#museum of the slovak national uprising

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

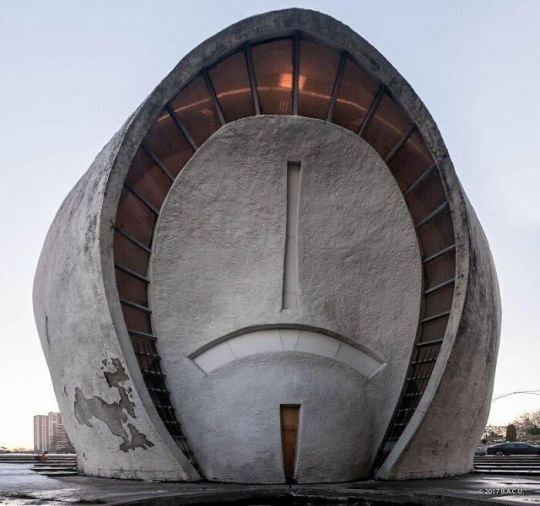

Ilinden / Makedonium – A Monument Dedicated To The Fighters And Revolutionaries Who Participated In The Ilinden Uprising Of 1903

Revitalizing The Heritage Of Socialist Modernism: BACU’s Online Initiative To Protect Central And Eastern European Architecture

Preserving the monumental yet decaying structures of central and eastern Europe erected between 1955-91 is the mission of the online initiative, Socialist Modernism, created by the Bureau for Art and Urban Research (BACU). With an aim to revitalize this heritage, BACU believes in the significance of these elements which managed to defy some of the ideological requirements of their time, giving the urban space a distinct flavor characteristic of the socialist period.

Palace Of Weddings, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, Built In 1987

One Of The Two Halls Of Parting, Memory Park (Kyiv/Kiev) Ukraine. Built 1968–1981

Eastern Gate Of Belgrade, Rudo Buildings, (Istočne Kapije) Belgrade, Serbia, Built In 1976, Architect: Vera Ćirković Engineer: Milutin Jerotijević

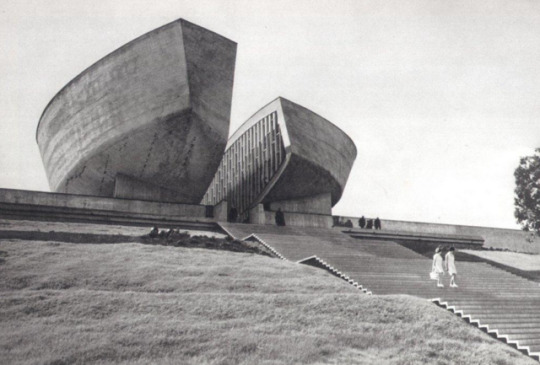

Museum Of The Slovak National Uprising, Banska Bystrica, Slovakia, Built In 1969

#socialist modernism#bureau for art and urban research (bacu)#central and eastern european architecture#architecture#history#socialism#heritage#ilinden uprising#palace of weddings#bishket#kyrgyzstan#halls of parting#memory park#kyiv#kiev#ukraine#belgrade#servia#museum of the slovak national uprising#banska bystrica#slovakia

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Museum of the Slovak National Uprising, Banská Bystrica, 1983. From the Budapest Municipal Photography Company archive.

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

How much can a modern building weigh? This is probably one of the most iconic objects of socialist modernism. The Slovak National Uprising Museum in Banská Bystrica is a symbolic and expressive work in its form. The shape of the building is divided into two parts and connected by a bridge, which symbolizes national unity. The collaborsionist government of Slovakia was allied with the Third Reich until 1944, but with the failures of the Germans on the front, voices began to call for a change in course. It was a convenient time for the uprising to surge. The Czechoslovak Army, with the support of the USSR, began an armed struggle, which the Germans eventually managed to suppress. Banská Bystrica became the capital of the uprising. The anti-fascist uprising was assessed after the war and became an important element of identity in socialist Czechoslovakia. The entrance to Banská Bystrica is adorned with smaller and larger sculptures on this theme, and throughout Slovakia, we can find dozens of monuments, memorials, and street names dedicated to this event. Slovak National Uprising Museum (1959-66) Architect: D. Kuzma Banská Bystrica, Slovakia

https://52.nn.org.ru

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

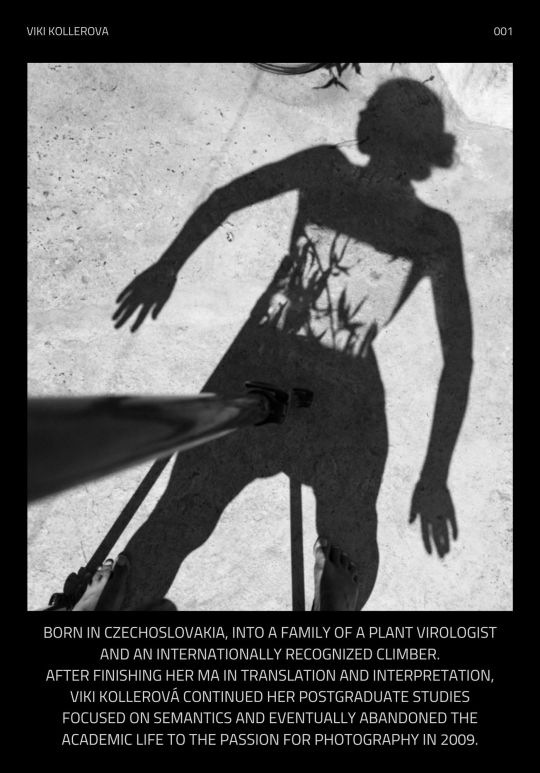

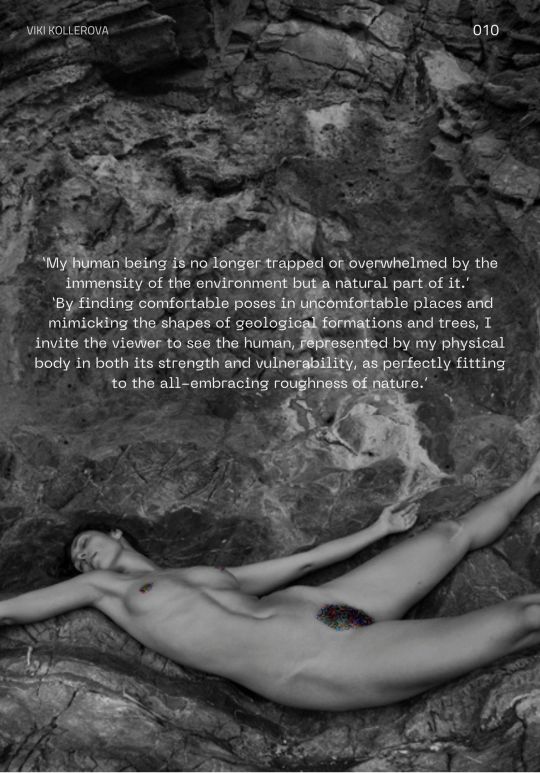

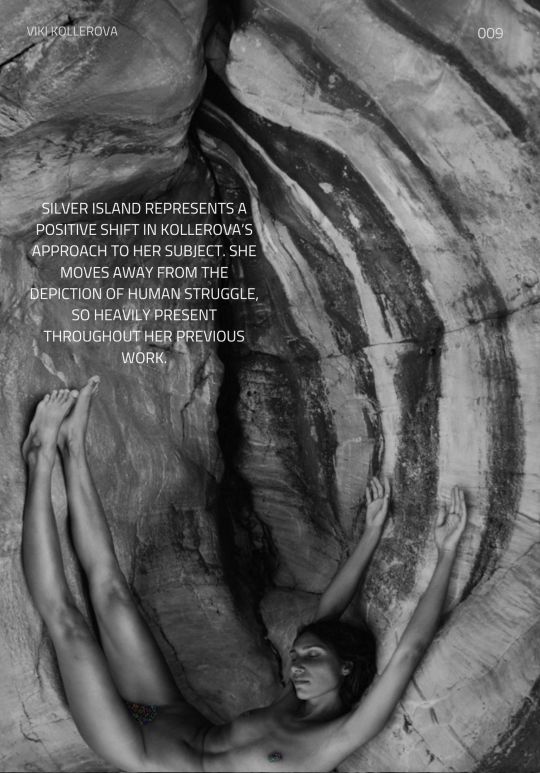

Born in Czechoslovakia, into a family of a plant virologist and an internationally recognized climber.

After finishing her MA in Translation and Interpretation, Viki Kollerová continued her postgraduate studies focused on semantics and eventually abandoned the academic life to the passion for photography in 2009.

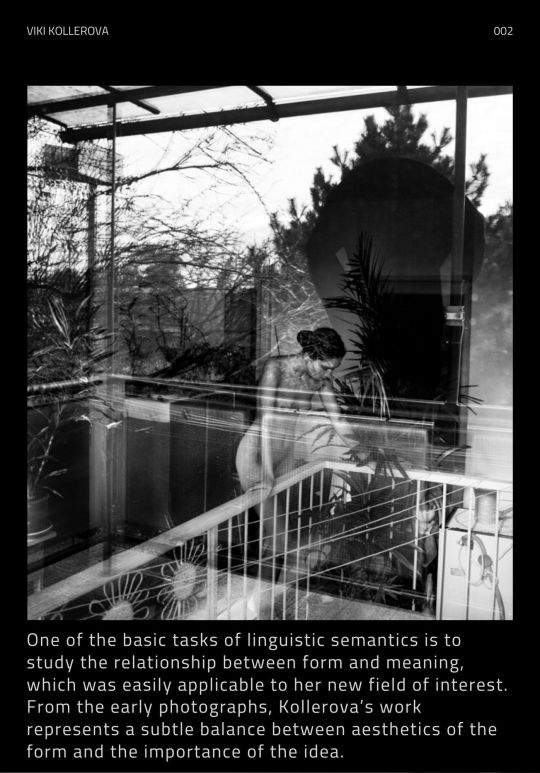

One of the basic tasks of linguistic semantics is to study the relationship between form and meaning, which was easily applicable to her new field of interest. From the early photographs, Kollerova’s work represents a subtle balance between aesthetics of the form and the importance of the idea.

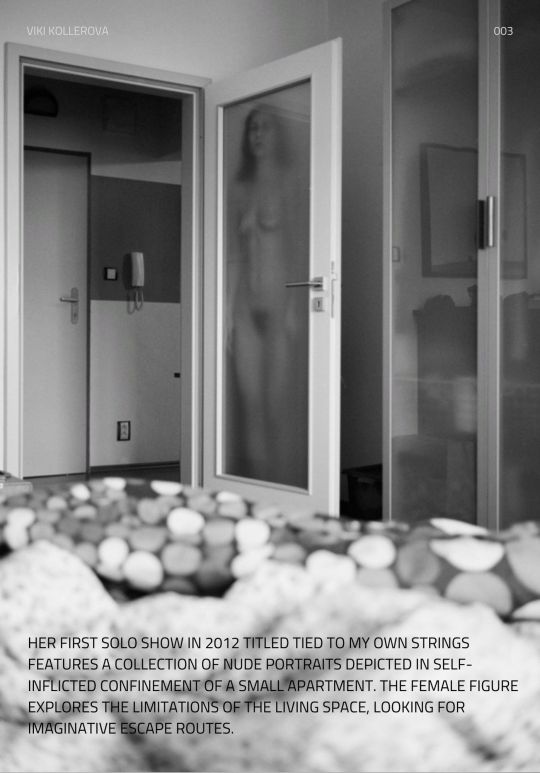

Her first solo show in 2012 titled Tied To My Own Strings features a collection of nude portraits depicted in self-inflicted confinement of a small apartment. The female figure explores the limitations of the living space, looking for imaginative escape routes.

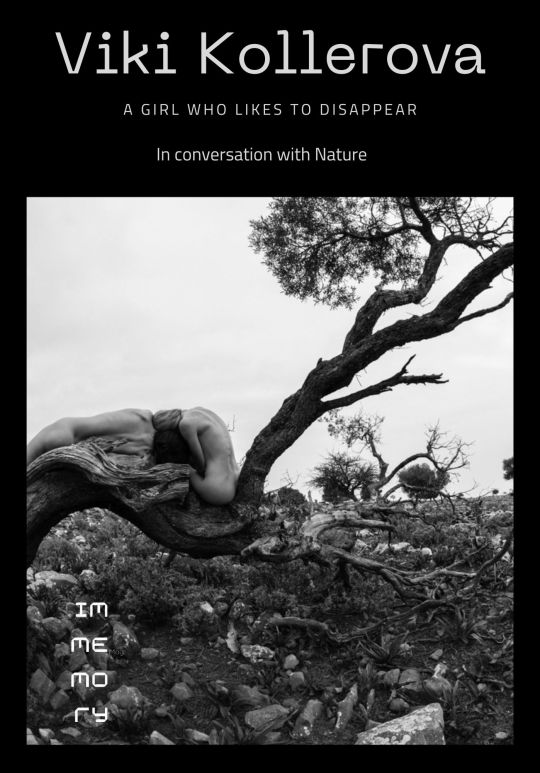

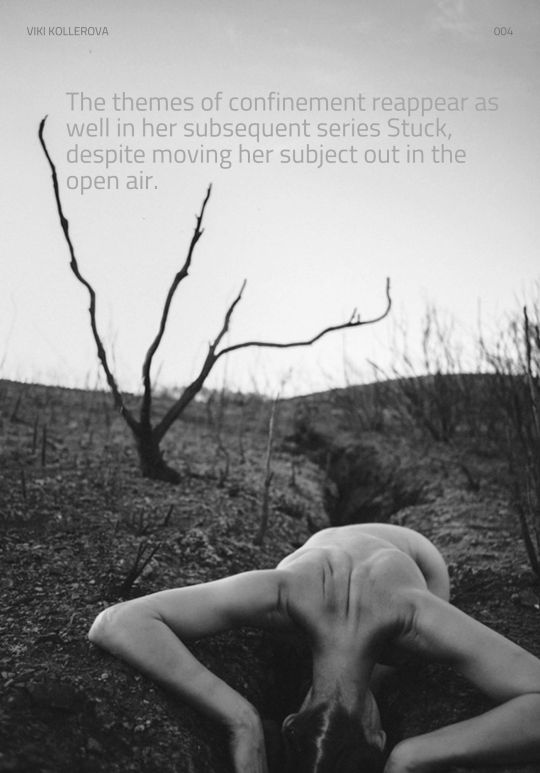

The themes of confinement reappear as well in her subsequent series Stuck, despite moving her subject out in the open air. Photographing in nature initially brought to Kollerova’s work the notions of vulnerability and helplessness of the human being, appearing small in the overwhelming surroundings.

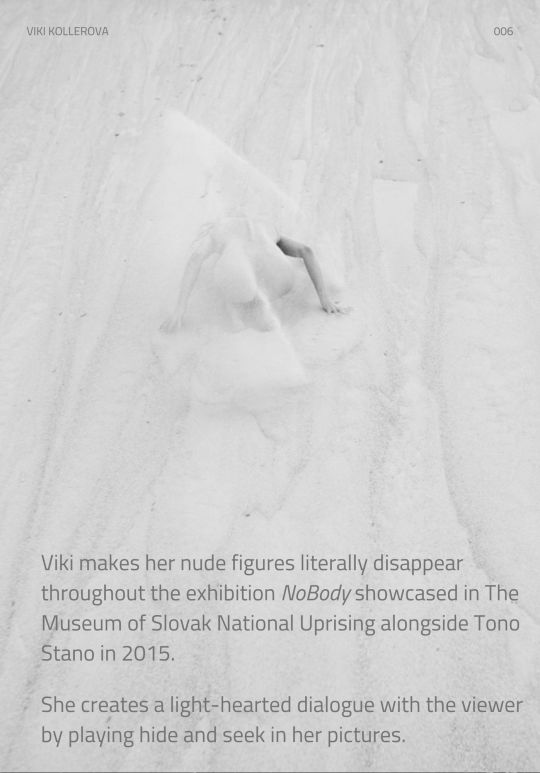

Viki makes her nude figures literally disappear throughout the exhibition NoBody showcased in The Museum of Slovak National Uprising alongside Tono Stano in 2015.

She creates a light-hearted dialogue with the viewer by playing hide and seek in her pictures.

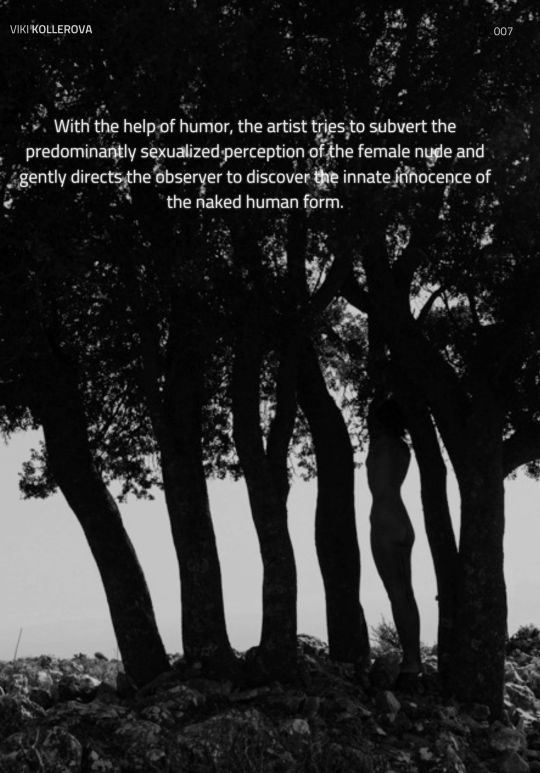

With the help of humor, the artist tries to subvert the predominantly sexualized perception of the female nude and gently directs the observer to discover the innate innocence of the naked human form.

In 2020, eleven works from Kollerova’s largest series Silver Island were selected by Fotografiska Museum for the exhibition NUDE, first opened in Stockholm in 2021 and later moved to New York. With the subtitle - The Naked Body In Contemporary Photography, the exhibition shows 30 artists from different countries, exploring the nude from a feminine perspective.

Silver Island represents a positive shift in Kollerova’s approach to her subject. She moves away from the depiction of human struggle, so heavily present throughout her previous work.

‘My human being is no longer trapped or overwhelmed by the immensity of the environment but a natural part of it.’

‘By finding comfortable poses in uncomfortable places and mimicking the shapes of geological formations and trees, I invite the viewer to see the human, represented by my physical body in both its strength and vulnerability, as perfectly fitting to the all-embracing roughness of nature.’

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bratislava, or Prešporok (Pressburg, Poszony)? Which One Is The Real Name of Slovakia's Capital City?

Good morning everyone,

Let me begin my blog, "Around Slovakia with Jakub Sevcik," with the Slovakia's Capital City. Did you know that all these names mentioned above have been used for Slovakia's capital throughout history? Today, we call this city Bratislava. It’s Slovakia’s administrative, cultural, and economic center, located in the southwestern part of the country along the Danube River.

(Panorama of Bratislava taken by me)

We will begin the day at the Bratislava Castle and its surrounding gardens. Bratislava Castle once served as the residence of important figures in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Currently the castle serves as a representative venue for the Slovak Parliament and houses collections of the Slovak National Museum. In front of the castle, you’ll find a large Statue of Svätopluk, a key historical figure in the region that is now Slovakia. Bratislava Castle also provides beautiful views on the Danube River and the whole city of Bratislava.

(Photo of Bratislava Castle taken by me)

From Bratislava Castle we will move on to Slavín Monument. Slavín is a memorial and cemetery in Bratislava, honoring soldiers who died liberating the city in April 1945 during World War II. It’s a peaceful site worth visiting to honor those who fought for our freedom.

(Photo of Slavín Monument taken by me)

After visiting this memorial we will go to the Old Town of Bratislava. This historic part of the city features monuments such as St. Martin’s Cathedral, where the famous Queen Maria Theresa was crowned; Grassalkovich Palace, the residence of Slovakia’s President; the Blue Church; Michael’s Gate; the historic Slovak National Theatre building; and the well-known Slovak Radio Building, shaped like an upside-down pyramid, along with many other Baroque-style buildings.

(Photo of Grassalkovich Palace taken by me)

To finish our first day we will visit a little bit more modern and more luxurious part of Bratislava which is located by the banks of the Danube River. First, we’ll take a walk along the banks of the Danube River, where you can see the Statue of M. R. Štefánik, one of the most important figures in Slovak history, and admire the modern architecture while watching a beautiful sunset over the river. We’ll end the day at the UFO restaurant, located on a top of the SNP Bridge (Slovak National Uprising Bridge), where we can enjoy fine dining while taking a look at breathtaking night views of Bratislava.

(Photo of Sunset over Danube River & Slovak National Uprising Bridge with UFO Restaurant taken by me)

Have you ever been to Bratislava? What was/would be your favorite to-go spot in Bratislava? Let me know in the comments!

That wraps up our first adventure in Bratislava! Whether you're into history, stunning architecture, or modern city vibes, this city has it all.

Tomorrow, we will dive into the region of Slovakia where I grew up! Stay tuned!

Best,

Jakub The Traveler

Great YouTube videos about Bratislava:

Bratislava from Drone: https://youtu.be/LhZr86v8vRM?si=GH7eM0y9v2MmZvUo

Top 17 Things To Do in Bratislava: https://youtu.be/VWVR3AZhrdI?si=eXfmVSWHmo-SF-dy

Articles & Information to the places we were visiting today:

History of Bratislava: https://www.visitbratislava.com/about/culture-and-history/

Bratislava Castle: https://www.visitbratislava.com/places/bratislava-castle/

Slavin monument: https://slovakia.travel/en/slavin-bratislava

Old Town monuments:

St. Martin’s Cathedral: https://www.visitbratislava.com/places/st-martins-cathedral/

Grassalkovich Palace: https://www.visitbratislava.com/places/grassalkovich-palace/

Blue Church: https://www.visitbratislava.com/places/blue-church/

Michael’s Gate: https://www.slovakia.com/sightseeings-museums/michaels-gate/

Old Building of Slovak National Theatre: https://www.visitbratislava.com/places/opera-slovak-national-theatre/

Slovak Radio Building “Upside Down Pyramid”: https://www.visitbratislava.com/places/slovak-radio/

Modern Part of the City by Danube: https://www.visitbratislava.com/about/modern-city-on-the-danube/

UFO Restaurant: https://www.visitbratislava.com/places/ufo/

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Slovak National Uprising (SNP) is one of the most significant moments in the history of Slovakia, when the Slovak people stood up against the authoritarian regime and the German occupation. This armed resistance, which broke out on August 29, 1944, is a symbol of courage and national pride. However, as ethnographer and historian Zuzana Kumanová points out, the important role that the Roma played in the uprising is often forgotten. “The Roma, just as they were part of Slovak society, were also part of the resistance movement,” says Kumanová. According to her, some Roma joined the army directly, while others joined the partisans, where they fought with weapons in hand. “Many communities became involved in the effort, whether by providing shelter, helping with supplies, or assisting injured and sick partisans,” she adds. This assistance undoubtedly had enormous significance for the course of the uprising, but it also brought cruel consequences for the Roma communities themselves.

Kumanová further explains that it was during this period that Roma communities were being massacred, often unjustly accused of aiding the insurgents. “There were massacres of Roma communities, especially those accused of providing help, whether real or imagined,” she emphasizes.

LOSSES AND VICTIMS

The exact number of Roma who actively participated in the uprising is unknown, as records were not kept based on ethnicity. However, Kumanová estimates that “in central Slovakia, almost every settlement saw young people, especially young men, leave for the mountains to assist the insurgent army.” The estimated number of Roma victims after the suppression of the uprising is tragic. “These victims are estimated to be around 1,000 people,” states Kumanová, referring mainly to victims from large communities such as Ilia and Čierny Balog, as well as individual executions, where “they were either transported to mass execution sites in the German-controlled Kremnička or Dolný Turček,” Kumanová said in an interview with Gipsy Television.

A FORGOTTEN CHAPTER OF HISTORY

According to Kumanová, the participation of Roma in the Slovak National Uprising is still “to some extent taboo.” Although Roma were an integral part of all significant events in Slovak history, society often does not give them the recognition they deserve. “Society doesn’t realize that Roma are part of all processes, just as it doesn’t realize that Roma were part of 1989 or 1968,” she points out. Even the significance of their participation in the uprising went unrecognized for a long time. Kumanová recalls that “a memorial plaque dedicated to the partisan movement or to Roma partisans was only unveiled at the Museum of the Slovak National Uprising in 2016,” thanks to the initiative of the museum’s then-director, Stanislav Mičev. This insufficient recognition and awareness of the contribution of the Roma in the Slovak National Uprising is, according to the ethnographer and historian, alarming. Kumanová believes that if this topic is not discussed, the Roma will continue to be perceived only as a marginalized community. “This is something we need to build upon, otherwise the Roma will remain only those in excluded communities,” she adds.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

- mit csinálsz?

- vizet rajzolok a szlovákoknak

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Museum of Slovak national uprising

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Memorial and Museum of the Slovak National Uprising, Slovakia

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

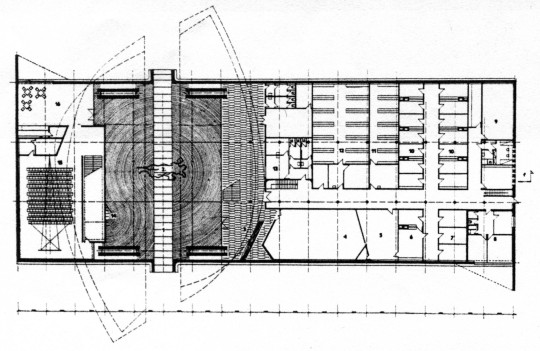

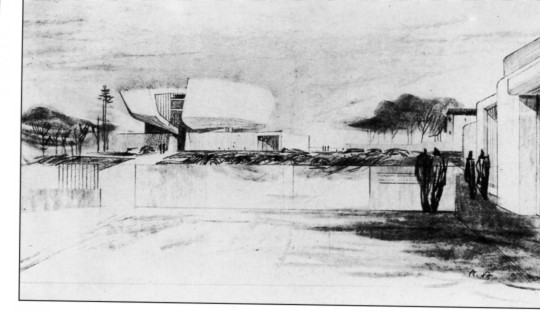

Dusan Kuzma, Memorial and Museum of the Slovak National Uprising, Banská Bystrica, Slovakia, 1963.1970 https://www.register-architektury.sk/en/objekt/272-monument-to-the-slovak-national-uprising

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Memorial and Museum of the Slovak National Uprising, by architect Dušan Kuzma, 1963-1970

154 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Memorial and Museum of the Slovak National Uprising, by architect Dušan Kuzma, 1963-1970. Banská Bystrica, Slovakia.

How Slovakia’s Soviet Ties Led to a Unique Form of Sci-Fi Architecture

Photographer: Stefano Perego

Residential building, by architects Štefan Svetko and Julián Hauskrecht, 1968-1974. Bratislava, Slovakia

University of Agriculture, by architects Vladimír Dedeček and Rudolf Miňovsky, 1960-1966. Nitra, Slovakia.

Technical University, by architect Vladimír Dedeček, 1984. Zvolen, Slovakia.

#slovakia#soviet union#architecture#sci-fi architecture#buildings#culture#history#memorial and museum of the slovak national uprising#dusan kuzma#architect#banska bystrica#stefano perego#photographer#stefan svetko#julian hauskrecht#bratislava#ufo#university of agriculture#nitra#vladimir dedecek#rudolf minovsky#technical university

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Museum of the Slovak National Uprising, Banská Bystrica, 1969. From the Budapest Municipal Photography Company archive.

202 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Museum of the Slovak National Uprising, Banska Bystrica, Slovakia, built in 1969… Museum of the Slovak National Uprising, Banska Bystrica, Slovakia, built in 1969 Architect: Dušan Kuzma Sculptor Jozef Jankovič.

#_BA_CU#architecture#architecturephotography#banska#banskabystrica#bystrica#museum#national#slovak#slovakia#socarchitecture#SocHeritage#socialistarchitecture#SocialistModernism#uprising

0 notes

Text

The Museum of the Slovak National Uprising (SNU) by Dušan Kuzma.

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

The House of Tiles in Slovakia

The National Museum of Slovakia was opened in the early 2000s and was finished in 2014. The first floor of the building features a permanent exhibition of works by artists from around the world, including Sam Francis, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Karel Appel, and Hermann Nitsch. The exhibition is a good place to see the country's artistic history. You can also visit the House of Tiles to view a collection of ceramic tiles and ceramic art. You can find more information about choosing a dlažba.

The main square in Bratislava is a lively meeting place. Here you can enjoy an afternoon stroll and relax. The square has a long history and serves as a center of city activity and a renowned residence. While you are here, be sure to take a moment to relax in the square or visit the Slovak National Uprising Square, where you can take in some art. It also offers plenty of opportunities for shopping.

The city's UNESCO World Heritage Sites are definitely worth a visit, especially the castle. The castle is situated on a sandstone outcrop, and features many early Central European lead sculptures. The museum houses a collection of tiles that were carved from these stones, and the castle also contains a reconstructed medieval Bishop's dwelling. The castle has several tours available to explore the historic landmark.

For those interested in history and culture, the Sulov Mountains feature an impressive ruined castle. Located 664 meters above sea level, the castle's origins date back to the 13th century. The four-story tower, which is believed to have been built by the Balas family, was extended into a three-tiered fortification later in history. There is even a museum dedicated to the history of the town's defensive walls.

The National Museum of Slovakia is a place to explore the history of the country. It includes a large collection of ceramic tiles and a reconstructed Soviet transport plane. Both buildings are connected by a bridge. The museum also has a small art gallery located in the women's gallery. The synagogue is another important place of worship in Slovakia. A museum dedicated to the uprising commemorates twelve councillors who sacrificed their lives in defending the city.

One of the most interesting and beautiful historical landmarks in Slovakia is the Banska Stiavnica Calvary. During the holiday season, you can take part in festive Christmas markets in the area. And if you're looking for a place to sit and admire the beauty of the town, visit the Slovak National Uprising Square. It's one of the most popular landmarks in the country. Its unique architectural design and rich history make this place an exceptional destination.

1 note

·

View note