#podocarpaceae

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

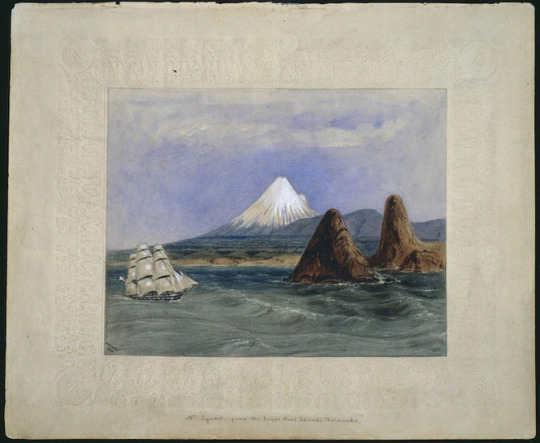

The Great ACT-NSW-NZ Trip, 2023-2024 - Taranaki Maunga

A 2,518 metres (8,261 ft) tall stratovolcano, ideally positioned to catch every change in the weather coming off the Tasman. As a result it gets up to 11 meters of rain a year, and the winds between the peak and the remains of its predecessor can exceed 130kph.

Naturally, of great importance to the local iwi, and it certainly made an impression of the Europeans too - although a lot of early paintings exaggerate the height.

watercolour by Charles Heaphy, some time between 1839 and 1849.

They named it Mt Egmont, although happily the original name is back to being the official one.

The volcano erupts, on average, every 90 years, with major eruptions every 500. Of considerably more concern are the repeated catastrophic cone collapses that turn most of the volcano into gigantic landslides sweeping fridge-sized boulders and smaller debris dozens of kilometers away from the volcano, and well past the current coastline.

Anyway, while we wait for it to go bang again, visitors can enjoy the fascinating change in vegetation as you go up the mountain. As you get higher and higher, the coastal vegetation is replaced by the goblin forests, contorted mossy woods dominated by Kamahi (Weinmannia racemosa), that developed after eruptions destroyed the preexisting podocarp and Nothofagus forest, and as you go higher the trees are replaced by tussock grasses and later alpine plants.

There are still kiwi in the national park, which is one reason dogs are strictly banned. The introduced stoats continue to be a problem - we saw one on one of the tracks.

There was also this building, a corrugated iron structure noteworthy for being the oldest such building left anywhere in the world. It was originally a fort, and still has gun slits. The windows are new.

Most of the species I saw around the visitors center are were new to me - I could have spent a week just phtographing the incredible lichens in the goblin forest. Here's some that weren't new.

And a few lichens I don't have an ID on.

#taranaki#new zealand volcano#mount taranaki#taranaki maunga#orocrambus#new zealand moth#crambidae#miro#podocarp#new zealand plant#Pectinopitys#podocarpaceae#asteraceae#Olearia#kamahi#Weinmannia#Cunoniaceae#Charles Heaphy#asplenium#new zealand fern#aspleniaceae#spleenwort#goblin forest

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

asking you about coryneliaceae :) gimme the fungus

WOOHOO!!

So they're a family of parasitic fungi that live in the tropics and are really into one particular family of conifers for their hosts-- Podocarpaceae. Lagenulopsis, a lonely genus with only one species (L. bispora), is especially picky-- it'll only dine on living Podocarpus trees. It was first found on P. milanjianus, which is a very useful tree for us (pretty/ornamental, provides good shade for tea and coffee crops, some medicinal stuff apparently but I don't know the specifics). The uses are cited from that species's Wiki page, lol.

Speaking of Wiki, I have a whole Wiki article ready to go for L. bispora that I'm just awaiting feedback from my prof for, but it should be up for the public sometime next month, and I can't wait to share it here! I'm only not sharing the draft publicly cuz my rumination brain is like "what if someone decides to just upload my work and I don't get the credit" 💀

Corynelia and Lagenulopsis sexual fruiting bodies (ascomata) look like teeny tiny black spiky balls when they're in a group, and look kinda like Coke bottles individually, especially Lagenulopsis. Again, despite my own feelings on copyright law, I'm really trying to avoid using anything I don't have the rights to when it comes to academia shit, otherwise I'd repost some pictures directly into this ask, but if you search for Lagenulopsis bispora, you'll immediately see some good pics in the image results. That journal that the first several you'll see are from is also pretty nicely comprehensive.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

More at Wisley - Waterfall Hill Garden

Dry sunny rock garden. This made me think I should redo the slope to the side yard at home with a waterfall. The sound of water is good.

Can not find in US...but love the gray spineyness of this.

Erodium is a type of geranium. These are alkaline-loving and long summer bloom time. Typically they like alpine conditions so that is why I love them, I cannot grow them here.

Incised Fumewort or Corydalis decipiens is "a spring-blooming, tuberous perennial with attractive purple flowers and ferny foliage, typically found in woodland settings" and is available in the US and it is adaptable. Below left is Galanthus which I forgot, is Snowdrops. I don't have any of these and I won't start now because they are so aggressive.

Above right, available at Brent and Becky's bulbs and one I will get: Often misnamed ‘Autumn Crocus’, cup-shaped flowers on naked stems; poisonous and tastes bad to critters that may be tempted to eat them; flowers appear in the fall and foliage, which resembles hosta leaves, appear in the spring; prefers rich, well drained soil and partial shade to full sun; many are species and are variable in their color and growth habit. Bloom mid-late fall; can bloom without being planted in soil; 3 per sq. ft; WHZ 4–8; 13/+ cm unless otherwise noted. Colchicum are long term perennial bulbs that get better each year.

Persicaria (below) is a weed here so I'd hesitate to plant this but it is super interesting leaf color and shape. It is for shade.

Andromeda polifolia is Blue Ice Bog Rosemary and I LOVE IT. "A very small shrub for detail use in gardens, icy blue needle-like foliage and pink urn-shaped flowers in spring; very fastidious as to growing conditions, needs ample consistent moisture and highly organic soils, will not tolerate alkaline soil." The bloom photo is from the internet search. Available by mail order and I think I'll try it if it can handle the heat in MD. More good GRAY foliage that I need! Really expensive and fussy.

This leaf color is so cool for a peony. It is a Majorcan Peony, for rock gardens in Mediterranean climate. I'll keep an eye out for it but not easily found in the US.

This was fun to explore and I needed more time...maybe another visit.

This little grouping was so gorgeous. The white flowers of mossy rockfoil saxifage are sweet. It is an alpine rock garden plant that would not like it here. I think I have tried it unsuccessfully in the past.

Above top middle of photo, the weird needle/leaves caught my eye. It is ridiculous here since it is supposed to be a giant conifer eventually. From Wikipedia:

"Phyllocladus alpinus, the mountain toatoa or mountain celery pine, is a species of conifer in the family Podocarpaceae. It is found only in New Zealand. The form of this plant ranges from a shrub to a small tree of up to seven metres in height. This species is found in both the North and South Islands. An example occurrence of P. alpinus is within the understory of beech/podocarp forests in the north part of South Island, New Zealand."

I like artemesia- Dusty Miller - but it never lasts long in the garden.

I wonder if this is true of silver gray foliage in general? I'll try it again. Santolina died out in the sideyard garage garden. It looked really good there so I need to try for that gray again.

This is Common Everlasting, I think. It is a pacific native and the best texture for summer gardens? Lathyrus vernus has a tag but the plant is not present. "Lathyrus vernus is a non-climbing perennial sweet pea. It is a multi-stemmed, clump-forming plant with a bushy habit which typically grows to 12" high. Typical pea-like flowers (3/4") are borne in axillary racemes (5-8 flowers each) in April. Flowers are reddish purple with red veins, becoming more violet-blue as they mature. Pinnate, light green leaves (each divided into 2-3 pairs of 3" long, ovate leaflets) lack tendrils." Worth trying.

Below is another good gray groundcover that will not like the humidity here. Basket of gold is common but nice.

This yellow-green (below) is so good to cut the blue greens. Common name is box-leaved Honeysuckle or Privet and both names are scary.

MOBOT: 'Twiggy' is a compact yellow-leaved sport of 'Baggesen's Gold'. It typically matures over time to only 2-3' tall. This shrub features drooping, twiggy branches clad with tiny, golden yellow, evergreen leaves. White flowers in spring. Purple black berries in fall. Yellow leaves take on bronze tones in winter in areas where plants are evergreen (USDA Zones 8 and 9), but will drop to the ground where deciduous (Zones 6 and 7).

Snow in Summer, ubiquitous ground cover in midwest suburban gardens, Greg makes it look good.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

We all know what conifers are, don’t we? They’re evergreens with needles rather than leaves. But what about larches? They’re not evergreen. And cypresses have scale-like leaves, not needles. And let’s not even talk about monkey puzzle trees! The answer to the question “what are conifers” isn’t so clear. These plants are actually defined by their method of reproduction, not their foliage. Many species are indeed evergreens with needle-like foliage, but not all. What they all have in common is that they produce reproductive cones instead of flowers. I live in one of the most conifer-dense regions in the world, and I’ve developed a deep fascination for these plants. Not only do many of them look lush and green even during the winter, but they need hardly any maintenance at all in the garden. I’m just dying to discuss even more about conifers, so without further ado, here’s what we’ll be going over: What Are Conifers? There is one characteristic that defines these plants and it’s not the presence of needles or whether or not they are evergreen. All of them bear cones with seeds inside. In fact, that’s what the word conifer means. It’s Latin for conus, meaning cone, and ferre, meaning bearing. It’s a cone-bearing plant. They all have two types of cones: females and males. The male cones are small, soft, and contain pollen. The female cones are larger, woody, and contain the seeds. In many species, the pollen is carried a short distance by the wind. Male and female cones on a mugo pine. Conifers are gymnosperms, meaning they are woody, seed-bearing plants. All of the about 650 existing species within seven genera are woody perennials that are either trees or shrubs. The vast majority have a single main trunk. They can be low-growing and under nine inches tall, like dwarf Japanese juniper (Juniperus procumbens), and over 300 feet tall in the case of coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens). Most prefer full sun and somewhat dry soil, and all are wind-pollinated. The leaves are typically needle-like or scale-like, with the needles in either linear or acicular shapes. Most are evergreen, but others are deciduous. When we say “evergreen” it doesn’t mean they hold their needles indefinitely, they just don’t shed them all at once like deciduous types do. Instead, they drop a few here and there that are constantly being replaced, giving the appearance of having persistent needles that last forever. Many conifers produce sap, also called resin or pitch, which is a natural protection against pathogens and pests. Many pests are put off by the fragrance of the resin, but they can also become trapped in it if they try to feed on the plant. If one of these plants is wounded, it sends resin to the area to flood out pests and pathogens that might cause infestation or infection. Some conifers want to attract birds to their cones to help spread the seeds. These will typically grow upright cones with short or non-existent stems. That allows the birds to easily perch on the branch and feed. Some Examples The pine (Pinaceae), podocarp (Podocarpaceae), and cypress (Cupressaceae) families make up the largest conifer families, but there are also the Araucariaceae, Sciadopityaceae, Cephalotaxaceae, and Taxaceae families. All the needle-laden trees like cedars, Douglas firs, true cypress, firs, junipers, kauri (Agathis), larches, pines, hemlocks, redwoods, spruces, and yews are conifers. There are deciduous types, including some larches, bald cypress (Taxodium distichum), and dawn redwoods (Metasequoia spp.). These will lose their foliage in the fall and develop new leaves in the spring. When it comes to conifers in the garden, pines, cypress, yews, and junipers are the most popular in North America. Where Do They Grow Wild? After the last ice age, many conifer species became extinct because flowering plants, which are better adapted to the warmer conditions of the modern climate, took over. But there are still a few areas where flowering plants haven’t managed to outcompete with conifers. The Pacific Northwest is one area where conifers thrive and that’s because evergreen leaves need a climate with a long, mild growing season. They also do well in areas that have little moisture in the summer and ample moisture the rest of the year. They’ve also adapted to grow in poor soil where flowering trees and shrubs fail to thrive. You mostly find conifers in colder regions in northern latitudes. The two cold-hardiest trees in the world, the Dahurian larch (Larix gmelinii) and the Siberian larch (L. sibirica) are conifers. The rarest type in the world, the Monterey cypress, comes from a tiny corner of southwest Oregon and northwest California. There are just a handful native to the Southern Hemisphere. These belong to the Araucaria, Podocarpus, and Agathis genera. Form and Reproduction Most conifers, at least in their natural form, have a conical shape with a strong central leader. This shape maximizes the light exposure available to the branches and needles. As mentioned, what sets conifers apart from flowering plants is how they reproduce. These plants have petalless flowers on inflorescences that make up the immature cones. All conifers have male cones that contain the pollen and female cones that hold the flowers and seeds. The male cones are typically soft, with scales that hold the pollen inside until it’s ready to release. Once it releases, it’s carried on the wind, water, or by animals and there can be an impressive amount. If you’ve ever stepped outside to find everything covered in yellow powder, you’re probably looking at pollen from a nearby conifer, like a pine tree (Pinus spp.). The pollen finds a female cone, which is usually soft when young, becoming woody when mature and pollinated. The scales open to allow the pollen to find the seeds inside, and they’ll often exude a bit of resin that helps the pollen stick. Then, the scales close back up to protect the pollinated seed. Some seeds are winged so they can be carried on the wind and others wait for birds or other hungry animals to eat them and carry them far and wide. If you go for a walk in a coniferous forest in the spring, you’ll likely notice the seedlings popping up all over the place. Most cones are pollinated and drop from the tree in the same year, but quite a few take two or even three years to release the seeds. You might hear some cones referred to as “fruits,” such as those on junipers and yews, but they aren’t technically fruits. They’re cones, they just have fleshy scales. Quick Guide to Identification It can be hard to tell all the various conifers apart. Although it’s a lot more complicated than this, you can generally determine which type it is based on how the needles attach to the stalk. If the needles wrap around the twig, it’s likely either a yew (Taxaceae family) or a cypress (Cupressaceae family). Needles with a round base that leave behind round scars when they fall or are torn off are true firs (Abies spp.). Soft needles in clusters of 15 or more that attach together at the base via a spur are larches (Larix spp.), while 15 or more stiff needles on a spur are true cedars (Cedrus spp.). Needles in groups of two, three, or five with a papery envelope at the base, it’ll be a pine (Pinaceae family). Scales attached to the stem are junipers (Juniperus spp.). If the needles attach via a small peg perpendicular to the stem, you’re probably looking at a spruce (Picea spp.). If there’s a tiny perpendicular stem, it’s likely a Douglas fir. Finally, if the needle has a bit of stem that grows parallel to the main stem, it’s a hemlock (subfamily Abietoideae). You can learn more in our guide to conifer identification here. Conifers Are So Cool! I really think these plants are so cool – they have some really fascinating adaptations. Wait, now as I’m reading that sentence, I’m realizing that I am officially a plant nerd. I can’t be the only certified conifer nerd. What do you like about these plants? Which are your favorites? Let us know in the comments section below! And if you love conifers as much as I do, you’ll likely want to learn more about them. Add these guides to your reading list next: © Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. !function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s) if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function()n.callMethod? n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments); if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version='2.0'; n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0; t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)(window, document,'script', ' fbq('init', '176410929431717'); fbq('track', 'PageView'); Source link

0 notes

Photo

We all know what conifers are, don’t we? They’re evergreens with needles rather than leaves. But what about larches? They’re not evergreen. And cypresses have scale-like leaves, not needles. And let’s not even talk about monkey puzzle trees! The answer to the question “what are conifers” isn’t so clear. These plants are actually defined by their method of reproduction, not their foliage. Many species are indeed evergreens with needle-like foliage, but not all. What they all have in common is that they produce reproductive cones instead of flowers. I live in one of the most conifer-dense regions in the world, and I’ve developed a deep fascination for these plants. Not only do many of them look lush and green even during the winter, but they need hardly any maintenance at all in the garden. I’m just dying to discuss even more about conifers, so without further ado, here’s what we’ll be going over: What Are Conifers? There is one characteristic that defines these plants and it’s not the presence of needles or whether or not they are evergreen. All of them bear cones with seeds inside. In fact, that’s what the word conifer means. It’s Latin for conus, meaning cone, and ferre, meaning bearing. It’s a cone-bearing plant. They all have two types of cones: females and males. The male cones are small, soft, and contain pollen. The female cones are larger, woody, and contain the seeds. In many species, the pollen is carried a short distance by the wind. Male and female cones on a mugo pine. Conifers are gymnosperms, meaning they are woody, seed-bearing plants. All of the about 650 existing species within seven genera are woody perennials that are either trees or shrubs. The vast majority have a single main trunk. They can be low-growing and under nine inches tall, like dwarf Japanese juniper (Juniperus procumbens), and over 300 feet tall in the case of coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens). Most prefer full sun and somewhat dry soil, and all are wind-pollinated. The leaves are typically needle-like or scale-like, with the needles in either linear or acicular shapes. Most are evergreen, but others are deciduous. When we say “evergreen” it doesn’t mean they hold their needles indefinitely, they just don’t shed them all at once like deciduous types do. Instead, they drop a few here and there that are constantly being replaced, giving the appearance of having persistent needles that last forever. Many conifers produce sap, also called resin or pitch, which is a natural protection against pathogens and pests. Many pests are put off by the fragrance of the resin, but they can also become trapped in it if they try to feed on the plant. If one of these plants is wounded, it sends resin to the area to flood out pests and pathogens that might cause infestation or infection. Some conifers want to attract birds to their cones to help spread the seeds. These will typically grow upright cones with short or non-existent stems. That allows the birds to easily perch on the branch and feed. Some Examples The pine (Pinaceae), podocarp (Podocarpaceae), and cypress (Cupressaceae) families make up the largest conifer families, but there are also the Araucariaceae, Sciadopityaceae, Cephalotaxaceae, and Taxaceae families. All the needle-laden trees like cedars, Douglas firs, true cypress, firs, junipers, kauri (Agathis), larches, pines, hemlocks, redwoods, spruces, and yews are conifers. There are deciduous types, including some larches, bald cypress (Taxodium distichum), and dawn redwoods (Metasequoia spp.). These will lose their foliage in the fall and develop new leaves in the spring. When it comes to conifers in the garden, pines, cypress, yews, and junipers are the most popular in North America. Where Do They Grow Wild? After the last ice age, many conifer species became extinct because flowering plants, which are better adapted to the warmer conditions of the modern climate, took over. But there are still a few areas where flowering plants haven’t managed to outcompete with conifers. The Pacific Northwest is one area where conifers thrive and that’s because evergreen leaves need a climate with a long, mild growing season. They also do well in areas that have little moisture in the summer and ample moisture the rest of the year. They’ve also adapted to grow in poor soil where flowering trees and shrubs fail to thrive. You mostly find conifers in colder regions in northern latitudes. The two cold-hardiest trees in the world, the Dahurian larch (Larix gmelinii) and the Siberian larch (L. sibirica) are conifers. The rarest type in the world, the Monterey cypress, comes from a tiny corner of southwest Oregon and northwest California. There are just a handful native to the Southern Hemisphere. These belong to the Araucaria, Podocarpus, and Agathis genera. Form and Reproduction Most conifers, at least in their natural form, have a conical shape with a strong central leader. This shape maximizes the light exposure available to the branches and needles. As mentioned, what sets conifers apart from flowering plants is how they reproduce. These plants have petalless flowers on inflorescences that make up the immature cones. All conifers have male cones that contain the pollen and female cones that hold the flowers and seeds. The male cones are typically soft, with scales that hold the pollen inside until it’s ready to release. Once it releases, it’s carried on the wind, water, or by animals and there can be an impressive amount. If you’ve ever stepped outside to find everything covered in yellow powder, you’re probably looking at pollen from a nearby conifer, like a pine tree (Pinus spp.). The pollen finds a female cone, which is usually soft when young, becoming woody when mature and pollinated. The scales open to allow the pollen to find the seeds inside, and they’ll often exude a bit of resin that helps the pollen stick. Then, the scales close back up to protect the pollinated seed. Some seeds are winged so they can be carried on the wind and others wait for birds or other hungry animals to eat them and carry them far and wide. If you go for a walk in a coniferous forest in the spring, you’ll likely notice the seedlings popping up all over the place. Most cones are pollinated and drop from the tree in the same year, but quite a few take two or even three years to release the seeds. You might hear some cones referred to as “fruits,” such as those on junipers and yews, but they aren’t technically fruits. They’re cones, they just have fleshy scales. Quick Guide to Identification It can be hard to tell all the various conifers apart. Although it’s a lot more complicated than this, you can generally determine which type it is based on how the needles attach to the stalk. If the needles wrap around the twig, it’s likely either a yew (Taxaceae family) or a cypress (Cupressaceae family). Needles with a round base that leave behind round scars when they fall or are torn off are true firs (Abies spp.). Soft needles in clusters of 15 or more that attach together at the base via a spur are larches (Larix spp.), while 15 or more stiff needles on a spur are true cedars (Cedrus spp.). Needles in groups of two, three, or five with a papery envelope at the base, it’ll be a pine (Pinaceae family). Scales attached to the stem are junipers (Juniperus spp.). If the needles attach via a small peg perpendicular to the stem, you’re probably looking at a spruce (Picea spp.). If there’s a tiny perpendicular stem, it’s likely a Douglas fir. Finally, if the needle has a bit of stem that grows parallel to the main stem, it’s a hemlock (subfamily Abietoideae). You can learn more in our guide to conifer identification here. Conifers Are So Cool! I really think these plants are so cool – they have some really fascinating adaptations. Wait, now as I’m reading that sentence, I’m realizing that I am officially a plant nerd. I can’t be the only certified conifer nerd. What do you like about these plants? Which are your favorites? Let us know in the comments section below! And if you love conifers as much as I do, you’ll likely want to learn more about them. Add these guides to your reading list next: © Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. !function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s) if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function()n.callMethod? n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments); if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version='2.0'; n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0; t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)(window, document,'script', ' fbq('init', '176410929431717'); fbq('track', 'PageView'); Source link

0 notes

Photo

We all know what conifers are, don’t we? They’re evergreens with needles rather than leaves. But what about larches? They’re not evergreen. And cypresses have scale-like leaves, not needles. And let’s not even talk about monkey puzzle trees! The answer to the question “what are conifers” isn’t so clear. These plants are actually defined by their method of reproduction, not their foliage. Many species are indeed evergreens with needle-like foliage, but not all. What they all have in common is that they produce reproductive cones instead of flowers. I live in one of the most conifer-dense regions in the world, and I’ve developed a deep fascination for these plants. Not only do many of them look lush and green even during the winter, but they need hardly any maintenance at all in the garden. I’m just dying to discuss even more about conifers, so without further ado, here’s what we’ll be going over: What Are Conifers? There is one characteristic that defines these plants and it’s not the presence of needles or whether or not they are evergreen. All of them bear cones with seeds inside. In fact, that’s what the word conifer means. It’s Latin for conus, meaning cone, and ferre, meaning bearing. It’s a cone-bearing plant. They all have two types of cones: females and males. The male cones are small, soft, and contain pollen. The female cones are larger, woody, and contain the seeds. In many species, the pollen is carried a short distance by the wind. Male and female cones on a mugo pine. Conifers are gymnosperms, meaning they are woody, seed-bearing plants. All of the about 650 existing species within seven genera are woody perennials that are either trees or shrubs. The vast majority have a single main trunk. They can be low-growing and under nine inches tall, like dwarf Japanese juniper (Juniperus procumbens), and over 300 feet tall in the case of coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens). Most prefer full sun and somewhat dry soil, and all are wind-pollinated. The leaves are typically needle-like or scale-like, with the needles in either linear or acicular shapes. Most are evergreen, but others are deciduous. When we say “evergreen” it doesn’t mean they hold their needles indefinitely, they just don’t shed them all at once like deciduous types do. Instead, they drop a few here and there that are constantly being replaced, giving the appearance of having persistent needles that last forever. Many conifers produce sap, also called resin or pitch, which is a natural protection against pathogens and pests. Many pests are put off by the fragrance of the resin, but they can also become trapped in it if they try to feed on the plant. If one of these plants is wounded, it sends resin to the area to flood out pests and pathogens that might cause infestation or infection. Some conifers want to attract birds to their cones to help spread the seeds. These will typically grow upright cones with short or non-existent stems. That allows the birds to easily perch on the branch and feed. Some Examples The pine (Pinaceae), podocarp (Podocarpaceae), and cypress (Cupressaceae) families make up the largest conifer families, but there are also the Araucariaceae, Sciadopityaceae, Cephalotaxaceae, and Taxaceae families. All the needle-laden trees like cedars, Douglas firs, true cypress, firs, junipers, kauri (Agathis), larches, pines, hemlocks, redwoods, spruces, and yews are conifers. There are deciduous types, including some larches, bald cypress (Taxodium distichum), and dawn redwoods (Metasequoia spp.). These will lose their foliage in the fall and develop new leaves in the spring. When it comes to conifers in the garden, pines, cypress, yews, and junipers are the most popular in North America. Where Do They Grow Wild? After the last ice age, many conifer species became extinct because flowering plants, which are better adapted to the warmer conditions of the modern climate, took over. But there are still a few areas where flowering plants haven’t managed to outcompete with conifers. The Pacific Northwest is one area where conifers thrive and that’s because evergreen leaves need a climate with a long, mild growing season. They also do well in areas that have little moisture in the summer and ample moisture the rest of the year. They’ve also adapted to grow in poor soil where flowering trees and shrubs fail to thrive. You mostly find conifers in colder regions in northern latitudes. The two cold-hardiest trees in the world, the Dahurian larch (Larix gmelinii) and the Siberian larch (L. sibirica) are conifers. The rarest type in the world, the Monterey cypress, comes from a tiny corner of southwest Oregon and northwest California. There are just a handful native to the Southern Hemisphere. These belong to the Araucaria, Podocarpus, and Agathis genera. Form and Reproduction Most conifers, at least in their natural form, have a conical shape with a strong central leader. This shape maximizes the light exposure available to the branches and needles. As mentioned, what sets conifers apart from flowering plants is how they reproduce. These plants have petalless flowers on inflorescences that make up the immature cones. All conifers have male cones that contain the pollen and female cones that hold the flowers and seeds. The male cones are typically soft, with scales that hold the pollen inside until it’s ready to release. Once it releases, it’s carried on the wind, water, or by animals and there can be an impressive amount. If you’ve ever stepped outside to find everything covered in yellow powder, you’re probably looking at pollen from a nearby conifer, like a pine tree (Pinus spp.). The pollen finds a female cone, which is usually soft when young, becoming woody when mature and pollinated. The scales open to allow the pollen to find the seeds inside, and they’ll often exude a bit of resin that helps the pollen stick. Then, the scales close back up to protect the pollinated seed. Some seeds are winged so they can be carried on the wind and others wait for birds or other hungry animals to eat them and carry them far and wide. If you go for a walk in a coniferous forest in the spring, you’ll likely notice the seedlings popping up all over the place. Most cones are pollinated and drop from the tree in the same year, but quite a few take two or even three years to release the seeds. You might hear some cones referred to as “fruits,” such as those on junipers and yews, but they aren’t technically fruits. They’re cones, they just have fleshy scales. Quick Guide to Identification It can be hard to tell all the various conifers apart. Although it’s a lot more complicated than this, you can generally determine which type it is based on how the needles attach to the stalk. If the needles wrap around the twig, it’s likely either a yew (Taxaceae family) or a cypress (Cupressaceae family). Needles with a round base that leave behind round scars when they fall or are torn off are true firs (Abies spp.). Soft needles in clusters of 15 or more that attach together at the base via a spur are larches (Larix spp.), while 15 or more stiff needles on a spur are true cedars (Cedrus spp.). Needles in groups of two, three, or five with a papery envelope at the base, it’ll be a pine (Pinaceae family). Scales attached to the stem are junipers (Juniperus spp.). If the needles attach via a small peg perpendicular to the stem, you’re probably looking at a spruce (Picea spp.). If there’s a tiny perpendicular stem, it’s likely a Douglas fir. Finally, if the needle has a bit of stem that grows parallel to the main stem, it’s a hemlock (subfamily Abietoideae). You can learn more in our guide to conifer identification here. Conifers Are So Cool! I really think these plants are so cool – they have some really fascinating adaptations. Wait, now as I’m reading that sentence, I’m realizing that I am officially a plant nerd. I can’t be the only certified conifer nerd. What do you like about these plants? Which are your favorites? Let us know in the comments section below! And if you love conifers as much as I do, you’ll likely want to learn more about them. Add these guides to your reading list next: © Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. !function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s) if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function()n.callMethod? n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments); if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version='2.0'; n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0; t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)(window, document,'script', ' fbq('init', '176410929431717'); fbq('track', 'PageView'); Source link

0 notes

Photo

We all know what conifers are, don’t we? They’re evergreens with needles rather than leaves. But what about larches? They’re not evergreen. And cypresses have scale-like leaves, not needles. And let’s not even talk about monkey puzzle trees! The answer to the question “what are conifers” isn’t so clear. These plants are actually defined by their method of reproduction, not their foliage. Many species are indeed evergreens with needle-like foliage, but not all. What they all have in common is that they produce reproductive cones instead of flowers. I live in one of the most conifer-dense regions in the world, and I’ve developed a deep fascination for these plants. Not only do many of them look lush and green even during the winter, but they need hardly any maintenance at all in the garden. I’m just dying to discuss even more about conifers, so without further ado, here’s what we’ll be going over: What Are Conifers? There is one characteristic that defines these plants and it’s not the presence of needles or whether or not they are evergreen. All of them bear cones with seeds inside. In fact, that’s what the word conifer means. It’s Latin for conus, meaning cone, and ferre, meaning bearing. It’s a cone-bearing plant. They all have two types of cones: females and males. The male cones are small, soft, and contain pollen. The female cones are larger, woody, and contain the seeds. In many species, the pollen is carried a short distance by the wind. Male and female cones on a mugo pine. Conifers are gymnosperms, meaning they are woody, seed-bearing plants. All of the about 650 existing species within seven genera are woody perennials that are either trees or shrubs. The vast majority have a single main trunk. They can be low-growing and under nine inches tall, like dwarf Japanese juniper (Juniperus procumbens), and over 300 feet tall in the case of coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens). Most prefer full sun and somewhat dry soil, and all are wind-pollinated. The leaves are typically needle-like or scale-like, with the needles in either linear or acicular shapes. Most are evergreen, but others are deciduous. When we say “evergreen” it doesn’t mean they hold their needles indefinitely, they just don’t shed them all at once like deciduous types do. Instead, they drop a few here and there that are constantly being replaced, giving the appearance of having persistent needles that last forever. Many conifers produce sap, also called resin or pitch, which is a natural protection against pathogens and pests. Many pests are put off by the fragrance of the resin, but they can also become trapped in it if they try to feed on the plant. If one of these plants is wounded, it sends resin to the area to flood out pests and pathogens that might cause infestation or infection. Some conifers want to attract birds to their cones to help spread the seeds. These will typically grow upright cones with short or non-existent stems. That allows the birds to easily perch on the branch and feed. Some Examples The pine (Pinaceae), podocarp (Podocarpaceae), and cypress (Cupressaceae) families make up the largest conifer families, but there are also the Araucariaceae, Sciadopityaceae, Cephalotaxaceae, and Taxaceae families. All the needle-laden trees like cedars, Douglas firs, true cypress, firs, junipers, kauri (Agathis), larches, pines, hemlocks, redwoods, spruces, and yews are conifers. There are deciduous types, including some larches, bald cypress (Taxodium distichum), and dawn redwoods (Metasequoia spp.). These will lose their foliage in the fall and develop new leaves in the spring. When it comes to conifers in the garden, pines, cypress, yews, and junipers are the most popular in North America. Where Do They Grow Wild? After the last ice age, many conifer species became extinct because flowering plants, which are better adapted to the warmer conditions of the modern climate, took over. But there are still a few areas where flowering plants haven’t managed to outcompete with conifers. The Pacific Northwest is one area where conifers thrive and that’s because evergreen leaves need a climate with a long, mild growing season. They also do well in areas that have little moisture in the summer and ample moisture the rest of the year. They’ve also adapted to grow in poor soil where flowering trees and shrubs fail to thrive. You mostly find conifers in colder regions in northern latitudes. The two cold-hardiest trees in the world, the Dahurian larch (Larix gmelinii) and the Siberian larch (L. sibirica) are conifers. The rarest type in the world, the Monterey cypress, comes from a tiny corner of southwest Oregon and northwest California. There are just a handful native to the Southern Hemisphere. These belong to the Araucaria, Podocarpus, and Agathis genera. Form and Reproduction Most conifers, at least in their natural form, have a conical shape with a strong central leader. This shape maximizes the light exposure available to the branches and needles. As mentioned, what sets conifers apart from flowering plants is how they reproduce. These plants have petalless flowers on inflorescences that make up the immature cones. All conifers have male cones that contain the pollen and female cones that hold the flowers and seeds. The male cones are typically soft, with scales that hold the pollen inside until it’s ready to release. Once it releases, it’s carried on the wind, water, or by animals and there can be an impressive amount. If you’ve ever stepped outside to find everything covered in yellow powder, you’re probably looking at pollen from a nearby conifer, like a pine tree (Pinus spp.). The pollen finds a female cone, which is usually soft when young, becoming woody when mature and pollinated. The scales open to allow the pollen to find the seeds inside, and they’ll often exude a bit of resin that helps the pollen stick. Then, the scales close back up to protect the pollinated seed. Some seeds are winged so they can be carried on the wind and others wait for birds or other hungry animals to eat them and carry them far and wide. If you go for a walk in a coniferous forest in the spring, you’ll likely notice the seedlings popping up all over the place. Most cones are pollinated and drop from the tree in the same year, but quite a few take two or even three years to release the seeds. You might hear some cones referred to as “fruits,” such as those on junipers and yews, but they aren’t technically fruits. They’re cones, they just have fleshy scales. Quick Guide to Identification It can be hard to tell all the various conifers apart. Although it’s a lot more complicated than this, you can generally determine which type it is based on how the needles attach to the stalk. If the needles wrap around the twig, it’s likely either a yew (Taxaceae family) or a cypress (Cupressaceae family). Needles with a round base that leave behind round scars when they fall or are torn off are true firs (Abies spp.). Soft needles in clusters of 15 or more that attach together at the base via a spur are larches (Larix spp.), while 15 or more stiff needles on a spur are true cedars (Cedrus spp.). Needles in groups of two, three, or five with a papery envelope at the base, it’ll be a pine (Pinaceae family). Scales attached to the stem are junipers (Juniperus spp.). If the needles attach via a small peg perpendicular to the stem, you’re probably looking at a spruce (Picea spp.). If there’s a tiny perpendicular stem, it’s likely a Douglas fir. Finally, if the needle has a bit of stem that grows parallel to the main stem, it’s a hemlock (subfamily Abietoideae). You can learn more in our guide to conifer identification here. Conifers Are So Cool! I really think these plants are so cool – they have some really fascinating adaptations. Wait, now as I’m reading that sentence, I’m realizing that I am officially a plant nerd. I can’t be the only certified conifer nerd. What do you like about these plants? Which are your favorites? Let us know in the comments section below! And if you love conifers as much as I do, you’ll likely want to learn more about them. Add these guides to your reading list next: © Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. !function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s) if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function()n.callMethod? n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments); if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version='2.0'; n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0; t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)(window, document,'script', ' fbq('init', '176410929431717'); fbq('track', 'PageView'); Source link

0 notes

Photo

We all know what conifers are, don’t we? They’re evergreens with needles rather than leaves. But what about larches? They’re not evergreen. And cypresses have scale-like leaves, not needles. And let’s not even talk about monkey puzzle trees! The answer to the question “what are conifers” isn’t so clear. These plants are actually defined by their method of reproduction, not their foliage. Many species are indeed evergreens with needle-like foliage, but not all. What they all have in common is that they produce reproductive cones instead of flowers. I live in one of the most conifer-dense regions in the world, and I’ve developed a deep fascination for these plants. Not only do many of them look lush and green even during the winter, but they need hardly any maintenance at all in the garden. I’m just dying to discuss even more about conifers, so without further ado, here’s what we’ll be going over: What Are Conifers? There is one characteristic that defines these plants and it’s not the presence of needles or whether or not they are evergreen. All of them bear cones with seeds inside. In fact, that’s what the word conifer means. It’s Latin for conus, meaning cone, and ferre, meaning bearing. It’s a cone-bearing plant. They all have two types of cones: females and males. The male cones are small, soft, and contain pollen. The female cones are larger, woody, and contain the seeds. In many species, the pollen is carried a short distance by the wind. Male and female cones on a mugo pine. Conifers are gymnosperms, meaning they are woody, seed-bearing plants. All of the about 650 existing species within seven genera are woody perennials that are either trees or shrubs. The vast majority have a single main trunk. They can be low-growing and under nine inches tall, like dwarf Japanese juniper (Juniperus procumbens), and over 300 feet tall in the case of coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens). Most prefer full sun and somewhat dry soil, and all are wind-pollinated. The leaves are typically needle-like or scale-like, with the needles in either linear or acicular shapes. Most are evergreen, but others are deciduous. When we say “evergreen” it doesn’t mean they hold their needles indefinitely, they just don’t shed them all at once like deciduous types do. Instead, they drop a few here and there that are constantly being replaced, giving the appearance of having persistent needles that last forever. Many conifers produce sap, also called resin or pitch, which is a natural protection against pathogens and pests. Many pests are put off by the fragrance of the resin, but they can also become trapped in it if they try to feed on the plant. If one of these plants is wounded, it sends resin to the area to flood out pests and pathogens that might cause infestation or infection. Some conifers want to attract birds to their cones to help spread the seeds. These will typically grow upright cones with short or non-existent stems. That allows the birds to easily perch on the branch and feed. Some Examples The pine (Pinaceae), podocarp (Podocarpaceae), and cypress (Cupressaceae) families make up the largest conifer families, but there are also the Araucariaceae, Sciadopityaceae, Cephalotaxaceae, and Taxaceae families. All the needle-laden trees like cedars, Douglas firs, true cypress, firs, junipers, kauri (Agathis), larches, pines, hemlocks, redwoods, spruces, and yews are conifers. There are deciduous types, including some larches, bald cypress (Taxodium distichum), and dawn redwoods (Metasequoia spp.). These will lose their foliage in the fall and develop new leaves in the spring. When it comes to conifers in the garden, pines, cypress, yews, and junipers are the most popular in North America. Where Do They Grow Wild? After the last ice age, many conifer species became extinct because flowering plants, which are better adapted to the warmer conditions of the modern climate, took over. But there are still a few areas where flowering plants haven’t managed to outcompete with conifers. The Pacific Northwest is one area where conifers thrive and that’s because evergreen leaves need a climate with a long, mild growing season. They also do well in areas that have little moisture in the summer and ample moisture the rest of the year. They’ve also adapted to grow in poor soil where flowering trees and shrubs fail to thrive. You mostly find conifers in colder regions in northern latitudes. The two cold-hardiest trees in the world, the Dahurian larch (Larix gmelinii) and the Siberian larch (L. sibirica) are conifers. The rarest type in the world, the Monterey cypress, comes from a tiny corner of southwest Oregon and northwest California. There are just a handful native to the Southern Hemisphere. These belong to the Araucaria, Podocarpus, and Agathis genera. Form and Reproduction Most conifers, at least in their natural form, have a conical shape with a strong central leader. This shape maximizes the light exposure available to the branches and needles. As mentioned, what sets conifers apart from flowering plants is how they reproduce. These plants have petalless flowers on inflorescences that make up the immature cones. All conifers have male cones that contain the pollen and female cones that hold the flowers and seeds. The male cones are typically soft, with scales that hold the pollen inside until it’s ready to release. Once it releases, it’s carried on the wind, water, or by animals and there can be an impressive amount. If you’ve ever stepped outside to find everything covered in yellow powder, you’re probably looking at pollen from a nearby conifer, like a pine tree (Pinus spp.). The pollen finds a female cone, which is usually soft when young, becoming woody when mature and pollinated. The scales open to allow the pollen to find the seeds inside, and they’ll often exude a bit of resin that helps the pollen stick. Then, the scales close back up to protect the pollinated seed. Some seeds are winged so they can be carried on the wind and others wait for birds or other hungry animals to eat them and carry them far and wide. If you go for a walk in a coniferous forest in the spring, you’ll likely notice the seedlings popping up all over the place. Most cones are pollinated and drop from the tree in the same year, but quite a few take two or even three years to release the seeds. You might hear some cones referred to as “fruits,” such as those on junipers and yews, but they aren’t technically fruits. They’re cones, they just have fleshy scales. Quick Guide to Identification It can be hard to tell all the various conifers apart. Although it’s a lot more complicated than this, you can generally determine which type it is based on how the needles attach to the stalk. If the needles wrap around the twig, it’s likely either a yew (Taxaceae family) or a cypress (Cupressaceae family). Needles with a round base that leave behind round scars when they fall or are torn off are true firs (Abies spp.). Soft needles in clusters of 15 or more that attach together at the base via a spur are larches (Larix spp.), while 15 or more stiff needles on a spur are true cedars (Cedrus spp.). Needles in groups of two, three, or five with a papery envelope at the base, it’ll be a pine (Pinaceae family). Scales attached to the stem are junipers (Juniperus spp.). If the needles attach via a small peg perpendicular to the stem, you’re probably looking at a spruce (Picea spp.). If there’s a tiny perpendicular stem, it’s likely a Douglas fir. Finally, if the needle has a bit of stem that grows parallel to the main stem, it’s a hemlock (subfamily Abietoideae). You can learn more in our guide to conifer identification here. Conifers Are So Cool! I really think these plants are so cool – they have some really fascinating adaptations. Wait, now as I’m reading that sentence, I’m realizing that I am officially a plant nerd. I can’t be the only certified conifer nerd. What do you like about these plants? Which are your favorites? Let us know in the comments section below! And if you love conifers as much as I do, you’ll likely want to learn more about them. Add these guides to your reading list next: © Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. !function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s) if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function()n.callMethod? n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments); if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version='2.0'; n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0; t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)(window, document,'script', ' fbq('init', '176410929431717'); fbq('track', 'PageView'); Source link

0 notes

Photo

We all know what conifers are, don’t we? They’re evergreens with needles rather than leaves. But what about larches? They’re not evergreen. And cypresses have scale-like leaves, not needles. And let’s not even talk about monkey puzzle trees! The answer to the question “what are conifers” isn’t so clear. These plants are actually defined by their method of reproduction, not their foliage. Many species are indeed evergreens with needle-like foliage, but not all. What they all have in common is that they produce reproductive cones instead of flowers. I live in one of the most conifer-dense regions in the world, and I’ve developed a deep fascination for these plants. Not only do many of them look lush and green even during the winter, but they need hardly any maintenance at all in the garden. I’m just dying to discuss even more about conifers, so without further ado, here’s what we’ll be going over: What Are Conifers? There is one characteristic that defines these plants and it’s not the presence of needles or whether or not they are evergreen. All of them bear cones with seeds inside. In fact, that’s what the word conifer means. It’s Latin for conus, meaning cone, and ferre, meaning bearing. It’s a cone-bearing plant. They all have two types of cones: females and males. The male cones are small, soft, and contain pollen. The female cones are larger, woody, and contain the seeds. In many species, the pollen is carried a short distance by the wind. Male and female cones on a mugo pine. Conifers are gymnosperms, meaning they are woody, seed-bearing plants. All of the about 650 existing species within seven genera are woody perennials that are either trees or shrubs. The vast majority have a single main trunk. They can be low-growing and under nine inches tall, like dwarf Japanese juniper (Juniperus procumbens), and over 300 feet tall in the case of coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens). Most prefer full sun and somewhat dry soil, and all are wind-pollinated. The leaves are typically needle-like or scale-like, with the needles in either linear or acicular shapes. Most are evergreen, but others are deciduous. When we say “evergreen” it doesn’t mean they hold their needles indefinitely, they just don’t shed them all at once like deciduous types do. Instead, they drop a few here and there that are constantly being replaced, giving the appearance of having persistent needles that last forever. Many conifers produce sap, also called resin or pitch, which is a natural protection against pathogens and pests. Many pests are put off by the fragrance of the resin, but they can also become trapped in it if they try to feed on the plant. If one of these plants is wounded, it sends resin to the area to flood out pests and pathogens that might cause infestation or infection. Some conifers want to attract birds to their cones to help spread the seeds. These will typically grow upright cones with short or non-existent stems. That allows the birds to easily perch on the branch and feed. Some Examples The pine (Pinaceae), podocarp (Podocarpaceae), and cypress (Cupressaceae) families make up the largest conifer families, but there are also the Araucariaceae, Sciadopityaceae, Cephalotaxaceae, and Taxaceae families. All the needle-laden trees like cedars, Douglas firs, true cypress, firs, junipers, kauri (Agathis), larches, pines, hemlocks, redwoods, spruces, and yews are conifers. There are deciduous types, including some larches, bald cypress (Taxodium distichum), and dawn redwoods (Metasequoia spp.). These will lose their foliage in the fall and develop new leaves in the spring. When it comes to conifers in the garden, pines, cypress, yews, and junipers are the most popular in North America. Where Do They Grow Wild? After the last ice age, many conifer species became extinct because flowering plants, which are better adapted to the warmer conditions of the modern climate, took over. But there are still a few areas where flowering plants haven’t managed to outcompete with conifers. The Pacific Northwest is one area where conifers thrive and that’s because evergreen leaves need a climate with a long, mild growing season. They also do well in areas that have little moisture in the summer and ample moisture the rest of the year. They’ve also adapted to grow in poor soil where flowering trees and shrubs fail to thrive. You mostly find conifers in colder regions in northern latitudes. The two cold-hardiest trees in the world, the Dahurian larch (Larix gmelinii) and the Siberian larch (L. sibirica) are conifers. The rarest type in the world, the Monterey cypress, comes from a tiny corner of southwest Oregon and northwest California. There are just a handful native to the Southern Hemisphere. These belong to the Araucaria, Podocarpus, and Agathis genera. Form and Reproduction Most conifers, at least in their natural form, have a conical shape with a strong central leader. This shape maximizes the light exposure available to the branches and needles. As mentioned, what sets conifers apart from flowering plants is how they reproduce. These plants have petalless flowers on inflorescences that make up the immature cones. All conifers have male cones that contain the pollen and female cones that hold the flowers and seeds. The male cones are typically soft, with scales that hold the pollen inside until it’s ready to release. Once it releases, it’s carried on the wind, water, or by animals and there can be an impressive amount. If you’ve ever stepped outside to find everything covered in yellow powder, you’re probably looking at pollen from a nearby conifer, like a pine tree (Pinus spp.). The pollen finds a female cone, which is usually soft when young, becoming woody when mature and pollinated. The scales open to allow the pollen to find the seeds inside, and they’ll often exude a bit of resin that helps the pollen stick. Then, the scales close back up to protect the pollinated seed. Some seeds are winged so they can be carried on the wind and others wait for birds or other hungry animals to eat them and carry them far and wide. If you go for a walk in a coniferous forest in the spring, you’ll likely notice the seedlings popping up all over the place. Most cones are pollinated and drop from the tree in the same year, but quite a few take two or even three years to release the seeds. You might hear some cones referred to as “fruits,” such as those on junipers and yews, but they aren’t technically fruits. They’re cones, they just have fleshy scales. Quick Guide to Identification It can be hard to tell all the various conifers apart. Although it’s a lot more complicated than this, you can generally determine which type it is based on how the needles attach to the stalk. If the needles wrap around the twig, it’s likely either a yew (Taxaceae family) or a cypress (Cupressaceae family). Needles with a round base that leave behind round scars when they fall or are torn off are true firs (Abies spp.). Soft needles in clusters of 15 or more that attach together at the base via a spur are larches (Larix spp.), while 15 or more stiff needles on a spur are true cedars (Cedrus spp.). Needles in groups of two, three, or five with a papery envelope at the base, it’ll be a pine (Pinaceae family). Scales attached to the stem are junipers (Juniperus spp.). If the needles attach via a small peg perpendicular to the stem, you’re probably looking at a spruce (Picea spp.). If there’s a tiny perpendicular stem, it’s likely a Douglas fir. Finally, if the needle has a bit of stem that grows parallel to the main stem, it’s a hemlock (subfamily Abietoideae). You can learn more in our guide to conifer identification here. Conifers Are So Cool! I really think these plants are so cool – they have some really fascinating adaptations. Wait, now as I’m reading that sentence, I’m realizing that I am officially a plant nerd. I can’t be the only certified conifer nerd. What do you like about these plants? Which are your favorites? Let us know in the comments section below! And if you love conifers as much as I do, you’ll likely want to learn more about them. Add these guides to your reading list next: © Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. !function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s) if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function()n.callMethod? n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments); if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version='2.0'; n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0; t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)(window, document,'script', ' fbq('init', '176410929431717'); fbq('track', 'PageView'); Source link

0 notes

Text

#2405 - Pectinopitys ferruginea - Miro

AKA Prumnopitys ferruginea, and originally Podocarpus ferrugineus. 'ferruginea' derives from the rusty colour of dried herbarium specimens. Miro comes from the Proto-Polynesian word milo - the Pacific rosewood (Thespesia populnea) found on tropical islands far to the north.

A podocarp endemic to New Zealand, growing in lowland terrain and on hill slopes throughout the two main islands and on Stewart Island.

It can live to about 600 years in age, and 25m in height, with a trunk up to 1.3 m diameter. Like other podocarps, the fruit is fleshy and berrylike, and spread by birds such as the New Zealand Pigeon.

Lake Mangamahoe, Taranaki Ringplain, New Zealand

#Pectinopitys#Prumnopitys#miro#podocarp#new zealand tree#podocarpaceae#lake mangamahoe#taranaki ringplain

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

We all know what conifers are, don’t we? They’re evergreens with needles rather than leaves. But what about larches? They’re not evergreen. And cypresses have scale-like leaves, not needles. And let’s not even talk about monkey puzzle trees! The answer to the question “what are conifers” isn’t so clear. These plants are actually defined by their method of reproduction, not their foliage. Many species are indeed evergreens with needle-like foliage, but not all. What they all have in common is that they produce reproductive cones instead of flowers. I live in one of the most conifer-dense regions in the world, and I’ve developed a deep fascination for these plants. Not only do many of them look lush and green even during the winter, but they need hardly any maintenance at all in the garden. I’m just dying to discuss even more about conifers, so without further ado, here’s what we’ll be going over: What Are Conifers? There is one characteristic that defines these plants and it’s not the presence of needles or whether or not they are evergreen. All of them bear cones with seeds inside. In fact, that’s what the word conifer means. It’s Latin for conus, meaning cone, and ferre, meaning bearing. It’s a cone-bearing plant. They all have two types of cones: females and males. The male cones are small, soft, and contain pollen. The female cones are larger, woody, and contain the seeds. In many species, the pollen is carried a short distance by the wind. Male and female cones on a mugo pine. Conifers are gymnosperms, meaning they are woody, seed-bearing plants. All of the about 650 existing species within seven genera are woody perennials that are either trees or shrubs. The vast majority have a single main trunk. They can be low-growing and under nine inches tall, like dwarf Japanese juniper (Juniperus procumbens), and over 300 feet tall in the case of coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens). Most prefer full sun and somewhat dry soil, and all are wind-pollinated. The leaves are typically needle-like or scale-like, with the needles in either linear or acicular shapes. Most are evergreen, but others are deciduous. When we say “evergreen” it doesn’t mean they hold their needles indefinitely, they just don’t shed them all at once like deciduous types do. Instead, they drop a few here and there that are constantly being replaced, giving the appearance of having persistent needles that last forever. Many conifers produce sap, also called resin or pitch, which is a natural protection against pathogens and pests. Many pests are put off by the fragrance of the resin, but they can also become trapped in it if they try to feed on the plant. If one of these plants is wounded, it sends resin to the area to flood out pests and pathogens that might cause infestation or infection. Some conifers want to attract birds to their cones to help spread the seeds. These will typically grow upright cones with short or non-existent stems. That allows the birds to easily perch on the branch and feed. Some Examples The pine (Pinaceae), podocarp (Podocarpaceae), and cypress (Cupressaceae) families make up the largest conifer families, but there are also the Araucariaceae, Sciadopityaceae, Cephalotaxaceae, and Taxaceae families. All the needle-laden trees like cedars, Douglas firs, true cypress, firs, junipers, kauri (Agathis), larches, pines, hemlocks, redwoods, spruces, and yews are conifers. There are deciduous types, including some larches, bald cypress (Taxodium distichum), and dawn redwoods (Metasequoia spp.). These will lose their foliage in the fall and develop new leaves in the spring. When it comes to conifers in the garden, pines, cypress, yews, and junipers are the most popular in North America. Where Do They Grow Wild? After the last ice age, many conifer species became extinct because flowering plants, which are better adapted to the warmer conditions of the modern climate, took over. But there are still a few areas where flowering plants haven’t managed to outcompete with conifers. The Pacific Northwest is one area where conifers thrive and that’s because evergreen leaves need a climate with a long, mild growing season. They also do well in areas that have little moisture in the summer and ample moisture the rest of the year. They’ve also adapted to grow in poor soil where flowering trees and shrubs fail to thrive. You mostly find conifers in colder regions in northern latitudes. The two cold-hardiest trees in the world, the Dahurian larch (Larix gmelinii) and the Siberian larch (L. sibirica) are conifers. The rarest type in the world, the Monterey cypress, comes from a tiny corner of southwest Oregon and northwest California. There are just a handful native to the Southern Hemisphere. These belong to the Araucaria, Podocarpus, and Agathis genera. Form and Reproduction Most conifers, at least in their natural form, have a conical shape with a strong central leader. This shape maximizes the light exposure available to the branches and needles. As mentioned, what sets conifers apart from flowering plants is how they reproduce. These plants have petalless flowers on inflorescences that make up the immature cones. All conifers have male cones that contain the pollen and female cones that hold the flowers and seeds. The male cones are typically soft, with scales that hold the pollen inside until it’s ready to release. Once it releases, it’s carried on the wind, water, or by animals and there can be an impressive amount. If you’ve ever stepped outside to find everything covered in yellow powder, you’re probably looking at pollen from a nearby conifer, like a pine tree (Pinus spp.). The pollen finds a female cone, which is usually soft when young, becoming woody when mature and pollinated. The scales open to allow the pollen to find the seeds inside, and they’ll often exude a bit of resin that helps the pollen stick. Then, the scales close back up to protect the pollinated seed. Some seeds are winged so they can be carried on the wind and others wait for birds or other hungry animals to eat them and carry them far and wide. If you go for a walk in a coniferous forest in the spring, you’ll likely notice the seedlings popping up all over the place. Most cones are pollinated and drop from the tree in the same year, but quite a few take two or even three years to release the seeds. You might hear some cones referred to as “fruits,” such as those on junipers and yews, but they aren’t technically fruits. They’re cones, they just have fleshy scales. Quick Guide to Identification It can be hard to tell all the various conifers apart. Although it’s a lot more complicated than this, you can generally determine which type it is based on how the needles attach to the stalk. If the needles wrap around the twig, it’s likely either a yew (Taxaceae family) or a cypress (Cupressaceae family). Needles with a round base that leave behind round scars when they fall or are torn off are true firs (Abies spp.). Soft needles in clusters of 15 or more that attach together at the base via a spur are larches (Larix spp.), while 15 or more stiff needles on a spur are true cedars (Cedrus spp.). Needles in groups of two, three, or five with a papery envelope at the base, it’ll be a pine (Pinaceae family). Scales attached to the stem are junipers (Juniperus spp.). If the needles attach via a small peg perpendicular to the stem, you’re probably looking at a spruce (Picea spp.). If there’s a tiny perpendicular stem, it’s likely a Douglas fir. Finally, if the needle has a bit of stem that grows parallel to the main stem, it’s a hemlock (subfamily Abietoideae). You can learn more in our guide to conifer identification here. Conifers Are So Cool! I really think these plants are so cool – they have some really fascinating adaptations. Wait, now as I’m reading that sentence, I’m realizing that I am officially a plant nerd. I can’t be the only certified conifer nerd. What do you like about these plants? Which are your favorites? Let us know in the comments section below! And if you love conifers as much as I do, you’ll likely want to learn more about them. Add these guides to your reading list next: © Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. !function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s) if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function()n.callMethod? n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments); if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version='2.0'; n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0; t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)(window, document,'script', ' fbq('init', '176410929431717'); fbq('track', 'PageView'); Source link

0 notes

Photo

We all know what conifers are, don’t we? They’re evergreens with needles rather than leaves. But what about larches? They’re not evergreen. And cypresses have scale-like leaves, not needles. And let’s not even talk about monkey puzzle trees! The answer to the question “what are conifers” isn’t so clear. These plants are actually defined by their method of reproduction, not their foliage. Many species are indeed evergreens with needle-like foliage, but not all. What they all have in common is that they produce reproductive cones instead of flowers. I live in one of the most conifer-dense regions in the world, and I’ve developed a deep fascination for these plants. Not only do many of them look lush and green even during the winter, but they need hardly any maintenance at all in the garden. I’m just dying to discuss even more about conifers, so without further ado, here’s what we’ll be going over: What Are Conifers? There is one characteristic that defines these plants and it’s not the presence of needles or whether or not they are evergreen. All of them bear cones with seeds inside. In fact, that’s what the word conifer means. It’s Latin for conus, meaning cone, and ferre, meaning bearing. It’s a cone-bearing plant. They all have two types of cones: females and males. The male cones are small, soft, and contain pollen. The female cones are larger, woody, and contain the seeds. In many species, the pollen is carried a short distance by the wind. Male and female cones on a mugo pine. Conifers are gymnosperms, meaning they are woody, seed-bearing plants. All of the about 650 existing species within seven genera are woody perennials that are either trees or shrubs. The vast majority have a single main trunk. They can be low-growing and under nine inches tall, like dwarf Japanese juniper (Juniperus procumbens), and over 300 feet tall in the case of coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens). Most prefer full sun and somewhat dry soil, and all are wind-pollinated. The leaves are typically needle-like or scale-like, with the needles in either linear or acicular shapes. Most are evergreen, but others are deciduous. When we say “evergreen” it doesn’t mean they hold their needles indefinitely, they just don’t shed them all at once like deciduous types do. Instead, they drop a few here and there that are constantly being replaced, giving the appearance of having persistent needles that last forever. Many conifers produce sap, also called resin or pitch, which is a natural protection against pathogens and pests. Many pests are put off by the fragrance of the resin, but they can also become trapped in it if they try to feed on the plant. If one of these plants is wounded, it sends resin to the area to flood out pests and pathogens that might cause infestation or infection. Some conifers want to attract birds to their cones to help spread the seeds. These will typically grow upright cones with short or non-existent stems. That allows the birds to easily perch on the branch and feed. Some Examples The pine (Pinaceae), podocarp (Podocarpaceae), and cypress (Cupressaceae) families make up the largest conifer families, but there are also the Araucariaceae, Sciadopityaceae, Cephalotaxaceae, and Taxaceae families. All the needle-laden trees like cedars, Douglas firs, true cypress, firs, junipers, kauri (Agathis), larches, pines, hemlocks, redwoods, spruces, and yews are conifers. There are deciduous types, including some larches, bald cypress (Taxodium distichum), and dawn redwoods (Metasequoia spp.). These will lose their foliage in the fall and develop new leaves in the spring. When it comes to conifers in the garden, pines, cypress, yews, and junipers are the most popular in North America. Where Do They Grow Wild? After the last ice age, many conifer species became extinct because flowering plants, which are better adapted to the warmer conditions of the modern climate, took over. But there are still a few areas where flowering plants haven’t managed to outcompete with conifers. The Pacific Northwest is one area where conifers thrive and that’s because evergreen leaves need a climate with a long, mild growing season. They also do well in areas that have little moisture in the summer and ample moisture the rest of the year. They’ve also adapted to grow in poor soil where flowering trees and shrubs fail to thrive. You mostly find conifers in colder regions in northern latitudes. The two cold-hardiest trees in the world, the Dahurian larch (Larix gmelinii) and the Siberian larch (L. sibirica) are conifers. The rarest type in the world, the Monterey cypress, comes from a tiny corner of southwest Oregon and northwest California. There are just a handful native to the Southern Hemisphere. These belong to the Araucaria, Podocarpus, and Agathis genera. Form and Reproduction Most conifers, at least in their natural form, have a conical shape with a strong central leader. This shape maximizes the light exposure available to the branches and needles. As mentioned, what sets conifers apart from flowering plants is how they reproduce. These plants have petalless flowers on inflorescences that make up the immature cones. All conifers have male cones that contain the pollen and female cones that hold the flowers and seeds. The male cones are typically soft, with scales that hold the pollen inside until it’s ready to release. Once it releases, it’s carried on the wind, water, or by animals and there can be an impressive amount. If you’ve ever stepped outside to find everything covered in yellow powder, you’re probably looking at pollen from a nearby conifer, like a pine tree (Pinus spp.). The pollen finds a female cone, which is usually soft when young, becoming woody when mature and pollinated. The scales open to allow the pollen to find the seeds inside, and they’ll often exude a bit of resin that helps the pollen stick. Then, the scales close back up to protect the pollinated seed. Some seeds are winged so they can be carried on the wind and others wait for birds or other hungry animals to eat them and carry them far and wide. If you go for a walk in a coniferous forest in the spring, you’ll likely notice the seedlings popping up all over the place. Most cones are pollinated and drop from the tree in the same year, but quite a few take two or even three years to release the seeds. You might hear some cones referred to as “fruits,” such as those on junipers and yews, but they aren’t technically fruits. They’re cones, they just have fleshy scales. Quick Guide to Identification It can be hard to tell all the various conifers apart. Although it’s a lot more complicated than this, you can generally determine which type it is based on how the needles attach to the stalk. If the needles wrap around the twig, it’s likely either a yew (Taxaceae family) or a cypress (Cupressaceae family). Needles with a round base that leave behind round scars when they fall or are torn off are true firs (Abies spp.). Soft needles in clusters of 15 or more that attach together at the base via a spur are larches (Larix spp.), while 15 or more stiff needles on a spur are true cedars (Cedrus spp.). Needles in groups of two, three, or five with a papery envelope at the base, it’ll be a pine (Pinaceae family). Scales attached to the stem are junipers (Juniperus spp.). If the needles attach via a small peg perpendicular to the stem, you’re probably looking at a spruce (Picea spp.). If there’s a tiny perpendicular stem, it’s likely a Douglas fir. Finally, if the needle has a bit of stem that grows parallel to the main stem, it’s a hemlock (subfamily Abietoideae). You can learn more in our guide to conifer identification here. Conifers Are So Cool! I really think these plants are so cool – they have some really fascinating adaptations. Wait, now as I’m reading that sentence, I’m realizing that I am officially a plant nerd. I can’t be the only certified conifer nerd. What do you like about these plants? Which are your favorites? Let us know in the comments section below! And if you love conifers as much as I do, you’ll likely want to learn more about them. Add these guides to your reading list next: © Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. !function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s) if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function()n.callMethod? n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments); if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version='2.0'; n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0; t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)(window, document,'script', ' fbq('init', '176410929431717'); fbq('track', 'PageView'); Source link

0 notes

Photo