#panama 2017

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ricky Martin - María (Pablo Flores remix) 1995

"María" is a song recorded by Puerto Rican singer Ricky Martin for his third studio album, A Medio Vivir (1995), and was released as the second single from the album on November 21, 1995. Musically, "María" is a Spanish-language flamenco, dance, and salsa song, featuring elements of mariachi, samba, cumbia, Latin, African, Caribbean, and Latin pop. On the remix, Puerto Rican DJ Pablo Flores upped the tempo and the sex appeal of the song, turning the slow-burn flamenco laced track into an up-tempo samba tune in a house bassline. The remix version became more popular than the original one. "María" became Martin's breakthrough song and his first international hit. It topped the charts in 20 countries, and has sold over five million physical copies worldwide. As a result, the song was featured in the 1999 edition of The Guinness Book of Records as the biggest Latin hit. It was also the Song of the Summer in Spain in 1996 and was the second best-selling single in the world that year.

In Australia, "María" spent six weeks at number one. It topped the country's year-end chart in 1998, and was certified platinum. The song topped the Ultratop Wallonia chart of Belgium for 10 consecutive weeks and was certified double platinum. It spent nine weeks at number one in France and was certified diamond. It went number one in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Hungary, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Puerto Rico, and Venezuela. In the US, "María" peaked at number six on Billboard's Hot Latin Tracks chart, giving Martin his fifth top 10 hit. The song also reached numbers two and eight on the US Latin Pop Songs and Tropical/Salsa charts, respectively. The first accompanying music videos for the original song and Pablo Flores remix were filmed in La Boca, a barrio of Buenos Aires, Argentina. Following "(Un, Dos, Tres) María"'s success in France, a re-made version of the video for the Pablo Flores remix was filmed in Paris and aired in 1998.

Although Martin was satisfied with the track and he describes it as a song that he is "extremely proud of", the first time he played it for a record label executive, the man said: "Are you crazy? You have ruined your career! I can't believe you are showing me this. You're finished — this is going to be your last album." In an interview with Rolling Stone, he told the magazine that "everybody got scared. They said, 'What are you doing? This is the end of your career. […] You do ballads, and now you're doing Latin sounds. The album is not going to work.'"

In 2018, Cadena Dial hailed the song as the most famous song of the last 24 years. In the same year, Rolling Stone ranked "María (Pablo Flores Remix)" as the 27th Greatest Latin Pop Song of All Time. Also, according to ABC, "María" was voted the favorite song of the summer of all time in Spain, based on a study in 2011. Amazon Music ranked the track as the 31st best-ever Latin hit. It was recognized as one of the best-performing songs of the year at the 1997 BMI Latin Awards. "María" was the main theme of the Brazilian telenovela Salsa e Merengue (1996–1997). The song is available on the main setlist for the dance video game Just Dance 2014. "María (Pablo Flores Spanglish Radio Edit)" was featured in the American animated comedy film Despicable Me 3 (2017).

"María" received a total of 71,8% yes votes! Previous Ricky Martin polls: #132 "La Bomba".

youtube

youtube

346 notes

·

View notes

Text

Emil Ferris’s long-awaited “My Favorite Thing Is Monsters Book Two”

NEXT WEEKEND (June 7–9), I'm in AMHERST, NEW YORK to keynote the 25th Annual Media Ecology Association Convention and accept the Neil Postman Award for Career Achievement in Public Intellectual Activity.

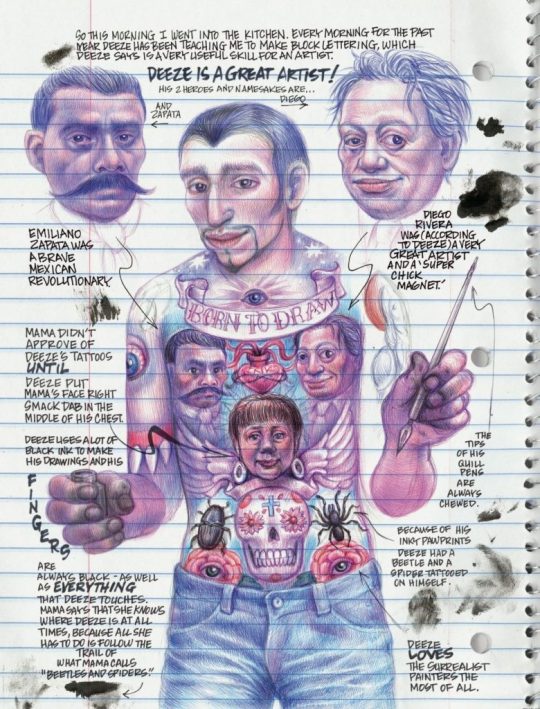

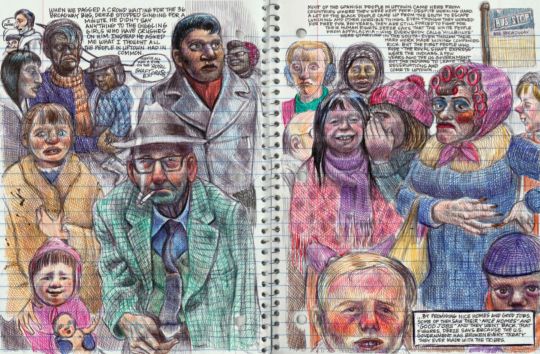

Seven years ago, I was absolutely floored by My Favorite Thing Is Monsters, a wildly original, stunningly gorgeous, haunting and brilliant debut graphic novel from Emil Ferris. Every single thing about this book was amazing:

https://memex.craphound.com/2017/06/20/my-favorite-thing-is-monsters-a-haunting-diary-of-a-young-girl-as-a-dazzling-graphic-novel/

The more I found out about the book, the more amazed I became. I met Ferris at that summer's San Diego Comic Con, where I learned that she had drawn it over a while recovering from paralysis of her right – dominant – hand after a West Nile Virus infection. Each meticulously drawn and cross-hatched page had taken days of work with a pen duct-taped to her hand, a project of seven years.

The wild backstory of the book's creation was matched with a wild production story: first, Ferris's initial publisher bailed on her because the book was too long; then her new publisher's first shipment of the book was seized by the South Korean state bank, from the Panama Canal, when the shipper went bankrupt and its creditors held all its cargo to ransom.

My Favorite Thing Is Monsters told the story of Karen Reyes, a 10 year old, monster-obsessed queer girl in 1968 Chicago who lives with her working-class single mother and her older brother, Deeze, in an apartment house full of mysterious, haunted adults. There's the landlord – a gangster and his girlfriend – the one-eyed ventriloquist, and the beautiful Holocaust survivor and her jazz-drummer husband.

Karen narrates and draws the story, depicting herself as a werewolf in a detective's trenchcoat and fedora, as she tries to unravel the secrets kept by the grownups around her. Karen's life is filled with mysteries, from the identity of her father (her brother, a talented illustrator, has removed him from all the family photos and redrawn him as the Invisible Man) to the purpose of a mysterious locked door in the building's cellar.

But the most pressing mystery of all is the death of her upstairs neighbor, the beautiful Annika Silverberg, a troubled Holocaust survivor whose alleged suicide just doesn't add up, and Karen – who loved and worshiped Annika – is determined to get to the bottom of it.

Karen is tormented by the adults in her life keeping too much from her – and by their failure to shield her from life's hardest truths. The flip side of Karen's frustration with adult secrecy is her exposure to adult activity she's too young to understand. From Annika's cassette-taped oral history of her girlhood in an Weimar brothel and her escape from a Nazi concentration camp, to the sex workers she sees turning tricks in cars and alleys in her neighborhood, to the horrors of the Vietnam war, Karen's struggle to understand is characterized by too much information, and too little.

Ferris's storytelling style is dazzling, and it's matched and exceeded by her illustration style, which is grounded in the classic horror comics of the 1950s and 1960s. Characters in Karen's life – including Karen herself – are sometimes depicted in the EC horror style, and that same sinister darkness crowds around the edges of her depictions of real-world Chicago.

These monster-comic throwbacks are absolute catnip for me. I, too, was a monster-obsessed kid, and spent endless hours watching, drawing, and dreaming about this kind of monster.

But Ferris isn't just a monster-obsessive; she's also a formally trained fine artist, and she infuses her love of great painters into Deeze, Karen's womanizing petty criminal of an older brother. Deeze and Karen's visits to the Art Institute of Chicago are commemorated with loving recreations of famous paintings, which are skillfully connected to pulp monster art with a combination of Deeze's commentary and Ferris's meticulous pen-strokes.

Seven years ago, Book One of My Favorite Thing Is Monsters absolutely floored me, and I early anticipated Book Two, which was meant to conclude the story, picking up from Book One's cliff-hanger ending. Originally, that second volume was scheduled for just a few months after Book One's publication (the original manuscript for Book One ran to 700 pages, and the book had been chopped down for publication, with the intention of concluding the story in another volume).

But the book was mysteriously delayed, and then delayed again. Months stretched into years. Stranger rumors swirled about the second volume's status, compounded by the bizarre misfortunes that had befallen book one. Last winter, Bleeding Cool's Rich Johnston published an article detailing a messy lawsuit between Ferris and her publishers, Fantagraphics:

https://bleedingcool.com/comics/fantagraphics-sued-emil-ferris-over-my-favorite-thing-is-monsters/

The filings in that case go some ways toward resolve the mystery of Book Two's delay, though the contradictory claims from Ferris and her publisher are harder to sort through than the mysteries at the heart of Monsters. The one sure thing is that writer and publisher eventually settled, paving the way for the publication of the very long-awaited Book Two:

https://www.fantagraphics.com/products/my-favorite-thing-is-monsters-book-two

Book Two picks up from Book One's cliffhanger and then rockets forward. Everything brilliant about One is even better in Two – the illustrations more lush, the fine art analysis more pointed and brilliant, the storytelling more assured and propulsive, the shocks and violence more outrageous, the characters more lovable, complex and grotesque.

Everything about Two is more. The background radiation of the Vietnam War in One takes center stage with Deeze's machinations to beat the draft, and Deeze and Karen being ensnared in the Chicago Police Riots of '68. The allegories, analysis and reproductions of classical art get more pointed, grotesque and lavish. Annika's Nazi concentration camp horrors are more explicit and more explicitly connected to Karen's life. The queerness of the story takes center stage, both through Karen's first love and the introduction of a queer nightclub. The characters are more vivid, as is the racial injustice and the corruption of the adult world.

I've been staring at the spine of My Favorite Thing Is Monsters Book One on my bookshelf for seven years. Partly, that's because the book is such a gorgeous thing, truly one of the great publishing packages of the century. But mostly, it's because I couldn't let go of Ferris's story, her characters, and her stupendous art.

After seven years, it would have been hard for Book Two to live up to all that anticipation, but goddammit if Ferris didn't manage to meet and exceed everything I could have hoped for in a conclusion.

There's a lot of people on my Christmas list who'll be getting both volumes of Monsters this year – and that number will only go up if Fantagraphics does some kind of slipcased two-volume set.

In the meantime, we've got more Ferris to look forward to. Last April, she announced that she had sold a prequel to Monsters and a new standalone two-volume noir murder series to Pantheon Books:

https://twitter.com/likaluca/status/1648364225855733769

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/06/01/the-druid/#oh-my-papa

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

The tides are turning. After Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s visit, Panama has AGREED to:

Grant U.S. Navy ships FREE passage through the Panama Canal.

TERMINATE its canal deal with China—cutting Beijing’s grip on global trade.

EXIT China’s 2017 ‘Belt and Road Initiative’—ending CCP influence in the region.

🔥 This is a MAJOR blow to China’s expansionist agenda and a massive WIN for American dominance. The globalist order is crumbling, and the U.S. is BACK. 🔥

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

imperialism and science reading list

edited: by popular demand, now with much longer list of books

Of course Katherine McKittrick and Kathryn Yusoff.

People like Achille Mbembe, Pratik Chakrabarti, Rohan Deb Roy, Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert, and Elizabeth Povinelli have written some “classics” and they track the history/historiography of US/European scientific institutions and their origins in extraction, plantations, race/slavery, etc.

Two articles I’d recommend as a summary/primer:

Zaheer Baber. “The Plants of Empire: Botanic Gardens, Colonial Power and Botanical Knowledge.” Journal of Contemporary Asia. May 2016.

Kathryn Yusoff. “The Inhumanities.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers. 2020.

Then probably:

Irene Peano, Marta Macedo, and Colette Le Petitcorps. “Introduction: Viewing Plantations at the Intersection of Political Ecologies and Multiple Space-Times.” Global Plantations in the Modern World: Sovereignties, Ecologies, Afterlives. 2023.

Sharae Deckard. “Paradise Discourse, Imperialism, and Globalization: Exploiting Eden.” 2010. (Chornological overview of development of knowledge/institutions in relationship with race, slavery, profit as European empires encountered new lands and peoples.)

Gregg Mitman. “Forgotten Paths of Empire: Ecology, Disease, and Commerce in the Making of Liberia’s Plantation Economy.” Environmental History. 2017, (Interesting case study. US corporations were building fruit plantations in Latin America and rubber plantations in West Africa during the 1920s. Medical doctors, researchers, and academics made a strong alliance these corporations to advance their careers and solidify their institutions. By 1914, the director of Harvard’s Department of Tropical Medicine was also simultaneously the director of the Laboratories of the Hospitals of the United Fruit Company, which infamously and brutally occupied Central America. This same Harvard doctor was also a shareholder in rubber plantations, and had a close personal relationship with the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, which occupied West Africa.)

Elizabeth DeLoughrey. “Globalizing the Routes of Breadfruit and Other Bounties.” 2008. (Case study of how British wealth and industrial development built on botany. Examines Joseph Banks; Kew Gardens; breadfruit; British fear of labor revolts; and the simultaneous colonizing of the Caribbean and the South Pacific.)

Elizabeth DeLoughrey. “Satellite Planetarity and the Ends of the Earth.” 2014. (Indigenous knowledge systems; “nuclear colonialism”; US empire in the Pacific; space/satellites; the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.)

Fahim Amir. “Cloudy Swords.” e-flux Journal #115, February 2021. (”Pest control”; termites; mosquitoes; fear of malaria and other diseases during German colonization of Africa and US occupations of Panama and the wider Caribbean; origins of some US institutions and the evolution of these institutions into colonial, nationalist, and then NGO forms over twentieth century.)

Some of the earlier generalist classic books that explicitly looked at science as a weapon of empires:

Schiebinger’s Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World; Delbourgo’s and Dew’s Science and Empire in the Atlantic World; the anthology Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World; Canzares-Esquerra’s Nature, Empire, and Nation: Explorations of the History of Science in the Iberian World.

One of the quintessential case studies of science in the service of empire is the British pursuit of quinine and the inoculation of their soldiers and colonial administrators to safeguard against malaria in Africa, India, and Southeast Asia at the height of their power. But there are so many other exemplary cases: Britain trying to domesticate and transplant breadfruit from the South Pacific to the Caribbean to feed laborers to prevent slave uprisings during the age of the Haitian Revolution. British colonial administrators smuggling knowledge of tea cultivation out of China in order to set up tea plantations in Assam. Eugenics, race science, biological essentialism, etc. in the early twentieth century. With my interests, my little corner of exposure/experience has to do mostly with conceptions of space/place; interspecies/multispecies relationships; borderlands and frontiers; Caribbean; Latin America; islands. So, a lot of these recs are focused there. But someone else would have better recs, especially depending on your interests. For example, Chakrabarti writes about history of medicine/healthcare. Paravisini-Gebert about extinction and Caribbean relationship to animals/landscape. Deb Roy focuses on insects and colonial administration in South Asia. Some scholars focus on the historiography and chronological trajectory of “modernity” or “botany” or “universities/academia,”, while some focus on Early Modern Spain or Victorian Britain or twentieth-century United States by region. With so much to cover, that’s why I’d recommend the articles above, since they’re kinda like overviews.Generally I read more from articles, essays, and anthologies, rather than full-length books.

Some other nice articles:

(On my blog, I’ve got excerpts from all of these articles/essays, if you want to search for or read them.)

Katherine McKittrick. “Dear April: The Aesthetics of Black Miscellanea.” Antipode. First published September 2021.

Katherine McKittrick. “Plantation Futures.” Small Axe. 2013.

Antonio Lafuente and Nuria Valverde. “Linnaean Botany and Spanish Imperial Biopolitics.” A chapter in: Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World. 2004.

Kathleen Susan Murphy. “A Slaving Surgeon’s Collection: The Pursuit of Natural History through the British Slave Trade to Spanish America.” 2019. And also: “The Slave Trade and Natural Science.” In: Oxford Bibliographies in Atlantic History. 2016.

Timothy J. Yamamura. “Fictions of Science, American Orientalism, and the Alien/Asian of Percival Lowell.” 2017.

Elizabeth Bentley. “Between Extinction and Dispossession: A Rhetorical Historiography of the Last Palestinian Crocodile (1870-1935).” 2021.

Pratik Chakrabarti. “Gondwana and the Politics of Deep Past.” Past & Present 242:1. 2019.

Jonathan Saha. “Colonizing elephants: animal agency, undead capital and imperial science in British Burma.” BJHS Themes. British Society for the History of Science. 2017.

Zoe Chadwick. “Perilous plants, botanical monsters, and (reverse) imperialism in fin-de-siecle literature.” The Victorianist: BAVS Postgraduates. 2017.

Dante Furioso: “Sanitary Imperialism.” Jeremy Lee Wolin: “The Finest Immigration Station in the World.” Serubiri Moses. “A Useful Landscape.” Andrew Herscher and Ana Maria Leon. “At the Border of Decolonization.” All from e-flux.

William Voinot-Baron. “Inescapable Temporalities: Chinook Salmon and the Non-Sovereignty of Co-Management in Southwest Alaska.” 2019.

Rohan Deb Roy. “White ants, empire, and entomo-politics in South Asia.” The Historical Journal. 2 October 2019.

Rohan Deb Roy. “Introduction: Nonhuman Empires.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 35 (1). May 2015.

Lawrence H. Kessler. “Entomology and Empire: Settler Colonial Science and the Campaign for Hawaiian Annexation.” Arcadia (Spring 2017).

Sasha Litvintseva and Beny Wagner. “Monster as Medium: Experiments in Perception in Early Modern Science and Film.” e-flux. March 2021.

Lesley Green. “The Changing of the Gods of Reason: Cecil John Rhodes, Karoo Fracking, and the Decolonizing of the Anthropocene.” e-flux Journal Issue #65. May 2015.

Martin Mahony. “The Enemy is Nature: Military Machines and Technological Bricolage in Britain’s ‘Great Agricultural Experiment.’“ Environment and Society Portal, Arcadia. Spring 2021.

Anna Boswell. “Anamorphic Ecology, or the Return of the Possum.” 2018. And; “Climates of Change: A Tuatara’s-Eye View.”2020. And: “Settler Sanctuaries and the Stoat-Free State." 2017.

Katherine Arnold. “Hydnora Africana: The ‘Hieroglyphic Key’ to Plant Parasitism.” Journal of the History of Ideas - JHI Blog - Dispatches from the Archives. 21 July 2021.

Helen F. Wilson. “Contact zones: Multispecies scholarship through Imperial Eyes.” Environment and Planning. July 2019.

Tom Brooking and Eric Pawson. “Silences of Grass: Retrieving the Role of Pasture Plants in the Development of New Zealand and the British Empire.” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. August 2007.

Kirsten Greer. “Zoogeography and imperial defence: Tracing the contours of the Neactic region in the temperate North Atlantic, 1838-1880s.” Geoforum Volume 65. October 2015. And: “Geopolitics and the Avian Imperial Archive: The Zoogeography of Region-Making in the Nineteenth-Century British Mediterranean.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2013,

Marco Chivalan Carrillo and Silvia Posocco. “Against Extraction in Guatemala: Multispecies Strategies in Vampiric Times.” International Journal of Postcolonial Studies. April 2020.

Laura Rademaker. “60,000 years is not forever: ‘time revolutions’ and Indigenous pasts.” Postcolonial Studies. September 2021.

Paulo Tavares. “The Geological Imperative: On the Political Ecology of the Amazon’s Deep History.” Architecture in the Anthropocene. Edited by Etienne Turpin. 2013.

Kathryn Yusoff. “Geologic Realism: On the Beach of Geologic Time.” Social Text. 2019. And: “The Anthropocene and Geographies of Geopower.” Handbook on the Geographies of Power. 2018. And: “Climates of sight: Mistaken visbilities, mirages and ‘seeing beyond’ in Antarctica.” In: High Places: Cultural Geographies of Mountains, Ice and Science. 2008. And:“Geosocial Formations and the Anthropocene.” 2017. And: “An Interview with Elizabeth Grosz: Geopower, Inhumanism and the Biopolitical.” 2017.

Mara Dicenta. “The Beavercene: Eradication and Settler-Colonialism in Tierra del Fuego.” Arcadia. Spring 2020.

And then here are some books:

Frontiers of Science: Imperialism and Natural Knowledge in the Gulf South Borderlands, 1500-1850 (Cameron B. Strang); Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (Londa Schiebinger, 2004);

Africa as a Living Laboratory: Empire, Development, and the Problem of Scientific Knowledge, 1870-1950 (Helen Tilley, 2011); Colonizing Animals: Interspecies Empire in Myanmar (Jonathan Saha); Fluid Geographies: Water, Science and Settler Colonialism in New Mexico (K. Maria D. Lane, 2024); Geopolitics, Culture, and the Scientific Imaginary in Latin America (Edited by del Pilar Blanco and Page, 2020)

Red Coats and Wild Birds: How Military Ornithologists and Migrant Birds Shaped Empire (Kirsten A. Greer); The Black Geographic: Praxis, Resistance, Futurity (Hawthorne and Lewis, 2022); Fugitive Science: Empiricism and Freedom in Early African American Culture (Britt Rusert, 2017)

The Empirical Empire: Spanish Colonial Rule and the Politics of Knowledge (Arndt Brendecke, 2016); In the Museum of Man: Race, Anthropology, and Empire in France, 1850-1960 (Alice Conklin, 2013); Unfreezing the Arctic: Science, Colonialism, and the Transformation of Inuit Lands (Andrew Stuhl)

Anglo-European Science and the Rhetoric of Empire: Malaria, Opium, and British Rule in India, 1756-1895 (Paul Winther); Peoples on Parade: Exhibitions, Empire, and Anthropology in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Sadiah Qureshi, 2011); Practical Matter: Newton’s Science in the Service of Industry and Empire, 1687-1851 (Margaret Jacob and Larry Stewart)

Pasteur’s Empire: Bacteriology and Politics in France, Its Colonies, and the World (Aro Velmet, 2022); Medicine and Empire, 1600-1960 (Pratik Chakrabarti, 2014); Colonial Geography: Race and Space in German East Africa, 1884-1905 (Matthew Unangst, 2022);

The Nature of German Imperialism: Conservation and the Politics of Wildlife in Colonial East Africa (Bernhard Gissibl, 2019); Curious Encounters: Voyaging, Collecting, and Making Knowledge in the Long Eighteenth Century (Edited by Adriana Craciun and Mary Terrall, 2019)

The Ends of Paradise: Race, Extraction, and the Struggle for Black Life in Honduras (Chirstopher A. Loperena, 2022); Mining Language: Racial Thinking, Indigenous Knowledge, and Colonial Metallurgy in the Early Modern Iberian World (Allison Bigelow, 2020); The Herds Shot Round the World: Native Breeds and the British Empire, 1800-1900 (Rebecca J.H. Woods); American Tropics: The Caribbean Roots of Biodiversity Science (Megan Raby, 2017); Producing Mayaland: Colonial Legacies, Urbanization, and the Unfolding of Global Capitalism (Claudia Fonseca Alfaro, 2023); Unnsettling Utopia: The Making and Unmaking of French India (Jessica Namakkal, 2021)

Domingos Alvares, African Healing, and the Intellectual History of the Atlantic World (James Sweet, 2011); A Temperate Empire: Making Climate Change in Early America (Anya Zilberstein, 2016); Educating the Empire: American Teachers and Contested Colonization in the Philippines (Sarah Steinbock-Pratt, 2019); Soundings and Crossings: Doing Science at Sea, 1800-1970 (Edited by Anderson, Rozwadowski, et al, 2016)

Possessing Polynesians: The Science of Settler Colonial Whiteness in Hawai’i and Oceania (Maile Arvin); Overcoming Niagara: Canals, Commerce, and Tourism in the Niagara-Great Lakes Borderland Region, 1792-1837 (Janet Dorothy Larkin, 2018); A Great and Rising Nation: Naval Exploration and Global Empire in the Early US Republic (Michael A. Verney, 2022)

Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment (Daniela Cleichmar, 2012); Tea Environments and Plantation Culture: Imperial Disarray in Eastern India (Arnab Dey, 2022); Drugs on the Page: Pharmacopoeias and Healing Knowledge in the Early Modern Atlantic World (Edited by Crawford and Gabriel, 2019)

Cooling the Tropics: Ice, Indigeneity, and Hawaiian Refreshment (Hi’ilei Kawehipuaakahaopulani Hobart, 2022); In Asian Waters: Oceanic Worlds from Yemen to Yokkohama (Eric Tagliacozzo); Yellow Fever, Race, and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century New Orleans (Urmi Engineer Willoughby, 2017); Turning Land into Capital: Development and Dispossession in the Mekong Region (Edited by Hirsch, et al, 2022); Mining the Borderlands: Industry, Capital, and the Emergence of Engineers in the Southwest Territories, 1855-1910 (Sarah E.M. Grossman, 2018)

Knowing Manchuria: Environments, the Senses, and Natural Knowledge on an Asian Borderland (Ruth Rogaski); Colonial Fantasies, Imperial Realities: Race Science and the Making of Polishness on the Fringes of the German Empire, 1840-1920 (Lenny A. Urena Valerio); Against the Map: The Politics of Geography in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Adam Sills, 2021)

Under Osman’s Tree: The Ottoman Empire, Egypt, and Environmental History (Alan Mikhail, 2017); Imperial Nature: Joseph Hooker and the Practices of Victorian Science (Jim Endersby); Proving Grounds: Militarized Landscapes, Weapons Testing, and the Environmental Impact of U.S. Bases (Edited by Edwin Martini, 2015)

Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World (Multiple authors, 2007); Space in the Tropics: From Convicts to Rockets in French Guiana (Peter Redfield); Seeds of Empire: Cotton, Slavery, and the Transformation of the Texas Borderlands, 1800-1850 (Andrew Togert, 2015); Dust Bowls of Empire: Imperialism, Environmental Politics, and the Injustice of ‘Green’ Capitalism (Hannah Holleman, 2016); Postnormal Conservation: Botanic Gardens and the Reordering of Biodiversity Governance (Katja Grotzner Neves, 2019)

Botanical Entanglements: Women, Natural Science, and the Arts in Eighteenth-Century England (Anna K. Sagal, 2022); The Platypus and the Mermaid and Other Figments of the Classifying Imagination (Harriet Ritvo); Rubber and the Making of Vietnam: An Ecological History, 1897-1975 (Michitake Aso); A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (Kathryn Yusoff, 2018); Staple Security: Bread and Wheat in Egypt (Jessica Barnes, 2023); No Wood, No Kingdom: Political Ecology in the English Atlantic (Keith Pluymers); Planting Empire, Cultivating Subjects: British Malaya, 1768-1941 (Lynn Hollen Lees, 2017); Fish, Law, and Colonialism: The Legal Capture of Salmon in British Columbia (Douglas C. Harris, 2001); Everywhen: Australia and the Language of Deep Time (Edited by Ann McGrath, Laura Rademaker, and Jakelin Troy)

Subject Matter: Technology, the Body, and Science on the Anglo-American Frontier, 1500-1676 (Joyce Chaplin, 2001); Mapping the Amazon: The Making and Unmaking of French India (Jessica Namakkal, 2021)

American Lucifers: The Dark History of Artificial Light, 1750-1865 (Jeremy Zallen); Ruling Minds: Psychology in the British Empire (Erik Linstrum, 2016); Lakes and Empires in Macedonian History: Contesting the Water (James Pettifer and Mirancda Vickers, 2021); Inscriptions of Nature: Geology and the Naturalization of Antiquity (Pratik Chakrabarti); Seeds of Control: Japan’s Empire of Forestry in Colonial Korea (David Fedman)

Do Glaciers Listen?: Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters, and Social Imagination (Julie Cruikshank); The Fishmeal Revolution: The Industrialization of the Humboldt Current Ecosystem (Kristin A. Wintersteen, 2021); The Earth on Show: Fossils and the Poetics of Popular Science, 1802-1856 (Ralph O’Connor); An Imperial Disaster: The Bengal Cyclone of 1876 (Benjamin Kingsbury, 2018); Geographies of City Science: Urban Life and Origin Debates in Late Victorian Dublin (Tanya O’Sullivan, 2019)

American Hegemony and the Postwar Reconstruction of Science in Europe (John Krige, 2006); Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power: Race and the Intimate in Colonial Rule (Ann Laura Stoler, 2002); Rivers of the Sultan: The Tigris and Euphrates in the Ottoman Empire (Faisal H. Husain, 2021)

The Sanitation of Brazil: Nation, State, and Public Health, 1889-1930 (Gilberto Hochman, 2016); The Imperial Security State: British Colonial Knowledge and Empire-Building in Asia (James Hevia); Japan’s Empire of Birds: Aristocrats, Anglo-Americans, and Transwar Ornithology (Annika A. Culver, 2022)

Moral Ecology of a Forest: The Nature Industry and Maya Post-Conservation (Jose E. Martinez, 2021); Sound Relations: Native Ways of Doing Music History in Alaska (Jessica Bissette Perea, 2021); Citizens and Rulers of the World: The American Child and the Cartographic Pedagogies of Empire (Mashid Mayar); Anthropology and Antihumanism in Imperial Germany (Andrew Zimmerman, 2001)

The Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century (Multiple authors, 2016); The Nature of Slavery: Environment and Plantation Labor in the Anglo-Atlantic World (Katherine Johnston, 2022); Seeking the American Tropics: South Florida’s Early Naturalists (James A. Kushlan, 2020)

The Colonial Life of Pharmaceuticals: Medicines and Modernity in Vietnam (Laurence Monnais); Quinoa: Food Politics and Agrarian Life in the Andean Highlands (Linda J. Seligmann, 2023) ; Critical Animal Geographies: Politics, intersections and hierarchies in a multispecies world (Edited by Kathryn Gillespie and Rosemary-Claire Collard, 2017); Spawning Modern Fish: Transnational Comparison in the Making of Japanese Salmon (Heather Ann Swanson, 2022); Imperial Visions: Nationalist Imagination and Geographical Expansion in the Russian Far East, 1840-1865 (Mark Bassin, 2000); The Usufructuary Ethos: Power, Politics, and Environment in the Long Eighteenth Century (Erin Drew, 2022)

Intimate Eating: Racialized Spaces and Radical Futures (Anita Mannur, 2022); On the Frontiers of the Indian Ocean World: A History of Lake Tanganyika, 1830-1890 (Philip Gooding, 2022); All Things Harmless, Useful, and Ornamental: Environmental Transformation Through Species Acclimitization, from Colonial Australia to the World (Pete Minard, 2019)

Visions of Nature: How Landscape Photography Shaped Setller Colonialism (Jarrod Hore, 2022); Timber and Forestry in Qing China: Sustaining the Market (Meng Zhang, 2021); The World and All the Things upon It: Native Hawaiian Geographies of Exploration (David A. Chang);

Deep Cut: Science, Power, and the Unbuilt Interoceanic Canal (Christine Keiner); Writing the New World: The Politics of Natural History in the Early Spanish Empire (Mauro Jose Caraccioli); Two Years below the Horn: Operation Tabarin, Field Science, and Antarctic Sovereignty, 1944-1946 (Andrew Taylor, 2017); Mapping Water in Dominica: Enslavement and Environment under Colonialism (Mark W. Hauser, 2021)

To Master the Boundless Sea: The US Navy, the Marine Environment, and the Cartography of Empire (Jason Smith, 2018); Fir and Empire: The Transformation of Forests in Early Modern China (Ian Matthew Miller, 2020); Breeds of Empire: The ‘Invention’ of the Horse in Southeast Asia and Southern Africa 1500-1950 (Sandra Swart and Greg Bankoff, 2007)

Science on the Roof of the World: Empire and the Remaking of the Himalaya (Lachlan Fleetwood, 2022); Cattle Colonialism: An Environmental History of the Conquest of California and Hawai’i (John Ryan Fisher, 2017); Imperial Creatures: Humans and Other Animals in Colonial Singapore, 1819-1942 (Timothy P. Barnard, 2019)

An Ecology of Knowledges: Fear, Love, and Technoscience in Guatemalan Forest Conservation (Micha Rahder, 2020); Empire and Ecology in the Bengal Delta: The Making of Calcutta (Debjani Bhattacharyya, 2018); Imperial Bodies in London: Empire, Mobility, and the Making of British Medicine, 1880-1914 (Kristen Hussey, 2021)

Biotic Borders: Transpacific Plant and Insect Migration and the Rise of Anti-Asian Racism in America, 1890-1950 (Jeannie N. Shinozuka); Coral Empire: Underwater Oceans, Colonial Tropics, Visual Modernity (Ann Elias, 2019); Hunting Africa: British Sport, African Knowledge and the Nature of Empire (Angela Thompsell, 2015)

#multispecies#ecologies#tidalectics#geographic imaginaries#book recommendations#reading recommendations#reading list#my writing i guess

425 notes

·

View notes

Text

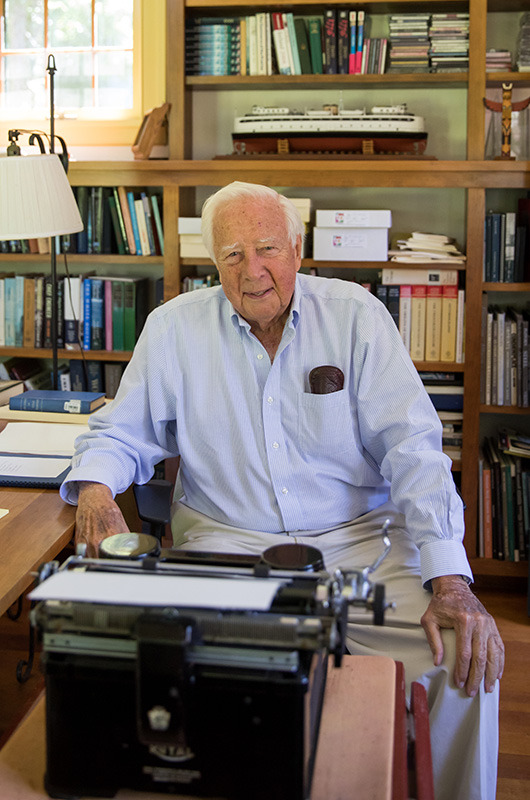

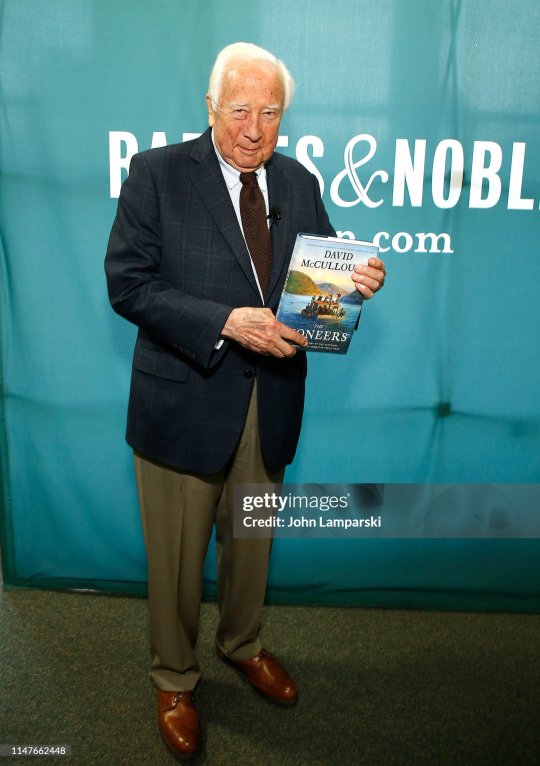

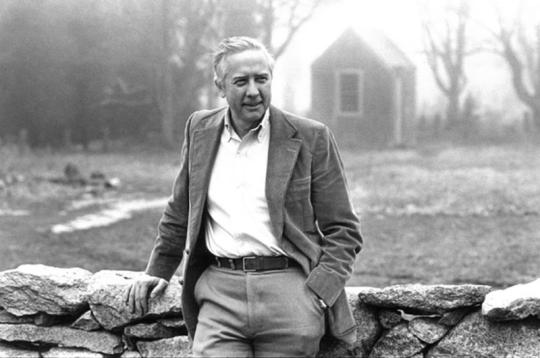

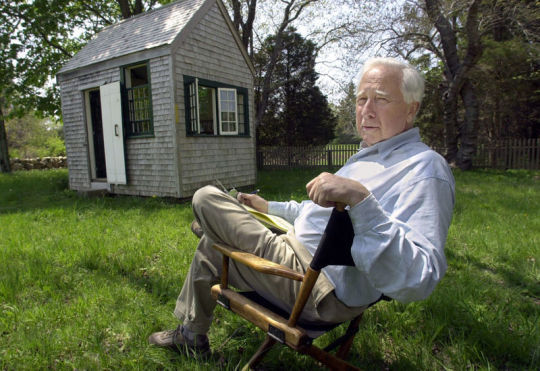

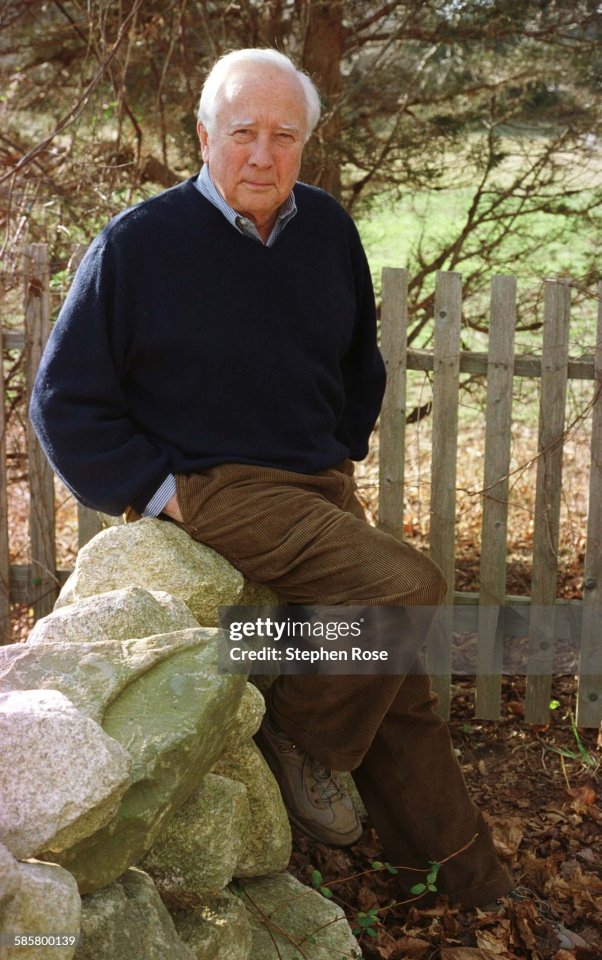

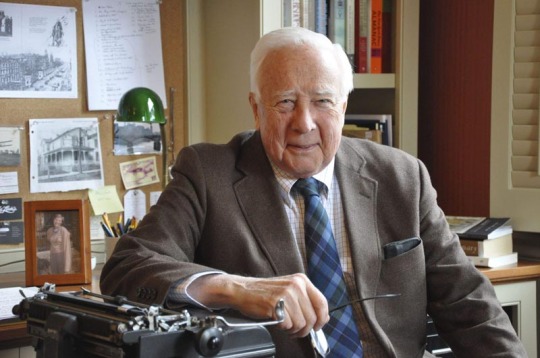

David McCullough

Physique: Average Build Height: 5' 11"

David Gaub McCullough (July 7, 1933 – August 7, 2022; aged 89) was an American popular historian. He was a two-time winner of both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. In 2006, he was given the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the United States' highest civilian award. McCullough's two Pulitzer Prize–winning books—Truman and John Adams—were adapted by HBO into a TV film and a miniseries, respectively.

Beyond his books, the handsome, white-haired McCullough may have had the most recognizable presence of any historian, his fatherly baritone known to fans of PBS’s The American Experience and Ken Burns’ epic Civil War documentary. Making me wanting to blow him all night long… although you probably didn't need to know that last bit. Just pretend you didn't read that. Anyway

Born and raised in Pittsburgh, McCullough earned a degree in English literature from Yale University in 1955. After working for twelve years in editing and writing, including a position at American Heritage, McCullough wrote in his spare time for three years. The Johnstown Flood was published in 1968 to high praise by critics. Despite rough financial times, he decided to become a full-time writer, encouraged by his wife Rosalee. He wrote nine more on such topics as Harry S. Truman, John Adams, Theodore Roosevelt, the Brooklyn Bridge, the Panama Canal, and the Wright brothers.

McCullough also narrated numerous documentaries as well as the 2003 film Seabiscuit, and he hosted the PBS television documentary series American Experience for twelve years.

Personally, all I know about him is that he was married to his childhood sweet heart, Rosalee Barnes (aww). They had five children, which goes to my "loves to fuck" theory. While at Yale, he became a member of Skull and Bones. And his interests included sports, history, and visual art, including watercolor and portrait painting. And he had a face that would've looked great on my cock. Again… pretend you didn't read that.

After a period of failing health, McCullough died at his home in Hingham on August 7, 2022, at age 89. Less than two months after his beloved wife, Rosalee. He was survived by his five children; 19 grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

Works The Johnstown Flood: The Incredible Story Behind One of the Most Devastating Disasters America Has Ever Known (1968) The Great Bridge: The Epic Story of the Building of the Brooklyn Bridge (1972) The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870–1914 (1977) Mornings on Horseback (1981) Brave Companions: Portraits in History (1991) Truman (1992) John Adams. (2001) 1776 (2005) In the Dark Streets Shineth: A 1941 Christmas Eve Story (2010) The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris (2011) The Wright Brothers (2015) The American Spirit: Who We Are and What We Stand For (2017) The Pioneers: The Heroic Story of the Settlers Who Brought the American Ideal West ( 2019)

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Panama has officially withdrawn from China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) following a meeting between Panamanian President and U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio. The move comes amid U.S. concerns over China’s growing influence in Panama’s ports, questioning the neutrality of the Panama Canal.

Since 2017, Panama was the first Latin American nation to join the BRI, aligning itself with Beijing’s global infrastructure ambitions. However, growing geopolitical tensions, especially regarding China’s control over critical trade routes, have led to this policy reversal. China has strongly opposed the decision, accusing the U.S. of coercion.

This marks a broader global trend, with Italy and Brazil also distancing themselves from the BRI, signaling a shift in international alignments.

#general knowledge#affairsmastery#generalknowledge#current events#current news#upscaspirants#upsc#generalknowledgeindia#world news#news#breaking news#government#trump administration#president trump#president donald trump#donald trump#trump#republicans#usa news#usa#us politics#america#politics#international news#panama#panama canal#latin america#china#shipping#geopolitics

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Project2025 #TechBros #CorpMedia #Oligarchs #MegaBanks vs #Union #Occupy #NoDAPL #BLM #SDF #DACA #MeToo #Humanity #FeelTheBern

JinJiyanAzadi #BijiRojava

Trump And Putin: A Love Story

The Trump-Russia-Ukraine Timeline

Trump’s connections to Russia began more than 35 years ago and didn’t end on Election Day 2016…

05/10/2016 Panama Papers Leak: Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin and Others on the List

On Monday, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) released a searchable database of its Panama Papers. The database allows users to search through the Panama Papers and other records for individuals and corporations that might be using foreign shell companies and offshore accounts to keep financial information private…

Aug 17, 2016 Shady Foreign Lobbying Effort Implicates Trump AND Clinton Campaign Chairmen

Donald Trump’s campaign chairman Paul Manafort reportedly helped route more than $1 million in secret from a pro-Russian group in Ukraine to a Washington D.C. lobbying firm co-founded by Hillary Clinton’s campaign chairman, John Podesta…

08/19/16 Podesta Group retains outside counsel over Manafort-related scandal

A prominent D.C. lobbying firm has hired outside counsel over revelations that it may have been improperly involved in lobbying on behalf of pro-Russian Ukrainian politicians who also employed former Donald Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort…

Sunday 16 October 2016 As Donald Trump made clear, smart businesses know only idiots pay tax

The revelation that the US presidential candidate paid no federal taxes for 18 years will come as no surprise to the global corporations who funnel billions through tax havens…

13 December 2016 Rex Tillerson: an appointment that confirms Putin's US election win

The president-elect has chosen Exxon Mobil CEO as secretary of state but experts say Senate may bridle over realpolitik choice that would benefit Russia…

Dec 19, 2016 Follow The Money: Panama Papers Motherload of Ties Between Trump and Russian Mobster Oligarchs

This lengthy but enlightening article with a forward by David Cay Johnston and written by James Henry, shows just how important the Panama Papers were, if people had wanted to delve into the links between Russian oligarchs and Trump. Too bad people were all focused on “trade deals” that weren’t there to haunt us. All of this information should have been front and center. These people have been Drumpf’s business cohorts for decades. Some of them are apparent family friends. The kids hang out with them, too. It’s a long article and the source allows one free article, so take your time and read it. If only investigative journalists had been doing what James Henry has done and not gone for that shiny object…e-mails. There should be a massive Church Commission to investigate these relationships. Crimes and misdemeanors look like shiny objects to me…

24 January 2017 We broke the Panama Papers story. Here's how to investigate Donald Trump

We were successful because we collaborated with other journalists. Now it is time for the media to join forces once again – especially given the threat Trump poses…

Feb. 11, 2017 The timeline of Trump's ties with Russia lines up with allegations of conspiracy and misconduct

President Donald Trump and several associates continue to draw intense scrutiny for their ties to the Russian government…

FURTHER READING:

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Panama's President: Panama will not renew the memo 2017 with China on its Belt and Road Initiative. Panama will study the ability to end the agreement earlier than its end date in a year or two. This comes after SecState Rubio's visit to Panama today.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

If Donald Trump’s first days in the White House, in 2017, were about shock and awe—his haunting “American carnage” speech, the Muslim ban—the 2025 version, at least initially, felt more dutiful, a bit weirder, but ultimately not quite as scary. Trump 45 talked about a “new vision” to “govern our land” and promised his voters “you will never be ignored again.” Trump 47 seemed bored for the first half of his inaugural speech, then rambled on about Panama, Mars, and “the electric-vehicle mandate.” The flurry of executive orders that followed might have made for good headlines because they touched on culture-war topics such as trans rights and D.E.I., but outside of a few notable exceptions—withdrawing from the Paris Agreement and curbing renewable-energy programs—Trump’s first round of legislation mostly seemed like repurposed archival footage from his campaign, chopped up and stretched out into a new, thin form. The Gulf of Mexico is now the Gulf of America. Denali is once again Mount McKinley, because we’re not cancelling dead white men anymore, especially not for some tribe. D.E.I. is over at federal agencies and in the military. Now please go fight among yourselves about all this culture-war stuff while we deregulate everything.

This period of unhinged, but perhaps not so consequential, Trump theatre lasted until Monday, when his Office of Management and Budget released a memo freezing all federal spending “that may be implicated by the executive orders, including, but not limited to, financial assistance for foreign aid, nongovernmental organizations, DEI, woke gender ideology, and the green new deal.” We still don’t know the extent of the order, its legality, or who, exactly, it will affect, but the brazenness of the move suggests that Trump intends to run the country as a petty despot who values fealty to him over allegiance to the country. (The White House later rescinded the order, while also saying that the spending review remains in “full force and effect.” A judge has paused its implementation until February 3rd.)

Given the potential seriousness of Trump’s freeze, I think it’s good practice, especially after the recurring freakouts between 2016 and 2020, to point out when Trump mostly seems to be doing something for purely symbolic reasons and when he’s actually trying to get something done. The first Trump Administration and the constant stream of stories that ended in Russiagate ultimately desensitized much of the public to the actual bad things he was doing, disoriented the audience’s priorities, and might have even led to a quiet backlash or at least a sense of disbelief that Trump could actually be that bad. The renaming of bodies of water and mountains, for example, is easy enough to cast aside as Trumpian bluster, but what about the handful of executive orders Trump signed regarding D.E.I. which included the end of all such programs in the military and the federal government as well as the repeal of a 1965 executive order that prohibited federal contractors from discriminating on the basis of race, gender, and national origin? It’s still unclear how many employees will lose their jobs—the executive order calls for a list of everyone who might work in some D.E.I.-related endeavor and a review, which could either mean that everyone who has said a word about racial or gender equality or diversity will be out of work, or it could just mean that after a few high-profile firings of D.E.I. officers this list never really gets made, the review never happens, and everyone moves on to the next dimension of the culture war.

When the Supreme Court struck down affirmative action in college admissions two years ago, the outrage from liberals and Democratic elected officials was relatively muted. There are many possible explanations for this, most notably that perhaps the people who were the maddest about the decision didn’t have the same platforms as the people who either shrugged or cheered it on. But over all it seemed like much of the public agreed with Sandra Day O’Connor who, in an earlier ruling on affirmative action in 2003, famously said that affirmative action should not really be necessary in twenty-five years. The clock, it seemed, had run out. Similarly, I suspect most Americans won’t miss D.E.I., which has become another digital training you have to finish before you get your first paycheck and a way for management to control what their workers say. (I doubt they’ll cheer on its end, either, largely because I don’t think most Americans really care one way or another. A recent poll by YouGov, in fact, found around half of Americans had a somewhat or very favorable opinion of D.E.I. programs, and less than thirty per cent said that they had a very unfavorable opinion.) This isn’t really the fault of the employees who work in these programs. I’m sure most of them envisioned something a bit more radical or at least useful when they signed up, but, if you’re a college graduate with a humanities degree and want to make a salary while still vaguely doing something that deals with reducing racism in America, D.E.I. is one of the few possible career paths. The problem, at a grand scale, is that D.E.I.’s malleability and its ability to survive in pretty much every setting, whether it’s a nearby public school or the C.I.A., means that it has to be generic and ultimately inoffensive, which means that, in the end, D.E.I. didn’t really satisfy anyone.

What it did was provide a safety valve (I am speaking about D.E.I. in the past tense because I do think it will quickly be expunged from the private sector as well) for institutions that were dealing with racial and social-justice problems. If you had a protest on campus over any issue having to do with “diverse students” who wanted “equity,” that now became the provenance of D.E.I. officers who, if they were doing their job correctly, would defuse the situation and find some solution—oftentimes involving a task force—that made the picket line go away. A couple years ago, a D.E.I. officer at Stanford Law School went viral after she supported students who were shutting down a conservative guest speaker. I recall watching the video and feeling both a bit annoyed at yet another instance of pointless and ultimately counterproductive “resistance” and also a bit sad because it was clear that the officer didn’t understand the point of her job. She wasn’t hired to actually join the protest against the conservative speaker. Her job was to intervene, give the students a “space” to vent, and, ultimately, find a solution that didn’t end with Stanford Law going viral for an instance of campus cancel culture.

There’s also the argument that the growth of D.E.I. offices, especially after the George Floyd protests, led to an aggressive and potentially illegal push to hire racial minorities throughout corporate America and academia, which, in turn, led to an overextension and corruption of the original goal of enforcing fair hiring practices to insure that people of all kinds would not be discriminated against. But this narrative also fundamentally misunderstands the purpose of D.E.I. within large institutions. What happened in many workplaces across the country after 2020 was that the people in charge were either genuinely moved by the Floyd protests or they were scared. Both the inspired and the terrified built out a D.E.I. infrastructure in their workplaces. These new employees would be given titles like chief diversity officer or C.D.O., which made it seem like it was part of the C-suite, and would be given a spot at every table, but much like at Stanford Law, their job was simply to absorb and handle any race stuff that happened. D.E.I. didn’t hire itself at Meta. It was embraced by the company’s founder, Mark Zuckerberg, who gleefully ended his company’s program earlier this month, signalling to the White House and investors that the days of wokeness at Meta were over. This was the final purpose of D.E.I. programs in corporate America—when the political winds changed this past November, D.E.I. became the convenient fall guy; the best way to signal that you never wanted to do all that woke stuff in the first place was to fire your D.E.I. staff and blame them for forcing you down the wrong path.

Trump, I believe, is doing something similar at a grand scale. He is taking a relatively powerless program, vilifying it, and using its dissolution as proof that he has single-handedly ended the woke era. The clearest example came on Thursday when he outrageously blamed “diversity” for the tragic airline crash in Washington. When his O.M.B. gambit turned into a legal and political disaster this past week, Trump’s Administration retreated to a familiar, safe space. The funding freeze, they said, was only for the parts of the federal government directly affected by Trump’s earlier executive orders, the most prominent being D.E.I. He and his Administration are wielding the word “diversity” both as a slur and an excuse for everything that goes wrong in this country.

I suppose it’s possible that the elimination of D.E.I. might take away what was a dead-end solution and recommit people to more fruitful forms of protest and dissent, but politics rarely follows such a linear and satisfying script. I also do not think the end of D.E.I. will derail the desires of employers and their workers to have diverse workforces, nor do I think Trump will pay much attention to any of this down the line. On Wednesday, Tom Malinowski, a former congressman and diplomat, pointed out that Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency had just bragged about ending “DEI scholarships for Burma.” The scholarships in question are through U.S.A.I.D. and granted to young people who are fighting against the dictatorship in Burma, which, as Malinowski noted, has long been a priority in Washington for Democrats and Republicans, including the new Secretary of State, Marco Rubio. “It looks like these geniuses are just going through grant awards and killing anything that uses words like ‘diversity’ and ‘inclusion,’ even though in countries where ethnic and religious minorities are murdered and persecuted, these have long been American goals,” Malinowski speculated.

One can imagine Musk and his staff hitting Control+F on a database of grants for the word “equity,” cancelling any search returns without reading what they’re actually for, and then screenshotting the paperwork to post on Twitter. But this snickering for clout doesn’t mean there shouldn’t be a great deal of alarm. These first two weeks of Trump’s Presidency have made it clear that his main priority, at least for now, is controlling federal funding and using it to enrich his allies and to harm his political enemies. In California, he told Gavin Newsom that he would make aid for cleaning up the devastating fires in Los Angeles conditional, in part, on the development of a voter-I.D. program. This past Friday, seventeen inspectors general were fired, which effectively removed independent oversight at a multitude of federal agencies. On Monday, the Department of Justice fired around a dozen employees who had worked with Jack Smith, the special counsel assigned to prosecute Trump, saying that they could no longer be trusted. Trump’s endgame has started to reveal itself and it will not be coming through the tired culture war we have all been fighting for the past decade but rather through the bureaucracy. Whatever rises to enforce or resist it will not sit nicely in a corporate or academic office, nor will it be neatly summarized through words like “woke” or “anti-woke,” or the endless campus wars. The next four years, instead, will be filled with true extremism on both the left and the right that will make supposedly out-of-control D.E.I. feel like a quaint company retreat in comparison.

So, yes, the war on D.E.I. is almost certainly a catchall scapegoat meant to distract from Trump’s larger plans to gut the federal government, but I also can’t imagine it will hold the public’s attention, just as a similar focus on racial politics in academia and élite corporations did not work for Ron DeSantis during his failed run for President. The American public elected Donald Trump, but between social-justice warriors, “woke,” and D.E.I., the right has now been fighting the same tired culture war for more than a decade, and it has largely lost the capacity to outrage anyone outside of a small set of terminally online, mostly conservative activists. Trump is going to need a better distraction, but one thing we know about him is that he stubbornly sticks to a theme. He might not be able to credibly blame diversity for everything from plane crashes to children’s reading scores, but I imagine he will try.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Proof of Good in Humanity: vol. 1

I am way too ADHD to promise a regular schedule of these, but I want to share stories of people who prove that, when it counts, people can and will do the right thing. Not everyone, and not every time, but they do.

Today’s story is one from 2017 that has stayed with me so vividly that it’s the first that I think of when I hear about bigotry or divisiveness among people. It’s best told in this article by ABC News:

To sum up for those who want to skip the article:

As stated above, swimmers were caught in the current, couldn’t get back to shore. Cops were saying to wait for the coast guard, but the folks on shore wondered what most of us would… are they gonna get there fast enough?

So one couple encouraged everyone to form a human chain out to them… and they did it, and it saved them all! Even people who said they wouldn’t go out there, that they were afraid they’d be swept away, joined the chain… which is just as courageous as the people who never hesitated, maybe even a little bit more. All walks of human life were in that chain.

My commentary:

What struck me about this, besides the obvious good feelings that come from seeing the best in humanity, is that no one is asking personal questions in a crisis. No one is saying you brought it on yourself and you deserve what you get. At least I hope not.

One young honeymoon couple got caught themselves trying to help. They were both women. No one was refusing their help, or to help them, because of that. It wasn’t important. Race, religion, politics, orientation… none of it was relevant. All that mattered was saving lives.

It was that couple that brought it home to me… in a crisis, most people, who will jump in at all, do it without asking who they’re saving. And that tells you what really matters in a crisis.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Immaculate Conception of the Glorious and Ever-Virgin Mary, Mother of God – 8 December. Patronages – barrel makers, coopers, cloth makers, cloth workers, soldiers of the United States, Spanish infantry, tapestry workers, upholsterers, Argentina, Brazil, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Guam, Nicaragua, Panama, Portugal, Tanzania, Tunisia, United States, 68 Diocese, 8 Cities. HERE: https://anastpaul.com/2021/12/08/the-solemnity-of-the-immaculate-conception-of-the-blessed-virgin-mary-8-december-2/ AND: https://anastpaul.com/2017/12/08/the-feast-of-the-immaculate-conception-solemnity-8-december/ AND: https://anastpaul.com/2018/12/08/8-december-the-solemnity-of-the-immaculate-conception/

(via The Immaculate Conception of the Glorious and Ever-Virgin Mary, Mother of God, The Second Sunday of Advent and Memorials of the Saints for 8 December – AnaStpaul)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

REDCAPS

I have never seen anything on Internet talking about the redcaps. So, Am I the only one who thinks Cassie chose that color, item, name because of MAGA? Like redcaps are loyal to the UnseelieKing, it doesn't mind what he does, his policies, ideas and how he treat the people they are loyal and MAGA sees Donld Trump the same way, they will literally excuse anything he says and does just because they are loyal to him.

I'm just writing this cause recently he has been saying things like -buying but they said they were not for sale so they changed it to- conquer the Panama Canal and Greenland by economic force ( i would be surprise if they us military force too like MAGA says they will if they dont accept, which they already say they are not for sale and havent been heard), changing the name of Gulf of Mexico to Gulf of America and buying/acquiring CANADA as the number 51 state.

And since Trump said all of that things and try all his MAGA are loyal to him. They are not loyal to his ideas, they couldn't care less, they are just rotten like a Cult.

It also have sense since she wrote those books when he was about be president and during his presidency 2017-2021.

Maybe I'm wrong but I think Cassie chose that item as a reference. And in that trilogy the hate to different was on point by the cohorts too, like it was a contagious sentiment and a dangerous too.

I also think the next hunger games book and the wicked powers will be fire because all of this politics and social problems

AND ALSO, u know what I'm going to say it in the next note, this one is long enough and I Don't want to change the subject away from redcaps

#the shadowhunter chronicles#kit x ty#ty blackthorn#the dark artifices#kit herondale#the wicked powers#shadowhunters#dru blackthorn#cassandraclare#livvy blackthorn#tmi#the infernal devices#the mortal instruments#redcaps#unseelie king#unseelie court

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The US wants to preemptively neutralize as many of the means as possible through which China could asymmetrically respond to this scenario in plausibly deniable ways such as by having its company that controls port facilities on both sides of the canal shut down transit in the event of a crisis.

Panamanian President Jose Raul Mulino declared after meeting with Secretary of State Marco Rubio that his country’s 2017 memorandum of understanding with China on the Belt & Road Initiative won’t be renewed and that it might even terminate the deal earlier. His policy shift was preceded by Trump threatening that “something very powerful is going to happen” if Panama doesn’t neutralize China’s influence over the canal and follows Rubio elaborating on the US’ perceived threat assessment.

He told Megyn Kelly last week that the Hong Kong-based company which built port facilities on both sides of the canal is under the Chinese government’s control and could thus shut down transit through that waterway as part of Beijing’s contingency planning in the event of a crisis with Washington. It’s unimportant whether others share this assessment since all that matters is that this is how Trump 2.0 sees everything and is the reason why it’s coercing Panama over the canal.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alright, let’s go for another novel species (though the paper describing them is almost 7 years old now, so not really). Here is Freeman’s Dog-faced Bat (Cynomops freemani). They are from the lowlands of the Pacific Coast in Panama [1].

Now originally they were first captured over a decade ago in 2012. They tend to fly very high, so it can be difficult to capture them in the nets usually used to trap bats, but not only did the original research group manage it, but a second did too in 2017 [2]. They can also be found to shelter in abandoned houses [1].

They’re insectivorous, meaning they feed on insects, which can be seen through their echolocation calls which are long and shallow. They do have different types of calls and the ability to modulate them as well. They are also rather small, being only about the length of a thumb [1].

They weren’t named after the person who discovered them, but rather a different bat scientist: Patricia Freeman. She spent decades studying free-tailed bats, which Freeman’s Dog-faced Bat is a species of, so this was considered a way of honouring her work. In response to finding out about this, Freeman said “It’s wicked cool, right?” [2].

Sources: [1] [2] [Image]

#I always feel awkward whenever I only have one or two sources#but like there hasn’t been much research on them since the paper describing them#and most newspaper articles only recite what is in the paper itself so like I don’t really have an option#critter of the day#critteroftheday#small mammal#bat#bat species#animal species#dog faced bat#zoology#animal#animal facts#mammal#bat facts#mammal species

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trump’s trade wars escalate as EU, Mexico, Canada retaliate

The global trade landscape is increasingly fraught as US President Donald Trump’s tariff policies spark retaliatory measures from the European Union, Mexico, Canada, and China, while a diplomatic dispute over China’s influence around the Panama Canal adds another layer of tension.

Trump reiterated his intent to impose tariffs on the EU, stating, “It will definitely happen with the European Union, I can tell you that.” He criticised the US trade deficit with the bloc and demanded greater imports of US cars and agricultural products.

However, he struck a softer tone on the UK, citing a good relationship with Prime Minister Keir Starmer, he warned that tariffs “might happen” unless trade imbalances are addressed.

Well Prime Minister Starmer’s been very nice, we’ve had a couple of meetings, we’ve had numerous phone calls, we’re getting along very well, we’ll see whether or not we can balance out our budget.

Meanwhile, Mexico and Canada responded to Trump’s tariffs with their own levies. Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum emphasised that “problems are not addressed by imposing tariffs, but with talks and dialogue,” whereas Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau vowed to “stand up for Canada.” The department of finance released a list of US products imported into Canada, facing retaliatory tariffs of 25% starting from Tuesday.

China, too, condemned Trump’s tariffs as a violation of World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules. A Chinese commerce ministry spokesperson added that Beijing would take countermeasures to “safeguard its own rights and interests.”

Trump acknowledged that his tariffs might cause “short-term pain” for Americans, but defended them as necessary to address long-standing trade imbalances. However, the economic impact is already being felt, with global markets slumping and consumers expressing frustration.

Panama Canal dispute with China

Meanwhile, tensions flared over China’s presence near the Panama Canal. US Secretary of State Marco Rubio warned Panama’s President José Raúl Mulino that Washington would “take measures necessary” if Panama failed to curb Beijing’s influence.

Rubio claimed that a Hong Kong-based company operating ports near the canal violated the US-Panama treaty, though Panama insisted the canal remained under its sovereign control.

Mulino signalled a willingness to review agreements with China, including a 2017 memorandum of understanding under the Belt and Road Initiative, but stressed that Panama’s sovereignty was non-negotiable.

We’ll study the possibility of terminating it early. I do not feel that there is any real threat at this time against the (neutrality) treaty, its validity, and much less the use of military force to make the treaty.

Trump, however, did not rule out forceful measures, stating, “China is running the Panama Canal that was not given to China, that was given to Panama foolishly, but they violated the agreement, and we’re going to take it back, or something very powerful is going to happen.”

However, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Mao Ning emphasised that China had no role in the operation of the canal and that it respected Panama’s sovereignty and independence over the waterway.

The escalating trade wars and Panama Canal dispute underscore the fragility of global economic relations under Trump’s “America First” policies. While his administration seeks to protect US interests, the retaliatory measures from key trading partners and the potential for military intervention in Panama risk destabilising international markets and alliances.

Read more HERE

#world news#news#world politics#usa#usa politics#usa news#united states#united states of america#america#us politics#us news#us presidents#politics#donald trump#donald trump news#trump administration#trump#president trump#trade war#tarrifs#mexico#mexico news#canada#canada news#canada politics#canadian economy#europe#european news#european union#eu politics

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Had to organize some more of my notes.

Some recently published books on inter/transnationalism (especially Black) in the Americas (focus on disability/health and knowledge/art appropriation).

---

Art, music, knowledge (and commodification):

Rude Citizenship: Jamaican Popular Music, Copyright, and the Reverberations of Colonial Power (Larisa Kingston Mann, 2022)

West African Masking Traditions and Diaspora Masquerade Carnivals: History, Memory, and Transnationalism (Raphael Chijikoe Njoku, 2020)

At Home in Our Sounds: Music, Race, and Cultural Politics in Interwar Paris (Rachel Anne Gillett, 2021)

La Raza Cosmetica: Beauty, Identity, and Settler Colonialism in Postrevolutionary Mexico (Natasha Varner, 2020)

Maps of Sorrow: Migration and Music in the Construction of Precolonial AfroAsia (Sumangala Damodaran and Ari Sitas, 2023)

Queer African Cinemas (Lindsey Green-Simms, 2022)

Bossa Mundo: Brazilian Music in Transnational Media Industries (K.E. Goldschmitt, 2020)

The Geographies of African American Short Fiction (Kenton Rambsy, 2022)

Healing Knowledge in Atlantic Africa: Medical Encounters, 1500-1850 (Kalle Kananjoa, 2021)

---

General internationalism:

Transatlantic Radicalism: Socialist and Anarchist Exchanges in the 19th and 20th Centuries (Edited by Jacob and Kebler, University of Liverpool Press, 2021)

Voices of the Race: Black Newspapers in Latin America, 1870-1960 (Edited by Paulina L. Alberto, et al., 2022)

The Eastern Mediterranean and the Making of Global Radicalism, 1860-1914 (Ilham Khuri-Makdisi, 2010)

In a Sea of Empires: Networks and Crossings in the Revolutionary Caribbean (Vanessa Mongey, 2020)

Anarchists of the Caribbean: Countercultural Politics and Transnational Networks in the Age of US Expansion (Kirwin R. Shaffer, Cambridge University Press, 2020)

---

Caribbean:

Between Fitness and Death: Disability and Slavery in the Caribbean (Stefanie Hunt-Kennedy, 2020)

The Ends of Paradise: Race, Extraction, and the Struggle for Black Life in Honduras (Chirstopher A. Loperena, 2022.)

Panama in Black: Afro-Caribbean World Making in the Twentieth Century (Kaysha Corinealdi, 2022)

LGBTQ Politics in Nicaragua: Revolution, Dictatorship, and Social Movements (Karen Kampwirth, 2022)

Chocolate Surrealism: Music, Movement, Memory and History in the Circum-Caribbean (Njoroje M. Njoroje, 2016)

Fugitive Movements: Commemorating the Denmark Vesey Affair and Black Radical Antislavery in the Atlantic World (Edited by James O'Neill Spady, 2022)

The Creole Archipelago: Race and Borders in the Colonial Caribbean (Tessa Murphy, 2021)

Freedom's Captives: Slavery and Gradual Emancipation on the Colombian Black Pacific (Yesenia Barragan, 2021)

---

United States:

Welcome to Fairyland: Queer Miami before 1940 (Julio Capo Jr., 2017)

The Entangled Labor Histories of Brazil and the United States (Edited by Teizeira da Silva, et al., 2023)

Belly of the Beast: The Politics of Anti-Fatness as Anti-Blackness (Da'Shaun L. Harrison, 2021)

Confederate Exodus: Social and Environmental Forces in the Migration of U.S. Southerners to Brazil (Alan Marcus, 2021)

Country of the Cursed and the Driven: Slavery and the Texas Borderlands (Paul Barba, 2021)

Racial Migrations: New York City and the Revolutionary Politics of the Spanish Caribbean (Kirwin R. Shaffer, 2021)

Necropolis: Disease, Power, and Capitalism in the Cotton Kingdom (Kathryn Olivarius, 2022)

West of Slavery: The Southern Dream of a Transcontinental Empire (Kevin Waite, 2021)

---

More:

Transimperial Anxieties: The Making and Unmaking of Arab Ottomans in Sao Paulo, Brazil, 1850-1940 (Jose D. Najar, 2023)

South-South Solidarity and the Latin American Left (Jessica Stites Mor, 2022)

Reimagining the Gran Chaco: Identities, Politics, and the Environment in South America (Edited by Silvia Hirsch, Paola Canova, Mercedes Biocca, 2021)

Modernity in Black and White: Art and Image, Race and Identity in Brazil, 1890-1945 (Rafael Cardoso, 2020)

Region Out of Place: The Brazilian Northeast and the World, 1924-1968 (Courtney Campbell, 2022)

Selling Black Brazil: Race, Nation, and Visual Culture in Salvador, Bahia (Anadelia Romo, 2022)

Hiding in Plain Sight: Black Women, the Law, and the Making of a White Argentine Republic (Erika Denise Edwards, 2020)

Peripheral Nerve: Health and Medicine in Cold War Latin America (Edited by Anne-Emanuelle Birn and Raul Necochea Lopez, 2020)

#ecology#abolition#landscape#black music geography#reading recommendations#black methodologies#indigenous pedagogies#book recommendations#multispecies#tidalectics#ecologies

17 notes

·

View notes