#ob ugrics

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

What's your favorite substrates in languages?

Oh I dunno, it's not the sort of a thing you usually have favorites in. There's a couple very different ways to even read this. Favorite substrate language? Favorite language-that-has-a-substrate? Favorite corpus of substrate vocabulary…?

I will shout out though one favorite Nonsense Substrate Theory: Ob-Ugric Substrate in Northern Sweden, posited on the basis of just a handful of placenames in the 1860s by Finnish para-academic linguist Daniel Europaeus (also e.g. an early proponent of Indo-Uralic, somehow on the basis of comparison of numerals, and the Out-of-Africa theory).

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ob-Ugric armies mainly consisted of 2 types of soldiers: professional ones called ljaks and militia

0 notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

Bulgarisms in Khanty

This article deals with words derived from Bulgar Turkic in the Khanty language. Khanty is an Ob-Ugric language alongside Mansi, part of the larger Uralic language family. Bulgar Turkic left Chuvash as its only living descendant. These entries are from the article Булгаризмы в хантыйском языке (с дискуссионными комментариями А. Рона-Таша).

The words were borrowed into PXa = Proto Khanty

Legend:

PXa = Proto-Khanty

Ch. = Chuvash

Tat. = Tatar (North Kypchak Turkic)

Bsh. = Bashkir (North Kypchak Turkic)

PT = Proto-Turkic

*pætər-ŋææj

whirlpool (J pæ̆tərŋi) (with suffix -ŋææj, compare *küɲŋææj rainbow, Mansi *künɣəl, > V køɲŋi, J kɵnŋi, Dn kŏšŋɐj); < Ch. пĕтĕр- pĕdĕr- twist, roll up (> Mari pətəräš, pütɨraš), < PT büt-ir- braid, büt-iš- interweave > Turkish bitiş-mek, Tat. бөтер- bøter-, Bsk. бөтөргөс bøtørgøs detail of a loom

*jaaɣ

people (V, Vj. jaɣ, Trj, J jɒɣ, Kaz. jɔx > Mansi jɔɔxŋ) < Ch. йӑх jăx race, tribe, kin (> Mari jɨx, jɨxsɨr "infertile", with suffix -sɨr “without”) < OT uq~oq; Mongol ug "root, base"

*kæɲ ~ kiiɲ

disease (V, Vj, Vart, Sur, Mj, Trj, J ki̯ń; Š, Kaz, Sy χĭń; Kaz χĭń; > Mansi χiń) < Tat. кыен qɨjen, Bsh. ҡыйын qɨjɨn difficult, Ch. хĕн xĕn torture (> Mgy. kín "torture, pain") < PT *Kɨɨjn. The two variants seen in Khanty could be from separate borrowings from Tatar and Chuvash.

*pæć ~ piić

thigh (VT pitˈ; Vj pitˈ; I petˈ; Kaz, Sy peś), Mansi (LM peeś, P peś, K piś ~ piš, T piś ~ pīš) < POb.Ug. *piić thigh < Ch. пĕҫĕ pĕʑĕ thigh, hip < PT *buut. The Chuvash form comes from *buut + 3rd person possessive suffix –(s)ɨ > *buut-ɨ where tɨ > čɨ

*kooj-/ køøj-/ kaj-

remnant of shaved wood (Kaz (St) χǫjəŋ (χǫjŋɛm), Sy χujəŋ), < Ch. хӑйӑ xăjă splinter < PT *Kɨj- cut into small pieces, shred, mince > Turkish kıymak "mince, shred"

*ćuɭći ~ ćɨɭći

mouse (Kaz (St)śŏḷśi-păḷśi Kaz śŭʌ́śi, VT tˈuɭmi̮, Vj, VK tˈulˈmi̮, Likr tˈi̮zˈmi̮, Mj, Trj tˈi̮ʌ́əm little sharp-faced mouse), Mansi n. śolˈsi ~ śolśi ~ śōlˈśi ~ śōlˈiś [śōlˈśi]; LM śōlˈiś ~ śōliś ~ šolˈeś ~ śolˈes ~ śōlˈeš; LU šolˈš; P śolˈiś ~ śålˈiś; K sōliś ~ sōlˈeś ~ sōlˈiś ~ sōliś; T śalˈś ~ śalˈiś ~ šalˈš, < Ch. шӑши ʃăʒi/ šăži < PT. *sïčgan > Old Uyghur syčγˈn sïčɣan, Tatar тычкан tɨčkan, Kazakh тышқан tışqan, Southern Altai чычкан čɨčkan, Shor шышқан šïšqan, Uzbek sichqon, Uyghur چاشقان chashqan, Turkish sıçan.

Medial -ɭ- in Khanty may come from a dialectal form. Dialectal Chuvash šărži.

saart

pike fish (V, Vj, Vart, Likr, Mj sart (V surtəm); Trj, J sårt (surtəm); I sort; Kaz sɔrt; Sy sɔr); Mansi sort ~ sɒrt < POb.Ug. *saart; < Bsh. суртан surtan, Ch. ҫӑрт(т)ан ɕărdan ~ ɕărttan < PT *čortan > Ya. сордоҥ sordong, Tat. чуртан čurtan

*kaaŋrV ~ kuuŋrV

insect (Kaz (KT, St) χɔŋʽri; I tˈoŋχər); < Ch. хӑмӑр xămăr "drone" (male bee), хорт-хӑмӑр xort-xămăr "insect" (general) < PT *Koŋuŕ beetle > Tat. qoŋɣɨz, Ya. xomurduos, Khakas Xoos

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Endangered Language Challenge Day 1 - Mansi

Also known as Vogul or Maansi, it belongs to the Finno-Ugric branch of the Uralic language family. It is most closely related to Hungarian and Khanty, but other notable relatives include Finnish, Livonian, and Estonian. According to a 1989 census, about 3,100 people spoke the language in Russia.

Where and who?

The language is spoken along the Ob river and areas around in Russia by the Mansi people. They live in one of the autonomous regions, Tyumen.

Endangerment

Central Mansi is recorded as being threatened (6b). The Mansi people have an estimated population of 12,269 as of the 2010 census. They have a long history with the Russian Empire, being under more Soviet and Russian control than their Khanty counterparts, with whom they also have a lot of shared history with.

The Soviet government forced people to only speak Russian at home, solely teaching Russian in schools, and all media being in Russian, native languages such as Mansi became endangered.

There is evidence that the language has not lost its structural integrity due to the Russification of native tribes and former Soviet states.

Legality

The language is recognized as an official language of the autonomous state Tyumen. There is a push for teaching the language in schools within the region, but most education is done in Russian due to the large Russian population in the area. It is important to note, though, that Mansi is used in education.

Documentation? Resources?

There are grammars about Mansi, albeit few and far between. There are also teaching materials due to the push in Mansi education.

Tech resources

Eastern Mansi Grammar

Mansi Grammar

Source / Source / Source

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Siberian History (Part 4): Native Peoples

By the time Russia began their conquest of Siberia, there were already around 140 different native peoples living there. Pastoral nomads, with cattle and sheep herds, roamed the south-western steppes; forest nomads hunted and fished in the taiga; reindeer nomads drove their great herds along fixed routes in the tundra.

Agriculture was practised in the Amur River Valley, but only on a basic level. In the extreme north-east, tribes hunted wild reindeer or whales, walruses and seals along the shores of the Bering Sea and Sea of Okhotsk.

Some of the tribes living in the steppes and forest regions were in the Iron Age, and had developed links with China and Central Asia. Those living in the tundra regions were in the Stone Age.

The Paleosiberian peoples were the descendants of Siberia's prehistoric inhabitants. They include:

In the north-east – the Chukchi, Yukaghir, Siberian Yupik (used to be called the Asiatic Eskimos) and Kamchadals. The Kamchadals covers all the peoples living on the Kamchatka Peninsula, including the Ainu, Alyutors (in the north, and also on the Chukchi Peninsula), Chuvans, Itelmens and Koryaks. Also living in the north-east were the Kereks, who during the 1900s were almost completely assimilated into the Chukchi.

On the lower Yenisei River – the Ket (used to be called the Yenisei Ostyaks).

On the northern part of the Kamchatka Peninsula – the Alutor.

In the lower Amur River Basin & the northern half of Sakhalin Island – the Nivkh.

On the southern half of Sakhalin Island & the Kuril Islands – the Ainu.

[The Yukaghir are one of the oldest peoples in North-East Asia, but they do not speak a Paleo-Siberian language.]

From the 200s AD onwards, Neosiberian tribes began to join the original inhabitants:

Finno-Ugric peoples – the Khanty (old name Ostyaks), Mansi (old name Voguls), and Samoyedic peoples (the name comes from “Samoyed”, an obsolete term for some indigenous Siberian peoples). The Samoyedic peoples were the Nenets, Enets, Nganasans and Yurats (Northern Samoyeds); and the Kamasins, Koibal, Mators and Selkups (Southern Samoyeds). The Yurats, Kamasins, Koibal and Mators now no longer exist.

Turkic peoples – including the Siberian Tatars, Yakuts, Chuvash, Dolgans and Tuvans.

Tungusic peoples (sometimes called the Manchu-Tungus) – including the Evenks (old name Tungus) and Evens (old name Lamuts). They are sometimes grouped together as “Evenic”. There were also the Nanai people (old name Goldi).

The Mongols – subgroups in Russia are the Buryats and Kalmyks. There were also the Daur people, who nowadays mostly live in north-eastern China.

The Khanty & Mansi were semi-nomadic, living in the forests and marshes of the Ob-Irtysh Basin. The Samoyedic peoples were reindeer herders, roaming the Yamal and Taymyr Peninsulas, as well as the tundra west of the Yenisei River.

The Yakuts lived in the Lena Valley. They had settlements along the headwaters of the Yana, Indigirka and Kolyma Rivers.

The Evenks lived in a region that stretched east from the Yenisei Valley to the Pacific Ocean. The Evens, cousins to the Evenk, lived on the shores of the Sea of Okhotsk. The Nanai people lived on the middle Amur Basin.

During the 1200s and 1300s, the Buryats established themselves in areas of steppeland around the southern end of Lake Baikal.

In the 1600s, some (or all) of the Daur people were living along the Shilka River, upper Amur River, Zeya River, and Bureya River. In 1640, the Qing Dynasty crushed the Evenk-Daur Federation, and the Amur Daurs came under their influence.

-------

Apart from the Siberian Tatars, who were Muslims, all the native Siberian peoples followed pagan religions.

The Buryats and Yakuts were descendants of Central Asian pastoral nomads, and were the most advanced of all the Siberian peoples. They kept cattle & horses, and had clan chiefs.

The reindeer-herding peoples had no (or little?) institutionalized hierarchy, congregating regularly as small family bands for councils and seasonal rituals, or to share meat from hunts. Those in the far nothern tundra had a hard life, following their great reindeer herds from place to place, pausing only long enough for the reindeer to paw up the snow for moss around their encampment.

The Koryaks of northern Kamchatka were probably the most isolated. They roamed over great moss-covered steppes, among extinct volcano peaks 1.2km above sea level, sometimes enveloped in drifting clouds, swept by frequent rainstorms and snowstorms.

#book: east of the sun#history#native siberians#russia#siberia#russian far east#russian far north#chukchi people#yukaghir people#yupik#siberian yupik#kamchadals#ainu#alyutors#chuvans#itelmens#koryaks#kereks#ket people#alutor people#nivkh people#khanty people#mansi people#samoyedic peoples#tatars#siberian tatars#yakuts people#chuvash people#dolgans#tuvans

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1. Costume of the South Khanty people, belong to Ugric tribes, Siberia.

2. Khanty family at River Ob in the village of Tegi

3. Khanty girls gathering berries

4. South Khanty embroidery

5. Khanty beaded necklace

The Khanty (in older literature: Ostyaks) are an indigenous people calling themselves Khanti, Khande, Kantek (Khanty), living in Khanty–Mansi Autonomous Okrug, a region historically known as "Yugra" in Russia, together with the Mansi. In the autonomous okrug, the Khanty and Mansi languages are given co-official status with Russian. The Khanty language is related to Finnish and Hungarian.

333 notes

·

View notes

Text

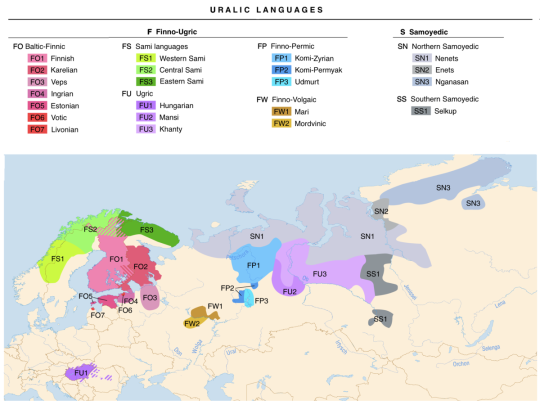

Genetic Relationships Between Uralic Languages

This map gives a good basic idea of some groupings’ historical spread, but it’s overly simplified

Today there are about approximately 25 million native speakers of various Uralic languages. There are (approx.) 38 languages which belong to this Eurasian family. 35 Uralic languages are endangered and many of these are critically endangered and some are even moribund.

The following groupings are the currently most accepted one by linguists:

URALIC:

This term is used to refer to all the languages in the family. The possible Uralic urheimat (=homeland) was between the Volga and the Kama rivers (modern day Russia)

Uralic has two main branches, Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic.

Samoyedic:

Samoyedic languages are spoken by around 25 000 people, all of these languages are severely endangered. Samoyedic languages are spoken in the northern most areas of Eurasia, on both sides of the Ural mountain.

More genetical grouping:

Nganasan † Mator Core Samoyedic: - Enets-Nenets: - Enets - †Yurats - Nenets (Tundra and Forest Nenets) - Kamas-Selkup: - †Kamassian - Selkup (Taz, Tym and Ket Selkup)

The other, bigger branch is called Finno-Ugric, Finno-Ugric has several branches. Finno-Ugric:

Permic:

The Permic languages are spoken by around 950 000 people, mainly in Udmurtia and in the Komi Republic (both of these terrotories are part of the Russian Federation)

Udmurt Komi (Komi-Zyryan, Komi-Permyak, Komi-Yodzyak)

Mari:

This branch of the Finno-Ugric family only contains one language Mari (Meadow Mari and Hill Mari). Mari is spoken by around 450 000 people in the Mari El Republic (Russian Federation)

Mordvinic:

The two Mordvinic languages are closely related, but not mutually intelligible. Both are spoken in the Russian republic of Mordovia. The Mordvinic languages are spoken by around 432 000 people.

Erzya

Moksha

Finnic languages:

Finnic languages are spoken around the area of the Eastern Baltic Sea, and in the areas surrounding the lakes Ladoga and Onega. Finnic languages have around 6,5 million native speakers. Many Finnic languages are critically endangered.

Northern Finnic:

- Finnish (Meänkieli and the Finland-Finnish dialects) - Ingrian - Karelian (Livvi and Karelian proper) - Ludic Karelian - Veps

Southern Finnic:

- (North) Estonian

- South Estonian (Seto and Voro)

- Livonian (†)

- Votic

Samic languages:

The Samic languages are spoken in the northern parts of Sweden, Norway and Finland and in the most northwestern parts of Russia. All Samic languages are endangered. The languages in total are spoken by about 30 000 people.

Western Samic languages: - Southwestern: - Ume Sami - Southern Sami - Northwestern: - Pite Sami - Lule Sami - Northern Sami

Eastern Samic languages: - Mainland: - Kemi Sami † - Kainuu Sami † - Akkala Sami † - Skolt Sami - Inari Sami - Peninsular: - Ter Sami ( † ) - Kildin Sami

All the branches of Finno-Ugric mentioned so far are sometimes clustered together as Finno-Permic (thus making Finno-Ugric) , but nowdays most linguists say that this grouping is outdated.

Ugric:

The Ugric languages are spoken by around 14 million people, in Northwestern Siberia and in the Carpathian Basin. Only around 10 000 people speak Ob-Ugric languages, the rest are speakers of Hungarian.

Hungarian (Hungarian and Csángó)

Ob-Ugric:

- Khanty (Eastern, Northern and Southern) - Mansi (Konda and Sosva dialects)

Long post, for small languages -lidi

351 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hungarian Translation Service

Hungarian Translation Service, Hungarian Interpreters and Transcription for legal, medical, corporate and private matters in UK

“Language Interpreters” are a team of highly professional translation service providers in UK offering Hungarian translation services, Hungarian interpreters & Transcription. We also provide language service for over 100 other Languages. We cater to legal, medical, public and private sectors to offer our service at reasonable and competitive rates.

Hungarian Interpreters

Our team of Hungarian interpreters who are dedicated, qualified and skilled with a minimum of one or more formal interpreting and translation qualifications that permits them to provide services at various sectors such as Courts, Tribunals, Offices of Law Firms, GP Practices, Councils, Hospitals, Prisons etc. Our freelance interpreters are highly in demand as they cover several dialects for our three services in a short time period.

Our Hungarian Interpreters services:

Telephone interpretations

Video Translations

Onsite Interpretation

Hungarian translation services

Our freelance Hungarian translation services providers are also an experts in interpreting papers for a wide range of sectors. They meet all of the requirements of the Legal Aid Agency for assistance. For all formal purposes, our Hungarian interpreters are highly qualified and certified.

Our Hungarian translation services:

Legal translations- Legal document translation, witness statements translation, social service-related matters, mental health assessments translation, medical reports etc. for the private and public sector, businesses and all other legal firms.

Personal translations- We provide personal translations related to documents such as passport, birth, education, demise etc. and also professional certificates and more, for immigration, asylum, childcare, family, crime, housing and other matter

Technical translations- Technical translation related to reports, contracts, leaflets, books, etc.

Hungarian transcription services

We also provide Hungarian transcription services for videos, audios, CDs, YouTube links and more.

Hungarian language, origin and dialects spoken over the world.

Origin and History

Along with the Ob-Ugric languages, Mansi and Khanty, spoken in western Siberia, Hungarian belongs to the Ugric branch of Finno-Ugric. Khanty and Mansi, Russia's minority languages, spoken 2,000 miles away, east of the Ural Mountains in northwestern Siberia, are her nearest cousins. A part of the Uralic language family is Hungarian (Magyar).

In terms of the number of speakers and the only one spoken in Central Europe, it is the largest of the Uralic languages. Hungarian has been isolated from Khanty and Mansi for about 2,500-3,000 years, it is estimated. Standard Hungarian is based on the variety which is spoken in Budapest's capital. Hungarian has a variety of urban and rural dialects, even though the use of the common dialect is applied.

Dialects

The Hungarian dialects are Central Transdanubian, North-eastern Hungarian, Palóc, Southern Great Plains, Southern Transdanubian, Tisza-Körös, Western Transdanubian, Oberwart spoken in Austria, Csángó spoken in Romania. The Oberwart dialect spoken in Austria and the Csángó dialect spoken in Romania are difficult to understand by speakers of standard Hungarian.

Countries spoken

The language of Hungary is entirely different from the dialects spoken by its neighbours, who typically speak Indo-European languages. Hungarian, in truth, comes from the Ural region of Asia and belongs to the Finno-Ugric language community, meaning that Finnish and Estonian are probably its closest relatives.

Hungarian, Hungarian Magyar, a member of the Finno-Ugric group of the Uralic language family, spoken mostly in Hungary but also in Slovakia, Romania and Yugoslavia, as well as in communities scattered across the world.

Contact Language Interpreters for Hungarian to English Translators, interpreters and Transcriptionist

If you are in search for the best Hungarian translation services, interpreters and Transcriptionist service in UK then you are at the right place.

0 notes

Note

What do you make of the fact that PU roots never (?) have C₁VC₁? IMO the strangest part is that not even /compounds/ have them, which makes me wonder how PU morphophonology handled those.

This is quite sensible: it’s a part of the general principle of Similar Place Avoidance. E.g. PIE verb roots don’t really do *C₁VC₁… either, aside from a single example √ses- ‘to sleep’ (also *h₁eh₁s- ‘to sit’, but with the usual problem that root-initial *h₁- is not reflected by anything and only added for root-structral reasons). Semitic also does the same roughly. In PU this is expected also already from the fact that typical root structure is biased towards *KVRV (where K = obstruents and glides, R = liquids and nasals) while *TVTV or *RVRV are rarer.

In some less secure PU roots there still are potential *C₁VC₁V examples also, so this doesn’t even seem to have been any kind of an absolute rule, just a statistical tendency. Basing on UEW see e.g. Finnic+Permic *säsäw ‘(horn) marrow’, Finnic+Komi+Khanty *leləw ‘hard wood’, Permic+Ob-Ugric *čëčə ‘duck sp.’, Samic+Finnic+Samoyedic *kokə- ‘to see/check’. And if you’re up for counting *C₁VC₁C₂V, then we will have all sorts of clear examples like #kakta ‘2’, *soskə- ‘to chew’, *totkə ‘tench’, *tütkə- ‘to spread’.

For further areal context I briefly checked Turkic though, and interestingly they seem to be much less concerned about this. Already just for *k-k: *kak ‘dry’, *kak- ‘to hit’, *kakï- ‘to be angry’, *kēk ‘anger’, *kek(e) ‘curved object’, *kik- ‘to rub together’, *kok ‘dust’, *kok- (1) ‘to decrease’, *kok- (2) ‘to reek’, *kök (1) ‘root’, *kök (2) ‘nail, peg’, *kök (3) ‘big, thick’, *kök (4) ‘seam’, *kȫk ‘blue/green’. Several cases also with *č-č, *j-j, *s-s, *t-t.

I don’t know what you mean with compounds, there are no compounds reconstructed for Proto-Uralic that I know of (if you have a reference I’d love to hear of it!).

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is the capital of the ancient principality of Emder, lost in the Ob taiga of the Khanty-Mansiysk district, 19 years ago known exclusively for the heroic epic of those places.

Residents of the Urals, ancient Ugra - who are they? They are usually considered hantas and mansyas, but is this true?

As a rule, answering this question, most inhabitants begin to talk about the inhabitants of the taiga - hunters and fishermen.

Someone will remember that they belong to the Finno-Ugric peoples and are distant relatives of the Hungarians.

But few people imagine that in the Middle Ages (IX-XVI centuries) in terms of their level of development, these taiga inhabitants differed little from the inhabitants of Kievan Rus. Including visually.

They controlled most of the present Urals and Western Siberia and the Perm Territory, including Sverdlovsk, part of the Chelyabinsk and Kurgan regions.

All this territory was divided between a dozen principalities, in which, as in any medieval kingdom, there were their city-fortress, guarding agglomerations of villages, warriors, militia, small and large princes.

And yet – the medieval inhabitants of this area were not just hunters and fishermen.

They knew metal and cattle. It is no accident that one of the main revered animals among the descendants of local residents is still considered a horse.

Their trade links, mostly fur, extended to Veliky Novgorod in the west and Iran in the south.

In the XV-XVI centuries, they repeatedly and sometimes quite successfully attacked the eastern possessions of the Russians - the Perm lands, ruled by the Stroganovs.

However, with the arrival of Mongoloids from Central Asia, including the army of Kuchum from Bukhara, and the subsequent campaign of Yermak, the culture of the peoples of the Urals began to regress.

It is important that by the end of the XIX – beginning of the XX century, only legends remained about the former glory of the Ural tribes.

One of them - "Bulin about the heroes of the city of Emder" - at the end of the 19th century recorded the famous researcher of the Tyumen north Seraphim Patkanov.

It tells about the campaign of local heroes from the former city of Emder - the capital of the principality of the same name on Konda.

Now it is a river in KhMAO, and in the Middle Ages it was also the name of another local principality.

In general, from the legends recorded by Patkanov, it follows that the Ural heroes lived a normal life of medieval feudal lords - they built powerful fortresses, their dwellings were full of gold, silver and silk, they arranged feasts, lists, etc.

However, to find exactly where all this happened, it was possible only after almost 100 years.

Actually, because of this, Emder was dubbed the "Siberian Troy", comparing with the circumstances of the "discovery in 1871 by Heinrich Schliemann of the ancient city, known until then only by the "Iliad" of Homer.

In 1994, Ekaterinburg archaeologists Sergei Koksharov and Alexei Zykov, based on the stories of local residents, found a settlement 70 kilometers south of Nyagan on the high cape of the Yendyr River, which they called with reference to the geography of Yendyrskoye-I.

Judging by the size, serious fortification (it was surrounded by several rows of moats and ramparts), collected artifacts, it was the lost capital of the Principality of Emder.

Almost two decades of research of the settlement and the surrounding area only confirmed this assumption.

It turned out that the surrounding area has been popular with people since the Bronze Age (2 thousand years BC).

In total, nine settlements and fortified settlements were found here, as well as several burial grounds (another archaeological term denoting ancient cemeteries).

Two of them belong directly to the medieval Emder, that is, residents of the capital city found their last refuge here.

Emder itself, by the standards of that era, is a serious military-political center, structurally included (through the payment of tribute) in the larger Kodskoy principality.

This is supported by the collections of things collected by archaeologists, including weapons and jewelry made of silver and bronze.

What the medieval city looked like is best illustrated by a mock-up reconstruction exhibited in the Nyagan Museum and Cultural Center.

Everything is made of wood: two rows of log fortress walls with gate towers, in the center of the princely chambers, housing for selected warriors, forge.

During its 400-year existence (XII-XVI centuries), the city was rebuilt nine times.

Most often due to fires, and in some cases it was clearly burned during hostilities.

Despite years of fieldwork, exploration of the area is far from complete.

In particular, this year a joint expedition of Yekaterinburg archaeologists and a detachment of Nyagan schoolchildren continued to study one of the burial grounds.

The main question now is how to popularize the material obtained by scientists.

A few years ago, a project appeared to create an open-air historical and archaeological museum near Nyagan, on the territory of which it was planned to restore the medieval fortress city of Emder in full size.

Such museums in the “Tyumen nesting doll” are not uncommon.

In Khanty-Mansiysk operates "TorumMaa" (Land of NumTorum - the supreme deity in the Ugorsk pantheon).

In Yugorsk - "Suevat-paul" (village of northern winds). But everywhere there is only a traditional way of life of the peoples of the Urals - taiga hunters and fishermen, and nowhere is there a hint of their much richer past.

Either because of the lack of funds, or because of fear to show that the peoples of the Urals were not just Khanty and Mansi, but white people, with a developed civilization, perhaps because of this, so far, the project of reconstruction of the capital of the Emder principality lies under the cloth.

Meanwhile, Emder at the moment continues to be, perhaps, one of the few qualitatively studied medieval fortresses in Russia.

Over the past two years, the condition of the monument and its surrounding area has seriously deteriorated. First, there was a powerful forest fire, then the remains of the fortress were almost destroyed by tractors and timber trucks that removed the burner.

The view of the cape towering tens of meters above the water cut and the powerful ramparts crowning it, which unexpectedly came to you from the taiga, made a strong impression. In 2013, this place, which turned out to be on the edge of a giant forest cutting, littered with fallen trunks and branches, is visually no longer so bright.

But only externally and only for those who do not know what exactly is hidden behind this logging.

Emder, Siberian Troy - waiting for its reconstruction !

Ekaterina Losetskaya

0 notes

Link

Newest suggestion from the "Transeurasian" rebranding of Altaicists. I've seen relatively little productive discussion of this so far. To start with it is surely probable that something spread with millet agriculture as detected in the archeological evidence, and this does seem to fit the rough degree of divergence between the suggested branches of Altaic. I'm less sure if this has anything at all to do with Mongolic or especially Turkic, whose homeland seems to be often located more by where people want it to be than where there is any actual evidence for it (and as always, agriculture can be transmitted also independently of language).

The clearest indicator of problems must be the absolutely waffling and slightly nonsensical take in their article's map 1b, with Proto-Turkic being placed as a big sausage from Beijing to north-central Kazakhstan:

Even their own Supplementary Data 4 fails to support any of this furthest eastern range in fact. This has been rather placed by slight terminological abuse where the lineage of Turkic immediately counts as "Proto-Turkic" as soon as it splits from Proto-Transeurasian:

Therefore, the Proto-Turkic homeland on the map in Fig. SI 4.10 can be considered as a dynamic entity, gradually expanding from Southeast to Northwest from the Middle Neolithic to the Early Iron Age.

But this makes the map and the argument rather misleading since it's not that range (3) is reconstructed by the evidence of the descendant ranges. Instead, apparently the descendant ranges have been tweaked to better fit the Proto-Transeurasian range they want to find. So should we trust any of them?

I am also not impressed at all by the alleged native layer of "agripastoral" vocabulary in Turkic. The section on agriculture in particular seems to be mostly made of look-alikes with meanings different from the other words (which do correspond better), e.g. 'field' is compared with 'island', 'sour' is compared with Turkic–Mongolic 'to filter' (both are steps in cheesemaking but I don't think that makes them cognate); or, in some cases, general action verbs with no especially agricultural meaning ('to soak', with four separate verbs with this meaning suggested altogether; 'to crush'). The only really solid-looking case is *tari- 'to cultivate', and this is however absent from Japanese and Korean.

It would not be hard to find some suggestive Uralic correspondences to many of these either, off the top of my head e.g.

– *muda 'field': cf. Uralic *muďa 'earth' – *saga- 'to ferment': cf. Ugric *čawa- id. – *pisi- 'to sprinkle': cf. west Uralic *piśa-, perhaps 'to drizzle' (Finnic pisara 'drop', Mordvinic piźe- 'to rain'); or Ob-Ugric *pëśəɣ 'to drop'

A section on domesticated animals is also amazingly weak, finding only three items where none is unambiguously domesticated and all classic livestock are absent:

– Japonic–Korean *ina/u 'dog' ~ Tungusic 'wolf' – Mongolic *toru 'young pig' ~ Turkic *tōru 'young ruminant' (~ North Tungusic torokī 'wild boar', probably ← Mongolic). – Khitan–Tungusic *uli 'pig'

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The curious case of Hungarian: Europe’s most complex language? | OxfordWords blog

The curious case of Hungarian: Europe’s most complex language?

Hungary might sit in Europe’s geographical heart, but its language bears little resemblance to its Indo-European neighbours. Originating from the Ugric subgroup from the Uralic group of languages, Hungarian, along with its far-flung distant cousins Finnish and Estonian, has little in common with other European languages. It’s an agglutinative language, in which complex words are made up of countless grammar prefixes and suffixes that serve very specific functions within each word, sometimes allowing a single word to translate into English (or related languages) as a relatively long sentence. Being such a lawless language for most Europeans, Hungarian is said to be one of the hardest languages to learn.

My history with Hungarian

Growing up with a Hungarian mother and an English father in the UK, people assume I grew up bilingual. But after about five minutes of conversation in Hungarian, the cracks begin to appear. A misused case or misplaced word will tarnish my deceptively well-pronounced Hungarian, prompting the surprised question: “Where are you from?”

I was a late talker, and a popular misconception held among child psychologists my parents took me to at the time caused them to blame my bilingual surroundings for the delay. Hence, before I even said my first words, we reverted to being a monolingual, English-speaking household. The concept of correlating bilingualism with language delay has since been widely disproven. But eventually, I finally said my first English words and I haven’t shut up since. Sadly, my Hungarian acquisition stopped until the age of eight.

My mother tried to communicate in Hungarian sometimes, only to be confronted with “Mummy, why do you speak to me funny and everyone else normally?” from a sassy toddler. I was stubborn, but my mother wouldn’t give up, so we moved to Budapest and she put me in a local school where no one spoke English.

I sat alone and listened to this strange, yet oddly familiar, language echoing around the classroom for three months without uttering a word. Hungarian, unlike French and even German, has virtually no words that someone with an English vocabulary can hook onto as a crutch.

Why is Hungarian so unusual?

Hungarian may use a Latin alphabet, adopted since the 13th century to replace the original runic script, but that’s where the similarity with other European languages ends. And even with its northern Finno-Ugric cousins Finnish and Estonian, the languages have little in common with each other. I can say that being a Hungarian speaker gave me little to no advantage when I travelled through rural Estonia earlier this year.

As Hungarian evolved away from what became the Baltic branch of the Finno-Ugric languages, it has infused itself with various linguistic influences that have left the language such a curiosity. Ugric languages can be found as far as Western Siberia, east of the Ural Mountains, where Mansi and Khanty are spoken and are perhaps Hungarian’s closest living relatives. But, with a geographical separation of 2000 miles, estimates place the linguistic distance of those Ob-Ugric languages from modern day Hungarian at about 2500-3000 years.

Making its way to Europe, Hungarian became a language moulded by its migration. Hungarian acquired many words with Iranian, Turkic, and Caucasian origin offering a linguistic breadcrumb trail towards its roots in the Urals. Later it also became influenced by its European neighbours, with words being picked up from languages from the Slavic, Latin, and Germanic families, and even its Turkish influences could be traced to the Ottoman occupation of the country which lasted for almost 200 years.

But while there may be the odd identifiable German or Slavic word, the language is still virtually indecipherable to its neighbours. Even though the language evolved over time, its grammar and phonology stays loyal to its Uralic origin. One of the greatest challenges for non-Hungarian speakers are its pronunciation, where you have three groups of vowels (totalling about 14 vowels) and groups of consonants clustered together, some of which make unique sounds, such as Ny (/ɲ/ – think the ñ in Spanish), Sz (/s/ – that’s a normal S to most of us), S (/ʃ/ – which sounds like Sh), Dzs (/dʒ/ – that takes on a J sound), or Gy (/ɟ/ – I have no idea how to explain this one to English speakers, but I can tell you the Hungarian surname Nagy is not pronounced “Naggy” as in your naggy relative).

This can prove to be a landmine when it comes to pronouncing certain words, where a carefully placed accent changes the meaning of the word, such as cheers, Egészségedre [ˈɛɡeːʃːeːɡɛdrɛ], which becomes a toast ‘to your whole posterior’, when missing an accent in the case of Egészsegedre [ˈɛɡeːʃːɛɡɛdrɛ].

A grammatical headache

Beyond that, Hungarian grammar offers learners an intellectual headache with its elaborate case system, where you have 18-35 cases depending on who you ask, that are used to express prepositional meaning. Tense, noun, adverb, adjective, person, number, and case are expressed through a complex directory of hundreds suffixes (along with prefixes), where an incorrectly used suffix will change the entire meaning of the word or sentence, for example the verb hív (call) changes to Jánossal hívathatnál egy taxit (you could have János call a taxi) in another sentence, where you have the stem, hív, followed by causative (+at), may (+hat), and conditional you (+nál).

Today, I feel lucky enough I still fell in the catchment period of learning the language. I was still young enough to learn a language like a sponge while being immersed in a Hungarian-speaking school, and after three months of silence, I spoke the language fluently. Returning to the UK for my studies put an end to my acquisition, and as a lazy teenager being bullied for having picked up a Bela-Lugosiesque accent, my Hungarian became a time capsule for the age I left, which was 11.

When I moved back to Budapest years later at 28, my Hungarian was rusty and stunted at the language abilities of a child in an adult’s body. Over the years, I grew up linguistically, but even so, I will still be far from a native speaker.

But when I look at the other English speakers living here, struggling to understand this difficult language, I can only be grateful that for me that I bypassed learning all the rules by picking up the language from my exposure to it as a child.

Hungarian is certainly a language that will offer an intellectual challenge to any daring language learner, so if you decide to learn this fascinating language as an adult then I wish you good luck on this linguistic Odyssey!

Source

https://blog.oxforddictionaries.com/2016/10/21/hungarian/

0 notes

Text

Indo-Uralic, so many ideas, so little time.

I have been dabbling into the comparison of the Indo-European and Uralic language families for some time. But now I am at the point where I feel that I have scratched the surface, and there is so much below it. It has been said that Indo-Uralic is a project that could take a dedicated linguist more than 30 years to work on. I'm starting to see that this is right. There are so many ideas to work out, but as an amateur I can't work full-time on this. So here are of some ideas that I’m working on now or plan to work on in the future.

Linking the ablaut in eastern Khanty to the PIE ablaut. Eastern Khanty has an ablaut system with the following paradigm:

alta ‘to extend’ ~ ultăm ‘I extended’ (perfect) ~ ïltï ‘extend!’ (imperative)

kat ‘house’ ~ kutăm ‘my house’ (possessed noun)

This is just one of the 7 possible ablaut patterns in eastern Khanty, which are: a- u- ï; ä- i- i; ɔ- u- u; ɔ̈- ü- ü; o- ă- o; ö- ě- ö and e- ě- e

I know there is very little reason in Uralic to reconstruct any ablaut based on this at the proto-Uralic level. And several attempts have been made to explain this phenomenon as an umlaut in Ob-Ugric by some unattested suffixes.

However, within an Indo-Uralic framework, it makes a lot of sense to link this to PIE ablaut and to reconstruct ablaut at the Indo-Uralic level. I have come up with the following scheme:

A-grade corresponds to PIE E-grade

I-grade (imperative) corresponds to PIE zero-grade

U-grade (perfect, possessed noun) corresponds to PIE O-grade

A zero-grade imperative has been attested in Ancient Greek:

ḗimi ‘I go’ ~ ithí ‘go!’ (2nd person singular)

phḗmi ‘I speak ~ phathí ‘speak!’ (2nd person singular)

Also, Ancient Greek does show an interesting parallel for the possessed nouns:

patḗr ‘father’ ~ eu-pátōr ‘having a good father’ ~ a-pátōr ‘not having a father, orphan’

phrḗn ‘mind’ ~ sṓ-phrōn ‘having a sound mind, sane’

The difficult part here is Proto-Uralic. If this is done right, it should be possible to find the correspondences between PIE ablaut grades and the PU vowels. So this is a key idea for me.

For example, the Eastern Khanty, a-ï-u pattern probably goes back to PU a-ï-o. The simplest idea here might be a vertical vowel system (a ~ PIE e; ë ~ PIE o; ï ~ PIE zero grade) with front/back; labialized with 'w'/unlabialized; short/long variants in PU. But if you know anything about the vowel correspondences in PU, you would know what a huge task it is to sort everything out.

An ofshoot of that little project is the idea that disharmonic stems like Finnish likoaa 'he washes' should be reconstructed as lïuka (~PIE *lewh₃) in Proto-Uralic.

The correspondence between PU plural -t and PIE plural -s. Also PU 2nd person -t and PIE 2nd person -s. I think this will require its own correspondence set if it is ever going to work as a correspondence. I don't think that Kortlandt's idea of Finnic-like *ti -> *si assibilation holds. My idea that this goes back to an Indo-Uralic **z (or maybe **ð, but that is already taken in Uralic). This PIU **z would correspond to *t, *s and *r in both PIE and PU but under different circumstances.

Potential cognates with this set include:

PIU **zïwxa 'pig' ~ PU *tika 'pig' ~ PIE suH 'pig'

PIU **näz 'nose' ~ PU *näri 'nose', nistä 'pant, blow' ~ PIE neh₂s 'nose’

PIU **maz- 'wet' ~ PU *mośkï(1) 'to wash', PUg *mar-/*mär- 'to dive' ~ PIE *mesg(1) 'to dip', *mori 'sea'.

PIU **z 2nd person ~ PU -t 2nd person marker, PSam -r-,-l- 2nd person marker ~ PIE -s- 2nd person marker, PIE th2- 2nd person marker

PIU **z plural ~ PU -t plural marker ~ PIE -s plural marker, ? PIE -r 3nd person plural marker

(1) These may also be linked to a PIE root *meh₂ 'wet'.

PIU consonant gradation (low prio) There are lots of roots in PIE where there are variants with different stop grades but similar meaning, e.g. *keh₂l ‘to call’, *gʰel ‘to shout, to yell’, *gels ‘to call, voice’ or *bʰer ‘to carry, to bear’, *per ‘to travel, to fare’. Could these be caused by a consonant gradation mechanism on the PIU level?

1st person absolutive -w versus oblique -m The idea is that the me-we split in PIE is not singular/plural but absolutive/oblique. The original 1st person nominative singular pronoun would have been 'u' in early PIE, as attested by Hitt. u-uk (<- *u-eǵ), and various 1st person singular -w forms in ancient PIE languages. This would parallel the bi-/min- split from the 'Altaic' languages. Strangely, this split can even be found in Kartvelian (m- verbal prefix versus v-). In Uralic there is very little evidence of this. Only some Samoyedic languages have verbal forms in 1st person -w.

0 notes

Text

I was also going to volunteer some further non-IE languages I might be able to post information on, but it turns out I don’t really have any good cutoff point for “language( familie)s I have resources on” versus “languages I do not have resources on”.

So, instead, here’s a breakdown of stuff that I have in my language-family-specific folders of my papers collections (folders such as “etymologies”, “conlangs” or “methodology” omitted), as a kind of a snapshot of my linguistic interests:

Uralic: 682 items

Finnic: 43

Samoyedic: 40

Ob-Ugric: 37

Proto-Uralic: 32

Samic: 22

Permic: 13

Hungarian: 11

Yukaghir: 8 (not actually a part of Uralic)

Mari: 3

Indo-European: 542 items

Indo-Iranian: 117 (mostly Iranian)

Germanic: 76

Proto-Indo-European: 45

Balto-Slavic: 36

Anatolian: 25

Armenian: 23

Greek: 22

Italic/Latin/Romance: 18

Celtic: 14

Tocharian: 11

Albanian: 4

“Other Siberian”: 99 items (mostly areal or contact linguistics)

Turkic: 31

Tungusic: 7

Sino-Tibetan: 78 items

Afrasian: 74 items

Semitic: 28

Cushitic: 10

Berber: 6

“Other African”: 55 items

SE Asia: 50 items

Austronesian: 15

Austro-Asiatic: 14

America: 41 items

Caucasian: 19 items

Dravidian: 18 items

Japonic: 15 items

misc. other: 11 items (Ainu, Burushaski, Sumerian etc.)

Eskimo-Aleut: 8 items

Australia: 3 items

Basque: 3 items

Of course you’ll have to consider that this sample is in proportion to the size of the language family and availability of research. All other things being equal, I would be e.g. more interested in the Tungusic languages than Turkic, or Tocharian than Latin/Romance. With Uralic a lot the collection is also not sorted by language group as much as e.g. by journal; and I have plenty of literature in my actual bookshelf too, of course.

2 notes

·

View notes