#not strelles related

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Because it came up again while I was reading a fic where someone was upset with Millie for her ablest stance regarding Briarlight's injuries, someone needs to bring up how a good 50% of her fear is very reasonably/likely linked to being a former house-cat.

The clan already treats her and anyone like them - for a commonly used example in fics Daisy - like they're useless wastes of space even when they can do everything a usual warrior can

Like, keep calling out her ableism for sure but someone needs to also tell her she's actually very valid for worrying.

Bonus points that a lot of pet-owners also consider keeping an animal like that alive to be 'making them suffer' and a 'selfish decision' even if the creature is mostly happy in their own home so this could be a double-whammy case of 'the world is plotting against my poor kid'

8 notes

·

View notes

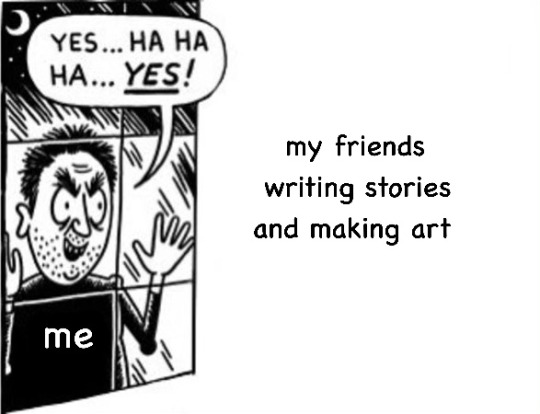

Photo

:D

making this on my phone with very little sleep or consideration, but i think the point stands

#not strelles related#still writing just got hella distracted conlanging for a diff fandom#and of course personal drama - funeral stuff rip

102K notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm telling you now that when I commented on your rewrite originally, I did not expect any of this... And by God you never fail to impress me more with each update you do, it's honestly astounding how you've managed to so skillfully portray each character's emotions and quietly give them arcs. I see you over there giving Ravenwing some confidence points 👀 I've never seen a Ravenwing with a personality and storyline like this, he is such an amazing character. I haven't even gotten to Fireheart, Tigerclaw, BLUESTAR. I'll admit, I have a silent dislike for canon Bluestar. But your version of Bluestar is freaking amazing, I especially love the scene with her and Fireheart during their training when she gets angry. She's not just a perfect, noble warrior with a tragic ending anymore (This is excluding the content from Bluestar's Prophecy). SHE HAS FAULTS! And Fireheart, showing him having the noble, justice seeking personality while also having him be an emotionally complex and relatable character is awesome! Fireheart is no longer a Mary Sue type character who is creepily in love with a dead woman who he spoke to twice! Tigerclaw has depth for once, he isn't just some evil guy anymore! He feels fear, he feels love, he's more than just a villain. He's shown to be terrifying when Fireheart realizes what his father is capable of, he has a dark side that longs for power AND a soft side that tries to make excuses for the people he loves. HE'S FINALLY COMPLEX!! This is honestly one of my favorite rewrites of all time (although I don't really have a favorite XD andddd excluding those that haven't been written out) alongside Warriors Fire And Water, FatalBlow's Warriors Rewritten, and Strelles. You can rest assured that you have gone above and beyond to create one of the greatest Warriors Rewrites I've ever seen and it's truly payed off.

This is one of those asks that is so wonderfully nice and complimentary that I have absolutely no idea how to answer it with a coherent, thought-provoking response due to being overwhelmed with joy. Just be aware that I AM flailing and hollering to myself, and my pets are very startled.

#SERIOUSLY HOW DO I RESPOND LIKE A DIGNIFIED HUMAN TO SOMETHING THIS MARVELOUS#YELLING TO SAY THANK YOU AND IM GLAD YOU ENJOY THIS FIC#ask#thecatspirits#kind words#i speak

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Helpful References

Reblogs from other blogs and stuff that are helpful both for me and for other warrior cat authors I think. Collected as I see them

---

@animatewarriorcats's Size Refs

---

Fox to Cat Size Comparison

Goose to Cat Size Comparison

Canadian Goose to Cat Size Chart

Other Wild Geese

Blackbird to Cat Size Chart

Badger to Cat Size Comparison

---

Biomes and the Like

---

The Moorland - Bonefall Researched!

---

General Helpful Links

---

Kitten Life Milestones

A bunch of cat patterns and colors

Cat Aging Reference

Cat Breed Height Chart

A List of Wild Cats (Big and Small)

---

Websites I Use

---

Sparrow Garden's Advanced Coat Calculator

Messybeast Coat Colors and Patterns

Bengal Coat Colors and Stuff

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

it's always spmething else with this site

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Go nuts Spotty! There were five editions of Strelles before I got to where I am and the overhaul I'm doing right now makes it 6

… What if I rebooted OFND? As a whole?

I’ve been having a lot of OFND thoughts here recently… I miss it, I wanna bring it back, but I want it to be way more coherent and easy to follow, alongside maybe combining some @/ailurocide lore with the basis of OFND stuffs…

Idk if this makes any sense but uhhh….

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

Into the wild by littledeagonstudios premieres tomorrow

Wicked

#answering asks#wandering-woods-offical#not strelles related#never heard of this particular warriors animation project

1 note

·

View note

Note

So, I just finished ifmlam and god fkin shit I'M IN LOVE WITH IT. NOW I'M JUST SEARCHING AND SEARCHING FOR ANY TIME LOOP RELATED! AARON BURR FICS since it's been a while you've updated (based of to the year already passed) and i hope you have time to indulge me so... What's the musical version for timeline 2? Were the HamBurr feels and angst really strong? Like I really wanna know cause my shipping feels demands to be quenched. Also will the HamBurr be stronger in the next timeline?

aaaah, thank you very much! I’m so glad that you enjoyed it so much!

it has been a while, I started grad school for a PhD in mathematical physics, which ate up a lot of my free time and energy that I’d been using for research and writing of ifmlam that I had in college, and I also got into a couple of dungeons and dragons campaigns because moving to graduate school meant moving several states and made me even more isolated from my friends and I wanted to preemptively strike against that mess before I became miserable, so, like, now I skype with friends on a weekly to bi-weekly basis for some ridiculous adventures, and it has probably saved my mental health, but that has eaten up most of the rest of my free time. (and because one of these campaigns is just my friend writing eleven novels that I’m starring in, has also eaten up a lot of my “this!!! is!!! my!!! new!!! favorite!!! story!!! I!!! want!!! to!!! write!!! fanfic!!!” drive.) (which oops, I kind of have. one epistolary novella of book 2, one mostly just dramatic retelling but with an in-universe letter thrown in of book 3, and I’m working on the second proper epistolary novella right now that covers the events of book 4, which I expect will be done within the month) (they’re very fun, Iria Strell is great) (everything is under my Writing tab on the top of my blog if you are interested in belonging to a fandom of, like, at most five people, but hey, it’s very very gay, there’s a reason why it is nicknamed gay murder elf bachelorette) (I guess book 2 is mostly tragic but book 3 gets very gay)

musical round 2! it exists only in a post, and as a description, no fancy re-written songs or any of that, but a description of it does exist: https://savrenim.tumblr.com/post/154913162666/wheeee-mkay-latest-anon-so-i-am-paranoid-about

as for HamBurr and what happens there, as I have no idea when I’m going to have the time to get back into writing the fic proper, I’ve been planning on posting a detailed outline of absolutely everything I was going to write for all the future rounds, and a whole bunch of the scenes that I have already written for said future rounds, and post it to ao3 as the next “chapter” with the warning of “this is not a chapter it’s spoilers for the whole rest of the fic!!!” and then if/when I have the time and energy and motive to get back into the swing of things, just add in the fully written chapters as they slowly replace bits of the outline. I hope that’ll at least be something, for everyone who has been waiting so patiently. so no spoilers here, but you’ll have that as soon as I start winter break and can actually finish polishing it.

(also. listen. time loops and seers are my favorite. they may or may not have been the twist of the crazy biblical apocalypse novel/trilogy that, like, is never seeing the light of day because it defs had certain problems as I was a teenager when I wrote it but, like, boy was that an interesting twist and archangels and archdemons, and, like, there may or may not be some crazy seer stuff and time looping stuff going down in trash novel that I’m slowly working on now, I’m not sure where else you’ll find timeloops in fanfiction mostly because I haven’t trawled through the Hamilton fanfiction tag in a while but you can rest assured that so far, like, anything I write has an 80% chance of having time shenanigans of some sort or other)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Volvo Wagon Armada

It was the Woodstock of press drives, a car launch fit for a Swedish king or, better yet, a Volvo wagon nut just like me. To commemorate the launch of the V90, its new and large but chic and sleek carryall, we persuaded Volvo to let us drive one of the first examples on U.S. soil—actually former North American CEO Lex Kerssemakers’ personal car—from the company’s corporate U.S. headquarters (since 1964) in Rockleigh, New Jersey, to the site of Volvo’s first-ever and still very much under-construction U.S. factory in Ridgeville, South Carolina. Then back again. Close to 2,000 miles.

The V90 marks not just a new Volvo wagon but also the most upscale one. It’s also a welcome re-staking of the wagon flag on American soil for the Swedish firm, and we wanted to memorialize it properly. Ditto the new factory, even if it’s not finished being built, a facility made possible by a deep-pocketed new owner—China’s Geely—and generous subsidies from the state of South Carolina. It reflects not just the record sales success Volvo has enjoyed lately but also what a fresh credit line worth more than $11 billion and a friendly state government can do for the spring in one’s business plan.

Volvo loaned us its premium hauler ($53,295 base) and helped us find, organize, and support a group of other wagons representing all eras of the company’s extensive history in the genre, along with the cars’ owners to drive them. I brought along my own light green 1967 122S wagon, bought with 80 original miles on the clock but now with 5,000 miles. A few preflight repairs, and it was ready to go the distance.

Loyal Volvo Club of America (VCOA) members all, the owners who answered Volvo’s call to join the wagon armada were mellow, their cars gloriously representing each decade since the first Volvo wagons of the 1950s and all of the carmaker’s successive wagon eras. We had mostly everything—from a show-winning 1959 445 Duett through the 122, 245, 745, 850, 240, V50, V60, all of the V70s, and a handsome 1800ES from the company’s own collection that accompanied us as far as Delaware. I’m only sorry there isn’t room here to thank everyone by name.

What didn’t turn up was a Mitsubishi-derived V40 or any representative of the 900 series, the ultimate evolution of the 700 series wagons, renamed in honor of its independent rear suspension and, in the case of the one we’d like to have seen, the 960, a straight-six motor. A much better car than it gets credit for, cursed by a short lifespan, its absence was noticed.

The 2017 V90 is svelte and comfortable as it leads its historic counterparts on a 2,000-mile road trip.

The final omission from our cavalcade of Volvos was the 145, the progenitor (1968-’74) of all the “boxes” to come, the cars that cemented the Volvo wagon thing by looking more or less the same for a quarter of a century, from the late ’60s until 1993. But divine providence intervened to correct an unconscionable oversight as we ran across a 145, a runner in only semimoderate dishabille, when we stopped at the Sub Rosa Bakery in Richmond, Virginia.

To ensure this crowd of Volvo volunteers wouldn’t go hungry on our station wagon sojourn, we brought along a couple of knowledgeable food professionals for dining tips along the way. Adam Sachs is the editor of Saveur and drives a V70. Jay Strell, a food communications strategist and fellow Brooklyn dweller, keeps a V50. Along for the ride and some light driving duty, they’d leave their own cars at home. Ditto my old friend, painter Fred Ingrams. He left his car—a too-slow-for-America V50 1.6-liter—at home in Norfolk, England, to come on a forced march to South Carolina as a passenger in a different Volvo wagon. He just hadn’t counted on it being 50 years old. Another drop-in from NYC, Jake Gouverneur, owns a Saab 9-5 wagon, but it has a blown head gasket and isn’t going anywhere.

There would, however, be no shotgun seat for Steve Ohlinger of The Auto Shop of Salisbury, Connecticut. A veteran independent Volvo mechanic, former racer, and (something tells me) former hippie, Steve brought his brown 1984 five-speed manual 245 Turbo, a rare bird. His role, to which he readily assented, was to carry The Knowledge and useful spares for when older pieces of Swedish iron fell in the line of interstate duty—except this happened not once.

Throw in a couple of Volvo PR honchos, a videographer in a V90 Cross Country, an event planner or two, plus our Automobile photographers, and there must have been 25 or more of us driving or riding along at any given moment. Teenaged me would have appreciated this concept.

Funny enough, no one ever did get an exact count on the number of participants. I later realized I was too busy driving to notice. Berkeley County, South Carolina, is a long way from Bergen County, northern New Jersey, especially in an 87-horsepower car with a pushrod engine geared to turn something like 3,800 rpm at 65 mph. The journey seems even longer and more sapping when it is conducted during a two-day rainstorm, with ’60s wipers clapping and a ’60s defroster fan hyperventilating while trying to keep up. But like all the old wagons on this trip, the 122S completed the journey without incident and no worse for the wear.

Swedish cream puff: This 1970s P1800ES “shooting brake” still cuts a stylish profile today.

Older models from the last century are one reason Volvo still has a good reputation to fall back on. Return solely to the early part of the 21st century for your wagon memories, and you’ll find Volvos with some major technical failings to answer for, cars that tarnished the company’s long-running longevity and reliability pitch. We definitely feel better about its new cars nowadays, but there is no predicting what age will bring.

On first acquaintance, though, we are impressed with just about everything to do with the black V90 T6 AWD R-Design wagon we’re driving here, though even in a fast, all-wheel-drive car we hoped for something better than the 26 mpg over some 2,000 mostly highway miles. There were undoubtedly economy-sapping power surges for which we were responsible, as there will always be with 316 hp turbo and supercharged 2.0-liter fours. But there were many more hours of economy-minded highway driving. Results closer to the EPA’s suggested 30 mpg (highway) are not too much to ask for.

The V90 looks great, and its leather-lined interior compares favorably to several Germanic alternatives. If nothing else, it’s airy and different. The car drives and rides especially well, with a nimbleness that belies its size. A little more than 16 feet long, it feels like a big, opulent car in the best sense but drives like a smaller one. Naturally, this executive-priced load hauler also comes with all of the tech and telematics features you expect. That is, expect to love, expect to regret, and one that still has us scratching our heads: Pilot Assist II, Volvo’s second-gen semi-autonomous driving system.

With $600 million of Volvo’s own money invested so far and $200 million in state incentives, Volvo expects to have spent $1 billion on the new factory and to have created 4,000 jobs here by 2030.

The latest Pilot Assist no longer requires you to track a lead vehicle, and it operates in self-driving mode at speeds up to 80 mph, which is nice. (Its predecessor topped out at a considerably less useful 32 mph.) But as “semi-autonomous” suggests, Pilot Assist II only steers for you for 18 seconds at a time, at which point a human must provide input, or the car will come gradually to a halt, which seemed dangerous to me. Another concern? The camera-based system orients the vehicle by using painted road lines on either side of the road.

Will the new V90 still be on public roads decades from now? If its forebears are any indication, the outlook is good.

As you might expect once you know how the system works, the car made large corrections following the white lines into corners, often steering later than we would have with more roll and general back and forth than an attentive, sober skipper would have allowed. Also failing to inspire confidence was the discovery that the V90 seemed willing to veer off the highway around bends where the white paint was worn off or pieces of roadway had fallen away, taking the white line with them. Last-minute driver intervention was most emphatically required. So, as with similar systems from other makers, you can’t fully rely on Pilot Assist II because you still can’t take your eyes off the road. It might make you wonder, beyond tech boasts and consumer beta testing, what is the exact point?

A wagon usually boasts the same or better interior space than its jacked-up relations and fraternal twins, and it probably handles better with its lower of center of gravity.

Speaking of points, on the ride back to our hotel one night we got a chance to admire Ohlinger’s 245 Turbo in action. By action, I don’t mean heavy acceleration or drifting but merely having its headlamps turned on. That’s because they’re airport runway lights, an unlikely fitment the Volvo guru realized one day was a more or less straight swap, so he tried it, and guess what? They light up a road as if you plan to land a commercial jetliner on it, waking up everyone for miles and inducing post-traumatic stress syndrome in those unlucky enough to be in front of you when they suddenly catch your light show in their rearview mirror. We kind of liked it and made a mental note to look into the conversion. Although, as Ohlinger pointed out, “When they’re great, they’re great. But when they’re not, they’re really not.”

Bonding bricks: No fewer than 60 years and 229 hp separate the V90 from the author’s 122S wagon. Both have their unique charms.

Bonding Bricks: No fewer than 60 years and 229 hp separate the V90 from the author’s 122S wagon. Both have their unique charms.The following day we headed to the factory site, about an hour’s drive, to inspect it from a distance while photographing all the participants in our station wagon safari. With the plant rising in the background, and the rain miraculously halted, it’s a rare photo that speaks to Volvo’s storied history and equally strong present. Carved here out of swampy woodlands, it represents a minimum investment of $600 million of Volvo’s own money and $200 million in state incentives. Volvo expects to have spent a billion dollars here by 2030 and to have created 4,000 jobs. Perhaps not what you thought of, old timer, when you saw your first 122S wagon all those years ago.

Like the wagons, I was in good shape when we arrived in Charleston for a late lunch. In fairness, however, I must admit I turned over the 122S on several occasions to other drivers while I enjoyed long stints behind the wheel of the V90. The newest, fanciest Volvo wagon yet seemed rocket-ship fast yet delightfully restful, one of the most comfortable rides going, with better seats than most all its modern competition much less those in the 122S, its ancestor from a half century ago. Lack of wind noise lends an amazing quietness to the V90’s cabin, too. Indeed Gouverneur, playing with a decibel-meter app on his phone, explained that the all-wheel-drive model was significantly quieter at 115 mph in the rain with wipers at full chat than the 122S was cruising at 65 mph with wipers off. I can’t speak to the accuracy of this because I was driving, and we all know I would never drive anywhere near that fast.

The Duett was built as a dual-purpose work and personal car and was the only body-on-frame passenger vehicle in Volvo’s U.S. lineup.

This magazine has long maintained that the station wagon format provides the most practical automotive solution for millions more Americans than are buying them now. We understand the auto industry passes time by chasing the latest styling fads, but after being rocked by the ungainly minivan and then crushed by the SUV and the hulking crossovers that followed, the once-best-selling wagon’s pendulum, which swung highest in the 1960s and 1970s, is long overdue to swing back. To the extent that logic plays any part in the matter, which is probably a dubious idea at best, the wagon is more efficient—lighter and more aerodynamic—than its crossover alternative. A wagon usually boasts the same or better interior space than its jacked-up relations and fraternal twins, and it probably handles better with its lower of center of gravity. Almost half the vehicles sold in Europe are wagons. Is life there so much different? We don’t think so.

Gimmicks and scarcity marketing are cool, I guess, but The whole idea presumes scarcity. And our trip to Volvo’s new plant proved the V90 wagon is way too good to be scarce.

Volvo has had success with sedans and even sports cars in America, but it is best known for its wagons, which are standard fixtures of the landscape in many American neighborhoods to this day. In a world of ever-changing automotive ideals, the Volvo wagon is a basic unit of automotive currency for many, the kind that spans generations. In my life, my parents drove a Volvo wagon, I drove them, my kids drove them, and with luck their kids might. Unlike some makers, Volvo’s never left the wagon field behind, and new proof in the form of the V90 warms the heart.

Yet recognizing fashion and catering to what it thinks most people think they want, the company has hastened in the 21st century to keep its lineup of crossovers and SUVs fresh, lively, and growing. Although there’s really nothing bad to say about the XC60, XC90, and upcoming XC40 models, we still prefer these platforms set up for wagon duty, pure and unadulterated. We don’t begrudge Volvo its high riders—they help pay the rent and the high taxes of super-socialist Sweden. We wish the V90, which shares its platform with the XC90, had as an option a third row of seats as does the SUV.

This affection for the wagon form generally and Volvo’s biggest wagon ever specifically is why we can’t help but second-guess the decision to soft sell the model, which is only available via internet order and not off the showroom floor. Dealers will receive as many of the Cross Country version of the V90 as they can afford to stock but no regular wagon V90s without an internet order, which is a shame.

Seven decades of Volvo wagon evolution stages at the brand’s new South Carolina plant after 1,000 miles of driving.

Gimmicks and scarcity marketing are cool, I guess, but something is wrong. The whole idea presumes scarcity. And our trip to Volvo’s new plant (which won’t build the V90 but rather the 60 series sedan and SUV) proved the V90 wagon is way too good to be scarce. With a little work, it could be the belle of the ball in affluent communities across America, a big ol’ posh station wagon for our times, an anti-SUV. Wagons rule, and if anyone ought to know that, it’s Volvo.

Source: http://chicagoautohaus.com/the-volvo-wagon-armada/

from Chicago Today https://chicagocarspot.wordpress.com/2017/12/18/the-volvo-wagon-armada/

0 notes

Text

The Volvo Wagon Armada

It was the Woodstock of press drives, a car launch fit for a Swedish king or, better yet, a Volvo wagon nut just like me. To commemorate the launch of the V90, its new and large but chic and sleek carryall, we persuaded Volvo to let us drive one of the first examples on U.S. soil—actually former North American CEO Lex Kerssemakers’ personal car—from the company’s corporate U.S. headquarters (since 1964) in Rockleigh, New Jersey, to the site of Volvo’s first-ever and still very much under-construction U.S. factory in Ridgeville, South Carolina. Then back again. Close to 2,000 miles.

The V90 marks not just a new Volvo wagon but also the most upscale one. It’s also a welcome re-staking of the wagon flag on American soil for the Swedish firm, and we wanted to memorialize it properly. Ditto the new factory, even if it’s not finished being built, a facility made possible by a deep-pocketed new owner—China’s Geely—and generous subsidies from the state of South Carolina. It reflects not just the record sales success Volvo has enjoyed lately but also what a fresh credit line worth more than $11 billion and a friendly state government can do for the spring in one’s business plan.

Volvo loaned us its premium hauler ($53,295 base) and helped us find, organize, and support a group of other wagons representing all eras of the company’s extensive history in the genre, along with the cars’ owners to drive them. I brought along my own light green 1967 122S wagon, bought with 80 original miles on the clock but now with 5,000 miles. A few preflight repairs, and it was ready to go the distance.

Loyal Volvo Club of America (VCOA) members all, the owners who answered Volvo’s call to join the wagon armada were mellow, their cars gloriously representing each decade since the first Volvo wagons of the 1950s and all of the carmaker’s successive wagon eras. We had mostly everything—from a show-winning 1959 445 Duett through the 122, 245, 745, 850, 240, V50, V60, all of the V70s, and a handsome 1800ES from the company’s own collection that accompanied us as far as Delaware. I’m only sorry there isn’t room here to thank everyone by name.

What didn’t turn up was a Mitsubishi-derived V40 or any representative of the 900 series, the ultimate evolution of the 700 series wagons, renamed in honor of its independent rear suspension and, in the case of the one we’d like to have seen, the 960, a straight-six motor. A much better car than it gets credit for, cursed by a short lifespan, its absence was noticed.

The 2017 V90 is svelte and comfortable as it leads its historic counterparts on a 2,000-mile road trip.

The final omission from our cavalcade of Volvos was the 145, the progenitor (1968-’74) of all the “boxes” to come, the cars that cemented the Volvo wagon thing by looking more or less the same for a quarter of a century, from the late ’60s until 1993. But divine providence intervened to correct an unconscionable oversight as we ran across a 145, a runner in only semimoderate dishabille, when we stopped at the Sub Rosa Bakery in Richmond, Virginia.

To ensure this crowd of Volvo volunteers wouldn’t go hungry on our station wagon sojourn, we brought along a couple of knowledgeable food professionals for dining tips along the way. Adam Sachs is the editor of Saveur and drives a V70. Jay Strell, a food communications strategist and fellow Brooklyn dweller, keeps a V50. Along for the ride and some light driving duty, they’d leave their own cars at home. Ditto my old friend, painter Fred Ingrams. He left his car—a too-slow-for-America V50 1.6-liter—at home in Norfolk, England, to come on a forced march to South Carolina as a passenger in a different Volvo wagon. He just hadn’t counted on it being 50 years old. Another drop-in from NYC, Jake Gouverneur, owns a Saab 9-5 wagon, but it has a blown head gasket and isn’t going anywhere.

There would, however, be no shotgun seat for Steve Ohlinger of The Auto Shop of Salisbury, Connecticut. A veteran independent Volvo mechanic, former racer, and (something tells me) former hippie, Steve brought his brown 1984 five-speed manual 245 Turbo, a rare bird. His role, to which he readily assented, was to carry The Knowledge and useful spares for when older pieces of Swedish iron fell in the line of interstate duty—except this happened not once.

Throw in a couple of Volvo PR honchos, a videographer in a V90 Cross Country, an event planner or two, plus our Automobile photographers, and there must have been 25 or more of us driving or riding along at any given moment. Teenaged me would have appreciated this concept.

Funny enough, no one ever did get an exact count on the number of participants. I later realized I was too busy driving to notice. Berkeley County, South Carolina, is a long way from Bergen County, northern New Jersey, especially in an 87-horsepower car with a pushrod engine geared to turn something like 3,800 rpm at 65 mph. The journey seems even longer and more sapping when it is conducted during a two-day rainstorm, with ’60s wipers clapping and a ’60s defroster fan hyperventilating while trying to keep up. But like all the old wagons on this trip, the 122S completed the journey without incident and no worse for the wear.

Swedish cream puff: This 1970s P1800ES “shooting brake” still cuts a stylish profile today.

Older models from the last century are one reason Volvo still has a good reputation to fall back on. Return solely to the early part of the 21st century for your wagon memories, and you’ll find Volvos with some major technical failings to answer for, cars that tarnished the company’s long-running longevity and reliability pitch. We definitely feel better about its new cars nowadays, but there is no predicting what age will bring.

On first acquaintance, though, we are impressed with just about everything to do with the black V90 T6 AWD R-Design wagon we’re driving here, though even in a fast, all-wheel-drive car we hoped for something better than the 26 mpg over some 2,000 mostly highway miles. There were undoubtedly economy-sapping power surges for which we were responsible, as there will always be with 316 hp turbo and supercharged 2.0-liter fours. But there were many more hours of economy-minded highway driving. Results closer to the EPA’s suggested 30 mpg (highway) are not too much to ask for.

The V90 looks great, and its leather-lined interior compares favorably to several Germanic alternatives. If nothing else, it’s airy and different. The car drives and rides especially well, with a nimbleness that belies its size. A little more than 16 feet long, it feels like a big, opulent car in the best sense but drives like a smaller one. Naturally, this executive-priced load hauler also comes with all of the tech and telematics features you expect. That is, expect to love, expect to regret, and one that still has us scratching our heads: Pilot Assist II, Volvo’s second-gen semi-autonomous driving system.

With $600 million of Volvo’s own money invested so far and $200 million in state incentives, Volvo expects to have spent $1 billion on the new factory and to have created 4,000 jobs here by 2030.

The latest Pilot Assist no longer requires you to track a lead vehicle, and it operates in self-driving mode at speeds up to 80 mph, which is nice. (Its predecessor topped out at a considerably less useful 32 mph.) But as “semi-autonomous” suggests, Pilot Assist II only steers for you for 18 seconds at a time, at which point a human must provide input, or the car will come gradually to a halt, which seemed dangerous to me. Another concern? The camera-based system orients the vehicle by using painted road lines on either side of the road.

Will the new V90 still be on public roads decades from now? If its forebears are any indication, the outlook is good.

As you might expect once you know how the system works, the car made large corrections following the white lines into corners, often steering later than we would have with more roll and general back and forth than an attentive, sober skipper would have allowed. Also failing to inspire confidence was the discovery that the V90 seemed willing to veer off the highway around bends where the white paint was worn off or pieces of roadway had fallen away, taking the white line with them. Last-minute driver intervention was most emphatically required. So, as with similar systems from other makers, you can’t fully rely on Pilot Assist II because you still can’t take your eyes off the road. It might make you wonder, beyond tech boasts and consumer beta testing, what is the exact point?

A wagon usually boasts the same or better interior space than its jacked-up relations and fraternal twins, and it probably handles better with its lower of center of gravity.

Speaking of points, on the ride back to our hotel one night we got a chance to admire Ohlinger’s 245 Turbo in action. By action, I don’t mean heavy acceleration or drifting but merely having its headlamps turned on. That’s because they’re airport runway lights, an unlikely fitment the Volvo guru realized one day was a more or less straight swap, so he tried it, and guess what? They light up a road as if you plan to land a commercial jetliner on it, waking up everyone for miles and inducing post-traumatic stress syndrome in those unlucky enough to be in front of you when they suddenly catch your light show in their rearview mirror. We kind of liked it and made a mental note to look into the conversion. Although, as Ohlinger pointed out, “When they’re great, they’re great. But when they’re not, they’re really not.”

Bonding bricks: No fewer than 60 years and 229 hp separate the V90 from the author’s 122S wagon. Both have their unique charms.

Bonding Bricks: No fewer than 60 years and 229 hp separate the V90 from the author’s 122S wagon. Both have their unique charms.The following day we headed to the factory site, about an hour’s drive, to inspect it from a distance while photographing all the participants in our station wagon safari. With the plant rising in the background, and the rain miraculously halted, it’s a rare photo that speaks to Volvo’s storied history and equally strong present. Carved here out of swampy woodlands, it represents a minimum investment of $600 million of Volvo’s own money and $200 million in state incentives. Volvo expects to have spent a billion dollars here by 2030 and to have created 4,000 jobs. Perhaps not what you thought of, old timer, when you saw your first 122S wagon all those years ago.

Like the wagons, I was in good shape when we arrived in Charleston for a late lunch. In fairness, however, I must admit I turned over the 122S on several occasions to other drivers while I enjoyed long stints behind the wheel of the V90. The newest, fanciest Volvo wagon yet seemed rocket-ship fast yet delightfully restful, one of the most comfortable rides going, with better seats than most all its modern competition much less those in the 122S, its ancestor from a half century ago. Lack of wind noise lends an amazing quietness to the V90’s cabin, too. Indeed Gouverneur, playing with a decibel-meter app on his phone, explained that the all-wheel-drive model was significantly quieter at 115 mph in the rain with wipers at full chat than the 122S was cruising at 65 mph with wipers off. I can’t speak to the accuracy of this because I was driving, and we all know I would never drive anywhere near that fast.

The Duett was built as a dual-purpose work and personal car and was the only body-on-frame passenger vehicle in Volvo’s U.S. lineup.

This magazine has long maintained that the station wagon format provides the most practical automotive solution for millions more Americans than are buying them now. We understand the auto industry passes time by chasing the latest styling fads, but after being rocked by the ungainly minivan and then crushed by the SUV and the hulking crossovers that followed, the once-best-selling wagon’s pendulum, which swung highest in the 1960s and 1970s, is long overdue to swing back. To the extent that logic plays any part in the matter, which is probably a dubious idea at best, the wagon is more efficient—lighter and more aerodynamic—than its crossover alternative. A wagon usually boasts the same or better interior space than its jacked-up relations and fraternal twins, and it probably handles better with its lower of center of gravity. Almost half the vehicles sold in Europe are wagons. Is life there so much different? We don’t think so.

Gimmicks and scarcity marketing are cool, I guess, but The whole idea presumes scarcity. And our trip to Volvo’s new plant proved the V90 wagon is way too good to be scarce.

Volvo has had success with sedans and even sports cars in America, but it is best known for its wagons, which are standard fixtures of the landscape in many American neighborhoods to this day. In a world of ever-changing automotive ideals, the Volvo wagon is a basic unit of automotive currency for many, the kind that spans generations. In my life, my parents drove a Volvo wagon, I drove them, my kids drove them, and with luck their kids might. Unlike some makers, Volvo’s never left the wagon field behind, and new proof in the form of the V90 warms the heart.

Yet recognizing fashion and catering to what it thinks most people think they want, the company has hastened in the 21st century to keep its lineup of crossovers and SUVs fresh, lively, and growing. Although there’s really nothing bad to say about the XC60, XC90, and upcoming XC40 models, we still prefer these platforms set up for wagon duty, pure and unadulterated. We don’t begrudge Volvo its high riders—they help pay the rent and the high taxes of super-socialist Sweden. We wish the V90, which shares its platform with the XC90, had as an option a third row of seats as does the SUV.

This affection for the wagon form generally and Volvo’s biggest wagon ever specifically is why we can’t help but second-guess the decision to soft sell the model, which is only available via internet order and not off the showroom floor. Dealers will receive as many of the Cross Country version of the V90 as they can afford to stock but no regular wagon V90s without an internet orde from Performance Junk WP Feed 4 http://ift.tt/2yT2zt6 via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

So admittedly I just love Rules Lawyering. I don't really have an opinion here other than pointing out that this is how lion prides work! Where the pregnant lioness leaves and isn't a member of the pride until they return when their cubs are big enough. It would be interesting if this was some kind of Old Rule that Leafpool has like, accidentally invoked.

So the kits are legal bc for the time of their conception, she was a Rogue unaffiliated with the clans and she brought them back before the usual time (before they were born) so they're not even hers for real so the kits are, in-practice; adopted rouge kits.

HELLO! Hi! I'm back to say random stuff that's been screaming in the back of my head for multiple years again! So, for like, 2-3 years now, I've been thinking about the Leaf x Crow relationship and Leafpool was punished for having half clan kittens. By Warrior Cats understanding of kittens, Leafpool HAS broken the code. Yes? We all agree? Good! Now let me propose something to you I literally have never heard anyone talk about with Leafpool. Conceivement. Y'know when you have babies, you need to actually conceive them first. Now, Warrior Cats doesn't have any understanding of conceivement because it's a childrens book series obviously. But, we do and our characters probably do too, for those of us who are teens or adults. Leafpool was away for one night with Crowfeather. We don't know the exact time in relation to this that Leafpool's kittens were born, but, one could argue it is highly possible that in a realistic setting that Leafpool could have conceived her kits on that night. By now you're probably asking what the fuck I'm rambling on about. BUT HEAR ME OUT PLEASE! On that one single night, Leafpool and Crowfeather had run away together, AWAY from the Clans. Which means for that one night, they were rogues. WHICH IN TURN MEANS that if Leafpool had conceived her kits on that very same night, that by our understanding, Leafpool did NOT break the code. Now, one could argue that depends on what your understanding of Clan law is. Do 'half-clan' kits need to be birthed outside the Clan in order to be considered 'legal' or can they be conceived outside the Clan and then the mother give birth in the Clan without them being considered 'illegal.' I genuinely want to know what people think about this? Again, one could argue it is highly possible Leafpool conceived her kits before that night but to our knowledge Leafpool and Crowfeather had no romantic interactions after that night. Like, if somebody could work to pinpoint the window of time for this, that would be really cool or rather I'd love to see a version of Leafpool arguing to the Clan that her kits are not 'illegal.'

WELLLLL! Thank you for coming to my TedTalk! I appreciate everyone listening to me ramble.

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Ah, I was about to start asking if WindClan had some sort of superior fur-care routine. XD

Fr though, Magpiestar is old, I'm surprised that Barkface managed to outlive him by like, two years. I think he was actually one of the oldest cats in the series, next to Mistystar of course. Then again, the differences in the allegiances of Yellowfang and Tallstar's SE is wack.

Also, the fact that Barkface made it through the journey to the lake just fine while Tallstar was leaning against Onewhisker for support is kind of funny to me, since Tallstar was the moor runner between the two of them. He was getting more exercise, running more than Barkface ever did in his entire life and you're telling me that Tallstar's the one that's struggling? 🤨

Either it's own of those times where you just outlive someone younger than you, or Barkface has some anti-aging herbs he forgot to tell Tallstar about. (Or Tallstar's just weak from starving. That's probably the most reasonable explanation.)

Lmao yeah - Magpiestar of Strelles probably won't ever really look old from a distance due to his fortunate fur patterning. Plus, he uses more than just Raging Wind techniques lmao - he also uses skills and abilities he picked up from his time as a Seeker from the Kingdoms.

Yeah Yellowfang's Secret is in such a weird limbo place in the timeline - anyone trying to figure things out via where everything happened in canon will always get tripped up on that book. You can kinda line up Tallstar's Revenge and Bluestar's Prophecy via the camp invasion which I did and do think is stupid Fourtrees is in between Wind and Thunder what? but Yellowfang's Secret is just left enough of those two books and Crookedstar's Promise to be confusing

Lmao yeah - Tallstar was probably suffering the effects of not just starving but of everything that happened to WindClan up until that part. Cause I imagine he put his clanmates first through all the tragedies but pre-lake windclan went through A Lot towards the end there. Being driven out, the deaths that resulted from that and when they came back they had to fight Shadow and River out of their territory, they lost more warriors during their camp battle and then ShadowClan invaded again on Tigerstar's orders

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Volvo Wagon Armada

It was the Woodstock of press drives, a car launch fit for a Swedish king or, better yet, a Volvo wagon nut just like me. To commemorate the launch of the V90, its new and large but chic and sleek carryall, we persuaded Volvo to let us drive one of the first examples on U.S. soil—actually former North American CEO Lex Kerssemakers’ personal car—from the company’s corporate U.S. headquarters (since 1964) in Rockleigh, New Jersey, to the site of Volvo’s first-ever and still very much under-construction U.S. factory in Ridgeville, South Carolina. Then back again. Close to 2,000 miles.

The V90 marks not just a new Volvo wagon but also the most upscale one. It’s also a welcome re-staking of the wagon flag on American soil for the Swedish firm, and we wanted to memorialize it properly. Ditto the new factory, even if it’s not finished being built, a facility made possible by a deep-pocketed new owner—China’s Geely—and generous subsidies from the state of South Carolina. It reflects not just the record sales success Volvo has enjoyed lately but also what a fresh credit line worth more than $11 billion and a friendly state government can do for the spring in one’s business plan.

Volvo loaned us its premium hauler ($53,295 base) and helped us find, organize, and support a group of other wagons representing all eras of the company’s extensive history in the genre, along with the cars’ owners to drive them. I brought along my own light green 1967 122S wagon, bought with 80 original miles on the clock but now with 5,000 miles. A few preflight repairs, and it was ready to go the distance.

Loyal Volvo Club of America (VCOA) members all, the owners who answered Volvo’s call to join the wagon armada were mellow, their cars gloriously representing each decade since the first Volvo wagons of the 1950s and all of the carmaker’s successive wagon eras. We had mostly everything—from a show-winning 1959 445 Duett through the 122, 245, 745, 850, 240, V50, V60, all of the V70s, and a handsome 1800ES from the company’s own collection that accompanied us as far as Delaware. I’m only sorry there isn’t room here to thank everyone by name.

What didn’t turn up was a Mitsubishi-derived V40 or any representative of the 900 series, the ultimate evolution of the 700 series wagons, renamed in honor of its independent rear suspension and, in the case of the one we’d like to have seen, the 960, a straight-six motor. A much better car than it gets credit for, cursed by a short lifespan, its absence was noticed.

The 2017 V90 is svelte and comfortable as it leads its historic counterparts on a 2,000-mile road trip.

The final omission from our cavalcade of Volvos was the 145, the progenitor (1968-’74) of all the “boxes” to come, the cars that cemented the Volvo wagon thing by looking more or less the same for a quarter of a century, from the late ’60s until 1993. But divine providence intervened to correct an unconscionable oversight as we ran across a 145, a runner in only semimoderate dishabille, when we stopped at the Sub Rosa Bakery in Richmond, Virginia.

To ensure this crowd of Volvo volunteers wouldn’t go hungry on our station wagon sojourn, we brought along a couple of knowledgeable food professionals for dining tips along the way. Adam Sachs is the editor of Saveur and drives a V70. Jay Strell, a food communications strategist and fellow Brooklyn dweller, keeps a V50. Along for the ride and some light driving duty, they’d leave their own cars at home. Ditto my old friend, painter Fred Ingrams. He left his car—a too-slow-for-America V50 1.6-liter—at home in Norfolk, England, to come on a forced march to South Carolina as a passenger in a different Volvo wagon. He just hadn’t counted on it being 50 years old. Another drop-in from NYC, Jake Gouverneur, owns a Saab 9-5 wagon, but it has a blown head gasket and isn’t going anywhere.

There would, however, be no shotgun seat for Steve Ohlinger of The Auto Shop of Salisbury, Connecticut. A veteran independent Volvo mechanic, former racer, and (something tells me) former hippie, Steve brought his brown 1984 five-speed manual 245 Turbo, a rare bird. His role, to which he readily assented, was to carry The Knowledge and useful spares for when older pieces of Swedish iron fell in the line of interstate duty—except this happened not once.

Throw in a couple of Volvo PR honchos, a videographer in a V90 Cross Country, an event planner or two, plus our Automobile photographers, and there must have been 25 or more of us driving or riding along at any given moment. Teenaged me would have appreciated this concept.

Funny enough, no one ever did get an exact count on the number of participants. I later realized I was too busy driving to notice. Berkeley County, South Carolina, is a long way from Bergen County, northern New Jersey, especially in an 87-horsepower car with a pushrod engine geared to turn something like 3,800 rpm at 65 mph. The journey seems even longer and more sapping when it is conducted during a two-day rainstorm, with ’60s wipers clapping and a ’60s defroster fan hyperventilating while trying to keep up. But like all the old wagons on this trip, the 122S completed the journey without incident and no worse for the wear.

Swedish cream puff: This 1970s P1800ES “shooting brake” still cuts a stylish profile today.

Older models from the last century are one reason Volvo still has a good reputation to fall back on. Return solely to the early part of the 21st century for your wagon memories, and you’ll find Volvos with some major technical failings to answer for, cars that tarnished the company’s long-running longevity and reliability pitch. We definitely feel better about its new cars nowadays, but there is no predicting what age will bring.

On first acquaintance, though, we are impressed with just about everything to do with the black V90 T6 AWD R-Design wagon we’re driving here, though even in a fast, all-wheel-drive car we hoped for something better than the 26 mpg over some 2,000 mostly highway miles. There were undoubtedly economy-sapping power surges for which we were responsible, as there will always be with 316 hp turbo and supercharged 2.0-liter fours. But there were many more hours of economy-minded highway driving. Results closer to the EPA’s suggested 30 mpg (highway) are not too much to ask for.

The V90 looks great, and its leather-lined interior compares favorably to several Germanic alternatives. If nothing else, it’s airy and different. The car drives and rides especially well, with a nimbleness that belies its size. A little more than 16 feet long, it feels like a big, opulent car in the best sense but drives like a smaller one. Naturally, this executive-priced load hauler also comes with all of the tech and telematics features you expect. That is, expect to love, expect to regret, and one that still has us scratching our heads: Pilot Assist II, Volvo’s second-gen semi-autonomous driving system.

With $600 million of Volvo’s own money invested so far and $200 million in state incentives, Volvo expects to have spent $1 billion on the new factory and to have created 4,000 jobs here by 2030.

The latest Pilot Assist no longer requires you to track a lead vehicle, and it operates in self-driving mode at speeds up to 80 mph, which is nice. (Its predecessor topped out at a considerably less useful 32 mph.) But as “semi-autonomous” suggests, Pilot Assist II only steers for you for 18 seconds at a time, at which point a human must provide input, or the car will come gradually to a halt, which seemed dangerous to me. Another concern? The camera-based system orients the vehicle by using painted road lines on either side of the road.

Will the new V90 still be on public roads decades from now? If its forebears are any indication, the outlook is good.

As you might expect once you know how the system works, the car made large corrections following the white lines into corners, often steering later than we would have with more roll and general back and forth than an attentive, sober skipper would have allowed. Also failing to inspire confidence was the discovery that the V90 seemed willing to veer off the highway around bends where the white paint was worn off or pieces of roadway had fallen away, taking the white line with them. Last-minute driver intervention was most emphatically required. So, as with similar systems from other makers, you can’t fully rely on Pilot Assist II because you still can’t take your eyes off the road. It might make you wonder, beyond tech boasts and consumer beta testing, what is the exact point?

A wagon usually boasts the same or better interior space than its jacked-up relations and fraternal twins, and it probably handles better with its lower of center of gravity.

Speaking of points, on the ride back to our hotel one night we got a chance to admire Ohlinger’s 245 Turbo in action. By action, I don’t mean heavy acceleration or drifting but merely having its headlamps turned on. That’s because they’re airport runway lights, an unlikely fitment the Volvo guru realized one day was a more or less straight swap, so he tried it, and guess what? They light up a road as if you plan to land a commercial jetliner on it, waking up everyone for miles and inducing post-traumatic stress syndrome in those unlucky enough to be in front of you when they suddenly catch your light show in their rearview mirror. We kind of liked it and made a mental note to look into the conversion. Although, as Ohlinger pointed out, “When they’re great, they’re great. But when they’re not, they’re really not.”

Bonding bricks: No fewer than 60 years and 229 hp separate the V90 from the author’s 122S wagon. Both have their unique charms.

Bonding Bricks: No fewer than 60 years and 229 hp separate the V90 from the author’s 122S wagon. Both have their unique charms.The following day we headed to the factory site, about an hour’s drive, to inspect it from a distance while photographing all the participants in our station wagon safari. With the plant rising in the background, and the rain miraculously halted, it’s a rare photo that speaks to Volvo’s storied history and equally strong present. Carved here out of swampy woodlands, it represents a minimum investment of $600 million of Volvo’s own money and $200 million in state incentives. Volvo expects to have spent a billion dollars here by 2030 and to have created 4,000 jobs. Perhaps not what you thought of, old timer, when you saw your first 122S wagon all those years ago.

Like the wagons, I was in good shape when we arrived in Charleston for a late lunch. In fairness, however, I must admit I turned over the 122S on several occasions to other drivers while I enjoyed long stints behind the wheel of the V90. The newest, fanciest Volvo wagon yet seemed rocket-ship fast yet delightfully restful, one of the most comfortable rides going, with better seats than most all its modern competition much less those in the 122S, its ancestor from a half century ago. Lack of wind noise lends an amazing quietness to the V90’s cabin, too. Indeed Gouverneur, playing with a decibel-meter app on his phone, explained that the all-wheel-drive model was significantly quieter at 115 mph in the rain with wipers at full chat than the 122S was cruising at 65 mph with wipers off. I can’t speak to the accuracy of this because I was driving, and we all know I would never drive anywhere near that fast.

The Duett was built as a dual-purpose work and personal car and was the only body-on-frame passenger vehicle in Volvo’s U.S. lineup.

This magazine has long maintained that the station wagon format provides the most practical automotive solution for millions more Americans than are buying them now. We understand the auto industry passes time by chasing the latest styling fads, but after being rocked by the ungainly minivan and then crushed by the SUV and the hulking crossovers that followed, the once-best-selling wagon’s pendulum, which swung highest in the 1960s and 1970s, is long overdue to swing back. To the extent that logic plays any part in the matter, which is probably a dubious idea at best, the wagon is more efficient—lighter and more aerodynamic—than its crossover alternative. A wagon usually boasts the same or better interior space than its jacked-up relations and fraternal twins, and it probably handles better with its lower of center of gravity. Almost half the vehicles sold in Europe are wagons. Is life there so much different? We don’t think so.

Gimmicks and scarcity marketing are cool, I guess, but The whole idea presumes scarcity. And our trip to Volvo’s new plant proved the V90 wagon is way too good to be scarce.

Volvo has had success with sedans and even sports cars in America, but it is best known for its wagons, which are standard fixtures of the landscape in many American neighborhoods to this day. In a world of ever-changing automotive ideals, the Volvo wagon is a basic unit of automotive currency for many, the kind that spans generations. In my life, my parents drove a Volvo wagon, I drove them, my kids drove them, and with luck their kids might. Unlike some makers, Volvo’s never left the wagon field behind, and new proof in the form of the V90 warms the heart.

Yet recognizing fashion and catering to what it thinks most people think they want, the company has hastened in the 21st century to keep its lineup of crossovers and SUVs fresh, lively, and growing. Although there’s really nothing bad to say about the XC60, XC90, and upcoming XC40 models, we still prefer these platforms set up for wagon duty, pure and unadulterated. We don’t begrudge Volvo its high riders—they help pay the rent and the high taxes of super-socialist Sweden. We wish the V90, which shares its platform with the XC90, had as an option a third row of seats as does the SUV.

This affection for the wagon form generally and Volvo’s biggest wagon ever specifically is why we can’t help but second-guess the decision to soft sell the model, which is only available via internet order and not off the showroom floor. Dealers will receive as many of the Cross Country version of the V90 as they can afford to stock but no regular wagon V90s without an internet orde from Performance Junk Blogger Feed 4 http://ift.tt/2yT2zt6 via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Higher axial tilt to make the whole planet warmer/more tropical, there's a massive set of mountains (more like the rockies) with steep talk peaks. Inner side of the mountain should have a rain-shadow - where the peak of the mountain stops the rain from passing over making one side a temperate forest-like area and the other side is a desert

Desert animals tend to be nocturnal to avoid the sun, have things/traits that allow them to store fat or water, a tendacy towards digging to avoid sunlight.

Mind you, these are for warm deserts. A Tundra/cold desert is very different

Grr don’t know how to make creatures work I am stumped

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Of Wolves And Ravens: As Told By Three Letters Sent From Cloudfall Fort

For those of you have been following gay murder elf bachelorette campaign (In Their Footsteps We Shall Follow), we recently finished Book 2: Of Wolves And Ravens, and I have A Lot Of Feelings about it. Because I am Extremely Extra, I tend to write in-character letters to NPCs that I then send to my DM. The three letters written for this book tell a complete and self-contained story--at this point, nearly a novella--and it’s not quite fanfiction, as it is canon in-universe; certainly not my own work, as all of the brilliance behind it was written by Jeremy, I just lived it and was moving around one little pawn; but together these letters been far more than just a game to me. so after checking with Jeremy, I decided to post them here. If you are a fan of my writing and want a window into the world that is right now one of the stories that I care about the most, well, here is what I have been doing with my heart and with my time. No prior knowledge is necessary and actually I’m not sure how you would have prior knowledge what are you doing listening to my skype calls?

Iria Stell, the author of the letters, is a 17-year-old soldier of the Caedic army; writing first to a scientist Vennikus Callo whom she had encountered a few months prior who gave her a potion to test with only the instructions of “it will be useful in a fight, just like the previous one”; second to Maldai Varricon, her mentor and commanding officer since she joined the army at age 14; and third to Arcadia Dominus, her rival-turned-crush-turned-maybe-girlfriend, whom she left behind at the Surrian front when Varricon sent her and Talvus back to the Capital to take the Trials in the hopes that they would climb to higher military or public office. It is perhaps significant to mention that Talvus is also barely more than a kid, being only about 22 himself, and became Iria’s first and arguably only friend, ever since she arrived in Varricon’s unit, he was delighted he was no longer the youngest, and immediately nicknamed her ‘Stoneface Junior’, and thus began their unbreakable friendship. All other characters are new to this book, and will be introduced as they appear. Iria Strell is played by me. Corporal Dante Maxim is played by my brother, Eddie, who was a guest PC in this arc. Everyone else is played by Jeremy. A number of the cool descriptions are Jeremy. And all the gorgeous battle descriptions are all Jeremy. He’s really damn good at fight choreography.

It is worth noting: this is a story about war. Told from the side of the bad guys, who are kind of brutal. Trigger warnings of violence and death. There is not really any gore outright described in detail, although there are a few times that rather nasty wounds are received and reported clinically. If that sort of thing bothers you, I would not recommend reading!

Otherwise, with no further ado, presenting, Of Wolves And Ravens: As Told By Three Letters Sent From Cloudfall Fort.

____________________

To Vennikus Callo, Black Lotus Labs, Insul

I have made use of the potion that you left me with, and am writing to report the results.

I took it at the beginning of a fight against Highland Rat Clan orcs. The potion kicked in instantaneously, and it lasted a substantial amount of time: the entire duration of the fight, and a few minutes afterwards as well. I would estimate about four minutes total.

The effect to my vision was by far the most noticeable. I immediately began to see lines in the periphery of my sight, patterns of footwork from weight distribution and momentum of my enemies, which allowed me to move more quickly than I would normally in a fight, and allowed me to perform maneuvers that I would not otherwise attempt, as I could instinctively predict—literally see faster than I could have calculated on my own—the locations in which their stances were weak. Secondly, there was a dramatic increase in my strength. I would say that easily under the influence of the potion my strength doubled, and when I concentrated to push to fight at my full capacity, I was striking at thrice what my normal abilities would allow. I was able to kill three Rat Clan orcs and one Salamander Clan elf, holding off an ambush party of over a dozen with only one companion, before Caedic reinforcements arrived.

However, when I took it, I felt hunger beyond any hunger I have felt before in my life; I would describe it as starving to the point of pain equal to that of taking an indirect but substantial wound. Past the initial shock and blow of it, it did not affect my ability to fight nor was it a severe distraction; however, I would caution you that I have trained to ignore pain and exhaustion during a fight, and if you hope to eventually release this potion for wide-scale consumption, this might be a considerable drawback. The hunger did not go away as the other effects of the potion wore off, and it took rations equal to about two and a half standard meals, eaten in under five minutes, before I felt normal again. There were no other persisting effects to the best of my knowledge in the hours or days that followed.

I am sixty-seven inches tall and a little over nine stone, and seventeen years seven months aged, so I do not have the proportions of an adult soldier; you can discard this if the information is useless to you, but perhaps the relative body mass to the potency of the potion could have caused the side effects to emerge. I did not take it on an empty stomach; I had eaten standard issue hard biscuit rations but ten minutes before. I believe the composition of those is primarily flour and water; the exact recipe should not be hard to look up if mundane chemical interactions are a consideration. I had no active spells or enchantments on me at the time of consumption, nor do I make regular use of such things; I have not been poisoned or sickened recently, nor have I taken a potion, either magical or alchemical, since a standard issue healing potion during a battle at the Surrian front a month ago, and the one you gave me at the Fae font before that.

If there is any information that I have unwittingly omitted, please write immediately that I might rectify this. I am currently en route to the Capital to take the Trials and attempt to join the clergy, so any letter addressed to me ought to be sent to the Strell family estate there.

With sincerity, Iria Strell

____________________

Sergeant Major Maldai Varricon, Specialist Unit c.Varricon The 3rd Legion, Serae

Dear Maldai,

I am writing, as a friend, because I could gravely use your guidance right now. It has been a trying week; I have nearly died multiple times, I have watched a unit of good Caedic soldiers slaughtered before my eyes, helpless, and I am full of doubts about things I had previously considered certain. Second Lieutenant Vitan of the 8th has submitted a full official report about the incidents that transpired, but I am not sure that any report could capture…could capture what I am to write below.

The journey to the Capital was fairly uneventful until about half a day’s march from Cloudfall fort. We had made good time in the prior month; I’d kept up practicing my forms every morning and evening, which meant that Talvus and I tired at about the same time every day, and I managed to persuade him to teach me basic arcane theory as we walked so that if I am ever consulted for tactical planning, I might have more insight into what a single mage or an arcane unit can and cannot do.

(Managed to persuade. More like we ran out of conversation topics about banal matters by the end of the third day, and Talvus leapt at the opportunity to talk about something even marginally related to his research projects. I think I’ve picked up the basics acceptably; I was able to keep up with him. He is a fine teacher, although he spoke very fast, and I only had so much time at night to write down notes and attempt to memorize the shapes of needles. Ample practical demonstrations, though. Including one in particular with exploding biscuits. He lost biscuit privileges after that. Regardless, I hope to reach the level where I can actually contribute to the things he is trying to do someday, as I appreciate it all the more now that I know some of the theory behind it.)

We were ambushed by a group of Rat Clan orcs, and an Owl Clan elf, who had been waiting off the main road, presumably for Caedic troops to pass. The two of us were vastly outnumbered—there must have been at least a dozen of them—and I managed to strike down four before they were in turn ambushed by a Caedic patrol that had been tracking them. I suppose that was the first time my life was saved by the pure luck of coincidence, although I did not consider this at the time, as I had not taken any overly threatening wounds during the fight.

Second Lieutenant Venus Tarquin, who had led the patrol, informed us of the situation as we made our way back towards the camp of the 8th—the Unbroken. In recent months, rebel activity in Altae had increased dramatically, to the point in which our journey would be interrupted by more than just an ambush. Shortly past Cloudfall, there was a pass spanned by a single bridge, which had recently been destroyed by Salamander Clan rebels. The journey around the pass would take more than a week, and repairs would be about finished in that timeframe. We were welcome to spend our time waiting at Cloudfall, or we could speak with Captain Piso about whether or not the 8th could use two extra pairs of hands for the interim. I was eager to volunteer my services, and Talvus agreed, and so we settled in with the Unbroken in the converted Raven village in which they had made their camp.

I delivered the papers that you had left us with to Captain Piso, and Second Lieutenant Tarquin informed him of our situation. Talvus and I offered our services, and Captain Piso said that the unit could always use another two good soldiers, especially a mage. Then he dismissed Talvus, but asked me to stay. He looked at the papers again. Then he said: “Strell. Your family had some sort of connection to the recent heresy, is that correct?”

I told him yes, that I had been close friends with one of the daughters of the main family.

He said that he had very little access to information, to that sort of news from the Capital, and that he would like to know any details, if I had them. There was not much I could say; I told him that I did not know any details until the night that the Tandus family planned to escape.

“To break out the one that was imprisoned, is that correct?” he said.

It was, yet I knew only where to find Peia because we’d hidden in alleyways together all throughout our childhood. I told him such.

“Do you know anything more about the original heresy that initiated the situation?” he asked. “Anything more about what was actually found to incriminate Scaevola Tandus? Before the whole…breakout situation?”

“I knew that he was convicted of necromancy,” I said.

And there Captain Piso’s interest seemed to end. “I imagine you’ve had to deal with quite an uphill climb with that mark on your record,” he said.

“I am loyal to the Empire and I have always been willing to spill the blood of our enemies to prove it,” I told him. “I have spent the last two and a half years fighting beside those who have understood that.”

He dismissed me.

I was immediately folded into the roster of watches and patrols, and had patrol with Corporal Dante Maxim and Corporal Specialist Marcus Tyrol the next morning. Corporal Maxim was also fairly new to the 8th, being the sole survivor of an ambush by the Heretic Raven that wiped out the 22nd only a few months prior, but he and Corporal Tyrol were already fast friends, so I followed behind them and did not interject myself in their banter. The patrol proceeded uneventfully until we stumbled across the still-warm corpse of a Caedic guard. Corporal Maxim was the one who put it together in the moments that followed: the wounds of the guard were too eccentric to belong to warriors of any one clan, and we were near the route of a supply wagon that was expected to arrive today. In fact, the route had been changed, in secret, at the last minute, as prior supply trains had been ambushed, yet somehow the Heretic Raven and their company had no trouble finding it.

Fearing the numbers of the enemy, we sent Corporal Tyrol to run to the nearby Stag Clan warcamp to muster the Stag Clan loyalists, while Maxim and I vaulted over the slope and into the battle to buy time. Sure enough, the Caedic guards were outnumbered: eight of them to ten of the Heretic Raven’s warriors. It was not just numbers determining this battle; the guards were vastly outclassed, from what could be gathered of the smoke and screams. Corporal Maxim and I charged towards the fray. A woman-elf with pale skin, dark hair, and a large scythe, Anye the Huntress of the Wolf Clan, called out something to alert the others of our presence, then disappeared into the smoke. Another elf, blonde, his face covered in black warpaint—the Black Stag, a traitor of the Stag Clan—turned to hold us off while Anye tried to attack us from behind. Their mage was throwing fireballs around; one of which hit me, another that I dodged. Corporal Maxim and I held the two warriors with relative ease. Then the moment the fight seemed to be turning, the Anye the Huntress disappeared back into the smoke, and the Heretic Raven themselves, distinguished by the scar across their forehead and the left arm of a Caedic uniform jacket sewn into their Highland war garb, stepped forward to take her place.

They were a formidable foe; combining both Caedic footwork with Highland two-bladed style. Corporal Maxim and I fought them together, as Corporal Tyrol and the Stag Clan forces appeared over the hill and charged into the melee. The Heretic Raven wasn’t fighting to kill, they were fighting defensively, covering the retreat of their people. The Stag Clan loyalists turned the tide of the engagement, as the rebels were then vastly outnumbered; although they focused on the traitor of their tribe, killing him and allowing the others to escape. The Heretic Raven slit Corporal Maxim’s throat before retreating, and I stayed back to stop the bleeding and stabilize him rather than continue the fight into the woods. The supply train was not damaged, so we loaded the wounded onto the wagon and proceeded as quickly as possible back to camp, where proper healing could be distributed. Corporal Tyrol and I delivered the report, as Maxim was mostly unconscious, and then I spent the rest of the afternoon with the Stag Clan warriors, attempting to learn more about their fighting style and seeing what I could pick up of their language. The question of how the Heretic Raven managed to find the new supply route was unanswered and thus somewhat upsetting to the camp, but the supplies had been properly delivered, so it was not dwelled upon.

Next came the animal attacks. A patrol came back attacked by wolves; and a bear wandered into the center of our camp during breakfast and attacked myself, Corporal Maxim, and Lieutenant Sorus as we exited the dining building. Upon killing the bear, its conjured nature was revealed. Recalling ravens that I had seen both during the initial ambush along the road as well as at the outskirts of camp two days prior, I suggested that conjured animals might be spying on us, which could perhaps explain how the new supply route was known to the Heretic Raven. As such, Corporal Tyrol, Corporal Maxim, and I decided to stop during our patrol at the Stag Clan camp, to ask War-Leader Tairn of the Stag Clan if Highland Shamans had such abilities. Tairn was neither able to confirm nor refute my theory, so we decided to bring it up to the arcanists when we returned to Unbroken, as this was still the best explanation we had for the increasing ambushes. We continued on the patrol. Tyrol spotted some rabbits, and proposed we pause for some fun: he’d been taught basic augury before he dropped out of the academy, and offered to read our fortunes. He read mine first: in the entrails, a troubled event from my childhood, and death in the past; nothing that I didn’t already know. In the heart, fragile, which turned frustratingly accurate, as I ended up unconscious for one reason or another (most often that reason the injury from the foundry acting up) in or after every fight I engaged in since. Success, power, and upward climb for the future, not that I put much stake in it. For Maxim: in the past, humble origins, high ambitions; in the present, strong, powerful, respected among peers, and oh, owes Tyrol twelve silvers from when he lost that bet; and then the rabbit had no liver. There was no future. Maybe you just found a fucked up rabbit, Dante said.

We did not have much time to dwell, as we were immediately attacked by wolves. Luckily, I had been fighting wolves of the conjured variety for nearly a month, as I had grown bored with merely repeating my forms, and had convinced Talvus to materialize various fighting companions in the evenings of our travels. We found most interesting the fact that the corpses of these wolves did not disappear, which meant that if this was a planned attack and not unfortunate happenstance, it was by those who could control animals, not merely create magical constructs of them. We hurried back to camp to report the incident.

That had been the first clue. The biggest one. And I missed it.

When we returned, the camp was abuzz with the news that Caedic forces had discovered the hideaway of Rat Clan, one of the largest remaining holdouts of rebels. Captain Piso, with knowledge of my prior experience, engaged me to design the plan of assault; Corporal Maxim was to assist with the planning and the assignment of men; and Second Lieutenant Tarquin was to oversee the both of us and provide guidance if necessary, and make all final calls. I immediately had the following idea, for I had been working with Talvus to reverse-engineer the arcanum cannons from the battle at the Surrian front: he had been stuck upon the fact that the the burned out cartridges with a repeating rune pattern would have contained more magical energy than is stable to force into an object, and I suggested that perhaps the design was not to contain then release the energy into a spell, but only to contain, then a physical destruction of the runic pattern could release all of the energy at once, as an explosive. As such, Talvus was able to develop a delayed explosive stick, one which contained power comparable to the fireballs that had been shot, which would be released within about six or seven seconds of the destruction of the runes. The plan that I submitted to Second Lieutenant Tarquin was the tactical usage of these delayed explosives, sent in on invisible runners to the barracks of the hideaway as the Rat Clan warriors slept, then with our Caedic forces waiting by the entranceways to slaughter the disoriented survivors as they were smoked out.