#ones that spoke to me in english out of excitement and not condescension

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Here is my experience as an American who traveled internationally a lot. For context, I have worked previously as a flight attendant and an Au Pair. My best friends live throughout Europe and Canada. *TW vague SA mention.

One time I had to order an Uber in Argentina, and the driver rolled down his window, took one look at us, realized pretty quickly we were American women alone, and drove away immediately leaving us stranded. Later in the week we had rented a car that broke down on us in quite a dangerous place off the highway. People stared at us from their open windows, and the car rental place even hung up on us multiple times while we were sitting there terrified with our doors locked and sweltering in a 100 degree car.

Once I attended a lecture in a London museum, they called on me because I wanted to ask a genuine question about the history they had a PHD in. They proceeded to make fun of me and my American qualities in front of the entire crowd. I went to a drag show the following night where the Drag Queen on stage proceeded to do the exact same thing because my friends and I (who were Scottish and Belgian by the way) were kind and remained in the front row the whole show while everyone else trickled out early.

I lived as an Au Pair in Italy for 3 months which required me to travel alone a lot, as someone who was very obviously not Italian I quite often got a lot of looks even though I am quiet and pretty good and doing what I need to do without standing out. Once I was on the train at night alone because the fellow Au Pairs I had met locally got off on stops before me. I was literally SA’d on the train with a few other people on it. I got off at my stop and the man proceeded to follow me off the train. I pretty much ran home despite making eye contact with multiple people on the way and them whispering to each other about it. I was too flustered and panicked to be able to speak in Italian at that moment. Nobody approached me so I managed to lose the man in the crowd and walked home alone in the dark on the phone with my friend countries away, hoping I wasn’t about to be murdered.

I usually understand. Every time I meet someone in another country we have the exact same conversation about where I am from. They’re usually amused. I am a long way from home, a place where people notoriously don’t care enough to travel. I am quiet and nondescript while American tourists obviously are always obnoxious and loud. It’s kind of funny from their perspective, and I get it. At a certain point though I get very frustrated. Here I am as an American trying to be respectful, trying to learn about cultures other than my own, trying to be thoughtful and unbiased- but a lot of the time I am not given the chance.

Then at some point, the dislike of America goes beyond annoyance and gets downright malicious. I, as an American, hate America. However, I hate America out of compassion. I want the people who live here to not be traumatized just by existing. A lot of us are fighting to try and make things better, and to assume otherwise is ignorant. To say we deserve to suffer, is malicious. If my suffering even outside of America is flat out ignored, that is malice not just in theory but in action, and frankly I am getting tired of it. Dehumanizing any person, or population is dangerous. It being the U.S. doesn’t magically make it funny or okay. It’s the generalization that is the problem.

#granted i met outliers in every single on of these countries#ones that spoke to me in english out of excitement and not condescension#and of course most of my friends live there and have never left europe#but have empathy#it's just hard not to feel like it's a small minority#alycia rants#tw sa

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Room For Three | Deleted Scenes

Hi friends! Have you read my fic Room For Three? If not, and you’re looking for Holden/Amos/Naomi fic, go check that out first, because it’s better than this.

The following are a few deleted scenes from Chapter 20. These scenes did not actually occur in the universe of the fic. They were deleted in part because they weren’t relevant to anything, so they added too much superfluous bulk to an already superfluous and bulky fic, and in part because I wasn’t very confident with my characterization of Camina’s family or the way I communicated their dialect. I do love the idea of giving Drummer some closure with Naomi, though I don’t think that Room For Three is the place to explore that concept. That being said, this was a fun little scene, so I’d like to share!

Very mildly NSFW text below. This is from a rated E fic, but is not explicitly sexual. CW recreational drug use (marijuana)

“I wouldn’t want to impose,” said Naomi into her hand terminal. The small window in the corner reflected her own image, alone in the room while Jim either finished up his therapy or got started on his way to lunch with Fred, and Amos journeyed to pick up food for the two of them. The larger window, the focus of her attention, showed Drummer’s full face and half of another woman’s, whose shoulder acted as a pillow for Camina’s tilted head. Her friend looked more at peace than Naomi had ever seen her.

“Nah, we insist. Whole crew will be happy to meet The Naomi Nagata. Plus, your Earther boys obviously need a lesson in family. Double date.”

“Is it still called a double date if there’s nine people at the table?”

“Nonuple date, then. Come. Josep good cook, Bertold good advice, Oksana good to look at,” she said. The body next to her stuck out an elbow in playful defense, and a loving giggle filled the speaker. “Good in bed, too,” Camina added to appease her, and they both laughed together.

“Alright, alright. I guess I’d rather get polyam lessons from you lot than from Jim’s eight parents.”

“Soyá. One Holden is more than enough for me.” Naomi didn’t say it, but she agreed. The Holden family was a lot to handle. She knew there might be a discussion with them in her future, in which she and Amos would undoubtedly have to stand under their mild-mannered scrutiny and well-meant condescension, but she hoped to put it off as long as possible.

“Be nice to him tonight,” Naomi implored, Camina rolled her eyes.

“To ta ge im, bosmang. I will try. No promises ‘bout Serge though. Discriminate, im does.”

“Ah, pashang fong, ‘Mina,” a man’s voice bellowed, the pejorative softened by his loving tone. His head appeared on Naomi’s device, upside down at the top of the frame. “Mi behave, promise.” They all three laughed together, a contagious sound that put a smile on Naomi’s face.

Camina’s family was as affectionate as it was functional, and any jealousy was squandered as soon as it sprouted through open networks of communication. They didn’t all sleep in the same bed, or all have sex at the same time, or spend every waking hour together, the six of them, but they loved each other equally just the same. They didn’t all keep score of their ‘wins’ and ‘losses’— surely Michio didn’t feel left out if Oksana got milkshakes with Josep one day, and Drummer didn’t pout if Serge chose to shower with Bertold instead of her. They found a balance together, where everyone was included, even in the moments when they weren’t. They’d be good role models.

“Alright, we’ll be there,” Naomi said, excitement written on her face. When the phone call was over, she turned her attention to the door. Amos was taking longer than anticipated. She supposed she’d have to find some way to occupy herself until he returned.

***

Josep’s cooking was so spicy that it felt like a targeted attack. Holden was the only one who seemed to notice— which only furthered his suspicions that it was a deliberate poisoning— though he knew he was just wimpier than anyone else in the room. Otherwise, Holden, Naomi, and Amos were welcomed warmly into Drummer’s home like members of the family.

They each had their own unique flavor of advice, ranging from categorically unhelpful to actually something to think about, spoken in different degrees of broken English or part-English part-Belter. Holden appreciated the great effort they went to to be understood by him. They probably had very little use for pure English in their day-to-day lives, and the grammar of Lang Belta was very different, more efficient. It made some of their translations a little hard for Holden to process, but if they could make the effort, so could he.

“Da pashang gut?” Serge asked. In the time it took Holden to decide if he was comfortable answering whether they had good sex, Amos and Naomi had already given their yesses. “Gut. The rest figure itself out.”

“That’s terrible advice,” interjected Michio.

“Work for me an’ Josep this morning,” he shrugged. “Take too long in shower. Mi angry. Join him in shower, mi na so angry.” Michio rolled her eyes.

“It’s not about sex,” she said. “You can have good sex and no love for each other.”

“Like in Camina dream about Holden,” Serge contributed. Holden didn’t know what to do with that information. Naomi seemed to like it.

“I’ve had that dream,” Amos added. Holden elbowed him.

“Sure, like that,” dismissed Michio. “It’s not about sex; it’s about trust. You trust your family will never hurt you on purpose?” she asked. The three of them nodded. “You forgive your family when they make a mistake?” she asked. They nodded. “Then you can forgive your family for anything.” That was pretty solid advice, but nothing Holden didn’t already know. They were good at forgiving each other. Had practice.

“How do you keep everything…” Holden searched for the word, “...equal?”

“Equal? Who cares equal?” replied Bertold. “Not equal. Camina in charge. Like Naomi for you.”

“Naomi’s not—” Holden said, then backed down. It was true enough.

“Ya. No need for equal.”

“Is there ever jealousy? Like, if you spend more time with one person than another.” A couple of them, including Amos, looked at him like that was the stupidest question ever asked.

“That’s baby shit, kopeng,” Bertold said. “Need comfort, ask Oksana. Need tough love, ask Camina. Need fix problem, ask Michio. Need laugh, ask Josep. Need blow job, ask Serge.”

“Hey,” Serge defended. “I’m funny, too.”

“Ya, baby,” Bertold consoled. “I just simplify for explain. Different for others, or depend on the day. Point is, na equal. Need comfort four time, tough love one, then go Oksana four time, Camina one. ‘Mina no cry ‘bout it. Because adult. Knows mi love im the same.” Drummer smiled at him. Holden had never seen Drummer smile as bright or as often as he had that night. “End of day, eat dinner as family, go bed happy.”

“Huh,” said Holden. “That… makes a lot of sense, thank you.”

“Try not to think so hard, Jimmy,” said Drummer. “Have some cake. Not so spicy.”

“Gee, thanks.��

***

The third or fourth time it was passed to her, Naomi took another long, luxurious puff off of Drummer’s vaporizer. She tried to pass it behind her to Jim (whose lap she didn’t think she’d been sitting in when Camina first pulled out the device) but he declined as always. Naomi presumed the captain was afraid of what slutty business he might get up to under the influence of high-grade synthetic cannabis in a room full of incredibly hot people. She couldn’t blame him, but it wouldn’t stop her from having a good time. Amos also clearly had no such reservations.

“So,” he said between two smaller puffs (Earthers with their puff, puff, pass bullshit), “what’s the sex like?”

“Amos, you can’t just ask people that,” Jim scolded. In rebuttal, Amos took his second puff and blew it in Jim’s face. Soberly, Naomi might’ve been on Jim’s side of that argument, but she was high and curious. Amos looked at Serge, who seemed the most likely to answer the question rather than flip him off.

“All six of you screw together, or is it a Noah’s Ark kinda deal?” Amos asked. Serge shrugged.

“Sometimes all six, sometimes three, sometimes two,” he said.

“Maybe sometimes nine,” added Josep lewdly, eyeing the three guests. Amos smiled salaciously, while scattered laughter filled the room. Camina cleared her throat and shook her head.

“What did I say?” she chided.

“Dinner, not orgy,” Josep said.

“Don’t see why it can’t be both,” said Amos. Jim elbowed him.

As her Earther lovers mingled with her Belter friends, new and old, Naomi felt a sense of wholeness. Her worlds were colliding— this time in a harmonious way, not an explosive one. She didn’t know if it was the THC in her lungs or the love in her life, but she was on top of the world.

Michio was teaching Amos and Jim an old Belter card game when Naomi was overcome with a powerful urge to speak privately with Camina. Several faces quirked suggestively as she pulled her friend from the mass of cuddling bodies on the living room floor. Apparently Amos wasn’t the only one with preconceived notions about their friendship. She ignored them and guided Camina into the next room, which only happened to be the bedroom.

“Don’t think I’ve ever seen you this happy, Camina,” she said once they were in another room. Camina hummed and nodded, the corners of her mouth quirking up into a small smile. The weed seemed to unburden her considerably, though a deeper happiness radiated from her even before they’d smoked. Her hair was down, and it felt to Naomi like a metaphor.

“Don’t think I ever have been,” she said. Naomi took her hand and squeezed it, beaming with pride. Camina’s expression soured almost imperceptibly; her smile was still present, though it spoke of an old, tired sadness, or perhaps just a more reluctant version of joy. “Spent a long time wanting something I could not have.” She looked Naomi up and down, and the message was heard loud and clear. That bitter-sweet smile. The harbinger of closure.

“Ended up with something better, no?”

“Think so,” Camina answered. Her eyes widened as she asked, and there was a youthfulness in her face that Naomi hadn’t seen before, like a child seeking approval. Naomi didn’t think Camina needed her approval, but she gave it readily.

“I know so. Oksana looks at you like you painted the stars in the sky. You deserve that.”

“Same way Jimmy looks at you.”

“Same way Amos looks at my boobs,” Naomi countered. They both laughed. “You deserve to be happy, Camina Drummer. Are you?”

“Ya, Naomi Nagata. Have everything I ever wanted, and more. Could not have imagined having something this good until it happened.”

“I know what you mean,” Naomi said wistfully, thinking of Amos and Jim.

“You happy, too?” Camina asked.

“Ya,” answered Naomi, easily and honestly. Have everything I ever wanted, and more. “Mi xush.” Naomi pressed her forehead to Camina’s, and they shared their happiness together for a moment.

“Gut.”

“So... what’s this dream you had about Jim?”

“Oh hush.”

***

“You think they’re fooling around?” Amos asked the group of people whose names he didn’t know. Holden elbowed him for the third time that night. “Bug, at some point, you’re gonna have to realize jabbing me in the ribs ain’t gonna stop me from sayin’ shit.”

“What will?” Holden asked. Amos didn’t answer, just pointed his eyes down at Holden’s crotch, and figured he got the message when he received yet another nudge to his side. He laughed, took his turn in the card game, and hit the vape when it came around again.

“Could I ask you something, big man?” asked the guy with the triangle tattoos beside his eyes. Amos shrugged his permission. The guy took a second to say anything else, like he was trying to word his question. He whispered something to the man at his side.

“Ah,” the second man said, “wants to know if you have Earther cock.” Amos didn’t know what that meant. “You know, like…” he gave an inscrutable gesture, like jerking off, but not quite. “No skin.”

“Josep,” came a scolding female voice. Amos didn’t mind.

“Oh. Yeah, I’m circumcised.” The two men, one of whom must’ve been Josep, not that Amos would retain that information, seemed fascinated by that. He was about to ask if they wanted to see it when Naomi and her girlfriend came back. Another time, then.

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

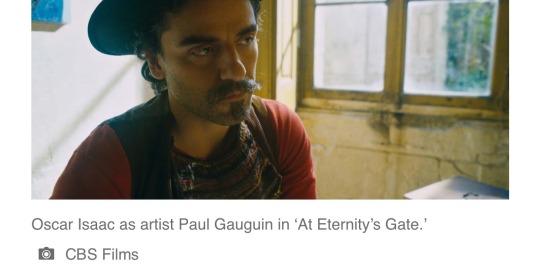

Oscar Isaac in the role of painter Paul Gauguin is trouble you see coming from a mile away—the kind you live to regret falling for anyway.

He’s a holier-than-thou painting bro with a “slightly misanthropic” streak (Isaac’s generous wording), eyes glinting with disgust in his first close-up. Pipe in one hand, book in another, dressed all black save for an elegant red scarf, he slams a table and shames the Impressionists gathered around him: “They call themselves artists but behave like bureaucrats,” he huffs after a theatrical exit. “Each of them is a little tyrant.”

From a few tables away, another painter, Vincent van Gogh, watches in awe. He runs into the street after Gauguin like a puppy dog.

Within a year, a reluctant Gauguin would move in with van Gogh in a small town in the south of France, in the hope of fostering an artists’ retreat away from stifling Paris. Eight emotionally turbulent weeks later, van Gogh would lop off his left ear with a razor, distraught that his dearest friend planned to leave him for good. He enclosed the bloody cartilage in wrapping marked “remember me,” intending to have it delivered to Gauguin by a frightened brothel madam as a bizarre mea culpa. The two never spoke again.

Or so the last two years of Vincent van Gogh’s life unspool in Julian Schnabel’s At Eternity’s Gate, itself a kind of lush, post-Impressionistic memoir of the Dutchman’s tormented time in Arles, France. (Not to mention artistically fruitful time: Van Gogh churned out 200 paintings and 100 watercolors and sketches before the ear fiasco landed him in an insane asylum.)

Isaac plays Gauguin like an irresistibly bad boyfriend, a bemused air of condescension at times wafting straight into the audience: “Why’re you being so dramatic?” he scoffs directly into the camera, inflicting a first-person sensation of van Gogh’s insult and pain.

youtube

Yet in the painter’s artistic restlessness, Isaac, 37, sees himself: “That desire to want to do something new, to want to push the boundaries, to not just settle for the same old thing and get so caught up with the minutia of what everyone thinks is fashionable in the moment.” He talks about “staying true to your own idea of what’s great.” He talks about “finding something honest.”

From another actor, the sentiment might border on banal. But Oscar Isaac—Guatemalan-born, Juilliard-trained and, in his four years since breaking through as film’s most promising new leading man, christened superlatives from “this generation’s Al Pacino” to the “best dang actor of his generation”—might really have reason to mean what he says. He’s crawling out the other end of a life-altering two years, one that’s encompassed personal highs, like getting married and becoming a father, and an acutely painful low: losing a parent.

He basked in another Star Wars premiere, mined Hamlet for every dimension of human experience, and weathered the worst notices of his career with Life Itself. Through it all, he says, he’s spent a lot of time in his head—reevaluating who he is, what he wants, and what matters most.

Right now, he’s aiming for a year-long break from work, his first in a decade, after wrapping next December’s Star Wars: Episode IX. “I’m excited to, like Gauguin, kind of step away from the whole thing for a bit and focus on things that are a bit more real and that matter to me,” he says.

Until then, he’s just trying “to keep moving forward as positively as I can,” easing into an altered reality. “You’re just never the same,” he says quietly. “On a cellular level, you’re a completely different person.”

When we talk, Isaac is in New York for one day to promote and attend the New York Film Festival premiere of At Eternity’s Gate. Then it’s back on a plane to London, where Pinewood Studios and Star Wars await.

Episode IX, the last of Disney’s new Skywalker trilogy, will see Isaac reprise the role of dashing Resistance pilot Poe Dameron, whose close relationship with Carrie Fisher’s General Leia evokes joy but also melancholy after Fisher’s untimely passing.

Each film was planned in part as a celebration and send-off to each of the original trilogy’s most beloved heroes: in The Force Awakens, Han Solo (Harrison Ford); in The Last Jedi, Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill); Fisher, meanwhile, had hoped to save Leia’s spotlight for last but passed unexpectedly long before filming began. Director J.J. Abrams, returning to close the trilogy he opened with Episode VII, has since said that unseen footage of Fisher from that previous film will ensure the General appears, however briefly.

For his part, Isaac promises the still-untitled ninth film will pay appropriate homage to Leia—and to Fisher’s sense of fun. “The story deals with that quite a bit,” he says. “It’s a strange thing to be on the set and to be speaking of Leia and having Carrie not be around. There’s definitely some pain in that.” Still, he says, compared to the first two installments, “there’s a looseness and an energy to the way that we’re shooting this that feels very different.”

“It’s been really fun being back with J.J., with all of us working in a really close way. I just feel like there’s an element of almost senioritis, you know?” he laughs. “Since everything just feels way looser and people aren’t taking it quite as seriously, but still just having a lot of fun. I think that that energy is gonna translate to a really great movie.”

Fisher’s absence is felt keenly on set, Isaac says. As if to reassure us both, however, he reiterates: “It deals with the amazing character that Carrie created in a really beautiful way.”

Two months after Fisher’s death, Isaac’s mother, Eugenia, passed away after an illness. A month after that, the actor married his girlfriend, the Danish documentarian Elvira Lind. Another month later, the couple welcomed their first son, named Eugene to honor the little boy’s grandmother. Work offered a way for a reeling Isaac to process.

There was his earth-shaking run at Hamlet, in which Isaac starred as the titular prince in mourning at New York’s Public Theater. And then there was writer-director Dan Fogelman’s Life Itself, a film met with reviews that near-unanimously recoiled from its “cheesy,” “overwrought” structure, filled with what one critic called the genuine emotion of “a damage-control ExxonMobil commercial.”

The reaction surprised Isaac. “I thought it was some of my strongest work,” he says. “Especially at that moment in my life. This guy is dealing with grief and, for me, it was a really honest way of trying to understand those emotions and to create a character who was also going through just incomprehensible grief.” He’s proud of the performance—and, in a strange way, heartened by the sour critical response.

“To be honest,” he says brightly, “there was something really comforting about it.” That the work “for me, meant something and for others, didn’t at all, it just made the whole thing not matter so much in a great way.”

“I was able to explore something and come out the other end and feel like I grew as an actor,” he explains. “That matters to me a lot. And the response to that, you know, it’s interesting of course, but it was a great example for me of how it really doesn’t dictate how I then feel about what I did.”

He thinks for a moment of performances and projects that, conversely, embarrassed him—ones that to his shock, boasted “really great notices” in the end. “You just never know, you know? It’s completely out of my control.”

Isaac is an encouraging listener in conversation, doling out interested yeahs and uh-huhs, and often warm, self-deprecating laughter. When I broach a particularly personal subject, he seems to sit up—somehow, suddenly more present. It’s about his last name.

Óscar Isaac Hernández Estrada dropped both surnames before enrolling at Juilliard in 2001. He’d run into several Óscar Hernándezes at auditions by that point, and taken note of the stereotypes casting directors seemed to have in mind for them—gangsters, drug dealers, the works. So he made a change, not unlike many actors do.

Whether Óscar Hernández might have had a crack at the astonishingly diverse roles Oscar Isaac has inhabited, we’ll never know. But given Hollywood’s limiting tendencies, it’s less likely he might have played an English king for Ridley Scott in 2010’s Robin Hood, three years before his breakthrough role as a cantankerous folk singer in Joel and Ethan Coen’s Inside Llewyn Davis. He was an Armenian genocide survivor in last year’s The Promise, an Israeli secret agent in August’s Operation Finale, and now, he’s the Frenchman Paul Gauguin.

Star Wars’ Poe Dameron, meanwhile, or the mysterious tech billionaire in Alex Garland’s Ex Machina, or the army commando in his second Garland mind-twist, Annihilation, specify no ethnicities at all. It’s the dream: to be hailed as a great actor, period, and not a “great Latino actor” first. To be appreciated for your talent, and seen as “other” rarely at all.

There’s a crawl space between those distinctions, though, where another anxiety lives. The one that makes you wonder: Am I “representing” as loudly as I should? Am I obligated to do so in my work? If I don’t, what does that make me? Questions for when you grew up in Miami, or another Latino-dominant place, reckoning with how you’re perceived in a spotlight outside of it. Isaac listens attentively. Then for several unbroken minutes, talks it out with himself.

He rewinds to yesterday, when he boarded a plane from London on which an air steward addressed him repeatedly as “señor,” unbidden. “It was just a little weird. So I started calling him ‘señor’ as well. I was like, thank you, señor!” Isaac recalls, cracking up. “But then at the same time, I had that thought. I was like, but no, I should really, you know, be proud of being a señor, I guess?”

“I think for a lot of immigrants, the idea is that you don’t always just want to be thought of as other. Like, I don’t want him to be just calling me ‘señor.’ Why?” he asks, more of the steward than himself. “Because I look like I do, so I’m not a mystery anymore? It did bring up all those kinds of questions.”

He grew up in the United States, he explains; his family came over from Guatemala City when Isaac was 5 months old. “I’m most definitely Latino. That’s who I am. But at the same time, for an actor it’s like, I want to be hired not because of what I can represent, but because of what I can create, how I can transform, and the power of what I create.”

Still, Isaac has eyes and ears and exists in the year 2018 with the rest of us. “I’m not an idiot,” he adds. “And I know that we live in a politically charged time. There’s so much terrible language, particularly right now, being used against Latinos as a kind of political weapon.” He recognizes, too, the necessity “for people to see people that look like them, because that’s a very inspiring thing.”

As a kid, Isaac looked up to Raúl Juliá, the Puerto Rican-born actor and Broadway star whose breakthrough movie role came as Gomez Addams of the ’90s Addams Family films. “But I looked up to him particularly because he was a Latino that wasn’t being pigeonholed just in Latino parts,” Isaac adds.

“I do think there is a separation between the artist and the art form, between a craftsperson and the craft,” he says, applying the difference in this context to himself. He calls it “that double thing,” as apt a term as any for that peculiar, precise tension: “Like yes, I am who I am, I came from where I come from. But my interest isn’t just in showing people stuff about myself, because I don’t find me to be all that interesting.”

“What is more interesting to me is the work that I’m able to do, and all that time that I spent learning how to do Shakespeare and how to break down plays and try to create a character and do accents,” he says. “That, for me, is what’s fun.”

But it’s always that “double thing”—reconciling two pulls and finding a way not to get torn up. He wants American Latinos “to know, to be proud that there is someone from there that is out and doing work and being recognized not just for being a Latino that’s been able to do that.” On the other hand, he’s “just like any artist who’s out there doing something. I feel like that’s…” He pauses. “That’s also something to be proud of, you know?”

Isaac’s focus lands on me again. “And I think for you too, you’re a writer and that’s what you do. Your identity is also part of that, but I think that you want the work to stand on its own, too.” His sister is “an incredible scientist. She’s at the forefront of climate change and particularly how it affects Latino communities and low-income areas. And she is a Latina scientist, but she’s a scientist, you know? She’s a great scientist without the qualifier of where she’s from. And that’s also very important.”

Paul Gauguin’s life after van Gogh’s death by gunshot at 37 revealed more repugnant depths than his dick-ish insensitivity.

He defected from Paris again, this time to the South Pacific, determined to break from the staid art scene once and for all. He “married” three adolescent brides, two of them 14 years old and the other 13, infecting each girl with syphilis and settling into a private compound he dubbed Maison de Jouir, or “House of Orgasms.” “Pretty gnarly, nasty stuff,” Isaac concedes, though he withholds judgment of the man in his performance onscreen.

To do so might have made his Gauguin—alluring, haughty, insufferable, brilliant—“not quite as complex.” Opposite Willem Dafoe’s divinely wounded depiction of van Gogh, however, he found room to play. “It was interesting to ask, well, what’s the kind of person that would feel that he’s entitled to do those kinds of things?” The man onscreen is an asshole, to be sure, but hardly paints the word “sociopath” onto a canvas. He’s simply human: “I think that anyone has at least the capacity to do” what Gauguin did, Isaac reasons.

The actor has had more than one reason to think on a person’s capacity to do terrible things in the last year. Two men he’s worked with—his Show Me a Hero director, Paul Haggis, and X-Men: Apocalypse helmer Bryan Singer—were both accused of sexual assault in the last year, part of a torrent of unmasked misconduct Hollywood’s Me Too movement brought to national attention.

“It’s a tricky thing,” Isaac says, “because you get offered jobs all the time and, I guess, what’s required now? What kind of background checks can someone do beforehand? There isn’t a ton.” (Just ask Olivia Munn.) “Especially as an actor, to make sure that the people you’re working with, surrounding yourself with, haven’t done something in their past that I guess will make you seem somehow like you’re propping up bad behavior.”

Carefully, he expresses reservations about the phenomenon of the last year. “People don’t feel like they’re getting justice through any kind of legal system, so they take it to the streets,” he ventures. “It’s basically street justice. You have no other option. And what happens when you take it to the streets is that damage occurs, and sometimes people get taken down, things get destroyed that you feel like maybe shouldn’t have.”

“But some of it had to happen, and hopefully now there’ll be more of a system in place to take these things seriously,” he says. “It seems like it is starting to happen more, but then you see things like, how can this person get away with it? How can that person? It just boggles the mind.”

He pulls back again, remembering what’s out of his control.

Tomorrow, he’ll be back in an X-Wing suit, as Poe struggles to accept the same truth. In a year, he’ll be home in New York with his wife and young son, focusing on matters more “real” than Hollywood, its artists, and its art. Whatever he chooses whenever he returns, he’ll be ready—for the critics, the questions, for this new reality.

“All I can do is just do what means something to me,” he says. “You just have to find something honest.” One expects he will.

###

#oscar isaac#paul gauguin#at eternity's gate#poe dameron#star wars#carrie fisher#episode ix#episode 9#operation finale#life itself#inside llewyn davis#hamlet#robin hood#the promise#ex machina#annihilation#show me a hero#x men: apocalypse#interview

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Endless Story Of Being A Balkan Immigrant

Bulgarians: Have dishes similar to Southeast Asians, have words in common with Middle Eastern languages, share genes with Persian and Turkic peoples, genetically related to Mediterraneans and Middle Easterners, suspected common ancestor with Tatar peoples.

Also Bulgarians: Wow, we hate foreigners. We are so European. Middle Eastern people are evil. We are not all Roma. Go the EU! Voulez-vous coucher avec moi ce soir ?

Me, a Bulgarian and an intellectual: *major facepalm*

So, I almost got attacked recently.

A late evening, at one of the last trains from the capital to the place I live:

It’s a fairly popular stop, so there are some people at the doors as we wait for the train to come to a holt. I am at one side with a pair of men and one woman; the other door across the busy car has a small crowd in front of it too.

I am listening to music with one ear, the other free just in case somebody needs to approach me. A girl comes down the stairs to join our bunch and she is on the phone. The language sounds like Turkish to me, although I cannot be certain.

One of the men – a Finn no doubt, by his features – looks at the girl with obvious condescension, puffs dismissively, and walks across to the other door.

I stare, the complete awe on my face making the other Finnish man as uncomfortable as he should be.

“Asshole,” I murmur after the Original Finn.

He hears me.

Unconcerned with that, I step off the train and head home. He’s ahead if me; when he notices me – unmistakable in my bright red Uni hoodie – he stops in his tracks and waits me out.

I’m thinking, he’s about to say something. Is he planning on giving me a speech about foreigners in Finland, or the necessity of Finnish language when you are around a sensitive Finnish ear.

I don’t know.

But he says nothing as I pass him by. I walk away, casting glances over my shoulder. It’s how I notice him resuming his stride, following me, adjusting his scarf to cover his face as he hurries not to lose me.

There and then, I was terrified. Three full seconds of knowing I was about to experience a hate-crime motivated ass-whooping, and then I was done cowering. Not for him – he was hardly worth it.

Instead, I get prepared.

I walk faster, knowing I will reach a populated area soon, all the while planning where to put my glasses so he wouldn’t be able to break them into my eyes. I flex my fingers and wait for…

But I make it to the busy area before he makes it to me. The people outside the fast food joint chat with me until he’s passed. He gives me an unmistakable silent threat as he walks by me, and I wonder whether I could safely walk the 15 minutes it takes me to reach home. My teeth hurt from clenching but I am sure I would have taken that beating, because I was not wrong.

Because he thought it was his right to be surrounded – without failure, hour after hour – by exclusively Finnish speakers. Anything less offended his sensibilities. Because a special, nationalist, bigoted snowflake couldn’t take to be called out on his xenophobia.

I was right. Even if I almost got my nose punched in.

Or perhaps, that was a symptom of my rightness.

The current number of times a native speaker has looked at me with condescension and said, “Well, you speak quite good English,” is in the double digits.

*waves Certificate in Advanced English, a Specialised Language School diploma, and my middle finger*

I was so god damn pregnant and I didn’t care about it when it came to dates. My husband and I would go to concerts, festivals, and parties, regardless of how big I got. In restaurants, we’d order something fancy to eat, he’d order a wine to match, and I’ll sniff it before sipping my juice. Fun times.

So, there we were, at an Australian pub – him hoping to have an exciting Aussie brew and myself hoping to sniff it like a junkie with a glue problem.

But before we could get to that particularly exciting experience, we must order. The bartender practically gives my husband his own place at the bar. They like each other instantly and I am so proud of my charming, lovely sweetheart, who is not at all a Finnish stereotype and cannot wait to meet new people, engage with them, make them laugh. I adore it.

My husband decides on a beer and it’s my turn.

The bartender looks at me, his smile falters, and then dies. The temperature in the bar drops several degrees.

At this point, I am unsure what has happened. I wasn’t at the time aware Australians had any particular attitude towards Balkan people.

So, there I was, trying to order a juice for my pregnant ass and the bartender wouldn’t look me in the eye. He wouldn’t tell me what juices they have. He’d just spent five minutes combing through cupboards and fridges to make sure he’d offered the most suitable brew for my husband, but he wouldn’t bother to peek at the juice section for me.

My sweetheart ends up ordering for me. I know something had happened – something which involves bigotry and ugly thoughts – but I am unsure exactly what.

Today, I know. Today, if you ignore me, I just know to be louder.

There were fliers coming regularly to the box at my address, with calls to ‘DRIVE THE FOREIGNERS OUT OF BRITAIN AND TAKE BACK OUR COUNTRY’ written in big bright letters.

One weekend, I couldn’t go out because a nationalist group was organising a protest against Slavic and Middle Eastern immigrants at the city centre. I couldn’t do my shopping for the week. I was reduced to hiding in my room, alongside numerous friends and neighbours just like me.

“Oh, you are BUL-geeeeh-rian. I see.”

What? What is it you see?

Here’s a story you wouldn’t expect happened.

My in-laws have always kept close ties to old friends. They were the type of people whose jolly attitude had many from our small town running up to us at random places just to say hello. That very same friendly and open-hearted approach had me falling in love with my (then) boyfriend’s parents in no time.

So here we are, this one time, in the middle of their old friends’ and long-time colleagues’ house. It’s a lovely home and the fact the hosts had two children just a bit younger than myself was a great bonus.

We had a great conversation for the most part, even if I was excluded from the main topics due to a language barrier. I have since learned not to mind it so much, but at the time I relied heavily on my loved one translating.

Now, at the time, I was a student in the UK; there were no certain plans about where we’d be settling, if we’d be settling anywhere together at all. So, my grasp on the Finnish language remained basic, and I had no reason or desire to change that.

My hostess, to my endless surprise, had other plans for me.

She of course insisted I attempt speaking Finnish (an impossible task since I knew none of the grammatic rules), and was too excited about telling us all how the exchange student they hosted had been quick to pick up the language. I was of course already weary, but new to this “being an immigrant” thing. Coming from a poor place had not done much for my self-esteem anyway, and I was among people who had – due to their country’s social system – never had to worry about choosing between food and new clothes to replace the broken ones.

So, I accepted the only thing interesting about me is my potential to speak a language I wasn’t interested in. I accepted it while she probed and questioned and kept insisting people who “let me try” the language. I accepted it until the last drop of my patience had been drained.

And then she pushed further.

Engaging the rest of the party in her game, our hostess endeavoured to turn me into an experiment. She demanded nobody translate her words to me; she was to address me without saying my name, so they’d find out whether I understood she was talking to me.

The thing with Finnish is, you’re bound the understand more than you talk, at first. It’s a tough language but I had been exposed to it enough to know what she’d said. Or understand enough.

When she spoke and the entire table remained silent, engaged in her experiment—in her treatment of me as a science rat, a sub-human, a person not worthy of consideration but rather just there for her eternal amusement—I could not stop myself from tearing up.

I was utterly alone, surrounded by people who were unaware they were doing something wrong, and one person who was so deliberate in her actions, she surely understood way-too-well exactly what she was doing.

She invited us to her wedding years later and I spoke English to her with a polite smile.

The cold shivers down my spine when I found out the person who was going to wed us is running for a position in the government with the Finnish far-right party.

I gave birth in the middle of 2015. It was warm and nice and beautiful. The first hours of contractions were painful, annoying, and long, but I felt safe and happy with my husband next to me and an attentive midwife making sure everything was going smoothly.

The shift changed the moment labour began.

The midwife began the entire ordeal by proclaiming she had not come to work today with the intention to speak English. She admitted she understood it well, although she ignored every word I spoke in it.

She ignored me when I said I could not breathe.

Again.

And again.

And again.

I lost consciousness for a few seconds due to lack of oxygen. Sheer willpower kept me afloat through the last moments of labour. I had to somehow gather strength to yell “I CANNOT BREATHE” for her to offer me an oxygen mask. She also called another midwife though, to help her handle the rowdy foreigner.

Suffice to say, I did not trust her with my new-born, breakable daughter. Suffice to say, I had no choice in the matter.

I only prayed – atheist as I am – that she would not be that great of a monster.

“What is this Bulgarian gibberish? I speak three languages but in this country, I speak its language, as one should”

– A person sitting at my table, in my home, listening to me speaking my language to my daughter.

Nobody knows anything about Bulgaria, much beyond the fact they must hate us for being poor. Of those who do not hate us, they still are unaware of who we are.

Our country was established in 681 according to official accounts, although a Great Bulgaria existed already during 635. Our country was formed through the alliance of (what is estimated to have been) over a thousand Bulgar nomads and the resident Balkan Slavic tribes. Over the course of the following centuries, Bulgarians spread out to include other Slavic, including some Mid-European. Our lands – although in a constant state of change due to never-ending wars with Byzantine – reached on occasions three seas: Adriatic, Aegean, and Black.

We spent altogether six centuries as an independent empire. Our first universal law extended beyond the limits of status or nobility, threatening all criminals (even those living in our castles) with serious punishment. We were by recent accounts among the first countries in Europe (long before the middle Ages) to bring canalisation and fresh water supply systems to our big cities; the architectural collaboration with Middle Eastern societies is an interesting archaeological discovery: a lot of knowledge was lost to us during the destruction brought upon us by the Ottoman empire. We were also the ones to spread the Cyrillic alphabet among Slavic-speaking peoples, and the first to use it in our churches in the form of Old Slavonic.

We spent five centuries under Ottoman Yoke.

I will be the first one to tell you we must never bring the pain of our past into our present, let alone our future. I will be the first one to tell you we must not blame Turkish people for the crimes of their ancestors. Unless we are met with that maddening, infamous reminder that we have been their “cattle”, it wins us nothing to point our fingers at them. Especially at those who say proudly they are Bulgarians by birth but do not deny their ethnic Turkish roots.

But we must never forget – for our sakes and not for the sake of hatred – that we were denied the right to move freely, denied the right to live under the protection of a law, denied practicing a religion which defined us, denied spreading language or education which humanised us, denied access to a script we’ve developed and popularized. We were denied the right to be people; denied the right to be free.

We were owned, and shipped, and stripped, and slaughtered, and bullied, and managed exactly like—cattle. Our women were taken for unwilling concubines. Our churches and towns and schools and educational centres were burned. Our boys were taken to be owned by the army. Our blood ran as rivers along the lands of our ancestors and although the people who have committed those heinous crimes are long-dead… the pain remains.

We must never forget that if we kicked the Ottoman Master’s dog even though it was nibbling on our leg, we were shot and killed. We must not forget that if we didn’t let the Ottoman militia rape as they pleased, an entire household was slaughtered.

We must not forget we lived in peace with common Muslim folk. But we must not forget that we were indeed once cattle.

And even though our suffering was quantifiably different to the pain endured by the Black British and American communities, we must not forget we were slaves too.

It’s because we must never allow ourselves to be slaves again.

We have a story, Bulgarians.

That when the Ottomans first came, they pillaged and raped and destroyed, but if they’d left any survivors, they’d ask them always a simple question: “Do you convert to the Muslim faith?”

We have no certain way of knowing whether this is a story of pride, an anecdote to signify the overall resistance of the people, or an actual account of the events during the conquering of our lands.

But according to what we’ve been told, a Bulgarian who accepted the Muslim faith would shake their head and stand as they are.

A Bulgarian who would deny the offer, would bow their head – in preparation for their execution.

It is, according to this anecdote, the reason why in our culture, we bow our heads for “no” and shake them for “yes” – in contrast with the rest of Europe and the Western world.

Above is one of the reasons I never bow my head or accept a faith offered to me by a bigot.

It’s in my blood to stand my ground, even if it means my downfall. It’s in my blood to be considered cattle but to persevere regardless. It’s in my blood to be ignored, shunned, forgotten, stepped on… and to still bloom beneath the piles of dirt and cheap concrete blocks.

It’s in my blood to be regarded as sub-human; and it is in my blood to shed every tear, every drop of blood, to be better than that. To survive despite it.

It’s why I was ready for a fight the night I was almost beaten up. It’s why I still speak the language I want whenever I want. It’s why I still call people out on their bigotry.

And it’s why I am a proud Balkan immigrant.

Because I’m stronger than they are.

Stay strong, stay true, stay readin’,

Ro-ri

#immigrant#balkan#wog#bigotry#xenophobia#my essay#essays and writings#hatred#hate crimes#ethnic hate#bulgarian#bulgarian history#ottoman empire#ottoman rule#under yoke#violence#violence tw#bigotry tw#aggression#immigration#uk#finland#brexit#finnish nationalist#british nationalism#slavic#slavic hate#slavic nation#slavic people#i couldn't fucking breathe

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hitchcock and Truffaut in Conversation on the Art and Craft of Storytelling

In June 1962, French screenwriter, director, producer and actor François Truffaut wrote a letter to Alfred Hitchcock asking whether he might interview him in depth about his life and career. Truffaut proposed they meet to talk for a week of all day interviews. In the letter he stated his reasons:

Paris, 2 June 1962 Dear Mr Hitchcock, First of all, allow me to remind you who I am. A few years ago, in late 1954, when I was a film journalist, I came with my friend Claude Chabrol to interview you at the Saint-Maurice studio where you were directing the post-synchronization of To Catch a Thief. You asked us to go and wait for you in the studio bar, and it was then that, in the excitement of having watched fifteen times in succession a ‘loop’ showing Brigitte Auber and Cary Grant in a speedboat, Chabrol and I fell into the frozen tank in the studio courtyard. You very kindly agreed to postpone the interview which was conducted that same evening at your hotel. Subsequently, each time you visited Paris, I had the pleasure of meeting you with Odette Ferry, and for the following year you even said to me, ‘Whenever I see ice cubes in a glass of whisky I think of you.’ One year after that, you invited me to come to New York for a few days and watch the shooting of The Wrong Man, but I had to decline the invitation since, a few months after Claude Chabrol, I turned to film-making myself. I have made three films, the first of which, The Four Hundred Blows, had, I believe, a certain success in Hollywood. The latest, Jules et Jim, is currently showing in New York. I come now to the point of my letter. In the course of my discussions with foreign journalists and especially in New York, I have come to realize that their conception of your work is often very superficial. Moreover, the kind of propaganda that we were responsible for in Cahiers du cinéma was excellent as far as France was concerned, but inappropriate for America because it was too intellectual. Since I have become a director myself, my admiration for you has in no way weakened; on the contrary, it has grown stronger and changed in nature. There are many directors with a love for the cinema, but what you possess is a love of celluloid itself and it is that which I would like to talk to you about. I would like you to grant me a tape-recorded interview which would take about eight days to conduct and would add up to about thirty hours of recordings. The point of this would be to distil not a series of articles but an entire book which would be published simultaneously in New York (I would consider offering it, for example, to Simon and Schuster where I have some friends) and Paris (by Gallimard or Robert Laffont), then, probably later, more or less everywhere in the world. If the idea were to appeal to you, and you agreed to do it, here is how I think we might proceed: I could come and stay for about ten days wherever it would be most convenient for you. From New York I would bring with me Miss Helen Scott who would be the ideal interpreter; she carries out simultaneous translations at such speed that we would have the impression of speaking to one another without any intermediary and, working as she does at the French Film Office in New York, she is also completely familiar with the vocabulary of the cinema. She and I would take rooms in the hotel closest to your home or to whichever office you might arrange. Here is the work schedule. Just a very detailed interview in chronological order. To start with, some biographical notes, then the first jobs you had before entering the film industry, then your stay in Berlin. This would be followed by: 1. the British silent films; 2. the British sound films; 3. the first American films for Selznick and the spy films; 4. the two ‘Transatlantic Pictures’ 5. the Vistavision period; 6. from The Wrong Man to the The Birds.

The questions would focus more precisely on:

a) the circumstances surrounding the inception of each film; b) the development and construction of the screenplay; c) the stylistic problems peculiar to each film; d) the situation of the film in relation to those preceding it; e) your own assessment of the artistic and commercial result in relation to your intentions. There would be questions of a more general nature on: good and bad scripts, different styles of dialogue, the direction of actors, the art of editing, the development of new techniques, special effects and colour. These would be interspaced among the different categories in order to prevent any interruption in chronology. The body of work would be preceded by a text which I would write myself and which might be summarized as follows: if, overnight, the cinema had to do without its soundtrack and became once again a silent art, then many directors would be forced into unemployment, but, among the survivors, there would be Alfred Hitchcock and everyone would realize at last that he is the greatest film director in the world. If this project interests you, I would ask you to let me know how you would like to proceed. I imagine that you are in the process of editing The Birds, and perhaps you would prefer to wait a while? For my part, at the end of this year I am due to make my next films, an adaptation of a novel by Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451, which is why I would prefer the interviews to take place between 15 July and 15 September 1962. If you were to accept the proposition, I would gather together all the documents I would need to prepare the four or five hundred questions which I wish to ask you, and I would have the Brussels Cinémathèque screen for me those films of yours with which I am least familiar. That would take me about three weeks, which would mean I could be at your disposal from the beginning of July. A few weeks after our interviews, the transcribed, edited and corrected text would be submitted to you in English so that you might make any corrections that you considered useful, and the book itself would be ready to come out by the end of this year. Awaiting your reply, I beg you to accept, dear Mr Hitchcock, my profound admiration. I remain Yours sincerely, Francois Truffaut

Hitchcock's response was by telegram shortly after receiving the letter:

Dear Monsieur Truffaut – Your letter brought tears to my eyes and I am so grateful to receive such a tribute from you – Stop – I am shooting The Birds and this will continue until 15 July and after that I will have to begin editing which will take me several weeks – Stop – I think I will wait until we have finished shooting The Birds and then I will contact you with the idea of getting together around the end of August – Stop – Thank you again for your charming letter – Kind regards – Cordially yours – Alfred Hitchcock.

Because he spoke little English, Truffaut hired Helen Scott of the French Film Office in New York to translate. The conversations filled 50 hours of tape about 54 films. A partial set of audio files are here. At the time, Hitchcock wasn't as popular and yet he had already innovated the art of storytelling in movies.

The tapes are a record of the British director's opinions, ideas, and thoughts on both the stories he told through film and how he did it, including mistakes he felt he made and how he would 'fix' them, if he could. The interviews were published in a book in 1967. A revised edition of Hitchcock included the director's later career.

In the introduction, Truffaut says:

Nowadays, the work of Alfred Hitchcock is admired all over the world. Young people who are just discovering his art through the current rerelease of Rear Window and Vertigo, or through North by Northwest, may assume his prestige has always been recognized, but this is far from being the case. In the fifties and sixties, Hitchcock was at the height of his creativity and popularity. He was, of course, famous due to the publicity masterminded by producer David O. Selznick during the six or seven years of their collaboration on such films as Rebecca, Notorious, Spellbound, and The Paradine Case. His fame had spread further throughout the world via the television series Alfred Hitchcock Presents in the mid-fifties. But American and European critics made him pay for his commercial success by reviewing his work with condescension, and by belittling each new film.

[...]

In examining his films, it was obvious that he had given more thought to the potential of his art than any of his colleagues. It occurred to me that if he would, for the first time, agree to respond seriously to a systematic questionnaire, the resulting document might modify the American critics’ approach to Hitchcock. That is what this book is all about.

During a Hollywood press conference in 1947, Alfred Hitchcock talked about his art, which was about involving the audience and creating suspense. He said:

I aim to provide the public with beneficial shocks. Civilization has become so protective that we’re no longer able to get our goose bumps instinctively. The only way to remove the numbness and revive our moral equilibrium is to use artificial means to bring about the shock. The best way to achieve that, it seems to me, is through a movie.

Suspense is the essence of cinema and Hitchcock was a master of special effects before they were a thing, using images rather than dialogue to further a story. About dialogue he says:

In many of the films now being made, there is very little cinema: they are mostly what I call 'photographs of people talking.' When we tell a story in cinema we should resort to dialogue only when it's impossible to do otherwise. I always try to tell a story in the cinematic way, through a succession of shots and bits of film in between.

[...]

Dialogue should simply be a sound among other sounds, just something that comes out of the mouths of people whose eyes tell the story in visual terms.

He also understood that people don't want to be educated, nor do they want to be tricked — as he discovered in Sabotage, a flop.

Hitchcock was very creative; we can draw lessons for marketers from his recurring themes. Anyone interested in the art of storytelling should pick up a copy of Hitchcock, a wonderful collection of insights Truffaut elicited by being in conversation with a master of the art.

from DIYS http://ift.tt/2mBOP0p

0 notes

Text

Hitchcock and Truffaut in Conversation on the Art and Craft of Storytelling

In June 1962, French screenwriter, director, producer and actor François Truffaut wrote a letter to Alfred Hitchcock asking whether he might interview him in depth about his life and career. Truffaut proposed they meet to talk for a week of all day interviews. In the letter he stated his reasons:

Paris, 2 June 1962 Dear Mr Hitchcock, First of all, allow me to remind you who I am. A few years ago, in late 1954, when I was a film journalist, I came with my friend Claude Chabrol to interview you at the Saint-Maurice studio where you were directing the post-synchronization of To Catch a Thief. You asked us to go and wait for you in the studio bar, and it was then that, in the excitement of having watched fifteen times in succession a ‘loop’ showing Brigitte Auber and Cary Grant in a speedboat, Chabrol and I fell into the frozen tank in the studio courtyard. You very kindly agreed to postpone the interview which was conducted that same evening at your hotel. Subsequently, each time you visited Paris, I had the pleasure of meeting you with Odette Ferry, and for the following year you even said to me, ‘Whenever I see ice cubes in a glass of whisky I think of you.’ One year after that, you invited me to come to New York for a few days and watch the shooting of The Wrong Man, but I had to decline the invitation since, a few months after Claude Chabrol, I turned to film-making myself. I have made three films, the first of which, The Four Hundred Blows, had, I believe, a certain success in Hollywood. The latest, Jules et Jim, is currently showing in New York. I come now to the point of my letter. In the course of my discussions with foreign journalists and especially in New York, I have come to realize that their conception of your work is often very superficial. Moreover, the kind of propaganda that we were responsible for in Cahiers du cinéma was excellent as far as France was concerned, but inappropriate for America because it was too intellectual. Since I have become a director myself, my admiration for you has in no way weakened; on the contrary, it has grown stronger and changed in nature. There are many directors with a love for the cinema, but what you possess is a love of celluloid itself and it is that which I would like to talk to you about. I would like you to grant me a tape-recorded interview which would take about eight days to conduct and would add up to about thirty hours of recordings. The point of this would be to distil not a series of articles but an entire book which would be published simultaneously in New York (I would consider offering it, for example, to Simon and Schuster where I have some friends) and Paris (by Gallimard or Robert Laffont), then, probably later, more or less everywhere in the world. If the idea were to appeal to you, and you agreed to do it, here is how I think we might proceed: I could come and stay for about ten days wherever it would be most convenient for you. From New York I would bring with me Miss Helen Scott who would be the ideal interpreter; she carries out simultaneous translations at such speed that we would have the impression of speaking to one another without any intermediary and, working as she does at the French Film Office in New York, she is also completely familiar with the vocabulary of the cinema. She and I would take rooms in the hotel closest to your home or to whichever office you might arrange. Here is the work schedule. Just a very detailed interview in chronological order. To start with, some biographical notes, then the first jobs you had before entering the film industry, then your stay in Berlin. This would be followed by: 1. the British silent films; 2. the British sound films; 3. the first American films for Selznick and the spy films; 4. the two ‘Transatlantic Pictures’ 5. the Vistavision period; 6. from The Wrong Man to the The Birds.

The questions would focus more precisely on:

a) the circumstances surrounding the inception of each film; b) the development and construction of the screenplay; c) the stylistic problems peculiar to each film; d) the situation of the film in relation to those preceding it; e) your own assessment of the artistic and commercial result in relation to your intentions. There would be questions of a more general nature on: good and bad scripts, different styles of dialogue, the direction of actors, the art of editing, the development of new techniques, special effects and colour. These would be interspaced among the different categories in order to prevent any interruption in chronology. The body of work would be preceded by a text which I would write myself and which might be summarized as follows: if, overnight, the cinema had to do without its soundtrack and became once again a silent art, then many directors would be forced into unemployment, but, among the survivors, there would be Alfred Hitchcock and everyone would realize at last that he is the greatest film director in the world. If this project interests you, I would ask you to let me know how you would like to proceed. I imagine that you are in the process of editing The Birds, and perhaps you would prefer to wait a while? For my part, at the end of this year I am due to make my next films, an adaptation of a novel by Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451, which is why I would prefer the interviews to take place between 15 July and 15 September 1962. If you were to accept the proposition, I would gather together all the documents I would need to prepare the four or five hundred questions which I wish to ask you, and I would have the Brussels Cinémathèque screen for me those films of yours with which I am least familiar. That would take me about three weeks, which would mean I could be at your disposal from the beginning of July. A few weeks after our interviews, the transcribed, edited and corrected text would be submitted to you in English so that you might make any corrections that you considered useful, and the book itself would be ready to come out by the end of this year. Awaiting your reply, I beg you to accept, dear Mr Hitchcock, my profound admiration. I remain Yours sincerely, Francois Truffaut

Hitchcock's response was by telegram shortly after receiving the letter:

Dear Monsieur Truffaut – Your letter brought tears to my eyes and I am so grateful to receive such a tribute from you – Stop – I am shooting The Birds and this will continue until 15 July and after that I will have to begin editing which will take me several weeks – Stop – I think I will wait until we have finished shooting The Birds and then I will contact you with the idea of getting together around the end of August – Stop – Thank you again for your charming letter – Kind regards – Cordially yours – Alfred Hitchcock.

Because he spoke little English, Truffaut hired Helen Scott of the French Film Office in New York to translate. The conversations filled 50 hours of tape about 54 films. A partial set of audio files are here. At the time, Hitchcock wasn't as popular and yet he had already innovated the art of storytelling in movies.

The tapes are a record of the British director's opinions, ideas, and thoughts on both the stories he told through film and how he did it, including mistakes he felt he made and how he would 'fix' them, if he could. The interviews were published in a book in 1967. A revised edition of Hitchcock included the director's later career.

In the introduction, Truffaut says:

Nowadays, the work of Alfred Hitchcock is admired all over the world. Young people who are just discovering his art through the current rerelease of Rear Window and Vertigo, or through North by Northwest, may assume his prestige has always been recognized, but this is far from being the case. In the fifties and sixties, Hitchcock was at the height of his creativity and popularity. He was, of course, famous due to the publicity masterminded by producer David O. Selznick during the six or seven years of their collaboration on such films as Rebecca, Notorious, Spellbound, and The Paradine Case. His fame had spread further throughout the world via the television series Alfred Hitchcock Presents in the mid-fifties. But American and European critics made him pay for his commercial success by reviewing his work with condescension, and by belittling each new film.

[...]

In examining his films, it was obvious that he had given more thought to the potential of his art than any of his colleagues. It occurred to me that if he would, for the first time, agree to respond seriously to a systematic questionnaire, the resulting document might modify the American critics’ approach to Hitchcock. That is what this book is all about.

During a Hollywood press conference in 1947, Alfred Hitchcock talked about his art, which was about involving the audience and creating suspense. He said:

I aim to provide the public with beneficial shocks. Civilization has become so protective that we’re no longer able to get our goose bumps instinctively. The only way to remove the numbness and revive our moral equilibrium is to use artificial means to bring about the shock. The best way to achieve that, it seems to me, is through a movie.

Suspense is the essence of cinema and Hitchcock was a master of special effects before they were a thing, using images rather than dialogue to further a story. About dialogue he says:

In many of the films now being made, there is very little cinema: they are mostly what I call 'photographs of people talking.' When we tell a story in cinema we should resort to dialogue only when it's impossible to do otherwise. I always try to tell a story in the cinematic way, through a succession of shots and bits of film in between.

[...]

Dialogue should simply be a sound among other sounds, just something that comes out of the mouths of people whose eyes tell the story in visual terms.

He also understood that people don't want to be educated, nor do they want to be tricked — as he discovered in Sabotage, a flop.

Hitchcock was very creative; we can draw lessons for marketers from his recurring themes. Anyone interested in the art of storytelling should pick up a copy of Hitchcock, a wonderful collection of insights Truffaut elicited by being in conversation with a master of the art.

from DIYS http://ift.tt/2mBOP0p

0 notes

Text

Hitchcock and Truffaut in Conversation on the Art and Craft of Storytelling

In June 1962, French screenwriter, director, producer and actor François Truffaut wrote a letter to Alfred Hitchcock asking whether he might interview him in depth about his life and career. Truffaut proposed they meet to talk for a week of all day interviews. In the letter he stated his reasons:

Paris, 2 June 1962 Dear Mr Hitchcock, First of all, allow me to remind you who I am. A few years ago, in late 1954, when I was a film journalist, I came with my friend Claude Chabrol to interview you at the Saint-Maurice studio where you were directing the post-synchronization of To Catch a Thief. You asked us to go and wait for you in the studio bar, and it was then that, in the excitement of having watched fifteen times in succession a ‘loop’ showing Brigitte Auber and Cary Grant in a speedboat, Chabrol and I fell into the frozen tank in the studio courtyard. You very kindly agreed to postpone the interview which was conducted that same evening at your hotel. Subsequently, each time you visited Paris, I had the pleasure of meeting you with Odette Ferry, and for the following year you even said to me, ‘Whenever I see ice cubes in a glass of whisky I think of you.’ One year after that, you invited me to come to New York for a few days and watch the shooting of The Wrong Man, but I had to decline the invitation since, a few months after Claude Chabrol, I turned to film-making myself. I have made three films, the first of which, The Four Hundred Blows, had, I believe, a certain success in Hollywood. The latest, Jules et Jim, is currently showing in New York. I come now to the point of my letter. In the course of my discussions with foreign journalists and especially in New York, I have come to realize that their conception of your work is often very superficial. Moreover, the kind of propaganda that we were responsible for in Cahiers du cinéma was excellent as far as France was concerned, but inappropriate for America because it was too intellectual. Since I have become a director myself, my admiration for you has in no way weakened; on the contrary, it has grown stronger and changed in nature. There are many directors with a love for the cinema, but what you possess is a love of celluloid itself and it is that which I would like to talk to you about. I would like you to grant me a tape-recorded interview which would take about eight days to conduct and would add up to about thirty hours of recordings. The point of this would be to distil not a series of articles but an entire book which would be published simultaneously in New York (I would consider offering it, for example, to Simon and Schuster where I have some friends) and Paris (by Gallimard or Robert Laffont), then, probably later, more or less everywhere in the world. If the idea were to appeal to you, and you agreed to do it, here is how I think we might proceed: I could come and stay for about ten days wherever it would be most convenient for you. From New York I would bring with me Miss Helen Scott who would be the ideal interpreter; she carries out simultaneous translations at such speed that we would have the impression of speaking to one another without any intermediary and, working as she does at the French Film Office in New York, she is also completely familiar with the vocabulary of the cinema. She and I would take rooms in the hotel closest to your home or to whichever office you might arrange. Here is the work schedule. Just a very detailed interview in chronological order. To start with, some biographical notes, then the first jobs you had before entering the film industry, then your stay in Berlin. This would be followed by: 1. the British silent films; 2. the British sound films; 3. the first American films for Selznick and the spy films; 4. the two ‘Transatlantic Pictures’ 5. the Vistavision period; 6. from The Wrong Man to the The Birds.

The questions would focus more precisely on:

a) the circumstances surrounding the inception of each film; b) the development and construction of the screenplay; c) the stylistic problems peculiar to each film; d) the situation of the film in relation to those preceding it; e) your own assessment of the artistic and commercial result in relation to your intentions. There would be questions of a more general nature on: good and bad scripts, different styles of dialogue, the direction of actors, the art of editing, the development of new techniques, special effects and colour. These would be interspaced among the different categories in order to prevent any interruption in chronology. The body of work would be preceded by a text which I would write myself and which might be summarized as follows: if, overnight, the cinema had to do without its soundtrack and became once again a silent art, then many directors would be forced into unemployment, but, among the survivors, there would be Alfred Hitchcock and everyone would realize at last that he is the greatest film director in the world. If this project interests you, I would ask you to let me know how you would like to proceed. I imagine that you are in the process of editing The Birds, and perhaps you would prefer to wait a while? For my part, at the end of this year I am due to make my next films, an adaptation of a novel by Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451, which is why I would prefer the interviews to take place between 15 July and 15 September 1962. If you were to accept the proposition, I would gather together all the documents I would need to prepare the four or five hundred questions which I wish to ask you, and I would have the Brussels Cinémathèque screen for me those films of yours with which I am least familiar. That would take me about three weeks, which would mean I could be at your disposal from the beginning of July. A few weeks after our interviews, the transcribed, edited and corrected text would be submitted to you in English so that you might make any corrections that you considered useful, and the book itself would be ready to come out by the end of this year. Awaiting your reply, I beg you to accept, dear Mr Hitchcock, my profound admiration. I remain Yours sincerely, Francois Truffaut

Hitchcock's response was by telegram shortly after receiving the letter:

Dear Monsieur Truffaut – Your letter brought tears to my eyes and I am so grateful to receive such a tribute from you – Stop – I am shooting The Birds and this will continue until 15 July and after that I will have to begin editing which will take me several weeks – Stop – I think I will wait until we have finished shooting The Birds and then I will contact you with the idea of getting together around the end of August – Stop – Thank you again for your charming letter – Kind regards – Cordially yours – Alfred Hitchcock.

Because he spoke little English, Truffaut hired Helen Scott of the French Film Office in New York to translate. The conversations filled 50 hours of tape about 54 films. A partial set of audio files are here. At the time, Hitchcock wasn't as popular and yet he had already innovated the art of storytelling in movies.

The tapes are a record of the British director's opinions, ideas, and thoughts on both the stories he told through film and how he did it, including mistakes he felt he made and how he would 'fix' them, if he could. The interviews were published in a book in 1967. A revised edition of Hitchcock included the director's later career.

In the introduction, Truffaut says:

Nowadays, the work of Alfred Hitchcock is admired all over the world. Young people who are just discovering his art through the current rerelease of Rear Window and Vertigo, or through North by Northwest, may assume his prestige has always been recognized, but this is far from being the case. In the fifties and sixties, Hitchcock was at the height of his creativity and popularity. He was, of course, famous due to the publicity masterminded by producer David O. Selznick during the six or seven years of their collaboration on such films as Rebecca, Notorious, Spellbound, and The Paradine Case. His fame had spread further throughout the world via the television series Alfred Hitchcock Presents in the mid-fifties. But American and European critics made him pay for his commercial success by reviewing his work with condescension, and by belittling each new film.

[...]

In examining his films, it was obvious that he had given more thought to the potential of his art than any of his colleagues. It occurred to me that if he would, for the first time, agree to respond seriously to a systematic questionnaire, the resulting document might modify the American critics’ approach to Hitchcock. That is what this book is all about.

During a Hollywood press conference in 1947, Alfred Hitchcock talked about his art, which was about involving the audience and creating suspense. He said:

I aim to provide the public with beneficial shocks. Civilization has become so protective that we’re no longer able to get our goose bumps instinctively. The only way to remove the numbness and revive our moral equilibrium is to use artificial means to bring about the shock. The best way to achieve that, it seems to me, is through a movie.

Suspense is the essence of cinema and Hitchcock was a master of special effects before they were a thing, using images rather than dialogue to further a story. About dialogue he says: