#norman z. mcleod

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#polls#movies#it’s a gift#its a gift#it’s a gift 1934#it’s a gift movie#30s movies#old hollywood#norman z. mcleod#w. c. fields#kathleen howard#jean rouverol#julian madison#tommy bupp#have you seen this movie poll

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Groucho Marx-Thelma Todd "Pistoleros de agua dulce" (Monkey business) 1931, de Norman Z. McLeod.

400 notes

·

View notes

Text

1922.

An illustration drawn by legendary comedy director Norman Z. McLeod.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

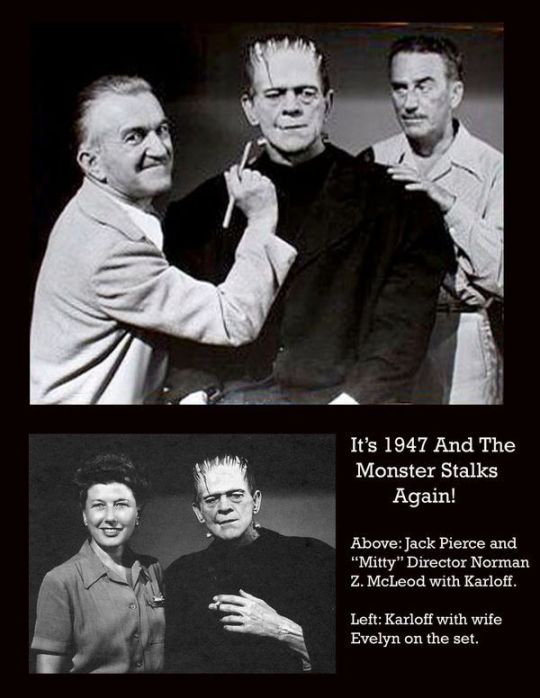

What coulda - and shoulda - been dept.:

Make-up legend Jack Pierce got to transform actor Boris Karloff one final time as the Frankenstein monster for Danny Kaye film The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (1947). Karloff had not played the monster since 1939's Son of Frankenstein. Pierce, Karloff, and the monster's make-up design were loaned by Universal Pictures to Mitty producer Samuel Goldwyn for use in a dream sequence in the film.

Unfortunately, the dream sequence was cut from the film. I haven't been able to find any definitive answer as to whether it was ever actually shot. All anyone seems to have are these make-up/costume test photos shown above.

#Jack Pierce#Boris Karloff#Frankenstein's monster#Norman Z. McLeod#Evelyn Karloff#The Secret Life of Walter Mitty

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

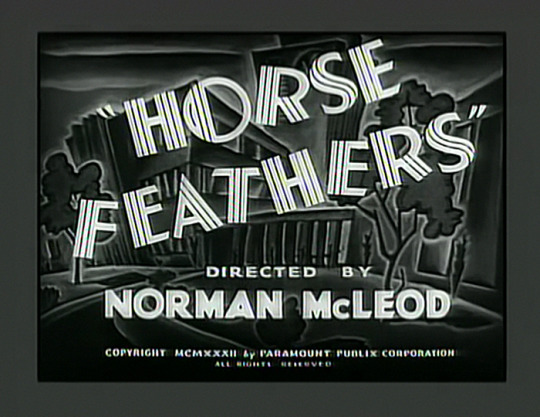

Horse Feathers Norman Z. McLeod USA, 1932 ★★★ I love sports.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

O Par Invisível Diverte-se

EUA, 1938

Norman Z. McLeod

7/10

Os Fantasmas Divertem-se

Topper foi um fenómeno de popularidade, e longevidade, no cinema e televisão norte americanos. Baseado no romance Topper, de Thorne Smith, e suas sequelas, teve três filmes originais, estreados em 1937, 1938 e 1941, uma série televisiva em 1953 e ainda um remake para televisão em 1979.

Tudo gira em torno de um casal de fantasmas, que torna a vida complicada, mas divertida, para todos os que o rodeiam, sobretudo Topper, um banqueiro simples e modesto, interpretado por Roland Young, dominado por uma esposa excêntrica, interpretada pela magnífica Billie Burke. Já os fantasmas são Cary Grant e Constance Bennett, além do cão Skippy, no primeiro filme, só Constance Bennett e Skippy neste segundo filme de 1938 e, finalmente, Joan Blondell no terceiro.

A ideia é simples mas funciona, cria situações divertidas, entretem o público com um mundo surreal, onde o espíritos aparecem e desaparecem, não para assombrar os vivos, mas para os divertirem, com as suas peripécias e a estupefação que lhes causam.

Este é um filme de puro entretenimento, em que nada faz muito sentido, mas a verdade é que, à semelhança dos restantes filmes da série, funciona, diverte, usa o sobrenatural como um elemento cómico e não como algo que assusta e pretende ser levado a sério.

Uma série clássica de sucesso, este triplo Topper. Mesmo com a inconstância de atores, o essencial mantém-se e a comédia resulta e gera empatia no espectador, muito por culpa da dupla Billie Burke e Roland Young, que são verdadeiramente, a cola que une e dá graça a esta trilogia.

Ghosts Have Fun

Topper was a phenomenon of popularity and longevity in North American cinema and television. Based on the novel Topper, by Thorne Smith, and its sequels, it had three original films, released in 1937, 1938 and 1941, a television series in 1953 and even a television remake in 1979.

Everything revolves around a couple of ghosts, who make life complicated but fun for everyone around them, especially Topper, a simple and modest banker, played by Roland Young, dominated by an eccentric wife, played by the magnificent Billie Burke. The ghosts are Cary Grant and Constance Bennett, as well as the dog Skippy, in the first film, just Constance Bennett and Skippy in this second film from 1938 and, finally, Joan Blondell in the third.

The idea is simple but it works, it creates fun situations, entertaining the public with a surreal world, where spirits appear and disappear, not to haunt the living, but to amuse them, with their adventures and the astonishment they cause them.

This is a film of pure entertainment, in which nothing makes much sense, but the truth is that, like the other films in the series, it works, it entertains, it uses the supernatural as a comedic element and not as something that scares and intends to be taken seriously.

A classic successful series, this triple Topper. Even with the inconsistency of the actors, the essential remains and the comedy works and generates empathy in the viewer, largely due to the duo Billie Burke and Roland Young, who are truly the glue that unites and gives grace to this trilogy.

0 notes

Text

Watched Today: Horse Feathers (1932)

0 notes

Photo

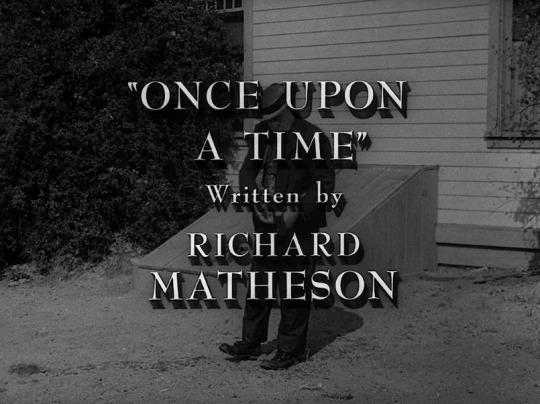

"Once Upon a Time" first aired on this day in 1961

3.13 Once Upon a Time

Director: Norman Z. McLeod

Director of Photography: George T. Clemens

“’To each his own.’ So goes another old phrase to which Mr. Woodrow Mulligan would heartily subscribe, for he has learned–definitely the hard way –that there’s much wisdom in a third old phrase, which goes as follows: ‘Stay in your own backyard.’ To which it might be added, ‘and, if possible, assist others to stay in theirs’“

#otd#the twilight zone#Twilight Zone#norman z. mcleod#Rod Serling#Richard Matheson#buster keaton#silent film#silent comedy#scifi#speculative fiction#cinematography#tv#retro tv#classic television

46 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Alice in Wonderland (1933) dir. Norman Z. McLeod

#alice in wonderland#alice in wonderland 1933#norman z mcleod#filmedit#classicfilmblr#1930s#caps#*#*aliceinwonderland1933#500

924 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louis Armstrong in the "Skeleton in the Closet" sequence from the film Pennies from Heaven (1936).

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#if i had a million#gary cooper#charles laughton#george raft#w. c. fields#richard bennett#ernst lubitsch#norman taurog#stephen roberts#norman z. mcleod#james cruze#william a. seiter#h. bruce humberstone#lothar mendes#1932

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fred Astaire-Betty Hutton "Let´s dance" 1950, de Norman Z. McLeod.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Janitor in the 1890’s dreamed what a utopia the future must be. Using an invention from his employer, the Janitor traveled into the future to the year 1962. 1962 was hardly the utopia Woodrow Mulligan imagined. Finding the future loud, dirty, and dangerous, Mulligan gladly returned to 1890 and took a scientist named Rollo back with him. Rollo had dreamed of living in the simpler times but once he got back to the 1890’s he got bored and missed his modern luxeries. ("Once Upon a Time", The Twilight Zone, TV)

#nerds yearbook#time travel#time machine#1962#1890s#tz#twilight zone#richard matheson#rod serling#norman z mcleod#buster keaton#woodrow mulligan#stanley adams#rollo#james flavon#gil lamb#jesse white#harry fleer#norman papson#warren parker#milton parsons#george e stone#arthur tovey#once upon a time#1890

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seen (again) in 2024:

Horse Feathers (Norman Z. McLeod), 1932

#films#movies#stills#Horse Feathers#Norman Z McLeod#Chico Marx#Thelma Todd#Marx Brothers#1930s#Hollywood#pre-Code#seen in 2024

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monkey Business Norman Z. McLeod USA, 1931 ★★★

3 notes

·

View notes