#of it being like!! a posthumous album in Canon

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

⠀⠀★ my love is a fire, i want to be your fire 불타올라 내게 불을 붙여주지 난 burn .

#* / 𝐓𝐈𝐓𝐋𝐄 𝐓𝐑𝐀𝐂𝐊 𝟎𝟎𝟏 : 𝖽𝖾𝖺𝗋 𝒍𝒆𝒂𝒅𝒆𝒓 — audio#* / 𝐓𝐈𝐓𝐋𝐄 𝐓𝐑𝐀𝐂𝐊 𝟎𝟎𝟏 : 𝖽𝖾𝖺𝗋 𝒍𝒆𝒂𝒅𝒆𝒓 — dossier#making this song a feature with jiwoon like hear me out hear me out. the entire symbolism of Fire in this song#and love being about BURNING. yeah. yeah#also i can't believe i am SOOO close to minjun solo album. ur about to be so sick of me and i'm already imagining and thinking#of it being like!! a posthumous album in Canon#and then ofc just a solo project if minjun had still been Alive

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Notre-Dame cathedral, maybe a too-popular choice but I can say that I was actually there back in like 1998. It did get a novel written about it because of reasons.

Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen, only because it was really my gateway to gothic literature, being itself an affectionate parody of early gothic literature. I already knew about the monster mash side of goth lit with Frankenstein and Dracula. I didn't really love this genre until Jane Austen posthumously stepped right into what was left of my homoerotic toxic friendship issues.

Fraternity by Andy Mientus. It's marketed as dark academia, but after researching what even qualifies gothic literature anyway—this book screams gothic horror. There's getting haunted by the past. There's asylum confinement. There's cavorting about in forests, and taking motorbike rides out in moonlight, and big-city-as-wilderness. There's demon-summoning. Zachary Orson is one of the most complicated Byronic heroes that I have ever read, I just love his character development and all his layers and facets. There's so much architecture that architecture becomes a murder weapon.

Honorable mentions: The Orphanage (2007 film) ...I like better as a genre piece than Crimson Peak, and Guillermo del Toro was involved in both; The Spirit Bares Its Teeth by Andrew Joseph White that is on my to-read list because from the blurb alone I already know that I am going to love this story; ...does Nightwish count? I heard maybe two songs by them, supremely sublime. Evanescence's "Fallen" album deserved its popularity, in my opinion, but I understand if it's too soft on the mall/scene Emo side of things to be considered Gothic.

I did make that "Blood Orange? She's so pretentious. Shut up, it's red!" meme riffing on Digital Gothic ("Shut up, it's cyberpunk!") But I do think "V*mpire" by P.H. Lee counts as digital gothic that is not cyberpunk. Abjection and Uncanny in large amounts.

The Phantom of the Opera stage musical by Andrew Lloyd Webber—I still think that Into the Woods should have won that Tony, but I will say that I prefer the Broadway musical to the novel that it was based on. The book was a campy fun read with a baddie who would be so extra and everybody else going Scooby-Doo about how the Phantom did the things, but the musical version gave it a flow and a tone and a sentimentality that I think made it more categorically Gothic (instead of only, like, sparkling cozy-mystery...that I think the book was.)

Mutuals who are hardcore fans of Like Minds and Saltburn can argue better than I can why those films are in their personal favorite gothic movie canon.

can anyone give me their top 3 recommended gothic arts..in the respect of literature, paintings, history, art history, films, anything that thoroughly draws you in - trying to make a big list :)))

16 notes

·

View notes

Audio

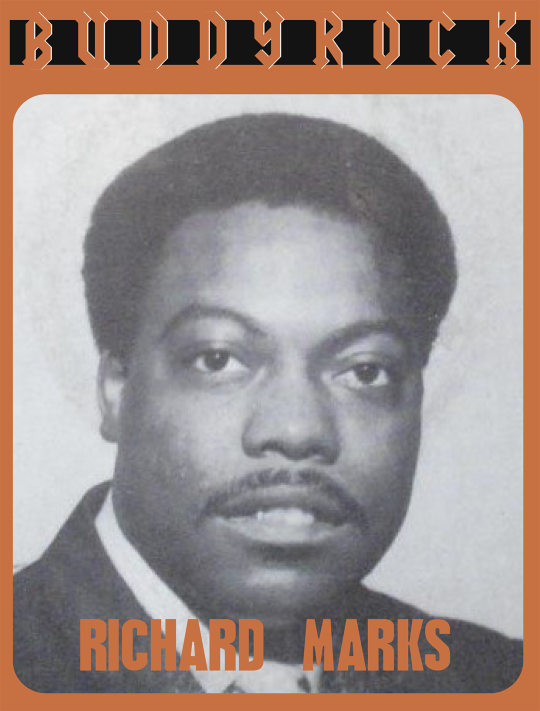

Richard Marks

Funk fans love several of guitarist/vocalist Richard Marks’ 45s and indeed he did make some high class dance music – but there was more to his career than that. It seems as though his first release was the initial 45 for the legendary Tuska label from his home town Atlanta, GA.

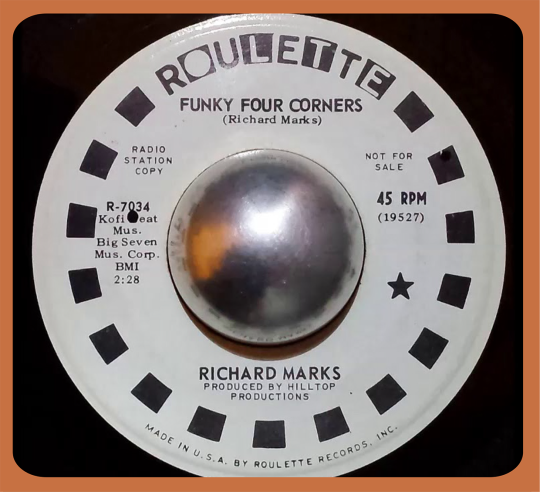

His own “Funky Four Corners” ran to two parts, with the second half being a fine advertisement for his guitar work. Although this got a national release on Roulette it never dented the charts. His second single “I’m The Man For You” is another spare funky workout, with more than a hint of the Soul Brother #1 in his axe style and horn arrangement.

Georgia music man Tee Fletcher had more than hand in Marks’ upbeat “Don’t Take It Out On Me” which was leased out to Shout. The flip “Love Is Gone” is in a similar vein, but the better melody and higher grade performance from Marks make this the preferred side. His third Tuska 45 was for me his best to date. ListenDid You Ever Lose Something was a fine piece of strutting southern soul with some fine horns, and the flip “Never Satisfied” was another JB styled funk winner. The odd ball release from his Did you ever lose something - TUSKA 112stay with Tuska was the Christmas 45. “Home For The Holidays” was a pleasant if unremarkable toe tapper, but the flip “Mr Santa Clause” was a revelation. A dead slow blues of considerable power it was the first time that Marks was able to show off his chops on a ballad.

During the 70s Marks worked with Bill Wright for some time and they shared labels like Tuska and Note together.

Now in 2019 you can touch funk oldschool legend Richard Marks by your own by clicking here

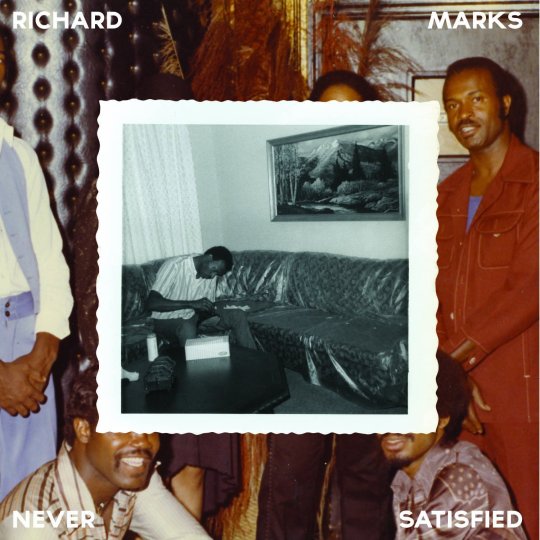

These songs, found on reels that Marks kept in his home, color Marks’ stylistic development – from his earliest work for the legendary Tuska label in the late ‘60s, through his more mature releases on smaller regional labels into the late ‘70s.

Marks’ story is that of an unsung soul and funk hero; he was a guitarist, vocalist and songwriter whose phone number was in Al Green’s, Barry White’s and Eddie Kendricks’ rolodexes, but his talents have only been heard in sporadic bursts. He and his music are unknown to the majority, but to an obsessive minority, he is a lightning rod: that singular point at which numerous Southern soul and funk musicians converged and exploded, spreading wondrous music in all directions.

Marks died of cancer in May 2006. His first album was our Never Satisfied anthology, released posthumously. He stands out as a most mysterious talent to originate from Atlanta, a city that birthed no shortage of genius, and Love Is Gone – The Lost Sessions 1969-1977 further makes the case for a reassessment of his talents and his place in the soul and funk canon.

Oldschool 45′s are here

#richard marks#rare_footage#rare#soul#funk#jazz#rock#grooves#outstanding#beats&breaks#get down#toprock#downrock#rockdance#jerks#burns

1 note

·

View note

Text

John Coltrane

John William Coltrane, also known as Trane (September 23, 1926 – July 17, 1967), was an American jazz saxophonist and composer. Working in the bebop and hard bop idioms early in his career, Coltrane helped pioneer the use of modes in jazz and was later at the forefront of free jazz. He led at least fifty recording sessions during his career, and appeared as a sideman on many albums by other musicians, including trumpeter Miles Davis and pianist Thelonious Monk.

As his career progressed, Coltrane and his music took on an increasingly spiritual dimension. Coltrane influenced innumerable musicians, and remains one of the most significant saxophonists in music history. He received many posthumous awards and recognitions, including canonization by the African Orthodox Church as Saint John William Coltrane and a special Pulitzer Prize in 2007. His second wife was pianist Alice Coltrane and their son Ravi Coltrane is also a saxophonist.

Biography

Early life and career (1926–1954)

Coltrane was born in his parents' apartment at 200 Hamlet Avenue, Hamlet, North Carolina on September 23, 1926. His father was John R. Coltrane and his mother was Alice Blair. He grew up in High Point, North Carolina, attending William Penn High School (now Penn-Griffin School for the Arts). Beginning in December 1938 Coltrane's aunt, grandparents, and father all died within a few months of one another, leaving John to be raised by his mother and a close cousin. In June 1943 he moved to Philadelphia. In September of that year his mother bought him his first saxophone, an alto. Coltrane played the clarinet and the alto horn in a community band before taking up the alto saxophone during high school. He had his first professional gigs in early to mid-1945 – a "cocktail lounge trio", with piano and guitar.

To avoid being drafted by the Army, Coltrane enlisted in the Navy on August 6, 1945, the day the first U.S. atomic bomb was dropped on Japan. He was trained as an apprentice seaman at Sampson Naval Training Station in upstate New York before he was shipped to Pearl Harbor, where he was stationed at Manana Barracks, the largest posting of African-American servicemen in the world. By the time he got to Hawaii, in late 1945, the Navy was already rapidly downsizing. Coltrane's musical talent was quickly recognized, though, and he became one of the few Navy men to serve as a musician without having been granted musicians rating when he joined the Melody Masters, the base swing band. As the Melody Masters was an all-white band, however, Coltrane was treated merely as a guest performer to avoid alerting superior officers of his participation in the band. He continued to perform other duties when not playing with the band, including kitchen and security details. By the end of his service, he had assumed a leadership role in the band. His first recordings, an informal session in Hawaii with Navy musicians, occurred on July 13, 1946. Coltrane played alto saxophone on a selection of jazz standards and bebop tunes.

After being discharged from his duties in the Navy, as a seaman first class in August 1946, Coltrane returned to Philadelphia, where he "plunged into the heady excitement of the new music and the blossoming bebop scene." After touring with King Kolax, he joined a Philly-based band led by Jimmy Heath, who was introduced to Coltrane's playing by his former Navy buddy, the trumpeter William Massey, who had played with Coltrane in the Melody Masters. In Philadelphia after the war, he studied jazz theory with guitarist and composer Dennis Sandole and continued under Sandole's tutelage through the early 1950s. Originally an altoist, in 1947 Coltrane also began playing tenor saxophone with the Eddie Vinson Band. Coltrane later referred to this point in his life as a time when "a wider area of listening opened up for me. There were many things that people like Hawk [Coleman Hawkins], and Ben [Webster] and Tab Smith were doing in the '40s that I didn't understand, but that I felt emotionally." A significant influence, according to tenor saxophonist Odean Pope, was the Philadelphia pianist, composer, and theorist Hasaan Ibn Ali. "Hasaan was the clue to ... the system that Trane uses. Hasaan was the great influence on Trane’s melodic concept."

An important moment in the progression of Coltrane's musical development occurred on June 5, 1945, when he saw Charlie Parker perform for the first time. In a DownBeat article in 1960 he recalled: "the first time I heard Bird play, it hit me right between the eyes." Parker became an early idol, and they played together on occasion in the late 1940s.

Contemporary correspondence shows that Coltrane was already known as "Trane" by this point, and that the music from some 1946 recording sessions had been played for trumpeter Miles Davis—possibly impressing him.

Coltrane was a member of groups led by Dizzy Gillespie, Earl Bostic and Johnny Hodges in the early to mid-1950s.

Miles and Monk period (1955–1957)

In the summer of 1955, Coltrane was freelancing in Philadelphia while studying with guitarist Dennis Sandole when he received a call from Davis. The trumpeter, whose success during the late forties had been followed by several years of decline in activity and reputation, due in part to his struggles with heroin, was again active and about to form a quintet. Coltrane was with this edition of the Davis band (known as the "First Great Quintet"—along with Red Garland on piano, Paul Chambers on bass, and Philly Joe Jones on drums) from October 1955 to April 1957 (with a few absences). During this period Davis released several influential recordings that revealed the first signs of Coltrane's growing ability. This quintet, represented by two marathon recording sessions for Prestige in 1956, resulted in the albums Cookin', Relaxin', Workin', and Steamin'. The "First Great Quintet" disbanded due in part to Coltrane's heroin addiction.

During the later part of 1957 Coltrane worked with Thelonious Monk at New York’s Five Spot Café, and played in Monk's quartet (July–December 1957), but, owing to contractual conflicts, took part in only one official studio recording session with this group. Coltrane recorded many albums for Prestige under his own name at this time, but Monk refused to record for his old label. A private recording made by Juanita Naima Coltrane of a 1958 reunion of the group was issued by Blue Note Records as Live at the Five Spot—Discovery!in 1993. A high quality tape of a concert given by this quartet in November 1957 was also found later, and was released by Blue Note in 2005. Recorded by Voice of America, the performances confirm the group's reputation, and the resulting album, Thelonious Monk Quartet with John Coltrane at Carnegie Hall, is widely acclaimed.

Blue Train, Coltrane's sole date as leader for Blue Note, featuring trumpeter Lee Morgan, bassist Paul Chambers, and trombonist Curtis Fuller, is often considered his best album from this period. Four of its five tracks are original Coltrane compositions, and the title track, "Moment's Notice", and "Lazy Bird", have become standards. Both tunes employed the first examples of his chord substitution cycles known as Coltrane changes.

Davis and Coltrane

Coltrane rejoined Davis in January 1958. In October of that year, jazz critic Ira Gitler coined the term "sheets of sound" to describe the style Coltrane developed during his stint with Monk and was perfecting in Davis' group, now a sextet. His playing was compressed, with rapid runs cascading in hundreds of notes per minute. He stayed with Davis until April 1960, working with alto saxophonist Cannonball Adderley; pianists Red Garland, Bill Evans, and Wynton Kelly; bassist Paul Chambers; and drummers Philly Joe Jones and Jimmy Cobb. During this time he participated in the Davis sessions Milestones and Kind of Blue, and the concert recordings Miles & Monk at Newport(1963) and Jazz at the Plaza (1958).

Period with Atlantic Records (1959-1961)

At the end of this period Coltrane recorded his first album as leader for Atlantic Records, Giant Steps (1959), which contained only his compositions. The album's title track is generally considered to have one of the most difficult chord progressions of any widely played jazz composition. Giant Steps utilizes Coltrane changes. His development of these altered chord progression cycles led to further experimentation with improvised melody and harmony that he continued throughout his career.

Coltrane formed his first quartet for live performances in 1960 for an appearance at the Jazz Gallery in New York City. After moving through different personnel including Steve Kuhn, Pete La Roca, and Billy Higgins, the lineup stabilized in the fall with pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Steve Davis, and drummer Elvin Jones. Tyner, from Philadelphia, had been a friend of Coltrane's for some years and the two men had an understanding that the pianist would join Coltrane when Tyner felt ready for the exposure of regularly working with him. Also recorded in the same sessions were the later released albums Coltrane's Sound (1964) and Coltrane Plays the Blues (1962).

Coltrane's first record with his new group was also his debut playing the soprano saxophone, the hugely successful My Favorite Things(1960). Around the end of his tenure with Davis, Coltrane had begun playing soprano, an unconventional move considering the instrument's neglect in jazz at the time. His interest in the straight saxophone most likely arose from his admiration for Sidney Bechet and the work of his contemporary, Steve Lacy, even though Davis claimed to have given Coltrane his first soprano saxophone. The new soprano sound was coupled with further exploration. For example, on the Gershwin tune "But Not for Me", Coltrane employs the kinds of restless harmonic movement used on Giant Steps (movement in major thirds rather than conventional perfect fourths) over the A sections instead of a conventional turnaround progression. Several other tracks recorded in the session utilized this harmonic device, including "26–2", "Satellite", "Body and Soul", and "The Night Has a Thousand Eyes".

First years with Impulse Records (1959–1961)

In May 1961, Coltrane's contract with Atlantic was bought out by the newly formed Impulse! Records label. An advantage to Coltrane recording with Impulse! was that it would enable him to work again with engineer Rudy Van Gelder, who had taped both his and Davis' Prestige sessions, as well as Blue Train. It was at Van Gelder's new studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey that Coltrane would record most of his records for the label.

By early 1961, bassist Davis had been replaced by Reggie Workman, while Eric Dolphy joined the group as a second horn around the same time. The quintet had a celebrated (and extensively recorded) residency in November 1961 at the Village Vanguard, which demonstrated Coltrane's new direction. It featured the most experimental music he had played up to this point, influenced by Indian ragas, the recent developments in modal jazz, and the burgeoning free jazz movement. John Gilmore, a longtime saxophonist with musician Sun Ra, was particularly influential; after hearing a Gilmore performance, Coltrane is reported to have said "He's got it! Gilmore's got the concept!" The most celebrated of the Vanguard tunes, the 15-minute blues, "Chasin' the 'Trane", was strongly inspired by Gilmore's music.

During this period, critics were fiercely divided in their estimation of Coltrane, who had radically altered his style. Audiences, too, were perplexed; in France he was booed during his final tour with Davis. In 1961, Down Beat magazine indicted Coltrane and Dolphy as players of "Anti-Jazz", in an article that bewildered and upset the musicians. Coltrane admitted some of his early solos were based mostly on technical ideas. Furthermore, Dolphy's angular, voice-like playing earned him a reputation as a figurehead of the "New Thing" (also known as "Free Jazz" and "Avant-Garde") movement led by Ornette Coleman, which was also denigrated by some jazz musicians (including Davis) and critics. But as Coltrane's style further developed, he was determined to make each performance "a whole expression of one's being".

Classic Quartet period (1962–1965)

In 1962, Dolphy departed and Jimmy Garrison replaced Workman as bassist. From then on, the "Classic Quartet", as it came to be known, with Tyner, Garrison, and Jones, produced searching, spiritually driven work. Coltrane was moving toward a more harmonically static style that allowed him to expand his improvisations rhythmically, melodically, and motivically. Harmonically complex music was still present, but on stage Coltrane heavily favored continually reworking his "standards": "Impressions", "My Favorite Things", and "I Want to Talk About You".

The criticism of the quintet with Dolphy may have affected Coltrane. In contrast to the radicalism of his 1961 recordings at the Village Vanguard, his studio albums in the following two years (with the exception of Coltrane, 1962, which featured a blistering version of Harold Arlen's "Out of This World") were much more conservative. He recorded an album of ballads and participated in collaborations with Duke Ellington on the album Duke Ellington and John Coltrane and with deep-voiced ballad singer Johnny Hartman on an eponymous co-credited album. The album Ballads (recorded 1961–62) is emblematic of Coltrane's versatility, as the quartet shed new light on old-fashioned standards such as "It's Easy to Remember". Despite a more polished approach in the studio, in concert the quartet continued to balance "standards" and its own more exploratory and challenging music, as can be heard on the Impressions (recorded 1961–63), Live at Birdland and Newport '63 (both recorded 1963). Impressions consists of two extended jams including the title track along with "Dear Old Stockholm", "After the Rain" and a blues. Coltrane later said he enjoyed having a "balanced catalogue."

The Classic Quartet produced their best-selling album, A Love Supreme, in December 1964. A culmination of much of Coltrane's work up to this point, this four-part suite is an ode to his faith in and love for God. These spiritual concerns characterized much of Coltrane's composing and playing from this point onwards—as can be seen from album titles such as Ascension, Om and Meditations. The fourth movement of A Love Supreme, "Psalm", is, in fact, a musical setting for an original poem to God written by Coltrane, and printed in the album's liner notes. Coltrane plays almost exactly one note for each syllable of the poem, and bases his phrasing on the words. The album was composed at Coltrane's home in Dix Hills on Long Island.

The quartet played A Love Supreme live only once—in July 1965 at a concert in Antibes, France.

Avant-garde jazz and the second quartet (1965–1967)

In his late period, Coltrane showed an increasing interest in avant-garde jazz, purveyed by Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, Sun Ra and others. In developing his late style, Coltrane was especially influenced by the dissonance of Ayler's trio with bassist Gary Peacock, who had also worked with Paul Bley, and drummer Sunny Murray, whose playing was honed with Cecil Taylor as leader. Coltrane championed many younger free jazz musicians such as Archie Shepp, and under his influence Impulse! became a leading free jazz record label.

After A Love Supreme was recorded, Ayler's style became more prominent in Coltrane's music. A series of recordings with the Classic Quartet in the first half of 1965 show Coltrane's playing becoming increasingly abstract, with greater incorporation of devices like multiphonics, utilization of overtones, and playing in the altissimo register, as well as a mutated return of Coltrane's sheets of sound. In the studio, he all but abandoned his soprano to concentrate on the tenor saxophone. In addition, the quartet responded to the leader by playing with increasing freedom. The group's evolution can be traced through the recordings The John Coltrane Quartet Plays, Living Space, Transition (both June 1965), New Thing at Newport (July 1965), Sun Ship (August 1965), and First Meditations (September 1965).

In June 1965, he went into Van Gelder's studio with ten other musicians (including Shepp, Pharoah Sanders, Freddie Hubbard, Marion Brown, and John Tchicai) to record Ascension, a 40-minute piece that included solos by the young avant-garde musicians (as well as Coltrane), and was controversial primarily for the collective improvisation sections that separated the solos. After recording with the quartet over the next few months, Coltrane invited Sanders to join the band in September 1965. While Coltrane frequently used over-blowing as an emotional exclamation-point, Sanders would overblow entire solos, resulting in a constant screaming and screeching in the altissimo range of the instrument.

Adding to the quartet

By late 1965, Coltrane was regularly augmenting his group with Sanders and other free jazz musicians. Rashied Ali joined the group as a second drummer. This was the end of the quartet; claiming he was unable to hear himself over the two drummers, Tyner left the band shortly after the recording of Meditations. Jones left in early 1966, dissatisfied by sharing drumming duties with Ali. Both Tyner and Jones subsequently expressed displeasure in interviews, after Coltrane's death, with the music's new direction, while incorporating some of the free-jazz form's intensity into their own solo projects.

There is speculation that in 1965 Coltrane began using LSD, informing the "cosmic" transcendence of his late period. After the departure of Jones and Tyner, Coltrane led a quintet with Sanders on tenor saxophone, his second wife Alice Coltrane on piano, Garrison on bass, and Ali on drums. Coltrane and Sanders were described by Nat Hentoff as "speaking in tongues". When touring, the group was known for playing very lengthy versions of their repertoire, many stretching beyond 30 minutes and sometimes being an hour long. Concert solos for band members often extended beyond fifteen minutes.

The group can be heard on several concert recordings from 1966, including Live at the Village Vanguard Again! and Live in Japan. In 1967, Coltrane entered the studio several times; though pieces with Sanders have surfaced (the unusual "To Be", which features both men on flutes), most of the recordings were either with the quartet minus Sanders (Expression and Stellar Regions) or as a duo with Ali. The latter duo produced six performances that appear on the album Interstellar Space.

Death and funeral

Coltrane died of liver cancer at Huntington Hospital on Long Island on July 17, 1967, at the age of 40. His funeral was held four days later at St. Peter's Lutheran Church in New York City. The service was opened by the Albert Ayler Quartet and closed by the Ornette Coleman Quartet. Coltrane is buried at Pinelawn Cemetery in Farmingdale, New York.

One of his biographers, Lewis Porter, has suggested that the cause of Coltrane's illness was hepatitis, although he also attributed the disease to Coltrane's heroin use. In a 1968 interview Ayler claimed that Coltrane was consulting a Hindu meditative healer for his illness instead of Western medicine, although Alice Coltrane later denied this.

Coltrane's death surprised many in the musical community who were not aware of his condition. Davis said that "Coltrane's death shocked everyone, took everyone by surprise. I knew he hadn't looked too good... But I didn't know he was that sick—or even sick at all."

Personal life and religious beliefs

In 1955, Coltrane married Naima (born Juanita Grubbs). Naima Coltrane, who was already a Muslim convert, heavily influenced his spirituality. When they married, Naima had a five-year-old daughter named Antonia, later named Saeeda. Coltrane adopted Saeeda. Coltrane met Naima at the home of bassist Steve Davis in Philadelphia. The love ballad he wrote to honor his wife, "Naima" was Coltrane's favorite composition. In 1956 the couple left Philadelphia with their six-year-old daughter in tow and moved to New York City. In August 1957, Coltrane, Naima and Saeeda moved into an apartment on 103d St. and Amsterdam Ave. in New York, near Central Park West. A few years later, John and Naima Coltrane purchased a home on Long Island on Mexico Street. This is the house where they would eventually break up in 1963. Said Naima about the break in J.C. Thomas's Chasin' the Trane: "I could feel it was going to happen sooner or later, so I wasn't really surprised when John moved out of the house in the summer of 1963. He didn't offer any explanation. He just told me there were things he had to do, and he left only with his clothes and his horns. He stayed in a hotel sometimes, other times with his mother in Philadelphia. All he said was, 'Naima, I'm going to make a change.' Even though I could feel it coming, it hurt, and I didn't get over it for at least another year." But Coltrane kept a close relationship with Naima, even calling her in 1964 to tell her that 90% of his playing would be prayer. Coltrane would be dead in four years, but he always kept in touch with her. Naima brought serenity and a calmness into his life. All who knew Naima described her gentle spirit and serenity. They remained in touch until his death in 1967. Naima Coltrane died of a heart attack in October 1996.

Coltrane and Naima were officially divorced in 1966. In 1963, Coltrane met pianist Alice McLeod. He and Alice moved in together and had two sons before he was "officially divorced from Naima in 1966, at which time John and Alice were immediately married." John Jr. was born in 1964, Ravi in 1965, and Oranyan ("Oran") in 1967. According to the musician and author Peter Lavezzoli, "Alice brought happiness and stability to John's life, not only because they had children, but also because they shared many of the same spiritual beliefs, particularly a mutual interest in Indian philosophy. Alice also understood what it was like to be a professional musician."

Coltrane was born and raised in a Christian home, and was influenced by religion and spirituality from childhood. His maternal grandfather, the Reverend William Blair, was a minister at an African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in High Point, North Carolina, and his paternal grandfather, the Reverend William H. Coltrane, was an A.M.E. Zion minister in Hamlet, North Carolina. Critic Norman Weinstein noted the parallel between Coltrane's music and his experience in the southern church, which included practicing music there as a youth.

In 1957, Coltrane had a religious experience that may have helped him overcome the heroin addiction and alcoholism he had struggled with since 1948. In the liner notes of A Love Supreme, Coltrane states that, in 1957, "I experienced, by the grace of God, a spiritual awakening which was to lead me to a richer, fuller, more productive life. At that time, in gratitude, I humbly asked to be given the means and privilege to make others happy through music." The liner notes appear to mention God in a Universalist sense, and do not advocate one religion over another. Further evidence of this universal view regarding spirituality can be found in the liner notes of Meditations(1965), in which Coltrane declares, "I believe in all religions."

After A Love Supreme, many of the titles of Coltrane's songs and albums were linked to spiritual matters: Ascension, Meditations, Om, Selflessness, "Amen", "Ascent", "Attaining", "Dear Lord", "Prayer and Meditation Suite", and "The Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost". Coltrane's collection of books included The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, the Bhagavad Gita, and Paramahansa Yogananda's Autobiography of a Yogi. The last of these describes, in Lavezzoli's words, a "search for universal truth, a journey that Coltrane had also undertaken. Yogananda believed that both Eastern and Western spiritual paths were efficacious, and wrote of the similarities between Krishna and Christ. This openness to different traditions resonated with Coltrane, who studied the Qur'an, the Bible, Kabbalah, and astrology with equal sincerity." He also explored Hinduism, Jiddu Krishnamurti, African history, the philosophical teachings of Plato and Aristotle, and Zen Buddhism.

In October 1965, Coltrane recorded Om, referring to the sacred syllable in Hinduism, which symbolizes the infinite or the entire Universe. Coltrane described Om as the "first syllable, the primal word, the word of power". The 29-minute recording contains chants from the Hindu Bhagavad Gita and the Buddhist Tibetan Book of the Dead, and a recitation of a passage describing the primal verbalization "om" as a cosmic/spiritual common denominator in all things.

Coltrane's spiritual journey was interwoven with his investigation of world music. He believed not only in a universal musical structure that transcended ethnic distinctions, but in being able to harness the mystical language of music itself. Coltrane's study of Indian music led him to believe that certain sounds and scales could "produce specific emotional meanings." According to Coltrane, the goal of a musician was to understand these forces, control them, and elicit a response from the audience. Coltrane said: "I would like to bring to people something like happiness. I would like to discover a method so that if I want it to rain, it will start right away to rain. If one of my friends is ill, I'd like to play a certain song and he will be cured; when he'd be broke, I'd bring out a different song and immediately he'd receive all the money he needed."

Religious figure

After Coltrane's death, a congregation called the Yardbird Temple in San Francisco began worshiping him as God incarnate. The group was named after Charlie Parker, whom they equated to John the Baptist. The congregation later became affiliated with the African Orthodox Church; this involved changing Coltrane's status from a god to a saint. The resultant St. John Coltrane African Orthodox Church, San Francisco is the only African Orthodox church that incorporates Coltrane's music and his lyrics as prayers in its liturgy.

Samuel G. Freedman wrote in a New York Times article that "the Coltrane church is not a gimmick or a forced alloy of nightclub music and ethereal faith. Its message of deliverance through divine sound is actually quite consistent with Coltrane's own experience and message." Freedman also commented on Coltrane's place in the canon of American music:

In both implicit and explicit ways, Coltrane also functioned as a religious figure. Addicted to heroin in the 1950s, he quit cold turkey, and later explained that he had heard the voice of God during his anguishing withdrawal. [...] In 1966, an interviewer in Japan asked Coltrane what he hoped to be in five years, and Coltrane replied, "A saint."

Coltrane is depicted as one of the 90 saints in the Dancing Saints icon of St. Gregory of Nyssa Episcopal Church in San Francisco. The icon is a 3,000-square-foot (280 m2) painting in the Byzantine iconographic style that wraps around the entire church rotunda. It was executed by Mark Dukes, an ordained deacon at the Saint John Coltrane African Orthodox Church, who painted other icons of Coltrane for the Coltrane Church. Saint Barnabas Episcopal Church in Newark, New Jersey, included Coltrane on their list of historical black saints and made a "case for sainthood" for him in an article on their former website.

Documentaries on Coltrane and the church include Alan Klingenstein's The Church of Saint Coltrane (1996), and a 2004 program presented by Alan Yentob for the BBC.

Instruments

In 1947, when he joined King Kolax's band, Coltrane switched to tenor saxophone, the instrument he became known for playing primarily. Coltrane's preference for playing melody higher on the range of the tenor saxophone (as compared to, for example, Coleman Hawkins or Lester Young) is attributed to his start and training on the alto horn and clarinet; his "sound concept" (manipulated in one's vocal tract—tongue, throat) of the tenor was set higher than the normal range of the instrument.

In the early 1960s, during his engagement with Atlantic Records, he increasingly played soprano saxophone as well. Toward the end of his career, he experimented with flute in his live performances and studio recordings (Live at the Village Vanguard Again!, Expression). After Dolphy died in June 1964, his mother is reported to have given Coltrane his flute and bass clarinet.

Coltrane's tenor (Selmer Mark VI, serial number 125571, dated 1965) and soprano (Selmer Mark VI, serial number 99626, dated 1962) saxophones were auctioned on February 20, 2005 to raise money for the John Coltrane Foundation. The soprano raised $70,800 but the tenor remained unsold.

Legacy

The influence Coltrane has had on music spans many genres and musicians. Coltrane's massive influence on jazz, both mainstream and avant-garde, began during his lifetime and continued to grow after his death. He is one of the most dominant influences on post-1960 jazz saxophonists and has inspired an entire generation of jazz musicians.

In 1965, Coltrane was inducted into the Down Beat Jazz Hall of Fame. In 1972, A Love Supreme was certified gold by the RIAA for selling over half a million copies in Japan. This album, as well as My Favorite Things, was certified gold in the United States in 2001. In 1982 he was awarded a posthumous Grammy for "Best Jazz Solo Performance" on the album Bye Bye Blackbird, and in 1997 he was awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante named Coltrane one of his 100 Greatest African Americans. Coltrane was awarded a special Pulitzer Prize in 2007 citing his "masterful improvisation, supreme musicianship and iconic centrality to the history of jazz." He was inducted into the North Carolina Music Hall of Fame in 2009.

His widow, Alice Coltrane, after several decades of seclusion, briefly regained a public profile before her death in 2007. A former home, the John Coltrane House in Philadelphia, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1999. His last home, the John Coltrane Home in the Dix Hills district of Huntington, New York, where he resided from 1964 until his death, was added to the National Register of Historic Places on June 29, 2007. One of their sons, Ravi Coltrane, named after the sitarist Ravi Shankar, is also a saxophonist.

The Coltrane family reportedly possesses much more unreleased music, mostly mono reference tapes made for the saxophonist, and, as with the 1995 release Stellar Regions, master tapes that were checked out of the studio and never returned. The parent company of Impulse!, from 1965 to 1979 known as ABC Records, purged much of its unreleased material in the 1970s. Lewis Porter has stated that Alice Coltrane intended to release this music, but over a long period of time; Ravi Coltrane is responsible for reviewing the material.

Chasing Trane: The John Coltrane Documentary, is a 2016 American film directed by John Scheinfeld. Narrated by Denzel Washington, the film chronicles the life of Coltrane in his own words, and includes interviews with such admirers as Wynton Marsalis, Sonny Rollins, and Cornel West.

Discography

The discography below lists albums conceived and approved by Coltrane as a leader during his lifetime. It does not include his many releases as a sideman, sessions assembled into albums by various record labels after Coltrane's contract expired, sessions with Coltrane as a sideman later reissued with his name featured more prominently, or posthumous compilations, except for the one he approved before his death. See main discography link above for full list.

Prestige and Blue Note Records

Coltrane (debut solo LP) (1957)

Blue Train (1957)

John Coltrane with the Red Garland Trio (1958)

Soultrane (1958)

Atlantic Records

Giant Steps (first album entirely of Coltrane compositions) (1960)

Coltrane Jazz (first appearance by McCoy Tyner and Elvin Jones) (1961)

My Favorite Things (1961)

Olé Coltrane (features Eric Dolphy, compositions by Coltrane and Tyner) (1961)

Impulse! Records

Africa/Brass (brass arranged by Tyner and Dolphy) (1961)

Live! at the Village Vanguard (features Dolphy, first appearance by Jimmy Garrison) (1962)

Coltrane (first album to solely feature the "classic quartet") (1962)

Duke Ellington & John Coltrane (1963)

Ballads (1963)

John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman (1963)

Impressions (1963)

Live at Birdland (1964)

Crescent (1964)

A Love Supreme (1965)

The John Coltrane Quartet Plays (1965)

Ascension (quartet plus six horns and bass, one 40' track collective improvisation) (1966)

New Thing at Newport (live album split with Archie Shepp) (1966)

Kulu Sé Mama (1966)

Meditations (quartet plus Pharoah Sanders and Rashied Ali) (1966)

Live at the Village Vanguard Again! (1966)

Expression (posthumous and final Coltrane-approved release; one track features Coltrane on flute) (1967)

Wikipedia

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Exam

Best Music Moment of 2021

Code: lotta miles behind the wheel in '21 and my favorite soundtrack was probably rolling across louisiana at sunset with car wheels on a gravel road playing as i scarfed a double whopper meal - also enjoyable was bombing home from dallas in the rain to the comforting sounds of 14 hours of dick's picks. Arden woke up during weather report suite and said "we already heard this one". she was right, i went from DP 7 to DP 12 and that medley lives on both. - on 08/29/2021 at 3:07 p.m. CDT i texted bin "junya is 🔥” - i lost my mind to the sweet sounds coming out of the DJJJJD wedding reception sound system. ((could that be posted to the tumblr?)) (editor’s note:)

JD: Aprilish: Saw Philip Glass walking up 2nd Avenue. August: Endless gems rolling off the playlist while cutting loose Friday night in Hunter, NY. September: Loading up 20 bucks wortha digital jukebox tunes in the Wisconsin Dells, prompting the bar to immediately ask a guy to start DJ’ing who kicked things off with Toby Keith’s “Courtesy of the Red, White, and Blue.” October: Screening of Ed Lachman’s “Songs For Drella” film at the New York Film Fest prior to the Velvet Underground doc. October: Hard to beat the first dance and “House of Jealous Lovers” hallway throwdown. November: Mondo cathartic release upon Parquet Courts ripping into “Light Up Gold” at my first show in nigh on two years.

Best Shows Seent in 2021

JD: 1 and Only. PQ Boys at The Stone Pony on the Jersey Shore

Codemin: i talked through that whole lcd amazon show

Confession of 2021

JD: I let “Letter of Intent” out of cancellation jail.

Code: the only 2021 albums that i listened to prior to mid-october were Sports Coach in january and a bootleg copy of the first donda show

Biggest Disappointment of 2021

Code: still no dom news to speak of and yet i am still hopeful - man, that was a lot of money to spend on a pavement ticket - second year in a row with no stones while waiting for the canons

JD: Musgraves

Most Overrated of 2021

Cig: being tuned in

JD: Licorice Pizza

Make It Stop 2021

Code: the last third of "believe what i say"

JD: Variants

Biggest TBH Regret of 2021

Codemin: i forgot to watch the pqc stream. reckon the best chance i'll have to hear the dear tommy album will be to start rooting for a posthumous release.

JD: Didn’t even try to catch an acoustic Beck show that sounded like a nostalgic delight.

Detective Murtaugh of 2021

Code: SNL musical guests.

JD:

youtube

Resolution for 2021 Status

JD: - Massively reduce my ‘news’ consumption to free up more time to spin tunes and smell the roses. - Get vaxed and get partying. How It Went: - Managed to cut the consumption of ‘news’ and news. Still need to work on the tunes and the roses. - Keep the boosters coming.

Code: see a live music concert How It Went: ain’t caught but a one again

Resolution for 2022

JD: Got rid of the news, time to work on the podcasts.

Codem: make just one classic playlist - listen to more oral histories of bands I like

Most Anticipated of 2022

JD: Aldous Harding, Jenny Hval, Horsegirl

Code: an EMA, mitski and/or dom should be coming around soon, right? and ovlov is going to tour that album, ain't they?

1 note

·

View note

Note

If I may, it honestly depends on your approach and belief system for the most part. The Greeks and the Romans used the term Apotheosis, which we tend to associate more with art these days. For the Greeks these honors were usually given to war heroes and kings, but they didn't seem to put you on par with the gods of Olympus. Sometimes they were given while the person was still living like Alexander the Great, but were also awarded after death.

In Roman Catholic tradition there are saints, which are not considered gods but are beings who have reached a kind of divinity through good deeds, miracles and (more often than not) martyrdom. By Roman Catholic law saints must be approved by the leaders of the church in a process known as "Canonization", however there are "unofficial saints" which can include humans, animals and even objects.

In Grant Morrison's The Invisibles, King Mob ends up seeking help from the spirit of famous Beatle, John Lennon, whom the character describes as a "godhead of living music". Morrison (who is a Chaos Magician) based this on their own ritual:

"I decided to treat John Lennon as a god," Morrison told the Meltdown crowd, explaining how (they) created a circle around (their) Beatles' albums, donned a paisley shirt and Beatle boots and experienced a vision of Lennon."

As you can see there are multiple traditions, ideas and approaches to god hood. If you are seeking a way for society to view you as a god, I would argue that, unless you just declare yourself one (don't do that), you must be publicly known and maybe really good at something to the point where a cult of worship has been built around you. So not too far off from modern celebrity really.

If you simply want to achieve "godhood" in your practice, then I would suggest asking the questions:

- what is a god?

- what is the function of a god?

And

- what would be the purpose of ascending to godhood?

In my practice such things could be possible I suppose, but the idea isn't really one that tickles my fancy. In my practice to be a god one couldn't be human, so probably dead, and saints become saints posthumously, so also dead; so neither are really appealing to me.

Hey there Chicken, I hope you're doing well :). This might be hubris, but how would an ordinary human go about obtaining godhood? It's an idea I've been musing on and I'd like to hear your take

Toodles!

I don't believe its possible.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

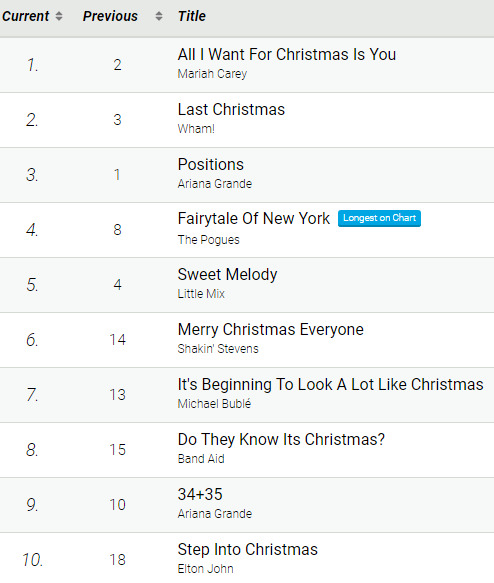

REVIEWING THE CHARTS: 12/12/2020

For the first time ever after being released in 1994, Mariah Carey’s “All I Want for Christmas is You” has hit #1 on the UK Singles Chart, like it did on the US Billboard Hot 100 last year and will probably do so this year. This is a really short week full of nothing so that might be the biggest story here, and the song deserves it. It’s a great song and it’s genuinely massive. I wonder how newer songs like Kelly Clarkson’s “Underneath the Tree” will be able to enter themselves into the Christmas canon after Mariah Carey proved that it can be done with modern pop. Well, that’s not for us to find out today, because this is REVIEWING THE CHARTS.

Rundown

Like I said in the introduction, this is far from a busy week, which almost surprises me. Sure, nothing important was released – except that Shawn Mendes album which flopped remarkably and debuted at #12 on the Albums Chart this week – but I did expect another festive flood of holiday tunes. To my surprise, this didn’t happen or at least not to the extent that I assumed it would. Sure, we still have a lot of Christmas songs replacing newer pop songs that had already been in the charts, ‘tis the season, but this week only had five notable drop-outs from the UK Top 75, and none of those are that notable. I guess “Ain’t it Different” by Headie One featuring AJ Tracey and Stormzy, one of the biggest hip-hop hits of the year, dropping out is a pretty big deal, but otherwise we just have “Diamonds” by Sam Smith, “UFO” by D-Block Europe and Aitch, “Come Over” by Jorja Smith and Popcaan, and I guess “Chingy (It’s Whatever)” by Digga D. All of these songs are recent and might have a rebound after the Christmas season is over, but I do have my concerns about the longevity of these songs, particularly because of how, you know, none of them are actually good. I guess now we could discuss some of our biggest fallers, which are of some quantity considering the season, so I’ll run these off quickly: “Midnight Sky” by Miley Cyrus at #15, “Therefore I Am” by Billie Eilish at #18, “Levitating” by Dua Lipa at #20, “you broke me first” by Tate McRae at #21 (these last four songs were all in the top 10 last week, by the way), “Prisoner” by Miley Cyrus featuring Dua Lipa at #22, “Really Love” by KSI featuring Craig David and Digital Farm Animals at #31, “Monster” by Shawn Mendes and Justin Bieber continuing to free-fall to #33, “Train Wreck” by James Arthur at #35, “Get Out My Head” by Shane Codd at #37, “Mood” by 24kGoldn and iann dior at #38, “Head & Heart” by Joel Corry and MNEK at #40, “Lemonade” by Internet Money and Gunna featuring NAV and Don Toliver at #45, “Dynamite” by BTS at #46, “Lonely” by Justin Bieber and benny blanco at #52, “See Nobody” by Wes Nelson and Hardy Caprio at #54, “i miss u” by Jax Jones and Au/Ra at #56, “What You Know Bout Love” by the late Pop Smoke at #57, “Sunflower (Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse)” by Post Malone and Swae Lee at #61, “All You’re Dreaming Of” by Liam Gallagher off the debut at #62 (our biggest fall this week), same goes for “No Time for Tears” by Nathan Dawe and Little Mix at #71 and some long-lasting hits right at the tail end of the chart: “Princess Cuts” by Headie One featuring Young T & Bugsey at #72, “WAP” by Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion at #73, and “Looking for Me” by Diplo, Paul Woodford and Kareen Lomax at #74. We do have a lot of Christmas gains and returning entries, so before we get to anything non-Christmas, let’s round off those real quick. Returning to the chart are “Santa’s Coming for Us” by Sia at #69, “Let it Snow! Let it Snow! Let it Snow!” by Frank Sinatra at #66 and “White Christmas” by Bing Crosby at #63. There are a lot more of our notable gains though: “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” by Sam Smith at #65, “Cozy Little Christmas” by Katy Perry at #58, “Love is a Compass” by Griff at #53, “Feliz Navidad” by José Feliciano at #51, “Christmas Lights” by Coldplay at #49 (the biggest gain and deservedly so), “Santa Baby” by Kylie Minogue at #44, “Let it Snow! Let it Snow! Let it Snow!” by Dean Martin at #43, “Sleigh Ride” by the Ronettes at #41, “Mistletoe” by Justin Bieber at #36, “Wonderful Christmastime” by Paul McCartney at #32, “Holly Jolly Christmas” by Michael Bublé at #30, “Happy Xmas (War is Over)” by John Lennon and Yoko Ono with the Plastic Ono Band featuring the Harlem Community Choir at #29, “It’s the Most Wonderful Time of the Year” by Andy Williams at #28, “Merry Xmas Everybody” by Slade at #26, “One More Sleep” by Leona Lewis at #25, “Driving Home for Christmas” by Chris Rea at #17, “This Christmas” by Jess Glynne at #13, “Santa Tell Me” by Ariana Grande at #11, “Step into Christmas” by Elton John at #10, “Do They Know it’s Christmas?” by Band Aid at #8, “It’s Beginning to Look a Lot Like Christmas” by Michael Bublé at #7 and finally, “Merry Christmas Everyone” by Shakin’ Stevens at #6. That’s not all of our gains and returning entries though, as we do have some peculiar events outside of the Christmas singles. First of all, “Blinding Lights” by The Weeknd is up to #39 thanks to a remix with ROSALIA, and secondly, “WITHOUT YOU” by The Kid LAROI returns to the chart at #23. I have no idea why or how this happened but I want it gone as quickly as possible. Anyway, we have three new arrivals to talk about, none of which are particularly interesting, so let’s get on with those.

NEW ARRIVALS

#75 – “Real Stuff” – Juice WRLD and benny blanco

Produced by Dylan Brady, Jack Karaszewski, Henry Kwapis, Cashmere Cat and benny blanco

The song’s not called “Real Stuff”, but come on, this is a family show. About a year ago, Jarad Higgins, or Juice WRLD, died tragically at age 21 of a substance abuse-related seizure. Naturally, since it’s Juice and his label we’re talking about, they’re still pumping out unreleased content. Two songs of this nature were released around this time, one with Kid LAROI and Kim Petras we’ll probably see next week and even higher on the chart, but first of all, an emo rap anthem produced by benny blanco and Dylan Brady of 100 gecs. I mean, okay, sure, it is 2020 after all. Blanco posted on social media about how this was his first ever recorded song with Juice when they had a studio session before Juice was that recognised, and before he was signed, they cooked up a lot of music. This makes it surprising how it didn’t leak after all this time but it shouldn’t matter. What’s important is the quality of the song and since this is a genuine song from a real-life studio session, it’s not nearly as insincere and cynical as some of the other posthumous projects from Juice. Sadly, I don’t this makes it any good. The clicking, stuttering trap beat doesn’t sound bad with his bumping 808s but doesn’t complement the acoustic guitar strumming or even Juice as much as it should – and this is really early Juice, so it’s not like he’s mastered his style of emo-reminiscent self-loathing and painful, drug-induced relationship ramblings. It’s not even as catchy as Juice would start to be later on, so it is just a primitive version of whatever Juice’s sound would end up being. Sadly, we won’t get more development from the guy other than these cheap releases, and if benny blanco guided Juice more into a lane he’s comfortable with and more importantly, Juice was still alive, this could be an example of something great yet to flourish but since his incomplete discography of disposable output is all we have to evaluate, it makes Juice’s work much more difficult to appreciate, especially posthumously, where every throwaway bar about substance abuse has this haunting, unnerving impact it didn’t have before. Oh, and I really like the first verse, which is just aimless flexing but with more charm than he usually has, and with some promises of extra detail he could have gone into, before of course, it switches onto a different topic, an issue plaguing much of the man’s work. In conclusion, the song is fine but I don’t think I can listen to Juice’s work, complete or incomplete, released when he was alive or scrambled posthumously, without feeling sad or just having this contempt for the yes-men who surrounded him. Rest in peace, Juice.

#67 – “Oh Santa!” – Mariah Carey

Remixed by Ariana Grande and Jennifer Hudson

Produced by Scott M. Riesett, Marc Shaiman and Daniel Moore II

“Oh Santa!” is an original Christmas tune Mariah Carey wrote and released with Jermaine Dupri in 2010, for her second Christmas album, aptly titled Merry Christmas II You. The song wasn’t a success, and it couldn’t live up to “All I Want for Christmas is You”, which is fine. We don’t need more Mariah Carey songs in the Christmas canon if we already have an absolutely perfect one at the top of the charts, but if she wants to start flooding the market, I guess it’s best to do it with two experts at vocals, because for her little Apple TV Christmas special, she’s bought along Jennifer Hudson and Ariana Grande for whatever the triple version of a duet is. I assumed this would have been a returning entry because it’s a remix but the original never charted in the UK so I’ll have to talk about both here, and, well, there’s a reason “All I Want for Christmas is You” has never been replicated in terms of success and just sheer quality. I talked about this on my best list but there’s never been a song I feel is so ubiquitous of modern Christmas in the current millennium than “All I Want for Christmas is You”, an outright rejection of festive commercialism in preference of just having her significant other around for the holidays. “Oh Santa!” has a similar presence, but in this one, Mariah Carey’s asking for Santa Claus himself to wrap her crush in wrapping paper and gift it to her for Christmas, with a lot less of the warm intimacy of the classic song and without any of the charm. The 2010 version has this really gross drum machine and a lot of cheerleader-type chanting and clapping that starts off as really ugly – and the chanting still is – but honestly makes a pretty good backing for Mariah sliding over the beat with vocals that may not be as impressive as her best but are just as smooth as they should be over a more coy, low-key festive instrumental. My main issue with it is pace because whilst it is a short song, and she does treat us to some whistle notes and runs by the end, it just fades out and the instrumental doesn’t feel like it goes anywhere, making this song sound slow as all hell. If anything, this remix sounds dated, especially with the more modern vocal production with Ariana Grande and Jennifer Hudson, both in a constant struggle with Mariah for getting a word in, to the point where Hudson over-sells her belting and Grande is the only voice recognisable enough here that actually works. Half way in, the song completely devolves into a bridge of aimless runs and “harmonising” from everyone with that ugly chanting, seemingly unchanged from the original. Yeah, this isn’t pretty, and if anything is a remix of an older song that needed a lot more updates to make it work in a 2020 context and fits all of these incredible vocalists in. This could have been great with an original song that was completed to flatter everyone, but there’s too many cooks in the Christmas kitchen here and the cookies being made are being overcooked. Sure, let’s go with that analogy. Next.

#59 – “Daily Duppy – Part 1” – Digga D

Produced by AceBeatz

It’s not uncommon for freestyles to chart in the UK, particularly important British hip-hop tastemaker GRM Daily and their “Daily Duppy” freestyles, which have been the break-out moment for many rappers like Aitch or DIgDat because they reach a level of viral fame and attention that music videos can’t do as well, mostly because of the platform just letting them spit bars over usually decent beats. Digga D was actually opposed to doing one and even sparked some kind of feud with GRM Daily but that dried up soon enough for him to provide them with two “Daily Duppy” freestyles on two different beats but with one cold verse each. Only the first part charted here, as you’d expect, but I’ll cover both. The first part, produced by Ace Beats, has a pretty nice pitch-shifted vocal sample quickly abandoned for the same sample pitched differently, and then it comes back, under a pretty messy drill beat, and whilst Digga D’s riding it really well, I find it hard to be convinced by his delivery here, which is either checked-out or edited so heavily it’s bizarre. I mean, I thought this was a freestyle, right? He can just spit bars over the beat and it’ll be fine, but they add all these stuttering effects, ad-libs and censors that censor pointless words like “juice” but keep actual vulgarities completely intact, as well as censoring some locations but not others. It takes me out of the whole verse, honestly, even if some of it is some pretty slick and nice wordplay, with some funny punchlines and the typical pop culture references you can expect from the more lighthearted of UK drill. I know that people like to make references to their guns in ways that make them even more threatening and eerie, but just like 21 Savage calling his Draco a paedophile, I don’t think Digga D saying that he grooms young ethnic minority boys to sell drugs is “hard” or even enjoyable. I just think it’s pretty awful. I said I’d talk about the second part here, but honestly, it’s a lot less interesting, with a more trap-adjacent beat and boring synths instead of the cool vocal sample. Admittedly, it sounds more like a “freestyle”, but he wastes the moment where the beat cuts out by just rapping filler, and the quarantine references are going to date this, so, yeah, whilst I’m impressed by Digga D’s flow switches here, I’m not a fan of really anything else.

Conclusion

There’s not enough here to give an Honourable or Dishonourable Mention, so I’ll just have to give out the big ones... but everything here is mediocre, so I’m left with not a lot of content at all. I guess Best of the Week can go to the late Juice WRLD and benny blanco for “Real Stuff”, almost purely out of respect, even if the song is just listenable. Worst of the Week was really a toss-up, but I think I’ll give it to “Oh Santa!” by Mariah Carey featuring Ariana Grande and Jennifer Hudson for being such a waste of talent and potential. Only time will tell what comes next week, but I predict a busy one with Christmas music, Taylor Swift and hopefully Kid Cudi, but we’ll see really. I’m going to hazard a guess that we’ll get at least two songs from Taylor and only the Skepta track from Cudi, but I think we could easily have three from each. Here’s this week’s top 10:

You can follow me on Twitter @cactusinthebank for Imanbek fan-girling and thank you for reading, I’ll see you next week!

0 notes

Text

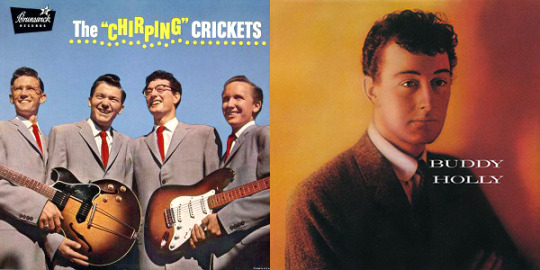

Not Fade Away: A Look Back at Buddy Holly and The Crickets

The relevance of musical aptitude has waxed and waned with what the general public has decided is in fashion. As a result, one could argue that the mainstream musical landscape has seen yearlong talent droughts more than once or twice before, and it would not be a difficult point to argue. Coinciding with the explosion of MTV, artist and band members had to present evocative visuals and in no uncertain terms be physically attractive-- talent was an added bonus. In the 1990s, feelings were "in," and it became trend to be introspective; in 2017, it is social media which dictates an artist's commercial successes. However, at the earliest on-set of rock and roll, the rules for pop music presentation were still developing, with racial politics and an icy reception from the jazz industry playing an important role.

Just shortly before four unknown young men from Liverpool, England would take the world by force with their accessible sound and rebellious creativity, another four young men from Lubbock, Texas were busy laying down the foundation for what would become the rock and roll revolution. Niki Sullivan, Jerry Allison, Joe B. Maudlin, and Charles Holley were studio musicians merely dabbling in the only type of true indulgence teenagers had at that time. Blues and rockabilly, country and folk-- already established genres in their own right-- would be used as raw clay for the four boys, who would craft a concoction that would revolutionize the adolescent's very place in society.

But before then, a landmark invention would have to hit shelves in order to get their unique blend to the masses.

With the end of World War II came the advent of the personal radio, the forefather of the Walkman, Discman, Minidisc Player, the iPod, and now the smartphone and streaming services. These small, compact radios were a far cry away from the larger beasts installed in parlors and dens across the world. Which program to listen to on which evening was no longer decided upon by democracy; rather, the sole owner and operator had control over what he or she filled her ears with. This practice had only ever been seen before with the mass production of books. In a world where America had been the heroes in Europe (and the ogres in Asia), life for the average teenager meant being bombarded with omnipresent, brightly painted advertisements, new technology, the promises of travel with family-sized camper vans, the sweet tastes of new candies and ice cream from hamburger joints, and all of it still very much constricted by the need to be "one of us." Regardless, it was the first time in American history that the standard, family-centric paradigm was broken-- the average teenager no longer needed to "share," so to speak.

The personal radio, merely an empty vessel, would soon work its way into the hands of every child and teenager and became a revolution, but it needed the content to propel it forward. And rock and roll, blues, country, and danceable R&B became the software needed to break the mold. The days of jazz pop were slowly being eclipsed, its subversive counter culture once perceived as dangerous was more common place than ever before. The hot, new thing by the middle of the 1950s became records with an electric edge to them. Although tame by today's standards, the melodies and guitar riffs (often adapted and retooled from blues and country-folk origins),present on these recordings were integral to music evolution and still hold their own today.

The combination of Sullivan, Allison, Maudlin, and Holley proved to be reactive, and lucrative. Charles Holley, a charismatic front man with boy-next-door looks, was quick to show his licks from the word go. The boys formed as The Crickets, following the natural dissolution of another band, The Three Tones, and released The Chirping Crickets in 1957, a mixture of original material and blues/R&B covers featuring tight musicianship and impressive performance. 1958's almost immediate follow-up would be the result of a slick marketing ploy, catapulting the front man into the realm of supreme celebrity. The record would bear his now-iconic stage name: Buddy Holly.

Albums were an entirely different beast in the 1950s in comparison to today, and thus these two projects cannot be analyzed separately. Although thematic projects had been ushered into the mainstream music canon by Frank Sinatra, who is often credited with creating the earliest examples of concept albums, rock and roll was a newborn baby rapidly stumbling towards the age of growing pains. As such, Buddy Holly is not an album that was assembled with any great attention to detail. In reality, it is the second slice of the Crickets pie, released under Holly's name in order to capitalize on the band's signature sound and Holly's ever-growing popularity. Also, it was a clever way around contractual obligations by signing the band as two separate acts. The Chirping Crickets and Buddy Holly are two sides of the very same coin, the former a slightly more distant affair in comparison to the latter's more targeted presentation. Whereas The Chirping Crickets is far more general in its approach, the songs on Buddy Holly seem to be directing themselves at a teenage audience while simultaneously marketing the man for whom the record is named.

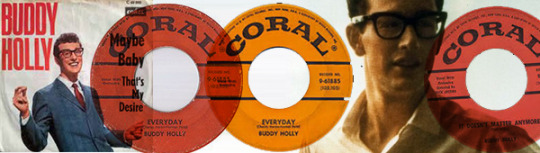

The two albums are neck and neck in terms of their quality, which stand out as arguably the best survived recordings of the whole of the 1950s. The range of fidelity on these records is astounding for the time period, with raw experimentation placed right at the forefront. Although the songs seem to draw their inspirations from a myriad of sources (from classical to lullaby to rhythm and blues), they are defined by the band's willingness to push forth into unknown territory. This is perhaps best evinced by the simplistic and sweet "Everyday," which perfectly encapsulates Holly's charisma and ability to adapt his voice to particular song styles. This evergreen is defined by the rather interesting combination of certain elements: acoustic and bass guitars, a typewriter, Holly's voice, and the gentle slapping of hands on Jerry Allison's knees. Its lack of decoration is strong evidence that less is, in many cases, more. It is also at stark contrast to the up-tempo rendition of "Ready Teddy," on which Buddy snarls with the gusto and experienced snap of a man thirty years his senior.

Despite not being the most artistic of albums, Buddy Holly is a non-stop disc of action, collecting within its short half-hour run time some of Holly and The Crickets' most important material. The classic (albeit rather overrated musically) "Peggy Sue" defines golden oldies in today's society, and the definitive reading of Sonny West's "Rave On" is a compact rock bullet to the ears. But elsewhere on this album, the deeper cuts ruminate and delight with their slick production and perfectly crafted melodies. From the jazzy, bass and piano--driven "Look at Me" to the rather sensual "Words of Love," the material present here is nothing if not far more advanced than the average pop songs on radio of the day. Whereas much of the standard fair was uncompromisingly pop or uncompromisingly rock, The Crickets managed to marry the genres, creating the blueprint for those who came after them.

The influence from black musicians of the era is full and complete on both The Chirping Crickets and Buddy Holly, which (as opposed to later-era acts like The Beach Boys and at times The Beatles) do not rob-- they contribute to the sound of the day. These four men were deep in the trenches, their youthful energy spilling over across two marvelous pieces of wax. Unfortunately, both of these records are meager when taken on the whole. Due to the nature of the recording industry at that time, much of Holly's best work (both with and without The Crickets) is not present on these two canon albums. Neither houses the spectacularly sexy "Well, All Right," the signature "That'll Be the Day," or "Blue Days, Black Nights," that last of which John Fogerty would later lift for his Blue Moon Swamp album in 1997.

There is a wealth of fantastic material to discover when searching through demos and one-off singles, in addition to Decca Records's That'll Be the Day, the unofficial third LP in Holly's canon, released only in response to The Crickets' later success on Coral and Brunswick. There's the downright sassy, almost baroque-pop "It Doesn't Marry Anymore," the near tropical stylings of "Heartbeat," and the bittersweet sequel "Peggy Sue Got Married" tucked in between all the flash and sizzle of Holly's biggest hits. They are also important clues for where Holly would have taken his musical adeptness into the 1960s, had he lived to help define them. His final recordings, unfortunately dubbed after his death, serve as our last glimpses into what the future could have been. At times, they are difficult to listen to.

Many of Holly's hits would be defined by the long shadow cast by his untimely death during the Winter Dance Party Tour in 1959, with "True Love Ways," an unreleased ballad from 1958 written for Holly's wife, perhaps the most heart-breaking of them all: "Sometimes we'll sigh / Sometimes we'll cry / And we'll know why just you and I know true love ways." These posthumous hits, along with some of his most experimental and/or forgotten material, would be collected and released on various compilations, the best of which being Decca Records's comprehensive triple-disc set The Very Best of Buddy Holly & The Crickets and the rare but complete Not Fade Away.

Today, Holly is regarded as one of the great grand-fathers of modern rock and roll, and nobody would be wrong in this declaration. However, it is important to note the important songwriting contributions from Jerry Allison and record producer Norman Petty. Between the three of them, they are responsible for the band's most iconic and important works. With Holly's tragic and untimely death (now coined "The Day the Music Died") we, as listeners, lost the original trajectory for pop music in forms we can only imagine. Would there be a The Beatles? A Duran Duran? A Madonna? A Janet Jackson? A Radiohead? Would disco have risen to power in the 1970s, and would synthesizers had taken the 1980s by storm? We cannot say, but one thing is for sure-- Buddy Holly and his bandmates had a lot more to offer the world that we could ever fathom. Although his career began and ended during the most embryonic phase of rock and roll’s fairly short existence, The Crickets ushered the genre towards excellence and informed every act who came after them.

Click here to buy material from Buddy Holly and The Crickets.

#buddy holly#buddyholly#music#music retrospective#thecrickets#the crickets#rockandroll#old hollywood#retro#vintage#1950s#the chirping crickets#jerry allison#charles holley#niki sullivan#joe b maudlin#waxontape#feature

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crybaby: Lil Peep and the Abject Sublime

Lil Peep was a rapper who came up in the Soundcloud rap scene of the late 2000s and after his death of an accidental fentanyl overdose would achieve chart success with posthumous singles like “Falling Down (feat. XXXTENTACION)” and his second full-length album Come Over When You’re Sober, Part 2 (Billboard, 2018). Though he was one of the most popular rappers to come out of the Soundcloud scene and went on to influence a revival of emo music in the trap scene, he elicited extreme positive and negative reactions, often within the same person. In an article for Vice, “Is Lil Peep’s Music Brilliant or Stupid as Shit?” Drew Millard repeatedly makes reference to the “stupidness” of Peep’s songs, which according to him “oscillate between asinine and laughable,” but also seems genuinely fascinated with him: “I’m not sure whether it’s out of enjoyment, morbid fascination, or a genuine concern for the guy’s well-being, but I can’t stop listening to him” (Millard, 2016). Lil Peep’s music touched on a variety of dark topics like drug addiction, depression, and suicide, and featured instrumentals that melded trap-style beats with music that recalled and sometimes directly sampled emo songs from the 2000s by artists like Underoath, Avenged Sevenfold, and Brand New, an amalgamation of sounds that Millard deemed “gimmicky” and as “scream[ing] ‘bad taste’” (Millard, 2016). Antony Fantano had a more unambiguously negative view of him: “He’s trying to convince you of how depressed he is...but yet his lyrics are so substanceless [and] so meaningless and so vapid, it’s like he’s depressed for the fashion of it...The way he frames [his music] it’s like he’s creating this sexy, glossy, moody fantasy, not the literal mental hell that some people have to struggle with every day” (theneedledrop, 2017). In this post, I will attempt to explain the appeal of Peep’s music through a series of comparisons to the “abject sublime” appeal of country music that Aaron A. Fox describes in his essay “White Trash Alchemies of the Abject Sublime: Country as ‘Bad Music’” (Derno, 2004).

In his essay, Fox said of country music that “the real star performer is the speaking object - the talking jukebox, the house full of furniture but emptied of love, the bitter goodbye heard on an answering machine or read on a Post-It Note stuck on the bathroom mirror, the bottle or glass that ruthlessly seduces the drunken fool, the picture of a lost love on the wall that continues to accuse across the years” (Derno, 2004). There are uncanny equivalents in the music of Lil Peep, but transplanted into a modern context, with lyrics about heartbreaking text messages, cocaine, regrettable casual sex, and self-harm. Fox said of country music, while comparing it to cigarettes: “It is consumed in a fit of self-assertion mixed with self-loathing, with a passion for pain as a feeling one can at least inflict sometimes on oneself” (Derno, 2004). Lil Peep, like the abject country singer, is constantly (and knowingly) the victim of his own actions, but the tone of it is almost braggadocios at times, mirroring the “self-assertion mixed with self-loathing” that Fox attributes to country music and cigarettes. “Country music,” Fox says, “affects the stance that it is trashy music for trashy people, with a knowing wink,” and presents the following lyrics by “hard country” artist Dale Watson’s song “I Hate These Songs”: “Note by Note/Line by line/It cuts to the bone/Man, I hate these songs.” He points out that these lyrics are all references to other country songs and that “such narratively embedded intertextuality is a canonical trope in hard country music” (Derno, 2004). Lil Peep’s music functions quite similarly at times, but rather than referencing music that he despises, he samples music that according to Millard, “literally everyone [else] hates” (Millard, 2016). He samples songs by bands like Underoath, Avenged Sevenfold, and Owl City in extremely unsubtle ways, bands that were never particularly critically beloved (and importantly, marketed mostly to teenagers), and now are broadly considered to be relics of a bygone era (perhaps even “trashy”). A particularly interesting example is “Yesterday,” a song that prominently features a sample of the Oasis song “Wonderwall,” and features the lyrics “Today is gonna be the day that I’m gonna go back to you/I know I did a little blow and I never wrote back to you” sung in the same melody as the verse of “Wonderwall” (Lil Peep, 2016). “Wonderwall,” while undeniably a popular and beloved song, isn’t a sample he’s trying to impress music critics with, but there is an undeniable kind of bravado in his use of it. Conversely, the narrator in “I Hate These Songs,” Fox says, “lovingly demonstrates a deep familiarity and passion for the songs he professes to despise, as he wallows in his own drunken misery” (Derno, 2004). While it is unclear to what extent Lil Peep’s referencing of these songs was ironic, or if it was at all, Millard points it takes “a certain bravery” to use music like this as the central sample of a song in today’s musical world (Millard, 2016).

Lil Peep’s music could be shocking in its ugliness, and while some people read this as honestly and vulnerability and others read this as potentially problematic posturing, the fact remains that for better or worse, he made a huge impact on the current trap landscape. This could be simply chalked up to the fact that, like the music Peep is inspired by, it is mostly marketed to teenagers and explicitly affects a very teenage demeanor, but I believe there is something deeper at work. Fox describes the futility of analyzing country music’s “musical badness” by explaining that “badness,” at least in the case of country music, is “determined by social relations structured in hegemonic dominance and resistance, ease and abjection.” In other words, country music fans often love country because of its perceived “badness” or “trashiness” by people in better social and economic conditions. To the working-class bars of Texas, Fox claims, “country music becomes [their] music, experienced not as a pleasurable diversion of a solipsistic exercise in the judgment of aesthetic worth, but as a brilliant way of re-valuing trash, of making the ‘bad’ song, bad feelings, and the bad...subject not only good, but sublimely good” (Derno, 2004). I believe Lil Peep’s music functions similarly, although perhaps more on an emotional level than an economic one. He knew how to affect abjectness and depression in a way that, although it didn’t always seem genuine, and at times his tone could come off as laughably inappropriate, was at least enough to make (sincerely or not) posturing as a depressed person seem fun enough to at least temporarily alleviate any real problems someone could be facing, mirroring the “abject sublime” appeal of smoking and country music that Fox describes (Derno, 2004). Although acting out depression may be seen as unlikable or unhealthy behavior to a more well-adjusted person, it can provide a strange, temporary, and perhaps shameful pleasure to the person doing it, and Lil Peep built a career on this impulse. Whether you perceive him as genuine, musically gifted, or tasteful all become somewhat irrelevant in the face of this realization. Fox concludes that, in the case of country, and I believe this could just as easily be applied to Lil Peep, “discriminating judgements of musical badness and goodness miss the rhetorical point of the music itself, and the cultural essence of its practice. It’s all good because it’s bad” (Derno, 2004).

References: