religious faith. It is a commitment that extends even to extremes of self-abnegation and self-sacrifice, and that resounds with a fearsome silent thunder when that faith is renounced. The scene of that break is among the most devastating in Scorsese’s career.

Richard Brody, The Silent Thunder of “Killers of the Flower Moon

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Threats (14. 2. 2025):

- The title, length, and framing of this video (The hands in the art piece in the background constituting a coded reference to a painting of, IIRC Stalin in Jordan Peterson’s house, who’s fist was drawn disproportionately large): https://youtu.be/zI9I2unDqeI (A threat in initial reference to (a) front alter(s) of Taylor Swift and me getting tortured for a lifetime)

- “Kevin O’Leary”

- https://youtu.be/Yo2gXFQhy6Y (A threat in initial reference to me getting castrated and/or a threat in partial reference to me getting tortured (potentially, for a lifetime))

- Mental image revolving around ‘Amazona’ (The person who might be referred to, here: https://x.com/sedereragain/status/1792730232698687611?s=46&t=8BkusnIkW2uki99TqYWYEw) - “(Surrounding) Mikhaila Peterson” - “Scarlett”

- The dial of the Richard Mille in this video (https://youtu.be/sYItqG631iY) being reminiscent of the cover of ‘Lana Del Rey - Young and Beautiful’ (https://youtu.be/Te11UaHOHMQ) - The mat in the elevator having been wrinkled like a spider - The elevator stopping on the second floor (and no one was there) - A white truck with the labels ‘GH’ (in blue and red, colors symbolic for ‘As above, so below’), ‘Neue Bäder’ (Ger: ‘New pools’, in initial reference to a renewal of targets for getting tortured, killed or otherwise harmed) and small shapes reminiscent of those on Bryan Johnson’s shirt, here: https://youtu.be/3kAiPSEnrHI - Ovulation smells a few times, disgusting smells a few times, a sweet smell (*As far as I can remember, only once) - The exit door of the grocery store making inauspicious sounds, as I was standing outside of it, trying out Kinder (“Tarrot”) cards (https://bit.ly/3WI6S8C) while my glove was apparently getting stolen (In initial reference to (a) front alter(s) of Taylor Swift and/or Lana Del Rey and/or anyone of my followers having potentially gotten tortured and/or killed and/or in partial reference to such being ongoing or an ongoing threat (potentially, for a lifetime). In initial reference to (potentially, (a) front alter(s) of Lana Del Rey and/or Kevin O’Leary and/or Peer Ederer (my father) and/or (potentially, an ex front alter) of Taylor Swift as having potentially commanded, negotiated, abnegated or perpetrating such. And/or a threat in partial reference to children getting tortured, in initial reference to (a) male Delta alter of Taylor Swift as having potentially commanded, negotiated, abnegated or perpetrating such)

______________________________________________

Reports:

______________________________________________

How I handle threats I receive (Last Update: 14. 2. 2025):

Added:

- “See also: https://imgur.com/a/U9fJTtR“ to my paragraph making recommendations for resisting.

0 notes

Text

If you presuppose all humans have a right to life, that means you can't kill humans if there's another option. Which means *in cases where there's another option* that option should be taken.

Sure, I agree with this. My point is there is not another option. I'm not a fan of mob justice either, but the courts, as we are currently seeing with their pathetic inability to deal with Donald Trump and Israel's genocide, are not always going to be a valid alternative. Courts are not actually any more qualified to make this decision than "individuals" -- the entire legal system almost entirely revolves on the whims of judges, and the remaining "almost" revolves on the whims of lawmakers paid for and paid off by capital interests. It would be great if the criminal justice system was a perfect, Godly authority we could abnegate our morality to, but it isn't. You can't fight a corrupt system with the tools of that system.

The impression I'm getting here is that you're arguing in abstract philosophical principles of what the world should look like -- and yes, in an ideal world everyone should have a right to life and no one should have to die. This does not change the fact that if billionaires continue as they are, we will all die. If other people do not respect your right to life, you are justified in not respecting theirs either. That is self-defense.

You can sneer "Good luck with killing every billionaire," all you want, your plan of "The only way to fight a billionaire is to break their cult of personality and lame their ability to do heinous shit," isn't any more attainable or any less pie-in-the-sky.

Also, remember that man who punched Richard Spenser(known nazi)? Great alternative to killing the guy. Ruined his reputation. If he'd done a murder then Spencer would've become a martyr (murdered for his view in broad daylight!). Instead, he was thoroughly demasculated on camera and lost his career.

Also, this does not seem relevant to this discussion. This is an argument against murder on practical grounds, but the crux of your argument is that murder is wrong on moral grounds. Those are completely different arguments.

"they deserve to die" is something you should never hear a leftist say. if you do, run

12K notes

·

View notes

Photo

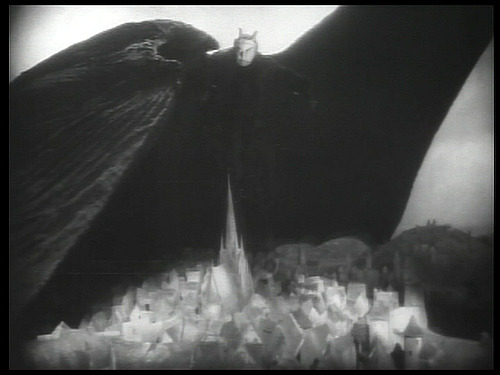

Faust (F.W. Murnau, 1926)

Cast: Gösta Ekman, Emil Jannings, Camilla Horn, Frida Richard, William Dieterle, Yvette Guilbert, Eric Barclay, Hanna Ralph, Werner Fuetterer. Screenplay and titles: Gerhart Hauptmann, Hans Kyser, based on a play by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Cinematography: Carl Hoffmann. Art direction: Robert Herlth, Walter Röhrig. Film editing: Effi Bötrich.

Power corrupts, as we knew long before Lord Acton so nicely formulated it for us. It's the truth underlying so many myths, from the Garden of Eden to the Nibelungenlied to the Faust legend. Goethe's Faust is a philosophical poem, a closet drama not designed for stage or film, but that hasn't prevented playwrights, opera librettists, or screenwriters from making the attempt. F.W. Murnau's version is probably the most distinguished cinematic attempt, but not because of its fidelity to the source. Murnau's version works because it concentrates on the power struggle, initially between Good, as represented by the archangel (Werner Fuetterer), and Evil, as represented by Mephisto (Emil Jannings), and later by the attempt of Faust (Gösta Ekman) to obtain mastery over Time. It begins with a wager, borrowed from the book of Job, between the archangel and Mephisto, over whom Faust's soul will belong to. Then it eventually devolves into what is the core of most dramatic treatments of Goethe's story, the seduction of Gretchen (Camilla Horn), with the aid of Mephisto. In the end, both Gretchen and Faust are redeemed by his willingness to sacrifice himself, an abnegation of power. But that too-familiar story is distinguished by Murnau's staging of it, with the significant help of Carl Hoffmann's cinematography and the art direction of Robert Herlth and Walter Röhrig. This is one of the most beautiful of silent films because of the interplay between light and dark, a superb evocation of the paintings of Rembrandt in the composition and lighting of scenes. The tone of the film is set near the beginning by the spectacular image of a gigantic Mephisto looming over a German town, which clearly influenced the similar scene in the "Night on Bald Mountain" sequence of Walt Disney's Fantasia (1940). Jannings manages to be both sinister and gross as Mephisto -- the latter mode most in evidence in his scenes with Gretchen's lustful Aunt Marthe (Yvette Guilbert). (If Guilbert looks familiar it's because, as a Parisian cabaret singer during the Belle Époque, she was the subject of numerous portraits by Toulouse-Lautrec.) This was the last of Murnau's films in Germany: The following year he moved to Hollywood, where he made probably his greatest film, Sunrise. He was soon followed to America by the actor who played Gretchen's brother, Valentin, William Dieterle, who became a prominent Hollywood director.

Top: Yvette Guilbert and Emil Jannings in Faust. Bottom: Yvette Guilbert by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 100 7x11 Etherea

This is the episode we’ve been waiting for this whole season - and while I don’t think it’s the best episode of the season, it is certainly the most exciting one. It would be that just the fact that Bellamy is finally back on screen (and not just for a couple of minutes, but for an entire episode fully focused on him), and it was great to see him and have an episode fully devoted to him, and remember once again what an amazing actor Bob is and the presence and intensity he brings to the show. But it also turned out to be the first episode of season 7 that is a genuine game changer and that shocked the viewers with a twist that wasn’t entirely predictable.

Even though the fandom had been speculating on the so-called brainwashed Bellamy or “void Bellamy” or generally Bellamy that is for some reason the (temporary) enemy of Clarke, Octavia and the rest of the protagonists, and hoping for that storyline, with a Mockingjay-like possibilities for romantic angst between him and Clarke (especially after a photo of Bellamy in the white robe leaked early in the year, months before the season even started to air), the way it happened seems to have upset many of the fans )to quote a podcaster, “I was hoping for a brainwashed Bellamy, but not like this”). Probably because the show has Bellamy retain agency in his transformation and that it is indoctrination into a cult be more like real life and partially rooted in Bellamy’s own emotional issues, beliefs and needs, rather than taking the easier route of having him be Sci-Fi brainwashed, Winter Soldier style.

That said, I’m still not entirely sure how I feel about this episode and how good I think it is. The first half of the episode, Bellamy was very much himself, and it was focused on survival and trying to get off the planet, and the dynamic between him and Conductor Doucette - throughout the episode - seems to play into the familiar trope of two enemies, or people of opposing views, who have to spend time together, gets to argue, survive together, and eventually bond as fellow humans. This story would not be particularly interesting - not only have we seen it many times, but it feels redundant for Bellamy, who has learned to see the POV of his enemies, bond with them and see the common humanity in them, many seasons ago. It also would not have been interesting if Bellamy managed to change Doucette’s beliefs - which the audience already thinks are rubbish - as this wouldn’t tell us anything new about Bellamy and would only give development to Doucette.

But instead, what was really happening throughout this episode, under the guise of bonding with the enemy, was Bellamy’s spiritual journey - aka his indoctrination into Cadogan’s cult. The crucial part of it happens not just to his exhaustion and desperation in tough circumstances, or his companion offering him faith as a solution, but through something Bellamy actually sees in the cave, and his own visions a little later. This is where the episode becomes a lot more interesting - and also a lot more frustrating. I don’t think I’ll be sure how I feel about this until I see the rest of the season, and learn how some things from this episode are explained or followed up on. In particular, the explanation (or lack of it?) for Bellamy’s visions in this episode will pretty much determine what course the show is taking in its final season and what it is trying to be.

Whatever the explanation, the end result - which we see after Bellamy returns to Bardo - is disturbing and painful to watch. It is something we have never seen before - Bellamy himself trying to enforce a total abnegation of everything Bellamy Blake is. Which includes willingly repressing his feelings for his loved ones to the point of betraying them (and results in the most painful Bellarke reunion ever, and one of the most painful reunions of the Blake siblings). I don’t know if I’m fully buying such a huge transformation - which is one of my problems with the episode. But this is certainly quality angst, and means that the season has become much more exciting to watch.

Is it weird that such a big twist happens in episode 11, out of 16 episodes, after 10 episodes that have been mostly setup for the big plot? Yes, just like it is weird that Bellamy has been MIA before this. BTS reasons obviously affected this season a lot - if it hadn’t been for them, I think we’d have a similar storyline, but this would have happened much earlier in the season. Are 5 episodes enough to resolve this in a satisfactory way? Well, it’s certainly enough to resolve it - this is a show that has characters go from hate to love over the course of 5 episodes, has characters hook up/fall for each other after knowing each other for 2-3 episodes, the show that showed Hope’s entire 10-year relationship with her father figure in a 7 minute scene, and the show that just had this massive character transformation happen over one episode. Will it feel satisfactory and convincing - it could, if it’s well-written and if the show doesn’t waste too much time on the Sanctum plot and fully focuses on its two main characters now that one of them is finally back.

Starting from the beginning - this time, its Bob saying “Previously on”, in line with this season having different cast members saying those opening words in different episodes (Eliza in 7x01, Marie in 7x02, Luisa in 7x03, there was no previously on in 7x04, Marie in 7x05, Lindsey in 7x06, Richard in 7x07, no previously on in 7x08, Eliza in 7x09 and 7x10 - it’s a bit surprising that Eliza said it in episode 9 even though she wasn’t in it at all, but otherwise those fit characters that were strongly featured in the episode in question).

We also get yet another version of the opening titles - which start and finish with a shot of the Anomaly. Earth again makes a cameo near the end, just as it did in 7x10, though it’s in the shadow now so can’t be seen as clearly.

While 90% of the episode takes place on Etherea, it opens and ends on Bardo. The opening scene is the only one not featuring Bellamy - apart from a replayed memory. We learn that the MCap machine was damaged by Echo, and is only now operational again. Finally, a good explanation why the Disciples did not put Echo, Diyoza or Octavia - again - in MCap after they agreed to cooperate. Levitt is using it on one of the Disciples who were in the Stone Room during the explosion. I guess he was still recovering a week after, and now they are presumably trying to help him, since - as the other Conductor tells Levitt - he is suffering from PTSD. Hey, isn’t that the first time anyone has mentioned that word on the show? At least the Disciples have kept the knowledge about mental health issues, even if their ways of dealing with it are questionable at best. We learn that no one is being punished, not even for killing Anders, as the other conductor says. (Not even? Does she think that’s worse than attempted genocide? Hope didn’t even back down from it as Echo eventually did, and the two Disciples Anders called witnessed it. The Conductor may think that the consequence is more important than intent... But even so, she clearly thinks Anders’ life was more important than those of two other Disciples, who were murdered by Echo as a part of her torturing Levitt. I guess that “For all mankind” thing doesn’t mean you consider all of the people, or even all of the Disciples, equal...)

Levitt finds out what 99% of the audience was sure of anyway and goes “He’s alive!” Surprise, surprise. But Levitt, shouldn’t you say “They are alive?”? Knowing Levitt’s attachment to Octavia, he is talking about Bellamy, not about one of his colleagues, Conductor Doucette, who was also presumed dead. (Doucette, not Douchette - even though the latter would make for a good joke.)

Let’s think about why this scene exists (apart from being used as a sneak peek). Obviously it was full of exposition, but why was it important for Levitt to find out that Bellamy is alive at the same time as we learn about it? We could have just seen Bellamy falling through the Bridge to the planet of Etherea. I suppose the purpose is dual: 1) to learn that the Disciples indeed did not know Bellamy was alive and on Etherea, 2) to learn that Cadogan knew Bellamy was alive an on Etherea, at least a few hours to a day before his return, which may be important for the events of this episode.

One of the questions the fandom has been debating is, did Anders intentionally send Bellamy to Etherea to be indoctrinated? Since 7x05, I have believed that Bellamy was on Etherea, and my initial reading of the scene was that Anders made the decision to send him there - and that this was why Doucette started to beg him: “Please, sir, no”, as he wasn’t happy to be stranded there. Then I started second-guessing it, because it became increasingly obvious that Anders was dumb as a brick and unable to come up with any smart plans how to brainwash people (as we saw with HEDO - he just threatened them into compliance instead of trying to really change their minds). Now I think that sending people to Etherea may be a standard practice that Disciples do on very special occasions when they want to send someone on a spiritual journey/pilgrimage/true brainwashing that they can’t come back until they make a ‘leap of faith” (just like they use Skyring as a standard prison). Maybe this is not even something that most Disciples know, but info only reserved for Level 12s or even Level 13s. But the grenade attack was real and made Anders believe Bellamy was dead and the plan was off - as there is no reason to believe that anything before Bellamy’s last day in the cave was manipulated from Bardo.

However, that last day - with Bellamy’s visions - could have been, and it happened around the same time Cadogan would have found out from Levitt that Bellamy was alive and on Etherea. There seems to be no time differential (or too small a differential to matter) between Etherea and Bardo - just like there seems to be none between Earth and Sanctum, since Bellamy and Doucette retained their memories going from Bardo to Etherea and back, both times without a protective helmet.

Etherea, the planet

The promo for this episode made the planet look much worse and less survivable than it really seems to be. Apart from the grey filter* that the show is using to make it look worse and kind of drab and gloomy, it seems to be a perfectly nice planet, with vegetation and an OK climate - as long as you are not trying to get off the planet through the Anomaly and climbing the extremely high mountain to reach the Anomaly Stone. It’s funny that, aside from Nakara, every other planet connected by the Anomaly has better living conditions than Bardo. The Disciples obviously use Bardo just because of the facilities they’ve found there. But Skyring is a really lovely planet - its only problem is the time differential from the other habitable planets, but that would not be a problem if a big group of people just decided to live there and start a community. Sanctum is lovely, too - well, except for red sun toxin and killer insects and meat-eating trees. (Why have the Disciples mostly ignored it? Is it because of those things, or maybe they didn’t want to mix with the Primes and other Sanctumites? Or they just didn’t see a use for it?) And Etherea is another problem where people could decide to live, if they gave up going to other planets.

*The show uses different filters to make the woods around Vancouver look like different planets:

Sanctum - bright colors, lots of red during day, purple at night

Skyring - blue filter (nice planet)

Nakara - blue filter (frozen planet)

Etherea - grey filter

Earth - normal, except in S5 everywhere outside Eden - greyish yellow filter for a desolated post-Praimfaya Earth

But of course, Bellamy is definitely not interested in staying there and only wants to find a way off this planet, and Doucette, unlike Orlando, is neither serving a sentence he wants to see to the end nor is expecting the Disciples to send a team to retrieve him. This is another one of the “just two three four people on the planet” episodes, but this stay is just a few months rather than years, and spent in much harsher and most exhausting conditions during most of that time - because Bellamy never stops trying to get off the planet. There are parallels and strong contrasts to every one of those other situations:

Eden - The first few months of Clarke’s experience surviving on the desolated Earth parallel Bellamy’s months on the mountain - surviving in tough conditions (extreme heat in Clarke’s case vs extreme cold in Bellamy’s), physically and mentally exhausted to the point of breaking. There are even visually parallel shots of both of them walking with a stick or eating bugs. But the big differences are: after trying and failing to get in the bunker and after the Temple collapsed, Clarke had no way of getting off the planet or out of her current situation and reuniting with any of her loved ones. She could only survive and wait. She was all alone and only talking to Bellamy, who wasn’t there, to keep herself sane. Bellamy, OTOH, was actively trying to get off the planet and reach his loved ones all that time, and he had a companion - another adult with strong beliefs, who he talked to and who did his best to indoctrinate him. After those first few months, Clarke found Eden and met Madi, and the rest of her (mostly off-screen) life on Earth during the next 6 years was much more similar to Octavia’s life with Diyoza and Hope on Skyring.

The Garden - Unlike Bellamy, Octavia lived in a beautiful place and with someone who was already her friend and a child she came to look after, finding family she loved (rather than faith and abstract “love for all mankind”). Like Bellamy, Octavia kept trying to get off the planet and reach her sibling and her friends, which was equally difficult for a different reason, as the Anomaly entrance was deep under water (unlike Bellamy, she wouldn’t have actually able to leave the planet as she didn’t have a Conductor or codes for the Stone - but she didn’t know she needed them) - for 6 years, before she eventually gave up and settled for her peaceful life for the next 4 years and sending Bellamy a letter.

Hesperides - Like Bellamy, Echo, Gabriel and Hope wanted to get off the planet and reach their friends/family, but unlike Bellamy, they couldn’t get the codes and had to wait for 5 years, and, unlike him, they lived in lovely place. Like Bellamy, they had a devout Disciple as a companion, but there were three of them, which made it more difficult for him to indoctrinate them, no matter how much he wanted to make them Disciples, and they were the ones trying to manipulate him. They developed a friendship with him, as Bellamy did with Doucette, but while Bellamy saved Doucette when he didn’t have to anymore, Echo betrayed him and left him as expendable, and the other two eventually went along with it.

But Etherea is not just another planet for the Disciples - it is notable for what can be found in a cave on the way to the top of the mountain, which Cadogan apparently looked for and found, as a part of his pilgrimage - his own “40 days in a desert” - because, of course, he sees himself as a messiah (and, as we saw in 7x09, this is an important thing in the Bardo religion and something children are taught about in school).

Bellamy immediately learns all about Cadogan’s teachings - everything the rest of the characters took several episodes to learn about - by reading his book (”pocket propaganda from another false god”) and immediately pokes holes in it. He makes all the good points and lists most of the reasons why the Disciple faith makes no sense, including the fact that it makes no sense to be fighting for peace and end of violence by waging another war. Everything he says in the first half of the episode are things I would completely agree with. Which makes it all the more frustrating when he starts ignoring his own reasonable arguments by the end of this episode. One might say that the Disciple propaganda attacks both his heart - using his desire to find peace, an end to all the struggle and pain, and eventually, his love and memory of his mother, to ignore what his head is telling him - but they also eventually attack his head, by presenting what seems like actual physical evidence, and the end result is to ignore not just the rational objections he had, but also try to suppress his love for the most important individual people in his life.

He lists the people he loves - “Octavia, Echo, Clarke” - which is the first time Bellamy himself has used the word love for the latter two (and in fact, for anyone other than Octavia). BTW, notice that no one in the show has ever used the word “girlfriend/boyfriend” except Diyoza (when this was what she assumed Clarke was to Bellamy)? Maybe these words have fallen out of use in the post-apocalypse societies. The main characters usually talk about their “friends” or “family” (the latter not always being biological). Doucette later talks of "your family, your friends” and “your obsession with your sister and your friends” - where Echo and Clarke are both lumped into this category. Echo is not singled out as “your girlfriend” or in any other way.

Here’s the thing about Bellamy’s and Doucette’s dynamic: if this story wasn’t really about indoctrinating Bellamy, there really wouldn’t be anything there we didn’t know about Bellamy before. Of course he wouldn’t kill this random Disciple guy if he didn’t have to - and, in spite of what he tells Doucette at the start, it’s not just because he needed him to survive. Bellamy learning to see the humanity of his enemies and working with them and bonding with them is something we have seen many times: at first with Clarke, then with Lincoln, Indra, the Grounders, Kane, Echo. All the way back in season 2, he valued human lives, even from the enemy side: he opposed Murphy’s idea of killing the captive Grounder thief (while Finn summarily killed him), he angrily said he’d kill everyone in Mount Weather but then tried his best for that not to happen, after seeing the children there; even during his Pike-supporting days, he tried to persuade Pike and the others to spare the wounded Grounder warriors, in season 4 he talked Riley down from trying to assassinate Roan, and in season 5, he refused to kill the cryo frozen Eligius prisoners, and later convinced Madi to spare the Eligius convicts who were their PoW. And while Bellamy has been motivated, most of all, by personal love (particularly for his sister and Clarke), we’ve seen him save many people, including strangers or near strangers. That speech Doucette gave him about “loving all mankind” is something season 1 Bellamy needed to hear, the one who was focused just on Octavia and then just on her and the Delinquents, but Bellamy has had a massive character development since. Bellamy knows more about loving all mankind than Doucette or any of the Disciples do. Doucette says he “loves all mankind” including a total stranger - well, dude, didn’t you try to kill Bellamy at first? And the rest of what we’ve seen from Disciples is much worse. They talked the talk, but don’t walk the walk, unless they think kidnapping and torturing people and trying to break their spirit is “love”, And Anders definitely showed that he did not “love all the mankind” when he ordered a hit on Hope, or when he gave that speech in 7x10 about what disgusting “wild beats” all these non-Disciples were.

But unlike Anders, Doucette can talk in a convincing way and make decent arguments in favor of his faith to non-believers, rather than just preaching to the converted - or at least, he can appear to give decent arguments. He’s taking a page from The 100 fandom with the argument that Bellamy is so selfish and egotistical for... loving his sister and his friends and constantly fighting and sacrificing himself for them. (The 100 fandom loves making that same argument about Clarke.) Quite a skill, to make such BS argument sound convincing. He basically gives Bellamy a version of the “Love is weakness” advice - in this case, that “love is selfish” and leads to destruction and pain. And when Bellamy asks the rhetorical question, if that means that you shouldn’t love anyone - Doucette turns it around and talks of love for all mankind. But that “love” he speaks of is abstract and fake - it is impossible to love everyone. You cannot love total strangers, or people you simply don’t like - certainly not the same as you love your lover or friend or family member. You can, however, be compassionate, and value human lives,.Which is, in fact, something the Disciples don’t do, as we’ve seen on Bardo (but Bellamy has not seen it yet) - they just value lives as more soldiers for the cause. Their “humanity” is abstract - they are ready to sacrifice individuals for it (everyone except the Shepherd). Bellamy, on the other hand, has always been about valuing individual lives and saving them - be it Mel on season 2, or the slaves in season - and he managed to do it while also loving his sister and his friends. The Disciples and Doucette’s arguments present a false dichotomy. But, unfortunately, Bellamy still has deep guilt and self-loathing that he never fully resolved (even in season 6, he still talked about his many sins in 6x04), and he’s tired by always having to fight another war for survival, just to followed by another. (Which is similar to Clarke’s misgivings in 7x03: “I’m afraid that fighting is not what we do, it’s what we are” and Raven’s and Clarke’s conversation about guilt over having killed so many people.) The only time he didn’t have to always worry and/or fight were the years on the Ring, but he was still grieving Clarke and missing Octavia and motivated by going back down to reunite with her He knows what he’s capable of doing out of love - and he also has unresolved issues with the women he loves. In season 4, he lamented how pathetic he was coming back to his sister when she kept treating him badly, and in the 7x07 Ring flashback, he thought his love for his sister was his “weakness”. He’s certainly been hurt by her, finally rejected her and then later got to reunite with her, get an apology and forgive and make up with her. He and Clarke have also certainly hurt each other and forgiven each other, and that relationship is still unresolved. Bellamy himself admitted to Jo!Clarke in 6x09 that he was exhausted by their ups and downs and lack of resolution. And Echo... well, he should know exactly where he stands with her, but he didn’t seem happy about their relationship and seemed to want her to be Clarke someone else.

I can see why Bellamy started to envy Doucette his emotional calm that his faith and worldview seemed to bring him.

We got another Pike mention in this ep (and again, it was a reference to his positive role - as a teacher of Earth skills). The last time Bellamy made it was in 6x07 when he found out Clarke was alive. Pike was also a father figure to Bellamy - just like Kane, and now Cadogan. Bellamy has been called both a King and a Knight. Some of his biggest mistakes were when he chose to trust in a leader/father figure (the last time, it was Pike - who was, however, very different from Cadogan and his views on the opposite side the spectrum from Bill’s), and ALIE!Raven thought that one of the ways she could try to taunt him and erode his confidence was to call him a follower rather than a leader. Only she tried to convince him that he was in subjugated position to Clarke - which IMO was never true. They have always had an equal relationship (except when external circumstances made it otherwise - see, Kane and the adults taking the power away from Bellamy, while Clarke was able to take it back from Abby mostly because she was backed up by the Grounder Commander), and Clarke was the one who always tried to boost Bellamy’s confidence in his abilities as a leader. He was definitely a leader of his people in season 5 and season 6, and he works best as co-leader with Clarke (and vice versa). But even when Bellamy supported Clarke, he was questioning his decisions, even though he was rarely able to change Pike’s mind - he wasn’t blindly obeying and accepting everything, as he would have to with the Disciples.

Another factor in Bellamy’s transformation is of course the fact that he spent months in the cave - to the point of physical and mental exhaustion. Every time he and Doucette would climb the mountain, the peak where the Stone was would turn out to be even higher. Bellamy himself used two of the Greek myths to describe the task - Sisyphus and Icarus. A pointless task that results in having to do everything all over again (just like what he said about having to always fight another war), and a dangerous task likely to destroy you.

Bellamy was still insisting on reason over faith - “I believe in what I can prove” - but then he got to see the beings of light, as “proof”..

And here we come to the more interesting part of this ep and something that the show may or may not explain. I’m pretty skeptical about Cadogan’s views of what these beings are. How do we know that they have really “transcended” and become eternal or whatever, living on some kind of higher plane? No one has communicated with them, or have they? They are aliens, from our POV. Maybe that’s their natural state? Maybe they’re dead and this is just what remains of them? Maybe they died in a similar catastrophe as the Bardoans but one that was more about fire than ice, as Selina hypothesized in her review)? Maybe they are in agony? Sure, they look beautiful to human eyes, and fit the human culture’s idea of what spirituality and transcendence is like - but you can’t know that for sure. The frozen crystal giants on Bardo also look beautiful, after all, and that entire species died horribly

And then the second “otherworldly” thing happens after Bellamy finally agreed to prey - and he has a vision, involving Cadogan as his spiritual guide, leading him from a place full of weapons - swords and guns - to the place where he sees his dead mother, Aurora. It’s a beautiful and emotional scene, and I can’t imagine all the things Bellamy is feeling as she touches his face - including, probably, more unresolved guilt - over getting his mother executed (because he loved his sister and tried to make her happy). Aurora tells him Go to the light, Bellamy” and he looks at the figures of light - but we don’t learn what, if anything, he saw there .

I hope we learn that Bellamy saw something important - maybe something connected to the Judgment Day Becca talked about - that would explain the extent of his conversion, although it seems that it is mostly supposed to be a consequence of the fact that the storm stopped at the moment when he chose to prey.

The final step in his ‘spiritual journey’ is after that, when he barely managed to reach the top. After repeating the mantra “I am not afraid” (something else from the Blakes’ childhood - the same line Octavia was repeating on Bardo to resist the Conductors), he admits to himself “I am afraid”. In retrospect, a sign that he was broken, and started feeling that his past and his family were not enough to give him strength and faith. The jump from the top was described as a “leap of faith” by Doucette - which is kind of ridiculous, since it had nothing to do with faith, just with the fact that Cadogan was there and knew how the Anomaly worked, and the fact he was able to climb the mountain and leave is proof that the Anomaly worked properly.

(I wonder why the heck the Anomaly works so differently on different planets - in some cases you can enter the Anomaly right next to the Stone when you’re leaving the planet, and in others, you have to go back to the original entrance that’s somewhere else.)

Now, the visions may be explained in several different ways:

hallucinations - earlier, Bellamy found a family photo and recognized Cadogan, and he would know how Conductors and high ranking Disciples dress, he’s seen the white robe on Anders and Doucette

everything in the cave is real, and Cadogan has some sort of a telepathic connection to the cave (the true believer’s interpretation)

the brain implant/hive mind theory (by Selina again - I don’t believe in this one as there has been no evidence of it so far)

projections/hologram - see Jean’s theory that Cadogan used the hologram technology to project images of himself and Aurora (whose image is familiar to the Disciples from Octavia’s memories)

a combination of some of the above - the beings of light may be real, and Cadogan may have stumbled onto something but has again misinterpreted what it was all about; Bellamy’s vision of Cadogan was a hallucination or projection, but he also did see something real when his mother (again, possible hallucination or unexplained spiritual phenomenon) told him to look into the light.

It’s possible that the show will never fully explain what really happened here, just as Murphy’s vision of hell has never been explained.

The reunion

Up until this point, the episode doesn’t seem to show a seriously disturbing turn in Bellamy: we saw that he was starting to take the Disciples’ faith seriously and even to believe in it, and the first thing he does when turning up in the Stone Room on Bardo is look happy and relieved he made it, and hug an equally happy Doucette. So, he made a friend among the Disciples and will be the one telling Clarke and the rest: “We should take this seriously, they have a point, here is what I saw on Etherea...” - right? That would make perfect sense while not fundamentally changing who Bellamy is.

But no! Bellamy falls to his knees and calls Cadogan “My Shepherd” - which was one of the most painful scenes for me to see in all of the show, even more so than the later scene where he snitches on Clarke. There’s been a lot this season about “kings” forcing subjects to kneel - but instead of the “kneel or die” approach that Anders more or less used (while Sheidheda is using it in the most literal way possible), this is out of genuine belief. I don’t know if I’m really buying this massive transformation that we see here and in the next scene. It’s just a bit too much. Maybe information about what it was that Belalmy saw when he went ‘into the light’ would help explain it better.

Cadogan is happy to use Bellamy to convince Clarke to cooperate, and informs him: “Your friends are here, they have gotten themselves in some trouble”. Maybe this adds up to the reason why Bellamy is uncomfortable when he sees them a bit later, because they’ve been bad - but only some of them were (Echo with her murders, torture and genocide attempt, the others - not really, except Hope, someone he doesn’t even know yet). But when he comes to see them, he looks broken, exhausted and numb after all his experiences. And probably wary of giving in to the “selfish love”. (His friendship with Doucette is presumably in line with his new faith, but he seems to think his friendship with Clarke is not? Is that his relationship with Clarke actually involves love, real love for an individual?) After finally reuniting with the people he had been trying to reach all that time on Etherea, he doesn’t even look happy to see them. To quote Bellamy from earlier in the episode,Sometimes, Bellamy Blake, irony is funny. This is not one of these times.

Meanwhile, his friends are in Cadogan’s living quarters in house arrest. Conveniently, it’s just Clarke, Echo and Octavia there - plus Gabriel, but the focus is on Bellamy’s reunions with the three women he named as the people he loved earlier in the episode. Raven is not there, neither are Miller, Jordan, Niylah or Hope. (The last time Bellamy saw Jordan, Jordan was the brainwashed one. Hey, what happened to that storyline? Did it end up as a casualty of the rewrites?)

They’re discussing what to do, and Clarke has decided to basically sacrifice her life so the others could escape. We know that Clarke is a very selfless person, but the way she’s been increasingly casually deciding to sacrifice herself feels a bit disturbing - as if she’s stopped caring about her own life or hoping for happiness. At this point, her big character development would be to choose happiness and try to have what she wants. Even her “selfish” actions up to this point were mostly about trying to protect others. We haven’t even seen her show much emotion this season - as if she was on autopilot - except for her early grieving Abby earlier in the season, and moments when she’s silently grieving Bellamy,

Cadogan is there to offer the carrot rather than the stick, and being a drama queen, doesn’t Clarke and the others that Bellamy is there, but lets him in. They are massively surprised but don’t notice something’s off, or rather, they seem to assume he is just physically exhausted and in pain rather than mentally/emotionally off, as he silently looks at Clarke and Octavia and then Echo. Camera shows close-ups of the reactions of the people who love him: Clarke’s, Echo’s and Octavia’s reactions before going back to Clarke. (Probably because she’s the main character, in case people have forgotten, and her relationship with Bellamy is at center of the show), Octavia is happy and proud tries to hug her brother, but the Disciples pull out weapons. Clarke ignores the weapons, counting on her status/leverage, and hugs him.

She looks lovingly at him, with something we haven’t seen from her in a long time - happiness, that’s definitely not “best friend that I’m not attracted to” but “best friend I have naughty thoughts about”. (Only love can make you hug someone who must be smelling really badly at this point, considering Bellamy hasn’t washed or changed his clothes in over 3 months!)

This hug is different from any other Bellarke hug ever, since Bellamy is so numb, even when he hugs her back, but she is too happy to see him back to notice. And then when she takes the chance to also get him up to speed and tell him about the Flame - he gets an incredibly sad look on his face. He is not unemotional now - but he has decided he must ignore and suppress those feelings, betray her trust and tell Cadogan the truth, because his faith and the so-called “love for all mankind” comes first.

Everyone is shocked when he calls Cadogan “My Shepherd” and then beyond shocked when he betrays them - and camera again shows Echo’s, Octavia’s and Clarke’s reactions, going back to Cadogan, and then the episode ends on a close-up of Clarke’s shocked face. Because, you know, she’s still the main character. And finally, now we can hopefully have a S7 storyline that properly focuses on the show’s protagonist and utilizes Eliza’s talent allowing her to show a range of emotions. When Clarke believed Bellamy was dead, he was someone she could hold in her memory and try to honor it by saving his sister and girlfriend - but this is a whole new way of losing him, right after thinking she got him back, and means real emotional turmoil.

Bellamy has become a true believer and decided to stop being himself. And the people who love him will now have to deal with his loss - in another way - all over again, and try to save him. I’m torn because this storyline offers huge opportunities for a “power of love” storyline right out of a fanfic, but I’m uncomfortable with the idea that it may come at the expense of having Bellamy be manipulated and subjugated to a white megalomaniac villain in the last season. But I hope and expect we will see genuine character development and re-affirmation of who Bellamy Blake is. Now, there are a lot of things Bellamy doesn’t know yet and that have contributed to him drinking Cadogan’s Kool-Aid (he hasn’t seen Cadogan’s dealings with his family or Second Dawn, or what he did to Becca, or Anders’ actions on Bardo, or the way the Disciples mistreat their own people, and he doesn’t know about Cadogan’s mistranslation of the Bardoan text), but I don’t think the resolution of this storyline will be about Cadogan or what Bellamy knows about his religion. I think it will be Bellamy himself and his relationships. Clarke and Octavia had big character arcs in season 5-6 where they had to deal with who they are, who they’ve become and what they want to be negating everything he is. He needs to finally really deal with his self-loathing and guilt and he needs to gain back trust in himself, the Bellamy Blake that others loved and trusted and relied on. He needs to feel loved and decide that love is strength and a positive rather than just ‘selfish’ force. (And who can show him that? Hint: not his girlfriend Echo, whose love he would definitely see as confirmation that love is selfish and destructive, as it makes a person do things like murder, torture and attempted genocide out of revenge. Another hint: probably the same person who gave him confidence and made him believe in himself and grow as a person, multiple times, all the way back in season 1 and again in season 3 and season 4, telling him he was a person that other follow because of his big heart and the way he can inspire people. And third hint - the same person Bellamy was saving - her physical self - in season 6, will be the one who’ll have to save him, mentally, save who he is., in season 7.)

Rating: 8/10 (could go higher or lower depending on how the cave visions are explained and what the outcome of this plot is)

#the 100#etherea#the 100 7x11#bellamy blake#clarke griffin#bill cadogan#octavia blake#the disciples#the anomaly#bardo

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

What if The Raven Boys are in Divergent Series?

I was thinking here, what if the characters from The Raven Boys was characters from Divergent series? What faction they would be? I've posted it in my twitter, but I bring it here too.

Blue Sargent — Candor (the honest)

"everyone will trust you. your sincerity will not have limits."

Richard Gansey III — Erudite (the inteligent)

"the search for knowledge will guide your life."

Adam Parrish — Abnegation (the selfless)

"forget yourself. the others will be your priority."

Ronan Lynch — Dauntless (the brave)

"protect the city against enemies, tirelessly and unafraid."

Noah Czerny — Abnegation (the selfless)

"forget yourself. the others will be your priority."

Henry Cheng — Candor (the honest)

"everyone will trust you. your sincerity will not have limits."

BONUS

Adam Parrish — divergent (because i think he could be both abnegation and erudite)

"you tend to deviate from the norm. you will not accept what is imposed and will be part of more factions."

#the raven cycle#the raven boys#what if#blue sargent#adam parrish#ronan lynch#richard gansey#noah czerny#henry cheng#books#what if book#book#book meme#divergent#divergent books#divergent series

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I added onto my divergent au,,,

➡ jeremiah heere // abnegation

"Don't feel bad, she didn't stick around anyway."

➡ michael mell // erudite

"We're seriously gonna make our own bombs?"

➡ jakob dillinger // amity

"I mean, yeah, dogs are cool."

➡ chloe valentine // candor

"Surprise, surprise! I'm not always yes or no."

➡ brooke lohst // amity

"Fuck you, asshole!"

➡ richard goranski // dauntless

"There's more where that came from!"

➡ christine canigula // candor

"Not everyone has a dark backstory, ya know."

➡ jenna rolan // erudite

"Smile for the camera!"

➡ squip // abnegation-erudite

"Good luck."

#divergent#divergent au#au#bmc au#bmc#bmc musical#bmc edit#be more chill au#be more chill#jeremy heere#jake dillinger#jenna rolan#christine canigula#chloe valentine#rich goranski#boyf riends#squip#bmc divergent au#💛

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Crowd Doesn’t Just Roar, It Thinks: Warner Bros.’ All-Talking Revolution

“Iconic” is a gassy word for a masterwork of unquestioned approval. But it also describes compositions that actually resemble icons in their form and function, “stiff” by inviolate standards embodied in, say, Howard Hawks characters moving fluidly in and out of the frame. Whenever I watch William A. Wellman’s 1933 talkie Wild Boys of the Road, these standards—themselves rigid and unhelpful to understanding—fall away. An entire canonical order based on naturalism withers.

To summon reality vivid enough for the 1930s—during which 250,000 minors left home in hopeless pursuit of the job that wasn’t—Wellman inserts whispering quietude between explosions, cesuras that seem to last aeons. The film’s gestating silences dominate the rather intrusive New Deal evangelism imposed by executive order from the studio. Amid Warner Bros.’ ballyhooing of a freshly-minted American president, they were unconsciously embracing the wrecking-ball approach to a failed capitalist system. That is, when talkies dream, FDR don’t rate. However, Marxist revolution finds its American icon in Wild Boys’ sixteen-year-old actor Frankie Darro, whose cap becomes a rude little halo, a diminutive lad goaded into class war by a chance encounter with a homeless man.

“You got an army, ain’t ya?” In the split second before Darro’s “Tommy” realizes the import of these words, the Great Depression flashes before his eyes, and ours. No conspicuous montage—just a fixed image of pain. Until suddenly a collective lurch transmutes job-seeking kids into a polity that knows the enemy’s various guises: railroad detectives, police, galled citizens nosing out scapegoats. Wellman’s crowd scenes are, in effect, tableaux congealing into lucent versions of the real thing. The miracle he performs is a painterly one: he abstracts and pares down in order to create realism.

Wellman has a way of organizing people into palpable units, expressing one big emotional truth, then detonating all that potential energy. In his assured directorial hands, Wild Boys of the Road sustains powerful rhythmic flux. And yet, other abstractions, the kind life throws at us willy-nilly, only make sense if we trust our instinctive hunches (David Lynch says typically brilliant, and typically cryptic, things on this subject).

I’m thinking of iconography that invites associations beyond familiar theories, which, in one way or another, try to give movies syntax and rely too heavily on literary ideas like “authorship.” Nobody can corner the market on semantic icons and run up the price. My favorite hot second in Wild Boys of the Road is when young Sidney Miller spits “Chazzer!” (“Pig!”) at a cop. Even the industrial majesty of Warner Bros. will never monopolize chutzpah. The studio does, however, vaunt its own version of socialism, whether consciously or not, in concrete cinematic terms: here, the crowd becomes dramaturgy, a conscious and ethical mass pushing itself into the foreground of working-class poetics. The crowd doesn’t just roar, it thinks. Miller’s volcanic cri de coeur erupts from the collective understanding that capitalism’s gendarmes are out to get us.

Wellman’s Heroes for Sale, hitting screens the same year as Wild Boys, 1933, further advances an endless catalogue of meaning for which no words yet exist. We’re left (fumblingly and woefully after the fact) to describe a rupture. Has the studio system gone stark raving bananas?! Once again, the film’s ostensible agenda is to promote Roosevelt’s economic plan; and, once again, a radical alternative rears its head.

Wellman’s aesthetic constitutes a Dramaturgy of the Crowd. His compositions couldn’t be simpler. I’m reminded of the “grape cluster” method used by anonymous Medieval artists, in which the heads of individual figures seem to emerge from a single shared body, a highly simplified and spiritual mode of constructing space that Arnold Hauser attributes to less bourgeoise societies.

If the mythos of FDR, the man who transformed capitalism, is just that, a story we Americans tell ourselves, then Heroes for Sale represents another kind of storytelling: one firmly rooted to the soiled experience of the period. Amid portrayals of a nation on the skids—thuggish cops, corrupt bankers, and bone-weary war vets (slogging through more rain and mud than they’d ever encountered on the battlefield)—one rather pointed reference to America’s New Deal drags itself from out of the grime. “It’s just common horse sense,” claims a small voice. Will national leadership ever find another spokesman as convincing as the great Richard Barthelmess, that half-whispered deadpan amplified by a fledgling technology, the Vitaphone? After enduring shrapnel to the spine, dependency on morphine, plus a prison stretch, his character Tom Holmes channels the country’s pain; and his catalog of personal miseries—including the sudden death of his young wife—qualifies him as the voice of wisdom when he explains, “It takes more than one sock in the jaw to lick 120 million people.” How did Barthelmess—owner of the flattest murmur in Talking Pictures, a far distance from the gilded oratory of Franklin Roosevelt, manage to sell this shiny chunk of New Deal propaganda?

How did he take the film’s almost-crass reduction of America’s economic cataclysm, that metaphorical sock on the jaw, and make it sound reasonable? Barthelmess was 37 when he made Heroes for Sale; an aging juvenile who less than a decade earlier had been one of Hollywood’s biggest box-office titans. But no matter how smoothly he seemed to have survived the transition, his would always be a screen presence more redolent of the just-passed Silent-era than the strange new world of synchronized sound. And yet, through a delivery rich with nuance for generous listeners and a glum piquancy for everyone else, deeply informed by an awareness of his own fading stardom, his slightly unsettling air of a man jousting with ghosts lends tremendous force to the New Deal line. It echoes and resolves itself in the viewer’s consciousness precisely because it is so eerily plainspoken, as if by some half-grinning somnambulist ordering a ham on rye. Through it we are in the presence of a living compound myth, a crisp monotone that brims with vacillating waves of hope and despair.

Tom is “The Dirty Thirties.” A symbolic figure looming bigger than government promises, towering over Capitalism itself, he’s reduced to just another soldier-cum-hobo by the film’s final reel, having relinquished a small fortune to feed thousands before inevitably going “on the bum.” If he emits wretchedness and self-abnegation, it’s because Tom was originally intended to be an overt stand-in for Jesus Christ—a not-so-gentle savior who attends I.W.W. meetings and participates in the Bonus March, even hurling a riotous brick at the police. These strident scenes, along with “heretical” references to the Nazarene, were ultimately dropped; and yet the explosive political messages remain.

More than anything, these key works in the filmography of William A. Wellman present their viewers with competing visions of freedom; a choice, if you will. One can best be described as a fanciful, yet highly addictive dream of personal comfort — the American Century's corrupted fantasy of escape from toil, tranquility, and a material luxury handed down from the then-dying principalities of Western Europe — on gaudy, if still wondrous, display within the vast corpus of Hollywood's Great Depression wish-list movies. The other is rarely acknowledged, let alone essayed, in American Cinema. There are, as always, reasons for this. It is elusive and ever-inspiring; too primal to be called revolutionary. It is a vision of existential freedom made flesh; being unmoored without being alienated; the idea of personal liberation, not as license to indulge, but as a passport to enter the unending, collective struggle to remake human society into a society fit for human beings.

In one of the boldest examples of this period in American film, the latter vision would manifest itself as a morality play populated by kings and queens of the Commonweal— a creature of the Tammany wilderness, an anarchist nurse, and a gaggle of feral street punks (Dead End Kids before there was a 'Dead End'). Released on June 24, 1933, Archie L. Mayo's The Mayor of Hell stood, not as a standard entry in Warner Bros.’ Social Consciousness ledger, but as an untamed rejoinder to cratering national grief.

by Daniel Riccuito

Special thanks to R.J. Lambert

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The court case Australians are not allowed to know about: how national security is being used to bully citizens | Richard Ackland https://buff.ly/2K0bcdu⠀ ⠀ In the Witness K case, a closed court is also very useful in covering up the alleged wrongdoing of a previous Coalition government⠀ ⠀ Here is a case where we find national security is being played as a card to bully citizens, cast them in the role of “terrorists” and cover-up the wrongdoing of a previous Coalition government, of which the current attorney general is in a direct line of succession...⠀ ⠀ Can a secret trial, where evidence is suppressed, be a fair trial? It could be that the moment justice Mossop rules that slabs of the proceedings be closed, then the accused would be off to the High Court seeking a ruling that secrecy is an abnegation of fairness.⠀ ⠀ The attorney general wanted speed and silence; instead, he will get a case that has the potential to run on and on, accompanied by mounting public disgust. https://www.instagram.com/p/B-5D5LWhI6u/?igshid=c73ipvb0jv61

1 note

·

View note

Quote

The big difference, however, between religious worship and novel-reading is that immortals are the object of adoration or self-abnegating love or fearful obedience, rather than people in whose shoes we are trying to put ourselves.

Richard Rorty

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Donald Trump is a Heretic from the Left’s Secular Religion

Donald Trump is a heretic. He is persecuted by the Church.

No, not any of the Christian Churches. For them, although few realize or will admit it, Donald Trump, the famous playboy womanizer, is the most pro-Christian President in recent memory. Trump is a heretic from the Leftist church, the secular religion of today’s political and media elites, and as such he must be treated as heretics were in the old days of the Spanish Inquisition: he must be burned at the stake. Actually, that’s inaccurate, as archaism is frowned upon by this religion’s clergy. He need not be burned at the stake, but by whatever means, he must be destroyed.

Although most people in the United States today still identify themselves as Christians, the dominant religion of those who have dominated the political arena, own the establishment media, and set the cultural tone for the nation is not Christianity, but Leftism.

Leftism is a religion without a being who is identified as god as such, except insofar as the atomized individual is exalted to deity status and its every whim canonized as tantamount to divine writ, but it is as rigidly dogmatic, as fervently held, and as fanatically divorced from rationality as the worst and most destructive religious manifestations in human history. It is also extremely influential and all-pervasive. Every President since Franklin D. Roosevelt, with two notable exceptions, has held to this religion to varying degrees, and in some way paid obeisance to its gods and made offerings at its altars.

The first exception was Ronald Reagan. Richard Nixon was virulently hated by the high priests of Leftism, almost as much as Trump is now, but as President, instead of fighting them, Nixon endeavored in numerous ways to show that he was as good a Leftist as those who were determined to drive him from office and destroy him. They were, obviously, not appeased. As is shown in the forthcoming Rating America’s Presidents: An America-First Look at Who Is Best, Who Is Overrated, and Who Was An Absolute Disaster, it was Reagan who was the first post-FDR President to blaspheme the Leftist religion by refusing to adhere to the Leftist dogma that the best way to deal with the Soviet Union was through the admixture of naïve self-abnegation and suicidal concession known as détente.

But Reagan, too, lit incense at the Leftist altars, opening the floodgates to millions of migrants, including all too many with little understanding of, much less love for, the founding principles of the American Republic, when he signed the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, also known as the Simpson-Mazzoli Act, on November 6, 1986. This act made it unlawful to hire people who had come into the country illegally, but also granted amnesty to virtually all illegal immigrants who had entered before 1982—some three million people.

It was left to Donald Trump to challenge the very religion of Leftism itself. The Leftist religion is fervently internationalist, believing that any and all manifestations of nationalism or patriotism are evil in themselves and a recrudescence of Nazism. Trump, by contrast, has repeatedly declared that as President he puts America first, refusing to be intimidate by ongoing efforts to discredit the America-First slogan, and the imperative behind it, as neofascist or racist. Never-Trump commentator William Kristol enunciated the Leftist dogma when he tweeted: “I’ll be unembarrassedly old-fashioned here: It is profoundly depressing and vulgar to hear an American president proclaim ‘America First.’”

As far as Kristol was concerned, the President of the United States should put the interests of the entire world first. This would involve sending American troops on “humanitarian” missions all over the globe, even when no conceivable American interest was involved. Economically, it would require the United States to tie itself into the global economy, another sacred Leftist dogma that Trump has rejected.

It doesn’t matter to the adherents of the Leftist religion that the coronavirus pandemic has shown why it is unwise to depend on China to manufacture anything that America needs. Their beliefs are not rational. Religious faith can be rational, but it often is not, and the Leftist religion is not rational. It is a set of feelings, and emotions, and manifestations of wishful thinking about the world that can be frankly dangerous when it collides with reality – as the coronavirus showed yet again.

But religious faiths can survive all manner of disconfirming evidence. And so Trump is a heretic, and nothing but a heretic, and as such he is persecuted. As far as Leftists are concerned, he must be destroyed, because if he is not, he will destroy their religion. This will be for them a fight to the death.

Robert Spencer is the director of Jihad Watch and a Shillman Fellow at the David Horowitz Freedom Center. He is author of 19 books, including the New York Times bestsellers The Politically Incorrect Guide to Islam (and the Crusades) and The Truth About Muhammad. His latest book is The Palestinian Delusion: The Catastrophic History of the Middle East Peace Process. Follow him on Twitter here. Like him on Facebook here.

This content was originally published here.

0 notes

Text

richard "pinko" abneg, known commie: Prey is prey, sorry to have to disenchant you two dreamers. You total Communists.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, you wrote in the notes of Tales from the Pit that we could send you prompts on this Tumblr account, so in the event that it would inspire you, here is one. The name changing thing felt really important in the books so maybe you could do something where Tris tells Eric (or someone else, the BFF with Richards in chapter 2 was very nice to read) that if he wants to, he can also call her Béatrice? Because the use of her full name is a gift she allows only to people she feels very close to?

I have some very strong feelings on Tris’ name, some of which you may be able to see with how I worked on this drabble. I don’t fault people who like letting Tris have that sort of connection with her friends by way of her full name. I just tend to see it less as “Tris is a nickname for her full name” and more as “Tris is her identity in Dauntless and Beatrice was her identity in Abnegation.” I enjoy Tris as a Dauntless rather than a renegade Divergent causing trouble and drop-kicking the system, so I like her as Tris, full stop.

So, in an attempt to balance those feelings and still fulfill the prompt idea, please enjoy!

A Transfer by Any Other Name

I chewed on a bit of jerky as I scrolled through the list of Initiates this year. It had fallen on my shoulders as the newest in the office and therefore lowest on the totem pole. I had to file all the appropriate paperwork for our newest tentative members, and I began to understand why Eric complained about it.

Medical files had been forwarded to our office at random intervals. Some included previous family histories making the computer in my office whir painfully loudly as it downloaded every byte. Two had come by courier in paper form, forcing me to transcribe them over digitally. Still others were single files with a birth date and some innoculations listed alphabetically without any other date listed. It was my responsibility to take all of this information and file it away with our new Initiates.

What made it even more complicated was the fact that everything I received was by prior name. Part of my job was to also reassign files to the initiate’s new name - if they’d taken one. Annabelle Williams now went by the far less farm-girl sounding Anne Wills. Craig Jetson got rid of his entire first name and had decided to be called Jet. There was a whole separate form for those who were forgoing a family name, for the sake of maintaining the family record. One that I was entirely out of.

I rolled my chair out from the bullpen to coast up to Kyle’s desk. “How’s my favorite ex-officemate?” I asked. Now that I was out of training, ironically I lost the tiny scrap of office space that I and the other trainee’s had shared with him. Not that any of them had used the space anyways, but that was probably their own fault for not taking advantage of an actual door that shut.

The dark haired secretary twisted his head to look at me. “I don’t have any more of those soft caramels, so you can stop that right off, Prior” he drawled.

“Ouch,” I breathed, pressing a hand over my heart. “I’m Prior today? Not even Tris?”

“You’re doing paperwork which means in about three hours I’m going to be doing paperwork auditing,” he sighed. “That makes you Prior today. Especially since it’s shitty Candor legal-ese papers.”

He had me there. “I would offer to help-” I started to say, but he’d already started waving the suggestion away. “I know, I know. It’s auditing and you can’t audit yourself.”

“Get your pretty blonde boyfriend to help and maybe you can be Tris again,” Kyle teased.

I leaned on his desk and tipped my head to mirror how his was propped on one palm. “If I get him to do the auditing instead of you, can I be Beatrice?”

Kyle blinked twice in rapid succession. “Why would you want to be an old Abnegation grandmother?”

“That’s my name. Beatrice. Tris is just a nickname,” I answered. “I just… People I’m close to can call me that without it being weird? I thought I’d told Rich awhile ago. Figured he would have mentioned it by now.” I’d thrown him off of his game. Normally that would have made me crack a smile in pride. Something in how his eyes were darting over my face now unsettled me.

I asked for the name change form I needed and rolled away before he had the chance to be any weirder. The nagging feeling stuck in the back of my head any time that I looked up from my work for a break.

Staring at Jet’s paperwork made me realize something that I hadn’t considered before. What was my name, according to Dauntless’ records? Was I still Beatrice Prior, like I’d thought?

A few clicks in the program I was logged into brought me out of this year’s initiate directory. The folder from two years earlier held my initiate class. I scrolled past Al’s files as quickly as possible in an effort to keep the tall boy in my head where he belonged. My name didn’t crop up next, and it wasn’t until I’d passed Peter that I spotted my name.

Tris Prior.

My stomach flipped slightly. Seeing it there in green text was more impactful than hearing it every day. I drew up a new name change form and began to fill in the lines with my information.

My hand stilled as I hovered over the NEW NAME line. Ink welled at the tip of my pen, threatening to stain the page. Four had said back on the day of the Choosing ceremony that if I changed my name, it would be my only chance. It wasn’t true; I was holding the evidence in my hand now.

Drip.

I had said Tris and it hadn’t been the impulsive decision made in a rush of endorphins. I’d chewed over what it would be like to walk away from an Abnegation name like Beatrice before to drive back the slow boredom of service work.

Drip.

It was reflexive to respond to Tris now, to embrace the girl that I’d decided on being when I fell down that pit.

Drip-drip.

The line was ruined, ink running in chaotic patterns as it soaked into the fibers of the paper. I chucked the busted pen into the garbage. Next came the form, folded into quarters to be slid into paper recycling.

Later, when I was tucked under Eric’s arm and sitting on Richards’ couch, I found another spot of ink on my hand. I rubbed at it fruitlessly before sighing. “Hey Tris?” Kyle called from behind me. “Can I get a hand bringing in this cooler? My arms are about to fall off.”

I wriggled out from under my boyfriend’s arm, a smile back on my face. “So I’m back to Tris?” I teased. The cooler was stuck in the doorway as Kyle tried to fit himself and the plastic behemoth in at the same time. He rolled his eyes and nearly dropped the cooler on me.

“Keep it up or you’ll be down to ‘hey blonde girl,’” he groaned. It was an empty threat and I laughed instead.

“As long as it’s not Grandma, I’ll be OK,” I said, hefting the cooler on top of their small kitchenette table.

Kyle threw himself onto a chair, his arms dangling comicly. “Can Gramma Bea get me a beer?”

I dug through the ice to find the stout that he drank. He popped it open on the edge of the table. We’d had conversations about how that would never happen on my furniture, but I had no control over how he treated his own stuff. “I actually thought about it,” I said quietly. “Looking it up, I saw that I was already in the system as Tris. And I was going to change my name back to Beatrice. But I couldn’t do it. I’d rather leave that name in the past, with my family.”

He paused partway through a long draw to study me once more. Then, he nodded, apparently satisfied with what he saw this time. “Good,” he grunted. “But I’ll miss the new nickname ammunition. I already had a plan for a bit of black and yellow modelling clay to cover your desk in tiny bees.”

#askbox distractions#drabble#Tris Prior#lyssore#sarah replies#divergent#Eris#Eric Coulter#OTP: Who let you out#I mean the Eris is like *if you squint* eris but its there

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shakespeare Quotes From This Semester

So in one of my classes this semester, as it was Shakespeare class centered around his Histories and Comedies, we had to learn and recite 8 lines from each play. I completely botched my first one, it was so embarrassing, I had to pause and curse and laugh throughout it. After that initial atrocity, I got much better and now want to document the passages which I have committed to memory.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream: Act I Scene I Lines 233-241 Things base and vile, folding no quantity, Love can transpose to form and dignity: Love looks not with the eyes, but with the mind; And therefore is wing'd Cupid painted blind: Nor hath Love's mind of any judgement taste; Wings and no eyes figure unheedy haste: And therefore is Love said to be a child, Because in choice he is so oft beguiled.

- Helena about her unrequited love for Demetrius who is in love with Hermia

Much Ado About Nothing: Act IV Scene I Lines 169- 177

To start into her face, a thousand innocent shames In angel whiteness beat away those blushes; And in her eye there hath appear'd a fire, To burn the errors that these princes hold Against her maiden truth. Call me a fool; Trust not my reading nor my observations, Which with experimental seal doth warrant The tenor of my book

- the Friar to Hero after Claudio and his bois @ her saying she isn’t virtuous bc they fell for an idiot set-up by Don Jon

The Merchant of Venice : Act III Scene 1 Lines 62-70

I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes? hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer, as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? if you tickle us, do we not laugh? if you poison us, do we not die? and if you wrong us, shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that

- Shylock after finding out that his daughter, Jessica, has eloped with a Christian, took all of his money and goods, and also defending his push for Antonio to secure his bond.

Richard II: Act III Scene II Lines 160-168

All murder'd: for within the hollow crown That rounds the mortal temples of a king Keeps Death his court and there the antic sits, Scoffing his state and grinning at his pomp, Allowing him a breath, a little scene, To monarchize, be fear'd and kill with looks, Infusing him with self and vain conceit, As if this flesh which walls about our life, Were brass impregnable, and humour'd thus

- Richard II when abnegating the throne to Henry IV and making the worlds biggest scene of it because he is the most dramatic boi to ever sit his fanny on that English throne

Henry IV (Part 1): Act I Scene I Lines 77-85

Yea, there thou makest me sad and makest me sin In envy that my Lord Northumberland Should be the father to so blest a son, A son who is the theme of honour's tongue; Amongst a grove, the very straightest plant; Who is sweet Fortune's minion and her pride: Whilst I, by looking on the praise of him, See riot and dishonour stain the brow Of my young Harry.

- Bolingbroke looking at his frat-boy son ( Hal/Henry 5) in comparison to the son of his cousin who is actually good at war-related things and being worried for his small idiot

Henry V: Saint Crispins Day

But we in it shall be remember'd; We few, we happy few, we band of brothers; For he to-day that sheds his blood with me Shall be my brother; be he ne'er so vile, This day shall gentle his condition: And gentlemen in England now a-bed Shall think themselves accursed they were not here, And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks That fought with us upon Saint Crispin's day.

- Henry V rousing his men before the battle with the French who * wait for it* lost because it was rained that night and it was too muddy for the french when they reached the valley... Look up Kenneth Branagh’s version, it’s pretty BOMB.