#penannular

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The briarwood brooches

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

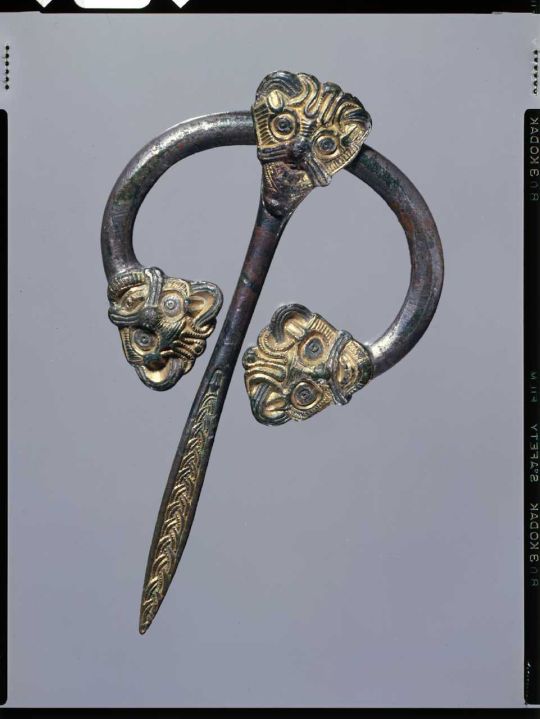

Bossed penannular brooch, found in Ireland, 9th-10th Century

From the British Museum

#penannular brooch#brooch#accessories#fashion#fashion history#irish#celtic#viking age#9th century#800s#10th century#900s#history

186 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Brooch of the Dragon

By Adrián Maldonado

The gift and the curse of being a medievalist is that watching fantasy fiction adaptations can feel a bit like taking your job home with you. You’re still able to be a fan, but you’re also hyper-aware of the real-world inspirations for settings, props and storylines. You’re at an elevated risk of taking to social media and posting about it.

Despite being set in the ancient past of Westeros, I never really get the sense of HBO’s House of the Dragon series as a particularly archaeological story. Sure, there’s occasional ruins like Harrenhal, and some ancient artefacts, but otherwise there’s very little of that sense of the past irrupting into the present that we associate with archaeology.

But then in Season 2, right from the first episode, one aspect of HotD jumped out to me, and it seems like it was just me. There was a real, shocking intrusion of real-world archaeology into this fictional past.

A shocking intrusion (source)

Episode 1 opens up north at the Wall, where two of the realm’s young lords, Cregan Stark and Jacaerys Velaryon, inspect the Night’s Watch. Cregan’s costume and accent ring all sorts of nostalgia bells for fans of the antecedent Game of Thrones series. Jacaerys (or Jace for short) is less awesomely attired, but his woolly black cloak is pinned across his chest with a striking ring-shaped brooch.

And I thought, hey, I know you.

Since last I wrote on these pages, I have become a museum nerd, and have written a book on Viking Age artefacts in Scotland. This involved poring over museum catalogues and excavation reports to become fluent in the visual language of early medieval Europe. There’s lots of ways to be an archaeologist, as covered in nerdy detail on these pages, but dammit, nothing beats the thrill of studying an artefact made, worn and loved a thousand years ago.

And every once in a great while, you get artefacts that reach out from beyond their museum cases and sneak into the zeitgeist. The Lewis Chessmen pop up in Hogwarts; the Sutton Hoo helmet gets everywhere. But I’m declaring the 2020s the age of the pop culture penannular brooch.

Introducing the penannular brooch

Aldclune, Perthshire penannular brooch, National Museums Scotland

Back in the first millennium AD, in the lands which would become Scotland, Ireland and Wales, anyone who was anyone wore a brooch in the shape of an open ring, fitted with a loose pin which speared through the cloth. Twist the hoop, and the pin anchors the fabric in place: a simple but ingenious way of fastening a cloak.

I often see these described as ‘Celtic’ brooches, but in the world of costume jewellery, it seems you can call anything ‘Celtic’ as long as you throw some interlace or knotwork decoration on it. We’re better off calling them by their name: penannular brooches, defined by hoops with a gap, hence pen-, or almost, annular.

In Roman and Iron Age Britain, these were mainly small and utilitarian [Editor's note: after this was posted, I spotted a Roman penannular brooch as worn by General Acacius, as played by Pedro Pascal, in Gladiator II], but by the early medieval period (c AD 400-1100), penannular brooches had grown into big silver jobs with enlarged and ornate terminals. A cloak pinned with one these bad boys was the business suit of its day, with the slight difference that instead of just buying one, you had to earn it, and only a restricted few had access to the best craftspeople. The moulds for casting these metal brooches are found almost exclusively at royal fortresses.

These brooches remained fashionable for centuries, evolving all along the way. One of the most dramatic left-turns in the penannular brooch journey came at the start of the Viking Age. In Scandinavia, the most elaborate brooches had mainly been for women. But when Scandinavians came raiding to the Insular world of Britain and Ireland, they saw both men and women wearing these distinctive ring-shaped brooches, and they wanted them. Bad.

Ball-type silver brooch from the Skaill Hoard, Orkney, National Museums Scotland

The result is that the archaeological record for these centuries is suddenly awash with brooches: looted brooches found in viking graves, as well as hoards of brooches stashed away so vikings wouldn’t get them. By the end of the ninth century, new kinds of penannular brooches began to be made in Scandinavia. This new generation of Insular-Scandinavian brooches grew larger, sometimes to ludicrous sizes, to suit the lavish taste of these new-money overlords.

And then, a thousand years later, after a long day of not finishing papers about brooches that I’m terribly late on, I sit down on the couch to chill with some HotD, and out pops Jacaerys, wearing my homework across his chest.

Casting fantasy jewellery

Superman Targaryen (source)

It was a few years ago I started noticing the return of penannular brooches to a wider consciousness mainly through the fantasy genre. My nerdier friends were chatting about the Netflix adaptation of The Witcher. I didn’t know anything about the books, I just knew the lead guy was the actor then playing Superman in films which I also didn’t care for, but now with a long platinum wig that made him look like the Vampire Lestat on a high-protein diet.

Despite having no knowledge or interest in the series, my eye caught on a weird feature of Lead Guy’s sword. Why did Superman Targaryen have what looked for all the world like the 9th-century Snåsa brooch glued to his sword hilt?

Insular brooch from Snåsa, Nord-Trøndelag, Oslo Kulturhistorisk Museum

Apparently, the script called for Medieval Point Break to carry the brooch of someone he kills in the first episode (I couldn’t be bothered getting into it, but I think there’s answers here). The prop department chose a real archaeological artefact, a ‘Celtic’ brooch from a Viking woman’s grave in Norway, to play the part of a medieval-ish fantasy-looking jewel. Which is odd because the big, yellow brooch makes it look like he’s got a big smiley emoji following him around. But hey, it made me look.

The thing about fantasy adaptations is that they have to feel ‘right’, and that usually entails feeling vaguely medieval. So you tell your costume designer to scout for something a bit different – something that will feel medieval but less familiar, even a bit strange. They go to museums and ‘audition’ all sorts of ancient accessories, and it's often the early medieval period that gets the part. Torturing this metaphor then allows me to make a genius pun about ‘casting’ penannular brooches in prestige fantasy adaptations, for which YOU ARE WELCOME.

The Northman: authenticity Olympics (source)

2022 was basically the penannular brooch singularity. The Viking-age historical fiction film The Northman came out that year, and the press around it was that this was basically the authenticity Olympics, with a tidal wave of interviews on all the research and experts they used to build their period-specific costumes and sets. To my delight, there were tons of penannular brooches to ogle in the film (which is all good until you get to Iceland where they mainly used pins instead of brooches, but I’ll let it go this time).

Our guy Arondir

Then the streaming wars escalated to the level of Rings of Power on Amazon Prime. In season 1, they introduced us to both Baby Elrond and my guy Arondir wearing ‘Celtic’-inspired penannular brooches, recognizable in form but pleasingly Tolkienesque in design.

And so we come to HotD. For season 2, new costume designer Caroline McCall dutifully searched for archaeological inspiration.

“I like costumes to feel like clothes and not costumes that the actors have to wear when they become the characters. So I started looking at ancient civilizations, medieval dress and how the clothes could be constructed so that everything felt real in the time period.” - Caroline McCall

To do so, she visited the British Museum, and came up with objects which combined early medieval “Celtic”, Roman and Viking styles, but still fit in with the kinds of jewellery used in season 1, and the visual world of Westeros as established across 8 seasons of Game of Thrones. Brooches fit the bill, and specifically, penannular ones. One of the first we see in the first episode of season 2 was Jacaerys’s brooch.

If it was just that one thing, it would hardly be enough to write home about, much less come back and revive this blog for. But then I spotted another, and another. The whole rest of the season, I went all Leo DiCaprio pointing meme as they kept popping up (it’s a sickness). Season 2 of HotD was a brooch bonanza. So to share my trauma with you, here’s my guide to the real-world artefacts they seem to be inspired by. Fair warning – I’m so late in actually writing this that I feel no compunction in sharing spoilers for HotD seasons 1 and 2.

The Blackwoods and the Brackens

In HotD season 2, episode three, we are introduced to some new faces who, we quickly gather from context, are members of the feuding houses of Blackwood and Bracken. They wear different colour clothing to help us tell them apart, but, as if to communicate how they are more alike than they are different, the leaders of both parties wear very similar penannular brooches.

This guy, who the google machine tells me is named Davos Blackwood, wears a silver penannular with elaborate circular terminals, and weirdly, what looks like a bronze pin. I don’t know of any brooches which mix metal components in this way, but silver brooches with disc-shaped terminals are fairly common down to the ninth century. They were particularly popular among the Picts, the real-life ‘kings in the north’ in what would become Scotland.

Carronbridge, Dumfriesshire penannular brooch, Dumfries Museum

At first glance, it looked like the brooch terminals were perforated, which seemed peculiar, but on closer inspection, it looks like they have empty settings. Well, lots of these brooches in museums also have empty settings, but it’s not on purpose – it’s because they are quite old and the glass, amber or garnet insets have fallen out!

The Blackwoods’ rivals in this scene are the Brackens, led here by a guy called [checks google] Aeron Bracken, who also wears a penannular brooch. His looks a bit different, though. It appears to be made from a copper-alloy rather than silver, suggesting the Brackens are maybe a rung lower down the social ladder. He wears it slightly differently as well, with the terminals facing in toward his chest rather than straight up. More likely to impale yourself, I might add, which may have historically affected their family’s standing, but I digress.

Brooch from the St Ninian's Isle, Shetland hoard, National Museums Scotland

Now, this brooch looks rather like some of my absolute favourite Pictish brooches, with confronted animals. Most of these were also made of bronze, but often with an outer layer of gold, silver or even tin to mask their true colour. These were never terribly common, but they were, however, a type that vikings took a shine to, and so from Ireland to Sweden, we start to see lots of pretty awesome takes on penannular brooches with beast heads.

But for all that, I think the artefacts that the Bracken brooch remind me of most is these ancient Greek ram’s head armlets. They do have examples in the British Museum, too, where we know the inspo came, so for all my digression, this may have been the ultimate inspiration.

Jace and Baela

The other most prominent ring-brooches in HotD season 2 are the ones worn by the putative future royal couple, the heirs apparent of Team Black (if they survive the next season), Jacaerys Velaryon and Baela Targaryen. These get a lot of screen time from various angles, so we have a better idea of what these look like (and for the keen-eyed, how they play against different lighting and fabric).

We have already seen Jace’s brooch, somewhat lost in the black gloom of his northern cloak in episode 1. As the season goes on, we see his outfit and demeanour change from princeling to general, with his brooch becoming ever more prominent, announcing his station almost like a miniature crown.

Brooch from Høm, Zealand, Copenhagen Nationalmuseet

As Jace’s brooch becomes clearer, we see the hoop is of twisted silver, with what look like dragon-head terminals and a mask at the head of the pin. It’s a mashup of lots of things, but is essentially again a Viking-age take on a penannular brooch. Like the Brackens’ brooch, the hoop ends with confronted heads, but adding a mask at the head of the pin seems to be a Scandinavian Borre-style development. The twisted hoop is drawn from Gotlandic brooches of a similar vintage. All the faceted surfaces allow the light to play across it more dynamically, making it seem to almost move or come alive.

But then turning to Baela we get a rather different take. She wears a matching padded surcoat to Jace’s but her brooch is clearly different. To start off with, it’s not penannular but annular – a full ring. That means it looks great, but can’t work as a fastener in the same way, as it can’t anchor the cloth with its hoop. This is perhaps why Baela’s is worn with an awesome silver retaining chain, fastened to her belt.

Tara Brooch, National Museum of Ireland

There are early medieval parallels to the use of a retaining chain. In eighth-century Ireland, there was a fashion for brooches that looked like penannulars, but with such elaborate ornament across the terminals that they were no longer terribly functional without a bit of help; the Tara Brooch is the best example.

There’s good reasons why Baela’s brooch is different. It expresses continuity with the existing Game of Thrones adaptation's visual language, as her ring brooch with dragons recalls the brooches worn by Danaerys Targaryen and her retinue, Missandei and Grey Worm, towards the end of the series. As arguably the only legitimate heir to the throne between her and cousin Jace, it is fitting to draw a line from Baela to the future queen.

But all this brings us back to Jace’s brooch which, while functional, actually seems to become less and less practical and more symbolic as the season goes on. Once he acquires his forever outfit of a studded surcoat with fetching red capelet, the brooch worn at the shoulder is no longer actually doing anything. It is pinned onto the cape with its pin pointing down the gap in the terminals, worryingly aimed at his heart. As one Reddit user pointed out, his brooch becomes something rather like the Hand of the King pin (for which, see more below). His brooch, now part of his uniform, is acting like a general’s medals.

One final interesting point on the brooches of Team Black. By the end of the season, we have recruited a few new team members. At least one of them gains a dragon-brooch, and it is a doozy. It’s an annular dragon similar to Baela’s, but supercharged. New converts are the biggest zealots, and Ulf may be compensating for quite a lot – I guess we’ll find out next season.

Penannular power: the Hand of the King

Gathering all of the observations above, then, it seems that Westeros is currently in a historical phase akin to Scotland and Ireland in the Viking Age. Penannular brooches seem to have been widely used, but are now becoming the preserve of regional lords. At the same time, in the halls of power, there are exaggerated versions of penannular brooches being made, but they are less and less functional, and more totemic, retaining the traditional symbolism of power, but worn as medals and badges.

Hand of the King pin as used in House of the Dragon (source)

There is one last example that convinces me that the use of penannular brooches in HotD is more than just eye candy. It takes a real sickness to even notice this, but there was a subtle change to the design of the iconic pin that the Hand of the King wears in House of the Dragon. In the Game of Thrones series, the pin was a simple hoop and hand, but the subtle redesign for HotD made me do a spit-take.

Penannular brooch from Ireland, Walters Art Museum

The design is obvious to anyone who has spent too long looking at museum catalogues: the hand is now encircled by the early Irish bronze penannular brooch from the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore.

If we assume that penannular brooches ‘evolved’ in a similar way in Westeros as they did in Britain and Ireland, the kind of brooch used on the Hand pin would be an antique – the Walters Museum brooch is a classic Kilbride-Jones “group C” of the sixth or seventh century, or some 200-300 years older than the Pictish examples highlighted above.

I love the HotD Hand of the King pin as the apotheosis of the penannular brooch in Westeros. While there still are apparently lots of them out there among the petty kingdoms of the Riverlands, among the halls of power we see that big silver brooches were already on their way to becoming symbolic, keeping their ring shape only as a nod to the antiquity of the brooch as a badge of power. From the annular brooches of Team Black to the antique brooch depicted on the Hand of the King pin, Season 2 of HotD is a great example of how early medieval material culture actually worked, and continues to work on us now, however imperceptibly, more than a thousand years later.

AlmostArch is no longer on Twitter. Follow us instead at AlmostArch.bsky.social.

Featured image by siilverlady

#House of the Dragon#HotD#Rings of Power#the witcher#the northman#penannular brooches#archaeology#early medieval#Picts#Scotland#gladiator 2

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brooch C6605

A different colouring i did for a print. I wish i had the patience to draw these again. They are a lot of fun but take so so much time.

Object C6605 in the Danish Nationalmuseet

#viking age#norse#illustration#archaeology#iron age#denmark#brooch#borre style#bronze#penannular brooch#scandinavia#nordic#viking#artists on tumblr#digital art#my art

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Made one of these at a request. Actually been meaning to do a couple small ones for myself.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

First time hammering brass, just playing around and trying to get a feel l. Started with two different thickness rods from the hardware store

And after brushing it looks pretty good

Not bad for a first go - I only messed it up twice

I needed an extra for Steppes Warlord (SCA) which starts this afternoon but I'll be daytripping in tomorrow and the next day because it's texas, and if im going to sleep its gonna be with some climate control

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beaded Penannular Earring - Met Museum Collection

Inventory Number: 26.7.1356 New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, ca. 1550–1425 B.C. Location Information: From Egypt, Upper Egypt, Thebes, Dra Abu el-Naga, Mandara, Carnarvon/Carter excavations, 1914

#Beaded Penannular Earring#new kingdom#new kingdom pr#dynasty 18#upper egypt#thebes#dra abu el-naga#dra abu el naga#mandara#earrings#jewelry#met museum#26.7.1356#NKPRJ

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I made penannular cloak pins today!

First time ever doing it, the copper was first and the brass was second. Simple but fun.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Silver penannular broach uncovered near Waterford, Ireland, 9th-10th century

from The British Museum

807 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bossed penannular brooch, Irish, 9th-10th Century

From the British Museum

#penannular brooch#brooch#irish#accessory#fashion history#fashion#history#silver#viking age#9th century#800s#10th century#900s

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

Breadalbane Brooch, 8th Century CE, Perth Museum, Scotland

A silver gilt annular brooch probably made in Ireland and later refashioned to look like a penannular brooch for a new Pictish owner.

#early medieval#archaeology#metalwork#metalworking#brooch#jewellery#ancient crafts#ancient cultures#ancient living#status#Scotland#relics#design#breadalbane brooch

199 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The individual SH-63 was found within the Sárrétudvari–Hízóföld cemetery, which is the largest 10th-century-CE cemetery in Hungary and contains a large number of burials containing weapons and horse-riding equipment. It was in use during the Hungarian Conquest period, in which many mounted archers conducted and fought battles across Europe.

Despite not having many particularly "wealthy" grave goods, the burial of SH-63 was unique for its grave goods composition, says Dr. Tihanyi. "Male burials often contained functional items, such as simple jewelry (e.g., penannular hair rings and bracelets), clothing fittings (e.g., belt buckles), and tools (e.g., fire-lighting kits and knives). Their most distinctive grave goods included weapons, usually archery equipment, with two graves containing sabers and one grave containing an axe.

"Horse-riding equipment and, in some cases, horse bones (e.g., skull and extremities) were also found. Female burials, in contrast, more frequently contained jewelry (e.g., hair rings, braid ornaments, bead necklaces, bracelets, and finger rings) and clothing fittings (e.g., bell buttons and metal ornaments). Tools, such as knives and awls, appeared less often.

"The grave goods found in the burial of SH-63 contained a mix of these characteristics. Compared to other graves in the cemetery, its inventory was relatively simple, including common jewelry and clothing fittings."

More specifically, SH-63 was found together with a silver penannular hair ring, three bell buttons, a string of stone and glass beads, an "armor-piercing" arrowhead, iron parts of a quiver, and an antler bow plate.

Meanwhile, the three major traumas identified in the upper limb bones were likely the result of a fall onto an outstretched arm or onto the shoulder. These injuries never fully healed and could have been caused in daily life.

However, one factor does speak to the woman perhaps having lived a more active life. Various joint and ethereal (where bones and muscles attach) changes were observed. These changes were most prominently observed in the upper right-hand side of the body, and similar changes have been found in other graves containing weapons and/or horse-riding equipment.

This suggests these individuals, including SH-63, were likely engaged in similar daily activities, which may, in turn, explain the high number of physical traumas seen throughout the Sárrétudvari-Hízóföld cemetery.

While the researchers cannot definitively conclude the female was a warrior, they were able to positively identify this as the first-known instance in which a female was buried together with weaponry in the Carpathian Basin during the 10th century."

#history#women in history#warrior women#women warriors#10th century#archeology#hungary#hungarian history#european history

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

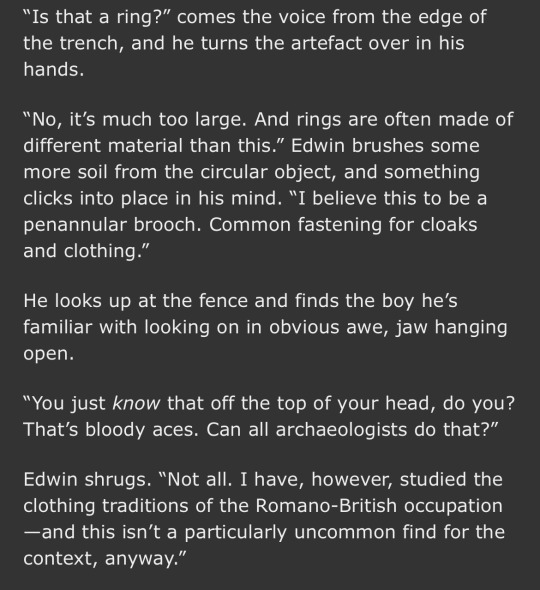

Turns out I accidentally predicted finding this penannular brooch when I wrote love, in context B24-16 last year, all the way down to the missing pin! (Though I was excavating on a rampart, not a road…and I didn’t have anyone peering over a fence at me)

#lucy's thoughts#dead boy detectives#dbda#my writing#hey i’m still here! i’ve been busy though! and stressed!#anyway i thought this was funny. also I completely did not recognize the brooch for what it was at the time#in my defense it’s a particularly corroded example

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

a simple slight fucking rotation, i beg

hotd costumers: we're gonna use some nice penannular brooches this season

hotd costumers: we will not close them correctly though. have fun staring at that

#this one is actually really pissing me off because there is no excuse there are LITERALLY ENDLESS fucking resources on how penannulars work#'its a fantasy show' in a world where cloth has physics like cloth in our world does so my point still stands#with it sitting there useless it is only further highlighting that the cloak is secured under that tunic flap#instead of being secured by the LARGE PIN DESIGNED AND HISTORICALLY USED FOR CLOAK SECURING

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pretty happy with this cowl. Only had two buttons that would fit the style, but then I found this hand forged penannular brooch that I had forgotten I even owned. So that will work nicely I think.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Penannular Earring - Met Museum Collection

Inventory Number: 17.6.114 New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, ca. 1550–1295 B.C. Location Information: From Egypt; Probably from Northern Upper Egypt, Deir el-Ballas

#Penannular Earring#earrings#jewelry#new kingdom#new kingdom pr#dynasty 18#upper egypt#northern upper egypt#deir el-ballas#deir el ballas#met museum#17.6.114#NKPRJ

0 notes