#peter smith-kingsley

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#the talented mr. ripley#anthony minghella#jack davenport#peter smith-kingsley#matt damon#tom ripley#movies

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

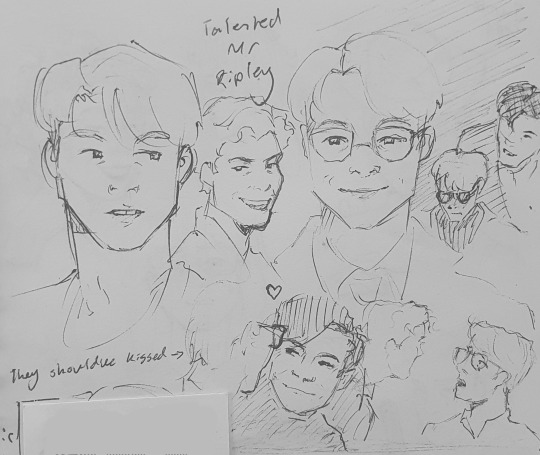

i find it so funny how in the movie peter just. has a resting bitch face. except for when it comes to tom

#the talented mr ripley#the talented mr. ripley#peter smith-kingsley#tom ripley#petom#patricia highsmith#anthony minghella#ttmr#the talented mr ripley fanart#crabs art

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

fan fiction got me to finish watching The Talented Mr. Ripley.

I think I stopped around the second murder. I was just like ehhhh I can't handle this & also I miss Dickie.

I think I was also frustrated with Tom Ripley containing so much sweet gayness & also sociopathic violence. I think I just imagined my mom or someone who's still kind of homophobic seeing the movie & going "Yup. I knew it! Gayness corrupts! Poor straight Jude Law. Ugh Tom Ripley is such a deranged gay."

I think it was my fear of someone thinking that the gayness & the derangedness/wrongness of Ripley went together that upset me.

so anyway! I stopped watching the movie & didn't think I would finish.

but then I couldn't sleep so was like "Hey I'll see if there's any good Ripley fanfic."

I expected lots of Tom/Dickie, but there was practically none of that! instead it was Peter Peter Peter.... "Who the heck is Peter???" I thought.

so I went back to the movie for Peter. & shit. I love him so so so much. just like. look at him in that last scene when he still thinks he's safe.

he's in his pyjamas so sweet & cozy looking over his music scores or whatev. & he's like softly heartbroken because he just saw Tom kissing a girl. & he's calling him out on it but he's more sad than angry. he thought they had something. legit 5 min ago Tom was telling him this is the happiest he's ever been....

anyway! the ending. fuck. fuck. fuck.

Tom kills his chance at happiness. he's alone in the dark place he hides all his secrets in. that scene is the most horrible thing ever. the way Peter never even gets angry-- just confused. even as it's happening he cannot conceive that Tom is doing it on purpose.

& the way Tom is crying! oh my god.

so. what do I think of this movie?

I don't even know anymore.

part of me is like Ahh this is potentially harmful for how people see gay people.

& another part of me is like Holy shit this shows how hiding yourself/your queerness/trying not to take up space as your true self is actually slowly killing you/disappearing you/destroying your love & all that is good in you... the magic needs fresh air or it curdles...

& also this story is so weird!! queer stories shouldn't have to be all happy & shiny & good....

so. ambivalent?

& for some reason-- utterly obsessed.

#the talented mr. ripley#matt damon#jude law#patricia highsmith#ppl who have read the book-- should i read it?#i've heard interviews with the author where she says ripley has no conscience. is it as simple as that? cuz honestly that sounds kinda#boring#but patricia highsmith is brilliant so#peter smith-kingsley#tom ripley#dickie greenleaf

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Is Tom Ripley gay? For nearly 70 years, the answer has bedeviled readers of Patricia Highsmith’s 1955 thriller The Talented Mr. Ripley, the story of a diffident but ambitious young man who slides into and then brutally ends the life of a wealthy American expatriate, as well as the four sequels she produced fitfully over the following 36 years. It has challenged the directors — French, British, German, Italian, Canadian, American — who have tried to bring Ripley to the screen, including in the latest adaptation by Steven Zaillian, now on Netflix. And it appears even to have flummoxed Ripley’s creator, a lesbian with a complicated relationship to queer sexuality. In a 1988 interview, shortly before she undertook writing the final installment of the series, Ripley Under Water, Highsmith seemed determined to dismiss the possibility. “I don’t think Ripley is gay,” she said — “adamantly,” in the characterization of her interviewer. “He appreciates good looks in other men, that’s true. But he’s married in later books. I’m not saying he’s very strong in the sex department. But he makes it in bed with his wife.”

The question isn’t a minor one. Ripley’s killing of Dickie Greenleaf — the most complicated, and because it’s so murkily motivated, the most deeply rattling of the many murders the character eventually commits — has always felt intertwined with his sexuality. Does Tom kill Dickie because he wants to be Dickie, because he wants what Dickie has, because he loves Dickie, because he knows what Dickie thinks of him, or because he can’t bear the fact that Dickie doesn’t love him? Ordinarily, I’m not a big fan of completely ignoring authorial intent, and I’m inclined to let novelists have the last word on factual information about their own creations. But Highsmith, a cantankerous alcoholic misanthrope who was long past her best days when she made that statement, may have forgotten, or wanted to disown, her own initial portrait of Tom Ripley, which is — especially considering the time in which it was written — perfumed with unmistakable implication.

Consider the case that Highsmith puts forward in The Talented Mr. Ripley. Tom, a single man, lives a hand-to-mouth existence in New York with a male roommate who is, ahem, a window dresser. Before that, he lived with an older man with some money and a controlling streak, a sugar daddy he contemptuously describes as “an old maid”; Tom still has the key to his apartment. Most of his social circle — the names he tosses around when introducing himself to Dickie — are gay men. The aunt who raised him, he bitterly recalls, once said of him, “Sissy! He’s a sissy from the ground up. Just like his father!” Tom, who compulsively rehearses his public interactions and just as compulsively relives his public humiliations, recalls a particularly stinging moment when he was shamed by a friend for a practiced line he liked to use repeatedly at parties: “I can’t make up my mind whether I like men or women, so I’m thinking of giving them both up.” It has “always been good for a laugh, the way he delivered it,” he thinks, while admitting to himself that “there was a lot of truth in it.” Fortunately, Tom has another go-to party trick. Still nurturing vague fantasies of becoming an actor, he knows how to delight a small room with a set of monologues he’s contrived. All of his signature characters are, by the way, women.

This was an extremely specific set of ornamentations for a male character in 1955, a time when homosexuality was beginning to show up with some frequency in novels but almost always as a central problem, menace, or tragedy rather than an incidental characteristic. And it culminates in a gruesome scene that Zaillian’s Ripley replicates to the last detail in the second of its eight episodes: The moment when Dickie, the louche playboy whose luxe permanent-vacation life in the Italian coastal town of Atrani with his girlfriend, Marge, has been infiltrated by Tom, discovers Tom alone in his bedroom, imitating him while dressed in his clothes. It is, in both Highsmith’s and Zaillian’s tellings, as mortifying for Tom as being caught in drag, because essentially it is drag but drag without exaggeration or wit, drag that is simply suffused with a desire either to become or to possess the object of one’s envy and adoration. It repulses Dickie, who takes it as a sexual threat and warns Tom, “I’m not queer,” then adds, lashingly, “Marge thinks you are.” In the novel, Tom reacts by going pale. He hotly denies it but not before feeling faint. “Nobody had ever said it outright to him,” Highsmith writes, “not in this way.” Not a single gay reader in the mid-1950s would have failed to recognize this as the dread of being found out, quickly disguised as the indignity of being misunderstood.

And it seemed to frighten Highsmith herself. In the second novel, Ripley Under Ground, published 15 years later, she backed away from her conception of Tom, leaping several years forward and turning him into a soigné country gentleman living a placid, idyllic life in France with an oblivious wife. None of the sequels approach the cold, challenging terror of the first novel — a challenge that has been met in different ways, each appropriate to their era, by the three filmmakers who have taken on The Talented Mr. Ripley. Zaillian’s ice-cold, diamond-hard Ripley just happens to be the first to deliver a full and uncompromising depiction of one of the most unnerving characters in American crime fiction.

The first Ripley adaptation, René Clément’s French-language drama Purple Noon, is much beloved for its sun-saturated atmosphere of endless indolence and for the tone of alienated ennui that anticipated much of the decade to come; the movie was also a showcase for its Ripley, the preposterously sexy, maddeningly aloof Alain Delon. And therein lies the problem: A Ripley who is preposterously sexy is not a Ripley who has ever had to deal with soul-deep humiliation, and a Ripley who is maddeningly aloof is not going to be able to worm his way into anyone’s life. Purple Noon is not especially willing (or able — it was released in 1960) to explore Ripley’s possible homosexuality. Though the movie itself suggests that no man or woman could fail to find him alluring, what we get with Delon is, in a way, a less complex character type, a gorgeous and magnetic smooth criminal who, as if even France had to succumb to the hoariest dictates of the Hollywood Production Code, gets the punishment due to him by the closing credits. It’s delectable daylit noir, but nothing unsettling lingers.

Anthony Minghella’s The Talented Mr. Ripley, released in 1999, is far better; it couldn’t be more different from the current Ripley, but it’s a legitimate reading that proves that Highsmith’s novel is complex and elastic enough to accommodate wildly varying interpretations. A committed Matt Damon makes a startlingly fine Tom Ripley, ingratiating and appealing but always just slightly inept or needy or wrong; Jude Law — peak Jude Law — is such an effortless golden boy that he manages the necessary task of making Damon’s Tom seem a bit dim and dull; and acting-era Gwyneth Paltrow is a spirited and touchingly vulnerable Marge.

Minghella grapples with Tom’s sexual orientation in an intelligently progressive-circa-1999 way; he assumes that Highsmith would have made Tom overtly gay if the culture of 1955 had allowed it, and he runs all the way with the idea. He gives us a Tom Ripley who is clearly, if not in love with Dickie, wildly destabilized by his attraction to him. And in a giant departure from the novel, he elevates a character Highsmith had barely developed, Peter Smith-Kingsley (played by Jack Davenport) into a major one, a man with whom we’re given to understand that Ripley, with two murders behind him and now embarking on a comfortable and well-funded European life, has fallen in love. It doesn’t end well for either of them. A heartsick Tom eventually kills Peter, too, rather than risk discovery — it’s his third murder, one more than in the novel — and we’re meant to take this as the tragedy of his life: That, having come into the one identity that could have made him truly happy (gay man), he will always have to subsume it to the identity he chose in order to get there (murderer). This is nowhere that Highsmith ever would have gone — and that’s fine, since all of these movies are not transcriptions but interpretations. It’s as if Minghella, wandering around inside the palace of the novel, decided to open doors Highsmith had left closed to see what might be behind them. The result is the most touching and sympathetic of Ripleys — and, as a result, far from the most frightening.

Zaillian is not especially interested in courting our sympathy. Working with the magnificent cinematographer Robert Elswit, who makes every black-and-white shot a stunning, tense, precise duel between light and shadow, he turns coastal Italy not into an azure utopia but into a daunting vertical maze, alternately paradise, purgatory, and inferno, in which Tom Ripley is forever struggling; no matter where he turns, he always seems to be at the bottom of yet another flight of stairs.

It’s part of the genius of this Ripley — and a measure of how deeply Zaillian has absorbed the book — that the biggest departures he makes from Highsmith somehow manage to bring his work closer to her scariest implications. There are a number of minor changes, but I want to talk about the big ones, the most striking of which is the aging of both Tom and Dickie. In the novel, they’re both clearly in their 20s — Tom is a young striver patching together an existence as a minor scam artist who steals mail and impersonates a collection agent, bilking guileless suckers out of just enough odd sums for him to get by, and Dickie is a rich man’s son whose father worries that he has extended his post-college jaunt to Europe well past its sowing-wild-oats expiration date. Those plot points all remain in place in the miniseries, but Andrew Scott, who plays Ripley, is 47, and Johnny Flynn, who plays Dickie, is 41; onscreen, they register, respectively, as about 40 and 35.

This changes everything we think we know about the characters from the first moments of episode one. As we watch Ripley in New York, dourly plying his miserable, penny-ante con from a tiny, barren shoe-box apartment that barely has room for a bed as wide as a prison cot (this is not a place to which Ripley has ever brought guests), we learn a lot: This Ripley is not a struggler but a loser. He’s been at this a very long time, and this is as far as he’s gotten. We can see, in an early scene set in a bank, that he’s wearily familiar with almost getting caught. If he ever had dreams, he probably buried them years earlier. And Dickie, as a golden boy, is pretty tarnished himself — he isn’t a wild young man but an already-past-his-prime disappointment, a dilettante living off of Daddy’s money while dabbling in painting (he’s not good at it) and stringing along a girlfriend who’s stuck on him but probably, in her heart, knows he isn’t likely to amount to much.

Making Tom older also allows Zaillian to mount a persuasive argument about his sexuality that hews closely to Highsmith’s vision (if not to her subsequent denial). If the Ripley of 1999 was gay, the Ripley of 2024 is something else: queer, in both the newest and the oldest senses of the word. Scott’s impeccable performance finds a thousand shades of moon-faced blankness in Ripley’s sociopathy, and Elswit’s endlessly inventive lighting of his minimal expressions, his small, ambivalent mouth and high, smooth forehead, often makes him look slightly uncanny, like a Daniel Clowes or Charles Burns drawing. Scott’s Ripley is a man who has to practice every vocal intonation, every smile or quizzical look, every interaction. If he ever had any sexual desire, he seems to have doused it long ago. “Is he queer? I don’t know,” Marge writes in a letter to Dickie (actually to Tom, now impersonating his murder victim). “I don’t think he’s normal enough to have any kind of sex life.” This, too, is from the novel, almost word for word, and Zaillian uses it as a north star. The Ripley he and Scott give us is indeed queer — he’s off, amiss, not quite right, and Marge knows it. (In the novel, she adds, “All right, he may not be queer [meaning gay]. He’s just a nothing, which is worse.”) Ripley’s possible asexuality — or more accurately, his revulsion at any kind of expressed sexuality — makes his killing of Dickie even more horrific because it robs us of lust as a possible explanation. This is the first adaptation of The Talented Mr. Ripley I’ve seen in which even Ripley may not know why he murders Dickie.

When I heard that Zaillian (who both wrote and directed all of the episodes) was working on a Ripley adaptation, I wondered if he might replace sexual identity, the great unequalizer of 1999, with economic inequity, a more of-the-moment choice. Minghella’s version played with the idea; every person and object and room and vista Damon’s Ripley encountered was so lush and beautiful and gleaming that it became, in some scenes, the story of a man driven mad by having his nose pressed up against the glass that separated him from a world of privilege (and from the people in that world who were openly contemptuous of his gaucheries). Zaillian doesn’t do that — a lucky thing, since the heavily Ripley-influenced film Saltburn played with those very tropes recently and effectively. Whether intentional or not, one side effect of his decision to shoot Ripley in black and white is that it slightly tamps down any temptation to turn Italy into an occasion for wealth porn and in turn to make Tom an eat-the-rich surrogate. This Italy looks gorgeous in its own way, but it’s also a world in which even the most beautiful treasures appear threatened by encroaching dampness or decay or rot. Zaillian gives us a Ripley who wants Dickie’s life of money and nice things and art (though what he’s thinking when he stares at all those Caravaggios is anybody’s guess). But he resists the temptation to make Dickie and Marge disdainful about Tom’s poverty, or mean to the servants, or anything that might make his killing more palatable. This Tom is not a class warrior any more than he’s a victim of the closet or anything else that would make him more explicable in contemporary terms. He’s his own thing — a universe of one.

Anyway, sexuality gives any Ripley adapter more to toy with than money does, and the way Zaillian uses it also plays effectively into another of his intuitive leaps — his decision to present Dickie’s friend and Tom’s instant nemesis Freddie Miles not as an obnoxious loudmouth pest (in Minghella’s movie, he was played superbly by a loutish Philip Seymour Hoffman) but as a frosty, sexually ambiguous, gender-fluid-before-it-was-a-term threat to Tom’s stability, excellently portrayed by Eliot Sumner (Sting’s kid), a nonbinary actor who brings perceptive to-the-manor-born disdain to Freddie’s interactions with Tom. They loathe each other on sight: Freddie instantly clocks Tom as a pathetic poser and possible closet case, and Tom, seeing in Freddie a man who seems to wear androgyny with entitlement and no self-consciousness, registers him as a danger, someone who can see too much, too clearly. This leads, of course, to murder and to a grisly flourish in the scene in which Tom, attempting to get rid of Freddie’s body, walks his upright corpse, his bloodied head hidden under a hat, along a street at night, pretending he’s holding up a drunken friend. When someone approaches, Tom, needing to make his possible alibi work, turns away, slamming his own body into Freddie’s up against a wall and kissing him passionately on the lips. That’s not in Highsmith’s novel, but I imagine it would have gotten at least a dry smile out of her; in Ripley’s eight hours, this necrophiliac interlude is Tom’s sole sexual interaction.

No adaptation of The Talented Mr. Ripley would work without a couple of macabre jokes like that, and Zaillian serves up some zesty ones, including an appearance by John Malkovich, the reigning king/queen of sexual ambiguity (and himself a past Ripley, in 2002’s Ripley’s Game), nodding to Tom’s future by playing a character who doesn’t show up until book two. He also gives us a witty final twist that suggests that Ripley may not even make it to that sequel, one that reminds us how fragile and easily upended his whole scheme has been. Because Ripley, in this conception, is no mastermind; Zaillian’s most daring and thoughtful move may have been the excision of the word “talented” from the title. In the course of the show, we see him toy with being an editor, a writer (all those letters!), a painter, an art appreciator, and a wealthy man, often convincingly — but always as an impersonation. He gives us a Tom who is fiercely determined but so drained of human affect when he’s not being watched that we come to realize that his only real skill is a knack for concentrating on one thing to the exclusion of everything else. What we watch him get away with may be the first thing in his life he’s really good at (and the last moment of the show suggests that really good may not be good enough). This is not a Tom with a brilliant plan but a Tom who just barely gets away with it, a Tom who can never relax.

Tom’s sexuality is ultimately an enigma that Zaillian chooses to leave unsolved — as it remains at the end of the novel. Highsmith’s decision to turn Tom into a roguish heterosexual with a taste for art fraud before the start of the second novel has never felt entirely persuasive, and it’s clearly a resolution in which Zaillian couldn’t be less interested. Toward the end of Ripley, Tom is asked by a detective to describe the kind of man Dickie was. He transforms Dickie’s suspicion about his queerness into a new narrative, telling the private investigator that Dickie was in love with him: “I told him I found him pathetic and that I wanted nothing more to do with him.” But it’s the crushing verdict he delivers just before that line that will stay with me, a moment in which Tom, almost in a reverie, might well be describing himself: “Everything about him was an act. He knew he was supremely untalented.” In the end, Scott and Zaillian give us a Ripley for an era in which evil is so often meted out by human automatons with even tempers and bland self-justification: He is methodical, ordinary, mild, and terrifying.'

#Andrew Scott#Ripley#Matt Damon#The Talented Mr Ripley#Anthony Minghella#Steven Zaillian#Purple Noon#Alain Delon#Johnny Flynn#Dickie Greenleaf#Peter Smith-Kingsley#Jude Law#Gwyneth Paltrow#Robert Elswit#Caravaggio#Marge Sherwood#Freddie Miles#Philip Seymour Hoffman#Eliot Sumner

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Posted this on Twitter first but might as well post on here too.

If they let me make a The Talented Mr Ripley adaptation this is who I’d cast!

#my twt username is filmdelon ermmm#yeah anyways i'm really passionate about this fancast like in my mind it's perfect#the talented mr. ripley#the talented mr ripley#tom ripley#dickie greenleaf#marge sheerwood#freddie miles#meredith logue#peter smith-kingsley#fancast#my edits#ig?'?#by me

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jack Davenport as Peter Smith-Kingsley THE TALENTED MR. RIPLEY (1999) dir. Anthony Minghella

#filmedit#ttmredit#perioddramaedit#the talented mr. ripley#jack davenport#peter smith kingsley#**#*gif#*ttmr#🙃

816 notes

·

View notes

Text

I absolutely love the ending of The Talented Mr Ripley.

I love that Tom was able to trust Peter enough to tell him about his past and I love that Peter basically said "Y'know what, I love you no matter what. You are smart, sexy, talented and Dickie and Freddie were kind of assholes, so they should've seen it coming." And the next day they watch the sunset on the boat together. And when Meredith shows up, Tom is all like "Hey, look who I found on the boat?" and Peter played along "Such a coincidence we were on this boat together, and yet Dickie and I have decided are getting married next month" and Meredith was all like "I can't blame either of you. Can I be maid of honour?" and she was and they lived happily ever after.

Truly a classic.

545 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ripley post RAHHHHH

#the talented mr. ripley#tom ripley#the talented mr ripley#matt damon#jude law#dickie greenleaf#peter smith kingsley#marge sherwood

192 notes

·

View notes

Text

i forgot to post this…. devastating!!! been really really busy recently hence the lack of art… :(

#ok yes and this is fic art for a monstrosity that’s been in my drafts for so long#cam art#fanart#the talented mr. ripley#tom ripley#peter smith kingsley#talented mr ripley#ok ok ok

629 notes

·

View notes

Text

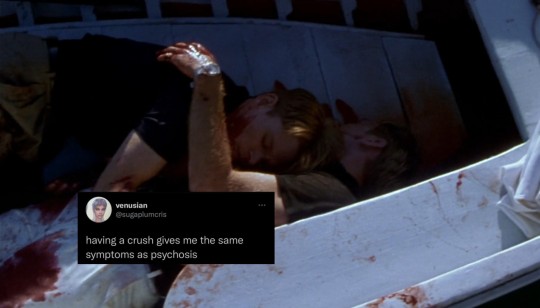

the talented mr. ripley + textposts pt. 2

part 1

ib this post

#the talented mr ripley#mine#tom ripley#films#movies#text posts#matt damon#dickie greenleaf#jude law#marge sherwood#gwenyth paltrow#peter smith kingsley#jack davenport#90s#90s movies

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

the talented mr. ripley (1999) x internet posts

#mine#the talented mr. ripley#tom ripley#peter smith kingsley#dickie greenleaf#marge sherwood#matt damon#jude law#jack davenport#films

344 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tom Ripley & Peter Smith-Kingsley 1999 • The Talented Mr. Ripley • dir. Anthony Minghella

#the talented mr. ripley#tom ripley#peter smith kingsley#perioddramaedit#filmedit#lgbtedit#gay couple#gay#lgbt#queer#anthony minghella#patricia highsmith#queer characters#1950s#film#movie#period drama#filmgifs#moviegifs#romancegifs#queer media#couple#affection#intimacy#longing#romantic

942 notes

·

View notes

Text

#the talented mr ripley#talented mr ripley#the talented mr. ripley#jett talks (me)#jett art (me)#tom ripley#peter smith kingsley

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

'WHO IS TOM RIPLEY? Steven Zaillian’s recent Netflix series adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s most infamous literary creation starts and ends on this question.

Ripley adapts the first of five books Highsmith dedicated to the exploits of the con artist–murderer-aesthete, and the portion of the story that has been reinterpreted the most: New York shipping magnate Herbert Greenleaf hires the low-level grifter to travel to Europe and convince his vagabond son Dickie (Johnny Flynn) to return to the United States. Highsmith’s novel is a masterwork of crime writing, and Ripley is a chameleonic figure who has been interpreted, alternately, as a charming sociopath, a consummate con man, and a serial killer. He has been played by actors of dizzyingly different registers like John Malkovich in Ripley’s Game (2002), Dennis Hopper in The American Friend (1977), Barry Pepper in Ripley Under Ground (2005), Alain Delon in Purple Noon (1960) and, perhaps most famously, Matt Damon in The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999).

Andrew Scott is the latest and proves to have the most insidiously perfect take on Ripley. The Irish actor, who will be recognizable to many as the “Hot Priest” from Fleabag (2016–19), as well as the maniacal, screeching Moriarty on Sherlock (2010–17), just picked up awards for his performance in the film All of Us Strangers (2023) and the play VANYA, a new reimagining of Anton Chekhov’s classic. There’s little that ties his Ripley to previous Ripleys: Damon’s was lovelorn; Malkovich made him cunning; Hopper, bombastic; Delon’s was mean-spirited; and Pepper, let’s just not. Scott, meanwhile, possesses a soft-featured handsomeness that can “mold into ordinariness” at will. This Ripley is a negative space. He observes and absorbs. Scott’s performance dispenses with charm and charisma almost entirely, in fact, and throughout Ripley’s eight episodes, the character is mostly uncomfortable, ill at ease, and clawing.

Significantly, Ripley is the first adaptation of Highsmith’s character to depict “the unequivocal triumph of evil over good” that she thought her book explored; certainly, it’s the only adaptation that finds Ripley “rejoicing in it.” Ripley will always win. But neither the book nor the series gives us anything to hold on to. There is nothing to root for. Zaillian and Scott’s narrative, visual, and performance choices empty out Ripley of the charm and emotionality that drove previous adaptations. Here, Ripley is a slippery mask that doesn’t ever quite fit right. And in embracing the character’s elusiveness and refusing to make his emptiness attractive, Zaillian and Scott have given us the definitive on-screen Tom Ripley.

How to film a vacuum of personhood? Zaillian told Vanity Fair that the choice to film Ripley in black-and-white came to him early in the process, and was inspired, in part, by the black-and-white edition of the Ripley book he had on his desk. “As I was writing,” he said, “I held that image in my mind.” The black-and-white imagery strips Ripley’s story of the postcard beauty we’ve come to expect from previous adaptations. While the golden cinematography of Purple Noon and The Talented Mr. Ripley capture the sandy ease of wealthy American expats enjoying bright negronis and crystalline seawater, Zaillian didn’t “want to make a pretty travelogue.” And pretty it is not. While there is much to praise about the moody monochrome cinematography, it doesn’t distract. Ripley’s New York is a rusty compilation of ugly details: the rotten wood of the window, exposed wire covered by a sad little painting of a boat, an overflowing shower, a musty slab of soap, the noise of other people’s bowel movements. When he arrives in Italy, the Mediterranean water is black and inhospitable. It’s a graveyard, not a postcard.

Ripley indulges in repetition and the administrative details of criminality. The paperwork, the travel, and the negotiations are granted much screen time. It’s tedious work, conning people. When we first meet Tom Ripley, he’s running a small-time mail fraud, and constantly looking over his shoulder. It’s his frustration with petty paperwork grifts, rather than any fascination with Europe or love of art, that makes him accept Herbert Greenleaf’s mission. But Ripley is a quick study: by the second episode, he’s got conversational Italian down, and he understands the unspoken rules of Dickie’s lifestyle. And he’s a hard worker. This Ripley practices. He has to, in order to maintain his cover. His forgeries are a craft, and he carries his tools—stamps, glue, a rubber goop to forge passports—with him.

Ripley’s foreignness aids him. In a 1989 essay for Granta, Patricia Highsmith recalled the image that became the genesis of Tom Ripley: a young man walking alone on the beach in Positano, Italy, early in the morning, who “looked like a thousand other American tourists in Europe that summer.” Highsmith never met that man, but the image grew and expanded into the famous character. An American in Europe, becoming acquainted with the ways of living in Italy, France, and Germany, just like Highsmith herself had done. Europe as a concept, not a destination. It was freedom. In the same essay, the author recalls a secret sort of affinity for Europe, one “so deep and important that I might not wish or need to discuss it with friend or family.” I wonder if Zaillian read this very essay. His Ripley, too, looks out at the tiny beach of Atrani, which looks similar to the Positano that Highsmith looked upon, and sees a faraway, solitary figure. In Ripley, people who interact briefly with either Ripley or Dickie see them as interchangeable, just two Americans. His foreignness, ironically, allows him to blend in.

Highsmith’s Ripley holds good taste above everything else, and so does Zaillian’s. Ripley’s lack of refinement is palpable at first. He makes all the wrong choices, sartorially and otherwise (in the film, it’s the lime-green Speedos; in the series, the paisley robe), which puts him on the wrong foot with Marge Sherwood and Freddie Miles. Played in the film by Gwyneth Paltrow cosplaying Housewives of Mongibello, and in the series by a po-faced Dakota Fanning, Marge is as desperately oblivious to her lack of talent as Dickie is. She spends her days scribbling away at a memoir about her experiences in Atrani (which Ripley edits in a delightful montage of disdain) and eyeing Ripley suspiciously. He and Marge find each other equally repellent: he is too “vague” for her to grasp (some light-coded homophobia there) and she is tacky (he throws away the hand-knit scarf she makes for Dickie). As the series progresses, he starts to build up a new persona, one that feels truer to him than “Tom Ripley”: “This was the real annihilation of his past and of himself, Tom Ripley, who was made up of that past, and his rebirth as a completely new person,” writes Highsmith. This new Tom Ripley is suave, well dressed, and well regarded, while Marge is condescended to by the Italian police and drinks too much at parties. And Dickie, well, he’s dead.

The murder of Dickie Greenleaf is a turning point for Ripley. It is his graduation from grifter to murderer and is one of the few constants of every interpretation of the text. In the book, it is semi-premeditated. Ripley conceives of this idea earlier, on the train (always the train with Highsmith), knowing that Dickie is going to politely excise him from his life, from his lifestyle: “He knew that he was going to do it, that he would not stop himself now, maybe couldn’t stop himself, and that he might not succeed,” writes Highsmith. The screen has always reinvented this moment for dramatic effect. In Purple Noon, Ripley stabs French Dickie (renamed Philippe Greenleaf, and portrayed by Maurice Ronet) in the heart, on Dickie’s own boat. A risky, impulsive decision. Ripley stages the murder as quietly rageful: neither man raises their voice, Dickie politely severs their relationship and Ripley’s bludgeoning of Dickie is wordless. He looks at Dickie’s ring, as if for confirmation to proceed before striking him in the head with the oar. It’s not about Dickie; it’s about his lifestyle, one that Ripley feels he deserves more than Dickie.

Anthony Minghella’s The Talented Mr. Ripley interprets this moment as an emotional and moral upheaval, with Ripley pushed over the edge by Dickie’s ferocious rant. Jude Law’s Dickie is a petulant child who wreaks havoc with his limited attention span and oversized charm. His first interaction (and last) interaction with Ripley is bullish: he mocks his untanned skin (“Did you ever see a guy so white, Marge?”), his lack of refinement, his inability to ski, his obvious worship of Dickie. He is violently repelled by Ripley’s desire to be close to him at all costs. So, when the oar strikes his head, we understand. He calls him a “leech,” a “third-class mooch,” and, most damningly in Dickie’s mind, “boring.”

And, in Damon’s hands, he kind of is. In a 1998 interview, the actor spoke about wanting Ripley’s “humanity to come across,” morphing him into someone who does not “ever manipulate anybody” and who “come[s] from a position of pure honesty all the time. He believes what’s happening and he believes the world he’s indulging in.” At this point in his career, Damon was always in the right place at the right time. Both he and Paltrow were Harvey Weinstein’s golden children. Damon, together with his co-writing buddy Ben Affleck, had just earned a best screenplay Oscar for Good Will Hunting (1997) and Paltrow had picked up her statuette for best actress in Shakespeare in Love (1998), both Miramax releases. It makes sense with Damon’s persona and limitations that he would interpret Ripley as a beacon of honesty, an accidentally talented murderer. He was charming, but not electrically so, unlike Law. Politely handsome, unlike the beatific Alain Delon. Smart, but not obnoxious. His Ripley is a charmless striver looking for love, not money.

Minghella’s adaptation is beautiful, turning the story into an overtly queer text, leaning into Ripley’s identity as a closeted gay man in the 1950s who falls for the petty, vagabond Dickie. It works hard to carve out the humanity of Tom Ripley. The film even opens on a note of regret, with Ripley narrating: “If I could just go back, if I could rub everything out—starting with myself, starting with borrowing a jacket …” It’s a different register, and one that tints the entire film with a note of sick, inescapable sadness. In a different way, Ripley and Dickie were intertwined in Highsmith’s first sketches of the character. In her diary, in 1954, she sketched out a character that would, eventually, be split in two:

A young American, half homosexual, an indifferent painter, with some money from home through an income, but not too much. He is the ideal, harmless looking, unimportant looking, numerous enough, kind of individual a smuggling gang would make use of to handle their contacts, hot goods.

Minghella leans into this merging of identities visually, using mirrors and twisted reflections, all tinted with an overt, and one-sided, desire on Ripley’s part. In Minghella’s version, it’s Dickie who ruins Ripley, setting him on a path of lies and other murders to cover up that initial murder, which ends with him killing the one person, Peter Smith-Kingsley (Jack Davenport), who seemed to see good things in him. Ripley is desperately lonely, encased in shadows.

Zaillian’s Ripley, meanwhile, is all shadows. Gothic, even. This is where Tom Ripley feels most at home, alone but never lonely. Even in the dark, he is not corroded by the darkness that threatens Damon’s Ripley. This Ripley is on a journey towards comfort and beauty. Once he arrives in Italy, he is smitten not with Dickie himself but with the possibility of beauty and the tranquility that the Greenleafs’ money can afford him. If anything, Dickie Greenleaf is the least interesting character in Ripley. Johnny Flynn’s take is not rude, or irascible like Jude Law’s. He might even be considered kind, at times, although deeply, pathetically uninteresting. A laughably mediocre painter, Dickie doesn’t seem to care about much at all: not about his parents, his money, or Marge. When Ripley first meets Dickie and Marge, they are asleep, napping on an Italian beach. He casts a shadow over them. But Ripley is not particularly motivated by murder. It is, like most things, tedious, hard work. The disposal of Dickie (and, later on, of Freddie Miles) takes up more screen time than the murder itself. It is almost comically extended, including a little sit-down to rest after disposing of the corpse. After he bludgeons and disposes of Freddie (Eliot Sumner), Ripley has to go all the way back to the site where he dumped the body to retrieve an incriminating object. Ripley revels in repetition, in its protagonist treading the same steps repeatedly. It is through sheer dumb luck that he isn’t caught, not through his cleverness. And Ripley delights in the lucky tedium of Tom Ripley’s crimes.

The blandness of Dickie and his cohort’s characterization stands in sharp contrast with the undeniable, easy gorgeousness of their lives. Dickie’s villa overlooking the town, his marble floors, his Montblanc pen, and his Picasso, casually hanging in his study. They are so used to it all that they fail to see the value of it, or how intensely Ripley wants what they have, not who they are. Ripley never asks for anything, but in a rare moment of honesty—hidden in plain sight, buried in a rant against refrigerators—he talks about freedom. For Ripley, freedom is not just money but also the invisibility it can buy.

This Ripley covets symbols, things that will act as signifiers of the freedom that wealth can afford. Like the Ripley in the books, who is largely uninterested in sex, desire is not his driving engine. Instead, it’s covetousness. As Scott pointed out, Ripley has an “almost sensual relationship with things.” The moment Ripley walks into Dickie’s house, he comments, “Nice pen,” and promptly pockets it. Dickie doesn’t even notice. That pen casually reappears as Ripley alternates between signing his name or Dickie’s. The camera foregrounds objects, returning to the same ones over and over again, like a murderer returning to the scene of their crime: Dickie’s typewriter and signet ring, the glass ashtray. Every time he settles into a new room, Ripley lovingly sets out his things. He does not imbue them, however, with any sentimentality. He’s not keeping Dickie’s things because they remind him of Dickie, but because they’re nice things and he would like to have them. There is pleasure to be found in objects, as much as there is in art. In the last episode of Ripley, he is gifted Dickie’s ring by Herbert Greenleaf. His work is finished. He has killed Dickie twice over. And he gets to keep the ring. In the end, Tom Ripley is where he wanted to be: alone and surrounded by beautiful things. Dickie is just another object to him, and when he speaks of Dickie, he’s really talking about himself: “Everything about him was an act.”

Art critics speak of negative space as the area surrounding a subject. The brilliance of Ripley lies in how it understands Tom Ripley not as a subject possessed of rich interiority but as the oppressive, empty space that defines those around him. He is the darkness that overtakes Dickie, Marge, and Freddie. Beautiful things smooth out the rough edges of Tom Ripley. As the series progresses, and the Ripley we first meet is well and truly annihilated, something truer emerges: an impeccably dressed black hole.'

#Ripley#Netflix#Matt Damon#Anthony Minghella#Andrew Scott#Patricia Highsmith#Steven Zaillian#Johnny Flynn#Dickie Greenleaf#Alain Delon#Dennis Hopper#John Malkovich#Barry Pepper#The Talented Mr Ripley#Hot Priest#Fleabag#Moriarty#Sherlock#All of Us Strangers#Anton Chekhov#Vanya#Marge Sherwood#Freddie Miles#Dakota Fanning#Gwyneth Paltrow#Jude Law#Peter Smith-Kingsley#Jack Davenport#Eliot Sumner

0 notes

Text

the talented mr. ripley ( 1999 )

#the talented mr. ripley#tom ripley#peter smith kingsley#web weaving#web weave#film stills#*vi film talk#honestly i was too shocked by what happen in this scene#there's so much to talk about

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

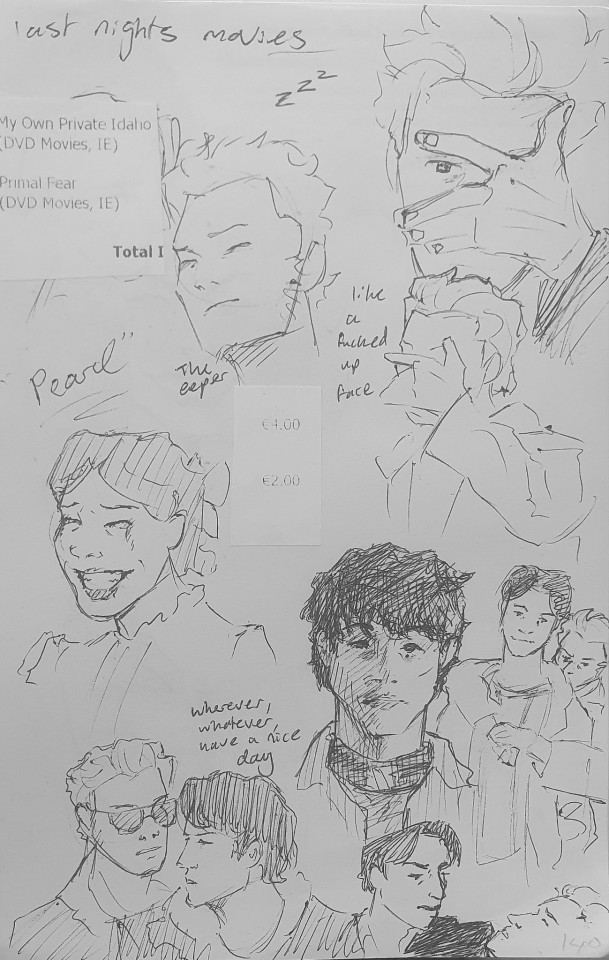

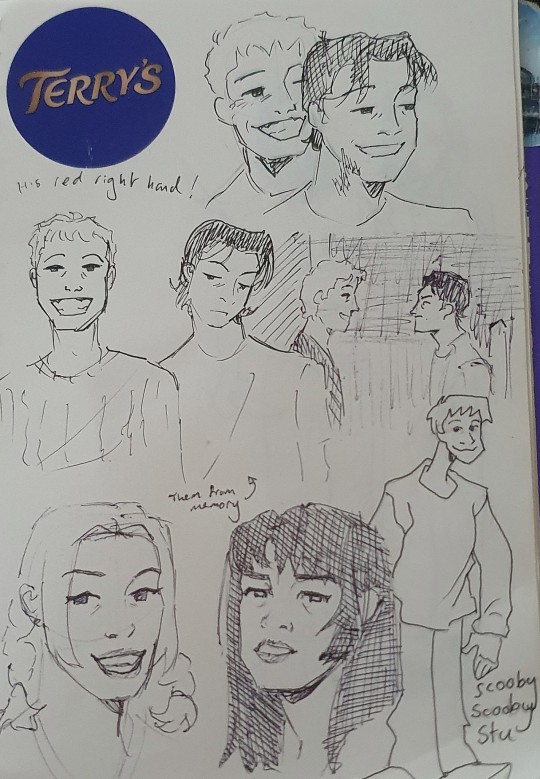

Movie sketchdump

#my own private idaho#pearl 2022#scream#scream 1996#the talented mr ripley#oceans 11#get ready for a boatload of tags#my own private idaho fanart#mike waters#scott favor#scream fanart#sidney prescott#tatum riley#stuilly#stu macher#billy loomis#the talented mr ripley fanart#tom ripley#dickie greenleaf#peter smith kingsley#oceans 11 fanart#rusty ryan#my art

124 notes

·

View notes