#nguni mythology

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

day 20 of horror mythology: tikoloshe

tikoloshe are a mischievous and evil spirit that can become invisible by drinking water or swallowing a stone. tokoloshes are called upon by malevolent people to cause trouble for others. at its least harmful, a tokoloshe can be used to scare children, but its power extends to causing illness or even the death of the victim.

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stars are not just distant specks of light in the African night sky but the guiding lights of mythology, culture, and spirituality.

Indigenous astronomical knowledge is recorded among many African tribes like the Dogon people of Mali, who have rich astronomical knowledge and are said to have made ancient observations of the planetary orbits of Saturn, Mars, Venus and Jupiter with her four major moons.

The traditional astronomical knowledge of the San and Nguni people of Southern Africa is recorded to have guided their agriculture irrigation systems and inspired their religious practices.

In many African societies, navigating life with the guidance of stars has birthed a rich reservoir of practical knowledge useful for timekeeping, agriculture, geography, record keeping and history.

As we explore culture and astronomy from the Chokwe perspective, we must state that we see the skies as we are. Our place on the planet determines our seasons, which affects what heavenly bodies we can observe. Perceptions of star patterns are influenced by the latitude of the observer, and from around 10 degrees south, the Chokwe had the geographical placement to observe and intertwine their star knowledge with their practices and identity.

For the Chokwe, stars tell the story of their people, weaving an intricate tale that forms the fabric of their identity. To the Chokwe, the life of a star is like the story of man, starting with birth, coloured by obstacles and triumph, before ending with the honour of death. The night sky has served as a source of wisdom, a symbol of royalty, and a connection to their revered ancestors.

To learn Chokwe astronomy, we must begin with Tangwa, the sun; Ngonde, the moon's phases; Litota, the stars; and Ntongonoshi, the universe in relation to the stars.

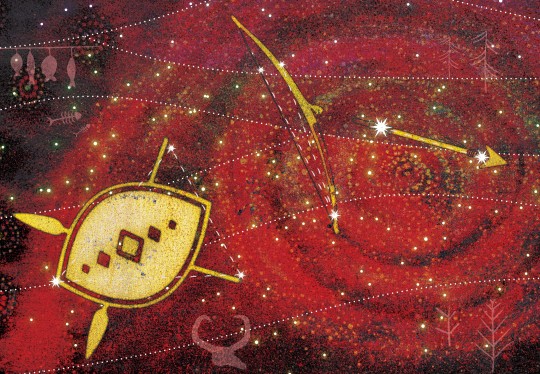

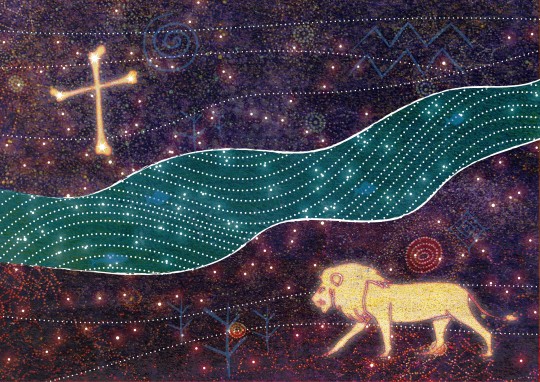

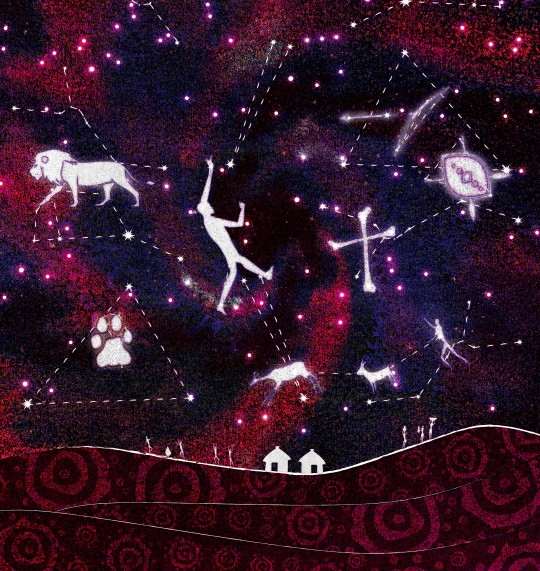

Royalty is a central part of Chokwe culture and is reflected in the sky where we see Ndumba, the lion that walks among the Tulamba - the ancestors, who guide his invisible stride in the Milky Way, leaving paw prints of litota in his path. The Chokwe people refer to the Milky Way as the Mulawiji or the Resting River, and it is used primarily as a star calendar and a compass. This shows an intimate knowledge of the skies as the orientation of the Milky Way changes considerably over the course of the year. Chokwe diviners call the Milky Way the Mulalankungu, which means the King's Road. Nkungu is the name of the great, ancient Chokwe king, and the term refers to him. The Milky Way is a significant part of divination stories, and the diviner's basket, or Ngombo, has objects that represent the stars that the diviner uses as symbols for interpretation.

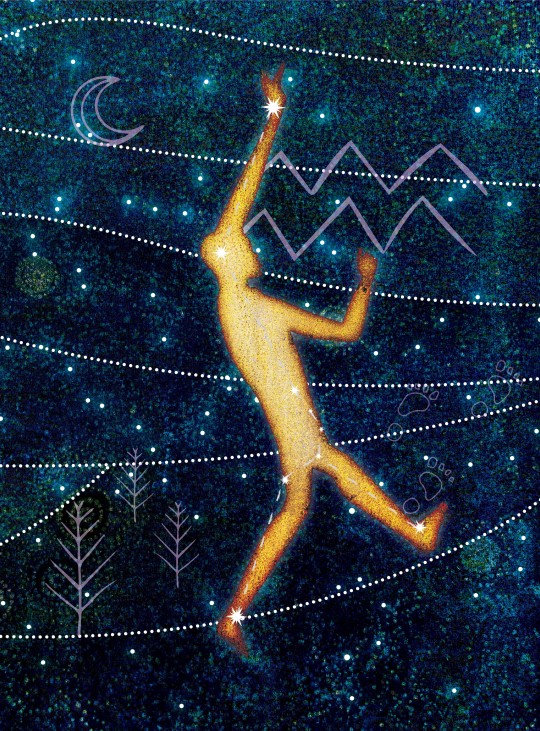

We are also introduced to Tutumwe Twa Mwanangana, which means 'Child of Wisdom' or 'Sending a Message to the Lord of the Land'. This constellation is depicted as four stars displaying a running, sweating messenger sent to announce the arrival of Mwenga, the new wife represented by the morning star, Venus. We see him spanning across four stars encapsulated in the three constellations of Bootes, Coronae Borealis and Herculis. The four stars, Alphecca, his head; Coronae Borealis accentuating the curve of his powerful hips as he runs; Herculis is his leg extended behind him and in his outstretched hand, Arcturus, the bright message of wisdom.

The beauty of Chokwe cosmology is endless, with serendipitous parallels to Western astronomy. For example, the hunter seen in Orion's Belt is also seen as a hunter by the Chokwe, and they call it Tujita Jita, symbolically interpreted as 'go to fight and always win'. Interestingly, for the Chokwe, the hunter is much closer to his dog in the constellation than in Greek and Egyptian mythology, where the dogs are in separate Canis Minor and Major constellations. Tujilika spans across three modern constellations of Triangulum Australe, Circinus and Centaurus. The symbolic meaning of Tujikila to the Chokwe people is 'the children are protecting you.'

The Nkungu – The Southern Cross represents the ancestors' bones shown by the four brightest stars connected in a cross, and this constellation guides the Mukanda, a circumcision initiation ceremony practised by the Chokwe.

The Seven Sisters, or The Pleiades, are Van Ava Nkungulwila, a lion's claws. Nkungulwila refers to the Nkungu clan and its people, and just as they are together on earth, they are together in the heavens, forming a relationship between heaven, earth, life, and death. The Chokwe see the heavens as their ancestors' home; in their cosmology, when people die, they are reborn in the lion's claws – The Seven Sisters. Considering this belief, it is fascinating to note that astronomers have recognised that this constellation is a star factory where new stars are created as the interstellar gas cloud contracts under the force of gravity. There are reddish stars within the constellation that astronomers recognise as dying stars in a supernova, which the Chokwe recognise as the Nalindele; a star whose season is over and is waning; this story is told in relation to an old wife.

Ancient Chokwe star lore, steeped in symbolism and cultural significance, aligns intriguingly with Western scientific discoveries. It's a reminder that despite diverse perspectives, our shared celestial heritage connects us all.

Modern Zambian society is embracing its traditional star knowledge in exciting ways. Young Zambians blend age-old wisdom with contemporary science and technology, forging a path towards the stars. A brief look can be taken at the enduring legacy of the Zambia Space Program of Edward Nkoloso, who coined the term Afronauts, which has come to embody a time when Zambians were bold and brave about exploring the wondrous mysteries of the universe.

The stars have a unique way of uniting us all, transcending borders, cultures, and time. Our fascination with the night sky is universal, but it's crucial to stay curious and remember that the cosmos is vast and diverse, just like the cultures it inspires. Whether you're gazing at the stars from the Chokwe heartlands of Northwestern Zambia or the bustling streets of Lusaka, we're all part of a timeless story that stretches beyond the horizon of our understanding. The stars above are the same stars that have guided us since time immemorial, reminding us of our shared journey through the great expanse of the universe.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vessel for Serving Beer (Izikhamba), Northern Nguni, 1925, Art Institute of Chicago: Arts of Africa

Among the Zulu, potter is a specialized art form practiced by skilled women wo make wares for family use and for sale. Archaeology has revealed ceramic traditions in the region that date to the first century B.C., and Nguni-speaking ancestors of the Zulu are believed to have begun making pottery in the early second millennium A.D. Not surprisingly given its historic importance, pottery has symbolic dimensions that are expressed both covertly and overtly in Zulu culture. According to Zulu mythology, for example, the earth—which is both the resting place of the ancestors and the provider of nourishment for the living—is perceived as feminine. The earth also supplies the clay that women use to make pots. Vessels are made for a variety of domestic needs, including the preparation and serving of food and drink, and many of these purposes have important ritual dimensions. Supreme among them is the brewing and serving of beer. Sorghum beer, called utshwala, has been produced in the Zulu region for at least as long as potter has. It is considered the food of the ancestors, who are drawn to its smell from first brewing to full flower. For this reason, numerous rules and prohibitions guide its making, storing, serving, and drinking. The beverage’s popularity increased in the nineteenth century as crops became more plentiful, and its significance as a social lubricant that could promote solidarity within a community also expanded. Today, homemade beer made from sorghum and other grains continues to be an essential part of Zulu ritual and social life, and ceramic pots have remained the favored container. Zulu potters use a variety of patterns to ornament beer vessels, the textures of which stand in strong contrast to the pots’ highly burnished surfaces. This pot illustrates a widespread decorative technique in which small semicircular indentations are pressed into the clay in tight rows that define a geometric shape or band. Here the marks are crisply executed and inscribe two large triangles extending point-to-point at an angle across the body of the vessel. Gift of Keith Achepohl Size: 21.6 x 26.7 cm (8 1/2 x 10 1/2 in.) Medium: Blackened terracotta

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/185691/

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vessel for Serving Beer (Izikhamba), Northern Nguni, 1925, Art Institute of Chicago: Arts of Africa

Among the Zulu, potter is a specialized art form practiced by skilled women wo make wares for family use and for sale. Archaeology has revealed ceramic traditions in the region that date to the first century B.C., and Nguni-speaking ancestors of the Zulu are believed to have begun making pottery in the early second millennium A.D. Not surprisingly given its historic importance, pottery has symbolic dimensions that are expressed both covertly and overtly in Zulu culture. According to Zulu mythology, for example, the earth—which is both the resting place of the ancestors and the provider of nourishment for the living—is perceived as feminine. The earth also supplies the clay that women use to make pots. Vessels are made for a variety of domestic needs, including the preparation and serving of food and drink, and many of these purposes have important ritual dimensions. Supreme among them is the brewing and serving of beer. Sorghum beer, called utshwala, has been produced in the Zulu region for at least as long as potter has. It is considered the food of the ancestors, who are drawn to its smell from first brewing to full flower. For this reason, numerous rules and prohibitions guide its making, storing, serving, and drinking. The beverage’s popularity increased in the nineteenth century as crops became more plentiful, and its significance as a social lubricant that could promote solidarity within a community also expanded. Today, homemade beer made from sorghum and other grains continues to be an essential part of Zulu ritual and social life, and ceramic pots have remained the favored container. Zulu potters use a variety of patterns to ornament beer vessels, the textures of which stand in strong contrast to the pots’ highly burnished surfaces. This pot illustrates a widespread decorative technique in which small semicircular indentations are pressed into the clay in tight rows that define a geometric shape or band. Here the marks are crisply executed and inscribe two large triangles extending point-to-point at an angle across the body of the vessel. Gift of Keith Achepohl Size: 21.6 x 26.7 cm (8 1/2 x 10 1/2 in.) Medium: Blackened terracotta

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/185691/

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vessel for Serving Beer (Izikhamba), Northern Nguni, 1925, Art Institute of Chicago: Arts of Africa

Among the Zulu, potter is a specialized art form practiced by skilled women wo make wares for family use and for sale. Archaeology has revealed ceramic traditions in the region that date to the first century B.C., and Nguni-speaking ancestors of the Zulu are believed to have begun making pottery in the early second millennium A.D. Not surprisingly given its historic importance, pottery has symbolic dimensions that are expressed both covertly and overtly in Zulu culture. According to Zulu mythology, for example, the earth—which is both the resting place of the ancestors and the provider of nourishment for the living—is perceived as feminine. The earth also supplies the clay that women use to make pots. Vessels are made for a variety of domestic needs, including the preparation and serving of food and drink, and many of these purposes have important ritual dimensions. Supreme among them is the brewing and serving of beer. Sorghum beer, called utshwala, has been produced in the Zulu region for at least as long as potter has. It is considered the food of the ancestors, who are drawn to its smell from first brewing to full flower. For this reason, numerous rules and prohibitions guide its making, storing, serving, and drinking. The beverage’s popularity increased in the nineteenth century as crops became more plentiful, and its significance as a social lubricant that could promote solidarity within a community also expanded. Today, homemade beer made from sorghum and other grains continues to be an essential part of Zulu ritual and social life, and ceramic pots have remained the favored container. Zulu potters use a variety of patterns to ornament beer vessels, the textures of which stand in strong contrast to the pots’ highly burnished surfaces. This pot illustrates a widespread decorative technique in which small semicircular indentations are pressed into the clay in tight rows that define a geometric shape or band. Here the marks are crisply executed and inscribe two large triangles extending point-to-point at an angle across the body of the vessel. Gift of Keith Achepohl Size: 21.6 x 26.7 cm (8 1/2 x 10 1/2 in.) Medium: Blackened terracotta

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/185691/

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vessel for Serving Beer (Izikhamba), Northern Nguni, 1925, Art Institute of Chicago: Arts of Africa

Among the Zulu, potter is a specialized art form practiced by skilled women wo make wares for family use and for sale. Archaeology has revealed ceramic traditions in the region that date to the first century B.C., and Nguni-speaking ancestors of the Zulu are believed to have begun making pottery in the early second millennium A.D. Not surprisingly given its historic importance, pottery has symbolic dimensions that are expressed both covertly and overtly in Zulu culture. According to Zulu mythology, for example, the earth—which is both the resting place of the ancestors and the provider of nourishment for the living—is perceived as feminine. The earth also supplies the clay that women use to make pots. Vessels are made for a variety of domestic needs, including the preparation and serving of food and drink, and many of these purposes have important ritual dimensions. Supreme among them is the brewing and serving of beer. Sorghum beer, called utshwala, has been produced in the Zulu region for at least as long as potter has. It is considered the food of the ancestors, who are drawn to its smell from first brewing to full flower. For this reason, numerous rules and prohibitions guide its making, storing, serving, and drinking. The beverage’s popularity increased in the nineteenth century as crops became more plentiful, and its significance as a social lubricant that could promote solidarity within a community also expanded. Today, homemade beer made from sorghum and other grains continues to be an essential part of Zulu ritual and social life, and ceramic pots have remained the favored container. Zulu potters use a variety of patterns to ornament beer vessels, the textures of which stand in strong contrast to the pots’ highly burnished surfaces. This pot illustrates a widespread decorative technique in which small semicircular indentations are pressed into the clay in tight rows that define a geometric shape or band. Here the marks are crisply executed and inscribe two large triangles extending point-to-point at an angle across the body of the vessel. Gift of Keith Achepohl Size: 21.6 x 26.7 cm (8 1/2 x 10 1/2 in.) Medium: Blackened terracotta

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/185691/

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vessel for Serving Beer (Izikhamba), Northern Nguni, 1925, Art Institute of Chicago: Arts of Africa

Among the Zulu, potter is a specialized art form practiced by skilled women wo make wares for family use and for sale. Archaeology has revealed ceramic traditions in the region that date to the first century B.C., and Nguni-speaking ancestors of the Zulu are believed to have begun making pottery in the early second millennium A.D. Not surprisingly given its historic importance, pottery has symbolic dimensions that are expressed both covertly and overtly in Zulu culture. According to Zulu mythology, for example, the earth—which is both the resting place of the ancestors and the provider of nourishment for the living—is perceived as feminine. The earth also supplies the clay that women use to make pots. Vessels are made for a variety of domestic needs, including the preparation and serving of food and drink, and many of these purposes have important ritual dimensions. Supreme among them is the brewing and serving of beer. Sorghum beer, called utshwala, has been produced in the Zulu region for at least as long as potter has. It is considered the food of the ancestors, who are drawn to its smell from first brewing to full flower. For this reason, numerous rules and prohibitions guide its making, storing, serving, and drinking. The beverage’s popularity increased in the nineteenth century as crops became more plentiful, and its significance as a social lubricant that could promote solidarity within a community also expanded. Today, homemade beer made from sorghum and other grains continues to be an essential part of Zulu ritual and social life, and ceramic pots have remained the favored container. Zulu potters use a variety of patterns to ornament beer vessels, the textures of which stand in strong contrast to the pots’ highly burnished surfaces. This pot illustrates a widespread decorative technique in which small semicircular indentations are pressed into the clay in tight rows that define a geometric shape or band. Here the marks are crisply executed and inscribe two large triangles extending point-to-point at an angle across the body of the vessel. Gift of Keith Achepohl Size: 21.6 x 26.7 cm (8 1/2 x 10 1/2 in.) Medium: Blackened terracotta

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/185691/

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vessel for Serving Beer (Izikhamba), Northern Nguni, 1925, Art Institute of Chicago: Arts of Africa

Among the Zulu, potter is a specialized art form practiced by skilled women wo make wares for family use and for sale. Archaeology has revealed ceramic traditions in the region that date to the first century B.C., and Nguni-speaking ancestors of the Zulu are believed to have begun making pottery in the early second millennium A.D. Not surprisingly given its historic importance, pottery has symbolic dimensions that are expressed both covertly and overtly in Zulu culture. According to Zulu mythology, for example, the earth—which is both the resting place of the ancestors and the provider of nourishment for the living—is perceived as feminine. The earth also supplies the clay that women use to make pots. Vessels are made for a variety of domestic needs, including the preparation and serving of food and drink, and many of these purposes have important ritual dimensions. Supreme among them is the brewing and serving of beer. Sorghum beer, called utshwala, has been produced in the Zulu region for at least as long as potter has. It is considered the food of the ancestors, who are drawn to its smell from first brewing to full flower. For this reason, numerous rules and prohibitions guide its making, storing, serving, and drinking. The beverage’s popularity increased in the nineteenth century as crops became more plentiful, and its significance as a social lubricant that could promote solidarity within a community also expanded. Today, homemade beer made from sorghum and other grains continues to be an essential part of Zulu ritual and social life, and ceramic pots have remained the favored container. Zulu potters use a variety of patterns to ornament beer vessels, the textures of which stand in strong contrast to the pots’ highly burnished surfaces. This pot illustrates a widespread decorative technique in which small semicircular indentations are pressed into the clay in tight rows that define a geometric shape or band. Here the marks are crisply executed and inscribe two large triangles extending point-to-point at an angle across the body of the vessel. Gift of Keith Achepohl Size: 21.6 x 26.7 cm (8 1/2 x 10 1/2 in.) Medium: Blackened terracotta

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/185691/

0 notes