#morphology of the new language. the words have thus been changed but as such are often still recognizable as words of foreign origin)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Chomsky's single-step theory

According to Noam Chomsky's single-mutation theory, the emergence of language resembled the formation of a crystal; with digital infinity as the seed crystal in a super-saturated primate brain, on the verge of blossoming into the human mind, by physical law, once evolution added a single small but crucial keystone.[87][88] Thus, in this theory, language appeared rather suddenly within the history of human evolution. Chomsky, writing with computational linguist and computer scientist Robert C. Berwick, suggests that this scenario is completely compatible with modern biology. They note that "none of the recent accounts of human language evolution seem to have completely grasped the shift from conventional Darwinism to its fully stochastic modern version—specifically, that there are stochastic effects not only due to sampling like directionless drift, but also due to directed stochastic variation in fitness, migration, and heritability—indeed, all the "forces" that affect individual or gene frequencies ... All this can affect evolutionary outcomes—outcomes that as far as we can make out are not brought out in recent books on the evolution of language, yet would arise immediately in the case of any new genetic or individual innovation, precisely the kind of scenario likely to be in play when talking about language's emergence."

Citing evolutionary geneticist Svante Pääbo, they concur that a substantial difference must have occurred to differentiate Homo sapiens from Neanderthals to "prompt the relentless spread of our species, who had never crossed open water, up and out of Africa and then on across the entire planet in just a few tens of thousands of years. ... What we do not see is any kind of 'gradualism' in new tool technologies or innovations like fire, shelters, or figurative art." Berwick and Chomsky therefore suggest language emerged approximately between 200,000 years ago and 60,000 years ago (between the appearance of the first anatomically modern humans in southern Africa and the last exodus from Africa respectively). "That leaves us with about 130,000 years, or approximately 5,000–6,000 generations of time for evolutionary change. This is not 'overnight in one generation' as some have (incorrectly) inferred—but neither is it on the scale of geological eons. It's time enough—within the ballpark for what Nilsson and Pelger (1994) estimated as the time required for the full evolution of a vertebrate eye from a single cell, even without the invocation of any 'evo-devo' effects."[89]

The single-mutation theory of language evolution has been directly questioned on different grounds. A formal analysis of the probability of such a mutation taking place and going to fixation in the species has concluded that such a scenario is unlikely, with multiple mutations with more moderate fitness effects being more probable.[90] Another criticism has questioned the logic of the argument for single mutation and puts forward that from the formal simplicity of Merge, the capacity Berwick and Chomsky deem the core property of human language that emerged suddenly, one cannot derive the (number of) evolutionary steps that led to it.[91]

The Romulus and Remus hypothesis

See also: Recursion § In language, and Prefrontal synthesis

The Romulus and Remus hypothesis, proposed by neuroscientist Andrey Vyshedskiy, seeks to address the question as to why the modern speech apparatus originated over 500,000 years before the earliest signs of modern human imagination. This hypothesis proposes that there were two phases that led to modern recursive language. The phenomenon of recursion occurs across multiple linguistic domains, arguably most prominently in syntax and morphology. Thus, by nesting a structure such as a sentence or a word within themselves, it enables the generation of potentially (countably) infinite new variations of that structure. For example, the base sentence [Peter likes apples.] can be nested in irrealis clauses to produce [[Mary said [Peter likes apples.]], [Paul believed [Mary said [Peter likes apples.]]] and so forth.[92]

The first phase includes the slow development of non-recursive language with a large vocabulary along with the modern speech apparatus, which includes changes to the hyoid bone, increased voluntary control of the muscles of the diaphragm, the evolution of the FOXP2 gene, as well as other changes by 600,000 years ago.[93] Then, the second phase was a rapid Chomskian single step, consisting of three distinct events that happened in quick succession around 70,000 years ago and allowed the shift from non-recursive to recursive language in early hominins.

A genetic mutation that slowed down the prefrontal synthesis (PFS) critical period of at least two children that lived together.

This allowed these children to create recursive elements of language such as spatial prepositions.

Then this merged with their parents' non-recursive language to create recursive language.[94]

It is not enough for children to have a modern prefrontal cortex (PFC) to allow the development of PFS; the children must also be mentally stimulated and have recursive elements already in their language to acquire PFS. Since their parents would not have invented these elements yet, the children would have had to do it themselves, which is a common occurrence among young children that live together, in a process called cryptophasia.[95] This means that delayed PFC development would have allowed more time to acquire PFS and develop recursive elements.

Delayed PFC development also comes with negative consequences, such as a longer period of reliance on one's parents to survive and lower survival rates. For modern language to have occurred, PFC delay had to have an immense survival benefit in later life, such as PFS ability. This suggests that the mutation that caused PFC delay and the development of recursive language and PFS occurred simultaneously, which lines up with evidence of a genetic bottleneck around 70,000 years ago.[96] This could have been the result of a few individuals who developed PFS and recursive language which gave them significant competitive advantage over all other humans at the time.[94]

0 notes

Text

dutch linguist voice adapted loanwords? you mean bastard words? how scandalous that words are getting derived from another languages without getting married! linguistic processes these days >:/

#linguistics#dutch#happened upon this term while studying and I just think it's funny#it implies the existence of legitimate words. or word marriage#word marriage equality#(from the dutch wikipedia page (translated): a bastard word is a loanword whose original form has been adapted to the spelling phonology or#morphology of the new language. the words have thus been changed but as such are often still recognizable as words of foreign origin)#(idk how to translate als dusdanig but whatever. google says it's as such)#idk if there's an english term for it but I couldn't find it with my googling#languageposting#lang#elli rambles#I should. really get to studying#I have done fuckall all day#dutch on main

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

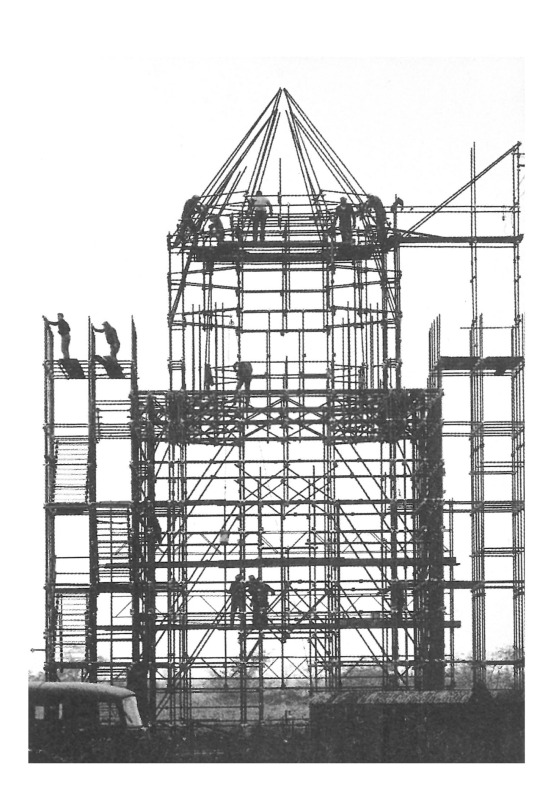

Teatro del Mondo: An Odyssey

The Venice Biennale is an increasing magnet for professionals and laypersons alike, as evidenced by a stampede of hundreds of thousands of visitors quickly rolling over exhibitions in Giardini dell’Arsenale, and an exponentially growing number of various minor events during the Mostra.

Arnell, Peter and Scully, Vincent (1985): Aldo Rossi-Buildings and projects. Rizzoli International Publications, Inc. New York.

People from all over the world travel to Venice to visit the Biennale. But it happened just once that a pavilion intended for Biennale went in the opposite direction. The motives for this voyage were reported on the sidelines of an exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 1979-1980: The Theater of the World Singular Building. Maurizio Scaparro curated the show that was held in Ca’ Giustinian in 2010.

Read also “In Vino Veritas Biennale Style!” and Is It Possible To Exhibit Architecture?

It is always difficult to judge a piece of great contemporary architecture: From the vantage point of present, we usually lack proper temporal distance. But 30 years after its implementation, Il Teatro del Mondo (The World Theater) - a floating building designed by Aldo Rossi for the architectural Biennale once anchored in front of Punta della Dogana and created in 1979 for the Venice and the Stage Space exhibition, grew to become an architectural icon.

Il Teatro del Mondo by Aldo Rossi | Photo via Focusdamnit

British theatre director Edward Gordon Craig once said: “There is something so human and so poignant to me in a great city at a time of the night when there are no people about and no sounds. It is dreadfully sad until you walk till six o’clock in the morning. Then it is very exciting.”[1] In his stage designs, Craig used architectural language to design and articulate the relationships in space between movement, sound, line, light, and color, enabling actors to assume positions and spatial relationships that they could use in ordinary urban life.

A parallel to Rossi's architectural project is unmistakable - was that a coincidence or intention?

Venice-Dubrovnik, a diary of the international theatre lab 1980 from “Giornale di Bordo”. | Photo © Daniela Sacco

In Dubrovnik | Photo © Piero Casadei

Its legendary trip to Dubrovnik, (the theater was ferried in the summer of 1980 to the local Theatre Festival) is exciting and feels like reading Homer’s Odyssey. In the best tradition of Venetian mobility, Rossi wrote: "Just the image of Venice, a synthesis of gothic and misty landscapes and oriental inserts or transpositions, fixes the capital of the city on the water. Therefore, of the possible passages, not only physical or topographical, between the two worlds. Even the Rialto bridge is a passage, a market, a theater. "[2]

Arnell, P. and Scully, V. (1985): Aldo Rossi-Buildings and projects. Rizzoli International Publications, New York.

Today, when we think about Venice, we conjure up a small peninsula in the northern Adriatic. It is hard to imagine that Venetians were able to rule such a vast cultural space. The key was their legendary mobility. They were always on the move. The Republic built on the water developed its eclectic cultural influence through its enduring presence in the Adriatic and the Mediterranean. The city was the final destination for the most important cultural and caravan route between the Orient and the Occident. No wonder The World Theater united in itself several references: Renaissance and Elizabethan theaters, lighthouse architecture, Venetian floating architecture, and temporary structures built for the carnival. [3] As Nadine Labedade wrote "Thus, it is the typology of the city that creates the scenario. And this mobile theater-boat became a fragment of the urban history, a quasi-metaphysical image tasked with representing architecture.”

The revision of modernity - as an abstract, functionalist, and timeless architectural language - was a common denominator of the Tendenza, the group formed by Also Rossi together with Carlo Aymonino, Paolo Portoghesi and Franco Stella among others. Rossi was undoubtedly the most influential member through his book L’architettura della città (The Architecture of the City, 1966). Through descriptions of Italian cities, he described his concept of architecture. He saw his work as part of an urban structure in constant dialogue with the countless layers of history, a city in continuous change in analogy to its buildings, and adapting to new social, economic, and cultural conditions.[4] His design language is generally understandable, using simple geometries and academic elements borrowed from the past. His layouts reintroduced imagination and poetry into the presentation of architectural work: colorful collage, wooden models, the mixed scales of shapes that can be both design objects and real houses.

There were just a few performances in the floating Teatro del Mondo that Rossi built for the Venice Biennale in 1979. After the short display in the lagoon and the voyage across the Adriatic to the Croatian city of Dubrovnik, the temporary theatre was disassembled. Nevertheless, this scenography-like building shaped the Italian architecture of the second half of the 20th century like no other project. The relocation to Dubrovnik, the famous medieval Republic and archrival of Venice in the Adriatic, inspired discussion about eclectic cultural influence and the complex historical layers of Adriatic cities. Those years coincided with the beginning of the Postmodern movement in former Yugoslavia. It probably was not Rossi’s primary focus of attention, but this Trojan Horse disguised as a theater that was shipped to Dubrovnik, was the first step in a politically delicate debate and movement towards a revision of Modernism in Yugoslavia - no easy feat in the ideologically colored cultural character of a country unconditionally committed to Modernism. Theater as a revolutionary tool in urban planning?Notabene: in 1956 the city of Dubrovnik even hosted CIAM X, the congress. which saw the start of the Team 10.

Peter Brook, who directed Hamlet in Dubrovnik, said that "a theatre should be like a violin, its tone coming from its period and age".[5] His daughter Irina took her Midsummer Night's Dream to the Old City of Dubrovnik’s Marin Držić Theatre, one of the oldest institution of its kind in Croatia.

Arnell, P. and Scully, V. (1985): Aldo Rossi-Buildings and projects. Rizzoli International Publications, New York.

The Dubrovnik Shakespeare Festival was founded in 2009 by American-Croatian author Michael Lederer. Suddenly, Dubrovnik and its architecture are increasingly associated with the stage on which everyone plays a distinct role in his or her daily live. On an urban scale, the morphology of the Old Town itself reminds us of a stage, surrounded by the natural slopes of the adjacent hills, with the eternal blue of the Adriatic in the back. The topography places the architecture in the foreground and the architecture has taken over the nature so dramatically that the two have become indivisibly connected.

Finally, Rossi´s vision worked out: cultural and geographic lines connected the Adriatic cities together over the last decades. The voyage of the Teatro del Mondo can coincidentally be seen as a rediscovery of the medieval stage setting of Dubrovnik, which serves as shooting location for renowned TV-series and a dream destination for thousand of tourists. Rossi must have had the words of Japanese playwright Yukio Mishima in his mind when he said that life is nothing but a theater. [6]

***

VAB 02: Mladen Jadrić

Photo © Jakob Mayer

Mladen Jadrić is teaching and practicing architecture in Vienna, Austria as the principal of JADRIC ARCHITEKTUR. He has realized a wide range of projects of different scales: architectural and urban design projects, housing, residences, art installations and Museums in Austria, USA, Finland, China and South Korea. He is teaching at the TU Wien and has gained extensive experience as a visiting professor and guest lecturer in Europe, USA, Asia, South America and Australia. His work has been awarded the Outstanding Artist Award for experimental tendencies in architecture in Austria. He is also a member of the Künstlerhaus in Vienna, and deputy Section Chair of the Federal Chamber of Architects.

Notes: 1. E. G. Craig (1998): A Vision of Theatre, Christopher Innes, York university, Ontario, Canada. 2. 1998 OPA N.V. Published by license under the Hardwood Academic Publishers imprint, part of The Gordon and Breach Publishing Group 3. Observations on the Fantastic Nature in the Architecture of Aldo Rossi, Alessandro Dalla Caneva, Architectoni.ca 2018, Online 4 4. Rossi - Autobiografia scientifica, Milano, Nuova Pratiche Editrice, 1999 5. Eyre R. (2004): National Service: Diary of a Decade at the National Theatre 6. Mishima Y. (2018): Bekenntnisse einer Maske, Kein&Aber, Zürich

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Guide to Albion Pt. 1: Words and Numbers

This guide is written for a reader from our universe. Yet it describes a reality that exists parallel to it that possesses numerous fundamental differences. Of foremost importance amongst these are language, numbers, and systems of quantification. This necessarily raises questions concerning how one talks about this other place, how it sounds, and how it looks written down.

Broadly speaking, there are two approaches: translate everything and translate nothing. They represent two ends of a sliding scale. Translating everything into words and concepts from our world with which you, the reader, are familiar comes at the cost of distortion and dissemblance. It obscures what is different. Conversely, translating everything is an exercise in academic obscurantism that renders little in a manner that can be comprehended. Furthermore, it would be disingenuous not to acknowledge the fictional character of The Chiasmic universe and, thus, the creative licence that exists.

Despite appearances to the contrary, I have little interest as an author in devising a completely new language from beginning to end and absolutely none in writing a story which, in the manner of Tolkien or Star Trek, excessively indulges such flights of fancy. To do so in any comprehensive and coherent fashion necessitates inventing not only one language but additionally reconceiving its entire historical influence on others. But, on the other hand, people there definitely don’t speak like us. Their history has so many differences, it would be impossible to see how they could.

We might call the lingua franca of contemporary Albion “Brytanic”. In terms of global prevalence and status, we might think of it as being the parallel to English. It derives predominantly from a predecessor known as Ancient Alban that was spoken in the Brytanic Isles in this reality since before the dawn of civilization. However, I imagine that it has incorporated a wide range of influences from across their globe over the years.

The earliest form of this language is a hypothetical linguistic construct known as Proto-Alban. It represents a theoretical late-Neolithic form that has been extrapolated by modern scholars in their world from what is known of the genealogy and morphological development of Ancient Alban more generally. A great deal is known because their ancient predecessors left their own “Rosetta Stone” in the form of an artefact known as the Cynmaen: a huge, intricately inscribed slate menhir some 20 metrs high and 10 metrs wide that is understood as a record of political leadership and constitution spanning more than 1,500 years of history. It is also the single most important source for students of Ancient Alban and its development over the course of their Bronze Age and early Iron Age.

The Cynmaen documents a form of the language known in the modern day as “Old Ancient Alban”. It is believed to have been spoken in the Brytanic Isles between around 1500 AM and 2800 AM. At this time, the inhabitants of the archipelago possessed a form of ideographic rune script known to archaeologists in their present day as “Runic A”. However, the precise nature of the relationship between the spoken and the written form is unknown to them, if one ever existed. Consequently, reconstruction of Old Ancient Alban is predominantly based upon references to former modes of speech in later works.

“High Ancient Alban” is considered to be the classical form of the language that took hold during their late Iron Age from ~2800 AM onwards. It is marked by the emergence of a phonetic script known as Runic B which is widely thought to have formed the basis of most modern Western alphabetic and numeral systems. The appearance of Runic B is thought to have been the result of disruptions to social, economic, and cultural practices around this time combined with the establishment of relations with Phoenician traders from the Mediterranean and Near East. It is documented through the various surviving works of history, philosophy, literature, and poetry in addition to records of it made by other cultures, notably the Illenes, with whom the Albans had contact.

“Late Ancient Alban” was a Latin-influenced form of the language that developed from the late 33th cantury following the establishment of the Roman Alliance. It was predominantly spoken throughout the southern regions of the Brytanic Isles that came to be known as Brytan. Speech and writing in the northern and far western regions generally remained closer to High Ancient Alban and this is reflected in contemporary Gaelic, Cymranic, and Cernic dialects. However, in their world, Latin itself was not unrelated to Old Ancient Alban, so the differences were not all that great.

The symbiotic decline and fall of both the Western Roman Empire and ancient Alban civilization occurred in concert with the advent of a complex and little understood historical period during which there were extensive migrations of peoples throughout Europe. Albion and its language came to be influenced by a number of cultural influxes, of which the most significant were the Saesan and, later, the Olydynan who invaded and subsequently migrated in large numbers from the coastal regions of northern Europe and Sgandinafia around the countries now known as Danmarc and Olwe.

Although many who identify as Saesan (or “Anglan”, as they call themselves) still speak their own obscure language amongst themselves, both they and the Olydynan adopted the Late Ancient Alban language and culture of the regions in which they settled, mainly Brytan.

Much as had been the case with the Romans before them, this intermingling introduced a host of new vocabulary, led to a simplification of some grammatical structures, and increased complexity in other areas.

Once again, as with Latin, the languages they brought with them were not unrelated to much earlier forms of those spoken in their newly adopted homeland. Modern Brytanic and its associated Gaelic and Cymranic dialects emerged over the course of the ensuing canturies as a result of this feedback loop. Over much the same period, it has absorbed a wealth of additional influences from across the globe, including such diverse sources as Dynolan Frantsaic, Illenic, Twrcic, Arabic, Inwic, Hindi, Gudgurati, and Urdw.

While I endeavour to remain consistent in my approach to the use of this imagined language, aesthetic considerations are typically paramount. Any “Brytanic” that is used should not be considered to constitute an accurate rendering of an alternate language. It’s a form of transliteration intended to provide an impression of difference. Generally speaking, supposedly Brytanic words are used for proper nouns, for untranslatable or problematic words and concepts (e.g. numbers, dates etc), or to draw attention to distinctions between their world and ours.

For example, it would be both facile and clumsy to talk of Clwb Troedbel Enadig o Mancar when Mancar United FC delineates more clearly the fact that one is referring to a football club located in a particular named place and suggests that the sport is basically the same thing in their world as in yours. Elsewhere, talking of Sant Cara, rather than Saint Cara, feels sufficiently close to English as to be understandable while adopting a stylistic tweak that suggests a difference in their religious inheritance that is important. By contrast, changing Mancar to “Manchester” just because it is a city that happens to occupy more or less equivalent geographical coordinates would elide an etymology that sits behind toponyms while creating the misleading impression that it is exactly the same place.

This impressionistic approach is most evident in the use of a number of English pseudo-Brytanicisms such as “cantury”, “sinade”, and “Brytanic” itself. To say “century” and “decade” would be misleading. But, in the same breath, you could use any words you want for these concepts of 144 years and 12 years that feel right to you if you so desire. Likewise, to say “Britain” (and, by extension, “British”) does not allow for the sheer extent of the difference between it and Brytan, including the simple matter of how I imagine it to be pronounced and the fact that it is a country of Albion rather than a somewhat nebulous geopolitical concept.

I would argue that, amongst other abstract properties, it is important that their numbering system is base-12, that they possess a perennial calendar and a common system of weights and measures, that their language has a syncretic quality, and that their script evolved from an ideographic system. I have represented all of that through an unholy mash-up of Celtic, Germanic, and Latin languages because I think that works aesthetically. But there is nothing necessary about it. Since this world projects a past in which this supposed Alban cultural root occupied northwestern Europe and collided with an Indo-European root, none of those languages I’ve used as a source would be the same in their world (even if they existed) as those I have mashed together. You may as well imagine that they speak Martian: it’s the same thing. That being said, I should probably explain how I imagine it being spoken in my own mind.

You can speak these words however you like. Personally, I like to imagine posh people in their world talking in a manner that melds Richard Burton, Anthony Hopkins, and Sean Connery with a little rhotic brogue thrown in for good measure. And everyone trills their r’s in an aspirated manner which makes it sounds as if they are auditioning for the part of Gimli in Lord of the Rings.

An “s” at the beginning of a word is almost always intended as be voiced as an “sh” (in the Gaelic manner) but more typically as an “s” sound when it appears in the middle or at the end of a word (unless it appears there as a result of a syncretic operation, such as in the names of larger numbers). By contrast, “sc” at the start of a word is a hard “sk” sound but a soft “sh” when in the middle or at the end.

The letter “i” is always long (as in “queen”). They use the letter “e” for the short “e” sound (as in “bet”) but “y” for the slightly elongated equivalent (as in “air”), much as Italian distinguishes between “é” and “e”. “A”, “o” and “u” are always short, as in “bat”, “got”, and “but”. They use the letter “w” for the “oo” sound which, if you listen carefully, almost always has a little “w” sound before or after it in English (and vice-versa when we say “w”). The exceptions are the digraphs “ae” (pronounced “a” as in “hay”), “ei” (“i” as in “eye”), “oa” (“o” as in “hoax”), and “ou” (“ow” as in “rowdy” but leaning more toward “oh-uh” than “oh-woo”).

They do have the letters “j”, “q”, “k”, “x”, and “z” but they are very rare and exotic imports, usage of which is considered to be somewhat pretentious. It is more common to use the digraph “dg” in place of “j” as in “judge” and “ia/io” etc for “ya/yo” and so on. A soft “j”, as in the French “je”, typically becomes an “s” that is pronounced “sh”.

When it appears on its own, “g” is always hard but pronounced “ñ” as in “new” when combined as “gn” and as a soft Greek-style gamma in the “gw” and “gh” digraphs. Likewise, “c” is always hard unless it appears as “ch”, in which case it is pronounced as in the Scottish “loch”. Imported words, often Frantsaic, that use a soft “ch” tend to be rendered in Brytanic as an “s” and pronounced “sh”. The hard “ch”, as in “chuff”, also typically imported, is usually rendered and pronounced as “ts”.

The “q” sound in “queen” is written “cw”. However, somewhat confusingly, that particular digraph can also be pronounced “coow”, as in cwrmi, which is their word for beer. It’s one of those things where you just have to know which is used for any particular word. Either way, the sounds are not that far apart if you listen to them carefully.

Foreign words that use “x” or “z” are generally rendered in Brytanic with “ch” and “s” (although some regional accents, especially in the southwest, consistently pronounce “s” as “z”).

A “th” is usually meant to be hard, as in “think”. The “dd” digraph is often used to indicate a soft “th”, as in “then”. However, the latter has become archaic in recent times. The “dd” digraph is an ancient practice that has all but died out in their modern era.

Since their equivalent of our medieval period, the Brytanic language has gone through a period of considerable transition. Many words that were previously separate lexemes (such as “o” for “of”) have merged into their neighbours over time in common use cases as a result of lenition. Extensive immigration and mixing of populations has changed or softened some of the more distinctive phonemes. For example, the “ll” voiceless alveolar lateral fricative has transformed in many cases into just an “l” sound (rather than “ch-l”). Where it remains in use, it has often come to be spelled “chl”.

Similarly, historical distinctions between dialects in the use of “ff”, “f”, and “v” in writing means that rendering these in text is wildly inconsistent. Where the “Brytanic” are thought to have traditionally voiced “s” and “f”, their near continental neighbours have “z” and “v”. However, this is very much a matter of accent and dialect. Even where they might all still speak the same way, a “Latin tendency” sometimes prevails amongst certain sections of the educated classes leading to an increased use of “v” and “z”. At the same time, others keen to follow a putative “nativist precedent” promoted “s”, “f”, and “ff” for the same reasons. Ultimately, I imagine that they’ve become largely interchangeable, although it is a confusing matter of pronunciation for people in their world. Regardless, the “Latin tendency” is more “modern” and I reflect that in my transliterations by occasionally using different spellings depending on the historical context in which a word is being used.

No such confusion exists around the pronunciation of the “bh” digraph though. It is definitively a Gaelic-style “v” sound. This is partly because it has always belonged to dialects of the north and west that have not been historically subject to such extensive continental influence.

In addition to pronunciation and spelling, a fair degree of confusion also persists into their present day around grammar. Ancient Alban was a right-branching language with a verb-subject-object word order. So, for example, one says “read I the book” rather than “I read the book”. Modern Brytanic, by contrast, I imagine to be more left-branching. However, any “official” or “correct” approach in this regard is not universally adhered to in regional dialects and quotidian speech. And that is before we even address the matter of registers.

Like any language, Brytanic possesses a number of registers that are considered to be appropriate for use in particular contexts. The two main ones that remain notably distinct are an increasingly archaic literary-poetic register and the “standard” modern quotidian register. Just so you can get a taste of how I imagine the difference, below are pseudo-translations of the opening passage from “A Tale of Two Cities” (they have this book, too!) in both registers.

First, in the literary register:

Arda yr ansar manwe, arad yr ansar manwe, oedothi yr paellath manwe, oedothi yr foledath manwe, epocothi yr credath manwe, epocothi yr ancredath manwe, olud yr odymor manwe, tywyl yr odymor manwe, oba yr ogwanwyn manwe, anoba yr ogaean manwe, ollath widor galwnwe, nath widor galwnwe, nef gan oll sythol fyndwnwevy, oll cyfeirnir sythol fyndwnwevy.

And, by comparison, in the modern quotidian register (that Siarl Dicyns most certainly did not use himself when writing):

Manwe yr ansar arda, manwe yr ansar arad, manwe yr oed o paellath, manwe yr oed o foledath, manwe yr epoc o credath, manwe yr epoc o ancredath, manwe yr dymor o’lud, manwe yr dymor o tywyl, manwe yr gwanwyn o’ba, manwe yr gaean o anoba, galwnwe ollath dor wi, galwnwe nath dor wi, fyndwnwevy oll sythol gan nef, fyndwnwevy oll sythol nir cyfeir.

As might be observed, the difference between the registers is quite marked and represents a shift in the language over the last few hundred years from being predominantly right-branching to predominantly left-branching. Literary language writes “dark and cold the night was” whereas modern quotidian speech prefers “it was a cold, dark night”.

Literary-poetic registers also make far more extensive use of the syncretic capacity of Brytanic syntax to create neologisms through the use of prefixes and suffixes. In addition to enriching meaning through inventive use, this can help smooth out awkward conjunctions and syllables and enhance the rhythmic flow and scansion. In the hands of a skillful writer or orator, it can be powerfully evocative. However, it is easy to do it badly and come across as a pretentious windbag. But many still revere it as the language of Sigsber and the Beibl.

Where everyday speech encounters awkward conjunctions, such as “o” before a word starting with the letter O, the poetic register simply ellides the two using an apostrophe. Over time, such contractions have a tendency to become normative, with the word adopting a permanently contracted state that then becomes acceptable for use within the quotidian register. Although the translation of words from one register to another goes both ways in practice.

While it may not come adorned with poetic enhancement in everyday speech, right-branching syntax remains very common in a number of regional dialects, notably those of Belerion, Cymran, and Gaelic-speaking regions.

The only other register that has remained in widespread usage is a formal register that one uses mainly when writing official correspondence or when doing things like establishing business with new clients and suchlike. Its grammar combines the right-branching structure of the literary register with the individuated lexemes of the quotidian register. Additionally, unlike English but like other European languages in your world and theirs, it involves the use of particular pronouns and verb forms. It is polite, precise, and pedantic.

Despite all of the above minutiae, there are reams of historical and developmental aspects of the language and culture of this supposed world that I quite deliberately conceive myself to be glossing over. At the risk of becoming repetitive, that is because I want it to remain impressionistic, rather than being taken too literally. However, by their nature, numbers leave little room for such an ambiguous approach.

In the universe of Albion in their modern era, almost every nation on earth utilises the base-12 numbering system that was a distinctive feature of the culture of the Brytanic Isles in ancient times. Please be aware that all numbers referred to throughout this guide are base 12 values unless explicitly mentioned otherwise.

In other words, wherever you see the number “10” it actually refers to the numeric value you think of as “12”. This extends all the way up and down the positive and negative integer scale. Thus the number “100” actually means a base 10 value of 144, “1000” a value of 1728, and so on. Moreover, in the chiasmic universe of Albion, there is no abuse of billions and suchlike. They have long billions and long trillions. The equivalent to one billion in their universe is a million million, not a thousand million. By extension, a trillion is a billion billion. Even when they talk about money. There are no US dollar billionaires. Yet.

Obviously, this also means that fractional quantities and proportional values have a different meaning. In base-12, a base-10 fractional value of “one quarter” is expressed as 0.3 and “one third” is 0.4. One of the advantages of their system is that common operations involving divisions of thirds and quarters are somewhat easier to reason about arithmetically as they don’t involve irrational numbers. As a concession to clarity, when talking of base-12 “percantages”, I use the mathematical “proportional to” symbol “∝” rather than “%”.

Given this radical difference, it is necessary at the very least to address the question of how the additional numerals are spoken, either in Brytanic or English, and how the additional two numerals are written. Since we’re dealing with numbers, the easiest way to do this is with a simple table:

Numeral (base-12) Equivalent (base-10) Brytanic Name Brytanic Ordinal English Translation 0.1 / ⅒ 0.8333.. Sinar A tenth 0.2 / ⅙ 0.1666.. Swar A sixth 0.3 / ¼ 0.25 Triar A quarter 0.4 / ⅓ 0.3333.. Petar A third 0.6 / ½ 0.5 Hanar A half 0 0 Nil, Sero Nath / 0th Zero/Nil/Nought 1 1 Ena Enath / 1th One 2 2 Do Doth / 2th Two 3 3 Tri Trith / 3th Three 4 4 Peta Petath / 4th Four 5 5 Pema Pemath / 5th Five 6 6 Swa Swath / 6th Six 7 7 Seta Setath / 7th Seven 8 8 Owt Owtath / 8th Eight 9 9 Nin Ninth / 9th Nine Ʌ 10 Dec Decath / Ʌth Dec Ɛ 11 El Elth / Ɛth El 10 12 Sin Sinth / 10th Ten 11 13 Enolasin Eleven 12 14 Dalasin Twelve 13 15 Trilasin Thirseen 14 16 Petalasin Fourseen 15 17 Pemalasin Fifseen 16 18 Swalasin Sixseen 17 19 Setalasin Sevenseen 18 20 Owtolasin Eighseen 19 21 Ninolasin Nineseen 1Ʌ 22 Decolasin Decseen 1Ɛ 23 Elvolasin Elseen 20 24 Dasin Twendy 30 36 Trisin Thirdy 40 48 Petasin Fourdy 50 60 Pemasin Fifdy 60 72 Sawsin Sixdy 70 84 Setasin Sevendy 80 96 Owtsin Eightdy 90 108 Ninsin Ninedy Ʌ0 120 Decsin Decdy Ɛ0 132 Elvsin Eldy 100 144 Can (ena can) Hundred 1,000 1,728 Mil (ena mil) Thousand 1,000,000 2,985,984 Miliwn (ena miliwn) Million 1,000,000,000,000 8,916,100,448,256 Daliwn (ena daliwn) Trillion

As you will observe, I choose to just call numbers by English names except for the two additional numerals, for which I use the Brytanic words “el” and “dec”. And I also tend to use Brytanic ordinals such as “1th” instead of “1st”. Usually, I just write the numerals, rather than spell the words, so such matters are entirely up to you. But, when I say them in my head, I like to distinguish base-10 “teens” and “tys” from dozenal base-12 “seens” and “dys”. Other than that, everything is calculable.

An astute reader may have observed the Brytanic novelty of having an ordinal for the 0th position — an interesting philosophical concept, if ever there was one, and something that is indicative of their slightly different relationship to numbers. Historically, zero was a very important concept in Albion for what we might think of as “religious” reasons. Also, circles.

There are a number of other idiosyncratic aspects of their language which it is helpful to understand if one wishes to gain a view on how it highlights areas in which their thinking and attitudes are different from our own.

Brytanic is a comparatively easy language to learn. Despite countless years of historical development and diverse cultural influence, its syntax, spelling, and pronunciation remain pretty consistent. It has none of the silent letters and few of the alternate pronunciations of the same phonemes that pervade English. Yet there is a gulf between its basic and advanced use. I imagine that speaking or writing Brytanic is a bit like playing the piano. Anyone can bash out a few notes that are more or less harmonious but playing a symphony requires a great deal of skill.

Understanding the subtext present in the use of formal, literary, or quotidian forms (or their mixing and matching), the distinctness or merging of lexemes and their position relative to an operative term, a play that is being made between two words amongst a vast accretion of vocabulary. These are sophisticated skills that set apart the native speaker from the foreigner, the educated from the uneducated, the rich from the poor. They distinguish the witty from the obnoxious and the insightful from the facile and obtuse.

To many amongst the inhabitants of Albion, their language — whichever dialect they speak — is a source of pride and a badge of identity. This much is implied in its name in their language: Brytarath. The “-ar” suffix is an active verb ending equivalent to “-er” in English (which is alternate spelling for them). It suggests that one is actively being or becoming Brytanic through the act of speaking or writing in it. Furthermore, the “-ath” suffix (or “-iath” and the etymologically related “-ad” and “-iad” endings) denote that, over and above merely pertaining to something Brytanic (for which they use the “-ic” ending much as we do), it is definitive of it. Thus, Brytarath is (in a grammatical sense, at least) the definitive performance of being Brytanic. It is hierarchically positioned in a conscious manner above dialects of Brytanic and other languages that merely pertain to a particular place, such as Gaelic, Cernic, Cymric, Anglanic — or even Frantsaic (French, the official language of Gawl) and Illenic (Greek) — by means of this suffix. Clearly, such constructs have both a political and a historical dimension. For example, in their present day, there is a “woke” tendency to call the language Albanarath or Albanic.

Then there are other subtleties that are generally less offensive, politically and philosophically. Brytanic is possessed of an equal facility with scientific precision and poetic ambiguity. I have already touched on the zero ordinal. It is also possible, for example, to negate almost any concept through the use of the an- prefix. This gives rise to the fantastically idiosyncratic word anni, which means “not no”. This is a deliberately ambiguous reply that conventionally suggests “yes” while leaving room for plausible deniability.

In a similar vein, you can add fal to something, usually a verb, to indicate that it “may be or do”; yr trahen esdyth redanifal. “The train may run today”. Or maybe it won’t.

Similes (and clichés) can easily be created through the application of fel, which is very much like the Italian word “cosi” in your world and means “like so”, “in this way”, or “how” (when not a question). He redanivy trahenfel. “He is [in the process of] running like a train”.

Then there is hirath, a regular winner in their world of “favourite Brytanic word” polls of spurious legitimacy. It refers to a form of longing nostalgia or yearning for possibility. It is similar to the Almaenan concept of sehnsucht. However, it is closer to a sense of excitement for what might have been or what might be, rather than mourning. They also have oedath, which refers to the definitive character of an age or epoch, much as “zeitgeist” does.

The words for house or home (ty), household or family (tydan), and land, country or nation (tyr) are all etymologically related and homophonous. However, there are notably no “tyrs” within Albion. Brytan, Cymran, Godan, and Eirean construct their names using the -an/-dan suffix. This is a little bit like the English “-dom” but actually derives in Brytanic from ban in Ancient Alban which also gave rise to their words ben and pen (which basically mean “chief” or “head”). Historically, the -an/-dan suffix denotes the jurisdiction of ben/pen, specifically a kind of ur-chieftain that existed within the ancient constitution.

Albion itself is clearly neither a tyr nor a dan. The -ion suffix denotes a place within which something or someone resides or an activity occurs. For example, the modern day siars of Cantion and Trivantion are the vestiges of the ancient tribal territories of the Cantiacis and Trinovantis. Albion on the other hand is the place where Alba, a kind of earth god/giant was believed to actually exist. In other words, he was the foundation of the land on which the Brytanic Isles literally sat. Yet, at the same time, Alban was the first ban jurisdiction.

One could go on and on in this vein for there are inevitably countless subtleties to one of the world’s few extant languages that, along with the likes of Illenic, can legitimately claim a direct continuity with some of the earliest known forms of human speech and writing. My aim is not to document a fictional invention but to sprinkle it judiciously in order to convey the fabric of a world of which it is an integral and formative part.

It is a milieu that is pervaded by a sense of timelessness that comes from the perduring presence of an explicitly ancient lineage, such as one experiences in places like China and Greece in your world. A world in which seemingly everything is simultaneously and eternally ancient and modern at the same time in every instant.

They are people who have a speech that may be clipped and articulated or smooth and lilting depending on accent but which is always rhythmic and sonorous, as though it were in 9/8 or 12/8 time. They speak words with breath through the mouth from the stomach, and never with a nasal whine, in a manner that impacts their physiognomy, mentality, and bearing as well as their sound.

They live in a society that possesses a linguistic framework for communication in a variety of pre-established modes, even if many do not understand how to use them and even fewer how to do so well. This provides both a licence and expectation for expression that is formal or informal or lyric or poetic or precise.

Much like English, their vocabulary is multilayered with more than one word of varying origin for the same thing. Furthermore, a bit like German or Japanese in your world, it has a host of terms for subtle distinctions and ineffable concepts that have developed over aeons of conversation and literature. And their “native” words are knowingly formed from lexemes such that combinations enter into or fall out of use at a remarkable pace.

With any luck, these qualities and others will be abundantly clear through the way in which I tackle the topic of Albion and the universe of The Chiasm more generally and this entire introduction will have been unnecessary. Ideally, no use of language will be jarring — whether it is an English translation or an actual or pseudo Brytanic word — and will only serve to weave the desired background fabric. That has to be a measure of success for the description of any alternate world.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Language of Iceland

Icelandic is the de facto national language of Iceland, spoken by 319,000 Icelandic citizens. Icelandic is considered to be an Indo-European language, which is part of a subgroup of North Germanic languages. The group once numbered five languages, including Norwegian, Faroese (the native language of the Faroe Islands, which is also spoken in parts of Denmark), and Norn (formerly spoken in the northern islands of Orkney and Shetland, in the north of Scotland) and Greenlandic Norse. It is most closely related to Norwegian and Faroese, in particular the latter, the written version of which closely resembles Icelandic. Icelandic is not only the national identity of Icelandic citizens; it is also the official language of the country as adopted, but also its constitution in 2011. Iceland, as a country, is disconnected and exhibits linguistic homogeneity. It never had several languages. Gaelic was the native language of the early Icelanders in the past. Besides, Icelandic sign language is the official minority language as of 2011

Icelandic is a medium for education, although some learning does take place in other languages. It's the language of government, commercial enterprise, and the mainstream press. In addition to several TV channels, there are several Icelandic newspapers, magazines, and radio stations. There are also speakers from Icelandic in the United States, Canada, and Denmark. On the other hand, immigrants bring with them their languages. Thus, 2.72% of the population speaks Polish, 0.44% speaks Lithuanian, and 0.33% of the population speaks English approximately. Danish, Norwegian, Swedish, French, and Spanish are also very small percentages of the population present as mother tongues.

If you're looking for Icelandic Translation Services, you can reach out to us at Delsh Business Consultancy to take full advantage of your abundant business opportunities. Delsh Business Consultancy (DBC) is providing English to Icelandic and Icelandic to English translation services worldwide. At Delsh Business Consultancy, we help our clients globally with high-quality Icelandic language Translation services.

Norwegian was similar to Icelandic, but since the 14th century, it was increasingly influenced by neighbouring languages such as Swedish and Danish. Language resistance to change is so exclusive that today's speakers can understand texts and scripts such as Sagas from the 12th century. Even when Scandinavian languages were losing their inflection across Europe, Icelandic maintained an almost authentic form of old Scandinavian grammar. The native bible has further developed Icelandic. However, the language was limited until the 19th century when Iceland came together like a nation, and the Scandinavian scholars rekindled it. Stringent orthography along etymological lines has been established, and Icelandic today is very different from other Scandinavian languages.

Modern Day Icelandic Language

As far as grammar, vocabulary, and orthography are concerned, modern Icelandic has preserved the Scandinavian language in the best possible way. The language has maintained its three genders: masculine, feminine, and neuter. There are still four cases for nouns; Accusative, dative, nominative, and genitive. Although the language adopted certain terms from Celtic, Latin, Danish, and Roma, the purism of the 19th century replaced foreign words with Icelandic forms. Icelanders choose to make a new word rather than borrow it from outsiders. Icelandic has remained unchanged for many centuries, despite the adoption of certain features of the Gaelic language. The country maintained linguistic homogeneity for a long time, but with the advent of northern trade routes, the language environment changed. Traders and clergymen have introduced the English, German, French, Dutch and Basque languages to Iceland.

Icelandic is a very irregular language, with a noun morphology system that could be very unpredictable for a language learner. Verbs, on the other hand, can be modified for tense, mood, number, and person, just as they would be in most Indo-European languages. While there are four cases, most verb declinations need to be memorized. Adjectives, on the other hand, can be rejected in up to 130 different ways. But, despite how daunting Icelandic might seem, according to the Icelandic Ministry of Education, more than 200 thousand people from all over the world have accepted it, learning it, and are in awe of its rich history.

0 notes

Text

Hunting Coyotes at Night Tips

youtube

INTRODUCTION

The coyote, whose name comes from the Nahuatl (Aztec language) word coyote, belongs to the family of canines, including dogs, wolves, jackals, foxes, wild dogs.

Canids are believed to be native to North America's great plains where, 40 to 50 million years ago, in the Eocene, their common ancestor lived. Very quickly, the fox branch, Vulpes, broke away from this common trunk. A little later, in the Pliocene, the other components of canines are differentiated, notably wolves and coyotes, which, despite their close kinship, evolve separately. At the end of this period, about 2.5 million years ago, Canis esophagus appears, the ancestor of the coyotes, which must have been a little larger than the present species' animals. According to more recent Pleistocene fossils found in the United States in Maryland and the Cita Cañon in Texas, his descendants closely resemble him. They then rub shoulders with the saber-toothed tiger on the American continent, which still roams the plains.

Since this distant time, coyotes have changed little in their morphology and have slightly differentiated from their ancestors. However, the comparative study of the skulls shows that their cranium has developed, but that the frontal bone is narrower in modern animals than it was in their ancestors. Their non-specialization over the ages has allowed coyotes to colonize new spaces and to adapt to all kinds of habitats and new situations. Thus, they are hunters, but they can survive by feeding on carrion, insects, or fruit. By ridding wild herds of weaker animals and eliminating already doomed individuals, they play their part in the natural balance.

Originally probably inhabiting the Great Plains, the southwestern United States, and Mexico, coyotes have greatly expanded their habitat, which, although uniquely American, also includes deserts, mountains, and forests. And the outskirts of large cities. Thanks to man, who changed the environment and hunted wolves until their almost total extinction, their current territory is immense because they have taken over the vast areas formerly occupied.

THE LIFE OF THE COYOTE A SILENT AND INTELLIGENT HUNT The coyote is a solitary hunter that feeds on anything it can catch. In the central plains, where the climatic conditions are relatively stable, it has the same essential diet all year round, made up for more than 75% of hares. Rabbits, mice, pheasants are also among his favorite prey. Occasionally it does not disdain muskrats, raccoons, polecats, opossums, and beavers, as well as snakes and large insects.

In late summer and fall, the coyote will eat fruit that has fallen to the ground. Blackberries, blueberries, pears, apples, peanuts then represent 50% of his diet. He knows how to choose a fully ripe watermelon and cut it in half to taste its juicy pulp. Neither does he disdain the soybean meal or cottonseed meal distributed to cattle.

In more arid environments, such as Mexico, the coyote mainly hunts small rodents. It also attacks marmots and ground squirrels in Canada, ground squirrels that look like large guinea pigs. But these two species hibernate, and in winter, in these northern regions, it is forced, to survive, to become a scavenger.

In suburban or urban areas, the coyote feeds on human waste, products manufactured by him, such as dog food, or even his pets.

ALONE OR IN COOPERATION When it hears prey or spots it from afar thanks to its keen eyesight, the coyote approaches it silently, facing the wind, tail low, with slow steps interspersed with pauses. Arrived at 2 meters from his victim, he leaps on her and bites her neck. To finish her off, he keeps her in his mouth and shakes her violently. Death is quick. It usually devours the animal on the spot, even eating the bones of small prey.

When coyotes live together, they choose larger prey such as deer, elk, and other ungulates. They run around the herd. In a panic, an individual is isolated, then surrounded and attacked.

When the coyotes hunt in pairs, they force the isolated to run in a circle, taking turns to tire them out. This technique is used with caribou. The killed prey is disemboweled with claws and teeth and divided.

TWILIGHT AND MORNING HUNTERS

Twilight and morning hunters

Essentially nocturnal, the adults move around a lot, hunting more readily at dawn or dusk. On the other hand, young people between 4 months and a year old move more during the day and less at night. Their often unsuccessful hunting attempts force them to devote a lot of time to it, but they still have no territory or offspring to watch over.

SCAVENGER TO SURVIVE IN WINTER In Alaska and in several Canadian provinces, where they arrived following the gold miners in the mid-nineteenth th century, coyotes have learned to face the bitter cold of winter. In these regions, animals must live and feed when the temperature is -10 ° C. The thick fur of the Far North's coyotes covers their whole body and has the same insulating power as that of the gray wolf. The guard hairs reach 11 cm long compared to 5 cm in animals living in a warmer climate. Thick and tight, the undercoat can measure 5 cm in thickness.

But the coyote does not run well in thick snow. However, hares and rabbits do not come out of their burrows when the outside temperature is too low, and groundhogs hibernate. The coyote would not survive the winter if it did not fall back on dead animals. Feeding on all the carrion he finds, he shares them with his fellows.

However, if the wolves arrive, he must give way. He sometimes buries or hides to return to them later. Its best ally is the cold, which finishes off sick or weakened animals, often at the tail of herds of large herbivores. Thus, in winter, it therefore, moves after the latter, devouring dead ungulates. Watching for the slightest failure, he does not hesitate to give the "coup de grace" to elk or caribou, exhausted and unable to defend themselves. If the snow is not too thick and the carrion is insufficient, the coyotes will join forces to attack.

OFTEN SOLITARY, THE COYOTE PREFERS TO LIVE AS A COUPLE Halfway between the fox, solitary, and the wolf, which lives in organized packs, the coyote is a relatively pleasant animal. The male-female pair is the basic unit of this society, where one also meets many solitary animals and herds.

The couple is formed in the middle of winter, at the beginning of the mating season, and sometimes remain united for several years, sharing den and territory.

HIERARCHICAL FAMILY GROUPS In areas where the density of coyotes is relatively low, some animals live solitary. Usually, they are the ones who howl at nightfall from the top of the steep rocks.

In regions where coyotes are numerous and food abundant, small groups are formed, comprising 5 or 6 individuals, that is to say, the parents accompanied by the young of the previous year. These family groups are hierarchical, with the oldest animals dominating and leading the rest of the herd. This type of association also appears when small rodents become scarce. Only substantial cooperation then allows the coyotes to catch animals the size of an elk or a caribou, often faster than them.

Real clashes between coyotes are rare. Grunts and stern expressions are often enough for animals to give up the fight and submit. He must then leave the winner's territory or abandon him the carcass on which he is feasting.

Gambling is frequent. Fake fights, chases, and nibbling are expected in a family. This is part of the education of young people: parents teach them to communicate and to hunt.

THE CRY OF THE COYOTE The repertoire of coyotes is immense: barks like a dog, howl like a wolf, barks like a small puppy, growls ... They use combinations of all these sounds to call the members of their group signal their presence or immediate danger. They also seem to enjoy listening to each other bark or howl in the dark. This is how the solitary animals gathering for a hunting party at nightfall bring about a discordant concert famous throughout the American West and audible for miles around.

A VARIABLE AREA Each coyote, each couple or family group has its territory, centered on the lodge or den. The limits of this territory are marked by all the occupants, who mark it out very regularly by urinating. But few coyotes fight to deny the entry of their domain to a congener. The dominated animal is content to move away to seek asylum elsewhere. However, it seems that groups defend their territory more actively than pairs or solitary animals. Loud crashes, but not very violent, sometimes take place at the borders. The coyotes seem to recognize each other from a distance, up to 200 m. When two individuals meet, if they already know each other, they go their way.

The territory (from a few kilometers to over 50 km) depends on coyotes' density in the region, the season, and the abundance of prey. A study conducted in the Yukon Territory, in northwestern Canada, showed that the thickness of coyotes varies from 1 to 9 individuals per 100 km 2 in winter to 2.3 individuals per km 2 in summer. Instead of traveling at night - on average, a coyote crosses, during a night's hunt, 4 km - coyotes can make long journeys to find territory or for food.

BODY LANGUAGE

The whole body of the coyote is used to make itself understood. Rolling up the lips, lowering or raising the tail, flattening or raising the ears, making the hair stand up are all signals. The coat's black patches further reinforce the facial expressions: lips edged with white hairs around the ears' eyes and lips. A dominant coyote opens its eyes wide. An angry coyote flattens its ears. Aggression is indicated by the erect ears, the raised shoulders, the hair on the back bristling, the lips rolled up, the tail slightly raised. A submissive male shows his genitals to the opponent.

AT NINE MONTHS, THE YOUNG ARE ADULTS The mating season lasts from January to March but begins earlier in the North than in the South. More than 90% of females at least 20 months old go into heat. About 60% of 10-month-old females wait until the end of February if weather conditions are favorable. If the winter is too harsh, they will wait another year to mate.

Males are attracted early on by the smell of hormones in the urine of females in heat. Their courtship is assiduous for several weeks because before fertilization (pre-estrus) lasts from 2 to 3 months. Often, several males are interested in the same female and follow her without a fight. At the time of estrus, which lasts ten days, the female chooses her future partner and comes to give him a few blows of the muzzle. Like other canids, coyotes can stay mated for more than 25 minutes. The other males present do not try to intervene and leave to try their luck with a still available female.

A DEVOTED FATHER The couple demarcates a new territory, choose and clean an old badger, marmot, or fox burrow, or decide to dig a new den. During gestation, which lasts about two months (on average 63 days), both mates hunt together and sleep side by side. When the birth approaches, the male manages alone to ensure the daily pittance, and he brings food to his companion. This one arranges the burrow by depositing there leaves, grasses, or hairs torn from its belly. Some females give birth to their young on the bare ground.

A litter includes between 2 and 12 young (on average, 4). Both parents take care of them. Thus, the father helps with the toilet and feeding of the young after they have been weaned. He guards the entrance to the burrow. In case of danger, he transports the young people, one by one, to a safe refuge, sometimes several kilometers away.

For the first ten days, the little ones suck about every 2 hours. Their eyes open around the tenth day. The first teeth appear around the twelfth day. They walk around three weeks and then begin to come out of the den, watched by the parents, to explore their environment. They run before they are six weeks old. They are generally weaned at the age of 1 month but receive in relay regurgitated meat by both parents. They begin to prey on dead prey, mice, then rabbits.

Generally, young males emancipate themselves and leave their family group between 6 and 9 months. Young females tend to stay with their parents.

THE COYOTE'S DEN

When the coyote does not build an ancient badger or fox den to give birth to its litter, it digs one, very characteristic. The entrance, unique, 30 to 60 cm in diameter, is often hidden by bushes. About 3 m long and 40 to 50 cm wide, a tunnel connects it to a central room, or nursery, where the little ones will be installed. About 1.50 m in diameter, it is well ventilated, as the air enters it through a ventilation chim

TO KNOW EVERYTHING ABOUT THE COYOTE

LAROUSSE Search the encyclopedia ... Home > encyclopedia [wild-life] > coyote coyote Coyote Coyote Coyote CoyoteCoyoteCoyote cry Unlike the wolf, the North American coyote's numbers and its range are expanding, although they are trapped and poisoned by humans. It is one of the few wild animal species capable of surviving in urbanized regions. Its extraordinary ecological plasticity has enabled it to conquer two-thirds of the American continent.

INTRODUCTION The coyote, whose name comes from the Nahuatl (Aztec language) word coyote, belongs to the family of canines, including dogs, wolves, jackals, foxes, wild dogs.

Canids are believed to be native to North America's great plains where, 40 to 50 million years ago, in the Eocene, their common ancestor lived. Very quickly, the fox branch, Vulpes, broke away from this common trunk. A little later, in the Pliocene, the other components of canines are differentiated, notably, wolves and coyotes, which evolve separately despite their close kinship. At the end of this period, about 2.5 million years ago, Canis esophagus appears, the ancestor of the coyotes, which must have been a little larger than the present species' animals. According to more recent Pleistocene fossils found in the United States in Maryland and the Cita Cañon in Texas, his descendants closely resemble him. They then rub shoulders with the saber-toothed tiger on the American continent, which still roams the plains.

Since this distant time, coyotes have changed little in their morphology and have slightly differentiated from their ancestors. However, the comparative study of the skulls shows that their cranium has developed, but that the frontal bone is narrower in modern animals than it was in their ancestors. Their non-specialization over the ages has allowed coyotes to colonize new spaces and to adapt to all kinds of habitats and new situations. Thus, they are hunters, but they can survive by feeding on carrion, insects, or fruit. By ridding wild herds of weaker animals and eliminating already doomed individuals, they play their part in the natural balance.

Originally probably inhabiting the Great Plains, the southwestern United States, and Mexico, coyotes have greatly expanded their habitat, although uniquely American, today also includes deserts, mountains, and forests. And the outskirts of large cities. Thanks to man, who changed the environment and hunted wolves until their almost total extinction, their current territory is immense because they have taken over the vast areas formerly occupied.

THE LIFE OF THE COYOTE A SILENT AND INTELLIGENT HUNT The coyote is a solitary hunter that feeds on anything it can catch. In the central plains, where the climatic conditions are relatively stable, it has the same essential diet all year round, made up for more than 75% of hares. Rabbits, mice, pheasants are also among his favorite prey. Occasionally it does not disdain muskrats, raccoons, polecats, opossums, and beavers, as well as snakes and large insects.

In late summer and fall, the coyote will eat fruit that has fallen to the ground. Blackberries, blueberries, pears, apples, peanuts then represent 50% of his diet. He knows how to choose a fully ripe watermelon and cut it in half to taste its juicy pulp. Neither does he disdain the soybean meal or cottonseed meal distributed to cattle.

In more arid environments, such as Mexico, the coyote mainly hunts small rodents. It also attacks marmots and ground squirrels in Canada, ground squirrels that look like large guinea pigs. But these two species hibernate, and in winter, in these northern regions, it is forced, to survive, to become a scavenger.

In suburban or urban areas, the coyote feeds on human waste, products manufactured by him, such as dog food, or even his pets.

ALONE OR IN COOPERATION When it hears prey or spots it from afar thanks to its keen eyesight, the coyote approaches it silently, facing the wind, tail low, with slow steps interspersed with pauses. Arrived at 2 meters from his victim, he leaps on her and bites her neck. To finish her off, he keeps her in his mouth and shakes her violently. Death is quick. It usually devours the animal on the spot, even eating the bones of small prey.

When coyotes live together, they choose larger prey such as deer, elk, and other ungulates. They run around the herd. In a panic, an individual is isolated, then surrounded and attacked.

When the coyotes hunt in pairs, they force the isolated to run in a circle, taking turns to tire them out. This technique is used with caribou. The killed prey is disemboweled with claws and teeth and divided.

TWILIGHT AND MORNING HUNTERS

Twilight and morning hunters

Essentially nocturnal, the adults move around a lot, hunting more readily at dawn or dusk. On the other hand, young people between 4 months and a year old move more during the day and less at night. Their often unsuccessful hunting attempts force them to devote a lot of time to it, but they still have no territory or offspring to watch over.

SCAVENGER TO SURVIVE IN WINTER In Alaska and in several Canadian provinces, where they arrived following the gold miners in the mid-nineteenth th century, coyotes have learned to face the bitter cold of winter. In these regions, animals must live and feed when the temperature is -10 ° C. The thick fur of the Far North's coyotes covers their whole body and has the same insulating power as that of the gray wolf. The guard hairs reach 11 cm long compared to 5 cm in animals living in a warmer climate. Thick and tight, the undercoat can measure 5 cm in thickness.

But the coyote does not run well in thick snow. However, hares and rabbits do not come out of their burrows when the outside temperature is too low, and groundhogs hibernate. The coyote would not survive the winter if it did not fall back on dead animals. Feeding on all the carrion he finds, he shares them with his fellows.

However, if the wolves arrive, he must give way. He sometimes buries or hides to return to them later. Its best ally is the cold, which finishes off sick or weakened animals, often at the tail of herds of large herbivores. Thus, in winter, it therefore, moves after the latter, devouring dead ungulates. Watching for the slightest failure, he does not hesitate to give the "coup de grace" to elk or caribou, exhausted and unable to defend themselves. If the snow is not too thick and the carrion is insufficient, the coyotes will join forces to attack.

OFTEN SOLITARY, THE COYOTE PREFERS TO LIVE AS A COUPLE Halfway between the fox, solitary, and the wolf, which lives in organized packs, the coyote is a relatively pleasant animal. The male-female pair is the basic unit of this society, where one also meets many solitary animals and herds.

The couple is formed in the middle of winter, at the beginning of the mating season, and sometimes remain united for several years, sharing den and territory.

HIERARCHICAL FAMILY GROUPS In areas where the density of coyotes is relatively low, some animals live solitary. Usually, they are the ones who howl at nightfall from the top of the steep rocks.

In regions where coyotes are numerous and food abundant, small groups are formed, comprising 5 or 6 individuals, that is to say, the parents accompanied by the young of the previous year. These family groups are hierarchical, with the oldest animals dominating and leading the rest of the herd. This type of association also appears when small rodents become scarce. Only substantial cooperation then allows the coyotes to catch animals the size of an elk or a caribou, often faster than them.

Real clashes between coyotes are rare. Grunts and stern expressions are often enough for animals to give up the fight and submit. He must then leave the winner's territory or abandon him the carcass on which he is feasting.

Gambling is frequent. Fake fights, chases, and nibbling are expected in a family. This is part of the education of young people: parents teach them to communicate and to hunt.

THE CRY OF THE COYOTE The repertoire of coyotes is immense: barks like a dog, howl like a wolf, barks like a small puppy, growls ... They use combinations of all these sounds to call the members of their group signal their presence or immediate danger. They also seem to enjoy listening to each other bark or howl in the dark. This is how the solitary animals gathering for a hunting party at nightfall bring about a discordant concert famous throughout the American West and audible for miles around.

A VARIABLE AREA Each coyote, each couple or family group has its territory, centered on the lodge or den. The limits of this territory are marked by all the occupants, who mark it out very regularly by urinating. But few coyotes fight to deny the entry of their domain to a congener. The dominated animal is content to move away to seek asylum elsewhere. However, it seems that groups defend their territory more actively than pairs or solitary animals. Loud crashes, but not very violent, sometimes take place at the borders. The coyotes seem to recognize each other from a distance, up to 200 m. When two individuals meet, if they already know each other, they go their way.

The territory (from a few kilometers to over 50 km) depends on coyotes' density in the region, the season, and the abundance of prey. A study conducted in the Yukon Territory, in northwestern Canada, showed that the thickness of coyotes varies from 1 to 9 individuals per 100 km 2 in winter to 2.3 individuals per km 2 in summer. Instead of traveling at night - on average, a coyote crosses, during a night's hunt, 4 km - coyotes can make long journeys to find territory or for food.

BODY LANGUAGE

Body language

The whole body of the coyote is used to make itself understood. Rolling up the lips, lowering or raising the tail, flattening or raising the ears, making the hair stand up are all signals. The coat's black patches further reinforce the facial expressions: lips edged with white hairs around the ears' eyes and lips. A dominant coyote opens its eyes wide. An angry coyote flattens its ears. Aggression is indicated by the erect ears, the raised shoulders, the hair on the back bristling, the lips rolled up, the tail slightly raised. A submissive male shows his genitals to the opponent.

AT NINE MONTHS, THE YOUNG ARE ADULTS The mating season lasts from January to March but begins earlier in the North than in the South. More than 90% of females at least 20 months old go into heat. About 60% of 10-month-old females wait until the end of February if weather conditions are favorable. If the winter is too harsh, they will wait another year to mate.

Males are attracted early on by the smell of hormones in the urine of females in heat. Their courtship is assiduous for several weeks because before fertilization (pre-estrus) lasts from 2 to 3 months. Often, several males are interested in the same female and follow her without a fight. At the time of estrus, which lasts ten days, the female chooses her future partner and comes to give him a few blows of the muzzle. Like other canids, coyotes can stay mated for more than 25 minutes. The other males present do not try to intervene and leave to try their luck with a still available female.

A DEVOTED FATHER The couple demarcates a new territory, choose and clean an old badger, marmot, or fox burrow, or decide to dig a new den. During gestation, which lasts about two months (on average 63 days), both mates hunt together and sleep side by side. When the birth approaches, the male manages alone to ensure the daily pittance, and he brings food to his companion. This one arranges the burrow by depositing there leaves, grasses, or hairs torn from its belly. Some females give birth to their young on the bare ground.

A litter includes between 2 and 12 young (on average, 4). Both parents take care of them. Thus, the father helps with the toilet and feeding of the young after they have been weaned. He guards the entrance to the burrow. In case of danger, he transports the young people, one by one, to a safe refuge, sometimes several kilometers away.

For the first ten days, the little ones suck about every 2 hours. Their eyes open around the tenth day. The first teeth appear around the twelfth day. They walk around three weeks and then begin to come out of the den, watched by the parents, to explore their environment. They run before they are six weeks old. They are generally weaned at the age of 1 month but receive in relay regurgitated meat by both parents. They begin to prey on dead prey, mice, then rabbits.

Generally, young males emancipate themselves and leave their family group between 6 and 9 months. Young females tend to stay with their parents.

THE COYOTE'S DEN

The coyote's den

When the coyote does not build an ancient badger or fox den to give birth to its litter, it digs one, very characteristic. The entrance, unique, 30 to 60 cm in diameter, is often hidden by bushes. About 3 m long and 40 to 50 cm wide, a tunnel connects it to a central room, or nursery, where the little ones will be installed. About 1.50 m in diameter, it is well ventilated, as the air enters it through a ventilation chimney.

TO KNOW EVERYTHING ABOUT THE COYOTE COYOTE (CANIS LATRANS) The coyote is much smaller than the wolf. However, its size varies depending on the region, between 75 cm and 1 m (tail included), as well as its weight, between 7 and 21 kg. The female is always smaller than the male.

The coat is shorter in Mexican coyotes than in the Great Plains and the Far North prairies. It consists of a down (5 cm maximum) and guard hairs (11 cm top). The molt takes place once a year, in summer in the North, the new shorter hair gradually replacing the old one. The color of the back and sides ranges from gray to dull yellow. The back coat and tail hairs are fringed with black. The throat is white, while the chest and belly are instead a pale gray. The back of the ears are reddish, and the muzzle greyish. The coloring varies, with southern animals often being lighter in color than northern ones, sometimes almost entirely black.

The coyote's nose is smaller than that of the wolf, its skull is more massive, its footpads narrower, and its ears longer.

The coyote can leap 2 m and maintain a cruising speed of 40 to 50 km / h; on short trips, its peaks can reach 65 km / h. Coyotes can travel great distances. Some animals, equipped with a radio collar, were followed for more than 650 km.

An excellent swimmer, the coyote in pursuit of prey, does not hesitate to jump into the water. In addition to its usual game, mustelids, frogs, newts, snakes, fish, crayfish can appear on its menu. It is also one of the few predators to attack the beaver.

He is undoubtedly the canine with the most developed senses. Able to see 200 m in open terrain, it can see both day and night.

His vocal repertoire is varied, but his most characteristic calls are heard at nightfall, daybreak, or during the night. They consist of a series of yapping followed by a long howl.

Also Read: https://outsideneed.com/hunting-coyotes-at-night-tips/

0 notes

Text