#pierre blanchard

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

La Symphonie Catastrophique - Emmanuel Booz

Features violinist Pierre Blanchard. Wild Zappa-esque symphonic prog.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Review: Three Revolutionary Films by Ousmane Sembène on Criterion Blu-ray

Together, these films constitute a complex, interlocking portrait of Senegal’s past and present.

by Derek Smith May 30, 2024

Where Ousmane Sembène’s first two films, 1966’s Black Girl and 1968’s Mandabi, each focus on myriad struggles faced by an individual during Senegal’s early post-colonial years, his follow-up, Emitai, takes a more expansive view of the effects of colonialism two decades earlier. Centering on the defiance of a Diola tribe during World War II, 1971’s Emitai sacrifices none of the immediacy and urgency of Black Girl and Mandabi. Indeed, the film is perhaps an even more damning and incisive take-down of French colonial rule.

Painting a concise and pointed portrait of oppression in broad, revolutionary strokes, Emitai exposes the modern form of slavery that was France’s conscription of Senegalese men to fight on the deadliest frontlines of European battlegrounds. The film simultaneously details the meticulous taxation methods the French employed during this period, which, in attempting to seize a majority of tribes’ rice supply to feed their troops, is tantamount to starvation warfare.

Sembène, however, is less interested in the methodologies of the oppressor than in the unwavering, often silent protest of the Diola people, especially women, in the face of forces that threaten to wipe out the rituals and traditions that define them. In depicting the tribe’s refusal to turn over their rice not as a means to avoid starvation but as a matter of preserving the central value rice has in their cultural heritage, Sembène adds new dimensions to the conflict and complexity to the resistance of the villagers. The inevitable tragedy that concludes the film is quite the gut-punch, but in counterbalancing it with the rebellious enacting of funereal rites by the village women, Emitai becomes equal parts an indictment of colonial violence and a celebration of resilience and self-empowerment through revolutionary means.

In 1975’s Xala, Sembène presents a searing, often hilarious satire of the greed, corruption, and impotence of the new Senegalese governmental leadership following the eradication of French colonial rule. In the opening scene, we see government officials throw out the current French leaders and proudly proclaim that Africa will take back what’s theirs. This moment of triumph, which includes the removal of statues and busts of various French leaders, is swiftly undercut when the Senegalese officials each open a briefcase packed to the brim with 500 Franc bills.

This sequence, laden with anger and biting humor, is indicative of Xala’s absurdist, comedic tone. And as the film shifts its focus to one corrupt official in particular, El Hadji (Thierno Leye), who upon marrying his third wife is cursed with impotence, its satire becomes more metaphorical than direct. Sembène uses El Hadji’s gradual downfall to reflect the moral and political failings of the entire bourgeois class that came into power under the government of President Léopold Sédar Senghor. Through Sembène’s sly, cutting use of irony, claims of modernity and equality under a new “revolutionary socialism” are revealed to be empty promises, barely concealing the anti-feminist and pro-capitalist motives lurking behind them.

Sembène’s critique of a supposedly freed Senegal is intensely savage when it comes to unveiling the hypocrisies of a patriarchal leadership that betrayed the trust of the people it was supposed to aid and protect. Building to a conclusion that’s as funny and gratifying as it is pitiful and physically revolting, Xala captures the continuing repercussions of colonialism and how the forced delusions of a nation would leave its people perversely feeding on one another.

With 1977’s Ceddo, set in Senegal’s distant pre-colonial past, Sembène follows the conflicts between a growing Islamist faction of a once animistic tribe and the Ceddo, or outsiders, who refuse to convert and give up their animistic rituals and beliefs. This is certainly the most didactic entry in this set, but it’s enlivened by the sheer precision of its dialectical oppositions, through which the many hypocrisies of religious fundamentalism and colonization are laid bare.

Ceddo also reveals the complex intersectionality of religions and cultures that were at play in Senegal long before its colonization. Along with the Muslims, who were attempting to seize political power through religious conversions, white Christians and Catholics are present in the form of priests, missionaries, gun runners, and slave traders. The latter are silent through much of the film, but their presence—much like the white French adviser who remains in constant contact with the Senegalese politicians in Xala—speaks to the monumental power and influence whites held in Senegal even before colonialist rulers took over.

While the film’s subject is historical, Sembène draws clear parallels between the past and the post-colonial present of 1977, with the condescending paternalism of the Muslims, particularly the power-hungry imam played by Alioune Fall, mirroring that of the colonialist French. And rather than using traditional Senegalese music, Sembène employed Cameroonian musician Manu Dibango to compose a jazz-funk score that even further connects the events in Ceddo to the time of its release in the late ’70s. For whenever Sembène sets his film, he’s steadfast in his mission to draw meaningful correlations between Senegal’s past and present—each equally integral to the story of the country he loved and helped to define.

Image/Sound

All three transfers come from new 4K digital restorations and they, by and large, look terrific, with vibrant colors and rich details, especially in the costumes and extreme close-ups of faces. There are some shots where the grain is chunkier and the image isn’t quite as sharp, and the Ceddo transfer shows some noticeable signs of damage in several different scenes, but these are mostly minor, non-distracting imperfections. The mono audio track bears the limitations of the production conditions, so some of the dialogue in interior scenes is a bit echoey though still fairly clear. Meanwhile, the music comes through with a surprising robustness.

Extras

A new conversation between Mahen Bonetti, founder and executive director of the African Film Festival, and writer Amy Sall covers a lot of ground in 40 minutes. The two discuss Ousmane Sembène’s early career and discovery in the West before delving into his use of cinema as “a liberatory force” and his sly, caustic use of irony. The only other extra on the disc is a 1981 short documentary by Paulin Soumanou Vieyra in which Sembène espouses much of his philosophy of filmmaking, particularly the importance of understanding history and political complexities of the society one chooses to depict. (Amusingly, Sembène’s wife casually insults American moviegoers, as well as complains about her husband putting film before family.) The stunningly designed package also comes with a 26-page bound booklet containing an essay by film scholar Yasmina Rice, who touches on Sembène’s humor, feminism, and politically charged subjects, while forcefully pushing back against the notion that the director wasn’t much of a formalist.

Overall

These Ousmane Sembène films from 1970s brim with a revolutionary passion and, together, constitute a complex, interlocking portrait of Senegal’s past and present.

Score

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Cast

Andongo Diabon, Michel Renaudeau, Robert Fontaine, Ousmane Camara, Ibou Camara, Abdoulaye Diallo, Alphonse Diatta, Pierre Blanchard, Cherif Tamba, Fode Cambay, Etienne Mané, Joseph Diatta, Dji Niassebaron , Antio Bassene, M’Bissine Thérèse Diop, Thierno Leye, Seune Samb, Younouss Seye, Miriam Niang, Fatim Diagne, Dieynaba Niang, Makhourédia Guèye, Tabara Ndiaye, Alioune Fall, Moustapha Yade, Mamadou N’Diaye Diagne, Nar Sene, Mamadou Dioum, Oumar Gueye.

#Andongo Diabon#Michel Renaudeau#Robert Fontaine#Ousmane Camara#Ibou Camara#Abdoulaye Diallo#Alphonse Diatta#Pierre Blanchard#Cherif Tamba#Fode Cambay#Etienne Mané#Joseph Diatta#Dji Niassebaron#Antio Bassene#M’Bissine Thérèse Diop#Thierno Leye#Seune Samb#Younouss Seye#Miriam Niang#Fatim Diagne#Dieynaba Niang#Makhourédia Guèye#Tabara Ndiaye#Alioune Fall#Moustapha Yade#Mamadou N’Diaye Diagne#Nar Sene#Mamadou Dioum#Oumar Gueye#The Criterion Collection

1 note

·

View note

Text

EMITAI:

Women’s defiance

Against French colonizers

To preserve their rice

youtube

#emitai#random richards#poem#haiku#poetry#haiku poem#poets on tumblr#haiku poetry#haiku form#poetic#criterion collection#criterion channel#ousmane sembène#Andongo Diabon#Robert fontaine#Michel Renaudeau#Ousmane Camara#Ibou Camara#Alphonse Diatta#Pierre Blanchard#cherif tamba#colonialism#fode cambay#Etienne Mane#Joseph diatta#Dji Niassebaron#Antonio Bassene#Youtube

0 notes

Text

French artists Pierre Commoy and Gilles Blanchard also known as Pierre et Gilles. They have been romantic partners since 1976.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

France during the Marriage of Napoleon and Marie Louise (Album du mariage de Marie-Louise et Napoléon Ier)

By Louis-Pierre Baltard — On the occasion of the wedding of Emperor Napoleon I and Archduchess Marie-Louise of Austria, an illustrator, Louis-Pierre Baltard (1764-1846), undertook to retrace the ceremonies and festivals of the spring of 1810 and to make it the subject of an album drawn of eighteen sheets.

Images:

Illumination du Panthéon

Vue de l'Hôtel de Ville illuminé avec la tribune Impériale construite pour la circonstance

Illumination du pont de la Concorde et du Palais du Corps Législatif

Le Retour du cortège par la Galerie du Musée

Feu d'artifices et son décor élevé de l'autre de la Seine, quai Napoléon

Festin dans la deuxième salle provisoire construite dans la cour de l'Ecole Militaire

Le Banquet Impérial dans la salle de spectateur des Tuileries

Ascension en ballon de madame Blanchard

Ballet des danseurs de l'Opéra dans la salle de bal de l'Ecole Militaire

#Louis-Pierre Baltard#Baltard#Napoleon#Paris#France#Album du mariage de Marie-Louise et Napoléon Ier#Marie Louise#Marie-Louise#album#french history#napoleonic era#napoleonic#napoleon bonaparte#first french empire#french empire#19th century#19th century France#history#art#French art

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

Below are 10 articles from Wikipedia's featured articles list. Links and descriptions are below the cut.

On Saturday, May 1, 1920, the Brooklyn Dodgers and the Boston Braves played to a 1–1 tie in 26 innings, the most innings ever played in a single game in the history of Major League Baseball. Both Leon Cadore of Brooklyn and Joe Oeschger of Boston pitched complete games, and with 26 innings pitched, jointly hold the record for the longest pitching appearance in MLB history.

Clarence 13X, also known as Allah the Father (born Clarence Edward Smith) (February 22, 1928 – June 13, 1969), was an American religious leader and the founder of the Five-Percent Nation, sometimes referred to as the Nation of Gods and Earths.

Henry Edwards (27 August 1827 – 9 June 1891) was an English stage actor, writer and entomologist who gained fame in Australia, San Francisco and New York City for his theatre work.

The law school of Berytus (also known as the law school of Beirut) was a center for the study of Roman law in classical antiquity located in Berytus (modern-day Beirut, Lebanon). It flourished under the patronage of the Roman emperors and functioned as the Roman Empire's preeminent center of jurisprudence until its destruction in AD 551.

Minnie Pwerle (also Minnie Purla or Minnie Motorcar Apwerl; born between 1910 and 1922 – 18 March 2006) was an Australian Aboriginal artist. Minnie began painting in 2000 at about the age of 80, and her pictures soon became popular and sought-after works of contemporary Indigenous Australian art.

Ove Jørgensen (Danish pronunciation: [ˈoːvə ˈjœˀnsən]; 5 September 1877 – 31 October 1950) was a Danish scholar of classics, literature and ballet. He formulated Jørgensen's law, which describes the narrative conventions used in Homeric poetry when relating the actions of the gods.

Legends featuring pig-faced women originated roughly simultaneously in The Netherlands, England and France in the late 1630s. The stories tell of a wealthy woman whose body is of normal human appearance, but whose face is that of a pig.

The Private Case is a collection of erotica and pornography held initially by the British Museum and then, from 1973, by the British Library. The collection began between 1836 and 1870 and grew from the receipt of books from legal deposit, from the acquisition of bequests and, in some cases, from requests made to the police following their seizures of obscene material.

Qalaherriaq (Inuktun pronunciation: [qalahəχːiɑq], c. 1834 – June 14, 1856), baptized as Erasmus Augustine Kallihirua, was an Inughuit hunter from Cape York, Greenland. He was recruited in 1850 as an interpreter by the crew of the British survey barque HMS Assistance during the search for John Franklin's lost Arctic expedition.

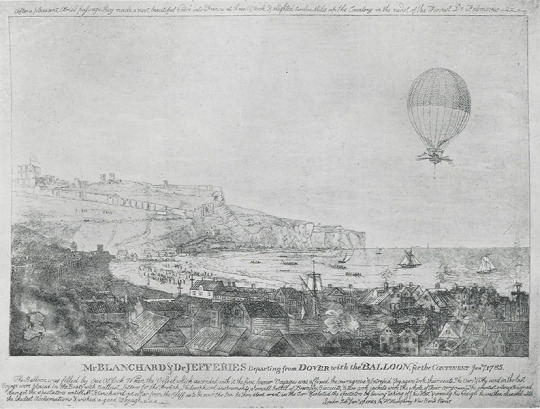

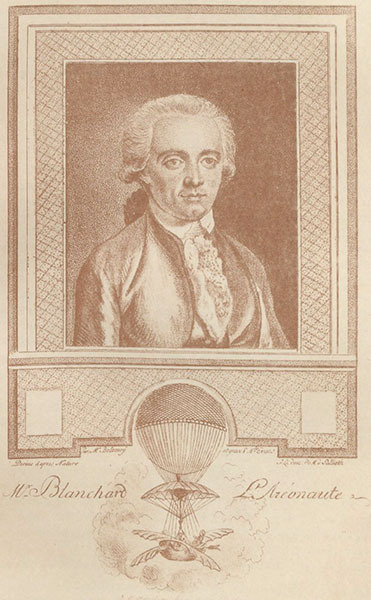

Sophie Blanchard (French pronunciation: [sɔfi blɑ̃ʃaʁ]; 25 March 1778 – 6 July 1819), commonly referred to as Madame Blanchard, was a French aeronaut and the wife of ballooning pioneer Jean-Pierre Blanchard. Blanchard was the first woman to work as a professional balloonist, and after her husband's death she continued ballooning, making more than 60 ascents.

#Wikipedia polls#people said they liked the summaries-first format but it got fewer votes in total so i think I'll stick with summaries-after-the-cut#i would recommend checking out the readmore before you vote though. or don't I'm not your boss

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pierre et Gilles.(Pierre Commoy and Gilles Blanchard). Apolló.2005. Model:Jean-Christophe Blin.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

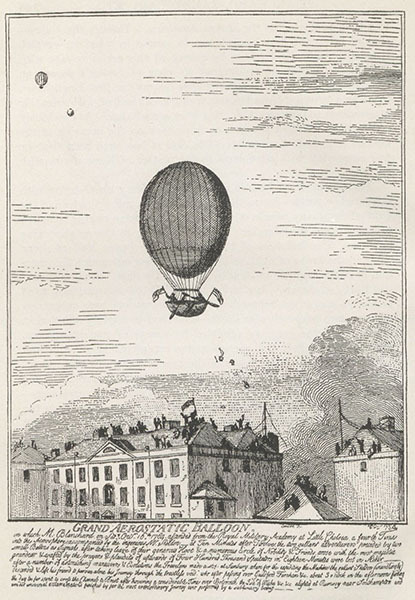

Jean-Pierre Blanchard – Scientist of the Day

Jean-Pierre Blanchard, a French balloonist, was born July 4, 1753.

read more...

#Jean-Pierre Blanchafd#engineering#ballooning#histsci#histSTM#18th century#history of science#Ashworth#Scientist of the Day

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Footnotes 1 - 100

[1] Origin of Species, chap. iii.

[2] Nineteenth Century, Feb. 1888, p. 165.

[3] Leaving aside the pre-Darwinian writers, like Toussenel, Fée, and many others, several works containing many striking instances of mutual aid — chiefly, however, illustrating animal intelligence were issued previously to that date. I may mention those of Houzeau, Les facultés etales des animaux, 2 vols., Brussels, 1872; L. Büchner’s Aus dem Geistesleben der Thiere, 2nd ed. in 1877; and Maximilian Perty’s Ueber das Seelenleben der Thiere, Leipzig, 1876. Espinas published his most remarkable work, Les Sociétés animales, in 1877, and in that work he pointed out the importance of animal societies, and their bearing upon the preservation of species, and entered upon a most valuable discussion of the origin of societies. In fact, Espinas’s book contains all that has been written since upon mutual aid, and many good things besides. If I nevertheless make a special mention of Kessler’s address, it is because he raised mutual aid to the height of a law much more important in evolution than the law of mutual struggle. The same ideas were developed next year (in April 1881) by J. Lanessan in a lecture published in 1882 under this title: La lutte pour l’existence et l’association pour la lutte. G. Romanes’s capital work, Animal Intelligence, was issued in 1882, and followed next year by the Mental Evolution in Animals. About the same time (1883), Büchner published another work, Liebe und Liebes-Leben in der Thierwelt, a second edition of which was issued in 1885. The idea, as seen, was in the air.

[4] Memoirs (Trudy) of the St. Petersburg Society of Naturalists, vol. xi. 1880.

[5] See Appendix I.

[6] George J. Romanes’s Animal Intelligence, 1st ed. p. 233.

[7] Pierre Huber’s Les fourmis indigëes, Génève, 1861; Forel’s Recherches sur les fourmis de la Suisse, Zurich, 1874, and J.T. Moggridge’s Harvesting Ants and Trapdoor Spiders, London, 1873 and 1874, ought to be in the hands of every boy and girl. See also: Blanchard’s Métamorphoses des Insectes, Paris, 1868; J.H. Fabre’s Souvenirs entomologiques, Paris, 1886; Ebrard’s Etudes des mœurs des fourmis, Génève, 1864; Sir John Lubbock’s Ants, Bees, and Wasps, and so on.

[8] Forel’s Recherches, pp. 244, 275, 278. Huber’s description of the process is admirable. It also contains a hint as to the possible origin of the instinct (popular edition, pp. 158, 160). See Appendix II.

[9] The agriculture of the ants is so wonderful that for a long time it has been doubted. The fact is now so well proved by Mr. Moggridge, Dr. Lincecum, Mr. MacCook, Col. Sykes, and Dr. Jerdon, that no doubt is possible. See an excellent summary of evidence in Mr. Romanes’s work. See also Die Pilzgaerten einiger Süd-Amerikanischen Ameisen, by Alf. Moeller, in Schimper’s Botan. Mitth. aus den Tropen, vi. 1893.

[10] This second principle was not recognized at once. Former observers often spoke of kings, queens, managers, and so on; but since Huber and Forel have published their minute observations, no doubt is possible as to the free scope left for every individual’s initiative in whatever the ants do, including their wars.

[11] H.W. Bates, The Naturalist on the River Amazons, ii. 59 seq.

[12] N. Syevertsoff, Periodical Phenomena in the Life of Mammalia, Birds, and Reptiles of Voronèje, Moscow, 1855 (in Russian).

[13] A. Brehm, Life of Animals, iii. 477; all quotations after the French edition.

[14] Bates, p. 151.

[15] Catalogue raisonné des oiseaux de la faune pontique, in Démidoff’s Voyage; abstracts in Brehm, iii. 360. During their migrations birds of prey often associate. One flock, which H. Seebohm saw crossing the Pyrenees, represented a curious assemblage of “eight kites, one crane, and a peregrine falcon” (The Birds of Siberia, 1901, p. 417).

[16] Birds in the Northern Shires, p. 207.

[17] Max. Perty, Ueber das Seelenleben der Thiere (Leipzig, 1876), pp. 87, 103.

[18] G. H. Gurney, The House-Sparrow (London, 1885), p. 5.

[19] Dr. Elliot Couës, Birds of the Kerguelen Island, in Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, vol. xiii. No. 2, p. 11.

[20] Brehm, iv. 567.

[21] As to the house-sparrows, a New Zealand observer, Mr. T.W. Kirk, described as follows the attack of these “impudent” birds upon an “unfortunate” hawk. — “He heard one day a most unusual noise, as though all the small birds of the country had joined in one grand quarrel. Looking up, he saw a large hawk (C. gouldi — a carrion feeder) being buffeted by a flock of sparrows. They kept dashing at him in scores, and from all points at once. The unfortunate hawk was quite powerless. At last, approaching some scrub, the hawk dashed into it and remained there, while the sparrows congregated in groups round the bush, keeping up a constant chattering and noise” (Paper read before the New Zealand Institute; Nature, Oct. 10, 1891).

[22] Brehm, iv. 671 seq.

[23] R. Lendenfeld, in Der zoologische Garten, 1889.

[24] Syevettsoff’s Periodical Phenomena, p. 251.

[25] Seyfferlitz, quoted by Brehm, iv. 760.

[26] The Arctic Voyages of A.E. Nordenskjöld, London, 1879, p. 135. See also the powerful description of the St. Kilda islands by Mr. Dixon (quoted by Seebohm), and nearly all books of Arctic travel.

[27] See Appendix III.

[28] Elliot Couës, in Bulletin U.S. Geol. Survey of Territories, iv. No. 7, pp. 556, 579, etc. Among the gulls (Larus argentatus), Polyakoff saw on a marsh in Northern Russia, that the nesting grounds of a very great number of these birds were always patrolled by one male, which warned the colony of the approach of danger. All birds rose in such case and attacked the enemy with great vigour. The females, which had five or six nests together On each knoll of the marsh, kept a certain order in leaving their nests in search of food. The fledglings, which otherwise are extremely unprotected and easily become the prey of the rapacious birds, were never left alone (“Family Habits among the Aquatic Birds,” in Proceedings of the Zool. Section of St. Petersburg Soc. of Nat., Dec. 17, 1874).

[29] Brehm Father, quoted by A. Brehm, iv. 34 seq. See also White’s Natural History of Selborne, Letter XI.

[30] Dr. Couës, Birds of Dakota and Montana, in Bulletin U.S. Survey of Territories, iv. No. 7.

[31] It has often been intimated that larger birds may occasionally transport some of the smaller birds when they cross together the Mediterranean, but the fact still remains doubtful. On the other side, it is certain that some smaller birds join the bigger ones for migration. The fact has been noticed several times, and it was recently confirmed by L. Buxbaum at Raunheim. He saw several parties of cranes which had larks flying in the midst and on both sides of their migratory columns (Der zoologische Garten, 1886, p. 133).

[32] H. Seebohm and Ch. Dixon both mention this habit.

[33] The fact is well known to every field-naturalist, and with reference to England several examples may be found in Charles Dixon’s Among the Birds in Northern Shires. The chaffinches arrive during winter in vast flocks; and about the same time, i.e. in November, come flocks of bramblings; redwings also frequent the same places “in similar large companies,” and so on (pp. 165, 166).

[34] S.W. Baker, Wild Beasts, etc., vol. i. p. 316.

[35] Tschudi, Thierleben der Alpenwelt, p. 404.

[36] Houzeau’s Études, ii. 463.

[37] For their hunting associations see Sir E. Tennant’s Natural History of Ceylon, quoted in Romanes’s Animal Intelligence, p. 432.

[38] See Emil Hüter’s letter in L. Büchner’s Liebe.

[39] See Appendix IV.

[40] With regard to the viscacha it is very interesting to note that these highly-sociable little animals not only live peaceably together in each village, but that whole villages visit each other at nights. Sociability is thus extended to the whole species — not only to a given society, or to a nation, as we saw it with the ants. When the farmer destroys a viscacha-burrow, and buries the inhabitants under a heap of earth, other viscachas — we are told by Hudson — “come from a distance to dig out those that are buried alive” (l.c., p. 311). This is a widely-known fact in La Plata, verified by the author.

[41] Handbuch für Jäger und Jagdberechtigte, quoted by Brehm, ii. 223.

[42] Buffon’s Histoire Naturelle.

[43] In connection with the horses it is worthy of notice that the quagga zebra, which never comes together with the dauw zebra, nevertheless lives on excellent terms, not only with ostriches, which are very good sentries, but also with gazelles, several species of antelopes, and gnus. We thus have a case of mutual dislike between the quagga and the dauw which cannot be explained by competition for food. The fact that the quagga lives together with ruminants feeding on the same grass as itself excludes that hypothesis, and we must look for some incompatibility of character, as in the case of the hare and the rabbit. Cf., among others, Clive Phillips-Wolley’s Big Game Shooting (Badminton Library), which contains excellent illustrations of various species living together in East Africa.

[44] Our Tungus hunter, who was going to marry, and therefore was prompted by the desire of getting as many furs as he possibly could, was beating the hill-sides all day long on horseback in search of deer. His efforts were not rewarded by even so much as one fallow deer killed every day; and he was an excellent hunter.

[45] According to Samuel W. Baker, elephants combine in larger groups than the “compound family.” “I have frequently observed,” he wrote, “in the portion of Ceylon known as the Park Country, the tracks of elephants in great numbers which have evidently been considerable herds that have joined together in a general retreat from a ground which they considered insecure” (Wild Beasts and their Ways, vol. i. p. 102).

[46] Pigs, attacked by wolves, do the same (Hudson, l.c.).

[47] Romanes’s Animal Intelligence, p. 472.

[48] Brehm, i. 82; Darwin’s Descent of Man, ch. iii. The Kozloff expedition of 1899–1901 have also had to sustain in Northern Thibet a similar fight.

[49] The more strange was it to read in the previously-mentioned article by Huxley the following paraphrase of a well-known sentence of Rousseau: “The first men who substituted mutual peace for that of mutual war — whatever the motive which impelled them to take that step — created society” (Nineteenth Century, Feb. 1888, p. 165). Society has not been created by man; it is anterior to man.

[50] Such monographs as the chapter on “Music and Dancing in Nature” which we have in Hudson’s Naturalist on the La Plata, and Carl Gross’ Play of Animals, have already thrown a considerable light upon an instinct which is absolutely universal in Nature.

[51] Not only numerous species of birds possess the habit of assembling together — in many cases always at the same spot — to indulge in antics and dancing performances, but W.H. Hudson’s experience is that nearly all mammals and birds (“probably there are really no exceptions”) indulge frequently in more or less regular or set performances with or without sound, or composed of sound exclusively (p. 264).

[52] For the choruses of monkeys, see Brehm.

[53] Haygarth, Bush Life in Australia, p. 58.

[54] To quote but a few instances, a wounded badger was carried away by another badger suddenly appearing on the scene; rats have been seen feeding a blind couple (Seelenleben der Thiere, p. 64 seq.). Brehm himself saw two crows feeding in a hollow tree a third crow which was wounded; its wound was several weeks old (Hausfreund, 1874, 715; Büchner’s Liebe, 203). Mr. Blyth saw Indian crows feeding two or three blind comrades; and so on.

[55] Man and Beast, p. 344.

[56] L.H. Morgan, The American Beaver, 1868, p. 272; Descent of Man, ch. iv.

[57] One species of swallow is said to have caused the decrease of another swallow species in North America; the recent increase of the missel-thrush in Scotland has caused the decrease of the song.thrush; the brown rat has taken the place of the black rat in Europe; in Russia the small cockroach has everywhere driven before it its greater congener; and in Australia the imported hive-bee is rapidly exterminating the small stingless bee. Two other cases, but relative to domesticated animals, are mentioned in the preceding paragraph. While recalling these same facts, A.R. Wallace remarks in a footnote relative to the Scottish thrushes: “Prof. A. Newton, however, informs me that these species do not interfere in the way here stated” (Darwinism, p. 34). As to the brown rat, it is known that, owing to its amphibian habits, it usually stays in the lower parts of human dwellings (low cellars, sewers, etc.), as also on the banks of canals and rivers; it also undertakes distant migrations in numberless bands. The black rat, on the contrary, prefers staying in our dwellings themselves, under the floor, as well as in our stables and barns. It thus is much more exposed to be exterminated by man; and we cannot maintain, with any approach to certainty, that the black rat is being either exterminated or starved out by the brown rat and not by man.

[58] “But it may be urged that when several closely-allied species inhabit the same territory, we surely ought to find at the present time many transitional forms.... By my theory these allied species are descended from a common parent; and during the process of modification, each has become adapted to the conditions of life of its own region, and has supplanted and exterminated its original parent-form and all the transitional varieties between its past and present states” (Origin of Species, 6th ed. p. 134); also p. 137, 296 (all paragraph “On Extinction”).

[59] According to Madame Marie Pavloff, who has made a special study of this subject, they migrated from Asia to Africa, stayed there some time, and returned next to Asia. Whether this double migration be confirmed or not, the fact of a former extension of the ancestor of our horse over Asia, Africa, and America is settled beyond doubt.

[60] The Naturalist on the River Amazons, ii. 85, 95.

[61] Dr. B. Altum, Waldbeschädigungen durch Thiere und Gegenmittel (Berlin, 1889), pp. 207 seq.

[62] Dr. B. Altum, ut supra, pp. 13 and 187.

[63] A. Becker in the Bulletin de la Société des Naturalistes de Moscou, 1889, p. 625.

[64] See Appendix V.

[65] Russkaya Mysl, Sept. 1888: “The Theory of Beneficency of Struggle for Life, being a Preface to various Treatises on Botanics, Zoology, and Human Life,” by an Old Transformist.

[66] “One of the most frequent modes in which Natural Selection acts is, by adapting some individuals of a species to a somewhat different mode of life, whereby they are able to seize unappropriated places in Nature” (Origin of Species, p. 145) — in other words, to avoid competition.

[67] See Appendix VI.

[68] Nineteenth Century, February 1888, p. 165

[69] The Descent of Man, end of ch. ii. pp. 63 and 64 of the 2nd edition.

[70] Anthropologists who fully endorse the above views as regards man nevertheless intimate, sometimes, that the apes live in polygamous families, under the leadership of “a strong and jealous male.” I do not know how far that assertion is based upon conclusive observation. But the passage from Brehm’s Life of Animals, which is sometimes referred to, can hardly be taken as very conclusive. It occurs in his general description of monkeys; but his more detailed descriptions of separate species either contradict it or do not confirm it. Even as regards the cercopithèques, Brehm is affirmative in saying that they “nearly always live in bands, and very seldom in families” (French edition, p. 59). As to other species, the very numbers of their bands, always containing many males, render the “polygamous family” more than doubtful further observation is evidently wanted.

[71] Lubbock, Prehistoric Times, fifth edition, 1890.

[72] That extension of the ice-cap is admitted by most of the geologists who have specially studied the glacial age. The Russian Geological Survey already has taken this view as regards Russia, and most German specialists maintain it as regards Germany. The glaciation of most of the central plateau of France will not fail to be recognized by the French geologists, when they pay more attention to the glacial deposits altogether.

[73] Prehistoric Times, pp. 232 and 242.

[74] Bachofen, Das Mutterrecht, Stuttgart, 1861; Lewis H. Morgan, Ancient Society, or Researches in the Lines of Human Progress from Savagery through Barbarism to Civilization, New York, 1877; J.F. MacLennan, Studies in Ancient History, 1st series, new edition, 1886; 2nd series, 1896; L. Fison and A.W. Howitt, Kamilaroi and Kurnai, Melbourne. These four writers — as has been very truly remarked by Giraud Teulon, — starting from different facts and different general ideas, and following different methods, have come to the same conclusion. To Bachofen we owe the notion of the maternal family and the maternal succession; to Morgan — the system of kinship, Malayan and Turanian, and a highly gifted sketch of the main phases of human evolution; to MacLennan — the law of exogeny; and to Fison and Howitt — the cuadro, or scheme, of the conjugal societies in Australia. All four end in establishing the same fact of the tribal origin of the family. When Bachofen first drew attention to the maternal family, in his epoc.making work, and Morgan described the clan-organization, — both concurring to the almost general extension of these forms and maintaining that the marriage laws lie at the very basis of the consecutive steps of human evolution, they were accused of exaggeration. However, the most careful researches prosecuted since, by a phalanx of students of ancient law, have proved that all races of mankind bear traces of having passed through similar stages of development of marriage laws, such as we now see in force among certain savages. See the works of Post, Dargun, Kovalevsky, Lubbock, and their numerous followers: Lippert, Mucke, etc.

[75] See Appendix VII.

[76] For the Semites and the Aryans, see especially Prof. Maxim Kovalevsky’s Primitive Law (in Russian), Moscow, 1886 and 1887. Also his Lectures delivered at Stockholm (Tableau des origines et de l’évolution de la famille et de la propriété, Stockholm, 1890), which represents an admirable review of the whole question. Cf. also A. Post, Die Geschlechtsgenossenschaft der Urzeit, Oldenburg 1875.

[77] It would be impossible to enter here into a discussion of the origin of the marriage restrictions. Let me only remark that a division into groups, similar to Morgan’s Hawaian, exists among birds; the young broods live together separately from their parents. A like division might probably be traced among some mammals as well. As to the prohibition of relations between brothers and sisters, it is more likely to have arisen, not from speculations about the bad effects of consanguinity, which speculations really do not seem probable, but to avoid the too-easy precocity of like marriages. Under close cohabitation it must have become of imperious necessity. I must also remark that in discussing the origin of new customs altogether, we must keep in mind that the savages, like us, have their “thinkers” and savants — wizards, doctors, prophets, etc. — whose knowledge and ideas are in advance upon those of the masses. United as they are in their secret unions (another almost universal feature) they are certainly capable of exercising a powerful influence, and of enforcing customs the utility of which may not yet be recognized by the majority of the tribe.

[78] Col. Collins, in Philips’ Researches in South Africa, London, 1828. Quoted by Waitz, ii. 334.

[79] Lichtenstein’s Reisen im südlichen Afrika, ii. Pp. 92, 97. Berlin, 1811.

[80] Waitz, Anthropologie der Naturvolker, ii. pp. 335 seq. See also Fritsch’s Die Eingeboren Afrika’s, Breslau, 1872, pp. 386 seq.; and Drei Jahre in Süd Afrika. Also W. Bleck, A Brief Account of Bushmen Folklore, Capetown, 1875.

[81] Elisée Reclus, Géographie Universelle, xiii. 475.

[82] P. Kolben, The Present State of the Cape of Good Hope, translated from the German by Mr. Medley, London, 1731, vol. i. pp. 59, 71, 333, 336, etc.

[83] Quoted in Waitz’s Anthropologie, ii. 335 seq.

[84] The natives living in the north of Sidney, and speaking the Kamilaroi language, are best known under this aspect, through the capital work of Lorimer Fison and A.W. Howitt, Kamilaroi and Kurnaii, Melbourne, 1880. See also A.W. Howitt’s “Further Note on the Australian Class Systems,” in Journal of the Anthropological Institute, 1889, vol. xviii. p. 31, showing the wide extension of the same organization in Australia.

[85] The Folklore, Manners, etc., of Australian Aborigines, Adelaide, 1879, p. 11.

[86] Gray’s Journals of Two Expeditions of Discovery in North-West and Western Australia, London, 1841, vol. ii. pp. 237, 298.

[87] Bulletin de la Société d’Anthropologie, 1888, vol. xi. p. 652. I abridge the answers.

[88] Bulletin de la Société d’Anthropologie, 1888, vol. xi. p. 386.

[89] The same is the practice with the Papuas of Kaimani Bay, who have a high reputation of honesty. “It never happens that the Papua be untrue to his promise,” Finsch says in Neuguinea und seine Bewohner, Bremen, 1865, p. 829.

[90] Izvestia of the Russian Geographical Society, 1880, pp. 161 seq. Few books of travel give a better insight into the petty details of the daily life of savages than these scraps from Maklay’s notebooks.

[91] L.F. Martial, in Mission Scientifique au Cap Horn, Paris, 1883, vol. i. pp. 183–201.

[92] Captain Holm’s Expedition to East Greenland.

[93] In Australia whole clans have been seen exchanging all their wives, in order to conjure a calamity (Post, Studien zur Entwicklungsgeschichte des Familienrechts, 1890, p. 342). More brotherhood is their specific against calamities.

[94] Dr. H. Rink, The Eskimo Tribes, p. 26 (Meddelelser om Grönland, vol. xi. 1887).

[95] Dr. Rink, loc. cit. p. 24. Europeans, grown in the respect of Roman law, are seldom capable of understanding that force of tribal authority. “In fact,” Dr. Rink writes, “it is not the exception, but the rule, that white men who have stayed for ten or twenty years among the Eskimo, return without any real addition to their knowledge of the traditional ideas upon which their social state is based. The white man, whether a missionary or a trader, is firm in his dogmatic opinion that the most vulgar European is better than the most distinguished native.” — The Eskimo Tribes, p. 31.

[96] Dall, Alaska and its Resources, Cambridge, U.S., 1870.

[97] Dall saw it in Alaska, Jacobsen at Ignitok in the vicinity of the Bering Strait. Gilbert Sproat mentions it among the Vancouver indians; and Dr. Rink, who describes the periodical exhibitions just mentioned, adds: “The principal use of the accumulation of personal wealth is for periodically distributing it.” He also mentions (loc. cit. p. 31) “the destruction of property for the same purpose,’ (of maintaining equality).

[98] See Appendix VIII.

[99] Veniaminoff, Memoirs relative to the District of Unalashka (Russian), 3 vols. St. Petersburg, 1840. Extracts, in English, from the above are given in Dall’s Alaska. A like description of the Australians’ morality is given in Nature, xlii. p. 639.

[100] It is most remarkable that several writers (Middendorff, Schrenk, O. Finsch) described the Ostyaks and Samoyedes in almost the same words. Even when drunken, their quarrels are insignificant. “For a hundred years one single murder has been committed in the tundra;” “their children never fight;” “anything may be left for years in the tundra, even food and gin, and nobody will touch it;” and so on. Gilbert Sproat “never witnessed a fight between two sober natives” of the Aht Indians of Vancouver Island. “Quarreling is also rare among their children.” (Rink, loc. cit.) And so on.

#organization#revolution#mutual aid#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#anarchy#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#a factor of evolution#petr kropotkin

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Airborne 3

Jean Pierre took my leftover Continental dollars and seated me in a back seat of Blanchard's Balloon Deprived of his atlas he flew forth guided only by a Dream Book so we soon fell asleep and entered his fantasy of a sky that went on forever and ever and ever like a roll of bad wallpaper that only ends when the glue runs out

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

FELIX LEE? não! é apenas LOUIS BLANCHARD, ele é filho de HEBE do chalé DEZOITO e tem VINTE E DOIS ANOS. a tv hefesto informa no guia de programação que ele está no NÍVEL TRÊS por estar no acampamento há TREZE ANOS, sabia? e se lá estiver certo, LOUIE é bastante ALEGRE mas também dizem que ele é NOSTÁLGICO. mas você sabe como hefesto é, sempre inventando fake news pra atrair audiência.

PODERES.

[ MANIPULAÇÃO DE JUVENTUDE ] — Louis é capaz de absorver para si a juventude de um alvo, envelhecendo a vítima com apenas com um toque; ou dar juventude, permitindo que o estado físico de uma pessoa retorne temporária ou permanentemente ao seu estado mais jovem e vital. Costuma se dar bem com quantidades pequenas, mas se abusa do poder pode ficar visivelmente mais velho e cansado se não repor a juventude que perdeu.

HABILIDADES.

Agilidade sobre-humana e sentidos aguçados.

ARMA.

[ LUMINEUSE ] — Um sabre francês de bronze celestial, tem mais ou menos 85 centímetros no total, contando com a lâmina e o punho. A espada foi forjada por um filho de Hefesto nos primeiros anos de Louis no acampamento, e o seu guarda-mão decorado com um pássaro é a demonstração de maestria do ferreiro. A Luminosa tem esse nome por servir de condutor para os poderes do semideus: ele pode usá-la para sugar a juventude de sua vítima e piorar um ferimento, algo que faz a lâmina brilhar em bronze. Consegue levar Lumineuse por aí com facilidade, já que se transforma num adornado bracelete de bronze com pingente de pássaro e permanece em seu braço enquanto não a usa.

BÊNÇÃO.

[ BÊNÇÃO DE APOLO ] — Algo conhecido por qualquer pessoa que cruze os caminhos com Pierre é seu… charme fora do comum. Louis não sabe como o pai conseguiu encontrar outro Deus durante suas saídas, muito menos como haviam se dado tão bem, mas a visão do homem loiro nunca iria sair da mente infantil de Louie… que, sem nenhum aviso prévio, falou para o Deus que também queria ser um loiro natural bonito assim. Blanchard então foi tocado pelos raios de sol e, enquanto Apolo ria e bagunçava seus cabelos, ganhou uma descoloração mágica instantânea. Com o passar dos anos, a criança cresceu e finalmente entendeu o que tinha acontecido: havia presenciado um momento quase humano do Deus, que, de boníssimo humor, lhe concedeu uma bênção do Sol. Além dos fios loiros, também consegue se curar mais rápido do que o normal e fazer com que flores possam ter capacidades curativas para outras pessoas. Não é capaz de controlar raios de sol, mas sua pele é mais quente do que o normal e passa uma sensação de conforto para as pessoas que estão ao seu lado por conta disso.

HISTÓRIA.

Louis era um espírito livre desde que nasceu, mesmo não tendo muita escolha quanto a isso de qualquer maneira. Seu pai era o que podia ser chamado de bon-vivant: com um sorriso charmoso e pronto para aproveitar cada segundo de sua vida, era sempre visto pelas noites boêmias de Paris e fugia de qualquer tipo de responsabilidade, mas não fugia de uma boa história para contar. Pierre lembrava perfeitamente da garota dançando sem qualquer preocupação no meio de uma festa e como ficou totalmente sem chão ao encará-la, encantado de verdade com a sua presença. Se apaixonou tão rápido quanto teve seu coração quebrado, pois depois de uma semana com a garota, nunca mais a viu em sua vizinhança — ou em qualquer outro lugar além de seus sonhos.

Surpreendendo exatamente ninguém, é claro que não ficou muito feliz vendo a cesta com um bebezinho em sua porta, até entender direito o que aquilo significava. Conseguia ver alguns detalhes que tinha gostado tanto no rosto do menininho, principalmente as sardas e os olhos da mulher que sumiu. Bem, se não tinha a sua amante, certamente tinha um presentinho para lembrar dos bons dias que viveu intensamente. Prometeu que iria encontrá-la e iriam cuidar do bebê, nem que fizesse isso pelo resto da vida.

Ao ficar anos procurando por seu amor, esqueceu de ser um pai presente para Louis. Certamente o ensinava que a vida era curta demais para não fazer as coisas, que deveria ir atrás dos seus sonhos e fazer do mundo a sua casa, mas faltava as reuniões de pais e a maior parte dos aniversários. Enquanto mudava de país em país, um histórico de acidentes os perseguiam: casas assaltadas, carros quebrados, algumas expulsões de escola. Quando um lugar já não era mais interessante para Pierre, era colocar as poucas coisas que tinham numa mala e partir para outra aventura. Foi assim que parou em Nova York, tão movimentada quanto a capital francesa.

Louis não passava dos nove anos quando um garoto não muito mais alto o encurralou na rua, completamente desesperado. Bem, garoto era modo de falar, já que a grande maioria dos adolescentes não tem pernas de bode e chifres — mas quem era ele para julgar, não é mesmo? Algumas peças começaram a se juntar e, depois de dias turbulentos e complicados, conseguiu chegar no Acampamento Meio Sangue. Pierre não se surpreendeu muito quando recebeu uma chamada de telefone do filho, já que sequer deu falta do menino.

Desde então, viveu sozinho no Acampamento, dedicando seu tempo para os Campos de Morango, as aulas intermináveis e, se tivesse que ganhar um centavo por cada guerra que participou, teria dois centavos — o que não é muito, mas é certamente mais do que gostaria. Foi no aniversário de onze anos nas colinas que juntou as suas coisas para se mudar, se inscrevendo na Universidade de Nova Roma e começando um capítulo novo em sua vida… que acabou muito rápido, diga-se de passagem. Ao receber a mensagem do Sr. D enquanto seu ano letivo sequer tinha acabado, soltou um suspiro longo e, ao voltar e questionar o diretor se tinha sentido saudades enquanto estava fora, recebeu um “Sai fora, Lucio” que lembra até hoje.

O que restou foi voltar à rotina de sempre, sozinho como de costume. Mesmo sendo alegre e brilhante, está sempre olhando pela janela pensando em sua faculdade e como queria estar respirando novos ares, mas gostava demais de viver para estar passando risco em Nova Roma. Quer dizer, o que seu pai falaria se o visse assim, escondendo-se e não vivendo o que queria? Era melhor ficar vivo para descobrir.

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

6 juillet 1819 : décès de Sophie Blanchard, première femme aéronaute professionnelle ➽ http://bit.ly/Sophie-Blanchard On raconte que sa mère étant enceinte, vit un voyageur qui lui promit d’épouser l’enfant dont elle devait accoucher, si c’était une fille : ce voyageur était Jean-Pierre Blanchard, le célèbre aéronaute, avec qui la jeune Sophie Armant fut mariée dans son adolescence

#CeJourLà#6Juillet#Blanchard#Sophie#aéronaute#femme#ballon#voyages#aériens#airs#histoire#france#history#passé#past#français#french#news#événement#newsfromthepast

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Bamboozled’ is the Forgotten Gem in Spike Lee’s Career

A new Criterion Collection edition of the 2000 film—about a primetime TV minstrel show that becomes a hit—means its finally time to give this scorched-earth satire its due

It still shocks you. No matter how many times you’ve seen those images, in history books and documentaries, museum exhibits and memorabilia collections, banned cartoons and the occasional old movie preserved on TCM (and preceded by a warning), the actual witnessing of it still stops you in your tracks. You don’t have to know that people would place corks in a small metal bowl, pour alcohol on them, light them on fire, mash the ashes and add water. (Later, a performer might have used standard shoe polish, but this was the traditional method.) You don’t even have to observe them methodically apply that concoction to their foreheads, cheeks, nose, chin, jawline, or complement the look with red lipstick. You just have to see the result — the actual look of blackface on someone — to feel shaken. And this time, it’s not in faded black and white but in living 21st-century color, staring right back at you.

Spike Lee knows the historical import of these images. He understands the power of cinema, and the necessity of provocation, and how sometimes a blunt instrument is required in lieu of a sharp blade. He’s aware of how the minstrel show had been used to dehumanize people, to reduce them and belittle them, and how so much of that legacy continued even after that mode of entertainment became a thing of the “distant past.” Bamboozled, his 2000 satire — Lee has his lead character read the definition of the word “satire” to the audience in the opening sequence, just to silence any doubters — talks much trash and throws a lot of caricaturish, over-the-top stuff at you in its first act. Some of it inspires eye-rolling, as obvious targets get pincushioned. Other bits have you laughing despite your better angels and instincts.

Then it arrives at the moment when two actors have to “blacken up.” The film follows each step. This scene will repeat itself throughout the film three times, all of them set to Terence Blanchard’s musical lament. During the third go-round, you can see tears rolling down one of the man’s cheeks. Each time they finish the ritual, mugging desperately into the camera as they bound onto a TV studio’s stage, made up to look like the previous 50 years never happened, you get the wind knocked out of you. That’s the point. Lee has made something that could be considered a comedy. But he’s not playing around.

Editor’s picks

Nestled in between his highly successful concert movie of the highly successful comedy tour The Original Kings of Comedy and his stunning post-9/11 parable 25th Hour, Bamboozled has been consigned to being an odd blip on his filmography. Audiences were baffled. Critics were bent out of shape over it. The movie was considered too on-brand to be an outlier but too scattershot to be a masterpiece, too broad, too sour, too black, too strong. Now that the Criterion Collection has just released a new DVD/Blu-ray edition of this long out-of-print title, it’s easier to recognize this cri de coeur for what it is: a history lesson on decades of screen (mis)representation, a look back in anger but also profound sorrow, a flawed and sometimes flailing takedown that becomes more effective the more times you see it. At the turn of the century, it seemed like an crude attempt at sketch comedy. Twenty years later, the movie feels like a forgotten gem in Spike’s career, one who’s spit-polish and reappraisal comes at the exact right moment.

https://www.rollingstone.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Bamboozled.jpg?w=1024

Bamboozled‘s premise is the most modest of proposals: TV producer Pierre Delacroix (Damon Wayans) wants to make shows about average, middle-class African-American families. His white boss (Michael Rappaport), who claims to know more about black culture then the man sitting in front of him, wants more “hip” and outrageous programming. So, in an effort to get fired, Delacroix and his assistant Sloan Hopkins (Jada Pinkett Smith) suggest The New Millennium Minstrel Show. It’s exactly what it sounds like: an update of an old-fashioned 19th-century variety show full of songs, dances, skits and corrosive stereotypes. He hires two street performers, Manray and Womack (tap-dancing phenom Savion Glover and In Living Color‘s Tommy Davidson), to play “Mantan” and his sidekick “Sleep ‘n’ Eat.” The exec suggests they set it on a plantation; Delacroix offers the idea of a watermelon patch instead. They produce a pilot that makes those old Amos & Andy episodes look like Joe Turner’s Come and Gone. Delacroix believes that something this blatantly offensive is destined to get him canned. Naturally, the network gives him a 12-episode order. The nation gives him a hit show.

Related

It’s a tale as old as time, or at least The Producers. Mel Brooks’ farce is a simply a high point in “sick” humor, however, and an expansion on the notion that comedy is tragedy plus time divided by bad taste, a wink and massive cajones. Bamboozled has other things on its troubled mind, namely the use of entertainment as a propaganda tool and a prejudice machine. On the Criterion edition’s supplementary disc, there’s a conversation between Lee and critic/programmer Ashley Clark (whose book Facing Blackness is a brilliant forensic dissection of the film) in which the director admits that prior to the project’s conception, he’d been thinking a lot about two then-recent birthdays: the centennial of the movies and the 50th anniversary of television. These were mediums he dearly loved, and that showed him the world. They also reflected back a purposefully one-sided, less-than-one-dimensional view of the African-American experience. Many filmmakers launched counterattacks by the late ’90s — not just Lee, but also Charles Burnett, Julie Dash, Melvin Van Peebles, John Singleton, Kasi Lemmons, Gordon Parks, Ivan Dixon, Kathleen Collins, Marlon Riggs, and a growing list of others.

Yet for every Losing Ground, there was decades of lost ground via endlessly recycled images of buffoons and simpletons. There was also the Seventies sitcoms like Good Times and The Jeffersons, which — assuming Bamboozled‘s skeptical view of them was reflective of its creator’s mindset — Lee also saw as harmful. Minstrelsy was gone, but what lay at the roots of those shows wasn’t dead. It had just changed its makeup. Still, what would happen if someone really tried to resurrect those old vaudeville-style, pre-Civil War to Jim Crow era shows and sell them as ready-for-primetime programming? For Delacroix, it was a way out of a bankrupt creative situation, with the delusional notion of it being a subversive way to smuggle social commentary in. For Sloan, it’s a way to prove to her militant brother (Yasiin “Mos Def” Bey) that she’s not a corporate sellout. For the two New Millennium actors, who view TV as a level-up from tap-dancing in midtown for chump change, it’s a way to “keep the income coming in.” Everyone ends up losing a piece of their soul regardless of their motivations.

Delacroix gets checkmated because he inadvertently gives the people exactly what they want — a little bit of that “Make America Great Again” throwback mockery. (Dig how the movie’s crude look, courtesy of a consumer DV camera, switches to Super 16mm lushness during these sequences. It’s like gazing a beautiful, poisonous flower.) Soon, the studio audience is showing up in blackface, with everyone pledging allegiance to a racial epithet. Pierre ends up surrounded by kitsch racist-memorabilia, a piggy bank taunting him by throwing endless phantom coins into its mouth. Sloan and the show’s stars end up broken. Like Network, one of several movies which Bamboozled owes a partial debt to, the narrative ends with a plea to yell that you’re not going to take it anymore, and a death. Delacroix’s experiment has spectacularly backfired. So had Spike’s, for the opposite reason: He’d given folks something they really didn’t want in 2000, i.e. to have their face rubbed in a centuries’ worth of hate.

There’s a lot going on in Bamboozled that isn’t a direct poke in your eye, of course. There’s Wayans’ Harvard-affected, every-syllable-has-its-day accent, which is the perfect aural equivalent of his name. There are the arguments between Smith, who’s genuinely wonderful in the movie, and Bey about ideology. There is Bey’s group the Mau-Mau’s, Spike’s scorched-earth take on revolution-spouting, consciousness-raising hip-hop groups and the one thing even the film’s fans have a hard time with. There’s Paul Mooney as Junebug, Pierre’s dad and a comedian who’s admirably stuck to his well-honed club shtick; in a perfect world, the movie would’ve helped reintroduce this legendary stand-up and Richard Pryor collaborator to a larger audience. (Chappelle’s Show would accomplish that a few years later.) And there’s the commercial parodies, from ���Bomb Malt Liquor” to a deathblow critique of Tommy Hilfiger’s marketing to the African-American community.

But the underlying feelings that inform the movie are rage and pain. That’s what you see in Delacroix’s eyes when his boss brusquely uses slurs and ill-advised slang to prove the he’s more “down,” and when the producer says that he refuses to keep pumping out shit “like Homeboys in Outer Space” — a hilarious throwaway line until you remember this was a real, honest-to-God series. You see it in his face when white coworkers excitedly praise him and he watches white people cracking up at the performers denigrating themselves for their delight. (It’s hard to watch these scenes and not think of Dave Chappelle’s story about seeing a Caucasian crew member laugh a little too intensely at a sketch, a moment that forced the comedian to pull the plug on his own show.) And you definitely see it in Bamboozled‘s coup de grace, a climactic roll call of racist screen imagery throughout the ages that presents you with a century’s worth of humiliation 24 frames per second.

This is the history the film wants to remind you of; this is the history it wants you to reckon with. And seeing the movie through the lens of our current moment, history has indeed been kind — agonizingly so — to what Bamboozled is talking about. That so many people have inherently picked up what Lee was putting down and used that as a sort of template for what writer/critic Evan Narcisse called “the New Black Absurdity” has helped its mode of attack feel remarkably familiar,. You can see its legacy in everything from the cinema du Afro-punk to Atlanta, Terence Nance’s unclassifiable surreality to Sorry to Bother You. Even Spike himself would go back to this bitter aesthetic well with BlacKkKlansman.

It’s plus ça change perversity of it all — the constant sheer WTF-edness and creeping feeling of progress being undone by violence and oppression — re: life circa 2020 that really makes Bamboozled feel like it was made for here and now. It’s time has come, wonderfully and regrettably. Reached by phone a few days after the DVD’s release, Clark noted that “in 2000, when this film came out, it was: ‘Spike, we know blackface is bad, get over it.’ If this had come out in 2008, it would have been received even worse: ‘Spike, we live in post-racial America now, you’re so out of touch.’ Right now, we have a President tweeting out miracle cures, people like Sheriff David A. Clarke considered to be pundits and the Diamond and Silk appearing on Fox. The really scary thing is that, 20 years on, Bamboozled feels incredibly contemporary. It doesn’t look so extreme after all…and when you consider the content of this film, that’s a very troubling thing.”

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A view of the famous Paris attractions and the city’s most picturesque streets. Today I’ll share some of the most famous streets, avenues, and boulevards in the French capital to help you learn about the streets that made Paris what it is!

The French capital is one of the most striking examples of rational urban planning conducted in the middle of the nineteenth century during the “Second Empire” of Napoleon III to ease congestion in the dense network of medieval streets…

Please follow link for full post

LOUIS MARIE DE SCHRYVER,Pierre Bonnard,Gustave Caillebotte,Antoine Blanchard,Edouard Henri Leon Cortès,EUGENE GALIEN LALOUE,Paris, Streets, France, Zaidan, biography, Art, Paintings, Artists, History, footnotes, fine art, fine art, Café,

27 Paintings of Parisian Street Scenes by the Artists of the time, 19 Century, with footnotes #2

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

PRISON de Gabriel Fauré, Feat Archie SHEPP / Marion Rampal & Pierre-François Blanchard LE SECRET

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Aeronauts

Un film di Tom Harper, con Felicity Jones e Eddie Redmayne

Disponibile in streaming su Amazon Prime Video

«Io credo in cielo ci siano le risposte, è lassù che ho provato la felicità più grande»

Anno 1862, incontriamo i protagonisti Amelia e James pochi minuti prima che taglino gli ancoraggi e, davanti a una folla festante, si innalzino nel cielo di Londra a bordo di un pallone, per battere il record di altitudine mai raggiunta da un uomo e una donna.

The Aeronauts, in cui troviamo riunita la brillante coppia formata da Eddie Redmayne e Felicity Jones del film La Teoria del Tutto, è un'opera di fantasia tratta dal libro Falling Upwards: How We Took to the Air di Richard Holmes che narra le grandi sfide degli aeronauti che sfidarono i cieli nella seconda metà dell'Ottocento a bordo di palloni pieni di aria calda.

La protagonista Amelia Rennes, a cui presta volto e bravura Felicity Jones, è ispirata principalmente alla figura della francese Sophie Blanchard e di altre donne pioniere che solcarono le nuvole in quell'epoca, mentre il personaggio interpretato da Eddie Redmayne, invece, è ricalcato sullo scienziato realmente esistito James Glaisher, il quale fu il primo uomo a salire a più di ottomila metri di altitudine senza ossigeno e aiutò a fondare la meteorologia contemporanea, intesa come previsione delle condizioni meteo.

Tornando alla trama del film, all'inizio i due protagonisti non sembrano starsi simpatici come già visto in un'infinita serie di cliché cinematografici, lei è un'avventuriera che scalda il pubblico con trucchi da circense mentre lui è il giovane scienziato serioso che vorrebbe essere preso sul serio; fortunatamente però ben presto i battibecchi tra lui e lei lasciano il posto alla collaborazione dettata dall'urgenza di sopravvivere!

Mentre il loro pallone si allontana da terra, è uno spettacolo per gli occhi e per la mente vedere la città ottocentesca dall'alto, accuratamente ricreata digitalmente, e pensare quale sensazione potrebbe nascere in noi ritrovandoci per la prima volta dentro e sopra le nuvole, anche se tutto ciò che vediamo è stato girato su schermo verde e per noi è normalità poter scrutare le nubi dall'alto a bordo di un economico aereo.

Attraverso una serie non sempre ben incasellata di flashback capiamo un pò di più di queste due persone: James Glaisher è lo zimbello della Royal Society e una delusione per i genitori orologiai per via del suo sogno di poter predire i cambiamenti meteorologici, mentre Amelia, dietro la facciata spavalda, è una vedova tormentata dalla perdita del marito Pierre, anch'egli aviatore, morto proprio per essere precipitato durante una spedizione salvandole la vita.

Sebbene il suo ruolo di donna intrepida e dominante sia di gusto contemporaneo e il suo personaggio di fantasia, perché il vero partner di volo di Glaisher fu un uomo di nome Henry Coxwell, che nel film non viene nemmeno nominato, Felicity Jones tiene in piedi il film per la maggior parte del tempo grazie al proprio carisma e riesce a rendere la sua Amelia credibile attraverso emozione e disperazione.

Indubbiamente Eddie Redmayne è l'attore giusto per il ruolo di coprotagonista in questa vicenda, quasi a rappresentare l'individuo più debole e fragile tra i due, in un rovesciamento della visione vittoriana di uomo e donna.

Trovo che lui tenda a fare sempre un pò lo stesso personaggio, timido e smarrito, ma credo proprio che il passare del tempo sul suo volto lo costringerà a cercare parti diverse in futuro.

Una delle ragioni per realizzare una pellicola del genere è proprio il senso poetico e lontano che un'impresa pionieristica del genere può suscitare nelle nostre vite moderne, in cui i raggiungimenti scientifici di uomini e donne di quei tempi sono talmente acquisiti da apparirci inverosimili.

E anche grazie a loro "chissà come si faceva quando non c'erano le previsioni meteo" è soltanto una domanda assurda che ci balena fugace in testa, prima di chiedere che tempo fa ad un altoparlante in salotto senza nemmeno gettare uno sguardo fuori dalla finestra.

Il regista, l'inglese Tom Harper, è conosciuto per aver diretto episodi delle serie TV Misfits e Peaky Blinders, oltre che la versione 2016 della miniserie Guerra & Pace.

E' la prima volta, credo, che mi trovo a scrivere di un film che arriva in Italia non al cinema ma esclusivamente on demand su di un servizio streaming, in questo caso l'ormai diffusissimo Prime Video di Amazon.

Anche se in maniera più blanda e meno tensiva, alcune sequenze di The Aeronauts, in cui ci si chiede se i protagonisti riusciranno a tornare a terra vivi, mi hanno fatto pensare a una versione di Gravity in mongolfiera.

Quel film però era stato pensato e realizzato per esser vissuto come un'esperienza immersiva (e in 3D) all'interno di una sala cinematografica, e infatti all'uscita dal cinema mi ero sentito centrifugato come se fossi appena atterrato da un modulo spaziale; The Aeronauts invece è stato immesso sul nostro mercato in modo da essere fruito comodamente dal divano sulla TV di casa e con la possibilità di interromperne la visione per preparare una tazza di latte caldo: credo proprio che anche l'impresa avventurosa narrata in questo film sarebbe stata percepita meglio, in proporzione, sul grande schermo.

The Aeronauts può essere il film perfetto per una ideale breve fuga dall'atmosfera tutta pranzi e cene delle feste natalizie, e una valida alternativa casalinga ai campioni d'incassi al cinema.

0 notes