#minotaur theory

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

tekkonkinkreet by taiyou matsumoto // minotauro by jordi garriga mora

taiyou matsumoto motifs: the monster / the labyrinth

#do you get it.#tekkonkinkreet#minotaur theory#gained a few followers (like 5) time to release posts from the drafts

197 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greek Mythology in Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes

How will Noa's story be remembered by future generations of apes?

Caesar is remembered by the apes as a sort of mythic, god-like figure. An ape whose story has been passed down for generations to the point where many apes are familiar with the legend of Caesar, even if the true story has been distorted throughout time.

The movies utilize famous myths, legends, and stories that we are all familiar with, or have at least heard of, to create the legend of Caesar, and now Noa.

In the Caesar trilogy, Caesar is a Moses figure for the apes, who we know freed his people, taking them to the promised lands. We should all at least recognize the name Hamlet, one of Shakespeare's plays, that Dawn is loosely based on. In some versions, the angel Lucifer rebelled against God because he refused to bow down to mankind. In Dawn, Koba rebelled against Caesar because he refused to help humans, or mankind. And we all know what happened to Lucifer after betraying God.

We know these stories. They're familiar, even now that they're hundreds or thousands of years old.

So what famous stories will the writers use so that Noa's story is remembered by apes centuries later?

Well, Kingdom had an ape named Noa, who saved his people from a flood, and there was even a giant boat in the background. Okay, Noah and the Flood. That one's obvious.

What about some Greek mythology?

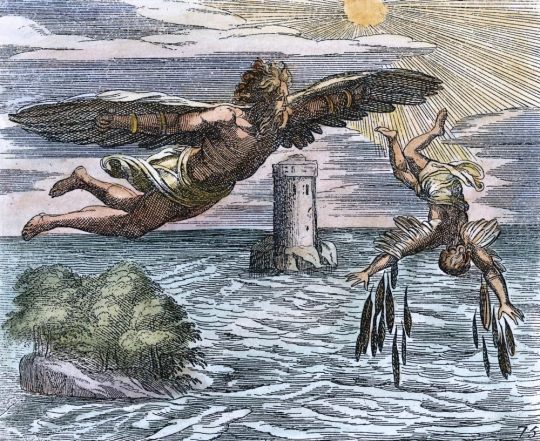

The Myth of Icarus and Daedalus

If you don't know how the myth of Icarus and Daedalus goes, there's still a very good chance you've heard of the saying, "He flew too close to the sun."

In a very brief nutshell, Daedalus, an inventor, built some wings for him and his son, Icarus. They put on these wings to fly away and escape King Minos, who is holding them prisoner. Daedalus warns his son not to fly too close to the sun because the wax will melt, but Icarus doesn't listen, and he falls to his death.

I found some similarities to the myth of Icarus and Daedalus in Kingdom. Whether this is what the writers actually intended or not, I don't know for sure, but this is mainly for fun, and I wanted to share!

Before I get started, I want to thank @iamtotallycool because she pointed out similarities to other Greek myths after I shared with her my initial thoughts, and I will later point out which ones she came up with. Thank you for listening to my ramblings on discord, lol.

Noa as Icarus

Noa reminds me of Icarus, the man who flew too high and fell to his death. Noa is the first to climb above Top Nest, so this means he went higher than any of the other apes in his clan. He is soaring above the others, reaching new and dangerous heights.

Noa decides to go higher, wonderfully displaying his ingenuity by using some old rebar to swing himself up a wall that should've been impossible to climb. This reminds me of Daedalus using his inventions to help him fly, something considered impossible.

But after Noa reaches the nest, higher than any ape before him, what happens right after? He falls.

In a deleted scene after the egg climb, Soona tells Noa that since he is the first above Top Nest, that makes him special, and maybe his eagle will be sun-colored, like his father's eagle, Sun.

And right after Noa literally falls into Raka's home, the wise orangutan says to himself in amusement:

"Apes falling from the sky."

Here's a fun detail. Remember that mural Noa looks at? On the far left side, if you squint, you can see a person with wings.

I actually have a theory as to how Noa could fly in future movies that I'll link at the end!

Noa as Daedalus

Not only does Noa remind me of Icarus, but he also reminds me of Daedalus. Daedalus was a skillful architect and inventor, who built the Labyrinth for King Minos, where the legendary Minotaur lived.

We see the beginnings of Noa's architect side. He stays up late at night to fix both the fish rack and the electric staff. When Proximus (King Minos) learns of how Noa (Daedalus) fixed the staff, he tells Noa that he has use for clever apes like him, as if he wanted to use Noa's intelligence to help him achieve instant eeevolution. This reminds me of how King Minos uses Daedalus' intelligence to build him the Labyrinth.

And just like Daedalus who built the wings to escape King Minos, Noa devises a plan to flood the vault for him and Eagle Clan to escape Proximus.

Trevathan is also like Daedalus in this story, who is trapped by the king, building and creating for him. Daedalus built the Labyrinth for King Minos, and Trevathan built the electric staffs for Proximus.

Fathers and Sons

Daedalus warns his son to be careful. To not fly too low, for the water will get his wings wet, and to not fly too high, for the sun will melt the wax from his wings. But Icarus doesn't listen, rushing to surpass the father.

This reminds me of how Noa feels a lot of pressure from his father Koro, wanting to make his father proud by telling him that he was the only one of his friends who climbed above Top Nest. Instead of praise, however, Koro reprimands him for breaking some other rule, telling him to stay away from where he is forbidden to go.

Theseus and the Labyrinth

@iamtotallycool pointed out how Kingdom also has similarities to the myth of Theseus, the Labyrinth, and the Minotaur.

The Labyrinth is an underground maze on the island of Crete where the monstrous Minotaur lives. Every year, King Minos requires sacrifices from other kingdoms for the Minotaur to eat. Theseus, son of King Aegeus, sets out to kill the Minotaur. Princess Ariadne, King Minos' daughter, helps Theseus to navigate the Labyrinth, and gives him a ball of yarn to help him make his way back so he doesn't get lost.

This reminds me of how Proximus (King Minos) steals clans (the sacrifices) for the expansion of his kingdom and to get the vault open, so Noa (Theseus) uses the help of Mae (Ariadne) to navigate the vault (Labyrinth) in order to destroy what is inside (Minotaur).

During the scene where Noa and Sylva have their final battle, Noa has to run through the twists and turns of the vault, similar to a maze, while he is being chased by Sylva, similar to how the Minotaur battled Theseus. Sylva is even big and burly like the Minotaur!

Ok, So What Does This Mean?

Alright, so now that we pointed out some of the similarities, what could this all mean? It's one thing to point out the similarities, but why these stories in particular? What is the message? What could this mean for Noa? Assuming this is even what the writers intended, we can only speculate, so this final bit is mainly fun theorizing.

Due to his hubris, Icarus flies too close to the sun, leading to his death. Could Noa develop his own hubris that leads him to his downfall, or takes him down a darker path?

The myth of Icarus can also be seen as a cautionary tale of the dangers of technology if not used carefully. Technology can be useful and improve lives, but what if it falls into the wrong hands? What if one is too overconfident with it, not realizing the bad it can do before it's too late?

Proximus couldn't get his hands on human technology, for he would've used it to hurt other apes. What about Noa, though? Now that Noa starts to learn how human tech like electricity works, what if he starts to bring forth technological innovations for the apes? What if he starts out trying to use it to improve the lives of apes, but he ends up using it for bad? Or what if other apes take his ideas and use it for their own advantage? The path to hell is paved with good intentions, as they say.

And this one's more for fun, but what if Noa were to actually fly? If you wanna read more of my ramblings, here is my theory on Noa taking flight. (Hint: It involves airplanes).

In Conclusion

If you made it all the way to the end, thank you for reading! I had a lot of fun coming up with these ideas and speculating, and I hope you had fun reading this as well. If you have any thoughts or ideas, feel free to share!

#planet of the apes#kingdom of the planet of the apes#pota#kotpota#noa pota#mythology#greek mythology#icarus#daedalus#my theory#analysis#theseus#the minotaur#nomae

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Diane Ehrensaft: There was a child, sitting there, wearing essentially basketball uniform, head to toe. Not a Warriors, but a basketball uniform. Came into my office and I greeted them, then they twirled around and had a long, blonde braid with a pink bow at the bottom, and then twirled around again and said to me, "you see, I'm a Prius." I said, "uh huh." She- they said, "yes, I'm boy in the front, and I'm a girl in the back. So, I'm a hybrid." I went, okay, we got gender hybrids. Then I started meeting a whole bunch of gender hybrids. And so, we have the gender prius, we have the gender minotaur, now, I use that term, nobody came in to me and said "I'm a gender minotaur." But what they did come in to me and say is, "I'm one thing on the top, and another thing on the bottom." And often that was to explain away their genitalia. And most of the kids who were gender minotaurs love mermaids. And we actually have a lot of mermaid books. Cause if you think about it, it works.

If you ever feel stupid, remember that this woman has tenure and is allowed to prescribe drugs.

Notice too how completely dependent upon stereotypes this whole thing is. Baseball uniform = boy, pink braid = girl. You can't be a girl with long hair who likes sports, or a boy who plays baseball and likes braids and ribbons. They use big words and high academic notions to obfuscate that their ideas are really just that ridiculous and superficial.

This woman is dangerous, and her license needs to be revoked.

#Diane Ehrensaft#gender ideology#queer theory#gender minotaur#gender prius#medical malpractice#unethical#insane people#religion is a mental illness

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Prediction: One of Melione’s domains is ghosts. I think her cast will be shades she sends out to attack enemies. The shade NPCs from last game can come with you to help. In the trailer, the scene of the hub world with Nemesis has Patroclus in the top right corner standing at a table. You would talk to them to add them to your party. Dora will be the first shade cast you get, but after you convince her to join you.

Anyways, here's a doodle of the Hades 1 NPC shades as, well, shades.

#Hades#hades 2#hades game#eurydice#Orpheus#achilles#Patroclus#asterius#Theseus#sisyphus#bouldy#minotaur#my art#fanart#patrochilles#achilles x patroclus#orpheus x eurydice#orphydice#hades 2 theories#no idea if that's the actual ship name

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Steinbeck, East of Eden

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alright, we're sharing crack House of Leaves theories tonight. Warnings for spoilers, discussion of trauma, incomprehensible rambles, and mental gymnastics the likes of which you've never seen.

So we all know that Navidson is a photojournalist. It's made blatantly obvious in literally everything he does. He was planning on just filming his domestic life when he began making the Navidson Record. His most influential moment came from Delial, whose story is a direct copy of that one really famous photo that actually exists, for fuck's sake. He's a walking stereotype of the photojournalism industry as a whole.

We've all also seemed to collectively agree that House of Leaves is, at least partially, about trauma (specifically SA). We see it with Karen, Pelafina, Johnny, and a lot of side-characters. We've even gone as far as to theorize that Pelafina (and by extension Karen) could be considered an author.

So onto the theory: Navidson is actually literally a walking collage of experiences and moments and facts and commentary on the photojournalism industry and by extension the mindset of those in the industry. He's a metaphor for it all. He's not real.

Furthermore, Karen is the creator (or at least the main editor) of The Navidson Record. Navidson is completely and entirely a figment of Karen's imagination, and his purpose as the photojournalism industry is to explore the idea of creating more palatable false truths in trying to comprehend the incomprehensible or uncomfortable real truths (which is very prevalent in journalism). There's also themes of greed and selfishness, as well as objectification and monetization of human suffering innate in a walking photojournalism metaphor. But that is made more complex with Navidson's regret and shame with Delial.

I think the idea of photojournalism is another metaphor in itself for trauma. It could be one (or both) of two things. It could be about a trauma response via trying to find answers for why you were singled out to face that trauma or why your abuser chose to abuse you or whether you deserved it or not. It also relates to false memories and dissociation. You create false truths to protect yourself from the more traumatizing real truths. You force yourself to forget your trauma and bury your pain, and then the resulting symptoms are explained away as innocuous and innocent.

Or it could be about your abuser and the trauma itself. It could be about the selfishness of rapists and predators and abusers and how to them you're nothing more than an object; a means to an end. They are the photojournalist and you are the scene that will bring them fame and money. They are Navidson and you are Delial.

It could be a complex mess of both too. There are aspects that fit with either interpretation. It could be a metaphor for trauma as a whole, because trauma is messy and complicated and hard to understand.

Either way, it goes back to the incomprehensible nature of the house. The house itself is the trauma and the way your brain has cataloged it in your mind. It can be a vast labyrinth of false memories and blank spaces and random symptoms you can't find the cause of and strange hints and vibes of just something. Trauma is the Minotaur; the shadowed fingers of the hallway, and your mind is the labyrinth.

You might never find the trauma. It may be forever buried in a labyrinth with no center and no end; forever moving and stalking you and leaving little more than a ghost of its presence for you to turn about over and over, trying to find the flesh of the truth that is so hopelessly out of your reach. And maybe it's a good thing you never come across it. The Minotaur would not hesitate to gore you with its horns and leave you to die in the darkness of the maze. The unobscured truth of your trauma will very much break you beyond repair.

So, in short, Navidson is a metaphor for the photojournalism industry, which is a metaphor for trauma. The house is the maze of the Minotaur, which is the brain's filing away of trauma, which is the Minotaur.

So, would this mean Navidson is the Minotaur? Or is the Minotaur simply the memory of trauma with Navidson being the trauma itself? Does that still make them innately connected?

#house of leaves#hol#mark z danielewski#the navidson record#will Navidson#the minotaur#house of leaves theory#zampano#long post

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

i don’t think the seven were made aware of all the shit percy went through before the events of HoO. at least i don’t recall it happening

like sure, leo, piper and jason might have heard about it from the other campers, but let’s be honest, at that moment the main worry was to find him. they knew him as annabeth’s missing boyfriend

frank and hazel saw him being a badass right away, but an amnesic badass who couldn’t share the tales of his past victories. they might have even thought he went through a training similar to jason’s

but now i wanna know how they’d react to it

#how would they react when they’re told that percy killed the minotaur at 12 without any weapons or training??#i need to know#they don’t know he held the sky the streak had already disappeared by then#they dont know shit about percy#rick didn’t see a reason to go back on it in HoO since we the readera already knew#that kind of leaves the characters in the dark tho#percy jackson and the olympians#percy jackson theories#percy jackson#pjo#heroes of olympus

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading Ch13 of House of Leaves and I’m just dumping some random thoughts here about Redwood lol.

Redwood is only mentioned on three pages (only capitalized in the latter two). “Myth is Redwood” shows up on page 337 in chapter 13. The only other mention is in Appendix B (Zampano’s diary entries), with Zampano saying that he “saw him once a long time when I was young… But now I cannot run and anyway this time I am certain he would follow.” So Redwood is a person or some other entity. It’s directly contrasted with ‘Holloway’s Beast’ and The Minotaur… interesting.

#there is a focus on parent-child relationships and it’s even connected to the minotaur itself (footnote 123)#how it relates to zampano in particular… makes me wonder if he has a kid#anyway most of my thoughts are just pointing out stuff I’m not confident enough to come up with theories/analyze the themes lol#haven’t even finished the book and I’m already planning on a re-read#❀.txt#📖

1 note

·

View note

Text

Me because the Percy Jackson series is actually about the different cycles of abuse, which include abuse within romantic partners (Sally and Gabe), abuse between “family” (Percy and Gabe, Meg and Nero), abuse from people in positions of power (the gods over the demigods), and so on, oppression than ranges from having adhd in the public educational system to being forced to perform quests for your entire life for people who could not care less about your well-being, how camp is both somewhere safe but also the bittersweet taste of arriving there and realizing you can never escape, you can never be normal your life will never be the same. There’s no turning back. How Luke was right on theory but not on acts, how these kids got around the idea to never make it to 18, and how there was nothing they could do about that. How many of them sat in their cabins, counting down the days until their sibling/friend/partner came back, only for them to not come back at all. Was it ever their turn to leave someone waiting behind? Annabeth, Percy, Grover, Thalia, the whole deal with Nico, Bianca, Silena, and every single demigod. Children of Apollo were the camp healers, was it a choice? A moral obligation? In camp Jupiter there’s Jason, there’s Reyna, Piper’s story, Leo’s story, Leo lived on the street, the way Jason and Piper’s relationship was heteronormativity pushed by Hera because both of them were queer but she wanted a perfect couple. After being gone missing, people searched for Percy, but Jason? The devastation of Leo and Jason’s relationship, how Leo never knew his feelings for him were required, how both Leo and Piper thought they knew Jason but it was all fake memories, how Jason never fully got his memories back. Hazel’s story, Frank’s story, how Nico and Leo’s mutual dislike for each other comes from a place of understatement. How they both see themselves in each other and look away as one looks away from a mirror when they dislike their reflection. They are both so similar, almost the same. They both are also autistic, except Leo is always masking, and Nico never really learnt how to. Neurodivergence, adhd and dyslexia. Being a demigod is a metaphor for neurodiversity. Was Dionysus actual punishment looking over camp? Or was it spending years and years seeing demigods come and grow and die? Knowing there was nothing he could do about it? Knowing than if he was with the gods, he would be causing their deaths, instead of grieving them? Does Chiron feel hopeless? Memory, names, ghosts. Blades, swords, arrows, blood. So many blood, blood-stained hands. Monsters follow you before coming to camp, did they hurt you family? It was all your fault. They don’t want you to come back, you bring danger, you’re more dangerous than the monster, you are a monster yourself, after all the Minotaur was a demigod too. Leo killed his mother, Zeus killed Maria, Sally got taken to the underworld, Tristan was held hostage, Fredrick and his wife and sons got attacked by monsters, and who’s fault it was? You run away you keep on running but you’ll never outrun the danger because the danger is yourself, you are at fault, how do you run away now?

The odyssey, the iliad, the statues in museums, you look at them, do you see yourself? Do you see any resemble? Your nose kinda looks like theirs, the shape of their lips, the width of their hands, but that’s a lie you’re nothing like them, never will be, is that a tragedy? Do you want to be like them? Do you want to be a hero and die a heroic death? Or do you simply wish to visit your family on Christmas and live the life your little cousins will eventually live? Maybe you’ll never see the life they’ll live, maybe you’ll die before seeing it. There’s nothing to be done about that, you just have to accept it. Don’t you feel the rage, bubbling inside of you, making your hands shake? What can you do with it? Not much, remember last time, remember Luke, what did he accomplish? Nothing, blood, screams. You remember the war, you remember the city, maybe it was the first or the second time you set a foot on it, now every single time you do (if you do) in the future, it will be tainted. Look in that corner, that used to be destroyed. Look at that building, my friend died against that wall, that road was filled with blood. Was it ours? Theirs? Is there even a difference between us? Should there be? Why were you on your side? Why were they in theirs? Who was right? Who was wrong? You can go anywhere but home, maybe you’re not welcomed, maybe there’s no home to return, maybe it’s better for everyone if you don’t return. Nico keeps Bianca’s jacket, Leo taps iloveyou on Morse code. Piper was forced to be someone she wasn’t, she thought she was someone she was not, she was forced to think that. Who is she? Is she even who she thought she was? Jason still don’t remembers everything, and him? Who is he? Nico will never get his memories back, he wonders about his mom, did he have more family back then? Grandparents, aunts? Hazel is a walking curse. Silena and Clarisse as Patroklos and Achilles. Apollo seeing the brutal reality of demigods’ life on trials of apollo.

Your hand shakes, the sword you hold moves, you feel it’s weight, do you want to hold it? Do you have to?

The dead come back to haunt us, Nico sees Bianca everywhere, Leo still remembers his mother’s voice, Hazel came back from the dead, Frank holds his life on his pocket, Thalia lost a brother twice, Leo didn’t really die, Jason died instead, Percy wished to drown himself, half of camp still waits for their brother to come back, even if it has been months, even if it has been years. Luke’s mother still waits, was she crazy? The campers who thought to recognize their friend’s face for a second before remembering than it couldn’t possibly be them, were they crazy too? Who was crazier? Luke’s mother who did not remember, or the campers who did? The underworld has no mercy only justice, but the world has no justice only mercy. You might get mercy, but you never will get justice. Was it fair anything than happened to them? You might be spared in a war or in a battle out of mercy, out of pity, out of recognition, but that didn’t stop you from having to fight in it, that didn’t stop you from having to wield the sword. Spare all the people you want, turn a blind eye to whatever you want, mercy? sure, but you were still holding the sword, you were still supposed to fight, you still weren’t in charge of your life. How was that justice? How was that fair? Names had power, even their names had more power than your life, even the letters making up their names were more powerful than your fists, could you ever win? Could you ever win when their names were so powerful they could not be pronounced but your life was so worthless they didn’t even care to learn yours? To learn the names of the ones than died because of them. You can’t say the name of you sister’s killer, but you’re still expected to burn an offering to them each night at dinner.

#ahahah this is my super cool and canon version of Percy Jackson than exits on my head ok#can you tell i hate the pjo gods like#a LOT#*exists#pjo#luke castellan#rick riordan#toa#hoo

959 notes

·

View notes

Note

You discussed humanfuckers in the monster au recently and listed several characters who would be among the humanfucker ranks but I was surprised not to see Rook and Rollo on that list. I would have thought they'd be on that list as I can totally see them reading human erotica and 'appreciating' pornographic art of humans , maybe not on Trottr but perhaps published romance/erotica novels and classical style art pieces, perhaps even antique ones from when humans were still around. Also if Malleus is an honorary humanfucker for his interest in THE (his) human rather than just humans overall, wouldn't that mean most of the cast could be considered honorary humanfuckers too, if not right now then soon?

First part here:

Warnings; yandere, yandere behavior, mention of adult content, by selecting 'view more' you consent to view content and are of age to view content.

~~~~~~~~

Because Rollo and Rook are on their way into it quickly due to sparked interest, but they weren't obsessed over Humans before meeting The Human. Those listed prior were obsessed long before meeting a Human in the flesh.

Rollo, up until he actually meets The Last Human, sees it as demeaning the species as a whole to write such hedonistic trash. He wishes to emulate the Righteous Judge in any way he can and the Judge cherished Humans above everything, even his own life. Rollo sees it like someone is depicting his deities- who he devotes his life to work in the name of- as common whores. He could tell you everything on the written history of Humans and the Humans of Fleur City because he has devoted his own time to learning about Humans. He respects and honors the legacy of Humans in Twisted Wonderland.

His attitude switch towards suggestice works involving Humans is as abrupt and jarring as a flash of lightning when he finally meets the Human of Night Raven and suddenly he sees the appeal. He thought the depictions of Humans were beautiful whenever he saw them, but his more carnal interests only really hit him when he met one. Now he gets it. He will never admit to such vile thoughts, but he has far more than he would like.

Rollo is going to be in future chapters, don't worry.

~•§•~

Rook is awakening into that role and idea. He really only saw Humans from a history standpoint, an end note to file away under mythical tales and long gone creatures. Sure, Human things exist all around him, but he likes to observe beauty in the moment. Why weep over what is long lost when there are beauties to observe here and now?

The Human of Night Raven is certainly now a beauty he can behold and marvel at. He is understanding the appeal and he is becoming more interested in learning all he can about these Humans. He is frustrated there is so little agreed upon when it comes to Humans. Human remains are so contested they can't even classify Humans in any official species. The popular theory is they are closest to pigs, hence the belief Humans shouldn't eat pork often. He thinks that's stupid, where are the pig ears and tails? The Boar variants of Minotaurs were very well known.

He is just falling down the rabbit hole, don't you worry. We will get to Rook's interest soon enough.

~•§•~

Malleus is honorary compared to the others for a few reasons, first; he won't turn up his nose to such works- published works, he still is not fond of technology- but when he reads them, it is his Human he thinks of. Not all Humans or the idea of Humans. That one Human in particular that is part of his Hoard and belongs to him, that one right there. He mentally overwrites all details of the Human love interest in the piece with the details of his Human and replaces himself as the monster suitor. He often imagines his Human as a Dragon as well and the romance the two of you could share as Dragons.

Second; Humans and the truth of them are still as illusory to Malleus as the surface of the moon would be to a cow. According to Lilia, they all looked different and had varying skin tones and hair styles, even eye colors, some even had completely different instincts from others. His entire view of Humans as a whole is based on the idea that no Human is the same or even comparable.

#kiame-sama#yandere#x reader#yandere x reader#reader insert#tw yandere#humans are extinct twst au#yandere malleus draconia#yandere malleus x reader#yandere rollo flamme#yandere rollo x reader#yandere rook hunt#yandere rook x reader

165 notes

·

View notes

Note

Possibly stupid question, but what do you think the turtles favorite pizza are?

Not sure, but I can take a guess. I believe Mikey's fav is....whatever this pizza is from the "Minotaur Maze" episode:

He was staaarving, and upon attempting to take the first bite he says "Sweet Salvation," which could be just because he's hungry. Buuuuut, I would think that, as hungry as he was, wouldn't he order his favorite pizza?

The toppings? Maybe pepperoni with the green bits being green peppers?

As for the others...

Someone likes Meat lovers, and Donnie likes "definitely not Hawaiian." 😂

You would think the Meat lovers is for Leo, but I have a theory that it's actually for Raph because this is the pizza Leo decides to make for himself.

Pepperoni + Other Meats + Mushrooms and...

judging based on those little hollow circles, maybe it's those Olives. (Oh and don't forget the Parmesan cheese!) 😂

Lastly, I couldn't even try to pin down what Donnie's favorite is. Honestly, I feel like it's whatever he's in the mood for on any given day. Even if it's this:

Thanks for the ask! 💜

#answered asks#rottmnt#tmnt#teenage mutant ninja turtles#rise of the teenage mutant ninja turtles#rise of the tmnt#tmnt2018#tmnt 2k18#tmnt 2018#save rottmnt#unpause rottmnt#unpause rise of the tmnt#save rise of the tmnt#save rise of the teenage mutant ninja turtles

285 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been seeing a bunch of theories of the golden ribbon/string around Hydes wrist be a reference the yarn of ariadne and it's gonna be Hyde going into the labyrinth of his and Jekylls mind right but guys this is all a reference to both tragedies of labyrinth

Theseus and the minotaur and the fall of Icarus guys guys please see the vision, Jekyll being both Icarus and the minotaur I need someone to understand this please

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

A TENTH ANNIVERSARY INTERVIEW WITH SUZANNE COLLINS

On the occasion of the tenth anniversary of the publication of The Hunger Games, author Suzanne Collins and publisher David Levithan discussed the evolution of the story, the editorial process, and the first ten years of the life of the trilogy, encompassing both books and films. The following is their written conversation.

NOTE: The following interview contains a discussion of all three books in The Hunger Games Trilogy, so if you have yet to read Catching Fire and Mockingjay, you may want to read them before reading the full interview.

transcript below

DAVID LEVITHAN: Let’s start at the origin moment for The Hunger Games. You were flipping channels one night . . .

SUZANNE COLLINS: Yes, I was flipping through the channels one night between reality television programs and actual footage of the Iraq War, when the idea came to me. At the time, I was completing the fifth book in The Underland Chronicles and my brain was shifting to whatever the next project would be. I had been grappling with another story that just couldn’t get any air under its wings. I knew I wanted to continue to explore writing about just war theory for young audiences. In The Underland Chronicles, I’d examined the idea of an unjust war developing into a just war because of greed, xenophobia, and long-standing hatreds. For the next series, I wanted a completely new world and a different angle into the just war debate.

DL: Can you tell me what you mean by the “just war theory” and how that applies to the setup of the trilogy?

SC: Just war theory has evolved over thousands of years in an attempt to define what circumstances give you the moral right to wage war and what is acceptable behavior within that war and its aftermath. The why and the how. It helps differentiate between what’s considered a necessary and an unnecessary war. In The Hunger Games Trilogy, the districts rebel against their own government because of its corruption. The citizens of the districts have no basic human rights, are treated as slave labor, and are subjected to the Hunger Games annually. I believe the majority of today’s audience would define that as grounds for revolution. They have just cause but the nature of the conflict raises a lot of questions. Do the districts have the authority to wage war? What is their chance of success? How does the reemergence of District 13 alter the situation? When we enter the story, Panem is a powder keg and Katniss the spark.

DL: As with most novelists I know, once you have that origin moment — usually a connection of two elements (in this case, war and entertainment) — the number of connections quickly increases, as different elements of the story take their place. I know another connection you made early on was with mythology, particularly the myth of Theseus. How did that piece come to fit?

SC: I was such a huge Greek mythology geek as a kid, it’s impossible for it not to come into play in my storytelling. As a young prince of Athens, he participated in a lottery that required seven girls and seven boys to be taken to Crete and thrown into a labyrinth to be destroyed by the Minotaur. In one version of the myth, this excessively cruel punishment resulted from the Athenians opposing Crete in a war. Sometimes the labyrinth’s a maze; sometimes it’s an arena. In my teens I read Mary Renault’s The King Must Die, in which the tributes end up in the Bull Court. They’re trained to perform with a wild bull for an audience composed of the elite of Crete who bet on the entertainment. Theseus and his team dance and handspring over the bull in what’s called bull-leaping. You can see depictions of this in ancient sculpture and vase paintings. The show ended when they’d either exhausted the bull or one of the team had been killed. After I read that book, I could never go back to thinking of the labyrinth as simply a maze, except perhaps ethically. It will always be an arena to me.

DL: But in this case, you dispensed with the Minotaur, no? Instead, the arena harkens more to gladiator vs. gladiator than to gladiator vs. bull. What influenced this construction?

SC: A fascination with the gladiator movies of my childhood, particularly Spartacus. Whenever it ran, I’d be glued to the set. My dad would get outPlutarch’s Lives and read me passages from “Life of Crassus,” since Spartacus, being a slave, didn’t rate his own book. It’s about a person who’s forced to become a gladiator, breaks out of the gladiator school/arena to lead a rebellion, and becomes the face of a war. That’s the dramatic arc of both the real-life Third Servile War and the fictional Hunger Games Trilogy.

DL: Can you talk about how war stories influenced you as a young reader, and then later as a writer? How did this knowledge of war stories affect your approach to writing The Hunger Games?

SC: Now you can find many wonderful books written for young audiences that deal with war. That wasn’t the case when I was growing up. It was one of the reasons Greek mythology appealed to me: the characters battled, there was the Trojan War. My family had been heavily impacted by war the year my father, who was career Air Force, went to Vietnam, but except for my myths, I rarely encountered it in books. I liked Johnny Tremain but it ends as the Revolutionary War kicks off. The one really memorable book I had about war was Boris by Jaap ter Haar, which deals with the Siege of Leningrad in World War II.

My war stories came from my dad, a historian and a doctor of political science. The four years before he left for Vietnam, the Army borrowed him from the Air Force to teach at West Point. His final assignment would be at Air Command and Staff College. As his kids, we were never too young to learn, whether he was teaching us history or taking us on vacation to a battlefield or posing a philosophical dilemma. He approached history as a story, and fortunately he was a very engaging storyteller. As a result, in my own writing, war felt like a completely natural topic for children.

DL: Another key piece of The Hunger Games is the voice and perspective that Katniss brings to it. I know some novelists start with a character and then find a story through that character, but with The Hunger Games (and correct me if I’m wrong) I believe you had the idea for the story first, and then Katniss stepped into it. Where did she come from? I’d love for you to talk about the origin of her name, and also the origin of her very distinctive voice.

SC: Katniss appeared almost immediately after I had the idea, standing by the bed with that bow and arrow. I’d spent a lot of time during The Underland Chronicles weighing the attributes of different weapons. I used archers very sparingly because they required light and the Underland has little natural illumination. But a bow and arrow can be handmade, shot from a distance, and weaponized when the story transitions into warfare. She was a born archer.

Her name came later, while I was researching survival training and specifically edible plants. In one of my books, I found the arrowhead plant, and the more I read about it, the more it seemed to reflect her. Its Latin name has the same roots as Sagittarius, the archer. The edible tuber roots she could gather, the arrowhead-shaped leaves were her defense, and the little white blossoms kept it in the tradition of flower names, like Rue and Primrose. I looked at the list of alternative names for it. Swamp Potato. Duck Potato. Katniss easily won the day.

As to her voice, I hadn’t intended to write in first person. I thought the book would be in the third person like The Underland Chronicles. Then I sat down to work and the first page poured out in first person, like she was saying, “Step aside, this is my story to tell.” So I let her.

DL: I am now trying to summon an alternate universe where the Mockingjay is named Swamp Potato Everdeen. Seems like a PR challenge. But let’s stay for a second on the voice — because it’s not a straightforward, generic American voice. There’s a regionalism to it, isn’t there? Was that present from the start?

SC: It was. There’s a slight District 12 regionalism to it, and some of the other tributes use phrases unique to their regions as well. The way they speak, particularly the way in which they refuse to speak like citizens of the Capitol, is important to them. No one in District 12 wants to sound like Effie Trinket unless they’re mocking her. So they hold on to their regionalisms as a quiet form of rebellion. The closest thing they have to freedom of speech is their manner of speaking.

DL: I’m curious about Katniss’s family structure. Was it always as we see it, or did you ever consider giving her parents greater roles? How much do you think the Everdeen family’s story sets the stage for Katniss’s story within the trilogy?

SC: Her parents have their own histories in District 12 but I only included what’s pertinent to Katniss’s tale. Her father’s hunting skills, musicality, and death in the mines. Her mother’s healing talent and vulnerabilities. Her deep love for Prim. Those are the elements that seemed essential to me.

DL: This completely fascinates me because I, as an author, rarely know more (consciously) about the characters than what’s in the story. But this sounds like you know much more about the Everdeen parents than found their way to the page. What are some of the more interesting things about them that a reader wouldn’t necessarily know?

SC: Your way sounds a lot more efficient. I have a world of information about the characters that didn’t make it into the book. With some stories, revealing that could be illuminating, but in the case of The Hunger Games, I think it would only be a distraction unless it was part of a new tale within the world of Panem.

DL: I have to ask — did you know from the start how Prim’s story was going to end? (I can’t imagine writing the reaping scene while knowing — but at the same time I can’t imagine writing it without knowing.)

SC: You almost have to know it and not know it at the same time to write it convincingly, because the dramatic question, Can Katniss save Prim?, is introduced in the first chapter of the first book, and not answered until almost the end of the trilogy. At first there’s the relief that, yes, she can volunteer for Prim. Then Rue, who reminds her of Prim, joins her in the arena and she can’t save her. That tragedy refreshes the question. For most of the second book, Prim’s largely out of harm’s way, although there’s always the threat that the Capitol might hurt her to hurt Katniss. The jabberjays are a reminder of that. Once she’s in District 13 and the war has shifted to the Capitol, Katniss begins to hope Prim’s not only safe but has a bright future as a doctor. But it’s an illusion. The danger that made Prim vulnerable in the beginning, the threat of the arena, still exists. In the first book, it’s a venue for the Games; in the second, the platform for the revolution; in the third, it’s the battleground of Panem, coming to a head in the Capitol. The arena transforms but it’s never eradicated; in fact it’s expanded to include everyone in the country. Can Katniss save Prim? No. Because no one is safe while the arena exists.

DL: If Katniss was the first character to make herself known within story, when did Peeta and Gale come into the equation? Did you know from the beginning how their stories would play out vis-à-vis Katniss’s?

SC: Peeta and Gale appeared quickly, less as two points on a love triangle, more as two perspectives in the just war debate. Gale, because of his experiences and temperament, tends toward violent remedies. Peeta’s natural inclination is toward diplomacy. Katniss isn’t just deciding on a partner; she’s figuring out her worldview.

DL: And did you always know which worldview would win? It’s interesting to see it presented in such a clear-cut way, because when I think of Katniss, I certainly think of force over diplomacy.

SC: And yet Katniss isn’t someone eager to engage in violence and she takes no pleasure in it. Her circumstances repeatedly push her into making choices that include the use of force. But if you look carefully at what happens in the arena, her compassionate choices determine her survival. Taking on Rue as an ally results in Thresh sparing her life. Seeking out Peeta and caring for him when she discovers how badly wounded he is ultimately leads to her winning the Games. She uses force only in self-defense or defense of a third party, and I’m including Cato’s mercy killing in that. As the trilogy progresses, it becomes increasingly difficult to avoid the use of force because the overall violence is escalating with the war. The how and the why become harder to answer.

Yes, I knew which worldview would win, but in the interest of examining just war theory you need to make the arguments as strongly as possible on both sides. While Katniss ultimately chooses Peeta, remember that in order to end the Hunger Games her last act is to assassinate an unarmed woman. Conversely, in The Underland Chronicles, Gregor’s last act is to break his sword to interrupt the cycle of violence. The point of both stories is to take the reader through the journey, have them confront the issues with the protagonist, and then hopefully inspire them to think about it and discuss it. What would they do in Katniss’s or Gregor’s situation? How would they define a just or unjust war and what behavior is acceptable within warfare? What are the human costs of life, limb, and sanity? How does developing technology impact the debate? The hope is that better discussions might lead to more nonviolent forms of conflict resolution, so we evolve out of choosing war as an option.

DL: Where does Haymitch fit into this examination of war? What worldview does he bring?

SC: Haymitch was badly damaged in his own war, the second Quarter Quell, in which he witnessed and participated in terrible things in order to survive and then saw his loved ones killed for his strategy. He self-medicates with white liquor to combat severe PTSD. His chances of recovery are compromised because he’s forced to mentor the tributes every year. He’s a version of what Katniss might become, if the Hunger Games continues. Peeta comments on how similar they are, and it’s true. They both really struggle with their worldview. He manages to defuse the escalating violence at Gale’s whipping with words, but he participates in a plot to bring down the government that will entail a civil war.

The ray of light that penetrates that very dark cloud in his brain is the moment that Katniss volunteers for Prim. He sees, as do many people in Panem, the power of her sacrifice. And when that carries into her Games, with Rue and Peeta, he slowly begins to believe that with Katniss it might be possible to end the Hunger Games.

DL: I’m also curious about how you balanced the personal and political in drawing the relationship between Katniss and Gale. They have such a history together — and I think you powerfully show the conflict that arises when you love someone, but don’t love what they believe in. (I think that resonates particularly now, when so many families and relationships and friendships have been disrupted by politics.)

SC: Yes, I think it’s painful, especially because they feel so in tune in so many ways. Katniss’s and Gale’s differences of opinion are based in just war theory. Do we revolt? How do we conduct ourselves in the war? And the ethical and personal lines climax at the same moment — the double tap bombing that takes Prim’s life. But it’s rarely simple; there are a lot of gray areas. It’s complicated by Peeta often holding a conflicting view while being the rival for her heart, so the emotional pull and the ethical pull become so intertwined it’s impossible to separate them. What do you do when someone you love, someone you know to be a good person, has a view which completely opposes your own? You keep trying to understand what led to the difference and see if it can be bridged. Maybe, maybe not. I think many conflicts grow out of fear, and in an attempt to counter that fear, people reach for solutions that may be comforting in the short term, but only increase their vulnerability in the long run and cause a lot of destruction along the way.

DL: In drawing Gale’s and Peeta’s roles in the story, how conscious were you of the gender inversion from traditional narrative tropes? As you note above, both are important far beyond any romantic subplot, but I do think there’s something fascinating about the way they both reinscribe roles that would traditionally be that of the “girlfriend.” Gale in particular gets to be “the girl back home” from so many Westerns and adventure movies — but of course is so much more than that. And Peeta, while a very strong character in his own right, often has to take a backseat to Katniss and her strategy, both in and out of the arena. Did you think about them in terms of gender and tropes, or did that just come naturally as the characters did what they were going to do on the page?

SC: It came naturally because, while Gale and Peeta are very important characters, it’s Katniss’s story.

DL: For Peeta . . . why baking?

SC: Bread crops up a lot in The Hunger Games. It’s the main food source in the districts, as it was for many people historically. When Peeta throws a starving Katniss bread in the flashback, he’s keeping her alive long enough to work out a strategy for survival. It seemed in keeping with his character to be a baker, a life giver.

But there’s a dark side to bread, too. When Plutarch Heavensbee references it, he’s talking about Panem et Circenses, Bread and Circuses, where food and entertainment lull people into relinquishing their political power. Bread can contribute to life or death in the Hunger Games.

DL: Speaking of Plutarch — in a meta way, the two of you share a job (although when you do it, only fictional people die). When you were designing the arena for the first book, what influences came into play? Did you design the arena and then have the participants react to it, or did you design the arena with specific reactions and plot points in mind?

SC: Katniss has a lot going against her in the first arena — she’s inexperienced, smaller than a lot of her competitors, and hasn’t the training of the Careers — so the arena needed to be in her favor. The landscape closely resembles the woods around District 12, with similar flora and fauna. She can feed herself and recognize the nightlock as poisonous. Thematically, the Girl on Fire needed to encounter fire at some point, so I built that in. I didn’t want it too physically flashy, because the audience needs to focus on the human dynamic, the plight of the star-crossed lovers, the alliance with Rue, the twist that two tributes can survive from the same district. Also, the Gamemakers would want to leave room for a noticeable elevation in spectacle when the Games move to the Quarter Quell arena in Catching Fire with the more intricate clock design.

DL: So where does Plutarch fall into the just war spectrum? There are many layers to his involvement in what’s going on.

SC: Plutarch is the namesake of the biographer Plutarch, and he’s one of the few characters who has a sense of the arc of history. He’s never lived in a world without the Hunger Games; it was well established by the time he was born and then he rose through the ranks to become Head Gamemaker. At some point, he’s gone from accepting that the Games are necessary to deciding they’re unnecessary, and he sets about ending them. Plutarch has a personal agenda as well. He’s seen so many of his peers killed off, like Seneca Crane, that he wonders how long it will be before the mad king decides he’s a threat not an asset. It’s no way to live. And as a gamemaker among gamemakers, he likes the challenge of the revolution. But even after they succeed he questions how long the resulting peace will last. He has a fairly low opinion of human beings, but ultimately doesn’t rule out that they might be able to change.

DL: When it comes to larger world building, how much did you know about Panem before you started writing? If I had asked you, while you were writing the opening pages, “Suzanne, what’s the primary industry of District Five?” would you have known the answer, or did those details emerge to you when they emerged within the writing of the story?

SC: Before I started writing I knew there were thirteen districts — that’s a nod to the thirteen colonies — and that they’d each be known for a specific industry. I knew 12 would be coal and most of the others were set, but I had a few blanks that naturally filled in as the story evolved. When I was little we had that board game, Game of the States, where each state was identified by its exports. And even today we associate different locations in the country with a product, with seafood or wine or tech. Of course, it’s a very simplified take on Panem. No district exists entirely by its designated trade. But for purposes of the Hunger Games, it’s another way to divide and define the districts.

DL: How do you think being from District 12 defines Katniss, Peeta, and Gale? Could they have been from any other district, or is their residency in 12 formative for the parts of their personalities that drive the story?

SC: Very formative. District 12 is the joke district, small and poor, rarely producing a victor in the Hunger Games. As a result, the Capitol largely ignores it. The enforcement of the laws is lax, the relationship with the Peacekeepers less hostile. This allows the kids to grow up far less constrained than in other districts. Katniss and Gale become talented archers by slipping off in the woods to hunt. That possibility of training with a weapon is unthinkable in, say, District 11, with its oppressive military presence. Finnick’s trident and Johanna’s ax skills develop as part of their districts’ industries, but they would never be allowed access to those weapons outside of work. Also, Katniss, Peeta, and Gale view the Capitol in a different manner by virtue of knowing their Peacekeepers better. Darius, in the Hob, is considered a friend, and he proves himself to be so more than once. This makes the Capitol more approachable on a level, more possible to befriend, and more possible to defeat. More human.

DL: Let’s talk about the Capitol for a moment — particularly its most powerful resident. I know that every name you give a character is deliberate, so why President��Snow?

SC: Snow because of its coldness and purity. That’s purity of thought, although most people would consider it pure evil. His methods are monstrous, but in his mind, he’s all that’s holding Panem together. His first name, Coriolanus, is a nod to the titular character in Shakespeare’s play who was based on material from Plutarch’s Lives. He was known for his anti-populist sentiments, and Snow is definitely not a man of the people.

DL: The bond between Katniss and Snow is one of the most interesting in the entire series. Because even when they are in opposition, there seems to be an understanding between them that few if any of the other characters in the trilogy share. What role do you feel Snow plays for Katniss — and how does this fit into your examination of war?

SC: On the surface, she’s the face of the rebels, he’s the face of the Capitol. Underneath, things are a lot more complicated. Snow’s quite old under all that plastic surgery. Without saying too much, he’s been waiting for Katniss for a long time. She’s the worthy opponent who will test the strength of his citadel, of his life’s work. He’s the embodiment of evil to her, with the power of life and death. They’re obsessed with each other to the point of being blinded to the larger picture. “I was watching you, Mockingjay. And you were watching me. I’m afraid we have both been played for fools.” By Coin, that is. And then their unholy alliance at the end brings her down.

DL: One of the things that both Snow and Katniss realize is the power of media and imagery on the population. Snow may appear heartless to some, but he is very attuned to the “hearts and minds” of his citizens . . . and he is also attuned to the danger of losing them to Katniss. What role do you see propaganda playing in the war they’re waging?

SC: Propaganda decides the outcome of the war. This is why Plutarch implements the airtime assault; he understands that whoever controls the airwaves controls the power. Like Snow, he’s been waiting for Katniss, because he needs a Spartacus to lead his campaign. There have been possible candidates, like Finnick, but no one else has captured the imagination of the country like she has.

DL: In terms of the revolution, appearance matters — and two of the characters who seem to understand this the most are Cinna and Caesar Flickerman, one in a principled way, one . . . not as principled. How did you draw these two characters into your themes?

SC: That’s exactly right. Cinna uses his artistic gifts to woo the crowd with spectacle and beauty. Even after his death, his Mockingjay costume designs are used in the revolution. Caesar, whose job is to maintain the myth of the glorious games, transitions into warfare with the prisoner of war interviews with Peeta. They are both helping to keep up appearances.

DL: As a writer, you studiously avoided the trope of harkening back to the “old” geography — i.e., there isn’t a character who says, “This was once a land known as . . . Delaware.” (And thank goodness for that.) Why did you decide to avoid pinning down Panem to our contemporary geography?

SC: The geography has changed because of natural and man-made disasters, so it’s not as simple as overlaying a current map on Panem. But more importantly, it’s not relevant to the story. Telling the reader the continent gives them the layout in general, but borders are very changeful. Look at how the map of North America has evolved in the past 300 years. It makes little difference to Katniss what we called Panem in the past.

DL: Let’s talk about the D word. When you sat down to write The Hunger Games, did you think of it as a dystopian novel?

SC: I thought of it as a war story. I love dystopia, but it will always be secondary to that. Setting the trilogy in a futuristic North America makes it familiar enough to relate to but just different enough to gain some perspective. When people ask me how far in the future it’s set, I say, “It depends on how optimistic you are.”

DL: What do you think it was about the world into which the book was published that made it viewed so prominently as a dystopia?

SC: In the same way most people would define The Underland Chronicles as a fantasy series, they would define The Hunger Games as a dystopian trilogy, and they’d be right. The elements of the genres are there in both cases. But they’re first and foremost war stories to me. The thing is, whether you came for the war, dystopia, action adventure, propaganda, coming of age, or romance, I’m happy you’re reading it. Everyone brings their own experiences to the book that will color how they interpret it. I imagine the number of people who immediately identify it as a just war theory story are in the minority, but most stories are more than one thing.

DL: What was the relationship between current events and the world you were drawing? I know that with many speculative writers, they see something in the news and find it filtering into their fictional world. Were you reacting to the world around you, or was your reaction more grounded in a more timeless and/or historical consideration of war?

SC: I would say the latter. Some authors — okay, you for instance — can digest events quickly and channel them into their writing, as you did so effectively with September 11 in Love Is the Higher Law. But I don’t process and integrate things rapidly, so history works better for me.

DL: There’s nothing I like more than talking to writers about writing — so I’d love to ask about your process (even though I’ve always found the word process to be far too orderly to describe how a writer’s mind works).

As I recall, when we at Scholastic first saw the proposal for The Hunger Games Trilogy, the summary of the first book was substantial, the summary for the second book was significantly shorter, and the summary of the third book was . . . remarkably brief. So, first question: Did you stick to that early outline?

SC: I had to go back and take a look. Yes, I stuck to it very closely, but as you point out, the third book summary is remarkably brief. I basically tell you there’s a war that the Capitol eventually loses. Just coming off The Underland Chronicles, which also ends with a war, I think I’d seen how much develops along the way and wanted that freedom for this series as well.

DL: Would you outline books two and three as you were writing book one? Or would you just take notes for later? Was this the same or different from what you did with The Underland Chronicles?

SC: Structure’s one of my favorite parts of writing. I always work a story out with Post-its, sometimes using different colors for different character arcs. I create a chapter grid, as well, and keep files for later books, so that whenever I have an idea that might be useful, I can make a note of it. I wrote scripts for many years before I tried books, so a lot of my writing habits developed through that experience.

DL: Would you deliberately plant things in book one to bloom in books two or three? Are there any seeds you planted in the first book that you ended up not growing?

SC: Oh, yes, I definitely planted things. For instance, Johanna Mason is mentioned in the third chapter of the first book although she won’t appear until Catching Fire. Plutarch is that unnamed gamemaker who falls into the punch bowl when she shoots the arrow. Peeta whispers “Always” in Catching Fire when Katniss is under the influence of sleep syrup but she doesn’t hear the word until after she’s been shot in Mockingjay. Sometimes you just don’t have time to let all the seeds grow, or you cut them out because they don’t really add to the story. Like those wild dogs that roam around District 12. One could potentially have been tamed, but Buttercup stole their thunder.

DL: Since much of your early experience as a writer was as a playwright, I’m curious: What did you learn as a playwright that helped you as a novelist?

SC: I studied theater for many years — first acting, then playwriting — and I have a particular love for classical theater. I formed my ideas about structure as a playwright, how crucial it is and how, when it’s done well, it’s really inseparable from character. It’s like a living thing to me. I also wrote for children’s television for seventeen years. I learned a lot writing for preschool. If a three-year-old doesn’t like something, they just get up and walk away from the set. I saw my own kids do that. How do you hold their attention? It’s hard and the internet has made it harder. So for the eight novels, I developed a three-act structure, with each act being composed of nine chapters, using elements from both play and screenplay structures — double layering it, so to speak.

DL: Where do you write? Are you a longhand writer or a laptop writer? Do you listen to music as you write, or go for the monastic, writerly silence?

SC: I write best at home in a recliner. I used to write longhand, but now it’s all laptop. Definitely not music; it demands to be listened to. I like quiet, but not silence.

DL: You talked earlier about researching survival training and edible plants for these books. What other research did you have to do? Are you a reading researcher, a hands-on researcher, or a mix of both? (I’m imagining an elaborate archery complex in your backyard, but I am guessing that’s not necessarily accurate.)

SC: You know, I’m just not very handy. I read a lot about how to build a bow from scratch, but I doubt I could ever make one. Being good with your hands is a gift. So I do a lot of book research. Sometimes I visit museums or historic sites for inspiration. I was trained in stage combat, particularly sword fighting in drama school; I have a nice collection of swords designed for that, but that was more helpful for The Underland Chronicles. The only time I got to do archery was in gym class in high school.

DL: While I wish I could say the editorial team (Kate Egan, Jennifer Rees, and myself ) were the first-ever readers of The Hunger Games, I know this isn’t true. When you’re writing a book, who reads it first?

SC: My husband, Cap, and my literary agent, Rosemary Stimola, have consistently been the books’ first readers. They both have excellent critique skills and give insightful notes. I like to keep the editorial team as much in the dark as possible, so that when they read the first draft it’s with completely fresh eyes.

DL: Looking back now at the editorial conversations we had about The Hunger Games — which were primarily with Kate, as Jen and I rode shotgun — can you recall any significant shifts or discussions?

SC: What I mostly recall is how relieved I was to know that I had such amazing people to work with on the book before it entered the world. I had eight novels come out in eight years with Scholastic, so that was fast for me and I needed feedback I could trust. You’re all so smart, intuitive, and communicative, and with the three of you, no stone went unturned. With The Hunger Games Trilogy, I really depended on your brains and hearts to catch what worked and what didn’t.

DL: And then there was the question of the title . . .

SC: Okay, this I remember clearly. The original title of the first book was The Tribute of District Twelve. You wanted to change it to The Hunger Games, which was my name for the series. I said, “Okay, but I’m not thinking of another name for the series!” To this day, more people ask me about “the Gregor series” than “The Underland Chronicles,” and I didn’t want a repeat of that because it’s confusing. But you were right, The Hunger Games was a much better name for the book. Catching Fire was originally called The Ripple Effect and I wanted to change that one, because it was too watery for a Girl on Fire, so we came up with Catching Fire. The third book I’d come up with a title so bad I can’t even remember it except it had the word ashes in it. We both hated it. One day, you said, “What if we just call it Mockingjay?” And that seemed perfect. The three parts of the book had been subtitled “The Mockingjay,” “The Assault,” and “The Assassin.” We changed the title to Mockingjay and the first part to “The Ashes” and got that lovely alliteration in the subtitles. Thank goodness you were there; you have far better taste in titles. I believe in the acknowledgments, I call you the Title Master.

DL: With The Hunger Games, the choice of Games is natural — but the choice of Hunger is much more odd and interesting. So I’ll ask: Why Hunger Games?

SC: Because food is a lethal weapon. Withholding food, that is. Just like it is in Boris when the Nazis starve out the people of Leningrad. It’s a weapon that targets everyone in a war, not just the soldiers in combat, but the civilians too. In the prologue of Henry V, the Chorus talks about Harry as Mars, the god of war. “And at his heels, Leash’d in like hounds, should famine, sword, and fire crouch for employment.” Famine, sword, and fire are his dogs of war, and famine leads the pack. With a rising global population and environmental issues, I think food could be a significant weapon in the future.

DL: The cover was another huge effort. We easily had over a hundred different covers comped up before we landed on the iconic one. There were some covers that pictured Katniss — something I can’t imagine doing now. And there were others that tried to picture scenes. Of course, the answer was in front of us the entire time — the Mockingjay symbol, which the art director Elizabeth Parisi deployed to such amazing effect. What do you think of the impact the cover and the symbol have had? What were your thoughts when you saw this cover?

SC: Oh, it’s a brilliant cover, which I should point out I had nothing to do with. I only saw a handful of the many you developed. The one that made it to print is absolutely fantastic; I loved it at first sight. It’s classy, powerful, and utterly unique to the story. It doesn’t limit the age of the audience and I think that really contributed to adults feeling comfortable reading it. And then, of course, you followed it up with the wonderful evolution of the mockingjay throughout the series. There’s something universal about the imagery, the captive bird gaining freedom, which I think is why so many of the foreign publishers chose to use it instead of designing their own. And it translated beautifully to the screen where it still holds as the central symbolic image for the franchise.

DL: Obviously, the four movies had an enormous impact on how widely the story spread across the globe. The whole movie process started with the producers coming on board. What made you know they were the right people to shepherd this story into another form?

SC: When I decided to sell the entertainment rights to the book, I had phone interviews with over a dozen producers. Nina Jacobson’s understanding of and passion for the piece along with her commitment to protecting it won me over. She’s so articulate, I knew she’d be an excellent person to usher it into the world. The team at Lionsgate’s enthusiasm and insight made a deep impression as well. I needed partners with the courage not to shy away from the difficult elements of the piece, ones who wouldn’t try to steer the story to an easier, more traditional ending. Prim can’t live. The victory can’t be joyous. The wounds have to leave lasting scars. It’s not an easy ending but it’s an intentional one.

DL: You cowrote the screenplay for the first Hunger Games movie. I know it’s an enormously tricky thing for an author to adapt their own work. How did you approach it? What was the hardest thing about translating a novel into a screenplay? What was the most rewarding?

SC: I wrote the initial treatments and first draft and then Billy Ray came on for several drafts and then our director, Gary Ross, developed it into his shooting script and we ultimately did a couple of passes together. I did the boil down of the book, which is a lot of cutting things while trying to retain the dramatic structure. I think the hardest thing for me, because I’m not a terribly visual person, was finding the way to translate many words into few images. Billy and Gary, both far more experienced screenwriters and gifted directors as well, really excelled at that. Throughout the franchise I had terrific screenwriters, and Francis Lawrence, who directed the last three films, is an incredible visual storyteller.

The most rewarding moment on the Hunger Games movie would have been the first time I saw it put together, still in rough form, and thinking it worked.

DL: One of the strange things for me about having a novel adapted is knowing that the actors involved will become, in many people’s minds, the faces and bodies of the characters who have heretofore lived as bodiless voices in my head. Which I suppose leads to a three-part question: Do you picture your characters as you’re writing them? If so, how close did Jennifer Lawrence come to the Katniss in your head? And now when you think about Katniss, do you see Jennifer or do you still see what you imagined before?

SC: I definitely do picture the characters when I’m writing them. The actress who looks exactly like my book Katniss doesn’t exist. Jennifer looked close enough and felt very right, which is more important. She gives an amazing performance. When I think of the books, I still think of my initial image of Katniss. When I think of the movies, I think of Jen. Those images aren’t at war any more than the books are with the films. Because they’re faithful adaptations, the story becomes the primary thing. Some people will never read a book, but they might see the same story in a movie. When it works well, the two entities support and enrich each other.

DL: All of the actors did such a fantastic job with your characters (truly). Are there any in particular that have stayed with you?

SC: A writer friend of mine once said, “Your cast — they’re like a basket of diamonds.” That’s how I think of them. I feel fortunate to have had such a talented team — directors, producers, screenwriters, performers, designers, editors, marketing, publicity, everybody — to make the journey with. And I’m so grateful for the readers and viewers who invested in The Hunger Games. Stories are made to be shared.

DL: We’re talking on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of The Hunger Games. Looking back at the past ten years, what have some of the highlights been?

SC: The response from the readers, especially the young audience for which it was written. Seeing beautiful and faithful adaptations reach the screen. Occasionally hearing it make its way into public discourse on politics or social issues.

DL: The Hunger Games Trilogy has been an international bestseller. Why do you think this series struck such an important chord throughout the world?

SC: Possibly because the themes are universal. War is a magnet for difficult issues. In The Hunger Games, you have vast inequality of wealth, destruction of the planet, political struggles, war as a media event, human rights abuses, propaganda, and a whole lot of other elements that affect human beings wherever they live. I think the story might tap into the anxiety a lot of people feel about the future right now.

DL: As we celebrate the past ten years and look forward to many decades to come for this trilogy, I’d love for us to end where we should — with the millions of readers who’ve embraced these books. What words would you like to leave them with?

SC: Thank you for joining Katniss on her journey. And may the odds be ever in your favor.

155 notes

·

View notes

Text

the librarians s1e3 "and the horns of a dilemma" watch through:

i always love the joke of the evil minions having super normal conversations. they just took off the black robes and discussed lunch plans.

"im here to do science and math. and occasionally hallucinate." lmaooo

cassandra giggling in delight about wormholes is so relatable

very leverage-y episode, looks like they’re taking down a corrupt agribusiness

ah yes, the extremely real human resources, hidden down the bottom of nowhere

okay the minotaur is a little bit funny lol

i like that we’re getting a whole theory of magic 101 lesson here.

labyrinth as a lingering effect is oddly poetic. tfw you get lost and you never really get out

brain grapes save lives

"i do rule". yes you do ezekiel!!

44 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi Bel,

I have a question related to the lore surrounding the Vex and the way they interact with time. There seems to be debate over if they can time travel vs their advanced simulation technology just makes it seem like they can time travel etc. Would you be able to explain definitely what their capabilities are regarding affecting time? Can they change the past?

They can time travel... sort of. If we're understanding it correctly. But also the way we view time travel and the way the Vex view time travel might not be entirely aligned.

They have to be able to move through time because that's the only way we can actually see Precursors and Descendants; past Vex and future Vex respectively. For example, now in Echoes, a lot of the Vex we fight are Precursors; really odd overall because they appear to be rare. There's some in the Vault of Glass and the Black Garden, but they were mostly located on Mercury. They're old Vex, from the past.

So how can they be here unless the Vex move through time? The same question applies to Descendants, Vex from the future. However, this raises a further question: if they can time travel, why didn't they already achieve their goals? This:

"If the Vex had achieved what we would call 'time travel,' surely none of us would now exist." —Sister Faora, "Theories on the Vex"

A good explanation of this problem is this lore tab from Aspect:

The Vex, they're the closest to understanding it. They've got distance from it. If time's a river, then we're fish and they're diving birds. What's wet mean to a fish? What's it mean to an osprey, who's never fooled by refraction on the water's surface?

+

The Vex understand time in a way we never will. Doesn't matter how long I spend here watching them. Doesn't matter how many jury-rigged portals Guardians fling themselves through. We live in time. They use it as a tool. Any moment that's ever happened, any moment that will ever happen, they can go back to it. Play it again till they get it right. Simulate it.

So why can't they change things fundamentally? Seems to be good old paracausality:

The Light's a counter to that. They come back, a Guardian comes back. They simulate an ending, a Guardian tears through it. Stalemate.

Some of their powers also appear to be just them using time as a tool; teleporting is described as essentially time travelling:

The Minotaur revises its place in history, appearing to teleport forward as it shifts to a more advantageous future.

Simulation allows them to explore possibilities and options at a larger scale, but I believe it's separate from the actual ability to move through time. They can do both, for different purposes, both of which are not entirely clear to us. Paracausality is yet again a problem for them, even for simulation.

There's some technology that was capable of actually making changes, most notably the Sundial. This wasn't made by the Vex, but it was using Vex technology and the whole deal with it was that the Psions were capable of rewriting history with it. The Sundial also allowed us to go into the past, into Saint's personal timeline, and save him, by changing it (and creating a paradox with it).

Another question is the Corridors of Time which the Vex were using to move through time, but it's unclear if they've created that space or not. And one more question are timelines and how does that affect the Vex and their unique relationship with time and other realities. We could also go into the Vault of Glass and Black Garden and other Vex spaces and all of their weirdness with time. There's something going on with it, on top of simulation technology.

In truth, we're not really sure about a lot of stuff with the Vex simply because they have this strange relationship to time that we can't really grasp. Even those that explored the Vex closely like Osiris and Elsie can't really answer some of these questions.

It's a very interesting discussion, so if anyone wants to add to it feel free! Time travel shenanigans are still mostly mysterious and so are the Vex.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daily Rise Quotes: DAY 124

Leo: I can't do it. I got no mystic mojo. I'm useless!

Raph: Hey, that's not true, brother. You just got to believe in yourself, and know this: If I die in this maze, I will haunt you for the rest of your life.

Donnie: Well, in theory you'd both be ghosts, so I'm not sure how you would-

Raph: Donnie, not helping!

(Season 1, Episode 6B - Minotaur Maze)