#other than what I assume was the writer's room's of understanding feminism.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

absolutely hate it when something stupid and negative somebody wrote on one of my positive fandom posts gets stuck in my head but like, i truly wish i'd asked the rando person who said they just Couldn't keep watching 13's era because of the constant put downs of men if they'd legitimately gotten her era and moffat era dw confused (which does, quite frankly, have a ~girls rule boys smell~ lean to it uncomfortably often) because that is simply preferable to the alternative that they meant it and genuinely think that men Not being front and centre is an affront to men and that they couldn't deal with it. But I blocked them bc Be Real. But I regret not asking even though I strongly suspect that the answer would have given me a headache.

#dw shit#moffat's era specialised in casually offensive to the point that#there are far easier repeated offenders to clock than the quantity of in general#derogatory comments aimed at men to prop up women for??? no reason??#other than what I assume was the writer's room's of understanding feminism.#(so Not feminism at all but i digress)#but damn if you pay attention it's so casually digging at men so often#which then disappears when 13 rolls around#except for One single instance which Coincidentally was a Missy reference in an ep#literally 30 minutes before the master shows up again#(as in#13's got the upgrade to woman line. that was cribbed from missy.)#and is very obviously a win wink nudge nudge#but.. 13's era... is shit to men???#so much to dig into there#none of it good

28 notes

·

View notes

Link

I.

For a long time, academic feminism in America has been closely allied to the practical struggle to achieve justice and equality for women. Feminist theory has been understood by theorists as not just fancy words on paper; theory is connected to proposals for social change. Thus feminist scholars have engaged in many concrete projects: the reform of rape law; winning attention and legal redress for the problems of domestic violence and sexual harassment; improving women’s economic opportunities, working conditions, and education; winning pregnancy benefits for female workers; campaigning against the trafficking of women and girls in prostitution; working for the social and political equality of lesbians and gay men.

Indeed, some theorists have left the academy altogether, feeling more comfortable in the world of practical politics, where they can address these urgent problems directly. Those who remain in the academy have frequently made it a point of honor to be academics of a committed practical sort, eyes always on the material conditions of real women, writing always in a way that acknowledges those real bodies and those real struggles. One cannot read a page of Catharine MacKinnon, for example, without being engaged with a real issue of legal and institutional change. If one disagrees with her proposals--and many feminists disagree with them--the challenge posed by her writing is to find some other way of solving the problem that has been vividly delineated.

Feminists have differed in some cases about what is bad, and about what is needed to make things better; but all have agreed that the circumstances of women are often unjust and that law and political action can make them more nearly just. MacKinnon, who portrays hierarchy and subordination as endemic to our entire culture, is also committed to, and cautiously optimistic about, change through law--the domestic law of rape and sexual harassment and international human rights law. Even Nancy Chodorow, who, in The Reproduction of Mothering, offered a depressing account of the replication of oppressive gender categories in child-rearing, argued that this situation could change. Men and women could decide, understanding the unhappy consequences of these habits, that they will henceforth do things differently; and changes in laws and institutions can assist in such decisions.

Feminist theory still looks like this in many parts of the world. In India, for example, academic feminists have thrown themselves into practical struggles, and feminist theorizing is closely tethered to practical commitments such as female literacy, the reform of unequal land laws, changes in rape law (which, in India today, has most of the flaws that the first generation of American feminists targeted), the effort to get social recognition for problems of sexual harassment and domestic violence. These feminists know that they live in the middle of a fiercely unjust reality; they cannot live with themselves without addressing it more or less daily, in their theoretical writing and in their activities outside the seminar room.

In the United States, however, things have been changing. One observes a new, disquieting trend. It is not only that feminist theory pays relatively little attention to the struggles of women outside the United States. (This was always a dispiriting feature even of much of the best work of the earlier period.) Something more insidious than provincialism has come to prominence in the American academy. It is the virtually complete turning from the material side of life, toward a type of verbal and symbolic politics that makes only the flimsiest of connections with the real situation of real women.

Feminist thinkers of the new symbolic type would appear to believe that the way to do feminist politics is to use words in a subversive way, in academic publications of lofty obscurity and disdainful abstractness. These symbolic gestures, it is believed, are themselves a form of political resistance; and so one need not engage with messy things such as legislatures and movements in order to act daringly. The new feminism, moreover, instructs its members that there is little room for large-scale social change, and maybe no room at all. We are all, more or less, prisoners of the structures of power that have defined our identity as women; we can never change those structures in a large-scale way, and we can never escape from them. All that we can hope to do is to find spaces within the structures of power in which to parody them, to poke fun at them, to transgress them in speech. And so symbolic verbal politics, in addition to being offered as a type of real politics, is held to be the only politics that is really possible.

These developments owe much to the recent prominence of French postmodernist thought. Many young feminists, whatever their concrete affiliations with this or that French thinker, have been influenced by the extremely French idea that the intellectual does politics by speaking seditiously, and that this is a significant type of political action. Many have also derived from the writings of Michel Foucault (rightly or wrongly) the fatalistic idea that we are prisoners of an all-enveloping structure of power, and that real-life reform movements usually end up serving power in new and insidious ways. Such feminists therefore find comfort in the idea that the subversive use of words is still available to feminist intellectuals. Deprived of the hope of larger or more lasting changes, we can still perform our resistance by the reworking of verbal categories, and thus, at the margins, of the selves who are constituted by them.

One American feminist has shaped these developments more than any other. Judith Butler seems to many young scholars to define what feminism is now. Trained as a philosopher, she is frequently seen (more by people in literature than by philosophers) as a major thinker about gender, power, and the body. As we wonder what has become of old-style feminist politics and the material realities to which it was committed, it seems necessary to reckon with Butler’s work and influence, and to scrutinize the arguments that have led so many to adopt a stance that looks very much like quietism and retreat.

II.

It is difficult to come to grips with Butler’s ideas, because it is difficult to figure out what they are. Butler is a very smart person. In public discussions, she proves that she can speak clearly and has a quick grasp of what is said to her. Her written style, however, is ponderous and obscure. It is dense with allusions to other theorists, drawn from a wide range of different theoretical traditions. In addition to Foucault, and to a more recent focus on Freud, Butler’s work relies heavily on the thought of Louis Althusser, the French lesbian theorist Monique Wittig, the American anthropologist Gayle Rubin, Jacques Lacan, J.L. Austin, and the American philosopher of language Saul Kripke. These figures do not all agree with one another, to say the least; so an initial problem in reading Butler is that one is bewildered to find her arguments buttressed by appeal to so many contradictory concepts and doctrines, usually without any account of how the apparent contradictions will be resolved.

A further problem lies in Butler’s casual mode of allusion. The ideas of these thinkers are never described in enough detail to include the uninitiated (if you are not familiar with the Althusserian concept of “interpellation,” you are lost for chapters) or to explain to the initiated how, precisely, the difficult ideas are being understood. Of course, much academic writing is allusive in some way: it presupposes prior knowledge of certain doctrines and positions. But in both the continental and the Anglo-American philosophical traditions, academic writers for a specialist audience standardly acknowledge that the figures they mention are complicated, and the object of many different interpretations. They therefore typically assume the responsibility of advancing a definite interpretation among the contested ones, and of showing by argument why they have interpreted the figure as they have, and why their own interpretation is better than others.

We find none of this in Butler. Divergent interpretations are simply not considered--even where, as in the cases of Foucault and Freud, she is advancing highly contestable interpretations that would not be accepted by many scholars. Thus one is led to the conclusion that the allusiveness of the writing cannot be explained in the usual way, by positing an audience of specialists eager to debate the details of an esoteric academic position. The writing is simply too thin to satisfy any such audience. It is also obvious that Butler’s work is not directed at a non-academic audience eager to grapple with actual injustices. Such an audience would simply be baffled by the thick soup of Butler’s prose, by its air of in-group knowingness, by its extremely high ratio of names to explanations.

To whom, then, is Butler speaking? It would seem that she is addressing a group of young feminist theorists in the academy who are neither students of philosophy, caring about what Althusser and Freud and Kripke really said, nor outsiders, needing to be informed about the nature of their projects and persuaded of their worth. This implied audience is imagined as remarkably docile. Subservient to the oracular voice of Butler’s text, and dazzled by its patina of high-concept abstractness, the imagined reader poses few questions, requests no arguments and no clear definitions of terms.

Still more strangely, the implied reader is expected not to care greatly about Butler’s own final view on many matters. For a large proportion of the sentences in any book by Butler--especially sentences near the end of chapters--are questions. Sometimes the answer that the question expects is evident. But often things are much more indeterminate. Among the non-interrogative sentences, many begin with “Consider…” or “One could suggest…”--in such a way that Butler never quite tells the reader whether she approves of the view described. Mystification as well as hierarchy are the tools of her practice, a mystification that eludes criticism because it makes few definite claims.

Take two representative examples:

What does it mean for the agency of a subject to presuppose its own subordination? Is the act of presupposing the same as the act of reinstating, or is there a discontinuity between the power presupposed and the power reinstated? Consider that in the very act by which the subject reproduces the conditions of its own subordination, the subject exemplifies a temporally based vulnerability that belongs to those conditions, specifically, to the exigencies of their renewal.

And:

Such questions cannot be answered here, but they indicate a direction for thinking that is perhaps prior to the question of conscience, namely, the question that preoccupied Spinoza, Nietzsche, and most recently, Giorgio Agamben: How are we to understand the desire to be as a constitutive desire? Resituating conscience and interpellation within such an account, we might then add to this question another: How is such a desire exploited not only by a law in the singular, but by laws of various kinds such that we yield to subordination in order to maintain some sense of social “being”?

Why does Butler prefer to write in this teasing, exasperating way? The style is certainly not unprecedented. Some precincts of the continental philosophical tradition, though surely not all of them, have an unfortunate tendency to regard the philosopher as a star who fascinates, and frequently by obscurity, rather than as an arguer among equals. When ideas are stated clearly, after all, they may be detached from their author: one can take them away and pursue them on one’s own. When they remain mysterious (indeed, when they are not quite asserted), one remains dependent on the originating authority. The thinker is heeded only for his or her turgid charisma. One hangs in suspense, eager for the next move. When Butler does follow that “direction for thinking,” what will she say? What does it mean, tell us please, for the agency of a subject to presuppose its own subordination? (No clear answer to this question, so far as I can see, is forthcoming.) One is given the impression of a mind so profoundly cogitative that it will not pronounce on anything lightly: so one waits, in awe of its depth, for it finally to do so.

In this way obscurity creates an aura of importance. It also serves another related purpose. It bullies the reader into granting that, since one cannot figure out what is going on, there must be something significant going on, some complexity of thought, where in reality there are often familiar or even shopworn notions, addressed too simply and too casually to add any new dimension of understanding. When the bullied readers of Butler’s books muster the daring to think thus, they will see that the ideas in these books are thin. When Butler’s notions are stated clearly and succinctly, one sees that, without a lot more distinctions and arguments, they don’t go far, and they are not especially new. Thus obscurity fills the void left by an absence of a real complexity of thought and argument.

Last year Butler won the first prize in the annual Bad Writing Contest sponsored by the journal Philosophy and Literature, for the following sentence:

The move from a structuralist account in which capital is understood to structure social relations in relatively homologous ways to a view of hegemony in which power relations are subject to repetition, convergence, and rearticulation brought the question of temporality into the thinking of structure, and marked a shift from a form of Althusserian theory that takes structural totalities as theoretical objects to one in which the insights into the contingent possibility of structure inaugurate a renewed conception of hegemony as bound up with the contingent sites and strategies of the rearticulation of power.

Now, Butler might have written: “Marxist accounts, focusing on capital as the central force structuring social relations, depicted the operations of that force as everywhere uniform. By contrast, Althusserian accounts, focusing on power, see the operations of that force as variegated and as shifting over time.” Instead, she prefers a verbosity that causes the reader to expend so much effort in deciphering her prose that little energy is left for assessing the truth of the claims. Announcing the award, the journal’s editor remarked that “it’s possibly the anxiety-inducing obscurity of such writing that has led Professor Warren Hedges of Southern Oregon University to praise Judith Butler as `probably one of the ten smartest people on the planet.’” (Such bad writing, incidentally, is by no means ubiquitous in the “queer theory” group of theorists with which Butler is associated. David Halperin, for example, writes about the relationship between Foucault and Kant, and about Greek homosexuality, with philosophical clarity and historical precision.)

Butler gains prestige in the literary world by being a philosopher; many admirers associate her manner of writing with philosophical profundity. But one should ask whether it belongs to the philosophical tradition at all, rather than to the closely related but adversarial traditions of sophistry and rhetoric. Ever since Socrates distinguished philosophy from what the sophists and the rhetoricians were doing, it has been a discourse of equals who trade arguments and counter-arguments without any obscurantist sleight-of-hand. In that way, he claimed, philosophy showed respect for the soul, while the others’ manipulative methods showed only disrespect. One afternoon, fatigued by Butler on a long plane trip, I turned to a draft of a student’s dissertation on Hume’s views of personal identity. I quickly felt my spirits reviving. Doesn’t she write clearly, I thought with pleasure, and a tiny bit of pride. And Hume, what a fine, what a gracious spirit: how kindly he respects the reader’s intelligence, even at the cost of exposing his own uncertainty.

III.

Butler’s main idea, first introduced in Gender Trouble in 1989 and repeated throughout her books, is that gender is a social artifice. Our ideas of what women and men are reflect nothing that exists eternally in nature. Instead they derive from customs that embed social relations of power.

This notion, of course, is nothing new. The denaturalizing of gender was present already in Plato, and it received a great boost from John Stuart Mill, who claimed in The Subjection of Women that “what is now called the nature of women is an eminently artificial thing.” Mill saw that claims about “women’s nature” derive from, and shore up, hierarchies of power: womanliness is made to be whatever would serve the cause of keeping women in subjection, or, as he put it, “enslav[ing] their minds.” With the family as with feudalism, the rhetoric of nature itself serves the cause of slavery. “The subjection of women to men being a universal custom, any departure from it quite naturally appears unnatural…. But was there ever any domination which did not appear natural to those who possessed it?”

Mill was hardly the first social constructionist. Similar ideas about anger, greed, envy, and other prominent features of our lives had been commonplace in the history of philosophy since ancient Greece. And Mill’s application of familiar notions of social-construction to gender needed, and still needs, much fuller development; his suggestive remarks did not yet amount to a theory of gender. Long before Butler came on the scene, many feminists contributed to the articulation of such an account.

In work published in the 1970s and 1980s, Catharine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin argued that the conventional understanding of gender roles is a way of ensuring continued male domination in sexual relations, as well as in the public sphere. They took the core of Mill’s insight into a sphere of life concerning which the Victorian philosopher had said little. (Not nothing, though: in 1869 Mill already understood that the failure to criminalize rape within marriage defined woman as a tool for male use and negated her human dignity.) Before Butler, MacKinnon and Dworkin addressed the feminist fantasy of an idyllic natural sexuality of women that only needed to be “liberated”; and argued that social forces go so deep that we should not suppose we have access to such a notion of “nature.” Before Butler, they stressed the ways in which male-dominated power structures marginalize and subordinate not only women, but also people who would like to choose a same-sex relationship. They understood that discrimination against gays and lesbians is a way of enforcing the familiar hierarchically ordered gender roles; and so they saw discrimination against gays and lesbians as a form of sex discrimination.

Before Butler, the psychologist Nancy Chodorow gave a detailed and compelling account of how gender differences replicate themselves across the generations: she argued that the ubiquity of these mechanisms of replication enables us to understand how what is artificial can nonetheless be nearly ubiquitous. Before Butler, the biologist Anne Fausto Sterling, through her painstaking criticism of experimental work allegedly supporting the naturalness of conventional gender distinctions, showed how deeply social power-relations had compromised the objectivity of scientists: Myths of Gender (1985) was an apt title for what she found in the biology of the time. (Other biologists and primatologists also contributed to this enterprise.) Before Butler, the political theorist Susan Moller Okin explored the role of law and political thought in constructing a gendered destiny for women in the family; and this project, too, was pursued further by a number of feminists in law and political philosophy. Before Butler, Gayle Rubin’s important anthropological account of subordination, The Traffic in Women (1975), provided a valuable analysis of the relationship between the social organization of gender and the asymmetries of power.

So what does Butler’s work add to this copious body of writing? Gender Trouble and Bodies that Matter contain no detailed argument against biological claims of “natural” difference, no account of mechanisms of gender replication, and no account of the legal shaping of the family; nor do they contain any detailed focus on possibilities for legal change. What, then, does Butler offer that we might not find more fully done in earlier feminist writings? One relatively original claim is that when we recognize the artificiality of gender distinctions, and refrain from thinking of them as expressing an independent natural reality, we will also understand that there is no compelling reason why the gender types should have been two (correlated with the two biological sexes), rather than three or five or indefinitely many. “When the constructed status of gender is theorized as radically independent of sex, gender itself becomes a free-floating artifice,” she writes.

From this claim it does not follow, for Butler, that we can freely reinvent the genders as we like: she holds, indeed, that there are severe limits to our freedom. She insists that we should not naively imagine that there is a pristine self that stands behind society, ready to emerge all pure and liberated: “There is no self that is prior to the convergence or who maintains `integrity’ prior to its entrance into this conflicted cultural field. There is only a taking up of the tools where they lie, where the very `taking up’ is enabled by the tool lying there.” Butler does claim, though, that we can create categories that are in some sense new ones, by means of the artful parody of the old ones. Thus her best known idea, her conception of politics as a parodic performance, is born out of the sense of a (strictly limited) freedom that comes from the recognition that one’s ideas of gender have been shaped by forces that are social rather than biological. We are doomed to repetition of the power structures into which we are born, but we can at least make fun of them; and some ways of making fun are subversive assaults on the original norms.

The idea of gender as performance is Butler’s most famous idea, and so it is worth pausing to scrutinize it more closely. She introduced the notion intuitively, in Gender Trouble, without invoking theoretical precedent. Later she denied that she was referring to quasi-theatrical performance, and associated her notion instead with Austin’s account of speech acts in How to Do Things with Words. Austin’s linguistic category of “performatives” is a category of linguistic utterances that function, in and of themselves, as actions rather than as assertions. When (in appropriate social circumstances) I say “I bet ten dollars,” or “I’m sorry,” or “I do” (in a marriage ceremony), or “I name this ship…,” I am not reporting on a bet or an apology or a marriage or a naming ceremony, I am conducting one.

Butler’s analogous claim about gender is not obvious, since the “performances” in question involve gesture, dress, movement, and action, as well as language. Austin’s thesis, which is restricted to a rather technical analysis of a certain class of sentences, is in fact not especially helpful to Butler in developing her ideas. Indeed, though she vehemently repudiates readings of her work that associate her view with theater, thinking about the Living Theater’s subversive work with gender seems to illuminate her ideas far more than thinking about Austin.

Nor is Butler’s treatment of Austin very plausible. She makes the bizarre claim that the fact that the marriage ceremony is one of dozens of examples of performatives in Austin’s text suggests “that the heterosexualization of the social bond is the paradigmatic form for those speech acts which bring about what they name.” Hardly. Marriage is no more paradigmatic for Austin than betting or ship-naming or promising or apologizing. He is interested in a formal feature of certain utterances, and we are given no reason to suppose that their content has any significance for his argument. It is usually a mistake to read earth-shaking significance into a philosopher’s pedestrian choice of examples. Should we say that Aristotle’s use of a low-fat diet to illustrate the practical syllogism suggests that chicken is at the heart of Aristotelian virtue? Or that Rawls’s use of travel plans to illustrate practical reasoning shows that A Theory of Justice aims at giving us all a vacation?

Leaving these oddities to one side, Butler’s point is presumably this: when we act and speak in a gendered way, we are not simply reporting on something that is already fixed in the world, we are actively constituting it, replicating it, and reinforcing it. By behaving as if there were male and female “natures,” we co-create the social fiction that these natures exist. They are never there apart from our deeds; we are always making them be there. At the same time, by carrying out these performances in a slightly different manner, a parodic manner, we can perhaps unmake them just a little.

Thus the one place for agency in a world constrained by hierarchy is in the small opportunities we have to oppose gender roles every time they take shape. When I find myself doing femaleness, I can turn it around, poke fun at it, do it a little bit differently. Such reactive and parodic performances, in Butler’s view, never destabilize the larger system. She doesn’t envisage mass movements of resistance or campaigns for political reform; only personal acts carried out by a small number of knowing actors. Just as actors with a bad script can subvert it by delivering the bad lines oddly, so too with gender: the script remains bad, but the actors have a tiny bit of freedom. Thus we have the basis for what, in Excitable Speech, Butler calls “an ironic hopefulness.”

Up to this point, Butler’s contentions, though relatively familiar, are plausible and even interesting, though one is already unsettled by her narrow vision of the possibilities for change. Yet Butler adds to these plausible claims about gender two other claims that are stronger and more contentious. The first is that there is no agent behind or prior to the social forces that produce the self. If this means only that babies are born into a gendered world that begins to replicate males and females almost immediately, the claim is plausible, but not surprising: experiments have for some time demonstrated that the way babies are held and talked to, the way their emotions are described, are profoundly shaped by the sex the adults in question believe the child to have. (The same baby will be bounced if the adults think it is a boy, cuddled if they think it is a girl; its crying will be labeled as fear if the adults think it is a girl, as anger if they think it is a boy.) Butler shows no interest in these empirical facts, but they do support her contention.

If she means, however, that babies enter the world completely inert, with no tendencies and no abilities that are in some sense prior to their experience in a gendered society, this is far less plausible, and difficult to support empirically. Butler offers no such support, preferring to remain on the high plane of metaphysical abstraction. (Indeed, her recent Freudian work may even repudiate this idea: it suggests, with Freud, that there are at least some presocial impulses and tendencies, although, typically, this line is not clearly developed.) Moreover, such an exaggerated denial of pre-cultural agency takes away some of the resources that Chodorow and others use when they try to account for cultural change in the direction of the better.

Butler does in the end want to say that we have a kind of agency, an ability to undertake change and resistance. But where does this ability come from, if there is no structure in the personality that is not thoroughly power’s creation? It is not impossible for Butler to answer this question, but she certainly has not answered it yet, in a way that would convince those who believe that human beings have at least some pre-cultural desires--for food, for comfort, for cognitive mastery, for survival--and that this structure in the personality is crucial in the explanation of our development as moral and political agents. One would like to see her engage with the strongest forms of such a view, and to say, clearly and without jargon, exactly why and where she rejects them. One would also like to hear her speak about real infants, who do appear to manifest a structure of striving that influences from the start their reception of cultural forms.

Butler’s second strong claim is that the body itself, and especially the distinction between the two sexes, is also a social construction. She means not only that the body is shaped in many ways by social norms of how men and women should be; she means also that the fact that a binary division of sexes is taken as fundamental, as a key to arranging society, is itself a social idea that is not given in bodily reality. What exactly does this claim mean, and how plausible is it?

Butler’s brief exploration of Foucault on hermaphrodites does show us society’s anxious insistence to classify every human being in one box or another, whether or not the individual fits a box; but of course it does not show that there are many such indeterminate cases. She is right to insist that we might have made many different classifications of body types, not necessarily focusing on the binary division as the most salient; and she is also right to insist that, to a large extent, claims of bodily sex difference allegedly based upon scientific research have been projections of cultural prejudice--though Butler offers nothing here that is nearly as compelling as Fausto Sterling’s painstaking biological analysis.

And yet it is much too simple to say that power is all that the body is. We might have had the bodies of birds or dinosaurs or lions, but we do not; and this reality shapes our choices. Culture can shape and reshape some aspects of our bodily existence, but it does not shape all the aspects of it. “In the man burdened by hunger and thirst,” as Sextus Empiricus observed long ago, “it is impossible to produce by argument the conviction that he is not so burdened.” This is an important fact also for feminism, since women’s nutritional needs (and their special needs when pregnant or lactating) are an important feminist topic. Even where sex difference is concerned, it is surely too simple to write it all off as culture; nor should feminists be eager to make such a sweeping gesture. Women who run or play basketball, for example, were right to welcome the demolition of myths about women’s athletic performance that were the product of male-dominated assumptions; but they were also right to demand the specialized research on women’s bodies that has fostered a better understanding of women’s training needs and women’s injuries. In short: what feminism needs, and sometimes gets, is a subtle study of the interplay of bodily difference and cultural construction. And Butler’s abstract pronouncements, floating high above all matter, give us none of what we need.

IV.

Suppose we grant Butler her most interesting claims up to this point: that the social structure of gender is ubiquitous, but we can resist it by subversive and parodic acts. Two significant questions remain. What should be resisted, and on what basis? What would the acts of resistance be like, and what would we expect them to accomplish?

Butler uses several words for what she takes to be bad and therefore worthy of resistance: the “repressive,” the “subordinating,” the “oppressive.” But she provides no empirical discussion of resistance of the sort that we find, say, in Barry Adam’s fascinating sociological study The Survival of Domination (1978), which studies the subordination of blacks, Jews, women, and gays and lesbians, and their ways of wrestling with the forms of social power that have oppressed them. Nor does Butler provide any account of the concepts of resistance and oppression that would help us, were we really in doubt about what we ought to be resisting.

Butler departs in this regard from earlier social-constructionist feminists, all of whom used ideas such as non-hierarchy, equality, dignity, autonomy, and treating as an end rather than a means, to indicate a direction for actual politics. Still less is she willing to elaborate any positive normative notion. Indeed, it is clear that Butler, like Foucault, is adamantly opposed to normative notions such as human dignity, or treating humanity as an end, on the grounds that they are inherently dictatorial. In her view, we ought to wait to see what the political struggle itself throws up, rather than prescribe in advance to its participants. Universal normative notions, she says, “colonize under the sign of the same.”

This idea of waiting to see what we get--in a word, this moral passivity--seems plausible in Butler because she tacitly assumes an audience of like-minded readers who agree (sort of) about what the bad things are--discrimination against gays and lesbians, the unequal and hierarchical treatment of women--and who even agree (sort of) about why they are bad (they subordinate some people to others, they deny people freedoms that they ought to have). But take that assumption away, and the absence of a normative dimension becomes a severe problem.

Try teaching Foucault at a contemporary law school, as I have, and you will quickly find that subversion takes many forms, not all of them congenial to Butler and her allies. As a perceptive libertarian student said to me, Why can’t I use these ideas to resist the tax structure, or the antidiscrimination laws, or perhaps even to join the militias? Others, less fond of liberty, might engage in the subversive performances of making fun of feminist remarks in class, or ripping down the posters of the lesbian and gay law students’ association. These things happen. They are parodic and subversive. Why, then, aren’t they daring and good?

Well, there are good answers to those questions, but you won’t find them in Foucault, or in Butler. Answering them requires discussing which liberties and opportunities human beings ought to have, and what it is for social institutions to treat human beings as ends rather than as means--in short, a normative theory of social justice and human dignity. It is one thing to say that we should be humble about our universal norms, and willing to learn from the experience of oppressed people. It is quite another thing to say that we don’t need any norms at all. Foucault, unlike Butler, at least showed signs in his late work of grappling with this problem; and all his writing is animated by a fierce sense of the texture of social oppression and the harm that it does.

Come to think of it, justice, understood as a personal virtue, has exactly the structure of gender in the Butlerian analysis: it is not innate or “natural,” it is produced by repeated performances (or as Aristotle said, we learn it by doing it), it shapes our inclinations and forces the repression of some of them. These ritual performances, and their associated repressions, are enforced by arrangements of social power, as children who won’t share on the playground quickly discover. Moreover, the parodic subversion of justice is ubiquitous in politics, as in personal life. But there is an important difference. Generally we dislike these subversive performances, and we think that young people should be strongly discouraged from seeing norms of justice in such a cynical light. Butler cannot explain in any purely structural or procedural way why the subversion of gender norms is a social good while the subversion of justice norms is a social bad. Foucault, we should remember, cheered for the Ayatollah, and why not? That, too, was resistance, and there was indeed nothing in the text to tell us that that struggle was less worthy than a struggle for civil rights and civil liberties.

There is a void, then, at the heart of Butler’s notion of politics. This void can look liberating, because the reader fills it implicitly with a normative theory of human equality or dignity. But let there be no mistake: for Butler, as for Foucault, subversion is subversion, and it can in principle go in any direction. Indeed, Butler’s naively empty politics is especially dangerous for the very causes she holds dear. For every friend of Butler, eager to engage in subversive performances that proclaim the repressiveness of heterosexual gender norms, there are dozens who would like to engage in subversive performances that flout the norms of tax compliance, of non-discrimination, of decent treatment of one’s fellow students. To such people we should say, you cannot simply resist as you please, for there are norms of fairness, decency, and dignity that entail that this is bad behavior. But then we have to articulate those norms--and this Butler refuses to do.

V.

What precisely does Butler offer when she counsels subversion? She tells us to engage in parodic performances, but she warns us that the dream of escaping altogether from the oppressive structures is just a dream: it is within the oppressive structures that we must find little spaces for resistance, and this resistance cannot hope to change the overall situation. And here lies a dangerous quietism.

If Butler means only to warn us against the dangers of fantasizing an idyllic world in which sex raises no serious problems, she is wise to do so. Yet frequently she goes much further. She suggests that the institutional structures that ensure the marginalization of lesbians and gay men in our society, and the continued inequality of women, will never be changed in a deep way; and so our best hope is to thumb our noses at them, and to find pockets of personal freedom within them. “Called by an injurious name, I come into social being, and because I have a certain inevitable attachment to my existence, because a certain narcissism takes hold of any term that confers existence, I am led to embrace the terms that injure me because they constitute me socially.” In other words: I cannot escape the humiliating structures without ceasing to be, so the best I can do is mock, and use the language of subordination stingingly. In Butler, resistance is always imagined as personal, more or less private, involving no unironic, organized public action for legal or institutional change.

Isn’t this like saying to a slave that the institution of slavery will never change, but you can find ways of mocking it and subverting it, finding your personal freedom within those acts of carefully limited defiance? Yet it is a fact that the institution of slavery can be changed, and was changed--but not by people who took a Butler-like view of the possibilities. It was changed because people did not rest content with parodic performance: they demanded, and to some extent they got, social upheaval. It is also a fact that the institutional structures that shape women’s lives have changed. The law of rape, still defective, has at least improved; the law of sexual harassment exists, where it did not exist before; marriage is no longer regarded as giving men monarchical control over women’s bodies. These things were changed by feminists who would not take parodic performance as their answer, who thought that power, where bad, should, and would, yield before justice.

Butler not only eschews such a hope, she takes pleasure in its impossibility. She finds it exciting to contemplate the alleged immovability of power, and to envisage the ritual subversions of the slave who is convinced that she must remain such. She tells us--this is the central thesis of The Psychic Life of Power--that we all eroticize the power structures that oppress us, and can thus find sexual pleasure only within their confines. It seems to be for that reason that she prefers the sexy acts of parodic subversion to any lasting material or institutional change. Real change would so uproot our psyches that it would make sexual satisfaction impossible. Our libidos are the creation of the bad enslaving forces, and thus necessarily sadomasochistic in structure.

Well, parodic performance is not so bad when you are a powerful tenured academic in a liberal university. But here is where Butler’s focus on the symbolic, her proud neglect of the material side of life, becomes a fatal blindness. For women who are hungry, illiterate, disenfranchised, beaten, raped, it is not sexy or liberating to reenact, however parodically, the conditions of hunger, illiteracy, disenfranchisement, beating, and rape. Such women prefer food, schools, votes, and the integrity of their bodies. I see no reason to believe that they long sadomasochistically for a return to the bad state. If some individuals cannot live without the sexiness of domination, that seems sad, but it is not really our business. But when a major theorist tells women in desperate conditions that life offers them only bondage, she purveys a cruel lie, and a lie that flatters evil by giving it much more power than it actually has.

Excitable Speech, Butler’s most recent book, which provides her analysis of legal controversies involving pornography and hate speech, shows us exactly how far her quietism extends. For she is now willing to say that even where legal change is possible, even where it has already happened, we should wish it away, so as to preserve the space within which the oppressed may enact their sadomasochistic rituals of parody.

As a work on the law of free speech, Excitable Speech is an unconscionably bad book. Butler shows no awareness of the major theoretical accounts of the First Amendment, and no awareness of the wide range of cases such a theory will need to take into consideration. She makes absurd legal claims: for example, she says that the only type of speech that has been held to be unprotected is speech that has been previously defined as conduct rather than speech. (In fact, there are many types of speech, from false or misleading advertising to libelous statements to obscenity as currently defined, which have never been claimed to be action rather than speech, and which are nonetheless denied First Amendment protection.) Butler even claims, mistakenly, that obscenity has been judged to be the equivalent of “fighting words.” It is not that Butler has an argument to back up her novel readings of the wide range of cases of unprotected speech that an account of the First Amendment would need to cover. She just has not noticed that there is this wide range of cases, or that her view is not a widely accepted legal view. Nobody interested in law can take her argument seriously.

But let us extract from Butler’s thin discussion of hate speech and pornography the core of her position. It is this: legal prohibitions of hate speech and pornography are problematic (though in the end she does not clearly oppose them) because they close the space within which the parties injured by that speech can perform their resistance. By this Butler appears to mean that if the offense is dealt with through the legal system, there will be fewer occasions for informal protest; and also, perhaps, that if the offense becomes rarer because of its illegality we will have fewer opportunities to protest its presence.

Well, yes. Law does close those spaces. Hate speech and pornography are extremely complicated subjects on which feminists may reasonably differ. (Still, one should state the contending views precisely: Butler’s account of MacKinnon is less than careful, stating that MacKinnon supports “ordinances against pornography” and suggesting that, despite MacKinnon’s explicit denial, they involve a form of censorship. Nowhere does Butler mention that what MacKinnon actually supports is a civil damage action in which particular women harmed through pornography can sue its makers and its distributors.)

But Butler’s argument has implications well beyond the cases of hate speech and pornography. It would appear to support not just quietism in these areas, but a much more general legal quietism--or, indeed, a radical libertarianism. It goes like this: let us do away with everything from building codes to non-discrimination laws to rape laws, because they close the space within which the injured tenants, the victims of discrimination, the raped women, can perform their resistance. Now, this is not the same argument radical libertarians use to oppose building codes and anti-discrimination laws; even they draw the line at rape. But the conclusions converge.

If Butler should reply that her argument pertains only to speech (and there is no reason given in the text for such a limitation, given the assimilation of harmful speech to conduct), then we can reply in the domain of speech. Let us get rid of laws against false advertising and unlicensed medical advice, for they close the space within which poisoned consumers and mutilated patients can perform their resistance! Again, if Butler does not approve of these extensions, she needs to make an argument that divides her cases from these cases, and it is not clear that her position permits her to make such a distinction.

For Butler, the act of subversion is so riveting, so sexy, that it is a bad dream to think that the world will actually get better. What a bore equality is! No bondage, no delight. In this way, her pessimistic erotic anthropology offers support to an amoral anarchist politics.

VI.

When we consider the quietism inherent in Butler’s writing, we have some keys to understanding Butler’s influential fascination with drag and cross-dressing as paradigms of feminist resistance. Butler’s followers understand her account of drag to imply that such performances are ways for women to be daring and subversive. I am unaware of any attempt by Butler to repudiate such readings.

But what is going on here? The woman dressed mannishly is hardly a new figure. Indeed, even when she was relatively new, in the nineteenth century, she was in another way quite old, for she simply replicated in the lesbian world the existing stereotypes and hierarchies of male-female society. What, we may well ask, is parodic subversion in this area, and what a kind of prosperous middle-class acceptance? Isn’t hierarchy in drag still hierarchy? And is it really true (as The Psychic Life of Power would seem to conclude) that domination and subordination are the roles that women must play in every sphere, and if not subordination, then mannish domination?

In short, cross-dressing for women is a tired old script--as Butler herself informs us. Yet she would have us see the script as subverted, made new, by the cross-dresser’s knowing symbolic sartorial gestures; but again we must wonder about the newness, and even the subversiveness. Consider Andrea Dworkin’s parody (in her novel Mercy) of a Butlerish parodic feminist, who announces from her posture of secure academic comfort:

The notion that bad things happen is both propagandistic and inadequate…. To understand a woman’s life requires that we affirm the hidden or obscure dimensions of pleasure, often in pain, and choice, often under duress. One must develop an eye for secret signs--the clothes that are more than clothes or decoration in the contemporary dialogue, for instance, or the rebellion hidden behind apparent conformity. There is no victim. There is perhaps an insufficiency of signs, an obdurate appearance of conformity that simply masks the deeper level on which choice occurs.

In prose quite unlike Butler’s, this passage captures the ambivalence of the implied author of some of Butler’s writings, who delights in her violative practice while turning her theoretical eye resolutely away from the material suffering of women who are hungry, illiterate, violated, beaten. There is no victim. There is only an insufficiency of signs.

Butler suggests to her readers that this sly send-up of the status quo is the only script for resistance that life offers. Well, no. Besides offering many other ways to be human in one’s personal life, beyond traditional norms of domination and subservience, life also offers many scripts for resistance that do not focus narcissistically on personal self-presentation. Such scripts involve feminists (and others, of course) in building laws and institutions, without much concern for how a woman displays her own body and its gendered nature: in short, they involve working for others who are suffering.

The great tragedy in the new feminist theory in America is the loss of a sense of public commitment. In this sense, Butler’s self-involved feminism is extremely American, and it is not surprising that it has caught on here, where successful middle-class people prefer to focus on cultivating the self rather than thinking in a way that helps the material condition of others. Even in America, however, it is possible for theorists to be dedicated to the public good and to achieve something through that effort.

Many feminists in America are still theorizing in a way that supports material change and responds to the situation of the most oppressed. Increasingly, however, the academic and cultural trend is toward the pessimistic flirtatiousness represented by the theorizing of Butler and her followers. Butlerian feminism is in many ways easier than the old feminism. It tells scores of talented young women that they need not work on changing the law, or feeding the hungry, or assailing power through theory harnessed to material politics. They can do politics in safety of their campuses, remaining on the symbolic level, making subversive gestures at power through speech and gesture. This, the theory says, is pretty much all that is available to us anyway, by way of political action, and isn’t it exciting and sexy?

In its small way, of course, this is a hopeful politics. It instructs people that they can, right now, without compromising their security, do something bold. But the boldness is entirely gestural, and insofar as Butler’s ideal suggests that these symbolic gestures really are political change, it offers only a false hope. Hungry women are not fed by this, battered women are not sheltered by it, raped women do not find justice in it, gays and lesbians do not achieve legal protections through it.

Finally there is despair at the heart of the cheerful Butlerian enterprise. The big hope, the hope for a world of real justice, where laws and institutions protect the equality and the dignity of all citizens, has been banished, even perhaps mocked as sexually tedious. Judith Butler’s hip quietism is a comprehensible response to the difficulty of realizing justice in America. But it is a bad response. It collaborates with evil. Feminism demands more and women deserve better.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The place of lesbians in women’s liberation and lesbophobia (1/2)

- Reading: Tales of the Lavender Menace by Karla Jay (part 2 here) At Karla Jay’s first Redstockings gathering:

“I would have never dared to question the leaders of a group I wanted to join. But after the [Redstockings] manifesto had been handed around, a woman named Rita Mae Brown, whom I knew slightly from NYU, pushed into the center of the room from her position in the doorway to take issue with Redstockings, even though it was her first meeting. Why, she demanded, didn’t Redstockings have a position on gay women? She began to argue that lesbian relationships were as important for a feminist group to embrace as the struggle to change men.” p. 43-44

The Redstockings completely forgetting to mention lesbians or to even have an opinion on the subject ready to be shared show how much of an afterthought we lesbians have always been in women’s liberation movement. We might only represent a fraction of women, but we still are women, and as such deserve liberation as much as any other straight women. The “struggle to change men” means having to interact, having to implicate oneself in reforming them. And what of women who would have nothing to do with their oppressors? What of women who do not want to spend all their energy and strength on the thankless task of making men understand that women are humans too?

“Rita [Mae Brown] alone had the courage to speak up at that Redstockings’ meeting, long before anyone else in New York’s feminist circles dared to be openly gay. Back then, apart from early activists such as Phyllis Lyon, Del Martin, and the other pioneering women of Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), few dared to admit in a public setting that they were lesbians. It was one thing to hang out in a gay bar where anyone simply assumed similar sexual proclivities or to be open in a gay student organization. It was quite another to announce one’s lesbianism and then demand it take center stage in a room full of straight feminists who were likely to be heterosexist (the word “homophobia” came later) and who had just issued an ultimatum to keep on sleeping with men as part of a program to mend the oppressors’ ways. Rita’s sharp challenge made Redstockings’ program seem quixotic to the point of being delusional: Were these women the oppressed or the oppressors?” p. 44

It’s a shame that being a lesbian had to remain a secret, on pain of being discriminated against. As lesbians, we have a unique outlook on the world around us and on men especially. We have way less interest in maintaining the status quo or in retaining any kind of ties with men. Our outlook on relationships with men are less tinted by the rosy lenses of the patriarchal promise of a happy-ever-after made of marriage and a brood of kids. Our very reasoning when it comes to women’s liberation is often less reformist than separatist; and as such our ideas are despised. Straight women wishing for romantic love cannot accept our conclusions that women would be better off independent from our oppressors.

“The leaders of Redstockings were disturbed and threatened by Rita [Mae Brown]’s behavior. They turned the conversation back around to men as our oppressors. Still, they looked uncomfortable. After all, Rita was calling them her oppressors when they were insisting that women like them (and us) were the most oppressed on earth. One of the main tenets of the “Redstockings Manifesto” was, “We identify the agents of our oppression as men… All other forms of exploitation and oppression (racism, capitalism, imperialism, etc. ) are extensions of male supremacy: men dominate women, a few men dominate the rest.” Although the group’s members identified with “the poorest, most brutally exploited women,” they would have found it counter productive, to put it mildly, to be forced to contemplate the ways that working-class women, disabled women, or Third World women (as we called women of coloraturas) were far worse off than someone like Kathie [Sarachild], who had attended Radcliffe College. By formulating a Marxist class analysis that emphasized unity among all women and foregrounded sexism as the tool to analyze other oppressions, they had hoped to quell demands by other women that double and triple oppressions receive priority.” p. 45

This kind of behaviour is obviously one of the reasons that led Kimberlé Crenshaw to pen down her vision of intersectionality in feminism. The founders of Redstockings and writers of its manifesto were mostly white, straight, university-educated women who had never and would never be oppressed on account of their sexual orientation, skin colour, social class or disability. As a result, the conclusions they draw in their theory can only be flawed and short-sighted. Their conclusions might be insightful, but only for a specific type of women. And according to Karla Jay, they seemed reluctant to widen their scope or take into account the experience of women different from them. While Rita Mae Brown (and other lesbians that later spoke up) offered them the opportunity to reflect on what they had concluded and make their reasoning better, more pragmatic, more adapted to the various circumstances of the women around them, they stood on their positions and dismissed lesbian concerns.

“Lesbianism was a more widely discussed issue than clashs and labor. Rita Mae Brown’s vociferous arrival in Redstockings had sparked discussion in Group X [the founding Redstockings cell], although reactions were mixed. Irene Peslikis, for one, was emboldened to admit to a long-term lesbian affair that Group X knew nothing about. But other members of Group X, echoing Betty Friedan’s assertion that lesbians were a “lavender menace,” began to blame gay women for causing dissension in the group and accused them of being “antifeminists.” Katie Sarachild wrote in Feminist Revolution that “many lesbians complained that they were excluded from the movement in the beginning often by simple virtue of the fact that the women in it spent so much time talking about such boring or irrelevant or disturbing to them subjects as sex with men, getting men to do the housework, and such related problems as abortions and childcare.”

What she and many other heterosexist Redstockings overlooked was that lesbians had been raised in families with men, had usually had sexual relationships with men, had worked with men, and sometimes lived with male roommates. Several lesbians I knew had children from previous marriages. What the straight women couldn’t see was that many Redstockings talked about men all the time the way dieters obsess about food. There were times when some of us, including a few of the heterosexuals, felt it would be more productive to focus on ways in which women could interact with one another positively.

The current of homophobia made many new members, including me, reluctant to mention homosexual experiences to the group. “ p. 65-66

Some straight members of Redstockings dismissed lesbians experiences as irrelevant to women’s liberation under the assumptions that because lesbians are not attracted to men and therefore would not engage in relationships with them in an ideal world, and so were not interacting with the male oppressor. In our world, this is a completely delusional assertion. Even in separatist communes, lesbians still have to deal with the law of the land, which has so far mostly been written and enacted by men. Lesbians too have fathers and brothers; lesbians too get sick and need to go to the hospital; lesbians too go out and use the amenities offered by society; lesbians too can be harassed and attacked by men. So women’s liberation concerns us as much as it does straight women, and our experiences with men and of sexism should not be dismissed as irrelevant.

And our experiences as lesbians tell us that straight women concerned with women’s liberation are most likely wasting their energy when they focus on trying to change men. Yes, these kind of discussions should take place, especially between women who do not want to renounce relationships with men; but lesbians are right to wonder why such subjects often take center place in women’s liberation movement.

Continued here in part 2.

#the place of lesbians in women's liberation#lesbophobia#karla jay#reading#tales of the lavender menace#women's liberation#homophobia#dismissing lesbian voices#still a familiar experience today

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

why would your social environment affect if you identify as a woman or nb?

I don’t know if you meant it to be, but this is a delightful question. I am going to be a complete nerd for 2k+ words at you.

“Gender” is distinct from “sex” because it’s not a body’s physical characteristics, it’s how society classifies and interprets that body. Sex is “That person has a vagina.” Gender is “This is a blend of society’s expectations about what bodies with vaginas are like, social expectations of how people with vaginas do or might or should act, behave, and feel, the actual lived experiences of people with vaginas, and a twist of lemon for zest.” Concepts of gender and what is “manly” and “womanly” can vary a lot. They’re social values, like “normal” or “legal” or “beautiful”, and they vary all the time. How well you fit your gender role depends a lot on how “gender” is defined.

800 years ago in Europe the general perception was that women were sinful, sensual, lustful people who required frequent sex and liked watching bloodsport. 200 years ago, the British aristocracy thought women were pure, innocent beings of moral purity with no sexual desire who fainted at the sight of blood. These days, we think differently in entirely new directions.

But this gets even more complicated, in part because human experience is really diverse and society’s narratives have to account for that. So 200 years ago, those beliefs about femininity being delicate and dainty and frail only really applied to women with aristocratic lineages, and “the lower classes” of women were believed to be vulgar, coarse, sexual, and earthy, which “explained” why they performed hard physical labor or worked as prostitutes.

Being trans or nonbinary isn’t just or even primarily about what characteristics you want your body to have. It’s about how you want to define yourself and be interpreted and interacted with by other people.

The writer Sylvia Plath lived 1932-1963, and she said:

“Being born a woman is my awful tragedy. From the moment I was conceived I was doomed to sprout breasts and ovaries rather than penis and scrotum; to have my whole circle of action, thought and feeling rigidly circumscribed by my inescapable feminity. Yes, my consuming desire to mingle with road crews, sailors and soldiers, bar room regulars–to be a part of a scene, anonymous, listening, recording–all is spoiled by the fact that I am a girl, a female always in danger of assault and battery.”

She was from upper-middle-class Massachusetts, the child of a university professor. A lot of those things she was “prohibited” from doing weren’t things each and every woman was prohibited from doing; they were things women of her class weren’t allowed to do. The daughters and sisters and wives of sailors and soldiers, women who worked in hotels and ran rooming houses, barmaids and sex workers, got to anonymously and invisibly observe those men, after all. They just couldn’t do it at the same time they tried to meet the standards educated Bostonians of the 1950s had for nice young women.

Failure to understand how diverse womanhood is has always been one of feminism’s biggest weaknesses. The Second Wave of feminism was started mostly by prosperous university-educated white women, since they were the people with the time and money and resources to write and read books and attend conferences about “women’s issues”. And they assumed that their issues were female issues. That they were the default of femaleness, and could assume every woman had roughly the same experience as them.

So, for example, middle-class white women in post-WWII USA were expected to stay home all the time and look after their children. Feminists concluded that this was isolating and oppressive, and they’d like the freedom to pursue lives, careers, and interests outside of the home. They vigorously pursued the right to be freed from their domestic and maternal duties.

But in their society, these experiences were not generally shared by Black and/or poor women, who, like their mothers, did not have the luxury of spending copious amounts of leisure time with their children; they had to work to earn enough money to survive on, which meant working on farms, in factories, or as cooks, maids, or nannies for rich white women who wanted the freedom to pursue lives outside the home. They tended to feel that they would like to have the option of staying home and playing with their babies all day.

This is not to say none of the first group enjoyed domestic lives, or that none of the second group wanted non-domestic careers; it’s just that the first group formed the face and the basic assumptions of feminism, and the second group struggled to get a seat at the table.

There’s this phenomenon called “cultural feminism” that’s an attitude that crops up among feminists from time to time (or grows on them, like fungus) that holds that women have a “feminine essence”, a quasi-spiritual “nature” that is deeply distinct from the “masculine essence” of men. This is one of the concepts powering lesbian separatism: the idea that because women are so fundamentally different from men, a society of all women will be fundamentally different in nature from a society that includes men.

But, well, the problem cultural feminism generally has is with how it achieves its definition of “female nature”. The view tends to be that women are kinder, more moral, more collectivist, more community-minded, and less prone to violence.

And cultural feminists tend to HATE people who believe in the social construction of gender, because we tend to cross our arms and go, “Nah, sis, that’s a frappe of misused statistics and The Angel In the House with some wishful thinking as a garnish. That’s how you feel about what womanhood is. It’s fair enough for you, but you’re trying to apply it to the entire human species. That’s got less intellectual rigor and sociological validity than my morning oatmeal.” Hence the radfem insistence that gender theorists like me SHUT UP and gender quite flatly DOESN’T EXIST. It’s a MADE-UP TERM, and people should STOP TALKING ABOUT IT. (And go back to taking about immutable, naturally-occuring phenomena, one supposes, like the banking system and Western literary canon.)

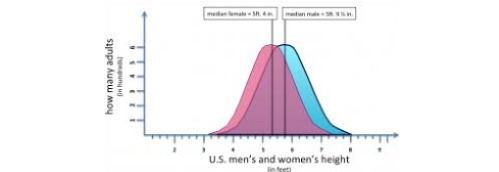

Because seriously, when you look at real actual women, you will see that some of us can be very selfish, while others are altruistic; some think being a woman means abhorring all violence forever, and others think being a woman means being willing to fight and die to protect the people you love. As groups men and women have different average levels of certain qualities, but it’s not like we don’t share a lot in common. The distribution of “male” and “female” traits doesn’t tend to mean two completely separate sets of characteristics; they tend to be more like two overlapping bell curves.

So, like I said, I grew up largely in rural, working-class Western Canadian society. My relatives tend to be tradesmen like carpenters, welders, or plumbers, or else ranchers and farmers. I was raised by a mother who came of age during the big push for Women’s Lib. So in the culture in which I was raised, it was very normal and in some ways rewarded (though in other ways punished) for women to have short hair, wear flannel and jeans, drive a big truck, play rough contact sports, use power tools, pitch in with farmwork, use guns, and drink beer. “Traditional femininity” was a fascinating foreign culture my grandmother aspired to, and I loved nonsense like polishing the silver (it’s a very satisfying pastime) but that was just another one of my weird hobbies, like sewing fairy clothes out of flower petals and collecting toy horses.

Within the standards of the society I was raised in, I am a decently feminine woman. I’m obviously not a “girly girl”, someone who wears makeup and dresses in ways that privilege beauty over practicality, but I have a long ponytail of hair and when I go to Mark’s Work Wearhouse, I shop in the women’s section. We know what “butch” is and I ain’t it.

But through my friendships and my career, I’ve gotten experiences among cultures you wouldn’t think would be too different–we’re all still white North Americans!–but which felt bizarre and alien, and ate away at the sense of self I’d grown up in. In the USA’s northeast, the people I met had the kind of access to communities with social clout, intellectual resources, and political power I hadn’t quite believed existed before I saw them. There really were people who knew politicians and potential employers socially before they ever had to apply to a job or ask for political assistance; there were people who really did propose projects to influential businessmen or academics at cocktail parties; they really did things like fundraise tens of thousands of dollars for a charity by asking fifty of their friends to donate, or start a business with a $2mil personal loan from a relative.

And in those societies, femininity was so different and so foreign. I’d grown up seeing femininity as a way of assigning tasks to get the work done; in these new circles, it was performative in a way that was entirely unique and astounding to me. A boss really would offer you a starting salary $10k higher than they might have if you wore high heels instead of flats. You really would be more likely to get a job if you wore makeup. And your ability to curate social connections in the halls of power really was influenced by how nice of a Christmas party you could throw. These women I met were being held, daily, to a standard of femininity higher than that performed by anyone in my 100 most immediate relatives.

So when girls from Seven Sisters schools talked about how for them, dressing how I dressed every day (jeans, boots, tee, button-up shirt, no makeup, no hair product) was “bucking gendered expectations” and “being unfeminine”, I began to feel totally unmoored. When I realized that I, who absolutely know only 5% as much about power tools and construction as my relatives in the trades, was more suited to take a hammer and wade in there than not just the “empowered” women but the self-professed “handy” men there, I didn’t know how to understand it. I felt like I was… a woman who knew how to do carpentry projects, not “totally butch” the way some people (approvingly) called me.

And, well, at home in Alberta I was generally seen as a sweet and gentle girl with an occasional stubborn streak or precocious moment, but apparently by the standards of Southern states like Georgia and Alabama I am like, 100x more blunt, assertive, and inconsiderate of men’s feelings than women typically feel they have to be.

And this is still all just US/Canadian white women.

And like I said, after years of this, I came home (from BC, where I encountered MORE OTHER weird and alien social constructs, though generally more around class and politics than gender) to Alberta, and I went to what is, for Alberta, a super hippy liberal church, and I helped prepare the after-service tea among women with unstyled hair and no makeup who wore jeans and sensible shoes, and listened to them talk about their work in municipal water management and ICU nursing, and it felt like something inside my chest slid back into place, because I understood myself as a woman again, and not some alien thing floating outside the expectations of the society I was in with a chestful of opinions no one around me would understand, suddenly all made sense again.

I mean, that’s by no means an endorsement for aspirational middle class rural Alberta as the ideal gender utopia. (Alberta is the Texas of Canada.) I just felt comfortable inside because it’s the culture where I found a definition of myself and my gender I could live with, because its boundaries of what’s considered “female” were broad enough to hold all the parts of me I felt like I needed to express. I have a lot of friends who grew up here, or in families like mine, and don’t feel at all happy with its gender boundaries. And even as I’m comfortable being a woman here, I still want to push and transform it, to make it even more feminist and politically left and decolonized.

TERFs try to claim that trans and nonbinary people reinforce the gender identity, but in my experience, it’s feminists who claim male and female are immutable and incompatible do that. It’s trans, nonbinary, and genderqueer people who, simply by performing their genders in public, make people realize just how bullshit innate theories of gender are.. Society is going to want to gender them in certain ways and involve them in certain dynamics (”Hey ladies, those fellas, amirite?”) and they’re going, “Nope. Not me. Cut it out.” I’ve seen a lot of cis people who will quietly admit they do think men and women are different because that’s just reality, watch someone they know transition, and suddenly go, “Oh my god, I get it now.”

Like yes, this is me being coldly political and thinking about people as examples to make a political point. Everyone’s valid and can do what they want, but some things are just easier for potential converts to wrap their minds around.. “I’m sorting through toys to give to Shelly’s baby. He probably won’t want a princess crown, huh?” “I actually know several people who were considered boys when they were babies and never got one, and are making up for all their lost princess crown time now as adults. You never know what he’ll be into when he grows up.” “…Okay, point. I’ll throw it in there.” Trans and enby people disrupt gender in a really powerful back-of-the-brain way where people suddenly see how much leeway there is between gender and sex.

I honestly believe supporting trans and enby people and queering gender until it’s a macrame project instead of a spectrum are how we’ll get to a gender-free utopia. I think cultural feminism is just the same old shit, inverted. (Confession: in my head, I pronounce “cultural” with emphasis on the “cult” part.)

I think feminism is like a lot of emergency response groups: Our job is to put ourselves out of a job. It’s not a good thing if gender discrimination is still prevalent and harmful 200 years from now! Obviously we’re not there yet and calls to pack it in and go home are overrated, but as the problem disappears into its solution, we have to accept that our old ways of looking at the world have to shift.

918 notes

·

View notes

Text

Variations on a Theme: "The Weird vs The Quantifiable" -- Aggregated Commentary from within the Gutenberg Galaxy

The pursuit of examining the world through philosophy, mathematics, and science tends to be seen as expanding the borders of what is known and quantified, conquering the territory of what is not yet known. In this pursuit, the investigator encounters wonder or the "weird", and what ideologically separates some philosophers and scientists from others is whether the investigator sets aside the weird as a misunderstood quirk of what is not yet known but still knowable, or the investigator takes into account the weird as a fundamental, permanent attribute of the landscape of inquiry that may perhaps always represent factors which intrinsically and inescapably evade knowledge and literary explanation, not as a bug of our understanding but as a feature of the true ontological state of affairs. The former mindset supposes that with more time and rigor, our inquiry will finally arrive at a sort of epistemological/ontological "bedrock" that dispels any sense of the bizarre, the latter treats scientific inquiry itself as necessitating the injection of a sort of subjective poetry or play to adequately do justice to the full reality of what is observed and described for our purposes, without ever expecting that we will hit such bedrock. Materialism/scientism perhaps would posit that any inclusion of the mystical or poetic in the language we use to describe the world is inappropriate, pseudo-scientific, pseudo-intellectual, or maladaptive; the mystic posits conversely that to exclude the poetic and not make room for the weird is maladaptive.

I have here a collection of excerpts from other thinkers that I think work together to allude to the mystical as a permanent fixture of our endeavors for clarification through experimentation and language, or at least suggest that a more "mystical" mindset will always be more useful than one that is conversely more in the vein of materialism/scientism trying to arrive at a "final technical vocabulary":

-------------------------------------

“We say the map is different from the territory. But what is the territory? Operationally, somebody went out with a retina or a measuring stick and made representations which were then put on paper. What is on the paper map is a representation of what was in the retinal representation of the man who made the map; and as you push the question back, what you find is an infinite regress, an infinite series of maps. The territory never gets in at all. […] Always, the process of representation will filter it out so that the mental world is only maps of maps, ad infinitum.” --Gregory Bateson, English anthropologist, social scientist, linguist, visual anthropologist, semiotician, and cyberneticist whose work intersected that of many other fields. His writings include Steps to an Ecology of Mind (1972) and Mind and Nature (1979). In Palo Alto, California, Bateson and colleagues developed the double-bind theory of schizophrenia. Bateson's interest in systems theory forms a thread running through his work. He was one of the original members of the core group of the Macy conferences in Cybernetics (1941- 1960), and the later set on Group Processes (1954 - 1960), where he represented the social and behavioral sciences; he was interested in the relationship of these fields to epistemology.

-------------------------------------