#perfectly spherical cow

Text

i need yall to look at this gif in the wikipedia article for Spherical Cow

551 notes

·

View notes

Text

day 101 - 4/10/24 - perfectly spherical cow in a vacuum

it's actually not a hypothetical. these are an actual animal that people farm.

there's actually a niche community of cow... uh... what's the word? people who do cow shows, that breed their cows to be as spherical as possible. they have cow shows in vacuums to see who can get the most spherical cow possible.

#monster every day#daily drawing#2024#april 2024#april#perfectly spherical cow in a vacuum#4/10#type: ball

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

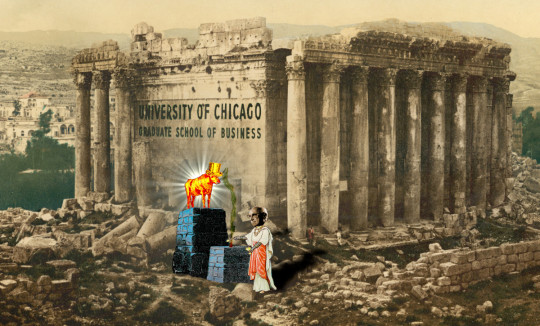

What comes after neoliberalism?

In his American Prospect editorial, “What Comes After Neoliberalism?”, Robert Kuttner declares “we’ve just about won the battle of ideas. Reality has been a helpful ally…Neoliberalism has been a splendid success for the top 1 percent, and an abject failure for everyone else”:

https://prospect.org/economy/2023-03-28-what-comes-after-neoliberalism/

If you’d like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here’s a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/03/28/imagine-a-horse/#perfectly-spherical-cows-of-uniform-density-on-a-frictionless-plane

Kuttner’s op-ed is a report on the Hewlett Foundation’s recent “New Common Sense” event, where Kuttner was relieved to learn that the idea that “the economy would thrive if government just got out of the way has been demolished by the events of the past three decades.”

We can call this neoliberalism, but another word for it is economism: the belief that politics are a messy, irrational business that should be sidelined in favor of a technocratic management by a certain kind of economist — the kind of economist who uses mathematical models to demonstrate the best way to do anything:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/10/27/economism/#what-would-i-do-if-i-were-a-horse

These are the economists whose process Ely Devons famously described thus: “If economists wished to study the horse, they wouldn’t go and look at horses. They’d sit in their studies and say to themselves, ‘What would I do if I were a horse?’”

Those economists — or, if you prefer, economismists — are still around, of course, pronouncing that the “new common sense” is nonsense, and they have the models to prove it. For example, if you’re cheering on the idea of “reshoring” key industries like semiconductors and solar panels, these economismists want you to know that you’ve been sadly misled:

https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/03/24/economy-trade-united-states-china-industry-manufacturing-supply-chains-biden/

Indeed, you’re “doomed to fail”:

https://www.piie.com/blogs/trade-and-investment-policy-watch/high-taxpayer-cost-saving-us-jobs-through-made-america

Why? Because onshoring is “inefficient.” Other countries, you see, have cheaper labor, weaker environmental controls, lower taxes, and the other necessities of “innovation,” and so onshored goods will be more expensive and thus worse.

Parts of this position are indeed inarguable. If you define “efficiency” as “lower prices,” then it doesn’t make sense to produce anything in America, or, indeed, any country where there are taxes, environmental regulations or labor protections. Greater efficiencies are to be had in places where children can be maimed in heavy machinery and the water and land poisoned for a millions years.

In economism, this line of reasoning is a cardinal sin — the sin of caring about distributional outcomes. According to economism, the most important factor isn’t how much of the pie you’re getting, but how big the pie is.

That’s the kind of reasoning that allows economismists to declare the entertainment industry of the past 40 years to be a success. We increased the individual property rights of creators by expanding copyright law so it lasts longer, covers more works, has higher statutory damages and requires less evidence to get a payout:

https://chokepointcapitalism.com/

At the same time, we weakened antitrust law and stripped away limits on abusive contractual clauses, which let (for example) three companies acquire 70% of all the sound recording copyrights in existence, whose duration is effectively infinite (the market for sound recordings older than 90 is immeasurably small).

This allowed the Big Three labels to force Spotify to take them on as co-owners, whereupon they demanded lower royalties for the artists in their catalog, to reduce Spotify’s costs and make it more valuable, which meant more billions when it IPOed:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/09/12/streaming-doesnt-pay/#stunt-publishing

Monopoly also means that all those expanded copyrights we gave to creators are immediately bargained away as a condition of passing through Big Content’s chokepoints — giving artists the right to control sampling is just a slightly delayed way of giving labels the right to control sampling, and charge artists for the samples they use:

https://doctorow.medium.com/united-we-stand-61e16ec707e2

(In the same way that giving creators the right to decide who can train a “Generative AI” with their work will simply transfer that right to the oligopolists who have the means, motive and opportunity to stop paying artists by training models on their output:)

https://pluralistic.net/2023/02/09/ai-monkeys-paw/#bullied-schoolkids

After 40 years of deregulation, union busting, and consolidation, the entertainment industry as a whole is larger and more profitable than ever — and the share of those profits accruing to creative workers is smaller, both in real terms and proportionally, and it’s continuing to fall.

Economismists think that you’re stupid if you care about this, though. If you’re keeping score on “free markets” based on who gets how much money, or how much inequality they produce, you’re committing the sin of caring about “distributional effects.”

Smart economismists care about the size of the pie, not who gets which slice. Unsurprisingly, the greatest advocates for economism are the people to whom this philosophy allocates the biggest slices. It’s easy not to care about distributional effects when your slice of the pie is growing.

Economism is a philosophy grounded in “efficiency” — and in the philosophical sleight-of-hand that pretends that there is an objective metric called “efficiency” that everyone can agree with. If you disagree with economismists about their definition of “efficiency” then you’re doing “politics” and can be safely ignored.

The “efficiency” of economism is defined by very simple metrics, like whether prices are going down. If Walmart can force wage-cuts on its suppliers to bring you cheaper food, that’s “efficient.” It works well.

But it fails very, very badly. The high cost of low prices includes the political dislocation of downwardly mobile farmers and ag workers, which is a classic precursor to fascist uprisings. More prosaically, if your wages fall faster than prices, then you are experiencing a net price increase.

The failure modes of this efficiency are endless, and we keep smashing into them in ghastly and brutal ways, which goes a long way to explaining the “new commons sense” Kuttner mentions (“Reality has been a helpful ally.”) For example, offshoring high-tech manufacturing to distant lands works well, but fails in the face of covid lockdowns:

https://locusmag.com/2020/07/cory-doctorow-full-employment/

Allowing all the world’s shipping to be gathered into the hands of three cartels is “efficient” right up to the point where they self-regulate their way into “efficient” ships that get stuck in the Suez canal:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/03/29/efficient-markets-hypothesis/#too-big-to-sail

It’s easy to improve efficiency if you don’t care about how a system fails. I can improve the fuel-efficiency of every airplane in the sky right now: just have them drop their landing gear. It’ll work brilliantly, but you don’t want to be around when it starts to fail, brother.

The most glaring failure of “efficiency” is the climate emergency, where the relative ease of extracting and burning hydrocarbons was pursued irrespective of the incredible costs this imposes on the world and our species. For years, economism’s position was that we shouldn’t worry about the fact that we were all trapped in a bus barreling full speed for a cliff, because technology would inevitably figure out how to build wings for the bus before we reached the cliff’s edge:

https://locusmag.com/2022/07/cory-doctorow-the-swerve/

Today, many economismists will grudgingly admit that putting wings on the bus isn’t quite a solved problem, but they still firmly reject the idea of directly regulating the bus, because a swerve might cause it to roll and someone (in the first class seats) might break a leg.

Instead, they insist that the problem is that markets “mispriced” carbon. But as Kuttner points out: “It wasn’t just impersonal markets that priced carbon wrong. It was politically powerful executives who further enriched themselves by blocking a green transition decades ago when climate risks and self-reinforcing negative externalities were already well known.”

If you do economics without doing politics, you’re just imagining a perfectly spherical cow on a frictionless plane — it’s a cute way to model things, but it’s got limited real-world applicability. Yes, politics are squishy and hard to model, but that doesn’t mean you can just incinerate them and do math on the dubious quantitative residue:

https://locusmag.com/2021/05/cory-doctorow-qualia/

As Kuttner writes, the problem of ignoring “distributional” questions in the fossil fuel market is how “financial executives who further enriched themselves by creating toxic securities [used] political allies in both parties to block salutary regulation.”

Deep down, economismists know that “neoliberalism is not about impersonal market forces. It’s about power.” That’s why they’re so invested in the idea that — as Margaret Thatcher endlessly repeated — “there is no alternative”:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/11/08/tina-v-tapas/#its-pronounced-tape-ass

Inevitabilism is a cheap rhetorical trick. “There is no alternative” is a demand disguised as a truth. It really means “Stop trying to think of an alternative.”

But the human race is blessed with a boundless imagination, one that can escape the prison of economism and its insistence that we only care about how things work and ignore how they fail. Today, the world is turning towards electrification, a project of unimaginable ambition and scale that, nevertheless, we are actively imagining.

As Robin Sloan put it, “Skeptics of solar feasibility pantomime a kind of technical realism, but I think the really technical people are like, oh, we’re going to rip out and replace the plumbing of human life on this planet? Right, I remember that from last time. Let’s gooo!”

https://www.robinsloan.com/newsletters/room-for-everybody/

Sloan is citing Deb Chachra, “Every place in the world has sun, wind, waves, flowing water, and warmth or coolness below ground, in some combination. Renewable energy sources are a step up, not a step down; instead of scarce, expensive, and polluting, they have the potential to be abundant, cheap, and globally distributed”:

https://tinyletter.com/metafoundry/letters/metafoundry-75-resilience-abundance-decentralization

The new common sense is, at core, a profound liberation of the imagination. It rejects the dogma that says that building public goods is a mystic art lost along with the secrets of the pyramids. We built national parks, Medicare, Medicaid, the public education system, public libraries — bold and ambitious national infrastructure programs.

We did that through democratically accountable, muscular states that weren’t afraid to act. These states understood that the more national capacity the state produced, the more things it could do, by directing that national capacity in times of great urgency. Self-sufficiency isn’t a mere fearful retreat from the world stage — it’s an insurance policy for an uncertain future.

Kuttner closes his editorial by asking what we call whatever we do next. “Post-neoliberalism” is pretty thin gruel. Personally, I like “pluralism” (but I’m biased).

Have you ever wanted to say thank you for these posts? Here's how you can do that: I'm kickstarting the audiobook for my next novel, a post-cyberpunk anti-finance finance thriller about Silicon Valley scams called Red Team Blues. Amazon's Audible refuses to carry my audiobooks because they're DRM free, but crowdfunding makes them possible.

http://redteamblues.com

[Image ID: Air Force One in flight; dropping away from it are a parachute and its landing gear.]

#pluralistic#crypto forks#economism#imagine a horse#perfectly spherical cows of uniform density on a frictionless plane#neoliberialism#inevitabilism#tina#free markets#distributional outcomes#there is no alternative#supply chains#graceful failure modes#law and political economy#apologetics#robert kuttner#the american prospect

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

i joked i was gonna get an econ degree to follow kpop news, but i honestly couldn't stand the amount of vacuous bullshit the feed you in the basic courses

#I'm studying just a module of something vaguely related to economics and the sheer amount of ''this is EFFICIENT and perfectly normal''#but also we had to read an intro to economics concepts and GOD it's like they think you haven't ever read a a fucking newspaper#it's like they're describing both spherical cows and the actual cow and expecting you to decide that it's a perfectly fine model#and calling you an idiot if you don't

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

A perfectly spherical cow.

found the physicist

382 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is an aphorism in science that all models are wrong, but some are useful. The general idea is that a simplified representation of something much more complex may not perfectly replicate every element of the real thing, or account for every single factor that would affect it under real world conditions, but a good simplification potentially can approximate something more complex enough to get broadly accurate* insights that are useful.

In my opinion, specific sexualities and genders (all of them, fwiw), and the even the concept of being cis or trans, are best thought of as useful models for certain amorphous clusters of experiences and feelings, rather than as things that have concrete, inflexible definitions that map perfectly onto every single person who uses that model of identity as a shorthand. Dictionary definitions of what gay means/what a woman is/etc., are all assuming spherical cows in a vacuum to make the maths easier, and you look like an idiot if you think that cows really are spherical and are not affected by atmospheric pressure in any way (or indeed that they could survive vacuum conditions) and then go around harassing cows on this basis.

A person's internal sense of self is more important than your belief in a model. Fuck off and let me get back to chewing cud.

#*or again: accurate enough for a specific purpose#children encountering a concept for the first time learn different models to help them understand it#than the ones undergrads learn to deepen their understanding#and that may be need to be further refined in models scientists with a terminal degree whose research centres around that concept would use#and then different scientific disciplines may find different models for the same thing more useful for their purposes#and individual experiments may require more complex models of the same things than other experiments in the exact same speciality do

196 notes

·

View notes

Note

Here's a fun riddle to test your brain:

You find yourself in an unfamiliar world. In front of you are three children, each of them perfectly rational. Each child is also guarding one of three doors. Behind two of the doors is a monster that will rip all of your limbs off and leave you to die of blood loss, but behind the third door is a magic crystal that will give its holder the powers of a god. You don't know which door the crystal is behind, and you can't understand the language the children speak, but for inexplicable reasons, you know that they can understand your questions. One of them will always tell the truth, one of them always lies, and if you could ask the third one, they would tell you they always lie. Don't think about it. Each child is also blind and only knows what's behind their own door and what their own true or false role is. But what's interesting is that every time any of them answer a question, they will roll a six-sided die. Whichever number the die lands on, they will cycle their truth roles that many spaces. Like so, of course, if it lands on a three or a six, there will effectively be no change, since after that roll, their roles do a full barrel roll. While you and all three children can always see the number rolled, you don't know which way their roles will cycle.

While pondering this problem, you find a brilliantly crafted flute on a pedestal nearby. You take the flute and read the inscription on the pedestal, which gives you important information. Child one wants the flute badly, and if you give it to him, he will do anything he can to help you win this challenge and receive the crystal. Child two has the ability to communicate in a language you understand using the flute, but only if you know Morse code. Child three is skilled in combat and promises she can use the flute as a weapon to protect you from imminent death if you happen to open a door with a monster. The question is: which child should you give the flute to?

The answer (don't read until you've decided your own answer):

Since you don't know Morse code and you're not planning on opening a door with a monster, you give the flute to child one, believing that even if he's the liar, his perfectly rational actions will certainly be in your favor. You then stand in front of door number three as you and child one realize you both have the same idea. Child one opens his door, revealing a monster behind it, and you realize that your odds of guessing the correct door will increase if you now change your decision to door number two. But before you can ask Child two to open it, child one's body is brutally dismembered by the monster behind the door. Child two runs away screaming, and child three takes the flute from child one's corpse and kills the monster. However, when they return, child two moves to guard door number one, child three moves to guard door number two, and child four moves to guard door number three, and so on and so on up to infinity. It should be mentioned that child four is not perfectly rational and did not previously exist; rather, they were a hypothetical future super-intelligence which plans to revive anyone in the past who didn't help in their creation into a simulated punishment. Since you and child one each helped child four come into existence, you two are spared, while children two and three enter a simulated reality.

Child four simulates the two children piloting individual spherical, frictionless cows flying at the same altitude on one axis over a Euclidean planet with a diameter of 50 kilometers. Child two's cow travels at 10 kilometers per day, and child three's cow travels at 20 kilometers per day, starting on Sunday. Child four tells them that at some point during the next five days, they will crash into each other on a day they won't expect. They realize that they won't crash on Friday since making it to Friday will no longer make the crash date unexpected. The same logic eliminates Thursday and Wednesday. Then child four tells them that they will be unconscious for nearly the entire flight. Four will flip a coin, and if it lands on heads, they will both wake up briefly on Monday, and if it lands on tails, they will wake up once on Monday and then on Tuesday with no memory of previously waking up. When they wake up, they have the option to turn exactly 180 degrees without decelerating in hopes of avoiding a crash. They don't know where they start relative to each other, and they're still blind. Additionally, two and three both have the opportunity to throw each other under the bus.

Initially, it is determined that when they crash, they will both wake up injured on a deserted island. If they choose to screw each other over, they will survive the crash unharmed, while the other will stay in a two-week coma before waking up. If they both screw each other over, neither will survive the crash. Both being completely rational, they each elect to screw the other over, but child two was currently the liar, so he accidentally tells child four he won't screw child three over. The simulation of child 1 has now become God and begins an epic battle against child One Prime who has another instance of the God Crystal. Their battle tears apart the multiverse holding time and space over itself several times until child one in perfect rationale directly observes Child 2, causing the superposition to collapse, deleting the entire multiverse that was entangled with him as promised for giving him the flute. Child one then hands the crystal to you, both of you knowing it was all part of the master plan.

If you carefully follow the logic in any other scenario, you will realize that this is the only scenario where you are guaranteed to receive the crystal.

What do you want me to say to this.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Decent men don't need role models like nondecent men do they should be able to be good based on magically objective interpretation of magically objective inputs" okay do you realize it's a very patriarchy type thing to think of men as perfectly spherical frictionless cows

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Something I think people really miss with Gender 101 stuff is that no, you really do need to simplify things when you're first introducing a binary cis person to the idea that gender is more than the binary of penis or vagina. They learn better if you frame things with reference to their existing understanding of the world as much as possible and give them the simplest and easiest-digested version and let them internalize that before complicating things.

Like, that meme about discussing gender with other queer folks (pic of the School of Athens) vs discussing gender with cis folks (pic of teacher and kindergartener)? Everyone's gotta pass through the kindergartener stage before they reach the wise philosophers in deep discussion stage! That's how learning works! It isn't "cis people are dumb" it's "cis people are several years behind you in the school of gender and you can't teach PhD courses to kindergarteners."

So like, "born in the wrong body" narratives aren't reflective of the trans experience for a lot of people (including me, in fact), but they're something cis people struggling to grasp the core concept of transness can get a handle on as an avenue to understanding dysphoria. It gets them through that initial hurdle of comprehending that it's possible for a person's physical body and internal identity to be in conflict. Once they've internalized that, you can explain more fully how different people have really different experiences of transness and dysphoria or lack thereof. The lie-to-children (ie, teach simplified principles first so they have a basis to then understand a more complex reality later) is a key tool of teaching for a reason. Or, in physics trope terms, "born in the wrong body" is useful in the role of a perfectly spherical cow in a vacuum. Does that exist? Not in the real world it doesn't (I hope!) but first-year physics students benefit from considering them nonetheless.

#eadm originals#queerness#thoughts and reflections#i spend a lot of time thinking about the principle of meeting people where they are#and explaining things to them in ways they can digest#both for work and for other areas

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The trolley problem really is the perfectly spherical cows in a perfect frictionless vacuum of moral arguments

1 note

·

View note

Text

How Much of the World Is It Possible to Model? Mathematical Models Power Our Civilization—But They Have Limits.

— By Dan Rockmore | January 15, 2024

Illustration by Petra Péterffy

It’s Hard For a Neurosurgeon to Navigate a Brain. A key challenge is gooeyness. The brain is immersed in cerebrospinal fluid; when a surgeon opens the skull, pressure is released, and parts of the brain surge up toward the exit while gravity starts pulling others down. This can happen with special force if a tumor has rendered the skull overstuffed. A brain can shift by as much as an inch during a typical neurosurgery, and surgeons, who plan their routes with precision, can struggle as the territory moves.

In the nineteen-nineties, David Roberts, a neurosurgeon, and Keith Paulsen, an engineer, decided to tackle this problem by building a mathematical model of a brain in motion. Real brains contain billions of nooks and crannies, but their model wouldn’t need to include them; it could be an abstraction encoded in the language of calculus. They could model the brain as a simple, sponge-like object immersed in a flow of fluid and divided into compartments. Equations could predict how the compartments would move with each surgical action. The model might tell surgeons to make the first cut a half inch to the right of where they’d planned to start, and then to continue inward at an angle of forty-three degrees rather than forty-seven.

Roberts and Paulsen designed their model on blackboards at Dartmouth College. Their design had its first clinical test in 1998. A thirty-five-year-old man with intractable epilepsy required the removal of a small tumor. He was anesthetized, his skull was cut open, and his brain began to move. The model drew on data taken from a preoperative MRI scan, and tracked the movement of certain physical landmarks during the surgery; in this way, the real and predicted topography of the exposed brain could be compared, and the new position of the tumor could be predicted. “The agreement between prediction and reality was amazing,” Roberts recalled recently.

Today, descendents of the Roberts and Paulsen model are routinely used to plan neurosurgeries. Modelling, in general, is now routine. We model everything, from elections to economics, from the climate to the coronavirus. Like model cars, model airplanes, and model trains, mathematical models aren’t the real thing—they’re simplified representations that get the salient parts right. Like fashion models, model citizens, and model children, they’re also idealized versions of reality. But idealization and abstraction can be forms of strength. In an old mathematical-modelling joke, a group of experts is hired to improve milk production on a dairy farm. One of them, a physicist, suggests, “Consider a spherical cow.” Cows aren’t spheres any more than brains are jiggly sponges, but the point of modelling—in some ways, the joy of it—is to see how far you can get by using only general scientific principles, translated into mathematics, to describe messy reality.

To be successful, a model needs to replicate the known while generalizing into the unknown. This means that, as more becomes known, a model has to be improved to stay relevant. Sometimes new developments in math or computing enable progress. In other cases, modellers have to look at reality in a fresh way. For centuries, a predilection for perfect circles, mixed with a bit of religious dogma, produced models that described the motion of the sun, moon, and planets in an Earth-centered universe; these models worked, to some degree, but never perfectly. Eventually, more data, combined with more expansive thinking, ushered in a better model—a heliocentric solar system based on elliptical orbits. This model, in turn, helped kick-start the development of calculus, reveal the law of gravitational attraction, and fill out our map of the solar system. New knowledge pushes models forward, and better models help us learn.

Predictions about the universe are scientifically interesting. But it’s when models make predictions about worldly matters that people really pay attention.We anxiously await the outputs of models run by the Weather Channel, the Fed, and fivethirtyeight.com. Models of the stock market guide how our pension funds are invested; models of consumer demand drive production schedules; models of energy use determine when power is generated and where it flows. Insurers model our fates and charge us commensurately. Advertisers (and propagandists) rely on A.I. models that deliver targeted information (or disinformation) based on predictions of our reactions.

But it’s easy to get carried away—to believe too much in the power and elegance of modelling. In the nineteen-fifties, early success with short-term weather modelling led John von Neumann, a pioneering mathematician and military consultant, to imagine a future in which militaries waged precision “climatological warfare.” This idea may have seemed mathematically plausible at the time; later, the discovery of the “butterfly effect”—when a butterfly flaps its wings in Tokyo, the forecast changes in New York—showed it to be unworkable. In 2008, financial analysts thought they’d modelled the housing market; they hadn’t. Models aren’t always good enough. Sometimes the phenomenon you want to model is simply unmodellable. All mathematical models neglect things; the question is whether what’s being neglected matters. What makes the difference? How are models actually built? How much should we trust them, and why?

Mathematical Modelling Began With Nature: the goal was to predict the tides, the weather, the positions of the stars. Using numbers to describe the world was an old practice, dating back to when scratchings on papyrus stood for sheaves of wheat or heads of cattle. It wasn’t such a leap from counting to coördinates, and to the encoding of before and after. Even early modellers could appreciate what the physicist Eugene Wigner called “the unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics.” In 1963, Wigner won the Nobel Prize for developing a mathematical framework that could make predictions about quantum mechanics and particle physics. Equations worked, even in a subatomic world that defied all intuition.

Models of nature are, in some ways, pure. They’re based on what we believe to be immutable physical laws; these laws, in the form of equations, harmonize with both historical data and present-day observation, and so can be used to make predictions. There’s an admirable simplicity to this approach. The earliest climate models, for example, were essentially ledgers of data run through equations based on fundamental physics, including Newton’s laws of motion. Later, in the nineteen-sixties, so-called energy-balance models described how energy was transferred between the sun and the Earth: The sun sends energy here, and about seventy per cent of it is absorbed, with the rest reflected back. Even these simple models could do a good job of predicting average surface temperature.

Averages, however, tell only a small part of the story. The average home price in the United States is around five hundred thousand dollars, but the average in Mississippi is a hundred and seventy-one thousand dollars, and in the Hamptons it’s more than three million dollars. Location matters. In climate modelling, it’s not just the distance from the sun that’s important but what’s on the ground—ice, water (salty or not), vegetation, desert. Energy that’s been absorbed by the Earth warms the surface and then radiates up and out, where it can be intercepted by clouds, or interact with chemicals in different layers of the atmosphere, including the greenhouse gases—carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide. Heat differentials start to build, and winds develop. Moisture is trapped and accumulates, sometimes forming rain, snowflakes, or hail. Meanwhile, the sun keeps shining—an ongoing forcing function that continually pumps energy into the system.

Earth-system models, or E.S.M.s, are the current state of the art in combining all these factors. E.S.M.s aim for high spatial and temporal specificity, predicting not only temperature trends and sea levels but also changes in the sizes of glaciers at the North Pole and of rain forests in Brazil. Particular regions have their own sets of equations, which address factors such as the chemical reactions that affect the composition of the ocean and air. There are thousands of equations in an E.S.M., and they affect one another in complicated couplings over hundreds, even thousands, of years. In theory, because the equations are founded on the laws of physics, the models should be reliable despite the complexity. But it’s hard to keep small errors from creeping in and ramifying—that’s the butterfly effect. Applied mathematicians have spent decades figuring out how to quantify and sometimes ameliorate butterfly effects; recent advances in remote sensing and data collection are now helping to improve the fidelity of the models.

How do we know that a giant model works? Its outputs can be compared to historical data. The 2022 Assessment Report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change shows remarkable agreement between the facts and the models going back two thousand years. The I.P.C.C. uses models to compare two worlds: a “natural drivers” world, in which greenhouse gases and particulate matter come from sources such as volcanoes, and a “human and natural” world, which includes greenhouse gases we’ve created. The division helps with interpretability. One of the many striking figures in the I.P.C.C. report superimposes plots of increases in global mean temperature over time, with and without the human drivers. Until about 1940, the two curves dance around the zero mark, tracking each other, and also the historical record. Then the model with human drivers starts a steady upward climb that continues to hew to the historical record. The purely natural model continues along much like before—an alternate history of a cooler planet. The models may be complicated, but they’re built on solid physics-based foundations. They work.

Of Course, there are many things we want to model that aren’t quite so physical. The infectious-disease models with which we all grew familiar in 2020 and 2021 used physics, but only in an analogical way. They can be traced back to Ronald Ross, an early-twentieth-century physician. Ross developed equations that could model the spread of malaria; in a 1915 paper, he suggested that epidemics might be shaped by the same “principles of careful computation which have yielded such brilliant results in astronomy, physics, and mechanics.” Ross admitted that his initial idea, which he called a “Theory of Happenings,” was fuelled more by intuition than reality, but, in a subsequent series of papers, he and Hilda Hudson, a mathematician, showed how real data from epidemics could harmonize with their equations.

In the nineteen-twenties and thirties, W.O. Kermack and A.G. McKendrick, colleagues at the Royal College of Physicians, in Edinburgh, took the work a step further. They were inspired by chemistry, and analyzed human interactions according to the chemical principle of mass action, which relates the rate of reaction between two reagents to their relative densities in the mix. They exchanged molecules for people, viewing a closed population in a pandemic as a reaction unfolding between three groups: Susceptibles (“S”), Infecteds (“I”), and Recovereds (“R”). In their simple “S.I.R. model”, “S”s become “I”s at a rate proportional to the chance of their interactions; “I”s eventually become “R”s at a rate proportional to their current population; and “R”s, whether dead or immune, never get sick again. The most important question is whether the “I” group is gaining or losing members. If it’s gaining more quickly than it’s losing, that’s bad—it’s what happens when a covid wave is starting.

Differential equations model how quantities change over time. The ones that come out of an S.I.R. model are simple, and relatively easy to solve. (They’re a standard example in a first applied-math course.) They produce curves, representing the growth and diminishment of the various populations, that will look instantly familiar to anyone who lived through covid. There are lots of simplifying assumptions—among them, constant populations and unvarying health responses—but even in its simplest form, an S.I.R. model gets a lot right. Data from real epidemics shows the characteristic “hump” that the basic model produces—the same curve that we all worked to “flatten” when covid-19 first appeared. The small number of assumptions and parameters in an S.I.R. model also has the benefit of suggesting actionable approaches to policymakers. It’s obvious, in the model, why isolation and vaccines will work.

The challenge comes when we want to get specific, so that we can more rationally and quickly allocate resources during a pandemic. So we doubled down on the modelling. As the covid crisis deepened, an outbreak of modelling accompanied the outbreak of the disease; many of the covid-specific models supported by the C.D.C. used an engine that featured a variation of the S.I.R. model. Many subdivided S.I.R.’s three groups into smaller ones. A model from a group at the University of Texas at Austin, for instance, divided the U.S. into two hundred and seventeen metro areas, segmenting their populations by age, risk factors, and a host of other characteristics. The model created local, regional, and national forecasts using cell-phone data to track mobility patterns, which reflected unprecedented changes in human behavior brought about by the pandemic.

S.I.R.s are one possible approach, and they occupy one end of a conceptual spectrum; an alternative called curve fitting is at the other. The core idea behind curve fitting is that, in most pandemics, the shape of the infection curve has a particular profile—one that can be well-approximated by gluing together a few basic kinds of mathematical shapes, each the output of a well-known mathematical function. The modeller is then more driven by practicalities than principles, and this has its own dangers: a pandemic model built using curve fitting looks like a model of disease trajectory, but the functions out of which it’s built may not be meaningful in epidemiological terms.

In the early stages of the pandemic, curve fitting showed promise, but as time went on it proved to be less effective. S.I.R.-based models, consistently updated with mortality and case data, ruled the day. But only for so long. Back in the nineteen-twenties, Kermack and McKendrick warned that their model was mainly applicable in an equilibrium setting—that is, in circumstances that didn’t change. But the covid pandemic rarely stood still. Neither people nor the virus behaved as planned. sars-CoV-2 mutated rapidly in a shifting landscape affected by vaccines. The pandemic was actually several simultaneous pandemics, interacting in complex ways with social responses. In fact, recent research has shown that a dramatic event like a lockdown can thwart the making of precise long-term predictions from S.I.R.-based models, even assuming perfect data collection. In December, 2021, the C.D.C. abruptly shut down its covid-19 case-forecast project, citing “low reliability.” They noted that “more reported cases than expected fell outside the forecast prediction intervals for extended periods of time.”

These kinds of failures, both in theory and practice, speak at least in part to the distance of the models from the phenomena they are trying to model. “Art is the lie that makes us realize the truth,” Picasso once said; the same could be said of mathematical modelling. All models reflect choices about what to include and what to leave out. We often attribute to Einstein the notion that “models should be as simple as possible, but not simpler.” But, elegance can be a trap—one that is especially easy to fall into when it dovetails with convenience. The covid models told a relatively simple and elegant story—a story that was even useful, inasmuch as it inspired us to flatten the curve. But, if what we needed was specific predictions, the models may have been too far from the truth of how covid itself behaved while we were battling it. Perhaps the real story was both bigger and smaller—a story about policies and behaviors interacting at the level of genomes and individuals. However much, we might wish for minimalism, our problems could require something baroque. That doesn’t mean that a pandemic can’t be modelled faithfully and quickly with mathematics. But we may be still looking for the techniques and data sources we need to accomplish it.

Formal Mathematical Election Forecasting is usually said to have begun in 1936, when George Gallup correctly predicted the outcome of the Presidential election. Today, as then, most election forecasting has two parts: estimating the current sentiment in the population, and then using that estimate to predict the outcome. It’s like weather prediction for people—at least in spirit. You want to use today’s conditions to predict how things will be on Election Day.

The first part of the process is usually accomplished through polling. Ideally, you can estimate the proportions of support in a population by asking a sample of people whom they would vote for if the election were to take place at that moment. For the math to work, pollsters need a “random sample.” This would mean that everyone who can vote in the election is equally likely to be contacted, and that everyone who is contacted answers truthfully and will act on their response by voting. These assumptions form the basis of mathematical models based on polling. Clearly, there is room for error. If a pollster explicitly—and statistically—accounts for the possibility of error, they get to say that their poll is “scientific.” But even with the best of intentions, true random sampling is difficult. The “Dewey Defeats Truman” debacle, from 1948, is generally attributed to polls conducted more for convenience than by chance.

Polling experts are still unsure about what caused so many poor predictions ahead of the 2016 and 2020 elections. (The 2020 predictions were the least accurate in forty years.) One idea is that the dissonance between the predicted (large) and actual (small) margin of victory for President Biden over Donald Trump was due to the unwillingness of Trump supporters to engage with pollsters. This suggests that cries of fake polling can be self-fulfilling, insofar as those who distrust pollsters are less likely to participate in polls. If the past is any indication, Republicans may continue to be more resistant to polling than non-Republicans. Meanwhile, pre-election polling has obvious limitations. It’s like using today’s temperature as the best guess for the temperature months from now; this would be a lousy approach to climate modelling, and it’s a lousy approach to election forecasting, too. In both systems, moreover, there is feedback: in elections, it comes from the measurements themselves, and from their reporting, which can shift (polled) opinion.

Despite these ineradicable sources of imprecision, many of today’s best election modellers try to embrace rigor. Pollsters have long attributed to their polls a proprietary “secret sauce,” but conscientious modellers are now adhering to the evolving standard of reproducible research and allowing anyone to look under the hood. A Presidential-forecast model created by Andrew Gelman, the statistician and political scientist, and G. Elliott Morris, a data journalist, that was launched in the summer of 2020 in The Economist, is especially instructive. Gelman and Morris are not only open about their methods but even make available the software and data that they use for their forecasting. Their underlying methodology is also sophisticated. They bring in economic variables and approval ratings, and link that information back to previous predictions in time and space, effectively creating equations for political climate. They also integrate data from different pollsters, accounting for how each has been historically more or less reliable for different groups of voters.

But as scientific as all this sounds, it remains hopelessly messy: it’s a model not of a natural system but of a sentimental one. In his “Foundation” novels, the writer Isaac Asimov imagined “psychohistory,” a discipline that would bring the rigor of cause and effect to social dynamics through equations akin to Newton’s laws of motion. But psychohistory is science fiction: in reality, human decisions are opaque, and can be dramatically influenced by events and memes that no algorithm could ever predict. Sometimes, moreover, thoughts don’t connect to actions. (“I can calculate the motion of heavenly bodies but not the madness of people,” Newton wrote.) As a result, even though election models use mathematics, they are not actually mathematical, in the mechanistic way of a planetary or even molecular model. They are fundamentally “statistical”—a modifier that’s both an adjective and a warning label. They encode historical relationships between numbers, and then use the historical records of their change as guidance for the future, effectively looking for history to repeat itself. Sometimes it works—who hasn’t, from time to time, “also liked” something that a machine has offered up to you based on your past actions? Sometimes, as in 2016 and 2020, it doesn’t.

Recently, statistical modelling has taken on a new kind of importance as the engine of artificial intelligence—specifically in the form of the deep neural networks that power, among other things, large language models, such as OpenAI’s G.P.T.s. These systems sift vast corpora of text to create a statistical model of written expression, realized as the likelihood of given words occurring in particular contexts. Rather than trying to encode a principled theory of how we produce writing, they are a vertiginous form of curve fitting; the largest models find the best ways to connect hundreds of thousands of simple mathematical neurons, using trillions of parameters.They create a vast data structure akin to a tangle of Christmas lights whose on-off patterns attempt to capture a chunk of historical word usage. The neurons derive from mathematical models of biological neurons originally formulated by Warren S. McCulloch and Walter Pitts, in a landmark 1943 paper, titled “A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity.” McCulloch and Pitts argued that brain activity could be reduced to a model of simple, interconnected processing units, receiving and sending zeros and ones among themselves based on relatively simple rules of activation and deactivation.

The McCulloch-Pitts model was intended as a foundational step in a larger project, spearheaded by McCulloch, to uncover a biological foundation of psychiatry. McCulloch and Pitts never imagined that their cartoon neurons could be trained, using data, so that their on-off states linked to certain properties in that data. But others saw this possibility, and early machine-learning researchers experimented with small networks of mathematical neurons, effectively creating mathematical models of the neural architecture of simple brains, not to do psychiatry but to categorize data. The results were a good deal less than astonishing. It wasn’t until vast amounts of good data—like text—became readily available that computer scientists discovered how powerful their models could be when implemented on vast scales. The predictive and generative abilities of these models in many contexts is beyond remarkable. Unfortunately, it comes at the expense of understanding just how they do what they do. A new field, called interpretability (or X-A.I., for “explainable” A.I.), is effectively the neuroscience of artificial neural networks.

This is an instructive origin story for a field of research. The field begins with a focus on a basic and well-defined underlying mechanism—the activity of a single neuron. Then, as the technology scales, it grows in opacity; as the scope of the field’s success widens, so does the ambition of its claims. The contrast with climate modelling is telling. Climate models have expanded in scale and reach, but at each step the models must hew to a ground truth of historical, measurable fact. Even models of covid or elections need to be measured against external data. The success of deep learning is different. Trillions of parameters are fine-tuned on larger and larger corpora that uncover more and more correlations across a range of phenomena. The success of this data-driven approach isn’t without danger. We run the risk of conflating success on well-defined tasks with an understanding of the underlying phenomenon—thought—that motivated the models in the first place.

Part of the problem is that, in many cases, we actually want to use models as replacements for thinking. That’s the raison d’être of modelling—substitution. It’s useful to recall the story of Icarus. If only he had just done his flying well below the sun. The fact that his wings worked near sea level didn’t mean they were a good design for the upper atmosphere. If we don’t understand how a model works, then we aren’t in a good position to know its limitations until something goes wrong. By then it might be too late.

Eugene Wigner, the physicist who noted the “unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics,” restricted his awe and wonder to its ability to describe the inanimate world. Mathematics proceeds according to its own internal logic, and so it’s striking that its conclusions apply to the physical universe; at the same time, how they play out varies more the further that we stray from physics. Math can help us shine a light on dark worlds, but we should look critically, always asking why the math is so effective, recognizing where it isn’t, and pushing on the places in between. In the nineties, David Roberts and Keith Paulsen sought only to model the physical motion of the gooey, shifting brain. We should proceed with extreme caution as we try to model the world of thought that lives there. ♦

#Covid-19 | Pandemics | Mathematics | Statistics#Artificial Intelligence (A.I.)#Mathematical Models#Our Civilization#Dan Rockmore#The New Yorker

0 notes

Text

The cloud city

The Cloud City floated majestically in and above the clouds, a marvel of engineering and survival. The earth beneath her had long since been swallowed by the masses of water since the great catastrophe, and people had now found their last refuge high up in the sky.

The city pulsed with new energy, fueled by scientists' discovery of levitation of matter using hydrogen. This technology was not only a rescue from the masses of water, but also a sustainable source of energy that shaped people's daily lives. Hovering vehicles moved between each district, powered by the same floating technology that had once created the Cloud City.

In the city's great spherical halls, towered with views of the endless sky, farm animals thrived in an environment perfectly suited to their needs. Cows grazed on floating meadows in the halls while chickens clucked in the airy surroundings. The Cloud City was not only a refuge, but also an oasis of food production.

Huge quantities of vegetables and fruit were grown in large fields with fertile soil. The earth seemed to reach towards the sky, as if it wanted to do its part to ensure that humanity could survive. The residents of the cloud city harvested potatoes, tomatoes and apples at dizzying heights, while the clouds passed below them like fluffy pillows.

The inhabitants of the Cloud City had a unique perspective on the world below them. Earth was a blue planet surrounded by white clouds and endless sky. The remnants of the ancient civilization rose from the water like silent witnesses, and the people of the Cloud City had a responsibility that went beyond their own survival.

They were guardians of the sky, guardians of a new world born in the clouds. And while the memory of the cataclysm of 4712 was still present in people's minds, the Cloud City seemed like a silver ray of hope on the horizon, ready to lead humanity into a future that towered high above the floods of the past.

This and more:

https://www.deviantart.com/heinz7777

0 notes

Text

There’s no such thing as “shareholder supremacy”

On SEPTEMBER 24th, I'll be speaking IN PERSON at the BOSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY!

Here's a cheap trick: claim that your opponents' goals are so squishy and qualitative that no one will ever be able to say whether they've been succeeded or failed, and then declare that your goals can be evaluated using crisp, objective criteria.

This is the whole project of "economism," the idea that politics, with its emphasis on "fairness" and other intangibles, should be replaced with a mathematical form of economics, where every policy question can be reduced to an equation…and then "solved":

https://pluralistic.net/2023/03/28/imagine-a-horse/#perfectly-spherical-cows-of-uniform-density-on-a-frictionless-plane

Before the rise of economism, it was common to speak of its subjects as "political economy" or even "moral philosophy" (Adam Smith, the godfather of capitalism, considered himself a "moral philosopher"). "Political economy" implicitly recognizes that every policy has squishy, subjective, qualitative dimensions that don't readily boil down to math.

For example, if you're asking about whether people should have the "freedom" to enter into contracts, it might be useful to ask yourself how desperate your "free" subject might be, and whether the entity on the other side of that contract is very powerful. Otherwise you'll get "free contracts" like "I'll sell you my kidneys if you promise to evacuate my kid from the path of this wildfire."

The problem is that power is hard to represent faithfully in quantitative models. This may seem like a good reason to you to be skeptical of modeling, but for economism, it's a reason to pretend that the qualitative doesn't exist. The method is to incinerate those qualitative factors to produce a dubious quantitative residue and do math on that:

https://locusmag.com/2021/05/cory-doctorow-qualia/

Hence the famous Ely Devons quote: "If economists wished to study the horse, they wouldn’t go and look at horses. They’d sit in their studies and say to themselves, ‘What would I do if I were a horse?’"

https://pluralistic.net/2022/10/27/economism/#what-would-i-do-if-i-were-a-horse

The neoliberal revolution was a triumph for economism. Neoliberal theorists like Milton Friedman replaced "political economy" with "law and economics," the idea that we should turn every one of our complicated, nuanced, contingent qualitative goals into a crispy defined "objective" criteria. Friedman and his merry band of Chicago School economists replaced traditional antitrust (which sought to curtail the corrupting power of large corporations) with a theory called "consumer welfare" that used mathematics to decide which monopolies were "efficient" and therefore good (spoiler: monopolists who paid Friedman's pals to do this mathematical analysis always turned out to be running "efficient" monopolies):

https://pluralistic.net/2022/02/20/we-should-not-endure-a-king/

One of Friedman's signal achievements was the theory of "shareholder supremacy." In 1970, the New York Times published Friedman's editorial "The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits":

https://www.nytimes.com/1970/09/13/archives/a-friedman-doctrine-the-social-responsibility-of-business-is-to.html

In it, Friedman argued that corporate managers had exactly one job: to increase profits for shareholders. All other considerations – improving the community, making workers' lives better, donating to worthy causes or sponsoring a little league team – were out of bounds. Managers who wanted to improve the world should fund their causes out of their paychecks, not the corporate treasury.

Friedman cloaked his hymn to sociopathic greed in the mantle of objectivism. For capitalism to work, corporations have to solve the "principal-agent" problem, the notoriously thorny dilemma created when one person (the principal) asks another person (the agent) to act on their behalf, given the fact that the agent might find a way to line their own pockets at the principal's expense (for example, a restaurant server might get a bigger tip by offering to discount diners' meals).

Any company that is owned by stockholders and managed by a CEO and other top brass has a huge principal-agent problem, and yet, the limited liability, joint-stock company had produced untold riches, and was considered the ideal organization for "capital formation" by Friedman et al. In true economismist form, Friedman treated all the qualitative questions about the duty of a company as noise and edited them out of the equation, leaving behind a single, elegant formulation: "a manager is doing their job if they are trying to make as much money as possible for their shareholders."

Friedman's formulation was a hit. The business community ran wild with it. Investors mistook an editorial in the New York Times for an SEC rulemaking and sued corporate managers on the theory that they had a "fiduciary duty" to "maximize shareholder value" – and what's more, the courts bought it. Slowly and piecemeal at first, but bit by bit, the idea that rapacious greed was a legal obligation turned into an edifice of legal precedent. Business schools taught it, movies were made about it, and even critics absorbed the message, insisting that we needed to "repeal the law" that said that corporations had to elevate profit over all other consideration (not realizing that no such law existed).

It's easy to see why shareholder supremacy was so attractive for investors and their C-suite Renfields: it created a kind of moral crumple-zone. Whenever people got angry at you for being a greedy asshole, you could shrug and say, "My hands are tied: the law requires me to run the business this way – if you don't believe me, just ask my critics, who insist that we must get rid of this law!"

In a long feature for The American Prospect, Adam M Lowenstein tells the story of how shareholder supremacy eventually came into such wide disrepute that the business lobby felt that it had to do something about it:

https://prospect.org/power/2024-09-17-ponzi-scheme-of-promises/

It starts in 2018, when Jamie Dimon and Warren Buffett decried the short-term, quarterly thinking in corporate management as bad for business's long-term health. When Washington Post columnist Steve Pearlstein wrote a column agreeing with them and arguing that even moreso, businesses should think about equities other than shareholder returns, Jamie Dimon lost his shit and called Pearlstein to call it "the stupidest fucking column I’ve ever read":

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2018/06/07/will-ending-quarterly-earnings-guidance-free-ceos-to-think-long-term/

But the dam had broken. In the months and years that followed, the Business Roundtable would adopt a series of statements that repudiated shareholder supremacy, though of course they didn't admit it. Rather, they insisted that they were clarifying that they'd always thought that sometimes not being a greedy asshole could be good for business, too. Though these statements were nonbinding, and though the CEOs who signed them did so in their personal capacity and not on behalf of their companies, capitalism's most rabid stans treated this as an existential crisis.

Lowenstein identifies this as the forerunner to today's panic over "woke corporations" and "DEI," and – just as with "woke capitalism" – the whole thing amounted to a a PR exercise. Lowenstein links to several studies that found that the CEOs who signed onto statements endorsing "stakeholder capitalism" were "more likely to lay off employees during COVID-19, were less inclined to contribute to pandemic relief efforts, had 'higher rates of environmental and labor-related compliance violations,”' emitted more carbon into the atmosphere, and spent more money on dividends and buybacks."

One researcher concluded that "signing this statement had zero positive effect":

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/08/companies-stand-solidarity-are-licensing-themselves-discriminate/614947

So shareholder supremacy isn't a legal obligation, and statements repudiating shareholder supremacy don't make companies act any better.

But there's an even more fundamental flaw in the argument for the shareholder supremacy rule: it's impossible to know if the rule has been broken.

The shareholder supremacy rule is an unfalsifiable proposition. A CEO can cut wages and lay off workers and claim that it's good for profits because the retained earnings can be paid as a dividend. A CEO can raise wages and hire more people and claim it's good for profits because it will stop important employees from defecting and attract the talent needed to win market share and spin up new products.

A CEO can spend less on marketing and claim it's a cost-savings. A CEO can spend more on marketing and claim it's an investment. A CEO can eliminate products and call it a savings. A CEO can add products and claim they're expansions into new segments. A CEO can settle a lawsuit and claim they're saving money on court fees. A CEO can fight a lawsuit through to the final appeal and claim that they're doing it to scare vexatious litigants away by demonstrating their mettle.

CEOs can use cheaper, inferior materials and claim it's a savings. They can use premium materials and claim it's a competitive advantage that will produce new profits. Everything a company does can be colorably claimed as an attempt to save or make money, from sponsoring the local little league softball team to treating effluent to handing ownership of corporate landholdings to perpetual trusts that designate them as wildlife sanctuaries.

Bribes, campaign contributions, onshoring, offshoring, criminal conspiracies and conference sponsorships – there's a business case for all of these being in line with shareholder supremacy.

Take Boeing: when the company smashed its unions and relocated key production to scab plants in red states, when it forced out whistleblowers and senior engineers who cared about quality, when it outsourced design and production to shops around the world, it realized a savings. Today, between strikes, fines, lawsuits, and a mountain of self-inflicted reputational harm, the company is on the brink of ruin. Was Boeing good to its shareholders? Well, sure – the shareholders who cashed out before all the shit hit the fan made out well. Shareholders with a buy-and-hold posture (like the index funds that can't sell their Boeing holdings so long as the company is in the S&P500) got screwed.

Right wing economists criticize the left for caring too much about "how big a slice of the pie they're getting" rather than focusing on "growing the pie." But that's exactly what Boeing management did – while claiming to be slaves to Friedman's shareholder supremacy. They focused on getting a bigger slice of the pie, screwing their workers, suppliers and customers in the process, and, in so doing, they made the pie so much smaller that it's in danger of disappearing altogether.

Here's the principal-agent problem in action: Boeing management earned bonuses by engaging in corporate autophagia, devouring the company from within. Now, long-term shareholders are paying the price. Far from solving the principal-agent problem with a clean, bright-line rule about how managers should behave, shareholder supremacy is a charter for doing whatever the fuck a CEO feels like doing. It's the squishiest rule imaginable: if someone calls you cruel, you can blame the rule and say you had no choice. If someone calls you feckless, you can blame the rule and say you had no choice. It's an excuse for every season.

The idea that you can reduce complex political questions – like whether workers should get a raise or whether shareholders should get a dividend – to a mathematical rule is a cheap sleight of hand. The trick is an obvious one: the stuff I want to do is empirically justified, while the things you want are based in impossible-to-pin-down appeals to emotion and its handmaiden, ethics. Facts don't care about your feelings, man.

But it's feelings all the way down. Milton Friedman's idol-worshiping cult of shareholder supremacy was never about empiricism and objectivity. It's merely a gimmick to make greed seem scientifically optimal.

The paperback edition of The Lost Cause, my nationally bestselling, hopeful solarpunk novel is out this month!

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/09/18/falsifiability/#figleaves-not-rubrics/a>

#pluralistic#chevron deference#loper bright#scotus#stakeholder capitalism#boeing#economism#economics#milton friedman#shareholder supremacy#fiduciary duty#business#we cant have nice things#shareholder capitalism

343 notes

·

View notes

Text

Στάσις

Dear Caroline:

Today I have managed to watch the other FTX Podcast episode that features you (#36, almost exactly made available 2 years from now), which comes with the bonus of your recorded self, not just your voice. It is all the more valuable as it is so difficult to find any images of you around. I wonder what happened to the glasses, as I suppose that was a serendipitous accident, rather than a visual statement, even if it perfectly conveys that 'bubbly and nerdball', Luna-Lovegood-unconventionally-unhinged-but-in-a-good-way sort of vibe that so well seems to suit you.

I was particularly intrigued by the project of a novel that is referenced, and which I hope will one day see the light of day -I am already counting the days until it appears-, more so now that you will be finding yourself with more time in your hands. Related to this last aspect and also of interest is your very serious and highly absorbing work ethic, even the surrender and abandonment into the service of purpose and meaning, which matches your old, very EA aspiration to secular sainthood and personal sacrifice.

But pack to your post: I have used the Greek term stasis ('standing', 'standing up', mainly used with the extension to 'civil war', 'a house divided') as a heading because it is also a statement of my lack of alignment with the utilitarian, calculating and reductionistic way in which these musings of yours depict the tensions in a relationship. Like, I know I might be a bit naive and idealistic, but truly think a good case can be made against reducing couple dynamics -or for that matter, friendships and families- to just self-interested, zero-sum, power games. We are egoistic creatures, and we do fall into some of this, but to believe that a model that takes it into account contains all -or even, most- of what love and friendship and family are about feels like the proverbial physicist talking about spherical cows in a vacuum.

So yes, there are power plays, and self interest, and social status, and attractiveness, and do ut des, but this all misses the point. In really flourishing friendships and couplings, there is disinterested love for the other, trust, faith, loyalty, going the extra mile, no penny pinching. And effective altruism (with small caps). All these affect the reality of how people interact, from my point of view, and definitely more so than some imaginary ledger that carefully quantifies each and every up and down, plus or minus, debts owed and repaid.

And I guess that you have a more complex take on this that probably shares a lot of what I have said, but I don't think it comes through here. Probably more so in other texts of yours.

I didn't know who Liz Bruenig was -would Catholic, lefty journalist and trad wife be a good summary?-, but can only feel respect and approval for what she says. And I don't quite read it as signalling, but as the words and actions of a person who tries to love another as much as one loves oneself.

Quote:

A blessed thing it is for any man or woman to have a friend, one human soul whom we can trust utterly, who knows the best and worst of us, and who loves us in spite of all our faults.

Charles Kingsley

0 notes

Text

@midoriyaprofessionalslut

I can't even begin to describe the ask I received so I'm just going to leave screenshots😅😅

Also in the new mha season, I thought Tsu was being petty when she called Mineta Grape-Juice and Shoji Tentacle. But nope, those are their hero names.

Side note: I feel like when Mineta gets old and knows how to work his quirk better, he'll be able to control if they stick or not.

Slight racism, usual smut.

NOT PROOF READ SO LET ME KNOW IF U SEE SOMETHING

If you imagine Mineta as in the picture above and with a mature voice, this is more enjoyable. Or you can imagine someone else entirely.. Cause even as someone who's tolerant to Mineta I can't imagine him getting any hoes much less smashing (at least not on top). It would be like watching a chiwawa top a mastiff.

"This is some bullshit." You shuffle through various papers on your desk, each containing the receipts of Pro-Hero Grapejuice's celebratory purchases. Most of it was random appliances that could in no way be used on a day-to-day basis, but there were others….a shiver goes down your spine, there were others that were just downright perverted. "What even is a nub tickler?"

Being an accountant was something you were good at, the numbers came easy and it was interesting to see the income and ways of business that different people in power displayed. Planning meetings and getting the occasional phone call made everything a breeze, but it wasn't what you wanted to do. Or in better words, this was not whom you wanted to work for. Even being number 6 causes the workload to be higher than should be physically possible in the hero world. That's one of the reasons you never gave praise to the rankings because no matter how low in the chain, a hero’s work is always taxing.

Shifting in your seat you look at the analog clock on your desk. 3:45, you were supposed to come to work at 5:30 which means you once again have no time to sleep. Having these late nights had increased 10 fold whenever Mineta went up in rank even by a little. His way of celebrating was spending his money carelessly and leaving you to fix the balance. Though you supposed it may be your fault for never objecting when he barged in your office showing his trinkets as well as leaving his credit card.

"Yeah, it's time to go." You muttered as you read the words, "Dwarf Cow in the left lot of Wisconsin."

The next hour, you take a detour from your office for the first time in months. Heading down the hall you watch the walls go from the pale greys to deep purple and violet splotches splattered along the wall before it inevitably melds into solid purple walls as you get closer to the front door of his office.

Hesitantly you knock on the door and wait until a muffled "Come in." Rings through the thick wood. The room itself was just as flamboyant as the walls leading to it. A beautiful fuchsia carpet on the floor made you realize that calling in your two weeks would have been better than walking into the Willy-Wonka factory that was this office. Various spherical decorations hung from the chandelier, and even something as simple as the legs of his desk was made up of crystal spheres.

The man himself sat perfectly balanced on a large purple ball most likely of his own creation, meanwhile, various children sat around him slipping and sliding on smaller balls in an attempt to copy him. "Ah, here is my beautiful assistant!" The compliment made you cringe as you fiddled with the end of the sleep-wrinkled white blouse you had worn for 2 days straight. "Can we talk sir? It is important." Mineta raised an eyebrow at your formal speech before shrugging.

In an extravagant display of balance, Mineta does a handstand on the ball with one hand before flipping to the other side. "Well kids it's time for me to get done as a hero’s job is never over and blah blah blah the gift shop is giving out free plushies and you can keep your ball." The teacher does her best to usher out her students and the sound of childish screams resound down the hallway even though the door was shut. "How can I help you Y/n?" Mineta offers you his ball to sit on and you reluctantly take the offer as you grate in multiple directions in order to stay afloat.

Mineta watches you with hidden interest as he interlocks his hands underneath his chin. "I didn't know you even knew my name?" Mineta Laughs exposing his annoyingly perfect teeth. It was hard to associate this face to the pictures you see when you search for his early years. "Of course I know your name, I stole your nameplate off your desk 2 months ago." Ah, so that's where it went "What was it you wanted to talk about?"

You sighed, "I would like to put in my two weeks." Mineta goes slack-jawed before composing himself "Why?" Mineta looked at you earnestly, completely confused on why you'd want to abandon your post as his secretary- I mean assistant. "Working for you has become a hassle with your lack of financial maturity." Mineta mock shivers, "Oo big words, me no likey." Mineta hops onto his desk as if he weighed nothing more than paper and squats in front of you, "How about this, you don't quit and instead help me learn how to...how did you say it? Be financially mature." You lean back in your chair unconvinced that he was taking this seriously.

With the final nail ready to be hit, Mineta adds, "How about I give you a raise of 10 percent and a promotion?" You stand up in your chair with an eager grin, "That sounds great!" Mineta smirks to himself but you did not pay any mind to it. "Great, how about we discuss this over food, dinner date?" Your internal celebration screeches to a halt, " Dinner Date-" Mineta looks at you shocked, "Dinner date? Great idea, why didn't I think of it myself!?" A firm hand slides you towards the door as Mineta starts a complimentary speech giving you no room to object, "This is why I need you, you're so smart, I wish I was like you, tomorrow at 11?" You sputter trying to slip past his arms, "11 but I-?!" Mineta loudly gasps again, "There you go doing it again I'm so lucky to have you, tomorrow at 11 my treat!"

The door is shut in your face and the sound of the lock clicking seals your fate. What did you get into?

Cut to 4 years later and you are still not sure of that answer. Simply being bis accountant you had a glimpse of his perverted tendencies, but as his girlfriend, it was further exposed to depths you never could have found yourself imagining. You shuffle papers in the printing room as you do your best to ignore the faint tingling sensation in between your legs. Yet another whim you found yourself following on Mineta’s behalf despite the ever-present fear of being caught. The vibrator comes to life before going back down as quickly as it came. You toss a middle finger to the camera in the top corner of the room knowing he was watching.

"Miss L/n, can I ask you something?" You slap your arm down to your side in embarrassment. I hope he didn't see that. Your coworker walks up to you holding a small stack of papers. "Yes, how can I help you?" The man shows you various forms as he talks, for once you were thankful for Mineta not embarrassing you in front of others. "Oh I see where you went wrong, this right here would be a 20% increase, not 18%." The man applauded you and graciously wrote down your explanation. "Thank you so much, my name is Kaminari by the way."

"Ah hello, Kaminari, and no worries I'm always glad to help!" You turn back as your papers finally scan through but can't help notice Kaminari lingering. "Say Y/n?" You open your mouth to respond only to close it again as the vibratory comes back to life strongly. "Hmmm?!" Kaminari peers at you, your reaction was strange but he couldn't figure out why. "Um, never mind, have a nice day Miss. Y/n, maybe we can get together over coffee or something?” You shrug turning away from Kaminari in fear of your eyes rolling up. The man sways from foot to foot awkwardly before leaving the printing room.

Snapping out of your personal flashback, you look over at your fiance signing autographs for his adoring and objectively feminine fan base. While it was extremely unnerving how unknowingly close they were to your home, you weren't resentful of their gushing.

Your engagement and your overall relationship had not been made public in fear of your personal life being exploited by paparazzi. That doesn't mean, however, the next thing you witness doesn't get your blood boiling.

A girl, no older than maybe 22 waltzes up to Mineta with the confidence of Muhammad Ali in a ring match. Her raven black hair fell flawlessly down her back with not a single split end. Almond eyes decorated with precise coal blink rapidly to draw attention to her seemingly natural eyelashes. With 4 inch wedges. a black halter top, and cuffed jean shorts, it was clear she was someone on a mission. She effortlessly pushes past the nearby fans as they stop to quack at her rivaling beauty. A smirk draws itself with her soft pink lips as she hears people muttering around and about her.

"Wow she's so pretty"

"They would look good together just look at them."

"Ugh, such an attention whore, not giving the rest of us a chance!"

"I bet a 20 she's his type."

"Is she famous?"