#pervuian

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Happy Birthday 🎂 🥳 🎉 🎈 🎁 🎊 To You

The Young & Cute Rising Latina Actress/ Pervuian 🇵🇪 Little J.Lo👧🏽🇵🇪🧡 Of Epic & Loveable Movies 🎥

Ms. Isabela Merced 👧🏽🇵🇪🧡 aka Little J.Lo

#IsabelaMerced #TransformersTheLastKnight #DoraandTheLostCityOfGold #SweetGirl #MadameWeb #TurtlesAllTheWayDown #AlienRomulus

#Isabela Merced#Transformers The Last Knight#dora and the lost city of gold#Sweet Girl Netflix#Madame Web#turtles all the way down#alien romulus#Spotify

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

I would never deny your latina heritage cause whenever people see they think im asian (im pervuian and I go to a pwi these yt people can't tell the difference) so I understand. is mizzou a pwi as well

thank you baby. my brother is peruvian and black and people LOVE denying his heritage . yes mizzou is a pwi, but everyone i've met has been so accepting of everyone. my friends acknowledge that i'm latina and white, and are so considerate, not only with myself but also with my brother as well. (he's going to mizzou).

mizzou, even tho it's in a very conservative state, is one of the most liberal schools in the country. as a latina woman, and my brother being black/peruvian, i've always felt safe here and i have encouraged my brother to come here because of the safety measures, precautions, and all of that that protects students of color here.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Paolo Tessuti Peruviani by Paolo on Flickr

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Peruvian Food - What You Should Eat in Peru

I don’t have a food blender, but let’s go!

#pervuian food#food stuff#my dad and my grandparents chatting over guinea pigs will never not be funny

0 notes

Text

Inkayacu paracasensis

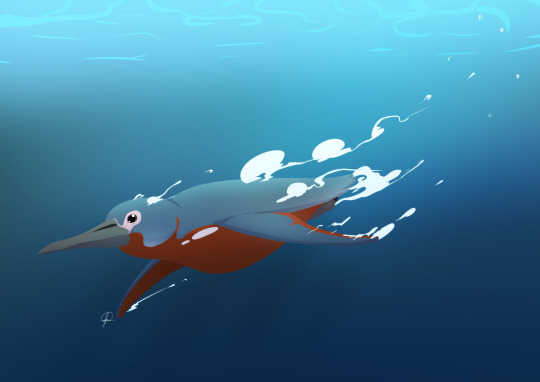

By José Carlos Cortés

Etymology: King of the Water

First Described By: Clarke et al., 2010

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Aequorlitornithes, Ardeae, Aequornithes, Austrodyptornithes, Sphenisciformes, Spheniscidae

Status: Extinct

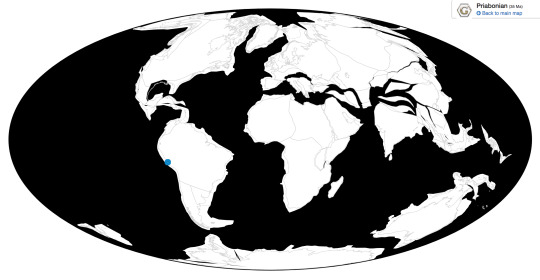

Time and Place: Between 37.2 and 33.9 million years ago, in the Priabonian age of the Eocene of the Paleogene

Inkayacu is known from Yumaque Point of the Otuma Formation in Ica, Peru

Physical Description: Inkayacu was an extinct penguin, and had a lot of similar traits to other extinct penguins - though resembling modern forms, extinct ones were unique in having extremely large bill size and just large body size in general. Inkayacu was about 1.5 meters long, which is a significant jump from the biggest living penguin (the Emperor Penguin at 1.2 meters long), and Inkayacu wasn’t even the biggest penguin at the time. It had a long, pointed bill, much longer than those seen on living members of the group. And - uniquely - we know the color of Inkayacu! Unlike living penguins, which are all varying shades of black and white with some splashes of other colors elsewhere, Inkayacu was grey and brown. We only known these colors form the flippers (wings), which show grey backs of the flipper and brown fronts, but it’s reasonable to suppose this pattern would follow the patterns of living penguins, where the color of the back of the flipper extends throughout the back of the animal, and the color of the front extends to the front. Thus, we depict Inkayacu with a grey back and a brown front, but this is still a conjecture. The melanosomes are similar to modern birds, long and narrow within the feathers - living penguins actually have wider ones. Other than that, the feathers of Inkayacu are similar to modern penguins in other ways, indicating that it had the same aquatic lifestyle. As such, it was flightless.

Diet: Inkayacu, like other penguins, would have fed on a wide variety of fish and aquatic invertebrates.

Icadyptes and Inkayacu by Apokryltaros, CC BY-SA 3.0

Behavior: Though shaped in a lot of ways like living penguins, Inkayacu was different in a number of ways. It had fewer melanosomes in its feathers than living penguins - and these melanosomes provide rigidity in modern penguin feathers that help with deep-sea diving. Without such melanosomes, Inkayacu might not have been as well adapted to deep diving. Still, it was clearly adapted for spending its life in the sea, diving and sea-flying all over its habitat. It would have used its long beak to stab and grab food, especially slippery food that might be hard to get a grip on. Using its flippers, it could propel itself through the water. Its feet were small and not good for moving, so on land it would probably waddle. This is not an uncommon bird to find, fossil-wise, and so it stands to reason that it would have been very social like living penguins. It would have probably laid its eggs on land, and took care of its young with mated partners. Given it lived in Peru, in the Eocene, it was more adapted for warm weather than cold, and wouldn’t have ventured very far south.

By Julio Lacerda, used with permission from Earth Archives

Ecosystem: Inkayacu lived along the Pervuian Priabonian coast, the Western coast of South America right as the global rainforest of the Eocene was collapsing and being replaced with more varying and arid climates. This was also a time of notable climate change and effects on the ocean, leading to a small mass extinction (especially in the oceans) at this time - killing off many iconic forms, including proto-whales. The conditions of this mass extinction actually allowed the penguins to flourish, and Inkayacu was a part of that flourishing. Inkayacu lived alongside proto-whales like Cynthiacetus and Mystacodon - a toothed baleen whale. Inkayacu wasn’t the only penguin in this area, but was joined by the larger and longer-beaked Icadyptes. As for proper fish, there were ray-finned fish like Engraulis and Sardinops, and unnamed sharks. There may have also been the marine snake Pterosphenus. There were many kinds of invertebrates as well. Inkayacu would probably have had to look out for the sharks and whales, though the fish would have had to look out for it! The coast that Inkayacu would have spent its time on would probably have been more rocky than sandy, though it’s uncertain either way.

By Ripley Cook

Other: Inkayacu is very closely related to living penguins and is just outside the group of modern penguins and their closest relatives, so it showcases the evolution of penguins towards what we’re familiar with today. It’s interesting to note that short beaks seem to be characteristic of the modern crown group of penguins, and that long beaks were found in penguins even as close to the crown group as Inkayacu.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Acosta Hospitaleche, C., and M. Stucchi. 2005. Nuevos restos terciarios de Spheniscidae (Aves, sphenisciformes) procedentes de la Costa del Peru. Revista española de paleontología 20(1):1-5

Clarke, J.A.; Ksepka, D.T.; Stucchi, M.; Urbina, M.; Giannini, N.; Bertelli, S.; Narváez, Y.; Boyd, C.A. (2007). "Paleogene equatorial penguins challenge the proposed relationship between biogeography, diversity, and Cenozoic climate change". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (28): 11545–11550.

Clarke, J. A., D. T. Ksepka, R. Salas-Gismondi, A. J. Altamirano, M. D. Shawkey, L. D’Alba, J. Vinther, T. J. DeVries, and P. Baby. 2010. Fossil evidence for evolution of the shape and color of penguin feathers. Science 330

Hoffstetter, R. 1958. Un serpent marin du genre Pterosphenus (Pt. Sheppardi nov. sp.) dans L’Éocène supérieur de L’Équateur (Amérique de Sud). Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France 6:45-50

Hooker, J.J.; Collinson, M.E.; Sille, N.P. (2004). "Eocene-Oligocene mammalian faunal turnover in the Hampshire Basin, UK: calibration to the global time scale and the major cooling event". Journal of the Geological Society. 161 (2): 161–172.

Ivany, Linda C.; Patterson, William P.; Lohmann, Kyger C. (2000). "Cooler winters as a possible cause of mass extinctions at the Eocene/Oligocene boundary". Nature. 407 (6806): 887–890.

Köhler, M; Moyà-Solà, S (December 1999). "A finding of oligocene primates on the European continent". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (25): 14664–7.

Li, Y. X.; Jiao, W. J.; Liu, Z. H.; Jin, J. H.; Wang, D. H.; He, Y. X.; Quan, C. (2016-02-11). "Terrestrial responses of low-latitude Asia to the Eocene–Oligocene climate transition revealed by integrated chronostratigraphy". Clim. Past. 12 (2): 255–272.

Marocco, R., and C. d.e. Muizon. 1988. Los vertebrados del Neogeno de La Costa Sur del Perú: Ambiente sedimentario y condiciones de fosilización. Bulletin de l'Institut Frances d'Etudes Andines 17(2):105-117

Martinez-Cacers, M., and C. de Muizon. 2011. A toothed mysticete from the Middle Eocene to Lower Oligocene of the Pisco Basin, Peru: new data on the origin and feeding evolution of Mysticeti. Sixth Triennial Conference on Secondary Adaptation of Tetrapods to Life in Water 56-57

Molina, Eustoquio; Gonzalvo, Concepción; Ortiz, Silvia; Cruz, Luis E. (2006-02-28). "Foraminiferal turnover across the Eocene–Oligocene transition at Fuente Caldera, southern Spain: No cause–effect relationship between meteorite impacts and extinctions". Marine Micropaleontology. 58 (4): 270–286.

Shackleton, N. J. (1986-10-01). "Boundaries and Events in the Paleogene Paleogene stable isotope events". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 57 (1): 91–102.

Vinther, J., D. E. G. Briggs, R. O. Prum, V. Saranathan. 2008. The colour of fossil feathers. Biology Letters 4 (5): 522 - 525.

Zachos, James C.; Quinn, Terrence M.; Salamy, Karen A. (1996-06-01). "High-resolution (104 years) deep-sea foraminiferal stable isotope records of the Eocene-Oligocene climate transition". Paleoceanography. 11 (3): 251–266.

Zhang, R.; Kravchinsky, V.A.; Yue, L. (2012). "Link between Global Cooling and Mammalian Transformation across the Eocene-Oligocene Boundary in the Continental Interior of Asia]". International Journal of Earth Sciences. 101 (8): 2193–2200.

#Inkayacu paracasensis#Inkayacu#Penguin#Bird#Dinosaur#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Birds#Dinosaurs#Aequorlitornithian#Ardeaen#Water Wednesday#Piscivore#South America#Paleogene#Prehistory#Paleontology#Prehistoric Life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

212 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week #2 Blog

Death in the Andes

By: Mario Vargas Llosa

Pages Read: 1-50

Word Count:310

“you’re one of the last people who saw Demetrio Chanca. You had an argument with him.” Demetrio was one of the mens who disappear the person who was the last to see Demetrio Chanca at that time Litume and Tomasa where really stress because how can you not know where the last person saw go and it was making her suspension too at that time and it just questioning what were they doing.

Summary

In andean village, three men have disappeared. Pervuian Army corporal lituma and his deputy Tomas have been dispatched to investigate and to guard the town from the shining path guerrillas assume are responsible. It's been hard for Lituma and Tomas to find out what's happening to the bodies but the townspeople do not trust officers and have their own ideas about what forces claimed the bodies of the missing men. The first men that disappeared was a woman's husband but Tomas and Lituma were asking who saw her husband; they never saw him. For the second one nothing but Tomas was talking about his past and how he lived. Where i left off Lituma and Tomas are getting chase and there really frighten so Lituma has a revolver ready.

Critical Analysis

Personal response

Where I'm at right now it is really difficult to understand because there alot of flashback and stuff. Right now we still don't know what happen to the guys who disappear because everytime they interview someone its like they just don't know anything or there is like no trace of the missing mens and where i left off their getting chase by some people and Lituma and Tomasita are hiding in the hills of Andes and what i think is going to happen is that there going to try is to escape from them or maybe they'll shoot them because Lituma has revolvr.

0 notes

Text

An Alternative History of Chicha, the Ancient Peruvian Corn Beer (Not) Made With Human Saliva

Chicha de jora, or “chicha” for short, is a naturally fermented, corn-based brew originating in southern Peru. Ancient in origin, it is sold on street corners and in municipal markets today in the Andean regions of Peru and Bolivia, where vendors ply it in repurposed plastic soda bottles to go, or ladle it into pint glasses for passersby to guzzle on the sidewalk.

Chicha has long been understood to be made with masticated maiz — in other words, corn that is chewed and spit out. Because the starch in corn can’t immediately be fermented by yeast, enzymes in saliva convert starch to sugar, making it digestible for yeast, which convert the sugar to alcohol.

Craft beer aficionados may recall Dogfish Head Craft Brewery’s Chicha rendition, offering a modern take that enlists employees to chew and spit indiginous Peruvian corn. Although this is not inaccurate, and the ritual still exists today, a recent study indicates it may not be entirely true — or at least, not the whole truth.

After a years-long excavation of an ancient Peruvian brewery burned and abandoned nearly 1,000 years ago, scientists discovered evidence of a more sophisticated method previously thought to have evolved much later. Sifting through the ashes, the team of archaeologists and anthropologists found that indigenous women brewers were not chewing the corn — they were malting it.

Chicha’s Ancient, Alternate History

Chicha’s ancient origins trace to southern Peru.

In April 2019, scientists from the Field Museum of Chicago, the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, the University of Illinois at Chicago, and Eastern Michigan University published a study in the journal Sustainability detailing a years-long excavation of an expansive brewing facility located on the top of Cerro Baúl, outside the modern city of Moquegua in southern Peru.

The dig took place between 1997 and 2004, and the study centered on “feasting events in the ancient Wari state (600–1000 CE),” specifically “the fabrication of ceramic serving and brewing wares for the alcoholic beverage chicha de molle.”

As part of the study, the team re-constructed a narrative of the ancient brewery, as well as a recipe that may have been used to make the ceremonial brew. They believe the 5,000-square-foot brewery regularly produced between hundreds and thousands of gallons of chicha for religious and political ceremonies that were designed to develop alliances and networks with visiting dignitaries from other Wari communities. Using cutting-edge laser technology, the team examined clay vessels and other brewery remains.

“We found sprouted corn kernels in the brewing room,” Dr. Donna J. Nash, associate professor of archaeology at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro, and a co-author of the study, says. This suggests that the Wari brewers were malting the grains.

Additionally, she says, “We don’t have evidence to prove that chewing was part of the process. When we look at skulls and teeth [of ancient skeletons], we can tell who chewed coca leaves. If there were women tasked with chewing corn, we would see it in their skulls.”

Dr. Nash’s team also found the remains of Peruvian pink peppercorns, suggesting the ingredient was used to flavor the chicha, or to brew another form of the beverage when corn was not available. “Pervuian pepper is what makes the Wari beer special,” Dr. Nash says.

(Peruvian pink peppercorn, known locally as molle, is not technically a peppercorn, but a berry, which grows on local trees year-round. Inside a pink, papery coating is a peppercorn coated with a sugary resin, used to make a honey-type sweetener called “miel de molle.”)

Resurrecting a Recipe (No Saliva Required)

Dogfish Head Craft Brewery launched Chicha in 2009. It released subsequent batches in 2014, 2017, and 2018.

Of course, data can only take science so far. Dr. Nash solicited local women in Moquegua to recreate the ancient recipe her team constructed from the remains, using replicas of the clay boiling and fermenting vessels discovered in the brewery.

It “took a while to find women who knew how to do it,” Dr. Nash says. “The knowledge is quite specific, and women who know how to do it maintain prestige in their families by not sharing that knowledge with everyone.”

Dr. Nash enlisted the leadership of a local expert — whose name she did not share — and who, while supervising the other women, would speak only in Aymara, the local language used by indigenous communities. “She wouldn’t speak in Spanish,” Dr. Nash says.

The chicha de jora resurrection began by sprouting 10 kilograms of corn in damp blankets that were placed against the wall of an agricultural terrace. Twice a day, the women poured water on top of the blankets. After several days, the corn sprouted, and was spread on the blankets to dry for several more days. Once the corn reached a certain appearance, the team ground all 10 kilos of corn into a flour-like consistency using a mesa and mortero (table and grinding stone). It took all day.

Boiling came next, as the corn flour was mixed with water to make a batter, then slowly poured into water brought to a boil in a globe-shaped clay vessel over fire. After boiling the wort for about an hour, the brewers allowed it to cool, then strained the dregs through cheesecloth into fermenting vessels with narrow necks and flared rims.

“Some archaeologists also thought the narrow vessels were for boiling, but when we tried using them for that purpose, they boiled over very quickly,” Dr. Nash says. She adds, “The local women tried to tell us this, but we insisted on experimenting and, sure enough, they were right.”

To make chicha de molle, Dr. Nash and her colleagues collected the tiny pink peppercorns from nearby trees. “The tree sap is quite sticky, and it’s difficult to tell when the berries are ripe,” Dr. Nash says. It requires a certain finesse. She recalls, “The local women had a good laugh at our expense while we picked the molle.”

With the local women’s help, Dr. Nash’s team managed to collect enough ripe molle berries to complete the brew. “They considered this batch something special, as they don’t often make it at home in general, much less in clay pots,” Dr. Nash says. At least one woman threw an early birthday party for a family member so they could enjoy the chicha fresh.

How to Homebrew Your Own Chicha

Feeling adventurous? For those who want to make their own batch of chicha de jora at home, we have developed a Crock Pot or Instant Pot-friendly recipe that takes about a week to make, from sprouting to brewing to fermentation. The corn is available at Mexican or Latin American stores, or possibly in the Mexican/Latin section of supermarkets.

The recipe that follows includes a simple process for making chicha, no spit required.

Ingredients:

2 cups dried maíz morada (purple corn)

1 gallon water

2 cups sugar (piloncillo or panela is best)

4 cinnamon sticks

10 cloves

1 lemon, peel and juice

1 cup pineapple peel (this has the bacteria and wild yeast that will ferment the liquid)

Making the Maiz de Jora

Place the corn in a large bowl and cover it with water. Let it soak for a day.

Rinse the corn, then spread onto a clean towel so the kernels are one layer deep. Roll up the towel.

Place the towel in a large pot and add enough water to soak the towel, but not so much that water is standing in the bottom of the pot. Store at room temperature.

After four days, unroll the towel. Most of the kernels should have sprouted rootlets that are about as long as the corn kernel, which means some of the starch has been converted to sugar. Rinse the kernels.

Spread the kernels on a baking sheet or on tin foil and dry them in the oven on low heat until crunchy, about an hour.

Brewing the Chicha

Put the dried corn in a blender and chop until all the kernels are broken. Alternatively, you can use a rolling pin to crush them or chop them with a knife.

To an Instant Pot, add a gallon of water, the broken corn, sugar, spices, and lemon peel (but not the pineapple peel). Set to warm. You can also do this in a pot on the stove, but use a thermometer to keep the temperature consistently at 150 degrees for an hour. Remove from heat.

When the liquid has cooled to room temperature, strain out the solids and add the lemon juice and pineapple peel. Put the lid back on the pot and let it rest at room temperature.

The liquid should start fermenting in two or three days. After five days, remove the pineapple peel; the chicha should be cloudy and fermenting slightly but ready to refrigerate and drink. The longer this ferments, the stronger the alcohol level and the more sour the final chicha will be.

This story was co-authored by Scott Mansfield.

The article An Alternative History of Chicha, the Ancient Peruvian Corn Beer (Not) Made With Human Saliva appeared first on VinePair.

source https://vinepair.com/articles/chicha-ancient-history-spit-malt/

source https://vinology1.wordpress.com/2019/12/24/an-alternative-history-of-chicha-the-ancient-peruvian-corn-beer-not-made-with-human-saliva/

0 notes

Text

Exploring Ixalan: Annotating the Map of Ixalan

Hello everyone!

Today I was going to release an article detailing all the different equipment and materials the factions of Ixalan use, but last night we got a surprise when Wizards accidentally released the full map of Ixalan on their site. Meant to revealed in 20 pieces, they posted the full Map URL in such a way it was accessible just by changing the numbers in the partial map url. With the Cat out of the Bag and plenty of secrets to go over, let’s start exploring this map.

Possible Spoiler Warning

While this map doesn’t give any real new plot details it WAS accidentally revealed, so it may be considered a spoiler by some folks on principle. If you prefer to see the map given out piece by piece, follow along on the official site.

Otherwise, keep reading to explore the treasures below.

Map of Ixalan, from Wizards of the Coast

Double Faced Card Locations

Ixalan has a theme of DFCs were one side points you to a land that’s on the other side, this map shows the lands seen on cards as actual locations. Since we know Ixalan has ten DFC, it’s possible to determine the names of the cards yet revealed.

Cards we know if seen on the map:

Conqueror's Foothold

Treasure Cove

(Spires of) Orazca

Primal Wellspring

Going by naming conventions the likely next 6 are:

High and Dry

Spitfire Basin

Lost Vale

Azcanta

Temple of Aclazaotz

Deeproot Tree

Spitfire Basin, Temple of Aclazotz and Deeproot Tree stand out because community number crunchers have found that we are likely to get black, green and red aligned dfcs. The Temple, Deeproot Tree and Spitfire Basin seem to have names matching those colors, possibly getting us new mythic lands printed for the first time since Gatecrash.

Faction Capitals

High and Dry

High and Dry is a floating city made up of many Pirate Ships and boats that serves as a base of operations for the Brazen Coalition, a union of pirate crews. It’s in the Stormwreck Sea, which makes sense, as the pirates are descdened from refugees of the East, who crossed that sea to escape conquest by the Legion of Dusk on the eastern continent of Torrezon.

Deeprot Tree

The name “Deeproot” has been seen on many Merfolk cards, leaving the Trees prominent placement to suggest it as their “capital.”

Queen’s Bay

Queen’s Bay is the location colony of the Legion of Dusk on Ixalan, named Miraldanor after their Queen Miralda (very similar to colonial nations on earth such as Virginia and Victoria) it contains the Conqueror’s Foothold, their primary base on the island as well as the island fort of Adanto, named for the first Vampire to set foot on Ixalan.

Pachatupa

References as the capital of the Sun Empire on cards such as Tocatli Honor Guard, Pachatupa’s name is a twist on the legendary Inca name “Tupac,” as detailed by John Dale Beety, Tupac Amaru’s status as the last native ruler of the Inca lead to the name being taken by several other famous people, including the Pervuian native rebel Tupac Amaru II and recording artist Tupac Shakur. While primarily Aztec in design, the Sun Empire does take cues from the Inca, such as their terraced farms in the mountains around the nation.

The Inner Sea

A central aspect of the Merfolk River Heralds, the Inner sea connects to seven rivers that in turn form the Great river of Ixalan. Reddittor Johanson69’s discussion of plate tectonics lead me to notice that the inner sea, and its large central island in the middle, looks very much like an impact crater.

Tycho Lunar Crater as seen from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter

With the Star of Extinction showing a meteor like the one that killed the dinosaurs on Earth hitting Ixalan in the Past and/or future, it’s possible this giant Adventure Time style hole in the island was caused by the last time a Star came down. Which would also explain why the city of Azcanta, very near to the suspected impact point, is now under water.

For flavor bonus, remember the real life meteor that killed the dinosaurs actually landed in Mexico, the inspiration for much of the setting of Ixalan.

Temple of Aclazotz

Johanson69 has pointed out the similarity of Aclazotz with Camazotz, the Maya deity whose name literally means ‘Death Bat”. Associated with night , death and sacrifice,and based on the native-to-Mexico Vampire Bats, a temple with such a similar name being so close to the Vampire faction cant be a coincidence.

Couple with the art and flavor of Deathless Ancients showing the Vampires awakening an old member of their race from an ancient tomb, perhaps the Vampires had interaction on Ixalan longer than many thought.

Quetzatl

Quetzal’s name is an obvious contraction of Quetzalcoatl, the Nauhua name for the mesoamerican feathered serpent seen through many of their culture’s faiths. We have scene this feathered serpent design, on the Sun Empire’s dinosaurs, on their banners (that look a lot like Ugin) and even with actually flying snakes as seen on the card Favorable Winds.

We have yet to see a Coatl card so it's unknown if they are flying snakes, such as on the shard of Naya, or perhaps Drakes. Their possible connection to the Dinosaurs and the Immortal Sun itself may also be key, given Ugin’s Quetzalcoatl-like nature.

Vampiric Script

The middle of the Map is crossed with a banner in the same Vampiric language seen on the sash of Sanguine Sacrament and on the discarded vampire banner in Vanquisher’s Banner. The sharp strokes really drive home that these guys are so Vampiric, even their letters have fangs.

Orazca

Finally the big macguffin itself, the legendary city of Orazca.

The lost Latin American City of Gold is a trope used so much it was overdone 400 years ago. El Dorado, Cibola, The City of the Caesars, La Canela, Paititi, even California was named after a legendary island of gold and Amazons from the novel series Las Sergas de Esplandián by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo. (Yeah people though California was an island for quite some time.)

Many have questioned why it was able to stay hidden on the map but if you study the geography it makes a lot of sense.

It’s surrounded by mountain ranges on all sides but one, and it's one small waterway is bordered by thick jungle. Vraska being the one to be sailing towards it with the Thaumatic Compass makes more sense when you see the Pirate faction as the only one of the four tribes with a direct naval route to the city from their capital.

If you study the effect of Spires of Orazca, you’ll notice they seem to actively repel creatures from the city, another reason it has been able to remain lost so long, and we of course don't know of the dangers within the city itself.

Wrap Up

Ixalan is full of mysteries and lore and I am really stoked Wizards has opened up a setting that we can really explore both in and outside the cards. Personally, i really enjoyed breaking down this map. Annotating a map was my first breakthrough article, so it was a trip down memory lane to do it again with a new property.

Please discuss the lore details and sources of inspiration for Ixalan, and feel free to ask me any questions to keep the conversation rolling.

Enjoy!

-JIm

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peruvian Cuisine in Hollywood, Fl

Peruvian Cuisine in Hollywood, Fl

Pachamanka Aunthetic Peruvian Cuisine in Hollywood Beach, Fl. 9/10

View On WordPress

#authentic cuisine#fl#florida#food#foodie#hollywood#hollywood beach#lunch#Pachamanka Aunthetic Peruvian Cuisine#peru food#peruvian#pervuian food#raw food#raw seafood#rice#seafood

0 notes

Text

An Alternative History of Chicha, the Ancient Peruvian Corn Beer (Not) Made With Human Saliva

Chicha de jora, or “chicha” for short, is a naturally fermented, corn-based brew originating in southern Peru. Ancient in origin, it is sold on street corners and in municipal markets today in the Andean regions of Peru and Bolivia, where vendors ply it in repurposed plastic soda bottles to go, or ladle it into pint glasses for passersby to guzzle on the sidewalk.

Chicha has long been understood to be made with masticated maiz — in other words, corn that is chewed and spit out. Because the starch in corn can’t immediately be fermented by yeast, enzymes in saliva convert starch to sugar, making it digestible for yeast, which convert the sugar to alcohol.

Craft beer aficionados may recall Dogfish Head Craft Brewery’s Chicha rendition, offering a modern take that enlists employees to chew and spit indiginous Peruvian corn. Although this is not inaccurate, and the ritual still exists today, a recent study indicates it may not be entirely true — or at least, not the whole truth.

After a years-long excavation of an ancient Peruvian brewery burned and abandoned nearly 1,000 years ago, scientists discovered evidence of a more sophisticated method previously thought to have evolved much later. Sifting through the ashes, the team of archaeologists and anthropologists found that indigenous women brewers were not chewing the corn — they were malting it.

Chicha’s Ancient, Alternate History

Chicha’s ancient origins trace to southern Peru.

In April 2019, scientists from the Field Museum of Chicago, the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, the University of Illinois at Chicago, and Eastern Michigan University published a study in the journal Sustainability detailing a years-long excavation of an expansive brewing facility located on the top of Cerro Baúl, outside the modern city of Moquegua in southern Peru.

The dig took place between 1997 and 2004, and the study centered on “feasting events in the ancient Wari state (600–1000 CE),” specifically “the fabrication of ceramic serving and brewing wares for the alcoholic beverage chicha de molle.”

As part of the study, the team re-constructed a narrative of the ancient brewery, as well as a recipe that may have been used to make the ceremonial brew. They believe the 5,000-square-foot brewery regularly produced between hundreds and thousands of gallons of chicha for religious and political ceremonies that were designed to develop alliances and networks with visiting dignitaries from other Wari communities. Using cutting-edge laser technology, the team examined clay vessels and other brewery remains.

“We found sprouted corn kernels in the brewing room,” Dr. Donna J. Nash, associate professor of archaeology at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro, and a co-author of the study, says. This suggests that the Wari brewers were malting the grains.

Additionally, she says, “We don’t have evidence to prove that chewing was part of the process. When we look at skulls and teeth [of ancient skeletons], we can tell who chewed coca leaves. If there were women tasked with chewing corn, we would see it in their skulls.”

Dr. Nash’s team also found the remains of Peruvian pink peppercorns, suggesting the ingredient was used to flavor the chicha, or to brew another form of the beverage when corn was not available. “Pervuian pepper is what makes the Wari beer special,” Dr. Nash says.

(Peruvian pink peppercorn, known locally as molle, is not technically a peppercorn, but a berry, which grows on local trees year-round. Inside a pink, papery coating is a peppercorn coated with a sugary resin, used to make a honey-type sweetener called “miel de molle.”)

Resurrecting a Recipe (No Saliva Required)

Dogfish Head Craft Brewery launched Chicha in 2009. It released subsequent batches in 2014, 2017, and 2018.

Of course, data can only take science so far. Dr. Nash solicited local women in Moquegua to recreate the ancient recipe her team constructed from the remains, using replicas of the clay boiling and fermenting vessels discovered in the brewery.

It “took a while to find women who knew how to do it,” Dr. Nash says. “The knowledge is quite specific, and women who know how to do it maintain prestige in their families by not sharing that knowledge with everyone.”

Dr. Nash enlisted the leadership of a local expert — whose name she did not share — and who, while supervising the other women, would speak only in Aymara, the local language used by indigenous communities. “She wouldn’t speak in Spanish,” Dr. Nash says.

The chicha de jora resurrection began by sprouting 10 kilograms of corn in damp blankets that were placed against the wall of an agricultural terrace. Twice a day, the women poured water on top of the blankets. After several days, the corn sprouted, and was spread on the blankets to dry for several more days. Once the corn reached a certain appearance, the team ground all 10 kilos of corn into a flour-like consistency using a mesa and mortero (table and grinding stone). It took all day.

Boiling came next, as the corn flour was mixed with water to make a batter, then slowly poured into water brought to a boil in a globe-shaped clay vessel over fire. After boiling the wort for about an hour, the brewers allowed it to cool, then strained the dregs through cheesecloth into fermenting vessels with narrow necks and flared rims.

“Some archaeologists also thought the narrow vessels were for boiling, but when we tried using them for that purpose, they boiled over very quickly,” Dr. Nash says. She adds, “The local women tried to tell us this, but we insisted on experimenting and, sure enough, they were right.”

To make chicha de molle, Dr. Nash and her colleagues collected the tiny pink peppercorns from nearby trees. “The tree sap is quite sticky, and it’s difficult to tell when the berries are ripe,” Dr. Nash says. It requires a certain finesse. She recalls, “The local women had a good laugh at our expense while we picked the molle.”

With the local women’s help, Dr. Nash’s team managed to collect enough ripe molle berries to complete the brew. “They considered this batch something special, as they don’t often make it at home in general, much less in clay pots,” Dr. Nash says. At least one woman threw an early birthday party for a family member so they could enjoy the chicha fresh.

How to Homebrew Your Own Chicha

Feeling adventurous? For those who want to make their own batch of chicha de jora at home, we have developed a Crock Pot or Instant Pot-friendly recipe that takes about a week to make, from sprouting to brewing to fermentation. The corn is available at Mexican or Latin American stores, or possibly in the Mexican/Latin section of supermarkets.

The recipe that follows includes a simple process for making chicha, no spit required.

Ingredients:

2 cups dried maíz morada (purple corn)

1 gallon water

2 cups sugar (piloncillo or panela is best)

4 cinnamon sticks

10 cloves

1 lemon, peel and juice

1 cup pineapple peel (this has the bacteria and wild yeast that will ferment the liquid)

Making the Maiz de Jora

Place the corn in a large bowl and cover it with water. Let it soak for a day.

Rinse the corn, then spread onto a clean towel so the kernels are one layer deep. Roll up the towel.

Place the towel in a large pot and add enough water to soak the towel, but not so much that water is standing in the bottom of the pot. Store at room temperature.

After four days, unroll the towel. Most of the kernels should have sprouted rootlets that are about as long as the corn kernel, which means some of the starch has been converted to sugar. Rinse the kernels.

Spread the kernels on a baking sheet or on tin foil and dry them in the oven on low heat until crunchy, about an hour.

Brewing the Chicha

Put the dried corn in a blender and chop until all the kernels are broken. Alternatively, you can use a rolling pin to crush them or chop them with a knife.

To an Instant Pot, add a gallon of water, the broken corn, sugar, spices, and lemon peel (but not the pineapple peel). Set to warm. You can also do this in a pot on the stove, but use a thermometer to keep the temperature consistently at 150 degrees for an hour. Remove from heat.

When the liquid has cooled to room temperature, strain out the solids and add the lemon juice and pineapple peel. Put the lid back on the pot and let it rest at room temperature.

The liquid should start fermenting in two or three days. After five days, remove the pineapple peel; the chicha should be cloudy and fermenting slightly but ready to refrigerate and drink. The longer this ferments, the stronger the alcohol level and the more sour the final chicha will be.

This story was co-authored by Scott Mansfield.

The article An Alternative History of Chicha, the Ancient Peruvian Corn Beer (Not) Made With Human Saliva appeared first on VinePair.

source https://vinepair.com/articles/chicha-ancient-history-spit-malt/

0 notes

Text

An Alternative History of Chicha, the Ancient Peruvian Corn Beer (Not) Made With Human Saliva

Chicha de jora, or “chicha” for short, is a naturally fermented, corn-based brew originating in southern Peru. Ancient in origin, it is sold on street corners and in municipal markets today in the Andean regions of Peru and Bolivia, where vendors ply it in repurposed plastic soda bottles to go, or ladle it into pint glasses for passersby to guzzle on the sidewalk.

Chicha has long been understood to be made with masticated maiz — in other words, corn that is chewed and spit out. Because the starch in corn can’t immediately be fermented by yeast, enzymes in saliva convert starch to sugar, making it digestible for yeast, which convert the sugar to alcohol.

Craft beer aficionados may recall Dogfish Head Craft Brewery’s Chicha rendition, offering a modern take that enlists employees to chew and spit indiginous Peruvian corn. Although this is not inaccurate, and the ritual still exists today, a recent study indicates it may not be entirely true — or at least, not the whole truth.

After a years-long excavation of an ancient Peruvian brewery burned and abandoned nearly 1,000 years ago, scientists discovered evidence of a more sophisticated method previously thought to have evolved much later. Sifting through the ashes, the team of archaeologists and anthropologists found that indigenous women brewers were not chewing the corn — they were malting it.

Chicha’s Ancient, Alternate History

Chicha’s ancient origins trace to southern Peru.

In April 2019, scientists from the Field Museum of Chicago, the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, the University of Illinois at Chicago, and Eastern Michigan University published a study in the journal Sustainability detailing a years-long excavation of an expansive brewing facility located on the top of Cerro Baúl, outside the modern city of Moquegua in southern Peru.

The dig took place between 1997 and 2004, and the study centered on “feasting events in the ancient Wari state (600–1000 CE),” specifically “the fabrication of ceramic serving and brewing wares for the alcoholic beverage chicha de molle.”

As part of the study, the team re-constructed a narrative of the ancient brewery, as well as a recipe that may have been used to make the ceremonial brew. They believe the 5,000-square-foot brewery regularly produced between hundreds and thousands of gallons of chicha for religious and political ceremonies that were designed to develop alliances and networks with visiting dignitaries from other Wari communities. Using cutting-edge laser technology, the team examined clay vessels and other brewery remains.

“We found sprouted corn kernels in the brewing room,” Dr. Donna J. Nash, associate professor of archaeology at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro, and a co-author of the study, says. This suggests that the Wari brewers were malting the grains.

Additionally, she says, “We don’t have evidence to prove that chewing was part of the process. When we look at skulls and teeth [of ancient skeletons], we can tell who chewed coca leaves. If there were women tasked with chewing corn, we would see it in their skulls.”

Dr. Nash’s team also found the remains of Peruvian pink peppercorns, suggesting the ingredient was used to flavor the chicha, or to brew another form of the beverage when corn was not available. “Pervuian pepper is what makes the Wari beer special,” Dr. Nash says.

(Peruvian pink peppercorn, known locally as molle, is not technically a peppercorn, but a berry, which grows on local trees year-round. Inside a pink, papery coating is a peppercorn coated with a sugary resin, used to make a honey-type sweetener called “miel de molle.”)

Resurrecting a Recipe (No Saliva Required)

Dogfish Head Craft Brewery launched Chicha in 2009. It released subsequent batches in 2014, 2017, and 2018.

Of course, data can only take science so far. Dr. Nash solicited local women in Moquegua to recreate the ancient recipe her team constructed from the remains, using replicas of the clay boiling and fermenting vessels discovered in the brewery.

It “took a while to find women who knew how to do it,” Dr. Nash says. “The knowledge is quite specific, and women who know how to do it maintain prestige in their families by not sharing that knowledge with everyone.”

Dr. Nash enlisted the leadership of a local expert — whose name she did not share — and who, while supervising the other women, would speak only in Aymara, the local language used by indigenous communities. “She wouldn’t speak in Spanish,” Dr. Nash says.

The chicha de jora resurrection began by sprouting 10 kilograms of corn in damp blankets that were placed against the wall of an agricultural terrace. Twice a day, the women poured water on top of the blankets. After several days, the corn sprouted, and was spread on the blankets to dry for several more days. Once the corn reached a certain appearance, the team ground all 10 kilos of corn into a flour-like consistency using a mesa and mortero (table and grinding stone). It took all day.

Boiling came next, as the corn flour was mixed with water to make a batter, then slowly poured into water brought to a boil in a globe-shaped clay vessel over fire. After boiling the wort for about an hour, the brewers allowed it to cool, then strained the dregs through cheesecloth into fermenting vessels with narrow necks and flared rims.

“Some archaeologists also thought the narrow vessels were for boiling, but when we tried using them for that purpose, they boiled over very quickly,” Dr. Nash says. She adds, “The local women tried to tell us this, but we insisted on experimenting and, sure enough, they were right.”

To make chicha de molle, Dr. Nash and her colleagues collected the tiny pink peppercorns from nearby trees. “The tree sap is quite sticky, and it’s difficult to tell when the berries are ripe,” Dr. Nash says. It requires a certain finesse. She recalls, “The local women had a good laugh at our expense while we picked the molle.”

With the local women’s help, Dr. Nash’s team managed to collect enough ripe molle berries to complete the brew. “They considered this batch something special, as they don’t often make it at home in general, much less in clay pots,” Dr. Nash says. At least one woman threw an early birthday party for a family member so they could enjoy the chicha fresh.

How to Homebrew Your Own Chicha

Feeling adventurous? For those who want to make their own batch of chicha de jora at home, we have developed a Crock Pot or Instant Pot-friendly recipe that takes about a week to make, from sprouting to brewing to fermentation. The corn is available at Mexican or Latin American stores, or possibly in the Mexican/Latin section of supermarkets.

The recipe that follows includes a simple process for making chicha, no spit required.

Ingredients:

2 cups dried maíz morada (purple corn)

1 gallon water

2 cups sugar (piloncillo or panela is best)

4 cinnamon sticks

10 cloves

1 lemon, peel and juice

1 cup pineapple peel (this has the bacteria and wild yeast that will ferment the liquid)

Making the Maiz de Jora

Place the corn in a large bowl and cover it with water. Let it soak for a day.

Rinse the corn, then spread onto a clean towel so the kernels are one layer deep. Roll up the towel.

Place the towel in a large pot and add enough water to soak the towel, but not so much that water is standing in the bottom of the pot. Store at room temperature.

After four days, unroll the towel. Most of the kernels should have sprouted rootlets that are about as long as the corn kernel, which means some of the starch has been converted to sugar. Rinse the kernels.

Spread the kernels on a baking sheet or on tin foil and dry them in the oven on low heat until crunchy, about an hour.

Brewing the Chicha

Put the dried corn in a blender and chop until all the kernels are broken. Alternatively, you can use a rolling pin to crush them or chop them with a knife.

To an Instant Pot, add a gallon of water, the broken corn, sugar, spices, and lemon peel (but not the pineapple peel). Set to warm. You can also do this in a pot on the stove, but use a thermometer to keep the temperature consistently at 150 degrees for an hour. Remove from heat.

When the liquid has cooled to room temperature, strain out the solids and add the lemon juice and pineapple peel. Put the lid back on the pot and let it rest at room temperature.

The liquid should start fermenting in two or three days. After five days, remove the pineapple peel; the chicha should be cloudy and fermenting slightly but ready to refrigerate and drink. The longer this ferments, the stronger the alcohol level and the more sour the final chicha will be.

This story was co-authored by Scott Mansfield.

The article An Alternative History of Chicha, the Ancient Peruvian Corn Beer (Not) Made With Human Saliva appeared first on VinePair.

source https://vinepair.com/articles/chicha-ancient-history-spit-malt/ source https://vinology1.tumblr.com/post/189847776734

0 notes

Text

An Alternative History of Chicha the Ancient Peruvian Corn Beer (Not) Made With Human Saliva

Chicha de jora, or “chicha” for short, is a naturally fermented, corn-based brew originating in southern Peru. Ancient in origin, it is sold on street corners and in municipal markets today in the Andean regions of Peru and Bolivia, where vendors ply it in repurposed plastic soda bottles to go, or ladle it into pint glasses for passersby to guzzle on the sidewalk.

Chicha has long been understood to be made with masticated maiz — in other words, corn that is chewed and spit out. Because the starch in corn can’t immediately be fermented by yeast, enzymes in saliva convert starch to sugar, making it digestible for yeast, which convert the sugar to alcohol.

Craft beer aficionados may recall Dogfish Head Craft Brewery’s Chicha rendition, offering a modern take that enlists employees to chew and spit indiginous Peruvian corn. Although this is not inaccurate, and the ritual still exists today, a recent study indicates it may not be entirely true — or at least, not the whole truth.

After a years-long excavation of an ancient Peruvian brewery burned and abandoned nearly 1,000 years ago, scientists discovered evidence of a more sophisticated method previously thought to have evolved much later. Sifting through the ashes, the team of archaeologists and anthropologists found that indigenous women brewers were not chewing the corn — they were malting it.

Chicha’s Ancient, Alternate History

Chicha’s ancient origins trace to southern Peru.

In April 2019, scientists from the Field Museum of Chicago, the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, the University of Illinois at Chicago, and Eastern Michigan University published a study in the journal Sustainability detailing a years-long excavation of an expansive brewing facility located on the top of Cerro Baúl, outside the modern city of Moquegua in southern Peru.

The dig took place between 1997 and 2004, and the study centered on “feasting events in the ancient Wari state (600–1000 CE),” specifically “the fabrication of ceramic serving and brewing wares for the alcoholic beverage chicha de molle.”

As part of the study, the team re-constructed a narrative of the ancient brewery, as well as a recipe that may have been used to make the ceremonial brew. They believe the 5,000-square-foot brewery regularly produced between hundreds and thousands of gallons of chicha for religious and political ceremonies that were designed to develop alliances and networks with visiting dignitaries from other Wari communities. Using cutting-edge laser technology, the team examined clay vessels and other brewery remains.

“We found sprouted corn kernels in the brewing room,” Dr. Donna J. Nash, associate professor of archaeology at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro, and a co-author of the study, says. This suggests that the Wari brewers were malting the grains.

Additionally, she says, “We don’t have evidence to prove that chewing was part of the process. When we look at skulls and teeth [of ancient skeletons], we can tell who chewed coca leaves. If there were women tasked with chewing corn, we would see it in their skulls.”

Dr. Nash’s team also found the remains of Peruvian pink peppercorns, suggesting the ingredient was used to flavor the chicha, or to brew another form of the beverage when corn was not available. “Pervuian pepper is what makes the Wari beer special,” Dr. Nash says.

(Peruvian pink peppercorn, known locally as molle, is not technically a peppercorn, but a berry, which grows on local trees year-round. Inside a pink, papery coating is a peppercorn coated with a sugary resin, used to make a honey-type sweetener called “miel de molle.”)

Resurrecting a Recipe (No Saliva Required)

Dogfish Head Craft Brewery launched Chicha in 2009. It released subsequent batches in 2014, 2017, and 2018.

Of course, data can only take science so far. Dr. Nash solicited local women in Moquegua to recreate the ancient recipe her team constructed from the remains, using replicas of the clay boiling and fermenting vessels discovered in the brewery.

It “took a while to find women who knew how to do it,” Dr. Nash says. “The knowledge is quite specific, and women who know how to do it maintain prestige in their families by not sharing that knowledge with everyone.”

Dr. Nash enlisted the leadership of a local expert — whose name she did not share — and who, while supervising the other women, would speak only in Aymara, the local language used by indigenous communities. “She wouldn’t speak in Spanish,” Dr. Nash says.

The chicha de jora resurrection began by sprouting 10 kilograms of corn in damp blankets that were placed against the wall of an agricultural terrace. Twice a day, the women poured water on top of the blankets. After several days, the corn sprouted, and was spread on the blankets to dry for several more days. Once the corn reached a certain appearance, the team ground all 10 kilos of corn into a flour-like consistency using a mesa and mortero (table and grinding stone). It took all day.

Boiling came next, as the corn flour was mixed with water to make a batter, then slowly poured into water brought to a boil in a globe-shaped clay vessel over fire. After boiling the wort for about an hour, the brewers allowed it to cool, then strained the dregs through cheesecloth into fermenting vessels with narrow necks and flared rims.

“Some archaeologists also thought the narrow vessels were for boiling, but when we tried using them for that purpose, they boiled over very quickly,” Dr. Nash says. She adds, “The local women tried to tell us this, but we insisted on experimenting and, sure enough, they were right.”

To make chicha de molle, Dr. Nash and her colleagues collected the tiny pink peppercorns from nearby trees. “The tree sap is quite sticky, and it’s difficult to tell when the berries are ripe,” Dr. Nash says. It requires a certain finesse. She recalls, “The local women had a good laugh at our expense while we picked the molle.”

With the local women’s help, Dr. Nash’s team managed to collect enough ripe molle berries to complete the brew. “They considered this batch something special, as they don’t often make it at home in general, much less in clay pots,” Dr. Nash says. At least one woman threw an early birthday party for a family member so they could enjoy the chicha fresh.

How to Homebrew Your Own Chicha

Feeling adventurous? For those who want to make their own batch of chicha de jora at home, we have developed a Crock Pot or Instant Pot-friendly recipe that takes about a week to make, from sprouting to brewing to fermentation. The corn is available at Mexican or Latin American stores, or possibly in the Mexican/Latin section of supermarkets.

The recipe that follows includes a simple process for making chicha, no spit required.

Ingredients:

2 cups dried maíz morada (purple corn)

1 gallon water

2 cups sugar (piloncillo or panela is best)

4 cinnamon sticks

10 cloves

1 lemon, peel and juice

1 cup pineapple peel (this has the bacteria and wild yeast that will ferment the liquid)

Making the Maiz de Jora

Place the corn in a large bowl and cover it with water. Let it soak for a day.

Rinse the corn, then spread onto a clean towel so the kernels are one layer deep. Roll up the towel.

Place the towel in a large pot and add enough water to soak the towel, but not so much that water is standing in the bottom of the pot. Store at room temperature.

After four days, unroll the towel. Most of the kernels should have sprouted rootlets that are about as long as the corn kernel, which means some of the starch has been converted to sugar. Rinse the kernels.

Spread the kernels on a baking sheet or on tin foil and dry them in the oven on low heat until crunchy, about an hour.

Brewing the Chicha

Put the dried corn in a blender and chop until all the kernels are broken. Alternatively, you can use a rolling pin to crush them or chop them with a knife.

To an Instant Pot, add a gallon of water, the broken corn, sugar, spices, and lemon peel (but not the pineapple peel). Set to warm. You can also do this in a pot on the stove, but use a thermometer to keep the temperature consistently at 150 degrees for an hour. Remove from heat.

When the liquid has cooled to room temperature, strain out the solids and add the lemon juice and pineapple peel. Put the lid back on the pot and let it rest at room temperature.

The liquid should start fermenting in two or three days. After five days, remove the pineapple peel; the chicha should be cloudy and fermenting slightly but ready to refrigerate and drink. The longer this ferments, the stronger the alcohol level and the more sour the final chicha will be.

This story was co-authored by Scott Mansfield.

The article An Alternative History of Chicha, the Ancient Peruvian Corn Beer (Not) Made With Human Saliva appeared first on VinePair.

Via https://vinepair.com/articles/chicha-ancient-history-spit-malt/

source https://vinology1.weebly.com/blog/an-alternative-history-of-chicha-the-ancient-peruvian-corn-beer-not-made-with-human-saliva

0 notes

Photo

Get Bundles Now at sparklingstar.mayvenn.com Refer Friends Who Need Bundles!! 🌟🌟Memorial Day Special Sale🌟🌟 ❤Mayvenn 🌟Stars🌟 Sale❤ 💄 Get Your Mayvenn Look 💄 💟 #mayvennmoves 💞 #mayvennhairsale 💜 #sparklingstarmayvenn ❤❤Mayvenn Star Blast Sale❤❤ Save 25% Now - 3 or more bundles with Promo Code: 🌟STARS🌟 #mayvennhair #mayvenndistributor #mayvennmade #mayvennmovement #mayvennstylist #mayvenn #brazilian #pervuian #loosewave #bodywave #straight #deepwave #bundlesdeals #sexy #bundlesdeals #bundlesbystar #frontalunits #stars #blonde #blacchyna #frontals #freeshipping #slay #makeup #hairporn #hairgiveaway #hairgoals #virginhair

#mayvenndistributor#slay#mayvennmade#pervuian#bundlesdeals#hairgoals#frontals#blacchyna#frontalunits#mayvennmovement#blonde#hairporn#stars#brazilian#bundlesbystar#mayvennhairsale#bodywave#mayvenn#deepwave#mayvennmoves#freeshipping#virginhair#makeup#loosewave#mayvennhair#sparklingstarmayvenn#sexy#straight#hairgiveaway#mayvennstylist

0 notes

Photo

Muscle man Carlitos.

3 notes

·

View notes