#my back blog needs a big time revival after all this era has provided

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

📸: Mati Ficara

#obviously this was going to be its on post come on#5sos#5 seconds of summer#ashton irwin#ashton#ai live at the belasco#kh4f post#😍👄😍#my back blog needs a big time revival after all this era has provided

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Thornton Heath Poltergeist - The Most Haunted Places In The World That You NEED To Hear About #2

January.

A time of self doubt as you take on the latest fad diet. A time of personal struggle as you return to the 9-to-5 and question why in the hell you decided to work in this goddamn office. And a time of thirst as you realise Dry January does indeed include Echo Falls despite their Rosé being mostly sugar and aesthetic.

Is there any hope left in the world?

Oh, dear reader - you didn’t tap on this blog in the hope of reading some article about a cheerful, positive topic like little rabbits with big flopsy ears, did you?

You’re here for the dead. And the demonic. And all manner of terrible things.

Goodbye, Patches - hello, Poltergeist.

Today, we are going to be discussing one of the most iconic paranormal cases from the UK that no one has ever heard of: the Thornton Heath Poltergeist.

But it turns out that there’s not just one poltergeist in Thornton Heath.

Oh, no.

There’s two.

And these two pesky spirits are far from alone:

Croydon might not sound like the setting for the next cult horror hit, but this London borough is actually known for its rather macabre history - and the legacy of its dark past.

Whilst your chowing down on a Gregg’s sausage roll you might hear rumours of one of Elizabeth I’s maids-in-waiting traipsing around a school, and perhaps you’ll even see a few children who were killed during the war skip past the local Chicken Cottage.

On top of that - like most areas of London - Croydon is actually a relatively ancient town, with the first settlements appearing in the 6th century.

This place clearly has a lot of paranormal promise.

However, despite setting the scene for 2 key cases of poltergeist activity, though do appear to be unconnected. Nevertheless, together they provide a lot of insight into a specific form of supernatural activity that tends to get forgotten.

This is especially true since poltergeists have dominated the horror genre for many a year, inspiring iconic films such as Poltergeist (1982), and litter stories which involve any trace paranormal activity.

The thing is, although frequently mentioned, the actual concept of poltergeists is kind of ignored, particularly the debate surrounding them. These 2 cases, however, provide an overview of the different approaches to poltergeist activity:

One case looks into debunking the paranormal, whereas the other presents the typical haunted house case you clicked to see.

So, today’s article is going to take us through the 2 poltergeists of Thornton Heath, and the paranormal theory behind poltergeists.

Strap in folks, and let’s get spooky.

First, What Actually Is A Poltergeist?

Anyone speak German?

Poltergeist is a mashup of two German words, and it literally means “noisy spirit”.

Based on that translation, it is a type of spirit who has a thing for physical disturbances. Loud noises, objects moving, biting and pinching are the common symptoms of such a haunting. And despite sounding pretty minimal - well, maybe not the biting and the pinching - such poltergeist activity often represents the first traces of far greater hauntings.

But unlike most paranormal theories, it turns out that poltergeist activity is pretty well investigated (as this post will demonstrate).

Heck, poltergeist activity has been reported since the 1st century!

It is claimed that it lasts typically around 5 months, but some say it can stretch out to several years.

On top of our knowledge of the duration of such activity, poltergeists allegedly haunt people, not places - a bit like demons. This does contrast with the 1972 haunting, but we all know that supernatural theories lack the accuracy we expect of an exact science.

And so we come back to the debates and the debunking which always ends up stalking the supernatural. It’s for that reason that Poltergeists are such a valuable component of spiritualist theory because of the intense debate and study surrounding them, as the 1938 case will show.

Indeed, the first of the scientific theories debunking poltergeists swap the paranormal for the patriarchy.

It's called the Naughty Little Girl theory.

Obviously, it suggests that young girls create activity to get attention because women can’t breathe without doing it for attention, right? The Conjuring 2 is one of the few films that picks up on this concept, showing its use by the media as it was utilised in the real life case.

A less misogynistic theory instead claims that the paranormal activity could be down to seismic activity or water stress, creating noises and physical disturbances often blamed on poltergeists.

Or, it could all come back to the theory of psychokinesis:

It claims that when we are stressed, our fucked-up brains can have a physical impact on the objects around us, making it look - and feel - like we are living in a perpetual Paranormal Activity film.

Well, that or a rom-com; it turns out the poltergeist was really within us the whole time...

The 1972 Case - The Official Thornton Heath Poltergeist

Welcome to the the era of the occult - the 1970s.

The obsession with the paranormal experienced a revival in the late 20th century thanks to the affectionately named Satanic Panic and the rise of hippie-dom. And because so many reports of the paranormal crop up in this era, we have to be wary – blaming shit on the paranormal was nearly as common as institutionalised racism, ensuring that claims were often amped up by fear.

Got your pinch of salt to hand? Good.

Our story begins in the heat of summer - it’s August 1972.

A family are fast asleep after, well, I don’t know, what did people do in the 1970s? Listen to too much ABBA?

Anyway - their peaceful slumber is interrupted in the middle of the night when a radio switches on all by itself and blasts out full-volume-raise-the-roof level musings from a foreign radio station.

This is where the activity begins.

The following nights, lights turn on and off by themselves, mirroring the first hour of a Paranormal Activity film before Katie makes some off the cuff comment about being besties with a demon during puberty.

Yet despite the suggestions of something supernatural, it suddenly just chills the fuck out.

Well, that is until the most wonderful time of the year! Only for this famalam, this are about to get a little less wonderful, and a little more what the fuck.

Probably in the midst of an ABBA jam-sesh, a small antique figurine is plucked off a shelf by an invisible hand, and flung across the room, hitting the patriarch of the family with such a force that it knocks him to the floor.

If that wasn’t enough for one day, the Christmas tree then joins in the freaky festivities, and starts shaking.

And that only just scratches the surface of the supernatural events soon to haunt this family.

Cut to a few days later, and its New Year Eve.

Ok, right, let’s be honest here: any activity reported was at times when there would have been a couple of bevvies, a few late nights among friends and family…

Who hasn’t seen a demon picking cashews out of the mixed nuts bowel when they’re a third of the way through that bottle of Echo Falls?

Regardless of my suspicions, they supposedly started to hear loud footsteps upstairs, and during that very night, a member of the family awoke to see a very tall and very angry man staring at him, giving off very threatening vibes.

But it wasn’t just the son of the family that saw these mysterious goings on.

Some visitors to the house reported similar activity:

At a dinner party (*sigh*) a door began to violently shake, nearly coming off its hinges. The living room door then followed suit, and swung open. Every single light in the house then began to follow the trend and turned on and off.

No matter how many bottles they were deep by then, there’s no doubt that shizz was getting weird.

In response to this shizz getting weird, the family did the right thing: they called themselves a priest, and got him to check the shizz out.

However, as a result of his holy presence, the activity worsened. A medium shortly followed, and on his visit deduced that this was a farmer of Chatterton. A quick visit to the library and a rifle through the odd archive later, and the story is confirmed:

This was the spirit of a farmer from the 18th century, and as the medium claimed, he was angry that these trespassers were on his land. So, like all landlords, he kept his cool and was trying to treat these people with the fairness and respect that all landlords hold dear.

Nah, who are we kidding - instead of charging them £60 for not pulling a weed out from underneath the wheelie bin, he manifested as a poltergeist.

The escalation then, uh, escalated.

Following the appearance of the ghost patriarch, his wife then turned up and made a point of targeting the matriarch of the family.

Despite the coincidence of most claims of boozy nights on the heath, these hauntings that mirror the heads of the household really support the case as it sticks to this line of opposition to the “intruders”.

The ghostly matriarch’s favoured haunting was following people up the stairs; when you turned around, you would see wisps of a grey bun and the outlines of a faint figure which would then vanish into thin air.

But on top of the wife getting involved, the farmer himself made a commitment to being spooky AF.

Its for that reason that the creepiest haunting of the year award goes to the farmer.

Why?

Because he would turn up on their TV.

Like, I don’t know if he was on bloody Blue Peter à la IT, or if the screen would go blank and this bitch would rock up and just be there…

But just like fuck that, no thanks, congratulations, and just take the award ugh.

So, like anyone would, this family were like nope screw this, packed up shop, and moved the fuck outta there. After they moved out the activity ceased - like all hauntings tend to do, confirming that it could be due to their trespassing.

Well, or that it was all faked but as the gullible young woman I am, I’m going to deny all traces of this family’s excessive drinking and say that the farmer did indeed turn up on Blue Peter and take a badge with him to the afterlife.

For privacy reasons, the actual address is unknown to the public for the obvious reason that innocent families don’t want some Jake Paul wannabe pulling up in a jacked up Ford Fiesta and whipping out a GoPro to make a quick buck on YouTube.

Heck, I don’t know if anyone lives there now! But this is still recognised by paranormal fanatics are one of the greatest hauntings to come out of the UK.

Well, I say the greatest…

It has to compete with the Thornton Heath poltergeist of an odd 40 years before.

The 1938 Case - Thornton Heath Poltergeist 2: The Prequel No One Asked For

Now we turn to the former haunting of Thornton heath in 1938.

But this poltergeist isn’t set against the scene of some cosy pre-war family home, nor are any long dead farmers getting involved.

This story, on the other hand, follows the scientific study of the paranormal, and to this day is an unsolved mystery that has left both investigator and individual alike without answers.

And it starts with this bloke called Nandor Fodor.

Fodor lead the argument that poltergeists are manifestations from the subconscious mind, and to prove his claims, he investigated the tales of terror that had been experienced by one woman in a small corner of Croydon.

He followed his scientific studies all the way to a little place called Thornton Heath.

Sure, this case could have been linked to the Chatterton farmer, but the focus of their investigation was on the nature of paranormal beliefs, so there was no study of what spirit could be behind it.

All we know regarding the haunting is that the victim of this poltergeist was a woman only known to us as Mrs. Forbes. She was studied at an institute, and in an attempt to be sure she wasn’t creating the hauntings, she basically had to get undressed in front of them, and wear special clothes to prove she wasn’t concealing anything.

Nevertheless, the weird shizz we saw in the 1970s still seemed to follow her.

Dishes would float in mid-air and then crash to the floor, glasses would suddenly appear in her hand (*insert middle aged facebook meme with a minion in the background*), and objects from her home would appear at the institute.

Her house was 10 miles away from the institute.

But beyond her possessions appearing out of thin air, Mrs. Forbes frequently described different entities that would appear and attack her.

These beings included a vampire which would on occasion bite her neck - and left her with two physical wounds in her neck, and a tiger which reached out and scratched deep gashes in her arm. Just like the vampire’s supposed attack, these markings were also found on her body.

However, one of her claims went too far, and was used to challenge every single incident she claimed was caused by a poltergeist:

Alongside the vampire bite and the tiger’s scratches, Mrs. Forbes also had several burn marks scarring her neck. Seemingly coming out of nowhere, Forbes believed it was due to the spirit of a man strangling her with a necklace.

However, shortly after making this statement, she professed a deep desire to kill this man.

Fodor drew from this that she thought the man was inside of her, and thus she tried to kill him by choking herself. That’s the burn marks explained - what about everything else? All it took was a quick check of her body and clothing to find small items concealed under her left breast.

That’s right; she has conjured up this “poltergeist” out of thin air.

Having connected the dots, Fodor deduced that she was both schizophrenic, and burdened by repressed sexual trauma.

Another day, another hoax.

Unsurprisingly, faked activity vis-a-vis this case is pretty common when it comes to the paranormal, and this label is pinned by non-believers onto, well, basically anything we just so happen to report.

And despite how frustrating this can seem, it is a necessary disturbance in our research of the supernatural. In fact, the original Thornton Heath story brings this into play when we discuss poltergeists, particularly as their basis centres on physical disturbances which can be both faked or misinterpreted.

Croydon might seem yet another area of London Prince Andrew would pull out of the hat to defend his reputation, but it instead represents a much wider discussion of the paranormal.

From the fake to the unknown, from the mysterious to the mentally unstable:

How we investigate the supernatural starts in a little place called Thornton Heath.

What do you think?

Did the family really witness poltergeist activity first hand?

Or was it all just conjured up by women that purely wanted attention i dont know about you but i just love attention oh gimme attention look I WANT ATTENTION NOWSUFH[HB’[Egb’???????!1//1/1/1!//????

Ahem.

Wanna hear about more spooky shizz like this? Wanna hear about a new haunted location everyday? Then go ‘head and hit follow!

#Thornton Heath#thornton heath poltergeist#poltergeist#ghosts of britain#great british ghosts#famous british ghosts#famous ghosts#famous haunted places#famous haunted houses#ghosts of america#ghosts#ghost adventured#ghost stories#scary stories#real ghost#zak bagans#spirit box#haunted places near me#most haunted places in the world#haunted house#haunting of hill house#mackamey manor#ghost sightings#most haunted#haunted netflix#borley rectory#the watcher house#scary house#scariest haunted house#things to do in london

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The right place, the right time, and the right amount of exclamation marks

The history of Vancouver via Abbotsford British Columbia’s You Say Party is a storied one. Imagine this: trapped in a never ending nightmare of suburban dystopian hell, you form a band. With the simple adjective of having fun, spreading a message, making people dance - you leave the confines of a religiously stifling community. Within a few years you’re playing the world’s top festivals, winning awards, and wooing critics.

But now I find myself piecing foggy bits of memory fragments together with duct tape and hairspray. Like stickers on a dive bar bathroom stall, I know I was there. But why and for how long? I feel like I’m sifting through a shoebox of handbills and press clippings like some True Crime podcaster placing myself at the scene.

I’m not sure where I first heard the name You Say Party! We Say Die! but it caught my eye. It was an era of exuberant band names. !!!, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Shout Out Out Out Out, Hot Hot Heat, Fake Shark- Real Zombie! And my own band GoGoStop! It was also a time when bands out Vancouver’s sleepy conservative suburbs were starting to break out: Witness Protection Program, The Hand, Fun100.

It was exciting. There was a sense of community. Of people just wanting to have fun. Perhaps we were shaking off the anxieties of a post 9/11 world, or shrugging off the self seriousness that was emo and hardcore. We still made mix tapes and zines- scoured Terminal City and The Straight for new bands. There was this new social networking craze called MySpace that had yet to be a ubiquitous omnipresent corporate behemoth that dominated every corner of our lives. We were called Scenesters not Hipsters. Everyone was in an art collective.

Adorned with white belts and one-inch pins; asymmetrical hair cuts and red velvet blazers we set out to prove Vancouver wasn’t No Fun City at now long shuttered venues like the Marine Club, the Pic Pub, and Mesa Luna. I didn’t drink at the time so dancing, and by extension dance punk, had become my saviour- bands like The Rapture, Les Say Fav, Pretty Girls Make Graves to name a few. When Mp3 blogs became a thing, I immediately downloaded The Gap from their 2005 debut Hit The Floor! and loaded it on my 100 song iPod shuffle. I like so many others, became an instant fan.

I moved into what could only be described as a punk rock compound- 3 houses that were owned by a former Christian sect that we dubbed Triple Threat. Members of Bend Sinister, No Dice, Witness Protection Program, and Devon Clifford from You Say Party and Cadeaux (and Whiteloaf) all lived there. He drove an orange 1981 Camaro Berlinetta to match his bright red hair and big personality. We would walk to the greasy spoon Bon’s Off Broadway to get terrible but cheap breakfast and to watch The coffee Sheriff pour undrinkable refills of sludge. It was like living in the movie Withnail and I, but funner. We all wore pins that said Do You Party? on them.

It felt like Vancouver was blowing up and You Say Party was the hand-clapping drum majorette leading the pack. Ladyhawk, Black Mountain, Radio Berlin, New Pornographers, Destroyer, S.T.R.E.E.T.S., The Doers, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? And The Organ highlighted just how tight-knit and diverse our scene was. Relentless touring and glowing reviews for You Say Party’s sophomore Lose All Time ensured they were head of the class, despite being unable to tour the US due to a previous border snafu.

Lose All Time sat on top of the Earshot charts for what seemed like forever. Famous for their frenetic live shows, and aided by stunning videos, their sophomore effort was a clear progression from Hit The Floor! It still harnessed the visceral rawness of their origins, but hinted at a confidence and maturity that was to come. The title of Lose All Time was a reference to the discombobulation of constant touring and it too was a hint of what was to come.

The touring would take its toll. Fuelled by Chinese Red Bull; a well document public dustup between band members at a bar in Germany would throw everything into uncertainty. But it was that turbulence that would set the stage for XXXX and after a restorative tour to China, the stage was set for the penultimate You Say Party record.

Flash forward to 2009 and the city was on edge. Everything was about to change. Vancouver was preparing to host the world amidst the unfolding Great Recession. Anti-Olympic protests ramped up. A gang war raged in the streets and made international headlines, tucked behind Swine Flu hysteria and the ongoing imperialist war on Iraq.

It seemed like all the venues started closing and all our friends were moving to Berlin or Montreal. We starting looking in. Is this the city we want? Was it just growing pains? This kind of introspection is clearly reflected in XXXX. If Lose All Time was a record the band wanted to make, XXXX was a record for the people; a record for the city of Vancouver; a record for 2009.

"I finally feel like a singer, rather than a dancer who loves being in a band" said Becky Ninkovic at the time. It’s a perfect quote. One that succinctly captures the maturity and focus of the record. After a breakdown for Ninkovic, a year of rest and vocal lessons, Exclaim! announced XXXX to be a career resuscitation.

And it was. Going back now and rediscovering the record is such a magical thing. Opening for You Say Party with my band Taxes in 2008, I was impressed with the new material even if was a little jaded (I mean I was almost 30). But now with time and space I can see the songs they were working on were truly timeless. Laura Palmer’s Prom could so easily slot in with the latest 80s synthwave revival along alongside bands like Lust for Youth, Lower Dens, and Chromatics.

Overall, XXXX sounds like an exhale. A moment of stillness when you know you’ve made something extraordinary. When you know all those moments combined; moments of sheer terror, adrenalin, elation, boredom, and longing- culminate in a piece of art that once you let go of it- you just know in your gut that it’s right. It draws you in, wrestles with a brooding tension, then sends you into a churning whirlwind of tight drums and buzzing synths. It’s a remarkable achievement.

There’s plenty of vintage YSP sass throughout. “She’s Spoken For”, “Make XXXX”, and “Cosmic Wanship Avengers” are all classic synth punk gems, but the it’s in the subdued that the album really grips. “Dark Days”, “There is XXXX (Within My Heart)” and the sprawling Kate Bush like ballad “Heart of Gold” are the hallmark of a band that is comfortable exploring the limits of their genre. While lyrically quite positive, the melodies are daunting. Indeed, as Pitchfork put it, “the slower pace and more sentimental outlook of XXXX gives listeners the necessary space and encouragement to surrender to the band's emotional message”.

And it was a message they would finally return to the US with in 2009. The band was poised for mainstream breakout success. They were long listed for the Polaris and they won a Western Canadian Music Award for Best Rock Album of the year. Much has been written about what would happen next. I don’t want this article to be about the tragic onstage death of drummer and friend Devon Clifford, but it’s inexorably linked to the band’s story.

And I can only really tell it from my point of view. I wasn’t sure I would go to the funeral but a mutual friend told me that Devon would want me to go. Portland Hotel Society, a local housing provider which Devon had thrown the weight of his passion behind, rented a bus to drive out to Abbotsford. I held up pretty well until my friend Al Boyle got up to play. Then some yelled “Spagett”. Then Krista and Becky sang “Cloudbusting” and I lost it.

The band would try to carry on. Krista would leave the band and Bobby Siadat and Robert Andow of the band Gang Violence would fill in for touring. When that didn’t go as planned Al Boyle who had been in the punk band Hard Feelings with Devon would replace Bobby. They officially went on hiatus in 2011 only to reunite a year later with Krista back on keys and a drum machine in place of Devon.

And while the band’s self titled 2016 release would be their moment of closure, the reissue of XXXX is one of celebration. Celebration of what they made with Devon. Celebration of a near perfect moment in time. A capsule of a entire city at it’s peak. The band has changed. The scene has changed. And I’ve changed. But there will always be XXXX within in our hearts.

'Cause every time it rains

You're here in my head

Like the sun coming out

Ooh, I just know that something good is going to happen

And I don't know when

But just saying it could even make it happen

Sean Orr Vancouver, BC January 2020

--------------------

We are so excited to reissue a limited run of XXXX on clear vinyl through Paper Bag Records Vintage for Record Store Day on August 29th! Support your local stores & grab this album on vinyl for the first time in 10 years! https://recordstoredaycanada.ca #yousayparty #YSPWSD

--------------------

About Sean Orr Sean Orr is a writer, musician, artist, activist, and dishwasher living and working in the unceded Coast Salish territories of Vancouver, B.C. Besides his twice weekly news column in Scout Magazine he writes for Beatroute and has written for Vice Magazine and Montecristo among others in the past. He’s the frontman in the punk band Needs and also has a pickle company called Brine Adams. Twitter | NEEDS | Tea & Two Slices | Flickr

1 note

·

View note

Text

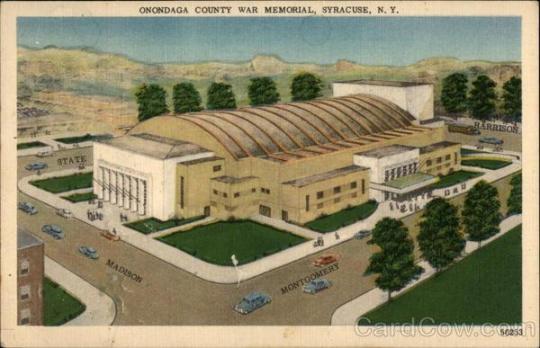

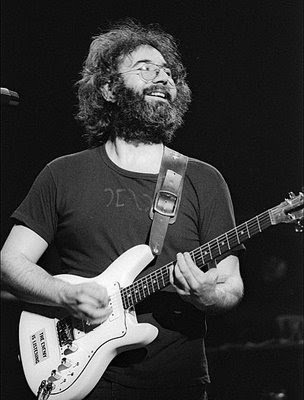

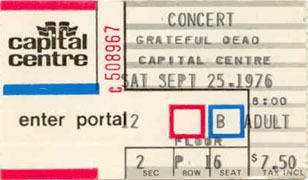

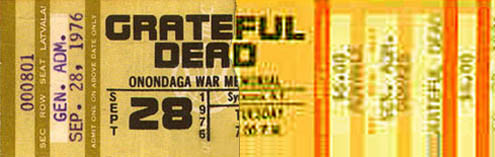

Grateful Dead Monthly: Capital Centre – Landover, MD 9/25/76 // Onondaga County War Memorial – Syracuse, NY 9/28/76

On Saturday, September 25, 1976, the Grateful Dead played a concert at the Capital Centre in Landover, Maryland. And on Tuesday, September 28, 1976, they played a concert at the Onondaga County War Memorial in Syracuse, New York.

The Capital or “Cap” Centre opened in 1973 just outside Washington, D.C. The arena hosted the NBA’s Washington Bullets and the NHL’s Washington Capitals, as well as the Georgetown University men’s basketball team, until 1997. It was demolished in 2002 and replaced by a mall. The Dead played there 26 times from 1974 to 1993.

Perhaps ill-named, the Onondaga War Memorial is less of a memorial, and more of an indoor arena. The venue was built from 1949-51, and Wikipedia calls it a significant example of “World War I, World War II[,] and Aroostook War commemorative,” as well as “an early and sophisticated example of single-span thin-shell concrete roof construction.” Ok, boomer. It’s an old shed. And it’s now called the Upstate Medical University Arena at Onondaga County War Memorial – a name that just rolls off the tongue. The Dead played there five times: twice in 1971 (during the furious five era), twice in 1973, and once in 1976.

These shows were in the middle of a short tour that began in Durham, NC on 9/23 and ended in Detroit, MI on 10/3. Between those dates, the band wound its way north, playing Landover, Rochester, NY, and then Syracuse. The first and third of those nights are commemorated (or memorial-ized, see what I did there?) as Dick’s Picks #20.

I asked Liner Notes’ Chief Dead-itor ECM for his impressions of that particular release. He focused on the Landover show, 9/25/76, and sent this extended review:

Note – Keith’s piano is very prominent in the mix and he is in good form for this show.

The band started touring again in June 1976 after an almost two-year hiatus that began after the Winterland shows in October 1974. There were some big changes when the band returned, the most notable being that Mickey Hart rejoined the band after a five-year absence. It took the band some time to adapt to the two-drummer format. This resulted in an overall tempo slow-down for most songs. However, by September the band started hitting their groove and was working towards the glorious, almost orchestral sound that they eventually achieved in May 1977. There are hints of that progression in this show – especially in songs like Mississippi Half-Step, Sugaree, Cassidy, Scarlet Begonias and Dancing in the Street (sans Mu-tron, of course).

The show starts off in fine form with a Bertha that is speedy and driving. It has a great finale with Garcia adding “whoa’s and woos” in between each “Anymore.”

Minglewood is next. It is only the ninth performance since the band revived it at the Orpheum run in July 1976 after a five-year absence (last played on 4/29/71 at the Closing of the Fillmore East). These early versions are tepid compared to the way it would be played with Brent but the band puts in a very solid performance.

The next highlight of the evening is Cassidy. The jam section is now more developed than it was when the band brought it (back) into the repertoire in June 1976 (they played is once on 3/23/74 and then shelved it until the first show in 1976 – 6/3/76). This is an upbeat version that is totally nailed.

Mama Tried, usually a throw-away tune, has some pep in its step and keeps the energy high. It features enthusiastic backing vocals by Garcia.

The Peggy-O that follows is gorgeous, especially Garcia’s second solo. Beautiful vocals .

The set closes with a lively Let It Grow, which gets downright frenetic at some points. There is also a short drum break which only happened in 1976 and then things simmer down and become a bit exploratory before the reprise. It is notable that Let it Grow was almost exclusively a second set song in 1976. So this first set performance was a bit of a treat. Additionally, Let it Grow would only be played two more times after this before taking a one-year break, making it all the more special. Instead of ending the set there, the band break tradition and give the audience another treat – a bonus song to end the first set – Sugaree. This version is nice and gooey. More telling though is how it shows early signs of the powerhouse that it was about to become in 1977.

Set II opens with Lazy/Supplication and Half-Step which are typically “first set songs.” It’s always interesting to see when the band mixes things up and gives “first-set songs” the second-set treatment.

In this case, Lazy/Supplication fares about the same way it does as a first set song. That is to say that it is not as long or exploratory as we might expect a second set song to be. Also, the Supplication jam seems to get cut-off early, but Weir’s vocals are very amped up!

On the other hand, Half-Step is a horse of a different color. Similar to Minglewood, Half-Step was revived at the Orpheum run in July 1976. It had absent since the hiatus. The tempo here starts off a little sluggish but the advantage of this is that it provides Garcia the opportunity to really dig deep vocally with the way he emphasizes the lyrics (i.e., on my waaaaay).The Rio Grandee-O section is fabulous. Garcia plays fluid, joyful, melodic passages which serve to electrify his bandmates as they approach the vocal section. The energy is palpable. The vocal harmonies are delivered with such confidence that the song feels like an anthem. Keith’s gorgeous piano flourishes add to the joyful vibe. Garcia patiently takes the outro jam to a slow and steady peak – early signs of 1977 (without the massive crashing chords). This is probably the best version of 1976.

From there the drummer’s pound out a brisk and aggressive lead-in to Dancing and the energy lifts off. Once the lyrics are dispensed with, Garcia begins a quick and funky lead that foreshadows the 1977 versions without the Mu-Tron. Things slow down as the vocals trail off. The band embarks on what will be the very last version of Cosmic Charlie ever played. Although I love the album, Aoxomoxoa, I am not a big fan of the slowed-down versions of Cosmic Charlie and St. Stephen that were revived in June 1976. The outro chorus “Go On Home…” on this version is extended and repeated like a chant which makes it gloriously eerie. Maybe it was their special way of giving Cosmic Charlie a final sendoff.

Coming off a stand-alone slow tune, the band needed to pick the energy back up so Scarlet Begonias was a perfect choice. This is an upbeat, full-bodied version that hints at how the song will develop when the band joined it with Fire on the Mountain just 6 months later. Donna is very subdued on the outro and does not overstep as she sometimes can do. Her voice quietly drifts in and out of the music which is the way I like it.

The show ends with a typical long romp on the St. Stephen > Not Fade away segue which was so typical for this era. A respectable Sugar Magnolia provides the encore for one of the better shows from 1976.

And Icepetal at the Grateful Dead Listening Guide blog has covered the Syracuse show, not only highlighting the show itself, but also discussing ’76 and its audience recordings:

This show is featured almost in its entirety on Dick’s Picks Vol. 20. But it has history from long before it came out commercially, and that history is in part related to demonstrating the glory of AUD recordings from a part of a year that isn’t famous for its soundboards. Most of the SBDs from Fall 1976 fall a bit flat. They just lack a lot of sparkle. As we have been dabbling into this period with AUD tapes, there are a fair number of good ones to be found, and it is now time to add 09/28/76 to this list as one of the more satisfying 1976 AUDs. Very up front, with exceptional low end, this tape permeates the sound field with the power of the Dead’s new (in ’76) sound system. Particularly sweet are the sound of the kick drums and Phil’s bass. These instruments tend to lay very flat on the SBD’s, while in the AUDs you can literally touch the energy coming out of them. The drums, especially, pulse with power. You can almost feel the push on the air, absent almost completely from the soundboards. On 09/28 we are thus treated to that most wonderful alignment of the stars – a wonderful recording of a wonderful performance.

It’s hard not to talk about 1976 without mentioning the dismissing the year gets in many Dead trading circles. Generally you either love 1976, or absolutely don’t. However, even some of the most anti-76 folks out there will generally acquiesce that there are a few glowing spots in this year. 09/28/76 falls into this category easily. In fact, after revisiting this AUD after a good many years myself, I regret that it took me so long to share it here on the blog. This show and recording demonstrate all that I love about 1976, and then some. It was one of the first late-1976 tapes I acquired in trade, and as an AUD, continued to cement my preference for this recording medium over soundboards. For this show, and a few others from the Fall of ’76, the audience tape brings an entirely heightened level of experience to the music itself – not because of the crowd, or the energy in the air, but strictly based on the way the sound of the band comes through on tape.

Icepetal’s typically eloquent rendering of the music is worth a read. He effuses about the long transition between Let It Grow and Goin’ Down the Road Feeling Bad, as well as the second set Playing Sandwich – Playing in the Band > The Wheel > Samson and Delilah > Jam > Comes a Time > Drums > Eyes of the World > Dancing in the Street > Playing in the Band.

I found a review of the Syracuse show in the college newspaper. Wheel of Fortune is such a great song, ha.

Here’s the Spotify widget for DP#20.

https://open.spotify.com/album/34KjKiNyuggM0g2No4ZnTv?si=R3d3HsVvTXK6Faf1WHAVTw

And transport to an audience recording of 9/28/76 HERE.

Thanks as always to Ed.

More soon.

JF

from WordPress https://ift.tt/3638ekG via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

How The Ren & Stimpy Reboot Reignited the Debate Around Animation Gatekeepers

https://ift.tt/eA8V8J

On Aug. 5, Comedy Central announced a reboot to the classic 1991 cartoon The Ren & Stimpy Show. The show’s initial airing, as one of the three original Nicktoons (alongside Doug and Rugrats), was a milestone in cartoon television history, with its purposely crude yet dynamic visuals and heavily exaggerated animation and aesthetics. It also had a deeply complicated run. Ren & Stimpy was controversial both in public and behind the scenes and its sordid history includes creator John Kricfalusi’s inability to complete episodes on time, episodes Nick edited down or refused to air, and the criticisms of the show’s most disturbing aspects. Nevertheless the show was able to cement itself with a passionate, dedicated cult following.

That sordid history, however, reached an impassable point in 2018 when Buzzfeed reported a grotesque expose on Kricfalusi, and his grooming and dating of a 16-year-old girl during the show’s production. Before this point, Ren & Stimpy and John Kricfalusi had been provided a certain degree of street cred from beleaguered artists, who saw the show and creator as brilliantly and bravely fighting the corporate whims of sanitized Americans (also often omitting the more grounded stories of Kricfalusi being notoriously bad at his job). But this overt act of sexual predation, rightly, was too far. John Kricfalusi was “canceled.”

So upon hearing the news of the reboot, much of animation Twitter revolted. Even though Kricfalusi will reportedly not be receiving any credit, residuals, or other financial benefits of this reboot, it still felt insulting, particularly to the victims of Kricfalusi’s actions. Nothing can really untie the connection between Ren & Stimpy and John Kricfalusi; the two are deeply intertwined in the way some television programs are synced so distinctively to their showrunner. The revival, to some, feels like a celebration of the counterculture hero worship Kricfalusi once profited from but no longer deserves.

But this revolt is also driven by more than an ethical awakening. This Ren & Stimpy reboot controversy also epitomizes a broad response to the so-called “gatekeepers” of animation – a field that has been notoriously insular, controlling, toxic, and demeaning–and that’s across the board.

Among the animators who opposed the Ren & Stimpy reboot was Lauren Faust. (She expressed her support with one of the victim’s of Kricfalusi’s actions, and passed along a petition against the reboot of the show.) Her agreement with the opposition is particularly interesting, given her own history with the full spectrum of the problems of the shifting, dynamic roles of gatekeepers. Faust was the creative mind behind the 2010 reboot of My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic, itself a show brimming with controversy and awash with toxic gatekeepers. There’s a lot to explain here to fully understand the context of this, but I’ll keep it as brief as possible. My Little Pony at the time was one of a handful of shows to debut on the now-defunct The Hub, a Hasbro-run network where toy-based cartoons were always going to be part of the overall strategy. Nothing about that is surprising.

Upon the announcement of that reboot, however, Amid Amidi, the author and editor of Cartoon Brew, wrote a lengthy criticism of the news and how it represented the death of creator-driven animation. At the time, Cartoon Brew was the premier and most well-known location for animation news and stories; many industry vets and fans mingled in the comments sections for years. It also had a deeply negative reputation, particularly Amidi himself, who was known to be fairly hostile towards most modern corporate-driven cartoons (he did champion indie animation a lot, but it was strangely pick-and-choose, and he was also notoriously a huge John Kricfalusi fan). In Amidi’s perspective, My Little Pony was the antithesis of an era that propelled original, creator-driven (and, it should be noted, all-male) cartoons to the forefront. Arguably starting with Kricfalusi, it includes shows like Rocko’s Modern Life by Joe Murray, Dexter’s Laboratory by Genndy Tartakovsky, The Powerpuff Girls by Craig McCraken, and even Family Guy by Seth MacFarlane. (Ironically, Amidi also criticized that particular era’s burgeoning reliance on rebooting animated properties and television shows based on film properties.)

Amidi’s article created a lot of pushback, as evident in the comment section of that same article, but also from burgeoning corners of the Internet that mainstream news outlets had not yet caught up to. Primarily, there was the one underground online spot that skirted rules and protocols to discuss cartoons of all degrees with a certain equality: 4chan, specifically, its /co/ section, dedicated to cartoons and comics. /co/ discovered Amidi’s article and also revolted for perhaps an unexpected reason. My Little Pony’s sudden surge in popularity and appeal arguably came from the denizens of /co/ watching and promoting the show to spite Amidi. It was the first all-out “attack” against Amidi as gatekeeper himself, rebelling against his thesis and propping up a “corporate-driven” show. Gatekeepers aren’t just the people who have corporate power; they’re anyone who wields access and influence primarily on personal needs, desires, and whims, and not on the talent, value, and input of others.

Over the years though, the parameters of gatekeeping in animation shifted, courting in its own ways figures that vied for the mantle. Faust left the show after the first season, and while stories abound over why, it’s often attributed to Faust and The Hub execs having “creative differences” – the most loaded term in entertainment history. The show would continue on for eight more seasons, many of which were coupled with pockets of controversy, from wonky storylines, awkward characterizations, “ships,” and one particular moment in which a background character spoke for the first time with a… questionable voice.

All of this, though, were just moments that exemplified a deep concern over the show’s social-media fanbase and its relationship to the show, its cast, and its crew. It probably was the first time all these sides were so intertwined, in which the shows crew, the fans, and the Hub itself vied for a sort of control, a “gatekeeping,” of the show’s reputation and direction. My Little Pony, despite Faust’s vision to appeal to a broad swath of the audience, was a show built to appeal to the demographic of young girls, but that fanbase’s most vocal and active members were mostly reactionary men.

It seems so obvious in hindsight now, and I don’t doubt that a huge number of them did genuinely enjoy the show and its fan-driven projects, but certain type of angry, reactionary men “gatekept” the show, controlling the reactions, fan works, and forums, well into 2020. Such a sentiment may be more common and understood now, as any analysis of Comicsgate or Gamergate would tell you, but it’s arguable that these types of fans have tested and dabbled with this kind of controlling, dominating, non-inclusive attitude in various fan spaces, such as Tumblr, Youtube, message boards, websites, and artwork/stories, even back in 2010. Lest you think this take is exaggerated, well, take a look at Buzzfeed’s report that the My Little Pony’s fanbase seems to have a “Nazi” problem.

Such a concept being exposed in 2020 is, unfortunately, not that surprising. There is a top-down reckoning with all matters of vicious, controlling, toxic gatekeepers, many of whom are male, white, cis, and straight. Animation, in particular, has an ugly history of shifting but problematic trends of gatekeeping. The insidious “CalArts” style criticism tossed about on social media (often attributed to John Kricfalusi, who coined the term on his blog back in 2010) currently is absurd, but it’s an idea derived from a particular narrow career pipeline in which a majority of animators had to go through CalArts to increase the chances of getting a job (thankfully, it’s not nearly as problematic as it once was).

There’s the infamous story of Brenda Chapman and her firing from Brave. The first female director for a Pixar film to be let go is not a good look, and her comments at the time suggested some understated, egregious “boys club” behavior that took place behind the scenes at Pixar. Chapman’s comments would be proven even more credible a few years later when multiple women came forward detailing producer John Lassiter’s non-consensual behavior towards Pixar female employees; for which he resigned in 2018. In that same Vulture piece, Jim Morris, the president of Pixar, all but mentions the “old guard” as gatekeepers who are on their way out, emphasizing more of a diverse workforce in the years to come.

Two years later, the absolute re-thinking and re-imagining of entire industries through more diverse perspectives and people has taken shape in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. The full cultural shift is wildly complex and its worth examining on its own, but it can be broadly and generally tracked as thus: protests against police brutality led to a re-examination on how police are portrayed in pop culture, which then led to an overall reckoning on whose perspectives we place front and center, and why. Showrunners, directors, producers, and all matter of gatekeepers, once confident in their vision, had begun to concede the inherent blinders and obstacles their visions created.

Even prior to this current reckoning, Bojack Horseman Raphael Bob-Waksberg creator admitted regret on casting the white Alison Brie to play a Vietnamese-American; he directly explores this even more here. Biracial characters in both Big Mouth and Central Park, once voiced by white actors, now will be recast to reflect their race, with Central Park already choosing Emmy Raver-Lampman as a replacement. (It’s interesting to hear, in particular, Loren Bouchard’s comments in regard to the casting of Kristen Bell as the original voice for Molly.)

It’s important to note that in no way are the decisions of people like Bouchard and Bob-Waksberg comparable to the behaviors of Lassiter and Kricfalusi. But they all do speak to a perspective of gatekeepers, even well-meaning ones, who are blinded by the inherent restrictions their visions can be. The overall industry, animation in particular, is so subsumed by a combination of networked, closely-synced friends and a cavalier attitude towards vocal, toxic, sexist and racist environments (the former often utilized to avoid complaints of the latter) that such hostilities and obstacles have become normalized, a part of the systematic flow of “how things are” instead of the unfair, moral, ethical, and sometimes criminal issues that they actually are. These were the big news stories; Twitter itself is awash with stories of smaller, individual stories of industry vets going through awful, toxic points in their careers. (As of this writing, two new stories have cropped up in relation to all this: one concerning a staff mutiny against the showrunner of the show All Rise, and one about the Criterion Collection’s lack of films from Black directors–both stories speaking to the narrow lens that gatekeepers, and those who empower gatekeepers, employ.)

It’s hard, in many ways, to contextualize the specific accounts told on Twitter. Social media is not a monolith, and its specificity and constant churn make it hard to narrow in on anything like a cohesive perspective. Still, the general consensus seems to be that the industry needs changing, although that also is butting up against a new crop of critics, staking their claim to a new “Amidi-like” control of what constitutes the animation worth paying attention too.

YouTube videos and social media influencers have garnered perhaps more attention than they should, often ranting and proselytizing oft-kilter, often-wrong opinions like the aforementioned CalArts style, criticizing changes in character designs, or otherwise completely misunderstanding how animation today even works. The specific circumstances that My Little Pony faced back in 2010 have essentially diffused across a whole swath of social media venues in 2020, of the push-and-pull between viewers and animated shows, of the fanbase and (hostile) critics, of the industry vets and professional critics, all vying for a voice, a stake, a role in the great gatekeeper narrative, to either open or close the door on new, unique perspectives.

It all comes back to the Ren & Stimpy reboot. John Kricfalusi used to offer animation classes, and he was also notoriously known to detest most modern cartoon sensibilities and aesthetics, even before he was outed as a monster. He was, in his own way, a gatekeeper. Comedy Central, instead of opening up to novel, original, and ideally, BIPOC artists, chose to hone in on a show that has too much baggage and history, a choice that itself feels like an act of gatekeeping on its own. There are new shows and new rebooted shows on the way due to the sheer number of cable, streaming, and online outlets that are available to the public. But Ren & Stimpy shows we have a long way to go to break these classic gatekeeper visions. Some things, whether they’re shows or ideas on whose voices to uplift, are best left in the past.

The post How The Ren & Stimpy Reboot Reignited the Debate Around Animation Gatekeepers appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/2FQYbE5

0 notes

Text

How Japan Created the Modern American Bourbon Market

It was 1975 and bourbon sales in America were tanking. The brown spirit had hit its peak just five years earlier, selling some 80 million cases in 1970 — but it all went downhill from there.

Baby boomers coming of drinking age were rejecting the stuffy-seeming whiskey their parents drank, instead favoring beer, cheap wine, and, most especially, clear booze like vodka and tequila. The American whiskey industry was reeling and running out of ideas.

“This was a daunting task since the market was totally Scotch-taste oriented,” William Yuracko, then head of Schenley International’s export division, told the The New York Times in 1992. Japanese people mostly drank Scotch — the country had lifted all restrictions on imported spirits in 1969 — or their own homegrown whiskey, which was likewise based on a Scotch flavor profile. “Bourbon was unknown and a total departure from the taste pattern,” he wrote.

Remarkably, within a few short years, Yuracko (who would would become Schenley president from 1975 to 1984) and others would create a frenzy for bourbon in Japan. In fact, the country’s desire for very well-aged, high-proof, premium-packaged, limited editions and single-barrel bourbons helped Kentucky survive when the American bourbon market was dead as disco.

The U.S. would, in turn, follow Japan’s lead and, as the world entered a new millennium, start latching onto these trends and introducing products that helped revive America’s fervor for the once-humble spirit, ultimately and unwittingly turning it into something now rabidly pursued by connoisseurs the world over.

A Critical Mass of Bourbon

Yuracko first started taking reconnaissance trips to the Far East in 1972 and quickly realized that getting Scotch-swilling Japanese old-timers to switch to bourbon would be nearly impossible. He decided to instead focus his efforts on Japan’s youth, the “post-college consumer,” he told The Times, “whose tastes were not yet formed and who was attuned to Western products and ideas,” like Coca-Cola and Levi’s.

“They were having their own youth revolution, [like] what we had gone through in the ’60s they were going through in the 80s,” explains Chuck Cowdery, author and bourbon historian. “Rejecting their parents’ generation, including what their parents’ generation drank. They were open to trying something new.”

Enter bourbon. Then, as now, it was very hard for foreigners to make headway in Japanese business. Yuracko knew he’d need a local liaison, so he offered a distribution partnership with Suntory, the Japanese whiskey brand that already controlled 70 percent of the local market. Brown-Forman, another American whiskey powerhouse and Schenley’s best competitor, would eventually offer Suntory the same deal.

“I cannot overestimate the importance of the decision taken by Schenley management to place their most important brands in the same house with their major competitor,” Yuracko explained in a paper he wrote for the Journal of Business Strategy in 1992. “This would be tantamount to Ford and General Motors giving all their top models to Toyota to market in Japan.”

It was a major gamble for everyone involved. Suntory could, of course, intentionally torpedo all bourbon sales to assure Japanese whiskey would never again have a competitor; or it could favor one bourbon brand over the other. The fact was, however, neither Schenley nor Brown-Forman had much to lose. If they didn’t take the gamble, bourbon might not even exist by the end of the decade.

Suntory didn’t want to simply do a trial, either. According to Yuracko, Suntory wanted a “critical mass” of bourbon, “a product for every taste and price level … and each brand was given its own identity and market niche.” Schenley offered Suntory Ancient Age, J.W. Dant, and I.W. Harper. Brown-Forman handed over Early Times, Old Forester, and Jack Daniel’s.

Since most drinking in Japan was done outside of the home, Schenley and Brown-Forman together began setting up bourbon bars all over the country. The bars had “an unsophisticated atmosphere that would appeal to young people already attracted to American clothes, cars, and customs,” Yuracko explained, playing country music and serving American food like hamburgers and chili, and only pouring Suntory’s six bourbon brands.

Instead of buying single glasses of bourbon, young customers purchased bottles, stored in cabinets along the bars, each adorned with a neck tag denoting whose was whose. In an era before TikTok, it became a youthful challenge to see who could drink the most personal bottles. Thanks to heavy advertising from Suntory, one brand quickly began to rise above the others.

“I.W. Harper was the eye-opener,” explains Cowdery. A bottom-shelf product in America, it was naturally able to be sold at much higher prices in Japan, before Schenley eventually fully repositioned it as a premium, 12-year-old product. If it was only moving 2,000 cases internationally in 1969, I. W. Harper eventually became the largest-selling bourbon brand in Japan at more than 500,000 cases per year by 1991. Cowdery explains, “It was profitable to buy cases of I.W. Harper on [the American] wholesale market and privately ship them to Japan.”

Eventually, the U.S. had to take I.W. Harper off the market stateside in order to satisfy demand in Japan. Soon enough, other brands took notice and decided to see if they, too, could become “big in Japan.” By 1990, 2 million cases of bourbon were headed to the country every year.

More Brands Head to Japan

In a sleepy Osaka suburb, a three-story building that has been everything from a hotel to a brothel is now a bar styled like a western saloon. It serves American food like fried chicken, thumps Dylan and the Beatles on a vintage jukebox, and mixes up classic cocktails like the Mint Julep and another called the Scarlett O’Hara. This is Rogin’s Tavern in Moriguichi, a bourbon bar that opened in the 1970s that remains a shrine to Americana and its governmentally protected spirit, stocking more and arguably better bourbon than pretty much any single bar in America.

“I tasted my first bourbon in the basement bar of the Rihga Royal Hotel, a famous old place in Osaka,” claims Seiichiro Tatsumi, Rogin’s owner since 1977. He quickly became obsessed, reading everything he could about bourbon via literature provided by the American Cultural Center in Osaka. He finally visited Kentucky for the first time in 1984 and fell in love, driving its country roads, stopping at off-the-beaten path liquor stores, and acquiring numerous dusty bottles to bring back to Japan. He now owns a second home in Lexington.

Over the years, Tatsumi claims, he has probably “self-imported” some 5,000 bourbons from America back to his bar. “I stop at every place I pass, and I don’t just look on the shelves,” he says. “I ask the clerk to comb the cellar and check the storeroom for anything old. I can’t tell you how many cases of ancient bottles I’ve found that way.”

It wasn’t only Tatsumi. Japan gave these old bourbon brands a new lifeline. For example, Four Roses had long fallen out of favor with American drinkers by the 1970s. In 1967, Seagram’s turned the once-venerable brand into a dreaded blended whiskey, cut with grain neutral spirit and added flavoring.

“[B]y the time the ‘90s rolled around it was just an average blended whiskey,” the late Al Young, Four Roses’ former senior brand ambassador who worked at the company for 50 years, told VinePair contributor Nicholas Mancall-Bitel last year. But in Japan it was legitimate straight bourbon whiskey, packaged in sleek Cognac-style bottles with embossed silver roses, and it was a big hit. Just as Schenley and Brown-Forman had partnered with Suntory, in 1971 Four Roses struck up a partnership with Kirin, Japan’s top beer brand.

If brands like I.W. Harper, Four Roses, and Early Times were saved by Japan, others were specifically created for it. Blanton’s, for example, was spawned in 1984 by two former Fleischmann’s Distilling execs, Ferdie Falk and Bob Baranaskas. The two had acquired the Buffalo Trace distillery (then known as the George T. Stagg Distillery), as well as Schenley’s key bourbon, Ancient Age. Believing, like Yuracko, that the future of bourbon was overseas, they called their new company Age International.

“[T]he brand chased the profitable high-priced segment,” writes Fred Minnick in his book “Bourbon: The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of an American Whiskey.” In this case, that meant introducing the world’s first commercial single-barrel bourbon, specifically designed for Japan, and packaged in a now iconic grenade-shaped, horse-stoppered bottle.

Blanton’s was such a hit in Japan that by 1992 Japanese company Takara Shuzo had purchased Age International for $20 million. It immediately flipped the actual distillery to Sazerac, while retaining the brand trademarks for Blanton’s.

Aged Bourbons Claim a Price

Accustomed to Scotch, once Japanese consumers “moved onto other types of whiskey, they already had these expectations built in for 12-, 15-, 18-year age statements,” explains John Rudd, an American who formerly lived in Japan and runs the Tokyo Bourbon Bible blog.

Bourbon in America had typically been released after about four years — it got too oaky if it aged much longer, it was believed at the time — and few consumers particularly cared about lofty age statements. Not so in Japan and, luckily, the glut in America allowed many bourbon distilleries to unload what they thought was over-aged junk.

“With a depressed market in America, lots of bourbon, especially extra-aged bourbon, was shipped to Japan where it could command a higher price,” Rudd says.

There was Very Old St. Nick, specially created in 1984 for the Japanese market, some as old as 25 years. There was Old Grommes Very Very Rare Kentucky Straight Bourbon Whiskey, which in the late 1980s started sending Japan bottles as old as two decades. A.H. Hirsch, aged 15, 16, and eventually 20 years, landed in Japan as early as 1989, and is still some of the most coveted bourbon of all time (so much so that Cowdery wrote an entire book about it).

Heaven Hill, today the largest family-owned and operated distillery in the U.S., specifically bottled an Evan Williams 23 for the Japanese market and created new brands like Martin Mills 24 Years.

“Japan considered bourbon a prestigious, highly coveted consumer good,” says Jimmy Russell, Wild Turkey’s master distiller who started visiting Japan in the 1980s. Every year he returned with special bottlings from his company, some as old as 13 years, a lofty age that never existed in America. “Back then, you’d see private bottle programs at prestigious bars where high-level executives would have their own bottles of bourbon designated ‘my bottle.’”

Rogin’s Tavern, for one, started tapping distilleries for its own private, cask-strength bottlings. Willett provided a 25-year-old labeled “Rogin’s Choice.” Julian Van Winkle III, scion of the soon-to-come Pappy dynasty, offered a 12-year bottling. Van Winkle III, in particular, kept his nascent company afloat in the mid-1980s and onward by providing special bottlings, many under a name you could easily now call the entire Japanese whiskey marketplace: Society of Bourbon Connoisseurs.

Van Winkle III first released Pappy Van Winkle’s Family Reserve 20 Year in America in 1994; by the mid-2000s, Pappy had become the most coveted whiskey in the country, regularly selling for thousands of dollars per bottle.

“Bourbon became popular here [in America] again,” explains Rudd. “And people quit thinking it needed to be young.”

The American Bourbon Revival

America’s bourbon malaise would last nearly three decades, reaching its nadir in 2000, when a mere 32 million cases were moved stateside. Of course, it’s always darkest before the dawn, and, thanks to Japan’s example, things were already being put into place for bourbon’s homeland revival.

Like at Four Roses, where Jim Rutledge took over as master distiller in 1995 and made it his mission to get the company to start letting American consumers finally taste the high-quality bourbon Japan had been enjoying for decades. As Mancall-Bitel explained, however, “The bourbon was performing too well overseas and the company didn’t want to rock the boat — until it was rocked from within the company.”

Seagram’s collapsed and started selling off its assets. Rutledge convinced Kirin to buy Four Roses, and the eventual Japanese CEO, Teruyuki Daino, moved his offices from Tokyo back to the distillery in Lawrenceburg, Ky. By 2002, once again, Four Roses bourbon was sold in America. Today it’s one of the bourbon world’s most revered brands, introducing geek-friendly products like Single Barrel in 2004 and the Small Batch series in 2006.

Japan proved that well-aged, premium bourbon actually had a place in the world. Bourbon didn’t have to be Scotch’s economical, bottom-shelf brother. Blanton’s, when it was finally sold in America, was priced at $24 a bottle — then a massive price point — and was advertised in such upscale places as The New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal, and Ivy League alumni mags. Around the same time, Japanese drinkers were gladly paying $115 per bottle.

Bourbon’s rebirth in America has caused many brands to pull back their products from the Japanese market and raise prices on the little still sent there. Japan’s taste for bourbon has dwindled. At the same time, American tourists were heading to Japan to clear shelves of old stock.

“It all corresponded with the American bourbon boom getting out of hand,” explains Rudd. He believes Japan is no longer the bourbon oasis that it once was, even as recently as 2014, when he lived near a liquor store that stocked rare bottles like Society of Bourbon Connoisseurs, gold wax A.H. Hirsch, Van Winkle 1974 Family Reserve 17 Year, and Buffalo Trace Antique Collection offerings from the early aughts.

Rudd says he’d buy a few bottles here and there, always resting assured that more would be there any time he returned. “Then one day, I went back to the store and nothing was left,” he says. “I asked the owner what happened and he told me, ‘Some American guy named Alex came by and purchased all of it.’”

The article How Japan Created the Modern American Bourbon Market appeared first on VinePair.

Via https://vinepair.com/articles/japan-created-american-bourbon-market/

source https://vinology1.weebly.com/blog/how-japan-created-the-modern-american-bourbon-market

0 notes

Text

How Japan Created the Modern American Bourbon Market

It was 1975 and bourbon sales in America were tanking. The brown spirit had hit its peak just five years earlier, selling some 80 million cases in 1970 — but it all went downhill from there.

Baby boomers coming of drinking age were rejecting the stuffy-seeming whiskey their parents drank, instead favoring beer, cheap wine, and, most especially, clear booze like vodka and tequila. The American whiskey industry was reeling and running out of ideas.

“This was a daunting task since the market was totally Scotch-taste oriented,” William Yuracko, then head of Schenley International’s export division, told the The New York Times in 1992. Japanese people mostly drank Scotch — the country had lifted all restrictions on imported spirits in 1969 — or their own homegrown whiskey, which was likewise based on a Scotch flavor profile. “Bourbon was unknown and a total departure from the taste pattern,” he wrote.

Remarkably, within a few short years, Yuracko (who would would become Schenley president from 1975 to 1984) and others would create a frenzy for bourbon in Japan. In fact, the country’s desire for very well-aged, high-proof, premium-packaged, limited editions and single-barrel bourbons helped Kentucky survive when the American bourbon market was dead as disco.

The U.S. would, in turn, follow Japan’s lead and, as the world entered a new millennium, start latching onto these trends and introducing products that helped revive America’s fervor for the once-humble spirit, ultimately and unwittingly turning it into something now rabidly pursued by connoisseurs the world over.

A Critical Mass of Bourbon

Yuracko first started taking reconnaissance trips to the Far East in 1972 and quickly realized that getting Scotch-swilling Japanese old-timers to switch to bourbon would be nearly impossible. He decided to instead focus his efforts on Japan’s youth, the “post-college consumer,” he told The Times, “whose tastes were not yet formed and who was attuned to Western products and ideas,” like Coca-Cola and Levi’s.

“They were having their own youth revolution, [like] what we had gone through in the ’60s they were going through in the 80s,” explains Chuck Cowdery, author and bourbon historian. “Rejecting their parents’ generation, including what their parents’ generation drank. They were open to trying something new.”

Enter bourbon. Then, as now, it was very hard for foreigners to make headway in Japanese business. Yuracko knew he’d need a local liaison, so he offered a distribution partnership with Suntory, the Japanese whiskey brand that already controlled 70 percent of the local market. Brown-Forman, another American whiskey powerhouse and Schenley’s best competitor, would eventually offer Suntory the same deal.

“I cannot overestimate the importance of the decision taken by Schenley management to place their most important brands in the same house with their major competitor,” Yuracko explained in a paper he wrote for the Journal of Business Strategy in 1992. “This would be tantamount to Ford and General Motors giving all their top models to Toyota to market in Japan.”

It was a major gamble for everyone involved. Suntory could, of course, intentionally torpedo all bourbon sales to assure Japanese whiskey would never again have a competitor; or it could favor one bourbon brand over the other. The fact was, however, neither Schenley nor Brown-Forman had much to lose. If they didn’t take the gamble, bourbon might not even exist by the end of the decade.

Suntory didn’t want to simply do a trial, either. According to Yuracko, Suntory wanted a “critical mass” of bourbon, “a product for every taste and price level … and each brand was given its own identity and market niche.” Schenley offered Suntory Ancient Age, J.W. Dant, and I.W. Harper. Brown-Forman handed over Early Times, Old Forester, and Jack Daniel’s.

Since most drinking in Japan was done outside of the home, Schenley and Brown-Forman together began setting up bourbon bars all over the country. The bars had “an unsophisticated atmosphere that would appeal to young people already attracted to American clothes, cars, and customs,” Yuracko explained, playing country music and serving American food like hamburgers and chili, and only pouring Suntory’s six bourbon brands.

Instead of buying single glasses of bourbon, young customers purchased bottles, stored in cabinets along the bars, each adorned with a neck tag denoting whose was whose. In an era before TikTok, it became a youthful challenge to see who could drink the most personal bottles. Thanks to heavy advertising from Suntory, one brand quickly began to rise above the others.

“I.W. Harper was the eye-opener,” explains Cowdery. A bottom-shelf product in America, it was naturally able to be sold at much higher prices in Japan, before Schenley eventually fully repositioned it as a premium, 12-year-old product. If it was only moving 2,000 cases internationally in 1969, I. W. Harper eventually became the largest-selling bourbon brand in Japan at more than 500,000 cases per year by 1991. Cowdery explains, “It was profitable to buy cases of I.W. Harper on [the American] wholesale market and privately ship them to Japan.”

Eventually, the U.S. had to take I.W. Harper off the market stateside in order to satisfy demand in Japan. Soon enough, other brands took notice and decided to see if they, too, could become “big in Japan.” By 1990, 2 million cases of bourbon were headed to the country every year.

More Brands Head to Japan

In a sleepy Osaka suburb, a three-story building that has been everything from a hotel to a brothel is now a bar styled like a western saloon. It serves American food like fried chicken, thumps Dylan and the Beatles on a vintage jukebox, and mixes up classic cocktails like the Mint Julep and another called the Scarlett O’Hara. This is Rogin’s Tavern in Moriguichi, a bourbon bar that opened in the 1970s that remains a shrine to Americana and its governmentally protected spirit, stocking more and arguably better bourbon than pretty much any single bar in America.

“I tasted my first bourbon in the basement bar of the Rihga Royal Hotel, a famous old place in Osaka,” claims Seiichiro Tatsumi, Rogin’s owner since 1977. He quickly became obsessed, reading everything he could about bourbon via literature provided by the American Cultural Center in Osaka. He finally visited Kentucky for the first time in 1984 and fell in love, driving its country roads, stopping at off-the-beaten path liquor stores, and acquiring numerous dusty bottles to bring back to Japan. He now owns a second home in Lexington.

Over the years, Tatsumi claims, he has probably “self-imported” some 5,000 bourbons from America back to his bar. “I stop at every place I pass, and I don’t just look on the shelves,” he says. “I ask the clerk to comb the cellar and check the storeroom for anything old. I can’t tell you how many cases of ancient bottles I’ve found that way.”

It wasn’t only Tatsumi. Japan gave these old bourbon brands a new lifeline. For example, Four Roses had long fallen out of favor with American drinkers by the 1970s. In 1967, Seagram’s turned the once-venerable brand into a dreaded blended whiskey, cut with grain neutral spirit and added flavoring.

“[B]y the time the ‘90s rolled around it was just an average blended whiskey,” the late Al Young, Four Roses’ former senior brand ambassador who worked at the company for 50 years, told VinePair contributor Nicholas Mancall-Bitel last year. But in Japan it was legitimate straight bourbon whiskey, packaged in sleek Cognac-style bottles with embossed silver roses, and it was a big hit. Just as Schenley and Brown-Forman had partnered with Suntory, in 1971 Four Roses struck up a partnership with Kirin, Japan’s top beer brand.

If brands like I.W. Harper, Four Roses, and Early Times were saved by Japan, others were specifically created for it. Blanton’s, for example, was spawned in 1984 by two former Fleischmann’s Distilling execs, Ferdie Falk and Bob Baranaskas. The two had acquired the Buffalo Trace distillery (then known as the George T. Stagg Distillery), as well as Schenley’s key bourbon, Ancient Age. Believing, like Yuracko, that the future of bourbon was overseas, they called their new company Age International.

“[T]he brand chased the profitable high-priced segment,” writes Fred Minnick in his book “Bourbon: The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of an American Whiskey.” In this case, that meant introducing the world’s first commercial single-barrel bourbon, specifically designed for Japan, and packaged in a now iconic grenade-shaped, horse-stoppered bottle.

Blanton’s was such a hit in Japan that by 1992 Japanese company Takara Shuzo had purchased Age International for $20 million. It immediately flipped the actual distillery to Sazerac, while retaining the brand trademarks for Blanton’s.

Aged Bourbons Claim a Price

Accustomed to Scotch, once Japanese consumers “moved onto other types of whiskey, they already had these expectations built in for 12-, 15-, 18-year age statements,” explains John Rudd, an American who formerly lived in Japan and runs the Tokyo Bourbon Bible blog.

Bourbon in America had typically been released after about four years — it got too oaky if it aged much longer, it was believed at the time — and few consumers particularly cared about lofty age statements. Not so in Japan and, luckily, the glut in America allowed many bourbon distilleries to unload what they thought was over-aged junk.

“With a depressed market in America, lots of bourbon, especially extra-aged bourbon, was shipped to Japan where it could command a higher price,” Rudd says.

There was Very Old St. Nick, specially created in 1984 for the Japanese market, some as old as 25 years. There was Old Grommes Very Very Rare Kentucky Straight Bourbon Whiskey, which in the late 1980s started sending Japan bottles as old as two decades. A.H. Hirsch, aged 15, 16, and eventually 20 years, landed in Japan as early as 1989, and is still some of the most coveted bourbon of all time (so much so that Cowdery wrote an entire book about it).

Heaven Hill, today the largest family-owned and operated distillery in the U.S., specifically bottled an Evan Williams 23 for the Japanese market and created new brands like Martin Mills 24 Years.

“Japan considered bourbon a prestigious, highly coveted consumer good,” says Jimmy Russell, Wild Turkey’s master distiller who started visiting Japan in the 1980s. Every year he returned with special bottlings from his company, some as old as 13 years, a lofty age that never existed in America. “Back then, you’d see private bottle programs at prestigious bars where high-level executives would have their own bottles of bourbon designated ‘my bottle.’”

Rogin’s Tavern, for one, started tapping distilleries for its own private, cask-strength bottlings. Willett provided a 25-year-old labeled “Rogin’s Choice.” Julian Van Winkle III, scion of the soon-to-come Pappy dynasty, offered a 12-year bottling. Van Winkle III, in particular, kept his nascent company afloat in the mid-1980s and onward by providing special bottlings, many under a name you could easily now call the entire Japanese whiskey marketplace: Society of Bourbon Connoisseurs.

Van Winkle III first released Pappy Van Winkle’s Family Reserve 20 Year in America in 1994; by the mid-2000s, Pappy had become the most coveted whiskey in the country, regularly selling for thousands of dollars per bottle.

“Bourbon became popular here [in America] again,” explains Rudd. “And people quit thinking it needed to be young.”

The American Bourbon Revival

America’s bourbon malaise would last nearly three decades, reaching its nadir in 2000, when a mere 32 million cases were moved stateside. Of course, it’s always darkest before the dawn, and, thanks to Japan’s example, things were already being put into place for bourbon’s homeland revival.

Like at Four Roses, where Jim Rutledge took over as master distiller in 1995 and made it his mission to get the company to start letting American consumers finally taste the high-quality bourbon Japan had been enjoying for decades. As Mancall-Bitel explained, however, “The bourbon was performing too well overseas and the company didn’t want to rock the boat — until it was rocked from within the company.”

Seagram’s collapsed and started selling off its assets. Rutledge convinced Kirin to buy Four Roses, and the eventual Japanese CEO, Teruyuki Daino, moved his offices from Tokyo back to the distillery in Lawrenceburg, Ky. By 2002, once again, Four Roses bourbon was sold in America. Today it’s one of the bourbon world’s most revered brands, introducing geek-friendly products like Single Barrel in 2004 and the Small Batch series in 2006.

Japan proved that well-aged, premium bourbon actually had a place in the world. Bourbon didn’t have to be Scotch’s economical, bottom-shelf brother. Blanton’s, when it was finally sold in America, was priced at $24 a bottle — then a massive price point — and was advertised in such upscale places as The New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal, and Ivy League alumni mags. Around the same time, Japanese drinkers were gladly paying $115 per bottle.

Bourbon’s rebirth in America has caused many brands to pull back their products from the Japanese market and raise prices on the little still sent there. Japan’s taste for bourbon has dwindled. At the same time, American tourists were heading to Japan to clear shelves of old stock.

“It all corresponded with the American bourbon boom getting out of hand,” explains Rudd. He believes Japan is no longer the bourbon oasis that it once was, even as recently as 2014, when he lived near a liquor store that stocked rare bottles like Society of Bourbon Connoisseurs, gold wax A.H. Hirsch, Van Winkle 1974 Family Reserve 17 Year, and Buffalo Trace Antique Collection offerings from the early aughts.

Rudd says he’d buy a few bottles here and there, always resting assured that more would be there any time he returned. “Then one day, I went back to the store and nothing was left,” he says. “I asked the owner what happened and he told me, ‘Some American guy named Alex came by and purchased all of it.’”

The article How Japan Created the Modern American Bourbon Market appeared first on VinePair.

source https://vinepair.com/articles/japan-created-american-bourbon-market/ source https://vinology1.tumblr.com/post/191000805079

0 notes

Text

Missed Classic 69: Borrowed Time (1985) – Introduction