#not richard dawkins though

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

We need the obnoxious atheists back. I know they engineered their own destruction by being annoying and pretentious, but it has become apparent how essential to the ecosystem they were. The religious fanatics have become too bold without their natural predators. Jesus wojaks would have been torn to shreds in 2011.

#jesus#wojaks#christianity#religion#atheism#fundamentalism#us politics#not richard dawkins though#he can choke

14K notes

·

View notes

Text

Started reading The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins, which seems to be obligatory reading for any biologist.

I love how, as it is a book first published in 1976 in a field that has rapidly evolved since then, it starts with many forwards and comes with footnotes addressing the many criticisms and new research that has come since. I feel as if I were reading a Tumblr post with repeated clarifications from bad faith readings, or a list of terms and conditions. Science is self-correcting and humans are subjective.

One of the many notes he addresses is the title itself. While the word "selfish" has too many negative connotations, I would argue the grief over people only reading the title/first chapter and misunderstandings and further clarifications needed is worth it for the punchier title. I think most biologist students understand selfish to mean self-perpetuating. He makes a good argument regardless.

There are some publications that came out after that have since corrected/clarified many of the points in the book, so I need to read those too.

#personal#this is the era of me finishing all of those books i bought i just know it#and before anyone comments:#YES I know Richard Dawkins is a cringe atheist#richard 'i dont need to read the quaran to criticize it' dawkins#and I KNOW the 'We Are All Africans' meme shirt#(even though the idea of all humans originating in Africa has had some substantial challenges recently)#i really hope people don't think of me as someone who doesn't critically examine what she reads and who wrote jt#i passed *IB English* okay i have credentials

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

@incorrectclassicbookquotes Hi! 😁

It could be argued that it's a bit to the philosophy side, but wine used to be a living thing, and still is a mixture of chemicals and other stuff. Drinking water is also a mixture of chemicals (mostly H2O) and some solids! Humans, like all biological things, are also mixtures, just one that functions in a choreograph (life).

What we are NOT affected by, NEVER WILL, are the laws of electromagnetisms. Those principles operate at much, much smaller and SIMPLER scales than humans in their societies. The further one moves away from the simple laws of math and physics, the more complex things get, and by the time we get to behaviors of living things, there are simply too many variables that we cannot account for in order for us to SIMPLY calculate our (or anyone else's) behaviors. Humans, on top of that, has added on extra layers of cultures and societies.

It's not as if the scientific process is "fundamentally" incompatible with studies of cultures and societies. It's simply that there are too many variables that we cannot all know and account for. Behaviors are already things that animals have evolved in order to add confusion in favor of their survivals, so to say, and humans just have the most amount of cultures out of all animals, and by far so, arguably making us far more unpredictable.

So, I guess you can take away, that as a living thing, an animal with behaviors, and a human animal with cultures and metaphysically-thinking brains, we are NEVER TO BE "EXPECTED" to behave in the same way as a magnet does.

Thought of this while driving

Transphobes: If God wanted water to be turned into wine He would have made it wine to begin with.

Jesus about to perform His first miracle:

#i do give richard dawkins the credit for pointing out that physics are in fact the SIMPLEST of the laws.#even though it may be “harder” for us bc our brains primarily evolved in “live in a society” settings. NOT a “do maths” setting.#math and sciences are more like all the other cool extensions. they are simpler laws. they just come to us a lil less “naturally”.

81 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey there—this is completely spontaneous on my part, but I just saw your post from a few hours ago about how good the SW fandom used to be, and, dunno, I just wanted to say that I appreciate you. Your SW analyses were always so interesting to me, especially when you got into a debate with someone, because of how you backed your arguments up with evidence. I wish I could write rhetoric like you do. Anyways, you're especially cool to me because you're French and I've got French citizenship from my mom (though I grew up in the States), and despite not being Jewish, you've been really, really kind to us. So thanks for everything—the lengthy, passionate, convincing SW posts that got me through the pandemic, the interesting religious takes (I vaguely remember you going off on someone who said that religion was irrelevant in the modern world, arguing about the impossible-to-understate role it has had in the history of humanity, including in the present day—which, to a history and IR fan who'd gotten used to the sight of anti-religious takes because it was rebellious and trendy and cute, was like a breath of fresh air), and even now, your words since October 7th. I don't know if I ever reblogged or even liked a post of yours, I'm more likely to take a screenshot and put it in a folder on my desktop, but I just wanted to let you know of the impact that you've had in my life. 💛

Awww, it's so cool to find out about people who liked my stuff even if they never said! Idk how to explain why it makes me so happy but it's like it adds more to the whole experience as I look back, it's one more piece of the full picture that I'll never have. Like finding a new detail in a familiar setting and going 'oh! that was there all along? :D'

What was it about my SW stuff that you liked? the constant ranting and raving about the Jedi or the fawning over Obi-Wan? xD (And yes, yes I *did* get into a row with antitheists because I vented about being frustrated with Richard Dawkins' worldview lol. I don't think it really went anywhere.)

I'm glad reading my posts was ever comforting to you. I constantly want to be saying more since October 7th, but I really think using the internet as a battleground would be spectacularly unwise in my case. I've always tried to only argue my opinions from a position of complete confidence and thorough knowledge of all the facts, and that's a lot easier to do with a nerdy fictional universe that's contained to easily accessible media vs complex current global events. I can be stubborn and arrogant and I always want to be right, so in order to not get sucked into propagating self-righteous misinformation and turning into exactly the type of ignorant know-it-all who'd preach to others about geopolitics they learned yesterday on twitter, I preferred to step back.

That said, there is one thing I can and always will say with utter confidence and full knowledge that it's right: the worldwide spike in antisemitism and the horrifying abuse all Jews have been subjected to for over a year both irl and online is appalling and must be called out. The Jewish people are very close to my heart because of my family history, my upbringing and my personal faith in God and my saviour. So from one ~vaguely Jewish~ Frenchie to a vaguely French Jewish person, שׁלום and salut! 💙

Also, telling me you've taken screenshots???? of my posts???? to SAVE THEM???? ON YOUR COMPUTER????? is genuinely one of the highest compliments you could ever give me wow thank youuuuu. I hope you can still have fun going back to them from time to time 😄

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Richard Dawkins

This is a slightly edited version of the essay written to accompany the transcript of the conversation between myself, Daniel Dennett, Sam Harris and the late, much-lamented Christopher Hitchens, recorded in Christopher's flat in Washington DC in September 2007 and published in 2019 as The Four Horsemen.

Among the many topics the ‘four horsemen’ discussed in 2007 was how religion and science compared in respect of humility and hubris. Religion, for its part, stands accused of conspicuous overconfidence and sensational lack of humility. The expanding universe, the laws of physics, the fine-tuned physical constants, the laws of chemistry, the slow grind of evolution’s mills – all were set in motion so that, in the 14-billion-year fullness of time, we should come into existence. Even the constantly reiterated insistence that we are miserable offenders, born in sin, is a kind of inverted arrogance: such vanity, to presume that our moral conduct has some sort of cosmic significance, as though the Creator of the Universe wouldn’t have better things to do than tot up our black marks and our brownie points. The universe is all concerned with me. Is that not the arrogance that passeth all understanding?

Carl Sagan, in Pale Blue Dot, makes the exculpatory point that our distant ancestors could scarcely escape such cosmic narcissism. With no roof over their heads and no artificial light, they nightly watched the stars wheeling overhead. And what was at the centre of the wheel? The exact location of the observer, of course. No wonder they thought the universe was ‘all about me’. In the other sense of ‘about’, it did indeed revolve ‘about me’. ‘I’ was the epicentre of the cosmos. But that excuse, if it is one, evaporated with Copernicus and Galileo.

Turning, then, to theologians’ overconfidence, admittedly few quite reach the heights scaled by the seventeenth-century archbishop James Ussher, who was so sure of his chronology that he gave the origin of the universe a precise date: 22 October, 4004 bc. Not 21 or 23 October but precisely on the evening of 22 October. Not September or November but definitely, with the immense authority of the Church, October. Not 4003 or 4005, not ‘somewhere around the fourth or fifth millennium bc’ but, no doubt about it, 4004 bc. Others, as I said, are not quite so precise about it, but it is characteristic of theologians that they just make stuff up. Make it up with liberal abandon and force it, with a presumed limitless authority, upon others, sometimes – at least in former times and still today in Islamic theocracies – on pain of torture and death.

Such arbitrary precision shows itself, too, in the bossy rules for living that religious leaders impose on their followers. And when it comes to control-freakery, Islam is way out ahead, in a class of its own. Here are some choice examples from the Concise Commandments of Islam handed down by Ayatollah Ozma Sayyed Mohammad Reda Musavi Golpaygani, a respected Iranian ‘scholar’. Concerning the wet-nursing of babies, alone, there are no fewer than twenty-three minutely specified rules, translated as ‘Issues’. Here’s the first of them, Issue 547. The rest are equally precise, equally bossy, and equally devoid of apparent rationale:

If a woman wet-nurses a child, in accordance to the conditions to be stated in Issue 560, the father of that child cannot marry the woman’s daughters, nor can he marry the daughters of the husband whom the milk belongs to, even his wet-nurse daughters, but it is permissible for him to marry the wet-nurse daughters of the woman . . . [and it goes on].

Here’s another example from the wet-nursing department, Issue 553:

If the wife of a man’s father wet-nurses a girl with his father’s milk, then the man cannot marry that girl.

‘Father’s milk’? What? I suppose in a culture where a woman is the property of her husband, ‘father’s milk’ is not as weird as it sounds to us.

Issue 555 is similarly puzzling, this time about ‘brother’s milk’:

A man cannot marry a girl who has been wet-nursed by his sister or his brother’s wife with his brother’s milk.

I don’t know the origin of this creepy obsession with wet-nursing, but it is not without its scriptural basis:

When the Qur’aan was first revealed, the number of breast-feedings that would make a child a relative (mahram) was ten, then this was abrogated and replaced with the number of five which is well-known.[1]

That was part of the reply from another ‘scholar’ to the following recent cri de coeur from a (pardonably) confused woman on social media:

I breastfed my brother-in-law’s son for a month, and my son was breastfed by my brother-in-law’s wife. I have a daughter and a son who are older than the child who was breastfed by my brother-in-law’s wife, and she also had two children before the child of hers whom I breastfed. I hope that you can describe the kind of breastfeeding that makes the child a mahram and the rulings that apply to the rest of the siblings? Thank you very much.

The precision of ‘five’ breast feedings is typical of this kind of religious control-freakery. It surfaced bizarrely in a 2007 fatwa issued by Dr Izzat Atiyya, a lecturer at Al-Azhar University in Cairo, who was concerned about the prohibition against male and female colleagues being alone together and came up with an ingenious solution. The female colleague should feed her male colleague ‘directly from her breast’ at least five times. This would make them ‘relatives’ and thereby enable them to be alone together at work. Note that four times would not suffice. He apparently wasn’t joking at the time, although he did retract his fatwa after the outcry it provoked. How can people bear to live their lives bound by such insanely specific yet manifestly pointless rules?

With some relief, perhaps, we turn to science. Science is often accused of arrogantly claiming to know everything, but the barb is capaciously wide of the mark. Scientists love not knowing the answer, because it gives us something to do, something to think about. We loudly assert ignorance, in a gleeful proclamation of what needs to be done.

How did life begin? I don’t know, nobody knows, we wish we did, and we eagerly exchange hypotheses, together with suggestions for how to investigate them. What caused the apocalyptic mass extinction at the end of the Permian period, a quarter of a billion years ago? We don’t know, but we have some interesting hypotheses to think about. What did the common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees look like? We don’t know, but we do know a bit about it. We know the continent on which it lived (Africa, as Darwin guessed), and molecular evidence tells us roughly when (between 6 million and 8 million years ago). What is dark matter? We don’t know, and a substantial fraction of the physics community would dearly like to.

Ignorance, to a scientist, is an itch that begs to be pleasurably scratched. Ignorance, if you are a theologian, is something to be washed away by shamelessly making something up. If you are an authority figure like the Pope, you might do it by thinking privately to yourself and waiting for an answer to pop into your head – which you then proclaim as a ‘revelation’. Or you might do it by ‘interpreting’ a Bronze Age text whose author was even more ignorant than you are.

Popes can promulgate their private opinions as ‘dogma’, but only if those opinions have the backing of a substantial number of Catholics through history: long tradition of belief in a proposition is, somewhat mysteriously to a scientific mind, regarded as evidence for the truth of that proposition. In 1950, Pope Pius XII (unkindly known as ‘Hitler’s Pope’) promulgated the dogma that Jesus’ mother Mary, on her death, was bodily – i.e. not merely spiritually – lifted up into heaven. ‘Bodily’ means that if you’d looked in her grave, you’d have found it empty. The Pope’s reasoning had absolutely nothing to do with evidence. He cited 1 Corinthians 15:54: ‘then shall be brought to pass the saying that is written, Death is swallowed up in victory’. The saying makes no mention of Mary. There is not the smallest reason to suppose the author of the epistle had Mary in mind. We see again the typical theological trick of taking a text and ‘interpreting’ it in a way that just might have some vague, symbolic, hand-waving connection with something else. Presumably, too, like so many religious beliefs, Pius XII’s dogma was at least partly based on a feeling of what would be fitting for one so holy as Mary. But the Pope’s main motivation, according to Dr Kenneth Howell, director of the John Henry Cardinal Newman Institute of Catholic Thought, University of Illinois, came from a different meaning of what was fitting. The world of 1950 was recovering from the devastation of the Second World War and desperately needed the balm of a healing message. Howell quotes the Pope’s words, then gives his own interpretation:

Pius XII clearly expresses his hope that meditation on Mary’s assumption will lead the faithful to a greater awareness of our common dignity as the human family. . . . What would impel human beings to keep their eyes fixed on their supernatural end and to desire the salvation of their fellow human beings? Mary’s assumption was a reminder of, and impetus toward, greater respect for humanity because the Assumption cannot be separated from the rest of Mary’s earthly life.

It’s fascinating to see how the theological mind works: in particular, the lack of interest in – indeed, the contempt for – factual evidence. Never mind whether there’s any evidence that Mary was assumed bodily into heaven; it would be good for people to believe she was. It isn’t that theologians deliberately tell untruths. It’s as though they just don’t care about truth; aren’t interested in truth; don’t know what truth even means; demote truth to negligible status compared with other considerations, such as symbolic or mythic significance. And yet at the same time, Catholics are compelled to believe these made-up ‘truths’ – compelled in no uncertain terms. Even before Pius XII promulgated the Assumption as a dogma, the eighteenth-century Pope Benedict XIV declared the Assumption of Mary to be ‘a probable opinion which to deny were impious and blasphemous’. If to deny a ‘probable opinion’ is ‘impious and blasphemous’, you can imagine the penalty for denying an infallible dogma! Once again, note the brazen confidence with which religious leaders assert ‘facts’ which even they admit are supported by no historical evidence at all.

The Catholic Encyclopedia is a treasury of overconfident sophistry. Purgatory is a sort of celestial waiting room in which the dead are punished for their sins (‘purged’) before eventually being admitted to heaven. The Encyclopedia’s entry on purgatory has a long section on ‘Errors’, listing the mistaken views of heretics such as the Albigenses, Waldenses, Hussites and Apostolici, unsurprisingly joined by Martin Luther and John Calvin.[2]

The biblical evidence for the existence of purgatory is, shall we say, ‘creative’, again employing the common theological trick of vague, hand-waving analogy. For example, the Encyclopedia notes that ‘God forgave the incredulity of Moses and Aaron, but as punishment kept them from the “land of promise”’. That banishment is viewed as a kind of metaphor for purgatory. More gruesomely, when David had Uriah the Hittite killed so that he could marry Uriah’s beautiful wife, the Lord forgave him – but didn’t let him off scot-free: God killed the child of the marriage (2 Samuel 12:13–14). Hard on the innocent child, you might think. But apparently a useful metaphor for the partial punishment that is purgatory, and one not overlooked by the Encyclopedia’s authors.

The section of the purgatory entry called ‘Proofs’ is interesting because it purports to use a form of logic. Here’s how the argument goes. If the dead went straight to heaven, there’d be no point in our praying for their souls. And we do pray for their souls, don’t we? Therefore it must follow that they don’t go straight to heaven. Therefore there must be purgatory. QED. Are professors of theology really paid to do this kind of thing?

Enough; let’s turn again to science. Scientists know when they don’t know the answer. But they also know when they do, and they shouldn’t be coy about proclaiming it. It’s not hubristic to state known facts when the evidence is secure. Yes, yes, philosophers of science tell us a fact is no more than a hypothesis which may one day be falsified but which has so far withstood strenuous attempts to do so. Let us by all means pay lip service to that incantation, while muttering, in homage to Galileo’s muttered eppur si muove, the sensible words of Stephen Jay Gould:

In science, ‘fact’ can only mean ‘confirmed to such a degree that it would be perverse to withhold provisional assent.’ I suppose that apples might start to rise tomorrow, but the possibility does not merit equal time in physics classrooms.[3]

Facts in this sense include the following, and not one of them owes anything whatsoever to the many millions of hours devoted to theological ratiocination. The universe began between 13 billion and 14 billion years ago. The sun, and the planets orbiting it, including ours, condensed out of a rotating disk of gas, dust and debris about 4.5 billion years ago. The map of the world changes as the tens of millions of years go by. We know the approximate shape of the continents and where they were at any named time in geological history. And we can project ahead and draw the map of the world as it will change in the future. We know how different the constellations in the sky would have appeared to our ancestors and how they will appear to our descendants.

Matter in the universe is non-randomly distributed in discrete bodies, many of them rotating, each on its own axis, and many of them in elliptical orbit around other such bodies according to mathematical laws which enable us to predict, to the exact second, when notable events such as eclipses and transits will occur. These bodies – stars, planets, planetesimals, knobbly chunks of rock, etc. – are themselves clustered in galaxies, many billions of them, separated by distances orders of magnitude larger than the (already very large) spacing of (again, many billions of) stars within galaxies.

Matter is composed of atoms, and there is a finite number of types of atoms – the hundred or so elements. We know the mass of each of these elemental atoms, and we know why any one element can have more than one isotope with slightly different mass. Chemists have a huge body of knowledge about how and why the elements combine in molecules. In living cells, molecules can be extremely large, constructed of thousands of atoms in precise, and exactly known, spatial relation to one another. The methods by which the exact structures of these macromolecules are discovered are wonderfully ingenious, involving meticulous measurements on the scattering of X-rays beamed through crystals. Among the macromolecules fathomed by this method is DNA, the universal genetic molecule. The strictly digital code by which DNA influences the shape and nature of proteins – another family of macromolecules which are the elegantly honed machine-tools of life – is exactly known in every detail. The ways in which those proteins influence the behaviour of cells in developing embryos, and hence influence the form and functioning of all living things, is work in progress: a great deal is known; much challengingly remains to be learned.

For any particular gene in any individual animal, we can write down the exact sequence of DNA code letters in the gene. This means we can count, with total precision, the number of single-letter discrepancies between two individuals. This is a serviceable measure of how long ago their common ancestor lived. This works for comparisons within a species – between you and Barack Obama, for instance. And it works for comparisons of different species – between you and an aardvark, say. Again, you can count the discrepancies exactly. There are just more discrepancies the further back in time the shared ancestor lived. Such precision lifts the spirit and justifies pride in our species, Homo sapiens. For once, and without hubris, Linnaeus’s specific name seems warranted.

Hubris is unjustified pride. Pride can be justified, and science does so in spades. So does Beethoven, so do Shakespeare, Michelangelo, Christopher Wren. So do the engineers who built the giant telescopes in Hawaii and in the Canary Islands, the giant radio telescopes and very large arrays that stare sightless into the southern sky; or the Hubble orbiting telescope and the spacecraft that launched it. The engineering feats deep underground at CERN, combining monumental size with minutely accurate tolerances of measurement, literally moved me to tears when I was shown around. The engineering, the mathematics, the physics, in the Rosetta mission that successfully soft-landed a robot vehicle on the tiny target of a comet also made me proud to be human. Modified versions of the same technology may one day save our planet by enabling us to divert a dangerous comet like the one that killed the dinosaurs.

Who does not feel a swelling of human pride when they hear about the LIGO instruments which, synchronously in Louisiana and Washington State, detected gravitation waves whose amplitude would be dwarfed by a single proton? This feat of measurement, with its profound significance for cosmology, is equivalent to measuring the distance from Earth to the star Proxima Centauri to an accuracy of one human hair’s breadth.

Comparable accuracy is achieved in experimental tests of quantum theory. And here there is a revealing mismatch between our human capacity to demonstrate, with invincible conviction, the predictions of a theory experimentally and our capacity to visualize the theory itself. Our brains evolved to understand the movement of buffalo-sized objects at lion speeds in the moderately scaled spaces afforded by the African savannah. Evolution didn’t equip us to deal intuitively with what happens to objects when they move at Einsteinian speeds through Einsteinian spaces, or with the sheer weirdness of objects too small to deserve the name ‘object’ at all. Yet somehow the emergent power of our evolved brains has enabled us to develop the crystalline edifice of mathematics by which we accurately predict the behaviour of entities that lie under the radar of our intuitive comprehension. This, too, makes me proud to be human, although to my regret I am not among the mathematically gifted of my species.

Less rarefied but still proud-making is the advanced, and continually advancing, technology that surrounds us in our everyday lives. Your smartphone, your laptop computer, the satnav in your car and the satellites that feed it, your car itself, the giant airliner that can loft not just its own weight plus passengers and cargo but also the 120 tons of fuel it ekes out over a thirteen-hour journey of seven thousand miles.

Less familiar, but destined to become more so, is 3D printing. A computer ‘prints’ a solid object, say a chess bishop, by depositing a sequence of layers, a process radically and interestingly different from the biological version of ‘3D printing’ which is embryology. A 3D printer can make an exact copy of an existing object. One technique is to feed the computer a series of photographs of the object to be copied, taken from all different angles. The computer does the formidably complicated mathematics to synthesize the specification of the solid shape by integrating the angular views. There may be life forms in the universe that make their children in this body-scanning kind of way, but our own reproduction is instructively different. This, incidentally, is why almost all biology textbooks are seriously wrong when they describe DNA as a ‘blueprint’ for life. DNA may be a blueprint for protein, but it is not a blueprint for a baby. It’s more like a recipe or a computer program.

We are not arrogant, not hubristic, to celebrate the sheer bulk and detail of what we know through science. We are simply telling the honest and irrefutable truth. Also honest is the frank admission of how much we don’t yet know – how much more work remains to be done. That is the very antithesis of hubristic arrogance. Science combines a massive contribution, in volume and detail, of what we do know with humility in proclaiming what we don’t. Religion, by embarrassing contrast, has contributed literally zero to what we know, combined with huge hubristic confidence in the alleged facts it has simply made up.

But I want to suggest a further and less obvious point about the contrast of religion with atheism. I want to argue that the atheistic worldview has an unsung virtue of intellectual courage. Why is there something rather than nothing? Our physicist colleague Lawrence Krauss, in his book A Universe from Nothing,[4] controversially suggests that, for quantum-theoretic reasons, Nothing (the capital letter is deliberate) is unstable. Just as matter and antimatter annihilate each other to make Nothing, so the reverse can happen. A random quantum fluctuation causes matter and antimatter to spring spontaneously out of Nothing. Krauss’s critics largely focus on the definition of Nothing. His version may not be what everybody understands by nothing, but at least it is supremely simple – as simple it must be, if it is to satisfy us as the base of a ‘crane’ explanation (Dan Dennett’s phrase), such as cosmic inflation or evolution. It is simple compared to the world that followed from it by largely understood processes: the big bang, inflation, galaxy formation, star formation, element formation in the interior of stars, supernova explosions blasting the elements into space, condensation of element-rich dust clouds into rocky planets such as Earth, the laws of chemistry by which, on this planet at least, the first self-replicating molecule arose, then evolution by natural selection and the whole of biology which is now, at least in principle, understood.

Why did I speak of intellectual courage? Because the human mind, including my own, rebels emotionally against the idea that something as complex as life, and the rest of the expanding universe, could have ‘just happened’. It takes intellectual courage to kick yourself out of your emotional incredulity and persuade yourself that there is no other rational choice. Emotion screams: ‘No, it’s too much to believe! You are trying to tell me the entire universe, including me and the trees and the Great Barrier Reef and the Andromeda Galaxy and a tardigrade’s finger, all came about by mindless atomic collisions, no supervisor, no architect? You cannot be serious. All this complexity and glory stemmed from Nothing and a random quantum fluctuation? Give me a break.’ Reason quietly and soberly replies: ‘Yes. Most of the steps in the chain are well understood, although until recently they weren’t. In the case of the biological steps, they’ve been understood since 1859. But more important, even if we never understand all the steps, nothing can change the principle that, however improbable the entity you are trying to explain, postulating a creator god doesn’t help you, because the god would itself need exactly the same kind of explanation.’ However difficult it may be to explain the origin of simplicity, the spontaneous arising of complexity is, by definition, more improbable. And a creative intelligence capable of designing a universe would have to be supremely improbable and supremely in need of explanation in its own right. However improbable the naturalistic answer to the riddle of existence, the theistic alternative is even more so. But it needs a courageous leap of reason to accept the conclusion.

This is what I meant when I said the atheistic worldview requires intellectual courage. It requires moral courage, too. As an atheist, you abandon your imaginary friend, you forgo the comforting props of a celestial father figure to bail you out of trouble. You are going to die, and you’ll never see your dead loved ones again. There’s no holy book to tell you what to do, tell you what’s right or wrong. You are an intellectual adult. You must face up to life, to moral decisions. But there is dignity in that grown-up courage. You stand tall and face into the keen wind of reality. You have company: warm, human arms around you, and a legacy of culture which has built up not only scientific knowledge and the material comforts that applied science brings but also art, music, the rule of law, and civilized discourse on morals. Morality and standards for life can be built up by intelligent design – design by real, intelligent humans who actually exist. Atheists have the intellectual courage to accept reality for what it is: wonderfully and shockingly explicable. As an atheist, you have the moral courage to live to the full the only life you’re ever going to get: to fully inhabit reality, rejoice in it, and do your best finally to leave it better than you found it.

-

[1] https://islamqa.info/en/27280 [2] http://www.catholic.org/encyclopedia/view.php?id=9745 [3] ‘Evolution as fact and theory’. [4] For which I wrote an afterword.

#Richard Dawkins#atheism#moral courage#intellectual courage#intellectual honesty#science#religion is a mental illness

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good morning. 🦋🦋🦋

1 February 2025

It's Saturday all over again. It feels like we just had one, as if the world keeps spinning in circles. When I was a child, during the days of John Glenn, I would occasionally dream of being an astronaut. In fact, in my dreams, I was launched into space as the youngest astronaut ever. Why would they do that? Well, because it was me—I was special and a hero in my own mind. I want to note that I've never actually mentioned those dreams to anybody before, so you're the first to know. I only had the hero complex while sleeping, though. There are people today who have delusions of grandeur even when they are awake. You know who they are.

"A delusion is something that people believe in despite a total lack of evidence." - Richard Dawkins

"You cannot reason with delusion." - Rachel Lindsay

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the last few weeks I've gotten some interesting questions and read some interesting things about the atheist perspective and, being the kind of person I am, I thought other people might find some of my thoughts and answers interesting. This is kind of a LONG RANT (TM), but it's a bit more scattershot than usual.

Fair warning, though, this is written entirely from the perspective of an atheist and I haven't softened anything to make it sound better to religious people, read at your own risk. In no particular order, here goes.

FAITH VS RELIGION

First off, I want to make a distinction between faith and religion because it's important to understanding the rest of this. There's some overlap, but for the most part, religion is an organized system of belief while faith is a belief internal to a single person.

The most important thing I want you to recognize from this is that an atheist may not have religion (after all, what's there to organize around?), but I have as much faith in what I believe as any religious person. An agnostic, someone who says "I do believe in God" is a person without faith, but an atheist, a person who says "I believe there is no God" is a person of faith, though not a person of religion.

Keep all of that in mind when reading the rest of this.

WHAT DOES RELIGION LOOK LIKE FROM OUTSIDE?

The specific question I got, from someone who's on their own journey of faith and was curious, was "does any religion look more or less ridiculous to an atheist?" and the short answer is "no". To be perfectly honest, all metaphysical beliefs and all religious rituals and chants look fairly ridiculous from my point of view, but none of them are particularly more ridiculous than any others.

To me, Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Paganism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Mormonism, and all of the other thousands or even millions of different religious systems out there are almost indistinguishable to me. Once you take away the specific symbols and trappings, they all come down to the same basic thing. And, sure, they believe different metaphysical things, but I assure you that your familiar metaphysical belief is no less impossible, insane, or ridiculous from the outside than those other people's strange and unfamiliar metaphysical belief.

The slightly longer answer, however, is that there is one form of religion that does look more ridiculous to me as an atheist. It's the religion that demands things of people that don't follow it. Look, you can believe whatever you want and practice whatever you want in your own mind, we all have a right to our own thoughts and beliefs, but it takes a special kind of crazy to think, despite the fact that you can't prove any of these things, that your personal beliefs are so important that they should be forced upon other people.

So, yeah, don't worry about whether this belief or that belief is too crazy, they're all crazy to me, but no more than any other. The only time you've crossed the line is when you become so crazy that you decide you're the universe's main character and everyone else has to do what you say.

THE ANGRY ATHEIST

We've all met that guy, heck, I've been that guy, the angry atheist who loves getting in "debates" and discussions about religion, the guy who sounds like Richard Dawkins or Bill Maher.

I'll level with you, there is pretty much no atheist who hasn't, at some point, been the angry atheist. You probably would be the angry "insert-religion-here" too if you lived in a society where your system of belief wasn't just a minority or disrespected, but actively despised by most of the people around you.

If you're not atheist, I don't expect you to understand the depth of it because they don't do it to you, but lots of religious people are absolutely awful to atheists, and I have a particular point of comparison because I'm also Jewish (not religiously, but that rarely matters). People, Christians mostly where I live and where I grew up, are so much more accepting of a Jew or any other religious minority than an atheist, and I think it's because a Jew doesn't threaten the very idea of religion. Ultimately, a Jew believes in something metaphysical, and that's enough; an atheist rejects the very concept. You have no idea the number of times I've heard religious people tell me that other religions are wrong, but an atheist is worse because no one can be moral without religion (more on that later). No one cared that I was a Jew growing up, at least, not that much, but multiple times in grade school I would have my entire class spend upwards of a half hour trying to convert me, the atheist; all of them against me. You either get good at arguing and debating or you crumble.

Almost every atheist, really as a matter of survival, will become the angry atheist for at least some period as a way to survive this. Going on the offense is a really good way to throw the hate off balance and it can feel good to push hate right back. It took me a while to get past the angry atheist phase and part of it, at least for me, was finding Christopher Hitchens who, while also an obnoxious atheist like Dawkins and Maher, rooted his critique in a powerful morality. These days I'm probably a good deal less obnoxious than Hitchens was, but that's where it started, with an example that wasn't just about "beating" the religious.

So, while I disagree with the angry atheist and the way they approach society, and, if I'm in a position to do so, I'll try to guide them out of it if only because anger is even more toxic for the person experiencing it than it is for the target, I understand it and I certainly don't blame them. If you're a religious person and you encounter this angry atheist, I'd only ask that you treat them with a bit of sympathy; society is regularly far worse to them than they are to you even if you never get to see it.

SOCIAL NORMS

In a bit of a line with the previous topic, you should also realize how heavily societal norms and standards of politeness are slanted toward religious people. To give you an example of this, take the following:

I've been in situations where I've had some kind of personal loss and someone will say "I'm praying for you", "they're in heaven now", or something to that effect. And, look, it's not the kind of social faux pas that's bad enough for me to call out and make a scene about, but why would someone say that to someone who they know is non-religious? I know the intent behind it, but prayers literally do not mean anything to me, heaven doesn't exist to me, and people know that.

Ultimately, it may not be meant that way, but it really comes across as a power move. The atheist may be the one who's suffered a loss and is grieving, but the religious person still has the societal power to force the situation to conform to their beliefs. If an atheist calls them out on it and/or rejects their prayers or well-wishes, then they become the bad guy for not respecting the other person's beliefs because society values religious beliefs over those of an atheist.

And, look, I'm not saying that religious people are evil for doing this; clearly I'm friends with a good many of them and, most of the time, I can take "I'm praying for you" in exactly the way that it's meant, because it's almost always meant well. But, just as racism tends to express itself not through single, overt acts, but through hundreds of individually small actions (normally called "microaggressions"), the prejudice against atheism is similar and, just as most people committing racial microaggressions are unaware they are doing so because they live in a society where white supremacy is normalized, religious people are also mostly unaware of how what they're doing comes across because religious supremacy is so ingrained in our society.

If you've done this, I'm not saying this to make you feel guilty about it or even to make you stop. Like I said, I know it's meant well and, ultimately, it's not your fault; we live in a society where the atheist perspective is hidden from you so there's really been no way for you to even know how what you're saying comes across. The only thing I would ask is, in the future, if you have an atheist or atheists in your life that you consider to be friends or loved ones, they'll appreciate it if, especially in a vulnerable situation, you think just a bit more about what how what you're saying sounds to them and say something that is comforting to them and not just to you.

FINDING FAITH

Most people don't have faith. Let's start there. I've had religious and theological discussions with all kinds of people for all kinds of reasons, as much for understanding as debate or conversion, and what I can tell you is that most people never think deeply enough about what they truly believe to have actual faith. They have religion.

You see, most people are born into some kind of religious framework. Their parents start taking them to church or some kind of religious observance at an early age and the path of least resistance is to just keep doing whatever that is. Questioning religion or rocking the boat can lead to social stigma, damaged relationships, and sometimes even financial destitution, so for most people it's simply not worth doing to the point where they don't even consider it. They just go through the motions and don't worry too much about it because there's simply no good reason to.

There are some people who will still go through the difficult process of finding faith in that situation, but I've found that most people who truly have faith are the ones who have questioned and often even broken away from what they were brought up with. Specific to atheists, almost none of us were raised atheist. It wasn't a particularly difficult rejection for me because my family wasn't particularly dogmatic about it, but I wasn't raised atheist either; I figured out what I believed, I found my faith, when I started questioning all of the things that I was brought up with and all of the things that others around me believed. Ultimately, I accepted a lot of it in terms of the moral system I follow, but I rejected all of the metaphysical.

Don't get me wrong, there are plenty of people who turn to atheism for reasons like rebellion or to fit in with a (usually small) group, but most adult atheists you see out there are people who have gone through a journey and found faith; it's not a default option for the vast majority of us.

I also don't want you to think I'm saying that only atheists have faith, I've met plenty of religious people who have faith as well and it's something brilliant when you do find it (meeting such a person was also a big part me no longer being an angry atheist). The point is more that, as a percentage, far more atheists than religious people have true faith; it's easy to be religious, but why would one put up with all the problems that being atheist brings if you didn't truly believe it?

ATHEIST MORALITY

So this is the last one and it's a bit of an important one. You see, as I mentioned in the section about angry atheists, much of the prejudice against atheists I've experienced has been justified by the idea that atheists, because we reject the idea of God and the metaphysical, cannot be moral. Specifically, there is an idea in religion that morality can only come from a metaphysical source.

Now, I can't speak for all atheists here. As I mentioned before, there's nothing about atheism that lends itself to organization, so this is just me speaking. That said, I can tell you that those people are 100% wrong here, not least because many of them were genuinely awful people who used their own religion and its metaphysically justified rules as an excuse to be immoral themselves.

Personally, I consider myself to be generally Utilitarian in my moral beliefs. It's much more complicated than this, but in simple terms Utilitarianism is a belief that what maximizes the well-being, happiness, and pleasure of all people and what minimizes harm, pain, and unhappiness, is moral. One could summarize it as "the greatest good for the greatest number" if one were being particularly simplistic about it.

Why do I believe that? Simple, I live in a society and that society benefits me, I'd even say it benefits me greatly. Having studied some political theory, it's clear that societies where everyone is better off make do a better job of actually making people, even those at the top, better off and are more stable and consistent in the long run, so it makes sense that I should want to live in such a society. Ultimately, though, societies are made up of people, they're not things of their own, so a society is a reflection of the actions of the people who live in it.

In other words, if I want to live in a society that makes people (like me!) better off, I need to act in a way that makes that society more likely. Now, I obviously don't control anyone other than myself, but if I do what's right, then I can find other people who also do what's right and we can become a community. It's not guaranteed, but that's how anything worth having starts and, if we all continue this long enough, we build what we want to live in. I live my life morally because it's the only way that what I want can come about and, if I cheat, I'll know that I'm damaging the future I hope to build.

After doing this for a long time, though, one of the biggest benefits I've found, though, is that I like myself when I'm moral. That's important because I have to live with me!

No metaphysics required, my morality not only provides me with a rational (to me at least) reason to act morally, it ultimately subjects me to a judge that will see everything I do and never lapses: me. Those who are religious will say that an all-knowing God being their ultimate judge is a stronger motivation to be moral but, to quote Thomas Huxley from Evolution and Ethics, "Every day, we see firm believers in the hell of the theologians commit acts by which, as they believe when cool, they risk eternal punishment; while they hold back from those which are opposed to the sympathies of their associates."

Ultimately, I think that every system of morality is either personal or social (usually some combination of both). Even if you believe in God, gods, or other forms spirituality, none of us understand perfectly their nature or the nature of the universe, so we're all just doing what feels right to us or our community. Atheism doesn't preclude morality any more than religion guarantees it and I've found/developed a moral system that works for me without any need for the metaphysical.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

One of the things I've come to realize over the years is that the concept of atheist is truly alien to people of religion. Yes, they find other religions strange and unfamiliar, but the basic shape of the worldview makes sense to them. Atheism is alien and frightening to many.

Hopefully this gave you a bit of insight into what's going on there. If you have any other questions about atheism or the atheist experience, feel free to ask, I'm more than happy to share.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Literally why don't my stories get the love they deserve?

I want every comment, kudos, and follow that I am entitled to.

https://archiveofourown.org/works/62588794/chapters/160473235

Tweek snapped his head around and rolled his eyes. "You love it, though."

"Yeah I do." Craig admitted. "But I love it the way a battered wife loves her husband."

"You love it more than you love me..." Tweek's voice cracked, he swiped an arm around his face.

Craig swallowed hard. It's like an emotion he couldn't name was trying to run out of his soul.

"I hate being hungry and it hurts." Craig whispered, his eyes shimmered and his voice shook, he winced at the confession. "I know I keep hurting you, but if you don't just let me it will get bad..."

He lost Tweek there, and his fists clenched so hard his nails broke his skin. "YOU DON'T REALLY BELIEVE THAT!" He roared, kicking over the night stand.

Tweek stood shaking. His heart hammered against his ribs, and nausea waved through his body. He couldn't stand to listen to Craig's delusions. It made his skin crawl.

Craig covered his mouth, his breath shuddered through sobs and his eyes shut slowly.

"You're the smartest fucking person I've ever met! It's insane to hear you talk like that!" Tweek hissed.

"Tweek... I promise, baby. It happened to Bebe. It happened to my dad. It's our vices." Tears slid down Craig's cheeks. "Ghandi had sex and his niece he was in love with died." He whispered. "When we do what tempts us the most--"

"CRAIG THAT'S INSANE! You're the most ass hole atheist person I've ever fucking met! You're worse than Richard fucking Dawkins!" Tweek shouted, slapping his hands over his ears. "You aren't superstitious stop it!"

Craig's lips quivered. He ran his hand down his face. He knew he shouldn't have ever said anything.

Tweek's face crumpled. "It's so fucking useless, Craig. I'm exhausted! I wasted my whole life for something you'd never do!"

Craig shrugged. "I know. I'm not telling you I'm changing. I know what it is and what it does."

"You don't know what it does to me!" Tweek hissed.

"You don't know what it does to me, either!" Craig crossed his arms.

Tweek growled, pacing inches away from Craig, his face turning red as rage bubbled in his chest. "IT MAKES YOU A FUCKING MONSTER!" He leaned forward shaking his fists in front of his face. "It makes you selfish! It makes you crazy! It makes you sick! It makes you obsessed! It fucks up our entire fucking lives!"

"Then what's your excuse?!" Craig hissed. "Why do you pop my stash? Why do you gotta pretend to be the hero!?" He swung his legs over the bed. "You love obsessing about my disorder more than anything! More than drugs! More than fucking me!" Craig accused, emphasizing each point slicing his hand through the air.

Tweek sneered and shook his head. "Don't."

"Don't what?!" Craig bit. "Don't call you out!? Fuck you! We're doing you now!" He leaned forward to growl. "You're so fucked up yourself you're scared of what will happen when I'm not on your level!"

Tweek scoffed. He dropped his arms and glared shaking his head tightly for a few beats.

"Whatever! You manipulative piece of shit." Tweek spat through his teeth. "You are so much more fucked up than I ever was! My anxiety-- hell my Xanax habit-- is a fucking joke compared to the way you destroy yourself!"

"I know you're not addicted to Xanax." Craig said darkly narrowing his eyes. "I'm your addiction. Trying to be my hero. You thinking we could have some faggy special bond if you see me through this. If you just ignored it, maybe I would've been better a long time ago."

Craig winced. All he wanted to do was cry in Tweek's chest and let him make him eat.

"FUCK YOU, CRAIG!" Tweek bellowed, tears stung the corner of his eyes. "I swear to God, the whole time you just use it to fuck with me and make me take care of you! You don't care about anyone! I bet in your head it's all a game!"

'You're not for anyone, that's why everyone always dies. You have to let Tweek go. You're not supposed to be with him, you're supposed to lock yourself in a room and starve to death. No pills, no food, no water. Just use your will.'

Craig tensed. squeezing his eyes shut and grabbing fistfuls of his hair. "YOU HAVE NO IDEA WHAT IT'S LIKE INSIDE OF MY HEAD!" His face reddened, and his fists shook.

He felt light headed and staggered back to the bed.

Tweek's nostrils flared, and he shook his head. He wanted to pick him up and shove food down his throat. He wanted to wrap his arms around him. He wanted Craig to tell him everything that's ever made him sad. He wanted to beat up his parents, and the thing in his head.

But it felt less like holding onto the man he loved and more like propping up his corpse at this point.

"All I need to know is that it's fucking ruined your life, dude." Tweek's voice was weaker and raspy. "It's taken everything from you. You're more sick than your mom ever was... You're 33 and you have the body and bones of a 100 year old man. But you're still a little boy! You're still the sad little fourteen year old who wanted to starve until their parents loved them! You're never gonna be good enough for them! But you don't even care about the people who have never asked anything from you!"

Craig shook his head and whipped his face around, but Tweek heard the sob he tried to hide.

"And now the friend you taught how to puke is fucking dead, and you're next!" Tweek couldn't stop it, his anger was spilling out. His head told him to stop, that this wasn't sticking it to his disorder, this was emotional battery.

Craig couldn't hold it back anymore, his shoulder shook violently. Tweek wasn't sure if it was how hard he was crying, or the fact he could see every bone under his skin jutting out through his shirt that made it look so graphic.

"I wish it was me! I know." Craig was barely audible. "I know I'm poison. I know what I've done, I'm sorry, I just want to leave."

Craig shook so hard Tweek wasn't sure if it was just crying anymore. It put a pit in Tweek's stomach and made him sick and tired.

Tweek covered his mouth with his hand and tears slid down his face silently. "You're not giving me a choice." It was already too late. He basically just handed Craig a gun to shoot himself with, but his mouth wouldn't stop. "You're not going to sit there and tell me I never gave a shit about you. After everything you've put me through. After everything I've done." He felt like he was on fire and heartbroken at the same time. "You won't even fucking EAT FOR ME!" Tweek shouted, close enough for Craig to get sprayed with his spit.

Craig looked away with a hand clapped tight over his mouth.

'Shut the fuck up!' Tweek kept screaming to himself, but the anger and hatred for this stupid fucking disorder couldn't stay in his head anymore. "My whole life is watching you die but you've been gone for a long time. It's not you anymore! You're a walking talking eating disorder! It won! It beat me!" He swung around smashing his fist into the wall hard enough to leave a hole.

The wall shook and two portraits Craig had painted of Tweek smashed to the ground, shattering glass on the floor.

Craig jumped. He felt like he was 8 years old again and watching his parents scream at each other.

It felt so normal. It hurt, but it made more sense than Tweek hugging him and kissing his forehead. The devastation wasn't even from the shock. It was that it was finally happened. He finally pushed Tweek away. He was finally alone to starve to death.

Isn't that what he always wanted? Why did it completely shatter what was left of his heart?

"YOU WOULD NEVER DO THIS SHIT FOR ME!" Tweek screamed at the wall, clenching his fists.

Tweek breathed heavily. He coughed and let his breath catch up before he glanced at Craig again.

Craig's nose had started to bleed. He saw tiny black dots of ink dance around his vision. He shook pathetically curled up into a small ball.

Tweek dropped his head. He's never seen Craig look at him like that before.

Like he was scared of him.

Tweek almost took a step forward. He wanted to apologize and force him to go to a hospital. He wanted to cry in his arms, and let Craig cry in his. He wanted to go inside of his head and burn this thing alive.

#sp creek#tweek x craig#dark fic#disordered eating mention#eating disoder trigger warning#south park#tweek tweak#craig tucker#sp craig#craig x tweek#tweek

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Biological essentialism treats tapirs and rabbits, pangolins and dromedaries, as though they were triangles, rhombuses, parabolas or dodecahedrons. The rabbits that we see are wan shadows of the perfect 'idea' of rabbit, the ideal, essential, Platonic rabbit, hanging somewhere out in conceptual space along with all the perfect forms of geometry. Flesh-and-blood rabbits may vary, but their variations are always to be seen as flawed deviations from the ideal essence of rabbit.

How desperately unevolutionary that picture is! The Platonist regards any change in rabbits as a messy departure from the essential rabbit, and there will always be resistance to change - as if all real rabbits were tethered by an invisible elastic cord to the Essential Rabbit in the Sky. The evolutionary view of life is radically opposite. Descendants can depart indefinitely from the ancestral form, and each departure becomes a potential ancestor to future variants. [...]

On the 'population-thinking' evolutionary view, every animal is linked to every other animal, say rabbit to leopard, by a chain of intermediates, each so similar to the next that every link could in principle mate with its neighbours in the chain and produce fertile offspring. You can't violate the essentialist taboo more comprehensively than that. And it is not some vague thought-experiment confined to the imagination. On the evolutionary view, there really is a series of intermediate animals connecting a rabbit to a leopard, every one of whom lived and breathed, every one of whom would have been placed in exactly the same species as its immediate neighbours on either side in the long, sliding continuum. Indeed, every one of the series was the child of its neighbour on one side and the parent of its neighbour on the other. Yet the whole series constitutes a continuous bridge from rabbit to leopard - although, as we shall see later, there never was a 'rabbipard'. There are similar bridges from rabbit to wombat, from leopard to lobster, from every animal or plant to every other.

-- Richard Dawkins, The Greatest Show on Earth (2009), chapter 2

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

instagram

"Do you really mean to tell me the only reason you try to be good is to gain God's approval and reward, or to avoid his disapproval and punishment? That's not morality, that's just sucking up, apple-polishing, looking over your shoulder at the great surveillance camera in the sky, or the still small wiretap inside your head, monitoring your every move, even your every base though." - Richard Dawkins

#palestine#free palestine#free gaza#freepalastine🇵🇸#we stand with palestine#ceasefire#gaza strip#israel#gaza#usa#joe biden#president biden#biden#quotes#richard dawkins#phrases#frases#morals#morality#estados unidos#Instagram#united nations

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Return of the prodigal son, by Marc Chagall + homily

Size: 80 x 59 cm

+++

Chagall created this other version of the same biblical story:, also in 1975

64 x 47.5 cm. (25.2 x 18.7 in.) https://www.wikiart.org/en/marc-chagall/the-return-of-the-prodigal-son-1975

+++

Kenneth Tanner wrote in March 2019:

Just after Francis started his pontificate, I remember a sermon he gave at Madison Square Garden.

The Parable of the Two Sons was his text.

Francis said that God is the father waiting at the dawn of every day, pacing in the stillness of every morning of the world, scanning the horizon for all of us, waiting with a pounding heart for every lost son or lost daughter to come home. Anyway, that’s my memory of what he said. And I believe that’s exactly right.

Jesus says that when the father spots the son at a distance that he starts toward the son, hiking his robes above his knees and running at a sprint, something a man of power and wealth did not do in the ancient world; that in great humility the father throws himself on the son and kisses him—*before* any indication from the son that he is repentant or contrite or changed.

In fact, when the son begins his confession, the Father is not even listening. He’s already beckoning for the robe and the family ring, for the welcome party to start.

Yes, the younger son’s words “when he begins his speech” make plain that he knows he’s dead and has no possibility of any other kind of life, of any other kind of relationship to the father.

The son has given up the original idea, the notion that came over him in his great hunger as he slopped the pigs in the far country, of bargaining his way back into connection with his father. He simply acknowledges his fatal condition.

Capon says the son finally realizes in the embrace of the father that he can only ever be a dead son made alive again by the father’s love.

What’s clear—and this will sound very odd to far too many Christians, even though it should not—is that the father’s forgiveness is *already granted* prior to one damned word or act of contrition from the son.

The son is forgiven. Period. This is a given. This story and every other word of Jesus takes this state of affairs for granted.

Forgiveness is not dependent on the son. Forgiveness happens because the father is a Forgiver. This is simply who the father is. Mercy triumphs over judgment. Grace is unconditional.

The story of the world is contained in this story. I hope whoever preached it for you and your local church today left you breathless at the mercy of God, astonished by God’s love for every person, regardless of their reputation.

Kevin Spacey is forgiven. Stormy Daniels is forgiven. Vladimir Putin is forgiven. Jussie Smollett is forgiven. Gina Haspil is forgiven. Richard Spenser is forgiven. Kim Jong-in is forgiven. Donald Trump is forgiven. Harvey Weinstein is forgiven. Richard Dawkins is forgiven.

Everyone is already forgiven and everyone is welcome to hang out with Jesus and listen to him, to eat with him, to be embraced by him.

I hope you left church marveling at grace, knowing you are dead yet raised; that the father is speaking these words to all the mininsters of heaven about you:

“‘Quick. Bring a clean set of clothes and dress him. Put the family ring on his (her) finger and sandals on his (her) feet. Then get a grain-fed heifer and roast it. We’re going to feast! We’re going to have a wonderful time! My son (daughter) is here—given up for dead and now alive! Given up for lost and now found!’”

“And,” the story tells us, “they began to have a wonderful time.” https://www.facebook.com/kenneth.tanner/posts/10218492524481751

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's the deal w the black tapes I keep on hearing stuff about it but I never got a sense of why it was so good everyone seemed to know it but it's ending was so bad everyone unanimously dropped it

so i was never around for the online following of tbt so i can only give you my opinion, not broad opinion. my opinion is that the first three episodes work really well as like. sincerely, unironically good episodic horror. like genuinely it's the kind of stuff i CRAVE because it straight facedly pretends to be like. an npr-alike nonfiction podcast. to the point that the actors and writers aren't even credited until the end of each season. and it totally plays in this space of like. stuff that's JUST non-paranormal enough to feel like it could almost be a real story, but is scary as shit. like the unsound scared the bejesus out of me when i first heard it.

but then starting in ep four and continuing for the rest of the season it 1) jumps into campy, ouijia board and the exorcist inspired satanic panic lore, and 2) becomes serialized in a way that kills horror.

later, in the second season, it manages to jump the shark into charmingly intentional camp and i start liking it again. mostly as like. a salacious and journalistically unethical romance between our protagonist and sexy richard dawkins.

but even though i like the later stuff, it still frustrates me because the podcast that it started out as is a podcast i genuinely want to listen to SO bad.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Do memes provide a useful way of understanding politics?’

Before we get into our topic, what exactly is a memes? These days, memes have grown in popularity. A meme, in my opinion, is a piece of information that is hilarious, goes viral on the internet, and may be remixed and changed over time. These are also the main elements that define a meme. As to Pettis's (2018) study, Richard Dawkins provided the initial definition of the term "meme" in his book ‘The Selfish Gene’. The term "memes" was first used by Dawkins (1976) to describe the transmission of ideas virally. Memes are similar to biological "genes" in that they are self-replicating and convey information, opinions, perceptions, and beliefs that are shared across individuals (Kasirye 2019). Dawkins defined a meme as any unit of culture that might be copied and transmitted among humans; examples of such units of culture include popular songs, fashion trends, or religious traditions (Pettis 2018). Dawkins did not define memes only as pictures and videos.

Do memes provide a useful way of understanding politics?

Even though memes might be a fun method to share knowledge, they are not a reliable tool for understanding political topics in their entirety. For what reason? Memes frequently employ humour, satire, or exaggeration to express a point; it is impossible to determine if the content is real or fabricated. It could also include bias from the author. For instance, if I dislike a politician, my memes will highlight all of their flaws, even if they are good politicians overall. However, it also offers a useful way of knowing politics, as shown in the memes below. Through this meme, teens will know that who is our Prime Minister and what happen between them.

Memes provide a useful way of understanding politics because of the funny point, it can attract teenagers easily, compared to news. It can serve as a gateway for young people to become more politically aware and involved.

Simplified Political Messaging

Besides, the complexity of political messages is another reason why the majority of people in today's society don't fully understand politics. Political information is more widely available to the general public because to memes, which frequently create complicated political messaging into formats that are easy to understand. For instance, the government usually makes announcements through news or videos during the MCO time. Personally, I am lazy to bother watching these announcements, especially because the most of them are in Bahasa Melayu. Because of memes, they made the announcement in this instance easier for me to understand. Memes need to be humorous and relatable, like I already stated. On these two main components, they simplified political message, people began to share with their friends, and the general public began to understand politics. However, this can also lead to the dissemination of false information or misinformation due to the bias of the authors.

Impact of Politics Memes

In 2019, the government officially announced that the voting age would be lowered from 21 to 18 years old. But when it comes to voting, memes could have an impact. Since those teens have minimal political knowledge, they will select politicians who frequently appear in memes. Participants may also use an anonymous account to publish their own memes in order to market themselves and make teens remember them. In the book "Memes in Digital Culture," Shifman explains how memes were effectively used in the US election of 2008. Because to memes, Obama received around 70% of the vote among Americans under 25 in the 2008 US presidential election (Oakes 2020). Politicians may create humorous content and advertise a nice, friendly image to the public by using memes. They will be able attract more teenagers to vote for them if they use this strategy.

Conclusion

Memes, in my opinion, can help us understand politics, but only if we are able to identify the difference between information that is true and that is fake. Political memes may make politics easier for pupils to recognise and comprehend than heavy textbooks, especially for those taking history exams. Additionally, because of its hilarious element, which makes politics less boring, and since it is simple to attract people in, it is also a helpful approach to learn about politics.

youtube

References

Dawkins, R 1976, The Selfish Gene , download.booklibrary.website, viewed 19 October 2023, < https://download.booklibrary.website/the-selfish-gene-richard-dawkins.pdf>.

Kasirye, F 2019, ‘THE EFFECTIVENESS OF POLITICAL MEMES AS A FORM OF POLITICAL PARTICIPATION AMONGST MILLENNIALS IN UGANDA’, Journal of Education and Social Sciences, vol. 13, no. 1, viewed 20 October 2023, <https://www.jesoc.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/KC13_032.pdf >.

Limor Shifman 2014, Memes in Digital Culture, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, viewed 20 October 2023, <https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=348695e0-233d-3fc5-9070-95351505ffab>.

Oakes, A 2020, How has social media changed the US presidential election?, New Digital Age, viewed 21 October 2023, <https://newdigitalage.co/social-media/how-has-social-media-changed-the-us-presidential-election/>.

Pettis, B 2018, ‘Pepe the Frog: A Case Study of the Internet Meme and its Potential Subversive Power to Challenge Cultural Hegemonies’, Scholars’ Bank (University of Oregon), University of Oregon, viewed 17 October 2023, <https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1794/24067/Final%20Thesis-Pettis.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y>.

Shifman, L 2013, ‘Memes in a Digital World: Reconciling with a Conceptual Troublemaker’, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 362–377, viewed 20 October 2023, < https://academic.oup.com/jcmc/article/18/3/362/4067545>.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

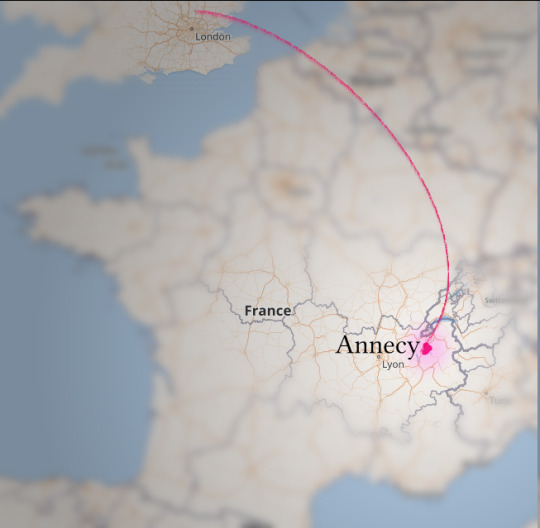

L’Aventure de Canmom à Annecy - Dimanche/Lundi

Bonsoir mes amis!

I am in Annecy, the unreasonably picturesque home of the Annecy International Animated Film Festival! I have discovered that the Annecy International Animated Film Festival involves a lot more standing in long queues in the hot sun than I expected! Nevertheless, I’m here and making the best of it.

So.

dimanche - le voyage à annecy

First of all, Sunday! I set off at 3am on Sunday morning, taking a bus, followed by two tubes, followed by another bus to the airport. The last bus was late. I met a couple of nice PhD students on their way to the same airport, and they were gonna get all of us an uber, but then the bus showed up after all.

At the airport, security threw away my 200ml bottle of sunblock. Can never be too careful I guess >< Inevitably, Richard Dawkins and his little pot of honey leapt unbidden into my brain. I promise I did not call anyone a “dundridge”.

The flight itself was uneventful! I was behind three other Annecy-goers, a very sweet gay couple and their friend... we hit it off pretty well but they were on a later bus and I haven’t seen them since I got here ^^’ Once I landed in Geneva I was racing across the city to try to get to the Annecy bus in time (I left myself an hour, which turned out to be way too little time to get through customs, out the airport, onto the train etc.) Trains in Switzerland are nuts, some of them are split across multiple levels and even the ones that aren’t have like, steep steps to get aboard.

Like “fuck you if you’re in a wheelchair” I guess.

Luckily the bus to Annecy was late! So by midday on Sunday I was in Annecy!

I ran into a group of Swiss animation students who were happy to let me tag along for a while. They just finished their graduation films and they were terribly excited about Spider-Verse. They ended up arranging to meet a couple of animators at Cartoon Saloon so I ended up witnessing some honest to god Networking. The imposter syndrome kicked in about when they were showing the cartoon saloon animators clips from their demo reels. I didn’t even have business cards. Apparently that’s a thing people bring???

pictured: swiss animation students approaching Lake Annecy.

Anyway my legs got really tired from standing up and no sleep. I bought myself an expensive crêpe and sat down on the floor to eat it. No films were due to start for hours.

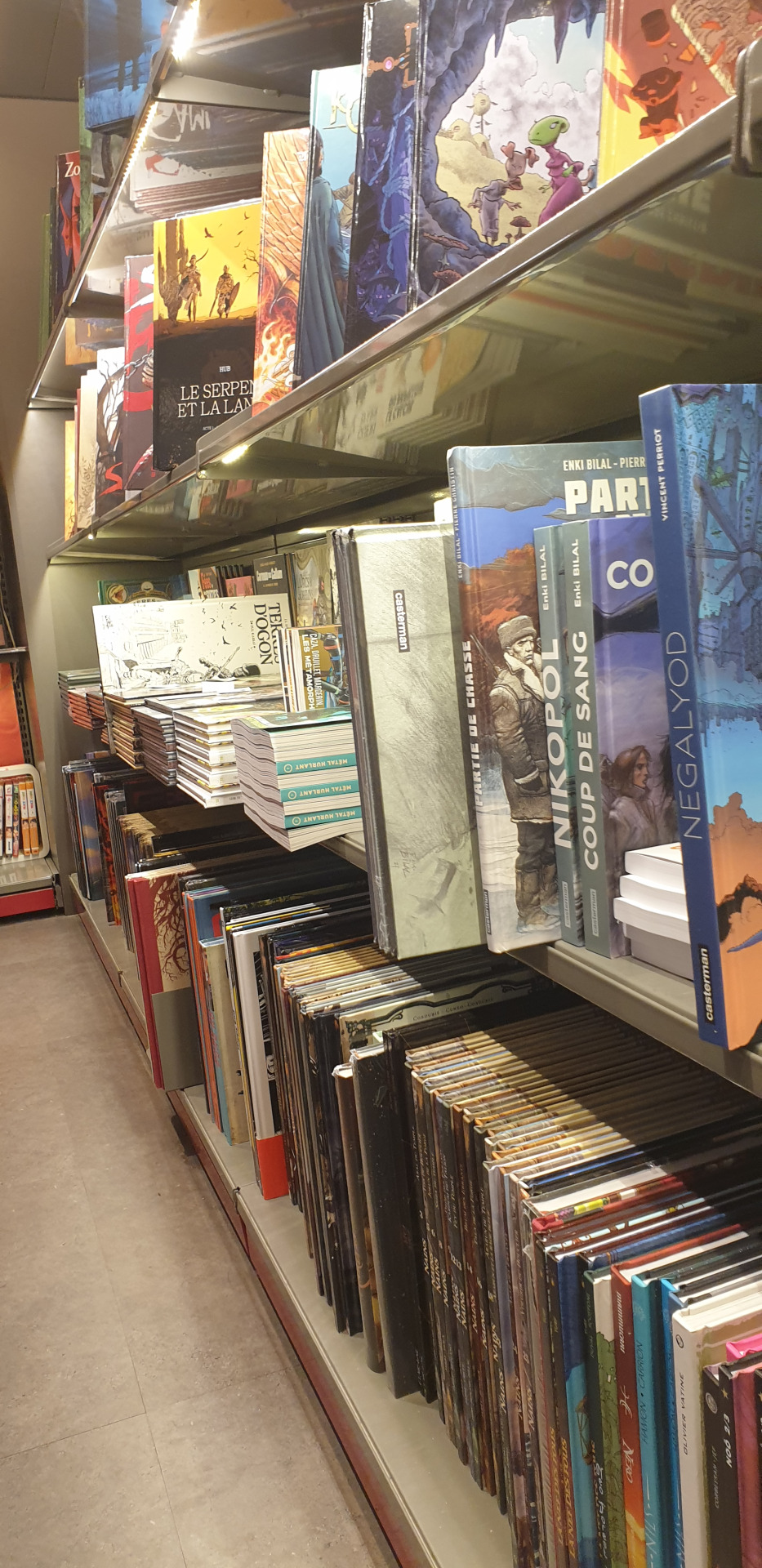

I went down to a comic book shop in Bonlieu. French comic book shops are fucking insane. All the books are enormous glossy hardbacks that cost like 50+ euros. I could totally walk away with the complete works of Moebius or Enki Bilal if things like ‘money’ and ‘getting through the airport’ and ‘not reading French’ weren’t factors. But equally there’s so much stuff that I’ve just plain never heard of. I could spend a month in this one shop easy.

At 3am my hotel checkin opened! Though in French you don’t say ‘check in’, you say j’ai un reservation. By this point I had been awake for more than 24 hours so I decided to go have a nap and eat the falafels I brought with me (very good idea, would recommend having a snack) and wake up for the opening ceremony.

Hotel comments: It’s pretty comfy! Nothing super fancy but I don’t need super fancy. The breakfast is kind of crazy expensive. I had a bit of a scare when it turned out that they hadn’t charged me when I booked the room, and wanted payment now, but thankfully I have a job now so I could take that in stride ^^’

At this point I discovered my plug adapter supports the US, Australia, New Zealand and Japan... but not Europe. Fortunately I had a power bank with me so I could keep my phone alive (its battery is pretty shot) so I resolved to buy a new adapter on Monday.

I woke up shortly before the opening ceremony and quickly concluded that there was no way I was going to be making it down to the opening ceremony and went back to sleep. I slept a really long time. But I think I needed it. Shame to miss the ceremony but odds are I probably wouldn’t have even been able to get in, someone else said she’d queued for two hours.

lundi - les files d'attente

(lmao is that really the french for ‘queues’? ‘files d’attente’?)

A beautiful morning in Annecy! I walked over to the supermarché and got myself some pasta ingredients and a ‘veggie dog’ (falafels in a baguette) from a French bakery. I learned just how limited my French vocab is. But it’s a little reassuring to find French people who speak about as much English as I speak French. (Have not yet tried to speak Japanese to any French person but it will probably happen.)

Anyway. Films time, at last!

So the way Annecy works is, you get a certain number of reservations per day depending on your ticket type. If you don’t have a reservation you can optimistically show up at the theatre anyway, and whatever seats they have left go to the line. From the website it sounded like you’d have a pretty good chance to get in.

My friends. That is a lie.

To get in to a popular non-reserved screening you have to turn up basically hours in advance. Otherwise you arrive at the back of a queue like this, stand in line for a while, and then someone in a red shirt comes out and tells you you’re too late and you go find something else to do.

I have already become very familiar with this particular stretch of ground outside Cinema Pathé. That said, the queues are a good chance to meet people! So I ended up making a couple of connections, mostly with animation students from various places. It turns out a ‘Grand Public’ ticket is a bit of an odd duck.

As you can see in that picture, a lot of people had umbrellas. This is something I neglected, and had to use my bag instead, like so:

Guess where I got sunburned.

One of those something elses I did was walk into the VR films room. This runs on its own reservation system, with each film having somewhere between 2 and 6 headsets, which get sanitised between viewings. The whole room looks kinda scifi with its cables dangling from the ceiling...

The only VR film available when I arrived was called Black Hole Museum + Body Browser by Su Wen-Chi from Taiwan. This was very demoscene, with a lot of particles flying around under force fields in a black and white space; the second part involved a dancer who’d been photoscanned somehow and was displayed using waves of particles. It was neat, but I can’t say I was hugely moved? The display device was a Quest 2, but I’m not sure if it was running the particle sim on Quest 2 hardware. If it was, I’m impressed.

The other VR films were all but fully booked so I resolved to come back another day.