#preston lauterbach

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

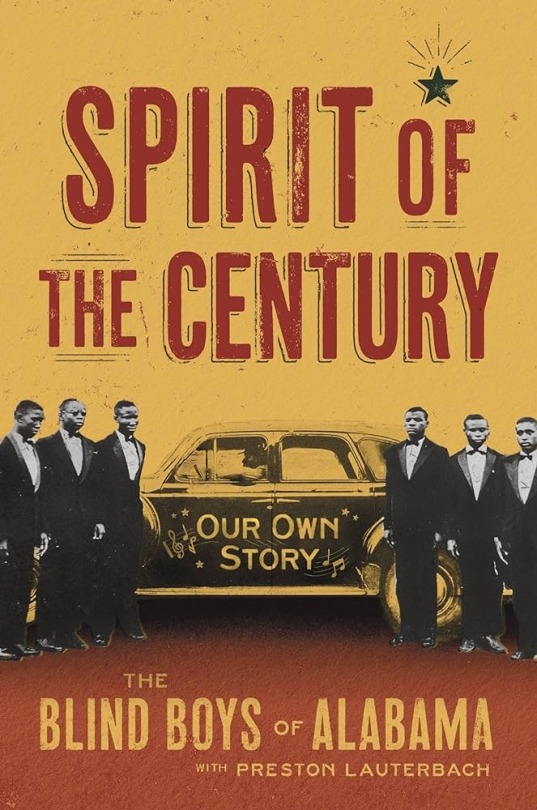

Book Review: “Spirit of the Century: Our Own Story” by the Blind Boys of Alabama with Preston Lauterbach

The complete and unvarnished story of the Blind Boys of Alabama is finally told in “Spirit of the Century: Our Own Story.”

The resulting 320 pages contain the fullest accounting of the poorly documented Blind Boys the world is likely to ever get, rectifying a fate befalling many black American artists. “Spirit” fills in all the gaps in membership, the lean years and the Blind Boys’ 1980s renaissance and other facts that even long-time followers would’ve been unlikely to know about before diving in to the book.

Written by the band with “The Chitlin’ Circuit” author Preston Lauterbach, “Spirit of the Century” covers the Blind Boys’ 1939 beginnings as the Happy Land Jubilee Singers at the Alabama Institute for the Negro Deaf and Blind through to the present day. Along the way, the gaping holes in the group’s story are plugged with solid research, plenty of archival and contemporary interviews and strong writing.

The Happy Lands, as Lauterbach refers to the early group, turned professional in 1944, leaving behind one Jimmy Carter, who was too young to hit the road, but would come back in the 1980s after a two-decade stint with the Blind Boys of Mississippi to form a “holy trinity” with co-founders George Scott and Clarence Fountain. Carter ultimately became the group’s third leader, after Velma Traylor and Fountain. He retained that title until his 2023 retirement and the passing of the reins to Rickie McKinnie.

In a move described as akin to Mick Jagger leaving the Rolling Stones to join the Beatles, Fountain decamped the Alabama Blind Boys in 1969 and temporarily hooked up with the hard-drinking Blind Boys of Mississippi. It was here Fountain and Carter first reconnected before the former, who had girlfriends scattered around the country and six children he denied in his will, eventually moved on to a star-crossed solo career that found him touring with horny conjoined twins and participating in a stolen-car ring with a con-man manager before rejoining his original group in the 1970s.

Fountain’s life, Lauterbach writes, was “a maze of complications that make Sophocles seem like Dr. Seuss.”

Carter eventually transferred from the Mississippi to the Alabama Blind Boys and, after the band starred in 1983’s “The Gospel at Colonus,” found mainstream success as the musical “made the Blind Boys of Alabama white-people famous.”

This led to working relationships with Lou Reed, Ben Harper, Peter Gabriel and others. The Blind Boys of Alabama picked up Grammy awards and sung for presidents but never lost their taste for their beloved “Mack Donald’s,” where they stopped on the way to perform for George W. Bush.

“So we go into the White House with a guy named Jimmy Carter and all the rest holding McDonald’s bags,” BBA’s manager is quoted as saying in the book.

Lauterbach told the story just in time. Carter, the last surviving original member of the group, is 92 and retired and while the Blind Boys of Alabama plan to continue on indefinitely, their original era is over. That’s all the more reason to give thanks to Lauterbach for uncovering one of music’s most-important sagas and for “Spirit of the Century,” easily the most-informative music biography of the past decade.

Grade card: “Spirit of the Century: Our Own Story” by the Blind Boys of Alabama with Preston Lauterbach - A

4/29/24

#the blind boys of alabama#spirit of the century: our own story#preston lauterbach#the blind boys of mississippi#mick jagger#the rolling stones#the beatles#ben harper#lou reed#peter gabriel#the gospel at colonus

1 note

·

View note

Text

Last of the Great Furniture-in-Mouth Blues Singers

But the group couldn’t transfer that energy from Club Matinee to the recording studio. It is, after all, difficult to capture the sound of a man dancing with a table in his mouth. The Chitlin’ Circuit and the Road to Rock ‘n’ Roll, Preston Lauterbach As the bus slows to a halt at the flag stop just outside Itta Benna, Mississippi, I rub my eyes, startled awake by…

0 notes

Text

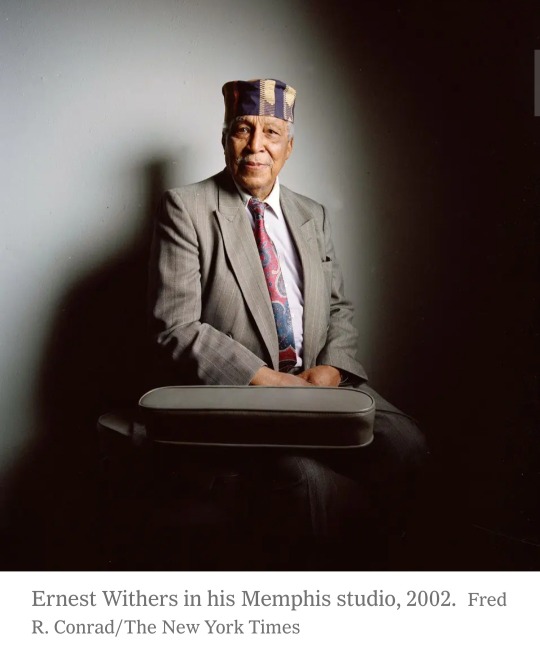

First investigated by the FBI in 1946 for having suspected communist ties, Withers' work came to an end after tapes revealed he was using his position to try to free a young Black man facing a long prison sentence for a first-time offense.

Withers was the only photographer to document the entire Emmett Till murder trial. He also documented Memphis's bustling Beale Street blues scene, making both studio portraits of up-and-coming musicians and going inside the clubs for shots of live shows and their audiences.

Hailing from Memphis, he was one of the first Black police officers to join the force after serving in the Pacific Theater during World War II. Although Withers was given a uniform, patrol car, and gun, he was forbidden to patrol white communities or arrest white people. His power was proscribed strictly within the confines of Black Memphis, during the height of segregation.

Preston Lauterbach, author of Bluff City, said, "When the news came out that he was an informer, people were so outraged because of what we know now the FBI was doing. But when you get into the story, you realize he was involved long before all the things we know about [FBI director] J. Edgar Hoover became public. There were instances in which the feds provided the only real help that the movement was going to get from any angle of the American government."

0 notes

Text

The importance of a diversified press is essential in understanding the world

When this reporter was in J-school at City College of San Francisco, not too long ago, it was impressed upon me how important it was that the media have a diversity of view points.

But most importantly, that those view points be from people who are there on the ground in the midst of what is happening. I was recently reminded of this as I stumbled upon a new book called “Bluff City - The Secret Life of photographer Ernest Withers by author Preston Lauterbach.

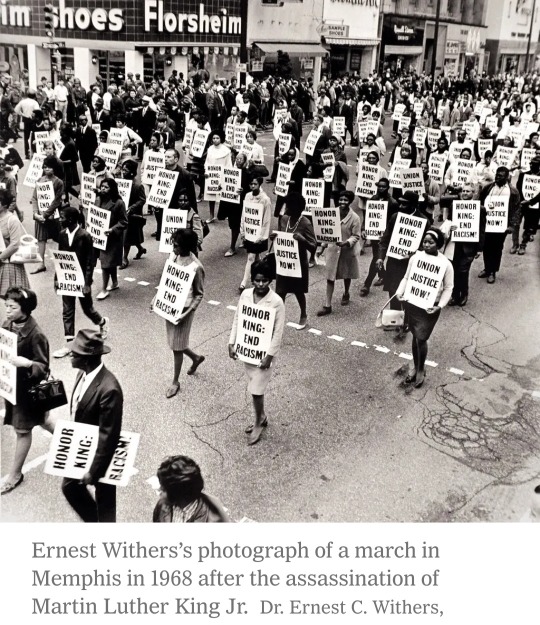

I had never heard of Ernest Withers before. Yet I was aware of the Civil Rights movement. Withers was among the foremost photojournalists who brought news of some the most significant aspects of the Civil Rights Movement to the headlines. Among those most significant was the “I am A Man” protest which happened in Memphis over 50 years ago this coming March.

Withers was also controversial. Not simply for reporting on unpleasant topics in a time of ultra-conservatism, he worked with the FBI. It almost seems counter-intuitive, to be a journalist and be working with the FBI. In today’s mind that is clearly a conflict of interest. But turn back the clock of time to those McCarthyism-Era days and the FBI was checking into everyone and everything.

I reached out to Lauterbach to get some insight into this. And, I thought maybe it might be because Withers had been a former policeman. The award-winning author had this to say about Withers.

“Withers spoke at length about his time on the force. He felt he was set up to be kicked off. He told a few stories about how difficult it was to conduct police work with racial constraints. My gut, said Lauterbach is that the police work led indirectly to working for the Bureau. It's conjecture, but he might have seen undercover work as a sort of continuation of his police work. The Bureau knew about how he was dismissed from the force, and though they couldn't use that against him, it may have shown them something about his character.”

Another aspect that came into my mind was the fact that if someone wanted to make changes, at some point they had to work with “the system.” Like it or not, that is what the government was back then, conservative and “pro-American.”

It wasn’t until the Vietnam War and the scandal of Watergate, when people began to become openly skeptical of government.

Still, back to the importance of diversity in media. When sources all become bland, or are way too driven by commercial gain, that is when democracy suffers.

The issue of social justice is also in jeopardy when media is curtailed to reflect only one side of the population. Or, media is there only for commercial gain and little else.

It is easy to take our ‘Fourth Estate’ freedom of the press rights as granted. This is a very important freedom. But is also one that wields responsibility. The temptation to aim for the emotion or get ideas and facts all stirred up is always there. And, an honest reporter of integrity knows and understands this.

But it is also a citizen’s responsibility to be informed beyond what is published underneath the headlines.

An investigative reporter is of tremendous value to the public and sadly because of the overly commercial aspects of media, the public confuses a good reporter with shoddy media outlets.

There will always be gossip, even in print. But it takes a discerning and mature person to discern that and to sort facts from fiction.

Apart from the gripping and disturbing aspects to Withers’ photos and the ugly part of our past American history in the 20th Century; Lauterbach provides a detailed look at not only Withers and those times but at Memphis itself.

Lauterbach’s interview with NPR provides more insights.

A former Rhodes scholar, Lauterbach gives both an unflinching look at the past and one that includes a touch of ‘Southern Charm.’ After all, Memphis was the home of Elvis Presley.

Well worth the time to read and especially for those who appreciate history. And, for journalists who want to understand the importance of a dedicated profession, “Bluff City” is a book to place at the top of your required - must read list. To learn more visit Preston Lauterbach’s web site.

#Preston Lauterbach#Bluff City#Ernest Withers#Memphis#tennesee#I am a Man march#1968#civil rights#journlism#diversity#CCSF#Martin Luther King#rhodes scholarship

0 notes

Link

Bluff City: The Secret Life of Photographer Ernest Withers by Preston Lauterbach https://amzn.to/2Cy1TgN

#memphis (tenn)#Bluff City#Preston Lauterbach#Ernest Withers#FBI#Bluff City: The Secret Life of Photographer Ernest Withers#books#biography#book review

0 notes

Text

'Brother Robert' Reveals True Story Of Growing Up With Blues Legend Robert Johnson

December 29, 20203:51 PM ET | Heard on All Things Considered | Ben James

Annye Anderson — stepsister of Robert Johnson — published her memoir Brother Robert: Growing Up with Robert Johnson in June.

Blues legend Robert Johnson has been mythologized as a backwoods loner, his talent the result of selling his soul to the devil. Wrong and wrong again, according to Johnson's younger stepsister, who lives in Amherst, Mass. She tells his true story in Brother Robert: Growing Up with Robert Johnson, a memoir about growing up with her brother she published in June.

Her name is Annye Anderson, but unless you're older than she is — and fat chance of that, as she's 94 — you better call her Mrs. Anderson.

"People say, 'Don't you have a first name?'" Anderson says from the couch in her living room. "I say, 'Yes, I do.' And they wait for it. But I tell them, 'Mrs. Anderson will do just fine.'"

Amherst is a long way from the Memphis of Mrs. Anderson's childhood, where she grew up in an extended family of siblings, half-siblings and the guitar-playing older stepbrother she called Brother Robert.

"Brother Robert and I used to do the buck dance," Anderson says. "Because you know he could move. People don't know. He didn't just sit and play like they showed him with that caricature."

Anderson's childhood — back then she was Annie Spencer — was steeped in the tunes played by Johnson and others, along with all the popular songs they listened to together on the radio.

But before his mysterious death in 1938, Johnson's "Baby Sis" only ever held one of his records in her hands. It was "Terraplane Blues," his first release and only record to gain any popularity during his lifetime. After he died, his 29 recorded songs were quickly forgotten.

youtube

Anderson became a short order cook, a secretary at the pentagon, a teacher and school administrator. She moved to Washington, D.C. and, later, Massachusetts. In the '60s, amidst the civil rights movement, she began to hear something familiar on the radio: her brother's songs.

"During the movement, people were playing his music everywhere and his riffs everywhere," she says. "Sound familiar, but we didn't know they were copying from — we didn't know about Eric Clapton, and Led Zeppelin, and Keith Richards, the Rolling Stones."

Music and culture critic Greil Marcus has been a fan of Robert Johnson for decades. Now he's a fan of Anderson. Marcus praises her new book — and Johnson's artistry — in the New York Review of Books.

"There is something in Robert Johnson's music that goes beyond, goes above, that is harder, that is deeper, that burrows beneath in ways that other music doesn't," Marcus says.

The cover of Brother Robert shows the third known photograph of Johnson, never before seen by the public. Anderson and her older half-sister, who she called Sister Carrie, kept that photo close for decades, storing it in a box that originally held sewing machine oil.

Anderson's story begins with her family's roots in Hazlehurst, Miss. — including her first memory of Johnson in Memphis when he swept her up and carried her up a set of steps "like lightning" — and spans the decades after her brother's death, when a mostly-white audience invented the story of Johnson selling his soul to the devil at the crossroads, a myth that was more racist caricature than anything having to do with his actual life.

"I'm not saying he was an angel," Anderson says. "And I'm not saying what he didn't and did do. Because I didn't have him in my pocket. But people like to be on the dark side. And that's what they paint. He's brilliant on one side. And he's dark on the other. And I deeply resent that."

The second half of Anderson's book recounts numerous ways in which she and Sister Carrie were excluded from Johnson's estate while white music publishers and other opportunists sought to profit from his legacy.

Anderson co-wrote Brother Robert with historian Preston Lauterbach. She sought him out herself, she says, after his book The Chitlin' Circuit fell at her feet in the music section at her local Barnes & Noble.

"I opened it and then I saw this white face," Anderson says. "And I said, 'Well, what does he know about the chitlin' circuit?'"

She bought the book and read most of it that same night, deciding she needed Lauterbach's help in her ambition to correct the record on the life of Robert Johnson. Anderson talked about the book for years, never believing that it would exist one day.

"She felt that the story had been told badly by outsiders for long enough," says Elijah Wald, author of Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues. "And she wanted to tell the story herself."

Wald, who wrote the introduction to Brother Robert, says Anderson's book offers a necessary corrective to the image of Johnson as a backwoods loner playing primal and haunted music.

"Robert Johnson was as much the guy from Memphis who went out in the country and was the hip city guy as he ever was the guy from the dark Delta who went up to the cities," he says.

Marcus concurs, saying what stands out most in Brother Robert is the sheer range of American popular music flooding through Anderson's story. A couple pages in, he says, he started making a list of songs the family listened to or played.

"And the list just grew and grew until there were maybe 20, 30, 40 different examples. And I realized no one could have a richer, broader, more mainstream American cultural life than the one that Robert Johnson lived out," Marcus says.

Some of Anderson's favorites included The Vagabonds, Gene Autry, Clyde McCoy now, Count Basie, Fiddlin' John Carson, Bing Crosby and Louis Armstrong.

"Brother Robert is the one that got me into country music," she says. "'Course, Jimmie Rodgers was his favorite. I will never forget 'Waiting for a Train' and doing it with Brother Robert."

The two would bust up laughing at the line "Get off, get off, you railroad bums." And then came Rogers' famous yodel.

"I tried to yodel," Anderson says. "But brother Robert could yodel. He could mimic anything."

youtube

In the memoir there's a moment, toward the end of Johnson's life, when a young Anderson walks her brother to a spot on Highway 61 so he can hitch a ride across the Mississippi. He smelled of cigarettes, Anderson writes, and Dixie Peach pomade:

"He would say, 'Well, little girl, this is far as you could go,' Because I wasn't supposed to go but so far. He'd give me a hug — 'Bye Little Sis' — and tell me to go straight home."

Many of Johnson's fans would likely sell their own souls to be able to follow him down that highway to his next house party and to hear his version of "Waiting for a Train." Instead, they've got his 29 recorded songs. And now they have Anderson's memoir.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

BROTHER ROBERT: Growing Up with Robert Johnson by Annye C. Anderson, with Preston Lauterbach

14 notes

·

View notes

Quote

They are sister cities, one is high maintenance and fussy, but so seductive. The other is warm and friendly, but carries a razor in her boot. They share a parent, the Mississippi River, and legacies as the two most vital cities in American music history. They are New Orleans and Memphis.

Preston Lauterbach in Virginia Quarterly Review (Spring 2014). Sister Cities: Louis Armstrong’s New Orleans and Stax Records’ Memphis

Louis Armstrong, Master of Modernism

Respect Yourself: Stax Records and the Soul Explosion

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Annye Anderson visits the site of her family home in Memphis, Tennessee, where she lived with Robert Johnson.

Annye Anderson, at right, in Memphis with her co-writer Preston Lauterbach. They're in front of a mural of Anderson's stepbrother, blues legend Robert Johnson.

Robert Johnson's Stepsister Tells His Story, And Her Own, In 'Brother Robert'

The first thing to know about Annye Anderson is unless you’re older than she is — and fat chance of that; she’s 94 — you better just call her Mrs. Anderson.

“People say, ‘Don't you have a first name?’” Anderson said from the couch in her living room in Amherst, Massachusetts. “I say, ‘Yes, I do.’ And they wait for it. But I tell them, ‘Mrs. Anderson will do just fine.’”

Amherst is a long way from the Memphis of Mrs. Anderson’s childhood, where she grew up in an extended family that was steeped in music. Among her older siblings was a singer and guitarist named Robert Johnson, whom she called Brother Robert.

READ MORE https://www.nepm.org/post/robert-johnsons-stepsister-tells-his-story-and-her-own-brother-robert

“Elijah Wald called the actual biography of Johnson that came out last year - Up Jumped the Devil: The Real Life of Robert Johnson - by Conforth and Wardlow "The definitive Robert Johnson biography." amazon.com 1 * reviewer

0 notes

Link

Genres were invented to sell music.

As that indicates, the music business needs to know what it's selling and who it's selling to. Hillbilly music, a term that predates country music, was the coinage of Ralph Peer, who in 1925 recorded a North Carolina group he named the Hillbillies. When Peer recorded Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family two years later, the name stuck to the sound. Sire label boss Seymour Stein famously came up with new wave to sell punk to US audiences who were afraid of punk's violent connotations. In 1995, Motown executive Kedar Massenburg, who signed D'Angelo and Erykah Badu, came up with neo-soul as a way to sell them. (It definitively supplanted Nelson George's retro-nuevo.)

Then there is advertising. Bossa nova – Portuguese for "new wave" – gained currency, according to Brazilian music historian Ruy Castro, when it appeared in an advert for a 1958 multi-artist concert put on by Grupo Universitário Hebraico do Brasil. World music was hashed out in 1987 at an industry meeting. It was intended only for a brief marketing campaign to pump non-Anglophone musicians in retail spaces they might not otherwise fit into, only to remain an acknowledged, if unwieldy, category. Radio formats sometimes impose themselves on the music. AOR is a US abbreviation for "album-oriented radio" (later "rock") coined in 1972 by Lee Abrams and Kent Burkhart's consultancy firm for the FM rock radio stations that would define ultra-slick middle-American rock: Styx, Boston, Aerosmith. In practise, it usually translates to "definitively pre-punk".

And of course, radio plays a big role in the history of the term rock'n'roll itself – though it had been used in blues records dating back to 1922 (Trixie Smith's My Man Rocks Me with a Steady Roll, for example) and, as Preston Lauterbach's superb new book The Chitlin' Circuit makes clear, was basically everyday talk in postwar R&B: Roy Brown's 1947 Good Rockin' Tonight (later cut by Wynonie Harris and, on his second single, Elvis Presley); Wild Bill Moore's We're Gonna Rock, We're Gonna Roll (1947); the Dominoes' Sixty Minute Man (1950) ("I'll rock 'em, roll 'em all night long"). Then in 1952, Cleveland DJ Alan Freed switched his radio show's name from Record Rendezvous to The Moondog Rock'n'Roll House Party. We'll leave it there.

0 notes

Photo

The Civil Rights Movement Photographer Who Was Also an F.B.I. Informant The Civil Rights Movement Photographer Who Was Also an F.B.I. Informant When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission. BLUFF CITY The Secret Life of Photographer Ernest Withers By Preston Lauterbach Illustrated. 339 pp. W.W. Norton & Company. $27.95.

0 notes

Text

Nonfiction: The Civil Rights Movement Photographer Who Was Also an F.B.I. Informant

“Bluff City,” by Preston Lauterbach, delves into the double life of Ernest Withers, one of the era’s great documentarians.

0 notes

Link

“Bluff City,” by Preston Lauterbach, delves into the double life of Ernest Withers, one of the era’s great documentarians.

0 notes

Text

The Civil Rights Movement Photographer Who Was Also an F.B.I. Informant

By CHRISTOPHER BONANOS “Bluff City,” by Preston Lauterbach, delves into the double life of Ernest Withers, one of the era’s great documentarians. Published: January 18, 2019 at 03:30AM from NYT Books https://nyti.ms/2TXupiG

0 notes

Text

The Civil Rights Movement Photographer Who Was Also an F.B.I. Informant

By CHRISTOPHER BONANOS “Bluff City,” by Preston Lauterbach, delves into the double life of Ernest Withers, one of the era’s great documentarians. Published: January 18, 2019 at 01:00AM from NYT Books https://nyti.ms/2TXupiG

0 notes

Text

The Civil Rights Movement Photographer Who Was Also an F.B.I. Informant

By CHRISTOPHER BONANOS “Bluff City,” by Preston Lauterbach, delves into the double life of Ernest Withers, one of the era’s great documentarians. Published: January 18, 2019 at 09:00AM from NYT Books https://nyti.ms/2TXupiG via IFTTT

0 notes