#phrenology IS a pseudoscience

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

the brain doesn't stop developing at 25, that's not a magic number. that idea is a misconception. look it up.

#i'm not reblogging the popular post correcting this misconception going around#because it includes ANOTHER piece of misinformation in it!#they claim that this idea is 'phrenology' which it is not.#phrenology IS a pseudoscience#but this pseudoscience isn't phrenology#the truth is your brain continues to change and develop throughout adulthood in a myriad of ways#and that everyone including children deserve rights and agency

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 19th century saw an explosion of scientific discovery — people like Pasteur, Darwin, Curie, Mendel, and Kelvin expanded the frontiers of human knowledge. But not every scientific advance was actually an advance.

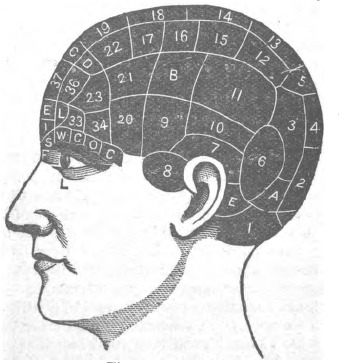

Take phrenology, the “science” of measuring the bumps and ridges on people’s skulls. It was seen as a key to understanding yourself and others. It was very trendy; Queen Victoria had her kids’ skulls read by a phrenologist.

Even after it was debunked, phrenology stuck around in zombie form. Various charlatans marketed courses and devices that promised to unlock the truth about people that was encoded into the shape of their skulls.

This week, a look at the strange history of this pseudoscience and its impact on people’s lives:

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

TikTok "Face reading" actually is that deep, and you should be critical of it

What do we THINK is the outcome of believing that an aspect of someones appearance makes someone better or worse than other people? Do we really have to be TOLD that's bad??

Let's think critically what the implications of a belief system that tells you your appearance affects who you are as a person are. I can't believe that people seriously need to be told "assigning morality to someones appearance is bad"

What do you think the history of a practice that uses facial features to determine intelligence and morality might be? Its bad, it's like really fucking bad guys.

There is NO feature on a person's face that can indicate whether they are a good and a bad person.

There is an entire video essay on this please check it out because, to the surprise of no one, the belief that certain peoples appearance = bad actually, has a racist history.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

To weigh in on recent controversy on this website:

Phrenology would at least be a more entertaining pseudoscience if it had people Bonsai Kittening their children's heads because they were told that having a big protruding lump above the left eyebrow would make the kid a better trombonist or whatever. Still morally indefensible and objectively harmful to everyone exposed to it, but at least horrifyingly and dangerously wrong in a respectably deranged way. But instead it's exclusively used as an excuse to be racist, which is evil in a cliche, overdone, and boring way.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Bernard Lane

Published: Mar 25, 2024

The dramatic growth of gender medicine clinics around the world would have been unthinkable without the promise of puberty blockers. Children born in the wrong body could simply pause the wrong puberty. And if their self-declared transgender identity proved wrong, it was a simple matter of unpausing natural development. Or so we were told. But now, England’s National Health Service (NHS) has announced an end to puberty blockers as a routine treatment for young people who are distressed about their gender, arguing that the balance between the benefits and harms of this medical intervention cannot be known because the evidence base for blockers is too weak and uncertain.

The impact of England’s decision has been reflected in recent editorials in The New York Post and The Times of London. The Post calls puberty blockers “deadly junk science,” while The Times has declared them “a medical scandal of the first order, a reckless exercise in 21st-century quackery,” explaining:

The case for puberty blockers was that they allowed troubled children to pause while coming to terms with their gender identity. These hormone inhibitors were characterised as an on-off switch that could be flicked with impunity. This was a startling example of medical arrogance.

Gender clinics from Stockholm to San Francisco, from Florence to Melbourne, have been running an uncontrolled experiment on children, while cloaked in the mantle of human rights and denouncing any critics as hateful bigots. It will take time to understand the implications of this experiment. Even those gender clinicians who sold blockers as safe have generally acknowledged one dangerous side-effect: low bone density. Hormone-suppressed teenagers are unlikely to get full benefit of the surge in bone mass that comes with puberty; as a result, they may be prematurely exposed to the brittle bones and fractures normally seen in the elderly. And there is another lesser known but potentially more profound risk: the effects of blockers on the brain.

The NHS decision to ban blockers rested heavily on a 2022 interim report by paediatrician Hilary Cass, who has led an independent review of gender dysphoria care. In her report, she writes,

It is known that adolescence is a period of significant changes in brain structure, function and connectivity. Animal research suggests that this development is partially driven by the [natural] pubertal sex hormones, but it is unclear whether the same is true in humans. If pubertal sex hormones are essential to these brain maturation processes, this raises a secondary question of whether there is a critical time window for the processes to take place, or whether catch up is possible when [cross-sex] oestrogen or testosterone is introduced later.

This question is not new. In 2006, Dutch clinicians, who had pioneered the off-label use of puberty blockers for gender dysphoria—these drugs had previously been used for other, distinct conditions—stated that, “It is not clear yet how pubertal suppression will influence brain development."

There was talk of a study to elucidate this, but it was never carried out. Despite this, by 2016, a key Dutch clinician was claiming that puberty blockers were “completely reversible.”

And this was the slogan picked up by gender clinics around the world as they adopted the puberty blocker-driven “Dutch protocol” for paediatric gender transition. A crucial unknown had been memory-holed.

Puberty blockers came to be seen as a low risk, no regrets option in the popular press, too. In 2015, men’s fashion magazine GQ ran a transgender zeitgeist article, featuring former Olympic athlete Bruce-turned-Caitlyn Jenner, “a beautiful, stylish lady.” The article cites Jenner’s fellow ex-Olympian, the gymnast-turned-doctor Michelle Telfer, who explains to readers that the onset of puberty intensifies the distress of gender dysphoria:

At that point we can start someone on puberty blockers. They don’t stop growth generally, or your brain from maturing emotionally and cognitively, they just stop the sexual characteristics from developing.

Dr Telfer is an adolescent medicine physician. In 2012, she took charge of the gender clinic at the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne (RCH) which, under her direction, went from 18 new referrals in her first year to 821 in 2021. What were young patients at her clinic told about blockers and the brain? It is unclear. Neither the hospital nor Dr Telfer, who is now chief of medicine at RCH, have responded to my emails asking them to clarify this.

In 2022, however, the hospital did acknowledge that the effects of pubertal suppression on the brain are unknown, though it did so not in a public statement correcting the record, but in a gender clinic newsletter, which it sent out to patients and families alerting them to future recruitment of subjects for a new study of the effects of blockers on the brain. The newsletter states:

During adolescence, the brain changes considerably. However, it is unclear whether the hormonal changes of puberty help to promote these changes or if this development occurs independent of our hormones. Related to this, we do not know whether using puberty blockers affects development of the brain.

It is unclear, however, whether this new study will be robust or whether it will be yet another “gender-affirming” study whose weak design makes it impossible to deduce any clear findings. It is also unclear whether the consent information the clinic provides to its patients and their parents today provides a candid acknowledgement of the cognitive unknowns associated with blockers.

The clinic’s gender dysphoria treatment guidelines were initially issued in 2018 by Dr Telfer and her RCH gender clinic colleagues. The Lancet lauded them as the first such guidelines specifically for children and adolescents. They include the claim that puberty suppression allows the young patient “time to develop emotionally and cognitively prior to making decisions on gender-affirming hormone use which [has] some irreversible effects.” That reassuring statement remains in the current iteration (version 1.4) of the RCH guidelines.

(The statement is also found in the hospital’s 2019 guide to fertility preservation for cancer and gender patients, accompanied by jarringly activist language that defies the normal understanding of biology. For example, the hospital advises “men”—meaning, females who identify as male—“to use contraception if they have a male partner” and states that “According to [government] Medicare data, >60 men give birth per year in Australia.”)

More relevant is the fact that administration of early puberty blockers followed by cross-sex hormones is likely to lead to sterilisation, sexual dysfunction, and lifelong status as a medical patient with symptoms that may puzzle mainstream doctors. Yet our popular culture has been bombarded with the largely unchallenged story that puberty blockers may save lives and that, if not, they have the virtue of being reversible. By uncritically repeating this and other contentious claims, Australia’s public broadcaster, the ABC, has served as an unpaid publicist for the gender clinics. For example, the popular ABC programme Australian Story recently featured an emotive profile of Dr Telfer, in which she repeats a claim she made on another high-profile ABC platform, Four Corners:

Puberty blockers are reversible. The only risk is that it can affect your bone density.

Such a claim would surprise anyone familiar with the state of the evidence base.

Few researchers know the scientific literature better than Mikael Landén, a psychiatrist affiliated with Sweden’s Karolinska Institute and the University of Gothenburg. Earlier this month, the journal Acta Paediatrica published his signed editorial under the title “Puberty suppression of children with gender dysphoria: Urgent call for research.” In it, Landén makes the point that,

Unfortunately, the discourse surrounding the use of puberty blockers in gender dysphoria is often framed as a political human rights issue rather than as a medical issue. There is a prevailing assertion that puberty blockers are lifesaving, fully reversible, and always safe. Even though that would place gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists [GnRHa or puberty blockers] in a unique and unlikely category—there are no other known drugs that simultaneously meet these criteria—any effort to shed light on the balance between the benefits and risks of [this] treatment is misconstrued as an attack on the LGBTQ+ community.

The same journal issue also features a paper by neuropsychologist Sallie Baxendale on the scientific literature dealing with hormone suppression and the brain.

Baxendale’s paper had previously been rejected by three other journals—not because of any fault with the science, but because anonymous reviewers were uncomfortable with its findings, which suggest that there is little evidence to support the benefits of puberty blockers. Baxendale, who holds a chair in neuropsychology at University College London, elsewhere relates her surprise at the politicised reactions her paper provoked:

the most astonishing response I received was from a reviewer who was concerned that I appeared to be approaching the topic from a ‘bias’ of heavy caution. This reviewer argued that lots of things needed to be sorted out before a clear case for the ‘riskiness’ of puberty blockers could be made, even circumstantially. Indeed, they appeared to be advocating for a default position of assuming medical treatments are safe, until proven otherwise.

Professor Baxendale was also unsettled by the paucity of convincing scientific literature on the benefits of puberty blockers:

I was surprised at just how little, and how low quality, the evidence was in this field. I was also concerned that clinicians working in gender medicine continue to describe the impacts of puberty blockers as ‘completely physically reversible’, when it is clear that we just don’t know whether this is the case, at least with respect to the cognitive impact.

These are observations that should give any serious gender clinic pause.

Professor Baxendale is particularly concerned that not enough is known about the neurological effects of puberty blockers for children and their parents to make an informed decision about their pros and cons. She writes:

Vague hints from poor quality studies are insufficient to allow people considering these [hormone suppression] treatments to make an informed decision regarding the possible impact on their neuropsychological function. Critical questions remain unanswered regarding the nature, extent and permanence of any arrested development of cognitive function that may be associated with pharmacological blocking of puberty. If cognitive development ‘catches up’ following the discontinuation of puberty suppression, how long does this take and is the recovery complete? While there is some evidence that indicates pubertal suppression may impact cognitive function, there is no evidence to date to support the oft-cited assertion that the effects of puberty blockers are fully reversible. Indeed, the only study to date that has addressed this in sheep suggests that this is not the case.

These concerns are shared by Professor Landén, who was the corresponding author for the paper describing Sweden’s systematic review of the evidence for the benefits of hormonal treatment for gender dysphoria. In that paper, Landén writes:

Against the background of almost non-existent longterm data, we conclude that GnRHa [or puberty blocker] treatment in children with gender dysphoria should be considered experimental treatment rather than standard procedure. This is to say that treatment should only be administered in the context of a clinical trial under informed consent.

As Landén has pointed out, it cannot be considered “anti-trans” to scrutinise the evidence base for puberty blockers. Far from a risk-free way to pause an unwanted puberty, these drugs are a potentially hazardous treatment promoted by politicised medical societies and ideologically driven lobby groups. We should heed his warning:

Insisting that [puberty blocker] treatment should not be evaluated using the same rigorous criteria as other medical treatments will ultimately harm patients with gender dysphoria. The view that conducting a thorough assessment of the impacts and potential side effects of [puberty blocker] treatment is offensive, obstructs individuals with gender dysphoria from accessing treatment supported by the level of evidence expected for any other patient group. Instead, the ethical imperative to safeguard our youth demands nothing less than a concerted effort to shed light on potential cognitive and other side effects of [puberty blockers]. The outcome of such research might demonstrate significant benefits with negligible risks, or conversely, that the risks outweigh the benefits. These are empirical questions that require careful investigation. Regardless of the outcome of such investigations, it is essential to ensure that the treatment of children with gender dysphoria maintains the same standard of evidence as any other medical treatment for children. Settling for anything less would amount to discrimination based on ideology.

#Bernard Lane#puberty blockers#gender affirming care#gender affirming healthcare#gender affirmation#medical scandal#medical malpractice#medical corruption#gender identity ideology#gender ideology#queer theory#intersectional feminism#gender pseudoscience#gender lobotomy#gender phrenology#gender thalidomide#religion is a mental illness

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

"You don't believe in scrupulousity? You're a denialist!"

"You're also a denialist of humor theory, phrenology, female hysteria, drapetomania, the effectiveness of lobotomies, and the vast majority of medical concepts that have ever been proposed."

#Pseudoscience#scientific denialism#Scrupulosity#scrupulosity isn't real#Scrupulosity is not real#Scrupulosity doesn't exist#Scrupulosity does not exist#Scrupulosity is a lie#humor theory#phrenology#female hysteria#drapetomania#lobotomy#lobotomies#pseudomedicine#quack#quacks#quackery

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

What in the world is this post trying to say

#Science isn't perfect but like there is a universe of a difference between phrenology and nutrition#And astrology is obviously pseudoscience. Obviously. We all know this.#Science is a human endeavor but you can just say that. What is this post#T#Also what do tech startups have to do with science who is claiming that

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Y'know those things where you've sort of heard there's some problems but it's not until you randomly stumble across a deeper dive that you really realize the scale of the situation?

Anyway I just found out that some tiktok influencers are peddling just, literal physiognomy

#like I'd seen the angel/witch skull graphic going around with people being like. tiktok this is just phrenology#but i didn't realize there was like. whole streams of content about ''''face reading'''' like dear god#this is like some foundational racial pseudoscience please don't#platextsofmemories

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Ryan Ruffaner

Published: Aug 10, 2023

Most research on demographic diversity in the workplace revolves around the diversity of age, sex, race and ethnicity. The scientific literature calls these differences “surface-level diversity” because they are immediately observable, biological in nature, and generally immutable. Some people believe these characteristics are reasonable proxies for underlying psychological characteristics and in some cases this may be true. For example, older people tend to feel more satisfied with their lives than their younger counterparts, and women tend to rank higher than men on the personality trait of agreeableness. However, given the huge variation within individual psychology, there are also many instances where you can’t judge a book by its cover.

Furthermore, not all diversity research is equally valuable. For example, some of the literature on surface-level diversity includes organizational tenure and functional background in the same category as age, sex, and race/ethnicity. This is a mistake. It is not possible to determine how long someone has worked in an organization just by looking at them, especially considering how frequently many people move between jobs and companies these days. Nor is it possible to guess a person’s functional background in this way—a uniform can be worn and removed, but this is not possible with age, sex, race, or ethnicity. Functional background is more closely related to deep-level diversity, not surface-level diversity, because it influences characteristics like opinions, beliefs, attitudes, and values more than our age, sex, or race/ethnicity.

Why does this matter? Because including deep-level variables in experiments designed to measure the effects of surface-level variables like diversity in age, sex, race, and ethnicity inevitably skews the results. For example, an academic article’s abstract may say that surface-level diversity is positively correlated with team performance. Activists and media outlets may therefore assume that the variables responsible for this correlation are sex, age, or race and ethnicity, and encourage race- and sex-based hiring/promotions. In fact, it may be that diversity of organizational tenure (mixing seasoned professionals with newer people with fresh perspectives, and vice versa) or functional background was responsible for higher performance. Consequently, we must treat diversity research with caution.

The research that focuses purely on true surface-level diversity isn’t much better. As David A. Harrison, Kenneth H. Price, and Myrtle P. Bell point out in their literature review and experiment on these two types of diversity (more on this later), the effects of commonly studied surface-level diversity characteristics have been inconsistent across studies, and even within studies. In fact, the findings of surface-level diversity studies have been so inconsistent that they differ on whether or not surface-level diversity has any effect on other variables. Some studies even show that surface-level diversity has negative impacts on factors like organizational commitment and job satisfaction, while others show a positive impact. Curiously, these inconsistencies are particularly strong on the effects of race and sex, the two variables that people tend to be most vocal about.

Harrison et al. suggest that some of this inconsistency may arise from the mistaken belief that demographic differences among employees are highly related to differences in attitudes. They are not. There is no correlation between a person’s race, ethnicity, age, and sex and their attitudes. People of diverse races, ethnicities, ages, and sexes can vary in their opinions, their values, their beliefs, their hobbies, and their priorities. And yet, the diversity train keeps chugging along. Why?

Part of this comes from America’s history of discrimination, particularly along the lines of race and sex. The Emancipation Proclamation sought to correct some of this historical injustice, which the Civil Rights movement and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 sought to further rectify. And because America’s past discrimination was mostly justified with reference to citizens’ surface-level differences, these have been the overwhelming focus of the diversity movement. The problem is that modern diversity initiatives seem to be driven, at least implicitly, by two hypotheses with which many DEI advocates are unfamiliar: the similarity-attraction paradigm and the contact hypothesis.

The similarity-attraction paradigm holds that the more similar we perceive other people to be to ourselves, the more attracted to them we’ll be. However, it is wrong to assume that important similarities are only skin-deep. Before designing their experiment, Harrison et al. conducted a literature review on theoretical perspectives from the fields of organizational behavior, sociology, and social psychology. They found support for the idea that while we initially categorize people based on stereotypes, we modify or replace these stereotypes with “deeper-level knowledge” of these people’s psychological qualities once we get to know them better.

The similarity-attraction paradigm also holds that “similarity in attitudes is a major source of attraction between individuals.” Not race, not ethnicity, not sex, and not age. So, while it’s true that we may use a variety of physical, social, and status traits to try to infer similar attitudes, beliefs, or personality traits in other people, our superficial judgements don’t stay superficial for long. As Byrne and Wong remark in their 1962 study, “subjects initially perceived greater attitudinal dissimilarity between themselves and a stranger of another race,” but when these same subjects learned more about these stranger’s attitudes, “perceptions of attitudinal dissimilarity decreased and interpersonal attraction to the stranger increased.”

Other researchers have found the same thing: over time, as people acquire more information, their perceptions become based more on observed behavior and less on the stereotypes they infer from overt characteristics. In other words, simply spending time together, rather than diversity training, is the catalyst for resolving surface-level diversity conflict. This makes sense when you think about it. Whenever diverse Americans went to war against a common enemy and had to rely on each other to survive and succeed, they came to love and respect each other naturally, regardless of their age, race, ethnicity, or sex. No diversity training was needed.

This feeds into the contact hypothesis, which holds that interpersonal contact between groups can reduce prejudice. This may explain some of the well-intentioned pushes for surface-level diversity as well. Diversity activists may believe that diversity initiatives in every organization will encourage interpersonal contact across groups and diminish intergroup prejudice (even though racial relations have never been better). But this demonstrates an incomplete understanding of the contact hypothesis, which only works if four conditions are met: equal status, common goals, cooperation, and institutional support. And under many diversity initiatives, these four conditions are not only unmet, they are actively sabotaged.

How can people engage under conditions of equal status and cooperative contact if they are taught, especially at a young age, that white people and men have an inherent advantage because of their race and sex? How can people engage in equal status and cooperative contact if they are taught that all white people are inherently racist, ignorant, or evil by virtue of their skin color or that all men are inherently sexist, domineering, and oppressive by virtue of their sex? How can people feel they have fair institutional support when diversity initiatives incessantly push for hiring and promoting people based on immutable surface-level traits, even going so far as to segregate workers into so-called “employee resource groups” based on race, ethnicity, sex, and sexuality?

DEI initiatives that teach people you can judge the content of a person’s character by the color of their skin, their ethnicity, their sex, or other immutable characteristics, are an affront to both morality and science. The science shows that it is our deep-level differences or similarities that truly matter, and we cannot derive one from the other. Scientific research on diversity supports the importance of deep-level similarities, especially in attitudes. As Harrison et al. point out, “the few studies that have examined the consequences of similarity in attitudes and values in work groups” found that the more similar supervisors and their subordinates were in their attitudes and values, the higher the supervisors rated their subordinates on performance reviews, regardless of age or education, and the more accurately they rated their peers.

Harrison et al. also cite other studies that found similarity in attitudes to be associated with higher group cohesiveness. Perceptions of attitude similarity, meanwhile, were “uniquely and positively related to subordinates’ satisfaction, performance ratings, and pay ratings,” meaning that no other factors could explain the positive relationship between attitude similarity and these other variables. This shouldn’t be too surprising because attitude similarity is one of the most important predictors of attraction and friendship in general, and there’s no reason to think it would be any different in the workplace.

Harrison et al. point out that when people share the same attitudes, they tend to fight less and communicate more, which reduces stress and leads to lower role conflict and role ambiguity. In their study, they collected two samples from two very different workplaces. One sample included 39 groups of people in a medium-sized hospital for a total of 443 people, and the other included 32 groups of people working in the deli-bakery sections of a regional grocery store chain with an average of 13 people per group. For surface-level diversity variables, they measured the participants’ age, sex, race, and ethnicity. For deep-level diversity variables, they measured each employee’s overall job satisfaction, supervisory satisfaction, work satisfaction, organizational commitment, time spent in their groups, and group cohesiveness (how “psychologically linked or attracted” group members feel toward “interacting with one another in pursuit of a common objective”).

The results of this study reveal a truth that contradicts the current diversity narrative pervading the United States: the longer group members work together, the less impact surface-level diversity has on how well they work, and the more deep-level diversity matters. Contrary to what many diversity activists claim, for both groups of employees, it is not the diversity of race, ethnicity, sex, or age that matters, it is the opportunities for team members to engage in meaningful interactions with each other over time.

The authors’ preliminary analysis undercut the importance of surface-level variables too. They found:

A significant correlation between perceptions of personality differences and how committed the subjects were to their organization and how satisfied they were in their jobs.

A significant correlation between perceptions of differences in value and how satisfied the subjects were with their supervisors.

A significant correlation between perceived differences in interests and supervisor satisfaction and work satisfaction.

Group cohesiveness—how well the group works together—was significantly correlated with the subjects’ perceptions of differences in their personalities, values, and interests. The only criteria that did not significantly correlate with group cohesiveness were surface-level characteristics like age and ethnicity. This was especially true over time. The researchers found that deep-level diversity “has steadily stronger consequences for groups than demographic diversity as group members spend more time together.” They suggest it might not be time itself that matters, but information:

Demographic factors are often a poor surrogate for the deeper-level information people need to make accurate judgments about the similarity of attitudes among group members. Time merely allows more information to be conveyed. Indeed, it might be more appropriate to think of the richness of interactions as the conduit for information exchange (cf. Daft & Lengel, 1986).

The more time people spend together, the more opportunities they have to learn about each other, especially if they work interdependently on a variety of meaningful tasks. These exchanges “allow group members to learn deeper-level information about their psychological similarity to or dissimilarity from their coworkers, where before they would have used surface-level demographic data as information proxies.”

So, why haven’t we heard about all this before? And why hasn’t other research shown similar results? The answer, according to the authors, is simple. Previous research may have discovered different findings because previous researchers did not compare the “relative contributions of surface- and deep-level variables” with “rich interactions among group members.” In other words, diversity researchers were only looking skin-deep, so their conclusions were skin-deep. It may sound like a trite cliché, but what truly matters is on the inside and “the relevant deep-level variables . . . that bear directly on the fundamental purposes of the group”:

In a jazz band or a marketing team, the consensus on the value of creative freedom might be paramount. In a day care center, the critical values to share might deal with nurturance and patience.”

And in academia, we want to ensure that everyone is committed to freedom of inquiry, freedom and encouragement of honest and civil disagreement, and the value of critical thinking. It may not be as easy to measure as simply asking people what they believe, but it is a far better starting place than mistakenly using surface-level variables as proxies for deep-level characteristics as many DEI consultants, activists, and ideologues suggest.

If you’re thinking about hiring a diversity ��expert” to help your diverse teams function better, think again. Your employees don’t need help seeing their surface-level differences. They already notice them and they probably don’t care. Whatever conflict there is in your teams most likely has nothing to do with their surface-level traits, and if you call attention to it, you will simply reinforce surface-level divisions rather than creating deep-level harmony.

To make your diverse teams work well together, simply allow them to engage in meaningful, interdependent tasks, and give them plenty of time to get to know each other on a deeper level. It’s that simple.

==

"Diversity" is racism and sexism thinly veiled as virtue.

#Ryan Ruffaner#diversity#diversity equity and inclusion#equity#inclusion#DEI bureacracy#diversity training#DEI phrenology#pseudoscience#DEI pseudoscience#religion is a mental illness

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

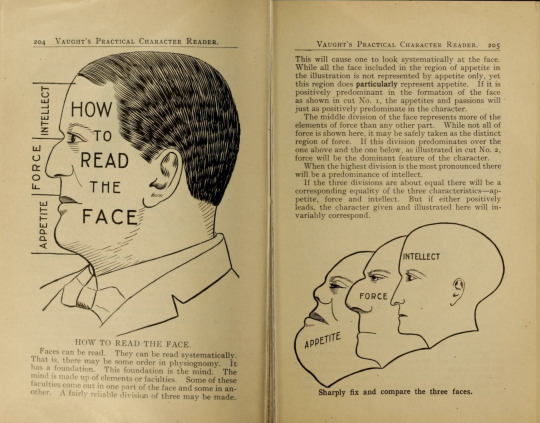

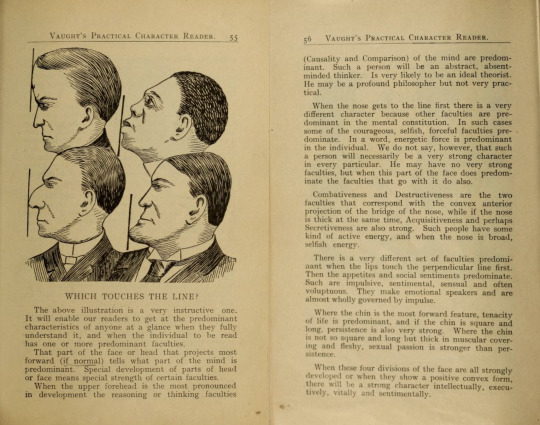

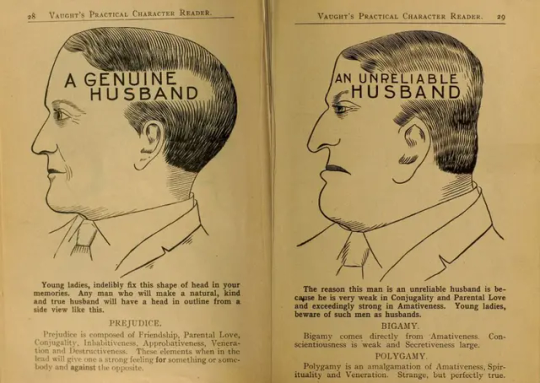

I pulled these from my phrenology lesson. Taken from Vaught’s Practical Character Reader by L. A. Vaught (1902).

We generally think of phrenology as a tool to analyze and "otherize" people of color, but white people (and especially people on the boundaries of whiteness) were very much fair game too.

the thing about Phrenology is, that people always talk about it as the skull measuring and head lump pseudoscience, but forget/leave out that large part of it was based on facial features. less people want to talk about that part, because on some level, most people really do think they can discern things about people based on their facial features.

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

starting conversations with people i haven't talked to in a long time by asking them what pseudoscience they would be

#so far people have answered phrenology astrology alchemy numerology#and i have said para psychology#feel free to tell me what pseudoscience you would be :)#🐌

1 note

·

View note

Text

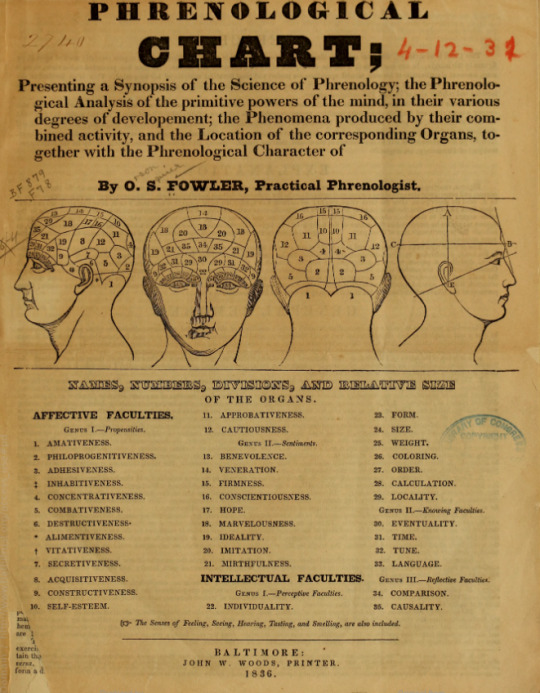

Phrenological Chart

By O.S. Fowler, "practical phrenologist".

Published Baltimore, USA, 1836

1 note

·

View note

Text

It is deeply, deeply beneficial to TERFs if the only characteristic of TERF ideology you will recognize as wrong, harmful, or problematic is "they hate trans women".

TERF ideology is an expansive network of extremely toxic ideas, and the more of them we accept and normalize, the easier it becomes for them to fly under the radar and recruit new TERFs. The closer they get to turning the tide against all trans people, trans women included.

Case in point: In 2014-2015, I fell headlong into radical feminism. I did not know it was called radical feminism at the time, but I also didn't know what was wrong with radical feminism in the first place. I didn't see a problem with it.

I was a year deep into this shit when people I had been following, listening to, and looking up to finally said they didn't think trans women were women. It was only then that I unfollowed those people, specifically; but I continued to follow other TERFs-who-didn't-say-they-were-TERFs. I continued ingesting and spreading their ideas- for years after.

If TERFs "only target trans women" and "only want trans women gone", if that's the one and only problem with their ideology and if that's the only way we'll define them, we will inevitably miss a vast majority of the quiet beliefs that support their much louder hatred of trans women.

As another example: the trans community stood relatively united when TERFs and conservatives targeted our right to use the correct restroom, citing the "dangers" of trans women sharing space with cis women. But when they began targeting Lost Little Girls and Confused Lesbians and trotting detransitioners out to raise a panic about trans men, virtually the only people speaking up about it were other transmascs. Now we see a rash of anti-trans healthcare bills being passed in the US, and they're hurting every single one of us.

When you refuse to call a TERF a TERF just because they didn't specifically say they hate trans women, when you refuse to think critically about a TERF belief just because it's not directly related to trans women, you are actively helping TERFs spread their influence and build credibility.

#all of this is very on point. hope you don't mind the screenshot#also hoping it doesn't come off as just self-congratulatory. this is really about the rest#i considered cropping the first and last tags but that felt dishonest#random aside and total change of subject. just autistic infodumping more than anything#the end reminds me of why i don't like calling race science social darwinism eugenics phrenology psychoanalysis etc 'pseudoscience'#like if you understand science from the idealized scientist's perspective of principled rigorous attempts to understand the world#though i'll of course note that perspective is very tied up in the politics of modernity#then sure. to modern science they are very much pseudoscience#with the caveats that 'psychoanalysis' covers a lot of things#and my understanding is for treating some anxiety disorders freudian methods are very effective and still pretty much the gold standard#(insert semi-relevant caveat about taxonomy and social construction of mental illness. yes my language is a bit clumsy and medical)#but you know the parts i'm talking about#but socially? these have been accepted science. they've affected culture. policy. direction of scientific research.#society and science at large in all sorts of ways!

66K notes

·

View notes