#nat jackley

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Play for Today: A Touch of the Tiny Hacketts (BBC, 1978)

"It is very possible that I could have stopped it ever getting into the papers."

"Well, I don't see how, we don't even know how they found out about it."

"You're missing the point, Ray, there are things like injunctions for contingencies like this."

"Against who?"

"Oh, don't get me wrong, I'm not saying I'm a legal expert. But I will say this: I am experienced enough in life to know the value of the Mr. Ridleys of this world."

"Well, I know he was very good over the crazy paving, but is he capable of slapping injunctions against newspaper editors? I mean, particularly when they only printed the truth?"

"I dunno. But we could've tried him. And failing him - had you told me - who knows? I could have taken it to the ombudsman!"

#play for today#a touch of the tiny hacketts#1978#bbc#single play#john esmonde#bob larbey#james cellan jones#ray brooks#judy cornwell#tony selby#brenda bruce#patrick newell#nat jackley#rusty goffe#george innes#anthony langdon#karl howman#doug fisher#george tovey#a mild farce from sitcom stalwarts Larbey and Esmonde (The Good Life‚ Ever Decreasing Circles etc)‚ filled with sitcom faces (Selby fresh#from working with the writers on Get Some In!‚ Howman later to star for them in Brush Strokes). it's all quite silly but pleasantly so#Brooks is a mild mannered home body who one night apprehends (and knocks unconscious) a burglar in his home; the attitude of everyone in#his life changes overnight as a result of his perceived heroics‚ only to change again (for the worse) once it becomes known the would be#robber is a person with dwarfism. this could have been badly handled‚ as could the crux of the plot (that everyone is son concerned with#appearing‚ to use a modern term‚ 'pc' that they lose sight of the point that the man was breaking into a house) but to give them their dues#the writers mostly keep it pretty balanced and the emphasis is much more on the casual hypocrisy of Brooks' co workers and friends (Newell#is a stand out as the boss whose heart supposedly bleeds for what he calls 'unfortunates' but who is really taking advantage of being able#to pay minority workers a lower wage). I'm making a hash of these tags but this is genuinely p funny and largely inoffensive I think#Brenda Bruce is mvp in a beautifully deadpan performance as the robber's mother‚ telling the sad tale of his life to a bemused Brooks

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

70th anniversary of Aladdin London Casino, 103 performances with 1 charity preview (19 December 1951 - 23 February 1952)

This week marks the 70th anniversary of another milestone event in the early career of Julie Andrews: the opening of Aladdin at the London Casino on 19 December 1951.

Aladdin was Julie’s third annual pantomime, following earlier runs in Humpty Dumpty (1948) and Red Riding Hood (1950). By Christmas 1951, Julie was 16-years-old and an established young star of variety and radio. She was thus 'promoted’ in Aladdin to the ‘principal girl’ role of Princess Balroulbadour — her first adult part — and given top billing alongside the show’s other principals, Jean Carson and Nat Jackley (Bishop, p. 6; ’Principal’, p. 5).

Aladdin also marked the second Christmas show Julie did with Emile Littler, the celebrated theatre impresario who, as discussed in an earlier post, was a formative figure in the star’s early career. Popularly dubbed the ‘King of Pantomimes’ -- a soubriquet which was, admittedly, shared by a few other theatre magnates -- Littler was famous for his legendary Christmas extravaganzas. In any given year, Littler would produce upwards of half-a-dozen pantos across the nationwide theatre chain he ran with brother, Prince, and sister, Blanche (Pedrick, p. 8).

A producer of the old school, Littler took an active role in these shows, not only producing but also writing, casting, and, in many cases, directing them himself (Pedrick, p. 8). Such was his commitment to pantos that Littler established a dedicated production facility in Birmingham, ‘Pantomime House’, where a team of craftsmen and women worked year-round to prepare the costumes, scenery and props needed for the lavish shows (Konig 1949). “No man,” opined one contemporary commentator, “has ever carried on such a wholesale enterprise for the production of Pantomime” (Wilson, p. 127).

For the Christmas season of 1951, Littler launched an ambitious roster of eight pantos across the country: alongside Aladdin at the London Casino, there was Little Miss Muffett at the Manchester Hippodrome; Puss in Boots at the Leeds Empire; Mother Goose at the Birmingham Royal; Humpty Dumpty at the Sheffield Empire; Jack and Jill at the Plymouth Palace; Cinderella at the Hanley Royal; and, Goody Two Shoes at the Bournemouth Pavilion (’Emile Littler Sends’, p. 5)

The biggest and most prestigious Littler panto was, not surprisingly, the London offering. Commencing in 1941, Littler staged a major West End panto each Christmas, initially at various theatres but, from 1946, moving permanently into the recently refurbished London Casino which Littler co-owned with Tom Arnold (Emile Littler Souvenir, p. 25; Knox, p. 314). Aladdin would be Littler’s eleventh London pantomime and his seventh at the Casino.

The show was based on a script treatment of Aladdin that Littler had developed for earlier productions. In keeping with panto traditions, the story is set in China, rather than the Middle Eastern locales popularised though later Hollywood versions of the tale (Chang, pp. 180-192). Aladdin is a carefree lad who lives in “Old Peking” with his mother, the laundress Widow Twankey, and his spoiled younger brother, Wishee Washee. Aladdin meets and falls in love with Princess Balroulbadour, much to the displeasure of her father, the Emperor, who charges his bumbling policemen to keep the impish lad away. Meanwhile, a mysterious stranger, Abanazar, has appeared claiming to be a long lost relative of Widow Twankey. He coaxes Aladdin to accompany him to a cave in the mountains so that he may retrieve a magical lamp. Aladdin finds the lamp but refuses to give it to Abanazar as promised. Cursed and imprisoned by Abanazar in the cave, Aladdin rubs the lamp, conjuring the magical genie, Kazim, who grants Aladdin his wish to become a wealthy Prince and thus clear the way for him to marry the Princess. Abanazar returns to create more mischief, stealing the lamp and using its power to transport the Princess and the entire Palace to Egypt. In possession of a magic ring, Aladdin summons the Fairy Queen who takes the lad to Egypt in pursuit where he thwarts Abanazar, wins back the Princess, and brings proceedings to a happy ending.

As is often the case with panto, the story of Aladdin is something of a pretext for the genre’s main points of appeal: spectacle, stars, music, comedy, and audience participation. With his 1951 staging of Aladdin, Little was determined to up the ante on all counts. Afforded a huge production budget of over £50,000, it was Littler’s most expensive panto to date and he pulled out all the stops with lavish production values, state-of-the-art stagecraft, and top-notch talent (Lloyd-Williams, p. 4; Wearing 2014, p. 138).

For the costume and scenery, Littler contracted Anthony Holland, a young set designer with a flair for visual spectacle (Hainaux 1965). The show’s Eastern settings were a perfect fit for Holland’s aesthetic and he went to town designing over a thousand costumes at a cost of £15,000 (Lloyd-Williams, p. 4). The sumptuous costumes were recalled fondly by Julie (2008) in the first volume of her memoirs: “I wore exotic, sparkling headdresses, which I loved, and a lot of satin kimono-style robes with long, draped arms” (p. 140). In addition, Holland designed fifteen changing sets for Aladdin complete with revolving buildings, a garden with a huge tree made of jade clouds, and a gasp-inducing cave of magical wonders. The result was what The Times described as “a breathless succession of marvels” (‘London Casino’, p. 6).

For the music, the show featured a mix of classic tunes interspersed with original compositions by Littler’s resident house composer, Hastings Mann (‘Hastings Mann’, p, 3). Overseeing the musical arrangement and direction for the production was Debroy Somers, the celebrated big band leader and star conductor (‘Debroy’ p. 3). Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado had just come out of copyright, and the musical team drew heavily from the score, interpolating several songs -- in one scene, the chorus sang ‘Gay Little Mandarins Are We’ to the tune of ‘Three Little Maids’ -- and using other musical motifs and bridges as entrance music (‘Christmas Shows’, p. 5).

The cherry on top of this spectacular theatrical and musical confection was the cast. Announced in October 1951, the cast for Aladdin was a star-studded line-up of big names from theatre, variety, film, dance, circus, and, even, opera. Other than Julie, the show’s featured performers included:

Jean Carson as Aladdin (principal boy): A vivacious flame-haired Yorkshire lass with a strong voice, comely appearance, and good comic flair, Carson started performing from a young age as part of her parents’ music hall act and she quickly emerged as a favourite on the variety and musical theatre circuit. In 1948, aged 20, she had an early success in Starlight Roof, the celebrated Val Parnell revue show at the London Hippodrome that also launched 12-year-old Julie Andrews to stardom. The same year Carson scored her first film role with a lead in the British musical revue, Date with a Dream (1948). Something of an Emile Littler protege, Carson appeared in several of his productions including a string of Christmas pantos where she typically took the part of the principal boy. She played the role of Aladdin in a 1948/49 Littler production at the Sheffield Empire which is possibly why she was tapped to recreate the role in the bigger London staging three years later ( ‘Provincial Pantomimes’, p. 8). Littler would also give Carson her greatest stage triumph when he cast her as the lead in the Hugh Martin scored musical, Love from Judy, a role she would play to great acclaim on the West End and elsewhere from 1951-1953. A film contract with Rank ensued where Carson starred in light musical comedies such as As Long As They’re Happy (1954) and An Alligator Named Daisy (1955). At the height of her British success, Carson was coaxed to the United States by a record-making TV deal where she was rechristened Jeannie -- to avoid confusion with the American TV star, Jean Carson of Peter Gunn and The Andy Griffith Show fame (‘Jean Carson makes’, p. 11). Carson’s US career got off to a promising start. She appeared in a number of well-received TV specials before being launched as the star of her own CBS TV sitcom, Hey, Jeannie! (1955). Sadly, the series failed to ignite and it was cancelled after just one season (Tucker, pp. 54-60). Thereafter, mainstream US success eluded Carson, though she continued to find work in musical theatre. She starred in a 1960 Broadway revival of Finian’s Rainbow, where she met the man who would become her American husband, actor Biff McGuire. The pair worked frequently together, including starring in a touring production of Camelot in 1964 (Waters, p. 3). In the 1970s, the couple settled in the Seattle area where they become stalwarts of the local theatre scene for almost fifty years till McGuire’s recent passing in early-2021 (Seattle Rep 2021). As of the time of writing, Miss Carson is living in retirement in Seattle at the august age of 93. She has often been asked over the years about her memories of working with Julie and her standard reply is to boast with a smile that “I was Julie’s leading man!” (Holloway, p. A-7).

Nat Jackley as Widow Twankey (Panto Dame): Lanky and loose-limbed, Nat Jackley was a visual comic who found enormous success on the British music hall scene. Born into a show business family, Jackley started in his teens with the famous clog-dancing ‘Eight Lancashire Lads’, the same troupe that gave an early start to Charlie Chaplin and Stan Laurel (Dixon, p. 39). Jackley migrated into a series of comedy duos, first with his sister Joy and then with fellow comedian Jack Clifford, before going solo during the war. Billed as Nat ‘Rubber Neck’ Jackley, he developed a trademark blend of eccentric dancing, jerking neck movements, and an original funny walk described by one critic as “the strut of a demented turkey” (’Nat Jackley’, p. 35). At the height of his career, he topped the bill at the Palladium, appeared in three Royal Variety Performances, and made a successful tour of Australia. He also featured in a string of popular British films such as Demobbed (1944), Under New Management (1946), and Stars in Your Eyes (1956). With the demise of variety, Jackley moved into television and had a successful late career as a character actor in a diverse range of British TV shows. Another string to Jackley’s professional bow was as a legendary panto Dame and he appeared in a record fifty pantos between 1927 and his retirement in 1980 (ibid.). In Aladdin, he took on one of the most famous of all Dame roles, Widow Twankey, Aladdin’s comic-vain mother. Jackley passed in 1988, aged 79.

Walter Crisham as Abanazar: Though he is little remembered today, Crisham was a noted American actor of stage and screen who appeared in number of high profile productions. Born in Worcester, Mass. in 1908, he originally trained as a dancer and performed in several musical revues in the New York area during the 1920s. In 1933, Crisham travelled to London to appear in a dance revue called Ballyhoo and he ended up staying in the UK for almost twenty years (Short, pp. 88-89). Some of his more notable British stage successes included Cole Porter’s Nymph Errant (1933), opposite Gertrude Lawrence; the Ivor Novello musicals, Careless Rapture (1936) and Crest of the Wave (1937); several revues with favourite partner, Hermione Gingold, including Rise Above It (1941), Sweet and Low (1943) and Slings and Arrows (1948); and, with Jessie Matthews, Don’t Listen Ladies (1949). Throughout this period, Crisham made a number of films including several straight dramas such as They Met in the Dark (1943), No Orchids for Miss Blandish (1948) and Her Favourite Husband (1950). He scored his most famous film role in the small but flashy part of Valentin le Désossé in John Huston’s Moulin Rouge (1952). Though he had appeared in a West End holiday production of The Wizard of Oz in 1946, Aladdin would be Crisham’s first and only panto with one critic noting that “he makes his debut in pantomime with a zest implying that such has been his ambition all along” (Dent, p. 3). Crisham returned to the US permanently in the late-1950s, settling in the Los Angeles area. Other than a few minor TV appearances and some community theatre work, he seems to have entered semi-retirement. He passed in 1985 (‘Walter’, p. 54).

Martin Lawrence as The Emperor: A distinguished operatic bass who had forged a garlanded career in the opera houses of Europe, Lawrence might seem an unorthodox choice for a Christmas panto -- and, indeed, much was made in the press about his “history making” casting (’Concert Notes’, p. 6). His stature and booming voice was, however, a good fit for the magisterial role of the Emperor and, well versed in the comic traditions of opera buffa and Gilbert and Sullivan, Lawrence had “an ease in humorous acting” that meant “the transition from grave to gay in no way daunts him” (ibid.). Alongside his career in opera where, among other achievements, he created the role of Don Jerome in Gerhard's The Duenna, Lawrence was a strong proponent of traditional Jewish music. He made several recordings of Yiddish folk songs, wrote a number of studies on the history of Jewish music, and was, for many years, the musical director and choirmaster at the New London Synagogue till his death in 1983 at 73 years of age (‘Obituary’, p. 378).

Desmond and Marks as Bend Hi and Bend Lo: Fred Desmond and Jack Marks were dancers who met in the RAF during the war and, following ‘demob’, formed a comedy duo that lasted for decades (E.M.M., p. 2). With a 'knockabout’ comic act blending dance, pratfalls, and gags, ‘Desmond and Marks’ proved a very popular duo on the post-war variety circuit, extending to several international tours of Europe, Australia, and the US (’Variety News’, p. 3; ‘Light Entertainment’, p. 3). Like many variety acts of the era, they also found regular work in pantomimes, playing comic relief support characters and, on occasion, ‘skin’ roles including a fire-and-smoke-belching alligator (Frow, p. 179). In Aladdin, the pair performed the role of the classic -- if dubiously stereotyped -- Chinese policemen, Bend Hi and Bend Lo. Desmond and Marks performed in many other Littler pantos and could still be found doing Christmas shows into the 1980s (‘Christmas Greetings’, p. 40.).

Jimmy Clitheroe as Wishee Washee: A pint-sized comic actor who would find lasting fame on radio, Jimmy Clitheroe was one of the last of the popular tradition of music hall ‘midgets’. With his diminutive size, high-pitched voice, and musical Lancashire accent, Clitheroe developed a crowd-pleasing persona as a cheeky schoolboy with lots of sharp comments and double entrendres. In pantomimes, he would invariably play classic juvenile roles like Buttons, Tom Thumb, or, as here, Wishee Washee, Aladdin’s spoiled younger brother. Later in the decade, Clitheroe starred in his own hugely successful BBC radio series, The Clitheroe Kid that ran for 17 seasons till 1972 and spawned a parallel TV version in the 1960s (Elmes, pp. 203-7). Despite his success, Clitheroe remained his whole life in the family home, living with his mother. When his mother passed away in 1973, Clitheroe was inconsolable and, tragically, he was found dead from a suspected accidental overdose on the day of his mother’s funeral (Johnson, p. 12).

Carole Jeffries as Prince Pekoe: A 21-year-old honey-haired beauty, Jeffries was a relative newcomer in the Aladdin cast. She was a trained dancer who got an initial break as one of the burlesque troupe of ‘Windmill Girls’ at London’s Windmill Theatre (Storey, pp. 4-5). With ambitions for a career in musical theatre, Jeffries appeared in a few revues and provincial pantos, and even scored an early TV appearance (’She Gets’, p. 5). She had a small part in Littler’s 1950 panto at the Casino, Goody Two Shoes, and she must have impressed because he promoted her in Aladdin to the support ‘pants’ role of Prince Pekoe. The following Christmas, she was promoted yet again to principal girl in Dick Whittington at the Nottingham Theatre Royal. Thereafter, the available record on Jeffries grows dim. Reports state that she got married in 1953 (Stevenson 1953: p. 4), so she might have retired and/or changed her name.

David Davenport as Kazim: A versatile performer of many talents, Davenport had a distinguished career across dance, theatre, film. and television (Taylor, p. 36). He trained as a ballet dancer and performed with great success in the 1940s with several troupes including the New Russian Ballet, Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet, and the New International Ballet. In the 50s he moved into musical comedy and pantomime, while retaining his interest in dance as a choreographer. He forged a successful career in film and television with credits ranging from comedies (he was in three Carry on films) to straight dramas such as The Darwin Adventure (1972). Tall and distinguished with an athletic build and a booming voice, Davenport was ideally cast in the magical genie role of Kazim, the Slave of the Lamp in Aladdin. Indeed, he would reprise the part in several later productions including a 1967 TV broadcast on ITV. Davenport passed in 1995 at the age of 74 (Taylor, p. 36).

Jacqueline St. Clere as Fairy Moonbeam: An English ballet dancer, Jacqueline St. Clere started her career in the late-40s with the London-based Metropolitan Ballet (Percival, p. 22). Aladdin marked her West End debut in the principal dance role of the Fairy Queen where she was showcased to strong effect in the show’s spectacular second act ballet. During the run of Aladdin, St. Clere married Frank Staff, the celebrated South African dancer and choreographer (‘Chit Chat’, p. 18). The following year, she was cast by Littler again as principal dancer in his 1952 Casino panto, Jack and Jill, in the role of the Fairy of the Well (‘Seven-and-a-half’, p. 3). In 1953, St. Clere accompanied her husband back to his native South Africa where she helped him establish the influential Frank Staff Ballet Studio (Rosen, p. 95). St. Clere continued to perform in several of Staff’s ballets, and branched out into teaching and costume design. She had a son with Staff but the marriage ended sometime in the late-1950s. It is not known what become of St. Clere after that, though records suggest she remained in South Africa (Rosen, p. ix).

Ross Harvey as the Aviary Keeper: One of several 'specialty’ acts integrated into Aladdin, Ross Harvey -- real name: Harry Rossofsky -- was an American vaudeville entertainer who found considerable success with his trained bird act. Billed as ‘Ross Harvey and his Dancing Parrot-Cuties’, the act consisted of Harvey doing soft shoe routines while the birds performed acrobatic tricks on his body and fingers in time with the music (Rasmussen, p. A14). In 1951, Harvey had a high profile run at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria which garnered a good deal of press attention. The exposure inspired Emile Littler to offer Harvey a novelty spot in Aladdin where he was billed as the Royal Aviary Keeper (‘Ross’, p. 1). His act was very well received and Harvey would return to the UK several times for other pantos and variety tours throughout the 1950s. He retired from show business in the 1960s and retrained as a cosmetologist, before passing in 2010 at the grand age of 90 (Rasmussen, p. A14).

Fiery Jack as Oriental Road Hog: Another speciality spot in the show was provided by Fiery Jack -- the stage name of Fred Zetina -- a well-known British clown who plied his trade in both circuses and music halls for many decades. Born into a theatrical family of acrobats, Zetina developed a novelty act built around a comical jalopy car that would shoot flames, smoke and fall apart, hence the name ‘Fiery Jack’. In Aladdin, he appeared as a motorist in one of the set scenes allowing him to perform his automative schtick. Zetina took his final bows in 1978 at the respectable age of 93 (Ashton, p. 4).

The Olanders as the Royal Tumblers: A further specialty act was provided by this troupe of young acrobats. A family of five young brothers from Denmark, the Olanders rose to prominence on the European circus scene in the 1940s before moving into the more stable and lucrative world of cabaret and variety. They undertook a successful tour of the UK in 1948, including a run at the London Palladium on a bill with Danny Kaye. They were contracted by Emile Litter to perform in his end-of-year panto, Jack and Jill at the Manchester Hippodrome where they impressed with their “exhilarating display of high speed somersaults” (M.M., p. 3). Thereafter, the Olanders became somewhat of a regular feature on the Littler panto circuit, appearing again in his 1949 staging of Jack and Jill at the Leeds Empire (A.T., p. 6) and the show’s 1950 reprise at the Coventry Hippodrome, co-produced by Littler and S.H. Newsome (’Accent’, p. 4). In 1951, the Olanders were afforded the ultimate honour of appearing in Littler’s London panto where they were billed as Royal Tumblers in the Court of the Emperor. By this stage, one of the original brothers had left the troupe and a young English adoptee was added (’Boy Acrobat’, p. 11). The Olanders have a special place in Julie lore as one of the boys, Fred, was an early crush for the 16-year-old star. In her memoirs (2008), Julie recalls him as “attractive, fit (obviously), and very gentle and dear” (p. 140).

The Tiller Girls (Dance Chorus): This famous precision dance troupe first formed by John Tiller in the 1890s became such a popular feature of British entertainment that Tiller schools were set up all over the country and multiple troupes of trained dancers sent to theatres far and wide (Reilly 2013). Renowned for their tightly synchronised routines and disciplined kick lines, Tiller Girls provided backing for principal performers as well as showcase displays of formation dancing during spectacle scenes. The troupe of Tiller Girls used for Aladdin consisted of 32 dancers under the tutelage of Phyllis Blakston, Littler’s resident choreographer.

The Terry Children (Juvenile Chorus): Like the Tiller Girls, the Terry Children was something of a British theatrical institution of the era. Juvenile choruses, or ‘babes’ as they were often known, were a core ingredient of pantomime dating from the Victorian era and there were several companies that emerged to meet market demand for trained child performers (Varty, pp. 138-147). ‘Terry’s Juveniles’ was one of the most successful. It was established in the late-1910s by an enterprising dance instructor who went by the name of ‘Miss Terry’, likely to cash in on the celebrated Terry theatrical dynasty. By the 1930s, Miss Terry had a plush office in Shaftesbury Avenue and several stage schools offering lessons and hopes of theatrical glory to the tiny tots and pushy stage parents of Britain (‘Baby Terry’, p. 7; ‘Terry’s Juveniles’, p. 14; ‘Terry Triumphs’, p. 11). Terry’s Juveniles was also the preferred source of panto babes for Emile Littler and he would regularly feature troupes of Terry Children dancing and singing their little hearts out in his shows. For Aladdin, Terry’s Juveniles provided a troupe of 24 ‘babes’ who coaxed collective oohs-and-aahs with their cute antics and what one critic termed “simple but effective ensembles” (Beaumont, p. 7). Though demand for its brand of hyper-trained child choruses was dwindling, Terry’s Juveniles continued into the 1960s before finally closing in 1968. Miss Terry passed in 1973 (‘Obituary’, p. 19)

With the cast in place, rehearsals for Aladdin started in mid-November at the London Casino. The Littler revue, Latin Quarter of 1951, was still playing till the end of the month so the cast performed in the rehearsal space before moving onto the stage proper in the first week of December. With a fixed holiday run of just a few months, pantos in this era didn’t usually hold previews. However, Aladdin did host a special ‘charity preview performance’ on Tuesday, 18 December, the day before its official opening, in aid of the King George’s Fund for Sailors with Lord and Lady Mountbatten in attendance (‘Events’, p. 13). Public performances of Aladdin started the following day on Wednesday 19 December.

Aladdin was the first of the big West End pantomimes to open for the 1951 season and it attracted a good deal of critical attention. For the most part, reviews were positive, even glowing, with particular praise for the principals, including Julie who was singled out for her glorious singing. Below is a sample of excerpts from reviews of Aladdin in some of the major publications:

The Times: “The pantomime season opens with a flash and a bang...Mr Emile Littler’s Aladdin admirably satisfies the requirements of this strange form...It provides a beautiful principal boy (Miss Jean Carson)...It gives us a fresh and unspoilt principal girl (Miss Julie Andrews) who can sing. It offers once again in Mr Nat Jackley a Dame who upholds the best comic traditions of a famous race” (‘London Casino’, p. 6).

Variety: “First of the West End pantomimes was Emile Littler’s London Casino production of Aladdin. His 11th London effort, this show...looks big with all the essential elements of a successful holiday show. Spaciously mounted and laced with ample comedy, Nat Jackley clicks as Widow Twankey and Jean Carson...makes a spirited boyish figure of Aladdin. Julie Andrews, 16-year-old, proves a delightful vocalist as the Princess” (’International’, p. 13).

Daily Telegraph: “Emile Littler’s Aladdin [is] one of the best shows of its kind for years. It has everything you want...: a glittering spectacle, good singing, a certain amount of dancing, just enough story, and plenty of rich fruity comedy...Julie Andrews, a very young Princess, is...impressive [with] the range of her singing...A first rate show” (Bishop, p. 3).

The Stage: “[T] his is uncommonly good entertainment -- the best...of ‘Emile Littler’s eleven London laughter pantomimes’. In Nat Jackley and Jean Carson it has a dame and principal boy of exceptional quality...Young Julie Andrews sings with almost operatic power and beauty” (’Christmas Shows’, p. 5).

The Sketch: “Aladdin, elaborate and pictorial,...chunners along blithely, thanks to Nat Jackley’s Dame, a contorted giraffe. And Julie Andrews has the best singing voice in the three main pantomimes” (Trewin, p. 55).

Daily Mail: “Emile Littler’s 11th London pantomime, gay without being gaudy,...is triumphantly British and pantomimic...Jean Carson is as jaunty and glamorous as a redheaded Aladdin as you could wish, and 16-year-old Julie Andrews, as the Princess, sings with a faintly puzzled air, as if sharing our surprise that such a powerful voice should emerge from such a petite throat” (Wilson, p. 5).

West London Observer: “Emile Littler’s eleventh annual pantomime, Aladdin (London Casino) seems rather like a rolling snow-ball to have got larger and larger during its passage through the years. The present panto has 15 spectacular scenes, irrelevant diversions -- clowning, acrobatics, and what-not -- not to mention Mr Littler’s own version of the Aladdin legend. This has Nat Jackley as Widow Twankey -- great fun in the best and broadest style -- and Jean Carson as a cute Aladdin...Julie Andrews and Martin Lawrence supply fine singing voices” (‘Spectacle’, p. 6).

Daily Worker: “Emile Littler’s production...really succeeds in telling an honest story tunefully, colourfully, cleanly and well...Nat Jackley of the rubber-neck made an extraordinarily attractive as well as funny Widow Twankey. The splendid singing of Martin Lawrence, Jean Carson, and Julie Andrews set a first-rate standard” (D.D., p. 3).

News Chronicle: “This, the first pantomime of the London season, is an affair of genuine gaiety and glitter...It has an unusually dainty Widow Twankey in Nat Jackley (who, moreover, has never been funnier), an unusually audible Aladdin in Jean Carson, [and] an unusually musical Princess in Julie Andrews” (Dent, p. 3).

The Sphere: “Mr Jackley as the Dame upholds the best comic traditions of pantomime, giving us a ludicrous parody of beauty with flashing eyes, raven hair and an air of roguishness. Julie Andrews, as the principal girl, is in excellent voice” (‘Aladdin and Humpty Dumpty’, p. 3).

Birmingham Gazette: “The stage gleams and sparkles in this production of Aladdin...Jean Carson is a gallant principal boy and Julie Andrews a strong-voiced principal girl” (‘London Letter’, p. 4).

Any Littler panto was assured of a popular reception but these excellent reviews helped make Aladdin a smash hit of the 1951 Christmas season. It played to packed houses right throughout its two-and-a-half month season closing on 23 February after 103 performances. Theatregoers who couldn't get tickets to the show weren’t left completely unsatisfied as excerpts from Aladdin were recorded and broadcast as a special half-hour radio programme on the BBC on January 3 1952 (‘Light Programme’, p. 33). It is not known if this recording is still in existence but what a treat it would be to hear it.

References:

‘Accent on Comedy in New Pantomime.’ Coventry Evening Telegraph. 10 October 1950: p. 4.

‘Aladdin and Humpty Dumpty: The lure of the pantomime.’ The Sphere. 5 January 1952: p. 3.

Andrews, Julie. Home: A memoir of my early years, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2008.

Ashton, Ellis. ‘Music Hall Miscellany.’ The Stage and Television Today. 1 June 1978: p. 4.

A.T. ‘Feast on Pantomime Opens in Leeds.’ The Yorkshire Post. 24 December 1949: p. 6.

‘Author! Author!’ The Sketch. 16 January 1952: p. 60.

‘Baby Terry.’ The Coventry Herald. 19 August 1932: p. 7.

Beaumont, Cyril. ‘Ballet in Pantomime.’ The Sunday Times. 30 December 1951: p. 7.

Bishop, George W. ‘Theatre Notes: West End plans for pantomime.’ Daily Telegraph and Morning Post. 29 October 1951: p. 6.

‘Boy Acrobat from Coventry, The.’ Coventry Evening Telegraph. 29 February 1952: p. 11.

Chang, Dongshin. Representing China on the Historical London Stage: From orientalism to intercultural performance. London: Routledge, 2015.

‘Chit Chat.’ The Stage. 3 January 1952: p. 18.

‘Christmas Greetings.’ The Stage and Television Today. 16 December 1982: p. 40.

‘Christmas Shows: Casino Aladdin.’ The Stage. 3 January 1952: p. 5.

‘Christmas Holiday Shows: The Casino Goody Two Shoes.’ The Stage. 29 December 1950: p. 5.

‘Concert Notes: Opera to pantomime.’ The Stage. 22 November 1951: p. 6.

D.D. ‘Vintage Year for Panto: Aladdin.’ Daily Worker. 20 December 1951: p. 3.

'Debroy Somers.’ The Stage. 29 May 1952: p.3.

Dent, Alan. ‘It’s Gay and Glittering.’ Daily News. 20 December 1951: p. 3.

Dixon, Stephen. ‘Nat Jackley: 100 funny walks.’ The Guardian. 21 September 1988: 39.

Elmes, Simon. Hello Again: Nine decades of radio voices. London: Random House, 2012.

‘Emile Littler Sends Greetings.’ The Stage. 20 December 1951: p.5.

Emile Littler Souvenir, The. London: Dewynters Ltd, 1953.

E.M.M. ‘Comedy Pair Great Fun.’ Derby Evening Telegraph. 31 August 1948: p.2.

‘Events from our Social Diary.’ The Sketch. 2 January 1952: pp. 12-13.

From, Gerald. Oh, Yes It Is: A history of pantomime. London: BBC, 1985.

Hainaux, René. Stage Design throughout the World since 1935. London: Harrap, 1965.

‘Hastings Mann’, The Stage. 14 May 1964: p, 3.

Hobson, Harold. "Christmas Shows." Sunday Times, 23 December 1951, p. 2.

Holloway, Tony. ‘Stage a Big Bouquet for “Cactus” Couple.’ The Pantagraph. 1 March 1969: p. A-7.

‘International: London Pre-Xmas Stage Prems Hit Best Since May; 'Crook' Looms Okay.’ Variety. 185 (3), 26 December 1951: p.13.

‘Jean Carson Makes TV History.’ The Stage. 10 March 1955: p. 11.

‘Jimmy Clitheroe.’ The Guardian. 7 June 7, 1973: p. 5.

Johnson, Gill. ‘Research reveals life of “Clitheroe Kid”.’ Lancashire Telegraph. 17 May 2007: p. 12.

Knox, Collie. ‘Candid Cameo: Emile Littler.’ The Sketch. 10 December 1947: p. 314.

Konig, George. ‘Prelude to Christmas: The panto factory.” The Sketch. 23 November 1949: p. 450-51.

‘Light Entertainment.’ The Stage and Television Today. 30 September 1976: p. 3.

‘Light Programme: Thursday 3 January.’ Radio Times. : p. 33.

Lloyd-Williams, Anne. ‘Physhe surprised the Americans.’ Birmingham Gazette. 24 January 1952: p. 4.

‘London Casino: Aladdin.’ The Times. 20 December 1951: p. 6.

‘London Letter: Littler and good.’ Birmingham Gazette. 21 December 1951: p. 4.

M.M. ‘Manchester Hippodrome: Jack and Jill.’ Manchester Evening News. 24 December 1948: p. 3.

‘Martin Lawrence.’ The Musical Times. 124: 1684, June 1983: p. 378.

‘Nat Jackley.’ The Stage and Television Today. 13 October 1988: p. 35.

News Chronicle Reporter. ‘Aladdin loses his hat.’ Daily News. 20 December 1951: p. 3.

‘Obituary: Miss Terry.’ The Stage.15 February 1973: p. 19.

Pedrick, Gale. ‘Emile Littler: Producer of two hundred pantomimes’, The Stage, 19 December 1957: p. 8.

Percival, John. ‘Backward Glances: The Metropolitan Ballet.’ Dance and Dancers. February 1960: pp.20-22

‘Principal Girl in Aladdin.’ Daily News. 15 December 1951: p. 5.

‘Provincial Pantomimes.’ The Stage. 31 December 1948: p. 8.

Rasmussen, Frederick N. ‘Harry R. Rosofsky dies at age 90.’ The Baltimore Sun. 11 September 2010: p. A14.

Reilly, Kara. ‘The Tiller Girls: Mass ornament and modern girl.’ In Theatre, Performance and Analogue Technology: Historical interfaces and intermedialities, K. Reilly, ed. Houndmills: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013: pp. 117-132.

Rosen, Gary. Frank Staff and his role in South African ballet and musical theatre from 1955 to 1959. Dissertation. University of Cape Town, 1998.

‘Ross and budgerigars arrive.’ Evening News. 7 December 1951: p. 1.

Seattle Rep. ‘Remembering Biff McGuire.’ SeattleRep.org. 1 April 2021 <https://www.seattlerep.org/about-us/inside-seattle-rep/remembering-biff-mcguire/>

‘Seven-and-a-half Pantos’. The Stage. 16 October 1952: p. 3.

‘She Gets TV Chance.’ Daily Herald. 9 July 1951: p. 5.

Short, Edgar. London Theatre, 1919-1949. London: Wiseman, 1983.

‘Spectacle Galore!’ The West London Observer. 28 December 1951: p. 6.

Stevenson, W.B. ‘Show Piece: Pre-London tryout for new show.’ Nottingham Journal. 18 February 1953: p. 4.

Storey, Basil. ‘The Windmill Tilted.’ Speedway Gazette. 4 December, 1948: pp. 4-5.

Taylor, Jeffrey. ‘Obituary: David Davenport.’ The Stage. 7 December 1995: p. 36.

‘Terry’s Juveniles.’ The Era. 30 March 1921: p. 14.

‘Terry Triumphs.’ The Era. 28 May 1930: p. 11.

‘Theatre Fare.’ The Courier and Advertiser. 24 December 1951: p. 3.

Trewin, J.C. ‘The Pantomimes.’ The Sketch. 16 January 1952: p. 55.

Tucker, David C. Lost Laughs of '50s and '60s Television: Thirty sitcoms that faded off screen. Jefferson, N.C: McFarland, 2010.

‘Variety News: Desmond and Marks welcomed behind ‘that’ curtain.’ The Stage. 11 October 1956: p. 3.

Varty, Anne. Children and Theatre in Victorian Britain: ‘All work and no play.’ Houndsmill: Palgrave MacMillan, 2008.

‘Walter Crisham.’ Plays and Players. August 1985: p. 53.

Waters, Bill. ‘Forsooth! Here cometh Biff and Jeannie.’ Miami News Entertainment Section. 5 April 1964: p. 3.

Wearing, J.P. The London Stage 1950-1959: A calendar of productions, performers, and personnel. London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014.

Wilson, Albert Edward. Pantomime Pageant: A procession of harlequins, clowns, comedians, principal boys, pantomime-writers, producers and playgoers. London: S. Paul & Co, 1946.

Wilson, Cecil. ‘Aladdin Is Gay but Not Gaudy.’ Daily Mail. 20 December 1951: p. 5.

Copyright © Brett Farmer 2021

#julie andrews#aladdin#pantomime#british theatre#emile littler#theatre#west end#london casino#1951#70th Anniversary

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

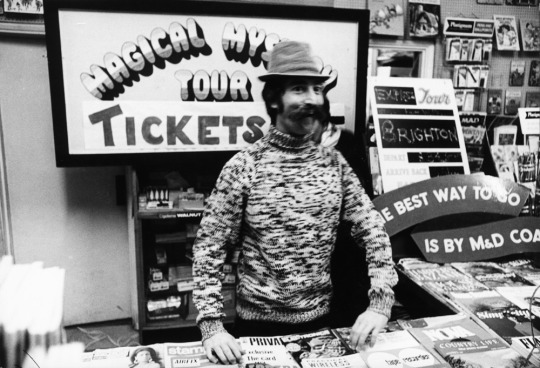

PHOEBE: So in this clip, Paul mentions Ingmar Bergman's Seventh Seal, and Jean Luc Godard's One Plus One. He talks about his love of films, especially experimental films, and basically being a student of film in the mid 60s. We also know from his 1997 biography, Many Years From Now, that in the mid 60s, particularly in that ‘66 through ‘68 era, he screened a few indie films at his house in London. I know that he had a screening of Scorpio Rising by Kenneth Anger, and another of Andy Warhol’s, Empire. And in the Michael Braun book, Love Me Do from 1964, Paul mentions the Trial (Orson Welles movie), and 8 1/2. So we've a pretty good sense of Paul's movie background in 1967 going into the making of Magical Mystery Tour. He's mentioned Bergman, Godard, Fellini, Truffaut, Orson Welles, Andy Warhol and also Dick Lester and British comedy, such as Morecambe and Wise. And Nat Jackley (the comedian that John loved who got into the movie). And we know that Paul been making his own short films for a while by the time that he conceived of the Magical Mystery Tour project. So he's made short films and he knew enough basic filmmaking, like he knew how to rewind the film and expose it again. He liked making double exposures and fun stuff that was becoming more popular in the 60s; artsy little tricks.

KRISTEN: Well, you know, what I think is interesting about Paul's influences that you mentioned, like these great European art cinema directors like Bergman and Fellini...and then you've got the new wave directors, the experimental. And even the American director that you mentioned, Orson Welles isn't, like, run of the mill American director, like he's the artsy one, right?

But what I think is really interesting is that in the 60s, that was a pretty standard mix for people who are really into film culture, like new wave and European art cinema directors. I'm surprised he doesn't throw Kurosawa in there, because that's kind of in the mix, right? Or Buñuel. But that group of directors, art cinema directors from the 1950s and then the new wave, specifically the French New Wave directors from the 50s and 60s, were so a part of film culture at the time, in the 1960s. Like all of the 20-somethings, you know, the people Paul's age, were definitely really getting into film culture at this time.

You had cine clubs, movie clubs popping up all over the world. They were really, really important in France, but in England too, they would have been really popular. And definitely like, college campuses in the US, college-age students would get together and they would watch the latest -or not even the latest, but they would watch The Seventh Seal or they would watch, Rashomon or whatever, and then they would discuss it. And it would be, sort of this thing where, like in France, these cine clubs were supported by the government. I mean, it was a sanctioned thing. PHOEBE: They still are (in France)! KRISTEN: Right, right. And so, you know, it was really, really popular.

And then experimental films were thrown into the mix too. And so you had these kind of pop-up theaters or movie clubs, independent theaters and college campuses. You had this real film culture in the post war era, and really coalescing in the 1960s with college age people and Paul - even though he's not a college student - he's in that kind of spot, that sweet spot, age-wise. So it absolutely makes sense that he's doing this and it's not even, like, super unique or unusual. This is something that a lot of (especially 20-something) artists and intellectuals were absolutely doing. And you know the fact that he's showing Kenneth Anger and Andy Warhol, like he's definitely showing the cutting edge sort of pop culture, experimental filmmakers, which is pretty cool. You know, he's not showing like, Stan Brakhage or Maya Deren- like, maybe he is? But he's not showing the ones that are maybe a little bit more challenging. He's showing the ones that are a little bit more accessible, which is great, though! Like those are, they're fantastic, like Kenneth Anger is amazing.

I think that he's just so a part of that moment, that late-60s sort of film culture, experimental film culture moment. And it’s just starting to seep into Hollywood at this time. And this sort of counterculture interest in experimental and new wave and art house filmmaking is about to completely change Hollywood and give us new Hollywood. And so, you know, he's right on track at this time, as far as youth film culture, which I think is really cool.

Full episode here

61 notes

·

View notes

Quote

They were big tall concrete structures that we could get people up on the top of, waving their arms. We gave people rubber egg-head skull caps, and we had a walrus. It was all directly from Alice in Wonderland, the walrus, the carpenter and all that surrealist stuff. John had just written 'I Am the Walrus' and it was decided therefore it should go in the film. It is one of John's great songs and it is very Lennon. Even now I'm a bit shy to say I was the director of Magical Mystery Tour although it was the fact: it was me that was first up in the morning, me that virtually directed the whole thing. So being the de facto director, I would go and say good night to everyone. Just to check on the team. I was saying good night to John in the hotel in Cornwall and saying thanks for doing the Nat Jackley thing. I was standing at the door and he was in bed, and we were talking about the lyrics of 'I Am the Walrus', and I remember feeling he was a little frail at that time, maybe not going through one of the best periods in life, probably breaking up with his wife. He was going through a very fragile period. You've only got to look at his lyrics - 'sitting on a cornflake waiting for the van to come'. They were very disturbed lyrics.

Paul McCartney, in Barry Miles’ Many Years From Now (1997).

-

The recording of John's 'I Am the Walrus' began on 5 September. [...] Recorded only nine days after Brian Epstein's death, John sounds in real pain: 'I'm crying!' Far from being light-hearted nonsense verse, John's lyrics are a desperate howl of frustration.

— in Barry Miles’ Many Years From Now (1997).

-

We all went through a depression after Maharishi and Brian died; it wasn’t really to do with Maharishi, it was just that period. I was really going through the “What’s it all about?” type thing – this songwriting is nothing, it’s pointless, and I’m no good, I’m not talented, and I’m shitty, and I couldn’t do anything but be a Beatle. What am I going to do about it? It lasted nearly two years and I was still in it during Pepper. I know Paul wasn’t at the time; he was feeling full of confidence, and I was going through murder during those periods. I was just about coming out of it around Maharishi, even though Brian had died – that knocked us back again. Well, it knocked me back.

— John Lennon, interviewed by Barry Miles, (partially) unpublished (23 September 1969).

#I Am The Walrus#Songwriting is like psychiatry#Lewis Carroll#The Surrealist#magical mystery tour#i was feeling insecure#But every now and then I feel so insecure I know that I just need you like I've never done before#the person i actually picked as my partner#macca#johnny#Cynthia#Brian Epstein#2nd verse#1967#elision#1969#solo#quote#my stuff

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paul Roundhill

back story PAUL N. ROUNDHILL, MULTI-MEDIA ARTIST, PHOTOGRAPHER, WRITER… “Paul Ro”, “The Professor”, after leaving school Paul started out as an assistant stage manager for the last Summer Variety “Music Hall” Show at the Palace Pier Theatre on Brighton’s Palace Pier. He worked with some of the great names from that lost era including as a stooge for Rubber Neck Nat Jackley (Happy Nat in the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Apuntes, El Viaje Magico y misterioso de los 4 Beatles

Por: Guillermina Rodriguez Velasco

1967-UK-55 min. : Comedy/Musical.

Director: The Beatles, Bernard Knowles.

Guión: The Beatles.

Dirección de fotografía: Ringo Starr.

Montaje: Roy Benson

Banda Sonora: The Beatles, The Bonzo Dog Doh-Dah Band.

Producción: George Harrison, John Lennon, Gavrik Losey, Paul McCartney, Denis O'Dell, Ringo Starr.

Reparto: John Lennon (John Lennon, narrador, Mago), Paul McCartney (Paul McCartney, Major McCartney, Mago), George Harrison (George Harrison, mago), Ringo Starr (Ringo Starr, mago), Maggie Wright (Starlet), Mandy Weet (anfitriona), Derek Royle (Jolly Jimmy), Victor Spinetti (Sargento del ejército), Jessie Robins (tía de Ringo), Nicola Hale (Nicola), Shirley Evans (acordeonista), George Claydon (fotógrafo), Jan Carson (Stripper), Nat Jackley (Rubber Man), Ivor Cutler (Mr. Bloodvessel), The Bonzo Dog Doh-Dah Band.

Magical Mystery Tour es una roadmovie de los 60s producida, musicalizada, fotografiada, escrita y dirigida por The Beatles. Esta película plasma con exactitud la psicodelia y su fuerte influencia en la vida cotidiana de los individuos, desde los más jóvenes hasta los más grandes y plantea que cualquier situación por más rutinaria que esta sea tiene algo de irreal, surreal, fantástico, mágico y misterioso.

En 1967, The Beatles se dieron cuenta de que ya jamás podrían volver a dar presentaciones en vivo, traían un Sgt. Peppers en la espalda que los colocó en un lugar muy alto dentro de la industria musical, sus composiciones ya contaban con un sinfín de arreglos y sonidos que difícilmente se podrían tocar en vivo, por ello la manera más fácil para acercarse a sus "fans" y hacerles llegar su música fue la televisión.

Para esta época, los 4 Beatles ya llevaban tiempo enviando pequeños videoclips a los programas de tv para ser transmitidos entre la programación a manera de comercial o mini película. Ya para estos tiempos tenían dos películas, también, A Hard Day’s Night y Help!, sin embargo, tanto las películas como los clips eran cosa de los viejos Beatles con mop top y Chelsea boots, era hora de hacer algo nuevo y experimentar.

Así surgió la idea de hacer una película, sin embargo nadie quería dirigir tal cosa; ni guión tenia, ¿Cuál fue la solución? Los 4 Beatles iban a dirigir, producir, escribir, actuar, musicalizar y editar su propia película; muchos pensaron que sería una pérdida de tiempo y dinero, pese a esto se inició la filmación del Magical Mystery Tour.

Poco les importó aventarse a hacer una película sin ser expertos en la materia, para solucionar el problema del director John Lennon y Paul McCartney trazaron un circulo en una hoja de papel y a su vez lo dividieron como si fueran los rayos de una bicicleta o rebanadas de pizza, en cada triangulo se fue poniendo que escena se filmaría, esta sencilla manera controló el orden y la dirección de todo el proyecto. Lo demás ya lo tenían casi hecho, sabían de memoria las escenas y los guiones serían improvisados sobre la marcha, la música estaba lista, se alquiló un autobús serigrafiado de último momento; resolvieron el problema de escenarios filmando en carreteras y hangares para aviones, en cuanto a los actores recurrieron a la guía de actores Spotlight, algunos de los actores no estaban del todo convencidos por la falta de guion, en especial los actores que toda su vida habían trabajado de manera muy seria y no estaban acostumbrados a trabajar en estas condiciones.

Paul era el encargado del trabajo de edición y montaje, debido a su falta de organización y conocimientos, la realización de la película se atrasó y se detuvo. La situación empeoró por la ausencia de claquetas y dificultades para pegar las canciones en las escenas que las requerían, aunado a esto, ya durante la edición se percataron apenas que no tenían escenas del autobús visto desde el exterior y en movimiento, todas las escenas del autobús eran en el interior, lo que evidenciaba una película inconexa. La filmación solo llevó once semanas, por los problemas de edición y montaje, no solo se llevó más tiempo, también mucho más dinero del que incluso se le invirtió a la misma filmación

Los más allegados a los Beatles y encargados de su desarrollo profesional, al ver el producto final sugirieron que sería mejor guardarlo como un bonito recuerdo y nada más, no les parecía buena idea darle difusión a una película de ese tipo, el público no estaba preparado. Cabe recordar que este sería uno de los primeros proyectos Beatle donde no estaría Brian Epstein, su manager quien acababa de fallecer. Para los Beatles esta película seria el inicio de una época de incertidumbres, de encontrarse perdidos y tratar de sacar avante el grupo sin ayuda de quien tantos años los ayudó y prácticamente les resolvió la vida profesional, así que frente a toda opinión, Paul comenzó la difusión del Magical Mystery Tour.

La película se transmitió el 26 de diciembre en la BBC1, día en el que se solía transmitir el Music Hall, después de navidad fue un golpe tremendo tanto para las familias y espectadores como para la crítica cinematográfica, todos sin excepción consideraron que la película era una aberración y se vaticinó lo peor para los cuatro Beatles, aunque el álbum llego a número uno en listas de popularidad, la película generó mucha polémica respecto al futuro artístico de la banda. Uno de los principales errores fue que la película se transmitió en blanco y negro, siendo el color su principal característica y atractivo, fue meses después de todo este zafarrancho que se retransmitió la película a color y sólo algunos cambiaron su opinión.

Actualmente ha pasado a la historia como una película de culto, algunos afirman que se trata de los primeros videoclips de larga duración e incluso se ha llegado a catalogar a la película como un buen ejercicio de improvisación fílmica y un trabajo artístico. Lo que es cierto es que los Beatles retrataron de manera elocuente la cotidianidad, las costumbres y formas de vida tanto de jóvenes como adultos ingleses de aquellos años, en esta película podemos apreciar como estaban sintiéndose cada uno de los cuatro Beatles porque principalmente eso es lo que lograron capturar, sus miedos y anhelos, su sentir en ese preciso momento y su manera de ver la realidad.

0 notes

Photo

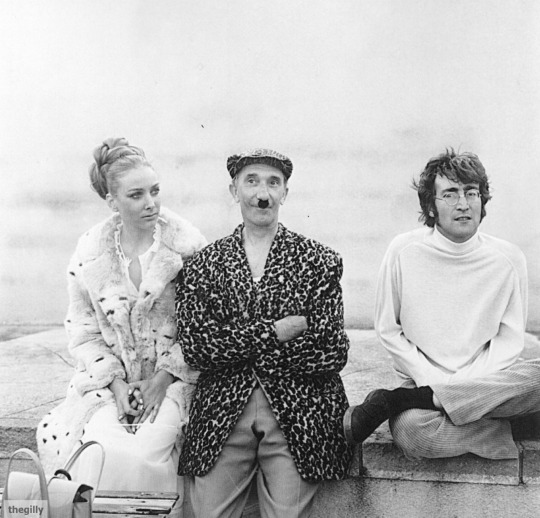

John and Nat Jackley during the filming of Magical Mystery Tour, 13 September 1967. Scan from “The Making of the Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour” by Tony Bramwell.

Does anyone know the name of the woman?

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

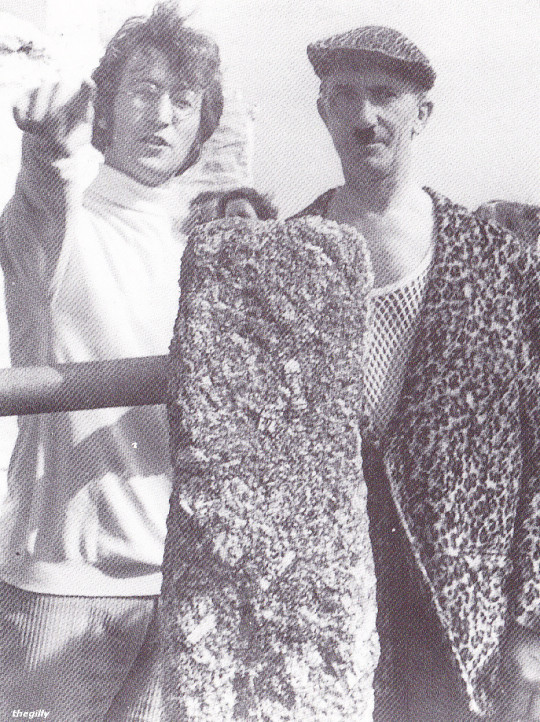

John directing a scene with Nat Jackley for Magical Mystery Tour, 13 September 1967

6 notes

·

View notes