#p: louise bourgeois

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

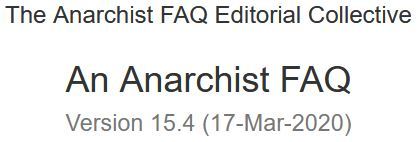

cloth panel from louise bourgeois’s 2009 piece eugénie grandet via all___kinds

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

wedge of chastity by marcel duchamp (1954, cast 1963) / tits by louise bourgeois (1967)

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

Everything I know about Louis De Végobre 1/? Part(s)

(I'm sure I'm forgetting some details hahaha)

Pierre-Louis-Joshep Antonie Manöel de Végobre, born on November 12, 1752, in Geneva, Switzerland, and died sometime in 1840, was a professor, lawyer, magistrate, and writer. (Although he excelled in other activities throughout his life.)

He was the son of Charles Manoël de Végobre and Louise de Vignolles-de-La-Valette. (I don't know why I find it funny that parents have named their children after other genders. Charles = Charlotte; Louise = Louis)

The surname "De Végobre" was invented by C. De Végobre; his original surname is Manoël. A possible reason: to hide his identity. Louis De Végobre's father was embroiled in several controversies, so much so that his entire family was banned from practicing as state lawyers. (But don't worry because Louis ended up being a judge).

He was the second of six children, but his eldest brother died when Louis de Végobre was about 4 years old. (His mother became pregnant 15 times, but only 6 of them were successful.) Like John Laurens, not all of his siblings survived. Only Anne-Charlotte (September 4, 1754–1840) and Phillipe (June 24, 1762–May 2, 1778). (Phillipe died tragically at the age of 16.)

When Louis was 11, his parents left Geneva with Phillipe, leaving him in the care of his sister Charlotte, who was 9 years old.

I could write another post about that, but in general terms: Charles de Végobre was a very active and provocative Protestant. That's why the King of France wanted to kill him. Charles became close friends with Voltaire and, along with other men, became direct rivals of Catholic France.

Charles de Végobre fled because he was wanted (they even called him "the destroyer of worlds") . The reason he didn't take Louis was because he had a chronic respiratory illness (asthma or something similar). This is briefly mentioned in a letter to Voltaire. He didn't take Charlotte so her brother wouldn't be alone - a really bad idea. 9- and 11-year-olds alone, what could happen?

In 1763, De Végobre began working in a library to pay off his father's debts. Some time later (I don't know exactly when, no one specifies) he ends up being arrested in order to make him confess where his father was.

Apparently it was all for nothing, because he spent part of his adolescence on parole and doing forced labor. (until approx 14 years old).

Four or five families paid for his freedom, of which we must remember three names: Chais, Chauvet and Naville.

Jean Antonie Chais: He was John's first tutor when he arrived in Geneva. He taught classics, philosophy, and Latin. You're probably familiar with him. Both, John and Louis, got angry with him over some issue (more on that in another post). My God, I must make so many posts...

David Chauvet: John's second tutor in Geneva. He was a close friend of Henry. He was supposed to be his first tutor, but the residence was full. He recommended De Végobre as John's mathematics tutor.

André Naville: André Naville: He was the father of François Andrés Naville, a schoolmate of Louis. Basically, it was a wealthy family of lawyers and merchants. André Naville ended up "hiring" Louis for some unknown job (I assume a secretary?). By this point, François and Louis had become best friends (Maybe more than frinds at this point?) I don't know what to think. François was a jealous frind. (Said by acquaintances).

At some point in their lives, Louis and François began studying law at the Geneva Academy (now the University of Geneva). Louis wanted to study mathematics and natural philosophy (physics), but he couldn't afford it. There were scholarships in Geneva, but the king forbade the De Végobre family from having one. (Geneva was not independent at that time.) Even a minister of the king went so far as to say that his family would never be considered even bourgeois.

There the group of friends that John Laurens would later join was formed: Marc Auguste Pictet, Albert Turrettini, Pierre Prevost, (?) Martin and François Naville. Later: Kinloch, Müller, Bonstteten and Manigault.

At another, unknown point in his life, Louis began tutoring young boys (including Laurens - 1772) in mathematics. Prevost was studying physics, and with Pictet and De Végobre, they often spent their free time researching physics.

As for his romantic relationships, he never married. Nor did he seem interested in any woman (and Voltaire tried to marry him off to a girl). In my opinion (I'm open to other opinions), Louis only had a serious relationship with Naville. Perhaps I could argue for a brief relationship with Laurens.

Naville-De Végobre:

According to what friends of both casually say, the two were inseparable: Naville wrote poems for him (Pictet once said) no poem found. De Végobre mentions in the epilogue of a book that Naville would have fits of rage and burn all his work and correspondence. Louis tried to save the papers.

François and Louis often argued because François was a Protestant, active, and very provocative (like Charles de Végobre). François also loved getting involved in politics.

At first, neither of them wanted to get married. In the end, François's father married him at the age of 31 to Anne Renée Gallatin (21 years old). The marriage did not go too well, but they had four children (3 boys and a girl).

Before François was murdered, Anne used to argue with François because he spent more time with Louis (information from the draft of the introductory speech to Naville's posthumous work). Even Anne asked Louis not to publish the first version he had written of this work (Discours pour servir d'introduction à un ouvrage posthume de François-André Naville, ci-devant conseiller d'état de la république de Genève) because it was "too personal" and could "tarnish" the family name. He makes a brief reference to this conflict, which is so widely discussed among his acquaintances, on the first page.

Mr. Naville's family felt it was more appropriate to postpone the publication of this work at the very least; I initially believed the reason for this decision would be the Preliminary Discourse. This was also the advice he gave me, which provoked a well-founded timidity.

However, after hesitating for a long time, I follow the advice of my friends. Their opinions are of great importance to me: I surrender to the sense of duty that long prompted me to pay this funeral tribute to the memory of my friend and to that of the virtuous Magistrates who perished with him.

[...]

If I present this Discourse as it was originally composed, without deleting the first two parts, which deal only with my friend, it is because these two parts are not unrelated to his praise, which is my main objective.

A brief reading of that work reveals part of their relationship (although it's quite censored, thanks Anne for screwing up the evidence). I can also understand Anne's point.

It is not, however, before the public that I wish to shed these tears with which I water the grave the ashes of my friends [...]

It is not to the ears of a frivolous public that I wish to make my laments heard for the crimes that have stained and for the catastrophe that has erased from the ranks of nations such a beloved homeland. But it is to the friends of the victims that I mourn, to the Genevans whose hearts respond to mine, to whom I present as a gift this faint expression of the feelings I experience and which it is sweet to find among them.

Throughout the book he tells some anecdotes, this is only part of the first page.

Someone argued with me on Wattpad that Louis was engaged because he's wearing a ring in his Minister portrait. I have several arguments about this:

Maybe that ring is a signet ring. Very common among officials and men of high status (for exenple Henry Laurens). This idea is the most appropriate

Many men wore a ring to avoid questions about their single status. However, De Végobre didn't care about the opinions of others, so this option is unlikely. I mean, just look at the way he expresses himself in his travel guide. He knew it was going to be published, and yet he still wrote ironic things—imagine in his private life.

Maybe something personal. (It could be Naville's ring; he was murdered, and De Végobre kept some of his belongings.) I mean, Naville entrusted him with the education of his children in his will, I don't see the ring as so crazy.

Another option is that he wears a ring without reason, but he is a simple man and he didn't like those things.

This painting is in the library of the University of Geneva. If you go there, they'll show it to you without any problem! (They finally took the opportunity to upload it online in better quality.)

The only time Naville and de Végobre distanced themselves after an argument was, coincidentally, in 1772 and later. Who was in Geneva at that time? That's right: John Laurens.

Those of you who know em from Wattpad already know that I'm not a believer in the Kinloch-De Végobre relationship (with or without Manigault). For me, it didn't existeix, no in same way that her relationship with Laurens or Naville did. I compareu a lot of correspondence between these men. Even I think Kinloch sometimes felt jealous of the De Vegobre-Laurens relationship. Jealous, or perhaps displaced. I believe, evidently, that the Laurens-Kinloch relationship existed.

You've all read De Végobre's letters to Laurens, in fact, there's one not available online from 1781. De Végobre isn't so affectionate with everyone, he's friendly and kind, but there's a big difference.What part should we highlight from their correspondence? «Mon cher, Laurens»,

You have began to make me feeling how hard it is to fee the departure of a man to whoms one's heart ir addicted, others will do the same with me; all is not happines. Engish Friends. I will, i will see you in your country, before i die! [...]

Adieu, I don't know if I in this language I have been able to explain my hart's true sentiments; you shall see in thos letter my knowledge in your tongue; you will laugh at my mistakes in the Grammar, but not at my sentiments. Adieu

De végobre to Laurens, 24 dec. 1774

I want to write another post analyzing letters! This one is supposed to be only about De Végobre!

There is also another interesting figure in his life: Samuel Vincent, a student of his whose theology studies De Végobre helped pay for around 1800. He also deserves a separate post.

Sir, here is another sign of life. It is true that you may sometimes doubt whether I am alive, but you must never doubt whether I love you. You will find my friendship too calm, no doubt, and not very active; alas! It is in keeping with the rest of my character. It is no less sincere and lively for that. Thus, she eagerly seized upon the hope you gave me in a corner of your letter to let you flow toward Languedoc. Since it is the slope that guides you, remember that once you reach Nîmes, you must remain there still and not climb to the heights. The Cévennes should no longer be the sole destination of your travels to Languedoc. I stand in your way, ready to seize you by the throat. When I have detained you long enough in Nîmes and you wish to leave in spite of me, I will quickly go and ambush you at Gajan and catch you when you least expect it. If you escape from me again, who knows? Depending on the weather, I might chase you all the way to the Cévennes or force you back down. May I soon enjoy this happiness, and may I join in the memory. [...]

If you want to know anything about my family, I'll tell you that we're all fine, that we all love you, that we all wish you the same love I've shown you. Yours completely devoted: Pastor S Vincent

Samuel Vincent to Louis De Végobre 8 of March 1810.

I must admit that in the last sentence he makes a slightly strange use of French words, but I didn't pay attention to it. I know there are people who think they were more than friends. I haven't found any evidence to support this claim.

Also in another letter he wrote these verses by Voltaire:

De tous mes sentiments tel est le caractère, Je veux avec excès vous aimer et vous plaire.

Context:

While one of your letters should answer half a dozen of mine, here's one of mine that answers two of yours. And to give Voltaire's verses their true meaning:

Of all my feelings such is the character,

I want to love you and please you excessively.

But laziness destroys in me what is good in the will. As long as you don't doubt my feelings, I will do justice to the reproaches you make me. I recently decided to no longer make excuses for my carelessness in writing. When one writes as little as I do, one shouldn't spend half of that little time making useless excuses, always the same ones.

[...]

All my relatives, all your friends, shower you with their compliments and their blessings. And I join them in wishing you joy and health. This could be most agreeable to your friend and devoted disciple

Vincent to De Vegobre, 6 May 1810

They often shared topics and opinions about the Church in their letters. De Végobre even offered Vincent a teaching job, but he turned it down because he considered himself too young to accept it.

Personally, I don't see them as a couple, but I'm glad to know that De Végobre had friendships after Naville's death!

After Naville's death in 1794, he became depressed. He even said he would have liked to die beside him. He later wrote that it would have been better for him to die instead of Naville (because François was a father and husband).

To avoid getting too involved in political matters, I'll give you some brief background. Naville was often the spokesperson for any political opinion opposed to the monarchy or established regimes. De Végobre was much more quiet, preferring to avoid the topics that had caused so much damage to his family.

Louis had to leave to Vaud in 1781, seeking refuge in the home of Albert Turrettini (where he served as tutor to Turrettini's son), again due to matters involving his father. He had to flee in an emergency, he left without packing anything. His parents died around 1794, but that wasn't the end of it.

When 1793-1794 (Le Terreur) arrived, he was again imprisoned (this time with Naville). His house in Pâquis was burned, and he lost the entire fortune he had managed to amass over the past few years. Several trials followed. First, Louis's, where he was acquitted and granted parole. Immediately after, Naville's, where he was sentenced to death and shot in front of de Végobre. This was too shocking for him, and it kept him distant for the rest of his life (said Pictet).

For the rest of his life, for 45 years, he limited himself to studying and working. No further mention has been made of any friendships or close interactions outside of work. His only correspondence was with Vincent during 1810.

Finally, some professional information about him is that he was so good at physics that he was Pictet's substitute professor at the University of Geneva, helping scientists and mathematicians with their work. (He was literally a human calculator.) As for his legal career, he was a magistrate and judge. He and his sister founded an association to provide legal aid to orphaned minors and prostitutes. (His sister was the founder of the orphanage, and he had been teaching the children there since before 1780.)

He also published several works explaining how to structure the legal system of the independent Republic of Geneva and other places (specifically Vaud).

I'll write a second part! Feel free to write me any questions or concerns. I'll be happy to answer! Thanks for welcoming me so warmly to Tumblr!

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

A.5 What are some examples of “Anarchy in Action”?

A.5.1 The Paris Commune

The Paris Commune of 1871 played an important role in the development of both anarchist ideas and the movement. As Bakunin commented at the time,

“revolutionary socialism [i.e. anarchism] has just attempted its first striking and practical demonstration in the Paris Commune … [It] show[ed] to all enslaved peoples (and are there any masses that are not slaves?) the only road to emancipation and health; Paris inflict[ed] a mortal blow upon the political traditions of bourgeois radicalism and [gave] a real basis to revolutionary socialism.” [Bakunin on Anarchism, pp. 263–4]

The Paris Commune was created after France was defeated by Prussia in the Franco-Prussian war. The French government tried to send in troops to regain the Parisian National Guard’s cannon to prevent it from falling into the hands of the population. “Learning that the Versailles soldiers were trying to seize the cannon,” recounted participant Louise Michel, “men and women of Montmartre swarmed up the Butte in surprise manoeuvre. Those people who were climbing up the Butte believed they would die, but they were prepared to pay the price.” The soldiers refused to fire on the jeering crowd and turned their weapons on their officers. This was March 18th; the Commune had begun and “the people wakened … The eighteenth of March could have belonged to the allies of kings, or to foreigners, or to the people. It was the people’s.” [Red Virgin: Memoirs of Louise Michel, p. 64]

In the free elections called by the Parisian National Guard, the citizens of Paris elected a council made up of a majority of Jacobins and Republicans and a minority of socialists (mostly Blanquists — authoritarian socialists — and followers of the anarchist Proudhon). This council proclaimed Paris autonomous and desired to recreate France as a confederation of communes (i.e. communities). Within the Commune, the elected council people were recallable and paid an average wage. In addition, they had to report back to the people who had elected them and were subject to recall by electors if they did not carry out their mandates.

Why this development caught the imagination of anarchists is clear — it has strong similarities with anarchist ideas. In fact, the example of the Paris Commune was in many ways similar to how Bakunin had predicted that a revolution would have to occur — a major city declaring itself autonomous, organising itself, leading by example, and urging the rest of the planet to follow it. (See “Letter to Albert Richards” in Bakunin on Anarchism). The Paris Commune began the process of creating a new society, one organised from the bottom up. It was “a blow for the decentralisation of political power.” [Voltairine de Cleyre, “The Paris Commune,” Anarchy! An Anthology of Emma Goldman’s Mother Earth, p. 67]

Many anarchists played a role within the Commune — for example Louise Michel, the Reclus brothers, and Eugene Varlin (the latter murdered in the repression afterwards). As for the reforms initiated by the Commune, such as the re-opening of workplaces as co-operatives, anarchists can see their ideas of associated labour beginning to be realised. By May, 43 workplaces were co-operatively run and the Louvre Museum was a munitions factory run by a workers’ council. Echoing Proudhon, a meeting of the Mechanics Union and the Association of Metal Workers argued that “our economic emancipation … can only be obtained through the formation of workers’ associations, which alone can transform our position from that of wage earners to that of associates.” They instructed their delegates to the Commune’s Commission on Labour Organisation to support the following objectives:

“The abolition of the exploitation of man by man, the last vestige of slavery; “The organisation of labour in mutual associations and inalienable capital.”

In this way, they hoped to ensure that “equality must not be an empty word” in the Commune. [The Paris Commune of 1871: The View from the Left, Eugene Schulkind (ed.), p. 164] The Engineers Union voted at a meeting on 23rd of April that since the aim of the Commune should be “economic emancipation” it should “organise labour through associations in which there would be joint responsibility” in order “to suppress the exploitation of man by man.” [quoted by Stewart Edwards, The Paris Commune 1871, pp. 263–4]

As well as self-managed workers’ associations, the Communards practised direct democracy in a network popular clubs, popular organisations similar to the directly democratic neighbourhood assemblies (“sections”) of the French Revolution. “People, govern yourselves through your public meetings, through your press” proclaimed the newspaper of one Club. The commune was seen as an expression of the assembled people, for (to quote another Club) “Communal power resides in each arrondissement [neighbourhood] wherever men are assembled who have a horror of the yoke and of servitude.” Little wonder that Gustave Courbet, artist friend and follower of Proudhon, proclaimed Paris as “a true paradise … all social groups have established themselves as federations and are masters of their own fate.” [quoted by Martin Phillip Johnson, The Paradise of Association, p. 5 and p. 6]

In addition the Commune’s “Declaration to the French People” which echoed many key anarchist ideas. It saw the “political unity” of society as being based on “the voluntary association of all local initiatives, the free and spontaneous concourse of all individual energies for the common aim, the well-being, the liberty and the security of all.” [quoted by Edwards, Op. Cit., p. 218] The new society envisioned by the communards was one based on the “absolute autonomy of the Commune … assuring to each its integral rights and to each Frenchman the full exercise of his aptitudes, as a man, a citizen and a labourer. The autonomy of the Commune will have for its limits only the equal autonomy of all other communes adhering to the contract; their association must ensure the liberty of France.” [“Declaration to the French People”, quoted by George Woodcock, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon: A Biography, pp. 276–7] With its vision of a confederation of communes, Bakunin was correct to assert that the Paris Commune was “a bold, clearly formulated negation of the State.” [Bakunin on Anarchism, p. 264]

Moreover, the Commune’s ideas on federation obviously reflected the influence of Proudhon on French radical ideas. Indeed, the Commune’s vision of a communal France based on a federation of delegates bound by imperative mandates issued by their electors and subject to recall at any moment echoes Proudhon’s ideas (Proudhon had argued in favour of the “implementation of the binding mandate” in 1848 [No Gods, No Masters, p. 63] and for federation of communes in his work The Principle of Federation).

Thus both economically and politically the Paris Commune was heavily influenced by anarchist ideas. Economically, the theory of associated production expounded by Proudhon and Bakunin became consciously revolutionary practice. Politically, in the Commune’s call for federalism and autonomy, anarchists see their “future social organisation… [being] carried out from the bottom up, by the free association or federation of workers, starting with associations, then going into the communes, the regions, the nations, and, finally, culminating in a great international and universal federation.” [Bakunin, Op. Cit., p. 270]

However, for anarchists the Commune did not go far enough. It did not abolish the state within the Commune, as it had abolished it beyond it. The Communards organised themselves “in a Jacobin manner” (to use Bakunin’s cutting term). As Peter Kropotkin pointed out, while “proclaiming the free Commune, the people of Paris proclaimed an essential anarchist principle … they stopped mid-course” and gave “themselves a Communal Council copied from the old municipal councils.” Thus the Paris Commune did not “break with the tradition of the State, of representative government, and it did not attempt to achieve within the Commune that organisation from the simple to the complex it inaugurated by proclaiming the independence and free federation of the Communes.” This lead to disaster as the Commune council became “immobilised … by red tape” and lost “the sensitivity that comes from continued contact with the masses … Paralysed by their distancing from the revolutionary centre — the people — they themselves paralysed the popular initiative.” [Words of a Rebel, p. 97, p. 93 and p. 97]

In addition, its attempts at economic reform did not go far enough, making no attempt to turn all workplaces into co-operatives (i.e. to expropriate capital) and forming associations of these co-operatives to co-ordinate and support each other’s economic activities. Paris, stressed Voltairine de Cleyre, “failed to strike at economic tyranny, and so came of what it could have achieved” which was a “free community whose economic affairs shall be arranged by the groups of actual producers and distributors, eliminating the useless and harmful element now in possession of the world’s capital.” [Op. Cit., p. 67] As the city was under constant siege by the French army, it is understandable that the Communards had other things on their minds. However, for Kropotkin such a position was a disaster:

“They treated the economic question as a secondary one, which would be attended to later on, after the triumph of the Commune … But the crushing defeat which soon followed, and the blood-thirsty revenge taken by the middle class, proved once more that the triumph of a popular Commune was materially impossible without a parallel triumph of the people in the economic field.” [Op. Cit., p. 74]

Anarchists drew the obvious conclusions, arguing that “if no central government was needed to rule the independent Communes, if the national Government is thrown overboard and national unity is obtained by free federation, then a central municipal Government becomes equally useless and noxious. The same federative principle would do within the Commune.” [Kropotkin, Evolution and Environment, p. 75] Instead of abolishing the state within the commune by organising federations of directly democratic mass assemblies, like the Parisian “sections” of the revolution of 1789–93 (see Kropotkin’s Great French Revolution for more on these), the Paris Commune kept representative government and suffered for it. “Instead of acting for themselves … the people, confiding in their governors, entrusted them the charge of taking the initiative. This was the first consequence of the inevitable result of elections.” The council soon became “the greatest obstacle to the revolution” thus proving the “political axiom that a government cannot be revolutionary.” [Anarchism, p. 240, p. 241 and p. 249]

The council become more and more isolated from the people who elected it, and thus more and more irrelevant. And as its irrelevance grew, so did its authoritarian tendencies, with the Jacobin majority creating a “Committee of Public Safety” to “defend” (by terror) the “revolution.” The Committee was opposed by the libertarian socialist minority and was, fortunately, ignored in practice by the people of Paris as they defended their freedom against the French army, which was attacking them in the name of capitalist civilisation and “liberty.” On May 21st, government troops entered the city, followed by seven days of bitter street fighting. Squads of soldiers and armed members of the bourgeoisie roamed the streets, killing and maiming at will. Over 25,000 people were killed in the street fighting, many murdered after they had surrendered, and their bodies dumped in mass graves. As a final insult, Sacré Coeur was built by the bourgeoisie on the birth place of the Commune, the Butte of Montmartre, to atone for the radical and atheist revolt which had so terrified them.

For anarchists, the lessons of the Paris Commune were threefold. Firstly, a decentralised confederation of communities is the necessary political form of a free society (”This was the form that the social revolution must take — the independent commune.” [Kropotkin, Op. Cit., p. 163]). Secondly, “there is no more reason for a government inside a Commune than for government above the Commune.” This means that an anarchist community will be based on a confederation of neighbourhood and workplace assemblies freely co-operating together. Thirdly, it is critically important to unify political and economic revolutions into a social revolution. “They tried to consolidate the Commune first and put off the social revolution until later, whereas the only way to proceed was to consolidate the Commune by means of the social revolution!” [Peter Kropotkin, Words of a Rebel , p. 97]

For more anarchist perspectives on the Paris Commune see Kropotkin’s essay “The Paris Commune” in Words of a Rebel (and The Anarchist Reader) and Bakunin’s “The Paris Commune and the Idea of the State” in Bakunin on Anarchism.

#community building#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

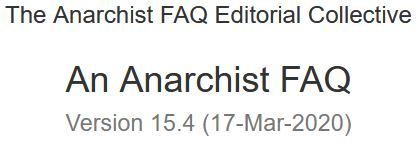

3. Artist Research: Annie Leibovitz (Week 1)

The photo’s that Annie Leibovitz takes are captivating pieces of work that seem to catch the true spirit of the subject. Her work has an energy to them that engage the viewer, and creates that connection between the subject and those looking at the piece.

In the image of Mikhail Barishnikov, he’s held in this position that feels like he’s caught in the midst of moving. Muscles are tense, and the pose is dynamic. I like that the composition shows a little of the space outside of the backdrop, and that some context of the project’s location is revealed. The frame also includes the entirety of Barishnikov’s body. The figure is brightly lit, most likely with studio lighting. The light source is coming from the left at an angle above, as shadows are seen on the bottom and at the right of the figure.

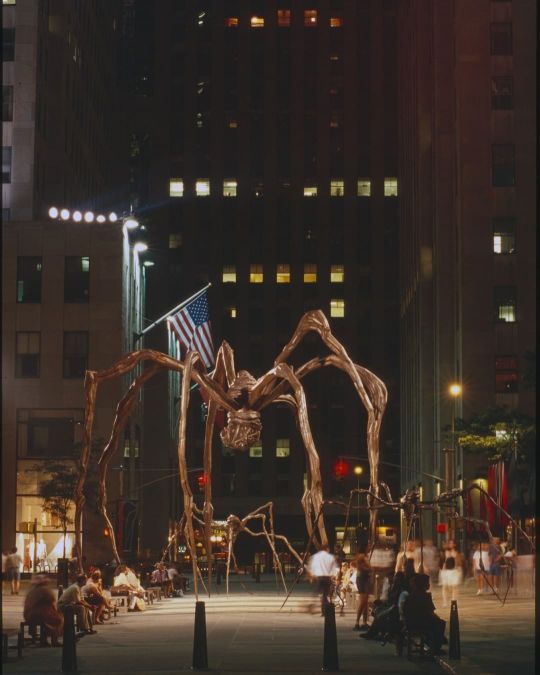

Overall, this portrait of Louise Bourgeois is quite the dramatic composition. The hand being held up, the lighting coming from the side, and Bourgeois at a 90 degree angle. The texture of the face is beautifully brought to attention by the hard lighting. By having the lighting coming in on an angle, the signs of age (such as wrinkles and rivets) that are on the face have cast shadows, creating some intricate lines and patterns that would’ve been flattened out by a ‘head-on’ light. She appears close to the wall, with her shadow being cast on the surface behind.

This is a much less conventional version of a portrait as it doesn’t appear to be in the traditional studio. Instead, the figure of Whoopi Goldberg is lying in a bath filled with an opaque white liquid, covering her seemingly naked body. Her tongue is out in a mischievous and playful manner, most likely a reference to her career as an actor and comedian. The lighting is indirect and soft and is seemingly natural (perhaps coming through the window of the bathroom in which the bath sits?). For me, the combination of lighting, coloration and subject matter create a sense of childlike wonder.

“I no longer believe that there is such a thing as objectivity. Everyone has a point of view. Some people call it style, but what we’re really talking about is the guts of a photograph. When you trust your point of view, that’s when you start taking pictures.”

(Annie Leibovitz… from a conversation with Ingrid Sischy. Source: „Annie Leibovitz Photographs 1970 – 1990” Harper Perennial (A Division of HarperCollins Publishers) NewYork 1992; ISBN 0-06-092346-6(pbk.); Library of Congress Library Card Number 90-56384, p. 9)

0 notes

Text

Évasion : une exposition multifacette

https://justifiable.fr/?p=1623 https://justifiable.fr/?p=1623 #Évasion #Exposition #multifacette #une La dernière exposition de l’année 2024, qui se tiendra jusqu’au 21 décembre à l’espace d’art Chaillioux de la ville de Fresnes, située dans le Val-de-Marne (94), invite les Franciliens à explorer les multiples dimensions de l’évasion. Le terme évoque à la fois l’acte de s’échapper physiquement d’un lieu contraignant, de fuir une réalité oppressante, ou de se libérer par la pensée, le rêve, ou l’imagination. Stéphane Dauthuille – Maison perchée rose et nuages L’exposition, organisée par l’espace d’art Chaillioux, réunit des artistes dont les œuvres incarnent diverses formes d’évasion, offrant une expérience immersive et réfléchie. Stéphane Dauthuille propose une exploration de l’évasion par le rêve et la délivrance de la pesanteur. Ses compositions poétiques et énigmatiques invitent le spectateur à interpréter librement, créant ainsi une navigation mentale à travers des archipels oniriques. Inspiré par le surréalisme d’André Breton, Stéphane Dauthuille incite à un vagabondage poétique où la frontière entre le réel et l’imaginaire s’efface. Artiste-designer diplômé de l’École Boulle, Dorian Étienne fusionne art et artisanat dans une démarche écoresponsable. Son projet « Pays’Âges » présente des tapisseries monumentales, réalisées avec des matériaux locaux, qui témoignent des changements climatiques et écologiques d’une région. En impliquant les habitants dans le processus créatif, Dorian Étienne transforme l’art en un outil participatif de sensibilisation et de valorisation environnementale. Restaurateur de peintures et artiste pluridisciplinaire, Valerio Fasciani aborde les thèmes de la liberté et des contraintes sociales. Son œuvre « Icare – L’Annonciation » illustre le parcours d’un jeune immigré clandestin, symbolisant une renaissance et l’espoir d’un avenir meilleur. Ses installations en forme de cages interrogent les limites imposées par la société et par l’individu lui-même, offrant une réflexion profonde sur la liberté personnelle. Les créations de Charlotte Puertas, peuplées de fantômes et de souvenirs, explorent l’introspection et l’exorcisme des visions passées et présentes. Artiste polymorphe, elle utilise des superpositions et des métamorphoses d’images pour offrir des œuvres autobiographiques et universelles. Son travail, à la fois intime et introspectif, entraîne le spectateur dans un tourbillon émotionnel, révélant une quête de sens et de partage. Le collectif Rés(O)nances, composé de Marie Kopecká Verhoeven et Dominique Defontaines, propose une installation émouvante évoquant le camp de concentration de Terezín. « Les Fleurs de Terezín » utilisent des chaînes rouillées pour symboliser la résistance et la résilience face à l’oppression. Cette œuvre, accompagnée de photographies historiques, rappelle la persistance de l’espoir et de la liberté intérieure. Élisabeth Straubhaar se consacre au dessin pour créer des univers où microcosme et macrocosme se confondent. Ses œuvres fantastiques, inspirées des illustrations de contes, brouillent les frontières entre les structures humaines, animales, végétales et minérales. Élisabeth Straubhaar invite le spectateur à une découverte introspective, où rêves et réalités se mélangent, offrant une évasion vers des terres inconnues. Cette exposition riche et variée, qui se déroule jusqu’au 21 décembre 2024, promet d’offrir aux visiteurs une expérience immersive, explorant les multiples facettes de l’évasion. Chaque artiste, à travers son approche unique, incite à la réflexion sur la liberté, la mémoire, et l’imagination, faisant de cette exposition un voyage sensoriel et intellectuel inoubliable. Infos Espace d’art Chaillioux 7 rue Louise Bourgeois 94260 Fresnes Jusqu’au 21 décembre 2024 https://www.actu-juridique.fr/culture/evasion-une-exposition-multifacette/

0 notes

Text

Lecture Notes MON 26th FEB

Masterlist

BUY ME A COFFEE

A centre and its Peripheries 1830-1900

Further Reading: Manet's Olympia Reviews, Fournel (1829 - 1894) 'The Art of Flanerie', Baudelaire: The Painter of Modern Life, Gaugin (1848 - 1903) from three letters written before leaving for Polynesia

More and Other Reading

Context

The centre: Paris has been called the cultural capital of the nineteenth century. Modernism began in France and spread.

Salon was rebranded after the revolution and continued exhibiting, but was organised by the state rather than the king and upper classes.

Review of the Salon of 1846 by Baudelaire:

“the life of our city is rich in poetic and marvellous subjects. We are enveloped and steeped as though in an atmosphere of the marvellous; but we do not notice it”.

Walter Benjamin: Paris was the capital of the 19th century. The socio politically landscape was changing constantly in Paris, revolution and coup-d’etat in 1848 and 1851. Subsequent proclamation of an empire

1860s: artistic avant-garde opposed to the conventions of the Academy, it’s also the academies that establish and support modern art development.

Network of dealers and galleries; periodical literature; evolving and effervescent political and cultural ideas.

Juste Milieu painting

From the July Monarchy, focused on Classicism, not necessarily a style but a tendency. Albert Boime characterises juste milieu art which thrived under the monarchy of Louis-Philippe (1830-1848) as a middle way between Classicism and Romanticism, combining romantic themes with classical forms and technique.

Boime writes: ’Dissatisfied with the Classic-Academic style, and perplexed by the Romantic style, the public of the July monarchy supported the compromise art of the juste milieu.’ – Boime, The Academy and French Painting, p. 10

For Boime it was juste milieu painting that was the official art of the period. A middle brow art, sentimental and uncontentious. A well measured middle ground.

Artists that categorised this period: Paul Delaroche, Albert Boime, Ary Scheffer

Paul Delaroche, Execution of Lady Jane Grey, 1822, National Gallery, London

In a similar fashion, Bastien-Lepage and others offered a middle-way version of Impression that had popular appeal. Since the 1970s art historians have paid much more attention to works like these that were previously overlooked and dismissed.

There is a display of competent charming in form from the traditional classical style, and a draw on romantic things in these paintings.

Jules Bastien-Lepage, L'Amour au Village, 1883, 199 x 181 cms Oil on canvas

In the 1830 revolution, that led to Louise Philippe, there was a bourgeois regime, creating a middle class.

Gustave Courbet

Courbet came from peasant origins, the meaning of peasant at that time was someone who lived off the land. His family imagined a bourgeois life for him. And while the aforementioned Juste Milieu paintings were non-confrontational and common to be painted, after the failed Napoleonic III revolution, he began to paint more political art. In the form of Realism with Bohemian language, the realism approach was seen as radical, especially when paired with the political stances. But the Bohemian balanced it, as it was talking to Parisians and in a visual language people were used to.

However, modernisation impacted the lower classes too, especially the farmers/peasants, making it harder for them to make money, with many loosing their land, falling into debt because of it and having to move to Paris.

Courbet raised serious social issues when he exhibited his work in the Salon’s, receiving a medal for his work.

A Burial at Ornans, 1849 - 1850. Musee D’Orsay.

Photograph of The Stonebreakers (original destroyed), 1849

‘I am not only a socialist but a Democrat and a Republican as well – in a word, a partisan of the revolution and above all a realist.’

Asked why he didn’t paint angels, Coubet replied he would paint one the day he saw it.

The Dresden bombing during the second world war destroyed the stonebreakers painting, being destroyed during the move as the Germans attempted to relocate it with other wealth and luxury goods.

The medal he received meant that he no longer had to submit his work for approval, and he could just send it to be put straight up. Although after the 1948 revolution, the Salons stopped wanting him and fought with him because of his politics.

This also happened to a great many other artists, leading to the creation of Salon des Refusés, 1863

In the middle of the nineteenth century, the official Salon continued to uphold Academic criteria and rejected the majority of works submitted, excluding artists who pursued any other approach. In 1863, responding to criticisms of the Salon, Emperor Napoleon III stated: ’His Majesty, wishing to let the public judge the legitimacy of these complaints, has decided that the works of art which were refused should be displayed in another part of the Palace of Industry’.

The novelist and critic Emile Zola observed that many who visited went to sneer and laugh.

In 1883 the Impressionists organized a second Salon des Refusés. By 1884 the Société des Artistes Indépendants had been founded, to hold un-juried exhibitions, which would accept the work of any artist who wished to participate.

Palais de l’Industrie in Paris where Salon des Refusés took place. Photo by Édouard Baldus.

This highlighted an open wish for artists to break away from the Academies.

Rejected by the Salon in 1863, Manet exhibited in the Salon des Refusés:

Édouard Manet, Le Dejeneur sur l’herbe (Luncheon on the Grass) 1863, via Musée d’Orsay, Paris

While this painting may raise questions as to why it was refused, some quick analysis will highlight its confrontational nature.

Most of it coming from the eye contact of the woman, staring at the viewer and challenging them in her bareness.

While this work does draw on classical paintings of naked women, one such example being: Giorgione, Pastoral Concert, c.1509

Manets work isn’t of gods or goddesses, unlike the classical work, its very human and raw. Perhaps even a little bit suggestive, and it’s precisely the subject matter that meant that the Academies rejected it.

The first exhibition of the Impressionist group was held at the studio of the photographer Nadar in 1874. Eight exhibitions followed, with the last in 1886. About 175 works by 30 artists were on show in the first exhibition. Including works by Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot, Pierre August Renoir, Camille, Pissarro, Paul Cézanne, Alfred Sisley. There was c.4,000 visitors in the month it was open.

The exhibition itself was held in a photography shop as in the 1880’s photography starts becoming more accessible.

Around the mid 1800’s Paris is greatly renovated and modernising. Paris becomes a construction site. Before this construction Paris used to look very Medieval with close streets and tight crowded houses.

Charles Marville photographer of the transformation

Pissarro, Avenue of the Opera, 1898

70,000 houses destroyed and 150,000 built. There was a crisis in capitalism at that time, however the renovation helped with that as it was a way to solve too many workers and not enough jobs. This created a leisure commodity, with great new offers of entertainment to be bought like cafes, music halls etc.

One such thing that took off was train stations, thanks to the industrial revolution.

Claude Monet, The Gare Saint-Lazare (or Interior View of the Gare Saint-Lazare, the Auteuil Line), 1877, oil on canvas, 75 x 104 cm (Musée d’Orsay)

Pierre-Auguste-Renoir, The Ball of the Moulin de la Galette,1876, Musée d’Orsay, Paris

The critic Meyer Schapiro described Impressionism as an art of spontaneous middle-class sociability.

The Edges of Paris

Manet, View of the 1867 Exposition Universelle, 1867

Gustave Caillebotte, Factories at Argenteuil, 1888, Private Collection

(Left) Georges Seurat, Bathers at Asnières , 1884, National Gallery, London (Right) Georges Seurat, A Sunday on La Grande Jatte, 1884, Chicago Art Institute

Away from Paris

Paul Gaugin travelled to Polynesia to discover the “wild” and “otherness”, the idea of the “other” meant pure, exotic, and to be studied. Which is a complete pseudo-science. This also was an idea that persisted around the time, as early as 1877 there were organised ethological spectacles. Basically, people of colour were put on display to be gawked at. Modernity does not mean there is an otherness to people who are not modern. Here are some works and examples:

"under an eternally summer sky, on a marvelously fertile soil…the…happy inhabitants of the unknown paradise of Oceania know only the sweetness of life” —Paul Gauguin, letter from 1890

Paul Gauguin, Women of Tahiti, 1891

Gauguin in Tahiti 1891-1893. He returned to Paris and again travelled to Tahiti in 1895.

The ‘Primitive’

He spent the first three months in Papeete the capital of the colony and already much influenced by French and European culture. He decided to set up his studio in Mataiea, Papeari some 28 milesfrom Papeete, installing himself in a native-style bamboo hut. Gauguin was in constant conflict with French Missionaries. But he was hardly isolated. He was met disembarking by the French Consul and was in regular contact with Paris. Showing his work and receiving the art magazines.

Paul Gauguin, Nevermore , 1897, Oil paint on canvas, The Courtauld, London

Teha'amana Gauguin’s thirteen year old ‘vahine’ or native wife. She was pregnant by him at the end of 1892

In 1901 Gauguin left Tahiti for the Marquises Islands. He died in 1903 (probably of Syphillis)

(Left) Poster advertising the Somali exhibit in the Bois du Boulogne, “Jardin zoologique d’Acclimatation. Somalis” 1890. (Right) Poster advertising the Ashantis of modern-day Ghana, “Jardin zoologique d’Acclimatation. Achantis” 1887.

#art#art gallery#artwork#writing#art tag#essay#paintings#art exhibition#art show#artists#essay writing#art history#writers#history#writeblr#writers and poets#writers on tumblr#drawings#creative writing#life lessons#history lesson#lecture#learn#drawing#painting#colonial violence#colonialism#colonization#historical#academic writing

0 notes

Text

'I need to make things. The physical interaction with the medium has a curative effect. I need the physical acting out. I need to have these objects exist in relation to my body.' Louise Bourgeois (quoted in Kellein 2006, p.16.)

Research Study the artist's life and style for inspiration.

Louise Bourgeois: The Spider the Mistress and the Tangerine (full film available on youtube)

Louise Bourgeois – Art to Read Series (book link – I had bought this one at Mass MoCA a while back)

Articles:

A Dangerous Method – Artforum

Spiraling into Louise Bourgeois's Inner Realm - Galerie

Texts - Louise Bourgeois: the return of the repressed - Exhibiciones | Fundación PROA

Louise Bourgeois, recognizing the self the artist's way, with Jason Smith | Art World Women

Bio from Tate

Louise Joséphine Bourgeois (1911 – 2010) was a French-American artist. Although she is best known for her large-scale sculpture and installation art, Bourgeois was also a prolific painter and printmaker. She explored a variety of themes over the course of her long career including domesticity and the family, sexuality and the body, as well as death and the unconscious. These themes connect to events from her childhood which she considered to be a therapeutic process. Although Bourgeois exhibited with the Abstract Expressionists and her work has much in common with Surrealism and Feminist art, she was not formally affiliated with a particular artistic movement.

Concept & Mood Board Create a simple concept for your installation & make a mood board for visual inspiration

Concept Ideas:

Project different Louise Bourgeois works on to a miniature scene set up on the desk in my small home office/studio space, using found objects from the space, and referencing some of the architectures of Bourgeois’ works and the aesthetic of her home/studio space

Emerging perhaps in part from my background in social work and past job providing counseling to young children living with parental illness, I want to work to understand and explore Bourgeois’ reflection of trauma and repressed childhood memories in her work

Group series of works thematically and juxtapose different forms

Mood Board Pinterest Including LB Visual references: Link

Mapping & Content: Choose 2D or 3D mapping and create content related to your choice.

2D mapping, with some additional exploration of using the projector as a light source to illuminate existing objects/structures

Content: paintings/drawings/sculptures from Louise Bourgeois’ body of work, as well as small sculptural elements that reference her work (wire recreation of her Maman spider sculpture, placement of clay carving tools to cast shadow mimicking Personages sculpture, books stacked to recall Memling Dawn, small stone fire pit hanging wire to create space for projection of suspended sculptures, small toy chairs from my own childhood lit red to recall her work with C-project / Cells / Red Room, small stone fire pit to represent Nature Study – Velvet Eyes)

Equipment List and briefly explain the equipment you'll use, including your projector choice.

Vamvo 12400 (far from the most high quality projector, but this is the one I have at home at the moment)

Step ladder for stabilizing projector

Macbook Pro with MadMapper

Desktop surface in my home office/studio to setup scene

Found materials from home office/studio to create scene:

Newspaper collage box

Glass-domed display case

Spider bent out of black wire

Mini dollhouse chairs

Stone mini firepit

Mini canvas

Antique wooden box sewing set

Black hanging wire

Red/gold encyclopedia stack

Tools for clay sculpting and wooden sculptural toy base

Paper bag

Sunset lamp for underdesk illumination

Reflection

Representing the work of an artist like Louise Bourgeois, even in such a small way, is a massive task, given the extent of her body of work and the longevity of her artistic life. I think any number of pieces that I settled on, even if I had been able to project 100 works, would have felt minuscule and never close to fully representative of all that Bourgeois created. Between watching the documentary, The Spider the Mistress and the Tangerine and collecting and projecting imagery, I do feel like I've spent more time with her work and have more context for the pieces of hers I've seen in person at Mass MoCA, Storm King, and Dia Beacon over the years.

Practically/technically, I had some challenges with the fragility of the environment once the projector was set up, having to reset or adjust masks if objects shifted, etc. That made tinkering with the setup on the desk feel hard, and I found myself stuck at one point, not thrilled with the initial balance but not wanting to move things around and re-mask. I eventually did make changes to the physical environment, and am glad I did - even having to go through and re-arrange elements in MadMapper. There was a lot of testing, doing and undoing, to understand what kind of surfaces do and do not work well for representing images/light.

Representing or curating another artist's work in a way where they cannot consent and be involved in the process, especially with an artist who was often so protective of where and how her work was shown, certainly impacted the choices I made creatively, wanting to be sensitive to the original work and its varied contexts. Having watched the documentary mentioned above relatively recently, I found myself recalling Bourgeois' voice throughout the process.

Documenting projection work is also tricky, but it was nice to have the piece up for a while at home so that I could try different angles and lighting situations, etc. Projector quality is also something I'm thinking more about now, potentially wanting to invest in a higher quality projector for use in contexts like this and beyond.

Working through this project, I started to feel my own aesthetics emerging in projection, and in crafting balance in a scene, editing what to include and what not to include when there is so much to reference and still being able to get a sense of the thematics of a work.

Lastly, completing this project while having COVID was certainly its own challenge, given my fluctuating energy levels and body/brain temperatures, but it was a good exercise in breaking creative work down into discrete tasks and production planning.

0 notes

Text

Garment from the performance, She Lost It (1992), Louise Bourgeois

6 notes

·

View notes

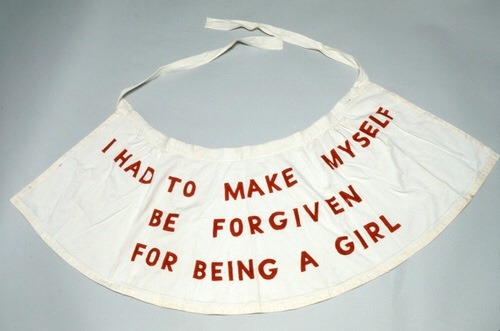

Photo

Self-Portrait, Louise Bourgeois

265 notes

·

View notes

Text

cloth panel from louise bourgeois’s 2009 piece eugénie grandet via all___kinds

1 note

·

View note

Photo

hands: for mothers day - nikki giovanni || fade into you - mazzy star || 10 am is when you come to me - louise bourgeois || the epic of gilgamesh - trans. danny p jackson || unfinished duet - richard siken

#yes it's always about hands#it's always hand in unlovable hand and he was pointing at the moon but i was looking at his hand and here is my hand that will not harm you#anyway#zukka#atla#avatar the last airbender#sokka#zuko#poetry#parallels#web weaving

659 notes

·

View notes

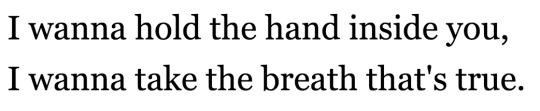

Photo

“Our society seems to be obsessed with youth and looking young, but there’s nothing more beautiful than ageing and becoming more of who you really are, getting to know the real essence within you. That is beautiful. It’s a beauty that shines through the eyes, through the wrinkles, the white hair, enduring pain, loss, heartbreak - becoming stronger, wiser, no longer caring about the validation of others, just flourishing more into you.” @villanaart with a powerful celebration of some of our favourite icons and the beauty of age and wisdom. Swipe to discover the amazing portraits of Louise Bourgeois, Yayoi Kusama, Vivienne Westwood, Iris Apfel, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Simone Veil. — #beautifulbizarre #villanaart #victoriavillasana #embroidery #photography #art #artist #contemporaryart #age #inspiration #mixedmedia #contemporarypainting #newcontemporary https://www.instagram.com/p/Co_I4wTIrcj/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#beautifulbizarre#villanaart#victoriavillasana#embroidery#photography#art#artist#contemporaryart#age#inspiration#mixedmedia#contemporarypainting#newcontemporary

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

A.3.5 What is Anarcha-Feminism?

Although opposition to the state and all forms of authority had a strong voice among the early feminists of the 19th century, the more recent feminist movement which began in the 1960’s was founded upon anarchist practice. This is where the term anarcha-feminism came from, referring to women anarchists who act within the larger feminist and anarchist movements to remind them of their principles.

The modern anarcha-feminists built upon the feminist ideas of previous anarchists, both male and female. Indeed, anarchism and feminism have always been closely linked. Many outstanding feminists have also been anarchists, including the pioneering Mary Wollstonecraft (author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman), the Communard Louise Michel, and the American anarchists (and tireless champions of women’s freedom) Voltairine de Cleyre and Emma Goldman (for the former, see her essays “Sex Slavery”, “Gates of Freedom”, “The Case of Woman vs. Orthodoxy”, “Those Who Marry Do Ill”; for the latter see “The Traffic in Women”, “Woman Suffrage”, “The Tragedy of Woman’s Emancipation”, “Marriage and Love” and “Victims of Morality”, for example). Freedom, the world’s oldest anarchist newspaper, was founded by Charlotte Wilson in 1886. Anarchist women like Virgilia D’Andrea and Rose Pesota played important roles in both the libertarian and labour movements. The “Mujeres Libres” (“Free Women”) movement in Spain during the Spanish revolution is a classic example of women anarchists organising themselves to defend their basic freedoms and create a society based on women’s freedom and equality (see Free Women of Spain by Martha Ackelsberg for more details on this important organisation). In addition, all the male major anarchist thinkers (bar Proudhon) were firm supporters of women’s equality. For example, Bakunin opposed patriarchy and how the law “subjects [women] to the absolute domination of the man.” He argued that ”[e]qual rights must belong to men and women” so that women can “become independent and be free to forge their own way of life.” He looked forward to the end of “the authoritarian juridical family” and “the full sexual freedom of women.” [Bakunin on Anarchism, p. 396 and p. 397]

Thus anarchism has since the 1860s combined a radical critique of capitalism and the state with an equally powerful critique of patriarchy (rule by men). Anarchists, particularly female ones, recognised that modern society was dominated by men. As Ana Maria Mozzoni (an Italian anarchist immigrant in Buenos Aires) put it, women “will find that the priest who damns you is a man; that the legislator who oppresses you is a man, that the husband who reduces you to an object is a man; that the libertine who harasses you is a man; that the capitalist who enriches himself with your ill-paid work and the speculator who calmly pockets the price of your body, are men.” Little has changed since then. Patriarchy still exists and, to quote the anarchist paper La Questione Sociale, it is still usually the case that women “are slaves both in social and private life. If you are a proletarian, you have two tyrants: the man and the boss. If bourgeois, the only sovereignty left to you is that of frivolity and coquetry.” [quoted by Jose Moya, Italians in Buenos Aires’s Anarchist Movement, pp. 197–8 and p. 200]

Anarchism, therefore, is based on an awareness that fighting patriarchy is as important as fighting against the state or capitalism. For ”[y]ou can have no free, or just, or equal society, nor anything approaching it, so long as womanhood is bought, sold, housed, clothed, fed, and protected, as a chattel.” [Voltairine de Cleyre, “The Gates of Freedom”, pp. 235–250, Eugenia C. Delamotte, Gates of Freedom, p. 242] To quote Louise Michel:

“The first thing that must change is the relationship between the sexes. Humanity has two parts, men and women, and we ought to be walking hand in hand; instead there is antagonism, and it will last as long as the ‘stronger’ half controls, or think its controls, the ‘weaker’ half.” [The Red Virgin: Memoirs of Louise Michel, p. 139]

Thus anarchism, like feminism, fights patriarchy and for women’s equality. Both share much common history and a concern about individual freedom, equality and dignity for members of the female sex (although, as we will explain in more depth below, anarchists have always been very critical of mainstream/liberal feminism as not going far enough). Therefore, it is unsurprising that the new wave of feminism of the sixties expressed itself in an anarchistic manner and drew much inspiration from anarchist figures such as Emma Goldman. Cathy Levine points out that, during this time, “independent groups of women began functioning without the structure, leaders, and other factotums of the male left, creating, independently and simultaneously, organisations similar to those of anarchists of many decades and regions. No accident, either.” [“The Tyranny of Tyranny,” Quiet Rumours: An Anarcha-Feminist Reader, p. 66] It is no accident because, as feminist scholars have noted, women were among the first victims of hierarchical society, which is thought to have begun with the rise of patriarchy and ideologies of domination during the late Neolithic era. Marilyn French argues (in Beyond Power) that the first major social stratification of the human race occurred when men began dominating women, with women becoming in effect a “lower” and “inferior” social class.

The links between anarchism and modern feminism exist in both ideas and action. Leading feminist thinker Carole Pateman notes that her “discussion [on contract theory and its authoritarian and patriarchal basis] owes something to” libertarian ideas, that is the “anarchist wing of the socialist movement.” [The Sexual Contract, p. 14] Moreover, she noted in the 1980s how the “major locus of criticism of authoritarian, hierarchical, undemocratic forms of organisation for the last twenty years has been the women’s movement … After Marx defeated Bakunin in the First International, the prevailing form of organisation in the labour movement, the nationalised industries and in the left sects has mimicked the hierarchy of the state … The women’s movement has rescued and put into practice the long-submerged idea [of anarchists like Bakunin] that movements for, and experiments in, social change must ‘prefigure’ the future form of social organisation.” [The Disorder of Women, p. 201]

Peggy Kornegger has drawn attention to these strong connections between feminism and anarchism, both in theory and practice. “The radical feminist perspective is almost pure anarchism,” she writes. “The basic theory postulates the nuclear family as the basis of all authoritarian systems. The lesson the child learns, from father to teacher to boss to god, is to obey the great anonymous voice of Authority. To graduate from childhood to adulthood is to become a full-fledged automaton, incapable of questioning or even of thinking clearly.” [“Anarchism: The Feminist Connection,” Quiet Rumours: An Anarcha-Feminist Reader, p. 26] Similarly, the Zero Collective argues that Anarcha-feminism “consists in recognising the anarchism of feminism and consciously developing it.” [“Anarchism/Feminism,” pp. 3–7, The Raven, no. 21, p. 6]

Anarcha-feminists point out that authoritarian traits and values, for example, domination, exploitation, aggressiveness, competitiveness, desensitisation etc., are highly valued in hierarchical civilisations and are traditionally referred to as “masculine.” In contrast, non-authoritarian traits and values such as co-operation, sharing, compassion, sensitivity, warmth, etc., are traditionally regarded as “feminine” and are devalued. Feminist scholars have traced this phenomenon back to the growth of patriarchal societies during the early Bronze Age and their conquest of co-operatively based “organic” societies in which “feminine” traits and values were prevalent and respected. Following these conquests, however, such values came to be regarded as “inferior,” especially for a man, since men were in charge of domination and exploitation under patriarchy. (See e.g. Riane Eisler, The Chalice and the Blade; Elise Boulding, The Underside of History). Hence anarcha-feminists have referred to the creation of a non-authoritarian, anarchist society based on co-operation, sharing, mutual aid, etc. as the “feminisation of society.”

Anarcha-feminists have noted that “feminising” society cannot be achieved without both self-management and decentralisation. This is because the patriarchal-authoritarian values and traditions they wish to overthrow are embodied and reproduced in hierarchies. Thus feminism implies decentralisation, which in turn implies self-management. Many feminists have recognised this, as reflected in their experiments with collective forms of feminist organisations that eliminate hierarchical structure and competitive forms of decision making. Some feminists have even argued that directly democratic organisations are specifically female political forms. [see e.g. Nancy Hartsock “Feminist Theory and the Development of Revolutionary Strategy,” in Zeila Eisenstein, ed., Capitalist Patriarchy and the Case for Socialist Feminism, pp. 56–77] Like all anarchists, anarcha-feminists recognise that self-liberation is the key to women’s equality and thus, freedom. Thus Emma Goldman:

“Her development, her freedom, her independence, must come from and through herself. First, by asserting herself as a personality, and not as a sex commodity. Second, by refusing the right of anyone over her body; by refusing to bear children, unless she wants them, by refusing to be a servant to God, the State, society, the husband, the family, etc., by making her life simpler, but deeper and richer. That is, by trying to learn the meaning and substance of life in all its complexities; by freeing herself from the fear of public opinion and public condemnation.” [Anarchism and Other Essays, p. 211]

Anarcha-feminism tries to keep feminism from becoming influenced and dominated by authoritarian ideologies of either the right or left. It proposes direct action and self-help instead of the mass reformist campaigns favoured by the “official” feminist movement, with its creation of hierarchical and centralist organisations and its illusion that having more women bosses, politicians, and soldiers is a move towards “equality.” Anarcha-feminists would point out that the so-called “management science” which women have to learn in order to become mangers in capitalist companies is essentially a set of techniques for controlling and exploiting wage workers in corporate hierarchies, whereas “feminising” society requires the elimination of capitalist wage-slavery and managerial domination altogether. Anarcha-feminists realise that learning how to become an effective exploiter or oppressor is not the path to equality (as one member of the Mujeres Libres put it, ”[w]e did not want to substitute a feminist hierarchy for a masculine one” [quoted by Martha A. Ackelsberg, Free Women of Spain, pp. 22–3] — also see section B.1.4 for a further discussion on patriarchy and hierarchy).

Hence anarchism’s traditional hostility to liberal (or mainstream) feminism, while supporting women’s liberation and equality. Federica Montseny (a leading figure in the Spanish Anarchist movement) argued that such feminism advocated equality for women, but did not challenge existing institutions. She argued that (mainstream) feminism’s only ambition is to give to women of a particular class the opportunity to participate more fully in the existing system of privilege and if these institutions “are unjust when men take advantage of them, they will still be unjust if women take advantage of them.” [quoted by Martha A. Ackelsberg, Op. Cit., p. 119] Thus, for anarchists, women’s freedom did not mean an equal chance to become a boss or a wage slave, a voter or a politician, but rather to be a free and equal individual co-operating as equals in free associations. “Feminism,” stressed Peggy Kornegger, “doesn’t mean female corporate power or a woman President; it means no corporate power and no Presidents. The Equal Rights Amendment will not transform society; it only gives women the ‘right’ to plug into a hierarchical economy. Challenging sexism means challenging all hierarchy — economic, political, and personal. And that means an anarcha-feminist revolution.” [Op. Cit., p. 27]

Anarchism, as can be seen, included a class and economic analysis which is missing from mainstream feminism while, at the same time, showing an awareness to domestic and sex-based power relations which eluded the mainstream socialist movement. This flows from our hatred of hierarchy. As Mozzoni put it, “Anarchy defends the cause of all the oppressed, and because of this, and in a special way, it defends your [women’s] cause, oh! women, doubly oppressed by present society in both the social and private spheres.” [quoted by Moya, Op. Cit., p. 203] This means that, to quote a Chinese anarchist, what anarchists “mean by equality between the sexes is not just that the men will no longer oppress women. We also want men to no longer to be oppressed by other men, and women no longer to be oppressed by other women.” Thus women should “completely overthrow rulership, force men to abandon all their special privileges and become equal to women, and make a world with neither the oppression of women nor the oppression of men.” [He Zhen, quoted by Peter Zarrow, Anarchism and Chinese Political Culture, p. 147]

So, in the historic anarchist movement, as Martha Ackelsberg notes, liberal/mainstream feminism was considered as being “too narrowly focused as a strategy for women’s emancipation; sexual struggle could not be separated from class struggle or from the anarchist project as a whole.” [Op. Cit., p. 119] Anarcha-feminism continues this tradition by arguing that all forms of hierarchy are wrong, not just patriarchy, and that feminism is in conflict with its own ideals if it desires simply to allow women to have the same chance of being a boss as a man does. They simply state the obvious, namely that they “do not believe that power in the hands of women could possibly lead to a non-coercive society” nor do they “believe that anything good can come out of a mass movement with a leadership elite.” The “central issues are always power and social hierarchy” and so people “are free only when they have power over their own lives.” [Carole Ehrlich, “Socialism, Anarchism and Feminism”, Quiet Rumours: An Anarcha-Feminist Reader, p. 44] For if, as Louise Michel put it, “a proletarian is a slave; the wife of a proletarian is even more a slave” ensuring that the wife experiences an equal level of oppression as the husband misses the point. [Op. Cit., p. 141]

Anarcha-feminists, therefore, like all anarchists oppose capitalism as a denial of liberty. Their critique of hierarchy in the society does not start and end with patriarchy. It is a case of wanting freedom everywhere, of wanting to ”[b]reak up … every home that rests in slavery! Every marriage that represents the sale and transfer of the individuality of one of its parties to the other! Every institution, social or civil, that stands between man and his right; every tie that renders one a master, another a serf.” [Voltairine de Cleyre, “The Economic Tendency of Freethought”, The Voltairine de Cleyre Reader, p. 72] The ideal that an “equal opportunity” capitalism would free women ignores the fact that any such system would still see working class women oppressed by bosses (be they male or female). For anarcha-feminists, the struggle for women’s liberation cannot be separated from the struggle against hierarchy as such. As L. Susan Brown puts it:

“Anarchist-feminism, as an expression of the anarchist sensibility applied to feminist concerns, takes the individual as its starting point and, in opposition to relations of domination and subordination, argues for non-instrumental economic forms that preserve individual existential freedom, for both men and women.” [The Politics of Individualism, p. 144]

Anarcha-feminists have much to contribute to our understanding of the origins of the ecological crisis in the authoritarian values of hierarchical civilisation. For example, a number of feminist scholars have argued that the domination of nature has paralleled the domination of women, who have been identified with nature throughout history (See, for example, Caroline Merchant, The Death of Nature, 1980). Both women and nature are victims of the obsession with control that characterises the authoritarian personality. For this reason, a growing number of both radical ecologists and feminists are recognising that hierarchies must be dismantled in order to achieve their respective goals.

In addition, anarcha-feminism reminds us of the importance of treating women equally with men while, at the same time, respecting women’s differences from men. In other words, that recognising and respecting diversity includes women as well as men. Too often many male anarchists assume that, because they are (in theory) opposed to sexism, they are not sexist in practice. Such an assumption is false. Anarcha-feminism brings the question of consistency between theory and practice to the front of social activism and reminds us all that we must fight not only external constraints but also internal ones.

This means that anarcha-feminism urges us to practice what we preach. As Voltairine de Cleyre argued, “I never expect men to give us liberty. No, Women, we are not worth it, until we take it.” This involves “insisting on a new code of ethics founded on the law of equal freedom: a code recognising the complete individuality of woman. By making rebels wherever we can. By ourselves living our beliefs . … We are revolutionists. And we shall use propaganda by speech, deed, and most of all life — being what we teach.” Thus anarcha-feminists, like all anarchists, see the struggle against patriarchy as being a struggle of the oppressed for their own self-liberation, for ”as a class I have nothing to hope from men . .. No tyrant ever renounced his tyranny until he had to. If history ever teaches us anything it teaches this. Therefore my hope lies in creating rebellion in the breasts of women.” [“The Gates of Freedom”, pp. 235–250, Eugenia C. Delamotte, Gates of Freedom, p. 249 and p. 239] This was sadly as applicable within the anarchist movement as it was outside it in patriarchal society.

Faced with the sexism of male anarchists who spoke of sexual equality, women anarchists in Spain organised themselves into the Mujeres Libres organisation to combat it. They did not believe in leaving their liberation to some day after the revolution. Their liberation was a integral part of that revolution and had to be started today. In this they repeated the conclusions of anarchist women in Illinois Coal towns who grew tried of hearing their male comrades “shout in favour” of sexual equality “in the future society” while doing nothing about it in the here and now. They used a particularly insulting analogy, comparing their male comrades to priests who “make false promises to the starving masses … [that] there will be rewards in paradise.” The argued that mothers should make their daughters “understand that the difference in sex does not imply inequality in rights” and that as well as being “rebels against the social system of today,” they “should fight especially against the oppression of men who would like to retain women as their moral and material inferior.” [Ersilia Grandi, quoted by Caroline Waldron Merithew, Anarchist Motherhood, p. 227] They formed the “Luisa Michel” group to fight against capitalism and patriarchy in the upper Illinois valley coal towns over three decades before their Spanish comrades organised themselves.

For anarcha-feminists, combating sexism is a key aspect of the struggle for freedom. It is not, as many Marxist socialists argued before the rise of feminism, a diversion from the “real” struggle against capitalism which would somehow be automatically solved after the revolution. It is an essential part of the struggle:

“We do not need any of your titles … We want none of them. What we do want is knowledge and education and liberty. We know what our rights are and we demand them. Are we not standing next to you fighting the supreme fight? Are you not strong enough, men, to make part of that supreme fight a struggle for the rights of women? And then men and women together will gain the rights of all humanity.” [Louise Michel, Op. Cit., p. 142]

A key part of this revolutionising modern society is the transformation of the current relationship between the sexes. Marriage is a particular evil for “the old form of marriage, based on the Bible, ‘till death doth part,’ … [is] an institution that stands for the sovereignty of the man over the women, of her complete submission to his whims and commands.” Women are reduced “to the function of man’s servant and bearer of his children.” [Goldman, Op. Cit., pp. 220–1] Instead of this, anarchists proposed “free love,” that is couples and families based on free agreement between equals than one partner being in authority and the other simply obeying. Such unions would be without sanction of church or state for “two beings who love each other do not need permission from a third to go to bed.” [Mozzoni, quoted by Moya, Op. Cit., p. 200]

Equality and freedom apply to more than just relationships. For “if social progress consists in a constant tendency towards the equalisation of the liberties of social units, then the demands of progress are not satisfied so long as half society, Women, is in subjection… . Woman … is beginning to feel her servitude; that there is a requisite acknowledgement to be won from her master before he is put down and she exalted to — Equality. This acknowledgement is, the freedom to control her own person. “ [Voltairine de Cleyre, “The Gates of Freedom”, Op. Cit., p. 242] Neither men nor state nor church should say what a woman does with her body. A logical extension of this is that women must have control over their own reproductive organs. Thus anarcha-feminists, like anarchists in general, are pro-choice and pro-reproductive rights (i.e. the right of a woman to control her own reproductive decisions). This is a long standing position. Emma Goldman was persecuted and incarcerated because of her public advocacy of birth control methods and the extremist notion that women should decide when they become pregnant (as feminist writer Margaret Anderson put it, “In 1916, Emma Goldman was sent to prison for advocating that ‘women need not always keep their mouth shut and their wombs open.’”).

Anarcha-feminism does not stop there. Like anarchism in general, it aims at changing all aspects of society not just what happens in the home. For, as Goldman asked, “how much independence is gained if the narrowness and lack of freedom of the home is exchanged for the narrowness and lack of freedom of the factory, sweat-shop, department store, or office?” Thus women’s equality and freedom had to be fought everywhere and defended against all forms of hierarchy. Nor can they be achieved by voting. Real liberation, argue anarcha-feminists, is only possible by direct action and anarcha-feminism is based on women’s self-activity and self-liberation for while the “right to vote, or equal civil rights, may be good demands … true emancipation begins neither at the polls nor in the courts. It begins in woman’s soul … her freedom will reach as far as her power to achieve freedom reaches.” [Goldman, Op. Cit., p. 216 and p. 224]