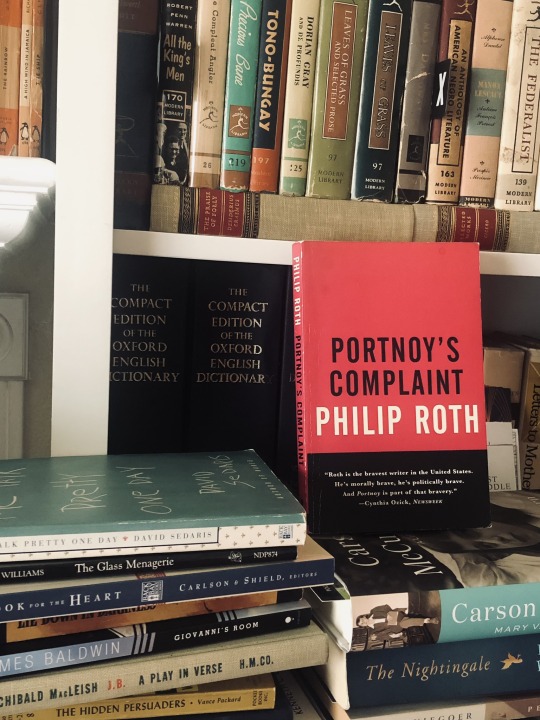

#portnoy's complaint

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Imagine reading a fictional novel and coming across a person you actually, literally know. I wrote about this in my new IG post.

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Fran Ross, Oreo

#MANY ARE SAYING THIS#the title of my college paper on oreo‚ portnoy's complaint‚ & the adventures of augie march but also the engraving on my tombstone#fran ross#oreo#i read much of the night and go south in the winter

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jerry Lewis Cinema presents Portnoy's Complaint

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

(JTA) – A global bestseller by a Jewish Holocaust victim; a novel by a beloved and politically conservative Jewish American writer; a memoir of growing up mixed-race and Jewish; and a contemporary novel about a high-achieving Jewish family are among the nearly 700 books a Florida school district removed from classroom libraries this year in fear of violating state laws on sexual content in schools.

The purge of books from Orange County Public Schools, in Orlando, over the course of the past semester is the latest consequence of a conservative movement across the country — and strongest in Florida — to rid public and school libraries of materials deemed offensive. While the vast majority of such challenged and removed books involve race, gender and sexuality, several Jewish books have previously been caught in the dragnet.

The Orange County case is unusual for the sheer volume of books removed — 699 including some duplicates, according to documents the district provided — and for the unusually large number of books about the Holocaust and Jewish identity included among them. They included:

“Suite Française,” by Irène Némirovsky, a Ukrainian-French Jewish writer who wrote her novel in secret under German occupation before perishing in Auschwitz

“Herzog,” a semi-autobiographical novel by Jewish writer Saul Bellow, an outspoken cultural conservative whose son Adam Bellow is a publisher of right-wing Jewish books

“Black, White and Jewish: Autobiography of a Shifting Self,” by Rebecca Walker, feminist theorist and daughter of author Alice Walker, whose own antisemitic comments and writings have faced scrutiny in the past

“Bee Season,” a novel about a high-achieving family of Jewish scholars and cantors, by Myra Goldberg

“The Splendid and the Vile,” a nonfiction history book about Winston Churchill’s decision to fight Hitler’s forces during World War II, by Erik Larson

The collected plays of Lillian Hellman, a Jewish playwright and left-wing activist who was accused of Communist activities

“The Storyteller,” a novel dealing with the Holocaust by bestselling author Jodi Picoult

“The Reader,” a German novel about the aftermath of the Holocaust by Bernhard Schlink

“Sophie’s Choice,” a bestselling novel also about the aftermath of the Holocaust by William Styron

“The Freedom Writers Diary,” a nonfiction compilation of several high school students’ diaries inspired by their teachers’ efforts to instruct them on the Holocaust and Anne Frank

“Books are removed from classrooms with deference to House Bill 1069,” district spokesperson David Ocasio told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, referring to a Florida law signed this year that heavily restricts instruction and classroom materials about human sexuality.

No individual reasoning was given for each book’s removal, but Ocasio said that all of the books had been marked as “not approved for any grade level.” He added that every book will go through a secondary review to determine if it will be restricted to certain grade levels or “weeded from the collection” altogether.

Some of the books on Orange County’s list have come under scrutiny in the past for removals from other districts. “The Storyteller” was the subject of widespread press coverage after a member of the right-wing activist group Moms For Liberty successfully pushed for its removal from a different Florida school district earlier this year. “Sophie’s Choice” was recently removed from a third Florida school district at the behest of a Jewish parent’s challenge; both parents said their challenges were due to sexual content.

Other outwardly Jewish books on the list, including “The Reader” and Philip Roth’s “Portnoy’s Complaint,” contain explicit sexual content. Non-Jewish World War II novels “Slaughterhouse-Five” and “Catch-22” were also pulled.

Among the hundreds of other books flagged for removal in the district were frequently challenged books like “Gender Queer” and “The Handmaid’s Tale,” as well as literary standards like Milton’s “Paradise Lost” and Maya Angelou’s “I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings,” and children’s fare like a book based on Disney’s “The Incredibles.” Some items were listed more than once.

Other districts in Florida this year have pulled an illustrated adaptation of Anne Frank’s diary in order to comply with the state law.

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

Words aren't only bombs and bullets—no, they're little gifts, containing meanings.

(Philip Roth, Portnoy's Complaint, 1969)

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yes, this was my kind of girl, all right—innocent, good-hearted, zaftig, unsophisticated and unfucked-up. Of course! I don’t want movie stars and mannequins and whores, or any combination thereof. I don’t want a sexual extravaganza for a life, or a continuation of this masochistic extravaganza I’ve been living, either. No, I want simplicity, I want health, I want her!

Philip Roth - 'Portnoy’s Complaint'

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Got The Tartar Steppe's adaptation off the list some additional adaptations of books I've read and need to get to watching

Roadside Picnic

Insatiability

Berlin Alexanderplatz

East of Eden

The Grapes of Wrath

Canary Row

Barabbas

The Trial

Confessions of Zeno

Cass Temberline

Arrowsmith

Intruder in the Dust

Pedro Paramo

Ulysses

The Fixer

A High Wind in Jamaica

Portnoy's Complaint

#prob forgetting some or some have films and I just don't know about it#most of these I read from 2020 on#the book I read furthest in the past but never watched the film is arrowsmith which was a very long time ago#tbh some of these adaptations I don't think will be very good which is part of the reason I haven't yet#but I should see for myself#some I have high hopes and I really want to see tho#and yes I know some of these are prob surprising that I haven't already watched#anyway just a random thing for my own memory and if you have any feelings about these adaptations feel free to chime in#talks

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

100 Books to Read Before I Die: Quest Order

The Lord Of The Rings by J. R. R. Tolkien

In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

The Good Soldier by Ford Madox Ford

Under The Net by Iris Murdoch

American Pastoral by Philip Roth

The Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kundera

Animal Farm by George Orwell

Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson

Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

Atonement by Ian McEwan

Crime And Punishment by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

The Grapes Of Wrath by John Steinbeck

Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie

Lucky Jim by Kingsley Amis

Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut

The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway

Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

A Passage to India by EM Forster

Of Human Bondage by W. Somerset Maugham

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie by Muriel Spark

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay by Michael Chabon

If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller by Italo Calvino

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams

1984 by George Orwell

White Noise by Don DeLillo

The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas

The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner

The Stranger by Albert Camus

Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

Oscar And Lucinda by Peter Carey

The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle by Haruki Murakami

Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner

To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee

Lord of the Flies by William Golding

The Portrait of a Lady by Henry James

The Call of the Wild by Jack London

Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov

Beloved by Toni Morrison

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy by John Le Carré

Austerlitz by W. G. Sebald

The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne

Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh

Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller

The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton

Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf

The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers

The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster

Ulysses by James Joyce

Scoop by Evelyn Waugh

Haroun and the Sea of Stories by Salman Rushdie

Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe

Middlemarch by George Eliot

Are You There, God? It’s me, Margaret by Judy Blume

Clarissa by Samuel Richardson

Moby-Dick by Herman Melville

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

Herzog by Saul Bellow

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz

Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë

Don Quixote by Miguel De Cervantes

A Bend in the River by V. S. Naipaul

A Dance to The Music of Time by Anthony Powell

The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson

Go Tell It On The Mountain by James Baldwin

Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys

Catch-22 by Joseph Heller

The Rainbow by D. H. Lawrence

Song of Solomon by Toni Morrison

I, Claudius by Robert Graves

Nostromo by Joseph Conrad

The Tin Drum by Gunter Grass

Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert

The Catcher in the Rye by JD Salinger

Charlotte’s Web by E. B. White

Tom Jones by Henry Fielding

His Dark Materials by Philip Pullman

Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

Little Women by Louisa M Alcott

Great Expectations by Charles Dickens

Portnoy’s Complaint by Philip Roth

Watchmen by Alan Moore

One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez

Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe

Tristram Shandy by Laurence Sterne

On the Road by Jack Kerouac

The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler

The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame

To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf

The Corrections by Jonathan Franzen

The Trial by Franz Kafka

Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston

Money by Martin Amis

David Copperfield by Charles Dickens

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

" Posso sempre mentire riguardo al mio nome, posso mentire sulla scuola, ma che balla racconto su questo fottuto naso? «Lei sembra una persona molto ammodo, signor Porte-Noir, ma perché va in giro coprendosi il mezzo della faccia?» Perché d’improvviso il mezzo della mia faccia è andato a farsi benedire! Perché è andata a farsi benedire la ciliegina della mia infanzia, quel cosino grazioso che la gente ammirava quando giravo in carrozzina e, venghino signori, il mezzo della mia faccia ha cominciato a protendersi verso Dio! Porte-Noir e Parsons un cazzo, amico, tu sul mezzo della faccia ci porti scritto EBREO… guardate che canappia si ritrova, per carità di Dio! Questo non è un naso, è un idrante! Mena le tolle, giudeo! Via dal ghiaccio e lascia in pace le ragazze! Ed è vero. Appoggio la testa sul tavolo e, con una matita, traccio il mio profilo su uno dei fogli intestati di mio padre. Ed è terribile. Com’è potuto accadermi, mamma, a me che ero cosí grazioso nella carrozzina! Nella parte superiore ha cominciato a puntare verso il cielo mentre, nel contempo, laddove la cartilagine si interrompe a metà discesa, ha preso a rinculare verso la bocca. Un paio d’anni e non riuscirò piú neppure a mangiare, questo aggeggio si troverà direttamente sulla traiettoria del cibo! No! No! Non può essere! "

Philip Roth, Lamento di Portnoy, traduzione di Roberto C. Sonaglia, Mondadori (collana Oscar Classici Moderni n. 165), 2022¹², pp. 119-120.

[Edizione originale: Portnoy's Complaint, Random House, NYC, 1969]

#Philip Roth#Lamento di Portnoy#letture#leggere#adolescenza#Roberto C. Sonaglia#razzismo#corpi#libri#stereotipi#società americana#borghesia#famiglia#ebraismo#ebraicità#fanatismo religioso#citazioni letterarie#America#bellezza#discriminazione#New Jersey#Newark#XX secolo#adolescenti#letteratura americana del '900#lingua yiddish#narrativa#ebrei#pregiudizi#eredità genetica

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Continuing Literary Canon

100. Federico Garcia Lorca, Blood Wedding

101. Jean-Paul Sartre, No Exit

102. Albert Camus, The Stranger

103. Eugene Ionesco, The Bald Soprano

104. William Butler Yeats

105. George Bernard Shaw, Pygmalion

106. Thomas Hardy, The Return of the Native

107. Joseph Conrad

108. D.H. Lawrence

109. Virginia Woolf

110. James Joyce

111. Samuel Beckett, Waiting for Godot

112. Aldous Huxley, Brave New World

113. W. H. Auden

114. George Orwell, 1984

115. Franz Kafka - Metamorphosis

116. The Trial

117. Bertolt Brecht, Mother Courage

118. Thomas Mann

119. Andrei Bely, Petersburg

120. Mikhail Bulgakov, The Master and Margarita

121. Boris Pasternak, Dr. Zhivago

122. Edwin Arlington Robinson

123. Robert Frost

124. Edith Wharton

125. Willa Cather

126. Gertrude Stein

127. Wallace Stevens, "Sunday Morning"

128. Theodore Dreiser, Sister Carrie

129. Sherwood Anderson

130. T.S. Eliot - "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock"

131. "The Waste Land"

132. "The Hollow Men"

133. "The Journey of the Magi"

134. Katherine Anne Porter

135. Eugene O'Neill, Long Day's Journey into Night

136. F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

137. William Faulkner - The Sound and the Fury

138. Ernest Hemingway -The Old Man and the Sea

139. A Farewell to Arms

140. John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath

141. Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God

142. Eudora Welty

143. Flannery O'Connor

144. Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita

145. J. D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye

146. Tennessee Williams - A Streetcar Named Desire

147. The Glass Menagerie

148. Arthur Miller, Death of a Salesman

149. Toni Morrison, Song of Solomon

150. Joyce Carol Oates

151. Philip Roth, Portnoy's Complaint

152. John Updike - A&P

153. The Witches of Eastwick

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books Read in 2023 - If you're curious about any of them, please ask! I love talking about books

Rebecca (Daphne du Maurier)

Introduction to American Deaf Culture (Holcomb)

The Colour of Magic (Pratchett)

The Autistic Trans Guide to Life

Luda (Morrison)

The Moon is a Harsh Mistress

Genderqueer: Voices From Beyond the Sexual Binary

The Mask of Benevolence: Disabling the Deaf Community

Between Two Worlds (Sinclair)

Under the Skin (Faber)

When Time Stopped: A Memoir of My Father’s War and What Remains

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

Portnoy’s Complaint

Being Heumann: An Unrepentant Memoir of An Disability Rights Activist (Judith Heumann)

Sex at Dawn: The Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality

This is Moscow Speaking (Arzhak/Yuli Markovich Daniel; tr by Stuart Hood, Harold Shukman, John Richardson)

The Call-Girls (Koestler)

The Essential Dykes to Watch Out For

Homintern

A Scanner Darkly

The Trauma of Caste (Soundararajan)

Shards of Honor (Bujold)

The Origin of Virtue

Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers

Dreadnought

Children of the Arbat (Rybakov; tr by Harold Shukman)

The Gay Metropolis: The Landmark History of Gay Life in America

Janissaries (Jerry Pournelle)

The Disability Studies Reader (Davis)

Fat Off, Fat On: A Big Bitch Manifesto

The Book of Dust: The Secret Commonwealth

Inseparable (de Beauvoir)

World’s End (T. Coraghessan Boyle)

American Melancholy (Joyce Carol Oates)

Transgender Children and Youth (Nealy)

Disgrace (Coetzee)

The Light Around the Body (Bly)

The Hangman’s Daughter (Pötzsch)

Encounters: Two Studies in the Sociology of Interaction (Goffman)

The Trouble with Tink (Thorpe)

Gender Advertisements (Goffman)

And the Band Played On

Fairy Dust and the Quest for the Egg

The Trouble with Normal: Sex, Politics, and the Ethics of Queer Life

Old Norse Poems: The Most Important Non-Skaldic Verse Not Included in the Poetic Edda (tr. by Hollander)

Arts of the Possible: Essays and Conversations (Rich)

Ladies Almanack (Barnes)

Over the Hill (Copper)

Fairy Haven and the Quest for the Wand

The Poetic Edda (tr. by Bellows)

Paris Peasant (Aragon, tr. by Taylor)

Open Borders: The Science and Ethics of Immigration

Stigma (Goffman)

Rubyfruit Jungle

Fairies and the Quest for Never Land

Sight Unseen (Kleege)

The Homosexuality of Men and Women (Hirschfeld, tr. by Lombardi-Nash)

Bea Wolf

New Selected Stories (Thomas Mann, tr. by Searls)

Gay Bar (Jeremy Atherton Lin)

Patsy Walker, AKA Hellcat

Treatise on Style (Aragon, tr. by Waters)

Diana (Frederics)

The World I Live In (Keller)

Christopher and His Kind (Isherwood)

Put Out More Flags (Waugh)

Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man (Mann; tr. and introduced by Morris, Lilla, Rainey)

On Our Own (Judi Chamberlin)

All Boys Aren’t Blue

Artemis (Weir)

Goethe und die Demokratie

Dress Codes (Howey)

Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing

Forms of Talk (Goffman)

Sister Gin

The Decameron (Boccaccio; tr. by Musa and Bondanella)

Elric of Melniboné (Moorcock)

Paradiso (tr. by Hollander and Hollander)

My Mistress’ Eyes are Raven Black

Mademoiselle de Maupin (Gautier)

The Magic Mountain (Mann, tr. by Lowe-Porter)

Home to Harlem (McKay)

The Sailor on the Seas of Fate (Moorcock)

#books#books read in 2023#book reading#my reading list actually got longer this year#again#it's over 11 pages long#and some of the entries are just authors I want to check out

5 notes

·

View notes