#quantum darwinism

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

It's International Non-Binary People's Day (July 14th), so here's to everyone for whom the transition is the destination.

To my siblings in between and outside the lines, to those who queer the binary and those who fuck (with) it. Whatever pronouns you may use and titles you may claim, whoever and however you love, however you choose to do and redo gender, you are seen and you are known and you are not alone. 💛🤍💜🖤

#nonbinary#non binary pride#genderqueer#genderfluid#queer#trans#because it wouldn't be a quantum post without a citation: 'redoing gender' comes from helana darwin's 2022 book of the same name

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Facebook Page

#albert camus#soren kierkegaard#sigmund freud#psychoanalysis#psychology#middle east#carl jung#gustav klimt#archeology#the buddha#aldous huxley#krishna#albert einstein#philosopher#camus#aristotle and dante discover the secrets of the universe#physics#quantum physics#quantum mechanics#bhagavad gita#zen buddhism#deepak chopra#immanuel kant#spinoza#rene descartes#descartes a kant#confucious#charles darwin#mircea eliade#eusebius

0 notes

Text

The Age of Earth

Determining the age of Earth presents a significant challenge due to the intrinsic nature of time itself.

Our contemporary understanding of quantum physics, coupled with Einstein's theory of relativity, unequivocally demonstrates that time is not an absolute constant but rather a fluid and dynamic entity.

According to current scientific understanding, time is subject to various influences, including gravitational effects, wherein time elapses more slowly in intense gravitational fields such as those surrounding black holes. Another well-documented aspect is relativistic effects, wherein relative motion and acceleration induce time dilation.

Recent advancements in quantum physics even suggest that our consciousness contributes to the perception and processing of temporal information.

Taken to its extreme, the very essence of our perception of time implies that it is more illusionary than commonly acknowledged.

In the domain of cosmology, where vast distances and immense timescales prevail, the relative nature of time becomes notably accentuated. The universe, replete with billions of galaxies and innumerable stars, might have undergone epochs that surpass human comprehension. However, our endeavors to gauge and quantify Earth's age are hindered by our subjective experiences and understanding of time.

By embracing time's malleability and acknowledging its multifaceted nature, we might gain insight into the biblical passage in 2 Peter 3:8, which asserts: "But do not forget this one thing, dear friends: With the Lord, a day is like a thousand years, and a thousand years are like a day."

This perspective also fosters an appreciation for poetry, such as the verse: "The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of his hands." (Psalm 19:1)

Moreover, time even nurtures our faith, leading to profound truths like: "In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth."

#age of earth#creationism#Darwin#Darwinism#quantum#god#bible#books & libraries#bible exegesis#jesus#torah study

1 note

·

View note

Text

Against and For Evolution

WHY STATISTICAL MECHANICS NEGATES EVOLUTION Found on Facebook by Mark Champneys There are 3 billion base pairs in human DNA sequences. This is an arranged molecule of staggering size. The information content of DNA is rooted in the extreme improbability of those relatively few arrangements that code for life, in stark contrast to the vast number of possible sequence arrangements that are…

View On WordPress

#3 billion base pairs#Biologists#Charles Darwin#Eukaryotes#Evolution#favoured races#macroscopic evolution#Planck size#prokaryotes.#Quantum#quantuum mechanics of evolution#Richard Dawkins

0 notes

Text

Well I opened Jenny Sparks #2, and I know I'd seen some of this in solicits, but it never stops being funny to me that Tom King is so hung up on September 11.

I get it. I get it shaped his entire government-work career. I am certain he's seen and heard and read things that he can never, ever get out of his head and so much of his writing career revolves around him trying to find a way to interpret what he's experienced and communicate it to others.

But he literally is writing on the page that Jenny Sparks, a character who was alive for BOTH World Wars and the Cold War, who is famously English, whose backstory involves both the Titanic and Adolf Hitler's turn to politics, who is depicted here as Charles Darwin's grand daughter and buried next to him in Westminster Abbey... is so affected by a particularly American disaster that it destroys the entire mythology of century children.

The character you want, Tom King, is Jenny Quantum. Sparks has already been involved in many of the pivotal events of the 20th century...because she was the Spirit of the 20th Century.

If there is any event defining when the 21st century 'began' in terms of shift in tone, it is in fact September 11.

(Also I saw it noted that Team America: World Police came out 20 years ago today, and I thought to myself that to truly understand Tom King you probably needed to not only be alive, but have been part of the audience that saw Team America: World Police when it was in cinemas, because it's a sharp statement on the sort of attitude and world state King existed in at that time, and it's what he's still working through in every one of his stories that is yet another War on Terror analogy piece)

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

You seem the most experienced so what’s your ultimate death game tier list?

Not sure if I would call myself experienced. I always find new things that I haven't heard about before! But here is my current list of death game media (as I don't really want to rate them all) in no particular order! Games: Your Turn To Die Zero escape series Exit/corners No-one has to die Danganronpa (I won't write them all) Slenderman The Final Prize Is Soup Among us Gnosia Fatal Twelve Quantum Suicide Exile Election

Books/novels: Battle Royale by Koushun Takami Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins (all parts) Maze Runner by James Dasher (first book the most) The Long Walk by Stephen King Global Examination by Mu Su Li

Manga/manhwa/manhua: Omniscient Reader's Viewpoint Tomadochi Game Doubt by Yoshiki Tonagi Judge by Yoshiki Tonagi Sss class suicide hunter King's Game Your Turn To Die

Graphic novels: Geis/Curse of the Chosen

Movies: Hunger Games (all parts) Maze runner (first part the most) Escape Room (2019) Escape Room: Tournament of Champions (2021) Escape Room (2017) Cube (all parts) Saw (all parts) Circle Truth or Dare (2018) Would You Rather Nerve (2016) Ready or Not The Belko Experiment Kaiji: The Ultimate Gambler The Hunt

Tv shows: Alice in Borderland Squid game

Anime: Danganronpa King's Game Deadman Wonderland Battle in 5 second Darwin's Game Btooom! Tomodachi Game Sword Art Online Talentless Nana Death Parade High Rise Invasion Alice in Borderland Mirai Nikki Kaiji Alien Stage (I will leave it here as I don't know to what category it belongs lol)

I know there is more of... everything. But yeah, that's it for now! If anyone has any recommendation that aren't on the list, please, share with us :3

#Some may be a little streched to fit death game trope but well. we live we learn#Maybe I will update the list someday#I really want to read more books this year and maybe at least some will be about death game#and i have a few games to check#thanks for the ask#it is so nice to talk to you about stuff :3#ask goldyluna#death game#games#movies#anime#tv shows#graphic novels#manga#books#i wont tag all of that#i am not trying to die today

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hughie’s dad got quantum instability

A terrifying super power

He’s basically noclipping through matter

Everyone who survived should get treated for radiation sickness immediately

He seemed to have some kind of subconscious control over it otherwise he would have fallen through the floor

Basically he made himself intangible but the moment he becomes tangible whatever matter he was “standing” in gets pushed outwards to make space for the “new” matter just popping into existence

I'm WILDLY sorry but it made me a little bit 🤏 horny now /jk, JK!!!

In fact, the scientific side of The Boys is so fascinating to me, I'd really like to know how much of what they write they actually discuss at a professional level. Biology? Chemistry? Anatomy? EVOLUTION literally happened here - someone call Charles Darwin! Technically, V as an injection/serum is already not needed for the Boys universe, because V not only did sink into the ground in the last episodes (making it impossible to completely destroy it's molecules), but it also runs in Ryan’s, let’s say, factory settings.

We have a whole new branch of human evolution. He's a damn miracle, Sage was absolutely right. And with that in mind, V, woven into his genes, will most likely be dominant, which means that all of Ryan's offspring, if any, will have superpowers. Not “made by men,” but born on equal terms with everyone. That's insane.

Returning to the topic of Hughie's father - it's so funny that Mr. Campbell is like "I CAN WALK THROUGH WALLS"

And he's son is literally "AND I CAN TERELPORT THROUGH SPACE"

Hughie basically can destroy the space-time continuum. Lmao. Best boy.

#the boys#the boys tv#the boys amazon#the boys hughie#hughie campbell#ryan butcher#the boys season 4#maybe I'm talking stupid#I'm not THAT kind of scientist#unfortunately#but i LLLOVEEE this

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Does Quantum Physics Imply About Consciousness?

In recent years much has been written about whether quantum mechanics (QM) does or does not imply that consciousness is fundamental to the cosmos. This is a problem that physicists have hotly debated since the earliest days of QM a century ago. It is extremely controversial; highly educated and famous physicists can't even agree on how to define the problem.

I have a degree in astrophysics and did some graduate level work in QM before switching to computer science; my Ph.D. addressed topics in cognitive science. So I'm going to give it a go to present an accessible and non-mathematical summary of the problem, hewing to as neutral a POV as I can manage. Due to the complexity of this subject I'm going to present it in three parts, with this being Part 1.

What is Quantum Mechanics?

First, a little background on QM. In science there are different types of theories. Some explain how phenomena work without predicting outcomes (e.g., Darwin's Theory of Evolution). Some predict outcomes without explaining how they work (e.g., Newton's Law of Gravity.)

QM is a purely predictive theory. It uses something called the wave function to predict the behavior of elementary particles such as electrons, photons, and so forth. The wave function expresses the probabilities of various outcomes, such as the likelihood that a photon will be recorded by a detection instrument. Before the physicist takes a measurement the wave function expresses what could happen; once the measurement is taken, it's no longer a question of probabilities because the event has happened (or not). The instrument recorded it. In QM this is called wave function collapse.

The Measurement Problem

When a wave function collapses, what does that mean in real terms? What does it imply about our familiar macroscopic world, and why do people keep saying it holds important implications for consciousness?

In QM this is called the Measurement Problem, first introduced in 1927 by physicist Werner Heisenberg as part of his famous Uncertainty Principle, and further developed by mathematician John Von Neumann in 1932. Heisenberg didn't attempt to explain what wave function collapse means in real terms; since QM is purely predictive, we're still not entirely sure what implications it may hold for the world we are familiar with. But one thing is certain: the predictions that QM makes are astonishingly accurate.

We just don't understand why they are so accurate. QM is undoubtedly telling us "something extremely important" about the structure of reality, we just don't know what that "something" is.

Interpretations of QM

But that hasn't stopped physicists from trying. There have been numerous attempts to interpret what implications QM might hold for the cosmos, or whether the wave function collapses at all. Some of these involve consciousness in some way; others do not.

Wave function collapse is required in these interpretations of QM:

The Copenhagen Interpretation (most commonly taught in physics programs)

Collective Collapse interpretations

The Transactional Interpretation

The Von Neumann-Wigner Interpretation

It is not required in these interpretations:

The Consistent Histories interpretation

The Bohm Interpretation

The Many Worlds Interpretation

Quantum Superdeterminism

The Ensemble Interpretation

The Relational Interpretation

This is not meant to be an exhaustive list, there are a boatload of other interpretations (e.g. Quantum Bayesianism). None of them should be taken as definitive since most of them are not falsifiable except via internal contradiction.

Big names in physics have lined up behind several of these (Steven Hawking was an advocate of the Many Worlds Interpretation, for instance) but that shouldn't be taken as anything more than a matter of personal philosophical preference. Ditto with statements of the form "most physicists agree with interpretation X" which has the same truth status as "most physicists prefer the color blue." These interpretations are philosophical in nature, and the debates will never end. As physicist M. David Mermin once observed: "New interpretations appear every year. None ever disappear."

What About Consciousness?

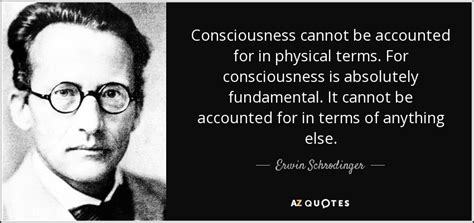

I began this post by noting that QM has become a major battlefield for discussions of the nature of consciousness (I'll have more to say about this in Part 2.) But linkages between QM and consciousness are certainly not new. In fact they have been raging since the wave function was introduced. Erwin Schrodinger said -

And Werner Heisenberg said -

In Part 2 I will look deeper at the connections between QM and consciousness with a review of philosopher Thomas Nagel's 2012 book Mind and Cosmos. In Part 3 I will take a look at how recent research into Near-Death Experiences and Terminal Lucidity hold unexpected implications for understanding consciousness.

(Image source: @linusquotes)

#quantum physics#consciousness#copenhagen interpretation#superdeterminism#many worlds#philosophy#physics#philosophy of mind#brain#consciousness series

99 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why are you not a materialist?

We live inside of ideas concretized as sculpted landscapes, physical structures, technologies and tools, and language itself. In spite of Marx, the working class keeps voting on the basis of culture; in spite of Darwin, we still choose strange-looking lovers. Even Marx allowed that human beings, unlike bees and beavers, build freely and in accordance with beauty rather than necessity. Even Freud granted that most of human sexuality is, strictly speaking, perverse, not focused on the reproductive organs and their function but on all manner of fetishes, literally from head to toe. Scientists can't seem to prove that the brain is the locus of consciousness, nor do they seem to know what consciousness even is. The quantum physicists, if I understand them, posit a reality defined at the subatomic level by the observer. The archaeologists keep pushing the advent of civilization further and further back into the past, with deterministic models (e.g., civilization requires agricultural settlement) increasingly challenged and cult and cultus appearing to be the driver. Every third or fourth person has seen a ghost. What material interest of yours is served by your desire to know why I'm not a materialist? Almost everything in human life is beautifully gratuitous, irreducible to need and program. That there is something rather than nothing remains both a miracle and a mystery.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Clay & volume renders ↑

Concept sketches ↑

—

Quantum Darwinism • Physics Illustration • 2019

Charles Darwin was born on this day, February 12, 1809. #DarwinDay seems like a good one to share one of my favorite old projects,

Created for a 2019 Quanta Magazine article by Philip Ball: Quantum Darwinism, an Idea to Explain Objective Reality, Passes First Tests

The mirrors represent reality, and the foreground a quantum world with a wave in superposition. When it decoheres, only blue remains.

This is now outdated skill & technique-wise, but I still like a lot about it, especially the subject matter. I enjoy mixing scientific concepts with fantastical imagery — when it makes sense, of course.

One of the central tenets of my creative direction for Quanta was that the artwork should match the excitement and wonder of the stories it accompanies. "Art is a lie that tells the truth" — it's about using visual storytelling to reveal the real magic of the science detailed, not just give a literal translation. It's disappointing to see a fascinating story accompanied by dull visuals that don't do it justice (or worse, repel). Not saying I always succeeded in the former, or avoiding the latter, but I sure as hell tried!

#natureintheory#olena shmahalo#art director#art direction#3d illustration#3d artist#3d art#3d modeling#physics#illustration#sciart#published#zbrush#science illustration#3d#c4d#Redshift#magic aesthetic#magic#quantum physics#particle physics#quanta magazine#3d sculpting#darwin#charles darwin#darwinday#quantum darwinism#decoherence

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Science may be known for banishing the demons of superstition from the modern world. Yet just as the demon-haunted world was being exorcized by the enlightening power of reason, a new kind of demon mischievously materialized in the scientific imagination itself. Scientists began to employ hypothetical beings to perform certain roles in thought experiments—experiments that can only be done in the imagination—and these impish assistants helped scientists achieve major breakthroughs that pushed forward the frontiers of science and technology.

Spanning four centuries of discovery—from René Descartes, whose demon could hijack sensorial reality, to James Clerk Maxwell, whose molecular-sized demon deftly broke the second law of thermodynamics, to Darwin, Einstein, Feynman, and beyond—Jimena Canales tells a shadow history of science and the demons that bedevil it. She reveals how the greatest scientific thinkers used demons to explore problems, test the limits of what is possible, and better understand nature. Their imaginary familiars helped unlock the secrets of entropy, heredity, relativity, quantum mechanics, and other scientific wonders—and continue to inspire breakthroughs in the realms of computer science, artificial intelligence, and economics today.

The world may no longer be haunted as it once was, but the demons of the scientific imagination are alive and well, continuing to play a vital role in scientists’ efforts to explore the unknown and make the impossible real.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not to sound too much like a crazy person but it is interesting how religion is not taught in schools (not even comparative religion, which should be, just so people can learn to navigate other cultures’ ways of life) but Darwinism/evolution is, when it remains a relatively unfounded scientific theory after 100 years. Not that it’s not clear species can be categorized together as changing in certain ways over periods of time, but there are huge gaps and unanswered questions as to What Has Actually Gone On, especially in the light of living fossils of today, the complete extinction of certain kinds of animal and plant life, and how we have loads of animals that generally do not make a lot of sense or adapt in ways other than what we consider ‘evolution.’

And please do not get me started on how the idea of “survival of the fittest” has damaged human perceptions of how society is and should be.

I’ve said this before but one of the great mistakes of the Western Enlightenment was the labeling of some things “secular” and some things “sacred” whereas before that time scientists, philosophers and theologians all left room for mystery. There was no either/or — either belief in divinity or strict materialism — and the denial of the presence of the transcendent in the physical (what is often known as incarnational theology) has done more damage to humanity than any other movement or idea.

(Ex. If the material is not also something sacred it’s a damn good excuse to treat other human beings like trash.)

But we took even learning about faith-based ways of life out of our schools and taught materialism instead.

Thank God (really) for the quantum physicists and astrophysicists who have been speaking up to say you know, when you really look into things it is all just way more than we have ever even begun to understand.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I began to discern the paradox lurking at the heart of Karl Popper's career when, prior to interviewing him in 1992, I asked other philosophers about him. Queries of this kind usually elicit dull, generic praise, but not in Popper’s case. Everyone said this opponent of dogmatism was almost pathologically dogmatic. There was an old joke about Popper: The Open Society and its Enemies should have been titled The Open Society by One of its Enemies.

(…)

I noted that in his writings he seemed to abhor the notion of absolute truths. “No no!” Popper replied, shaking his head. He, like the logical positivists before him, believed that a scientific theory can be “absolutely” true. In fact, he had “no doubt” that some current theories are true (although he refused to say which ones). But he rejected the positivist belief that we can ever know that a theory is true. “We must distinguish between truth, which is objective and absolute, and certainty, which is subjective.”

Popper disagreed with the positivist view that science can be reduced to a formal, logical system or method. A scientific theory is an invention, an act of creation, based more upon a scientist's intuition than upon pre-existing empirical data. “The history of science is everywhere speculative,” Popper said. “It is a marvelous history. It makes you proud to be a human being.” Framing his face in his outstretched hands, Popper intoned, “I believe in the human mind.”

For similar reasons, Popper opposed determinism, which he saw as antithetical to human creativity and freedom. “Determinism means that if you have sufficient knowledge of chemistry and physics, you can predict what Mozart will write tomorrow,” he said. “Now this is a ridiculous hypothesis.” Popper realized long before modern chaos theorists that not only quantum systems but even classical, Newtonian ones are unpredictable. Waving at the lawn outside the window he said, “There is chaos in every grass.”

(…)

Popper abhorred philosophers who argue that scientists adhere to theories for cultural and political rather than rational reasons. Such philosophers resent being viewed as inferior to genuine scientists and are trying to “change their status in the pecking order.” Popper was particularly contemptuous of postmodernists who argued that “knowledge” is just a weapon wielded by people struggling for power. “I don't read them,” Popper said, waving his hand as if at a bad odor. He added, “I once met Foucault.”

I suggested that the postmodernists sought to describe how science is practiced, whereas he, Popper, tried to show how it should be practiced. To my surprise, Popper nodded. “That is a very good statement,” he said. “You can't see what science is without having in your head an idea what science should be.” He admitted that scientists invariably fall short of the ideal he set for them. “Since scientists got subsidies for their work, science isn't exactly what it should be. This is unavoidable. There is a certain corruption, unfortunately. But I don't talk about that.”

Popper then proceeded to talk about it. “Scientists are not as self-critical as they should be,” he asserted. “There is a certain wish that you, people like you”--he jabbed a finger at me—“should bring them before the public.” He stared at me a moment, then reminded me that he had not sought this interview. “Far from it,” he said. Popper then plunged into a technical critique of the big bang theory. “It's always the same,” he summed up. “The difficulties are underrated. It is presented in a spirit as if this all has scientific certainty, but scientific certainty doesn't exist.”

I asked Popper if he felt biologists are also too committed to Darwin's theory of natural selection; in the past he had suggested that the theory is tautological and thus pseudo-scientific. “That was perhaps going too far,” Popper said, waving his hand dismissively. “I'm not dogmatic about my own views.” Suddenly he pounded the table and exclaimed, “One ought to look for alternative theories!”

Popper scoffed at scientists’ hope that they can achieve a final theory of nature. “Many people think that the problems can be solved, many people think the opposite. I think we have gone very far, but we are much further away. I must show you one passage that bears on this.” He shuffled off and returned with his book Conjectures and Refutations. Opening it, he read his own words with reverence: “In our infinite ignorance we are all equal.”

I decided to launch my big question: Is his falsification concept falsifiable? Popper glared at me. Then his expression softened, and he placed his hand on mine. “I don't want to hurt you,” he said gently, “but it is a silly question." Peering searchingly into my eyes, he asked if one of his critics had persuaded me to pose the question. Yes, I lied. “Exactly,” he said, looking pleased.

“The first thing you do in a philosophy seminar when somebody proposes an idea is to say it doesn’t satisfy its own criteria. It is one of the most idiotic criticisms one can imagine!” His falsification concept, he said, is a criterion for distinguishing between empirical and non-empirical modes of knowledge. Falsification itself is “decidably unempirical”; it belongs not to science but to philosophy, or “meta-science,” and it does not even apply to all of science. Popper seemed to be admitting that his critics were right: falsification is a mere guideline, a rule of thumb, sometimes helpful, sometimes not.

Popper said he had never before responded to the question I had just asked. “I found it too stupid to be answered. You see the difference?” he asked, his voice gentle again. I nodded. The question seemed silly to me, too, I said, but I just thought I should ask. He smiled and squeezed my hand, murmuring, “Yes, very good.”

Since Popper seemed so agreeable, I mentioned that one of his former students had accused him of not tolerating criticism of his own ideas. Popper's eyes blazed. “It is completely untrue! I was happy when I got criticism! Of course, not when I would answer the criticism, like I have answered it when you gave it to me, and the person would still go on with it. That is the thing which I found uninteresting and would not tolerate.” In that case, Popper would throw the student out of his class.

(…)

I slipped in a final question: Why in his autobiography did Popper say that he is the happiest philosopher he knows? “Most philosophers are really deeply depressed,” he replied, “because they can’t produce anything worthwhile.” Looking pleased with himself, Popper glanced over at Mrs. Mew, who wore an expression of horror. Popper’s smile faded. “It would be better not to write that,” he said to me. “I have enough enemies, and I better not answer them in this way.” He stewed a moment and added, “But it is so.”

(…)

When Popper died two years later, the Economist hailed him as having been “the best-known and most widely read of living philosophers.” But the obituary noted that Popper’s treatment of induction, the basis of his falsification scheme, had been rejected by later philosophers. “According to his own theories, Popper should have welcomed this fact,” the Economist noted, “but he could not bring himself to do so. The irony is that, here, Popper could not admit he was wrong.”

Can a skeptic avoid self-contradiction? And if he doesn’t, if he arrogantly preaches intellectual humility, does that negate his work? Not at all. Such paradoxes actually corroborate the skeptic’s point, that the quest for truth is endless, twisty and riddled with pitfalls, into which even the greatest thinkers tumble. In our infinite ignorance we are all equal.”

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Facebook 5/30/23

Star Lady

“Young people, especially young women, often ask me for advice. Here it is. Do not undertake a scientific career in quest of fame or money. There are easier and better ways to reach them. Undertake it only if nothing else will satisfy you. Cecilia Payne

1925 – Harvard Observatory – Cambridge, Massachusetts: Most people know that Isaac Newton discovered gravity, Charles Darwin his theory of evolution and Albert Einstein the relativity of time. But almost 100 years since her discovery of the composition of the stars, few know the name Cecilia Payne. Her road to the stars had plenty of twists and turns.

Raised by a single mother in the small town of Wendover, England, Cecilia graduated high school in 1919. There was no money to attend college, so she worked hard to earn a scholarship to Cambridge University. Cecilia wanted to study science but was unsure which field until she participated in a lecture about the 1919 total solar eclipse – the longest eclipse in 500 years. Astronomy and astrophysics became her love.

In 1923, women were not welcome in the world of science. When Cecilia completed her degree in astronomy, Cambridge refused to award her a degree. It would be 25 years before Cambridge awarded degrees to women. After realizing there would be no opportunity for graduate work, Cecilia left England for Harvard University in America – one of the only academic institutes that accepted women in physics.

Cecilia received a graduate fellowship to study at the Harvard Observatory. At the time, astronomers believed that the earth and the sun consisted of the same chemical elements.

Cecilia’s doctoral thesis, Stellar Atmospheres, used the new science of quantum physics to determine if this hypothesis was true

Cecilia could study the color spectrums of several hundred thousand stars archived in the observatory by attaching a spectroscope to a telescope. She demonstrated how to decode complicated starlight spectra to determine the chemical elements in the stars. For the first time, Cecilia discovered that the sun and stars consisted primarily of hydrogen and helium. At the same time, the earth was known to consist of more than 100 elements.

Cecilia’s astronomy advisor, Harlow Shapely, was so excited about her discovery that he sent a copy of her thesis to the distinguished Princeton University astronomer, Dr. Henry Norris Russell. Russell responded, “This is clearly impossible. It contradicts prevailing wisdom.”

In 1925, 25-year-old Cecilia Payne became the first person to earn a Ph.D. in astronomy from Radcliffe College because Harvard did not grant doctoral degrees to women. She inserted a disclaimer in her thesis to protect her career: “The calculated abundances of hydrogen and helium were almost certainly not real.” Russell published Cecilia’s discovery four years later and took the credit for himself.

After completing her doctoral work, Cecilia remained at Harvard and worked for Shapely. Although she did the same job as other professors, her title and salary were that of a technical assistant. There were no female professor positions. Cecilia and her team made more than three million observations of stars’ light spectrums helping scientists and astronomers to better understand the origins of the universe. Much of her work was done with Russian astronomer Sergei Gaposchkin, whom she married in 1934.

In 1956, more than 30 years after her landmark discovery, and despite the grumbling of some professors, 56-year-old Dr. Cecilia Payne became the first woman promoted to full professor at Harvard. She also became the first woman to chair the astronomy department. Cecilia retired from teaching at Harvard a decade later. Despite retirement, she continued her research as a member of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory.

In 1976, in a touch of irony, Cecilia Payne received the Henry Norris Russell Prize presented by the America Astronomical Society. Distinguished astronomer, Otto Struve, referred to her doctoral work as “the most brilliant Ph.D. thesis ever written in astronomy.”

She died three years later. Her obituary reads in part, “Cecilia Helena Payne-Gaposchkin, a pioneering astrophysicist and probably the most eminent woman astronomer of all time, died in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on December 7, 1979.”

Cecilia blazed a trail for women at Harvard and beyond, inspiring several generations of women to study science and astronomy. In 2008, in recognition of her pioneering work in understanding the composition of the stars and the universe, the Institute of Physics established the Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin Medal and Prize.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Darwin Núñez is a quantum entanglement style Randomness and Uncertainty ⚛️

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Richard Dawkins; he thinks there is a fundamental conflict between science and religion.

This would come have as a surprise to some of the greatest names in science: Nicolaus Copernicus (a monk), Johannes Kepler, Galileo Galilei, Isaac Newton, Robert Boyle, Michael Faraday, Joseph Priestley, James Clerk Maxwell, Charles Darwin, Gregor Mendel (the founder of genetics and abbot of a monastery), Lord Kelvin and Albert Einstein. Plus, many of the pioneers of quantum physics: Werner Heisenberg, Max Plank, Erwin Schrödinger, James Jeans, Louis de Broglie, Wolfgang Pauli and Arthur Eddington. And today's scientists – the astrophysicist Paul Davies, Simon Conway Morris (Professor of Evolutionary Paleobiology at Cambridge), Alasdair Coles (Professor of Neuro-immunology at Cambridge), John Polkinghorne (who was Professor of Mathematical Physics at Cambridge), Russell Stannard, Freeman Dyson ... and Francis Collins, who led the team of 2,400 international scientists on the Human Genome Project and was an atheist until the age of 27, when he became a Christian.

~ John Marsh

3 notes

·

View notes