#political caricature 2019

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

TW: ANTISEMITIC IMAGERY

In 2019, the New York Times published an antisemitic cartoon by a Portuguese cartoonist named Antonio Moreira Antunes. The Times quickly retracted the image after it sparked outrage.

Antunes was "confused" as to why people thought he was antisemitic. He defended himself this way:

Sound familiar?

Jewish cartoonist Ya'akov Kirschen responded:

Which is an excellent point. There is nothing "Israeli" about Antunes' cartoon. There's a Jewish man portrayed as a dog with a Magen David, leading a bumbling man in a kippah (meant to be Trump). It evokes old antisemitic propaganda of (((the Jews))) controlling the world's (read: American) leaders.

And the problem with Antunes' defense? He has a history of antisemitism.

Really, Antonio? Holocaust inversion? And I thought you were only interested in "innocent critiques of Israeli policy"? Antunes appears to be interested in maligning the Jews. Why else depict such a horrendous image?

Gentiles know how disgusting and painful Holocaust inversion is, to say that Jews are the "real Nazis". They know how much it hurts us. They want us to feel pain. They have been told of the Holocaust their whole lives. Can they really feign ignorance of it now? Their only ignorance is of good manners.

Ya'akov Kirschen knows a thing or two about antisemitic imagery, by the way. He has a whole website where he has collected antisemitic propaganda, and he has much written work about how vile and intrusive antisemitic imagery is.

Uri Fink, another Jewish cartoonist, says something excellent in the Jersualem Post article:

Any individual, especially artists, must have awareness. You live on a planet with over 7 billion people. You can't just be blissfully unaware of anyone but yourself. In Judaism, we speak often of responsibility. Of what you should do. And what you should do is be a mentsh, don't be a putz. Be aware of context and meaning, and don't say or draw heinous images that you are fully aware will hurt a specific group of people.

But then maybe you don't care.

Maybe you want to hurt them.

And that... is what I cannot understand.

90 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! SUPER interesting excerpt on ants and empire; adding it to my reading list. have you ever read "mosquito empires," by john mcneill?

Yea, I've read it. (Mosquito Empires: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, 1620-1914, basically about influence of environment and specifically insect-borne disease on colonial/imperial projects. Kinda brings to mind Centering Animals in Latin American History [Few and Tortorici, 2013] and the exploration of the centrality of ecology/plants to colonialism in Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World [Schiebinger, 2007].)

If you're interested: So, in the article we're discussing, Rohan Deb Roy shows how Victorian/Edwardian British scientists, naturalists, academics, administrators, etc., used language/rhetoric to reinforce colonialism while characterizing insects, especially termites in India and elsewhere in the tropics, as "Goths"; "arch scourge of humanity"; "blight of learning"; "destroying hordes"; and "the foe of civilization". [Rohan Deb Roy. “White ants, empire, and entomo-politics in South Asia.” The Historical Journal. October 2019.] He explores how academic and pop-sci literature in the US and Britain participated in racist dehumanization of non-European people by characterizing them as "uncivilized", as insects/animals. (This sort of stuff is summarized by Neel Ahuja, describing interplay of race, gender, class, imperialism, disease/health, anthropomorphism. See Ahuja's “Postcolonial Critique in a Multispecies World.”)

In a different 2018 article on "decolonizing science," Deb Roy also moves closer to the issue of mosquitoes, disease, hygiene, etc. explored in Mosquito Empires. Deb Roy writes: 'Sir Ronald Ross had just returned from an expedition to Sierra Leone. The British doctor had been leading efforts to tackle the malaria that so often killed English colonists in the country, and in December 1899 he gave a lecture to the Liverpool Chamber of Commerce [...]. [H]e argued that "in the coming century, the success of imperialism will depend largely upon success with the microscope."''

Deb Roy also writes elsewhere about "nonhuman empire" and how Empire/colonialism brutalizes, conscripts, employs, narrates other-than-human creatures. See his book Malarial Subjects: Empire, Medicine and Nonhumans in British India, 1820-1909 (published 2017).

---

Like Rohan Deb Roy, Jonathan Saha is another scholar with a similar focus (relationship of other-than-human creatures with British Empire's projects in Asia). Among his articles: "Accumulations and Cascades: Burmese Elephants and the Ecological Impact of British Imperialism." Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 2022. /// “Colonizing elephants: animal agency, undead capital and imperial science in British Burma.” BJHS Themes. British Society for the History of Science. 2017. /// "Among the Beasts of Burma: Animals and the Politics of Colonial Sensibilities, c. 1840-1940." Journal of Social History. 2015. /// And his book Colonizing Animals: Interspecies Empire in Myanmar (published 2021).

---

Related spirit/focus. If you liked the termite/India excerpt, you might enjoy checking out this similar exploration of political/imperial imagery of bugs a bit later in the twentieth century: Fahim Amir. “Cloudy Swords” e-flux Journal Issue #115. February 2021.

Amir explores not only insect imagery, specifically caricatures of termites in discourse about civilization (like the Deb Roy article about termites in India), but Amir also explores the mosquito/disease aspect invoked by your message (Mosquito Empires) by discussing racially segregated city planning and anti-mosquito architecture in British West Africa and Belgian Congo, as well as anti-mosquito campaigns of fascist Italy and the ascendant US empire. German cities began experiencing a non-native termite infestation problem shortly after German forces participated in violent suppression of resistance in colonial Africa. Meanwhile, during anti-mosquito campaigns in the Panama Canal zone, US authorities imposed forced medical testing of women suspected of carrying disease. Article features interesting statements like: 'The history of the struggle against the [...] mosquito reads like the history of capitalism in the twentieth century: after imperial, colonial, and nationalistic periods of combatting mosquitoes, we are now in the NGO phase, characterized by shrinking [...] health care budgets, privatization [...].' I've shared/posted excerpts before, which I introduce with my added summary of some of the insect-related imagery: “Thousands of tiny Bakunins”. Insects "colonize the colonizers". The German Empire fights bugs. Fascist ants, communist termites, and the “collectivism of shit-eating”. Insects speak, scream, and “go on rampage”.

---

In that Deb Roy article, there is a section where we see that some Victorian writers pontificated on how "ants have colonies and they're quite hard workers, just like us!" or "bugs have their own imperium/domain, like us!" So that bugs can be both reviled and also admired. On a similar note, in the popular imagination, about anthropomorphism of Victorian bugs, and the "celebrated" "industriousness" and "cleverness" of spiders, there is: Claire Charlotte McKechnie. “Spiders, Horror, and Animal Others in Late Victorian Empire Fiction.” Journal of Victorian Culture. December 2012. She also addresses how Victorian literature uses natural science and science fiction to process anxiety about imperialism. This British/Victorian excitement at encountering "exotic" creatures of Empire, and popular discourse which engaged in anthropormorphism, is explored by Eileen Crist's Images of Animals: Anthropomorphism and Animal Mind and O'Connor's The Earth on Show: Fossils and the Poetics of Popular Science, 1802-1856.

Related anthologies include a look at other-than-humans in literature and popular discourse: Gothic Animals: Uncanny Otherness and the Animal With-Out (Heholt and Edmunson, 2020). There are a few studies/scholars which look specifically at "monstrous plants" in the Victorian imagination. Anxiety about gender and imperialism produced caricatures of woman as exotic anthropomorphic plants, as in: “Murderous plants: Victorian Gothic, Darwin and modern insights into vegetable carnivory" (Chase et al., Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 2009). Special mention for the work of Anna Boswell, which explores the British anxiety about imperialism reflected in their relationships with and perceptions of "strange" creatures and "alien" ecosystems, especially in Aotearoa. (Check out her “Anamorphic Ecology, or the Return of the Possum.” Transformations. 2018.)

And then bridging the Victorian anthropomorphism of bugs with twentieth-century hygiene campaigns, exploring "domestic sanitation" there is: David Hollingshead. “Women, insects, modernity: American domestic ecologies in the late nineteenth century.” Feminist Modernist Studies. August 2020. (About the cultural/social pressure to protect "the home" from bugs, disease, and "invasion".)

---

In fields like geography, history of science, etc., much has been said/written about how botany was the key imperial science/field, and there is the classic quintessential tale of the British pursuit of cinchona from Latin America, to treat mosquito-borne disease among its colonial administrators in Africa, India, and Southeast Asia. In other words: Colonialism, insects, plants in the West Indies shaped and influenced Empire and ecosystems in the East Indies, and vice versa. One overview of this issue from Early Modern era through the Edwardian era, focused on Britain and cinchona: Zaheer Baber. "The Plants of Empire: Botanic Gardens, Colonial Power and Botanical Knowledge." May 2016. Elizabeth DeLoughrey and other scholars of the Caribbean, "the postcolonial," revolutionary Black Atlantic, etc. have written about how plantation slavery in the Caribbean provided a sort of bounded laboratory space. (See Britt Rusert's "Plantation Ecologies: The Experiential Plantation [...].") The argument is that plantations were already of course a sort of botanical laboratory for naturalizing and cultivating valuable commodity plants, but they were also laboratories to observe disease spread and to practice containment/surveillance of slaves and laborers. See also Chakrabarti's Bacteriology in British India: laboratory medicine and the tropics (2012). Sharae Deckard looks at natural history in imperial/colonial imagination and discourse (especially involving the Caribbean, plantations, the sea, and the tropics) looking at "the ecogothic/eco-Gothic", Edenic "nature", monstrous creatures, exoticism, etc. Kinda like Grove's discussion of "tropical Edens" in the colonial imagination of Green Imperialism.

Dante Furioso's article "Sanitary Imperialism" (from e-flux's Sick Architecture series) provides a summary of US entomology and anti-mosquito campaigns in the Caribbean, and how "US imperial concepts about the tropics" and racist pathologization helped influence anti-mosquito campaigns that imposed racial segregation in the midst of hard labor, gendered violence, and surveillance in the Panama Canal zone. A similar look at manipulation of mosquito-borne disease in building empire: Gregg Mitman. “Forgotten Paths of Empire: Ecology, Disease, and Commerce in the Making of Liberia’s Plantation Economy.” Environmental History. 2017. (Basically, some prominent medical schools/departments evolved directly out of US military occupation and industrial plantations of fruit/rubber/sugar corporations; faculty were employed sometimes simultaneously by fruit companies, the military, and academic institutions.) This issue is also addressed by Pratik Chakrabarti in Medicine and Empire, 1600-1960 (2014).

---

Meanwhile, there are some other studies that use non-human creatures (like a mosquito) to frame imperialism. Some other stuff that comes to mind about multispecies relationships to empire:

Lawrence H. Kessler. “Entomology and Empire: Settler Colonial Science and the Campaign for Hawaiian Annexation.” Arcadia (Spring 2017)

No Wood, No Kingdom: Political Ecology in the English Atlantic (Keith Pluymers)

Archie Davies. "The racial division of nature: Making land in Recife". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers Volume 46, Issue 2, pp. 270-283. November 2020.

Yellow Fever, Race, and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century New Orleans (Urmi Engineer Willoughby, 2017)

Pasteur’s Empire: Bacteriology and Politics in France, Its Colonies, and the World (Aro Velmet, 2022)

Tom Brooking and Eric Pawson. “Silences of Grass: Retrieving the Role of Pasture Plants in the Development of New Zealand and the British Empire.” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. August 2007.

Under Osman's Tree: The Ottoman Empire, Egypt, and Environmental History (Alan Mikhail)

The Herds Shot Round the World: Native Breeds and the British Empire, 1800-1900 (Rebecca J.H. Woods, 2017)

Imperial Bodies in London: Empire, Mobility, and the Making of British Medicine, 1880-1914 (Kristen Hussey, 2021)

Red Coats and Wild Birds: How Military Ornithologists and Migrant Birds Shaped Empire (Kirsten Greer, 2020)

Animality and Colonial Subjecthood in Africa: The Human and Nonhuman Creatures of Nigeria (Saheed Aderinto, 2022)

Imperial Creatures: Humans and Other Animals in Colonial Singapore, 1819-1942 (Timothy P. Barnard, 2019)

Biotic Borders: Transpacific Plant and Insect Migration and the Rise of Anti-Asian Racism in America, 1890-1950 (Jeannie N. Shinozuka)

#ecology#bugs#multispecies#landscape#indigenous#haunted#temporal#colonial#imperial#british entomology in india#mosquitoes#carceral#tidalectics#intimacies of four continents#carceral geography#pathologization

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Activism : The Play, Scene II

Activism has always been around for such a long, long time. However, not a lot of people are aware of how people back in the days used to use their voices or influence in the acts of activism. Which brings up to the question I have in mind, "What was activism like in the days of Ancient Greece?" "Now I know they have protests too, but did they incorporated it into their entertainment? Entertainment has always been a tool to advocate for changes. Right?"

I've always been a huge fan of ancient Greek history, mainly mythology but sometimes, I do dabble into their philosophical and political sides. To answer my own question, I've decided to do a slight dive on Aristophanes.

First thing's first, what is activism? Nolas, S.M., Varvantakis, C. and Aruldoss, V., 2017 defines activism as an act that could be driven by the intentions to challenge social norms, practices that holds back and oppresses, suppresses identities that does not conform to the values of a society. Now activism can happen anywhere and any time, from a playground where both genders can play together without being judged for being a girl or a boy, a dinner table where discussions from studies, work, world issues can happen. Nolas, Varvantakis and Aruldoss, 2017 have also stated in their papers activism can also be a response to changes and events within the society, such as the rise of new social movements and the need to do a dive in onto political participation in the face of unexpected political outcomes. So how does this relate to Aristophanes?

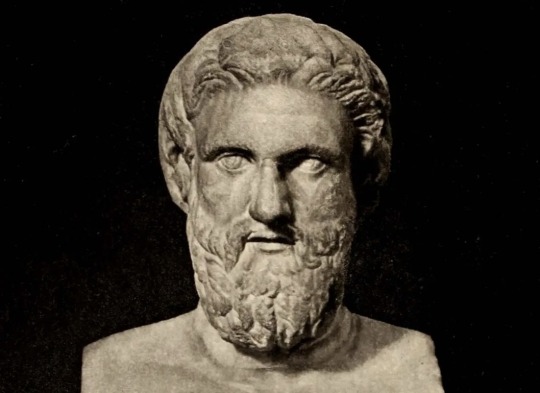

Now according to an article published by Columbia College, Aristophanes was an ancient Greek playwright and comedian who lived in Athens, he was born somewhere around 446 BCE and died around 386 BCE. He was best known for his comedic plays, wrote roughly around 40 plays, where only 11 of his works survived to this very day. The reason why I found that his work is related to activism, particularly political activism is because his plays were known for its satirical and political nature. He incorporated humour, an exaggeration towards contemporary issues, philosophy and social trends into his work, making him known as one of the first people to be a public relations activist. Using political satire was one of the Ancient Greek's way to perform activism and public relations. (Bisbe, M., Molner, E. and Jimenez, M., 2019).

An example that can be taken from Aristophanes' play called "Lysistrata" written in 411 BCE that depicts the Peloponnesian war between the Athens and the Spartans. As known with his knack for satire and comedy, he wrote this as a portrayal of a fictional attempt by women from Ancient Greek to end the war by withholding sexual privileges with their husbands in order to stop the war until a treaty was signed. Albeit the play talking about a woman's needs with her spouses, the dialogue. talked about how men who focused on the war has been nothing but wasteful of the tax payer's money that women and the society contributed to, going back to Aristophanes' way of addressing the the financial effects of war, showing the frivolous nature of war and also the effects of wat on families.

Another example would be one of his well known plays "The Clouds". The Clouds was written as a political and philosophical satire on Socrates and his institution, which is also known as "The Clouds" Aristophanes used humour and exaggerated language to caricature Socrates' methods of inquiry and the perceived consequences of philosophical education. For example, here is a small dialogue from the play I read.

SOCRATES

Well now! what are you doing? are you reflecting?

STREPSIADES

Yes, by Posidon!

SOCRATES

What about?

STREPSIADES

Whether the bugs will entirely devour me.

SOCRATES

May death seize you, accursed man!

He turns aside again.

The play suggests that the pursuit of abstract knowledge and intellectualism can lead to moral and societal corruption, as The Cloud is about a man named Strepsiades who enrolled himself to Socrates' institution in order to avoid getting caught for his financial debts instead of trying his best to work things out and ethically clear out his debts. And in my opinion, activism doesn't always have to be something we do as a form of protest (physically done with marching), or an online post, or a drawing or photos but it could also be done in a form of writing. A script, a play, a book or a poem.

Refences

Nolas, S.M., Varvantakis, C. and Aruldoss, V., 2017. Political activism across the life course. Contemporary Social Science, 12(1-2), pp.1-12, viewed 22 November 2023.

Bisbe, M., Molner, E. and Jimenez, M., 2019. Public intellectuals, political satire and the birth of activist public relations: The case of Attic Comedy. Public Relations Review, 45(5), p.101790, viewed 23 November 2023

Foley, H.P., 1982. The" female intruder" reconsidered: Women in Aristophanes' Lysistrata and Ecclesiazusae. Classical Philology, 77(1), pp.1-21, viewed 19 November 2023

The Internet Classics Archive: The Clouds by aristophanes’, The Internet Classics Archive | The Clouds by Aristophanes, viewed 24 November, 2023, <http://classics.mit.edu/Aristophanes/clouds.html>

#mda20009#social media#blogging#digital communities#week6#activism#aristophanes#ancient history#ancient greece#ancient greek literature#ancient greek culture#ancient greek

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

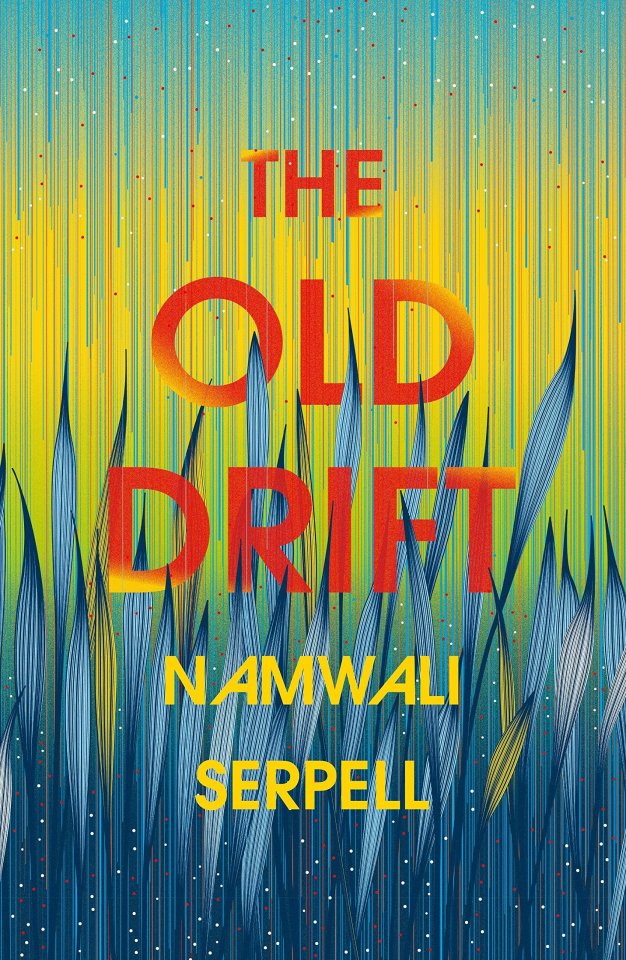

‘The Old Drift’ Is a Dazzling Debut Spanning Four Generations

By Dwight Garner

March 25, 2019

Namwali Serpell’s audacious first novel, “The Old Drift,” is narrated in small part by a swarm of mosquitoes — “thin troubadours, the bare ruinous choir” — who declare themselves “man’s greatest nemesis.”

They’re a pipsqueak chorus, a thrumming collective intelligence, a comic and subversive hive mind. They are here to puncture, if you will, humanity’s pretensions.

“The Old Drift” is an intimate, brainy, gleaming epic, set mostly in what is now Zambia, the landlocked country in southern Africa. It closely tracks the fortunes of three families (black, white, brown) across four generations.

The plot pivots gracefully — this is a supremely confident literary performance — from accounts of the region’s early white colonizers and despoilers through the worst years of the AIDS crisis. It pushes into the near future, proposing a world in which flocking bug-size microdrones are a) fantastically cool and b) put to chilling totalitarian purposes.

Serpell’s mosquitoes observe the dozens of wriggling humans in this novel, and they are distinctly unimpressed. We were here before you, they imply. We will be here long after you are gone. In the meantime, thanks for the drinks.

The reader who picks up “The Old Drift” is likely to be more than simply impressed. This is a dazzling book, as ambitious as any first novel published this decade. It made the skin on the back of my neck prickle.

Serpell seems to want to stuff the entire world into her novel — biology, race, subjugation, revolutionary politics, technology — but it retains a human scale. It is filled with love stories, greedy sex (“my heart twerks for you,” one character comments), pot smoke, comedy, inopportune menstruation, car crashes, tennis, and the scorching pleasure and pain of long hours in hair salons.

Serpell is a Zambian writer; she was born in that country and moved to the United States with her family when she was nine. She teaches literature at the University of California, Berkeley.

There’s a vein of magical realism in her work — one woman cries almost literal rivers, another has hair that covers nearly her entire body and that grows several feet a day — that will spark warranted comparisons to novels such as Salman Rushdie’s “Midnight’s Children” and Gabriel García Márquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude.”

Serpell does not try to charm her readers to death. Her men and women are not cute (except, sometimes, to each other), and they are not caricatures. Even the most virulent racists in “The Old Drift” aren’t one-dimensional.

Serpell is a pitiless and often very funny observer of people and of society. She describes polo as “that strange game that seems like a drunken bet about golf and horse riding.” A man on a leather sofa is commended for “expertly unlocking that complex apparatus — a clothed woman.”

She offers this definition of “history”: “the word the English used for the record of every time a white man encountered something he had never seen and promptly claimed it as his own, often renaming it for good measure.”

Here she is on a young white woman in Zambia: “She seemed both weak and imperious, helpless yet haughty. In a word: British.”

This is a matrilineal epic. It is packed with grandmothers, mothers, daughters. They are hardly placed on pedestals or lit by false, ennobling, autumnal light. They’re all struggling. Some drop out of school, steal or dabble with skin-whitening creams. Some open businesses, others turn to prostitution. Still others turn to protest. Nearly all are hoping to find love and, in the interim, to avoid being raped.

This book is intensely concerned with women’s bodies. Dissertations will surely be written about the multiple meanings of hair in this novel. We’ve learned too much from male writers about what it’s like to walk the planet guided and plagued by one’s reproductive apparatus. This novel, with wit and sensitivity, flips and revises that familiar script.

One young woman gets her period on her wedding day. Her friends, her family, the many guests — they’re all here. “All she wanted,” Serpell writes, “was to be at home in bed, curled in a ball, alone and quietly bleeding.”

Serpell is keenly interested in olfactory information. She lingers on people and places and scent. In one scene, a blind woman smells eucalyptus and knows she is nearly home. In another, a mother dislikes her daughter’s “new teenagery smell,” described as “a melony-lemony-biscuity scent that Adriana found both puerile and daunting.”

The plot of “The Old Drift” is not simple to unpack. The book begins, at the start of the 20th century, at a colonial settlement on the banks of the Zambezi River called the Old Drift. A dam is being constructed that will change many lives, a dam that some will wish to bring down.

The first women we meet, beginning around 1940, are: Sibilla, a white girl so unusually hirsute that at one point later in life she will be referred to as “an NGO for hair”; Agnes, a “pale, mad” and blind British girl who marries a black professor and engineer; and Matha, a bright girl whose prospects collapse after she becomes pregnant. She is this novel’s copious weeper, “the heartbreak queen of Kalingalinga.”

We get to know their daughters. One operates “Hi-Fly Haircuttery & Designs Ltd” (and perhaps a shadier business); another is a stewardess who once had artistic ambitions. One of these daughters has a long affair with a doctor who is working on a vaccine for H.I.V.

About a potential vaccine, we get shrewd snippets of dialogue like this one: “‘Beta version,’ Naila scoffed. ‘They should just say black version. They’re testing it on us.’”

The third generation goes on to work on microdrones, on further AIDS research and on political protest, seeking redress for the wrongs of history. One character also works on the vexing future of wearable technology — digital beadlike chips, implanted into the skin, that with the help of permanent tattoos of conductive ink turn one’s hands into approximations of smartphones.

“Government is controlling us,” one character says near the end of the novel. “And the worst part is — we chose this. We held our hands out to them and said PLEASE BEAD US!”

Serpell carefully husbands her resources. She unspools her intricate and overlapping stories calmly. Small narrative hunches pay off big later, like cherries coming up on a slot machine.

Yet she’s such a generous writer. The people and the ideas in “The Old Drift,” like dervishes, are set whirling. When that whirling stops, you can hear the mosquitoes again. They’re still out there.

They sound like tiny drones. They sound like dread.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

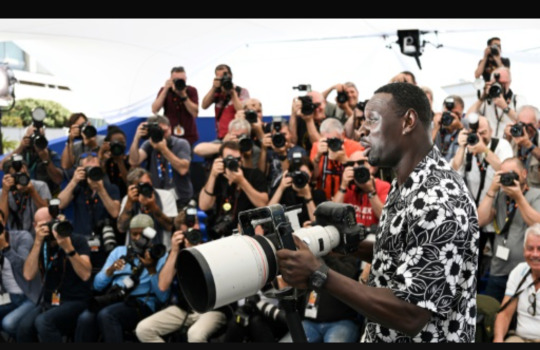

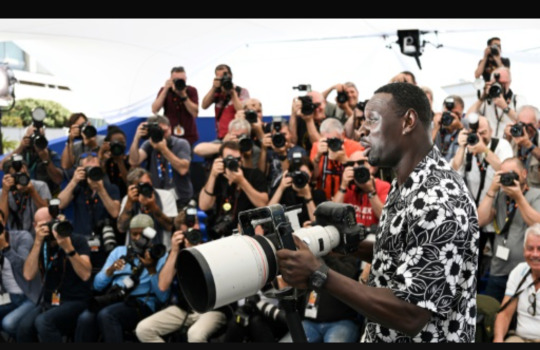

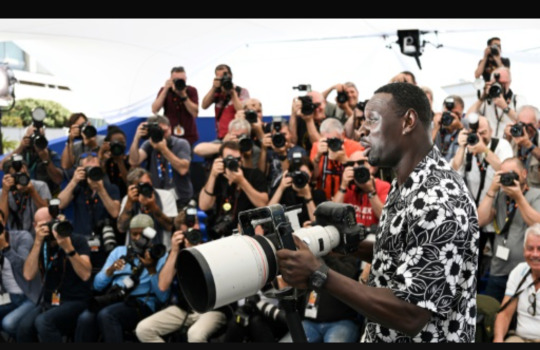

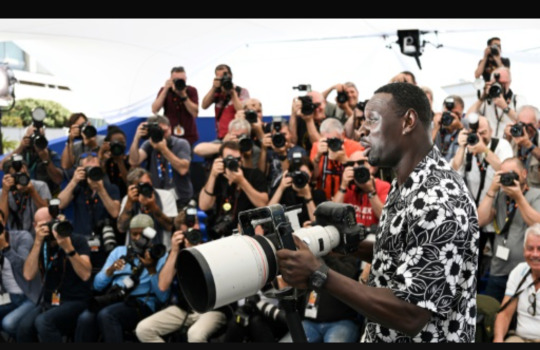

How French film is quietly becoming more diverse

PARIS

"Vermin", a horror film about killer spiders invading a run-down apartment block, has become the first hit of the year in France.

The eight-legged critters are not the only surprise in the low-budget film, however, which for once depicts France's ghetto-like suburbs as more than just a den of drug dealers and terrorists.

Instead the block is shown as a place of hard-scrabble solidarity whose problems stem from abandonment by police, media and society in general.

"We want to challenge stereotypes," said Olivier Saby of co-producers Impact Films. The company was set up in 2018 with a mission to bring more diversity to French cinemas.

"The goal is not to make sure there is a black, Arabic or white person in every scene," he told AFP. "We just want films and TV to reflect real life. If you walk into, for example, a lawyer's office today, you will find a lot more diversity than when you see one on TV."

French cinema has made steady progress in some areas.

French women won two of the last three Palmes d'Or, the top prize at the Cannes Film Festival. Three of the five nominees for best director at next month's Cesars (France's Oscars) are women. (The prize has only once gone to a woman, Tonie Marshall, 24 years ago.)

Race is trickier.

Some black actors have become superstars in France, especially "Lupin" star Omar Sy, and comedian Jean-Pascal Zadi, whose sharp satires about racial politics, "Simply Black" and "Represent", have earned awards and been big international hits on Netflix.

But progress is hindered because it remains illegal to gather data on race in France on the grounds that it would perpetuate artificial divisions, said Wale Gbadamosi Oyekanmi, a PR consultant who invests in Impact Film.

"France doesn't really talk about race. You can't monitor the depth of the challenge because you can't measure it" with statistics, he told AFP. "There are new voices that could be heard, that reflect the country as it is now. It's something that can and must be improved."

Analysts work around the issue by measuring how people are "perceived" rather than directly asking their race.

A study of 115 French films released in 2019 by 50/50 Collectif, a campaign group, found 81 percent of lead characters were "perceived as white".

That is not a commercial decision, it said, since the figure dropped to 68 percent for the 15 most popular films of the year.

But France's cultural gatekeepers still bristle at the idea of mixing social issues with creativity, said Marie-Lou Dulac, founder of diversity consultancy DIRE et Dire.

Many in France see encouraging diversity as a way of "perverting creativity," she said. "Actually it's a way to renew creativity, to encounter new stories and characters.

"We can't keep making the same old caricature of a French film -- a white professional couple in Paris who are cheating on each other," she added with a laugh.

Impact Films supports films with LGBTQ, disabled or ethnic minority leads, said Saby. It finances documentaries about environmental and social issues, and hires people from under-represented groups to work behind the camera.

It also works with scriptwriters to avoid cliches. "Why are minority actors always playing a drug dealer?" he added. "Does every action hero need to drive a 4x4?"

As in other countries, pushing for change triggers a backlash.

Powerful right-wing businessmen are also moving into film productions, such as last year's "Vaincre ou Mourir" ("Victory or Death") about the peasant counter-revolution of the 1790s, a favorite topic of pro-Catholic, pro-monarchy ultra-conservatives.

It was produced by the company behind the Puy du Fou theme park, owned by far-right former presidential candidate Philippe de Villiers.

The risk of a backlash is no reason to give up, said Saby, with "Vermin" up for two Cesar awards and well on its way to being the most successful French horror flick in nearly 25 years.

"There was always this battle. It's just that only one side was winning up to now," he said. "There's plenty of room on screen for everyone."

0 notes

Text

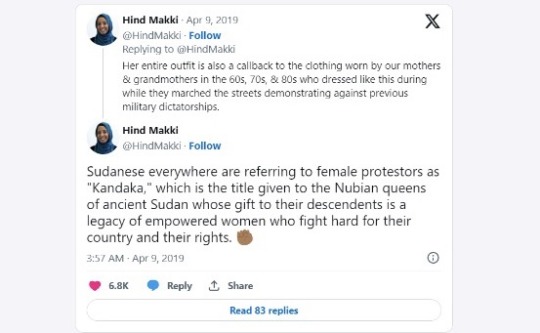

From Streets to Symbols: Unveiling the Power of Graffiti, Art, Music, and Culture in Protest Movements – A Spotlight on the Sudanese Revolution

Have you ever found yourself associating a dance move with a particular era or linking a pose to a significant cultural moment? Such connections often transcend the boundaries of the physical, seeping into the realms of art, music, and cultural symbols. In Sudan, the evolution of symbols during the revolution was nothing short of poetic. The Sudanese revolution of 2019 serves as a compelling canvas where these forms of expression converged, giving rise to the Kandaka with the white toub—a powerful symbol of resistance that echoed the collective voices of a nation yearning for change.

Graffiti and Street Art as Voices on Walls

During Sudan’s 2019 revolution, as people mobilized across the country with sit-ins, marches, boycotts, and strikes, artists helped capture the country’s discontent and solidify protesters’ resolve (How Art Helped Propel Sudan’s Revolution, n.d.). What started as protests against rising food and fuel costs turned into a coup where millions marched to overthrow al-Bashir after 30 years in power.

Artists became an integral part of the months-long sit-in at the military headquarters in Khartoum, known as the heart of the revolution. This expression of creativity was both a result of loosening restrictions on freedom of expression and a catalyst for further change.

Artists throughout Sudan used graffiti to spur conversations about the trajectory of the country and also used murals to share information about dates and times of protests. Jonathan Pinckney, program officer and research lead for USIP’s program on nonviolent action, pointed out that art has played a role in many major nonviolent struggles to create a shared vocabulary (How Art Helped Propel Sudan’s Revolution, n.d.).

Hussein Merghani’s watercolor of hundreds of people from Atbara traveling to join the sit-in at the military headquarters in Khartoum in April 2019.

A mural by Galal Yousif near the sit-in site reads “you were born free, so live free.” (Sari Ahmed Awad)

Visual Arts and Popular Culture: The Kandaka and the White Toub:

In a society where patriarchy and male dominance prevail, it's quite surprising that a woman emerged as a symbol of protest. The kandake, breaking stereotypes, became an iconic figure, showcasing the resilience of Sudanese women who have long been leaders in the country’s revolutions. Since 1989, when Omar al-Bashir seized power, women faced curtailed rights under vaguely defined moral and penal codes, notably the 1991 Public Order Laws dictating women's public conduct, movement, and even clothing. Despite these oppressive measures, women persisted in their fight against al-Bashir's rule, playing a pivotal role in mobilizing protests.

This resilience found a remarkable face in a young student named Alaa Salah, captured in a moment of protest wearing a white toub and traditional jewelry. Standing atop a car, she passionately chanted revolutionary poetry, expressing the collective frustrations: “They imprisoned us in the name of religion, burned us in the name of religion … killed us in the name of religion,” met with the resounding response of “revolution” from the crowd (Ismail and Elamin 2019). This powerful image swiftly went viral in Sudan, becoming a catalyst for countless Sudanese artworks, ranging from political caricatures to paintings to graffiti on Khartoum's streets.

What makes this image truly iconic is the symbolism embedded in the white toub—a garment worn by women of all classes, considered a democratic attire that doesn't conform to strict piety rules promoted by Islamists. Urban upper- and middle-class women, by embracing the toub, transcended ethnic and social differences, actively promoting unity. The resonance of this image extended beyond its visual impact, inspiring a wave of artistic expressions that echoed the collective call for change on the streets of Khartoum.

The Digital Canvas: Social Media as the New Protest Wall

When delving into the role of digital communities and social media in amplifying protests, particularly within Sudan, one cannot overlook the pivotal role online communication played during the revolution. However, these efforts faced substantial hurdles due to government-initiated internet outages and blockages targeting key sites.

Despite these challenges, the #SudanUprising hashtag emerged as a crucial tool, enabling people to stay connected with the diaspora and providing a real-time feed of events. This hashtag echoed resoundingly across various digital platforms, effectively transforming cyberspace into a dynamic virtual protest ground.

As the Kandaka and the white toub began to capture hearts on social media, the digital realm evolved into a powerful conduit for spreading awareness and mobilizing global support. The viral nature of these symbols transcended geographical boundaries, forging a united global community in solidarity with Sudan's impassioned fight for justice. Journalists, activists, and human rights groups closely followed #SudanUprising, receiving updates in English, while international organizations such as the UN and Amnesty unequivocally condemned the attacks on the protesters.

During the persisting blackout, more details about the tragic June 3 attack unfolded, revealing a grim toll – over 100 lives lost, including 26-year-old engineer Mohamed Mattar. In a poignant tribute, Mattar’s family and friends changed their profile pictures to blue, his favorite color. This simple yet powerful act evolved into #BlueForSudan, swiftly transforming into a global movement to honor and stand in solidarity with all the victims.

Renowned figures such as American singer and actress Rihanna and Nigerian artist Davido joined the chorus of celebrities and high-profile artists who utilized their platforms to shed light on the crisis, further propelling the momentum of awareness online. This vividly underscores the profound impact of virality in shaping public opinion and underscores the critical importance of social media in enhancing visibility and fostering global support for protests. The viral image of the Kandaka served as a catalyst, creating a wave that stirred widespread calls to action.

Navigating Change and Resilience Through the Digital Evolution of Expression

Looking back at how graffiti, art, music, and culture unfolded during the Sudanese revolution, it's clear these expressions aren't confined to physical spaces – they evolve and echo on digital stages. The Kandaka in the white toub isn't just an image; it's a powerful symbol, showing how art and culture shape stories and bring people together. In today's world, hashtags become anthems, and digital communities amplify calls for change. The Sudanese revolution teaches us about the enduring strength of creativity in tough times. The Kandaka's journey from streets to screens, from local to global, shows us how art can spark change and resilience in the face of challenges.

References

How art helped propel Sudan’s revolution. (n.d.). United States Institute of Peace. https://www.usip.org/blog/2020/11/how-art-helped-propel-sudans-revolution

Roussi, A., & Lonardi, M. (2021, July 6). Art on the front lines of a changing Sudan. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2021/6/30/art-on-the-front-lines-of-a-changing-sudan

From white Teyab to pink Kandakat: Gender and the 2018-2019 Sudanese Revolution. (n.d.). Journal of Public and International Affairs. https://jpia.princeton.edu/news/white-teyab-pink-kandakat-gender-and-2018-2019-sudanese-revolution

#mda20009#sudaneserevolution#2019sudanuprising#digitalcitiziship:protest#digitalcitizinship:activism

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Back in the dock… an Economist cover from 2019 . . #illo #politics #artistsoninstagram #caricature #portrait #profileillustration #magazineillustration #politicalcartoon #trumpindictment #trumpinthedock #fraud #politicalcartoon https://www.instagram.com/p/Cqp5dcotvWX/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#illo#politics#artistsoninstagram#caricature#portrait#profileillustration#magazineillustration#politicalcartoon#trumpindictment#trumpinthedock#fraud

1 note

·

View note

Text

On Comics: Comics Needs Jacob Lawrence, Not Crumbs of Freedom

by Noah Berlatsky

[ed. note: a prior iteration of this article appeared as “Crumbs of Freedom” on Patreon in 2019]

Canons aren’t just descriptions of the most important artists in a field. They’re a proscriptive vision of what art should be, and how you should interact with it. Brian Doherty at Reason makes that very clear in his extensive 2019 defense of R. Crumb.

The article was responding to an incident in which cartoonists at the Ignatz Award in 2018 booed Crumb (who was not attending) as a racist and a sexist. Doherty is admirably careful to point out that these boos were simply an exercise of free speech, not some sort of censorship of Crumb. But he argues that the exercise of that speech, the liberty of critique, is in fact a gift from Crumb himself. “Crumb’s attempt to open comics to a vast range of human expression was victorious,” Doherty writes. He continues:

Whether they want to acknowledge it or not, those working in the field today are his descendants. Like all children and grandchildren, they can choose whether or not to understand their patriarch, whether to emulate him or tell him to fuck off. Their choices may not always be kind or wise, but such is human freedom.

For Doherty, Crumb defines the parameters of comics possibility for all creators, “Whether they want to acknowledge it or not.” Creators can embrace Crumb, or they can reject Crumb, but it is always Crumb they are embracing or rejecting. He is the problematic father who successors must adore or kill. Creators cannot, in Doherty’s view, pick and choose their influences; they can say they reject Crumb, but their freedom to do so is just more evidence of their debt to him. “Anyone making noncorporate, nongenre, self-expressive comics occupies a space [Crumb] created,” Doherty says. He praises human and artistic freedom, but that freedom has strict limits. And the name of those limits is “Crumb.”

Doherty is correct; Crumb does occupy a unique place in comics. Crumb treated comics, not as genre adventure, but as a way to pour out his neurosis, sexual obsessions, racist fantasies, and political irritations on the page. Anything in your head could go into your comics, Crumb insisted. That’s been inspiring for autobiographical cartoonists like Art Spiegelman and Alison Bechdel. And it’s been a way to lend comics legitimacy, which is why Crumb has been so important to Gary Groth, editor of The Comics Journal, and publisher of Fantagraphics, one of the most important independent comics imprints.

But the question is: is Crumb canonical because his work is important? Or is his work important because it’s canonical? In other words, does self-expression, controversial content, and legitimacy in comics have to pass through Crumb, as a historical inevitability? Or has the critical elevation of Crumb been something of a self-fulfilling prophecy? Is Crumb what people find to open them to possibilities, or is he the possibility people are offered? To put it another way, what options are closed down, and what traditions are excluded, when all comics are said to be in conversation with this one guy?

One artist that gets excluded from a Crumb-dominated discussion of comics is Jacob Lawrence.

Lawrence is a well-known figure in visual art; he’s one of the seminal African-American painters of the twentieth century. His work isn’t generally thought of as comics for various reasons. One innocuous one is that his art generally hangs in galleries, rather than being reproduced in pamphlets. A more disturbing possibility is that comics traditions and iconography has been shaped by traditions of racist blackface caricature, and antiracist work is therefore marginalized within the comics subculture.

But whatever the reason for Lawrence’s exclusion, it’s not that difficult to recuperate him for comics if you’re willing to look at his work with fresh eyes. Lawrence’s wonderful The Legend of John Brown, for example, is a series of twenty-two 20” x 14” images with text—or pages, if you will—originally completed in 1941, but typically displayed as a series of screenprints completed in 1977. While it’s not in a mass-market pamphlet format, the work is presented as a series of prints.

Lawrence’s figures are simplified, distorted, and deliberately flat; he’s working from a mural tradition which parallels, and overlaps with, cartooning. More, The Legend of John Brown is a narrative series, and each image is accompanied by a short text description/explanation. By Scott McCloud’s definition of comics as “Juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer,” The Legend of John Brown is more comics than The Far Side.

More importantly, I think Lawrence and comics have something to offer each other. Each of the images of The Legend of John Brown is striking on its own, but the work gains in complexity and power when it is considered as a whole narrative work. Typical galleries of this work do Lawrence a disservice by not organizing the prints in sequence or by not including Lawrence’s text. Treating the work as discrete images, rather than as a single comic, undersells Lawrence’s artistry.

For example, the first page in the series (above) shows Brown contemplating a giant, crucified Christ, the cross stark against the hill and sky. It’s an image which puts us in the place of Brown, gazing upon a large, awesome, open spectacle of death, obligation, and blood (which flows copiously down Christ’s legs and onto the hillside.)

The second page is an abrupt shift; the text reads, “For 40 years, John Brown reflected on the hopeless and miserable condition of the slaves,” and the image shows him doing that, in a small house, with others praying around him. The cramped space, and the heads all bowing together, are emphasized by Brown’s own interlaced hands, a massed clump, in the center of the image. The insistent inward-turning is relieved by a skewed window at the side, through which a single bare tree reaches up to the sky—an echo of the cross on the first page. Communal resolution, between people, is undertaken in the shadow of God. Immanence takes on weight and power because of transcendence, and vice versa.

This back-and-forth between tight groupings of figures and flashes of space is an organizing theme throughout the comic. Page 6, “John Brown formed an organization among the colored people of the Adirondack woods to resist the capture of any fugitive slaves,” shows Brown in close consultation with a group of three black men, all clustered together around a pair of rifles Brown holds in both large clasped hands, their barrels making a cross. The next page, “To the people he found worthy of trust, he communicated his plans,” shows Brown at another table, a coat tree at his side (again echoing the cross), a window open behind him.

This symbolic emphasis on closing in and opening out are emphatically resolved on the final two pages. Page 21, “After John Brown’s capture, he was put on trial for his life in Charles Town, Virginia (now West Virginia),” shows Brown against a brown background as he slumps over a cross held in his clasped hands. It’s an image of cloistered intimacy; we can’t even see Brown’s face, which is bent and shrouded in his hair. The final page opens up to show Brown hanging by the neck against a deep blue sky. A cloud seems to reach out to him, forming a shadowy fist behind him, an echo of his own clasped hands, as if he’s now in fellowship with God.

If Lawrence gains from being considered as comics, I think comics also gains by including Lawrence in its canon. That’s not (just) because Lawrence is an amazing artist who would solidify comics status as a worthwhile art form. Rather, it’s because Lawrence offers formal and intellectual resources which comics artists could use.

The Legend of John Brown is especially impressive as a narrative, which (literally, one could say) draws the viewer into a political and moral community.

Political engagement in canonical comics, from editorial cartoons to Doonesbury to Crumb, often leverages cartooning’s power to ridicule in order to caricature and mock. Lawrence takes another tack. His comic is also public art, and the narrative insistently faces both inwards and outwards. On page 17, for example, we see Brown, face turned from us addressing a group of black men. The soldiers fill the panel—on both sides men’s arms are cut off by the border. This makes the image look cluttered and crowded; the group of people massing against racism can barely fit in the image. It also beckons to people off panel, like us. They’re listening to Brown, and we’re listening to Brown; we’re standing together.

The message is even more direct on the last page, which calls back to the first. Brown hanging in mid-air echoes Christ standing against the sky. And just as Brown was inspired by Christ’s body, the story calls us to be inspired by Brown’s. Lawrence’s politics are his comics. The twenty-second panel, the page which isn’t drawn, is a cluster of people which includes John Brown, God, and us.

The community that Lawrence includes us in is an antiracist one—and more, a revolutionary antiracist one. That is not a community that Crumb easily fits into.

Crumb has been widely praised for opening up artistic expression in comics, in part because of his use of racist and sexist caricatures, which are framed by fans as a daring violation of political correctness. But the truth is that racist caricatures have long been a part of comics iconography—Little Nemo, Tintin, The Spirit, Mickey Mouse, and more, all used blackface iconography. Crumb’s blackface imagery may be satirical, sometimes. But the satire, mocking Crumb’s own investment in blackface imagery by employing it, is still a far cry from a call for solidarity with black people, much less an actual demand for the violent overthrow of a racist system.

Crumb may open some possibilities for other cartoonists who are interested in autobiography, and in controversial imagery carefully disconnected from any sort of collective political program. But for cartoonists who might be influenced or inspired by Lawrence, Crumb is a barrier, not a resource. After all, if booing Crumb is an act of ignorant ingratitude, what to make of John Brown actually murdering people to try to overthrow the civilization that had given him those guns, and that Christ? Is antiracism just a perversion of a freedom given to you by a white guy? Or is it its own tradition, with its own power and its own inspirations?

This isn’t to say that comics has no radical collective tradition. On the contrary, comics includes Marxist cartoonists Art Young and Boardman Robinson, John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell’s March, Diane DiMassa’s Hothead Paisan, and for that matter the William Moulton Marston and H.G. Peter Wonder Woman. Those are all examples of consciously-political cartooning, which compliments and contextualizes Lawrence’s work. Crumb is much more canonical than any of these artists at the moment. But that’s a choice, not some sort of absolute truth.

Crumb opens certain possibilities for certain cartoonists. But those are not the only possibilities. People who reject Crumb aren't necessarily his children, and they aren’t necessarily in his debt. They may instead be trying to clear ground for alternate traditions, which have been buried and restricted—not liberated—by Crumb’s ascendance.

What would comics look like if Jacob Lawrence occupied the place of reverence and influence that Crumb has been granted? It’s impossible to know for sure. But a good guess is that they would be less white. It would also, in certain respects, be more free.

Had I so interfered on behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great, or on behalf of their friends […] and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference […] every man in this court would have deemed it worthy of reward rather than punishment.

—John Brown

0 notes

Text

@duel1971 sounded off in the replies so here we go~

Keep Watching The Skies!: American Science Fiction Movies of The Fifties has been an invaluable resource for me since late 2018 when I got back into this era of the genre, though I only just now got a physical copy of the two volume set. It's pretty exhaustive but its concept of what a "1950's" "American" film is a bit loose. Films that were produced in the 1950's but didn't come out until the 1960's are included, as are American edits of previously foreign films, which, okay, but it stretches the limits when including the 1962 release of Mothra (1961).

Trying to "figure out" Jack Cole lead to me to picking up Forms Stretched To Their Limits, a published adaptation of an article by Art Spiegelman for The New Yorker with layouts by Chip Kidd (truly...Spiegelman's finest work (sarcasm)). Where "critical study" and "celebration" and "photo book" and "reprint collection" begin and end is completely arbitrary with Forms, making it a bit hard to discuss or recommend. I will say that I was under the impression that Spiegelman didn't like superheroes so him writing a book about Plastic Man mostly was a surprise to me. Probably the most interesting thing is when reprinting full stories it switches from glossy magazine stock paper to newsprint, nice touch.

Kidd also did Shazam: The Golden Age of The World's Mightiest Mortal, which as far as I can tell is the only book that DC released to celebrate or promote Shazam (2019). It's mostly a huge photo reference book of merchandising and memorabilia surrounding Captain Marvel, which is a subject that had mostly been lost to time. Carmine Infantino had mention that comics companies have historically made the majority of their profits off of licensing rather than actual comics and yeah I can see it with all the stuff on display here.

Continuing with Cole, I also picked up some volumes of Yoe Books' Chilling Archives of Horror Comics, his and Dick Briefer's Frankenstein. Cole's volume is pretty exhaustive, collecting all of his horror comics from Web of Evil, which, he can draw some pretty disgusting caricatures ill say that at least. Briefer's volume is more of a highlight reel than anything with how thin it is, so the quest to read more of his Frankenstein shall continue...elsewhere...

I don't know what I was on a kick with 1950's horror comics but I've already mentioned Four Color Fear and The Horror! The Horror! here on Tumblr, both essential collections of material that wasn't published by EC, which gets all the attention with this genre in this decade.

Art Out of Time is one I was super excited about and it didn't disappoint, showcasing a ton of artists in comic strips and comics proper that did their job unconventionally. Some of the talent on display here (Dick Briefer, Fletcher Hanks, Ogden Whitney, etc.) aren't as "unknown" as they were in 2006 but plenty here still are; probably my favorite discovery so far is Gustave Verbeek and his comic strips that at first glance look like knockoff Winsor McCay stuff but reveal their oddities on closer inspection.

Finally we've got some Kirby and Ditko studies. Hand of Fire I'm not sure what I'm getting into yet, I just know Charles Hatfield sent out a public invite for anyone who wanted to contribute critical analysis of Kirby's work for a future book and my Devil Dinosaur proposal was rejected (the wounds are still fresh). I'm familiar with Chris Tolworthy's investigative work surrounding Kirby online so I was curious about The Lost Jack Kirby Stories; befitting a self-published work with little oversight, right now I'd say it's 50% legitimate uncovering and 50% conspiratorial nonsense that is just giving ammo to Lee sympathizers, but I digress. Mysterious Travellers is a political analysis of Ditko's entire body of work, I entirely grabbed it because I feel an obligation to grab all the stuff about Ditko published posthumously, of which we've totalled...three books in total now? Including Working With Ditko, discussing Ditko's overlooked time spent at DC in the 1970's.

Someone ask me about books I've recently gotten plz.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

How long will the Muslims go to know Ram in the name of Ram?

#Funny Cartoons#funny cartoon#funny political cartoons#political caricature 2019#political cartoons 2019#indian politics cartoons#indian political cartoons#Funny Memes#jharkhand muslim case#mob lynching#molitics

1 note

·

View note

Text

It is okay to like Homelander.

This isn’t a very structured essay but it was something that has been bothering me for awhile.

I’ve been a huge fan of The Boys and have watched all the seasons and frequently browsed for content of the The Boys from Tumblr, Reddit, to Facebook. But something I noticed within more mainstream spaces is this certain type of gatekeeping and morally virtuous stance a lot of the more common fans tend to have.

I’m not going to ignore the type of show The Boys is and their stance on certain political issues especially with current events. And in a way, I think this connection to real life creates vitriol inside the fandom. Especially the effects it has on fans and their ability to enjoy certain characters in the show. Like the character Homelander.

--------------------------------

First, lets take a look into an overall view of The Boys, politics, and how it ties into Homelander.

The Boys is a show available to be watched on Amazon since 2019. So far it has three Seasons under its belt. It grew in popularity ever since the increase rise in the ‘evil superman’ trope and an attempt to create a world where if superheroes existed in our current climate. This is a very simple idea but was executed very well and the show gain monumental popularity.

But by the start of Season 2 where the show started to introduce more political issues, that is where the majority of the disagreement between fans began to emerge. Storefront and what she stood for created a lot of discourse. Her character is not a good person and her views are considered to be unacceptable and inhumane both in actions and in ideologies. She was meant to be hated and the show succeeded in that. But like Homelander, there are going to be fans of hers and who like her for various reasons that I won't get into today.

But the politics began to ramp up in Season 3. Instead of nazis, The Boys took a lot of inspiration from current events. According to Kripke, Homelander was supposed to be a caricature of he previous sitting President, Donald Trump, and his supporters the Republican/Conservative people.

There are of course much needed criticism for the Republican Party, but the blatant favoritism and antagonism towards the other half of the American population creates a division between people. By showing Republicans and Republican talking points as black white and only used for the morally worse characters is no longer satirical and actually frames millions of people as the wrong ones.

I am not going to speak on which party is wrong or not because there are issues in both, but the inclusion of current events and the demonization of one party over the other pits fans against each other which is something that should never happen. It has reached levels of no longer simple disagreements but a pure hatred for those who even have an inkling of such views. This full on display of hatred carries over to even casual fans who just want to enjoy the characters.

As how for the end of Season 3, Episode 8, Homelander murdered a man who threw a can at Ryan during a rally/speech event. This prompted other’s to cheer for him, which is Kripke’s way of satirically showing the supposed cult-like evil of the party (Rep/Conservs) and Homelander (Trump).

This stance is further displayed during the scene where a fan of Stormfront murdered someone in her name or when Ashely notified Homelander that his base rose with people in more Red States. The Boys in general are meant to a social criticism on what America stands for and the ‘fraudulent’ show they put on to the world in order to hide their atrocities through Homelander.

According to Reddit and Facebook posts, when Republican fans of The Boys point out criticisms they have of being openly mocked and associated to nazis, other fans claim they are offended because the show is just telling the truth of their nature. No one wants to be seem as evil and this type of accusatory language towards one another will not lead to the endgame that many people think it will lead to.

The majority of fans and watchers are usually okay with such blatant satire, but the current climate has created discord amongst the American population.

-------------------

Homelander’s Fans

During Season 1, many people who enjoyed Homelander and his antics weren’t met with as much antagonism. Compared to other villains from other stories, he was a unique take and is a complex character. The Boys did an amazing job at showing how his background and his development turned him into the insane, insecure man he is today that still craves for affection he never got. Where all his life he chases after love that he doesn’t even know how it looks like. Through that aspects of Homelander, I think they did a great job at truly showing how broken he is.

But the issues started once Homelander started becoming Kripke’s projection or ideas of what he believes is the sins committed of the Red Party. And The Boys taking inspiration from current events. In a lot of people’s eyes, those who like Homelander are just as vile as he is because why would you like a murder, an insane person, didn’t argue against Stormfront’s ideas, Trump-personified, rapist, manchild? Because he is so vile, the only people who like him must support such people and are therefore not worthy of respect.

Homelander is not a good person. But he is not the worst compared to other characters like Frieza, Griffith, Dio, Voldemort, and many others. Frieza commits mass planet genocide which is nothing compared to Homelander’s actions but he is seem in much more positive light and has a high amount of fans who love him for his power and for his memes. Homelander doesn't get that treatment and that is because of the issue surrounding him and the politics in the show. Because of the divisive nature of the political side he represents, many people view those who even like him or sympathize with him as evil as well, nazi sympathizers and the like. A show should be an escapism and I think too many tv shows and movies are trying to bring real life into media which just causes people to argue just like they do in real life.

As a long-time lurker and contributor to many fandoms, I hate to see a show as amazing as The Boys fall into the trap of judging other fans for liking evil characters. The majority of people who like Homelander do not support nor justify his actions. But he is a villain, has a tragic backstory, and is written well which draws people towards him. No one should be seen as evil for liking a fictional character that has done questionable things.

Of course there are going to be people who create apology posts for characters like Dabi or other tragic characters. Even then, they don’t deserve hate. It is just another way of interacting with the fandom and creating interpretations for their actions. Civil disagreements are important but calling for their death or harm on them for having questionable or unusual takes makes you no better than what you are accusing that person of. Just like fanfiction and many types of manga. People write a variety of taboo subjects but they are fictional and they need to stay that way. Bringing real-life issues into what is supposed to be a sort of escapism will just push for more divide in the fandom.

Homelander with all his flaws and personifications doesn’t deserve to be the scapegoat for those who aim to villainize his fans. People should be allowed to love him in all his glory and create all the fan content they wish to make without feeling like they are committing a crime.

#rant#homelander#the boys#they boys amazon prime#it's okay to like homelander#it is okay to disagree#the homelander#social analysis of the the boys#political commentary#essay

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the last few weeks, we have witnessed the remarkable spectacle of a Conservative government in Britain deliberately taking on the financial markets. With a surprise mini-budget promising 45 billion pounds (about $48 billion) in tax cuts targeted at high-earners, Prime Minister Liz Truss and Chancellor of the Exchequer Kwasi Kwarteng unleashed a currency and bond market crisis the likes of which Britain has not experienced since sterling was driven out of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1992. At that time, Europe as a whole was convulsing. This time, the crisis was Britain’s alone. The last time a Tory government was subject to such near-total condemnation by global expert opinion was in 1956 amid the Anglo-French invasion of Egypt over the Suez Canal.

Of course, Brexit in 2016 was condemned by most reasonable international commentators as well. But that was not the policy of David Cameron’s government. It was an insurgent campaign led by Boris Johnson and the UK Independence Party. It was Johnson’s boast that he had defied “Project Fear”—the mobilization of establishment opinion against the Brexit campaign. Faced with a phalanx of mainstream opinion that included U.S. President Barack Obama and Jamie Dimon of JPMorgan Chase, Johnson dismissed concern for the future of British business with an expletive. He thus marked the moment at which the leading group within the Conservative Party separated itself from any conventional commitment to the “U.K. economy,” in favor of a more nebulous idea of national destiny and the more specific interests of Tory cronies.

Ever since, the political economy of Britain increasingly has resembled the annual showcase of Wimbledon—in cultural terms, a very British affair, celebrated around the world as such, but rarely a stage on which British players actually shine and certainly not an event to which the majority of the population is actually invited.

Preoccupied with Brexit and COVID-19, Johnson did not have time to develop an extensive program of government. Like the Cameron and May administrations, Johnson’s most important constituency appears to have been a rentier class of hedge funds and public-private contractors. But, as his electoral triumph in 2019 attested, Johnson also managed a broad-based political coalition ranging from patriotic working-class voters in the north of England to upper-class London types.

It is no secret that the Tory party has long included a more radical fringe. This includes figures such as Jacob Rees-Mogg, affectionately known as the member of Parliament for the 18th century. Johnson made sure to keep this wing of the party within his tent but balanced them with centrists like Rishi Sunak. Elected to Parliament in 2010, Truss and Kwarteng belong to a cohort of Tory politicians who have never known opposition. Neither has deep roots in the Tory’s traditional social milieu. Truss’s parents were Labour voters. She and Kwarteng were incubated by a coterie of free market, right-wing think tanks that first came to the fore during Margaret Thatcher’s rise to power in the 1970s and now thrive on obscure funding by dark money—some British, some not. When Johnson lost his grip, it was Truss and Kwarteng’s moment. Whom they represent apart from the 80,000 or so Tories who voted for Truss to replace Johnson is not obvious.

In style, their program was a quintessential post-Brexit manifesto, high on ideology and blustering self-confidence, promising a dramatic new vision of Britain’s future but lacking details. In substance, it was caricature of the rentier program, promising to slash taxes, roll back environmental and labor regulation, and cut already impoverished welfare benefits.

It stretches credulity to suggest that they actually believe this is a formula for national economic growth. It is certainly an agenda for greater inequality. They even appear to support an end to easy credit and low interest rates, despite the damage this will likely do to heavily mortgaged homeowners, once a core constituency of Thatcher, whom they claim as their hero. Trying to make sense of this seemingly perverse policy, some speculate that Truss and Kwarteng are so deeply beholden to rentier interests that they are exponents of disaster capitalism, provoking a housing crisis that would allow property companies to snap up large portfolios of distressed properties. The fact that analysts are driven to such far-fetched speculations points to quite how implausible the Truss-Kwarteng vision for Britain’s economic future seems.

It certainly didn’t make sense to the financial markets. The pound plunged. Bonds sold off. As yields surged, that triggered obscure derivative hedging strategies in the portfolios of private pension funds and threatened to unleash a fire sale of gilts, or U.K. government debt. That, in turn, forced the Bank of England to react. To stop the slide, it stepped in as the market-maker of last resort, warehousing debt that pension funds needed to sell for cash. The result is conflicting policies. On the one hand, like other central banks around the world, the Bank of England is promising to raise interest rates. At the same time, to prevent the financial system from imploding, it has to engage in another emergency burst of quantitative easing, buying bonds in exchange for cash.

In the short term, this has provided relief. The pension funds have been saved. The pound rebounded. Yields fell back. But it was not enough to save Truss and Kwarteng’s embarrassment. On the weekend of the party conference, they reversed the controversial tax cut.

The Tory party’s reputation both with the population at large and its own supporters is in tatters. Labour, under the uninspiring but reliable leadership of Keir Starmer, rides high in polls. Unless Labour finds a way to shoot itself in the foot, the party will, come the next election, inherit Britain’s ailing economy and threadbare welfare state. If the current opinion polls hold, it will have a giant majority. But given how parlous the state of the British economy is, no one governing in the U.K. faces good options. If there is a shred of reality in the Truss and Kwarteng program, it is a realization, after more than a decade of low growth and stagnating productivity, of quite how serious Britain’s economic impasse is.

One could dismiss the U.K. crisis as an idiosyncratic storm in a teacup. But that was not the view taken by global bond markets, which all experienced a moment of panic in reaction to the turmoil in London—and with good reason.

The British crisis highlights the huge stress that economic policy is under, worldwide, but particularly in Europe. The recovery from the COVID-19 shock was rapid but uneven. Inflation has tested the credibility of central banks. Now the energy crisis unleashed by Russia’s attack on Ukraine is convulsing the European economies. For lack of natural gas, it is not sure that any of them will get through the coming winter without drastic rationing measures and a severe recession.

The 45 billion pounds in tax cuts announced by Kwarteng made the splash that they did because they followed the unveiling of a far larger program, with cost estimates of up to 150 billion pounds, to stabilize energy prices. At the time, the program, valued at around 5 percent of Britain’s GDP, was the largest in Europe. This week, it was matched by a 200 billion euro ($195 billion) commitment from Berlin.

Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s announcement ruffled feathers in the rest of Europe, but German bond prices barely budged. Unlike British debt, German bunds are anchored as the benchmark assets of the eurozone. The real question for the financial stability of Europe will arise when Italy is forced to announce an energy subsidy package of similar dimensions. Italy’s public debt is already far too high for markets to easily absorb a program of German or British dimensions. The only country with a worse track record of growth in Europe than the U.K. is Italy.

But the lessons of the U.K. debacle are political as well as economic. The disintegration of the Tory party points to basic questions haunting modern conservatism. We may not be in the 19th century, when defenders of the status quo struggled to contain the threat of revolution. But the pace of social, cultural, technological, economic, geopolitical, and environmental change in the 21st century is frenetic. How should conservatives respond? If you run to the center as Angela Merkel did with the Christian Democratic Union in Germany, you risk being outflanked by more credible liberal and environmental parties and challenged on the right by openly nationalist and xenophobic parties. If you move to the right, you can win success as Giorgia Meloni has done in Italy and Jair Bolsonaro and Donald Trump did in Brazil and the United States, respectively. All three demonstrate the appeal of an authoritarian, nationalist agenda. But as much as they grab the headlines, none of them is resoundingly majoritarian. Their positions are too extreme for large segments of the modern electorate. And it is altogether unclear how their promises and their vote-winning populism translate into a constructive agenda for government.

Of course, centrist and progressive governments fail, too. The COVID-19 crisis offers a veritable how-to guide of governmental failure. But tantrums like the one we have just witnessed in the U.K. are not accidents. They are part of a piece with the meltdown of the Trump administration in 2020 over COVID-19 and the Black Lives Matter movement; the Brexit shock; the dogmatism of Germany’s stand in the eurozone crisis; and the recalcitrance of Republicans in the United States during the 2008 financial crisis. Conservatism in the 21st century has a reality problem, and sometimes it bites.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Latter half of the 10s. The meh era.

So the assassination of Nemtsov was like a bucket of cold water dumped on the rest of the opposition. Cold water with shit in it.

Nobody talks about it that much, but everyone got scared.

Protests became smaller. Some big ones still happened, but the momentum of the Bolotnaya was never reached again. A lot of people decided to shut up and focus on their own lives and ignore the politics.

The economy and the situation in the country post-Crimea was also meh. It wasn't the 90s. It wasn't even like today. But it was no 00s either. Just kind of okay.

Katz did his youtube and urban development shit. Navalny, as I've said, went full-on anti-corruption.

He created the Anti-Corrupton Foundation with Volkov and a few other loyalists. It was a hit. They exposed the lives and real riches of the Russian oligarchs - their villas, their yachts, everything. And also how much of that wasn't fairly earned, but a result of corruption and bribery on a truly massive scale.

In 2017 he releases "Don't Call Him Dimon" about the ex-"president" Medvedev. This destroys Medvedev's reputation and forces him to become an alcoholic and a caricature of himself.

And then kind of nothing much happened for a good long while.

Like, yeah, there were the constitutional reforms in 2018. The opposition tried to organize against them, couldn't form a unified strategy and everything fell apart. In 2019 during the parlaimentary elections Navalny launched "smart elections". It was an app that showed which non-United Russia candidate was the most likely to win in your local elections. The results were uninspiring.

Then in 2020 Navalny gets poisoned. By the Putin's stooges, of course. Probably because big P had enough of his antics.

Navalny barely survives and gets treatment in a Berlin clinic. And here's something I forgot to mention: during all this time Navalny was under criminal investigation. The state tried, ironically, to pin corruption on him. But he was realesed during his trial, because the judge, for once, was sane.

During his recovery in Berlin he was warned that if he ever returns to Russia he will be arrested again. He returns anyway. And gets arrested as soon as the plane touches the ground.

To this day he is still in prison and to call his treatment "inhumane" would be a massive understatement.

His team releases their most popular video yet. A big expose on Putin and his palace and yachts.

But nobody really cared.

Because a year later, Russia invaded Ukraine.

A big rant about the Russian opposition

Well, you said you wanted it, so here it is.

Be warned: this will be long, rambly and unfocused. But I will try to split it into several parts.

Where it all began. The 90s.

Following the collapse of the USSR, Russian opposition was left in a weird state. Big Soviet-era opposition figures like Yeltsin now held all the power, yet, at the same time, the government was full of ex-Soviet party members. See, ol' Boris didn't want to do a lustration. I don't have his exact motivations, but, if I was put at a gunpoint and forced to guess, it was because Russia, even without all the states that left was a BIGHUGE country and needed people who knew how it all worked. And all of them happened to be party apparatchicks.

Yeltsin also left the KGB eseentially untouched. This is not well-known, but KGB were actually supportive of the fall of the USSR. Now, late-Gorby KGB is not the same as KGB during Stalin or even Khruschev. They were de-fanged and forced under too much supervision. Which they didn't like. So they were allowed to change their name, had some reshuffling and re-emerged as FSB. Ostensibly, just there to fight crime and protect the state, no disappearing people allowed anymore.

This is important to understand as we go forward.

90s were, overall, a time of terrible, terrible poverty and unimaginably, unprecedented freedom in Russia. If you knew what to do and was willing to do it, you could become a millionaire overnight. If you didn't have a particuarly marketable set of skills or was just unwilling to adapt, you'd be on the brink of starvation. And that's me not even touching the organized and disorganized crime which was absolutely rampant.

Then there was the privatization. Essentially, Yegor Gaidar, the prime minister during Yeltsin's first term decided that the best course of action was to take this lumbering 70-yo communist system and crash it head-first into capitalism. It was even called "shock therapy".

Now, in hindisght, we can say that his policies very much saved Russia and lead to economic prosperity later on. But man, shit was HARD for regular people. Especially hordes of state workers.

His most infamous project, however, was the privatization. Essentially, since EVERYTHING in USSR was state-owned and we were moving towards a capitalist system, someone needed to become the owner of all this state property. Privatize it, so to say. Of course, regular people could privatize their cars and apartments, which most everyone did. But the big bucks were in all the factories and natural resource mines. And this was done in the most ass-backwards way possible. People with connections got to bid on very lucrative property in the dead of the night with only one announcement in the local newspaper nobody read. Shit like that.

Everyone disliked that.

This is how Russia became saddled with it's giant oligarchy class.

I promise all of this is relevant.