#preclassic period

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Funerary Face Cover, Java, Indonesia,

Preclassic Period (ca. 500 B.C.E. / 500 C.E.)

Gold,

Eye-Nose cover: 4.54 × 4.8 cm, 1.087 g, 0.01 cm (1 13/16 × 1 7/8 in., 1.087 g),

#art#history#design#style#archeology#sculpture#antiquity#mask#funerary#java#indonesia#preclassic period#gold#jewelry#jewellery

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Xochipala is a minor archaeological site in the Mexican state of Guerrero, whose name has become attached, somewhat erroneously, to a style of Formative Period figurines and pottery from 1500 to 200 BCE.[1] The archaeological site is much later and belongs to the Classic and Postclassic eras, approximately 200–1400 CE.[2]

Acrobat

Mexico, Guerrero, Xochipala style, 900–500 BCE

#history#sculpture#preclassic period#classic period#postclassic period#mesoamerica#xochipala#mexico#guerrero#mesoamerica ref#xochipala ref

177 notes

·

View notes

Text

Friday Night Shots - Modular Expansions & Stories

Friday Night Shots - Modular Expansions & Stories @_dailymagic_ @LookoutSpiele @alderac

View On WordPress

#Alderac#Alexander Pfister#John D Clair#Lookout Games#Lunch Time Games#Oh My Goods#Oh My Goods - Escape to Canyon Brook#Oh My Goods - Longsdale in Revolt#Shadow Kingdoms of Valeria#Shadow Kingdoms of Valeria - Riftlands#Shadow Kingdoms of Valeria - Rise of Titans#Space Base#Space Base: Biodome#Space Base: Dreadnaughts#Space Base: The Emergence of Shy Pluto#Space Base: The Mysteries of Terra Proxima#Teotihuacan#Teotihuacan: Expansion Period#Teotihuacan: Late Preclassic Period#Teotihuacan: Shadow of Xitle

0 notes

Text

Tlatilco, burial 154

Tlatilco, entierro 154

(English / Español)

Tlatilco was a Valley of Mexico civilization, one of the first to settle in the Mexico Basin, on the shores of Lake Texcoco northwest of present-day Mexico City. Its historical location is in the Middle Preclassic Period, between 2500 BC. and 500 BC.

In Tlatilco, one of the most important sites of the Preclassic, more than five hundred burials could be explored over four seasons of excavations. From the fourth and last comes the burial 154 that contains an individual who presents cranial deformation, mutilation or filing of teeth. Among the objects associated with it stands out the bottle made in a very fine white clay that represents a contortionist, known as "the acrobat". In 1967, this and nine other burials were moved from Tlatilco to the Preclassic Room of the National Museum of Anthropology.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Tlatilco fue una civilización del valle de México, una de las primeras en asentarse en la Cuenca de México, en las orillas del lago de Texcoco al noroeste de la actual Ciudad de México. Su ubicación histórica se encuentra en el Período Preclásico Medio, entre 2500 a. C. y 500 a. C.

En Tlatilco, uno de los sitios más importantes del Preclásico, se pudieron explorar más de quinientos entierros a lo largo de cuatro temporadas de excavaciones. De la cuarta y última proviene el entierro 154 que contiene a un individuo que presenta deformación craneana, mutilación o limado de los dientes. Entre los objetos asociados a él destaca el botellón elaborado en un barro blanco muy fino que representa un contorsionista, conocido como “el acróbata”. En 1967, este y otros nueve entierros fueron trasladados desde Tlatilco, a la Sala del Preclásico del Museo Nacional de Antropología.

fuente:Tlatollotl on Tumblr

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Comparison between Mer and Anca Traditional Family Structures

Anca primolocal* family structures emphasize simple inheritance and incorporating external influences. Equality between host-partner and guest-partner is of paramount importance. Traditionally, the host-partner handles internal family matters such as housekeeping, child-rearing, farming, and finances, while the traveling- or guest-partner handles trade, dispute-settling, hunting, etc. Children bear the host's family name.

Mer superlocal* family structures, in contrast, require inequality. The senior partner's family adopts the junior, but they are never fully-vested members of the clan. Inverse to the Anca, it is the nonlocal partner's role to take care of the household–a position deemed inferior to the hunting and fighting which brought honor and glory to the clan.

#mer#anca#family structures#isolate period#archaic period#preclassical period#footnote#here primolocal and superlocal are terms i am coining as non-gendered alternatives to patri- and matrilocal

0 notes

Text

The Mezcala sculptural style of Guerrero emphasizes geometric abstraction in both human figures and architectural models. Few examples have been found in their original context, and thus the function, meaning, and even the length of time during which the style was in use remain ill defined. Contributing to the question of chronology is the fact that other Mesoamerican peoples, from the latter centuries of the Late Formative to the Late Postclassic periods (200-1500 CE), acquired and preserved these works as heirlooms. They have been found at sites throughout Mexico, and large numbers were excavated from ritual caches in the Templo Mayor, the main temple of the fifteenth-century Mexica (Aztecs) of Tenochtitlan (Mexico City). In the twentieth century, the minimalistic Mezcala artworks fascinated the Mexican artist and cultural historian Miguel Covarrubias, who compared them favorably to other sculptural traditions such as the celebrated Cycladic style of ancient Greece. This example features the typical Mezcala four-columned structure atop a pyramidal platform articulated by apron-moldings on the uppermost tier. A central staircase leads into the structure at the midpoint between the columns. A lone figure stands between the columns and inside the structure. No buildings of this type have survived in Guerrero, however, which leaves open the question of whether this carving faithfully represents the architectural traditions of the region during the Formative and Classic periods.

~ Temple Model.

Culture: Mezcala

Date: 300 B.C.-A.D. 500 (?)

Period: Terminal Formative-Early Classic

Medium: Stone

#history#sculpture#art#art history#architecture#preclassic era#classic period#postclassic period#mesoamerica#mezcala culture#aztec empire#tenochtitlan#mexico#guerrero#mexico city#templo mayor#miguel covarrubias

220 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Ball Game of Mesoamerica

The sport known simply as the Ball Game was played by all the major Mesoamerican civilizations and the impressive stone courts became a feature of many cities. More than just a game, it could have a religious significance and featured in episodes of mythology. Contests even supplied candidates for human sacrifice and became literally a game of life or death.

Origins

The game was invented sometime in the Preclassical Period (2500-100 BCE), probably by the Olmec, and became a common Mesoamerican-wide feature of the urban landscape by the Classical Period (300-900 CE). Eventually, the game was even exported to other cultures in North America and the Caribbean.

In Mesoamerican mythology the game is an important element in the story of the Maya gods Hun Hunahpú and Vucub Hunahpú. The pair annoyed the gods of the underworld with their noisy playing and the two brothers were tricked into descending into Xibalba (the underworld) where they were challenged to a ball game. Losing the game, Hun Hunahpús had his head cut off; a foretaste of what would become common practice for players unfortunate enough to lose a game.

In another legend, a famous ball game was held at the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan between the Aztec king Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin (r. 1502-1520 CE) and the king of Texcoco. The latter had predicted that Motecuhzoma's kingdom would fall and the game was set-up to establish the truth of this bold prediction. Motecuhzoma lost the game and did, of course, lose his kingdom at the hands of the invaders from the Old World. The story also supports the idea that the ball game was sometimes used for the purposes of divination.

Continue reading...

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

NOT COUNTING ROCKS (unless it’s a specific fossil from a time period you can name) or buildings (you cannot hold those)…

#Making my own because of the skew of the last one lol#My answer is still either acheulean hand-axes (800k years old) or Devonian/Silurian brachiopod fossils (350-450 million years old)#Depending on what u count#history#polls

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Beneath 1,350 square miles of dense jungle in northern Guatemala, scientists have discovered 417 cities that date back to circa 1000 B.C. and that are connected by nearly 110 miles of “superhighways” — a network of what researchers called “the first freeway system in the world.”

Scientist say this extensive road-and-city network, along with sophisticated ceremonial complexes, hydraulic systems and agricultural infrastructure, suggests that the ancient Maya civilization, which stretched through what is now Central America, was far more advanced than previously thought.

Mapping the area since 2015 using lidar technology — an advanced type of radar that reveals things hidden by dense vegetation and the tree canopy — researchers have found what they say is evidence of a well-organized economic, political and social system operating some two millennia ago.

The discovery is sparking a rethinking of the accepted idea that the people of the mid- to late-Preclassic Maya civilization (1000 B.C. to A.D. 250) would have been only hunter-gatherers, “roving bands of nomads, planting corn,” says Richard Hansen, the lead author of a study about the finding that was published in January and an affiliate research professor of archaeology at the University of Idaho.

“We now know that the Preclassic period was one of extraordinary complexity and architectural sophistication, with some of the largest buildings in world history being constructed during this time,” says Hansen, president of the Foundation for Anthropological Research and Environmental Studies, a nonprofit scientific research institution that focuses on ancient Maya history.

These findings in the El Mirador jungle region are a “game changer” in thinking about the history of the Americas, Hansen said. The lidar findings have unveiled “a whole volume of human history that we’ve never known” because of the scarcity of artifacts from that period, which were probably buried by later construction by the Maya and then covered by jungle.

Lidar, which stands for light detection and ranging, works via an aerial transmitter that bounces millions of infrared laser pulses off the ground, essentially sketching 3D images of structures hidden by the jungle. It has become a vital tool for archaeologists who previously relied on hand-drawings of where they estimated areas of note might be and, by the late 1980s, the first 3D maps.

When scientists digitally removed ceiba and sapodilla trees that cloak the area, the lidar images revealed ancient dams, reservoirs, pyramids and ball courts. El Mirador has long been considered the “cradle of the Maya civilization,” but the proof of a complex society already being in place circa 1000 B.C. suggests “a whole volume of human history that we’ve never known before,” the study says."

-via The Washington Post, via MSN, because Washington Post links don't work on tumblr for some godawful reason. May 20, 2023.

#maya#mayan#mesoamerica#central america#el mirador#guatemala#indigenous#indigenous history#indigenous peoples#mesoamerican#architecture#ancient history#anti colonialism#fuck racist misconceptions and narratives about indigenous societies and technologies#history#good news#hope

254 notes

·

View notes

Text

Huehueteotl-Xiuhtecuhtli Talon Abraxas

Among the Aztec/Mexica, the fire god was associated with another ancient deity, the old god. For this reason, these figures are often considered different aspects of the same deity: Huehuetéotl-Xiuhtecuhtli (Pronounced: Way-ue-TEE-ottle, and Shee-u-teh-COO-tleh). As with many polytheist cultures, ancient Mesoamerican people worshiped many gods who represented the different forces and manifestations of nature. Among these elements, fire was one of the first to be deified.

The names under which we know these gods are Nahuatl terms, which is the language spoken by the Aztec/Mexica, so we don’t know how earlier cultures knew these deities. Huehuetéotl is the “Old God”, from huehue, old, and teotl, god, whereas Xiuhtecuhtli means “The lord of Turquoise,” from the suffix xiuh, turquoise, or precious, and tecuhtli, lord, and he was considered the progenitor of all gods, as well as the patron of fire and the year.

Origins

Huehueteotl-Xiuhtecuhtli was an extremely important god beginning in very early times in Central Mexico. In the Formative (Preclassic) site of Cuicuilco, south of Mexico City, statues portraying an old man sitting and holding a brazier on his head or his back, have been interpreted as images of the old god and the fire god.

At Teotihuacan, the most important metropolis of the Classic period, Huehuetéotl-Xiuhtecuhtli is one of the most often represented deities. Again, his images portray an old man, with wrinkles on his face and no teeth, sitting with his legs crossed, holding a brazier on his head. The brazier is often decorated with rhomboid figures and cross-like signs symbolizing the four world directions with the god sitting in the middle.

Attributes

According to the Aztec religion, Huehuetéotl-Xiuhtecuhtli was associated with ideas of purification, transformation, and regeneration of the world through fire. As the god of the year, he was associated with the cycle of the seasons and nature which regenerate the earth. He was also considered one of the founding deities of the world since he was responsible for the creation of the sun.

According to colonial sources, the fire god had his temple in the sacred precinct of Tenochtitlan, in a place called Tzonmolco.

Huehuetéotl-Xiuhtecuhtli is also related to the ceremony of the New Fire, one of the most important Aztec ceremonies, which took place at the end of each cycle of 52 years and represented the regeneration of the cosmos through the lighting of a new fire.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

2024 Book Review #11 – The Maya (10th Edition) by Michael D. Coe and Stephen Houston

My second proper history book of the year, and significantly better than the first! This existed on the happy intersection of ‘the r/AskHistorian’s big list of recommenced works on Goodreads’ and ‘stuff my public library inexplicably has a copy of’. It’s dense and more than a bit dry reading, enough that I read it over the course of a week as a side-dish to more digestible fiction. Still, fascinating read, and a book that left more far better informed about the subject than when I started it.

The book is more or less what it says on the tin – a survey of the history of the Maya (or at least the current state of what’s known about it). The book opens with an explanation of the Maya language family, the relevant geography, the characteristics of the high- and lowlands, and the division into northern, central and southern area the field seems to use generally. The better part of it is then arranged chronologically, beginning with the Archaic Period, through the Pre-Classic and Classic, then then Collapse and the Post-Classic. The Spanish Conquest and history since gets a very abbreviated epilogue, ending with a few micro-anthropologies of different contemporary villages and then a five-page travellers’ guide to the most important sites and how to access them.

It’s all, as I said, quite dense – the sort of book where every paragraph adds at least one new important fact and very little time is spent on repetition or review. Combined with the usually very dry, expository tone, it feels much more like a textbook to be read with a lecturer or group to break down and dig into each section than something that was really written to be read alone and for pleasure. Which you know, makes sense, given that this is the tenth edition of a book originally written several decades before I was born.

Now, I say this is a history book, but that’s honestly a bit of a kludge – better to say it’s an archaeology book or, failing that, about anthropology and historiography. There is very little narativizing, and it is very much told from the point of view of the present. That is, the sections are organized chronologically, but within them the unit of analysis is the archaeological site, with every supposition explained as emerging from the analysis of some ruin or artifact or fragment of text. Far more time is spent on the architecture and layout of Mayan cities than the people who actually lived within them, simply because the author’s have so much more to say about them.

It’s only really in the chapters on the Classic (and, to a much lesser extent, post-classic) periods that the book goes from theorizing about building and pottery styles to speaking more confidently about royal courts and high politics and dynastic grandeur, and above all the attempts to give specific particular people a sense of personality and personal biographies that you generally expect out of a pop history book. Which does make sense, given that those are the only periods where we really have enough textual evidence to confidently name and ascribe significance to any particular people – overwhelmingly dynasts and war-leaders, because of course those are the (almost invariably) men who constructed stelae and covered the walls of temples with testaments of their own greatness.

This means that you do get more of a look into nuts and bolts of knowledge production that you do in most histories – a passage about the development of chocolate drinks as elite consumption is framed with the discovery of cocoa residue on preclassic ceramic vessels, one about human sacrifice by the discovery of skeletal remains in cenotes near major architectural sites, that sort of thing. Similarly, just about every single discovery or theory is credited to one or a few specific academics who initially made it. Which will be either incredibly interesting or the dullest thing in the world, depending on one’s tastes.

The text is mostly incredibly dry and expository in tone, which makes the points where a real sense of personality and subjective opinion leaks through interesting. And endearing, at least to me, but I just find there to be something instantly likeable about the sort of academic myopia which considers human sacrifice and mass famine from the point of view of the universe but is roused to passionate rage by suburban sprawl building over unexamined archaeological sites.

I knew little enough about the specifics of Maya civilization going into this that just relaying everything that struck me reading this would turn this review into a novella. But the way that lowland urbanization and agriculture were based around, not rivers like just about every other culture I’ve read on, but cenotes (and artificially constructed simulacra thereof) in the limestone to capture enough rainwater to last through the dry season was just fascinating. The fact that, the region’s reputation for inexhaustible lushness notwithstanding, the soil the Maya relied upon was very thin and in most cases totally degraded after just a few years of agriculture as well. (Speaking of, the theorizing about how diet changed over the ages and how this related to population movements and density was just fascinating).

The book really wasn’t that interested in the specifics of mythology or divine pantheons beyond how they showed up on engravings and ornamentation – there’s no bestiary of gods or anything – but there’s enough of that ornamentation for it to be a recurring topic anyway. I admit I still find the fact that there’s this great primordial pre-classic god-monster which in the modern era is just called ‘Principle Bird Deity’ deeply amusing.

The book is deeply interested in the Maya calendar and time-keeping. Along with the monumental architecture it’s pretty clearly the thing that the authors find most impressive and awe-inspiring about Classical Mayan culture. There’s enough time dedicated to explaining it that I even pretty much understood how the different counts and levels of timekeeping interacted by the end of the book.

One beat the book kept coming back to (which I admit suits my biases quite well) is that there’s just no sense in the Maya were ever isolated or pristine. Cultural influence coming down from the Valley of Mexico waxed and waned, but on some level it was constant – Mesoamerica was a coherent cultural unit, and the similarities in philosophy and culture (not to mention material goods) between cultures within it are too blatant to ignore. The book theorizes that the population levels reached in the Yucatan before the Spanish Conquest really couldn’t have been supported by local maize agriculture, and instead cities were probably sustained by harvesting and exporting from the salt flats (among the best in the Americas) they controlled access to.

Even beyond trade, there’s several points where ruling dynasties were toppled or installed by armies ranging down from Mexico. The Olmecs and Toltecs make repeated appearances. Even the conquistadors conquest of the Highlands was really only possible because the few hundred Spaniards who got all the credit were marching alongside several thousand indigenous allies.

Speaking of – it’s really only an aside to an epilogue, but given I mostly know the Anglo-American history here, it did kind of strike me how...traditionally imperialist the Spanish were, compared to the more-or-less explicitly genocidal rhetoric I’m used to. If you were an indigenous potentate or ruler enthusiastically selling out to the Spanish Crown was significantly more likely to actually work out for you than trusting a treaty with the US of A, anyway (well, for a while. Smallpox comes for everyone),

Then again, the book does mention that the newly independent Mexican and Central American states in the 19th century were actually significantly worse for the Maya than the Bourbons had been (with things reaching their nadir with the genocidal violence of the 1980s in Guatemala), so maybe that’s it.

Anyway, the book is illustrated, and absolutely chock full of truly beautiful photography and prints on just about every other page. Even if you never actually read it, it would be a great coffee table book.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mesoamerica

The precolonization time periods of Mesoamerica, which covers modern-day Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador and parts of Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica are divided into different periods than those in Europe and the Middle East. Part of this is simple separation, though other reasons include geography (that Mesoamerica has oceans on both sides and between two much larger north-south oriented land masses as well as the minerals available) and climate (a complex mixture of lowlands, highlands, and sub-tropical and tropical climates in the lowlands to cool and dry in the highlands).

Humans reached the area approximately 18000 BCE. From then until about 8000 BCE is known as the Paleo-Indian or, less commonly, the Lithic period, followed by the Archaic period which ended about 2000 BCE, followed by the Preclassical until about 250 CE, the Classical until 900 CE, then the Postclassical, which ended with the Spanish colonization around 1500 CE.

The Paleo-Indian era covers the time period from when people arrived in the area and began using agriculture, pottery, and other skills needed to maintain life. This time period covered hunter-gatherer civilizations and the development of field-based agriculture. This period is fairly similar to the Stone Age in Europe and the Middle East.

During the Archaic period, permanent settlements were established, followed by pottery and loom weaving, allowing class divisions to begin to appear. Trade networks also developed, within short distances at first, then further afield, for stones like obsidian and chert (a fine grained sedimentary rock formed of microcrystaline quartz).

By Gary Todd - https://www.flickr.com/photos/101561334@N08/9764925512/, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=96186719

During the Preclassical period, large-scale ceremonial architecture, cities, states, and writing developed. With the development of writing, we can know what the groups of people called themselves. Some of these are the Olmec, who lived around La Venta and San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, the Zapotec civilization, around the Valley of Oaxaca, Teotihuacan, in the Valley of Mexico, and the Maya, in the Mirador Basin.

By amslerPIX - https://www.flickr.com/photos/amslerpix/48762494738/, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=113266497

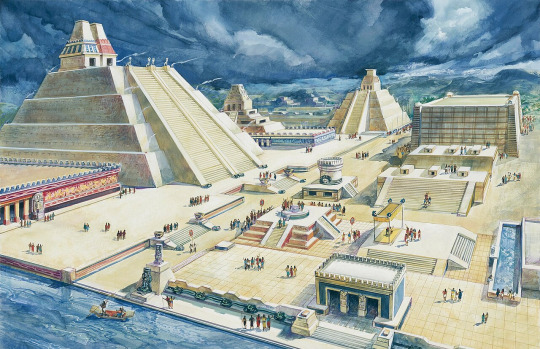

The Classical period was defined by the independent city-states of the Maya and the beginnings of political unification of central Mexico and the Yucatán. Differences in regional cultures manifested themselves until the city-state of Teotihuacan began to dominating the Valley of Mexico, though we don't know much about the culture of the area due to Teotihuacanos not having a culture of writing. The city-state of Monte Albán dominated the Valley of Oaxaca. Though we have some of their writing, we haven't been able to decipher it yet. They did leave a highly sophisticated artistic culture as well, which spread through the area.

By Attributed to Diego Rivera - TheSun.co.uk - https://www.thesun.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/NINTCHDBPICT000416684675.jpg, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=145523789

The Postclassical period saw the collapse of many of the great nations of the Classical period, though the Oaxaca, the Maya of Yucatan (such as the city of Chichen Itza and Uxmal), and the Cholula continued. This period is thought to have seen an increase in warfare, though there were technological advancements in engineering, weaponry, and metallurgy occurred. There was also a lot more movement and population growth during this time as well, especially after about 1200 CE, and experiments in government. The Toltec dominated in the 9-10th centuries then collapsed. The Maya united for a while under Mayapan and the Oaxaca under Mixtec rulers. The Aztec Empire rose in the 15th century and began conquering the Valley of Mexico. This was also the beginning of a renaissance of fine arts and sciences.

By Karnhack - karnhack.com, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24111651

The Spanish conquest of the area was aided by native people who wanted allies against the Aztec Empire. After this, much of the culture of the area and many of the people were destroyed by the Spaniards.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maya, Late Preclassic 300 BCE-300 CE 13.34 cm x 11.75 cm x 4.76 cm (5 1/4 in. x 4 5/8 in. x 1 7/8 in.) fuchsite (muscovite)

This muscovite (fuchsite) mask is carved in the shape of a human face. Pairs of holes can be seen on the forehead, chin, below the eyes, and in the sides. A massive drill was applied to the back to remove most of the stone until there was only a thin surface to be pierced by a small drill. The perforations were probably used to attach the work to cloth that was then wrapped around the head of someone performing a dance. Alternatively, the piece may have been donned by an individual participating in a special ceremony or placed directly in a burial. Considering this object’s small size, another explanation for its use is that it was attached to a belt or chest pendant.

Mask

Maya, Late Preclassic, 300 BCE-300 CE

The origin of the stone that was used to make this mask reveals the exchange network present during pre-Hispanic times in the Maya area. Muscovite is believed to come from the eastern highlands of Guatemala, near the Motagua River.

#history#art#carving#masks#preclassic period#mesoamerica#maya#guatemala#motagua river#muscovite#fuchsite

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

~ Fragmentary Figure.

Culture: Olmec

Period: Middle Preclassic

Date: 900-300 B.C.

Medium: Jadeite

#ancient#ancient art#history#museum#archeology#ancient sculpture#ancient history#archaeology#olmec#mexico#Mesoamerica#mexican#middle Preclassic#fragmentary figure#figure#jadeite#900 b.c.#300 b.c.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Archaeologists believe that around 417 cities, towns, and villages made up the unified civilization.

Remains of architectural forms and patterns, ceramics, sculptural art, architectural patterns, and unifying causeway constructions.

The magnitude of the labor int he construction of massive platforms, palaces, dams, causeways, and pyramids dating to the Middle and Late Preclassic periods, suggests a power to organize thousands of workers.

#history#archeology#archeologicalsite#discovery#ancient#ancient maya#ancient city#ancient civilizations#guatemala#rainforest#lidar technology#radar

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vase of an "Acrobat" from Tlatilco, Mexico dated between 1000 - 300 BCE on display at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, Mexico

This magnificent vase represents th ecomplex religious ideology which was predominantly during the Middle Preclassic period. The physical effort of an acrobat or contortionist is recreated by means of highly perfected potter's techniques.

Tlatilco was one of the first chiefdoms to emerge out of Lake Texcoco. It was especially well known for high quality pottery like this that used Toltec imagery.

Photographs taken by myself 2024

#art#archaeology#history#mexican#mexico#ancient#national museum of anthropology#mexico city#barbucomedie

3 notes

·

View notes