#mining disaster

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

On 10th January 1947, the West Lothian village of Burngrange was witness to its worst underground mining disaster.

The disaster and rescue attempt were national news, but the impact on the local communities and the victims’ families is still felt today. The flame from a carbide lamp ignited a pocket of firedamp. Only a small explosion was felt at first, but this ignited more gas and within half an hour the timbers and oil shale in the mine were on fire.

Thirty eight men were able to escape, bringing with them the body of John McGarty who had been killed by the initial explosion. Another fourteen men were trapped behind the fire. Despite “one of the most dramatic and gallant rescue bids in the history of mining”, the trapped men could not be reached, and their bodies were brought out of the pit on the 15th of January.

The fifteen victims left behind a total of 11 widows and 26 children. Burngrange was the worst disaster in the history of Scottish shale mining. A memorial to the Burngrange victims was unveiled in 1989 on the Co-op Society clock in West Calder to remember all of the 15 men killed that day.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

June 11, 2019.

Taken in an old catholic cemetery somewhere near the small mining towns of Blairmore and Coleman, just west of the Frank slide, the turtle mountain disaster of 1903 (70-more than 90 deaths) as well as the Hillcrest mining disaster of 1914 (189 out of 228 workers killed) , which happened to be the worst mining disaster in Canadian history. This area is hauntingly beautiful, adorned with abandoned mines and brick buildings and some of the best thunderstorms I have ever seen (basically a guarantee). A general melancholic feeling that sits stagnant in the air, you can’t help but think of all the people that lost their lives, buried under rock, one way or another.

This is one of my favourite areas to visit, and I will always think back to Crowsnest Pass very fondly. If I could ever afford it, I would run away for 2 months and hermit away to write a record here. Ever since I was a kid, I’ve always dreamt of doing so.

Blessed be.

#canadian#canadian gothic#regional gothic#regional goth#midwest gothic#southern gothic#prairie#abandoned#cemetery#crowsnest pass#frank slide#Canadian history#mining disaster#disaster#disasters#haunted#mine#preachers daughter#I will post more from this area as I have a buckets worth of pics#ghost town#mining towns#mining town#prairie gothic#catholic#catholiscism#catholic cemetery

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crowsnest Pass, Alberta, Canada

Part of the former town of Frank was entombed in 1903 by a landslide. Historically the Blackfoot and Kutenai didn't camp there due to the slope's instability.

The scale is difficult to communicate but the larger boulders are building sized.

#photography#my photos#mountains#landscape#valley#pass#crowsnest pass#nature#rockslide#ghost town#mining disaster#abandoned#history#geology#canada

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The bill's fate was clear evidence of the impenetrable nature of the Alabama legislature when major interests were at stake. Martin was a conservative and not at all imbued with crusading zeal. His bill had made no change in the operation of the system. Yet what Martin had done was to attack the very vitals of the institution-he wanted to change where the money went. From the recipients' view, that was the most important matter of them all. Whatever the state did with its prisoners was its own business, but county convicts should be dealt with by the counties.

The merest thought of Martin's changes must have caused fear and trembling (and steely resolve) in every courthouse ring in the state.It was obvious that reform sentiment on the convict lease system was hardly a match for the deeply entrenched status quo. The issues of society often seem to rest on a seesaw, now heavily weighted at one end and skewed in that direction, now slowly rising as some added pressure moves the issue into equilibrium or on to reversal and change. In early 1911, there were no weights causing the side of reform to rise. The newspapers and the public pressure that they fueled were silent. Crusades are episodic; the attention span for reform is incredibly short as new sensations rise to replace the old.

With the tilt toward inaction, the explosion that ripped the Banner Mine threw the heavy weight of shock and surprise on the side of change. Disaster created an air of immediacy. Reopening the question, a Republican newspaper repeated Moulthrop's arguments and called for a change: "It should not be part of the sentence to put inexperienced men in places of danger. The State cannot afford to take the risk of having its convicts killed. Nor is it a square deal to the experienced miners to be forced into competition with convicts." H. M. Wilson, editor of the Opelika Times and a member of the convict board, believed that the sentiment of Alabamians "is overwhelming against the working of convicts in mines." Another editor wrote that "the spirit of commercialism has eaten too far into the system of dealing with our criminal classes. " The voices of change were in the air.

Even so, invoking the arguments of justice, compassion, and every instinct of humanitarianism was plainly not enough. Echoes of former governor Comer's speech still reverberated within the capitol walls: if the convict lease system was abolished, what would take its place? To confine state and county prisoners to a penitentiary would eliminate the lucrative revenues that leasing provided and would place a continuous burden on the state treasury. The progressives were advocates of putting the prisoners to work on public roads and highways-an answer that satisfied their social consciousness with practical results. The state would receive the full benefit of their labor, and-a most naive thought-the convicts would be better protected because their treatment could be scrutinized by the general public. The lines were drawn between the supporters of convict leasing (and their allies, the doubtful and the undecided) and the reformers. The question was whether the balance would change-or could be changed."

- Robert David Ward & William Warren Rogers, Convicts, Coal, and the Banner Mine Tragedy. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1987. p. 82-84.

#banner mine disaster#convict leasing#convict labor#slavery by another name#alabama history#unfree labor#coal mining#coal miners#mining disaster#united states history#academic quote#reading 2024#american prison system#history of crime and punishment

0 notes

Text

The 23rd of June marks the 130th anniversary of the Albion disaster in Cilfynydd. Claiming the lives of 290 men and boys, it is one of the largest colliery disasters in Welsh history. At the time of the disaster work was underway to sink the Dowlais Pit at Aberdare Junction (Abercynon). In anticiption of this, Abercynon was already growing rapidly. A number of men in the area were employed in…

View On WordPress

#Abercynon#Albion disaster#Cilfynydd#Coal#Colliery#History#Local History#Mining Disaster#South Wales

0 notes

Text

The moment Wade handed Mary Puppins to Logan and Logan had no protest beyond groaning, I knew

#Logan... YOU are the father#wade is the mother of dogpool#complaining under his breath and then going “you don't wanna see this bub” to that same dog ten minutes later#Logan twenty years aren't enough to beat out the disaster father you are#you're seeing the ugliest (affectionately. we love peggy the dog here. and wade too. sometimes.) creatures in existence and deciding#mine forever now#Logan you're a Dad#legend says if you collect enough trauma#or if you're a widdle mawy pawpins she's so cute#a wolverine will adopt you#he won't pay child support but at least he'll be present#deadclaws#deadpool and wolverine#deadpool#wolverine#logan howlett#wade wilson#poolverine#deadpool 3#peggy the dog#mary puppins

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Skeleton girl!

#Also based off some ugly ai “art” disaster#mine now biiiitch#this ‘artist’ also sells prints and does commissions#EYE ROLL#YOU DIDNT MAKE SHIT!!!#FUCK AI#anyways#illustration#alternative#digital illustration#art#digital art#fashion#emo#monster girl#skeleton#pinup#pinupgirl#pinup art#pin up girl#halloween

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER | 5.04 "Out of My Mind"

#btvs#spike#harmony kendall#btvsedit#spuffyedit#dailybtvs#slayerdaily#buffysource#dailybuffysummers#tvedit#userveronika#usergiles#usersiesie#userdisco#throwbackblr#buffy x spike#mine#btvs s5#btvs 5x04#totally sane not at all unhinged behavior of a disaster vampire#trying to color this took 10 years off my life

453 notes

·

View notes

Text

okay but can we talk about when ena initially heard students A-C mocking mizuki going like “haha akiyama is cute as ever” with a cruel tone and laughing her first thought wasn’t “what the hell are they implying” but it was “well yeah mizuki has a really cute face” like. girl. i cant

#she’s such a mess. her crush on mizuki is terminal. someone help her.#disaster lesbian supreme fr. i love my pathetic blorbolina#ena shinonome#mizuki akiyama#mizuena#project sekai#prsk#mine

963 notes

·

View notes

Text

New pottery courses available this spring (beginner and advanced level) at the private studio of Britta Wilson (2nd on the Great Pottery Throw Down S4) in Henford-on-Bagley. There are only 5 spots, so enroll now!

#ts4#sims 4#the sims 4#sims 4 interior#sims interior#henford-on-bagley#sims 4 screenshots#simblr#show us your builds#I live for the new clay pack by Syboulette (on tsr)#too bad we can't do pottery in ts4 (although it would be disaster imagine the bugs)#*mine

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

SALTBURN (2023) dir. Emerald Fennell

#saltburn#saltburnedit#felix x oliver#cattonquick#jacob elordi#barry keoghan#filmgifs#filmedit#fyeahmovies#userbeckett#usergreta#userrobin#mine and only mine#moments before DISASTER#oliver's reaction was too damn cute

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

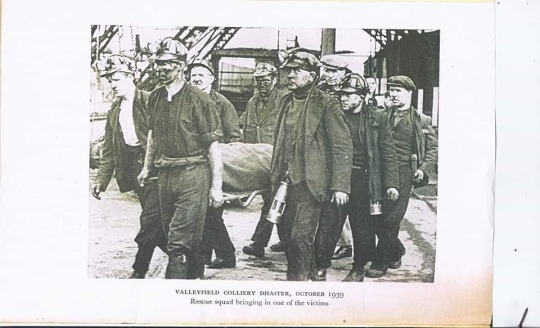

On 28th October 1939, an ignition of firedamp and coal dust caused a devastating explosion in Valleyfield Colliery, killing 35 men.

Many others working deep underground in the early hours of the fateful morning were injured.

It was one of the worst mining tragedies in Fife and came just eight years after 10 men had perished due to carbon monoxide poisoning at Bowhill pit.

News of the explosion brought anxious families from around the west Fife village’s footprint, desperate for news of their loved ones. High and Low Valleyfield bore the brunt but communities from all around were devastated by the scale of the loss. The King and Prime Minister sent messages of condolence and the manager of the colliery and agent of the coal company were later prosecuted and fined.

There were many family connections between the men who lost their lives. Thomas Kerr, of Abbey Crescent, High Valleyfield, was working in the Culross section, and his 27-year-old son, Thomas, was at the coal face where the explosion occurred. The younger man must have been killed instantly, and this news accelerated the death of his father in hospital. “There was no doubt that the shock had this effect,” said a local doctor who arranged for Kerr senior to be sent to hospital. ‘His injuries were only slight, and not sufficient to cause death. He was quite cheerful and smoking his pipe when we took him to hospital. But the news that his son was dead brought about his own death.“

The Dead;

Archibald Anderson, 46, brusher, 44 Abbey Cres, High Valleyfield

David Baillie, 35, brusher, The Ness, Torryburn

Alexander Banks, 65, transport, 6 East Ave, Blairhall (died in hospital)

John Brown, 23, brusher, 8 Bowmont St, Low Valleyfield

David Cairns, 35, brusher, 39 Preston St, High Valleyfield

Thomas Campbell, 56, brusher, Main St, Newmills

Alexander Christie, 61, supervisor, Culross

Thomas Clark, 47, brusher, 34 Abbey Cres, High Valleyfield

William Devlin, 37, machineman, 12 Woodhead St, High Valleyfield

Arthur Doohan, 39, brusher, Burn St, High Valleyfield

Duncan Ewing, 27, brusher, 22 Dundonald Terrace, Low Valleyfield

Aubrey Gauld, 34, brusher, Mid Row, Hill of Beath

Peter Gilliard, 23, brusher, 39 Abbey Cres, High Valleyfield

Edward Glass, 27, transport, 14 Dundonald Ter., Low Valleyfield

David Hogg, 49, packer, Hawthorn Cottage, Carnock

James Irvine, 37, packer, West End, Low Valleyfield

Bert Keegan, 52 brusher, 61 Woodside St, High Valleyfield

Thomas Kerr, 58, 36 Abbey Cres, High Valleyfield (died in hospital)

Thomas Kerr jun, 26, fireman, 36 Abbey Cres, High Valleyfield

Robert Lang, 23, engineer, 6 Preston Cres, High Valleyfield

Alexander Lawrie, 31, brusher, 147 Baldridge Burn, Dunfermline

Edmund Link, 24, transport, Braeside Cottage, Low Valleyfield

James McFadzean, 28, transport, 33 Preston Cres, High Valleyfield

Robert McFarlane, 41, repairer, Main St Newmills

John McIntyre, 22, electrician, 21 Preston Cres, High Valleyfield

Peter Martin, 42, brusher, 5 Abbey Cres, High Valleyfield

Colin Morrison, 51, fireman, 18 Woodhead St, High Valleyfield

Michael Murray, 33, brusher, Burn St, High Valleyfield

Robert Nicholson, 32, brusher, North Rd, Saline

Alexander Paterson, 32, brusher, 19 Abbey Cres, High Valleyfield

William Ramage, 52, brusher, Blairwood Ter, Oakley

James Spowart jun, 29, machineman, Tinian Cres, Newmills

Michael Tinney, 35, transport, 3 Woodhead St, High Valleyfield

Henry Toal, 29, machineman, 26 Preston Cres, High Valleyfield

Robert Wright, 48, brusher, 1 Dunmarle St, High Valleyfield.

More info and news reports on the Scottish mining web site here http://www.scottishmining.co.uk/33.html

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

I just saw your post about western North Carolina. I've been following the situation (mostly through social media) and I'm devastated. This part of the country has always been one of my very favorites to visit (I'm in Georgia) and I want to help if you know of any mutual aid or organizations? I donated to the Red Cross but thought I would ask if you had any suggestions. I'm so sorry this is happening to y'all

i included resources and donation links at the bottom of this post

the great smoky mountains (appalachians) are the most visited national park in the united states, having received over 13 million visitors in 2023. despite this, its residents are hated or at least largely ignored by the majority of the united states. they are portrayed as hillbillies and conservatives that deserve nobody’s time. this is far from the truth. appalachians have been mistreated by the government and general populace for generations. they are given next to nothing and expected to be able to survive that way. it’s disgusting.

everyone who is not from appalachia , i recommend reading more about just how much it and its residents has been abused by the united states government. even reading through the wikipedia article on the social and economic stratification in appalachia can be helpful in understanding how fucked up this area has become due to the abuse of capitalism. i urge everyone to do some research on the coal mining industry when you have the time. not many people know just how bad it really was, and just how much it’s affected the mountains and the people in them.

here are some interesting articles i found on a quick search:

“Coal Mining in Appalachia” by The Moonlit Road

“A History of Appalachian Coal Mines” by Kenneth Lasson

“Coal’s Legacy in Appalachia: Lands, Waters, and People” by Carl E. Zipper and Jeff Skousen

“Nearly 60 years after the war on poverty, why is Appalachia still struggling?” by Dr. Abigail R. Hall Blanco

“Human Rights in Appalachia: Socioeconomic and Health Disparities in Appalachia” by Evan Smith

“Passive, Poor, and White? What People Keep Getting Wrong About Appalachia” by Elizabeth Catte

“Culture, Poverty, and Education in Appalachian Kentucky” by Constance Elam

#meposting#ask#appalachia#appalachian mountains#appalachian history#great smoky mountains#coal mining#north carolina#tennessee#western north carolina#east tennessee#hurricane helene#hurricane#natural disaster#natural disaster relief#hurricane relief#link

386 notes

·

View notes

Text

"By Sunday morning the rain had ceased, and the sun shone brightly. Now the scene around the Banner Mine became one of bustle and excitement as crowds of the curious began to arrive. These "excursionists" came on the trains of the L & N and the Southern; they came by automobile, jarring along the dirt roads; the less affluent and more practical arrived by wagon and "on horseback and mules." One observer was repelled by the scene and reported that the

sights outside were enough to tum a heart of stone. The day being Sunday, the crowds flocked to Banner by the hundreds, and a holiday spirit seemed to possess the most of them."

There

clustered about on the hills and under the trees were the crowds of sight-seers. The air was filled with jokes and ribald jests, while the air also was heavy with the odor of mean whiskey.

Deputy Sheriff Dave Kennybrook and his guards strung up rope and patrolled their lines with rifles and shotguns in an overzealous effort to enforce order and to keep a way clear for the rescuers. The guards dispersed neighboring free blacks who were searching through the castaway clothes of the dead - they were unaware that the prisoners had no valuables. Through it all photographer Bert Covell of Birmingham took pictures of the crowd and of the yawning mine mouth - its darkness a testimony to mystery and fear and tragedy.

Inspector Hillhouse's strategy of reversing the fans to clear the mine gradually proved successful, and the rescue teams were able to penetrate farther into the galleries. Now tram car loads of bodies began to arrive at the surface, and a rush order was made to the Green Coffin Company of Birmingham for one hundred coffins. Other coffins and shrouds came from the John's Undertaking Company in Birmingham, but the supply was soon exhausted, and a special shipment was obtained from Nashville, Tennessee. After being cleaned in the prison washhouse, the bodies were embalmed by Echols and Angevin of Ensley. Their task was so great that the morticians had to be assisted by some of the surviving convicts. Unless families or next of kin called for the bodies, they would be buried on the mine's premises. A gang of twenty convicts began the process of digging "a long trench in the convict cemetery."

If there was curiosity and the compelling ambience of tragedy, there were few signs of bereavement and loss. One elderly black woman cried for her dead nephew. Another sorrowing black woman wept for her husband in the prison morgue. (There was mistaken identity here, and she was led away still crying.) People expected friends and relatives to appear on the scene, and the ambulance chasers of the legal profession were on hand to suggest a claim against the company. But there was little business to be done at the Banner. (Also, Pratt Consolidated's own lawyer, R. B. Watts, was there to safeguard the company from the dangers of litigation.) The locale contrasted sharply with the event. As the sun sank behind the Alabama hills, soft green with the beauty of spring, the observer who had been critical earlier was reinforced in his cynicism. "The crowds began to divide," he wrote.

Food was scarce, and so was whiskey, and the crowds left with the feeling of having had a good time. The blind-tigers [illegal liquor stands] did a land office business and so did the Pratt commissary, where a thin slice of ham and crackers cost ten cents.

- Robert David Ward & William Warren Rogers, Convicts, Coal, and the Banner Mine Tragedy. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1987. p. 22-24

#littleton alabama#banner mine disaster#convict leasing#convict labor#slavery by another name#alabama history#unfree labor#coal mining#coal miners#mining disaster#united states history#academic quote#reading 2024#american prison system#history of crime and punishment

0 notes

Text

HARRIS DICKINSON as samuel in babygirl (2024)

#harris dickinson#hdickinsonedit#harrisdickinsonedit#filmedit#babygirl#harris dickinson.#faceclaims.#mine.#guess who got that babygirl dl link >:)#this was a disaster to color i fear ...

187 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just want you to know that there are worlds out there safe in the sky because of her. That there are people living in the light and singing songs of Donna Noble a thousand million light years away. They will never forget her, while she can never remember. And for one moment, one shining moment, she was the most important woman in the whole wide universe.

David Tennant as Tenth Doctor DOCTOR WHO (2005-) - Series 4

#doctor who#dwedit#david tennant#dtedit#*tenthseasons#userteri#userveronika#usereena#userlanie#userdiana#miatendos#gifs#mine#gif 10: top 5 moments before disaster

2K notes

·

View notes