#polypus

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The sea monster Polypus (meaning “many-footed”) was used to describe many animals, from the lobster to the centipede to the octopus. While Olaus Magnus drew a giant lobster here, his text describes an octopus, showing the true confusion about what lived in the sea.

On the Carta Marina, by Olaus Magnus (1539) Marine map and Description of the Northern Lands and of their Marvels, most carefully drawn up at Venice in the year 1539 through the generous assistance of the Most Honourable Lord Hieronymo Quirino.

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

Karkaskuttle

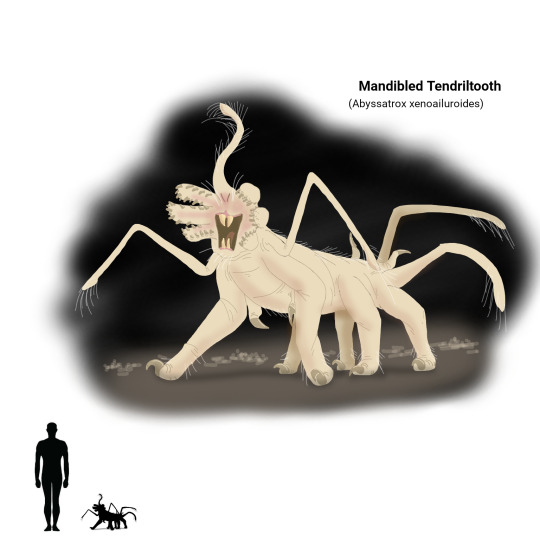

RARITY: ★☆☆☆☆ | THREAT: ★★☆☆☆ SIZE: Smallest are lobster-sized, but they never stop growing; the largest can reach the size of a truck, at which point they are called “lobstrosities”.

HABITAT:

Found all along the coastline. Most encounters take place on the beach, but they’re also found in deeper waters and in the harbor, leading to sightings from fishermen.

OVERVIEW:

Fishermen have long told tales about lobsters that were far too big to fit on any plate. As it turns out, some of those catches weren’t lobsters at all, but their prehistoric relative, the karkaskuttle. These wicked big crustaceans are usually scavengers and can be seen feeding on dead matter that sinks to the sand in oceans. They use their meaty claws to strip off pieces of their food, and – when the situation calls for it – have also been known to use them to bash their prey to death while it’s still alive.

They are occasionally caught by fisherman and mistaken for mutated lobsters, or just one of those “strange local variants”. Sometimes they even make it to the supermarket where they’re sold as food, and some of Wicked’s Rest’s restaurants even tout them as “specials”. However, these are just the smallest karkaskuttles – many of them grow far too large to fit in a lobster trap and it’s theorized they never stop growing. Fortunately, they typically leave people alone unless they’re mistaken for dead matter (such as the undead) or they disturbed the karkaskuttle in some way. They are pretty grumpy though, so it’s not all that hard to disturb them.

ABILITIES:

A karkaskuttle can easily snip a person’s limb off or crush bones with its over-sized claws.

Their tough exoskeleton prevents most weapons from piercing them.

They have keen senses and can find dead material miles away, including undead beings.

They’re frequently found in large groups, though they are not social creatures and will aggressively fight over a meal. They don’t work as a team, but all of them will want to eat you.

The bigger karkaskuttles can pose a real threat when they decide to leave the ocean and pursue meals along the beach. They can reach massive proportions, with some of the bigger ones seen being as large as a truck.

WEAKNESSES:

Normally the hard exoskeleton of a karkaskuttle protects them from physical harm. However, like all crustaceans, karkaskuttles must shed their exoskeleton every once in a while to grow, during which they are extremely vulnerable to attack.

If your encounter with one of these crabby crabs doesn’t align with their molt, fire magic or abilities may be used to slowly cook them inside their shells.

They are simple-minded crustaceans who can easily be distracted by a bigger, more tempting meal than your fleshy body.

VARIANTS

POLYPUS:

Often fancifully drawn in unknown seas on medieval maps, the polypus combines the features of giant lobsters and octopuses, moving on a centipede-like mass of both tentacles and segmented crustacean legs. They are ambush predators who can change color to blend in with surrounding terrain. A polypus doesn’t immediately kill the prey it snatches, instead taking victims back home – usually a seaside cave – before skinning and eating them. Discarded skins washing up on the beach are a sign that a polypus lair might be nearby.

#karkaskuttle#polypus#monsters#supernatural rp#town rp#horror rp#literate rp#lsrpg#new rp#established rp

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dopo l’incredibile ondata di revival black metal melodico anni ’90, Nagash – uno dei contribuenti principali dell’ondata originale - forse colto da una nostalgia di mezz’età ha deciso in un sol colpo di ripristinare i Covenant (questa volta scritti senza “the K”) e i Troll. Ascoltando Trolldom è come se ci trovassimo ancora fra il 1997 e il 1998, dove le tastiere sono sì l’elemento principale di questo black metal oscuro ma bagordo, con melodie quasi danzerecce in stile officina dei goblin o caverna dei nani. Il modello è quello di Drep de Kristne anche se uno dei risultati più nuovi e sorprendenti è "Angerborda" dove i synth trance si mascherano perfettamente fra la strumentazione blackmetal. Gli ascoltatori di un certo pelo si ricorderanno subito gli Aborym ma non c’è atmosfera marziale né apocalittica nei Troll, solo una corsa sfrenata verso gli eccessi dell’alcol e della follia. "Ancient Fire" ha i synth in stile Limbonic Art che dialogano con le chitarre mentre tutto il resto dell’album fila liscio coerente a sé stesso senza particolari accelerazioni o sfrenate di violenza.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Huntale Season II -Episode 5 : Page 181-185

EPISODE 5 - Page 186-190 : (18/09/2023)

Reading the chapters of Seasons I is necessary : chapter 1 : www.deviantart.com/antoine175/… chapter 2 : www.deviantart.com/antoine175/… chapter 3 : www.deviantart.com/antoine175/… chapter 4 : www.deviantart.com/antoine175/… chapter 5 : www.deviantart.com/antoine175/… chapter 6 : www.deviantart.com/antoine175/… chapter 7 : www.deviantart.com/antoine175/… chapter 8 : www.deviantart.com/antoine175/… chapter 9 : www.deviantart.com/antoine175/… chapter 10 : www.deviantart.com/antoine175/… chapter 11 : www.deviantart.com/antoine175/… chapter 12 : www.deviantart.com/antoine175/…

Seasons II : chapter 1 : www.deviantart.com/antoine175/… chapter 2 : www.deviantart.com/antoine175/… chapter 3 Part.1 : www.deviantart.com/antoine175/… chapter 3 Part.2 : www.deviantart.com/antoine175/… chapter 4 Part.1 : www.deviantart.com/antoine175/… chapter 4 Part.2 : www.deviantart.com/antoine175/… Beginning of chapter 5 : www.deviantart.com/antoine175/…

#undertale#undertale_comic#undertale_au#drixx#helios#polypus#unger#freeze#abomination#Cyrus#Kore#Mantis#khépri#ibris#Wilson_Huntale#Abi_Huntale#Scott_Huntale#Amanda_Huntale#Joseph_Huntale

0 notes

Text

COLOSSAL

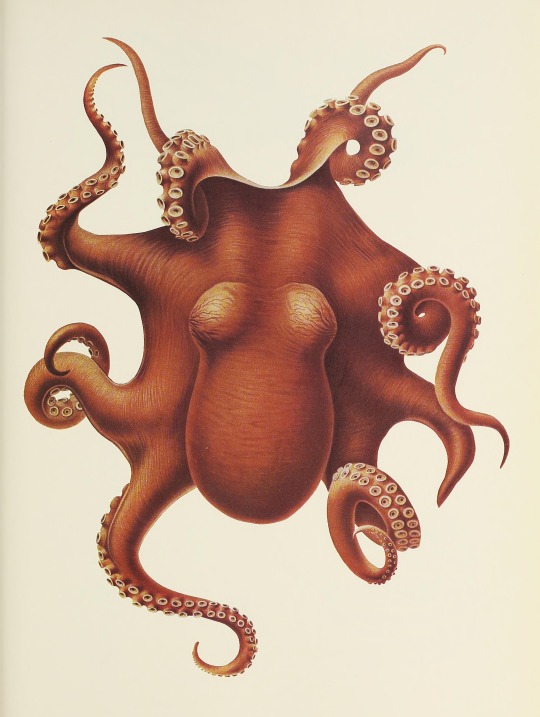

Carl Chun, Polypus levis, from Die Cephalopoden (1910–15), color lithograph, 35 × 25 centimeters. Image from the Biodiversity Heritage Library/Contributed by MBLWHOI Library, Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Library, Massachusetts.

NNtonio Rod (Antonio Rodríguez Canto), Trachyphyllia, from Coral Colors, (2016). Image © NNtonio Rod

Despite thousands of years of research and an unending fascination with marine creatures, humans have explored only five percent of the oceans covering the majority of the earth’s surface. A forthcoming book from Phaidon dives into the planet’s notoriously vast and mysterious aquatic ecosystems, traveling across the continents and three millennia to uncover the stunning diversity of life below the surface.

Spanning 352 pages, Ocean, Exploring the Marine World brings together a broad array of images and information ranging from ancient nautical cartography to contemporary shots from photographers like Sebastião Salgado and David Doubilet. The volume presents science and history alongside art and illustration—it features biological renderings by Ernst Haekcl, Katsushika Hokusai’s woodblock prints, and works by artists like Kerry James Marshall, Vincent van Gogh, and Yayoi Kusama—in addition to texts about conservation and the threats the climate crises poses to underwater life.

Ocean will be released this October and is available for pre-order on Bookshop. You also might enjoy this volume devoted to birds.

#Carl Chun #polypus #cephalopoden

#1910-15 #lithograph #ilustration

#original art #science #art #xpuigc

#Carl Chun#Polypus levis from Die Cephalopoden#1910–15#lithograph#illustration#original art#art#xpuigc

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I had an idea of making a Leshy of Order a butterfly or moth, since many (like me) make him more of a caterpillar than a worm (or maybe like a bagworm). So making him a butterfly would make him an opposite in change. You could also add a flower theme, like with Chaos!Leshy's bush theme

Making a design for the other bishops of Goat's dimension is harder than I thought

Sure they will mainly have switched main domains, like Leshy is now mainly Order than Chaos. But also it's hard to know wich animal they'll be switched to? Lamb and Goat are somewhat the same "family",Narinder I changed to be a dog, so "opposite in theme".

Some are easier like Heket I could make a Mushroom, kallamar an octop instead of squid...now... shamura and leshy.... what the hell is the opposite or similar to a fucking worm bush and spider...

And to add to that I got the idea to change their positions as oldest to youngest just to add more changes I guess....

#Mushroom Heket and octopus Kallamar are great too#But then I feel like Kallamar's name could be changed to something like Polypus#I'm at a loss for Shamura though#Maybe an owl so we keep the connection to the greek Athena?#hmmmm#cotl

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It's #WorldOctopusDay! Pictured here a “Polypus levis Hoyle” from a 1910 publication on the German Deep-Sea Expedition of 1898, led by Leipzig University Professor of Zoology, Carl Chun. Buy it as a print here: https://t.co/oyBmkE9VTr

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

An octopus of the species Muusoctopus levis (referred to in the text by the outdated name "Polypus levis") from Carl Chun's The Cephalopoda (1975 translation of 1910-1914 volume). Full text here.

800 notes

·

View notes

Text

🐙OCTOPUS (Polypus) “The octopus hides deep in the sea, but always remains where secrets and desires entwine.” – Unknown

The octopus is a mysterious and elusive creature, hiding deep within the ocean, symbolizing greed, lust, and pretense. Secretly lurking in the hidden corners of the sea, with its many arms, it manipulates its surroundings just as the human soul may attempt to control or disguise its desires and intentions. The octopus embodies gluttony, not only representing an appetite for food but also the excessive desire for possession.

In ancient myths, the octopus is not just a marine predator but also a figure that brings hidden intentions and secret desires to the surface, encouraging us to face our inner shadows. Pretended goodwill and secretive manipulation may manifest, just as the octopus’s arms quietly but effectively wrap around the world.

The octopus reminds us that the apparent goodness and the deeper desires hidden within pretense remain powerful until we confront them.

#animal photos#nature#nature photo#nature photography#photography#animals#wildlife#octopus#symbols#spirituality

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

From a single founding species descended from the stellasnoots that found a suitable home in the secluded caverns of Arcuterra, the daggoths, a clade of subterranean molrocks of distant relation to the rattiles, have since diversified over the last 25 million years in isolation. As the cave systems naturally expanded over the course of many millennia, the ecosystem too grew bigger, as it created more room for a wider and more diverse range of species to thrive.

Over millions of years, the upper chambers of the cave system became more open to the surface, resulting to not only a slight but significant influx of oxygen into the ecosystem but also nutrients from the surface, such as organic detritus and the abundant droppings of transient species such as roosting ratbats that nest in the surface chambers, washed down into the caves by rain. These fuel the abundant growth of bacteria, mocklichens and meatmoss, the cavern ecosystem's producers in the absence of plants and sunlight. With an abundance of food, space and, relatively speaking, oxygen, the life of the caves have since grown more diverse and complex than ever before.

Many of the daggoths have remained unchanged from the first forms that were the earliest colonists of the caves. The gothtles, small, mouse-sized insectivores, continue to stick to the ancestral lifestyle, as small, slow-moving ambush hunters that relied on stealth to pounce on insects. Yet the ancestral niche now comes with one drastic difference: they are no longer the apex predators of their environment. Abundant and fast-breeding, the gothtles are now the lower rung of the food chain as larger predators have since evolved from other branches of their kin.

While slower basal gothtles now rely on camouflage by scent and touch to evade enemies, numerous lineages have since evolved speed and evasiveness in order to outpace their predators. One such group are the xenomures, such as the four-plumed xenomure (Xenomuris tetradactylopluma), with long, slender legs that allow them to scurry quickly across the fungal and meatmoss mats to escape their enemies and hide among the maze-like growths to lose their enemies' trail. Two pairs of modified digits act as antennae fore and aft, giving the xenomures a vivid perception of obstacles in their surroundings while moving quickly in the pitch black darkness. These timid omnivores, in many ways, have come to be the caves' ecological parallel to "typical" rodents like furbils and duskmice on the surface, with some even harvesting and storing fruiting pods of mocklichens in burrow larders to eat later, and thus helping the mocklichens proliferate to new areas.

Other lineages of the small gothtles have also evolved more active lifestyles as dynamics of the ecosystem have changed. Some, such as the long-bodied common skitter (Longicorpomys polypus) developed slender bodies and shorter limbs to specialize in hiding in small crevices in the rock walls, well-protected from predators, where they can feed on the fungal mycelia, the buried "roots" hidden underneath the organic soil-like detritus mats covering the cave floors. Others have become small hunters of their own right, paralleling the chrews and scabbers of the surface, like the earthumb arthoid (Dactylotomys auricheirus), equipped with two front digits bearing pointed claws positioned next to its head almost like ears, that it uses to root out small prey, such as insects, nematodes and wormlike maggoths out of their burrows and out from growths of mocklichens and meatmoss.

Virtually every surface of the cavern system has offered a habitat for life, including the walls and the ceiling of the caves, with the walls and roofs forming elevated "branches" and dangling "vines" of various vegetative plant-analogues, which are fed upon by "browsers" adapted to reach high up on to access fungal growths inaccessible to other ground-dwellers.

The ceilings, in particular, are abuzz with a surprising diversity of organisms dwelling amidst the overhanging stalactites. In particular, the dangling "vines", in reality complex filamentous fungal hyphae nourished by a symbiotic relationship with chemosynthetic bacteria, produce buds that exude an odorous scent, that draws in the feelerflits: flying insects descended from dipteran flies that, with long and very sensitive antennae equipped with tactile, thermal and olfactory receptors, have secondarily regained their power of flight and are able to navigate even without sight and home in on the buds that produce nutritious carbohydrate-rich liquids in return for it spreading its spores.

One descendant of the roof stalac has since adapted to exploit this relationship. The bulbous-snouted budwight (Nasofungiosus imitator) has developed specialized bud-like growths at the end of its nasal tendrils, that sport modified sebaceous glands that excrete a scent similar to those of the vine blooms, the chemicals of which it acquires and secretes by eating the blooms themselves. Then, lying in wait, anchored onto the surface of stalactites or perched amidst the vines, it waves its tendrils in the air in anticipation of an unwary feelerflit blundering into its trap, to be ensnared by seven long and flexible tendrils and passed into the mouth to be eaten.

Curiously, despite its purpose of mimicry, the budwight's tendrils in fact look nothing at all like the vine buds, being simple enlarged growths at the ends of the knobbly nasal appendages. In a world of darkness, appearances are almost entirely insignificant, as prey and predator alike perceive their surroundings with sound, smell and touch, as well as other more remarkable senses like thermo- and electroreception. As such, mimcry revolves around these senses: not even a vaguely-similar imitation to a sighted creature, but a deception at least sufficient to trap its equally-blind prey.

Of the various small daggoths that populate the caves, however, none are as divergent and unconventional as the maggoths: a lineage of neotenic descendants of the mossmulch, a more typical-looking daggoth whose life-cycle has taken unexpected turns to produce one of the greatest regressions in complexity second only to the shroomors.

Measuring only a centimeter or less, the maggoths, such as the basal lichen maggoth (Vermimys simplisticus) are extremely simplified creatures: their respiration takes place almost entirely through their permeable skin, their skeletons, save for their ossified mandible and maxilla, are completely made of only cartilage, and they move entirely through two sets of muscles, an inner layer of longtidunal muscles and an outer layer of concentric muscles that contract and relax alternatingly to undulate them forward. This body plan arose from the mossmulch's early gestation lasting only a few days and producing barely-developed young, basically just self-sufficient and free-living early-stage embryos, adapted to feed constantly on meatmoss and mocklichens by tunneling through them, and, with an abundance of a reliable food source, some species eventually became neotenic, no longer developing limbs and nasal tendrils and ossified skeletons, and simply reproducing in a larger version of their quasi-larval state.

The simplified anatomy and reduction of surplus organs has allowed maggoths to be quite successful in the vast expanses of the subterranean caverns. In particular, their very simple bodies has reduced their development to but a few days, allowing them to shorten their generations to as little as three or four weeks: at the age of twenty-one days, maggoths are already sexually mature and can mate, bearing litters of up to a dozen or more wormlike quasi-larval young at a time once every five or six days. These 3-4 millimeter-long newborns feed off skin secretions made by the females for the first few hours of their life before departing for good, in a last remaining hint of mammalian history in a species so far removed from a typical mammal's form.

Another, unlikely advantage of their simplified anatomy is that it requires far less oxygen, which coupled by their incredibly small body sizes and their respiration through their skin, has led one lineage into a new frontier: the waters of the subterranearn rivers as well as the underground sumps that form bodies of water such as ponds and lakes. Thus arose the hampreys: the first ever aquatic lineage of hamsters on HP-02017 to evolve fully-aquatic respiration and thus be entirely independent of breathing air at the surface. Specialized vessels directly branching from the heart absorb oxygen diffused through their permeable skin, and thus their lungs have been reduced to simple sacs regulating buoyancy. Perhaps more remarkable, however, is the marked reduction of their nervous system, especially the brain: their simple lifestyle and unusual respiration had no need for such an energy-hungry organ as a complex brain, and thus in the hampreys this otherwise very vital organ, once the pride of mammals in their complexity, now has completely atrophied to basically but a brain stem, capable of little more than basic bodily functions and responses to external stimuli, moving through the water in jerky, wiggling movements toward the taste and scent of food and away from the vibrations of danger.

Some hampreys, such as the rasping hamprey (Vermicthymys micronis), are independent creatures teeming in the underground ponds and lakes, scraping off mats of chemosynthetic bacterial colonies using their jaws: an ossified mandible and maxilla bearing two pairs of gnawing incisors--basically the only remaining visual vestige of their rodent ancestry. Some, however, have specialized these remnant teeth for another purpose: the sanguine hamprey (Atrocivermimys haemophilus) has developed elongated teeth and a "lip" that allows its mouth to function as a suction--enabling it to attach to other aquatic daggoths such as tubesnouts and trogadiles and parasitically feed off their bodily fluids.

Not all daggoths are small, however. In the recent eons, as food and space became more available as the caverns grew and became more oxygenated, some of the daggoths began growing in size. While still small compared to outside surface animals, reaching only a maximum of 90 kilograms in the largest "grazers", their size is nonetheless an incredible achievement given their environment and evolutionary history.

The lineage that would give rise to their largest species eventually diversified into low-level grazers, higher-level browsers, generalist omnivores and specialized macro-predators. But most basal of these are the grummlers, with the largest species being the giant grummler (Macroabyssomys maximus). These represent the earliest lineage of daggoths that began expermenting with size, with them resembling the basic daggoth but simply larger. With their increased weight, their multiple digits became more columnar to support their bulk, their reduced metacarpals forming equivalents of shoulder blades to anchor powerful limb muscles, while their phalanges grew stronger and thicker and developed a bony heel-like protrusion on the second-to-the-last phalanx to support a fleshy "sole" pad: in essence turning the spindly fingers of the smaller daggoths into sixteen proper "legs".

The greater grummler is a large and indiscriminate omnivore, feeding on mocklichens, meatmoss, bacterial mats, arthropods, smaller daggoths and carrion. Depending on the species, the several species of grummlers either lean toward a more "grazer" side or a more "carnivore" side: a distinction that is less drastic than surface animals given that some of their "plant" equivalents are technically animals as well, making them more accurately "meat-grazer omnivores" or "carno-herbivores". This dietary ambiguity of this lineage would lead to the evolutionary split between the "grazers" such as the molepedes and the biblarodons, and the predators such as the blindmutts, with the grummlers themselves representing a more ancestral state of this divergence. Indeed, leaning more on the "grazer" side, the giant grummler itself sometimes falls prey to smaller grummler species with more carnivorous tendencies, especially targeted if sick, young or old.

As larger-scale predation began to emerge among the macro-daggoths, a trend akin to surface animals started to arise among them--an arms race between increasingly armed predators and increasingly defended "herbivores", with hunters specializing to take down prey larger than themselves, and large prey developing weapons to better fend off would-be assailants.

One of the most notable examples of this would be the molepedes: a clade of macro-daggoths that developed elongated bodies and short limbs that allowed them to graze closer to the ground, feeding on filamentous, low-growing mocklichens that, in a loose sense, could be considered an analogue of "grass". These slow-moving creatures were afforded ample protection by their size alone in the earlier days, but as predators too began to grow, the molepedes gradually found themselves becoming outmatched. Over time, the ancestral soft-bodied molepedes disappeared entirely, too vulnerable to the new predators, but from it emerged two lineages: the thorny molepedes and the armored molepedes.

The common thorny molepede (Echinopolypodomys spinosus) repurposed many of the sensory bristle hairs of its body into defensive spines, covering its back, its flanks and even its nasal tendrils. These spines, barbed and loose like porcupine quills, embed painfully into a would-be predator's skin and remain stuck in the flesh as they break off. As a warning, they exude a distinctive scent from specialized anal glands that previously-quilled predators quickly associate with a painful experience.

However, while an effective means of self defense, the thorny molepede's defensive spines pose a significant challenge to its other routine activities: specifically, when it comes to mating. Thorny molepede courtship is an awkward affair, with both partners releasing odorous pheromones to communicate their amorous and non-hostile intentions. Once they reach a mutual agreement, they then very slowly and gingerly back into each other, until their rearmost quills barely touch, and the male, fortunately endowed with elongated reproductive equipment, is able to complete his job from a safe distance.

A less socially-challenged relative of the thorny molepede is the armored molepede (Armopolypodomys edurus), which is a far more gregarious creature than its spiny cousin and gathers in small groups of up to ten to twenty individuals at a time. Rather than spines, the armored molepede instead has fused its hypertrophied, hardened bristles into tough keratinous scutes, which form a coat of plated armor nigh-impenetrable to the claws and teeth of its enemies. When threatened, groups of then huddle together and press themselves down, concealing their vulnerable limbs and nasal tendrils and exposing only their armored backs. Their strategy is one of persistence: eventually, after hours of clawing and biting to no avail, most predators simply give up the hunt and leave to find easier food elsewhere, and once danger has passed, the armored molepedes once more unfurl and carry on their usual grazing.

Both types of molepede tend their young with a significant amount of care until their defenses grow in, even if only passively, with their numerous litters of up to twenty young at once huddling between the adults' legs, afforded protection by their armored or spiny backs. They are, however, quite precocial, grazing and moving on their own shortly after birth, and, once sufficiently developed and defended at the age of five or six months, gradually disperse from their parent to lead an independent life.

Such defenses have become a necessity for the great grazer daggoths, as predation became more of a significant threat with the evolution of the cavern system's first proper apex predators, the blindmutts. Earlier forms simply preyed upon smaller daggoths such gothtles and xenomures, but, as prey species increased in size, so did some predators, leading to the development of some advanced blindmutts able to tackle large prey such as molepedes, biblarodons and grummlers as well.

The mandibled tendriltooth (Abyssatrox xenoailuroides) is, in the Middle Temperocene, the caverns' undisputed apex predator: even if it grows only to the size of a large house cat. Its most notable adaptation is the development of sharp, hooked keratinous spines on six of its seven nasal tendrils, which have become thick and muscular and adapted for gripping: in essence becoming six additional jaws with false "teeth". Two of its foremost digits, its central nasal tendril, and its two rear digits act as sensory feelers able to navigate its surroundings with a delicate sense of touch, while it homes in on prey with a powerful sense of smell and hearing. Once it locates its prey, it tries to grapple it with an ambushing pounce before using its six main limbs to anchor itself with its claws, and using its toothed tendril-jaws to secure a firm grip on the prey's neck before using its true teeth, sharp dagger-like incisors, to inflict a fatal bite to the prey's neck. As it targets prey larger than itself, the tendriltooth may take several days to eat its fill, and will camp out next to the carcass over the following days, fending off rivals and scavengers that may come to steal its prize. As its prolonged feeding lasts for a duration long enough for putrefaction to set in, the tendriltooth has evolved an extremely powerful set of digestive juices that allow it to continue feeding on even decomposing meat. Eventually, however, once it has sated its fill, the rotting carcass is then abandoned, and now unguarded, a buffet of scavengers then descend on the carcass, ranging from insects and worms to maggoths and xenomures to even rumptusks, vulpemousers and grummlers, all clearing up the residues the tendriltooth leaves in its wake.

Tendriltooths may reign as top carnivore, devoid of any predators of their own, yet their existence is still a precarious one, as they are few and far between given their placement on the food web. Throughout the entire cavern ecosystem, filled with millions of daggoths of different species, there are never more than a few hundred adult tendriltooths at any one time, being solitary and territorial, as they need plenty of space to sustain themselves. Tendriltooths are fairly prolific, with litters of up to twenty to thrirty tiny offspring at a time, but these small but precocial offspring, independent after only a few weeks, have a rather high mortality rate: during their early youth, where they prey primarily on insects, they are indiscriminately themselves prey for various medium-sized carnivores such as vulpemousers and smaller blindmutts, and, once they themselves graduate to medium-sized carnivore status hunting larger prey like xenomures, now have to contend with adult tendriltooths who will target the subadults to get rid of potential competition. However, should a lucky tendriltooth survive its precarious first two years, a feat accomplished by less than five percent of all juveniles, it is assured a niche of apex predator, unbothered by any other creature and with only another adult tendriltooth to fear.

------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#spec evo#speculative zoology#hamster's paradise#biome post

105 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hahhahahaah penis hahahahahaha

The kraken (/ˈkrɑːkən/) is a legendary sea monster of enormous size, per its etymology something akin to a cephalopod, said to appear in the sea between Norway and Iceland. It is believed that the legend of the Kraken may have originated from sightings of giant squid, which may grow to 12–15 m (40–50 feet) in length.

The kraken, as a subject of sailors' superstitions and mythos, was first described in the modern era in a travelogue by Francesco Negri in 1700. This description was followed in 1734 by an account from Dano-Norwegian missionary and explorer Hans Egede, who described the kraken in detail and equated it with the hafgufa of medieval lore. However, the first description of the creature is usually credited to the Danish bishop Pontoppidan (1753). Pontoppidan was the first to describe the kraken as an octopus (polypus) of tremendous size,[b] and wrote that it had a reputation for pulling down ships. The French malacologist Denys-Montfort, of the 19th century, is also known for his pioneering inquiries into the existence of gigantic octopuses (Octupi).

The great man-killing octopus entered French fiction when novelist Victor Hugo (1866) introduced the pieuvre octopus of Guernsey lore, which he identified with the kraken of legend. This led to Jules Verne's depiction of the kraken, although Verne did not distinguish between squid and octopus.

Linnaeus may have indirectly written about the kraken. Linnaeus wrote about the Microcosmus genus (an animal with various other organisms or growths attached to it, comprising a colony). Subsequent authors have referred to Linnaeus's writing, and the writings of Bartholin's cetus called hafgufa, and Paullini's monstrum marinum as "krakens".That said, the claim that Linnaeus used the word "kraken" in the margin of a later edition of Systema Naturae has not been confirmed.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you like octopuses

Like most of my time, I am at unease at the thought of creatures of the deep. Of these though the polypus is one with which I am more familiar, though vehemently absconded. I’m not even certain they fuck or breed.

Pierre Denys de Montfort likes those damned beasts though.

0 notes

Text

It is easier to destroy than to build

◊ and a collision

◊ to another room

◊ while the king

◊ to the superintendence

◊ to these notched

◊ to the permanence

◊ and the principal

◊ and the tallying

◊ and the incorrupt

◊ to the music

◊ before the Friday

◊ but the storm

◊ While the notches

◊ or a polypus

◊ and that worse

◊ and the son

◊ However this may

◊ and a day

◊ but the base

◊ to the walks

◊ but several parts

◊ and the cause

◊ to the monarch

◊ and a skeleton

◊ to the winds

◊ but an Irish

◊ Although an epicure

◊ to the company

◊ whether a change

◊ but a groat

◊ to the Treasurer

◊ to the greatest

◊ to the conveniences

◊ and a wine

◊ to the king

◊ to the reader

◊ to the author's

◊ and the bishop

◊ to the multitude

◊ but the supporters

◊ but the mystery

◊ to the Catholic

◊ to the town

0 notes

Text

I would wager a few Louis, franc, or livre (or whichever currency France should adopt) one could print and distribute an excessively erotic illuminate novella about such tender and personal intercourses with a polypus.

Hmmm I know octopuses are generally sweet and gentle and are just curious sea puppies (and I love them!), that being said, the thoughts of being dragged by my feet by one of them into the deep and dark ocean is… safe to say new fear has been unlocked

Source

49K notes

·

View notes

Text

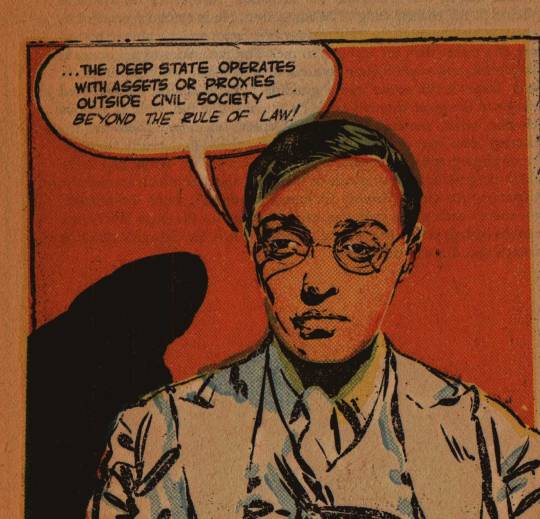

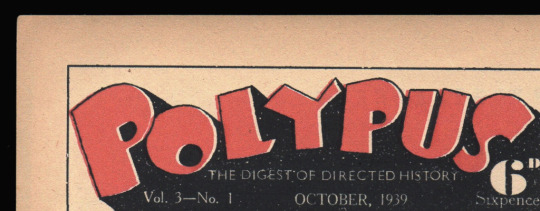

Peter Lorre Comic (Mr. Moto)

This scan comes from this post, which holds no other explanation. The blog itself seems to draw its material from a real (?) British periodical...or something...named Polypus.

I'd love to see if the Mr. Moto panel above comes from a full comic, or at least a full storyline.

I found a British newspaper search site (the full periodicals sites all seem to need credentials), but after sifting through a fair few references of "Adenoids and Polypus," I have a new band name but no other information.

=======================

Adenoids & Polypus

Barely a year after Adenoids & Polypus had a sleeper hit with their first album, NAP APNEA, everyone's favorite Korean-Irish folk-fusion septet has released an EP with three new interpretations of their hit single, "Pre-Malignant Glottis." =========================

#peter lorre#Mr. Moto#comic#Polypus#1930s comics#peter lorre artwork#peter lorre comic#and then a total spin off into a#fake band#Adenoids & Polypus

12 notes

·

View notes

Link

Hi ! Little pleasure to draw this group of 5 together in their new armor.

2 notes

·

View notes