#or mythical imagery or even philosophical imagery

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I am constantly rocking back and forth about potential religious imagery and philosophical topics they could’ve handled in uprising s2. Cyrus’ talks about fate and things simply being programmed and predestined. Tron’s status as a ‘fallen angel’, not fitting the pedestal he was once rooted to, doomed to fall further down until he’s lost himself. Mara ‘hating the sin, not the sinner’, despising what the Renegade did to Able, but still rallying for his cause. Beck spreading the word of Tron like it’s the word of gospel, being punished for it by non-believers. Beck and the myth of Sisyphus. Programs breaking free from their programming and finding their own purposes and paths in life. Ouhhh I need a minute

#uprising I desire more religious imagery NOW#or mythical imagery or even philosophical imagery#I ramble#this is nothing philosophical or mythical but:#I’ve thought abt this a lot but Cyrus n Beck really do make me think of different parts of Tron#Cyrus symbolizing his violent nature (which gets cranked up to 11 when he’s turned into Rinzler)#and Beck symbolizing the hopeful program he used to be (pointing at 1982/kh2 Tron)#very self indulgent w these thoughts ofc I don’t think Beck or Cyrus are exactly like Rinzler/1982 Tron but. idk it makes me think#the idea Tron sees parts of himself in both of them. myeah#I need to get these thoughts out somehow. need to draw them as religious sculptures or something I need it out#tron#tronblr

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Qilin (Chinese Unicorn)

The qilin (麒麟, or simply lin 麟) is a Chinese mythical creature, frequently translated as "Chinese unicorn." While this term may suggest a one-horned creature, the qilin is often depicted with two horns. However, like the Western unicorn, the qilin was considered pure and benevolent. A rarely seen auspicious omen, the qilin heralds virtue, future greatness, and just leadership.

Throughout history, the qilin can be found in Chinese literature, art, and accounts of day-to-day life. As one of the Four Auspicious Beasts – alongside the dragon, phoenix, and tortoise – the qilin also embodies prosperity and longevity and has a heavenly status. References to the qilin date back to ancient Chinese texts, where this revered creature is regarded as a sign of good fortune and an indicator of a virtuous ruler. Its association with the philosopher Confucius (l. c. 551 to c. 479 BCE) underscores its significance as an auspicious symbol. Qilin imagery was favoured across various Chinese dynasties, and its popularity extends across other Asian countries, including Japan, Korea, and Vietnam.

The Qilin in Classical Texts

In the classic The Book of Rites (also known as the Liji, date uncertain), the qilin is listed as one of the four intelligent creatures along with the phoenix, dragon, and tortoise, often referred to as the Four Auspicious Beasts. Each of these divine creatures symbolizes different virtues considered essential for successful and harmonious coexistence. Broadly, the dragon symbolizes power and strength, the phoenix renewal and grace, the tortoise longevity and stability, and the qilin prosperity and righteousness. Together, these beings convey a collective message of good fortune and balance.

The Classic of Mountains and Seas (the Shanhai jing, 4th century BCE), a proposed mythological geography of foreign lands, mentions several one-horned beasts, but none are specifically identified as the qilin. The earliest known reference to the qilin in ancient texts can be traced back to the Western Zhou period (1045-771 BCE), which is the first half of the Zhou dynasty, the longest-lasting dynasty in Chinese history. The qilin also appears in the Shijing, also called The Book of Odes or Classic of Poetry, said to have been compiled by Confucius in the 4th century BCE, making it the oldest extant poetry collection in China. The Shijing contains just over 300 poems and songs, with some thought to be written between c. 1000 to c. 500 BCE. The piece in question, "The Feet of the Lin", appears at the end of the section that captures the voices of the common people. From Bernhard Kalgren's translation, The Book of Odes (1950):

The feet of the lin! You majestic sons of the prince! Oh, the lin!

The forehead of the lin! You majestic kinsmen of the prince! Oh, the lin!

The horns of the lin! You majestic clansmen of the prince! Oh, the lin!

Here, lin refers to the qilin, and its defining physical features are likened to regal offspring and relations. Karlgren calls this "a simple hunting song, and an exclamation of joy" (7) and suggests it was originally about a real but rare animal, such as a type of deer, which became a fantastical legend later. In James Legge's translation of the same poem, he notes that the qilin had a deer's body, ox's tail, horse's hooves, a single horn, and fish scales. The qilin's feet are not used to harm any living thing, even grass; it never butts with its head, and does not attack with its horn. As a popular and freely available translation, these notes are frequently cited and show the qilin as supremely peaceful and benevolent by choice.

In the 5th century BCE, we find the qilin, again mentioned as the lin, in The Spring and Autumn Annals, a historical record of events occurring in the state of Lu. This chronicle records that a lin was captured in the 14th year of Lord Ai's rule, 481 BCE. Later scholars analyzed and attributed great significance to this event, as Confucius himself, the compiler of The Spring and Autumn Annals, might have done.

From James Legge's translation of The Chinese Classics, volume V, 1872, page 832, (translator's square brackets):

In the hunters in the west captured a lin.

Continue reading...

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

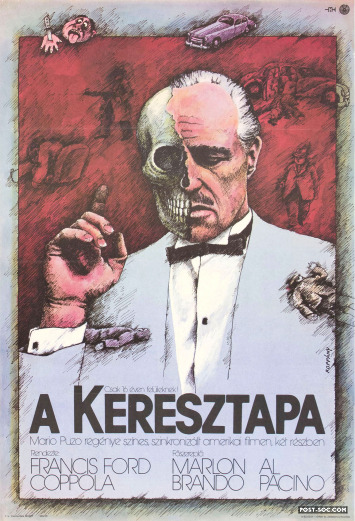

Beyond the Frame | A Reflective Essay on the History of Polish, Czech, and Hungarian Movie Poster Art

In the dim light cast between censorship and creativity, between imported spectacle and domestic interpretation, a unique visual culture emerged behind the Iron Curtain. In Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary, the humble movie poster became an unlikely arena for radical artistic expression. These were not merely promotional images; they were acts of translation, rebellion, and poetic vision. When American films reached Eastern Europe—scrubbed, dubbed, sometimes truncated—their glossy Western allure was peeled away and reconstructed by local artists into something deeper, stranger, and startlingly original. Especially notable is the use of abstraction, symbolism, and psychological metaphor that defined Polish, Czech, and Hungarian poster design from the 1950s to the late 1980s.

Cinema as Subjective Canvas

In the West, a film poster is commercial shorthand—stars, titles, and taglines rendered for maximum allure. But in mid-century Central Europe, posters were conceived not as marketing tools but as interpretations of film. This was possible because the films were distributed through state-controlled channels, which didn’t rely on consumer-driven advertising. Artists weren’t tasked with "selling" the film to the masses. Instead, they were often given titles and basic plot summaries—or, at best, preview screenings—and invited to create work that captured the essence of a film rather than its imagery.

This freedom, paradoxically enabled by a rigid political system, allowed artists to take enormous conceptual and aesthetic liberties. It also created fertile ground for the blending of avant-garde traditions—Constructivism, Surrealism, Expressionism, and Pop Art—resulting in a regional poster tradition that is now recognized as one of the richest and most idiosyncratic in design history.

The Polish School: Interpretation Over Illustration

Poland’s poster scene was particularly fertile, giving rise to the so-called Polish School of Posters in the 1950s. Led by figures like Henryk Tomaszewski, Jan Lenica, and Waldemar Świerzy, this movement elevated the poster to a medium of high art. Their designs rejected realism in favor of metaphor. A Polish poster for Jaws by Andrzej Krajewski might show a stylized swirl of water and teeth, abstracting the shark into a graphic pattern. For Apocalypse Now, one might see not helicopters or war scenes, but a disembodied head, part-masked, part-erased, floating in a red haze.

These designs stripped American cinema of its consumer packaging and re-presented it through a psychological or philosophical lens. Even genres like horror and action became meditations on fear, power, and alienation. The Polish approach was deeply personal, often humorous or grotesque, and almost always indirect.

Czech Surrealism: Playful Dissonance

In Czechoslovakia, poster artists like Zdeněk Ziegler, Karel Vaca, and Dobroslav Foll developed a style rooted in absurdism and surrealism. Where the Polish school leaned into painterly abstraction, the Czech approach often favored collage, visual puns, and theatrical imagery. American films like Grease or Planet of the Apes would be rendered in ways that deflated their commercial sheen—using bizarre juxtapositions, distorted mannequins, or torn photographs.

This reflected the country’s broader surrealist tradition—exemplified by filmmakers like Jan Švankmajer and artists like Toyen—and its subversive humor. Czech posters could be deeply irreverent, yet still evocative, often hinting at the absurdity of American idealism or the disjointed experience of watching foreign dreams play out in a constrained society.

Hungary: Modernism Meets the Mythic

Hungarian poster design, while sometimes overlooked next to its Polish and Czech neighbors, was no less radical. Artists like István Balogh, György Kemenes, András Máté, and Géza Gyalog developed a distinct visual language that fused graphic modernism with folk motifs and Bauhaus geometry. Hungarian posters were often cleaner in form but densely layered in meaning.

Their abstraction leaned toward minimalist surrealism: a floating eye, a single chair, a looming silhouette. A Hungarian poster for The Godfather might depict not Marlon Brando but a red flower bleeding across black paper. 2001: A Space Odyssey could be rendered as a stark black obelisk surrounded by primitive brushwork. The effect was often mystical, symbolic, and darkly introspective.

These artists were deeply influenced by the Hungarian avant-garde of the 1920s and 30s, and later, by the underground art scenes of Budapest. Their posters navigated a fine line—evoking inner worlds while commenting on the alien narratives imported from abroad.

Visual Resistance and Personal Codes

Across all three countries, abstraction was not simply an artistic choice—it was also a political strategy. Literalism risked censorship; ambiguity offered protection. These posters functioned as covert acts of resistance. By refusing to glorify American icons, by bending and twisting Hollywood's narratives, artists reclaimed interpretive power.

Moreover, in using abstract and expressionist styles, they left room for viewers to project their own readings. A viewer in Warsaw or Prague might see a poster for Taxi Driver and not recognize Robert De Niro, but feel the character's descent into isolation and violence through disjointed visual cues—a blood-red background, a distorted face, a fractured street lamp.

Legacy and Revival

With the fall of communism in 1989, the poster culture of Central Europe changed dramatically. Market liberalization ushered in glossy, uniform posters that mirrored global branding strategies. The old school of interpreters gave way to marketing departments and Photoshop.

Yet the legacy of Polish, Czech, and Hungarian poster art endures—not just in museums and retrospectives but in the resurgence of alternative movie poster design in the West. Collectors and cinephiles have revived interest in these works, and contemporary artists often draw inspiration from their daring, emotionally intelligent style.

In a time of algorithmically generated content, these posters remind us that art can illuminate what lies behind the screen, revealing the psyche beneath the spectacle.

Conclusion: Posters as Portraits of Imagination

The movie posters of Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary from the Cold War era are not merely historical artifacts; they are poetic documents. They reflect a time when artists were tasked not with selling fantasy, but with interpreting it—translating the distant dreams of America into images shaped by repression, wit, solitude, and resilience.

In abstracting the Hollywood dream machine, these artists didn’t diminish it—they expanded it. They asked not what a movie was about, but why it mattered. And in doing so, they gave us a parallel cinema—not projected on a screen, but drawn with ink, paint, and vision on fragile sheets of paper, speaking volumes without a single word of dialogue.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The original version of this story appeared in Quanta Magazine.

Is this the real life? Is this just fantasy?

Those aren’t just lyrics from the Queen song “Bohemian Rhapsody.” They’re also the questions that the brain must constantly answer while processing streams of visual signals from the eyes and purely mental pictures bubbling out of the imagination. Brain scan studies have repeatedly found that seeing something and imagining it evoke highly similar patterns of neural activity. Yet for most of us, the subjective experiences they produce are very different.

“I can look outside my window right now, and if I want to, I can imagine a unicorn walking down the street,” said Thomas Naselaris, an associate professor at the University of Minnesota. The street would seem real and the unicorn would not. “It’s very clear to me,” he said. The knowledge that unicorns are mythical barely plays into that: A simple imaginary white horse would seem just as unreal.

So “why are we not constantly hallucinating?” asked Nadine Dijkstra, a postdoctoral fellow at University College London. A study she led, recently published in Nature Communications, provides an intriguing answer: The brain evaluates the images it is processing against a “reality threshold.” If the signal passes the threshold, the brain thinks it’s real; if it doesn’t, the brain thinks it’s imagined.

Such a system works well most of the time because imagined signals are typically weak. But if an imagined signal is strong enough to cross the threshold, the brain takes it for reality.

Although the brain is very competent at assessing the images in our minds, it appears that “this kind of reality checking is a serious struggle,” said Lars Muckli, a professor of visual and cognitive neurosciences at the University of Glasgow. The new findings raise questions about whether variations or alterations in this system could lead to hallucinations, invasive thoughts, or even dreaming.

“They’ve done a great job, in my opinion, of taking an issue that philosophers have been debating about for centuries and defining models with predictable outcomes and testing them,” Naselaris said.

When Perceptions and Imagination Mix

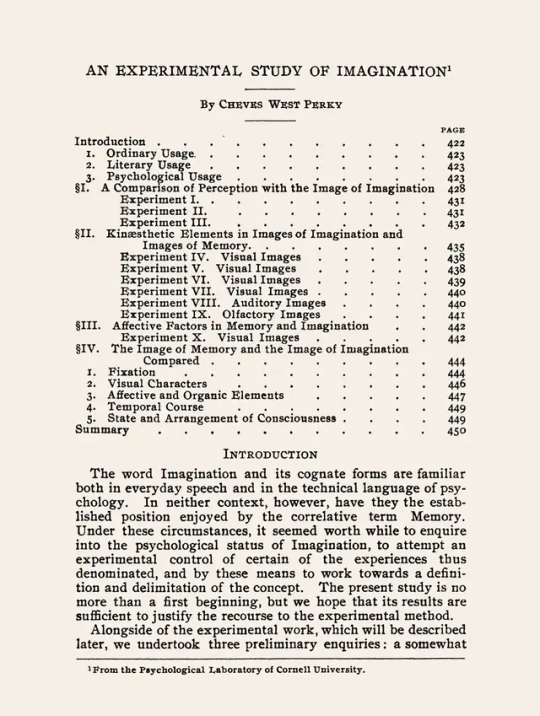

Dijkstra’s study of imagined images was born in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, when quarantines and lockdowns interrupted her scheduled work. Bored, she started going through the scientific literature on imagination—and then spent hours combing papers for historical accounts of how scientists tested such an abstract concept. That’s how she came upon a 1910 study conducted by the psychologist Mary Cheves West Perky.

Perky asked participants to picture fruits while staring at a blank wall. As they did so, she secretly projected extremely faint images of those fruits—so faint as to be barely visible—on the wall and asked the participants if they saw anything. None of them thought they saw anything real, although they commented on how vivid their imagined image seemed. “If I hadn’t known I was imagining, I would have thought it real,” one participant said.

A 1910 study by the psychologist Mary Cheves West Perky found that when our perceptions match what we are imagining, we assume that their inputs are imaginary.Photograph: DOI/Quanta Magazine

Perky’s conclusion was that when our perception of something matches what we know we are imagining, we will assume it is imaginary. It eventually came to be known in psychology as the Perky effect. “It’s a huge classic,” said Bence Nanay, a professor of philosophical psychology at the University of Antwerp. It became kind of a “compulsory thing when you write about imagery to say your two cents about the Perky experiment.”

In the 1970s, the psychology researcher Sydney Joelson Segal revived interest in Perky’s work by updating and modifying the experiment. In one follow-up study, Segal asked participants to imagine something, such as the New York City skyline, while he projected something else faintly onto the wall—such as a tomato. What the participants saw was a mix of the imagined image and the real one, such as the New York City skyline at sunset. Segal’s findings suggested that perception and imagination can sometimes “quite literally mix,” Nanay said.

Not all studies that aimed to replicate Perky’s findings succeeded. Some of them involved repeated trials for the participants, which muddied the results: Once people know what you’re trying to test, they tend to change their answers to what they think is correct, Naselaris said.

So Dijkstra, under the direction of Steve Fleming, a metacognition expert at University College London, set up a modern version of the experiment that avoided the problem. In their study, participants never had a chance to edit their answers because they were tested only once. The work modeled and examined the Perky effect and two other competing hypotheses for how the brain tells reality and imagination apart.

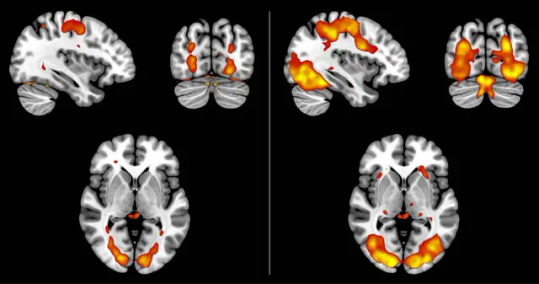

Evaluation Networks

One of those alternative hypotheses says that the brain uses the same networks for reality and imagination, but that functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) brain scans don’t have high enough resolution for neuroscientists to discern the differences in how the networks are used. One of Muckli’s studies, for example, suggests that in the brain’s visual cortex, which processes images, imaginary experiences are coded in a more superficial layer than real experiences are.

With functional brain imaging, “we’re squinting our eyes,” Muckli said. Within each equivalent of a pixel in a brain scan, there are about 1,000 neurons, and we can’t see what each one is doing.

The other hypothesis, suggested by studies led by Joel Pearson at the University of New South Wales, is that the same pathways in the brain code for both imagination and perception, but imagination is just a weaker form of perception.

During the pandemic lockdown, Dijkstra and Fleming recruited for an online study. Four hundred participants were told to look at a series of static-filled images and imagine diagonal lines tilting through them to the right or left. Between each trial, they were asked to rate how vivid the imagery was on a scale of 1 to 5. What the participants did not know was that in the last trial, the researchers slowly raised the intensity of a faint projected image of diagonal lines—tilted either in the direction the participants were told to imagine or in the opposite direction. The researchers then asked the participants if what they saw was real or imagined.

Dijkstra expected that she would find the Perky effect—that when the imagined image matched the projected one, the participants would see the projection as the product of their imagination. Instead, the participants were much more likely to think the image was really there.

Yet there was at least an echo of the Perky effect in those results: Participants who thought the image was there saw it more vividly than the participants who thought it was all their imagination.

In a second experiment, Dijkstra and her team didn’t present an image during the last trial. But the result was the same: The people who rated what they were seeing as more vivid were also more likely to rate it as real.

The observations suggest that imagery in our mind’s eye and real perceived images in the world do get mixed together, Dijkstra said. “When this mixed signal is strong or vivid enough, we think it reflects reality.” It’s likely that there’s some threshold above which visual signals feel real to the brain and below which they feel imagined, she thinks. But there could also be a more gradual continuum.

To learn what’s happening within a brain trying to distinguish reality from imagination, the researchers reanalyzed brain scans from a previous study in which 35 participants vividly imagined and perceived various images, from watering cans to roosters.

In keeping with other studies, they found that the activity patterns in the visual cortex in the two scenarios were very similar. “Vivid imagery is more like perception, but whether faint perception is more like imagery is less clear,” Dijkstra said. There were hints that looking at a faint image could produce a pattern similar to that of imagination, but the differences weren’t significant and need to be examined further.

Scans of brain function show that imagined and perceived images trigger similar patterns of activity, but the signals are weaker for the imagined ones (at left).Courtesy of Nadine Dijkstra/Quanta Magazine

What is clear is that the brain must be able to accurately regulate how strong a mental image is to avoid confusion between fantasy and reality. “The brain has this really careful balancing act that it has to perform,” Naselaris said. “In some sense it is going to interpret mental imagery as literally as it does visual imagery.”

They found that the strength of the signal might be read or regulated in the frontal cortex, which analyzes emotions and memories (among its other duties). But it’s not yet clear what determines the vividness of a mental image or the difference between the strength of the imagery signal and the reality threshold. It could be a neurotransmitter, changes to neuronal connections or something totally different, Naselaris said.

It could even be a different, unidentified subset of neurons that sets the reality threshold and dictates whether a signal should be diverted into a pathway for imagined images or a pathway for genuinely perceived ones—a finding that would tie the first and third hypotheses together neatly, Muckli said.

Even though the findings are different from his own results, which support the first hypothesis, Muckli likes their line of reasoning. It’s an “exciting paper,” he said. It’s an “intriguing conclusion.”

But imagination is a process that involves much more than just looking at a few lines on a noisy background, said Peter Tse, a professor of cognitive neuroscience at Dartmouth College. Imagination, he said, is the capacity to look at what’s in your cupboard and decide what to make for dinner, or (if you’re the Wright brothers) to take a propeller, stick it on a wing and imagine it flying.

The differences between Perky’s findings and Dijkstra’s could be entirely due to differences in their procedures. But they also hint at another possibility: that we could be perceiving the world differently than our ancestors did.

Her study didn’t focus on belief in an image’s reality but was more about the “feeling” of reality, Dijkstra said. The authors speculate that because projected images, video, and other representations of reality are commonplace in the 21st century, our brains may have learned to evaluate reality slightly differently than people did just a century ago.

Even though participants in this experiment “were not expecting to see something, it’s still more expected than if you’re in 1910 and you’ve never seen a projector in your life,” Dijkstra said. The reality threshold today is therefore likely much lower than in the past, so it may take an imagined image that’s much more vivid to pass the threshold and confuse the brain.

A Basis for Hallucinations

The findings open up questions about whether the mechanism could be relevant to a wide range of conditions in which the distinction between imagination and perception dissolves. Dijkstra speculates, for example, that when people start to drift off to sleep and reality begins blending with the dream world, their reality threshold might be dipping. In conditions like schizophrenia, where there is a “general breakdown of reality,” there could be a calibration issue, Dijkstra said.

“In psychosis, it could be either that their imagery is so good that it just hits that threshold, or it could be that their threshold is off,” said Karolina Lempert, an assistant professor of psychology at Adelphi University who was not involved in the study. Some studies have found that in people who hallucinate, there’s a sort of sensory hyperactivity, which suggests that the image signal is increased. But more research is needed to establish the mechanism by which hallucinations emerge, she added. “After all, most people who experience vivid imagery do not hallucinate.”

Nanay thinks it would be interesting to study the reality thresholds of people who have hyperphantasia, an extremely vivid imagination that they often confuse with reality. Similarly, there are situations in which people suffer from very strong imagined experiences that they know are not real, as when hallucinating on drugs or in lucid dreams. In conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder, people often “start seeing things that they didn’t want to,” and it feels more real than it should, Dijkstra said.

Some of these problems may involve failures in brain mechanisms that normally help make these distinctions. Dijkstra thinks it might be fruitful to look at the reality thresholds of people who have aphantasia, the inability to consciously imagine mental images.

The mechanisms by which the brain distinguishes what’s real from what’s imaginary could also be related to how it distinguishes between real and fake (inauthentic) images. In a world where simulations are getting closer to reality, distinguishing between real and fake images is going to get increasingly challenging, Lempert said. “I think that maybe it’s a more important question than ever.”

Dijkstra and her team are now working to adapt their experiment to work in a brain scanner. “Now that lockdown is over, I want to look at brains again,” she said.

She eventually hopes to figure out if they can manipulate this system to make imagination feel more real. For example, virtual reality and neural implants are now being investigated for medical treatments, such as to help blind people see again. The ability to make experiences feel more or less real, she said, could be really important for such applications.

It’s not outlandish, given that reality is a construct of the brain.

“Underneath our skull, everything is made up,” Muckli said. “We entirely construct the world, in its richness and detail and color and sound and content and excitement. … It is created by our neurons.”

That means one person’s reality is going to be different from another person’s, Dijkstra said: “The line between imagination and reality is just not so solid.”

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

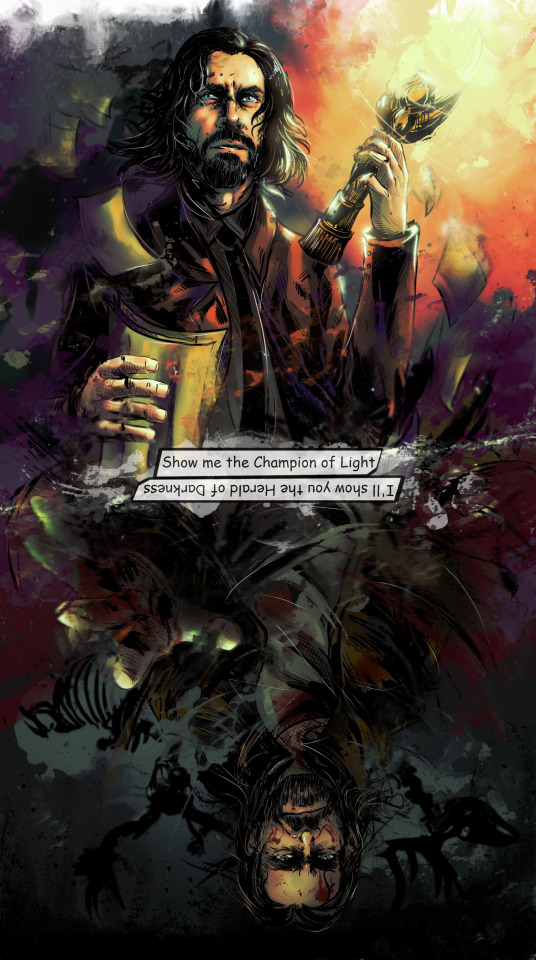

Deep Symbolism Breakdown: Alan Wake & Mr. Scratch

This image is a powerful visual representation of duality, identity, & the struggle between light & darkness. This captures Alan Wake’s internal battle with Mr. Scratch, his dark doppelgänger. The imagery, colour contrasts, & composition all reinforce the idea that Alan & Scratch are two sides of the same coin, mirroring Alan Wake’s overarching themes of psychological horror, self-destruction, & the blurred line between hero & villain.

1. Composition & Structure

• The image is split in two, with Alan Wake in the upper half in warm, golden light, & Mr. Scratch in the lower half, twisted & in darkness.

• The division is emphasised by the text in the middle:

- “Show me the Champion of Light”

- “I'll show you the Herald of Darkness” (written upside down).

• This presents a direct opposition: one entity cannot exist without the other.

• The mirroring effect a yin-yang dynamic, reinforcing the idea that light & darkness are intertwined, that Alan Wake is constantly struggling with his own reflection.

2. Alan Wake vs. Mr. Scratch: A Battle of Identity

• Alan Wake is a writer struggling for control over reality & his own mind.

• Mr. Scratch is his dark doppelgänger, a manifestation of his fears, suppressed desires, & the corrupting influence of the Dark Presence.

•This image visually reinforces their connection:

- The top half represents Alan Wake, a man holding onto light, trying to maintain control.

- The bottom half represents Mr. Scratch, a twisted, violent version of Alan, revelling in chaos.

The text in the middle:

• “Show me the Champion of Light” Alan Wake, the man fighting to bring light into the darkness.

• “I'll show you the Herald of Darkness”Mr. Scratch, the inevitable dark counterpart lurking beneath.

3. Symbolism of Light & Darkness in Alan Wake’s Story

The Champion of Light (Upper Half – Alan Wake)

• Alan appears determined, with piercing blue eyes & a solemn expression.

• He holds a golden goblet or chalice, a symbol often associated with divine favour, enlightenment, or power. In Alan Wake’s context, this represent his creative ability to rewrite reality.

• The background has warm, fiery hues, potentially symbolising hope, creation, or destruction, fire can illuminate, but it can also consume.

• His appearance is somewhat majestic, hinting at a heroic or mythic role, but the haunted look in his eyes suggests that even this "Champion of Light" is barely holding on.

The Herald of Darkness (Lower Half – Mr. Scratch)

• The mirrored figure is bloodied & worn, showing signs of battle or suffering.

• The background is deep, murky, & filled with skeletal figures, evoking decay, death, & corruption.

• Instead of divine golden light, this side is cloaked in shadows, torment, malevolence, or chaos.

• The reflection is not a perfect mirror, it’s distorted, more monstrous. This symbolise how corruption & darkness twist the original form, much like how Mr. Scratch is Alan’s darker, exaggerated reflection.

• The skeletal figures could represent the victims of Mr. Scratch’s violence, or the decay of Alan Wake’s own psyche as he loses himself in the Dark Place.

4. The Reflection as a Metaphor for Alan’s Struggle

• The mirrored composition reinforces that Alan & Scratch are two sides of the same person.

• Alan is desperate to remain the hero, but Scratch is always waiting, tempting him to embrace the darkness.

• It also plays into the lake vs. ocean symbolism in Alan Wake:

- If Cauldron Lake represents Alan’s subconscious, then this image is like looking into the water, one side is Alan’s self-image, the other is the lurking horror beneath.

- Just like a reflection on water, the more Alan stares into the darkness, the more distorted his own image becomes.

5. Psychological & Philosophical Implications: Jungian Shadow & Self-Destruction

• Mr. Scratch is Alan Wake’s Shadow Self, the parts of himself he refuses to accept.

• Alan’s biggest fear isn’t just losing control, it’s becoming the very thing he fights against.

• This mirrors classic horror & psychological thriller themes:

- The hero & the villain are the same person, just pushed to different extremes.

- Facing your own darkness is the only way to truly be free, but in Alan’s case, it might be too late.

• The text itself acts as a warning: The more you try to define yourself as the "Champion of Light," the closer you get to becoming the "Herald of Darkness."

6. My Final Thoughts: The Tragic Nature of Alan Wake

• This image perfectly sums up the conflict of Alan Wake’s story.

• It’s not just about a hero fighting a villain, it’s about a man fighting himself, questioning whether he can truly escape the darkness inside him.

• The tragedy is that even if Alan defeats Mr. Scratch, he may never be free.

• The duality of Champion of Light vs. Herald of Darkness isn’t just about Alan & Scratch, it’s about the duality in all of us.

"Show me the Champion of Light I'll show you the Herald of Darkness Lost in a never-ending night Diving deep to the surface"

#alan wake#alan wake 2#alan wake ii#alan wake spoilers#old gods of asgard#herald of darkness#mr scratch#ilkka villi#knowledge#alan wake fanart#sybolism

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

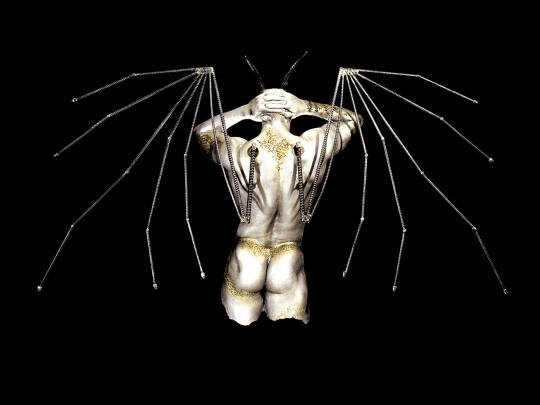

The Art of Manipulation Photography: Creating Magic Through Imagery

Photography has evolved significantly over the years, transcending the boundaries of traditional snapshots and embracing the realm of artistry and creativity. One captivating facet of photography is manipulation photography, a technique that allows photographers to craft imaginative and surreal images. In this article, we will delve into the world of manipulation photography, exploring what it is, its techniques, and the artistic possibilities it offers. If you're eager to unlock the magic of manipulation photography, visit photomanipulation.com for inspiration and resources.

What is Manipulation Photography?

manipulation photography, often referred to as "photo manipulation," is a form of digital art that involves the alteration and enhancement of photographs to create surreal, dreamlike, or otherworldly images. This genre goes beyond the conventional boundaries of photography, blending various elements, objects, and effects to produce striking compositions that tell unique visual stories.

Fundamental Techniques in Manipulation Photography

Image Compositing: One of the fundamental techniques in manipulation photography is compositing. This involves combining elements from multiple photos to create a cohesive and visually engaging scene. Photographers can seamlessly merge different objects, landscapes, or even people to construct entirely new worlds within a single image.

Digital Painting: Many manipulation photographers incorporate digital painting techniques to add depth, texture, and intricate details to their images. This process allows artists to enhance the mood and atmosphere of their creations, bringing their visions to life.

Color Grading: Manipulation photographers use color grading to manipulate the overall color scheme and tonal qualities of an image. This technique can evoke specific emotions and set the mood for the visual narrative.

Layering and Masking: Layering and masking are essential skills in manipulation photography. Photographers use layers to organize and control different elements within an image, while masking allows for precise adjustments and blending of these elements.

Special Effects: Special effects, such as light flares, particle effects, and surreal distortions, can transform a regular photograph into a captivating work of art. These effects add an ethereal quality to manipulation photography.

The Artistic Possibilities

Photo manipulation offers a limitless canvas for creative expression and It allows artists to explore their imaginations and transcend the boundaries of reality. Here are some of the artistic possibilities that manipulation photography offers:

Fantasy Worlds: Photographers can transport viewers to enchanting and otherworldly realms filled with mythical creatures, magical landscapes, and captivating adventures.

Emotional Storytelling: Manipulation photography enables artists to convey complex emotions, personal stories, and abstract concepts through visuals, making it a powerful medium for self-expression.

Surrealism: By distorting and manipulating images, artists can create dreamlike and surreal compositions that challenge the viewer's perception of reality.

Conceptual Art: Manipulation photography allows for the exploration of thought-provoking themes and ideas, making it a powerful tool for conveying social, political, or philosophical messages.

Personal Expression: Manipulation photographers often use their art to express their unique perspectives, pushing the boundaries of their creativity and pushing artistic frontiers.

Photomanipulation.com: Your Gateway to Artistic Exploration

If you're eager to embark on a journey into the captivating world of manipulation photography, look no further than photomanipulation.com. This platform serves as a hub for enthusiasts, artists, and photographers seeking inspiration, resources, and a sense of community.

Conclusion

Manipulation photography is a captivating art form that empowers photographers to create magic through imagery. With its versatile techniques and boundless artistic possibilities, it opens doors to a world of creativity and self-expression. If you're ready to dive into the world of manipulation photography, photomanipulation.com is your go-to destination for inspiration, guidance, and a vibrant community of like-minded individuals. Unleash your imagination, explore new horizons, and let manipulation photography be your canvas for artistic expression.

Blog Source URL:

#manipulation photography#photo manipulation#photo stock portraits#photoshop artist#photoshop manipulation#photoshop textures

0 notes

Text

Two Dragons Biting Each Other: Case File Compendium’s Alchemy

What’s something most danmei novels, some C-Dramas, Shakespeare’s works, several animes, and western fantasy series like The Witcher and A Song of Ice and Fire all have in common?

They’re all structured around the mythical process of alchemy!

I’ve talked extensively about alchemy in the American anime RWBY, as well as touched on it for other stories. It’s an allusive story structure that is extremely common worldwide yet rarely talked about--Harry Potter’s based on it, as are A Song of Ice and Fire, Lord of the Rings, and The Witcher. Shakespeare used it to write plays like Romeo and Juliet, Cymbeline, and A Winter’s Tale. Manga like BNHA have faint allusions to it, even if alchemy does not form the actual structure, and movies like Titanic also faintly reference it. It’s also very, very much a thing in most danmei novels I’ve read--all three of MXTX’s works use it, though MDZS and TGCF are more explicit about it--and in c-dramas like The Sleuth of the Ming Dynasty. Which is not really surprising because xianxia in particular is based on Taoism, from which Chinese alchemy also springs.

Meatbun heavily uses alchemy in Erha (literally the name of Sisheng Peak’s hall is Alchemy Heart Hall, Chu Wanning is a literal homonculus, etc; it’s not subtle and someday I’ll do a post on how the main ‘family’ of Sisheng Peak all have explicit imagery indicating they represent different stages in alchemy). This is to say, Meatbun is very clearly aware of what alchemy is and deliberately incorporating it into her works.

She’s also using it fairly heavily in Case File Compendium, which is interesting because alchemy is, well, most commonly used in fantasy stories. CFC has some sci-fi elements, but it’s largely set in a version of the real world, which makes it unusual but all the more interesting.

Western alchemy and Eastern alchemy are pretty similar, though the latter has five elements that interact differently than the west’s four elements. The goal of alchemy in either case is the Philosopher’s Stone, which is understood to be able to do three things: turn base metals into gold, create an elixir of life, and create a homonculus (a person out of something non-living). Chinese alchemy in particular generally focuses more on the elixir than anything else; in fact, it has its roots in Taoist medicine (fitting for Xie Qingcheng’s profession). Eastern alchemy also focuses on purification of the soul, which would influence Jung’s “spiritual” (psychological) alchemy theories, which apply to literary analysis better than they do in real life.

The elixir of life is a substance produced through repeated cycles of solve et coagula: dissolve the substance, coagulate it again, and with each cycle it becomes more and more purified. Through this process, an elixir that can cure any disease and sometimes grant immortality is produced. The process has different “stages” that can vary across works, but the main principle--solve et coagula--remains the same.

So let’s talk the specific symbolism and how it’s used thus far in CFC.

Mind, Heart/Spirit, Body

I talked briefly about this in my review for CFC, but in short, in an alchemical story most couples (romantic or otherwise) are “marked” as heart/spirit, mind/soul, and if there’s a third tagalong, they’re usually body.

So how are characters marked? Colors, traits, and sometimes elements. Mind is associated with white; heart with red. A heart character is almost always your protagonist and is brave to the point of foolishness, emotional, etc. A mind character is much more reserved. Think about, for example, five couples in danmei, and the colors schemes and traits associated with them:

Shen Qingqiu (white and green; reserved, plotting, struggles with empathy) and Luo Binghe (red and black; overly emotional crybaby)

Wei Wuxian (red and black; self-sacrificial) and Lan Wangji (white and blue, reserved, quiet, doesn’t say what he feels)

Xie Lian (white, self-sacrificial) and Hua Cheng (red; practical and somewhat amoral)

Mo Ran (blue and black; emotional and sacrificial) and Chu Wanning (white, reserved, intellectual)

Shen Zechuan (white, cold, intellectual) and Xiao Chiye (blue and black, hot-blooded, passionate)

As you can see, the markings don’t always align perfectly. Mo Ran’s and Xiao Chiye’s color schemes aren’t typical for heart characters, but for Mo Ran in particular it fits because he doesn’t start the story as a heart character, and for Xiao Chiye it kind of works because QJJ isn’t quuuuite as heavily based in alchemy as the others. Meanwhile, Xie Lian is white and Hua Cheng is red, but Xie Lian better fits as a heart character and Hua Cheng as a mind. The point of these couples all, though, is that each couple complements one another. Alchemy is fundamentally concerned with “the union of opposites”: heart vs. mind, sulphur vs. mercury, sun vs. moon, fire vs water. (Yes, union of opposites is connected to the concepts of yin and yang.)

A body character, when they exist, is often concerned with eating or with lust. (Actually I think you can make a solid argument that Xiao Chiye and Mo Ran are both body as well as heart.) In CFC, we have:

He Yu: passionate, interested in bloodlust, sacrificial, associated with heat and fire

Xie Qingcheng: intellectual, closed off, scientist, associated with cold and water (jellyfish, plus being a doctor; water=healing)

He Yu is clearly a body and heart character, while Xie Qingcheng is the mind character. But the point is that all three attributes are connected to one another and cannot be separated without the death of the others.

He Yu assumes that Xie Qingcheng was there to heal his mind, but in reality Xie Qingcheng was healing his heart when he was a child. He Yu keeps putting all his issues to his mental illness and compulsions, but his head isn’t the problem. Xie Qingcheng tells us this blatantly:

Meanwhile, Xie Qingcheng has been living with extreme restraint as a result of his own mental illness. He doesn’t allow himself to feel anything, not love for another person, not pleasure in sex, nothing at all. What kind of life is that? Well, honestly it’s akin to the life Rose DeWitt-Bukator lived in Titanic before she met Jack: it’s not a life at all. That Xie Qingcheng is mostly ashamed of the pleasure he felt in his body is because he refuses to allow himself to admit he has a body and a heart, and that his body might be alive, but without any feelings or love it’s not much of a life.

I spoke about this in my review, but again, as much as Xie Qingcheng and He Yu would like to think their bodies, hearts, and minds are entirely separate from one another, that’s not how this ish works in real life or in alchemy. Xie Qingcheng hurt He Yu by leaving him--hurt his mind, which he knew was a possibility and which is linked to He Yu’s body because the illness is physiological as well as psychological, and also He Yu’s heart, which he didn’t count on as much. He Yu hurt Xie Qingcheng’s body, but also his heart and his mind (it seems likely the fever was a result of a flareup of Xie Qingcheng’s illness).

Both He Yu and Xie Qingcheng are heartsick, mentally sick, and sick in body as well. Since they are already denying that each of these aspects of them are hopelessly tied together, they need to acknowledge that. If one part of them starts to heal, the other parts will as well.

The Process

There are varying steps to an alchemical process, but the most common appearances in literature are the three color-coded ones:

Black stage (nigredo)

White stage (albedo)

Red stage (rubedo)

(There’s a yellow stage between white and red that is almost always subsumed into red, and a “rainbow” stage/glimpse of a stage between black and white. Sometimes. These are not very common in literature.) The black stage is the “dark night of the soul.” It’s where sh*t gets dark, and there’s a focus on destruction and rotting. The white stage is for the purifying of what’s left from the destroyed matter in the black stage, and the red stage is when things finally combine and become the refined elixir.

These colored stages are then most often broken down into other steps, the most popular of which have seven or twelve steps (RWBY, for example, is following George Ripley’s twelve steps in his Magnum Opus to the literal letter). However, authors combine and mix steps as it suits a story with fair frequency, and I don’t think Meatbun is following a specific step order like RWBY or The Witcher.

But, most stages do start with 1) calcination, followed by 2) dissolution. Dissolve and coagulate, rinse, repeat. We have some very clear hallmarks of both to start the story: namely, the uses of fire and water. Fire refines, and water rinses away the impurities.

The hallmark of calcination in the black phase is fire. Let’s look at the first near-death encounter of Xie Qingcheng and He Yu: when they confront Lu Yuzhu. (Also pay attention to the colors described--it’s exclusively red, white, and black, with black as the overarching hue of the scene).

The entire building then goes up in flames, and Xie Qingcheng’s past is revealed to everyone.

Notably, this scene parallels the current scene, in that in each scene He Yu uses the near-death encounter to ask Xie Qingcheng something about himself. These scenes parallel each other because they are again examples of the process: coagulate, dissolve, try to get to the refined root of the matter--to the substance that really matters.

Not only does it parallel, but it’s occurring in a more refined manner: He Yu and Xie Qingcheng are alone, and this time Xie Qingcheng is telling He Yu the truth (some of it) on his own, instead of someone spilling it for him.

After the dissolution of He Yu’s image of Xie Qingcheng, we then see them spiritually separated (and physically). While I kind of doubt Meatbun is following Ripley, there is a passage of note in Ripley’s passage on separation:

Fire against nature must do your bodily woe, This is our Dragon as I you tell...

Which burns the body... If you will win our secrets, According to your desire.

Kind of reminds me of the imagery of the Club Scene, because He Yu thinks he’s going against his nature and against nature in general, but it’s actually his own secret desires. Plus, He Yu is a dragon, which... we’ll get to.

Then there’s conjunction, aka the primitive Chemical Wedding.

Chemical Wedding

The first chemical wedding is where the opposites meet and it usually doesn’t end well. It’s often violent and primative; alchemical drawings of this concept often incorporate animal characteristics onto the people involved if they’re drawn as people at all--often they are drawn as animals. Common aspects of a Chemical Wedding include stabbing each other, dismemberment, and the like. It’s not usually a sex scene, but it can be.

Like, here are some of the images of primitive chemical weddings:

Lovely. The last one is the best one, but they are still being compared to animals, so.

In CFC, it clearly is the Club Scene. It’s not a good scene. It’s violent and primative; in fact, to rub the point in, Meatbun has Xie Qingcheng call He Yu a beast numerous times.

Which brings me to our current scene. It seems too early for a final, elevated chemical wedding, but it is certainly another step in the process (and like I said I don’t think Meatbun is directly following a step-by-step process, but more the general gist). Perhaps if the former Club Scene is a chemical wedding to mark the Black Stage, this is one to mark the White.

Because guess what is also a hallmark of a chemical wedding and of the White Stage?

Being submerged in water together. Sometimes, it’s even specifically bathing together (think Jaime and Brienne in ASOIAF).

That’s why He Yu tries to imitate Xie Qingcheng by submerging himself in baths, but it doesn’t actually make him feel close to Xie Qingcheng, because Xie Qingcheng isn’t there. When they do end up submerged in water together, they’re drowning. So it’s still kind of violent and primative, but.

But, it is a more refined version of not just the calcination-fire sequence, but of the Club Scene.

While the events of the calcination, our first solve et coagula scene, led to He Yu’s dark night of the soul, the current one seems primed to be a rebirth symbol for He Yu. Enclosed space + water + one tiny opening; it’s hard to get any more obvious than that.

Dragons, Elixirs, and Nihlixirs

So you know how the Organization of Creepiness puts people in tubes? Well, the image of people trapped in flasks is, like, extremely common in alchemy. See:

Notice what’s also present? A monster/dragon.

Dragons are probably the number one animal associated with alchemy. They can be symbolic of the entire process (ouroboros eating its tale) and as such the dragon is associated with being dual-natured, which is pretty fitting for He Yu. He is at once willing to sacrifice his life for Xie Qingcheng, and then hurts him in an absolutely horrific way.

Dragons are also symbolic of of the prima materia, the material you start out with that will eventually turn into the elixir of life even if it’s rough going at first. It makes a ton of sense, then, for Meatbun to compare He Yu to a dragon. Lyndy Abraham writes that:

…the dragon is the lower, earthly self which the soul must learn to subdue and train, so that the higher self…may at last reign.

Which is kinda sorta exactly what Xie Qingcheng tells He Yu he must do, which makes Xie Qingcheng not only part of He Yu’s process but also his alchemist. Good luck dude.

Additionally, the union of two opposites (a chemical wedding) is referred to as “a most violent and bloody copulation in which two dragons kill each other.” According to Nicholas Flamel (the real one whom the Harry Potter character was based on) in his Heiroglyphs the two dragons are respectively defined by “heat and driness” and “cold and moisture.” In other words, He Yu and Xie Qingcheng, who is himself also a dragon... which the recent reveal about his own psychological ebola tells us.

But there’s more with the dragon symbolism. Flamel notes that these dragons “being united, and afterward changed into a quintessence... may overcome every thing Metallic, how solid hard and strong, soever it be.” This Quintessence is of course the elixir of life, and Lyndy Abraham notes that “this [quintessence] is called ‘dragon’s blood,’” which is relevant given the... exceeding focus on Xie Qingcheng and He Yu biting each other and blood being a part of that (not my thing but you do you boys), and also on He Yu’s blood toxin power.

So, essentially, Xie Qingcheng and He Yu’s love will somehow be used to give life not only to themselves but to everyone around them (final step in all processes is multiplication + projection aka it spreads beyond just one person or couple). Thus, they will together form the elixir of life.

But, there’s also sometimes a nihilixir. Instead of something that undergoes a process to become more and more refined and lifegiving, you can have something that induces someone(s) to descend into chaos and primitive instincts. For example, the One Ring in Lord of the Rings is a nihilixir. I think we have a pretty clear nihilixir present in CFC: RN-13. The number 13 kinda says it all, and in order for life to come, Xie Qingcheng and He Yu will have to destroy that drug and probably the Organization with it.

#case file compendium#cfc#cfc meta#xie qingcheng#he yu#hexie#he yu x xie qingcheng#meatbun doesn't eat meat#meatbun meta#alchemy#bing an ben#bab meta#cfc 87#cfc 88#cfc 90

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Habit of Art: How to write better stories, more consistently

"Art is the habit of the artist." - Flannery O'Connor

In 1955, Flannery O'Connor wrote a short story called "Good Country People," which is often remembered in lit classes as the story where a Bible salesman steals a woman’s wooden leg. Many consider it to be among O’Connor’s greatest works, and yet…

She wrote it in a single draft.

Without a plan or outline.

She just… wrote. Straight into the rabbit hole, and came out with a masterpiece.

How, you ask? (Because I sure wondered.)

According to O'Connor, she was able to pull off a nearly perfect first draft because she’d developed something called the "Habit of Art.”

Now, it's unlikely any of us will ever pull off a feat like O'Connor’s (which was a one-time occurrence even for her), but her Habit of Art really is something anyone can develop — and it’s the key to writing better stories, more consistently.

What exactly is the Habit of Art?

The idea is pretty straightforward, even if French philosopher Jacques Maritain (whom O'Connor referenced) makes it seem convoluted in Art and Scholasticism. Basically, he claims that when an artist reaches a certain point in their development, the creation of art becomes not just an active pursuit, but a natural inclination.

Art, in other words, becomes a habit — your subconscious naturally conspiring to help you craft meaningful stories whenever you sit down to write.

Sounds cool, right? But what does that look like in practice?

Well, to start, it's not like going into a trance and running on complete creative autopilot. As O'Connor explains in the essay "Writing Short Stories," the act of writing "is something in which the whole personality takes part — the conscious as well as the subconscious mind."

Art, in other words, is created through a collaboration between your conscious and subconscious — between logic and creativity. When you develop the Habit of Art, what you're really doing is developing and empowering the subconscious part of your creative process.

That, in turn allows your conscious mind to do less heavy lifting and act more as a guiding force — focusing and directing your creativity.

How to develop a Habit of Art

The process of developing any habit is simple: do something over and over consciously, until it becomes an unconscious action.

That's how professional musicians and athletes learn to perform consistently under pressure: they practice particular movements, breathing techniques, and thought processes over and over, until they learn to act that way every time, without thinking.

For writers it's the same. The Habit of Art isn't a single habit, so much as a collection of habits, skills, and instincts that come together in your subconscious to improve your writing. (Learn how I rapidly improved my craft with this mindset here.)

Here are key activities that help develop a Habit of Art:

Writing exercises. Just as musicians and athletes use exercises to turn specific skills into habits, so can writers use exercises to sharpen and habituate their approach to imagery, rhythm, voice, figurative language, etc. All you need to do is choose the skills you want to habituate, find a relevant exercise (or make your own), then do that exercise regularly, until it starts to feel more natural.

Reading and writing. This is a no-brainer, and it's common advice. To develop a natural instinct for storytelling, you need to be immersed in books — savoring the plot, language, and characters, while simultaneously breaking down how they work. You also need to be elbows deep in your own writing, mimicking and exploring and experimenting, so the craft seeps into your bones.

Observing the world. In O'Connor’s view, the Habit of Art is more than just a discipline: it's a way of seeing. And I agree. The best writers learn to habitually observe the world and find meaning in the little moments. So slow down, and take the time to notice the life passing you by. The more you do, the more your observations will start finding their way into your work.

Here’s the good news

If this all sounds overwhelming, I want you to take comfort in this: you already have a Habit of Art.

And it’s growing.

The Habit of Art isn’t some mythical switch you suddenly flip upon attaining artistic enlightenment. Instead, I believe it’s something you start developing early on, and its growth is a natural result of you reading, writing, and living.

So do those things. Read, write, and live thoughtfully — then watch as your Habit of Art develops.

I can’t promise it will help you write a single-draft masterpiece like it did for Flannery O'Connor.

But I know it will help you write some incredible stories.

— — —

For more tips on how to hone your craft, nurture meaningful stories, and stay inspired, follow my blog.

#writeblr#Writing tips#writing advice#writers of tumblr#writing#writerblr#writeblogging#writeblog#flannery o'connor#tips for writers#how to write

938 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Orphics, the Egyptian Book of the Dead, and Herodotus in Egypt

The Influence of Egyptian Funerary Practices on Greek Orphism : A Comparison of the Egyptian Book of the Dead and the Orphic Gold Tablets

Orphism is a historically controversial title due to the lack of a collective ancient group who called themselves "Orphic." On a basic level, Orphism is a branch of Dionysiac, or Bacchic, worship. The title of Orphism stems from the mythical man Orpheus who is at the heart of most Orphic theology. He appears as a musician, poet, and later, a spiritual leader. Orphism has come to be known as a religious and philosophical group, also called a mystery cult, in which followers lived an ascetic lifestyle in order to achieve happiness in the afterlife, and worshiped chthonic gods and goddesses, such as Persephone, in addition to their founder, Orpheus. What evidence we do have of Orphic traditions and groups are often only partial and from biased sources. One of the most important sources, the Orphic gold tablets, are a series of gold lamellae found in grave sites across Greece and Rome which appear to also advocate Orphic beliefs and eschatology. A close comparison of the Egyptian Book of the Dead and the gold tablets reveals numerous similarities not only in imagery, but especially in eschatological views of the afterlife. Although scholars still debate even the existence of Orphism, the Orphic gold tablets exist outside of any other tradition known in Greece. During the sixth century BCE, when the Orphic tablets began to be buried with deceased initiates, the Book of the Dead underwent a revival in Egypt, which included numerous additions and edits. This revival of interest included updates on many of the spells, updates which include Orphic imagery and influence. Contemporary Greeks such as Herodotus noted Orphic traditions existed in Egypt during this time period. Up until recently, scholars have struggled to compare these two traditions, but a renewed in interest in both subjects has opened the doors for a new wave of research. Through the comparison of these two traditions, we can come to understand the two cultures that produced them better, and pave the way for cross-cultural studies in the ancient world.

Vincensi, Elizabeth “The Influence of Egyptian Funerary Practices on Greek Orphism : A Comparison of the Egyptian Book of the Dead and the Orphic Gold Tablets“, Kalamazoo College.

Source: https://cache.kzoo.edu/handle/10920/28286

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ghidorah from Godzilla: King of The Monsters (2019)

When I saw this image in promotional materials, I thought it was a little heavy-handed to include the cross in the foreground, but now that I’ve seen the movie I get it. The movie’s scientists attempt to connect the monsters with imagery from ancient cultures--mythical beasts and so forth. But Ghidorah is so terrible that the references to him are unusually vague, as if he was meant to be forgotten, implying some ancient equivalent to nuclear semiotics. He stands apart from nature as we know it, and even the bizarre natural order proposed by the plot, where giant monsters like Godzilla are ecologically vital.

All of this casts him as the serpent in a Chaoskampf myth, akin to Leviathan, Jormungandr, Vritra, and Yamata no Orochi. Accounts of these creatures tend to be sparse, as their role is little more than to be slain by gods as part of the work of beginning or ending the world. In this context, Ghidorah is not merely a demonic figure opposing a particular interpretation of God, but a chaos monster opposing the very concept of creation itself.

The cross can therefore represent a broad range of fundamental ideas imperiled in this scene--the civilization and technology that placed it there, the philosophical/historical context that gives it meaning, the hope it is designed to instill, and even the divine order it is intended to revere.

669 notes

·

View notes

Text

Discussion: Atlantis Retellings

Introduction: Explaining Atlantis

The nation/city/island of Atlantis was used by Plato as an allegory in one of his works, and has since become incredibly popular and widely known. Though many of us have not read the original myth, most are familiar with the idea of Atlantis: a nation of great learning and pride that angered the gods and was subsequently sunk beneath the waves as punishment. Atlantis as ruin, and as a hidden civilization, has captured the imagination of many writers, archaeologists, historians, philosophers, and others. Ultimately, it was a fictional place, but many have interpreted Plato’s inspiration as coming from a real place due to its popularity among the many flood myths in history.

There are a lot of proposed locations for the mythical Atlantis, but also Atlantis has become a term for lost civilizations that may have been flooded/sunken to the ocean floor. As a maritime archaeologist, my peers largely use Atlantis as an easy explanation when discussing seafaring civilizations whose material culture may be on the seafloor and undiscovered–often we don’t literally mean the society of Atlantis from Plato’s work, but want to inspire the imagery of ruins and lives cut short by a tragic flood.

The Popularity of Atlantis

The legend of Atlantis has clearly captured our minds for hundreds of years, I mean, we’re still talking about it! I as at a beautiful museum exhibit at the Moesgaard Museum in Denmark just about two years ago and an exhibit about the general history of the area even began by telling the myth of Atlantis and hypothesizing where the city may have been located. One of the first books I reviewed on this blog was an adventure novel focused on discovering a Mycenaean Atlantis. The idea of an advanced human civilization living long before us is captivating, it taps into the idea that human beings have always been capable of the greatness we imagine they are. But the story is literally an allegory for hubris and the dangers that come with being too proud to see the signs of the world crumbling around us.

In modern popular culture, Atlantis pops up in a few core representations. There’s the Disney movie, Atlantis: The Lost Empire, as well as its sequel film. There was a brief BBC series about Atlantis produced following the show Merlin (by some of the same writers as well) that took a more Greek inspired approach. Lots of time travel, fantasy, and science fiction shows approach Atlantis in one way or another–even looking into similar myths and cultural influences from other flood myths. Atlantis appears in countless paintings, songs, poems, literary works, and more. Ayn Rand, J.R.R. Tolkein, C.S. Lewis, H.P. Lovecraft, Neil Gaiman, Eoin Colfer, K.A. Applegate, and Marvel and DC Comics have all made allusions to Atlantis from hints that Atlantis exists in the canon of their fictional worlds to confirmed characters and places from Atlantis.

Key Factors

For an Atlantis retelling, you’ve got a few basic factors you need to have covered to really qualify. First and foremost, the setting must be some sort of ancient city with a developed society. This is up to individual interpretation, and the source of cultural inspiration varies; Greco-Roman inspired tends to be popular, as well as a sort of cultural basis for several ancient cultures, drawing inspiration from other civilizations near the Mediterranean. Once the setting is developed, the factor of hubris comes into play. Some stories approach the idea of Atlantis as a colonizing war state, finally inspiring its enemies to rise up against their advanced warfare. Others use divine intervention, portraying the Atlanteans as scholars who eschew the gods and are punished for it.

Ultimately, most Atlantis retellings focus on the post-flood city. They focus on outside explorers who rediscover the mythical lost city/civilization, or at least piece together the cultural mystery of Atlantis and discover its final resting place. Atlantis is most often portrayed as a still-surviving civilization, one that has hidden from the rest of the world for one reason or another. More “realistic” portrayals instead explore the idea of finding the ruins of Atlantis, rediscovering some of the advanced technology and cultural artifacts left behind. For stories that do take place pre-flood the story tends to focus on the build up to the flood, exploring the idea of hubris and determining what part of the collapse of Atlantis is the fault of the Atlanteans.

Final Thoughts

The original story of Atlantis had a purpose, and the way the myth has grown and captivated others for so long indicates that there’s still plenty of merit to it. Human beings continue to obsess over the idea of a highly sophisticated and advanced civilization calling down the wrath of the gods and being buried under the waves. I think some retellings have a lot of merit when they explore the consequences of the fate of the city for individuals, especially depending on what the Atlanteans ignored that could have saved them.

Do you have a favorite retelling of the Atlantis myth?

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Get those tin foil hats ready to go!

The 10 greatest conspiracy theories in rock

By Emma Johnston

In a world where fake news runs rampant, rock'n'roll is not immune to the lure of the conspiracy theory. These are 10 of the most ludicrous

Conspiracy theories, myths and legends have existed in rock’n’roll for as long as the music has existed, stretching all the way back to bluesman Robert Johnson selling his soul to the devil at the crossroads in exchange for superhuman guitar skills, fame and fortune.

There are those who believe Elvis Presley and Jim Morrison live on, others who think the Illuminati control the world through symbolism in popular culture, and plenty of evangelical types with their own agendas trawling rock and metal songs for secret messages luring the innocent to the dark side.

Let us take a look, then, at rock’n’roll conspiracy theories ranging from the intriguing to the ludicrous, as we try to separate the truth from the codswallop.

Lemmy was in league with the Illuminati

Few men have ever been earthier than Lemmy, but one conspiracy theorist claims that the Motorhead legend didn’t really die in December 2015, instead “ascending into the heavenly realm” after making a “blood sacrifice pact” with the Illuminati.

A “watcher” of the mythical secret society some believe are running the world – despite evidence that is at best flimsy, at worst straight from The Da Vinci Code author Dan Brown’s discarded notebooks – told the Daily Star: “Lemmy signed up for the ultimate pact – he signed his soul to the devil in order to achieve fame and fortune.”

While we can only imagine what the great man would have to say on the matter, there’s one word, in husky, JD-soaked tones, that we can just about make out coming across from the other side: “Bollocks.”

Paul McCartney died in 1966

As you might expect from the most famous band that has ever existed, there are enough crackpot theories about The Beatles to fill the Albert Hall. From John Lennon’s murder being ordered by the US government, who, led by Richard Nixon, suspected him of communism (the FBI actually did have a file on Lennon, but the story is spiced up by the man behind murderlennontruth.com, who apparently believes author Steven King was involved due to, uh, looking a bit like Mark Chapman) to Canadian prog outfit Klaatu being the Fab Four in disguise, there are plenty of tall tales more colourful than a Ringo B-side.

The most enduring, though, is the notion dreamt up by some US radio DJs that Paul McCartney died in a car crash in 1966 and was replaced by a lookalike. They came to this conclusion having studied the cover of Abbey Road – McCartney’s bare feet on the zebra crossing apparently symbolising death, while others found “evidence” in the album’s opaque lyrics. There were a lot of drugs in the 60s.

Gene Simmons has a cow’s tongue

It’s easy to see why all kinds of far-fetched stories sprung up when Kiss first took off in the 1970s. The fake-blood-spitting, the fire, the demon-superhero personas – middle America clutched its pearls and word spread that these otherworldly weirdos’ moniker stood for Knights In Satan’s Service. Spoiler alert: it doesn’t.

It was Gene Simmons’ preposterous mouth that got the nation’s less voluminous tongues wagging though. So long and pointy is his appendage, and so often waggled at his audiences (whether they asked for it or not), that eventually the rumour spread around the world’s playgrounds was that he’d had a cow’s tongue grafted onto his own. The bovine baloney is, of course, bullshit, but Simmons has admitted it's one of his favourite Kiss urban myths.

Supertramp predicted 9/11

The Logical Song may be Supertramp’s calling card, but one man in the US stretches common sense to the limit having come to the conclusion that the artwork for their 1979 album Breakfast In America gave prior warning of the terrorist attacks on New York on September 11, 2001.

Look at the album cover – painted from the perspective of a window on a flight into the city – in a mirror, and the ‘u’ and ‘p’ band’s name appears to become a 911 floating above the twin towers, while a logo on the back features a plane flying towards the World Trade Center.

So far, so coincidental, but when our intrepid investigator falls down a rabbit hole of Masonic interference, strained Old Testament connections (“The Great Whore of Babylon – Super Tramp”), and the title Breakfast In America reflecting the fact that the planes crashed early in the morning, things get really tenuous.

It’s fair to say it’s unlikely a British prog-pop band had prior knowledge of the terrorist attacks 22 years before they happened. But maybe Al Qaida were really big fans.

Stevie Wonder can see

Stevie Wonder is a genius. That fact is not up for dispute. The soul/jazz/funk/rock/pop legend was born six weeks prematurely in 1950, and the oxygen used in the hospital incubator to stabilise him caused him to go blind shortly afterwards. But his love of front-row seats at basketball games, the evocative imagery in his songs, and the fact that he once effortlessly caught a falling mic stand knocked over by Paul McCartney (who, let us reiterate, did not die in 1966) has caused basement Jessica Fletchers to muse that he’s faking his blindness as part of the act.

Wonder himself, a known prankster, has great fun with his status as one of the world’s most famous vision-impaired musicians. In 1973, he told Rolling Stone: “I’ve flown a plane before. A Cessna or something, from Chicago to New York. Scared the hell out of everybody.”

Dave Grohl invented Andrew W.K.

When Andrew W.K. first broke through in the early 2000s, dressed in white and covered in blood, his mission was serious in its simplicity: the party is everything. He took his message of having a good time, all the time, to levels of political fervour. But rumours of his authenticity have been doing the rounds from the start.

Reviewing WK’s first UK show at The Garage in London, The Guardian’s Alexis Petridis wrote: “One music-biz conspiracy theory currently circulating suggests that Andrew W.K. is an elaborate hoax devised by former Nirvana drummer Dave Grohl.”

As time went on, the theory gained traction – Grohl was believed to be the mysterious Steev Mike credited on the debut album I Get Wet. And as W.K.’s style changed over subsequent records, and his own admission that there were legal arguments over who owns his name, whispers began that he wasn’t even a real person – he was a character, played by several different actors, an attempt to create the ultimate Frankenstein’s frontman.

"I'm not the same guy that you may have seen from the I Get Wet album," W.K. said in 2008. “I don't just mean that in a philosophical or conceptual way, it's not the same person at all. Do I look the same as that person?" The jury is out, but if this is a great white elephant concocted just for the sheer hell of it, we kind of want this one to be true.

Jimi Hendrix was murdered by his manager

An early victim of the 27 club, the death of Jimi Hendrix was depressingly cliched for a man so wildly creative: a bellyful of barbiturates led to him asphyxiating on his own vomit, according to the post-mortem. But in the years following the grim discovery at the Samarkand Hotel in London on 19 September 1970, a different theory was offered by the guitarist’s former roadie, James “Tappy” Wright.

In his book Rock Roadie, Wright claims Hendrix was murdered by his manager, Michael Jeffery, who he says force-fed his charge red wine and pills. The motive? He feared he was about to be fired and was keen to cash in on the star’s life insurance. One thing we do know for certain is Jeffery won’t be able to give his version of events, as he was killed in a plane crash over France in 1973.

The 50th anniversary of Hendrix's tragic passing was "celebrated" with the release of Hendrix and the Spook, a documentary that "explored" his death further and was described by The Guardian as "a cheaply made mix of interviews and dumbshow dramatic recreations by actors scuttling about flimsy sets in gloomy lighting." Sounds good.

Courtney killed Kurt

Courtney Love is no stranger to demonisation from Nirvana fans. When Hole’s second album, the searing, catchy, feminist, witty, aggressive, vulnerable and unflinchingly honest Live Through This was released, days after Kurt Cobain’s death, rumours almost immediately started up that Love’s late husband wrote the songs. That was insulting and sexist enough, but nowhere near as damaging as the conspiracy theory that Love hired a hitman to kill Cobain amid rumours they were about to divorce.

After Cobain’s first attempt to take his own life in Rome, the Nirvana frontman was eventually convinced to go to rehab following an intervention by his wife and friends. He ran away from the facility, and the private investigator hired by Love to find him, Tom Grant, eventually became the source of the idea that Love and the couple’s live-in nanny Michael Dewitt were responsible for Cobain’s death shortly afterwards.

His claims, made in the Soaked In Bleach documentary, include the notion that Cobain had too much heroin in his system to pull the trigger of the shotgun, and that he believed the suicide note was forged.

People close to Cobain (and the Seattle Police Department) have refuted the theory, including Nirvana manager Danny Goldberg: “It’s ridiculous. He killed himself. I saw him the week beforehand, he was depressed. He tried to kill himself six weeks earlier, he’d talked and written about suicide a lot, he was on drugs, he got a gun. Why do people speculate about it? The tragedy of the loss is so great people look for other explanations. I don’t think there’s any truth at all to it."

The CIA wrote The Scorpions’ biggest hit

Previously synonymous with leather, hard rock anthems and some very questionable album artwork, West Germany’s Scorpions scored big with Wind Of Change, a power ballad heralding the oncoming fall of the USSR, the end of the Cold War, and a new sense of hope in the Eastern Bloc.

In a podcast named after the 1990 song, though, Orwell Prize-winning US journalist Patrick Radden Keefe follows rumours from within the intelligence community that the song was actually written by the CIA, as propaganda to hasten the fall of the ailing Soviet Union via popular culture.

“Soviet officials had long been nervous over the free expression that rock stood for, and how it might affect the Soviet youth,” Keefe is quoted as saying. “The CIA saw rock music as a cultural weapon in the cold war. Wind of Change was released a year after the fall of the Berlin Wall, and became this anthem for the end of communism and reunification of Germany. It had this soft-power message that the intelligence service wanted to promote.”