#przeworsk culture

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

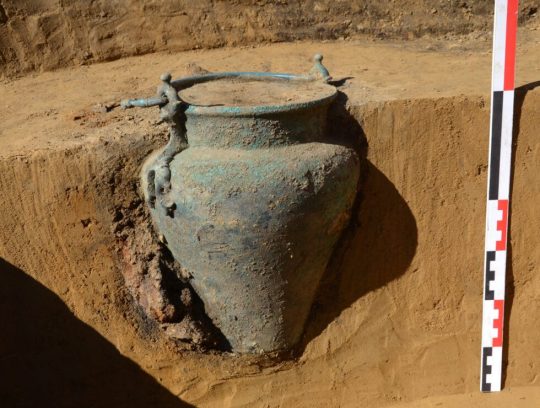

Rare Roman vessel Found at 2,000-Year-Old Burial Site in Poland

Archaeologists investigating a 2,000-year-old burial site in Poland have discovered cremated remains inside a Roman vessel, one of very few of its type ever found in the country.

The discovery was made during research in the town of Kazimierza Wielka, southern Poland, led by archaeologists from the Jagiellonian University in Kraków. In total, 160 objects were found, with some dating back as far as the Neolithic period, reports the Polish Press Agency (PAP).

A particularly interesting find was a burial site dating to the pre-Roman and early Roman period, which contained four cremation graves and 23 skeletons.

One set of cremated remains had been placed inside a vessel (pictured above), made from copper alloys, imported from the Roman empire and decorated with dolphin shapes.

“Such vessels are exceptionally rare in Poland,” said Kamil Sikora, a spokesman for the Jagiellonian University.

In areas occupied by the so-called Przeworsk culture, which lived in what is now central and southern Poland between the 3rd century BC and the 5th century AD, only seven such vessels have been discovered and only four were used as urns.

Alongside the urn, the archaeologists discovered weapons typical of warriors from the Przeworsk culture, including a sword and two spearheads, as well as a shield boss. The items had been ritually bent and damaged, which is consistent with the funeral practices of the time.

The researchers also note that the discovery of skeletal remains is unusual for the Przeworsk culture, which normally cremated its dead. Most of those found at this site are the remains of women, who were buried with ornaments and items of clothing.

By Daniel Tilles.

#Rare Roman vessel Found at 2000-Year-Old Burial Site in Poland#Kazimierza Wielka#ancient grave#ancient tomb#ancient urn#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#Przeworsk culture#roman history#roman empire#roman art#ancient art#art history

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Przeworsk Culture: this was in part a continuation of the Pomeranian culture of the north, suggesting some southwards migration during the creation of the Oxhoft, but it also bore significant influence from the La Tene and Jastorf cultures.

#history#historyfiles#ancient world#archaeology#ancient europe#iron age#poland#europe#przeworsk#pomeranian#oxhoft#la tene#jastorf

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quelle a été l'ampleur de l'allélophagie dans toute l'histoire de notre espèce ? Certains disent qu'elle aurait cessé en Europe avec l'évangélisation de l'est et le déclin de la culture de Przeworsk.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, great page you have there! I just wanted to ask from which culture do Slavs come from? Lusatian culture? Przeworsk culture? Or something else? Entire people can't just like that pop up out of thin air in 6th century?

Oh my, that’s one of the greatest mysteries from that part of the world! Archeologists and historians still argue about that question. I don’t want to answer it because there are way too many compelling theories but not enough clear evidence yet.

But to put things into perspective: Slavic people inhabit vast lands and are really varied (take the linguistic groups of West / East / South as an example). They surely don’t “come from” one culture only. The interesting question to me is: which culture brought the language that unified the people?

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

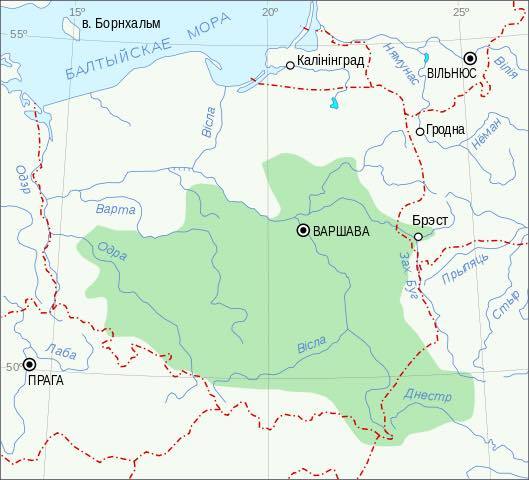

“Celts and Slavs in Poland.

Below, a map showing the approximate extent of the Przeworsk culture in Poland. Named after a modern town where discoveries were first made by archaeologists, ‘Przeworsk’ is the name given by them to trends in the material culture of southern and central Poland from 250 B.C. to c. AD 450

.The Przeworsk culture evolved from the previous Lusatian culture of Poland, which probably represents early Slavic or proto-Slavic peoples. The Lusatian culture had evolved locally starting around 1,300 B.C. and was heavily influenced by the Celtic Urnfield culture (1,300 to c. 750 B.C.) of Central Europe. Starting from around 350 B.C., intrusions by bands of Celts into southern Poland kickstarted a process by which the local Lusatian culture evolved into what we now know as the Przeworsk culture.

Celts first arrived in Poland around 350 B.C., arriving from the area of Bohemia, in what is now the Czech Republic (Gediga, pp. 86-91). These groups probably came as refugees from upheavals occurring in Central Europe among the Celts themselves. At around that time, a group from Switzerland appears to have invaded Bohemia, resulting in the destruction of the Celtic hill-fort of Zavist (Cunliffe, p. 79).

These first Celts settled to the south of Wroclaw and around Mount Šlęza, while another group settled in the Glubczyce highlands. These two groups remained settled there until about 120 B.C., when for unknown reasons, the Wroclaw settlement dispersed and the Glubczyce group migrated southward (Gediga, pp. 86-91).

Two more groups of Celts arrived in Poland at around 270 B.C. settling in the San river basin and around Krakow. This last group mingled with the locals of Lusatian culture derivation and began the development of what we call the Przeworsk culture. At around 60 B.C. more Celts arrived in the Krakow area from Slovakia, probably after having been displaced from their homeland by the Dacians, who, led by their king, Burebista, defeated the Celtic Boii and Taurisci kingdoms of Central Europe in a particularly violent war (Poleski, p. 13). Thus, in southeastern Poland a new polity began to form, which consisted of mixed populations of Celtic migrants and local Slavs.

The Przeworsk culture spread quickly westward, absorbing other Slavic and Germanic communities and eventually reaching Kujawy, farther to the north. By the 1st century AD, Przeworsk was the dominant culture of Poland and greatly influenced other neighboring peoples, such as the Oksywie culture of northern Poland (Godlowski, 1970 & Makiewicz, pp. 94-7), and the Zarubintsy culture in the Galicia region of Poland and west Ukraine.

Przeworsk culture settlements consisted of small, unfortified farming villages with square or rectangular wooden houses. The people of the Przeworsk culture practiced both agriculture and animal husbandry. Wheat, barley, millet, rye and oats were all grown and fields were alternated between cultivation and grazing. Cattle, pigs, sheep, horses and goats were also an integral part of the agrarian economy. Wells, a concept introduced into the region by the Celts, were also dug so that settlements no longer had to be built near rivers (Naglik, 2005). The people of the Przeworsk culture also mastered iron smelting and extraction from bog ores, working with techniques introduced by the Celts (Andrzejowski, 2010 & Gediga, pp. 86-91). Additionally, the Przeworsk culture people mined salt and benefited economically from the Baltic amber trade (Adamczyk, 2005 & Gediga, pp. 86-91).

Early burial practices followed the old Lusatian/Urnfield custom of cremation and burial in clay urns. This is in contrast to the Celts who had first migrated into Poland, who‘d been more inclined to inhumation burial (Gediga, pp. 86-91). Grave goods often included horse gear and Celtic-style (La Tène) weapons such as spears, swords and characteristic oblong shields.

Turning to the historical sources, the identity and historical role of the Przeworsk culture people can perhaps be further defined. Roman sources such as Tacitus, Strabo and Claudius Ptolemy, all wrote of a powerful tribal federation existing between the Oder and Vistula rivers, the area occupied by what we now call the Przeworsk culture. This tribal federation was referred to in the sources as “Lugii” or ‘Lugians’.

According to Tacitus’ treatise “Germania”, the Lugii consisted of five tribes: Helveconae, Nahanarvali, Manimi, Helisii and Harii (Tacitus, “Germania” XLIII). Of these tribal names, “Lugii” and “Helveconae” are unquestionably Celtic. “Lugii” derives almost certainly from the Celtic god of commerce and money, Lugus (identified by the Romans with Mercury), while “Helveconae” would appear to mean “prosperous hounds/wolves” (from Gaulish “elu” meaning “gain”, “prosperity” and “con”, meaning “dog/wolf”).

One need only to compare Helveconae to other known Celtic tribal names, such as that of the “Helvetii” of Switzerland, or of the “Helvii” of southern France, and the connection is clear. In like manner, “Helisii” has a Celtic ring to it, being similar to that of the Ligurian “Elysices” tribe of southern France, though a connection to Celtic languages is far less certain in this case.

Speculation abounds as to whether the modern place-name Kalisz, in central Poland, might be derived from the ancient Helisii tribal name. Other tribal names mentioned by Tacitus, such as “Harii” and “Nahanarvali” are clearly not Celtic. The former is Germanic, being connected to the word “here”, meaning army. As the Harii were described as a fierce group of warriors who fought at night with black shields and black painted skin, it is possible that this wasn’t so much a tribe as it was the military aristocracy of the Lugian tribal federation. Other than this terrifying bit of information about the “Harii”, the only other insight Tacitus gives us into the culture of the Lugii is his description of a cult to the Indo-European horse-twin gods, known locally as “Alcis”.

The sanctuary was located in a sacred grove of the Nahanarvali tribe. No images of the gods were kept there, and the worship was presided over by priests “appareled like women”. Worship of the horse-twin gods is more familiar as a Germanic tradition, reflected in later Anglo-Saxon lore about the brothers Hengist and Horsa. On the other hand, that the gods were attended by priests appareled like women is reflective of Scythian practice (Silk Road Foundation, 2000).

The mysterious Nahanarvali were almost certainly not of Celtic extraction.Tacitus’ tribal names are not repeated in other sources. Ptolemy for example, has the Lugii made up of three tribes: the Diduni in Silesia, the Buri to the east of them, and the Omani at an unspecified location (Ptolemy, II, X). In the area of Silesia, Ptolemy locates the settlement of “Lugidunum”, another clearly Celtic name, meaning “hill-fort of the Lugii”. “-Dunum” is a uniquely Celtic word to describe a fortified settlement and so here, once again, we find clear evidence that at least some of the Lugii were speakers of a Celtic language. The Buri on the other hand, were known to be Germanic, while the Omani have been speculated to be the same people as the Atmoni, a branch of the probably Slavic Bastarnae tribal federation.

The Bastarnae would appear to correspond to the neighboring Zarubintsy archaeological culture (250 B.C. to c. AD 50). Like the Lugii, they were probably of Celto-Slavic origin, with heavy influences from the neighboring Sarmatians as well.That the Lugii were a force to be reckoned with is evident from the historical record itself. According to Tacitus’ “Annals”, in the year 50 AD, Vannius, king of the Germanic Quadi and Marcomanni tribes (who inhabited what is now Czech Republic and Slovakia), was overthrown by his nephews, Vangio and Sido, with help from Vibilius, king if the neighboring Hermunduri tribe (Tacitus, “Annals”, XII, XXIX). Vannius had been appointed through Roman patronage and the Marcomanni-Quadi alliance he ruled over was the dominant political, military and economic force of Germany at that time.

During the coup, Vannius gathered a large force of Germanic foot-soldiers and allied Sarmatian horsemen. Being outnumbered, he retreated and shut himself up in a fortified settlement. A large force of Lugians had invaded the kingdom to take advantage of the chaos and plunder Vannius’ riches. Seeking to reverse his fortunes, Vannius sallied out with his army to deal with the Lugians and Hermundurians. The ensuing clash resulted in the destruction of the German-Sarmatian army, with Vannius himself escaping badly wounded to a Roman fleet, which lie waiting for him on the river Danube. Later, Cassius Dio’s “Roman History” records other events involving the Lugii in the years 91-92 AD. That year, the tribal federation was embroiled in a war with the Germanic Suebi and sought an alliance with the Roman empire (Dio, “Roman History”, LXVII). Emperor Domitian dispatched a small detachment of 100 horsemen to participate in the war on the side of the Lugians. Thus, it appears that like many other Celtic peoples in Central Europe, the Lugii opted for alliance with Rome, in order to counterbalance the formidable power of both the Germanic peoples and the Dacians. However, the alliance does not appear to have lasted long, for by 279 we find the Lugians (called “Longiones” by Zosimus’ “Nova Historia”) raiding deep into Roman territory and plundering the province of Rhaetia (part of modern Austria and Switzerland).

Here, the Roman Emperor Probus repelled their attack and captured their king, named as ‘Semno’ (Zosimus, “Nova Historia”, I:LXVII); Semno was released upon accepting terms from the Romans. This is the last known historical mention of the Lugian people. By the 5th century AD, the Przeworsk culture disappeared from Poland, probably as a result of the invasions of the Asiatic Huns.

As archaeology is unveiling more about Poland’s ancient past, lost bits of history come into the light. Not only does it appear that ancient Poles formed a formidable and highly successful polity in Central Europe, but also that Celt and Slav both coalesced to form a hybrid culture with a high degree of vitality.

Sources:

Adamczyk, Kazimierz. “The Archaeology of the Transit Gas Pipeline”, Living Archaeology, English edition. 2005

Andrzejowski, Jacek. “The Przeworsk Culture, A Brief History (for the Foreigners)”. Worlds Apart? Contacts Across the Baltic Sea in the Iron Age: Network Denmark-Poland 2005-2008. Copenhagen-Warsaw. 2010

Barry Cunliffe, “The Ancient Celts”. Oxford University Press, 1997

Cassius Dio, “Roman History”.

Claudius Ptolemy, “Geography”.

Cornelius Tacitus, “Annals”.Cornelius Tacitus, “Germania”.

Gediga, Boguslaw and Makiewicz, Tadeusz. “Foundations of Poland (until year 1,038)”. Wydawnictwo Dolnoślaskie. 2002

Godlowski, K. “The Chronology of Late Roman and Early Migration Periods in Central Europe”. Crakow. 1970

Naglik, Riszard. “Archaeological Motorway”, Living Archaeology, English Edition. 2005.

Poleski, Jacek. “Chronology of Polish History”. Wydawnictwo Dolnoślaskie. 1999

Silk Road Foundation. “The Scythians”, 2000. Link: http://silkroadfoundation.org/artl/scythian.shtml.oldZosimus,

“Nova Historia”.

Link from facebook page “Celtic Europe”: https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=2766737023343676&id=2158176407533077&__tn__=K-R

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

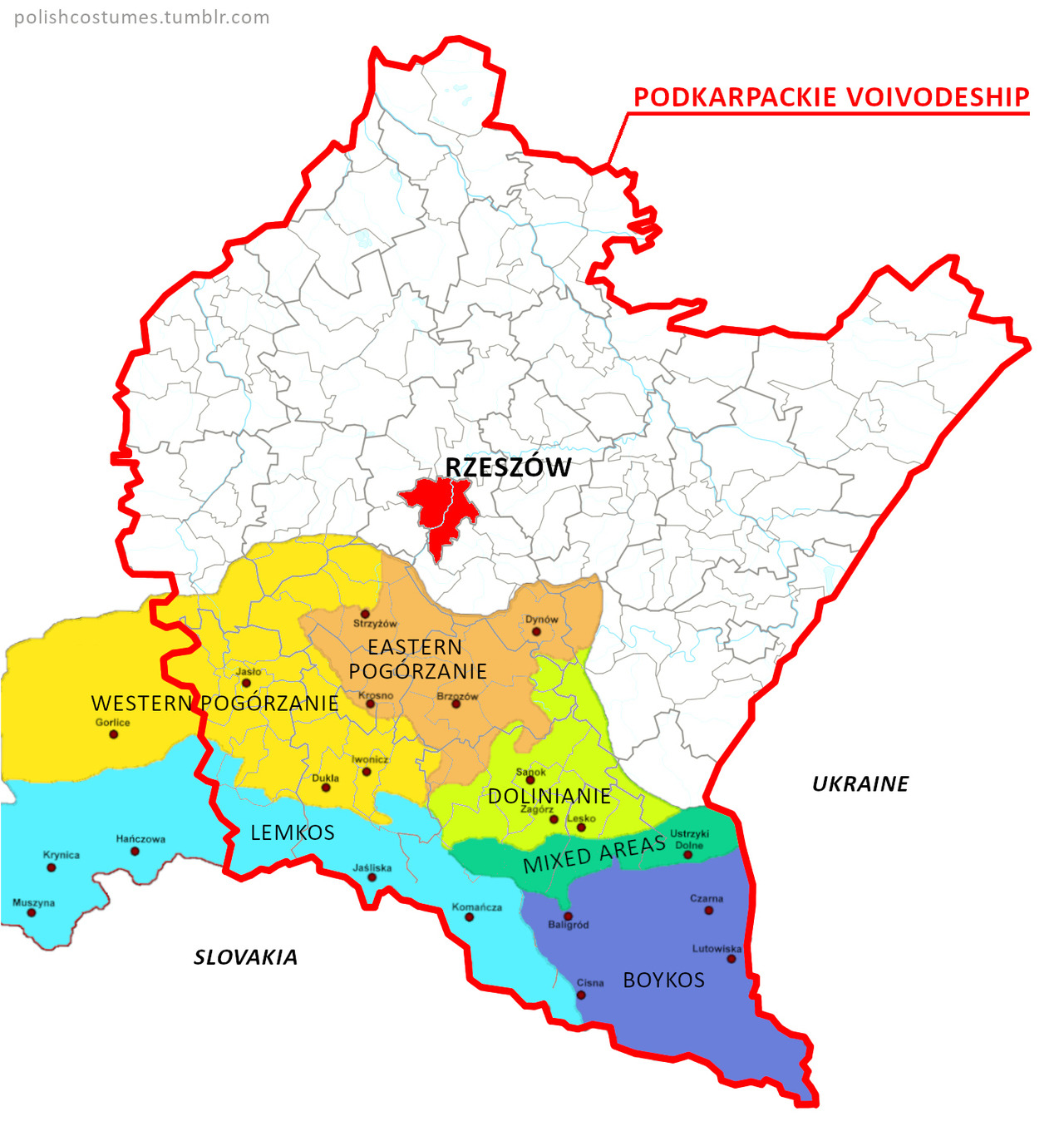

I found out my father has a good chunk of ancestry from Podkarpackie Voivodeship. Do you know of any outfits from that area?

Podkarpackie is a large administrative district with many types of costumes! If you want a clear reference, you need to check a more precise localisation of your ancestry. You can see some on my [list of regions](https://polishcostumes.tumblr.com/regions).The most well-known outfit from that area is from vicinity of [**Rzeszów**](https://polishcostumes.tumblr.com/tagged/rzesz%C3%B3w). Of the other major ones, there are [**Łańcut**](https://polishcostumes.tumblr.com/tagged/%C5%82a%C5%84cut), [**Przeworsk**](https://polishcostumes.tumblr.com/tagged/przeworsk) and [**Lubaczów**](https://polishcostumes.tumblr.com/tagged/lubacz%C3%B3w) outfits located to the east from Rzeszów. In the northern areas of the district, between the Wisła and San rivers, there are [**Lasowiacy**](https://polishcostumes.tumblr.com/tagged/lasowiacy). A bit to the south-west from the city there is the [**Krosno**](https://polishcostumes.tumblr.com/tagged/krosno) variant. There are many smaller variants which I’m still collecting bit by bit, such as outfits from villages of [**Cewków**](https://polishcostumes.tumblr.com/tagged/cewk%C3%B3w) or [**Wyszatyce**](https://polishcostumes.tumblr.com/tagged/wyszatyce). Other large areas in the southern parts of the district had many variants of outfits worn by certain cultural or ethnic groups, such as [**Pogórzanie**](https://polishcostumes.tumblr.com/tagged/pog%C3%B3rzanie) ([Polish Uplanders](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polish_Uplanders), divided into its western and eastern subgroups), Dolinianie (meaning sth like Valley People, which were mixed Polish and Ukrainian groups), and the southernmost were inhabitated by [Lemkos](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lemkos) and [Boykos](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boykos). For those southern groups, there is a [helpful map](https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plik:PogMAP2.png) which I superimposed over the district’s map:

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Celts integrated with the representatives of the so-called Przeworsk culture, identified with the Germanic tribe of Vandals. The remaining groups, which were not absorbed by the local tribes, probably migrated to other parts of the world, also due to the migration of Germanic peoples to our lands. The Celts were used to and eager to wander. If they could find another place to live, they didn't hesitate. Today, Celtic remains in Poland are another testimony to the cultural and ethnic richness of our country's prehistory.

Where do Poles come from?

Skąd pochodzą Polacy?

"We are descendants of a mighty people"

„Jesteśmy potomkami potężnego ludu”

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

The M.O.A.B. (Massive Ordnance Air Blast, nicknamed Mother Of All Bombs) is a hidden 25 kill-streak (24 with Hardline) reward featured in Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3. The M.O.A.B. is obtainable with any Strike Package.

The Vandals were an East Germanic tribe, or group of tribes, who were first heard of in southern Poland, but later moved around Europe establishing kingdoms in Spain and later North Africa in the 5th century.[1]The Vandals are believed to have migrated from southern Scandinavia to the area between the lower Oder and Vistula rivers during the 2nd century BC and to have settled in Silesia from around 120 BC.[2][3][4] They are associated with the Przeworsk culture and were possibly the same people as the Lugii. Expanding into Dacia during the Marcomannic Wars and to Pannonia during the Crisis of the Third Century, the Vandals were confined to Pannonia by the Goths around 330 AD, where they received permission to settle by Constantine the Great. Around 400 the Vandals were pushed westwards again, this time by the Huns, crossing the Rhine into Gaul along with other tribes in 406. In 409, the Vandals crossed the Pyrenees into the Iberian Peninsula, where their main groups, the Hasdingi and the Silingi, settled in Gallaecia (northwest) and Baetica (south central) respectively.[5]

1 note

·

View note

Text

Przeworsk is a typically medieval city. Its development falls on the decline of the Gothic. This is evidenced by monumental buildings, ie the former church and monastery of the Order of the Blesseds, now a parish church, the Bernardine church and monastery, the town hall, fragments of defensive walls. In the field of painting, sculpture and the artistic industry there are two frescos in the Bernardine monastery, showing the Way of the Cross, and in the parish church, the baptismal font, Rafał Tarnowski's tombstones and his wife, and the Tarnowski painting from 1490. During the following centuries the artistic preferences of the people and founders changed. They were affected not only by cultural factors but also by economic and social factors. There is not much material evidence of renaissance and Mannerism in Przeworsk. They are made up of a few tombstones and a large, beautiful Mannerist summit erected above the three-sided presbytery of the Bernardine church. The Baroque period left behind the chapel of the "Holy Sepulcher" erected at the parish church and many moving works of art such as paintings, an altar carved and painted on the wall, stalls, chasubles, bells, etc. preserved in both churches. In addition, at the end of this period, a small church and monastery of the Merciful SS was established and a framed building, called tavern. The buildings from the early nineteenth century include the palace maintained in the spirit of English classicism with exquisitely furnished interiors.

0 notes

Text

Roman-Era Weapons Found in Poland

Hidden in a forest of southeastern Poland sat a collection of objects. The artifacts had been abandoned and forgotten for centuries — not anymore.

Mateusz Filipowicz was at a state forest in Hrubieszów when he noticed a rusty item hidden in the leaves, the Lublin Provincial Conservator of Monuments said in a Jan. 16 Facebook post.

Filipowicz picked the rusty item off the forest floor and found several more objects nearby, officials said. The items were mixed with mud and hard to identify.

Archaeologists recognized the rusty objects as a set of ancient Roman-era weapons.

In total, Filipowicz found 15 iron artifacts, officials said. The collection included nine iron spearheads, two iron battle axes, another ax and three mysterious objects that archaeologists tentatively identified as an iron shield holder and pair of iron points.

The weapons dated back at least 1,500 years, officials said.

Excavations of the forest area found no bones or other artifacts, indicating the site was not a grave. Instead, the weapons were likely packed into a bag and dumped into a swamp, archaeologists said.

Archaeologists said the weapons were likely used by an ancient barbaric tribe, either the Przeworsk warrior culture or the Gothic culture. Remnants of both cultures have been found near Hrubieszów.

Officials said the artifacts were taken to the Museum of the Priest Stanisław Staszic, where they will be cleaned, analyzed and conserved. Archaeologists plan to revisit the site where the objects were found during the spring.

Hrubieszów is a town about 160 miles southeast of Warsaw and along the Poland-Ukraine border.

By Aspen Pflughoeft.

#Roman-Era Weapons Found in Poland#Hrubieszów#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire#roman legion

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two thousand years old ironworks village studied in Kanie

Well of unusual design, a number of bloomeries for smelting and remains of half-dugouts discovered archaeologists during excavations in Kanie (Mazovia Voivodeship).

According to the researchers, the site perfectly fits the pattern of other known ironworks settlements located in the Błonie Plains in the western part of the region. It was the second largest centre of mass production of iron in the territories inhabited by the Przeworsk culture about two thousand years ago.

"We found 22 furnaces filled to varying degrees with slag pieces and residue and intense black burn, and two half-dugouts, which contained numerous pottery pieces" - reported Robert Wereda of the Museum of Ancient Mazovia Metallurgy in Pruszków. Read more.

57 notes

·

View notes

Note

(1/3) Hey again, about the ballet, yes I agree it's frustratingly hard to find material about a specific location of the ballet. If it helps, the story is usually set in a town that is decently populated, not very rural like Giselle, but more like a small growing city. Also worth noting: the ballet takes place during a festival, and the second half includes a (dramaticized) wedding. I was thinking of interpreting the festival to be Dozynki (which I am learning more about).

(pasted the rest of your message above to have it all in one place, wish tumblr expanded the character limit)

I think that, after all, it’s a beautiful thing to have such a creative freedom! I’m not a fan of a random mish-mash type of things. But as it comes to the ballet stage costumes as an art, there’s always a degree of alteration the designer must take into account (like the sleeves that can’t limit the dancers’ movemets) and they seem to always create an interesting fusion of influences.

I googled the Coppelia ballet with Natalia Osipova to check the costumes from their performance, and to me they look veeery Hungarian (+ various details from other cultures, and again their bodices are positioned too low - below the breasts - to look Eastern European). However, Galicja didn’t cover any significant parts of Hungary, and I suppose the costume and stage designers decided to simply set it in the vaguely-defined Austria-Hungary Empire (there’s only a few weird elements like an Austrian flag, despite the Hungarian Kingdom had its own, or the inscriptions on the buildings that look like an imperfect transcription from an Ukrainian word for an inn).

If you really want to make it somewhat historically accurate, my advice would be to decide about a precise location first (considering that the location isn’t specified in the original script, I think you’re free to take an advantage of that “vagueness”). Location is the key.

When you decide about the location, keep in your mind that the Galicja was a huge region. It’s generally divided into the Western Galicja with the administrative centre in Kraków which had a majority of the Polish peasants, and the Eastern Galicja with the administrative centre in L’viv which had a majority of the Ukrainian peasants. There were no clear-cut borders between those ethnicities, and in a lot of areas they were mixed. Galicja included also subregions like Bucovina that had a significant Romanian majority and a few Hungarian villages. Generally speaking, specifying a certain part of Galicja alone should make your design process easier.

If you want to portray that ballet on the Polish countryside (in the Western part of Galicja), you still need to decide where exactly to portray the ballet. The Polish culture within Galicja was exceptionally rich, including vast plains around Kraków, the south-eastern plains around Rzeszów, the many different Górale / Highlanders groups, and other areas - roughly all the costumes from the modern Lesser Poland and Podkarpackie voivodeships.

Here’s a rough list of major Polish costumes (from those that had already appeared on my blog) that were located within the administrative borders of Galicja:

Babiogórcy

Beskid Żywiecki

Górale nadpopradcy

Kraków + Wadowice

Kraków East

Krosno

Lachy Limanowskie

Lachy Sądeckie

Lachy Szczyrzyckie

Lasowiacy

Lubaczów

Łańcut

Łącko

Orawa

Pieniny

Podhale

Pogórzanie

Przeworsk

Rzeszów

Spisz + Jurgów

Zagórzanie

Żywiec

There were also many other costumes but I think you might settle down with analyzing those above.

The Jewish people had a long history on those lands, and they lived in majority in the small towns. In the Western Galicja they constituted around 8% of the population in average, but that percentage would be definitely higher in towns and cities (depended on a particular location).

German-speaking people weren’t that widespread (contrary to what the author might’ve thought). They worked mainly as officials, merchants or craftsmen, and a vast majority among them were immigrants or colonists from the late 18th and early 19th century (after the Partitions of Poland). They were prefering the bigger cities and towns, or lived in closed communities, and the German population made barely around 0,3% in total in the Western Galicja. The only historical group of German origins were so-called Głuchoniemcy living in some areas of Podkarpackie voivodeship. They were colonists from c. 14th century invited by the Polish king Casimir the Great, but they adapted the Polish culture and spoke Polish already by c.17-18th century, therefore they aren’t in any means significant for Coppelia’s setting.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archaeologists discover burials from the Roman period in Czelin

Crematory pit and urn grave from the 1st/2nd century AD have been discovered by archaeologists during excavations in the Roman period cemetery in Czelin (Zachodniopomorskie).

Bartłomiej Rogalski from the National Museum in Szczecin , who conducts research, said in an interview with PAP that the form of the clay urn and the specific "toothed wheel" decorating technique are typical for the Elbe area, lying west of the Oder .

According to Rogalski, the ornament on the vessel is in turn typical for the Przeworsk culture , which at that time occupied territories of Wielkopolska and Silesia. "This conglomerate of various cultural trends is symptomatic of Lubusz group" - added Rogalski. Read more.

31 notes

·

View notes