#michel vovelle

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

03/100 days of productivity ▪︎ 140723

at the beginning of the week it all seemed like it was bound to go wrong but in the end it turned out well.

i have done my last two assessments and now i only have one more to do on ancient american history in paper format.

next week there will be a historical practices event organized by the academic center and we will have a mini workshop on how to read ancient coins and documents.

i m also trying to read more about my research and Michel Vovelle's The French Revolution seem to be a good introduction.

🎧 tales of brave ulysses, cream

to-do's:

start final report of the teaching initiation project

finish the article (I have until Sunday to deliver)

finish at least the first chapter of vovelle's book

#chaotic academia#study#studyblr#100 days of productivity#chaotic academia aesthetic#history#academia#history academia#poc academia#academia aesthetic#grey academia#dark academia#study inspiration#studying#study motivation#grad student#college student#study inspo

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

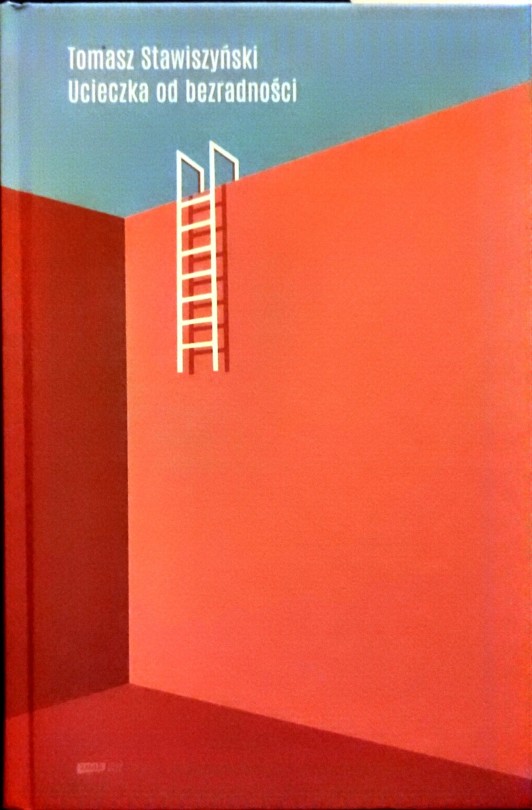

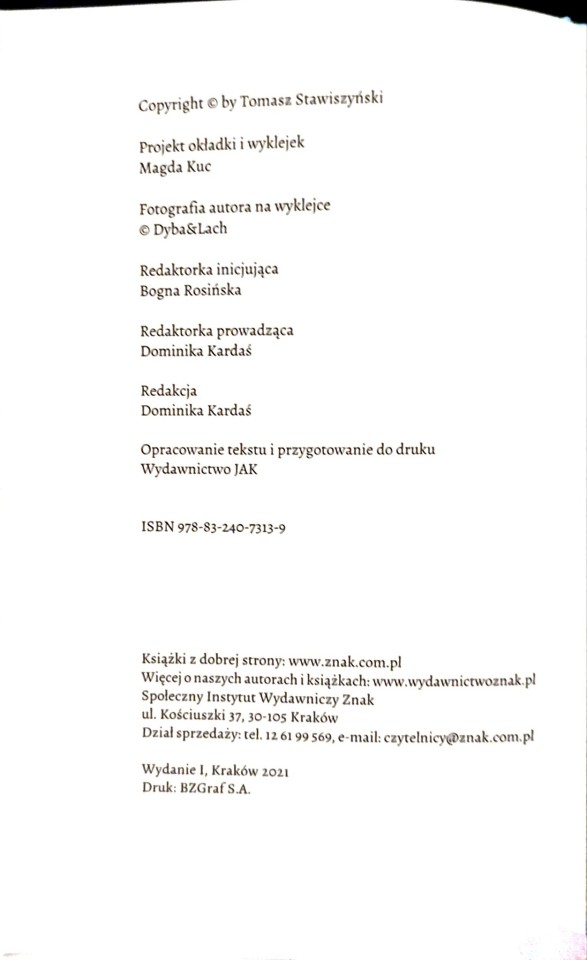

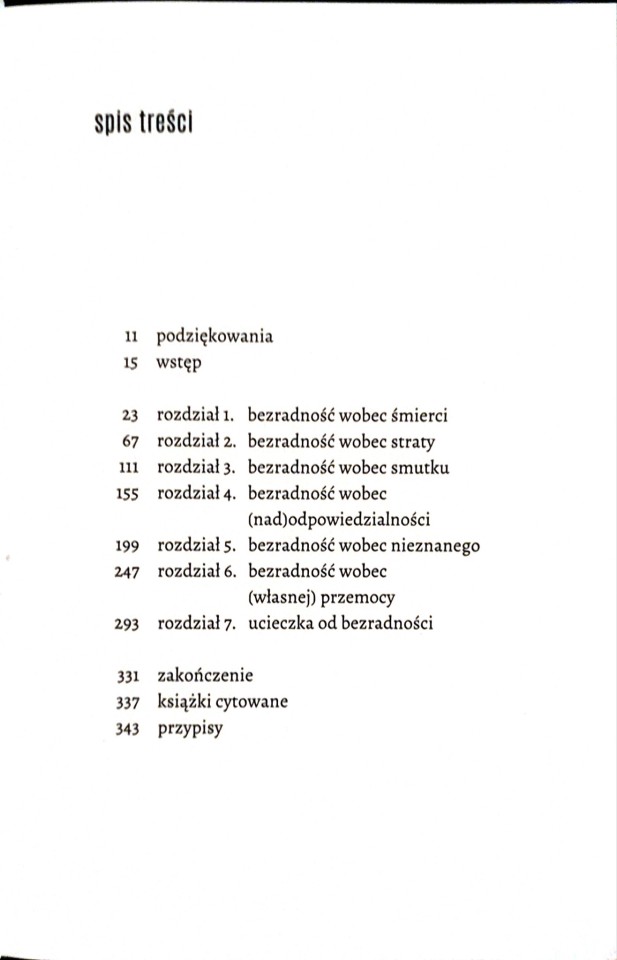

Tomasz Stawiszyński, Ucieczka od bezradności, Znak, Kraków 2021

tymczasowa półka Pianino, pożyczona od Jo

fragments:

Mentions:

Philippe Ariès, Człowiek i śmierć

Barbara Ehrenreich

Geoffrey Gorer

Michel Vovelle, Death in the Western World

0 notes

Text

The three versions:

The first (55 min) is the complete biographical movie. Bonbon, bad wigs, impressionist nightmares, the whole thing.

The second (1 hr 20 min) is a documentary that intersperses most of the scenes from the dramatization with discussions about his life and legacy in interviews with various people, including historians, politicians, and Robespierre himself:

The third (1 hr 30 min), which I haven’t watched yet but am planning to this week, looks back 30 years after the Bicentenary with new interviews. From the description:

“His life and his exercise of power are confronted, thirty years apart, with the analyses, judgments of historians and politicians of the Bicentenary and the beginning of the 21st century: Michel Vovelle, Michel Biard, Hervé Leuwers, Patrice Gueniffey, Jacques Chaban-Delmas, Michel Debré, Lionel Jospin, Jean Louis Bourlanges, Alexis Corbière.”

@sn1054 has just mentioned that this updated edition of Hervé Pernot's Robespierre film (with Christophe Allwright as Maximilien) is now available for streaming. I got the DVD of it t'other year, and can recommend. The dramatised segments were filmed at the time of the Bicentenary, but are now framed by discussions of modern historians and political figures.

#I’m looking forward to hearing from Biard and Leuwers#robespierre#frev movies#french revolution#frev

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Recommendations on the French Revolution (the "short" list version)

(For some reason, the original anonymous ask and answer I thought I had saved in my drafts has disappeared? Did I accidentally delete it? Who knows with Tumblr. Anyway, good thing I screenshotted it, I guess.)

Since I am STILL working on my extremely long post series going in depth into recommendations, I guess I should really just answer this ask and give a plain and simple list, as it was requested -_- (Don't worry, the extremely long post series is still going to happen.)

First of all, let’s just say, again (and it really must be insisted on), that most Anglophone historiography is… not very good. There are exceptions, but not many. At least, not enough to satisfy me. Fortunately, some good French books have been translated to English – so that’s great news!

So here are my main recommendations:

Sophie Wahnich’s La liberté ou la mort. Essai sur la Terreur et le terrorisme (2003) which was translated to In Defence of the Terror: Liberty Or Death in the French Revolution with a foreword by Slavoj Zizek in 2012.

This essay basically changed my life, and led me to take the path I have walked since as a historian. Zizek’s foreword is very good in summarizing the ideological oppositions to the French Revolution (until he rambles the way he usually does).

It opens with a quote from Résistant poet René Char which perfectly sets the tone:

“I want never to forget how I was forced to become – for how long? – a monster of justice and intolerance, a narrow-minded simplifier, an arctic character uninterested in anyone who was not in league with him to kill the dogs of hell.”

Keep in mind that when I first read it, in 2003, the very notion of anything like the Charlottesville rally happening was still in the realm of pure fantasy.

Marie-Hélène Huet’s Mourning Glory: The Will of the French Revolution (1997). One of the rare books in my list that was originally written in English (!). I think a lot of it might be available to read via Google Books, but it’s worth buying.

This book is hard to categorize: it talks of historiography and ideology, and it’s overall a fascinating book.

It feels a lot like Sophie Wahnich’s first essay – it was also similarly influential on my research. It inspired a lot of my M.A. thesis. I’ve recently found my book version of it, and this book was annotated like I’ve rarely annotated a book. It was quite impressive.

Dominique Godineau’s Citoyennes Tricoteuses: Les femmes du peuple à Paris pendant la Révolution française (1988) which was translated to The Women of Paris and Their French Revolution (1998).

It’s the best book on women’s history during the French Revolution IMO. I really don’t have much more to say about it: it’s excellent. It talks of working class women, it talks of the conflicts between different women groups, it talks of what happened after Thermidor and the Prairial insurrections, and the women who were arrested. No book has compared to it yet.

Jean-Pierre Gross’s Fair Shares for All: Jacobin Egalitarianism in Practice (1997). You can download it for free via The Charnel House (link opens as pdf).

Another rare book that was originally written in English, and later translated to French, though the author is French! (I think some French authors have picked up that the real battlefield is in Anglophonia…) It’s very important to understand social rights, a founding legacy of the French Revolution.

François Gendron’s essential book on the Thermidorian Reaction: first published in Québec as La jeunesse dorée. Episodes de la Révolution française (1979) (The Gilded Youth. Episodes of the French Revolution). It was then published in France as La jeunesse sous Thermidor (The Youth During Thermidor). As I explained here, its publication history is quite controversial (though it seems no one noticed?). It was thankfully translated to English as The Gilded Youth of Thermidor (1993). However, the English translation follows Pierre Chaunu’s version – which didn’t alter the content per se, but removed the footnotes and has a terribly reactionary foreword – so be careful with that. If anything, that’s a very good example of all the problems in historiography and translations.

Much like Godineau’s book on women, no book can compare. In the case of women’s history during the French Revolution, it’s because most of it is abysmally terrible; in the case of the Thermidorian reaction, it’s because no one talks about it. And it’s not surprising once you start reading about it.

(You might notice that Gendron’s translated book, much like many others, are prohibitively expensive. I do own some of these so if you ever want to read any, send me a message and we’ll work it out!)

Antoine de Baecque’s The Body Politic. Corporeal Metaphor in Revolutionary France, 1770-1800 (1997), which is a translation of Le Corps de l’histoire : Métaphores et politique (1770-1800) (1993). (Here’s the table of contents.) It’s a peculiar book belonging to a peculiar field, and it can be a bit complicated/advanced in the same way most of Sophie Wahnich’s books are, but I still recommend them. See also: La gloire et l’effroi, Sept morts sous la Terreur (1997) and Les éclats du rire : la culture des rieurs aux 18e siècle (2000), but I don’t think either have been translated. Le Corps de l’histoire and La gloire et l’effroi also are nice complements to Marie-Hélène Huet’s book.

If you can read French, I really recommend the five essays reunited in Pour quoi faire la Révolution ? (2012), especially Guillaume Mazeau’s on the Terror (La Terreur, laboratoire de la modernité) – which I might try to eventually translate or at least summarize in English coz it’s really worth it.

The following books are extremely important to understand the historiographical feud and the controversies that surrounded the Bicentennial of the French Revolution in 1989 (and both have been translated to French so that’s cool too):

First, Steven L. Kaplan’s two volumes called Farewell, Revolution: Disputed Legacies (1995) and The Historians’ Feud (1996).

Then, Eric Hobsbawm’s Echoes of the Marseillaise: Two Centuries Look Back on the French Revolution (1990) which gives you the Marxist perspective on the debate. If you want to look for the non-Marxist perspective: look at literally any other book written on the French Revolution and its historiography (I’m not kidding). For example, you can read the introduction by Gwynne Lewis (1999 book edition; 2012 online edition) to Alfred Cobban’s The Social Interpretation of the French Revolution (1964), the founding “revisionist” book.

Again, if you can read French, I recommend Michel Vovelle’s Combats pour la Révolution française (1993) and 1789: L’héritage et la mémoire (2007). I have not read La bataille du Bicentenaire de la Révolution française (2017) but it might recycle parts of the previous two books, so I’d look that up first.

Marxist historiography is near inexistant in Anglophonia, because of reasons best explained in this short historiographical recap on Anglophone historiography and specifically Alfred Cobban (link opens as pdf), but there was Eric Hobsbawm, who wrote a series of very important books on “The Ages of…”:

The Age of Revolution: 1789-1848

The Age of Capital: 1848-1875

The Age of Empire: 1875-1914

The Age of Extremes: 1914-1991

Some of Albert Soboul’s works have been translated as well:

A Short History of the French Revolution, 1789-1799 (1977)

The Sans-Culottes: The Popular Movement and Revolutionary Government, 1793-1794 (1981)

Understanding the French Revolution (1988), which is a collection of various essays translated to English (here’s the table of contents)

While we’re on the subject of classics: I do need to re-read R. R. Palmer’s The Twelve Who Ruled (1941) to see if I still like it, but I believe it’s still positively received? I’ve never actually read C. L. R. James’ The Black Jacobins. Toussaint Louverture and the San Domingo Revolution (1963) but I’m going to rectify that this summer.

That’s a good way to segue into a final part.

Here is a list of books I technically have not read yet (I skimmed through them), but would still recommend because I trust the authors:

Michel Biard and Marisa Linton’s The French Revolution and Its Demons (2021) which was originally published in French as Terreur ! La Révolution française face à ses demons (2020). It looks like an excellent summary of all the controversies surrounding the Terror: Robespierre’s black legend, how the Terror was “invented”, the conflicts between different political factions and clubs, the Vendée, and stats on who actually died by the guillotine (no, there was no “noble purge”). (Here’s the table of contents.)

Peter McPhee wrote several good syntheses, the most recent being Liberty or Death: The French Revolution (2017). Others he wrote: Living the French Revolution, 1789-99 (2006) and A Social History of France, 1789-1914 (1992, reedited in 2004). Why 1914? The 19th century was defined by Hobsbawm (see above) as “the long 19th century” (by contrast with “the short 20th century”), or “the cultural and political 19th century”, which is regarded as lasting from the fall of Napoléon Bonaparte to the First World war.

Eric Hazan’s A People’s History of the French Revolution (2014) and A History of the Barricade (2015), which are translations (Une histoire de la Révolution française, 2012, and La barricade: Histoire d’un objet révolutionnaire, 2013). If you can read French, check out his essay published by La Fabrique: La dynamique de la révolte. Sur des insurrections passes et d’autres à venir (2015).

Just as a final note: this post is the equivalent of four half single-spaced pages in Times New Roman 12 pts. It also took two hours to write and format (and make the side-posts with table of contents) even though most of it is already written in several drafts – i.e. the long post series of in-depth recommendations, so that gives you an idea of why that other series of posts is taking so long to write.

I’m going to go lie down now. -_-

ETA: Corrected some typos and a link that didn't quite go to the right place.

#historiography#frev historiography#sophie wahnich#marie helène huet#antoine de baecque#michel vovelle#michel biard#marisa linton#eric hazan#peter mcphee#c. l. r. james#r. r. palmer#albert soboul#eric hobsbawm#françois gendron#francois gendron#dominique godineau#steven l. kaplan#jean pierre gross#alfred cobban#slavoj žižek#slavoj zizek#this post almost killed me

394 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Atheism during the French Revolution (Michel Vovelle)

It is not easy to deal with the reality of atheism in revolutionary France, inasmuch as the term, insistently invoked in the antagonistic speeches of the era, has been laden with political ulterior motives, in the frame of controversies wherein the very notion has constantly been expanded, giving a connotation to the term which was generally very pejorative. In the European debate, Pitt, among others, denounced revolutionary impiety in 1793 by referring to the atheist declarations of Guadet or of Jacob Dupont. But the accusation of atheism also finds itself in the indictment of Chaumette or Gobel, accused of having « formed a coalition » in order to erase every notion of divinity and of wanting to found the French government on atheism.

Based on this heritage, has one seen many more atheists than there actually were, by inaccurately viewing the Cult of Reason in Year II as a manifestation of atheism? This is what A. Aulard (in « Le culte de la Raison et le culte de l'Etre Suprême ») is not far from reproaching his predecessors for, those who were distressed by the phenomenon, like Buchez or Louis Blanc, as well as those who were delighted by it, such as Tridon and the defenders of the Hébertists. But he himself, as a counterpoint, tends to underestimate the number of unquestionable atheists, even pondering on Cloots, Hébert or Sylvain Maréchal, to such an extent that one can wonder if there was any real consistence at the time.

If one turns to the beginning of the era, one can say, perhaps oversimplifying, that the great generation of atheist materialism of Diderot, Le Mettrie, Helvetius or Holbach, at the time of the Encyclopédie, was not responsible for the dominant current of sensibilité, nourished among the revolutionaries by the reasoned deism of Voltaire and, even more, by the religiosity of the Rousseau of La Profession de foi du vicaire savoyard. From the survivors of the group, one can barely cite Naigeon, who intervened through an anonymous writing in the beginning of the Revolution in the discussion if the preamble of the Constitution should include an invocation to the Supreme Being, but who then showed himself to be discreet, even if he appears to have muttered (in secret) in Year II, on « this monster of Robespierre » and his decree on the Supreme Being.

Even if there was discussion on this in the Constituent Assembly, one knows that it would turn out in favour of religion and, more still, that the very existence of divinity was not questioned.

Before the summer of 1793, one could, throughout the verbal skirmishes, only hardly glimpse the problem and suspect an avowed atheism: but when on 2 June 1792, Delacroix, a friend of Danton, proposed to destroy the Catholic religion and to replace the images of saints with the ones of Rousseau and Franklin, he still caused a scandal at the Jacobin Club. Already in March of the same year, a significant escapade had opposed the sceptic Guadet to Robespierre in the club on the appeal to providence. Although the duel had neither a winner nor a loser, it was significant, as this scandal was provoked by deputy Jacob Dupont's profession de foi of atheism and his explanation of the position in his « Glorification of science as religion ». In September of the same year, the debate started again when the Incorruptible campaigned against the memory of Helvetius, to whom one had planned to dedicate a street in Paris (the rue Sainte-Anne). Robespierre triumphed, as one smashed the bust of the philosopher at the club at the same time as the one of Mirabeau, but not without provoking criticism in the press (Proudhomme's Les Révolutions de Paris), but also among the Girondins. It was among them, no doubt, as well as in the part of the Montagne which would later gather around Danton, that one could encounter one of the groups which aligned themselves with the atheism in the tradition of the Encyclopédie, which Condorcet claimed to adhere to. During the discussion of drafts relating to the new Constitution of 1793, Condorcet removed the reference to the Supreme Being from the preamble which he proposed. The obscure deputy Pomme vainly attempted to have it re-established: but Robespierre did not forget that Vergniaud and Gensonné had « perorated » against divinity.

A transitional stage was proposed by the festival of 10 August 1793 in celebration of the acceptance of the constitutional act, which saw a gigantic stature of Nature, pressing her breasts in order to make the water of regeneration flow from them, being erected on the site of the Bastille. The speech of the sitting president of the Convention, Hérault de Séchelles, was completely imbued with a pagan cult of Nature, avoiding any resort to divinity. Was it a matter of atheism in the strict sense of the term? One can discuss this, as one can observe that this ceremony, which was, for that matter, beautifully executed, did seemingly not mobilise the masses. Fifteen days later, as the Convention received petitioners, the message of the unhappy schoolchild who demanded that one educates of the youth instead of preaching in the name of a so-called God still provoked the disapproval of the assembly, which manifested in a "movement of indignation". One can therefore be surprised to see how, in Brumaire Year II, the crisis of dechristianisation provoked the emergence of a discourse that was clearly anti-Christian, where atheism is at last underlying in the speech of Léonard Bourdon on 16 Brumaire, or in the work of Maire-Joseph Chénier, whose song for the Festival of Reason of 24 Brumaire includes the lines: "Descend, O Liberty, daughter of nature / ... You, Holy Liberty, come to inhabit this temple / Be the goddess of the French", clarifying his thought elsewhere in the form of a plan of a veritable secular religion, « the only universal religion who has neither sects nor mysteries, whose sole dogma is equality ... and which only burns the incense of the great family in front of the altar of the patrie, the common mother and divinity ». But the surprise is even greater in measuring the penetration and the maturity of these concepts throughout the speeches that were delivered in the sections of Paris: « As for us, we adopt the religion of philosophy, the one of Liberty, of Humanity. This is our morality, and morality does not want any other cult » (citizen Barry, Section Guillaume Tell).

But here, one can, with Aulard, ask oneself: were all of the déchristianisateurs atheists, is it legitimate to assimilate the Cult of Reason to atheism? Anacharsis Cloots was indisputably a declared atheist, whose republication of the pamphlet « La certitude des preuves du mahométisme » was received by the Convention on 27 Brumaire, wherein he observed the inanity of all religions and suggested to raise a statue to Curé Meslier. Can one also doubt, in spite of his ultimate palinodes which Aulard seems to take seriously, the atheism of Hébert, who, on 17 Brumaire, attacked Laveaux, the editor of Le Journal de la Montagne who had defended divinity, for having « opened on God, an unknown being, an abstract of disputes which only are suitable for a Capuchin friar in theology ». The same Hébert made the Père Duchesne say to his wife Jacqueline: « I do not believe more in their hell and in their paradise than in Jean de Vert. If there is a God, which is not too clear, he did not create us so that we torment ourselves, but in order to be happy ». Likewise, it does not seem reasonable to me to doubt the atheism of Sylvain Maréchal, already known for his Almanach des honnêtes gens pour l'année 1788, which he had dated « Year I of Reason ». According to Aulard, through Chaumette, a tenderised Rousseauist, one reached the antipodes of unadulterated atheism. But the provinces have known, among the representatives en mission who then spread the good word, representatives of a militant atheism: Fouché, ordering to write on the doors of the cemeteries « Death is an eternal sleep », and to build a temple of love as he ignited the holy fire of Vesta, can only be suspected of militant paganism. But one can cite, in this list, Couturier in Grenoble (« I will not address the question if there is a creator... »). Athanase Veau in Tours (« In order for us to love the Patrie / Do we need priests or gods? ») and, above all maybe, Lequinio, who made a signficant materialist profession of faith in Rochefort on 20 Brumaire: « No, citizens, there is no future life, no! Of us, there will always only remain the divided molecules which formed us and the memory of our past existence ». From the author of an opuscule on « the destroyed prejudices » in 1792, this declaration is less surprising than his palinode following Robespierre's speech of 1 Frimaire. The most consistent and, undoubtedly, the most interesting of these militant atheists is surely J. B. Salaville, the editor of the « Annales patriotiques et littéraires », who, from Brumaire to Nivôse, defended the line of an atheism without concessions in a series of articles with real merit, defying any returns of the sacred, whose carrier the Cult of Reason could be, as well as the one of the martyrs of Liberty. For him, atheism far from being aristocratic, it was the idea of an almighty God that was despotic. The ambiguity is obvious: much as it seems to us that Aulard is hypercritical when he contests the atheism of the movement's leaders, we agree with him when he thus counts, throughout the discourse of the Paris sections, a strong majority of deist professions of faith, orators for whom Reason is already the emanation of the Supreme Being. When examining the provincial addresses collected on the desk of the Convention, the trait is confirmed, even if there, the dominant tendency is to make Reason a daughter of Nature...

One cult can hide another one: but if the Supreme Being is already hidden behind Reason, one can better understand the attitude of not only Robespierre and his friends, but of Danton and some others, at the same time as the political framework, operating around the denunciation of atheism, assumed its full dimension. The Incorruptible took the offensive on 1 Frimaire, in his famous intervention: « There are men ... who, under the pretext of destroying superstition, want to make a sort of religion out of atheism itself ... Atheism is aristocratic. The idea of a great being is popular ... » Behind the unquestionable sincerity of this profession of faith, the political process sidles in, which would come to present the déchristianisateurs, who were predominately deists, as atheists. Danton, vaguely naturalist, in the manner of Hérault de Séchelles or Fabre d'Eglantine, associated himself with the Robespierrist line in the context of the fight against Hébertism. He was the first one to suggest, on 6 Frimaire, to celebrate the Supreme Being. In the aftermath of the decree on religious freedom of 16 Frimaire, Hébert was attacked directly for his atheism by Bentabole, and Cloots by Robespierre: the last palinode of the Père Duchesne would not save him. We have seen how atheism has been held as the primary charge against Chaumette and Gobel. The defining moment of this crusade against atheism finds itself in Robespierre's report of 18 Floréal Year II, when he added the anathema on the sect of the Encyclopédistes (« Unhappiness to the one who seeks to extinguish this sublime enthusiasm ») to a retrospective condemnation of Hébertism. The great festival of the Supreme being would see the ignition of the statue of atheism: thousands of addresses flowed from the provinces, sometimes explicit in their condemnation of atheism, quite often also evidence for the natural and seemingly spontaneous manner in which the transition from the Cult of Reason to the Supreme Being took place. In his speech of 8 Thermidor, Robespierre nominally and violently attacked Fouché: « No, Fouché, no, death is no eternal sleep! Erase this impious maxim and replace it with these words: death is the beginning of immortality. »

After Thermidor, atheism again became the luxury of a few, heirs of the Encyclopédistes, who upheld the tradition: C. F. Dupuis, who published « L'origine de tous les cultes », P. L. Ginguené, the author of « De l'obstination religieuse », or chevalier De Parny, the author of the gigantic, syncretico- copulative epic that is « La guerre des Dieux », where Walhalla, Olympus and the Christian heaven clash in a fray that is chaotic, but not without approvals. One is far from the great traumatism of Year II. But, in a state of shock, atheism maybe became « aristocratic » only in appearance.

Source: Dictionnaire historique de la Révolution française (Albert Soboul)

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book suggestions.

Dear citoyens.

For my bachelor thesis, I would like to receive some suggestions for literature and primary sources. For my thesis, I would like to research the concept of civil religion during the French Revolution (Rousseau...), The Cult/Festival of the Supreme Being, Robespierre’s religious thought, dechristianisation.

Merci beaucoup.

My booklist, so far (under cut):

Jonathan Smyth, Robespierre and the Festival of the Supreme Being. The search for a republican morality.

Michel Vovelle, Religion et révolution. La déchristianisation de l’an II.

Michel Vovelle, La révolution contre l’église.

Albert Mathiez, Robespierre et le culte de l’être suprême.

François Furet et Mona Ozouf, A critical dictionary of the French Revolution.

Henri Guillemin, Robespierre, politique et mystique.

Michaël Culoma, La religion civile de Rousseau à Robespierre (have anyone read this book or know it? Because I have to purchase this book).

#robespierre#religion civile#civil religion#frenchrevolution#cult of supreme being#religion#rousseau#f

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

sorry if you've already gotten a question like this, but what are your current favorite books? which ones would you recommend?

this is what i'm "currently reading": robespierre and the festival of the supreme being by johnathan smyth

one god: pagan monotheism in the roman empire by stephen mitchell & peter van nuffelen

the revolution against the church by michel vovelle

law, labor, and ideology in the early american republic by christopher l. tomlins

the nomos of the earth by carl schmitt

political theology by carl scmitt

rome reborn on western shores by eran shalev

the enigmatic reality of time by michael f. wagner

selected letters by cicero

corporatism and consensus in florentine electoral politics by john m. najemy

dune by frank herbert

quicksilver by neal stephenson

nature’s god: the heretical origins of the american republic by matthew stewart neoplatonic saints: the lives of plotinus and proclus by their students

fichte's republic by david james

coordination and information: historical perspectives on the organization of enterprise by lamoreaux & raff

pan the goat god: his myth in modern times by merivale

rethinking roman alliance: a study in poetics and society by gladhill

the selected letters of ralph waldo emerson

scientific cosmology and international orders by allan

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quelques recommandations de lecture sur la politique économique et sociale de la Convention montagnarde

On m’a demandé des recommandations de lecture sur “la politique économique des jacobins en l’an 2” et j’ai pensé faire un post là-dessus et parce que ça pourrait éventuellement être utile à d’autres qu’à la personne qui a fait la demande et pour me distraire un moment de ma maladie. Seulement — même si l’on continue malgré tout à l’utiliser, même parfois parmi les historiens — ce terme de “jacobins” ne veut rien dire, au-delà de “membres de la Société des amis de la constitution puis de la liberté et de l’égalité”. Je donne donc plutôt des recommandations sur la politique économique (et sociale, puisqu’on peut difficilement séparer les deux) de la Convention montagnarde.

Malheureusement, je ne connais pas de bonne synthèse globale à ce sujet.

Cependant, je peux citer quelques lectures utiles :

D’abord, il y a de bons chapitres consacrés à ces politiques dans Jean-Pierre Gross, Égalitarisme jacobin et droits de l’homme, Paris, Éditions Kimé, 2016 (2000) (même si j’ai des désaccords avec Gross sur certains points) et dans la thèse récente d’Aurélien Larné sur Pache et la commune de Paris en 1793-an II (on peut d’ailleurs lire le texte qu’il a présenté au séminaire L’Esprit des Lumières et de la Révolution sur la production de guerre à Paris à cette époque en ligne). Il y a aussi un excellent résumé théorique au chapitre 5 du nouveau livre de Yannick Bosc, Le peuple souverain et la démocratie. Politique de Robespierre, Paris, Éditions critiques, 2019 : “L’économie politique populaire : la démocratie pour contrôler le marché”.

Edward P. Thompson, Valérie Bertrand, Cynthia A. Bouton, Florence Gauthier, David Hunt et Guy Ikni, éd., La guerre du blé au XVIIIème siècle. La critique populaire contre le libéralisme économique, Paris, 1988, (réédition Paris, Kimé, 2019) est également un ouvrage très utile, mais qui ne porte pas principalement sur l’époque du gouvernement révolutionnaire.

Parmi les ouvrages plus anciens mais toujours utiles on peut citer (entre autres) :

Richard Cobb, Terreur et subsistances, 1793-1795, Paris, Librairie Clavreuil, 1965.

Florence Gauthier, La voie paysanne dans la Révolution française. L’exemple de la Picardie, Paris, F. Maspero, 1977.

Albert Mathiez, La vie chère et le mouvement social sous la Terreur, Paris, Payot, 1927. (Voir aussi quelques-uns de ses articles réédités récemment sous le titre Robespierre et la République sociale, Paris, Éditions critiques, 2018)

Georges Lefebvre, Questions agraires au temps de la Terreur, Strasbourg, F. Lenig, 1932.

Albert Soboul, Les sans-culottes parisiens en l'an II. Mouvement populaire et gouvernement révolutionnaire : 2 juin 1793 - 9 thermidor an II, Paris, Librairie Clavreuil, 1958.

Albert Soboul, Problèmes paysans de la Révolution (1789-1848), Paris, Maspero, 1976.

Il y a aussi de bons articles dans Michel Biard, éd., Les politiques de la Terreur, 1793-1794, Rennes, Presses Universitaires de Rennes et Paris, SER, 2008 et je peux encore citer quelques articles que moi j’ai trouvé utiles dans les Annales historiques de la Révolution française ou ailleurs (ils sont pour la plupart disponibles soit sur Persée, pour les plus anciens, soit sur le site des AHRF, soit sur CAIRN ou Academia.edu, pour les plus récents) :

Manuela Albertone, « Une histoire oubliée : les assignats dans l’historiographie », Annales historiques de la Révolution française, 287 | janvier-mars 1992, p. 87-104.

Gérard Béaur, « Révolution et redistribution des richesses dans les campagnes : mythe ou réalité ? », Annales historiques de la Révolution française [en ligne], 352 | avril-juin 2008.

Michel Biard, « Législation et question agraire sous la Révolution française », Cahiers d’histoire, 74, La terre et les paysans aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles en France et en Angleterre, 1999, p. 57-74.

Françoise Brunel, « La politique sociale de l’an II : un “collectivisme individualiste” » dans Stéphanie Roza et Pierre Serna, éd., Le Républicanisme social : une exception française ?, Paris, Publications de la Sorbonne, 2014, p. 107-128.

Florence Gauthier, "Une révolution paysanne ou Les caractères originaux de l’histoire rurale de la Révolution française", Révolution-Française.net, septembre 2011.

Florence Gauthier, “Critique du concept de “révolution bourgeoise” appliqué aux Révolutions des droits de l’homme du XVIIIe siècle”, Révolution-Française.net, mai 2006.

Guy Ikni, “La république au village en l’an II” dans Michel Vovelle, éd., Révolution et République, Paris, Kimé, 1994, p. 252-262.

Je citerai aussi quelques ouvrages sur l’économie à l’époque révolutionnaire (ou quelques aspects de la question), par souci d’exhaustivité, mais comme je n’ai pas encore eu le temps de les lire moi-même, je ne peux pas les recommander (le premier et le dernier, je les ai consultés, mais pas lus en entier) :

Bernard Bodinier et Éric Teyssier, L’Événement le plus important de la Révolution, la vente des biens nationaux en France et dans les territoires annexés, 1789-1867, Paris, SER, 2000.

Nicole Hermann-Mascart, L’emprunt forcé de l’an II. Un impôt sur la fortune, Paris, Aux Amateurs de Livres, 1990.

Guy Lemarchand, L’économie en France de 1770 à 1830. De la crise de l’Ancien régime à la révolution industrielle, Paris, Armand Colin, 2008.

Jean-Michel Servet, éd., Idées économiques sous la Révolution. 1789-1794, Lyon, PUL, 1989.

Nadine Vivier, Propriété collective et identité communale. Les biens communaux en France, 1750-1914, Paris, Publications de la Sorbonne, 1998.

Enfin, il y a quelques travaux en cours qui n’ont pas encore été publiés, mais qui peuvent se révéler intéressants : Serge Aberdam et quelques autres travaillent à une traduction d’un ouvrage ancien mais apparemment toujours utile sur les assignats et il y a eu une colloque en 2018 sur “Les dynamiques économiques de la Révolution française” dont on doit publier prochainement les actes.

#Révolution française#recommandations de lecture#il se peut que j'aie oublié quelque chose#n'hésitez pas à signaler tout ouvrage que j'aurai omis

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

sei febbraio

Licurgo Sommariva

Nelle vastissime notti io sento il rumore dell’ossatura delle cose, gli alberi che battono sulle strade. La terra tesa con spasimo che potrebbe schiantarsi come il ghiaccio di un lago. Io debbo reagire per non farmi sovrastare dal rumore del mio corpo, per non farmi tendere come la pelle della terra. Cerco di spezzare le corde che stirano ogni cosa.

(Paolo Volponi)

View On WordPress

#Bob Marley#Claudio Arrau#François Truffaut#Francesca Rigotti#Jin Yong#Licurgo Sommariva#Michel Vovelle#Orio Vergani#Paolo Volponi#Sergio Corazzini#Ugo Foscolo

0 notes

Photo

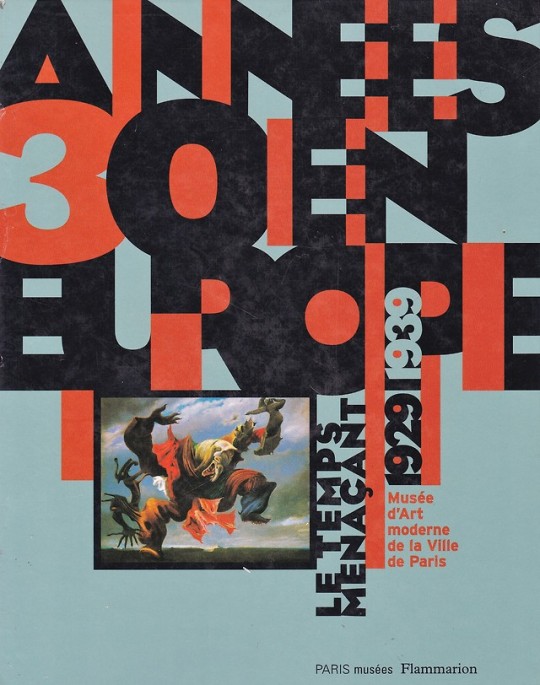

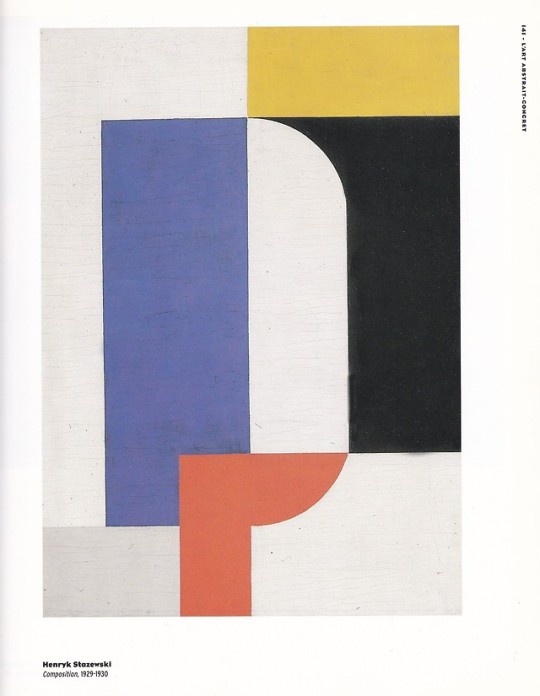

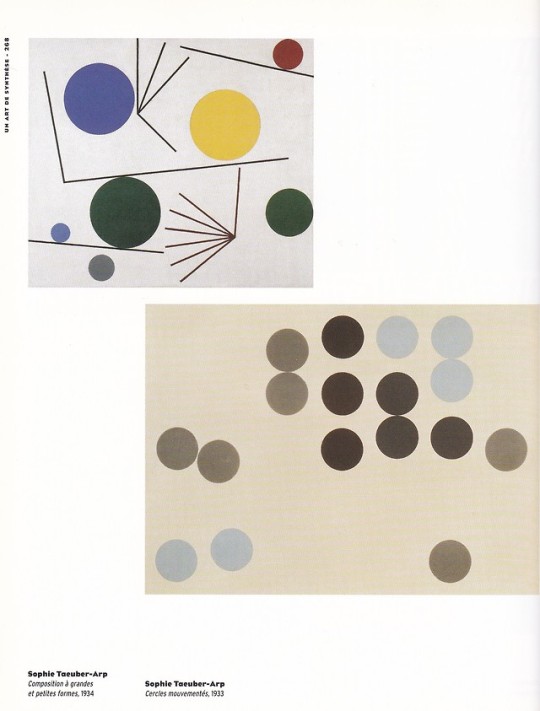

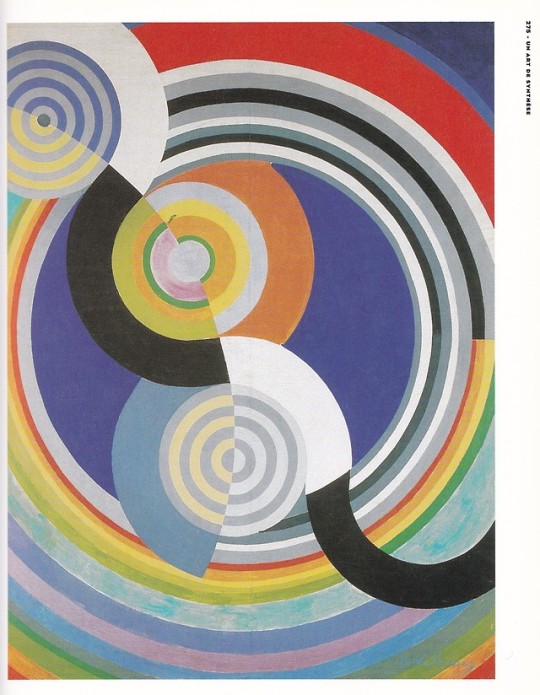

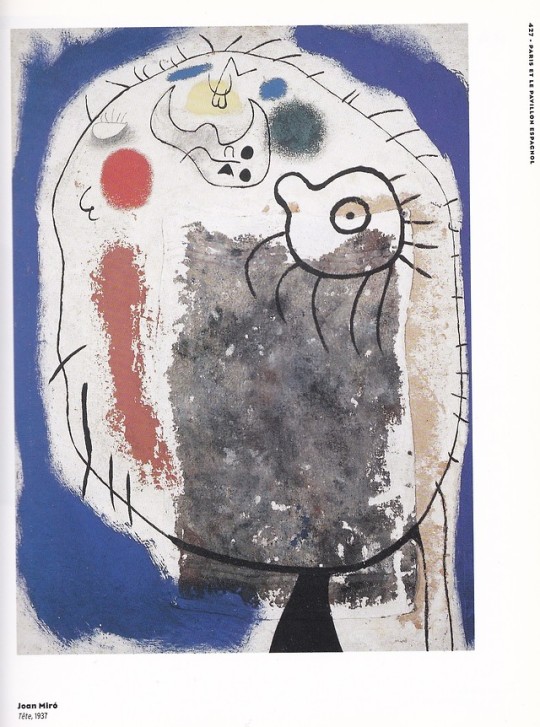

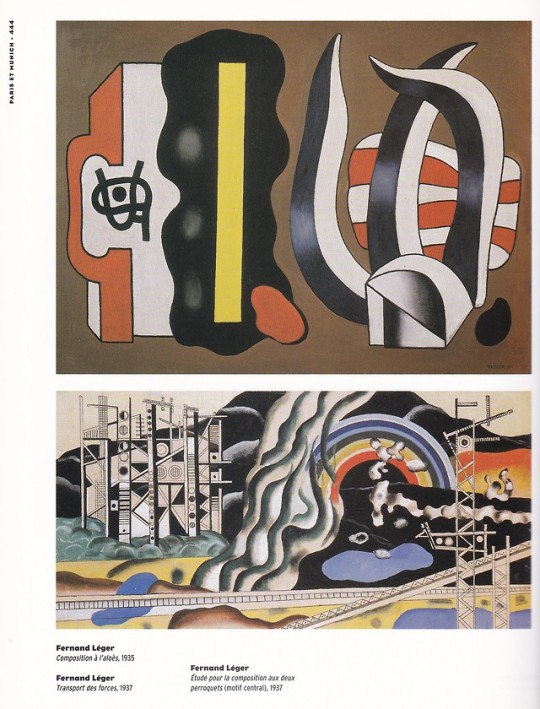

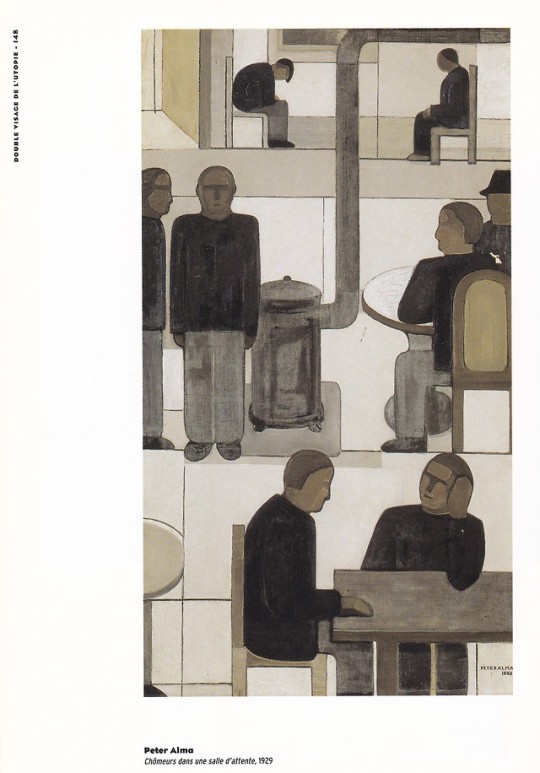

Années 30 en Europe

Le temps menaçant 1929-1939

Avant-propos par Suzanne Pagé Textes de Michel Winock, Eric Michaud, José Vovelle

Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

Paris musées Flammarion, Paris 1997, 571 p., 625 ill. en noir et 339 en coul., ISBN: 2-87900-323-7, Used Acceptable book, damaged cover

euro 50,00*

email if you want to buy :[email protected]

Exposition du 20 fevrier au 25 mai 1997

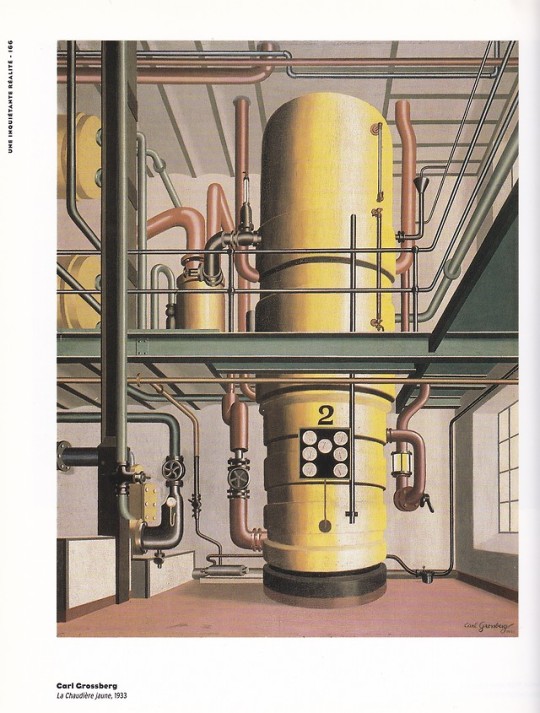

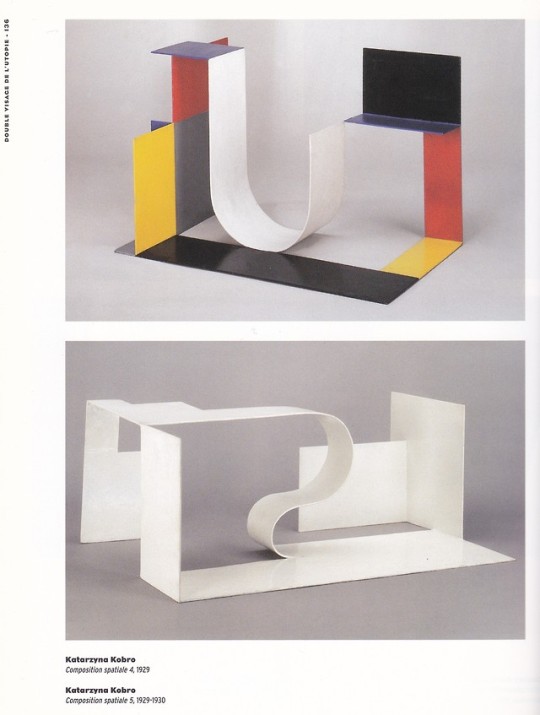

Oeuvres de Ernst, Derain, Matisse, Kobro, Hoerle, Scipione, De Chirico, Carrà, Dalì, Mirò, Tanguy, Brauner, Matta, Evans, Cahun, Wols, Mondrian, Giacometti, Hepworth, Gabo, Moholy-Nagy, Villon, Baumeister, Fontana, Schwitters, Kandinsky, Moore et al.)

Les années trente, cette décennie fatale, entre crise et guerre mondiale, a longtemps été délaissée pour diverses raisons. Trouble, elle est en effet marquée par des antagonismes puissants: modernité et tradition, nationalisme et internationalisme, art autonome, art engagé et propagande. L'objectif de l'exposition qui s'est tenue au musée d'Art moderne de la ville de Paris en 1997, et de son catalogue, est de livrer un état des lieux de la période, dans sa complexité parfois déconcertante, à travers un double parcours chronologique étroitement complémentaire qui lie les actualités aux oeuvres d'art.

orders to: [email protected]

twitter: @fashionbooksmi

flickr: fashionbooksmilano

instagram: fashionbooksmilano

tumblr: fashionbooksmilano

#Années 30#Europe#1929 1939#Musée art moderne Paris#thirties#anni trenta#arte anni trenta#art exhibition catalogue#fashionbooksmilano

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jacobins. loin des anachronismes.

Jacobins. Au-delà des raccourcis, des caricatures et des anachronismes.

Ils ont mauvaise presse mais les connaît-on vraiment au-delà des raccourcis, des caricatures et des anachronismes ? Dans son livre intitulé Les Jacobins (La découverte, 1999, 2001) Michel Vovelle tente une synthèse de l’id��ologie qui anima le mouvement jacobin durant la décennie révolutionnaire. Ni la Terreur ni le centralisme excessif ne sont au cœur de ce que l’on peut légitimement retenir de…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

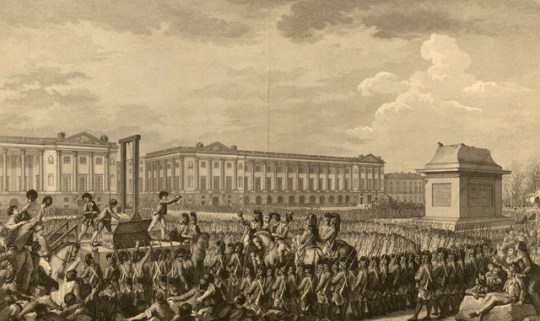

Given [Michel] Vovelle’s position as scientific coordinator of the bicentennial [i.e. the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution in 1989], he could not afford to herald any lack of resolve on the so-called objectivity question. Nor could he allow François Furet to capture the terra firma of scholarship and relegate his adversaries to the boggy ground of ideology. Yet he revealed himself to be torn about how to articulate the relationship between vie scientifique and vie militante. Both the nature of the bicentennial issues and the stakes involved made it hard to segregate the two impulses. An important part of Vovelle’s evangelism, after all, turned on the idea that reflection on the French Revolution “is not merely an academic or school exercise.” [...]

Since “the Revolution today is still an object of battle” and “of pertinence,” it was bound to elicit very strong feelings. Indeed, to make his case for exceptionalism [...] Vovelle contended that France remained deeply divided over the Revolutionary heritage / message / mission. [...]

In the same vein, Vovelle was forced to argue a position that worried most historians – that “objectivity” and “fervor” were not incompatible. [...] Indeed, as far as the history of the French Revolution was concerned, they were perforce complementary, for there was a “civic dimension in the history of the Revolution” that morally had to be put “in the service of the republic”. Thus, [...] celebration went hand in hand with commemoration, somehow without sacrificing or blemishing the critical purview without which the historian had no legitimacy. Since “the terrain of study of the Revolution carried a ‘plus’ that went beyond its properly scholarly dimension,” it apparently allowed for a certain derogation from the standard rules. Thus Vovelle situated “his action” in the “lineage” of Alphonse Aulard’s aphorism, “To understand the French Revolution, one must love it.” [...] In Vovelle’s analysis, the Revolution was alive, hot, beloved, somewhat jealous and mercilessly maligned.

Farewell, Revolution: The Historians' Feud, France, 1789/1989 (S. L. Kaplan)

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

At the Sorbonne, allegedly the stronghold of Jacobin historians, Michel Vovelle replaced Albert Soboul in 1985. The following year he offered to organize a ‘calf’s head dinner’ for postgraduates on 21 January. This is a traditional republican ritual in which the calf’s head represents the head of the king: the people, gathered at a banquet, replay the king’s death in carnival mode. Vovelle’s proposal met with an icy reception. For the majority of students, even those enrolled in the Sorbonne’s course on the history of the Revolution, it seemed indecent. The merry chuckling of Michel Vovelle was met by an embarrassed and incredulous silence. The calf’s head ritual had become non-contemporary, without time being taken to assess it properly. It was impossible now to ‘replay’ the severed head – that kind of thing was shocking, or troubling at the least. To my mind, this collective banquet belongs to the ‘obligatory expression of sentiments’, i.e. to ‘a broad category of oral expressions of sentiments and emotions with a collective character’:

This in no way damages the intensity of these sentiments, quite the contrary . . . but all these collective expressions, which have at the same time a moral value and an obligatory force for the individual and the group, are more than simple manifestations . . . If they have to be told, it is because the whole group understands them. More than simply an expression of one’s own sentiments, these are expressed to others, since they have to be expressed in this way. They are expressed to oneself by expressing them to others and for their benefit. This is essentially a matter of symbolism.

This republican symbolism, however, came undone in the 1980s and 1990s. When the bicentennial celebration came round, the question of revolutionary violence returned to disturb some of the certainties that had newly imposed themselves since the Liberation.

In Defence of the Terror (Sophie Wahnich)

#French Revolution#frev#historiography#soboul#vovelle#albert soboul#michel vovelle#tdv#sophie wahnich

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

I agree with @mali-umkin.

I have an issue with the reaction of Paul Chopelin and Jean-Clément Martin. It's good to present historical facts, but when I'm looking to the tweetstroms from Mathilde Larrere, historian specialized in revolutionary movements, their speech seem to be an answer that lacks analysis of current events.

Larrere often analyzes modern social movements, she understands that the revolution still feeds the collective imagination today. She has shown this many time in particular with the Yellow Vests movement.

By the way, this is not the first time that Chopelin criticizes the use of Robespierre by the left. He did the same thing last July 14th when Robespierre was trending on Twitter. But I think that Chopelin and Martin, in their fed up with the lack of historical rigor of politicians, have lacked this same scientific rigor. They failed or unwilling to elevate the debate. They only presents facts.

Here are some things they could have talked about :

The figure of Robespierre was already controversial when he was still alive. He was so adored and so hated that at the end of his life he was beaten by his own legend. Could suggest consulting Leuwers' work, their collegue, on the Robespierre myth.

Using figures in politics has always existed and served a political purpose, even during the revolution. Jacques Roux presented himself as 'Marat's heir', to prove his closeness with the sans-culottes, even if they didn't have the same political opinions about economy.

To the left, revolution and Robespierre are spoils of war and rightful examples. Babeuf inspired communism. Lenin was inspired by the Jacobin governance but remains very critical because it was too bourgeois. Louise Michel loves Saint-Just.

If politicians lacks of rigor, historians are NEVER neutral. The historiography of the revolution proves it. Mathiez and Aulard argued because one defended Danton while the other defended Robespierre. Does a bias prevent a rigorous work ? Mathiez' analysis of Danton's accounts to prove that he was corrupt shows it doesn't.

Highlight the problem of the follow-up of the school institutions in relation to the progress of the historical works. We got stuck in 1989, because it was the last time that there were historiographical debates on television accessible to the general public. There was a cultural battle between Michel Vovelle and François Furet during the bicentenary. Today, television is slowly starting to give more decent documentaries (I'm talking about the documentary where the revolutionaries are interviewed) but it still far behind. On the internet, we can congratulate 'Nota Bene' and 'Histony' for having done a work respecting at best the recent works.

I would end with the question that neither of them asks : why does the French left still use Robespierre today ?

=> Because the end of the Soviet bloc and socialists making liberal politics destroyed the collective imagination of the left. The USSR put an end to the possibility of an alternative society with communism. Capitalism won. And the french socialist party, allying itself with liberalism, reinforced the idea there was no alternative to capitalism. If the left wants to win, it must rebuild an imaginary that speaks to all, even to minorities.

This is what Antoine Leaument is trying to do. It's to say "we, our France, we want it to be anti-colonial, born from the constitution of 1793, this France that abolished slavery".

In her latest interview with Dany and Raz, Houria Bouteldja, spokeswoman for the Indigenous of the Republic, thinks using French revolution and Robespierre inside the collective imagination of the left is a good start (1:14:47-1:15:52).

And what better start to use the one who once said "Let's perish our colonies !" ? 😏

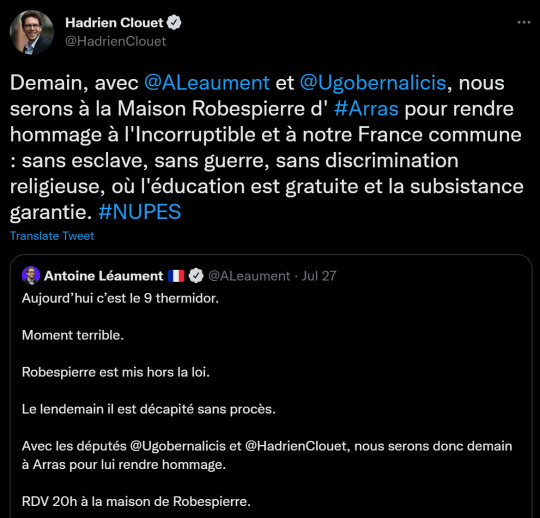

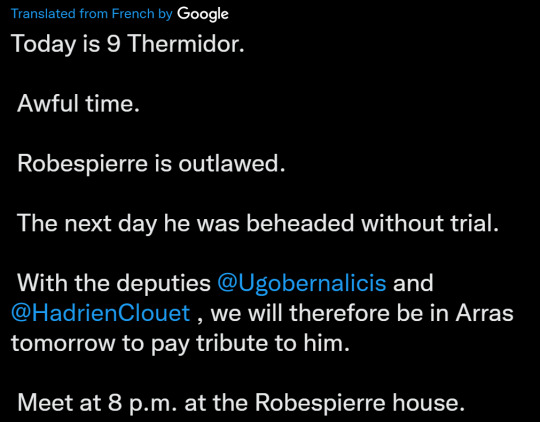

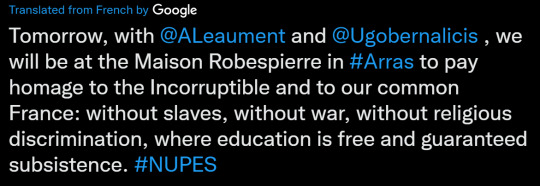

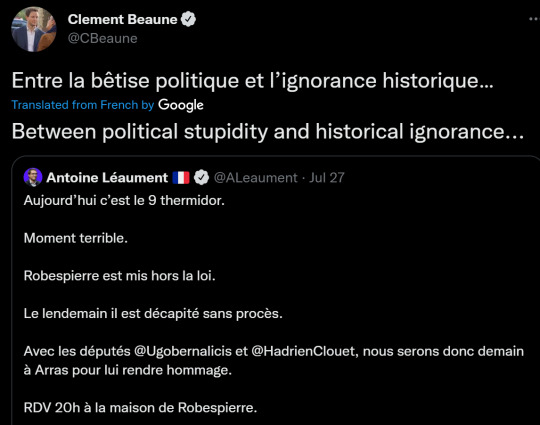

Apparently there’s controversy in France over 3 deputies from NUPES going to Arras to pay tribute to Robespierre on 9 Thermidor

Reaction from Macron’s Minister of Transport:

And this…what the hell is this

And then a Frev historian made this whole thread where he was like “yeah Robespierre has been unfairly slandered and said some good things but he was also a conspiracy theorist”:

To be very fair to him the rest of his thread is pretty firmly neutral on Robespierre but unfortunately most people who read the thread were just like YEAH YOU TELL THEM!!! ROBESPIERRE WAS TERRIBLE!!!

anyway french politics is a whole ass mess it seems

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le déchaînement médiatique autour de l’apparition de ce nouveau virus requière probablement quelques remarques. L’inquiétude grandit, y compris parmi les chrétiens. Comment intégrer cette nouvelle réalité ? Quels points de repères bibliques permettront de naviguer dans cette crise ?

Je m’apprêtais à embarquer pour un vol transatlantique. Le personnel au sol attendait l’autorisation de faire entrer les passagers et nous formions une longue file d’attente. Je me suis mis à tousser – j’ai une sorte de toux asthmatique depuis quelques mois. Les gens se sont tournés vers moi avec des regards qui évoquaient la crainte ou la colère. J’ai expliqué que c’était de l’asthme et plusieurs se sont détendus. Certains ont même risqué un sourire. Diantre, heureusement que ce n’est pas la peste qui circule !

A propos… la peste…

Justement, je suis en train de lire quelques livres et articles au sujet de ce fléau qui a parcouru l’Europe 2 à 3 fois par centenaire à partir du 14e siècle. Je cherche à comprendre les réactions des foules et à découvrir les bons réflexes des chrétiens. En fait, ce n’est pas toujours brillant. En l’absence de compréhension médicale, le fléau avait forcément une origine « spirituelle ». L’historien John Hatcher décrit les orientations du clergé d’Angleterre :

Alors que la peste se rapprochait de plus en plus de l’Angleterre durant l’été 1348, l’Église a naturellement pris l’initiative de donner des conseils sur la manière d’apaiser la colère de Dieu. De nombreux évêques écrivirent des lettres �� lire en anglais, dans des mots que tous pouvaient comprendre, dans toutes les églises paroissiales de leurs diocèses, pour demander la confession et ordonner des processions et des messes pénitentielles. Les premières de ces lettres ont été écrites par l’archevêque de York et l’évêque de Lincoln dans les derniers jours de juillet, et à la mi-août, Edward III a demandé à l’archevêque de Cantorbéry d’organiser des prières, des messes, des sermons et des processions dans toute la province de Cantorbéry « pour protéger le royaume d’Angleterre de ces fléaux et de la mortalité ». […]

Dans les discussions fréquentes concernant la signification de la peste noire et de ses manifestations ultérieures, on ne pouvait nier que Dieu infligeait la peste en réponse au péché de l’humanité, et des parallèles avec les fléaux bibliques étaient fréquemment établis. Mais les penseurs les plus perspicaces ont cherché à voir ce fléau non pas simplement comme un acte de vengeance, ou même comme un juste châtiment infligé par un Dieu en colère, mais comme un moyen miséricordieux de détourner les gens de leurs voies pécheresses afin qu’ils puissent finalement être sauvés.

John Hatcher, The Black Death: An Intimate History, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2010, Édition Kindle, l. 1506, 1520.

Malheureusement, les réactions n’étaient pas confinées à une introspection morale. Bien souvent, il fallait trouver des coupables et les Juifs étaient tout trouvés pour endosser une responsabilité fantaisiste et dramatique. Jean-Claude Guillebaud a étudié cet aspect terrible de notre histoire, et recense dans La Vie ces événements effroyables :

Jean Froissart (v. 1337 – v. 1404), le grand chroniqueur de l’époque médiévale, est l’un de ceux qui ont le mieux raconté les événements.

« En ce temps, écrit-il, furent généralement par tout le monde pris et brûlés les Juifs, leurs avoirs confisqués, excepté en Avignon, en terre d’Église. » À Strasbourg, en février 1349, ajoute-t-il, 2000 Juifs périssent sous les coups de la populace qui les accuse d’avoir empoisonné les sources et les fontaines.

L’historien Michel Vovelle, dans un texte destiné à l’Encyclopædia Universalis de 2004, donne des précisions :

En 1349, après la Peste noire, les Juifs d’Allemagne furent enfermés dans un quartier dont les portes étaient closes chaque soir. Il s’agissait bien de ghetto, même si le terme ne fut officialisé qu’en 1516, par une encyclique du pape Paul IV. Dans les faits, Jean 1er de Pologne avait institué, dès 1494, le premier ghetto de son royaume. Or les Juifs qui avaient émigré vers la Pologne et la Lituanie à partir du XIIIe siècle – bien avant la Peste noire – y avaient été invités par les souverains de ces pays qui comptaient sur eux pour relancer l’économie. L’Histoire, hélas, devint vite tragique. Mais la rumeur accusant les Juifs d’avoir empoisonné sources et fontaines fut relayée par une autre accusation : celle d’avoir plus facilement échappé à la peste que les chrétiens. Elle s’exprima notamment dans plusieurs villes italiennes, dont Ferrare, en Émilie-Romagne, en 1386. On chercha à établir que pareil « privilège » était forcément le résultat d’une dissimulation.

Jean-Claude Guillebaud, « La Peste noire et les Juifs », La vie, 5/3/2020.

Les foules, volatiles, sont sensibles aux drames de l’Histoire. La peur est parfois la conseillère la plus grave, la plus stupide, et la plus aveugle. Je suppose que la nouveauté du virus a suscité un intérêt qu’il ne mérite peut-être pas tant que ça[1]. Mais en tout état de cause, la consolation et la sagesse de l’Écriture doivent nous aider à garder la tête sur l’épaule.

L’Église doit avoir une perspective claire de la manière dont la Bible aborde ces situations. Je vous suggère qu’il y a (1) des erreurs à éviter dans nos relations, (2) des attitudes à encourager dans l’Église, (3) des comportements à favoriser.

Quelques erreurs à éviter dans nos relations

Expliquer Dieu

« Pourquoi Dieu permet-il ceci ? » est la première question que nous entendons lorsque nous abordons la foi devant la souffrance. Il est tentant de vouloir défendre Dieu, comme si nous connaissions les rouages de son raisonnement. Les réponses faciles ou rapides ne seront guères convaincantes. Jésus évoque ce problème en Luc 13 :

1En ce temps-là, quelques personnes vinrent lui raconter ce qui était arrivé à des Galiléens dont Pilate avait mêlé le sang avec celui de leurs sacrifices. 2Il leur répondit : Pensez-vous que ces Galiléens aient été de plus grands pécheurs que tous les autres Galiléens, parce qu’ils ont souffert de la sorte ? 3Non, vous dis-je. Mais si vous ne vous repentez pas, vous périrez tous de même. 4Ou bien, ces dix-huit sur qui est tombée la tour de Siloé et qu’elle a tués, pensez-vous qu’ils aient été plus coupables que tous les autres habitants de Jérusalem ? 5Non, vous dis-je. Mais si vous ne vous repentez pas, vous périrez tous pareillement.

Les gens qui souffrent (catastrophe naturelle ou violence humaine) ne sont pas responsables. Pas de karma ni de culpabilité personnelle. Au mieux, ces catastrophes nous renvoient à notre mortalité, à notre fragilité, et pousseront certains à cheminer et à rechercher une réconciliation avec Dieu. La mort est une réalité ! Notre monde est brisé depuis Genèse 3 et attend avec impatience le nouvel univers (Romains 8.19).

Expliquer la souffrance

« Pourquoi la souffrance » est une variante de la question précédente. C’est tentant, là encore, de dire : « C’est le diable », ou bien : « C’est que tu as un problème avec Dieu ». Ou encore de pointer du doigt la pseudo défaillance dans la marche d’une personne. Lorsque Dieu se présente à Job, après les terribles souffrances qu’on lui connaît, le Seigneur ne lui explique rien de ce qui précède – le « deal » avec le diable, l’autorisation terrible des souffrances qui l’étreignent. Dans Le manuel du prédicateur, Philippe Viguier et moi soulignons :

Pendant deux chapitres, Dieu assène Job de questions auxquelles il est impossible de répondre (chapitres 38 et 39). « Je ne sais pas » est la seule réponse possible… Job commence à comprendre que ‘Dieu est incompréhensible…’ […] L’incompréhensibilité de Dieu (un thème théologique majeur : la nature et les décrets de Dieu échappent à toute compréhension exhaustive) est au centre de ces deux chapitres. Mais ce n’est pas tout. Quand Job commence à comprendre – « Je mets ma main sur ma bouche » 40.4 – Dieu enchaîne avec une autre série de questions qui révèlent que Dieu gère le mal, dont les animaux violents de l’époque sont l’emblème, à sa manière. Job entend le message et sa réplique est célèbre : « Mon oreille avait entendu parler de toi, mais maintenant, mon œil t’a vu » (42.5). […] ‘Dieu est incompréhensible, mais connaissable’ […] ‘on ne peut comprendre Dieu, mais on peut le connaître’.

Florent Varak, Philippe Viguier, Le manuel du prédicateur, Editions CLE, 2017, p. 180-181.

Devenir ‘prophète’

J’ai lu quelques posts sur les réseaux sociaux de « prophètes auto-proclamés ». Ils « savent » ce que Dieu fait et fera. Ils invitent à faire des courses supplémentaires (ce qui entretient la panique). Ils annoncent d’autres cataclysmes, dont l’évolution du virus. Certains ont « vu » que c’était un acte militaire… chinois… américains – ou israélien, bien sûr ! Les théories du complot se multiplient, des entreprises pharmaceutiques aux laboratoires militaires…

Je relisais ces dernières semaines les souffrances de Jérémie. Il était le seul prophète de Dieu, entouré par des centaines de faux prophètes. Dieu parle par l’Écriture, qui qualifie à toute œuvre bonne (2 Timothée 3.16-17 ; 2 Pierre 1.20-21). La foi a été transmise aux saints « une fois pour toutes » (Jude 1.3). Méfiez-vous des profiteurs de malheurs qui mettent en avant une illumination personnelle.

Profiter de la souffrance

Les prêtres du temps de la peste utilisaient la souffrance et la peur pour insuffler un élan de repentance. Certes, les plaies de l’Apocalypse nous montrent combien cela peut être une motivation puissante pour réfléchir à sa manière de vivre. Néanmoins, n’étant pas encore dans les affres de la tribulation, il me semble qu’une récupération du Coronavirus à cette fin est au mieux maladroite, et au pire totalement contreproductive.

La souffrance du monde a conduit à l’incarnation du Christ, qui prend notre souffrance avec lui à la croix (Esaïe 53.3-6). Dieu a rejoint notre souffrance, proposant une rédemption pleine de bienveillance. Mieux vaut aimer le malade et se rapprocher de lui pour aborder l’Évangile avec sensibilité et respect.

Donner des remèdes

Les médecins… ne sont pas médecins pour rien ! Je suis frappé des conseils nombreux que l’on reçoit quand on attrape quelque chose. Chacun y va de son histoire personnelle, ou de celle de son voisin, pour annoncer péremptoirement la solution au problème ! Certes, les « bons » conseils sont à prendre, lorsqu’ils sont bons. En l’absence, mieux vaut s’en référer à des personnes dont c’est le métier et l’expérience.

Une variante « spiritualisante » de ce conseil consiste à tenir des promesses totalement infondées : « Dieu protège les siens » ou pire, « Dieu guérit ceux qui croient ». Ce n’était pas le cas d’Étienne, ni de Jacques, ni de Timothée, ni de Paul dans la Bible. On est au bord d’une superstition, qui ignore ce que rappelle le Seigneur, à savoir, que Dieu « fait lever son soleil sur les méchants et sur les bons, et il fait pleuvoir sur les justes et sur les injustes » (Matthieu 5.45)

Quelques attitudes à encourager dans l’Église

La confiance absolue

La peur du Coronavirus n’engendrera rien de plus que la paralysie ou de mauvais réflexes. Jésus nous le rappelle : « Qui de vous, par ses inquiétudes, peut ajouter un instant à la durée de sa vie ? » (Matthieu 6.27). Et il ajoute : « Même vos cheveux sont tous comptés. N’ayez donc pas peur : vous valez plus que beaucoup de moineaux » (Luc 12.7).

Dieu règne à la perfection sur nos vies. Pas toujours comme nous le voudrions. Mais il règne. L’apôtre Paul nous encourage à remplacer l’anxiété (stérile) par la prière (utile sur soi et sur les événements) :

6 Ne vous inquiétez de rien, mais en toute chose faites connaître vos besoins à Dieu par des prières et des supplications, dans une attitude de reconnaissance. 7 Et la paix de Dieu, qui dépasse tout ce que l’on peut comprendre, gardera votre cœur et vos pensées en Jésus-Christ. 8 Enfin, frères et sœurs, portez vos pensées sur tout ce qui est vrai, tout ce qui est honorable, tout ce qui est juste, tout ce qui est pur, tout ce qui est digne d’être aimé, tout ce qui mérite l’approbation, ce qui est synonyme de qualité morale et ce qui est digne de louange. 9 Ce que vous avez appris, reçu et entendu de moi et ce que vous avez vu en moi, mettez-le en pratique. Et le Dieu de la paix sera avec vous (Philippiens 4.6–9)

L’amour de l’étranger – ou de la personne différente

L’histoire nous rappelle que les hommes cherchent souvent des boucs émissaires. Hier, c’était les Juifs. Aujourd’hui, j’apprends que des personnes d’apparence asiatique sont stigmatisées à cause de l’origine géographique du virus. Ils entendent des gens leur hurler : « Rentrez chez vous ». Les restaurants chinois subissent les lourdes pertes d’une fréquentation en berne. C’est tellement triste. Beaucoup d’entre eux n’ont rien de touristes. Ce sont des compatriotes, et en tant que fils d’Adam, ce sont nos frères d’humanité. Quelle belle occasion, pour les chrétiens, de se mobiliser pour continuer de manifester l’amour de tous. Ça vous dit un restau chinois ?! – uniquement si les rassemblements sont encore autorisés !

L’amour du malade

L’amour désintéressé a été la plus belle signature des chrétiens confrontés aux dangers des épidémies des temps passés. Après tout, nous savons où nous allons, nous. Pour un disciple de Christ, le pire ne sera jamais le pire. L’apôtre Jean nous rappelle : « Il n’y a pas de peur dans l’amour; au contraire, l’amour parfait chasse la peur, car la peur implique une punition. Celui qui éprouve de la peur n’est pas parfait dans l’amour » (1 Jean 4.18). Aimer un malade, notamment si c’est là notre mission de soignant, est un immense privilège, une magnifique forme d’amour du prochain. Et le plus parfait témoignage de l’Évangile.

La prière pour les personnels de santé

Le personnel de santé va être durement sollicité. Ce serait formidable qu’il y ait un élan de prière et d’affection à l’égard de ces gens, de nos Églises ou de notre entourage, qui portent cette charge. Un médecin de notre Église m’a dit que des hôpitaux avaient été volés de leurs masques – si c’est à ce point, qu’en sera-t-il d’une épidémie plus meurtrière ?! C’est l’occasion de soutenir ceux qui auront à rassurer constamment, et qui devront accroître leur charge de travail ces prochains mois.

La prière pour la sagesse des responsables

Le choix de la réponse à donner face à de telles situations n’est pas évident. Un homme ou une femme politique peut être tiraillé entre une réponse émotionnellement alignée avec les attentes d’une population inquiète, et une réponse rationnelle, proportionnelle à la dangerosité réelle de la situation. La prière pour les responsables politiques[2], fait partie de la responsabilité de l’Église.

Les anciens des Églises devront également aménager quelques modes de fonctionnement. Faire face à la peur, parfois à la détresse de la maladie. Priez pour que leur joie demeure, et qu’ils aient la sagesse de prendre les décisions qui s’imposeront.

Quelques comportements à favoriser

La prière pour les malades

Jacques nous instruit que les chrétiens peuvent faire appel aux anciens pour qu’ils prient pour eux :

13Quelqu’un parmi vous est-il dans la souffrance ? Qu’il prie. Quelqu’un est-il dans la joie ? Qu’il chante des cantiques. 14Quelqu’un parmi vous est-il malade ? Qu’il appelle les anciens de l’Église, et que ceux-ci prient pour lui, en l’oignant d’huile au nom du Seigneur ; 15la prière de la foi sauvera le malade, et le Seigneur le relèvera ; et s’il a commis des péchés, il lui sera pardonné.

16Confessez donc vos péchés les uns aux autres, et priez les uns pour les autres, afin que vous soyez guéris. La prière agissante du juste a une grande efficacité.

Il faut noter

L’importance de la prière : c’est le verbe principal de cette exhortation. L’onction d’huile est symbolique[3].

L’importance de la patience (l’exemple de Job est donné au verset 11)

L’importance de l’intégrité des participants : les malades comme les anciens peuvent être appelés à confesser leurs péchés.

L’importance de l’obéissance : les anciens n’ont pas le choix que de répondre à l’invitation.

Lorsque nous sommes malades, Dieu peut nous aider! Il n’a pas promis de nous guérir, mais il a promis d’être attentif et de nous répondre soit en nous donnant, soit la grâce de la patience, soit la grâce de la guérison.

Ceci dit, les anciens en situation de fragilité (par leur âge ou leur responsabilité familiale) doivent aussi considérer si leur présence est nécessaire. Il ne me semble pas impératif que tous les anciens soient tous présents.

Le report du saint baiser 🙂

La fraternité affective du « saint baiser » (Rm 16.16, 1 Co 16.20, 2 Co 13.12, 1 Th 5.26) est une marque heureuse des assemblées chrétiennes[4] ! En même temps, surseoir à cette pratique pour quelques semaines ou quelques mois, est une réaction de bon sens. Dans la hiérarchie de l’éthique des commandements[5], l’amour du prochain est tout du même en haut de la pyramide. Prendre soin de son frère en le protégeant d’une contamination éventuelle, est éminemment charitable. Cela ne me semble pas correspondre au rejet de l’Écriture, tant que c’est temporaire.

La préparation de la cène

J’ai abordé dans un podcast la question de la coupe communautaire ou du gobelet individuel. Un aspect corolaire à cette discussion est lié à l’hygiène des deux options. Beaucoup d’églises ont décidé d’utiliser des coupes individuelles. Encore faut-il que les préparateurs emploient des gants ou comprennent l’importance de mains… propres… avant de séparer les coupes[6] ou rompre le pain.

Excès de zèle ? Peut-être. Choisir d’être prudent quelques temps n’est pas un manque de confiance. Après tout, si même MacDonald se sert de gants pour préparer des hamburgers, on peut faire aussi bien pour le pain et le vin !

L’anticipation technique

Je crains que les rassemblements soient interdits dans de nombreux départements. Il est sage d’anticiper et de préparer l’Église à une période où l’on devra vivre des cultes ensemble différemment : rassemblement de 2 ou 3 familles ? Diffusion d’un temps de louange et d’enseignement via le net[7] ? Certes, ces alternatives ne sauraient s’inscrire dans la durée. Mais s’il est nécessaire de rompre les rassemblements quelques semaines, cela permettra au moins de maintenir une connexion, même virtuelle, quelques temps.

Conclusion

Bon, ce tour d’horizon est probablement bien trop court. J’espère qu’il donne néanmoins quelques repères pour se situer en prenant en compte l’Écriture dans le flot d’informations lié à cette crise du Coronavirus. La confession de foi dite de La Rochelle (1559) dit à juste titre :

Ainsi, en confessant que rien ne se fait sans la providence de Dieu, nous adorons avec humilité les secrets qui nous sont cachés, sans nous poser de questions qui nous dépassent. Au contraire, nous appliquons à notre usage personnel ce que l’Écriture sainte nous enseigne pour être en repos et en sécurité; car Dieu, à qui toutes choses sont soumises, veille sur nous d’un soin si paternel qu’il ne tombera pas un cheveu de notre tête sans sa volonté. Ce faisant, il tient en bride les démons et tous nos ennemis, de sorte qu’ils ne peuvent nous faire le moindre mal sans sa permission.

Terminons avec Philippiens 4.7 : « [Que]la paix de Dieu, qui dépasse tout ce que l’on peut comprendre, garde[ra] votre cœur et vos pensées en Jésus-Christ. »

Annexes: quelques livres

Parmi les livres que je recommande sur les questions de Dieu et la souffrance:

Bryant, Henry, Si Dieu est bon pourquoi la souffrance, Editions CLE, 2011.

Carson, Donald A., Jusqu’à quand? Réflexions sur le mal et la souffrance, Excelsis, 2012.

Keller, Timothy, La souffrance, Editions CLE, 2015.

Piper, John, Prendre plaisir en Dieu malgré tout, Sembeq, 2006.

[1] Je me risque à observer que sa létalité, toujours trop élevée évidemment, n’a rien à voir avec la mortalité du paludisme, ou du fumeur. Bien entendu, son impact à long terme reste inconnu, et une mutation pourrait changer la donne. Notons au moins que nous ne sommes pas encore confrontés à une plaie de proportion biblique.

[2] Voir Varak et Viguier, L’Évangile et le citoyen, Editions CLE, 2015, pour l’orientation de nos prières vis-à-vis de l’État.

[3] Deux mots évoquent l’onction d’huile : L’un décrit l’acte de se parfumer, d’embaumer, de verser du parfum, comme cette dame qui a versé sur les pieds du Christ un parfum de grand prix (Jean 12.3, voir aussi Matt 6.17, Marc 6.13, 16.1, Luc 7.38ss.). L’autre décrit le geste cérémoniel de consécration, d’envoi, ou de dédicace (Luc 4.18, Actes 4.27, 10.38, 2 Cor. 1.21, Héb. 1.9). C’est le premier que Jacques emploie. Il s’agit d’un geste symbolique de guérison.

[4] Même si j’avoue que mes premières réactions, à mon arrivée dans le monde évangélique, étaient plutôt réticentes à cette affection générale que je trouvais parfois déplacée !

[5] Je sais que c’est une simplification extrême. Pour une présentation plus charnue, lire Vincent Rébeillé-Borgella, Petit manuel d’éthique pratique, Editions CLE, 2017.

[6] Quand une personne sépare les gobelets empilés, il laisse ses germes !

[7] Crowdcast, Zoom, Livestorm, Clickmeeting, GoToWebinar, etc. Nous avons créé un guide illustré pour mettre en place facilement un culte en direct dans votre Église.

0 notes

Note

are you reading any good books right now?

these are the books i am currently reading:

robespierre and the festival of the supreme being by johnathan smyth

one god: pagan monotheism in the roman empire by stephen mitchell & peter van nuffelen

the theory of mind as pure act by giovanni gentile

the coming of american fascism by lawrence dennis

the revolution against the church by michel vovelle

law, labor, and ideology in the early american republic by christopher l. tomlins

the nomos of the earth by carl schmitt

political theology by carl scmitt

rome reborn on western shores by eran shalev

freedom and the rule of law by anthony a. peacock

the enigmatic reality of time by michael f. wagner

philosophy in the bedroom by marquis de sade

selected letters by cicero

corporatism and consensus in florentine electoral politics by john m. najemy

dune by frank herbert

quicksilver by neal stephenson

nature’s god: the heretical origins of the american republic by matthew stewart

5 notes

·

View notes