#orisa ifa

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Òrìṣàs play a significant role in the Ifá spiritual system, but are they gods, ancestors, or both?!

📺 Watch now: https://www.youtube.com/live/41b_CbaSF9E?si=kMMPQWCr4RjDNZTY

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I wanna take just a quick aside to gush about and promote my dear friend’s second book publication! I’ve known Ehime for something like 13 years now and I was so incredibly lucky to be part of her spiritual learning early on. I’m just so insanely proud of how far she’s come and how bright of a life she is, and I truly believe that anyone with any sort of interest in ancestor veneration and spiritual well-being would benefit so much from listening to what she has to say.

I really will try to keep religious stuff to my side blogs for the most part, but I was just so happy and excited about this that I wanted to share!

#ifa#orisa#you can’t imagine how proud I am of how far she’s come#from secretly studying divining and ancestral spirituality with me after school#to reading excerpts from her new book at a massively popular venue on Broadway in NYC#i think I lost a lot of having a ‘normal’ young adulthood to my spiritual work taking up so much of my life#but I’m so glad it did really#because of it I was able to be part of some really amazing peoples’ lives#at a time when I think it made a difference 💜#personal stuff#spirituality

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

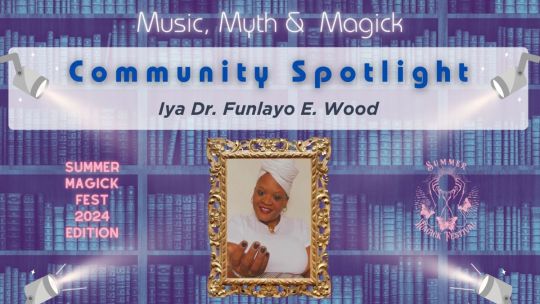

Community Spotlight: Iya Dr. Funlayo E. Wood

Summer Magick Fest 2024 is right around the corner… and that means we’re coming to a close with this series. It’s been quite a journey, hasn’t it? Today, I’m going to introduce you to Iya Funlayo E. Wood, PhD… but just in case you missed one of the earlier articles, they’re all centering around the talented teachers and presenters that will be headlining at SMF 2024, including: Ivo Dominguez,…

View On WordPress

#festival#headliners#ifa#iya funlayo#lucumi#lukumi#magick#occult#orisa#orisha#pagan#summer magick#summer magick fest#witch

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yay epistemic regress problems

Aside from the epistemic significance of this dialogue I find that Socrates’ description of innate knowledge via the soul’s experience to mirror the concept of destiny and being a reborn ancestor in Ifa.

#black dark academia#dark academia#noir library#poc dark academia#socrates#meno’s paradox#philosophy#epistemology#Ifa#isese#orisa

0 notes

Text

instagram

#reviews#tarot#tarot cards#tarot reading#psychic#psychic readings#etsy#etsyseller#vodou#santeria#ifa#vodun#orisa#Instagram

0 notes

Text

https://www.instagram.com/reel/Cxy8yPfo7NX/?igshid=MTc4MmM1YmI2Ng==

0 notes

Text

BIG PAPA / THE DOORKEEPER

[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8]

REAL WORLD INSPIRATION

Pictured: “Papa La Bas”

The real-world counterpart of Big Papa / The Doorkeeper is Papa Legba of Louisiana Voudou, who is also called “Papa La Bas”, “Papa Lébat”, or “Papa Liba”. The character is inspired by the theory that the Hoodoo Spirit at the Crossroads is actually “Papa La Bas”.

Legba is one of the most important vodun. He is universally worshipped and appears everywhere there is Vodu, including West African Vodun, Haitian Vodou, and Louisiana Voudou. Although they share a common origin, the way Legba is described and worshiped varies by tradition. So not to confuse their traits, I will henceforth refer to the West African vodun as Legba, the Haitian lwa as Papa Legba, and the Louisiana spirit as Papa Liba.

Pictured: Eshu staff of wood, leather and cowrie shells. (Yoruba)

There is some controversy regarding the origins of Papa Liba, where some claim he originates in the Yoruba, while others claim he originates in the Ewe people[1]. At minimum, Papa Liba shares a common origin with the Yoruba divination system Ifa. Inseparable from Ifa is Esu, one of the most important of the major orisa in the Yoruba pantheon.

Although he is described as the “divine trickster”, there is far more to Esu than his so-called “tricks”[2]. Funso Aiyejina describes him in the following terms[3]:

“In Yoruba philosophy, Esu emerges as a divine trickster, a disguise-artist, a mischief-maker, a rebel, a challenger of orthodoxy, a shape-shifter, and an enforcer deity. Esu is the keeper of the divine ase with which Olodumare created the universe; a neutral force who controls both the benevolent and the malevolent supernatural powers; he is the guardian of Orunmila’s oracular utterances. Without Esu to open the portals to the past and the future, Orunmila, the divination deity would be blind. As a neutral force, he straddles all realms and acts as an essential factor in any attempt to resolve the conflicts between contrasting but coterminous forces in the world. Although he is sometimes portrayed as whimsical, Esu is actually devoid of all emotions. He supports only those who perform prescribed sacrifices and act in conformity with the moral laws of the universe as laid down by Olodumare. As the deity of the “orita”—often defined as the crossroads but really a complex term that also refers to the front yard of a house, or the gateway to the various bodily orifices—it is Esu’s duty to take sacrifices to target-deities. Without his intervention, the Yoruba people believe, no sacrifice, no matter how sumptuous, will be efficacious. Philosophically speaking, Esu is the deity of choice and free will. So, while Ogun may be the deity of war and creativity and Orunmila the deity of wisdom, Esu is the deity of prescience, imagination, and criticism—literary or otherwise.”

Ayodele Ogundipẹ describes Esu like so[4]:

“Èṣù…is the messenger of the gods, the mediator between God and humans between order and chaos, sin and punishment, life and death, fate and accident, certainty and uncertainty. It is no wonder then, that Èṣù in myth knows no master, that he is male and female, that he is tall and short, kind and cruel, an elderly deity of youth who lives at the crossroads.”

While he is often figured as being small and dark-skinned, Esu is a shape-shifter who can assume hundreds of different forms. One of the forms Esu assumes is that of an “old man at the crossroads”, where he is envisioned smoking a pipe[5]. In one account, he is described as lively and loving to dance[6]; in another, he is described as limping “because he keeps one [leg] anchored in the realm of the gods while the other rests in this, our human world.”[7]

Ogundipẹ records the following folk songs for Esu[8]:

Odara o jeyeye o

E ma f' Agbunwa sire

Esu o ma fe yeye o

E ma f'Agbunwa sire

E ma f'oro Esu se yeye

Se yeye o

E ma f'Agbunwa sire

Esu o ma fe yeye o

Fe yeye o

E ma f'Agbunwa sire.

Odara is no laughing matter

Do not mock the shrewd one

Esu abhors levity

Do not deride the crafty one

Do not jeer at anything concerning Esu

Or sneer at him

Do not ridicule the ingenious one

Esu does not tolerate mockery.

Esu gbere naa wa o

Esu o!

Gbere naa wa ko mi o

Esu o!

Ba mi wa iyawo o

Esu o!

Ma je ori mi o baje o

Esu o!

Ma jee ile mi o daru

Esu o!

Esu brings good luck

Oh! Esu!

Bring good luck to me

Oh! Esu!

Find me a wife

Oh! Esu!

Do not spoil my good fortune

Oh! Esu!

Do not bring disruption into my house

Oh! Esu!

Across the West African diaspora, there exists a collection of divine “tricksters”, including Esu, Legba, Elegua, and their many derivatives. While these divinities are considered different from each other, they can be grouped together because of their common origin with Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára.

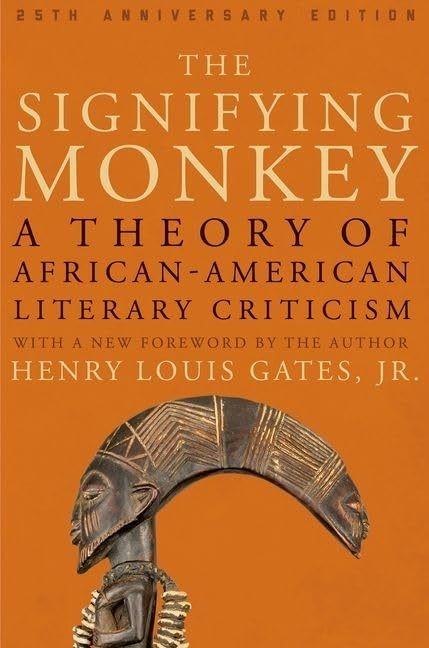

Henry Louis Gates Jr. proposed the concept of an “Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára collective” in The Signifying Monkey (1988)[9]:

"Of the music, myths, and forms of performance that the African brought to the Western Hemisphere, I wish to discuss one specific trickster figure that recurs with startling frequency in black mythology in Africa, the Caribbean, and South America... This topos that recurs throughout black oral narrative traditions and contains a primal scene of instruction for the act of interpretation is that of the divine trickster figure of Yoruba mythology, Esu-Elegbara. This curious figure is called Esu-Elegbara in Nigeria and Legba among the Fon in Benin. His New World figurations include Exú in Brazil, Echu-Elegua in Cuba, Papa Legba…in the pantheon of the loa of Vaudou of Haiti, and Papa La Bas in the loa of Hoodoo in the United States. Because I see these individual tricksters as related parts of a larger, unified figure, I shall refer to them collectively as Esu, or as Esu-Elegbara. These variations on Esu-Elegbara speak eloquently of an unbroken arc of metaphysical presupposition and a pattern of figuration shared through time and space among certain black cultures in West Africa, South America, the Caribbean, and the United States. These trickster figures, all aspects or topoi of Esu, are fundamental, divine terms of mediation: as tricksters they are mediators, and their mediations are tricks. If the Dixie Pike leads straight to Guinea, then Esu-Elegbara presides over its liminal crossroads, a sensory threshold barely perceptible without access to the vernacular, a word taken from the Latin vernaculus ("native"), taken in turn from verna ("slave born in his master's house").”

Pictured: Legba Dancers (Dahomey)

According to some accounts, the kingdom of Dahomey borrowed from the Yoruba pantheon, just as the Romans borrowed from the Greek pantheon. Ifa became known as Fa, and the babalawo became known as bokono[10]. Regardless of whether he originates in the Yoruba or the Ewe people, the vodun Legba is a counterpart to the orisa Esu, where Legba presides over the crossroads[11] and is closely associated with Fa – “the destiny of the Universe as willed by the gods”[12].

Described as “the divinity of the unpredictable, the unattributable”, Legba is a guardian, mediator, messenger, and intermediary amongst the vodun[13]. In Dahomean mythology, Legba is the Seventh and Youngest Child of the Creator, Mawu-Lisa[14]. Each of the Seven Children inherited a domain of the universe from Mawu-Lisa except Legba, who received no inheritance. This is why he is sometimes likened to a “beggar” and described as capricious or jealous[15]. In reality, Legba turns his destitution and into the most desirable role, where he is allowed to freely travel and communicate with each domain: “Legbá, not being tied to a specific domain, will make his apparent poverty a sign of real wealth.”[16]

While emphasizing his ambiguous and multivocal nature, Honorat Aguessy characterizes Legba him like so[17]:

“...Legbá, messenger of the vodun, is always invoked before those to whom he must deliver the message. In the same order of ideas, he receives offerings and libations before all other divinities. According to the interpretations or justifications that certain native specialists of the myths give to these practices and rituals, the aim is to destroy the possible machinations of Legbá and to appease his unpredictable anger. Indeed, one of the phrases used to characterize the characterless character that is Legbá is the following: - Agbo hanyan hanyan gba! or "Agbo, around him is disorder!" And so, the messenger and interpreter of the divine sphere is more feared and respected than all the other divinities…”

He goes on to describe Legba as “a comedian”, “a tempter”, and “a miracle worker”, noting that[18]: “...Lègba does not act with violence; cunning is what characterizes him. He is the one who is neither good nor bad, but seeks to break down the barrier between two distinct orders…”

Hippolyte Brice Sogbossi emphasizes Legba’s roles as “the tempter who saves, the omniscient being, the mediator, the beggar, the miracle worker”, noting that “the principle of Legba seems to be to save the victims of the established norm.”

He writes[19]:

“…the myth of Lègba reflects a constant rebellion and a corrosive irony of the established authority. Far from being a guarantee, it represents a permanent threat to the reigning order that condemns it to endless changes…”

There are many similarities between Legba and Esu, but the two differ in their mythology. Unlike Esu, the vodún Legba is associated with the dog - “the animal is sacred to him” [20]. Legba also has a different origin myth from Esu, where he was made chief of the gods for his mastery over musical instruments[21]:

HOW LEGBA BECAME CHIEF OF THE GODS…

Long ago, Legba was the last of the gods. One day Mawu said to the gods he would show them something. He would show them who would be their chief. Mawu then gave them a gong, a bell, a drum, a flute, and said to whoever took all the instruments, and played the four together and also danced to them would be their chief.

Hevioso said, "I am very strong. I can do all." So he tried. But he failed.

Mawu called on Gu and Age to try. Age said, "I am a hunter. I have great strength. I can do everything." He tried and failed. Gu came. He said he had much strength. He had fire. He made many things. He would do it. He tried, and he, too, failed.

Now Mawu called all the gods together and asked Legba to try. Legba tried and did all. He struck the drum; he played the gong; he rang the bell; he blew into the flute, and [at the same time] made all gestures of the dance. Mawu said to him, "Now I will give you a woman whose name is Konikoni." And Mawu said to the other gods that Legba was to be the first among them.

Now Legba said he would sing, and he sang

If the house is peaceful

If the field is fertile,

I will be very happy…

For this reason, Legba is associated with music and dancing: “...when someone beats the drum for Legba, he comes and he dances joyously.”[22]

Pictured: Lègba, by Cyprien Tokoudagba

Dahomean mythology includes one of the most interesting myths centered around a divine “trickster”, where it is revealed that Legba’s “trickery” results from him being the original victim of injustice. At the beginning of time, Legba was not a “trickster”, but a saintly being who was loyal and obedient to his Creator. The God/dess took advantage of his good nature, causing him to become demonized and hated by all. In response to this injustice, he successfully rebels against his Creator, becoming the divine “trickster”[23][24]:

WHY TRICKSTER HAS A BAD NAME: CREATOR TRICKED: WHY THE SKY IS HIGH

Legba did good towards everybody, and he was always with Mawu. When he did a good deed, people always went to thank Mawu. Now Legba said to Mawu, "What you tell me to do, I do, and no one says thank you to me."

Now, it is said in those days Legba did nothing without instructions from Mawu. But when there was evil, and the people cried out and went directly to Mawu, Mawu said to them, "It was Legba who did that." All the people began to hate Legba.

One night Legba went to see Mawu to ask her why when there was evil, she called his name? Mawu said to him that in a country it was necessary that the master be known as good, and that his servants be known as evil. Legba said, "Very well."

Mawu has a garden in which she planted yams. Legba went to tell her that thieves were planning to go to that garden to gather all the yams and divide them. So Mawu assembled all the people of her kingdom to say to them that the first one who went to steal in this garden would be killed.

That night rain fell. Legba passed behind Mawu's house and stole her sandals. He put on Mawu's sandals and went into the garden. He stole all the yams. In the morning the theft was discovered. At once Legba said all the people must be assembled to see whose feet those were. All the people came. They measured the feet. But they did not find a foot to match the footprints in the garden. Now Legba said, "Ah, is it possible that Mawu herself came at night and has forgotten it?" Mawu said, "What, I? That's why I do not like you, Legba. I will measure my foot with that footprint." Mawu put her foot down. It was exactly the footprint.

Now everybody shouted, "There is an owner who is herself the thief." Mawu was humiliated. She said to all the people that it was her own son who had played her this trick. Now, she would go up above, and leave the earth, and every night Legba would come to her to give her an account. Until then Mawu was on earth. Mawu now went up towards the sky.

It is said that in those days the sky was quite near, only about two meters from the earth. Now, when Legba committed a fault, Mawu saw him and reproached him. Now, Legba was irritated by this, so he went to conspire with an old woman. He told the old woman to throw water at the place where Mawu was, two meters from the earth. The old woman, after washing her plates and pots, threw the dirty water where Mawu was. Mawu was angered. She said, "To stay here is troublesome. It is necessary to go farther away." And so Mawu departed from here on high, and left Legba here on earth.

This, along with many other myths, perfectly captures Legba’s cunning and resistance to established authority. Unlike Lucifer, Legba’s rebellion is justified. He is not cast out of Heaven, but holds an extremely important and enviable role in the court of the Creator, Mawu-Lisa.

“AGBO HANYAN HANYAN GBA!” (AGBO, AROUND HIM IS DISORDER!)

There are many other myths that dramatize Legba’s hypersexual nature. Sadly, these tend to receive excessive focus, while the most important aspects of this vodun are overlooked.

A necessary critique comes from Ayodele Ogundipẹ[25]:

It is mystifying that the Herskovitses, who have done so much to bring out the complexity of Legba's personality and the Dahomean world view, should be the very ones to foster Legba's misconception as a simple trickster deity. Legba's sexuality, grossness, and trickster-like nature are emphasized to the detriment of his more meaningful and significant position as a link and linguist between humans and the supernatural world. It is difficult to agree with Melville Herskovits when he writes that Legba is essentially a trickster, for in the same work he states, 'In this world ruled by Destiny man lives secure in the conviction that between the inexorable fate laid down for an individual and the execution of fate lies the possibility a way out, Legba' (1938, 2: 229-30)

Legba is many things to the Dahomeans, in the same way that Jesus Christ is many things to Christians. But although some people see Jesus Christ as a superstar or a miracle-worker, His essential function in Christian theology is His redemptive function. Although Jesus Christ did perform miracles and led a dramatic life, His primary significance for Christians is that He is considered the Son of God who gave His life on the cross in order to save the world. In the same way, the essence of Legba's being and of his place in the Dahomean pantheon is his ability to intervene in humanity's fate, in spite of his trickster qualities that are dramatized in myth.

Indeed, Herskovits’ crucial analysis of Legba’s complexity is not found in the individual myths, but the description found at the beginning of Dahomean Narrative, titled “Myth (hwenoho)”.

Some key excerpts[26]:

...[Legba] is a figure of the greatest importance both in the generalized form in which he participates in the worship of the vodun pantheons, and more particularly as guardian of entrances to villages, to markets, to shrines, compounds, and houses, until he is brought into the closes association of all - with a man's personal destiny (his Fa)...

…It is perhaps the trait of not being cowed by those in power, more than any other, that endears Legba to the Dahomean, whose political patterns are so firmly founded on the exercise of authority and obedience to its decrees. In his defiance, he does not ask for pity. He will not openly show the hurt of punishment. He is no Job to cry out in agony. He turns the perversities of his own nature into a reproach against Mawu herself.

We have here the key to the absence of the tragic theme in Dahomean narrative. The Dahomean world-view dictates the mask of insensitiveness in the face of trials. To reveal one's suffering to a hostile force, superhuman or human, is to invite more recrimination... Since Legba will not accept injustice without protest, not even injustice at the hands of his parent, the Creator, he uses his wits to humiliate Mawu before the multitude…

…In these stories we see the experience of deprivation and humiliation transmuted into affirmation on the theme of "The last shall be first."...Legba, that is, alone of all the children of Mawu, has no domain of his own. He is a wanderer from one kingdom of the gods to another, and from these to the world of men, and to the kingdom of Death. He is deformed and ill-favored. Yet by his astuteness, imagination, and wit, he has succeeded in creating for himself a role of the most universally worshipped, of the first to be propitiated, of the one who can take all women. The satisfactions his tales bring the Dahomean are self-evident, they arise out of identifications that transcend Dahomey.

Mama Zogbé summarized Legba, like so[27][28]:

In the Mami Wata Yeveh Vodoun tradition, this “spiritual linguist’ and “traffic guard,” and best friend of the Bokono and vodoun is known as “Legba,” the youngest and most favorite child (once also known as brother) of Ma-wu. Legba can be either male or female. However, universally, under African patriarchy, the male is emphasized.

Legba can for a price, (usually monetary or sacrifice) correctly direct, interpret and transmits all incoming and outgoing messages being sent on the divine information highway for the Bokono on behalf of the client.

Legba, the grandmaster of Atiké(herbs/gris-gris-medi-cine) and keeper of the sacred mysteries regarding human and divine affairs, is known universally as the “trickster,” meaning that he has been appointed by his Mother to transcend “moral” law in order to expose the weaknesses inherent within the human heart and character. Often demonized by Christians as “a devil,” Legba is anything but that. Being allowed to transcend “moral law” allows Legba to force humans to concede their shortcomings, and to take the necessary steps to correct them. This affords the individual the opportunity to complete their assigned Kpoli (destiny) on Earth, thus, bringing them closer to God/dess in the process.

Pictured: Artistic Rendition of the Haitian lwa Papa Legba

The orisa and vodún were transmitted to the New World via the transatlantic slave trade, where they continued to undergo transformations.

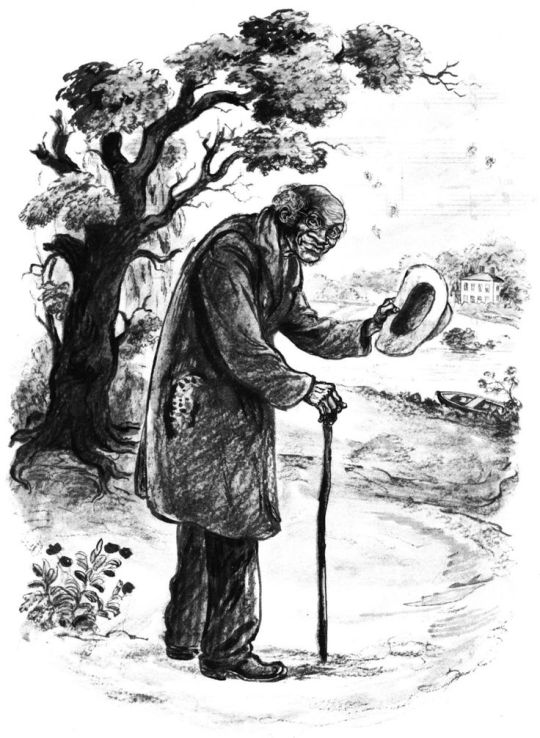

In Haiti, the lwa Papa Legba (Legba Atibon) maintains his important role as the one who “opens the gates” to the other lwa[29]. Milo Marcelin described him like so[30]:

“Papa Legba ou Atibon-Legba est le dieu des portes, le maître des carrefours et des croisées de chemins et le protecteur des maisons. En vertu de ces différentes fonctions, il est invoqué sous les noms de « Legba-nan- bayè » (Legba des barrières), de « Legba-calfou » (Legba des carrefours) ou « Grand chemin », de « Legba Mait' bitation » ou « Legba Maiť habitation ». En tant que dieu qui sait toutes choses, il porte l'épithète d'Avadra...”

“On se le représente sous les traits d'un vieillard, cassé par l'âge, à demi paralysé, qui s'avance péniblement avec l'aide d'une canne ou d'une béquille. Le nom de Legba-pied-cassé, qui lui est parfois donné, traduit bien l'aspect pitoyable sous lequel on se l'imagine. Legba est coiffé d'un chapeau de paille à large bord, il porte une macoutte (sacoche en feuilles de latanier) et i fume sans arrêt une longue pipe en terre cuite. Son grand chapeau lui permet de protéger les loa de Guinée (d'Afrique) contre les ardeurs du soleil…”

TRANSLATION:

“Papa Legba or Atibon-Legba is the god of doors, the master of crossroads and the protector of houses. By virtue of these different functions, he is invoke under the names of “Legba-nan- bayè” (Legba of the Barriers), “Legba-calfou” (Legba of the Crossroads) or “Grand chemin”, “Legba Mait’ bitation” or “Legba Mait’ habitation”. As the god who knows all things, he bears the epithet of “Avadra”...”

“He is represented as an old man, broken by age, half-paralyzed, who hobbles with the aid of a cane or crutch. The name Legba-pied-cassé, which is sometimes given to him, translates well the pitiful appearance in which he is imagined. Legba dons a large-brimmed straw hat, he carries a macoutte (palm leaf sack) and he endlessly smokes a long, terracotta pipe. His large hat lets him protect the loa from Guinea (Africa) from the heat of the sun…”

According to Marcelin, Papa Legba was identified with St. Anthony, St. Peter, and St. Lazarus[30].

Vodouwizan call upon Papa Legba to “open the gates” at the beginning of ceremony[30]:

youtube

Legba

Atibon Legba, l'ouvri bayè pou moin, agoé!

Papa Legba, l'ouvri bayè pou moin,

Pou moin passer!

Lo m'a tounin, m' salué loa-yo.

Vodou Legba, l'ouvri bayè pou moin,

Pou moin ça rentrer!

Lo m'a tounin, m'a remercié loa-yo. Abobo.

Atibon-Legba, ouvre-moi la barrière, agoé!

Papa Legba, ouvre-moi la barrière,

Pour que je passe.

Lorsque je retournerai, je saluerai les loa.

Vodou Legba, ouvre-moi la barrière,

Pour que je rentre.

Lorsque je retournerai, je remercierai les loa. Abobo.

Atibon Legba, open the gates for me, agoé!

Papa Legba, open the gates for me,

So I may pass!

When I return, I will greet the loa.

Vodun Legba, open the gates for me,

So I may enter!

When I return, I will thank the loa. Abobo.

Pictured: Papa Legba, by Andre Pierre

Due to his essential role as spiritual gatekeeper, there are many praise songs for Papa Legba.

Twa Pwen (Racine Barak) [31]

Legba anye o, Legba o anye o!

Legba anye o, m pral pare solèy.

Peyi anmwe, Legba, m pral pare solèy.

Peyi anmwe! O Bondye chay!

Atibon, m pral pare solèy!

Oh yeah Legba, oh yeah Legba!

Oh yeah Legba, I will be ready for the sun.

The country needs help, Legba, I will be ready for the sun.

The country needs help! Oh God the load!

Atibon, I will be ready for the sun!

More songs can be found in: Hebblethwaite, Benjamin, and Bartley, Joanne. Vodou Songs in Haitian Creole and English. Ukraine, Temple University Press, 2012.

Pictured: St. Peter, with whom Papa Liba was identified.

Following the Haitian Revolution, a large number of Haitians fled to the city of New Orleans[32]. With them, they brought their religious practices, which merged with the religious practices that were already present in the City to form Louisiana Voudou.

Of the divinities that appear in the historical record of Louisiana Voudou, Papa Liba (“La Bas”) appears with great frequency[33]. As in Dahomey and Haiti, he seems to have been one of the most important spirits worshiped at this time, where “Oldtime Voodoos always talked about Papa La Bas”[34].

Much like his Haitian counterpart, Papa Liba was identified with St. Peter, and a similar song was sung asking him to “open the door” (“l'ouvri bayè”)[35]:

“Marie Laveau…even taught her a Voodoo song. It went like this:

St. Peter, St. Peter, open the door, I’m callin’ you, come to me! St. Peter, St. Peter, open the door …

“That’s all I can remember. Marie Laveau used to call St. Peter somethin’ like ‘Laba.’ She called St. Michael ‘Daniel Blanc,’ and St. Anthony ‘Yon Sue.’”

Papa Liba persisted long past Marie Laveau’s time, into the 20th Century. In 1936, “Hoodoo Queen” Madame Ducoyielle called upon Papa Liba with the following chant[36]:

Labat ouvre la port…Go spirits, open the way for us. Pass before us!

Pictured: “The Man at the Crossroads”

It is during this time period that another spirit appears in the history of Hoodoo: the so-called “Devil at the Crossroads”.Traveling through the American South during the early 20th Century, Henry Middleton Hyatt recorded dozens of accounts of this “Devil” figure. These were compiled into a collection called “SELL SELF TO THE DEVIL”, which can be found in Volumes 1 and 5 of Harry Middleton Hyatt’s Hoodoo, Conjuration, Witchcraft & Rootwork:

Hyatt, Harry Middleton. Hoodoo - Conjuration - Witchcraft - Rootwork, Vol. 1. United States, Western Publishing Company, 1970, pp. 97-111. https://archive.org/details/harry-middleton-hyatt-hoodoo-conjuration-witchcraft-rootwork-vols-1-5/HARRY%20MIDDLETON%20HYATT%20-%20Hoodoo%2C%20Conjuration%2C%20Witchcraft%20%26%20Rootwork%20Vo%201/page/97/mode/2up?

Hyatt, Harry Middleton. Hoodoo - Conjuration - Witchcraft - Rootwork, Vol. 5. United States, Western Publishing Company, 1978, pp. 4003-4013. https://archive.org/details/harry-middleton-hyatt-hoodoo-conjuration-witchcraft-rootwork-vols-1-5/HARRY%20MIDDLETON%20HYATT%20-%20Hoodoo%2C%20Conjuration%2C%20Witchcraft%20%26%20Rootwork%20Vo%205/page/4002/mode/2up?

This “Devil” is associated with the crossroads or forks in the road, where he often manifests there. He makes deals with humans, where he teaches them “tricks” or grants them some sort of talent in exchange for their soul. Many if not most of these deals involve music, with a dedicated subsection titled “DIABOLIC MUSIC”. Although he is sometimes referred to as the “black man” or “de Ole man”, his appearance varies and is often omitted from the description. The extent to which he is frightening or forgiving also varies. In several of these accounts, he is similar to Luisa Teish’s description of the African American “devil”, where he is a “trickster” or a “a funny-looking creature” instead of Satan[37].

The most famous example of these “deals with the devil” is the legendary bluesman Robert Johnson – a guitarist so ahead of his time, he is rumored to have “sold his soul to the devil” in exchange for musical genius.

In the present day, this spirit is no longer called “Devil”, but “The Man” or “Spirit at the Crossroads”. Descriptions of his appearance vary, but he is frequently described as a “big old black man” with the appearance of a “beggar”[38].

There is a popular theory that the “Man at the Crossroads” is actually Papa Liba, or is related to him because he is also “part” of the Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára collective[39].

The various “parts” of the Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára were demonized by Christian missionaries, causing him to be associated with Satan. An early example of this can be found in the writings of Alfred Burton Ellis, who likened Esu to “a personification of evil.”[40] This misidentification became so strong that the word the word “Devil” came to be translated as “Esu” in the Yoruba language.

Ayodele Ogundipẹ explains the error in describing Esu – the divine messenger and mediator of the orisa – as “Devil”[41]:

"Yoruba religion dictates a doctrine of the absolute and unfathomable goodness of God and the universe. There is no recognition of the existence of absolute evil or a supreme evil spirit in contradiction to the infinite goodness of God and the incomprehensible order of the universe…Everything - every thought and every action - is believed by the Yoruba to have its place in God's Grand Design, even though man may not always understand what that place is… Therefore, although there are unpleasant or undesirable elements about Esu, he is not the supreme evil deity or spirit, nor is he a totally negative force. He is not against human beings and their joys for the sake of being contrary. He does not harm human beings at will, although he can if wants to. His job is to discipline those who offend Olorun, neglect the orisa, and flout social laws and customs. He is particularly against those who deny any sacrifice needed to keep humans in harmony with the deities and with God.”

Melville Herskovits describes how the vodún Legba was similarly demonized, where his name was also translated as “Devil” by Christian missionaries[42]: "It has been conjectured that the Christian missions, by identifying Legba with the Devil, have helped to make him an especially popular figure in Dahomean lore. Intensive study of the Dahomean world-view however, leads us to conclude that this identification has served rather to emphasize his popularity than to initiate a new attitude toward him...”

As explained by Mama Zogbé, Legba is “anything but” Satan[27][43]:

As messenger of the gods, and possessor of the Fate and Destiny of humans, Legba garners the most political and spiritually powerful position, and thus, the most envious place in the Mami Wata Vodou pantheon. When he is appeased, he will transmit the messages of the gods clearly. If offended, or if the person’s character is corrupted, “evil,” or is avoiding some major responsibility, Legba (or she) might mistranslate an important message, thereby reeking havoc, misery and even doom for the receiver, family or the nation. For this reason, Legba is known to be the instigator of wars, accidents, arguments, and general overall distension; especially if not appeased or is forgotten about during ceremonial ritual. For this reason Legba has often been misequated with the Christian “Satan,” However the two are as diametrically different in both function, and cosmic design as two principle forces can be described.

Legba as the master of human suffering might bring about sudden misfortune and conflict. However, it is specific and serves to diminish the ego, and humble the human character. As the representative of Ma-wu, his ultimate goal is never the complete ruin and destruction of humans, whereas Satan’s primary and absolute objective is towards total human annihilation, motivated purely by evil and maliciousness intent.

What is important to understand here is, that it is Legba who caters in the exclusive role as the one who delivers the messages for the gods, and is the revealer of ones Kpoli (destiny, purpose in life), as related to him by Gabadu. Further, that it is the role of an initiated, trained, gifted and very skilled Bokono/Bokovi/Afavi to accurately reveal this information to the client, and perform the necessary “vo” sacrifices (for Legba) on their behalf.

Sadly, the association between Legba and “Devil” persisted in America. Evidence of this comes from interviews of the Federal Writer’s Project, which can be found in Robert Tallant’s (1984) Voodoo in New Orleans.

One of these interviews involves Alexander Augustin, described by Noël Mellick Voltz as a “former free person of color”, “an old mulatto”, and a “spiritualist”[34]:

“Alexander Augustin remembered some of the tales of old people which dated to the era of the Widow Paris.

They would thank St. John for not meddlin’ wit’ the powers the devil gave ’em,” he said. “They had one funny way of doin’ this when they all stood up to their knees in the water and threw food in the middle of ’em. You see, they always stood in a big circle. Then they would hold hands and sing. The food was for Papa La Bas, who was the devil. Oldtime Voodoos always talked about Papa La Bas. I heard lots about the Maison Blanche. It was painted white and was built right near the water wit’ bushes all around it so nobody couldn’t see it from the road. It was a kind of hoodoo headquarters.”

A second interview involves Josephine McDuffy (“Josephine Green”), an 87-year old woman described by Jeffrey E. Anderson as a “former slave”[44]:

Josephine Green, an octogenarian, recalled her mother’s stories about Marie Laveau.

“My ma seen her,” Josephine boasted. “It was back before the war what they had here wit’ the Northerners. My ma heard a noise on Frenchman Street where she lived at and she start to go outside. Her pa say, ‘Where you goin’? Stay in the house!’ She say, ‘Marie Laveau is comin’ and I gotta see her.’ She went outside and here come Marie Laveau wit’ a big crowd of people followin’ her. My ma say that woman used to strut like she owned the city, and she was tall and good-lookin’ and wore her hair hangin’ down her back. She looked just like a Indian or one of them gypsy ladies. She wore big full skirts and lots of jewelry hangin’ all over her. All the people wit’ her was hollerin’ and screamin’, ‘We is goin’ to see Papa Limba! We is goin’ to see Papa Limba!’ My grandpa go runnin’ after my ma then, yellin’ at her, ‘You come on in here, Eunice! Don’t you know Papa Limba is the devil?’ But after that my ma find out Papa Limba meant St. Peter, and her pa was jest foolin’ her.”

Indeed, the name Legba seems to have been forgotten in America by the 20th Century. With some variation, he was most frequently called “Papa La Bas” (“Labat”, “Laba”, etc…), as a likely reference to Satan[45]. Within a Christian context, this carries the most negative of connotations, but it is possible that African-Americans identified Legba with “Devil” as a means of preserving their spiritual practices under the oppression of religious persecution. Similar to Herskovits’ description, Luisah Teish describes how American Africans viewed the “Devil” as more of a “trickster” figure, instead of the embodiment of evil[37]:

“...Christian missionaries’ fear and lack of comprehension of the African religious view caused them to identify the African trickster as the devil. This confusion made it easy to label all African-based religion as “evil.” In the Black U.S. South, however, the “devil” is seen as little more than an impish child who tempts the pious into wrong action, or a funny-looking creature like the SaSabonsam...”

“...Louisiana Blacks were able to maintain Papa La Bas the Trickster (Legba) as the Christian devil with a humorous touch; the importance of elders, funerals, and ancestors in suppressed forms; divination through the reading of natural phenomena (the signs); natural magic and healing with the curing herbs of the swampland…”

African-Americans may have called him “La Bas” not to demonize him, but to ensure that he would not be forgotten.

Although there are connections between Papa Liba and the Hoodoo Spirit at the Crossroads, this is merely a theory, and it is a contested one. Some people in the Hoodoo community think there might be a connection, but others insist there is no connection. Some of the lwa are incorporated into Hoodoo of New Orleans, but their traditions are distinct from Haitian Vodou, where the lwa are not worshiped themselves but play an important role in ancestor veneration.

For a lengthy discussion of this topic, see: https://www.youtube.com/live/5UfG9BbcqE8

In addition to blues, “Papa La Bas” is also connected to jazz. In his analysis of Ishmael Reed’s (1972) Mumbo Jumbo, Henry Louis Gates Jr. writes[46]:

“...[Pa Pa La Bas] is the chief detective in hard and fast pursuit of both Jes Grew and its text. Pa Pa La Bas's name is a conflation of two of the several names of Esu, our Pan-African trickster. Called Papa Legba as his Haitian honorific and invoked through the phrase "eh la-bas" in New Orleans jazz recordings of the 1920s and 1930s, Pa Pa La Bas is the Afro-American trickster figure from black sacred tradition. His surname, of course, is French for "down" or "over there," and his presence unites "over there" (Africa) with "right here." He is indeed the messenger of the gods, the divine PanAfrican interpreter, pursuing, in the language of the text, "The Work," which is not only Vaudou but also the very work (and play) of art itself…”

youtube

Eh La Bas!

E la ba! (E la ba!)

E la ba! (E la ba!)

E la ba, chèri! (E la ba, chèri!)

Komon sa va? (Komon sa va?)

E la ba! (E la ba!)

E la ba! (E la ba!)

E la ba, chèri! (E la ba, chèri!)

Komon sa va? (Komon sa va?)

A collection of songs from Louisiana Voudou can be found in: Anderson, Jeffrey E.. Voodoo: An African American Religion. United States, LSU Press, 2024.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Many people are confused about this Ifá teaching… 🤔 One of the most common misconceptions is whether a person has one or two head Orisa. But Ifá provides a clear answer—are you sure you know the truth?

▶️ Watch now to find out! ⬇️ 🔗 https://www.youtube.com/live/41b_CbaSF9E?si=n3fbx0bu1uVXoviM

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Osun sought to improve

her life, she went to consult Ifa. The awo advised her to

sacrifice. Osun complied. But still, her life wasn't complete.

Something was missing. So she returned to the babalawo for

clarification. The awo advised Osun not to worry. Her sacrifice

was accepted. All she needed to do was practice sacred

service and everything else would come together. Again, Osun

complied. She began to devote her life to spiritual service,

tending to the needy, treating the sick and uplifting the

powerless. All blessings then manifested in her life. Osun found

complete fulfillment. Ritual and ceremony alone are not enough

to heal your life. Olodumare has blessed you with great power

and purpose. Like Osun, you too must augment your rituals

with sacred service. In the Orisa Lifestyle Academy, you can

practice self discovery, spiritual devotion and sacred

#spirit work#afrodiaspores#ifa in usa#witches#traditional#isese#reading#astrology#traditional witchcraft#ifa

0 notes

Text

Muchos se preguntaran cual es la verdadera escencia de la lluvia o que Orisa es el que se respeta y se le da conocimiento en ese reino.

“Sango” es una de las divinidades en la Tradicion Ifa-orisa más popular ya qué tiene un gran número de seguidores, como se puede traducir su nombre o sus interpretaciones; El niño de la piedra del rayo, Sango es una divinidad que nos da apoyo en el área de vencimiento de dificultades y enemigos, principalmente por ser uno de los reyes de Oyó denominados Alafi ya qué era un líder muy querido y admirado por su pueblo, la forma de darle reverencia como cualquier otro Orisa ha sido siempre de respeto por la misma importancia de que nos ayuda a superar cualquier obstáculo.

En el verso sagrado Osa meji nos indica como podemos buscar el apoyo del señor del rayo para vencer a nuestros enemigos, dificultades y encontrar justicia espiritual ante acciones incorrectas de nuestros contemporáneas.

Recitacion del verso a continuación:

Yoruba:

Ó sáá méjì lákòjà

Ó bú yekeyékè lójú Opón

A díá fún Olúkòso làlú

Bámbí Omo a rígba ota ségun

Èyí tí ó gòkè àlàpà ségun òtá è

Ebo n wón ní ó se

Ó sì gbébo nbè

Ó rúbo

Njé kín lÀrìrá e sétè?

Igba ota

N lÀrìrá e sétè

Igba ota.

Traducción al español:

Ó sáá méjì lákòjà

Ó bú yekeyékè lójú Opón

Hicieron adivinación para el Olúkòso làlú

Bámbí Omo a rígba ota ségun

El que escalaría una pared de barro en ruinas para ganarle a sus enemigos

Fue el sacrificio que ellos le aconsejaron ofrecer

Él oyó hablar del sacrificio

Y lo realizó

¿Qué es lo que Àrìrá había usado para ganar la guerra?

Cientos de piedras.

Es lo qué Àrìrá había usado para ganar la guerra

Cientos de piedras.

Aseo..!❤️⚡️🤍

0 notes

Text

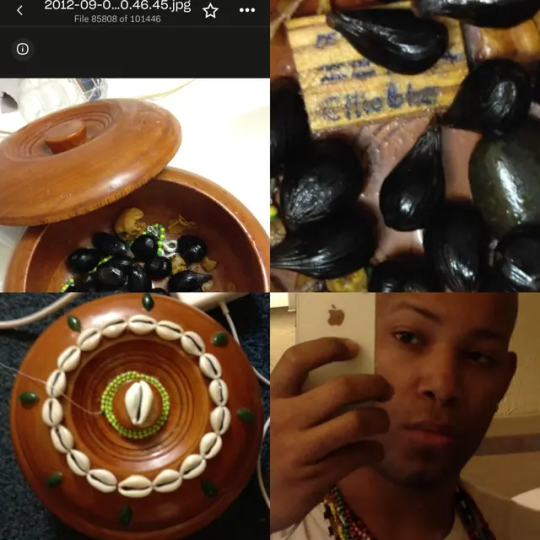

How you start is not always How you finish

My first intro to Orisa was a way of Self Discovery, i was already working on my spirituality, training with Mentors in the Psychic community and reading clients when my regular reader Kept telling me that there was an african woman behind me saying the word “O-ri-sha”. Neither of us knew What that word meant but he insisted that I Found out. This Psychic was an old white man. A Message is a message despite the appearance of the Messenger

I eventually Traveled to New Orleans many times, had various experiences, even moved and became a reader there without ever knowing that New Orleans was where my paternal great grandparents immigrated to the USA from Jamaica through New Orleans, which I discovered many years later.

After getting into contact with a well nown Santero in Miami, I flew over to get Divination done, receive my elekes, guerreros, olokun, palo muerto etc. even got scratched in Preparation for doing ocha.

I eventually left the ile and my ocha basket, my elekes and orisas there After many things occurring, things spoken during misas that made me go hmmm and just general blockages. Several times my GPS would stop working and I would find myself lost for hours trying to find my padrino’s home. With him being a santero of elegua, I thought that was significant.

Eventually I took a break, went to a Babalawo and received my hand of ifa, new warriors etc. Discovered that the previous house was planning to initiate me to the wrong orisa, it was supposed to be his orisa and felt a type of ways. The babalawo that cast my odu isefa had the same ifa odu as me and also was a little shocked and my oluwo tried to illuminate my naive mind.

I took a long break from the religion, I had noticed that I garnered way more success without it, I had made the most money in my career, when I just left santeria alone. I tried one last time to give cuban ifa a try with another babalawo who remade all my shrines, taught me, mentored me, gave me me osain and allowed me to help him with clients and basic rituals and sacrifices. Learned a lot but same as before, nothing miraculous really changed. I switched to an Isese babalawo (popoola lineage) for ebbos just for change of perspective. I effectively left santeria, ifa and orisa for good, I would just get an ifa divination once in a while.

I went back to vodou because that was my first ATR experience and the ancestral pull as well as it actually worked for me. But during kanzo in Haiti, I started to dream a lot about Africa, somewhere I had never been or wanted to go, and I blew it off.

Months later, I had this strange dream involving sango, talking about ifa, I thought it was ludicrous so I contacted my babalawo for divination, and the odu cast spoke about both sango and going into ifa. Weeks later, I got another divination from someone from an afa lineage without telling him anything and he had a similar divination result. So I took it seriously after talking to 3 different babalawos from three different lineages and countries.

I found myself in africa for the first time, I was afraid, I did afa initiation as well as other ceremonies, I was still apprehensive though. After coming back to usa, I got an outside divination and it came out in ibi, someone was trying to take me out.

I got very ill, doctors ran tests for 5 weeks even wearing a heart monitor and they could not figure out why my heart was failing. Yup, I was dying at 33 years old, 5 years later my brother died at 33. You probably guessed it, it was an inside the family thing. Anyways, I was terminated from my employer and I threatened to sue them very publicly because I had nothing to lose. They settled, I had a large sum of money but I was still dying so I had two choices have fun or do orisa initiation and hope for a miracle.

I was invited to the ebohon center in Benin city, got my nigerian visa but I was too sick to travel back to africa, didn’t have medical authorization, so I went to Brazil instead, to initiate under one of Araba agboola’s godchildren there, I stayed for 5 weeks. I did a lot of ceremonies. I went into trance with orisa for the first time, then again and again. It was around the third time that I felt a significant change in my heart beat and the palpitations had stopped. Within 3 months, I never had another problem again.

I went back to Brazil and found out I was touched by the candomble bug via my previous godfather, meaning he mixed some things Brazilian and Isese. one tradition does not wipe out the other, no baptism can undo a previous ceremony also finding out that sango never left me alone despite him not being the orisha of my ori. I went to a festa of xango at the famous terreiro do cobre, one girl was mounted with xango, hugged me and wouldn’t let go until I slipped into trance. I woke up in the back room and the iyalorisa of the lineage said I had to do some ceremonies in candomble. I went to various terreiros to get differing opinions and they all said similar things. So that’s how I ended up in candomble when I didn’t want to be.

Before the pandemic, I went back to nigeria and Benin to learn, study, do more ceremonies over a planned trip of 6 weeks which turned into 6 months. Surprisingly enough I ended up in the ile of another popoola lineage babalawo and iyanifa without realizing it.

just clarify my relationship with the popoola family is purely transactional, I bought their entire library of books, lectures, songs, etc, did divination with them for many years and used their olorisas they usually employ but they don’t consider me to be affiliated and so neither do I. I have never met chief popoola in person

Ejiogbe is the odu of many ebbos, sacrifices, orikis, loss, abundance, gossip, jealousy, betrayal, triumph over adversity, healing, longevity, being well known but alone, many taboos, honesty but many lie on you, charity without gratitude or acknowledgment.

0 notes

Text

"Rule With Fear Of Olodumare', Araba Of Ibadanland Tells New President, Other Elected Political Office Holders

The Araba of Ibadanland and Oluisese of Oyo State, Chief Ifálérè Odegbemi Odegbola II has urged the President, Bola Tinubu, Seyi Makinde and other elected political office holders in the country to rule with fear of Olodumare. Araba stated this while speaking with journalists at this year’s annual Ifa and Orisa festival organised by Odegbola Traditional Global Services, Ibadan. The Araba of…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

https://x.com/VoiceOfOurAnces/status/1684228431477612544?s=20

"Why isn't the embed version showing? Hov, get your kids." - Esh

#orisa #ifa #hov #jayz #antiifa #santeria #palo #egbe

0 notes

Photo

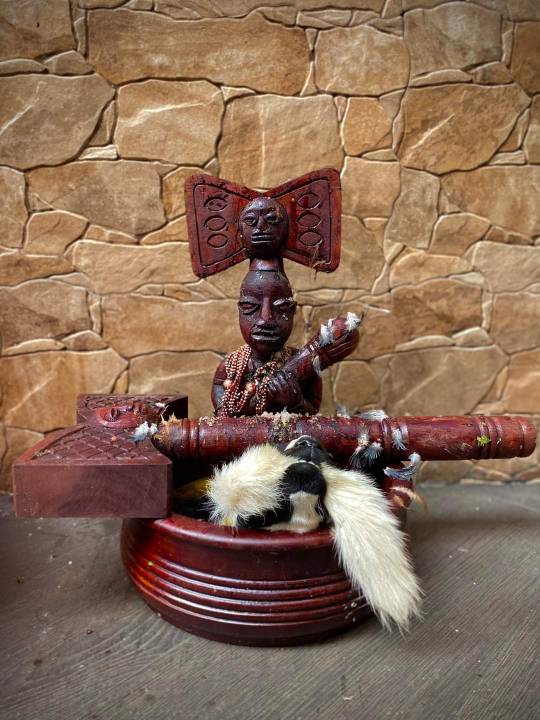

Shango priest

#santeria#lukumi#lucumi#candomble#umbanda#macumba#yoruba#shango#xango#chango#sango#orisha#oricha#orixa#orisa#orisaifa#orisa ifa#ifa#ifá#priest#orisha priest#shango priest#chango priest

2K notes

·

View notes

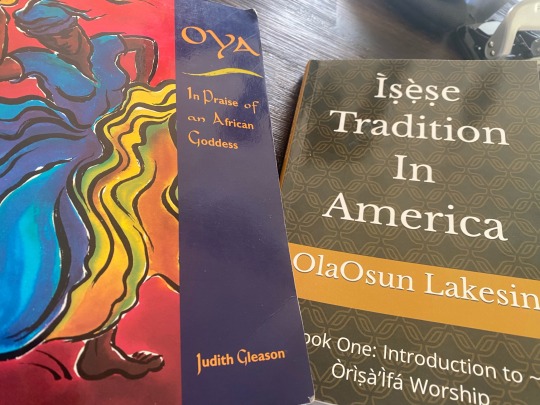

Text

Presently reading

#black dark academia#dark academia#poc dark academia#noir library#books#books books books#reading#book lover#bibliophile#bookblr#black spirituality#african spirituality#african traditional religions#isese#ifa#Oya#orisa#orisha#Judith Gleason#Dr OlaOsun Lakesin#presently reading#currently reading#current read

14 notes

·

View notes