#priest cross sans

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Your meat isn't dead, it's still moving

Hi :D I'm here for another fanfic for @ancha-aus :D

But this time it's for the Ghost & Medium AU !

This fic takes place after Dust met Killer and Cross, and it is now time to meet Horror !

Tw: mention of death, forced starvation, sect, Killer flirting

- Stopping for a little snack ?

Dust's passenger asked as he stopped his van in front of the butcher's shop. He didn't even look at him, knowing he would see Cross grinning at him, well, not Cross, his body yes, but Cross wasn't in his body anymore, Killer has possessed him when he was supposed to be exorcized, and now he followed Dust anywhere he went. Cross was there too though, his spirit sitting on the back of the van, clearly displeased by the whole situation. Ash, Dust's ghost brother, was next to him, squinting disapprovingly at Killer like he always did when he flirted with Dust.

- I'm here for work.

- Oooh can I-

- You can't come.

Dust cut him before he could ask. He heard Killer whine but he couldn't care less, he couldn't take him with him, judging by what the butcher said the ghost haunting the shop wasn't a normal one, he couldn't risk bringing another inside without first making sure that it was safe, aside from his brother but he had a necklace to protect him, and even if it was a normal ghost he really didn't want Killer to bother him.

- You're not alone, you have Cross, talk to him.

He reassured the ghost.

- I don't want to talk to that body thief.

Cross said, still bitter about the whole possession thing. Dust could understand, he would be mad too if someone possessed him to go flirt with a random guy.

- You both stay here.

He commanded as he grabbed all the material he needed to communicate with the ghost, closed the van and went to the shop, Ash following him.

From what the butcher said over the phone this ghost had been haunting his shop for about two months now, they would throw the packages off the counter, slam the walk-in fridges' doors, detach the pigs' and cows' pieces from the hooks and generally just throw food around. Nothing weird so far, just a regular poltergeist, but what seemed off to Dust was that the shop had been there for years and it was the first time something like that happened, and no one had died in or near the shop these past few month, so that meant the spirit came to haunt this particular place, just like Killer did with the last house he was in, and seeing how it turned out, Dust wanted to be extra careful with this one.

The butcher was in front of the door, waiting to greet Dust.

- Ah ! You're here, perfect ! I hope you can do something about this.. haunting thing, I'm starting to lose customers and I can't afford to lose my business.

Dust saluted him with a nod.

- I will do everything I can.

- I don't doubt it. The keys are on the door, you do your things, I have a delivery to make so you can just leave them in the mailbox once you're done.

Dust nodded again, watching the butcher get in his own truck before sighing.

- Alright, let's see who's inside..

- IF IT FLIRTS LIKE THE OTHER ONE I AM LEAVING THIS PLACE.

Ash commented.

- I hope not, Killer's annoying enough I don't need a second one.

He pushed the door open, closing it behind him. The shop was dark, the curtains were down, indicating it was closed for the day. There was still enough light to navigate though and Dust went directly behind the counter in the staff area, as it was where there was the most activity.

- Hello ? I came here to talk, if you're okay with that.

He choose a table to put his radio and ouija board, looking around, there were pieces of meat everywhere, some scattered on the floor, it looked like an animal came to make a mess before leaving. He didn't see anyone. Maybe this spirit wasn't that strong ?

- IT DOESN'T KNOW HOW TO CLEAN APPARENTLY.

- Ash, please, don't be rude.

Ash huffed but didn't add anything, letting his brother do his job.

- Are you in here ? I heard you liked throwing pieces of meat on the ground, if I put one on the table, could you make it move so I know you're here ?

He asked, but the radio stayed silent and the ouija didn't move.

- I'm going to put his steak on the table, okay ?

He bent down, reaching for a steak that was already on the ground. Just as he grabbed it he thought he saw a glimpse of red but it was gone when he looked up. He slowly stood up, put the steak on the table, and waited for it to move.

He didn't wait long, just as he backed up the steak flew across the room and hit the wall before falling on the ground once again. Dust saw a vague silhouette in front of him, a tall and large one, but he couldn't see much more for now. Dust smiled.

- Hello. My name is Dust, glad to know you're here. If it's okay with you, would you mind telling me your name ?

The silhouette shifted, and Dust saw a bright red eyelight staring directly at him, before disappearing. In the distance, he heard a door shut, probably a fridge as he heard the noise of hooks being moved.

- YOU SCARED IT.

Dust frowned, but ignored his brother. He grabbed his radio and board and went to the fridge, knocking on the door to announce his presence.

- I'm gonna come in, okay ? I just want to talk, I'm not here to hurt you or take your food.

He said, assuming that the spirit's obsession over the meat meant they felt like it was theirs. He pushed the door open, shivering at the change of temperature, and closed it again. He could see the silhouette, this time a little more clearly, sitting in one of the corners of the fridge, all curled up. Dust stopped in the middle of the room to leave space for the ghost, sitting down, he put his material in front of him.

- Hey, sorry if I scared you, I didn't mean to.

The ghost didn't move, but they were staring at him. They looked like a male skeleton monster, with one glowing red eyelight and what seemed to be a hole in their skull, which was most likely the cause of their death as no-one could survive such an injury. But why were they haunting a butcher's shop then ? They were dressed with a big coat, some thicc sweatpants and winter boots.

- Would you mind telling me your name and pronouns so I can know how to address you ? You can use either the radio or the board.

The ghost stayed silent for a little while before muttering something, not using either instrument.

- Horror... I'm a man...

He had a deep raspy voice. Dust tilted his head, he didn't expect this spirit to be powerful enough to speak without help.

- Hello Horror, I'm going to ask you some questions, okay ?

He told him. Horror didn't respond, but he didn't flee either, so Dust took it as a sign he was okay with that.

- What are you doing in such a place ? Did something happen here ?

- There's... food...

Horror answered slowly, searching for the right words. Dust let him speak at his own speed, judging by his injury he probably had trouble speaking, no need to rush him.

- Are you here for the food ?

He asked. Horror nodded.

- I'm hungry...

Dust frowned. Hungry ? Spirits couldn't get hungry, they didn't have any body to feed, Dust should know, he had a ghost brother and Killer almost panicked when he heard his, well, Cross's, stomach gurgle.

- Do you feel hungry ? Or do you remember feeling hungry ?

He asked. Maybe this spirit had been hungry before he died and this feeling made him haunt the shop ?

Horror looked down, thinking about what the medium said. Was he hungry ? He couldn't feel his stomach, it didn't hurt anymore either. Was it because he wasn't hungry ? Or because he became so used to hunger that he couldn't feel it anymore ? He had been hungry all of his life, he knew what it felt like, he had felt it so strongly when he was there, in this dark room, but he didn't feel it now... he didn't feel anything... his head didn't hurt... was he... was he dead... ? Was that what death felt like... ? Was it why he couldn't eat... ?

- Heyyyyy Dusty ! Ya missed me ? Of course ya missed me ! Oh ! Who's that with you ?

An excited voice yelled, followed by another, less excited, voice.

- I tried to stop him ! I swear I did but he wouldn't listen !

Dust let out a loud sigh, not even needing to turn around to see that Killer was behind him with Cross.

- I told you to stay in the car.

- Yeah I know but then I thought you might be in danger, so I came to the rescue !

Killer argued, feeling very proud of himself.

- I am not in danger, Killer.

- Yeah yeah anyway, who's the newbie ?

It was no surprise that Killer could see Horror, as he was a spirit too, and Cross had gained this ability too since he wasn't in his body anymore and had entered the spirit realm.

- He.. doesn't look okay...

Cross noticed, seeing how Horror was still looking at the ground, his arms around his knees, not paying attention to Killer who was now very close to him, crounching down.

- I DO WONDER WHY.

Ash sarcastically said, squinting at Killer.

- You invaded his space without his consent.

- Well first of all it's Killer's fault, and second of all he really doesn't look good, and not just because we're here...

- What do you mean he doesn't look good ? He looks fine as hell. ~

Killer said with that particular tone of voice that always made Ash gag.

- Now's not the time for that, Killer.

Dust sighed again, sometimes he really regretted accepting going to Killer's house, he couldn't even do his job properly now !

- You're new here, huh ?

Killer asked, ignoring Dust. Horror looked up at him, only now realizing that two more persons were here.

- What killed ya ?

- Killer.

Dust got up, ready to grab Killer by the hood to drag him outside if he continued to mess with his work. The only thing stopping him from doing so was when he heard Horror answer.

- ... Hunger... I... died of hunger... I think...

He seemed so unsure that Dust's anger almost vanished. This ghost didn't know he was dead, it was obvious now, he wasn't here to scare people, he was here because he died hungry and wanted to eat, not realizing he didn't need to anymore.

- Ah yes, hunger, I know how it feels.

Killer confessed with a serious tone that almost caught Dust off guard.

- But it's okay, you won't get hungry anymore now, you're free ! You can do anything you want and go anywhere you want !

Horror blinked, still slowly processing the new information.

- I don't know... anywhere else to go...

- Aww come on, don't you got a dream destination ? Somewhere you really want to visit ?

Dust searched through his pockets to find his notebook, wanting to take notes on the conversation as Killer was surprisingly getting better results than he did.

Horror shook his head.

- Couldn't go out... needed to stay.. inside the walls... our leader said... outside was unworthy of.. of our presence...

- THAT SOUNDS LIKE A SECT.

Ash commented, and even if Dust would have preferred him to be less direct, he was right, that sounded like a sect. Was Horror in a sect before ? Did he die of hunger because they starved him on purpose ? Or did he go outside those "walls" and couldn't provide for himself ? Was it how he got hurt ?

- I know it must be hard for you, but would you mind telling us more about your.. your leader and the walls ?

Dust asked, trying not to jump to conclusions by calling it a sect, even though it clearly was.

- The walls.. protected us... Undyne was chosen by the gods... she decided who was worthy... and who was not...

- Worthy of what ?

Killer asked before Dust could.

- Food...

Dust frowned, that explained his choice in the place to haunt.

- Did she say you were unworthy ?

Dust asked softly, talking about death could be traumatizing and his goal wasn't to scare Horror, it was to understand his life, and death, better in order to help him rest, but he needed to ask questions for that.

Horror nodded after thinking for a minute.

- She didn't like... that I questioned her way... she said it was a shame... I had been worthy all my life...

- What made that change ?

Horror shriveled down a little bit more on himself.

- My brother... wasn't worthy...

No one responded to that as they could all imagine what happened. Horror continued.

- We had a room... for the unworthy... couldn't have food when... when inside... couldn't go out...

Dust looked up from his notes. They starved them. They starved Horror's brother and then they starved Horror, and he died of hunger.

- That must have been horrible, I'm sorry it happened to you...

Horror looked up at him.

- But Killer is right.

It pained him to say that, and it pained him even more to see Killer's smug expression.

- You are free now, you don't have to stay here.

- Can... go with you... ? Don't want... to be alone...

- Wh-

- Oh my God of course you can ! The more the merrier come on ! We'll have such a good time together !

Killer responded with excitement before Dust could even say anything.

Horror looked at Killer for a second before smiling hesitantly, quite relieved, and finally getting up as Killer already stood up. He was... tall. Like, very tall. But that didn't stop Killer from smiling brightly.

And then Dust felt it. He felt a link forming, a thread connected to his soul, the thread that formed between a spirit and the place, or person in this case, they haunted. The third thread, not counting Cross as he was still connected to his own body.

His third ghost.

He came here to exorcize the place, and instead gained another ghost.

Well... at least the butcher would be happy.

...

Where was Dust going to find enough place for everyone ? Why did it have to happen to him ?

He already felt a headache coming. God, he really regretted meeting Killer.

#original post#fanfiction#utmv fanfiction#ghost & medium au#dust sans#killer sans#cross sans#horror sans#dust!sans#cross!sans#killer!sans#horror!sans#ghost killer sans#ghost horror sans#priest cross sans#medium dust sans#ghost papyrus#dusttale#dusttale papyrus#horrortale#xtale#something new au#ash papyrus#bad sanses#bad sans#bad sans gang#bad sans poly#murder time trio#mtt

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

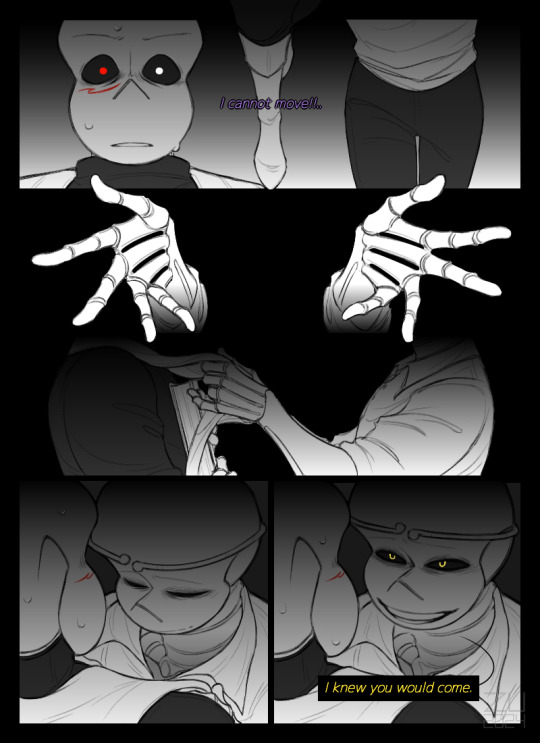

<– • –>

#zu art#comic#x-orcist#love and passion#priest!cross#demon!shattered#cross!sans#shattered dream#undertale#undertale au#utmv#drawing Dream from below so that his shirt' collar looks high: omg dark cream Shattered hello hiii <33#seeing his bones feels so vulgar though like cover them up shatty— ///#a spider skeleman ùwú

883 notes

·

View notes

Text

summer recap/favourite fics/fic recommendations for the first half of 2024!

Pretty flushed by @holybibly

♡ 2 parts, wolf!hwa x rabbit!reader x wolf!joong, a/b/o, smut smut smut, a little dark

Industry baby by @kitten4sannie

♡ mingi x reader x joong, rock band au, cuckold play, bf!mingi and bandmate!joong

Arriba! + Freak! by @teeskzagain

♡ f!reader x joong, yunho, san, woo and mingi, college au, a lot of smut, sex under the influence, ateez are absolute pervs, "the boardgame made us do it"

7 minutes of compensation by @k-hotchoisan

♡ hwa x f!reader x yunho, frat!teez, threesome

in the wings by @sanjoongie

♡ rapppers hwa and joong x f!reader, backstage pass, smut, double penetration, groupie au

Case: It's you by @potatomountain

♡ ot8 x f!reader, e2l, police au, workplace romance, investigative and horny ;)

Inception by @remedyx

♡ a repeat from the last list, but it's sooo good, go check it out!!

The happiest girl in the world by @holybibly

♡ camboy!hwa x f!reader, private call, smut, streamer x fan au

February filth fest 2024 day 13: Uniform by @sanjoongie

♡ new captain!hwa x former captain!reader, mutiny au, scifi, mean dom hwa, humiliation and degradation

February filth fest 2024 day 21: aphrodisiacs/overstim by @sanjoongie

♡ alien!joong x human!reader, alien poison as an aphrodisiac, oviposition

Ugh, as if by @ennysbookstore + Ugh, as if - bonus

♡ punk!joong x f!reader, joong works with leather, cute and hot, joong helps reader overcome insomnia with some good old-fashioned orgasms

Look after you by @mingigoo

♡ musician!joong x nurse!reader, a little angsty, but with a sweet ending, smut

Plug & Play by @bangtanintotheroom

♡ guitarist!joong x f!reader, rock band au, s2l, backstage sex, reader is horny and hongjoong is hot

this ask by @nateezfics

♡ sex with angry joong, bratty reader

Honey and blood by @nateezfics

♡ vampire!joong x maid!reader, dark but sweet, smut with feels

10:11 : féconder by @yeosgoa

♡ assistant!joong x witch!reader, academia au, accidental aphrodisiacs, desperate joong under the influence of a sex potion

cross my heart by @doitforbangchan

♡ brother's best friend!joong x f!reader, dark, yandere joong, he's very manipulative, dubcon/noncon, sex under the influence

February filth fest 2024 day 4: public sex by @sanjoongie

♡ cowboy!san x wise woman!reader, wild west au, san is injured, san is head over heels for reader, save a horse ride a cowboy ;)

no hesitation by @daemour

♡ fratboy!san x f!reader, bff2l, college party au, misunderstandings, fools in love, smut

February filth fest 2024 day 23: breeding kink by @sanjoongie

♡ kitty hybrid!woo x f!reader, rut sex, cumplay, bratty woo

deliver us from evil by @holybibly

♡ priest!woo (or is he???) x f!reader, hierophilia, sacrilege, church sex, very dark, rough sex and humiliation

IT's You by @shinestarhwaa

♡ debate team au, college au, e2l, mean woo, rough sex

Right here by @0097linersb

♡ bff!woo x f!reader, pervy woo who wants to fuck his bff, very sexually frustrated reader

My library | BTS fic recs

#kpop fic#kpop smut#kpop fic recs#ateez fic#ateez smut#ateez fic recs#ateez x reader#seonghwa fic#seonghwa smut#hongjoong fic#hongjoong smut#san fic#san smut#wooyoung fic#wooyoung smut

611 notes

·

View notes

Text

These are some PPCU fics I have read and enjoyed this past month and would like to recommend. Some new. Some Old. All have smut. I am going to be doing a monthly rec list going forward in an attempt to read more and help reblog and support some amazing authors out there. Please show them some love. Read all warnings! Not everything is for everyone and that is ok. Please always comment AND reblog fics you enjoy to show love to the authors 🖤

Joel Miller

Feelings on Fire // @pedropeach You're back from college for the summer, staying with your devout catholic parents in your childhood home while they order you around and try to keep authority over you. as an act of rebellion you ask your new neighbor mr. miller to teach you how to play guitar, but it turns out there's a lot more he wants to teach you.

But He’s The One I Want // @wheresarizona All you needed was to see if your dad’s friend, Joel, had a spare key to your father’s house. Instead, you get railed within an inch of your life on Joel’s couch.

Only then, I am good // @joelsdagger You have a bad day in which it makes you question your worth. only joel can make you see the truth. daddy jackson!joel x f!reader

'Tis thee Season // @joelsdagger You’re back in town for christmas, and it’s been months since you’ve seen your boyfriend, joel miller. and he decides to make the most of the brief window of time you have together or, joel fucks you after taking viagra.

Subscribe // @joelmillerisapunk When Joel accidentally stumbles upon your only fans he convinces himself he's only subscribing to help you through college. And then you send him his top-tier subscriber personal video and he's fucked because you don't even know it's him your dad's best friend

Inhale, Exhale // @sp00kymulderr This world is not made for intimacy and both of you know it.

Dance With Me, Darlin' // @milla-frenchy You go to a club and want to fuck. So does Joel

San Angelo // @macfrog It's the summer of two thousand eight. after two weeks following his little brother cross-country on the back of a harley, Joel follows him through the doors of a dive bar where fate delivers him to you.

General Marcus Acacius

Prima Nocta // @fuckyeahdindjarin Tomorrow, you will marry your husband-to-be. But tonight - it belongs to his father.

Fit For A Goddess // @ozarkthedog You wear Marcus’s gold laurel crown while he worships you.

Ezra

Little Wren // @schnarfer Wild. West. Priest. Ezra. That’s it, that’s the idea.

The Beast Within // @aurorawritestoescape Trekking the Green with his new partner, Ezra is overtaken by his need to have you. While you sleep in the camping tent, the animal within Ezra pushes him to act on his desires. Little does he know, you’ve wanted him as well.

Frankie ‘Catfish’ Morales

Nut vid with the sound on // @syd-djarin You accidentally send Frankie a text that he wasn't supposed to see.

Javier Pena

Office Hours // @itwasntimethatdidit40 You should concentrate on work. But you can't do that with the charming bastard you share the office with in front of you. Why not find a more fun way to spend your office hours?

Banner by me. Dividers by @saradika 🖤

#please signal boost to show these authors love#rec list#pedro pascal fandom#pedro pascal#ppcu fics#pedro pascal fanfiction#joel miller smut#joel miller#ppcu recs#ppcu fandom#smut recs#x reader#general acacius#ezra prospect#javier peña#frankie 'catfish' morales#pedro pascal fic#pedro pascal x reader#ppcu fanfiction#pedro pascal character

284 notes

·

View notes

Note

Salome!

"La Belle Dame sans Mercy" ("The Beautiful Lady Without Mercy") - A ballad by John Keats

"The poem is about a fairy who condemns a knight to an unpleasant fate after she seduces him with her eyes and singing." please

This screams Knight!König x Fairy!Reader to me.

I just know König would gladly die by the hand of such an ethereal being.

"She looked at me as she did love, and made a sweet moan."

"And sure in language strange she said—'I love thee true.'"

That’s it. Thank you.

I swear this artwork kills me everytime I see it....

Ok this became the silliest fairytale ever 🩷✨️

CW: Historical AU blending with mythical/supernatural AU. König being a dreamy mess of a knight who doesn't fit in "normal" society. Reader is part of faefolk. Heavy Arthurian Romance vibes.

König returns to the castle one day. The son of a great liege lord, a warrior through and through, but some people say he should’ve been a poet: so dreamily he looks beyond the battlements at times, sighs after drinking too much wine, stares off into dark corners of the room while tending to his sword and armour as if he can see little pixies dancing there.

His siblings sometimes hit him on the back of his head, or wave a hand over his eyes when he’s about to slip into the fairy world, a forgotten plane that is not supposed to reach the castle. But the castle stones were taken from the moors and the woods, the old land not bending to the priest’s will no matter how many crosses they brought here. Fragile souls are wanton prey for the elves and the fairies who would take them to their land the moment they drop down their guard, and only prayer and fasting hold them at bay. In the fairylands, there is no toil or sorrow; the food is golden honey and wine, the dance and love everlasting, and the fae girls more beautiful than any human maid.

It sounded too good to be true, and it was: God had created men to work and women to give birth, and all the land was theirs to use and cultivate, it was not made to simply run and frolic upon. Some say that these were just old tales and that Christ would banish these creatures away, turn the land to yielding crops and tame firewood.

But some still believed.

When he was a child, the mighty son of the feared lord took porridge and almonds to the woods. “For the fairy people,” he said with bright, trusting eyes. Stole food from under the mistress’s nose, and no one ever dared to say anything about it.

But when this nonsense carried on to adulthood, people had to intervene. There was work to be done, war, harvest and building, and no matter how many coins this man paid to the visiting bards, it would never turn their stories true.

His arm was strong and his strike was true, but his head seemed to be filled with dandelion wine, even when he hadn’t been drinking. Sighed after this maiden or that, wished to travel to foreign lands, courted every nobleman’s daughter who visited the castle, but no one ever took him seriously.

This man had to watch how lady after lady chose some other valiant knight as their husband, some men whose heads were not filled with fairytales and dreams. They did flirt with him, for who could’ve resisted the temptation of making this giant a little sweaty under all that armor? Armor that demanded plate for two people, and a smith who had the talent to forge such a beastly thing.

Nevertheless, he was always left without a warm embrace, and so he was usually found outside, looking at the full moon or spending time in taverns, choosing the company of thieves and rascals over his serious kin.

And now he has returned from the woods, having been gone for months.

People thought he had finally left to fight for some other lord, posing as a simple footsoldier, a disguise that would relieve him of his tedious duties as a knight. Or to court some “lovely peasant girl” he always talked about – such talks were usually crushed by his father, demanding him to be sensible for once in his life.

But he doesn’t prattle about peasant girls now, nor does he ramble about screaming ships at the bottom of the sea. He doesn’t hold a speech about forgotten stone circles in the forest, the ones that already grow moss. No, he has finally lost it completely.

His eyes are wild, as is his hair; his armour is nowhere to be seen, and his sword is without its sheath. He doesn’t talk about what he saw in that forest to anyone, nor is he willing to tell where he has even been these past few moons.

He seems very shaken when he’s told they were worried he wouldn’t make it to the May Day feast, and asks for how long he was gone, drives a hand through dishevelled hair when he hears that he was away for three full months.

“Three months…” he mutters to himself, then leaves to his room, the huge sword dragging against the stone floor as he goes. He has always, always made sure it wouldn’t dull, but now he’s treating it like it’s become a part of him, confused and lost.

He doesn’t eat, hardly speaks after that.

The food tastes like ash, he says, and the ale tastes like bile. But the following evening, when his mother orders someone to pour her poor son some more wine, he looks up helplessly like a child.

“I have to go back,” he says.

A clamour arises, huffed exclaims of “What on earth is he on about” and “Sir, you only just got back!” His father rises from his chair and orders him to stop this nonsense at once. But this time, there is no embarrassed sweep of hand through hair, no red colour that rises on this peculiar knight’s cheeks. His lips only make a thin line before he rises as well and leaves the hall with a weight on his shoulders and dark determination in his stare.

At the stables, a stout Moorland pony and poor stable boy get to witness the drunken bawls of a forlorn knight. The wine sack almost slips from his hands to the dirt as he slumps against the timber of the stall, distorted face coming to rest against a wide, shaky palm.

Luckily, a friend of his knows where to look, and the stable boy sneaks into the shadows, slightly scared of the sorrow of such a big, intimidating man.

But even the companion who always listened to every enthusiastic story since they were kids and ran across the moors, throwing little rocks at his father’s soldiers and laughing when their helmets made a funny clinky sound, can not understand the drunken babble that comes out of König’s mouth this time.

He starts from the middle, which is highly unusual, and talks in strings of sentences that don’t make sense. “She was real, I just know it,” he repeats, over and over again in the middle of confessions about how beautiful she was, how her hair was like the softest spun yarn, her body incredible, naked and wild when she came to him. That her laugh was like the chime of little bells or the sound of the loveliest harp, a song on its own when she walked to him.

She was fascinated with his sword, especially the pommel and the handle interested her, and the curve in the middle of the blade she brushed with her fingers as if it was an entire vale.

He had never seen a woman touch his sword like that… They were never interested in such things, but she was, and she asked him so many questions.

Had he ever felled a tree?

Did he like squirrels?

Were his thighs as hairy as his chest?

She took him down the river, or he followed her; he can’t remember. Her step was so light it didn’t make a sound, and the moss seemed to turn brighter every time her little foot stepped on it. Her hands were tiny too when she wrapped them around his neck, pressed her body against his, and kissed him until there was nothing left of him: no helmet, no sword, nothing but sun and her, her hands and her lips.

Her mouth was still on his when she whispered she didn’t like his armour because it was so hard and rigid and cold, oh, she wondered if there was a man inside there at all.

So of course he showed her.

She giggled at the sight of him, especially his thighs, knelt down on the moss to see how hairy they were.

And would you believe the way she touched him then? It makes him heady even now…

Yes, he took her. But not the way a man takes a woman. She came to straddle him and laughed again, and the things they did together… He can’t even speak about them, but he knows the sun always shined when they rolled on the grass. Her giggles and moans surrounded him, her soft little thighs were stronger than they looked, her breasts so round and soft, so perfect he swore he had gone to heaven.

He bathed in her, with her, all day long. And the nights… You wouldn’t believe the nights: there was song and dance and more giggling women, and also a man dressed all in leaves, so big and thick he first thought he was a tree. An old king, she said, nothing he should worry about. And the wine tasted like summer and honey and gold; it was red, perhaps, but also like sea amber and sun…

She fed him flowers and laughed, caressed his face and said he’s the biggest and hairiest human she had ever seen. She let him lick honey from her fingertips and caressed him with heather and ivy, opened her mouth before feeding him a soft, sweet piece of cake, showing him how he needed to open his mouth as well if he wanted it on his tongue.

She kissed the crumbs from his lips and trailed a finger down his chest, all the way down, until…

Oh, he can’t talk about it.

It was better than he ever even imagined: better than the stories they tell in the taverns. It was like his wedding night, over and over again, it was like he was Lancelot, and she was his Guinevere.

No, no, she was not an enchantress, although everything about her was enchanting... All the stories came alive with her, even the moon was bigger than anywhere he’d ever seen, the deers ran past them while they made love, and the birds sang even at night.

He told her he loved her, but she didn’t know what it meant. When he explained it to her, she looked at him gently, so gently…

He cried from joy then, but she never mocked him. She only said it’s a sign that he’s hers. That he will never forget her. She said he’ll always find her, even when he’s old: she will make him young again. He’s welcome here if he wants: she has so many places to show him.

He thanked all the saints for having found her, Saint George and Saint Mary first, but stopped when her little brows furrowed with sorrow. Her eyes, filled with starlight and love, turned so sad that his heart couldn’t bear it, not for one beat.

The sea is far wilder here: he should come and see the ocean as it was at the dawn of time. The ivy is so strong you can use it to climb the trees and see the whole world from atop the tree, the whole land, covered in forest, such as it was before humans came. There’s no smoke or fire or war: just green everywhere, wild rippling streams and honey bees and berries and fish for everyone who ever feels hungry... They can make love day and night, and she’ll teach him all the songs of old. Humans only remember bits and pieces, but she knows how things really happened, she can tell him everything about heroes, kings and queens.

She said she wanted to sleep, and so he took her from the feast and laid her on the grass… She might’ve sung to him, he can’t remember, but it was like an angel’s caress all over him, somber and sweet before the dreams took him, a dream within a dream.

He slept for ages, it seemed, saw so many dreams, each more beautiful than the last until he woke up and saw that the forest had turned grey.

There was no maiden in his lap, no dance and song in the distance, no scent of flowers and dreams and springs to be found. The sun was up in the sky, but it didn’t paint all the colours with gold or fill the streams with light. The forest was half dead to him, just old, thick trees around him, a green-grey forest floor and a shaggy squirrel who chirped and squeaked at him as if it was his fault that the fae folk were gone.

He searched for her, called for her, but she didn’t answer, and how could she have? He didn’t even know her name. He only knew how lovely she felt, how soft her hair was when it fell to cover him like a veil, how adorable her sighs and tiny little gasps were when he filled her, over and over again.

His armour was nowhere to be found, and his sword was somewhere downstream, half covered with leaves and dirt, rusty and beaten by the wind. It was early spring when he came here; the land was still barren and grey, but now, everything was green. Still, it was not the green he wanted. It was not the green that filled his vision entirely, bright, blooming green that pulsed with lush joy. It was just… earth and grass and dirt.

So you see, he has to go back. He has to find her, whatever it takes. She promised he could always come back… She promised…

He cries once more, head bowed and mighty shoulders trembling from the force of his sorrow, and it is no use to tell him that the fae folk are evil. That they’re from the Devil and only want to make good, decent men like them forget. Forget their duty, their laws, their Christ.

It’s no use to tell him that it is not natural, the place he has seen. No doubt he has been somewhere, but it cannot be anything good… No man can survive on flowers and spring water for three months; they cannot frolic with the faeries for days on end without losing their mind and soul.

And König is already lost; he was lost since he was a child, rambling about how he received flowers, sticks and stones as tokens of the faefolk’s gratitude because he brought them food.

He tries to tell the boy who never grew up, the mightiest man in this kingdom, the dreamiest knight there ever was, that he needs to return to the real world. No fae woman would have him as a husband, they are only after his soul. But surely some human lady would take him into her bed, think about it, for God’s sake, please... He has duties here, people who love him, his father would make him a lord if he only put himself together. What kind of knight would abandon his sword, helmet and armour for the sake of an elf who despises the saints...?

But in the morn, König is gone.

His rusty sword is on the floor, the wooden cross taken off the wall. There lies a honeycomb and a flower on his window, a blossom so sweet it cannot be plucked from any field around here. Too exotic and bright, especially when placed atop the rough, grey stones, it looks like it could never wither from how beautifully it blooms.

The peasants now tell a tale of a man that haunts the woods: a huge giant dressed all in green, donning a leaf cloak of some sort and a beard that grows ivy. But they say he is not evil: he only shows himself to hunters who are about to fall a deer, or children who remember the land with little gifts.

Old men say they saw a green man when they were kids and brought bread and milk to the faeries, they swear to this day they saw a man who greeted them with a smile. And when they looked again, there was nothing but a tree where this giant stook, a young oak, sighing with the wind...

489 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wip Wednesday

I was tagged by @bidisasterevankinard and @typicalopposite for this one (thank you my loves!). I have gotten quite a few things that I'm writing, and y'all had me motivated for new things with your asks, so thank you sooo much for that! ♥ But for this one I'm going with my priest!Tommy AU, so here's the first scene complete. If some stuff looks familiar it's bc I posted snippets a few days ago!

Buck loves LA, but he hates days like this one, where it feels like the whole city is a greenhouse. The heat is sticky and humid, clinging to his skin and making him sweat in his uniform. All he wants is a cold shower and a minute to breathe. And, okay, maybe a cold beer wouldn’t be a bad idea.

Instead, he’s crammed in the back of the 118 fire engine, heading to San Pedro for one more call. And Buck loves his job, he does, but they’ve been on back-to-back calls for the last three hours.

“Christ, I feel like I’m gonna melt” He whines, and Eddie smirks at him from the front seat (he had won rock paper scissors fair and square, the bastard), pushing his sunglasses up his nose. His Texas-raised ass does just fine with this horrible weather, and Buck hates him for it.

“Yeah? Better start working hard to go to heaven then, cause you would not survive the eternal flames” He quips. Buck crosses his arms, too stubborn to let himself be influenced by the collective chuckle.

“I already work hard to go to heaven, don’t I? Saving lives and stuff” He says with a shrug, absolutely not pouting, thank you very much..

“I don’t know, Buckaroo.” Chim says, a playful smirk on his face. “When was the last time you set foot in a church? That’s supposed to be a big deal for the guy upstairs”

“Well, if that’s the dealbreaker, we’re all screwed” Hen says dryly, even though she doesn’t look particularly concerned. “Except for Cap, of course.”

Bobby chuckles from the driver’s seat, taking a turn to the right and stopping the truck.

“Well, here’s your chance to make up for it” He says, and Buck comes down from the engine to find out they pulled up to a small stone-walled church.

The doors are open, and most people are outside or at the very back of the church, chatting agitatedly, their eyes widened as most people when they find themselves witnesses to a 911-level emergency. It’s a sizable crowd, he thinks, considering it’s a Wednesday afternoon (which, as far as his Episcopalian-raised knowledge goes, is not a church day).

As they rush up the church’s steps, he notices half of the crowd are the usual elderly ladies, but half of it are people around their 20s and 30s, and a few teens, which surprises Buck. They’re all whispering fiercely to each other and keep stealing glances inside the church. One of the ladies approaches them, relief clear in her eyes.

“Oh, thank God you got here so fast!” She says, wringing her hands together. “It’s Mrs. Bellini, you see, she has low blood pressure, and this weather…”

“Ma’am” Bobby cuts her off as gently as possible. “Were you the one who called 911?”

“No, it was father Kinard.” She clarifies, leading them inside. “He’s already tended to her forehead, but he didn’t want to risk moving her until you arrived to check her situation.”

The church is relatively small, but the ceiling is high, and their footsteps echo against the walls. It’s a lot cooler inside, and Buck lets out an involuntary sigh of relief as they get out of the intense sunlight.

The woman leads them to one of the front pews, where they find another lady who’s sitting down, looking pale and sheepish. There's a white gaze pressed against her forehead, and a small red stain seems to have formed against it. Sitting by her side is a man dressed in white robes, a green-colored long scarf-looking thingy around his neck.

He stands up when they approach, and Buck’s taken aback, because he’s ridiculously tall; a little taller than Buck, even, and that’s no easy feat. His features are sharp, a jawbone that could probably cut through glass, and he has a cleft on his chin (why did Buck notice that, he wonders? Is it weird to notice a priest has a cleft?). He’s looking at them with widened blue eyes that are filled with concern.

“Father Kinard? I’m Captain Nash.” Bobby says, and the man nods sharply, his stance almost militarily. "Can you tell us what happened?"

"He is exaggerating is what happened" The woman quips, her voice a little trembling, but her glare towards the priest is very firm. Father Kinard, however, doesn't seem intimidated.

"Calling 911 after you passed out and hit your head is not exaggerating, Gloria, and you know that" He says gently, then puts a massive hand on her bony shoulder. "I'm your shepherd, I have to make sure my sheep are doing alright, don't I?"

Buck smiles a little at that; it shouldn’t sound that endearing, but it does, and even the lady seems convinced, because she shakes her head resignedly, and doesn’t protest when Chim takes her arm and wraps the pressure cuff around it.

“She fell unconscious during service and hit her head on the pew.” Father Kinard elaborates, still looking at Mrs. Bellini worriedly. “I figured the heat brought her blood pressure down, so I asked everyone to step outside and called 911 immediately. I applied pressure to the wound and it seems to have stopped the bleeding. I made sure to keep her awake and she’s not showing any signs of confusion or dizziness.”

He knows it’s not polite to stare, but Buck can’t help himself. It’s not common for someone to give them this level of information with so much calmness when they arrive on a call. Usually they try to gather what little snippets they can through tears, yelling and fainting over the sight of blood. But father Kinard is collected and eloquent in what he says, and Buck's astounded.

“And you're right, her blood pressure is a little low. The wound looks fine, though.” Chimney says, gently removing the gauze to inspect the cut. “Wow, looks like your priest cleaned this up real well, didn't he, Gloria? My job is already done for me.”

“Father Kinard is great whenever anyone gets hurt.” Gloria gushes, and the priest blushes under the attention, shrugging sheepishly.

“I had first aid training in the army.” He says, and when they all turn to him with widened eyes, he gives them a wry smirk. “Which was obviously before I joined the seminary.”

“Well, you were trained well, father.” Hen says approvingly, inspecting the wound herself and dabbing at it with a cotton swab covered in anti-septic. Gloria flinches a little, but sits still as Hen gets it cleaned and then places a band-aid over it. “This won't need stitches, it's very superficial. How are you feeling, Mrs. Bellini?”

“Oh, I'm perfectly alright now.” She says distractedly, her eyes turning back to her priest. “But I am so ashamed you had to stop service because of me, father! I'm very sorry! And for such a small thing too.”

“We’re lucky it was small, but it could have been bad. I wouldn’t risk it.” Father Kinard says patiently. “And don't worry about the service, Gloria, it was after Communion; we'd already done the greatest bits anyway.” He winks at her, a blinding smile on his face.

Buck doesn’t get the joke, but apparently it’s funny, because both Eddie and Bobby chuckle at it. Chim is removing the cuff from Gloria’s arm and patting it jovially.

“Well, looks like you’re all set, Mrs. Bellini.” He tells her. “If you experience any dizziness or headache, you should look for a hospital, but otherwise, you’re fine.”

“And thank God for that!” Father Kinard adds with a smile that makes his eyes crinkle, squeezing Gloria’s shoulder with genuine affection. “And thank you, first responders, as well. Come, I’ll walk you out before giving Gloria a lift home.” He says, and then strides along them to the back of the church, the smile still lingering on his face.

Buck has a hard time reconciling this laughing priest to the buttoned-up, serious-faced ministers he knew in childhood, from the few times his parents made him attend church. This man is full of joy and confidence, Buck can tell right away, and he just thinks he’s so cool.

“You quite literally have nothing to thank us for, Father.” Bobby adds warmly, smiling at Kinard. Buck knows his captain has a close relationship with church, and he seems completely comfortable striking up a conversation with the priest. “You had done half our job for us before we were here.”

He shrugs modestly once more, walking alongside Bobby, and Buck is irrationally envious of his boss for a second or two. They stop by the church’s entrance, and the man extends a hand to Bobby.

“Thank you, captain…” He says, trailing off, and Bobby firmly shakes his hand, smiling warmly.

“Nash. Captain Bobby Nash. Your blessing, father.” Bobby asks respectfully, and the priest makes a cross sign over his head.

“God Bless you and your team, Captain Nash. May He keep you safe in your very necessary jobs.” He says warmly, and then turns to Hen. “And thank you, firefighter…”

Buck watches in increasing despair as her, Chim and Eddie introduce themselves to the priest, shaking his hand, and realizes that soon it’ll be his turn.

He thought the church was cooler than the outside, but all of a sudden he's feeling hot all over again. Should he ask for the man’s blessing? He didn’t offer it to the others, and they didn’t ask, but should he? Is he even allowed if he’s not a Catholic? Does he even want the man to touch his sweaty forehead?

And then the priest looks at him with that crunchy smile, an inexplicable blush creeps up to his cheeks. Buck thanks God - yes, he’s fully aware of the irony, and he does not find it funny - that he can blame it on the heat and his heavy uniform (never mind that father Kinard's clothes also look heavy and he's still perfectly composed, but Buck definitely won't think about how he'd look all sweaty).

“Thank you, firefighter…” He says, trailing off and extending a hand, and it takes Buck a second to realize he's supposed to shake it and offer his name (not his phone number. Definitely not his phone number).

“Evan. Buckley. Buck!” He blurts out like a complete idiot, and wonders if it's wrong to wish for a five scale fire so they can rush out of there.

Father Kinard raises an eyebrow at him, a smirk on his curved lips. That's when Buck notices he's still shaking hands with the man, and he lets go clumsily.

“My, that's a mouthful” Kinard says, and Buck almost blurts out that he has something else that's a mouthful before his eyes clock the white collar around the man's neck.

As it is, he just snickers awkwardly and mutters a goodbye, his voice high-pitched and strained.

Buck's at the truck before anyone else, mentally preparing himself for being teased all through the shift they just started.

His only saving grace is that, as much as he made a complete fool of himself in front of father Kinard, it's not a problem. Buck'll never have to see the man again, will he? So it's not like it matters.

Naturally, the priest shows up at the station the next day.

Np tagging @agentpeggycartering @unhingedangstaddict @fairytalegonewronga03 @laundryandtaxesworld @mmso-notlikethat and whoever else would like to do it!

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guilty Pleasure - Follow You (Part 2)

✟ Pairing: Choi San x female reader ✟ Word count: 6k ✟ Warnings: cursing, suggestive, mentions of death, blood

✟ Summary: You go back to your hometown for the summer vacation, not expecting the small town's priest to be a total eye candy. But he seems to be hiding dark secrets underneath his holy façade.

Will you find out the truth?

✟-First Part-✟

✟ A/N: Heeyy, so here is the long-awaited part 2 of this story. When I first wrote it I would've never thought it was going to head this way, but it happened and we finally know all the dark secrets of Priest San and why is he acting like this. Also, Yunho and Mingi appear in this story as well, and they are from @bvidzsoo's Who Am I fanfiction, it's happening in the same world but the mention of it is just slight. I find it funny and exciting to write in the same world lol, as in the future that is going to happen more often if she is in hehe. Anyways, read part 1 before reading this to understand everything. Tyy, byee! (Also I'm obsessed with this song again, and it matches the vibes of the story so I recommend listening to it)

I was sitting on the church’s brown bench again as I watched the familiar face who was standing in front of the altar with the Bible in hand and a rosary strolling around his veiny hands the familiar cross hanging on his chest, as he was preaching for the people who came to the church on a bright Sunday morning.

People need to hear some reassuring thoughts about their God so they are going to feel less burdened about the sins they have committed. As if going to church will liberate them from the bad things they all did. Including me, that had the biggest sin anyone had in this church.

And that was—sleeping with the priest who was standing in the middle of the church, trying to motivate the people who came and prayed for their freedom. His sharp but innocent-looking eyes never met mine. Maybe he felt guilty about the sins we committed or he was pretending like I did not exist.

Two weeks went by since that night. And I barely saw Choi San, the priest of the town I grew up in, well he wasn’t a priest, he just pretended to be one, because he had some dark secrets that he did not share with me. After we slept together—some not-so-innocent images popped up in my mind, as he looked down at me, hovering over me, whispering some dirty thoughts into my ears that made me commit any sins that existed. The way his hands ran through my thighs up and down as he made me feel good with a burning desire in his eyes. That night I just cut all my sanity and gave in my guilty pleasure, and so did San—But after that night we did not speak. We had met a few times at the store or at the servings he held, but he pretended like nothing happened and it made me feel uneasy.

Why did he pretend like nothing happened? Was I just a one-night stand to satisfy his needs as it was rare for him to find someone who is in for a fuck with a priest? But in reality, he wasn't even a priest and I still did not know what he was doing here, and why he pretended to be one.

And as I watched him standing in front of the altar, the hall as quiet as the church's mouse, in his long black vestment his eyes observing the people sitting in front of him, I had enough of this game and I needed to talk with him.

When the mass ended, I waited until the church emptied, pretending to pray a little longer. I needed this moment, especially since my thoughts during the service had been less than innocent. Once everyone had left, I stood up and made my way to the vestry room where San always prepared for the mass.

As I entered the room, I saw San speaking with an old man. He was smiling, his dimples showing—a rare sight since he was always so serious with me. His hands rested on the old man's shoulders as he reassured him, promising to pray for the man's sick wife. It was kind of him, revealing a caring and warm side to his personality. But I knew it was all an act. He fooled these people with promises he couldn't keep because he wasn't the person they thought he was.

When the man finally turned, I smiled at him and bowed a little when he passed by me, leaving the two of us in the room. San just glared at me with his sharp eyes, his dimples disappearing the moment the old man left the room.

"Hi," I said as I walked further inside leaning against a table that was full of crosses and Bibles, on the walls there were a few glorious paintings and a closet in the corner of the room where the priest's vestments were hanging. I looked at San with crossed arms in front of my chest.

"Hey," he said, not even meeting my eyes as he turned his back to me. He began taking off the black vestment he was wearing, revealing an ironed white shirt and black pants underneath.

"Why are you avoiding me?" I said as I stared at his wide shoulders where my nails drew blood a few weeks ago.

He folded his black vestment and put it into the closet. Then he turned around to face me as he leaned against the closet mirroring my position. His eyes scanned me up and down. "I'm being watched. I have to pretend everything is normal and fulfill my priest duties," he said in a low voice, his expression unreadable.

I scoffed. "So, I do not deserve at least an explanation?" I lifted my hands questioning him. "You can't keep fooling these people, they really trust you San. Some people would give their life into your hands."

He pushed himself off the closet and slowly approached me with predator's eyes. "I know, I hate to do this, but I have to. I can explain everything. Let's meet at the cemetery tonight." He said as he stood in front of me, he hovered above me, making me feel small. His eyes, burning with intensity, stared into mine, lighting up even in the dimly lit room.

"A cemetery? Really?" My brows furrowed in disbelief.

"Yes, I want to show you something." He stepped closer to me, even though we barely had space between us, his hands squeezing my waist tightly.

"First you kidnap me to an abandoned mansion, and now you want to take me to a cemetery? Are you planning to hide my body in a used coffin?" I folded my arms in the narrow space between us.

He hummed, leaning close to my face, his lips brushing against mine. "I want to do other things with your body, and they're far from innocent," he whispered as his thin lips moved to my bare neck, leaving slight kisses along the way. My lips parted, my body growing hotter, and my heart pounded with uncontrollable desire. I gripped the table behind me, trying to pull away, but he held me in place, not letting me escape.

His hands on my waist pulled me flush against his body, one of his hands traveling up to my jaw as he held it and pulled me closer to his parted lips. "You are my guilty pleasure." He whispered the words onto my lips as his thumb traced over the bottom of my lip. I couldn't control my body or my thoughts, so I just gave control to him. His familiar candy-like scent drove me crazy, making me lose my mind.

Then I felt his lips crush onto my lips, which immediately parted letting his tongue in as it discovered my mouth. This feeling was too familiar yet too strange. I felt like all of this was wrong, I didn't know anything about him, yet I was here kissing him like he was the love of my life.

His lips moved against mine, meanwhile, his hands discovered my body that was flushed against his, I wrapped my hands around his neck like it was in a script of a movie, all of this felt so natural but inhuman at the same time. While he was kissing me, his hands traveled down to the back of my tights just to lift me to the table, swiping the things off from the top so I could sit. He was standing in between my legs that I wrapped around his small waist. His hands brushed against the top of my thighs up to my back where his hands ended up in my hair as he ran his fingers through my dark strings.

The desire that lit my heart in that moment was endless, I felt like it could never burn out, but I couldn't let this go further. After all, we were still in a church… I slowly pulled away from him a string of saliva still connecting our lips from our passionate kiss as San captured my lips in a deep possessive kiss again, pulling me into a more rushed kiss, sucking my lower lip between his teeth, as my hands were on his pumped-up chest trying to push him away carefully.

He leaned his forehead against mine as we both breathed heavily. "I want you," He whispered in between quick breaths.

"We are in a church," I whispered back as my eyes met his, our eyes mirroring the same desire we felt for each other.

He nodded with a slight smile, as his lips met mine again, leaving a long peck on my warm lips. "I have to go, meet you at the cemetery at 8 p.m. darling." He left a kiss on the corner of my mouth and with that he left me there sitting on the table, the crosses and Bibles on the floor scattered, making me want to run away as quickly as possible from there, and I face-palmed myself mentally for being this high over heels for a man, who made me forget humans had sinned and that needed forgiveness.

I parked my car in the cemetery’s parking lot, the sun was slowly settling down, to hide behind the hills that hugged the town around. The weather was quite chilly, as it was already the end of summer, early autumn knocking on the door to let them in. This change of season meant I would soon have to return to where I lived and resume teaching the children who counted on me. I didn't want to let them down.

When I stepped inside the cemetery goosebumps ran through my body. The sun was barely shining, leaving me in a quiet and dark cemetery that was swimming in mist. I heard some weird noises that I couldn't comprehend. Perhaps it was a bird nesting in the branches or a squirrel scurrying up and down the tree trunks. I stood frozen at the entrance, hesitant to venture deeper into the eerie yet noisy cemetery. There were a lot of gravestones and some flowers that were long withered.

Then I gathered all my courage and stepped deeper into the cemetery not knowing where should I wait for San. The cemetery slowly swallowed me as I went deeper, the graves forming a labyrinth around me.

Suddenly, I heard footsteps, but I couldn't tell which direction they came from. My heart was beating wildly, and I was frozen in place, my legs refusing to move. Then, I felt hands on my waist from behind, squeezing me. I jumped and let out a small scream.

"Holy shit San, don't do this again." I felt relieved as I turned around and saw his face where the curves of his lips were up his dimples on the sight.

"Sorry," He chuckled as he saw my terrified face. "You seemed lost in here, darling." His hands were still on my waist as he pulled me closer to him.

"Of course, it's not me who comes to the cemetery daily to bury random people." I squinted my eyes looking up at him and I noticed he was in casual clothes that was a black T-shirt, glued to his chest and broad shoulders, the familiar cross hanging on his pumped-up chest, the T-shirt paired with black sweatpants. He looked so comforting in normal clothes I wanted to hug him so badly.

He giggled, seeming genuinely happy—a rare sight to see him smile in a way that wasn't fake. His hands reached for mine, interlacing our fingers. "Come, I want to show you something," he said.

He began pulling me along by our interlaced hands, guiding me through the maze of graves and random sculptures of fallen angels that I didn’t quite understand. I realized there were many things about this small town that I didn't know, despite having grown up here.

Suddenly, San stopped, and I bumped into his broad back, feeling as if I had collided with an unbreakable wall. As I looked around, I saw we were standing in front of a grave that was unique—nothing like the others. It was crafted with care, adorned with fresh flowers in two vases on the ground, and featured graceful curves with winged decorations. I had never seen anything like it before. I turned to look at San, who stood next to me, gazing down at the grave with a look of deep grief.

"This is my grandmother's grave." He said with a low voice still holding my hand as I stood next to him. I nodded and caressed his shoulders signaling I was here next to him. "She raised me with my grandpa. My parents passed me to them when I was little. We have not heard about them since then." He sighed and sat down in front of his grandma's grave pulling up his legs to his chest and resting his elbows on his knees. I followed him and sat close to him and ran my hand up his back my fingers slowly combing through his raven-black hair. I wanted to be there with him, I wanted him to know I was by his side no matter what.

He was staring at his hands in front of him as he continued. "So, I was growing up here until I was eighteen, that was the time I left the town so I could study more."

"How come I don't remember you? I was growing up here, yet I never seen you." I asked with a frown.

His lips curved a little. "Well, I changed a lot. I was a weak and not-so-social little boy, maybe that is why." He tilted his head towards my direction to look at me with a slight smile. As I pouted trying to remember the boy he was describing. "If it helps you more, my grandfather was the priest before me." He smiled at me looking at my face, my eyes going wide at the realization.

"No way, you are the mysterious grandchild of Father John? Oh my God." I looked at him as I couldn't believe it. "Look at you, now being strong and independent." I squeezed his biceps as he chuckled. But then his expression turned serious.

"So, the thing is, I don't know where is my grandfather." His gaze went back to the grave in front of us.

"What? Isn't he retired?" I asked him a little confused.

"No, he had this year to complete, and he wanted to retire next year. I came to visit him, but he was nowhere to be found. I searched everywhere, but there was no trace. Then, one day, these guys came after me and mentioned a 200-year-old golden relic that my grandpa owned, worth millions. " He glanced at me briefly as he spoke.

"Those were the guys who chased us?" I asked him, trying to stay calm, it was a lot of information to process, as I remembered the night someone was chasing us with a black car, that night led us to San’s mansion.

"Yes, it's a mafia gang. They call themselves The Boyz and their leader is Sunwoo. One day they cornered me and told me they captured my grandpa and they were going to kill him if I don't tell them, where is the cup." His voice was full of rage as I watched his sharp side profile as he gritted his teeth. "When you saw me negotiate with some guys the other day, it was another gang called Ateez, their leader is Kim Hongjoong and I turned to them to ask for help. But the only way they agreed was that I give them the cup to keep it safe because they were famous for collecting different kinds of relics, and I agreed because I couldn't save my grandpa alone… I gave them money to help me but they only told me they were going to come when needed. And since that, I never saw them. So, it was a waste of time and I don't know if my grandpa is still alive." He sighed weakly in frustration, the burning rage slowly fading out of his eyes.

I ran my finger through my hair trying to calm down and think straight. "Do you know where is the cup?"

"Yes," He looked at me his eyes full of sadness alongside revenge. "We are sitting on it."

I frowned at that, looking around in confusion. "Where?"

"It's in my grandma's coffin."

My jaw hung open as I looked at the grave in front of us. "So, what will you do?"

"I don't know, Y/N…" He ran his fingers through his hair stressed. "I don't know what to do, what is the right choice I'm all by myself—"

"Hey," I said, reaching out to gently pull his hands away from his hair. I moved in front of him so I could look directly into his eyes. "I'm here. You're not alone, San." Kneeling between his spread legs, I cupped his face in my hands. "We'll figure this out together, okay?" I gazed into his eyes as I rested my forehead against his.

He nodded and enveloped me in his strong arms and legs while I remained kneeling, almost making me disappear in his embrace. "Thank you so much, Y/N." He whispered into my ears his voice going weak. The familiar scent of candy hugged me tight, giving me a comfort that I didn't even know I needed.

Then San pulled away as his hands cupped my face. "I want you to be by my side…I want to be with you, but I'm scared you might get hurt in the process. I have a difficult life, Y/N…especially now…I don't know if I can keep you safe." He whispered as his gaze never left mine, his eyes welling up with tears.

I traced my thump on his cheek, where a teardrop escaped his eyes and wiped it away. "I'm going to be okay, it's easier to fight together than alone, right?" My lips curved up a little, giving him comfort.

He smiled at me emotionally, as his finger reached towards my hair, brushing a string behind my ear. "You are so beautiful and perfect, my darling. I don't deserve you." His eyes beamed caring and unlimited love, which made my heart twist painfully, but that pain was good, it whispered good things for the future.

"You do deserve someone by your side. And I want to be that person." I whispered back, leaning close to his face. When his lips met mine, it felt like he was kissing me for the hundredth time, yet each kiss still felt like the very first. It wasn't rushed, it was careful and warm, we sealed our lips together as a promise to protect the other no matter what. Something in my heart started to grow and it felt right for the first time in my life. But then a voice interrupted our promise to each other.

“Well, well—the love birds are hiding in the cemetery. How romantic,” a voice said from behind us. I glanced over San’s shoulder and saw five men standing there, their eyes fixed on us with a predatory gaze.

San immediately got up and hid me behind his broad shoulder, his arms out in a protective manner. He looked like he was the mountain that hid people from danger. "Sunwoo…what do you want?" Sunwoo—then he was the leader of The Boyz… they were after the cup and we were standing right above it.

"Wasn't I clear enough on that?" I peeked out from the safety of San's back and saw the man who was speaking, he had foxlike eyes and black hair, and all of them were wearing leather jackets with ripped jeans, making them disappear into the darkness of the cemetery. I could barely count how many of them were still hiding in the dark.

Suddenly I heard hustling from behind and I had no time to react, all I felt was a hand around my neck and that pulled me away from San, a sharp, cold thing replacing the strange hand. San turned towards me, looking at the man behind me with sharp, glaring eyes. "Let her go, she has nothing to do with this!" He shouted as he tried to attack the man who held a knife to my neck. From the sudden movement, the knife went deeper into my skin, as blood streamed down my neck like tears. But San had no chance as the leader caught him in no time and held a gun to the back of his head. "Don't try to act like a hero, or she'll die," Sunwoo mumbled into San's ear.

I couldn't process what was happening, my heart was pumping loudly in my ear, and I barely heard what was happening. My vision was on San the whole time, whose eyes were staring at me, trying to give me some strength that I needed at that moment. I breathed heavily, trying to calm myself down, but as I lifted my chest to breathe the sharp knife dug deeper into my skin, making me panic at the sudden pain.

"If you tell us, where the fuck is that cup, I'm going to tell you where is your old man and we won't kill this sweetheart." The leader nodded towards me with a perverted smile. I wanted to throw up from the pain and the faces they all made while looking at me.

I met San’s gaze again; he was signaling that he was about to make a move. In a sudden burst of action, he spun around, grabbed the gun that was pressed against his head and punched the man in front of him who fell to the ground. At the sudden movements, the man behind me lost the grip of the knife and I immediately kicked him in the balls and he hunched over immediately from the sudden pain. San ran towards me and held me by both sides of my shoulders. "You have to run, Y/N! Drive to the mansion and wait for me there, please!" He said hurriedly, as the other men were running towards us. Fuck, I had no chance there, but I did not want to leave him alone.

He saw my face as I hesitated a little, "I promise I'm going to find you, darling. Just go!" He begged me as the man behind him gripped his shoulder trying to hit him. I wanted to scream and shout at the men who attacked him, but I needed to run and get some help for him. San was fighting with the two men, punching them and trying to dodge their movements.

Then I got an idea, San had no chance against a bunch of people we were surrounded by, it was impossible, so I needed to distract a few of them. The ones behind my back were walking towards me because they knew I had no chance, but I quickly jumped over a grave and started to run so they were going to get far away from San. I needed to reach my car, but navigating through the graves was difficult in the dark; I could only make out vague shapes.

I jumped over several gravestones and tried to be as quick as I could and try to distract them, hoping one of them was going to get lost in the dark mist, trying to move quickly and create enough confusion that maybe one of them would get lost in the darkness. Then I heard gunshots—lots of them. The sound made me stumble, and I fell to the ground, feeling a surge of fear and wanting to cry. "San," I whispered, still on the ground as the men behind me closed in. I couldn't let them catch me, for San, I needed to gather my strength and get help for him. So, I stood up with determination and started to run towards the exit.

When I finally arrived at a trail that led me to the exit, I felt relieved as the adrenaline gave me a burst of power, making me run faster as I looked behind me. Three men were running after me, the fourth probably gave up on chasing me, or he did get lost in the labyrinth of the cemetery.

I ran through the exit and quickly sat in my car. I fired the engine, the lamps lit up and the three men were standing in front of my car, their faces like the devil's, smiling in success as they trapped me. But I was in a car, and I had the advantage of simply using it as a weapon. The engine of the car roared up as I hit the gas pedal and the car speeded towards them. Two of the men managed to jump out of the way, but the third wasn't as fortunate.

He leaped onto the hood of my car, trying to avoid the impact. He looked at me with killer eyes through the windshield as I was still speeding, but then I hit the break and he stumbled forward, hitting the ground with a loud thump. I hoped he wasn’t seriously injured—or worse.

I was frozen for a moment as I tried to think what to do, my breathing was loud and heavy, and blood pumped in my ears. Then I looked to my right and saw a baseball bat lying on the floor. I had kept it in the car for situations just like this. Why not use it? I couldn't just leave here San; I promised him we were going to fight together.

So, I grabbed the bat and opened the car door. The man I had hit was groaning on the ground, clearly in pain but still alive. The other two men were running towards me as I held up the baseball bat preparing to defend myself as they approached.

But then, I heard a loud engine sound and all I saw was a big, black jeep, hitting the two men that were running towards me. It all happened so quickly. The jeep stood in quiet for a moment, the front a little broken from the impact and smoke coming up from the engine.

Then someone opened the passenger door and a tall man got out of it, whom I barely saw in the dim lights of the parking lot. The other door opened as well, and another tall figure stepped out, both of them heading in my direction. I held up the baseball bat again because I did not know if I could trust these men.

"We are here to help." The one with the soft features raised his hands in the air.

"Who are you?" I asked them, gathering all the strength I had left.

"I'm Jeong Yunho, Kim Hongjoong sent me to help San." He is Song Mingi, we came to help." The tall boy came closer to me and reached his hands to shake hands, his features full of kindness.

"We don't have time for this, San is in the cemetery and we got attacked, he needs help." I started to panic as I did not hear anything after the gunshots.

"Mingi stay with her, she is injured, I'm going to find San! " Yunho said with a serious expression on his face as he was speaking to the other guy, whose expression was bored as he leaned against my car folding his arms. Then Yunho ran towards the entrance of the cemetery as the dark swallowed him.

I leaned against my car, waiting impatiently for Yunho and San to come, I tried to go after them a few times but Mingi stopped me all the time, saying 'Let them do their job'.

After half an hour that I spent worrying about San, their dark figure finally appeared from the cemetery as Yunho was holding San by the waist and San's hands were clinging around Yunho's neck. I hurried in front of them quickly, San seemed injured.

"San-ah, are you okay?" I cupped his face, which was a little beaten up, with a few cuts on his lips, and on his cheekbones.

"I'm okay, darling, I'm okay," he whispered as he released Yunho and pulled me into a protective embrace. When he gently pulled me away, his eyes roamed over me from head to toe, checking for any injuries. His gaze finally landed on my neck.

"Fuck, Y/N!" He traced the cut on my neck with great care, where the blood had already dried—I had already forgotten about my wound. "Does it hurt?" he asked softly. Leaning down, he placed a tender kiss on the wound, sending shivers through my body.

I shook my head as a no. "It's not that deep."

He tilted his head up looking into my eyes with anger. "I'm glad I killed those motherfuckers." My heart started to race at that, it was a new side of him, that I did not see until now. It did scare me, but at the same time, I knew he had no other choice than to kill them. It was a choice between him and them, and clearly, the better option was for San to survive.

"Okay you love each other we get it," Yunho clasped his hands together, making me remember they were also there. "But we should hurry if you want to save your old man, San."

"Where is he?" San asked turning towards the two tall men, both leaning against the car. San's eyes were full of determination.

"Right now, as our people told us, he is in a building that is going to explode in like…" Yunho looked at his watch on his wrist. "…10 minutes." He said casually.

"Then why are we even here, let's go!" San said, already forgetting he was injured, as we sat into the black jeep, the guys already gone that they hit.

As we made our way to the building, I cuddled up to San’s side. He caressed my back and ran his fingers through my hair, whispering how proud he was of me for standing up to the bad guys and staying by his side. Even if I had the choice, I wouldn't have it any other way. I knew I was meant to be with San, and I never wanted to leave him.

When we arrived at the building, which was about to explode, I stayed in the car despite my urge to join them. I figured it would be easier for them if I stayed behind. Nervously biting my nails, I watched the clock ticking down to the explosion—just 2 minutes remaining—and they were still nowhere to be seen.

I couldn’t stay still. I stepped out of the car and paced back and forth in front of it, my anxiety making it impossible to remain in one place.

1 minute - nothing

30 seconds - nothing

I was on the verge of running into the building just before it was about to explode when I saw four figures run through the entrance the moment the building exploded. The moment the building erupted, a burst of orange filled the dark air pieces of the building everywhere in the air, which landed in a rain-like form on the ground with a loud thump as the explosion shook the ground.

I lost sight of the figures running as I held my arm out forming a shield. Bits of concrete and debris struck me, and some landed on the car. When the building caught on fire I looked around to search for them.

But I saw no one in between the burning pieces. I walked closer, as I spotted them between two big concrete pieces that fell from the building. As I ran to them, I saw that San held his grandfather on his lap, crying as Yunho and Mingi were kneeling beside them, Yunho's hands on San's shoulder trying to calm him down.

I speeded next to San my hands on his back, as I looked down at his grandfather. His abdomen was full of blood, his T-shirt long soaked with red, his chest unmoving, and his eyes were glassy, a single teardrop falling towards his temple as he was staring up at the sky full of stars, with no reaction in his eyes. He left us.

"I couldn't save him," San's voice came out and stumbled as he was sobbing, holding his grandfather's dead body. His grandfather raised him and made his grandchild the most caring and passionate human on earth. He fulfilled his job and it was time for him to leave us behind.

I hugged San as he was sobbing into my neck, still careful not to hurt the wound on my neck. I whispered to him some reassuring thoughts that slowly calmed him down. Yunho and Mingi waited for us patiently to calm down so we could talk about the cup that was the cause of this turmoil that ended with the death of San's grandfather.