#or rather there is no room for nuance in criticism of certain media so I am not going to waste braincells over it

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

I wanted to drop by and tell you that I love you. No matter what happens I am glad you're still here on tumblr. Your absence is always felt :') Thank you for sharing your ideas and lovely fics with us!

Thank you, dear anon. It’s been difficult to focus since finishing DALDOM and I don’t have the spirit I used to (which is normal, life ebbs and flows). My love for my faves hasn’t faded but being here, on tumblr, has its pitfalls when parts of modern fandom are very fickle.

I’m always around, just not always present, as many can attest to. I will probably never be active in the ways I used to be but this blog won’t be going anywhere.

#right now my health is imperative over the next few weeks#there may be a vent fic about it one day#juni chats#thank you sweet anon#every day I think about going back to shitposting and spamming my dash but like#I have no thoughts anymore and honestly I’m over a lot of stuff that goes on here#or rather there is no room for nuance in criticism of certain media so I am not going to waste braincells over it

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Saw your Star Wars post and I think a lot of Sith apologists don't understand the difference between control and repression

They say that the Jedi forces everyone to behave a certain way, but a lot of them operate under their own set of beliefs. While they still uphold the core Jedi beliefs, everyone still has their own path

The Sith are the ones who are repressing people. Show no weakness. Empathy and kindness aren't allowed. Obey my orders or die. Wasn't there a dark side user who's final test was murdering his own brother?

What a euphoric and freeing experience....

god i made that post a while ago, so its a good thing some delusional ass dredged it back up to talk nonsense on it a little bit ago, cause otherwise i'd probably have to go looking for it again.

but as for the whole control vs repression thing, there are a lot of factors there ranging from georges failures in writing/directing, to the general public's difficulties in grasping nuance when it comes to things in the popular media sphere [not unless its screamed in their faces], how star wars expanded universe material has for decades grabbed firmly on the wrong end of the stick when it comes to the sith, to more abstract angles about how modern capitalistic societies overly value individualism in an abstract idealized sense etc.

so i dont think its entirely unique or unusual for sith apologists to latch onto that. rather, i think what kinda strikes them as unique is also why the acolyte ended up being such a shit show.

because for all of its faults, acolyte was ultimately the story that a lot of vocal portions of the star wars fandom had been loudly claiming they wanted to hear and see. a jedi critical sith positive show about how the jedi order are religious repressive and suppressive space cops well the sith are cool badasses who live their hashtag blessed hashtag truth. plop a sample size of star wars fanfic writers and fan work creators in a room and i am fairly certain atleast a good majority of them would claim thats what they wanna see.

but instead the acolyte bombed pretty badly. for numerous reasons of course, but the important aspect of that discussion is that the people didn't flock to that vision the acolyte presented in droves. if anything they were fairly indifferent.

and well that first and foremost proves the age old adage of people dont know what they want, i do think its illustrative in how sith apologia has dominated a lot of the fan understanding and discourse around star wars, well in practical reality the majority of people don't engage with star wars in that regard.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Wtf is with the Tudor fandom?? Those are the same people who have “cancelled” Isabel and Fernando lmao for their colonization of America. Why are they so mad when we talk about Elizabeth I + colonization then? who tf do they think they are by saying “social justice warriors”?

I feel, personally, like the weaponization of serious issues for the purposes of ships and stanning various figures has kind of brought us to this point, ngl. Anne Boleyn supporters bring up the Inquisition, bring up slavery, bring up the colonization of America, while KOA supporters toss Ireland and the treatment of black and Jewish people around like a ping pong ball, on and on, back and forth, pettier and pettier with each exchange. There’s no real room to discuss anything, because it’s inherently polarized, and the only ones who really lose are the ones in the fandom who wanted to discuss it from the beginning because it reflects some part of their lived experience, only to find themselves used as pawns and then discarded when they’re no longer of use. And, in that area, as a white American Celticist, I got off fairly clean. I haven’t had to deal with the constant harassment that others have had to deal with. I’ve just been lied about and ignored, which, in many, many ways, is better. Annoying, but better.

I’m personally at an odd place with Ferdinand and Isabella given that I do live at Ground Zero of the Spanish colonization of America - The people of Florida have, for the most part (though not uncontroversially), begun to seriously question the narratives that we were always fed about Ponce de Léon and the “Discovery” of Florida, taking into account more re: his treatment of the Táino people, who were exploited, enslaved, and butchered by Spanish forces who were paid with Ferdinand of Aragon’s gold, working under Ferdinand of Aragon’s authority. We are starting to question what, exactly, it means when we talk about having the oldest continuously occupied city in the nation, along with the question of where the legendary emeralds of the lost Plate Fleet (that, let’s be real, we ALL want to find) came from, which hands mined them before they were put into crucifixes, whose blood stains them. I’m not going to pretend I have any personal love of them, though I recognize their overall historical importance. I think that, like any other historical figures, we can talk about the good and the bad, along with the lasting effects, both good and bad, of them and their reign.

That being said, the blatant hypocrisy of the Tudors fandom to criticize one fandom when, the second the spotlight is turned on them, they suddenly demur and claim that, actually, that doesn’t MATTER anymore, it was centuries ago, is galling. Either we critically analyze history like adults for both sides of the Catholic VS Protestant debate, acknowledging that both sides committed atrocities that echo down to the present, or we don’t. We keep brushing things under the rug, keep trying to argue why our faves were the most pure, keep trying to enter into a dick measuring contest with a thin veneer of academism. (And, at the risk of putting too fine a point on it, in my field, I have just as much standing as they do. I’m not asking for people to bow down or even to take what I say uncritically, since I hate elitism in the field, but I AM asking, if they’re claiming to be academics and using that to swing their weight around, to give me the same respect as another academic. You can’t have the respect that comes with the position without acknowledging the responsibility.)

All I ever REALLY wanted was for people to talk about the darker side, not to permanently #Cancel anyone (the past is a fucked up place—If I didn’t feel like I had to constantly defend my field’s existence constantly from people wanting to paint the Irish as barbarians, I could tell you some REALLY fucked up things from Irish history/literature. Especially the literature), but to TALK about the nuances involved, only to find that, on both sides, people only really cared about boosting their own pet faves. I’m not saying “You can only post a gifset of Elizabeth/Isabella if you include a dissertation tacked on at the end of how they weren't #GirlBosses", rather that the general perception of them needed to become more nuanced, and yet, somehow, that led to me becoming one of the black sheep of the Tudor fandom. (That and, admittedly, mentioning the very true fact that one British Dynasty has received more media attention in 20 years than the entirety of Irish history’s received in cinematic history…..which I stand by, not the least because I didn’t mention WHICH dynasty, since it applies, in fact, to multiple, including the present ruling dynasty.) (Okay, and calling an ugly fraud of a portrait an ugly fraud of a portrait. Which I also stand by.)

One thing that I appreciate with the saner parts of, for example, the French Revolution fandom is that, while it can still be quite polarized, there is, essentially, at least the IDEA that both sides fucked up and did fucked up things. The idea that, even though you can appreciate that certain figures, like Robespierre, like Marie Antoinette, like Philippe Égalité (though I’m still working on that one) were slandered in their time, they ALSO were complicit in some terrible, terrible things. I haven’t really seen any Robespierre fans defending, say, the September Massacres, the Vendée, or the suppression of the Brezhoneg language. (I’ve gotten more mixed reviews from the pro-Royalist side, but at least the understanding that the Ancien Régime and the people in it weren’t ideal, which is more than I’m getting on this side.) Is the Frev fandom ideal? No. It isn’t. It suffers from many of the same shortcomings as any other historical fandom, and there are quite a few people I utterly refuse to engage with because I find them to be too extreme on one side or the other (being the one Orléanist Stan™ does help things along), but, that being said, at least they’re having SOME historical perspective.

I made the unfortunate mistake of thinking that, when people said “Oh, yes, we can appreciate these things in the context of their time, with critical thinking!” They actually meant it, as opposed to just wanting an excuse to shut us up until we’re useful again. Instead, I quickly realized that people only cared so long as it bolstered them and their side, not about the people who were actually harmed, and if we bring THEM up, we’re SJWs. No need to argue with what we’re actually SAYING if you can just lie about us repeatedly. And, frankly? I’m utterly disgusted at the number of blogs that I thought would know better, who I respected for their nuanced approach to history and the study of it, humoring them. I’m utterly disgusted at how their narrative of “Evil SJW”s has actually gained currency from people who have based their entire reputation, sometimes their careers, on critical thinking and analyzing biases.

#long post#and i'm absolutely sure they're going to find this and find SOMETHING to use against me#Anonymous

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

this isn’t a proper discourse post, I Agree with a lot of what the op said but there’s specific things about it that get under my skin in a way that makes me want to talk about it, but I don’t want to engage with that post both because I don’t want to speak over the point that’s being made and frankly because I don’t want to be misinterpreted because of the point that’s being made in it.

so for context, I’ll just say that it was a long post about how a lack of engagement with women characters in fandom spaces is tied to misogyny. just be aware that I’m responding to something specific and not criticisms of this in general. (feel free to dm me if you want to see the post for yourself)

the rest of this is going to be rambly and a bit unfocused, so I want to get this out the door right at the top: it is not actually someone’s moral obligation to engage with or create fan content. all other points aside, what this amounts to is labeling people as bigoted for either not creating or engaging with content that you want to see, and while the individual may or may not be a bigot it’s not actually anyone’s job to tailor their fandom experience to cater to you.

fandom is not activism. it’s not Wrong to point out that a lack of content about women in fandom is likely indicative of the influence of our misogynistic society. and suggesting that people examine their internalized biases isn’t just fine, it’s something that everyone should be doing all the time. but saying that it is literally someone’s “responsibility” to “make an effort” by consuming content about women or they’re bigoted is presenting the consumption of fan content as a moral litmus test that you pass and fail not by how you engage with content but by not engaging with all of the Correct content.

judging people’s morality based on what characters they read meta for or look at fanart for is, a mistake. it Can Be Indicative of internalized biases but it is not, in and of itself, a moral failing that has to be corrected.

if you want more content to be created about women in fandom then you do it by spreading content about women in fandom, not by guilting people into engaging with it by saying that they’re bigots if they don’t. you encourage creation Through creation.

okay, now to address what Mainly set me off to inspire this post.

this post specifically went out of it’s way to present misogyny as the only answer for why this problem exists in fandom spaces. and while I absolutely agree that it’s a Factor, they left absolutely no room for nuance which included debunking “common excuses.” which, as you can probably guess, contained the things that ticked me off.

first off, you can’t judge that someone is disconnected from women in general based on their fandom consumption because the sum total of their being is not available on tumblr.

people don’t always bear their souls in fandom spaces. just because they don’t actively post about a character or Characters doesn’t mean that they see them as lesser or that they don’t think about them. the idea that you can tell what a person’s moral beliefs are not based on what they’ve said or done but based on whether they engage with specific characters in a specific way in a specific space can Only work on the assumption that they engage with that space in a way that expresses the entirety of who they are or even their engagement with that specific media.

what I engage with on ao3 is different from what I engage with on tumblr, youtube, twitter, my friend’s dms, and my own head. people are going to engage with social media and fandom spaces specifically differently for different reasons. you can’t assume what the other parts of their lives look like based on this alone.

second off, there can be other factors at play that influence people’s specific engagement with a fandom.

they specifically brought up the magnus archives as an example of a show with well written women. which while absolutely true, does Not mean that misogyny is the only option for why people wouldn’t engage with content about them as often. for me personally? a lot of fan content is soured because of how it presents jon. I relate to him very heavily as a neurodivergent and traumatized person, and he faces a Lot of victim blaming and dehumanization in the writing. sasha and martin are more or less the only main characters that Aren’t guilty of this, and sasha was out of the picture after season 1.

while this affects my enjoyment of fan content for these characters To Some Extent on it’s own (I love georgie, I love her a lot, but I can’t forget that she looked at someone and told them that they were better off dead because they couldn’t “choose” to not be abused), the bigger issue is fan content that Specifically doesn’t address the victim blaming and ableism as what it is, even presenting it as just Correct.

this isn’t exclusive to the women in the show by any means, this is exactly why I avoid a lot of content about tim, but it affects a lot of the women who are main characters. that isn’t the Only reason, there’s more casual ableism and things that tear him down for other reasons (the prevalent theory that elias passed up on sasha because he’s afraid of how she’s More Competent In Jon In Every Single way. which comes with the unfortunate implications of jon being responsible for his own trauma because he just wasn’t competent enough to avoid it) but that’s the main one that squicks me out.

of course not all fan content does this, and I Do engage with content about these characters, but sometimes it’s easier to just stick with content that centers on my comfort character because it’s more likely to look at his character with the nuance required to see that it is victim blaming and ableism.

it’s not enough to say that the characters are well rounded or well written and conclude that if someone isn’t consuming or creating content about them then it has to be due to misogyny and nothing else.

there’s also just like, the Obvious answer. two most prominent characters are two men that are in a canonical gay relationship, which draws in queer men/masc people on it’s own but the centering of their othering and trauma Particularly draws in traumatized queer people that are starved for content. georgie and melanie are both fleshed out characters in and of themselves, but their relationship with each other doesn’t have nearly as much direct screen time. and daisy and basira have a lot more screen time together and about each other, but their relationship is very intentionally non-canon because of its role as a commentary on cop pack mentality.

people are More Likely to create content for the more prominent relationship in the show and be drawn into the fandom through that relationship in the first place. I have no doubt that there Are misogynistic fans of the show, but focusing on the relationship and the characters that make you happy isn’t and indication that you’re one of them.

which brings us to the big one, the one that sparked me into writing this in the first place (and the last that I have time for if I’m being honest). the “common excuses” section in general is, extremely dismissive obviously but there’s only one section that genuinely upsets me.

without copying and pasting what they said directly, it essentially boils down to this: while they recognize that gay and trans men are “allowed” to relate to men, they’re still Men which makes them misogynistic. Rather than acknowledge Why gay and trans men would engage with fan-content specifically that caters to them they present it as a given that it’s 100% due to misogyny anyways. they present queer men engaging with content about themselves as them treating women like they’re “unworthy of attention,” calling it a “patriarchal tendency” that they have to unlearn.

being gay and trans does not mean that you’re immune to misogyny, being a woman doesn’t even mean that you’re immune to misogyny, but that’s engaging in bad faith in a way that really puts a bad taste in my mouth.

queer men aren’t just like, Special Men that have Extra Bonus Reasons to be relate to boys, they’re people who are more likely to Need fandom spaces to explore facets of themselves. and while you can Relate to any character, it feels good to be able to explore those aspect with characters that resemble you or how you see yourself.

when I first started actively seeking out fandom spaces in middle school I engaged with content about queer men more or less exclusively. at this point I had no concept of what trans people were, and wouldn’t begin openly considering that I might be a trans person until high school. I knew that I’d be happier as a gay man before I knew I could be a gay man, and that’s affected my relationship with fandom forever.

I engage with most things pretty casually, reblogging meta and joke posts when I see them, but what I go out of my way to engage with is largely an expression of my gender identity and sexuality. I project myself onto a comfort character and then I Consume content for them because that was how I was able to express myself before I knew that I needed to. it’s not that girl characters aren’t “worthy” of me relating to them, it’s that I specifically go to certain fandom spaces to express and work through my gender and sexuality. that’s what I use those fandom spaces For.

I imagine that I’ll need this crutch less when I’m allowed to transition and if I ever find a relationship situation that works out for me. but also like, why should I? it’s not actually hurting anyone for me to explore my gender and sexuality through fanfic until the end of time. nor does it hurt anyone for me to focus on my comfort characters.

fandom is personal comfort and entertainment, not a moral obligation. people absolutely should engage with women in media and real life with more nuance and energy than they do, but fandom spaces are not the place to police or judge that.

#discourse#I've been writing and rewriting this for 4 and a half hours instead of going to bed before 9 am#I already know that absolutely no one is going to read this so I don't know why I did this to myself#also I couldn't find a place to fit this in so I'm just gonna say it here#sometimes people just engage with fandom based on characters that they find attractive#and if that means boys then that means boys#it doesn't have to be more complicated than that

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

The whole "forced diversity" shit is so stupid and it really makes zero sense to me considering the points made by geeks either refer to the bad writing independent of whatever race of gender said character is, or referring to something that necessitates the need for a poc to be in a film which shouldn't have to be the case. Women and poc shouldn't have to justify their existence in popular media. I'm sorry to say this but black people weren't invented in 2019. Gay people were not invented in the 21st century, the real world really do be like that and it's fine for there to be shitty gay romcoms as much as it's ok for there to be good films with gay characters in it without people feeling the need to point at those bad films and say "See this is forced diversity. This is why we shouldn't make gay movies anymore" like it makes no fucking sense. That's not to say there isn't a such thing as hollow representation and being disrespectful of the people trying to be represented, but that's more or less an executive decision made to try and appeal to more audiences for marketing purposes (Le Fou from Beauty and the Beast) that at times can be tone deaf or just so shoddy that whatever representation was there was probably only implied or just in the background somewhere, but I don't know a single person who thinks tokenism is a good thing, and even if tokenism is what "forced diversity" is, then why is the term "forced diversity" used to refer to other instances of supposedly unjust casting then? Who's a fan of queerbaiting? I don't get it because even then, it comes down to how it's written and framed. A gay character simply being "That one gay" is typically the result of bad writing and honestly I'd very much call that half-assed diversity since clearly they don't care about their gay characters that much aside from having "the gay" in it and nothing else. But like I said, that's tokenism, and for some, the mere sight of gay characters in nerd culture is enough for the anti-woke police to come and arrest you for inclusivity crimes. Diversity itself isn't even the problem.

Nothing is even wrong with diversity for diversity's sake. Doesn't inherently have to damage a narrative, and if we're talking "agendas" the agenda first and foremost is to make money. Their little faux progressivism is just a marketing tactic. There's no secret coalition of people in Hollywood "forcing the gays in" because they just really like the gays. They don't care THAT MUCH. Queer Eye doesn't exist because imaginary cultural marxists exist in Hollywood to reinforce "the gay agenda". Queer Eye exists to perpetuate the whole "conventionally attractive, flamboyant, gay friend trope" that's tired since it exists to hit a certain itch for straight audiences. Same shit with RuPaul.

"Ah but they wrote this character as being a black woman."

Ok.

"But see they did that because they wanted to really be inclusive and have some black casting."

Aight.

"They did this because they wanted to promote a super duper communist sjw agenda"

Cool. Why is this a problem? What makes any of this "forced". Have all the past instances of progressive messaging in other forms of media not counted as forced or "sjw?" If they come off a certain way with it's themes, that's probably intentional. That sucks. Guess Star Wars was sjw propaganda all along since it's about killing space fascists.

"But that character used to be a white man that's forced :c"

Like idk what to say to this other than the fact that inclusion and the changing of races for the sake of inclusivity is fine as long as that character is still well written, and even if it isn't, shouldn't mean to condemn the changing of identity of said character. Although there is a point to be made regarding creating new diverse characters instead.

"They hired that actress because she's black."

As long as they hire her while concerning the significance of her skills and talents and use that for a stunning performance featuring a black woman, then I'm cool with thinking about inclusivity in the hiring process.

This whole thing about promoting diversity somehow meaning not being able to write something well is nonsense, because at a certain point you aren't even talking about diversity anymore, so why bring it up? Those two things aren't mutually exclusive, and if you want to get mad at executives for not giving the minorities they're representing the genuine care and fine touch they deserve, wouldn't it make sense to demand they write these diverse characters better? This especially matters if the narrative you're telling heavily relies on the identity of your cast, and is thus key to write those aspects regarding your characters well. A lot of this "forced diversity" talk just seems like lazy criticism while avoiding any substantial counter-criticisms by pretending to be nuanced about a very non-issue.

You'll have that one guy who goes on about how some scripts explicitly mention the identity of a character and it's like.... Do you think casting wonder woman as a literal woman, because her role necessitates she be a woman, is also forced diversity? It's literally in her name. What if there's a movie exploring themes of female identity and such. I feel like even if it isn't relevant, people just vaguely describe certain characters as male, female, whatever. When did scripts or directors stating that they wanted a woman playing a lead all of a sudden constitute as somehow forcing diversity LMFAO. "Oh well one is artificial while the other isn't" uh, what? Last time I checked all fictional narratives are artificially written and made into products for people to enjoy and consume. Nobody looks at the numerous bad films featuring straight white dudes and go "This is forced caucasity, this is why whites shouldn't be in movies" like what. I don't remember anyone making that argument when Samurai Cop or The Room was made.

I wish the people who complain about forced diversity would just say they don't like seeing certain demographics in their movies instead of playing 32-dimensional chess as a way to avoid getting called mean words. Like just peel the mask, this is so tiring. I'd rather you just say you don't agree with certain characters representing minorities you don't like instead of spawning a pointless debate. That's not to say everyone who pulls up the whole "forced diversity" schtick is bigoted, but y'all pls. The mask comes off when y'all claim Hollywood is "far-left" when the most left leaning thing in Hollywood is Mark Ruffalo.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Northanger Abbey Response

First off, I really like how experimental Northanger Abbey is. The way that Austen "breaks the fourth wall" in order to poke fun at the tropes of Gothic literature, and defend the novel as an art-form, is so unusual and surprisingly engaging. I'm thinking particularly of the joke at the end, where Eleanor Tilney's husband is revealed to be the one who left the receipts behind in the chest in Catherine's room. It's a really interesting approach, and it lets her keep the novel a loving pastiche rather than a mean-spirited parody. I could definitely tell that this was written by fetus-Austen; for example, she often puts quotes around instances of free indirect discourse, which I don't remember seeing in her later work. I'm not sure if this was insecurity on her part (about whether readers would "get it"), or if it was to maintain a separation between the speaker's voice (which is unusually present) and the character voices. Either way, I found quotes around free indirect discourse confusing, and am glad she later dropped them.

The experimental nature of Northanger Abbey is a good reminder of several things. First, that the timeline of art history, while useful, is artificial; writers in the past were capable of the kind of sophistication we associate with modernity. Second, that stuff written by amateurs and young people is often experimental (even if unintentionally!) in interesting ways (see fanfic). Third, that the early days of a medium are often experimental and forward thinking in ways that are rediscovered later (I'm thinking of how Orson Welles' video essays prefigure YouTube video essays). Fourth, that the "rules" of writing are just suggestions, that can be disregarded if they get in the way. And finally — most importantly — it’s a reminder that Jane Austen does not miss.

I'd like to also comment on Austen's defense of the novel as a medium, in conversation with "A Paradox at the Heart of Jane Austen's Defense of the Novel." Austen's take on the value of the novel is quite measured, which I suppose is related to the grounded, observational nature of her writing generally. I had the criticism of fiction (particularly, YA fiction), which Austen makes through Catherine; I grew up reading a lot of novels, and while I never thought they were accurate to real life, I do remember wishing they had addressed real life more directly. You can only read so many novels about teens being turned into child soldiers before you wonder, what am I supposed to do with myself outside an active war zone? That being said, I'm a fan of fantasy and science fiction, as well as the Gothic, and my feelings now are that it's great to be campy and unrealistic because real life is often stilted and boring. You can even see that in Northanger Abbey; it's a testament to Austen's prowess that the novel manages to be entertaining, when the story itself is pretty messy and large parts of the novel are unsatisfying. This is especially true right now, with the plague on: sometimes, I just want to read about necromancers. So, I'm left with a pretty nuanced take on the issue, which is where Austen and Merril's analysis of Austen ends up.

This is a discussion too big for one blog post, but I think the question Austen raises in Northanger Abbey ultimately cuts to the heart of what art — with the novel as a subset of art, and the YA novel a subset of that — is for. Should books be entertaining or instructive? One answer to that question, which I've been playing with, is to argue that all stories are didactic. This is trivially true, in the sense that reading a book involves learning the details of the story; but, often, people describe how they enjoyed "learning about the characters, and the world" of a story. There's a bias against art made for didactic purposes (I think as a reaction to Chick Tracts, after school specials, and lots of "bad" didactic art), so maybe that argument is a little heretical. But think about how much time people invest in learning about "lore": I think it's reasonable to say that at least one of the pleasures of reading is learning.

Plenty of "educational" content is also entertaining and artistically complex; in fact, I think that books are one of the best ways of broaching certain topics with kids/teens. (I'd even go so far as to argue that teaching is a kind of performance art, but that's way off topic.) Personally, I think the reason for the current bias against explicitly didactic art is a side effect of the way that children and teens are constructed by the mainstream. Stories are about nuance, and complexity, but if you're not allowed a more interesting take than "drugs are bad lol," it's going to be difficult to make something interesting. And that's an issue with all media made for children and teens, not just didactic media. I think this is why Austen's nuanced take on the value of the novel is so often misinterpreted. Austen's construction of the child is much more realistic than most during her time period (and ours); this keeps her honest in her appraisal of the novel as an art form.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The role of lore in MASS EFFECT for me.

Lore is a fascinating thing in science fiction, it can expand impossible worlds with deep complexities that paint their absurdities with a strange believability. But lore can also be restrictive, cumbersome and dry that it saps out all of the thematic/artistic nuance of media.

You need a careful balance of specific detail and room for inference.

Franchises I feel that become too drunk on lore can fall apart in spectacular ways. Sometimes there is just so many books, comics, wiki pages and supplementary material that any coherency a general audience can reasonably fathom is thrown directly out the window as the ball of superfluous information reaches such a critical mass it annihilates anything in its direct path.

HALO 5 is an obvious example of the worst excesses of required lore that I have ever seen in a big budget follow up to a successful franchise, especially one that I loved so much. The plot makes absolutely no fuckin sense unless you have read several books, watched a very terrible movie, played certain spin off titles etc and a whole page of a website is dedicated to telling you what exactly you need to buy. The original games let the players discover the deep intricacies of the lore in their own time through terminals and perhaps reading or watching the optional supplementary material, but the bulk of the games primary focus was on the main plotline dedicating all the art, love, music and care into making it as meaningful as possible. 5 flipped that on its head and created an inferior experience as a result, it became a history book...

What reason is there to infer, speculate and reflect on if everything is just spelled out to you plain as day like an encyclopedia entry. Detail matters in a plot to make sure its fluent and coherent but as said, too much of it can pretty much derail the experience.

The goal becomes “How much do players know?” Rather than “How do we tell a great story?”

Hideo Kojima is one of the worst offenders when it comes to this practice of relying so much on a deep canon while also spelling it out all to the audience in dialogue. MGS4 is a complete and utter mess of subplots and long winded dumps of exposition that its cut-scenes have become infamous for being the longest and most boring in any game.

Death Stranding looks to be no different...

MASS EFFECT is full of deep and complicated lore. You can find it in the codex, comics, animation and more but the great thing about it was that it served as a skeletal structure for the flesh of the universe to hang onto and evolve on. When it needed to be changed or broken Bioware could do so easily sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worst. But still It allowed for a creative freedom, letting the series communicate its themes and messages clearly in a entertaining format without getting bogged down in superfluous nonsense only a small percentage of people would really understand or care about.

Part of the fun of hybrid pop/hard scifi, is its distinct ability to be both believable and flexible at the same time. You can play the whole of the trilogy and not once have to open up the codex to understand what the hell was going on, and this is becoming rarer in media as time goes on.

You are having to spend more of your time and money on understanding the mechanics of a single piece of media and i’m quite frankly sick of it.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

A very interesting read

Meghan Markle and Kate Middleton’s fans are fighting a fierce new royal feud

In the world of British duchess fandom, there’s no room for divided loyalties: praising one means automatically 'hating' the other, writes Patricia Treble

A new war started in 2018, and it’s a take-no-prisoners affair with major implications for the future of the royal family. The once-genteel, even genial, online world of royal watching has been turned upside down and inside out as fans of Kate, Duchess of Cambridge, and Meghan, Duchess of Sussex, duel for social media supremacy and, in the process, tear down anyone who dares to challenge their view of the royal world. There’s no room for divided loyalties: praising one means automatically “hating” the other.

Signs of the slagging aren’t hard to find. Just dive into the royal family’s own social media accounts, then follow the online infection trail. “Please give us MORE MORE MORE of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge. Sick to absolute death of fake narcissistic MeAgain Markle,” a commenter wrote on a photo of Prince William and Kate on the royal family’s Instagram account. Kate is “clinging to dear life to Willnot [sic]. His attention is on HRH Meghan,” says another beside a Kensington Palace photo of Kate at a laboratory. “Kate will never be on Meghan’s level, all that lazy consort did was marry a Prince, she don’t know about working, and connecting with others, don’t disrespect Meghan like that,” writes @HRHmegh on Twitter. “Meghan speak so bad and she was fake and she is an actress she know who act. But Kate always is natural,” comments another.

“It is really unbelievable,” says Susan Kelley, who is near the epicentre of the Kate vs. Meghan fan wars because of her two popular royal fashion websites—What Kate Wore, which she started in 2011, and What Meghan Wore, which she co-manages with Susan Courter. “Every time I tell people about it who aren’t in the Kate-Meghan world, they are incredulous.” While the two Susans, as they are known, approve comments before they are posted on the Meghan and Kate sites, “on certain days you can’t go 30 to 60 minutes without checking” Facebook to delete over-the-top comments, Kelley notes.

The reason for the sudden increase in vitriol isn’t hard to find. Seven years after marrying Prince William and being the only leading young female royal, Kate has “competition” in the form of a beautiful American former actress, Meghan Markle, who married Prince Harry in May. William, Kate, Harry and Meghan may be known as the “Fab Four,” but to fans, it’s an either-or choice. The Meghan and Kate acolytes appear to be very young, and accustomed to a social media world that not only condones but seems to encourage anonymous insults. It’s not for nothing that such devotees are known as “stans,” a combination of stalker and fan.

The fans aren’t living in an “and” world but in an “or” one. “Don’t get out of your lane, don’t be coming into my lane,” is how Kelley sees them. “This has been just extraordinarily troubling to me,” she continues. “This is 2018. If this was two men, this would not be happening. I thought we were beyond this…There is something so off, the level of hatred and how intense it is, and the volume.” Perhaps most disturbing for everyone is the level of intolerance, even racism. Not only is Meghan, the daughter of a black mother and white father, the focus of racist attacks, but her fans, in turn, quickly toss the “r” word at perceived Meghan opponents.

Susan Kelley isn’t alone. Everyone reports the same thing—a sudden, disquieting increase in harassing attacks that seem completely over-the-top given the rather sedate royal topics being discussed, including fashion, engagements, living arrangements, protocol and even the state of a curtsy or bow. “I have witnessed what amounts to be roving Twitter gangs that find a tweet/blog post about Meghan and kind of rally the troops and stoke up the fires and suddenly you have a hail storm of abuse flowing at you,” explains Jane Barr, who runs the From Berkshire to Buckingham fashion site, which focuses on Kate. “For me, it is very frustrating to write a nuanced analysis and have people just take a black-and-white interpretation and run wild with it.”

Advertisement

“I think it is indicative of a larger societal problem,” says Barr. “We have an inability to listen to other people, and reason and debate together as a community. The ramifications are obvious for free democratic societies, and very concerning.” In seven years of blogging, Barr has blocked two people for foul language. In the past year, she’s blocked between 15 and 20 for “completely out of control behaviour.”

Royal outrage is complicated by a transatlantic culture clash. Many intense Meghan Markle fans are Americans who don’t understand the monarchy, its place in British society and how there has always been criticism of the family, royal author Victoria Arbiter told the Express. “The American community doesn’t have anything like the royal family so they can only liken them to celebrities or politicians,” she explained. Their lack of knowledge of the intricacies of royal life, protocol and history explains some comments. For instance, they can interpret a photo being posted on a royal feed as a sign of the Queen’s personal approval for Kate or Meghan, their clothes or their behaviour, rather than the work of a member of the royal media department.

“Celebrity rivalries are always conducted by us, the fans, the people who buy the concert or theatre tickets, the records, the merchandise and who send the memes through social media,” contends Ellis Cashmore, a sociology professor at Aston University in England whose book Kardashian Kulture will be published in early 2019. “It helps if there is genuine animosity, but it’s far, far from essential—or even necessary. As long as we think they’re fighting, that’s enough to sustain the feud. We enjoy the feuds so much, we’re tempted to take sides and engage, albeit vicariously. Today, social media has made this easy; so much so that fans can keep the fight going independently of the principals.”

Many stans believe that Meghan and/or Kate don’t like each other and are coming between the close relationship of brothers William and Harry. The reality that the two brothers now have their own families and own priorities doesn’t appear to factor into their online fights. Every new bit of information—Harry and Meghan leaving the tiny two-bedroom Nottingham Cottage around the corner from William and Kate’s London residence for a larger house on the Windsor estate, or reports that they are ending their joint staffing arrangement, established when they were teens—is fought over. To some, the former Meghan Markle is the Yoko Ono of Kensington Palace: “Megan [sic] is the reason for the split between William and Harry,” commented one fan on the royal Instagram feed.

And in the busy autumn season of royal engagements, the war may be at a tipping point. Earlier in 2018, the work schedules of the two popular duchesses didn’t overlap. At the beginning of the year, the focus was on Kate while Meghan slowly dipped her toe into royal engagements. Then, when Kate went on maternity leave in late March, the focus swung back to Meghan, who married Harry in a wedding watched by billions. Kate stayed largely out of the public eye until after Harry and Meghan completed their high-profile tour of Australia, Fiji, Tonga and New Zealand.

But now, both royal women are both doing royal work, both based in their London home of Kensington Palace. And that’s setting up an inevitable “showdown” between how the media covers them—who gets top billing, who gets criticized? The palace, no doubt aware that social media is swimming in bile and acid, appears to be trying to mitigate the intense fan reactions. On Nov. 21, both Meghan and Kate were out and about in London, yet their schedules were carefully timed to not conflict with each other. As well, neither event touched on the subject matter of the other, and neither was announced to the public in advance.

In the morning, the Duchess of Sussex went to the Hubb Community Kitchen. Meghan had been making private visits there since January and, with the help of funds raise by a charitable cookbook she helped create, the women are making 200 meals daily for local groups in the area, devastated by the Grenfell Tower fire. A few hours later, Kate arrived at University College London’s developmental neuroscience lab to be briefed on the latest “research into how environment and biology interact to shape the way in which children develop both socially and emotionally.” Coincidently (or not), both wore outfits in shades of burgundy and plum. The preparations paid off. The Express put the two on its front page with the headline “Double duchess: Kate and Meghan’s copy-cat fashions.” For the record, the large photo was of Meghan, the inset of Kate.

The irony is that the Kate and Meghan stans are engaging in behaviour the royal women they profess to adore would find abhorrent. All four of the young royals are committed to raising the profile of mental health issues, including the negative effects of social media. On Nov. 15, William gave a powerful speech about the harmful effects of cyberbullying: “When I worked as an air ambulance pilot or travelled around the country campaigning on mental health, I met families who had suffered the ultimate loss. For too many, social media and messaging was supercharging the age-old problem of bullying, leaving some children to take their own lives when they felt it was unescapable.”

“I am very concerned though that on every challenge they face—fake news, extremism, polarization, hate speech, trolling, mental health, privacy, and bullying—our tech leaders seem to be on the back foot,” William continued before issuing a challenge: “You have powered amazing movements of social change. Surely together you can harness innovation to allow us to fight back against the intolerance and cruelty that has been brought to the surface by your platforms.”

Cashmore doesn’t see the Kate/Meghan social media battle stopping any time soon. “The beauty of our screen society is that, once people get on their phones or laptops, they become a force majeure—nothing and no one can stop them,” he explains. “If they say there’s an argument, then there’s an argument. Meghan and Kate can deny it all they like; it won’t alter a thing!”

There seems little room for neutral observers. Journalists are taking it from all sides. Any criticism—real or imagined—of one duchess is perceived by many fans as an attack, and also favouritism for the other royal woman. In the past year, virtually every full-time royal correspondent in London issued a plea for tolerance on Twitter. After being accused of everything from bias to racism, Richard Palmer of the Daily Express wrote, “We have all faced unpleasant and unfounded accusations of racism towards Meghan.” He pinned a tweet to the top of his account stating that “with the exception of a few I have known for years, I’ve decided I will only now engage with those who share their real identities.” Some journalists are also blocking extreme fans.

And the attacks don’t just stop at those who critique. The fans demand total loyalty. As Richard Palmer commentedon Twitter, “As far as I can see the pitchfork brigade have just regarded anything not 100-per-cent gushing as racist ever since with no evidence.” Susan Kelley has seen the same: it’s not enough to speak the truth, but they many readers accept only “complimentary, laudatory things.”

Netty Leistra, a veteran Netherlands-based royal journalist and blogger, has tried to avoid the Kate vs. Meghan fight, but an online critic called her a racist a few months ago for saying “absolutely nothing special.” For Leistra, the current phenomenon brings back memories of around 15 years ago, when Australian Mary Donaldson married Crown Prince Frederik of Denmark. In the era before Twitter, Facebook and Instagram, she and a few others ran an online forum about the couple. Soon, the anti-Mary folk were battling with the pro-Mary fans. “The bad thing to us was that we tried to be objective, and in the end we were the ones being attacked for not protecting any of the two sides,” she recounts. In the end, they stopped the forum.

Today, no one thinks things will improve any time soon. Both Kate and Meghan are full-time working royals, both gearing up their charitable activities, Kate after her maternity leave, Meghan as she settles into her new royal role. Perhaps a break will come when Meghan gives birth in the spring and steps away from the public spotlight to concentrate on being a mother. Meanwhile, royal watchers who want to engage in polite conversations and debates are trying to block the more extreme commenters, and hoping tempers will cool—or interest will die down.

#duchess of cambridge#kate middleton#british royal family#prince william#duke of cambridge#prince harry#harry and meghan#meghan markle#duchess of susex

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Looking Around: Reflections on Preservation

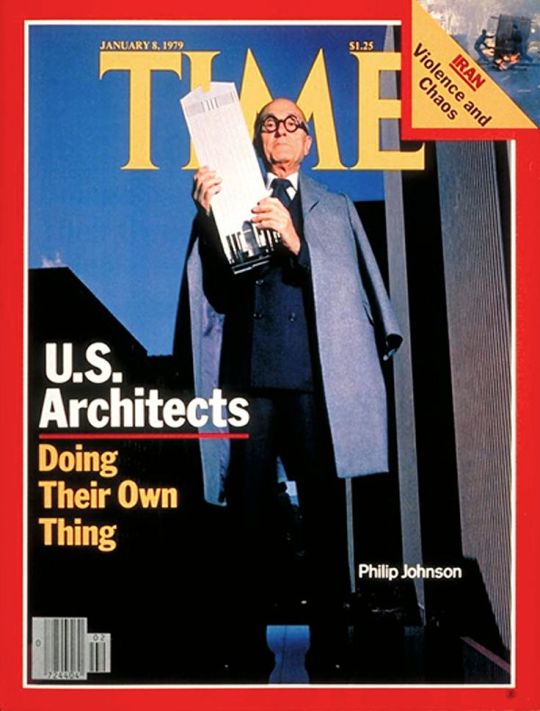

If you, like me, happen to follow architecture rather closely, you may have recently noticed several folks in the community talking about their Johnson. Always fond of puns, it’s the 20th-century American architect Philip Johnson they’re referring to, rather than, well, you know.

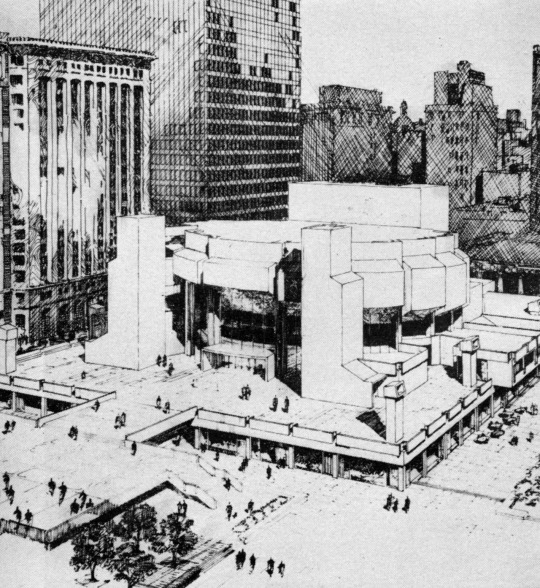

Two weeks ago, it was announced that the Norwegian firm Snøhetta revealed plans to overhaul the front facade of Johnson’s iconic 1984 AT&T building, a Postmodern skyscraper located at 550 Madison Ave in New York City.

Philip Johnson’s 550 Madison Ave (formerly known as the AT&T building). Left Image by David Shankbone, CC BY 2.5. Right Image by Matthew Bisanz, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Proposed changes by Snøhetta. Via Dezeen.

While this is not the first renovation to the tower (Charles Gwathmey did a less invasive but, in this writer’s opinion still problematic rehab in the 90s), architects and critics, famous and obscure alike, were quick to decry the changes. Olly Wainwright, architecture critic for The Guardian, in no small words, called the plans “vandalism.” Mega-architect Norman Foster, no friend to Postmodernism, said on Instagram that the building was nevertheless “an important part of our heritage and should be respected as such.”

Image by Anna Fixsen, Metropolis Magazine. Via Twitter.

A protest was organized, seen above. On the far right, you can see the famous Postmodern architect and former Dean of the Yale School of Architecture, Robert A.M. Stern, holding a model of the building.

A hashtag, #SaveATT, was created, alongside a Twitter account, @Save_AT_T, and a Change.org petition shortly followed.

You may be wondering why all of these architects and critics are losing their minds about a renovation of an 80s building that looks relatively sleek and contemporary. It’s not so much that the proposed renovation in and of itself is objectively bad, it’s about the building for which the renovation was proposed.

The Lowdown on Johnson’s Highrise

Before we get into the details, I’ll say it straight-up: the AT&T building, including its lobby, should absolutely be saved. Why? 1) Because it is probably the most famous example of Postmodern architecture, and 2) because it caused the biggest architectural hissy fit since the birth of Modernism.

Philip Johnson was, until the AT&T building, a high-modernist architect who built a large number of corporate headquarters and a famous glass house. Always a controversial and infuriating character, he decided, seemingly on a whim, to take a Postmodern turn in designing his tower for AT&T.

The Glass House by Philip Johnson. Photo by Staib (CC BY-SA 3.0)

In 1979, when the AT&T tower was announced, Postmodernism (a movement characterized by the revisiting, distorting, juxtaposing, and recontextualizing of historical architectural forms within a contemporary philosophical and aesthetic context) was a relatively theoretical movement, not yet thrust into the eye of the general populus.

Postmodernism had a certain critical eye that cast its gaze at (what was seen at the time as) the stifling hegemony of Modernist architecture, which the Postmodernists found cold, technocratic, and corporate. That the style was appropriated by Johnson for a major corporate building, made a few theorists rather angry, as corporatism was one of their key criticisms of Modernist architecture.

Johnson on the cover of Time Magazine holding a model of the AT&T Building.

To rub more salt in the critical wound, the AT&T building was Postmodernism’s first big media moment, obscuring the smaller, more nuanced works of the movement’s first five years, which added to the hissy fit. Charles Jencks, the eternal gatekeeper of the movement, was so in crisis at the ruining of his nuanced art by a particularly vain starchitect, that he had an existential crisis, asking “Is Postmodernism Dead?” Jencks would continue to see the building as a transition from “real” Postmodernism and “PoMo” aka Postmodernism that Jencks does not like.

Don’t worry, it’s probably all explained in one of his extremely great charts.

After AT&T, Postmodernism exploded in popularity and quickly replaced Modernism as the hegemonic architectural style, endlessly replicated, splayed across a landscape of gabled museums and courthouses; shopping malls and parking decks. RIP to theoretical purity, born: 1968, died: 1979. Cause of Death: Philip Johnson.

While it may be startling that a building completed in 1984 is already in existential danger, such danger is becoming more and more common, sooner and sooner after the building is completed.

Preservation itself is always a difficult topic, one that raises many questions: Why should we save buildings, and what makes a building worth saving in the first place? Why should we save just the exterior of the building? Why not the interior or landscape as well?

Why Should We Save Buildings?

Buildings are worth saving for several reasons. Sometimes, a building has an interesting cultural history - perhaps an important person was born there, or it was the site of a burgeoning subculture, or an important historical event. Sometimes a building is worth preserving because it is a particularly good example of its architectural style, or because it’s the only example of its particular style in the surrounding area.

Sometimes a building is worth preserving simply because it is beautiful, old, or built by a famous architect. Sometimes, like in the case of Johnson’s AT&T building, the building should be preserved because it had an important role to play in architectural history, theory, or criticism.

My own story of how I began writing about architecture is one that opens with loss - the kind of needless loss that should never happen again.

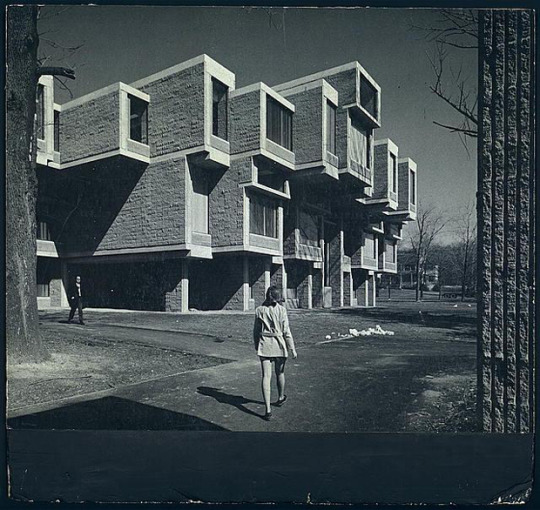

Paul Rudolph’s Orange County Government Center. Via Library of Congress.

When I was little, I was a house fanatic. (As we can clearly see, not much has changed.) Whether it was watching the then-nascent HGTV channel, or dirtying my mother’s station wagon windows with nose-prints watching yard after yard scroll by, I could not get enough of houses. For most of my young life, architecture was defined by houses.

My mother grew up in Goshen, New York, and we would occasionally go up there to visit family and friends. When I was around thirteen or fourteen, we took a wrong turn looking for a Dunkin Donuts, allowing me to stumble upon the building above, Paul Rudolph’s Orange County Government Center, built in 1967.

This building was unlike any building I had ever seen before, and in the few minutes we stopped by, it had transformed my ideas about what a building was, what it could be. It was the building that introduced me to architecture.

Around 2010, when I finally figured out what building it was, I learned that it had been threatened with demolition. My first ever snippet about architecture I had written was a letter pleading the National Trust for Historic Preservation to intervene. Throughout high school, I wrote at length about the need to save Modernist buildings so that they could have the same effect on future generations as they had on me.

In 2015, my junior year of college, it was announced that the fight for preservation had been lost, and Paul Rudolph’s masterpiece was mutilated beyond repair. I will never be able to revisit the building that inspired me to begin writing about architecture. If I’d never gotten to see that building, it’s unlikely that McMansion Hell would have ever materialized. I can say with some certainty, at the risk of being melodramatic, that had I not seen that building, I would be a completely different person than the one sitting here writing this.

Orange County Government Center during its Demolition. Photo by Daniel Case. CC BY-SA 3.0.

Now, others won’t be able to have that experience. What’s left of Rudolph’s work is beyond uninspiring, a shell of what used to be an innovative, form-defying building. What could have inspired many to make deeper inquiries into their built environment has been reduced to a non-place housing the DMV.

We don’t like to think of buildings as being non-permanent. When a building is constructed, there’s an expectation that it’ll last forever. Buildings seem monolithic, stable, permanent. It’s in a building’s very design to be anchored firmly to the ground, to be able to brave the elements, withstand the years. While natural disasters are responsible for the destruction of a great many buildings, the fickleness of the aesthetic tastes of human beings has felled a great many more.

After around the 70-year mark of a building’s life, it becomes significantly more at risk of demolition. Several books have been written about lost buildings in many cities, sparing few details about how needless some of these losses were. In Baltimore, as in other cities, many a masterpiece was felled in the mid-20th century to make room for a rather infamous building sniper: parking decks and parking lots.

Maryland Casualty Building. Demolished in 1984 in order to build a parking lot.

When it comes to pre-20th century buildings, whose preservation is argued for far more often than buildings like AT&T or Rudolph’s Government Center, the argument isn’t necessarily that these buildings are somehow superior architecturally to others because of their age, but because they are totally irreplaceable.

Even if you wanted to build a full-scale replica of a demolished building from, say, the 18th century, it’s likely that the materials needed to rebuild it are no longer around. Most of the marble and stone quarries that brought us styles like Richardsonian Romanesque or Gothic Revival, were completely depleted. In addition, the construction methodologies required for pre-industrial building practices are either not likely to get approval because they aren’t up to modern building codes or because some of those trade skills are simply lost. Regardless, the cost of replacement materials, as well as the labor needed to build these historic buildings, are both economically unviable.

On a more surface level, old buildings are snapshots of how people once lived, and saving them is an important part of charting the history of human development, historically and technologically.

Mechanics Theater, Baltimore, MD. Demolished in 2013 and replaced with a festering open pit.

A common fallacy of preservation is that it is reserved solely for the oldest, most ornate buildings, especially those relevant to the heavily sanitized version of American history taught in primary schools. I would argue that preservation is even more important for those buildings we find difficult to like, those that challenge us architecturally, like Rudolph’s Government Center.

There is always a point in time where a style of architecture is loathed by its successors. Many a Queen Anne Victorian house was razed because people at the beginning of the 20th century found them both dowdy, dusty, and plain unhygienic. Modernism was loathed by Postmodernism. Postmodernism is loathed by today’s architects who grew up in its shadow.

That which is loathed is not always that which is not worth preserving, but by the time we realize this, it’s often too late. Only after a building is threatened do people come rallying to save it, when these preservation efforts are more successful when they start long before the first threat. This is perhaps why so many houses by Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe skyscrapers remain for people to enjoy.

Interiors

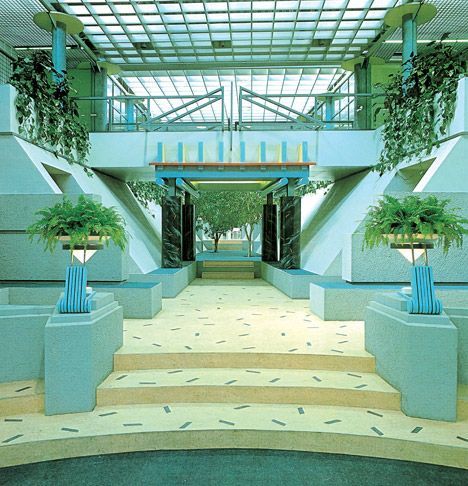

TV AM building interior by Terry Farrell. Remodeled, mid-1990s. Via Dezeen.

People go to visit old buildings (especially places like Museum houses) because they want to experience life as it was in a different era. The exterior is one part of this experience, but it’s the interiors which give people the sense that they are not merely looking at history but are instead enveloped in it.

Though there has been some progress over the last few years, interiors and landscape architecture have not been as high of a priority for preservation as a building’s exterior architecture, and because of this, there have been great losses, like the TV AM building above, in which I’m sure many 80s and 90s children would love to bask nostalgically.

I’m always delighted when, in my searches for this blog’s house of the week, I come upon a time-capsule house, that is, a house that hasn’t been remodeled since it was built. As the years go by, these houses have become less and less common, and their interiors have been replaced with today’s white furniture, contractor gray walls, and sparkling white trim.

Interior of a house in Florida built in 1980s from the archives of the author.

It’s hard to describe the feeling of loss that comes with looking at a house built in 1980 and discovering an interior fresh out of last month’s HGTV Magazine. Do I really think the world needs more overstuffed chintz sofas or shag carpeting? No, but the idea that a world without a single room decorated like it’s fresh out of a Laura Ashley catalog seems like quite an erasure of the pop cultural history of how everyday people decorated their houses.

I’ve devoted a large bookshelf to old catalogs, renovation books, interior design magazines, and other resources about how people decorated their homes partially out of personal obsession and partially because I’m afraid that someday that history will be lost in the material world and will only exist in the glossy imagery of those pages.

Conclusion

What deserves to be preserved and how that preservation is executed is in the eyes of the people. While that idea sometimes gets abused by ruinous people who use historic preservation designations to protect parking lots or empty spaces to prevent affordable housing from being built, or use preservation as a means of proving the superiority of one group of people over another, these bad eggs should not give us the idea that preserving or documenting our important spaces is somehow politically toxic.

Cottonwood Mall Demolition by Mike Renlund (CC BY 2.0)

The “our” is key. People experience architectural loss on an individual level. We can see this when the news reports a mall or shopping center is to be demolished - the comments on such stories are almost always people sharing their fond memories of school shopping, birthday parties, comings of age. When someone moves out of their house or apartment, there’s always a lingering sadness that whoever lives there after you will completely alter that place into their own small piece of the world.

While highly public campaigns like #SaveATT are one method of preservation, they aren’t the only way people like you or me can contribute to saving our collective architectural memory. Documenting and archiving one’s own life is, in itself, a way of preservation.

Inside Today’s Home, a 1979 decorating book from the collection of the author.

Got old catalogs or maybe photos of your parents’ house with all of its tacky decorating laying around? Consider scanning them and maintaining an archive or contributing them to one of the many online groups on places like Flickr or Archive.org devoted to maintaining collections of primary sources from certain time periods.

One of the most remarkable aspects of social media is that people are creating their own ethnographies, their own archives of collective memories through Facebook groups like one I’m in called “Old Baltimore Photos”, where participants get together and tell stories of how they experienced the city and its buildings as it used to be, on a scale past historians could only dream of.

As losses like the Orange County Government Center, barely in its fifth decade of existence, tell us, the time for preservation is not tomorrow or in a few years. The time for preservation is right now. If there’s a building that means something to you, take pictures, visit often, tell people about it! While it might take time and effort to make sure a building is protected for future generations, the first step of the process is always, as cheesy as it sounds, love.

HEY FOLKS! IT’S MY BIRTHDAY THIS FRIDAY!

Here are a few things you can do if you want to celebrate with me!

Sign the Petition to Save the AT&T Building!!: http://bit.ly/SaveATandT

Make a donation to DoCoMoMo US, the organization leading the fight to preserve important landmarks of Modernist and Postmodernist architecture: https://www.z2systems.com/np/clients/docomomous/donation.jsp

Consider supporting me on Patreon! I’ve started posting a GOOD HOUSE built since 1980 from the area where I picked this week’s McMansion as bonus content!

If you’re feeling particularly nice, you can view my book wishlist here: http://a.co/j5LNE0R

See you tomorrow with our Ohio McMansion of the week!

Copyright Disclaimer: All photographs are used in this post under fair use for the purposes of education, satire, and parody, consistent with 17 USC §107. Manipulated photos are considered derivative work and are Copyright © 2017 McMansion Hell. Please email [email protected] before using these images on another site. (am v chill about this)

#architecture#history#preservation#historical preservation#philip johnson#att building#postmodernism#modernism#paul rudolph#orange county government center#brutalism#late modern architecture#postmodern architecture

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Quality Should Not Be Binary

In my wanders through life in general - and the internet in particular - I’ve noticed a strange mindset regarding the quality of media and the people who produce it. It’s this weird idea that something is either 100% perfect, flawless and ‘how dare you claim to be a real fan while suggesting there’s anything wrong’, or that it’s completely awful, valueless and ‘you’re a terrible person for enjoying that or thinking it has anything to offer’ - sometimes flipping from one to the other as soon as a ‘flaw’ is revealed, or a ‘bad’ work does something suitably impressive.

This mindset has never really made sense to me. Maybe I’m a just habitual over-thinker who spends unhealthy amounts of time analysing things, but I can’t see how this sort of absolutist approach would do anything other than shut down discourse, limit the value to be had from a piece and maybe make people angry.

So in honour of that please enjoy some indulgently long navel-gazing about critical analysis and media quality.

Disclaimer: This post is going to summarise my personal philosophy. Everyone approaches life - and especially art - in their own way and far be it for me to say you’re wrong if you prefer a different approach. You do you.

Blindness Hurts Both Ways

To an extent I get the simple yes/no mindset. Analysis takes time and it would be exhausting to give an extensive, nuanced breakdown on your view at the start of every discussion. Plus the whole ‘dissecting the frog’ thing can definitely apply to enjoyment of media.

However, taking it to the point where you’re denying the positive side of things you dislike or refusing to acknowledge faults in works/people you enjoy has the potential to swing around and bite you in the butt.

Why deny yourself a useful experience? I think there’s an important distinction to make between being good and being useful. Subjective, technical or, ethical ‘badness’ is not the same as having no value. Similarly, being touching, entertaining or otherwise enjoyable doesn’t preclude something from having genuine problems.

Personally, I can find it difficult to work out exactly what’s going right in a generally positive piece. After all, ‘good’ doesn’t hinge on a single point - it’s usually the product of a lot of things working well together, and it can be hard to figure out cause and effect in a system like that. It’s much easier to look at a failed attempt and identify the specific elements that caused problems, where it had the potential to recover, and places where it might be succeeding in spite of those issues. Similarly, some works can be very strong except when it comes to ‘that one thing’, which in itself is a useful reference. Negative examples can be just as beneficial as positive ones, and turning a blind eye to a piece’s weaker aspects just denies you that tool.

On the other hand, sometimes a piece and/or creator can be ethically awful while being technically strong or succeeding at its intended purpose. In this case, while they’re not positive it can certainly be valuable to analyse the techniques they use, and even apply those tools when selecting and creating things for yourself.

It’s important to remember that acknowledging where something is strong isn’t the same as endorsing or supporting it, and that there’s a huge difference between pointing out a genuine weakness or failing and maliciously hating on a work or creator.

Why give something that much power? Starting with the gentler side, I think it’s important to remember that a work being ‘good’ on the whole shouldn’t be an excuse to gloss over possibly troubling elements or to give creators a free pass on their actions. Sure, even the best-intentioned artists make bad PR and creative decisions sometimes but it’s also valid to acknowledge and call out possible misbehaviour when it crops up, rather than blindly playing defence until it reaches critical mass and undermines the good of their work (or worse, actually hurts someone).

There can also be a danger to simply writing off and ignoring ‘bad works’, especially if you dislike them based on ethical grounds. If something ‘bad’ is becoming popular it’s usually a sign that it’s getting at least one thing right - whether that be plugging into an oft-ignored hot-button issue, or simple shock-value and shameless marketing. Attributing the success of such pieces to blind luck and ignoring any potential merits that got them there opens up the potential for other, similarly objectionable works to replicate that outcome.

Not to mention the issues that can come from letting these things spread unchecked. Think about how many crackpot theories and extreme notions have managed to gained traction, in part due to a lack of resistance from more moderate or neutral parties who at the time dismissed them as ‘too stupid’ or ‘too crazy to be real’. Unpleasant as it may be, I think there’s some value in dipping into the discourse around generally negative media. If nothing else, shining a spotlight on the misinformation or insidious subtext that a work might be propagating can help genuine supporters notice, sidestep or otherwise avoid the potential harms even as they keep enjoying it.

Why lock yourself into a stance like that? Maybe it’s just my desire to keep options open, but it seems like avoiding absolutist stances gives you a lot more room to move. Publicly championing or decrying a work and flatly rejecting any counterpoints runs the risk of trapping yourself in a corner that might be hard to escape from if your stance happens to change later. If nothing else, a bit of flexibility can help you back down without too much egg on your face, not to mention shrinking the target area for fans or dissenters who you might have clashed with in the past.

A little give and take can also help build stronger cases when you do want to speak out. Sometimes it’s better to just acknowledge the counterpoints you agree with and move on to the meat of the debate rather than wasting time tearing down their good points for the sake of ‘winning’. The ability to concede an argument is a powerful tool - you’d be surprised how agreeable people become when they feel like they’re being listened to.

Finally, from an enjoyment perspective, is it really worth avoiding or boycotting what could otherwise be a fun or thought-provoking experience just because you don’t 100% agree with it or have criticised it in the past? Sure, there are absolutely times when a boycott is justified but why deny yourself a good time just because it involves an element that’s been arbitrarily labelled ruinous. ‘With Caveats’ is a perfectly acceptable way to approach things.

Existence vs Presentation of Concepts

A rarer argument that occasionally pops up is the idea that certain works are inherently ‘inappropriate’, ‘distasteful’, or should otherwise be avoided purely based on their subject matter. Usually this revolves around the presence of a so-called ‘controversial’ topic; things like war, abuse or abusive relationships, sexual content, bigotry and minorities (LBGT+ relationships being a big one right now).

Personally I think this is a reductive and pretty silly way to choose your content. No topic should be off-limits for any kind of media. (With the possible exception of holding off until the target audience has enough life experience and critical thinking skills to handle it. There is some value in TV rating systems.) Yes, some concepts will be uncomfortable to confront, but they are part of life and trying to keep them out of mainstream art simply stifles the valuable real-world discussions and conversations they might spark.

What we should be looking for is how a work handles the concepts it chooses to use. There’s a world of difference between presenting or commenting on a controversial topic as part of a work, and misrepresenting or tacitly condoning inappropriate behaviour through sloppy (or worse, intentional) presentation choices. The accuracy of research and portrayals, use of sensitivity and tact, consideration for the audience and overall tone with which a topic is framed are much more worthy of consideration than simply being offended that the idea exists in media at all.

‘Bad’ Art, ‘Good’ People and Vice Versa

I think it’s important to remember that our content creators are, well, people. They’re going to have their own weird taste preferences, personal biases and odd worldviews that will sometimes show through in their output. They’re also going make mistakes - after all, to err is human. Unfortunately, in the creative pool you can also find some genuine bigots, egotists, agenda-pushers, abusers and exploitative profiteers who don’t care about the damage their work might be doing.

It can be discomfiting to notice potentially negative subtext in the work or actions of a creator you like, and upsetting to realise that a work you love is the product of a person who you can’t in good conscience support. Which of course leads to the discussion of art, artists, whether they can be separated and what to do when things go wrong.

Obviously I’m going to be talking primarily about the ethical/moral side of things, as I think most of us are willing to forgive the occasional technical flub, production nightmare or drop in outward quality from creators we otherwise enjoy.

It can also be a touchy subject so I’d like to reiterate that this is just an explanation of my personal philosophy. My approach isn’t the only way and I won’t say you’re wrong for taking a different stance or choosing to stay out of it entirely.

‘Bad’ art from an apparently ‘Good’ person In general, when it comes to apparent bad behaviour or negative subtext from otherwise decent creators, I favour the application of Hanlon’s Razor.

Hanlon’s Razor Never attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained by incompetence - at least not the first time.

Art is a subjective medium, with multiple readings and interpretations being possible from the same piece. It’s definitely possible for an author to lack the awareness or experience needed to notice when unintended implications or alternate readings have crept into their work. Sensitive topics are tricky to handle at the best of times and seemingly harmless edits or innocuous creative choices can stack into subtly nastier tonal shifts. Similarly, being a good creator doesn’t automatically make them good at PR or talking to fans - it’s easy to get put on the spot or to not realise the connotations of their phrasing and how it may have come across. Of course this still means someone messed up, and it’s totally reasonable to call them out for ineptness, but I’d take an unfortunate accident over malicious intent any day.

Then there are times when the negative subtext is a lot less unintentional. In that case I think it’s important to make the distinction between creator sentiment and the sentiment of the work, character or their production team (if collaborating) before making a judgement on them as an individual. For example, the presence of casual bigotry might be justified in historical piece that’s attempting to accurately portray the culture of the time, and a creator/actor might write/portray a protagonist with biases and proclivities that they personally disagree with for the sake of a more compelling story. The presence of a worldview within a work doesn’t automatically translate to the opinion of it’s creator.